Chapter Eight

Unvexed to the Sea

Union gunboats nominally controlled the Mississippi River below Port Hudson and above Helena after the withdrawal of Farragut’s ships and Charles Davis’s Western Flotilla from Vicksburg. But that control remained precarious because of guerrilla attacks on supply steamboats going up and down the river. “The Guerrillas are becoming more alarming every day,” wrote one boat captain in July 1862. “They infest the banks of the river throughout its whole length; such is the fear of them that Pilots cannot be engaged at five hundred dollars a month.”1 Usually mounted and sometimes armed with field artillery as well as muskets, these irregular troops carried out hit-and-run attacks on almost everything that floated. Union commanders responded by organizing convoys of supply boats and civilian steamers accompanied by gunboats to shell the banks whenever they encountered guerrillas.

The convoy system worked well enough as a defensive measure most of the time. But when David D. Porter took command of the Mississippi Squadron in October 1862, he initiated a proactive antiguerrilla strategy. Porter immediately obtained authorization to buy a dozen or more light-draft steamboats and arm them with three or four 24-pound and 12-pound howitzers. The engines and boilers were sheathed with a sufficient thickness of boilerplate iron to protect them against light shore-based artillery, and the decks were screened with thinner boilerplate to protect the crew against rifle fire. With a draft of only two to four feet, these “tinclads” could go far up shallow rivers after guerrillas. By the end of the war, some sixty-five tinclads had served on the western rivers.2

Porter also used Alfred Ellet’s ram fleet as an antiguerrilla force. The Navy Department insisted that the law transferring the river gunboats to the navy included Ellet’s fleet. Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton insisted otherwise. But in November 1862 Stanton lost that battle when Lincoln sided with the navy. Ellet was promoted to brigadier general and his nephew Charles Rivers Ellet became one of the army’s youngest colonels. But even though they remained army officers, Lincoln ordered them to “report to [Acting] Rear Admiral Porter for instructions, and act under his direction.” Out of this ram fleet grew the Marine Brigade, a flotilla of seven boats carrying soldiers and cavalry horses that could be offloaded on riverbanks to pursue guerrillas into the interior.3

Porter took a tough line on guerrillas. Soon after arriving at his new command, he issued a flurry of orders on the subject. Whenever vessels were fired on from shore, the captain should return the fire and then “destroy everything in that neighborhood within reach of his guns,” including “houses supposed to be affording shelter to rebels,” for this was the only way “to repress the outrageous practice of guerrilla warfare.”4 Gunboat captains were not slow to obey these orders. The executive officer of the timberclad USS Tyler reported that when attacked by guerrillas at Ashley’s Landing, Arkansas, “we rounded to and shelled the place, and then landed twenty armed men and burned the cotton gin barns and several dwellings owned by men in the rebel army. . . . They will find they are firing into the wrong parties when they open on us, for we shall burn every house within reach.”5

Porter reported in November 1862 that “Guerrilla warfare has ceased entirely on the banks of the river.”6 This boast was Porter’s usual self-serving gasconade, however, for he was soon compelled to issue another order that “persons taken in the act of firing on unarmed vessels from the banks will be treated as highwaymen and assassins. . . . If this savage and barbarous Confederate custom can not be put a stop to, we will try what virtue there is in hanging.”7 When Confederate officials protested this “savage” order, Porter responded that “the hospital vessel of this squadron was attacked in sight of me, and a volley of musketry fired through the windows. . . . A few days since a band of armed desperadoes jumped on the deck of the tug Hercules and killed in cold blood some of the unoffending crew. . . . If General Pemberton is desirous that the war should be conducted on the principle of humanity and civilization, all he has to do is to issue an order to stop guerrilla warfare.”8 But no threats or actions could stop this warfare, which continued as viciously on the rivers as on land in this theater for the rest of the war.

Another task of Porter’s squadron and Farragut’s gunboats was to prevent Confederate commerce across the Mississippi in either direction. Success in this endeavor was mixed, but the blockade on the Mississippi tightened over time just as the saltwater blockade continued to tighten as the war went on. In October 1862 four gunboats on the lower Mississippi captured an unusual prize. They discovered a herd of 1,500 cattle on the riverbank that had been driven from Texas, intended for Confederate armies in the East. Sailors rounded them up and sent for five transports from New Orleans to come and take them to a suitable pasture near the city. About 200 of the cattle were too unmanageable to get on board, so the captains hired contrabands to drive them down the bank accompanied by a gunboat steaming alongside for protection. Guerrillas ambushed the transports and killed or wounded a few sailors, but the gunboats drove them off. All of the cattle got through, including those that went by land. The senior officer was gleeful about his success as a cattle rustler, “performed at some risk in the midst of a country hostile and alive with guerrillas and armed bands of enemies.” He admitted that this feat was “somewhat a novel act of duty for the Navy.”9 One can be certain that these sailors and contrabands ate well for a while.

ONE THIN GLEAM OF CHEER penetrated the gloom of setbacks for the Union navy in the winter of 1862–63. After the repulse of his attack on Chickasaw Bluffs in December, General William T. Sherman proposed a combined operation against Fort Hindman at Arkansas Post forty miles up the Arkansas River. Success there might boost shattered Northern morale, Sherman argued, and prevent enemy use of the river to send supplies and reinforcements to Vicksburg. Porter agreed, and ten gunboats escorting troop transports carrying 30,000 soldiers proceeded up the Arkansas River in the second week of January 1863. The political general John A. McClernand, who outranked Sherman, arrived on the scene and took command of the troops. When Grant in Memphis learned of this expedition, not realizing that it had been his friend Sherman’s idea, he complained in a telegram to General Henry W. Halleck that “McClernand has . . . gone on a wild-goose chase to the Post of Arkansas.”10

If unsuccessful, it might well have gone down as a wild-goose chase. But while the army troops invested the eleven-gun fort, the gunboats, led by three of the Eads city-class ironclads, closed to within 400 yards of the fort and pounded it unmercifully with their big guns. A soldier serving as a volunteer on the USS Monarch, one of the Ellet rams, described this bombardment. “Such a terrific scene I have never witnessed,” he wrote to his sister. “The fort was riddled and torn to pieces with the shells. The ironclads, which could venture up closer, shot into their portholes and into the mouths of their cannon, bursting their cannon and dismounting them. When most of their batteries were silenced, two of the light draft boats and our boat was ordered to run the blockade to cut off the retreat of the rebels above the F[or]t.” Trapped between army troops on three sides and the gunboats in their rear, the Confederate garrison of 5,000 men surrendered on January 11. At the cost of a thousand Union killed and wounded (almost all in the army), this combined operation won a minor but morale-boosting victory that became a springboard for a renewed campaign against Vicksburg.11

The ironclads and tinclads suffered relatively little damage because Porter had ordered their pilothouses and casemates greased with tallow and ships’ slush, which caused enemy shots that hit at an angle to glance off. It is unclear whether Porter was aware that the Confederates had similarly greased the Virginia almost a year earlier. In any event, this practice spread through the Union navy after Porter reported its success at Arkansas Post. The experience could be quite unpleasant for sailors, however, especially in hot weather when the tallow dripped onto the deck, and it was no joy to clean up after action. But it saved lives and reduced damage to ships.12

BY 1863 THE CAPTURE OF Vicksburg and Port Hudson had become two of the most important objectives of Union strategy. When General Nathaniel P. Banks departed for his new command at New Orleans in November 1862, General in Chief Halleck instructed him that “the President regards the opening of the Mississippi River as the first and most important of all our military and naval operations.” Lincoln believed that “if Vicksburg can be taken and the Mississippi kept open it seems to me [they] will be about the most important fruits of the campaigns yet set in motion.”13

At the end of January, Grant came down to Milliken’s Bend on the Mississippi, about twenty miles upriver from Vicksburg, to make it his headquarters for the campaign against the Confederate bastion. The previous summer, Halleck had told Farragut that he could spare no troops to help the navy take Vicksburg. Now he informed Grant that “the eyes and hopes of the whole country are now directed to your army. . . . The opening of the Mississippi River will be to us of more advantage than the capture of forty Richmonds.”14

Grant knew that interservice cooperation would be essential in such a campaign. Even though by tradition and law he could not give orders to the navy, nor Porter to the army, the two commanders got on well with each other, just as Grant and Foote had worked well together against Forts Henry and Donelson a year earlier. The task at Vicksburg was complicated by geography and topography. Situated on a 200-foot bluff commanding the lower end of an S curve in the river, Vicksburg’s defenses made a direct assault from that direction impossible. Extending north from Vicksburg to Memphis, a chain of hills formed an arc of 200 miles and closed in the Delta, low-lying land averaging about fifty miles in width and laced with swamps, rivers, and thick forests. The only dry land suitable for military operations against Vicksburg stretched to the south and east. Grant’s problem was to get his army there with enough supplies to sustain a campaign against the land side of the Vicksburg defenses while the navy shelled them from the river and kept open Grant’s communications with the North.

The planning for a Vicksburg Campaign in early 1863 included operations against the Confederacy’s other major river bastion at Port Hudson, 250 river miles to the south. In the end these actions turned out to be two separate though related campaigns: Grant and Porter against Vicksburg, Banks and Farragut against Port Hudson. But Porter initially conceived of them as a single operation. On February 2 he sent the famous Ellet ram Queen of the West past the Vicksburg batteries to roam downriver and capture Confederate supply steamers carrying provisions from the Red River into the Mississippi for the garrison at Port Hudson. The commander of the Queen was nineteen-year-old Charles Rivers Ellet, son of the creator of the ram fleet who had been mortally wounded at the moment of triumph in the Battle of Memphis the previous June. “I can not speak too highly of this gallant and daring officer,” Porter told Welles. “The only trouble I have is to hold him in and keep him out of danger. He will undertake anything I wish him to without asking questions, and these are the kind of men I like to command.”15

As the Queen ran past Vicksburg, she took several hits from Confederate guns when she diverted to ram the steamer City of Vicksburg at the wharf (it later sank). Ellet continued downriver and stopped out of range to repair the damage. During the next three days, the Queen captured and destroyed three Confederate steamers carrying $200,000 worth of provisions for Port Hudson. She continued into the Red River and captured another steamboat, Era No. 5, on February 14. Seizing the pilot, Ellet forced him to navigate the Queen farther up the river, where he ran her into an ambush by a Confederate battery of 32-pounders. Ellet ordered the pilot to back the Queen downstream out of range. He backed her instead onto a sandbar that grounded her at point-blank range. The Queen’s crew jumped overboard and floated down the river on cotton bales to the Era No. 5, leaving the Queen to be captured. Because there were wounded aboard, Ellet could not set fire to the Queen to prevent her capture.16

Meanwhile, the initial reports of Ellet’s achievements caused an elated Porter to reinforce success by sending one of his new ironclads, the USS Indianola, past the Vicksburg batteries on February 12 to join the Queen in playing havoc with enemy shipping. Carrying two 11-inch and two 9-inch guns, the Indianola should have been more than a match for anything on the river. As she steamed down from Vicksburg, the Indianola met the Era No. 5 coming up pursued by a fast Confederate gunboat, the William H. Webb. Ellet informed the Indianola’s captain of the situation and the two boats headed downstream to attack the Webb, whose captain turned around and fled when he spotted the formidable ironclad.

Expecting that Porter would send down another gunboat when Ellet told him what had happened, the Indianola remained below Vicksburg to blockade the mouth of the Red River. But the Confederates had repaired the captured Queen of the West. Along with the Webb and two smaller gunboats loaded with infantry for boarding, the Queen came down the Red River to attack the Indianola, whose captain decided that the odds were too great to fight. He headed back up the Mississippi, chased by the faster Confederate vessels. Waiting until dark on February 24 to minimize the accuracy of the Indianola’s guns, they attacked by repeatedly ramming the ironclad, punching holes below the waterline and splintering one of her sidewheels. As the Indianola sank in shallow water near the bank, the captain surrendered. Jubilant Confederates prepared to raise and repair her. With the Webb and the Queen, the Indianola would give them a powerful squadron to augment their control of the river between Vicksburg and Port Hudson.17

Porter confessed his mortification in a report to Welles. “There is no use to conceal the fact, but this has . . . been the most humiliating affair that has occurred during this rebellion.”18 But Porter had a trick up his sleeve. He directed sailors to build a wooden superstructure on an old coal barge—complete with paddle-wheel boxes, large logs protruding from fake gunports, and two sets of barrels piled on top of each other burning tar to simulate smokestacks—and set the apparition adrift downriver. Coated with tar, this dummy ironclad loomed out of the mist on February 26 looking like a ship of doom to the men in the four Confederate gunboats protecting a working party trying to raise the Indianola. The gunboats fled downriver and the working party blew up the Indianola to prevent her recapture. “With the exception of the wine and liquor stores of the Indianola, nothing was saved,” wrote a Confederate colonel. “The valuable armament, the large supplies of powder, shot, and shell, are all lost.”19

The next day, several Confederates rowed a skiff out to investigate the false ironclad, which had stuck on a sandbar. On the wheelhouse they found a hand-lettered sign: “Deluded people, cave in.” The Indianola “would have been a small army to us,” lamented the Vicksburg Whig. “Who is to blame for this piece of folly?” Nobody came forward to take the blame.20

Confederates still controlled that stretch of the Mississippi, however, and supplies for both Vicksburg and Port Hudson still came down the Red River from Texas and Louisiana. Because most of Porter’s remaining vessels were cooperating with the army’s attempts to get at Vicksburg through Delta waterways to the north, Admiral Farragut decided to move into Confederate territory north of Port Hudson. “Porter has allowed his boats to come down one at a time, and they have been captured,” Farragut told his second in command, “which compels me to go up and recapture the whole, or be sunk in the attempt. The whole country will be in arms if we do not do something.”21

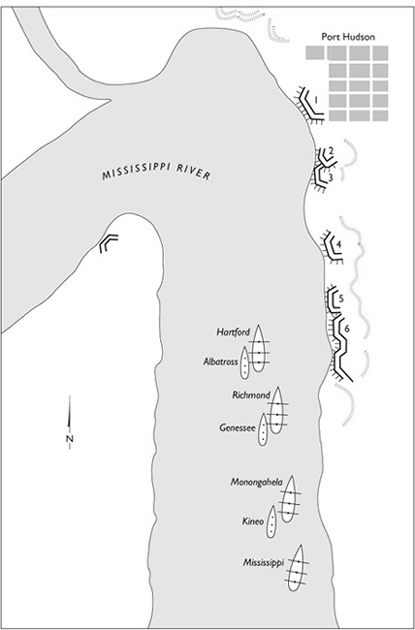

On the night of March 14–15, Farragut, in his beloved flagship, Hartford, led seven ships in an attempt to steam past Port Hudson. Behind the Hartford came two other steam sloops, the USS Richmond and the new USS Monongahela. Lashed to the port sides (away from Port Hudson’s guns) of each was a smaller river gunboat. These three pairs were followed by the venerable sidewheeler USS Mississippi. They were supported by two other gunboats and six mortar schooners that poured shells into enemy batteries in an effort to keep down their fire on Farragut’s ships as they struggled upriver against the current.

The night was dark and still, with an atmospheric inversion that prevented the dissipation of smoke from the funnels and guns and made it extremely difficult for the pilots to see where they were going. As they approached the hairpin bend in the river, the Hartford and her consort, the USS Albatross, ran aground. The Hartford’s surgeon, who kept a running account in a small diary strapped to his left wrist, described in spare prose what happened next: “Got off again in ten minutes. Going ahead fast with very heavy firing. The first wounded brought below. Our escape so far has

The Attempt to Pass Port Hudson, March 14–15, 1863

been miraculous. Midnight—Our ship has been struck heavily and frequently by shot from very heavy guns on shore and we are delivering quick broadsides at intervals. Twelve-thirty—Passed all of the batteries. Cheered ship!”22

But the rest of the fleet had no reason to cheer. Captain James Alden of the Richmond described her fate and that of her consort USS Genessee: “As we were turning the point almost past the upper batteries we received a shot in our boilers . . . and another shot went through our steam drum. Our steam was all gone,” and the Genessee was not powerful enough to keep the pair going against the current. “Torpedoes were exploding all around us, throwing water as high as the tops[;] . . . shells were causing great havoc on our decks; the groans of the wounded and the shrieks of the dying were awful. The decks were covered with blood.”23 The two ships finally drifted downriver and out of the fight. Behind them, the Monongahela and her consort also went aground, and the crank pin of the Monongahela’s engine broke when she backed off, so they also drifted downstream. Bringing up the rear, the Mississippi then ran aground in the smoky darkness. Port Hudson’s guns now could concentrate on her and pounded her relentlessly. The captain ordered the crew to abandon ship before she blew up. Most of them got away, but sixty-four were killed or missing.24

When Farragut sat down the next day to write his report to Welles, he began with the words: “It becomes my duty again to report disaster to my fleet.”25 Only later did he learn that except for the Mississippi, the other ships had survived with reparable damage. And Welles did not think it a disaster at all, but a valiant action in which the Hartford and the Albatross had gained a position to contest control of this 250-mile stretch of the river with the Confederates. Assistant Secretary Fox no doubt gladdened Farragut’s heart with the assurance that “the President thinks the importance of keeping a force of strength in this part of the river is so great that he fully approves of your proceeding.”26

At Vicksburg, General Grant sent a loaded coal barge drifting past the batteries at night down to Farragut. Charles Rivers Ellet took two of his rams past Vicksburg two days later. They got started late, so it was daylight when they passed the batteries, which sank the Lancaster and damaged Ellet’s flagship, Switzerland. She was repaired and joined Farragut’s two ships at the mouth of the Red River to choke off supplies to Vicksburg and Port Hudson. They soon learned that they would not have to worry about a challenge from the Queen of the West. She had gone from the Red River into the Atchafalaya River, where on April 14 the USS Calhoun sank the Queen with her first shot from a 30-pound Parrott rifle at a distance of three miles.27

When General Banks finally brought Port Hudson under attack and siege in May 1863, a dozen or more of Farragut’s warships both below and above helped bombard the Confederate defenses day and night for nearly two months. In looking back on these operations, however, Farragut believed that his most important contribution to the campaign was the initial passage of Port Hudson in March and the subsequent blockade of the Red River. “My last dash past Port Hudson was the best thing I ever did, except taking New Orleans,” he wrote to his wife in July. “It assisted materially in the fall of Vicksburg and Port Hudson.”28

THE FALL OF VICKSBURG did not come easily. While Farragut was performing his heroics downriver, Porter and Grant appeared to be floundering in their efforts to get troops and supplies onto dry land east of Vicksburg. Soldiers and contrabands resumed digging the canal across the De Soto Peninsula formed by the loop in the river to provide a new channel to bypass Vicksburg altogether. If it worked, gunboats and troop transports could get downriver out of range of Confederate batteries and cross troops to the east bank. Porter had little faith in this enterprise because the start of the canal was in the wrong place—where the current formed an eddy rather than scouring into the opening. And the Confederates proved that they could shift guns to command the canal’s exit by firing on a dredging machine and forcing it to decamp.

The canal was eventually abandoned. In the meantime, one of Grant’s corps tried to carve out a new navigation channel through a maze of bayous, lakes, and tributary rivers in Louisiana that could get boats through to the Red River and then into the Mississippi far south of Vicksburg. This effort also proved fruitless.

More promising was the so-called Yazoo Pass Expedition, in which several of Porter’s gunboats, including two river ironclads, played an important part. Army engineers blew up a levee opposite Helena, allowing roiling water from the Mississippi to flood into a series of streams leading to the Tallahatchie River. This river in turn flowed into the Yazoo, theoretically making these waterways navigable to landing places northeast of Vicksburg near the place where Sherman’s troops had assaulted the bluffs the previous December.

Porter’s initial reports about this expedition were optimistic. But the lieutenant commander in charge of the gunboats was ill when the operation began, and his experiences soon made him sicker. His vessels continually ran aground; overhanging trees damaged their chimneys (smokestacks); enemy axemen chopped down trees to block the channel; and sharp bends in the river required the boats to back and fill. At one bend in the Tallahatchie halfway between Helena and Vicksburg, the Confederates erected a fort of dirt, sandbags, and cotton bales that commanded a straight channel only wide enough for one gunboat to use its bow guns. The surrounding swamplands made an assault by the expedition’s 5,000 infantry difficult if not impossible—though Porter thought they should have tried. He blamed the army for the failure of this operation—as was becoming his habit. “If you could only once have to co-operate with the soldiers and see the inefficiency of some of them,” he told Fox privately, “you would wonder that we ever did anything together.”29

Porter changed his tune about the army during another operation commanded personally by himself and his favorite general, William T. Sherman. Labeled the Steele’s Bayou Expedition, it involved pushing eleven gunboats (including four of the Eads city-class ironclads) through a series of bayous and rivers that were often not much wider than the boats. Tough willow trees with interlocking branches over the water slowed their progress to about one mile per hour. Confederates again felled trees across streams ahead and behind the gunboats, while possums, raccoons, snakes, and all manner of wildlife dropped from branches onto decks and sailors swept them off with brooms. Confederate sharpshooters along the banks fired at anyone who showed himself on deck.

This nightmare threatened to end badly for Porter. He penned a hasty note to Sherman and gave it to a contraband for delivery to the troop transports several miles to the rear: “Dear Sherman, Hurry up, for Heaven’s sake. I never knew how helpless an ironclad could be steaming around through the woods without an army to back her.”30 Sherman disembarked his soldiers to wade through swamps and drive off the Confederates. Recognizing that the expedition had failed, Porter had his sailors unship the rudders, and the gunboats backed slowly downstream the way they had come and returned after “the most severe labor officers and men ever went through,” he reported to Welles on March 26. “With the end of this expedition ends all my hopes of getting into Vicksburg in this direction.”31

Grant was discouraged by these failures. And the country was discouraged with Grant, who came under attack from newspapers and politicians of all persuasions. Lincoln stood by Grant and Porter, but Fox reported confidentially that the president “is rather disgusted with all the flanking expeditions and predicted their failure from the first.” On March 29 Lincoln dropped in to John Dahlgren’s office at the Washington Navy Yard. “He looks thin and badly,” reported Dahlgren, “and is very nervous. Complained of everything. They were doing nothing at Vicksburg or Charleston.”32

Porter thought Grant should take his army back to Memphis and launch an overland campaign from there against Vicksburg.33 So did Sherman. But Grant had tried that route without success back in December. Instead, he proposed a different plan that he had been forming in his mind for some time. He would march troops south on the west side of the river, building roads as they went. He asked Porter to run enough gunboats past the Vicksburg batteries to spearhead a crossing of the troops to the east bank and to protect supply vessels that would sustain Grant’s operations against Vicksburg from that direction. Porter was reluctant. He told Grant that “when these gunboats once go below we give up all hopes of ever getting them up again.” But when Welles learned of Grant’s request, he pressed Porter to comply with it. Success in such a movement would be “the severest blow that can be struck upon the enemy,” Welles told Porter, and was therefore “worth all the risk.” Porter finally gave in, though as he later informed Fox, “I am quite depressed with this adventure, which as you know never met with my approval—still urged by the Army on one side, the President’s wishes and the hints of the Secretary [Welles] that it was most necessary, I had to come.”34

Porter prepared seven river ironclads (including two new ones), a wooden gunboat, and three transports to run the batteries on the moonless night of April 16–17. Loaded coal barges were lashed to their port sides, and they were also protected by heavy logs and bales of wet hay to absorb shells and snuff their fuses. At 11:00 P.M. the squadron drifted silently downriver with paddle wheels barely turning for steerageway. Suddenly, the river was brightly lit with bonfires set by Confederate pickets along the bank who had spotted the boats. They crowded on steam and fired blindly at the Vicksburg bluffs, where the dug-in batteries sent off 525 rounds at the fleet, only sixty-eight of them finding a target because “we ran the Vicksburg shore so close that they overshot us most of the time,” according to a master’s mate on one of the boats. All of the gunboats and two of the three transports got through with only fourteen wounded. One of the transports went to the bottom (the crew was rescued); another tried to turn back, but Porter had stationed the new ironclad USS Tuscumbia at the rear to prevent precisely such misbehavior by its civilian crew, and the gunboat herded it onward.

In a private letter to Fox, Porter reported that his fleet had suffered more damage than he had stated in his official report, “as it will not do to let the enemy know how often they hit us, and show how vulnerable we are. Their heavy shot walked right through us, as if we were made of putty.” Six nights later, five of seven transports got through with supplies and ammunition; one was sunk and another turned back. They were manned by army volunteers because their regular crews had refused to go.35

Grant now had two-thirds of his army below Vicksburg supported by a powerful gunboat fleet. (Sherman’s corps had gone up the Yazoo River to make a diversionary feint.) Grant planned to cross his troops to the east bank at Grand Gulf forty miles below Vicksburg, where there were road and rail connections to the interior of Mississippi. The Confederates had fortified Grand Gulf with two heavy batteries, so on April 29 Porter’s gunboats pounded these defenses to prepare the way for a landing by troops. They silenced several of the guns but in return took more of a beating than in the run past Vicksburg, with twenty-four killed and fifty-six wounded. “It was the most difficult portion of the river in which to manage an ironclad,” Porter reported, “strong currents (running 6 knots) and strong eddies turning them round and round, making them fair targets.”36

Meanwhile, a contraband had informed Grant of an unguarded crossing another ten miles downriver, with a road leading to Port Gibson and the rear of Grand Gulf. That night, the entire fleet ran past the remaining guns at Grand Gulf, with the gunboats providing covering fire while the supply transports slipped behind them with full steam and the current speeding them through safely.37 As the vessels began ferrying the troops across the river on April 30, Grant stepped onto Mississippi soil with “a degree of relief scarcely ever equaled since,” as he recalled it more than twenty years later. “I was now in the enemy’s country, with a vast river and the stronghold of Vicksburg between me and my base of supplies. But I was on dry ground on the same side of the river with the enemy. All of the campaigns, labors, hardships and exposures, from the month of December previous . . . were for the accomplishment of this one object.”38 And it could not have been accomplished without the navy.

During the next three weeks, Grant’s army marched 130 miles, won five battles over detachments of the Confederate Army of Mississippi that if united would have been nearly as large as the 44,000 men in Grant’s Army of the Tennessee, and penned up the Confederates in the Vicksburg defenses. While Grant was carrying out this whirlwind campaign, Porter took most of his fleet up the Red River as far as Alexandria, destroying the batteries at abandoned Fort De Russy on the way. When part of General Banks’s army occupied Alexandria while the rest invested Port Hudson, Porter brought most of his squadron back to Vicksburg to support Grant. He left several gunboats in the Red River to keep up the blockade of that Confederate supply route.

By the end of May 1863, the two separate armies of Grant and Banks had Vicksburg and Port Hudson under siege by land, and the naval squadrons of Porter and Farragut sealed them off by water. The big guns of the warships and mortar boats of both squadrons joined the armies’ field artillery to pound the Confederate defenses around the clock.39 The Vicksburg batteries gave as good as they got during the early days of the siege. Grant asked Porter for fire support during his May 22 assault on Confederate lines. Porter cheerfully complied, and his gunboats absorbed a heavy cannonade in return. “It is useless to try to remember the different times the vessels were hit,” wrote a master’s mate on Porter’s flagship.40 Five days later, a plunging shot through the deck of the USS Cincinnati sank this hard-luck ironclad for the second time (she had been raised after Confederate rams had holed her at Plum Point Bend a year earlier). Like Lazarus, however, the Cincinnati was raised from the dead and refitted once more after the fall of Vicksburg. She lived to fight again.41

While maintaining the stranglehold on Vicksburg, Porter had enough gunboats to carry out auxiliary operations. Learning that two Confederate brigades were approaching Milliken’s Bend and anticipating a diversionary attack on the two uncompleted black regiments posted there, Porter sent the new ironclad USS Choctaw and veteran timberclad USS Lexington to the bend. On June 7 the Confederates drove outnumbered and untrained black soldiers back over the levee to the river, where the gunboats “opened on the rebels with shell, grape, and canister,” Porter reported, “and they fled in wild confusion, not knowing the gunboats were there or expecting such a reception. They retreated rapidly to the woods and soon disappeared. Eighty dead rebels were left on the ground, and our trenches were packed with the dead bodies of the blacks, who stood at their post like men.”42

At about the same time, Porter sent gunboats up the Yazoo River to capture Confederate transports after the Southerners had evacuated their navy yard and destroyed uncompleted ironclads they had been building there. A month later the Confederates returned, so Porter sent another expedition to accompany a division of Union soldiers to capture and destroy the base for good. They succeeded, though two torpedoes exploded under the Eads ironclad USS Baron de Kalb and sent her to the bottom. Nevertheless, Porter claimed, “we are somewhat compensated for the loss of the de Kalb by the handsome results of the expedition,” which included the seizure of 3,000 bales of cotton worth several times the cost of the de Kalb. The Confederates also sank or blew up nineteen steamboats to prevent their capture. “There are no more steamers on the Yazoo,” Porter informed Welles in August. “The large fleet that sought refuge there, as the safest place in rebeldom, have all been destroyed.”43

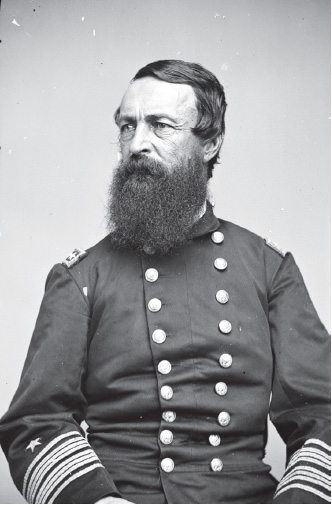

David Dixon Porter, photographed after his promotion to rear admiral. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress)

By then, there were no more Confederates except civilians at Vicksburg either. After a siege of forty-seven days, General John C. Pemberton surrendered its 30,000 defenders to Grant on the Fourth of July. Porter totaled up the navy’s contribution to this result in the way of firepower: 7,000 mortar shells rained on Vicksburg; 4,500 shot and shells fired by gunboats; another 4,500 rounds fired by naval guns landed on shore and manned by sailors; and 6,000 shot and shells supplied to army guns.44

Porter also rushed the first news of Vicksburg’s surrender to Washington. He sent a fast gunboat up the river to the nearest available telegraph office, at Cairo, which dispatched the message to Welles on July 7. The secretary went immediately to the White House to give Lincoln the news. Coming just three days after the president had learned of the outcome at Gettysburg—and when he was beginning to fret about General George G. Meade’s caution in pursuit of the retreating Confederates—the telegram from Porter produced unalloyed pleasure. Putting his long arm around Welles, Lincoln exclaimed: “What can we do for the Secretary of the Navy for this glorious intelligence? He is always giving us good news. I cannot, in words, tell you my joy over this result. It is great, Mr. Welles, it is great!”45

Once Vicksburg fell, the fate of Port Hudson was sealed. Its commander surrendered the post and its 7,000 defenders to General Banks on July 9. The Mississippi now did flow unvexed to the sea—except for Confederate guerrillas, who continued to be very vexatious indeed. Lincoln promoted Porter to rear admiral, and Welles gave him control of the entire Mississippi down to New Orleans. Farragut enthusiastically endorsed this reduction in the scope of his command, delighted to get himself and his ships back to salt water.46

After the capture of Vicksburg and Port Hudson, what next for the soldiers and sailors who had accomplished these results? Grant and Banks wanted to mount a campaign against Mobile. Farragut had wished to go after that objective for more than a year. But other priorities eclipsed Mobile for the time being. Another year would pass before Farragut finally got his chance. The great Union victories in July 1863 had swung the momentum over to the North again, but the war was far from over, and the navies of both sides continued to confront each other at home and abroad.