Chapter Six

Nothing but Disaster

“This whole blockade is and has been unsatisfactory from the beginning,” wrote Gideon Welles in July 1862.1 He was referring specifically to leaks in the blockade of Wilmington, North Carolina. But the same expression of dissatisfaction could have applied to Charleston, Mobile, and other ports. The navy’s capture of Hatteras Inlet, Port Royal, Fernandina, New Orleans, and other smaller ports had shut them down. And the occupation of many estuaries and bays along the south Atlantic and Gulf coasts had denied easy access to the shallow-draft schooners and other craft that had run in and out during the war’s early months. But some still tried it in 1862, and they constituted the majority of the 390 blockade-runners captured or destroyed in 1862—including four schooners caught along the Gulf coast by the ninety-day gunboat USS Kanawha on the single day of April 10, 1862, earning a nice sum of prize money for the crew and their commander, Lieutenant John C. Febiger.2

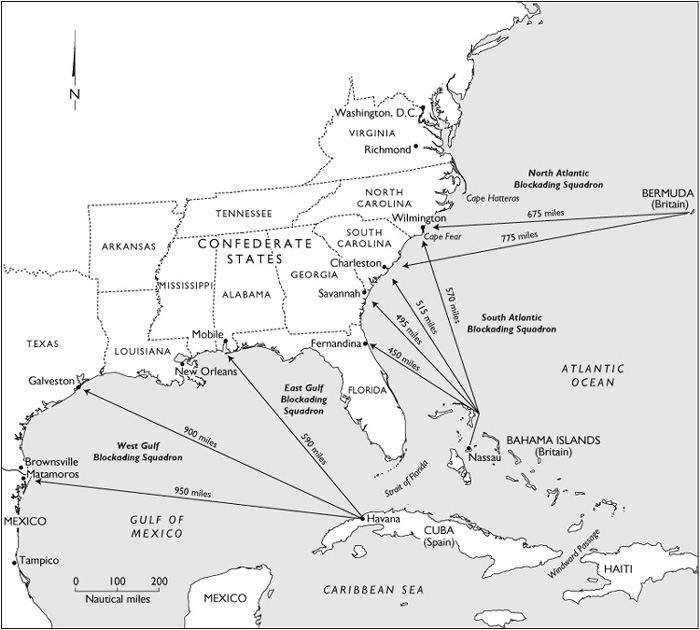

By then, however, the nature of blockade-running had begun to change. Shortages of every sort of war matériel and consumer goods in the Confederacy caused prices to commence their dizzying inflationary rise. Blockade-running became an extremely lucrative enterprise. It attracted investors from the Confederacy and abroad, mainly Britain. Even a few Northern merchants whose eye for the dollar eclipsed their patriotism got into the game. Investors or Confederate agents would buy arms, ammunition, gunpowder, shoes, coffee, salt, wine, silk, hoop skirts, and other goods in Europe and ship them in ordinary merchant vessels to Nassau, Havana, Bermuda, or Halifax, where the cargoes would be transferred to fast steamers to make a run for Charleston, Mobile, Wilmington, or perhaps another port like Galveston, where they would try to slip past the blockaders on a dark, foggy, or stormy night guided by coded signals from shore. There they would load up with cotton or perhaps another Southern product like resin or turpentine and watch for their chance to dash out on the return run.

Merchant ship captains—mostly British—and retired Royal Navy officers were often the commanders and sometimes part owners of these runners. Southern pilots who knew the coast and channels of their home region were paid handsomely for their services. The profit motive was the main attraction for officers and crews of the runners, but the excitement of adventure also played a part. “Nothing I have ever experienced can compare with it,” wrote a British officer on a runner. “Hunting, pig-sticking, steeplechasing, big-game hunting, polo—I have done a little of each—all have their thrilling moments, but none can approach running a blockade.”3

The risk of being shot at, driven ashore, or captured was real, but if they were foreigners (as most were), they would eventually be released—many to return to blockade-running—despite Welles’s wish to see them incarcerated. If caught, the ship and its cargo would be seized and evidence of its attempt to violate the blockade taken before a prize court. These courts normally ruled in favor of the U.S. government unless they found that the ship’s papers (usually falsified) showing that its cargo was consigned to a neutral port were genuine. If condemned, the ship and its cargo would be sold and the proceeds divided between the navy’s pension fund and the crew or crews of the blockade ships that had captured her. The amount of prize money to each member of the crew was prorated by rank, with the squadron commander also getting a cut for each capture. The navy bought many of the captured runners and converted them to blockade ships because they had greater speed than most naval vessels. Despite the risk of capture, there was no shortage of investors because owners could make back their investment in one or two round trips and clear pure profit with every subsequent successful voyage—and in 1862 at least three-quarters of them were successful.

Investors in blockade-running began buying the newest and fastest steamers they could find, paying premium prices. A Scottish newspaper complained in November 1862 that “there will soon be scarcely a swift steamer left on the Clyde.”4 British shipyards began building or converting vessels intended especially for the purpose: sleek in design, fast and shallow drafted, painted lead gray for low visibility, burning smokeless anthracite, and featuring a low freeboard, telescoping smokestacks, and underwater steam-escape valves so that the boat moved almost silently through the water. “The class of vessels now violating the blockade is far different from those attempting it a year ago,” wrote a Union ship captain in March 1863. “They are very low, entirely free from top hamper, and almost invisible from the color of their paint.” Although his officers and crew “all keep a sharp lookout,” it was impossible on dark nights to see a runner until it was almost on top of the blockading ship and going so fast that “vigilance alone without speed is insufficient” to catch it.5

An officer on a blockade ship off Cape Fear, North Carolina, unburdened his frustrations in a letter to his wife. “Let no one condemn the occasional running in or out of a vessel till they have experienced some of the difficulties of preventing it,” he wrote in April 1863. Because of the length of coast to be guarded, blockade ships sometimes were a mile or more apart from each other. “What is there to prevent a vessel from running between them in the darkness when it is impossible to see more than three or four hundred feet from the ship. They make but little noise as they approach, & that little is difficult to distinguish from the beating of surf on the beach—they come upon us and flit by like a phantom.”6

The wife of the Confederate agent in Bermuda who organized the cargoes for blockade-runners sailed on one of them from Wilmington with their three children to join him in Bermuda. “I did not altogether relish these ‘deeds of darkness,’” she wrote in a journal entry describing the trip. “There is a little feeling of wounded pride, that we must seek the protection of the night, & slip by our foes as noiselessly as we can. . . . The port holes were all closed, & blankets hung over them, the sky light covered, the lights all extinguished.” Thus darkened, they passed through the blockade fleet ship by ship over a period of two hours and escaped undetected.7

In 1862 most of the criticism of the navy in Northern newspapers and gloating by the Southern press over the porousness of the blockade focused on the South Atlantic coast, especially Charleston. Rumors, exaggeration, and outright fabrication magnified the numbers of ships that were reported to have evaded the blockade. A letter from Nassau published in the New York Times of May 3, 1862, listed several vessels running the blockade into or out of Fernandina and Jacksonville, Florida, during the time that Union forces actually occupied those ports. American consuls in European and Caribbean ports sent lists and descriptions of ships reported to be departing for Southern ports, and the State Department passed these on to the navy. At one time in the spring of 1862, Flag Officer Du Pont of the South Atlantic Squadron had a list of 160 such vessels, of which only a few “have ever run the blockade, or even ventured to approach the coast.”8

The captain’s clerk on the USS Flag (which was credited with nine prizes during the war) compiled a list of sixty-five vessels reported or rumored to be approaching the South Atlantic coast. Somehow the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin managed to publish this list under the headline “Vessels That Have Run the Blockade.” In fact, only two of them had done so.9 The senior officer on the Charleston blockade noted in his journal that “some ten days ago when it was said that 22 schooners had run out, only three started, and two of them grounded in the harbor and put back, and the third was captured by the Huron. The greatest number known to go out at one time was six schooners and that [was] about a month ago of which we captured two.”10 A month later, the New York Times published a story from a Nassau correspondent that thirteen blockade-runners had

U.S. Navy Blockading Squadrons Showing Distances to the Ports Favored by Blockade-Runners

recently arrived from Charleston; Du Pont noted that eight of these had actually been captured by Union warships.11

Neither Du Pont nor Welles nor any other Union officer, however, denied that a good many runners got through, especially at Charleston, Wilmington, and Mobile. All three of these port cities were difficult to blockade because of multiple navigation channels needing to be blocked. In the case of Charleston, shallow water extended far from the coastline, forcing blockade ships to stand out a substantial distance from the harbor entrance. In 1862 Du Pont could not keep more than a dozen ships guarding a parabolic line about thirteen miles long. At the entrance to Mobile Bay, three Confederate forts kept Union ships at a distance from the navigation channels. Large forts also guarded the two inlets to the Cape Fear River below Wilmington. These two inlets were only a few miles apart as the crow flies but were separated by Smith Island and Frying Pan Shoals extending far into the ocean so that blockade ships guarding each inlet were separated by fifty miles of navigable water. The Confederate commander at Fort Fisher defending New Inlet explained why blockading the Cape Fear River was so difficult, especially in the fall and winter when storms frequently drove ships to shelter: “The prevalence of southeast weather at the main entrance, while it is very dangerous for vessels outside, forces them to the northward of the cape and gives easy access to vessels running the blockade,” while “in like manner the northeast gales drive the enemy to shelter to the southward of the cape and clears the New Inlet.”12

All of the squadron commanders complained constantly to Welles that they did not have enough ships to maintain a tight blockade, that those they did have were too slow, and that their vessels were repeatedly breaking down from the wear and tear of the service. In August 1862 Du Pont acknowledged that at Charleston “the blockade has never been more violated.” The main problem, as one of his ship captains put it, was that “with the few vessels we have here I think it almost impossible to keep steamers from running in or out.”13 At the two inlets off the Cape Fear River, wrote officers on those stations, “the force now on either side of the shoal is far too small to make an effective blockade.” It was “greatly to our mortification, after all our watchfulness to prevent it, that the enemy succeeded in eluding us. None can be more vigilant than we are—the officer of the watch, with the quartermaster, always on the bridge, lookouts on each bow, gangway, and quarter. . . . I do not see how this can be prevented unless we can string the whole coast with steamers.”14

The number of ships in each blockade squadron listed on paper bore little relationship to the actual number available on station at any given time. Although by mid-1862 the North Atlantic and West Gulf squadrons had shortened the down time for resupply by establishing additional bases at Beaufort, North Carolina, and Pensacola, Florida (which the Confederates had abandoned), ships were still off their stations periodically to refill their coal bunkers. Du Pont had installed a large repair facility at Port Royal, and minor repairs could be made at Pensacola and Beaufort. But major repairs required ships to make the long trip to one of the Northern navy yards. And such repairs were needed more and more often as hard service took an increasing toll on boilers and machinery—especially of the purchased and converted merchant ships, which had not been built for such service.

No theme comes up more often in the naval records than what Du Pont described succinctly as “lame ducks.” “My vessels are coming in all the time broken down, the truth is they have been tried to the utmost,” he wrote in July 1862. A month later, one of his ships returned to Port Royal with both machinery and crew worn out. “I think his fires have been out about eleven days in eleven months. You may imagine what [effect] this is on the engineers and firemen.” Du Pont’s captains lamented that “how we are to keep up the blockade with so many vessels broken down is a problem which my arithmetic cannot solve.”15 From the Gulf, Farragut also reported so many ships “disabled, and requiring so much repairs that I almost despair of getting vessels enough to do efficient service.” Assistant Secretary Gustavus Fox told Farragut in September 1862 that “we have our navy yards filled with broken-down vessels, and we know your wants and will exert ourselves to help you, but the more we send the more they seem to come back.”16

Sailing ships did not have this problem, of course, nor did they need to leave their stations to coal. But by 1862 they were almost useless for blockading large ports like Charleston, because the fast steamers and even schooners that chose their time could nearly always outrun them. Du Pont therefore stationed most of his sailing vessels at what he called his “inside blockade” in the numerous small bays and inlets that pierced the coast from South Carolina to Florida. Flag Officer James L. Lardner of the East Gulf Squadron did the same on Florida’s Gulf coast. Because blockade-runners rarely tried to get in or out of these small inlets after 1861, blockade duty there was quite easy but also tedious, as the weeks went by and nothing happened.

The surgeon on the USS Fernandina, a bark-rigged vessel converted to a six-gun warship, kept a diary in which he chronicled this kind of duty. The Fernandina was shifted from one inlet or bay to another in South Carolina or Georgia every three months or so for a change of scene. Only once in two years did she take a prize—a schooner trying to go out through St. Catherine’s Sound with 300 bales of cotton and some turpentine. The rest of the time, the crew had little to do, which gave them leisure for walking on shore, hunting game, buying provisions from contrabands on plantations whose owners had fled to the mainland, catching fish and gathering oysters. Diary entries described the mixed pleasures and tedium of such activities.

December 16, 1862, St. Helena Sound: “The reading of light literature is carried on to a great extent in the service on account of the monotony pervading. No prizes to be seen or captured makes it rather dull work and poor pay. Oh, for a cruise on the briny deep!”

January 23, 1863, St. Simon’s Sound: “Taking exercise on shore is a great blessing to us naval officers and a luxury that few on blockade duty enjoy.”

April 30, 1863, Doboy Sound, saluting hunters from the ship who killed a young bullock: “We’ll eat your healths in some of the juicy beef whenever it is served up. . . . In a month or six weeks we will have watermelons, peaches, oranges, potatoes, etc.”

May 6, 1863, still at Doboy Sound: “Between smoking, eating and drinking I managed to kill time and drive dull care away. This blockading is rather a dull affair. We are all anxious to make a journey up North.”

May 9, 1863: “We are spoiling for a fight! Our only enemies to contend with at present are mosquitoes, sand flies, and snakes.”17

Sailors on blockade duty on the “briny deep” also experienced long periods of boredom, especially during daylight hours and moonlit nights when no runners could be expected. These times alternated with the tension and fatigue of dark or stormy nights when every sense had to remain alert. The blockaders at Charleston needed that alertness in the last days of January 1863, when it paid off in one case and the lack of it led to near disaster in another. At 3:15 A.M. on January 29, the large British merchant steamer Princess Royal neared the harbor carrying two English-built marine engines for Confederate ironclads, six 70-pound Whitworth rifled cannons and 930 steel-headed shells for penetrating iron armor, 600 barrels of gunpowder, and other military cargo worth altogether nearly half a million American dollars. The shallow-draft spotter ship USS G. W. Blunt (a schooner) saw her approaching Rattlesnake Channel and fired a shot, signaling the rest of the squadron. The gunboat USS Unadilla drove the Princess Royal aground, and the navy was able to secure the prize before the Confederates could salvage or destroy the cargo or ship. It was one of the most valuable prizes captured during the war and did a great deal for the morale of the blockade squadron.18

Two nights later, however, the Confederates struck back. Through a thick fog, the two recently completed ironclad rams CSS Chicora and CSS Palmetto State sortied from Charleston to attack the blockade fleet. The Palmetto State rammed the USS Mercedita and left her in what appeared to be sinking condition to seek other targets, while the Chicora sent several shots through the USS Keystone State, killing twenty-five men. This action stirred up a beehive of activity among the Union fleet, as some ships fled to safety and others converged on the Confederate ironclads. They returned to Charleston claiming they had sunk two blockaders and set four others on fire. None of that was true; the two badly damaged ships were towed to Port Royal for repairs, while the rest of the fleet remained at sea and soon resumed their stations. General Pierre G. T. Beauregard asserted that by scattering the fleet, the Confederates had broken the blockade, which under international law could not be reestablished without sixty days’ notice. Du Pont rejected Beauregard’s claim and continued the blockade as before.19

A good many blockade-runners that were headed to or from South Atlantic ports were captured not by the squadrons blockading those ports but by ships 400 miles or more distant in one of the channels through the Bahamian Islands. In the war’s first year, Nassau was the principal transshipment port for blockade-runners. It was closer to Confederate ports on the Atlantic than any other neutral port. But all traffic had to funnel through narrow channels in the shallow waters of the Bahamas, where Union blockade ships of the East Gulf Squadron learned to lie in wait. Making their passages in or out of Confederate ports at night, runners often found themselves in the Bahama channels in daylight, where they became prey to blockaders. One of the most successful was USS Santiago de Cuba, a big and fast sidewheeler armed with ten guns that captured four runners in seven days in April 1862 and a total of sixteen in the war as a whole—eight of them steamers.

By August 1862 Confederate agents and blockade-running captains were shifting most of their operations to Bermuda, where open, deep water gave them a better chance to evade blockaders despite being 100 to 150 miles farther from Wilmington and Charleston. “The port of Nassau has become so dangerous even as a port of destination for arms in British ships,” wrote a Confederate purchasing agent in August 1862, “that I have thought it prudent not to order anything more to that port.”20

THE PRINCIPAL GULF PORT FOR blockade-runners was Mobile, about 600 miles from Havana. After Farragut’s fleet emerged from its frustrating three months in the Mississippi River at the end of July 1862, the new admiral wanted to move against the Alabama port and close it down. With the Confederate abandonment of the old navy yard at Pensacola, Farragut had a new base for coaling and making minor repairs only fifty miles from Mobile Bay. But many of his ships needed major repairs, and his crews were decimated by diseases caught near Vicksburg and by the beginning of the yellow fever season in the Gulf. The Navy Department squelched Farragut’s desire to launch a campaign to enter Mobile Bay. “The present condition of your vessels,” Welles told him in August, and the absolute necessity to retain enough force at New Orleans to hold it precluded “attempting the concentration of an adequate force at Mobile for the reduction of that place.” Instead, Farragut should repair his vessels and concentrate on improving the blockade, especially along the Texas coast, where it had sprung aggravating leaks.21

During the fall, Farragut received some new ships and managed to patch up many of his older ones. The government had a new mission for them. In mid-December Major General Nathaniel P. Banks arrived in New Orleans to replace Benjamin Butler as commander of the Department of the Gulf. Banks brought a large number of army reinforcements with him. His orders were to cooperate with the navy in a new campaign to capture Port Hudson and Vicksburg and to occupy key points in Texas. When Farragut learned of these orders, he grumbled to Fox: “Had I my own way, it would be to attack Mobile first & then have the whole available force for the River & Texas.”22 But despite his prominence as America’s first admiral, he did not get his own way.

Several of Farragut’s gunboats had already seized key points along the Texas coast from the Sabine River on the border with Louisiana south to Corpus Christi. The most important was Galveston, which three Union ships had captured in October 1862. Farragut was well aware that while the navy might be able to take possession of these harbors and inlets, it could not hold them without army troops to fend off land-based Confederate counterattacks. “I have the coast of Texas lined with vessels,” Farragut informed Welles in October. “If I had a military force I would go down and take every place from the Mississippi River to the Rio Grande.”23 General Butler, still in command, promised to send troops to hold Galveston, but they did not come. “I fear that I will find difficulties in procuring the few troops we require to hold the place,” Farragut told the senior naval commander at Galveston.24 Farragut’s fears were justified; the troops that eventually came were too few and too late.

One of Farragut’s biggest headaches in Texas was actually in Mexico: the city of Matamoras (the 1860s spelling), just across the Rio Grande River from Brownsville, Texas. Soon after the war began, a huge increase in trade occurred between Matamoras and other neutral ports, especially Havana. Dozens of ships appeared on the Mexican side of the mouth of the Rio Grande to offload arms and other military supplies and to take on cotton. Union naval officers were certain that the incoming freight was destined for Texas and the cotton came from there. Commander Henry French of the USS Albatross boarded several of the ships and found that “their papers are in order, showing that the cotton has been shipped from Matamoras with certificates showing that it is Mexican property.” But he was convinced that “every ounce of this cotton comes from Brownsville, and merely goes through the form of transfer to Mexican merchants without a bona fide transfer.” French was quite correct. By one estimate, some 320,000 bales of cotton were exported from Matamoras during the war. Even if this estimate was inflated, Matamoras appears to have been the leading port for wartime export of Southern cotton. In September 1862 Commander French asked Farragut what he should do about Matamoros and its cotton trade. “My inclination to lay violent hands on it is very great,” French wrote. “I should enjoy real gratification in being able to find authority for seizing all of their ‘king cotton.’”25

Farragut authorized French to seize these ships and others carrying military contraband into Matamoras but warned him that “you will have to execute that duty with great delicacy toward neutrals, who claim the right to trade with Matamoras, which we do not wish to interfere with when it is legitimately carried on.”26 Farragut’s authority came from Welles, who had instructed captains to stop, search, and seize “all vessels . . . without regard to their clearance or destination” carrying contraband of war intended for or exported by the Confederacy even if under a neutral flag. “The abuse of a foreign flag or the destination of a neutral port must not be permitted to shield the conveyance of munitions to the enemy.”27

Welles here enunciated a corollary to the doctrine of continuous voyage. This doctrine had been established by British blockaders in previous wars to justify seizure of contraband on neutral vessels if there was good reason to believe that it would be shipped onward to an enemy port. Union ships had already exercised that power by capturing some ships traveling from Britain to Bermuda or another neutral port to be transshipped to a blockade-runner. In the case of Matamoras, the contraband was not transshipped by sea to another port but across a river into Texas, so Welles’s corollary came to be known as the doctrine of continuous transportation.

The most celebrated case of this doctrine in the Civil War concerned the British merchant steamer Peterhoff carrying contraband from England to Matamoras, which was captured in February 1863 in the West Indies a thousand miles from Matamoras by the USS Vanderbilt under the command of none other than Charles Wilkes. British merchants protested loudly and the Foreign Office objected mildly. But an American prize court upheld the seizure and the U.S. Supreme Court eventually affirmed it. The British government recorded the precedent and applied it a half century later against goods shipped from neutral America to neutral Holland destined for Germany in World War I.28

Matamoras remained a festering problem for the blockade, however. Some prize courts refused to condemn cargoes when their manifests and other papers seemed genuine. Blockade captains found it difficult to stop and search every ship going to or from Matamoras. Some vessels with clearances from U.S. customs agents in New York, New Orleans, or other American ports seemed to have legitimate permission to trade with Mexico, even though Farragut was certain they were trading with the Confederacy through Matamoras. He denounced American merchants “whose thirst for gain far outstrips their patriotism.” He vowed that “I shall do all in my power to break up this unrighteous traffic by fraudulent clearances . . . and expose the operations of those ruthless speculators who are dishonoring our cause by taking every possible advantage of ‘turning a dollar,’ even at the expense of our country’s honor.”29 The whole issue was complicated by the existence of a civil war in Mexico, in which the French were intervening with thousands of troops. Some of the shipments of arms to Matamoras were in fact intended for one side or the other in that conflict.

Farragut and Welles were convinced that the only way to cut off trade with the Confederacy through Matamoras was to occupy Brownsville and the north bank of the Rio Grande for several miles upriver. Farragut appealed to the Navy Department for shallow-draft gunboats to get over the bar into the Rio Grande, and Welles appealed to the army for troops to occupy Brownsville. Before anything could come of these entreaties, a series of blows struck the Union navy that caused severe setbacks in this theater and elsewhere in the winter of 1862–63.

ON DECEMBER 30, 1862, three companies (260 men) of the 42nd Massachusetts Infantry finally arrived at Galveston to join the five gunboats in possession of that port. The 42nd was perfectly raw, one of the new nine-months militia regiments organized in the fall of 1862. Their presence in Galveston was short-lived. At 5:00 A.M. on New Year’s Day, four Confederate steamboats protected by cotton bales and carrying a thousand men launched a surprise attack. Two of the cottonclads rammed the USS Harriet Lane, while Texas soldiers scrambled aboard and captured her, killing the captain. A Confederate surgeon who watched this action described how “our boys poured in, and the pride of the Yankee Navy was the prize of our Cow-boys.”30 The USS Westfield ran aground, and her commander, William Renshaw, who had led the Union occupation of Galveston three months earlier, ordered her burned to prevent capture. The fire reached the magazine before he could escape, and a dozen sailors plus Renshaw were killed in the explosion. The rest of the Union gunboats fled ignominiously, leaving behind the 260 soldiers and nearly 100 crewmen of the Harriet Lane as prisoners of war.31

Farragut was appalled by this news and disgusted with the poor showing of his sailors. “The shameful conduct of our forces has been one of the severest blows of the war to the Navy,” he admitted to Welles. “The prestige of the gunboats is gone in that quarter until it is again reestablished by some corresponding good conduct on our part.” Assistant Secretary Fox echoed Farragut’s jeremiad. “The disgraceful affair at Galveston has shaken the public confidence in our prestige,” he lamented. “It is too cowardly to place on paper.”32

Farragut’s hope to retrieve the navy’s reputation by “good conduct” suffered more setbacks. He sent his second in command, Commodore Henry H. Bell, with the twenty-six-gun USS Brooklyn and five gunboats to retake Galveston. “The moral effect must be terrible if we don’t take it again,” Farragut warned. “May God grant you success for your own sake and the honor of the Navy.”33 Before Bell could make the attempt, however, none other than Raphael Semmes and the CSS Alabama appeared on the scene. From reading New York newspapers in one of the merchant ships the Alabama captured, Semmes learned of General Banks’s expedition to the Gulf. The newspapers speculated that Galveston was Banks’s objective, so Semmes decided to head there himself with the audacious purpose of getting among Banks’s troop transports and sinking as many as possible.

As it turned out, Banks went to New Orleans. But when Semmes spotted Commodore Bell’s warships outside Galveston on January 11, he quickly modified his plan. He would lure one of the Union ships out to check on the Alabama, flying the British flag and looking from a distance like a blockade-runner. The ruse worked beautifully. The USS Hatteras, a converted sidewheeler ferryboat carrying only five light guns, came out to investigate the strange sail. Turning away as if to escape, the Alabama went slowly enough that at dusk the Hatteras came up to her and hailed: “What Ship is That?” “Her Majesty’s Steamer Petrel” came the answer. A boat put off from the Hatteras to inspect this suspicious vessel, whereupon the raider ran up Confederate colors and fired a broadside into the Hatteras. Stunned and outgunned, the Union ship fought back gamely but was soon full of so many holes that she was sinking. She struck her colors and went to the bottom, while the Alabama rescued her surviving crew and made off at top speed before the rest of the Union fleet learned what had happened. The smaller boat’s crew got away and reported the sinking. Three days later, Farragut had to begin his report to Welles: “It becomes my painful duty to report still another disaster off Galveston.”34

This affair delayed Commodore Bell’s plan to retake Galveston long enough for the Confederates to emplace a sufficient number of guns there to cause him to abandon the plan. The city remained in Southern possession for the rest of the war. Nor did the sinking of the Hatteras drain Farragut’s cup of woe. Four days later, the CSS Florida escaped from Mobile, where she had been corked up by the blockade for more than four months. The night of January 15–16 was so pitch dark and turbulent that the Florida passed within 300 yards of one blockader without being seen. When finally discovered, she was able to outrun her pursuers in a thrilling chase that lasted most of the day on January 16. “Under a heavy press of canvas and steam,” wrote the Florida’s captain, John N. Maffitt, his ship “made 14½ knots an hour.” Within six days, the Florida captured three American merchant vessels whose crews had been unaware of her escape and seized ten more in the next three months.35

Five days after the Florida’s escape, Farragut’s West Gulf Squadron suffered another defeat when two Confederate cottonclad steamers that had worked their way up the inland waterway from Galveston captured the two Union sailing ships holding Sabine Pass on the Louisiana border.36 “I have nothing but disaster to write to the Secretary of the Navy,” sighed Farragut. “Misfortune seldom comes singly,” he reflected in a letter to his wife. “This squadron, as Sam Barron used to say, ‘is eating its dirt now’—Galveston skedaddled, the Hatteras sunk by the Alabama, and now the Oreto [Florida] out on the night of the 16th.”37

News from other theaters did nothing to ease Northern gloom as 1862 made way for 1863. The previous July, Congress had enacted legislation authorizing the navy to take control of the river gunboats (except Alfred Ellet’s ram fleet) from the army. This provision went into effect on October 1, 1862, when Welles upgraded the Western Flotilla to the Mississippi Squadron. He ignored seniority to jump Commander David D. Porter over several captains to take command of the squadron.38 Welles knew that this appointment would give offense to senior officers, especially since Porter was “impressed with and boastful of his own powers, given to exaggeration in everything related to himself . . . reckless, improvident, and too assuming.” But he also “has stirring and positive qualities, is fertile in resources, has great energy,” and “is brave and daring like all of his family.”39 Porter did indeed breathe new life into the Mississippi Squadron, which had fallen into lassitude during the final weeks of Charles Davis’s command. Porter also cooperated actively with the army in a renewed effort to take Vicksburg.

After Henry W. Halleck went to Washington to become general in chief in July 1862, General Ulysses S. Grant was left in command of Union ground forces in west Tennessee and northern Mississippi. With his principal subordinate, Major General William T. Sherman, Grant planned a two-pronged campaign against Vicksburg. With 40,000 troops, Grant would move overland through northern Mississippi while Sherman would load 30,000 soldiers on transports in Memphis and take them down the Mississippi and up the Yazoo River to operate against Vicksburg from that direction. Porter’s gunboats would convoy the transports and lead the way for Sherman’s troops to land and carry the bluffs north of Vicksburg.

The squadron’s first task was to clear out the hundreds of torpedoes that the rebels were known to have planted in the Yazoo. On December 12, two shallow-draft gunboats functioned as minesweepers moving slowly up the river to cut the wires and fish up the mines or to explode them with rifle fire from the deck. The ironclads Cairo and Pittsburg protected the minesweepers by shelling Confederate shore batteries and sharpshooters. Growing impatient with what he considered slow progress in this effort, Lieutenant Commander Thomas Selfridge took the Cairo forward faster in the main channel. He quickly discovered the wrong way to find torpedoes by running on one or possibly two of them (reports varied), which exploded under his hull and sent the Cairo to the bottom in twelve minutes. All of the crew were rescued—as were the guns and iron parts of the Cairo a hundred years later, when they were raised and put on exhibit at Vicksburg National Military Park, where they can be seen today.

The sinking of the Cairo was the first but far from the last success of Confederate torpedoes. Until December 1862, as Porter reported to Welles, “these torpedoes have proved so harmless . . . that officers have not felt that respect for them to which they are entitled.”40 After the loss of the Cairo, they had plenty of respect—perhaps more than necessary, as “torpedo fever” began to eclipse ram fever as a cause of caution among Union officers.

Porter’s gunboats plus two of Ellet’s rams continued to clear out torpedoes without further sinkings. But the task was complicated by Confederate artillery and rifle fire from the bluffs and banks. “We have had lively times up the Yazoo,” Porter wrote to a friend. “We waded through sixteen miles of torpedoes to get at the forts (seven in number); but when we got thus far the fire on the boats from the riflemen in pits dug along the river” killed several men, including Lieutenant William Gwin, one of Porter’s best young officers. “The forts are powerful works, out of the reach of ships, and on high hills, plunging their shot through the upper deck, and the river is so narrow that only one could engage them until the torpedoes could all be removed.”41

The gunboats finally cleared the way for Sherman to land his troops on December 26. Unknown to Porter and Sherman, however, Grant was not coming according to plan. A Confederate cavalry raid had destroyed his supply base at Holly Springs, Mississippi, forcing him to turn back. Another raid farther north by Nathan Bedford Forrest’s cavalry had torn down telegraph wires and prevented Grant from informing Sherman of this reverse. Sherman attacked Chickasaw Bluffs on December 29 and suffered a bloody repulse. The second Vicksburg Campaign came to an even more ignominious end than the first one in July 1862, although this time the Mississippi Squadron under Porter had done all that was asked of it.

The navy suffered one of its saddest losses of the war on the last day of 1862. The cause was the ancient foe of mariners—the weather—rather than a human enemy. The story began with a proposal for a combined attack on Wilmington to shut down what was becoming the chief blockade-running port of the Confederacy. “Though the popular clamor centers upon Charleston,” Fox wrote to Acting Rear Admiral Samuel Phillips Lee on December 15, “I consider Wilmington a more important point.”42

Since assuming command of the North Atlantic Squadron in September, Lee had been taking soundings on the bars at the old and new inlets to the Cape Fear River and scouting obstructions near Fort Caswell to determine which of his vessels might be able to get into the river. He also worked on plans for cooperation with army troops commanded by Major General John G. Foster at New Bern. The soldiers would attack (or carry out a diversion against) Wilmington from the north while his gunboats steamed up the river from the south.

Fox promised Lee the Monitor and the first of the new and slightly larger monitors, the USS Passaic, for this campaign. But it turned out that their draft was too great to get over the bars. Meanwhile, Foster ran into strong Confederate resistance inland from New Bern, making his cooperation impossible. And the “clamor for Charleston” also seemed to override Fox’s priority for Wilmington. Nevertheless, when the Monitor left Hampton Roads under tow by the powerful sidewheeler USS Rhode Island on December 29, their intent was to join Lee’s squadron for an attack on Fort Caswell and then to go on to Charleston, where Admiral Du Pont was requesting all the ironclads he could get for an effort to capture that arch symbol of rebellion.43

The Monitor and the Rhode Island had smooth sailing at first, but as they approached that notorious graveyard of ships off Cape Hatteras on December 30, a gale brewed up that grew stronger as the early darkness came on. “I have been through a night of horrors that would have appalled the stoutest heart,” wrote the Monitor’s paymaster. “The heavy seas rolled over our bow dashing against the pilot house &, surging aft, would strike the solid turret with a force to make it tremble.” The bow “would rise on a huge billow & before she could sink into the intervening hollow, the succeeding wave would strike under her heavy armour with a report like thunder & a violence that threatened to tear [her] apart.” So much water flooded the engine room that the pumps could not keep up and eventually stopped altogether when the rising water doused the fires.

The Monitor signaled the Rhode Island that she was sinking. Courageous sailors from the Rhode Island manned rescue boats. “Words cannot depict the agony of those moments as our little company gathered on top of the turret . . . with a mass of sinking iron beneath them,” peering into the darkness for the boats from the Rhode Island. “Seconds lengthened into hours & minutes into years. Finally the boats arrived,” while “mountains of water were rushing along our decks and foaming along our sides” and the boats “were pitching & tossing about on them and crashing against our sides.”

Somehow, most of the men and officers managed to board the boats, including a fireman who had stayed in the engine room operating the last pump, as he later described it, “until the water was up to my knees and the Cylinders to the Pumping Engines were under Water and stoped [sic].” He went topside and was swept off the deck but grabbed a line and was hauled aboard a boat. He survived with forty-six other crewmen while the famous ironclad slipped below the waves at 1:00 A.M. on December 31. Sixteen men went down with her. “The Monitor is no more,” wrote her paymaster to his wife after his rescue. “What the fire of the enemy failed to do, the elements have accomplished.”44

Thus ended the year 1862, which had begun so promisingly for the Union navy. In some respects, things in the new year would get worse before they got better. The “clamor for Charleston” pushed the navy into a major effort to capture the city—but it turned out to be its most disheartening failure of the war.