Chapter Nine

Ironclads, Torpedoes, and Salt, 1863–1864

The nation of Mexico was plagued by its own civil war during the same years as the American conflict. Unlike the United States, however, the Mexican government could not prevent foreign intervention in its troubles. In December 1861 a joint military expedition by France, Britain, and Spain invaded Mexico to force the payment of debts owed to citizens of those countries. The British and Spanish contingents pulled out after negotiating a settlement, but Napoleon III kept French troops there and increased their numbers to 35,000 by 1863. They helped the forces of the church and large landowners overthrow the liberal government of Benito Juárez in June 1863. Napoleon began planning to install the Archduke Ferdinand Maximilian of Austria as emperor of Mexico in an audacious bid to restore the French suzerainty in the New World that his uncle Napoleon Bonaparte had given up when he sold Louisiana to the United States in 1803.

Confederates began fishing in these troubled waters. They made contacts with anti-Juárez chieftains in northern Mexico who profited from the contraband trade across the Rio Grande with the Confederacy. Southern diplomats sought an agreement with France whereby the Confederacy would recognize Napoleon’s puppet regime in Mexico in return for French recognition of the Confederacy.

This pact was never consummated, but in the summer of 1863 an alarmed Lincoln administration was afraid it might come to pass. Secretary of State Seward convinced the president that the United States must send a warning message to France by invading Texas. Not only was the French presence in Mexico a violation of the Monroe Doctrine; the possibility of French-Confederate cooperation also represented a clear and present danger to the Union cause. When Generals Grant and Banks, backed by Admiral Farragut, proposed a campaign against Mobile after the fall of Vicksburg, therefore, Lincoln told them that Mobile must wait until they had planted the American flag firmly in Texas. A campaign against Mobile, Lincoln told Grant, “would appear tempting to me also, were it not that in view of recent events in Mexico, I am greatly impressed with the importance of re-establishing the national authority in Western [eastern?] Texas as soon as possible.”1

The troops for such a campaign would come from Banks’s Army of the Gulf and the supporting naval force from Farragut’s squadron. Banks decided to invade Texas via Sabine Pass—the outlet of two Texas rivers to the Gulf on the border with Louisiana—and to move inland to cut the railroad between Beaumont and Houston. He selected Major General William B. Franklin to command 5,000 troops for this expedition. This choice did not augur well for success. A McClellan favorite who had botched his mission to rescue the Harpers Ferry garrison in the Antietam campaign and had failed to reinforce success at Fredericksburg, Franklin had been exiled to Louisiana by Lincoln for intriguing to get McClellan restored to command. Farragut’s warships were also in poor shape for this campaign. On the eve of departing for the North in the Hartford for a much-needed rest for himself and repairs to his flagship, Farragut warned Welles that most of his ships were worn out or damaged and in need of repairs before they could become efficient again.2

The acting squadron commander in Farragut’s absence was Henry H. Bell, who assigned four small gunboats to support Franklin’s troops. These vessels were converted river steamboats, sidewheelers with “decayed frames and weak machinery, constantly out of repair,” in the words of General Banks. But they were the only available vessels with a shallow enough draft to get over the bar into the river to attack the six-gun Confederate battery sited to control both channels.3

Farragut happened to be visiting Welles at the Navy Department when they learned of the planned attack. The admiral predicted failure. “Army officers have an impression that naval vessels can do anything,” he said. They would expect the gunboats to silence the battery so they could walk ashore. Farragut thought Franklin should land his troops out of range of the battery and attack it from the rear while the gunboats shelled it from the water. “But that is not the plan,” Farragut lamented. “The soldiers are not to land until the navy has done an impossibility, with such boats,” so “you may expect to hear of disaster.”4

Farragut’s gloomy prophecy proved accurate. The gunboats attacked on September 8. Firing with the benefit of preset range markers, the Confederate guns knocked out two of them with shots through one’s boiler and the other’s steam drum. Another gunboat ran aground, and the fourth turned tail when her captain saw what had happened to the others. Just as Farragut had predicted, Franklin waited for the gunboats to silence the battery instead of cooperating with them. When the gunboats were silenced instead, Franklin’s troop transports returned to New Orleans without a single one of his soldiers having set foot on Texas soil. The forty-seven Texas gunners commanded by a Houston saloon keeper named Dick Dowling became Southern folk heroes for having put more than 5,000 Yankees to flight and capturing two steamers.5

The ignominy of this defeat was hard to live down. But General Banks and the navy did something to retrieve their reputations by carrying out an operation long urged by the Navy Department: occupying the north bank of the Rio Grande at Brownsville to cut off the contraband trade through Matamoras. In November 1863, 6,000 soldiers, commanded by a general with the imposing name of Napoleon Jackson Tecumseh Dana and escorted by three powerful warships, splashed ashore near Brownsville. The troops moved upriver almost 100 miles to Rio Grande City, driving Confederate defenders before them. Gunboats also pushed up the coast along the inland waterway nearly 300 miles to Port Lavaca.6

These successes severely curtailed the contraband trade across the Rio Grande as well as blockade-running into and out of ports in southeast Texas. The Confederates still managed to get some war matériel in and cotton out through Matamoras, but now they had to go far inland to Laredo to do it. Because of the fall of Vicksburg and Port Hudson and the active patrolling of the Mississippi by David Porter’s tinclads, almost none of this freight could get across the big river, so the reduced contraband trade was confined to the trans-Mississippi theater. But this incursion into Texas had less impact on the Confederate war effort than the capture of Mobile Bay would have had. And it had no apparent impact at all on the French in Mexico or Napoleon III in Paris.

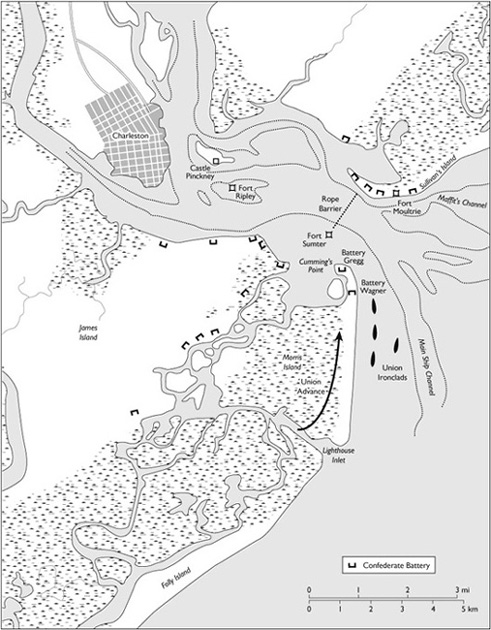

TEXAS WAS FAR AWAY from the center of gravity in the military campaigns of both sides. For the Union navy and its Confederate adversaries on shore, Charleston remained the main focus of attention in the latter half of 1863. Most of the navy’s monitors plus the ironclad frigate New Ironsides remained there, and the harbor defenses commanded by General Pierre G. T. Beauregard featured the largest concentration of fortified heavy artillery in the Confederacy.

When Rear Admiral John A. Dahlgren took command of the South Atlantic Squadron on July 6, he immediately began to plan a joint operation with Major General Quincy Gillmore to assault Confederate defenses on the south end of Morris Island. They intended to land troops there for an advance against Battery Wagner on the north end as the first step in a grinding fort-by-fort advance toward Charleston. Supported by the 11-inch and 15-inch Dahlgren guns in four monitors, with their inventor in his flagship USS Catskill, blue-clad soldiers crossed Lighthouse Inlet in barges and launches and splashed ashore on the morning of July 10 to attack Confederate batteries and infantry already crippled or demoralized by the monitors’ fire.

During a blistering hot day in which soldiers on shore and sailors in the ironclads suffered more casualties from heatstroke than from enemy fire, Union soldiers moved up the island accompanied by the monitors staying as close to shore as they could and pouring grapeshot into Confederate ranks. As the ships and soldiers approached Battery Wagner, Confederate guns in that large earthwork reinforced with palmetto logs zeroed in on the Catskill flying the admiral’s flag. The least damaged of the monitors in the April 7 attack on Fort Sumter, the Catskill took the most hits on July 10—sixty in all. “Our attack on Sumter before is nothing to this,” wrote the Catskill’s executive officer. “Thank God we have all come out safely, except two or three wounded on this vessel & several used up from exertion & the heat.” Dahlgren narrowly escaped injury when a bolt in the pilothouse flew past him after a direct hit by an enemy shot.7

For the next week, the monitors and the New Ironsides, with its 150-pound pivot rifles and 11-inch guns in broadside, pounded Battery Wagner night and day while Gillmore’s shore-based artillery seconded their efforts. (The Federals called it Fort Wagner because from their perspective it appeared to be an enclosed work.) General Beauregard tried to get the Confederate naval commander at Charleston, Captain John R. Tucker, to send his two ironclads against the Union fleet. On July 12 Beauregard told Tucker that it had “become an urgent necessity to destroy, if possible, part or all of these [enemy] ironclads” by a night attack. Six days later, he again pleaded with Tucker to do something. “I consider it of the utmost importance to the defenses of the works at the entrance to the harbor that some effort should be made to sink either the Ironsides or one of the monitors.” But Tucker did not want to risk his ships. They remained at anchor near Fort Sumter.8

The Attack on Morris Island and Battery Wagner

On July 18 the bombardment of Battery Wagner was especially heavy to soften it up for an infantry assault that evening. “Such a crashing of shells and thunder of cannon and flying of sand and earth into the air” he had never seen, wrote Dahlgren in his diary. As the tide rose, he had the monitors move to within 300 yards of shore, while the New Ironsides, with its deeper draft, remained farther out and fired over them. “The gunnery was very fine,” declared Dahlgren, “the shells of the ‘Ironsides’ going right over the ‘Montauk,’ so we had it all our own way.” At dusk the Union infantry, led by the celebrated black regiment, the 54th Massachusetts, began their attack, and the Federals no longer had it all their own way. “There could be no more help from us,” noted Dahlgren, “for it was dark and we might kill friend as well as foe.”9 Desperate fighting by Confederates in Battery Wagner repulsed the attack by two Union brigades, inflicting a seven-to-one ratio of casualties on the attackers.

Gillmore and Dahlgren were compelled to settle down for a siege that encompassed Battery Gregg at the northern tip of Morris Island and Fort Sumter itself as well as Battery Wagner. Gillmore moved up his 100-pound and 200-pound Parrott rifles close enough to begin reducing Fort Sumter to rubble, while the ironclads and other warships continued to pulverize Batteries Wagner and Gregg. But heat exhaustion, disease, and expiring enlistments began to decimate Union naval crews. Welles promised to send more sailors from the North, but he also ordered Dahlgren “to enlist for service in the squadron as many able-bodied contrabands as you can. . . . There is a great demand at present from all quarters for seamen, and the contraband element must be used where it can with advantage.”10

Casualties and illness also devastated the Union army in South Carolina. Gillmore pleaded in vain with General in Chief Halleck for reinforcements. Concerned that the campaign might be discontinued if no additional troops were sent, Dahlgren wrote to Welles, who asked Gustavus Fox to see Halleck about the matter. The general in chief insisted that he had no troops to spare from other theaters. Welles went over his head to Lincoln, who ordered Halleck to send 10,000 men from the Army of the Potomac and from North Carolina.11

By August Dahlgren also was suffering from the enervating heat and humidity. “My debility increases,” he wrote in his diary on August 18, “so that to-day it is an exertion to sit in a chair. I feel like lying down. My head is light. How strange—no pain, but it feels like gliding away to death.”12

Rear Admiral John A. Dahlgren standing next to one of the guns named after him. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress)

However exhausted Union sailors were, their guns kept pounding away. From July to September, the New Ironsides alone fired 4,439 projectiles against Confederate defenses on Morris Island and Fort Sumter, and the monitors fired 3,577 more.13 The commander at Battery Wagner reported on September 5 that “a repetition of to-day’s fire will make the fort almost a ruin. . . . Is it desirable to sacrifice the garrison?” The next day, General Beauregard telegraphed Richmond: “Terrible bombardment of Wagner and Gregg for nearly thirty-six hours . . . nearly all guns disabled . . . Sumter being silenced. Evacuation of Morris Island becomes indispensable to save garrison; it will be attempted tonight.”14 That night the Confederates quietly pulled out, and Morris Island became Yankee territory.

This achievement effectively closed Charleston to blockade-runners by making it possible for Union ships to remain in the channels inside the bar. “The completeness with which four little monitors, supported by an ironclad frigate, have closed this port is well worth noting,” Dahlgren boasted to Welles in January 1864. “For several months not a vessel has passed in or out.”15

But the Confederate flag still flew over Fort Sumter. “Old Sumter has suffered fearfully and is now a wreck, utterly powerless for offensive purposes,” acknowledged a Charleston merchant, “but held by its garrison under orders from the General [Beauregard] with a tenacity and gallantry which is wonderful. . . . But even if it should be completely destroyed, the enemy are very far from getting the city. We have remaining an inner line of batteries, and Sullivan’s Island, from the Cove to the Moultrie House, is one continuous battery so that you can see their work has hardly commenced.”16

Dahlgren thought the same. He wanted to remove the obstructions and torpedoes from the vicinity of Fort Sumter so that his ironclads could move closer to attack Fort Johnson and other batteries defending the city. Sumter had been so badly battered that the Confederates had removed most of its big guns, but riflemen and field artillery in the fort could still impede efforts to take up the obstructions. So Dahlgren planned a surprise boat attack on Fort Sumter for the night of September 8–9 by 500 sailors and marines.

By coincidence, General Gillmore was planning a similar attack with two regiments the same night. Until this time, the cordial cooperation between Dahlgren and Gillmore had been a textbook example of combined operations. But on this night, the cooperation began to break down. When each commander learned of the other’s intention only hours before the planned attacks, Gillmore proposed that they coordinate their efforts under command of an army officer. Dahlgren replied rather haughtily: “I have assembled 500 men and I can not consent that the commander shall be other than a naval officer.” Gillmore replied, just as haughtily, that “why this should be so in assaulting a fortification, I can not see.” The two men finally agreed that each group should attack from a different direction under officers of their own service and arranged a password so they would not fire on each other.

In the event, the navy’s attack came first, while the army boats were delayed by low tide. The assault was a fiasco. Back in April, the Confederates had picked up the Keokuk’s signal book floating into shore after that vessel had sunk. The navy had not changed its code, so the Confederates were able to read the flag communications about the boat attack and were ready for it. When the first boats landed, the marines and sailors were immediately pinned down by rifle fire and hand grenades. Several were killed and wounded, and more than a hundred were captured. In the darkness, the attackers could scarcely see anything, while the defenders, who had been there for months, knew every inch of the ground. “I could see nothing but the utmost confusion,” reported a marine lieutenant who escaped. Some navy boats turned back, and when the officers commanding the army boats finally approached and saw what was happening, they called off their own attack.17

In the aftermath of this affair, relations between Gillmore and Dahlgren deteriorated. Even though the Confederates still occupied Fort Sumter, the admiral wanted to go ahead and clear an opening through the obstructions for his monitors. He asked Gillmore for army fire against the fort to keep its sharpshooters in their bombproofs. Gillmore did not think his guns could do the job, causing Dahlgren to complain (in his diary) that “having expended my means for sixty days in helping him to clear Morris Island, he demurs at the first step in help of me!”18

Dahlgren must have reflected ruefully on his eagerness to get this command and wondered if he should have heeded the old adage: “Be careful what you wish for; you might get it.” Plagued by continuing friction with the army, criticism from Northern newspapers because he had not yet “taken” Charleston, and sniping from what Welles called the Du Pont clique and other naval officers who still resented his promotion to rear admiral, Dahlgren was depressed by “wearing anxieties, with slander and base abuse . . . miserable lies which corrode the good name of a whole life.”19

But he had a squadron to command, a blockade to maintain, and a continuing campaign against Charleston to consider, so he could not indulge in self-pity for long. On the night of October 5, the Confederate navy finally answered Beauregard’s plea for an attack on one of the Union ironclads—the biggest one, the 3,486-ton New Ironsides. A cigar-shaped, semisubmersed vessel only fifty feet in length named David slipped almost invisibly through the dark waters, planted a 60-pound canister of powder against the Union Goliath’s starboard quarter, and blew a hole in it. Two of the David’s crew abandoned ship and were captured, but the other two got her back to Charleston and a heroes’ welcome. At first, the damage to the New Ironsides did not appear serious, but later inspection showed that it was more severe. She stayed in the squadron and was patched up well enough at Port Royal to remain on station until she returned to the North in June 1864 for extensive repairs.20 The David’s success spawned the construction of several other David-class torpedo boats in the South, one of which inflicted minor damage on the USS Minnesota at Hampton Roads in April 1864.

After the David’s attack on the New Ironsides, Dahlgren ordered all his ironclads inside the bar to fit outriggers and netting around each vessel when anchored and to row patrols around them from dark to dawn. But the Confederates were preparing an even more startling surprise for the blockade fleet at Charleston. Dahlgren learned from deserters of a torpedo vessel called the “American Diver,” developed in Mobile and shipped by rail to Charleston. It “is nearly submerged and can be entirely so,” Dahlgren reported to Welles in January 1864. “It is intended to go under the bottoms of vessels and there operate.” Dahlgren’s sources were remarkably well-informed, even to the extent of telling him that in trials, this submarine “has drowned three crews, one at Mobile and two here, 17 men in all.”21

Modern historians are not certain about whether there was a drowning in Mobile. But there were indeed two at Charleston, not involving the American Diver but its successor, the H. L. Hunley, which was actually the vessel brought to Charleston. One of these accidents took the life of the inventor Horace L. Hunley, after whom the submarine was named. The Hunley was a notable combination of the old and new. It was powered by a propeller turned with hand cranks and equipped with diving fins and water tanks for ballast. Like the David, it carried a torpedo on a bow spar to be exploded against a ship’s hull. On the night of February 17, 1864, a nine-man crew took the Hunley outside the bar, where blockade ships had not taken protective precautions, and sank the ten-gun wooden screw sloop USS Housatonic. The Hunley never returned from this mission, and its crew achieved status as martyr-heroes in the South. With this first combat action by a submarine, the Hunley became the most famous warship of the Civil War next to the Monitor—in part because, like the Monitor, its position was later discovered and much of it has been raised. The Hunley can be seen today in Charleston.22

After the sinking of the Housatonic, Dahlgren ordered ships outside the bar to remain under way at night, or if anchored to put out netting on outriggers and row patrols.23 The successful attacks on the New Ironsides and Housatonic raised Confederate morale and dampened Union spirits. They may have contributed to a decision to forgo any more major naval efforts to capture Charleston. On October 18, 1863, Dahlgren had told Fox that “the public demand for instantly proceeding into Charleston is so persistent that I would rather go in at all risks than stand the incessant abuse lavished on me.” But four days later, the admiral called a rare council of war with his eight ironclad captains and two staff officers. For six hours, they discussed whether to break the obstructions and fight their way to Charleston once the repairs on the monitors were completed or wait until new ironclads promised for sometime in the winter became available. They voted six to four to wait.24 Welles told Dahlgren that with the virtual cessation of blockade-running into Charleston, the capture of the city would be merely symbolic and not worth the cost. “While there is an intense feeling pervading the country in regard to the fate of Charleston,” Welles acknowledged, “the Department is disinclined to have its only ironclad squadron incur extreme risks when the substantial advantages have already been gained.”25

Gillmore and many of his troops were transferred to Virginia in the spring of 1864 to become part of the Army of the James to assist the Army of the Potomac in the big push against Richmond. Dahlgren was no doubt relieved to see Gillmore go, but the departure of troops made a combined operation against Charleston that year even less likely. Fox had also become “averse to any attack on Charleston,” Dahlgren learned in March. “He suggests letting Farragut have the new monitors for Mobile,” which was now a navy priority.26

One reason for the Navy Department’s reluctance to renew the effort to capture Charleston was the danger from the Confederacy’s increasing numbers and effectiveness of torpedoes. Northern naval officers had ambivalent attitudes toward these “infernal machines.” In February 1863 Du Pont had denounced Confederate use of them and refused to consider fighting fire with fire—that is, using them himself against the enemy. “Nothing could induce me to allow a single one in the squadron for the destruction of human life,” he fumed. “I think that Indian scalping, or any other barbarism, is no worse.”27 The commander of Union ships on the St. Johns River in Florida, where several vessels had been sunk or damaged by mines, warned that he would “deal summarily with anybody caught putting down torpedoes in the river.” Dahlgren threatened to hang the two captured crew members of the David after they had torpedoed the New Ironsides “for using an engine of war not recognized by civilized nations.”28

Needless to say, Dahlgren never did so. By 1864 some Union commanders were using torpedoes themselves, especially in the James River to discourage Confederate ironclads at Richmond from making a sortie against Union transports and gunboats in the river. Dahlgren even advised the Navy Department “to block the Confederates with their own game and let loose on them quantities of torpedoes.” He rigged up a torpedo raft loaded with several hundred pounds of gunpowder to float up to Fort Sumter and blow out the outer wall. It did not work.29 In any case, by 1864 naval mines had become a feared but legitimate weapon of war in the eyes of most Union officers.

THE CLOSURE OF CHARLESTON to blockade-runners forced most of them to use Wilmington, which now became the busiest Confederate port. Acting Rear Admiral Samuel Phillips Lee’s North Atlantic Squadron captured or destroyed fifty runners in 1863 and fifty-four in the first nine months of 1864, most of them going to or from Wilmington.30 But of course a larger number got through. Some of those, however, did not have the full cargo with which they had left port. Many of them had piled their decks as well as holds with as much cargo as the vessel would bear. When spotted and chased, they would jettison the deck cargo (usually cotton bales outbound, lead and munitions inbound) to gain speed in order to get away. Many of these runners were extremely fast, having been built especially for the purpose, and when lightened of part of their load, they could usually outrun a blockader—whose crew could console themselves by picking up the floating bales worth up to $200 each. More than one Northern skipper was accused of breaking off pursuit to pick up bales to win the prize money before another ship could get them.

By the fall of 1863, Phillips Lee finally had enough ships to tighten the Wilmington blockade at both entrances to the Cape Fear River. Experience had refined his tactics. At each inlet, he posed small shallow-draft vessels as close to the bar as possible to detect runners going out. When they did, the picket ship fired a gun and a rocket to alert larger and faster vessels patrolling a couple of miles out and to indicate the direction the runner was heading. Farther out still, sometimes fifty miles or even more toward Bermuda or the Bahamas, was another cordon of blockade ships that intersected the expected routes of outbound runners at a time and place calculated by a complicated formula that combined the times of the beginning of the ebb tide and the rising or setting of the moon (if there was one) with the distance to be traveled and the estimated speed of the runners. For inbound runners, the time of moonrise or -set and of the flood tide could also help blockaders guess when and where runners might appear.

The captain’s clerk of the USS Florida (not to be confused with the Confederate raider of the same name) described his ship’s capture of the valuable blockade-runner Calypso carrying armor plates for ironclads when the Florida was patrolling the offshore route from Nassau. After an exciting chase of several hours, the Florida finally caught the Calypso. “Here was our chance at last to show what we are worthy of,” he wrote in his diary. “The welcome relief from a monotony of months, that had nearly driven the men crazy, had come at last. There was a chance now to refute the calumnies with which the press, at home, branded the inefficiency of the Wilmington blockade”—and, he might have added, a chance at some welcome prize money.31

The captains of blockade-runners were quick learners; they changed direction or speed and began carrying rockets of the same type as the navy, which they fired in the opposite direction they intended to go. In this cat-and-mouse game, the runners continued to have the advantage, especially on dark, foggy, and tempestuous nights, but the blockade did continue to tighten. In the fall of 1863 the British agent for a cotton importer informed London that five out of seven runners carrying cotton from Wilmington had been recently captured. There was no cotton in Bermuda, so “you may not expect to receive over 300 Bales in the next three months” and “the European markets must advance to higher rates than ever yet known.”32 The wife of the Confederate agent in Bermuda was depressed by these captures, which included two of the fastest runners, the R. E. Lee and the Margaret and Jessie. “We can ill afford to lose any more,” she wrote in November 1863. But three weeks later, Union ships captured two more runners. “What a list of trophies for those mercenary hirelings,” she mourned.33 The Union navy added insult to injury by converting the R. E. Lee and the Margaret and Jessie into blockaders and renaming them the USS Fort Donelson and the USS Gettysburg.

The Confederate publicist in England, Henry Hotze, inadvertently testified to the effectiveness of the blockade. Editor of the Index, a pro-Confederate newspaper in London, Hotze wrote many articles claiming the illegality of the “paper blockade.” But in a letter to Confederate Secretary of State Judah Benjamin in January 1864, he complained that “at the present rate of exportation through the blockade . . . it would take 20 years to export the cotton now in the Confederate states.”34

Nevertheless, with every report of ships getting through the blockade, critics in the North upbraided Welles. The harassed navy secretary in turn reproved his squadron commanders—especially Lee, because Wilmington was his responsibility. “Five steamers containing 6,300 bales of cotton have arrived within one week at Bermuda,” he told Lee in July 1864. “It is of great importance that a careful examination of the blockade should be made by yourself, and such arrangements devised as will insure greater vigilance.”35 Lee’s blockade fleet had been thinned out during the past two months because so many of his ships were in the James River supporting the army’s operations against Richmond and Petersburg.

Next to munitions and shoes, one of the most important products that the Confederacy tried to import through the blockade was salt. This seemingly humble item was necessary for the curing and preservation of meat in that prerefrigeration era and for preserving hides during leather manufacture. Despite ample domestic sources of salt, the South had imported most of what it needed in the antebellum era from the North or abroad. Early in the war, some of the largest potential salt deposits in the Upper South were occupied by Union troops. Many of the blockade-runners captured early in the war, especially sailing ships, were carrying salt.

To compensate for these losses, the Confederacy established salt-making works to boil and evaporate seawater along the coast from North Carolina to Texas, especially on Florida’s Gulf coast. These works were usually located a few miles up tidal estuaries or rivers too shallow for Union gunboats to raid. But Northern sailors and marines learned to carry out raids up these rivers in cutters and launches armed with boat howitzers that were useful not only for driving away workers and guards but also for blowing holes in boilers and pans used for evaporating the briny water.

The navy raided hundreds of saltworks. In one ten-day period in December 1863, boats from the bark USS Restless destroyed 290 saltworks in St. Andrew’s Bay, Florida, including 529 boiling kettles averaging 150 gallons each and 105 boilers of much larger capacity—not to mention 4,000 bushels of salt. Not to be outdone, boats from the steam gunboat USS Tahoma went up the St. Marks River in Florida two months later and destroyed 8,000 bushels of salt along with kettles and boilers with the capacity to make 2,500 bushels per day.36 Such raids helped drive the price of salt in the Confederacy to unimaginable heights and exacerbated the inflation that almost wrecked the Confederate economy. They also broke up the monotony of blockade duty and raised sailors’ morale by demonstrating that they could go on the offensive and take the war to the enemy on the beach.37

SAMUEL PHILLIPS LEE thought that the large number of gunboats he had to keep in the North Carolina sounds to support the army’s occupation of several coastal towns was a wasteful diversion of resources. He may have been right, but Confederate leaders considered these forces a potential threat to the interior of North Carolina and its communications with Virginia. In 1864 they laid plans to use the ironclad they had been building up the Roanoke River to help drive the Federals out of Plymouth as the first step toward regaining the sounds.38

The senior Union naval officer at Plymouth, Lieutenant Commander Charles W. Flusser, had good intelligence about Confederate progress in completion of the CSS Albemarle. A smaller version of the Arkansas, the Albemarle was armed with only two guns, but both were 6.4-inch Brooke rifles. In a rare (for the Confederates) combined operation, the Albemarle came down the Roanoke on April 19 to cooperate with three brigades of Confederate infantry in an attack on the single brigade of Union soldiers garrisoning Plymouth. With his two sidewheel double-enders (rudders on both ends so the vessels could operate in narrow streams without having to turn around), the USS Miami and the USS Southfield, Flusser prepared to fight the Albemarle. He chained his ships together to try to trap the Albemarle between them. But the ironclad rammed the Southfield and tore a huge hole in her side. As the Southfield was sinking, Flusser on the Miami personally fired the bow gun point blank at the Albemarle. It was loaded with a shell intended for use against Confederate infantry instead of a solid ball; the shell exploded against the Albemarle and shrapnel rebounded straight back and killed Flusser, one of the navy’s most promising young officers.39

A seventeen-year-old surgeon’s steward on the Miami described the uneven battle with the Albemarle. “We fired about thirty shells at the ram but they had no effect on her,” while her shots in return caused havoc on the Miami. “As fast as the men were wounded, they were passed down to us and we laid them one at a time on the table . . . and extracted the balls and pieces of shell from them. . . . Dr. Mann and I looked like butchers . . . our shirt sleeves rolled up and we covered with blood. . . . The blood was over the soles of my boots. . . . When Captain Flusser fell, the men seemed to lose all heart, and we ran away from the ram into the sound.”40 Deprived of naval support, the Union commander of the Plymouth garrison surrendered his surviving force the next day.

This victory encouraged Confederates to plan a similar combined attack on New Bern.41 But Phillips Lee organized a task force of Union ships to swarm around the Albemarle if she emerged into the sound, fire into her smokestack and gunports, ram her, and do whatever it took to disable her no matter what the cost to the attackers. On May 5 the Albemarle ventured into her namesake sound. Six Union gunboats carried out the swarming tactics. They hit the ironclad with at least sixty-four shots, one of which dismounted a gun while others riddled the smokestack so that her fires would scarcely draw, forcing her to limp back to Plymouth.42

Her retreat ended the plan for a combined attack on New Bern. The Albemarle did not venture into the sound again. But her presence at Plymouth constituted a continuing threat that tied down a number of Union vessels that might otherwise have been on blockade duty. In July 1864 the former commander of the CSS Florida, Captain John N. Maffitt, was assigned command of the Albemarle. Rumors soon circulated that the intrepid Maffitt intended to take her out and challenge the Union gunboats again. But the army commander of the North Carolina district that included Plymouth was alarmed by this possibility. “There is great danger of her capture if she goes out into the sound,” he warned, which “would be irreparable and productive of ruin to the interests of the Government, particularly in this State and district.”43 Maffitt soon took command of a government blockade-runner and the Albemarle stayed at Plymouth.

She remained a thorn in Acting Rear Admiral Lee’s side, however, and he came up with a plan for “a torpedo attack, either by means of the india-rubber boat . . . or a light-draft, rifle-proof, swift steam barge, fitted with a torpedo.”44 Lee had in mind just the man for this job: twenty-one-year-old Lieutenant William Barker Cushing, who had proved his worth as a sea commando in several daring raids behind Confederate lines in the Cape Fear River. In August 1863 Cushing had led a cutting-out expedition at New Topsail Inlet that captured a schooner and destroyed extensive saltworks. In February 1864 he led a raid by small boats past Fort Caswell to capture a Confederate general. The general had gone up to Wilmington that day, but the Yankees captured the chief engineer of the Confederate garrison and brought him away. Then in June 1864 Cushing took a cutter up the Cape Fear almost to Wilmington itself in a scouting mission that lasted four days and gained valuable information about Confederate defenses. He outwitted several boats sent to capture him and escaped without harm to his party.45

Cushing enthusiastically embraced Lee’s idea of a torpedo attack on the Albemarle. He went to New York to supervise the construction of a special steam launch for the purpose. On the night of October 27, he led fifteen men up the Roanoke River to Plymouth, passing Confederate pickets without detection. They approached the Albemarle, which was tied to a wharf and surrounded by a boom of logs. Circling around, they were detected, and Cushing made straight for the Albemarle through a hail of bullets, bounced up over the logs, planted his torpedo on the hull, and exploded it at the same instant that one of the Albemarle’s guns shot a hole in the launch that sank it. Cushing and his men jumped into the river and swam for it. “The most of our party were captured,” he wrote in his official report, “some were drowned, and only one escaped besides myself, and he in another direction. . . . Completely exhausted, I managed to reach the shore. . . . While hiding a few feet from the path, two of the Albemarle’s officers passed, and I judged from their conversation that the ship was destroyed.”46

Cushing made his way back to the fleet, where he was hailed as a hero. He received the Thanks of Congress and was promoted to lieutenant commander. Eight Union gunboats steamed up the Roanoke River and recaptured Plymouth, which remained in Union hands for the rest of the war. Despite the derring-do in North Carolina waters during 1864, however, this theater remained marginal to the crucial course of events elsewhere in that year.