Chapter Ten

From the Red River to Cherbourg

From the fall of Forts Henry and Donelson in February 1862 to the fall of Vicksburg and Port Hudson in July 1863, the Mississippi River and its tributaries were one of the most active theaters of the war. And this vast region was anything but tranquil and routine thereafter. Rear Admiral David Dixon Porter’s Mississippi Squadron remained responsible for suppressing guerrillas, monitoring trade, convoying supplies to General William S. Rosecrans’s Army of the Cumberland, carrying out combined operations with General Nathaniel P. Banks’s Army of the Gulf on the Red River in the spring of 1864, and a host of other activities necessary to maintain Union control of the Mississippi valley and help repel Confederate counteroffensives.

In the fall of 1863, Porter established several “divisions” of his squadron on the Mississippi River from Cairo to New Orleans. Each division had several gunboats, and each of these vessels was responsible for patrolling a section of the river ten or twelve miles in both directions from its station to suppress guerrillas and prevent the enemy from crossing men and supplies. “The protection of the river since the fall of Vicksburg has been left entirely to the navy,” wrote Porter, “the army only occupying a few prominent points on the Mississippi, making no expeditions away from those points.”1

The guerrillas operated in bands of 20 to 100 men, often with one or two pieces of field artillery. An acting master’s mate commanding a tinclad on the lower Mississippi described a typical encounter with a band that possessed artillery near Gaines’ Landing, Arkansas. “As soon as I discovered what they were, I ran down to the gun deck to beat to quarters,” he recounted. “Imagine the confusion and delay possible, when half of the men and the Drummer boy were out of their hammocks. . . . But with all this confusion, I had the Port battery manned and gave them one broadside before the thieves had given us their second round.” A furious duel ensued, and the boat was hit several times, but “we drove them off firing the last shot.”2

Guerrillas were not the only enemy that gunboat crews had to confront. “You have no conception of what mosquitoes are down here,” wrote a sailor on the tinclad USS Silver Cloud patrolling between Fort Pillow and Helena. “They are perfect devils. . . . I’m also favored with a large company of cockroaches. . . . They devour all the provisions I buy. They eat my thread, clothes & paper & I think they tried to devour my needles. . . . I have become so used to them that I can go to sleep while they are performing pedestrian tours up my legs and over my body generally.”3

One problem with using gunboats against guerrillas was the ability of these mounted men to move out of range and reappear along the banks of rivers somewhere else. The Marine Brigade created out of the ram fleet by Alfred Ellet thus became one of the Mississippi Squadron’s main antiguerrilla outfits. With seven gunboats carrying several hundred cavalry and infantry, they could land horses and men to chase guerrillas into the interior. But even this technique often failed to catch the swift rebels, who knew every byway in the region. The Marine Brigade therefore decided to carry out proactive patrols. They captured some mules to mount their infantry, and in September 1863 they tried the new tactics of landing cavalry and mule-mounted infantry to sweep through the interior, stopping at plantations suspected of harboring guerrillas. While the main body surrounded one plantation, an advance company moved on to the next, and the group thus leapfrogged across country “so rapidly that we kept ahead of the reports of our presence in that section,” explained an officer, “thus securing any persons who were loitering around these plantations waiting to concentrate at some given point on the river to fire upon passing transports.” Having secured several prisoners, the brigade returned to their gunboats at a prearranged point.4

As time went on, however, discipline in the Marine Brigade became more lax. Operating away from both army and navy control, they sometimes plundered the houses and farms they raided, regardless of whether they found any guerrillas there or not. Horses, men, and the gunboats of the brigade began to break down. The warfare against bands that seemed to disappear from one place and pop up again somewhere else became exhausting. In June 1864 an officer in the brigade described “daily sharp, short skirmishes with the roving bands of guerrillas, varied with the roving bands of those almost intangible enemies, the flies by day and mosquitoes by night,” the “malarial water we are compelled to drink, and the excessive hot weather.” By August 1864 the Marine Brigade had outlived its usefulness and was disbanded.5

The navy learned that the best way to deal with guerrilla attacks on supply transports was a convoy system. A large number of transports would gather at a supply depot such as Cairo, Illinois. Several gunboats would space themselves through the fleet and convoy them to their destination. In the winter and spring of 1862–63, cavalry raids by Generals Nathan Bedford Forrest and Joseph Wheeler cut rail and road routes to Union General William S. Rosecrans’s army at Murfreesboro. Rosecrans was dependent on supplies that came up the Cumberland River to Nashville in weekly convoys of thirty or more steamboats guarded by four to six gunboats on each trip. “Our line of convoy up the Cumberland is sometimes 4 or 5 miles in length,” wrote the navy officer in charge in February 1863. “All of Rosecrans’ supplies are sent up that way.” From January to June 1863 the gunboats convoyed four hundred transports and 150 barges to Rosecrans “without loss of a single steamer or barge.” These convoys enabled the general to build up the huge depot of supplies that supported his Tullahoma and Chattanooga Campaigns.6

Forrest’s and Wheeler’s cavalry made a major effort to stop this supply pipeline by attacking the Union garrison at Fort Donelson on February 3, 1863. The Confederates outnumbered the 800 Union defenders five to one. The Northern soldiers held out all day until they were almost out of ammunition. A convoy was approaching Fort Donelson with six gunboats, which raced upriver when they received news of the attack. Arriving at about 8:00 P.M., they found the Confederates deploying dismounted for a final attack in bright moonlight. The Confederate left wing was positioned in a ravine leading to the river. “This position gave us a chance to rake nearly the entire length of his line,” wrote the senior officer of the gunboat flotilla. “Simultaneously the gunboats opened fire up this ravine, into the graveyard, and into the valley beyond, where the enemy had his horses hitched. . . . The rebels were so much taken by surprise that they did not even fire a gun, but immediately commenced retreating.”7

Convoys also supplied General Ambrose E. Burnside’s operations in East Tennessee during the fall of 1863, when the Cumberland River rose enough to get them to the junction of the Cumberland and the Big South Fork River above Nashville. When Grant took control of Union forces besieged in Chattanooga after the battle of Chickamauga, he ordered Sherman to bring four divisions from Vicksburg to Chattanooga. Porter mobilized a flotilla of gunboats to convoy the troops and transports as far as Eastport, Mississippi, from which Sherman had to depend on rail communications the rest of the way. “We are much obliged to the Tennessee, which has favored us most opportunely,” wrote Sherman to Porter as he prepared to move overland after debarking at Eastport. “I am never easy with a railroad which takes a whole army to guard, each foot of rail being essential to the whole; whereas they can’t stop the Tennessee, and each boat can make its own game.”8 Four gunboats convoying transports up the White River to De Vall’s Bluff in Arkansas also supported the campaign of Major General Frederick Steele that captured Little Rock in September 1863.9

One of the more spectacular feats of the Mississippi Squadron was performed by six tinclads of the Ohio River Division during General John Hunt Morgan’s raid north of that river in July 1863. After Morgan’s 2,000 cavalry crossed into Indiana, Lieutenant Commander Le Roy Fitch concentrated his gunboats and moved upriver parallel to the raiders, “keeping boats both ahead and in his rear, guarding all accessible fords.” As pursuing Union cavalry closed in at Buffington Island, Morgan tried to cross there but the tinclads “shelled most of them back, killing and drowning a good many.” Most of the raiders were captured there; Morgan and 350 men kept on and were eventually run down and captured near Salineville, Ohio. One of the army officers in charge of the pursuit declared that the “activity and energy with which the squadron was used to prevent the enemy recrossing the Ohio, and to assist in his capture, was worthy of the highest praise.”10

In the spring of 1864, General Nathan Bedford Forrest led a raid into West Tennessee and Kentucky. In Paducah, Kentucky, at the junction of the Tennessee and Ohio Rivers, his 2,700 men attacked 800 Union defenders, driving them back into Fort Anderson. Two tinclads swept the streets of the town, firing 700 rounds that finally drove Forrest’s raiders away. “We kept putting the shell and grape into them from all the guns we could get to bear,” wrote a gunner on the USS Peosta. “Their riflemen and some of the people of the town got into the buildings down by the river and pelted us with musket balls but we soon gave them enough of that for we directed our whole fire on them at short range with shell grape and canister and soon fetched the bricks around their eyes. . . . They would have had the fort and the city if it had not been for us, for they were out of ammunition in the fort.”11

Almost three weeks later, however, the sole gunboat on the scene when Forrest attacked Fort Pillow on the Mississippi, the USS New Era, could do little to help the defenders. The New Era drove off the attackers on the south side of the fort, but dense timber protected them on the north side. When the Confederates carried the fort, murdering many of the black soldiers and white Tennessee Unionists after they surrendered, the captors turned the fort’s artillery on the lightly armored tinclad and drove it out of range.12

In addition to countering guerrillas and raiders and convoying supply transports, one of the most important tasks of the Mississippi Squadron was regulating Northern trade with occupied territory. Porter conceived of this duty as analogous to the blockade against trade in contraband goods, imposed on the rivers instead of on the high seas. But to foster the reopening of commerce in occupied Southern territory, the Treasury Department issued trade licenses to Northern merchants to purchase cotton from and sell goods to Southerners who took an oath of allegiance to the United States. Much trade in contraband goods under fraudulent licenses went on from such cities as Memphis and Helena, however, and these items found their way into Confederate possession. “I have reason to know that the Board of Trade in Memphis has granted licenses to carry contraband goods into rebel places,” wrote Porter on one occasion. “I have directed the officers under my command not to recognize any permits from any board of trade. . . . I claim to have jurisdiction on the water, and I intend that all rebel depots shall be hermetically sealed.”13

Such actions brought Porter into conflict with the Treasury Department, and he was forced to recognize legitimate trade permits. Yet there were many gray areas where the navy continued to seize shipments that officers suspected were intended for the enemy and confiscated cotton that was traded for such goods. “Can we not stop this cotton mania?” Porter asked Grant in February 1863. “I have given all the naval vessels in the river strict orders to permit no trade in rebel territory, but to seize all rebel cotton for the Government.”14

Just as blockade ships on blue water captured runners carrying cotton, Porter’s squadron therefore laid hold of cotton shipments on the rivers and even sent men ashore to take cotton from plantations and transport it north as prizes. The district court at Springfield, Illinois, however, ruled that most of this cotton was owned by individuals who claimed to be Unionists and who had Treasury Department permits to ship it. Porter asserted in 1864 that of the 8,000 bales his squadron had seized, the court recognized only 1,000 as prizes. “The trickery and corruption practiced is beyond conception,” Porter fumed. “The claims put in by the Treasury Department are preposterous. . . . The court at Springfield is admitting claimants to plead when cotton is actually marked C.S.A.”15

Porter’s motives were not entirely patriotic. If ruled a prize, half of the proceeds from sale of the cotton would have gone to the naval pension fund and 45 percent to the members of the crew that had seized it, with 5 percent going to Porter himself as squadron commander. That percentage of the proceeds from 7,000 bales would have been a tidy sum. And there is evidence that some of the cotton seized from plantations was indiscriminately stamped “C.S.A.” by its captors. That was particularly true of cotton sent north from the Red River Campaign in the spring of 1864, which turned out to be a fiasco for the Union army and nearly a calamity for Porter’s squadron.

SEVERAL POLITICAL AND STRATEGIC purposes impelled the invasion of northern Louisiana via the Red River by General Banks’s Army of the Gulf and Porter’s Mississippi Squadron. Banks was overseeing the creation of a Unionist government in the state under Lincoln’s 10 percent Reconstruction plan; to gain control of more of Louisiana would give that process greater legitimacy. The continuing concern about French actions in Mexico caused the Lincoln administration to recommend a greater military presence in Texas, which could be achieved by continuing the movement up the Red River into that state. General Grant wanted Banks’s army to capture Mobile instead, as he had been advising since the previous summer. If it were purely a matter of military strategy, General Halleck informed Grant, a thrust against Mobile would make more sense. But as “a matter of political or State policy, connected with our foreign relations,” the president still considered it important to “occupy and hold at least a portion of Texas” in addition to Brownsville.16 Admiral Porter and General Sherman were concerned about the reported construction of Confederate ironclads and other gunboats at Shreveport that might threaten Union control of the Mississippi where the Red River entered the big river. Taking advantage of the spring rise in the Red to go above the rapids at Alexandria, they proposed to “clear out Red River as high as Shreveport by April.” To do the job thoroughly, Porter intended “to take along every ironclad vessel in the fleet.”17 And then there was all that cotton reported to be waiting along the banks of the Red River to feed the New England mills and enrich the sailors and soldiers who seized it as a prize.

Porter did indeed take almost every ironclad in his squadron into the Red River in March 1864—thirteen of them, plus another thirteen tinclads and various tugs, tenders, dispatch boats, and supply vessels. This muscle-bound fleet was far larger than needed for the purpose, especially given the difficult navigation on the upper stretches of the river and the lesser spring rise than usual. Why Porter brought so many vessels is not clear, but it may have had something to do with the large amount of cotton they gathered—some 3,000 bales.

The campaign started well. The gunboats and a division of soldiers drove the Confederates out of Fort De Russy thirty miles up the river on March 14. “The surrender of the forts at Point De Russy is of much more importance than I at first supposed,” Porter reported to Welles. “The rebels had depended on that point to stop any advance of the army or navy into this part of rebeldom.”18

That was about the last good news from the expedition, however. While the gunboats worked their way upriver to within thirty miles of Shreveport, the army moved inland and ran into the Confederates under Major General Richard Taylor at Mansfield on April 8. Taylor defeated Banks and drove the Federals back to Pleasant Hill, where another battle took place on April 9. This one was a tactical Union victory, but Banks decided to give up the campaign anyway and retreat to Alexandria.

When word of this retreat reached Porter, he too decided to return downriver, especially since the water level was dropping rapidly and threatening to strand several of his vessels. “The army has been shamefully beaten by the rebels,” Porter informed his friend General Sherman. “I was averse to coming up with the fleet [this was untrue], but General Banks considered it necessary . . . and now I can’t get back again, the water has fallen so much. . . . I can not express to you my entire disappointment with this department.”19

The gunboats continually went aground and were pulled off on the way down. Confederate artillery and cavalry began appearing on the riverbank and shelling the fleet. At Blair’s Landing, a full-scale battle took place between 2,000 troops and three gunboats—two of them aground. In the turreted ironclad USS Osage, Lieutenant Commander Thomas O. Selfridge made the first known use of a periscope to aim his 11-inch guns. One of his

The Red River Campaign, March–May 1864

shots killed the commander of the Confederate troops, which caused them to break off and disappear inland.20

On April 15 the largest of Porter’s ironclads, the USS Eastport, struck a torpedo, and her captain ran her aground to be repaired. They finally got her afloat, but she grounded eight more times on the way down to Alexandria, where she went aground again at the rapids—for the last time. It proved impossible to get her off, so on April 26 her captain lit a match to a fuse leading to 3,000 pounds of gunpowder and blew her up. During the attempt to get her off, Confederates had attacked her consorts and two pump boats, putting both out of action and sending a shot through the boiler of one that scalded to death a hundred contrabands on board who were being carried to freedom.

A substantial part of Porter’s fleet was stranded at the rapids above Alexandria when the river dropped too low for them to get through. Porter was profoundly depressed by the career-ending prospect of having to blow them up to prevent capture. “It can not be possible that the country would be willing to have eight ironclads, three or four other gunboats, and many transports sacrificed without an effort to save them. It would be the worst thing to happen in this war.”21

One of Porter’s officers suggested the possibility of building a coffer dam at the falls to raise the water enough to float the vessels through the chute. But it was an army officer, Lieutenant Colonel Joseph Bailey of Wisconsin, who organized the actual construction of the dam. An engineer with experience in building dams to float logs downstream in Wisconsin, he put several thousand soldiers to work on the project at the lower falls. Two barges anchored to extend the dam to midstream broke loose, but four of the gunboats got through while the water was still high. Porter described the scene as the first of them, the timberclad USS Lexington, entered the chute. She “steered directly for the opening in the dam,” he wrote, “through which the water was rushing so furiously that it seemed as if nothing but destruction awaited her. Thousands of beating hearts looked on anxious for the result; the silence was so great as the Lexington approached the dam that a pin might almost be heard to fall.” She entered the chute “with a full head of steam on, pitched down the roaring torrent, made two or three spasmodic rolls, hung for a moment on the rocks below, was then swept into deep water by the current and rounded to, safely, into the bank. Thirty thousand voices rose in one deafening roar.”

Three more gunboats got over before the water level dropped. Undaunted, Bailey and the soldiers built two new wing dams at the upper falls, and on May 11 and 12 the rest of the squadron made it through the rapids. “Words are inadequate to express the admiration I feel” for Bailey, remarked Porter with great relief. “This is without doubt the best engineering feat ever performed.”22 Bailey earned the Thanks of Congress and eventual promotion to brigadier general.

One of Porter’s gunboats going through the chute created by Colonel Joseph Bailey’s dam at Alexandria, Louisiana. (From Frank Leslie’s Illustrated History of the Civil War)

While these adventures were taking place, two tinclads escorting two troop transports downriver ran into a Confederate ambush several miles above Fort De Russy. Both transports were sunk and, after a firefight of several hours, the same fate befell the tinclads. Most of the soldiers on the transports escaped and were picked up by a third tinclad, the USS Forest Rose, after it too ran the gauntlet of Confederate field guns and riflemen. “A shell from the enemy’s gun struck us in the port side amidships and just under the waterline,” reported the executive officer of the Forest Rose. “I ran down and had just reached the port gun, aft the boilers, when another shell struck us on the casemate just over the gun and burst, driving a hole through the casemate and sending splinters in every direction.” The Forest Rose stayed afloat but broke off the fight and continued down with 300 soldiers and sailors who had escaped from the other vessels.23

Both the Union army and navy finally got out of the Red River without further serious mishap. The campaign reflected no credit on either. As Sherman put it after reading the reports from Porter, who blamed Banks for mismanaging everything, it was “one damn blunder from beginning to end.”24 Banks lost his field command of the Army of the Gulf, though he retained theater command. Porter’s mistakes were less egregious, and the near miracle of saving his fleet at Alexandria imparted a positive glow. Porter kept his command and even went on to greater things in the war’s final months, but the Red River Campaign left something of a stain on his reputation.

THE JAMES RIVER also became an active theater of operations again in 1864. After the withdrawal of the Army of the Potomac from the Virginia peninsula in August 1862, the James was a relatively quiet sector as the main action moved to northern Virginia and Maryland. For a time in the spring of 1863, however, actions along the Nansemond River, which flowed into the James from the south about fifteen miles west of Norfolk, had seemed to portend major fighting in this theater. Reports that Union troops planned an advance on Petersburg from their base at Suffolk on the Nansemond alarmed General Robert E. Lee. He sent General James Longstreet with two divisions to the south side of the James to counter this anticipated thrust.

When no movement by Union forces materialized, Longstreet converted his operations into a foraging expedition to obtain provisions for the Army of Northern Virginia from this region as yet lightly touched by the war. With 20,000 men, Longstreet also contemplated an attack on Suffolk. Detecting Confederate movements to the Nansemond, Federal commanders feared an effort to recapture Norfolk itself. “If Suffolk falls,” Acting Rear Admiral Samuel Phillips Lee warned Welles on April 14, “Norfolk follows.”25

To help the army defend Suffolk, Phillips Lee sent a half dozen shallow-draft gunboats—converted ferryboats and tugs—into the narrow, crooked river. These fragile craft became the Union’s first line of defense, doing more fighting and suffering more damage in artillery duels with Longstreet’s guns than did the Union soldiers. In one brilliant operation led by navy Lieutenant Roswell H. Lamson on April 19, a gunboat landed troops plus boat howitzers manned by sailors and captured five field guns and 130 prisoners. The loss of this battery was “a serious disaster,” Longstreet reported. “The enemy succeeded in making a complete surprise.”26 Two weeks later, after the battle of Chancellorsville, his divisions were recalled to the Army of Northern Virginia on the Rappahannock. The James River lapsed into quiescence again.27

But with the opening of Grant’s Overland Campaign in May 1864, the James became a key focal point of Union operations. For political reasons, President Lincoln had felt it necessary to give General Benjamin Butler another command after his removal from New Orleans. In November 1863 Butler became head of the Department of Virginia and North Carolina, the army counterpart of the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron. Butler formed the Army of the James in April 1864. Grant gave him the assignment of moving up that river against Richmond, while the Army of the Potomac began its campaign against General Robert E. Lee across the Rapidan River. Phillips Lee’s gunboats on the James would have a crucial role in this effort.

On May 5, 1864, Butler’s 30,000-strong army boarded transports and steamed up the James River to a landing at City Point nine miles from Petersburg. Convoyed by five ironclads and seventeen other gunboats, several of which dragged for torpedoes, the meticulously planned movement went off without a hitch. The next day, however, a 2,000-pound torpedo blew the USS Commodore Jones into splinters with the loss of forty men killed. And on the following day, the USS Shawsheen, dragging for torpedoes near Chaffin’s Bluff far up the river, was disabled by a shot through her boiler and captured along with most of her crew.28

Confederates had planted hundreds of torpedoes in the river and had prepared torpedo boats to attack Lee’s ships. Lee decided to create what amounted to a minesweeping fleet of three gunboats, which he named the “Torpedo and Picket Division.” He put Lieutenant Lamson in charge of this division. Lamson had been assigned to command of the USS Gettysburg, a captured blockade-runner converted into the fastest blockading ship in the squadron. Lee asked Lamson to give up this plum assignment, at least temporarily, to take up minesweeping duty.29

Lamson threw himself into this dangerous task and in his first day fished up and disarmed ten torpedoes, one of them containing almost a ton of gunpowder.30 Within three weeks his minesweeping fleet had expanded to eight gunboats, ten armed launches, and 400 men. Lamson explained how he turned the Confederates’ weapons against them. “I have had some of the large torpedoes we seized on our way up refitted and put down in the channel above the fleet” as protection from Confederate ironclads at Richmond if they came down. “I have [also] made some torpedoes out of the best materials at hand here, and have each one of my vessels armed with one containing 120 pounds of powder. . . . The Admiral expressed himself very much pleased with them and is having some made for the other vessels.”31

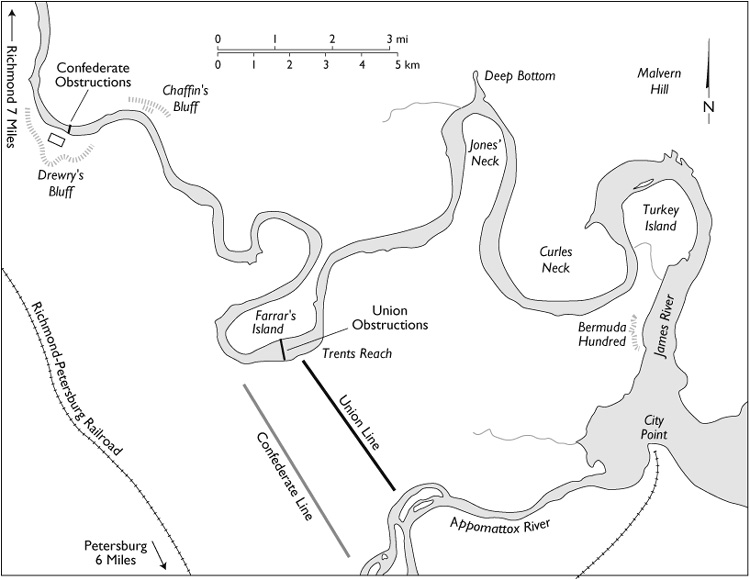

Butler had advanced up the James as far as Drewry’s Bluff only eight miles from Richmond. But the Confederates under General Beauregard attacked and drove him back to the neck of land between the James and Appomattox Rivers. Meanwhile, Grant had been fighting and flanking Robert E. Lee’s army down to Cold Harbor east of Richmond. Rumors and reports abounded that the Confederate James River Fleet of three Virginia-class ironclads and seven gunboats would sortie down the river to attack the Union fleet. Phillips Lee reported “reliable” intelligence that the “enemy meditate an immediate attack upon this fleet with fire rafts, torpedo vessels, gunboats, and ironclads, all of which carry torpedoes, and that they are confident of being able to destroy the vessels here.”32 The Confederates did indeed “meditate” such an attack, but they were delayed by difficulties in getting the ironclads through their own obstructions at Drewry’s Bluff. They found the Union fleet on alert and called off the sortie, instead exchanging long-range fire with Union ironclads across a narrow neck where the James made a large loop creating a peninsula known as Farrar’s Island.33

James River Operations, May–June 1864

The possibility of such a sortie caused Union officials to consider sinking hulks at Trent’s Reach to create obstructions to prevent it. Phillips Lee was opposed; he wanted to fight enemy ironclads, not block them. “The Navy is not accustomed to putting down obstructions before it,” he declared. “The act might be construed as implying an admission of superiority of resources on the part of the enemy”—in other words, Lee might be accused of cowardice. Instead, he and his officers “desire the opportunity of encountering the enemy, and feel reluctant to discourage his approach.” Lee also hoped that a successful fight with enemy ironclads would get him promoted to rear admiral.

General Butler urged the sinking of obstructions; Phillips Lee told him bluntly that if they were to be placed, “it must be your operation, not mine.” Butler responded that he was “aware of the delicacy naval gentlemen feel in depending on anything but their own ships in a contest with the enemy,” but “in a contest against such unchristian modes of warfare as fire rafts and torpedo boats I think all questions of delicacy should be waived.” Exasperated, Lee countered that he would only sink the hulks “if a controlling military authority [that is, Grant] requires that it be done.”34

Grant did so order it when he decided to cross the army over the James and attack Petersburg. Phillips Lee reluctantly ordered Lieutenant Lamson to do it, which he did on June 15. And sure enough, the Northern press accused Lee of being afraid to fight the rebels. Lee was especially outraged by an article in the New York Herald, his chief tormentor, which declared that the placing of obstructions “has called an honorable blush to the cheek of every officer in his fleet. . . . [Lee] has ironclad vessels enough to blow every ram in the Confederacy to atoms; but he is afraid of the trial.” The Herald subsequently backed down and admitted that Grant had ordered the obstructions, but in a parting shot the newspaper stated that he did so because “he has no confidence” in Lee.35

By late June 1864, Grant had troops in place in front of both Petersburg and Richmond and settled in for a partial siege. Affairs on the James River also settled into a stalemate in which the two fleets remained behind their respective obstructions. The Union warships continued to convoy the steady stream of supply steamers up the river to Grant’s base at City Point. Welles ordered Lee to turn over the James River Fleet to Captain Melancton Smith and to move his own headquarters to Beaufort, North Carolina, where he could give more attention to the blockade.

With the concentration of so many vessels on the James River in May and June, the blockade off North Carolina had suffered some relapse. More and more runners were getting through. One of the most egregious violations of the blockade was accomplished by the CSS Tallahassee. Built in England as a fast cross-channel steamer named Atalanta, it became a blockade-runner in 1864 and made several successful runs to and from Wilmington. Because of its speed and strong construction, the Confederate navy purchased it in July 1864 and converted it into a commerce raider armed with rifled guns. Renamed the Tallahassee, she slipped out of New Inlet on the night of August 6, avoided two blockaders that fired on her in the dark, and cruised north along the Atlantic coast on the most destructive single raid by any Confederate ship. In the next nineteen days, she captured thirty-three fishing boats and merchant ships, burning twenty-six, bonding five, and releasing two. Naval ships hunted her from New York to Halifax and back to the Cape Fear River, which she reentered August 25 just ahead of pursuing blockaders.36

The Tallahassee’s exploits intensified Northern criticism of Phillips Lee and the Navy Department. Lee issued a flurry of new orders to tighten the cordon of ships off the two inlets of the Cape Fear River.37 By September these measures were paying off. Major General William H. C. Whiting, Confederate commander of the District of North Carolina and Southern Virginia, lamented “the loss of seven of the very finest and fastest of the trading fleet” in September. “The difficulty of running the blockade has been lately very great. The receipt of our supplies is very precarious.” One reason for the navy’s success in catching these runners was that the Tallahassee had taken all the anthracite coal available in Wilmington for her cruise. Left with only bituminous coal, the runners spewed clouds of black smoke that revealed them to the blockade fleet.38

DESPITE ITS SHORTCOMINGS, the blockade was clearly hurting the Confederate war effort by 1863–64. In Britain and France, however, Commander James D. Bulloch was trying his best to do something about that by contracting for ironclad cruisers to break the blockade and for more commerce raiders to prey on American merchant ships at sea.

Once Bulloch had provided for construction of the raiders that became the Florida and the Alabama, he turned his attention to the project of getting ironclad rams built in Britain. In July 1862 he signed a contract (ostensibly as a private citizen, not a Confederate agent) with the same Laird firm that had built the Alabama for construction of two formidable ironclads. They were to displace 1,800 tons, carry six 9-inch guns in three turrets, and be fitted with a seven-foot iron spike on the prow for ramming enemy ships below the waterline. The number of turrets was subsequently reduced to two, with pivot guns added fore and aft. These two ships—one scheduled for completion in March 1863 and the other two months later—would have been capable of wreaking havoc on the Union blockade. Although the presence of turrets made the warlike purpose of these “Laird rams” hard to disguise, Bulloch hoped to evade the British Foreign Enlistment Act by not having the ships armed and equipped in Britain—the same subterfuge that had allowed the Florida and the Alabama to escape.39

Meanwhile, in November 1862 Matthew Fontaine Maury had arrived in Britain to join the already crowded field of Confederate agents looking to buy or build ships for the navy. A famed hydrographer who had charted the ocean currents and had also developed torpedoes for the Confederacy, Maury managed to purchase a steamer named the Japan suitable to take on guns and become a commerce raider. In March 1863 she was ready to sail from the obscure port of White Haven. Maury sent coded messages to various Confederate and British officers to rendezvous there. The British Foreign Office decided to stop the Japan, but the telegram to White Haven sat in an outbox in London on March 31 until the port’s telegraph office had closed for the day. After midnight the Japan sailed, took on guns and ammunition off Ushant, and went to sea as the CSS Georgia. During the next six months, the Georgia destroyed nine prizes before limping into Cherbourg in broken-down condition, never to sail again as a raider.40

The embarrassment caused by the Georgia’s escape made the Foreign Office determined to prevent any more such occurrences. And in March 1863 the House of Commons had undertaken an investigation of the earlier cases of the Florida and the Alabama. Its report condemned the government for laxness in enforcement of British neutrality. At the same time, the American consul in Liverpool, Thomas H. Dudley, and Minister Charles Francis Adams flooded the Foreign Office with evidence of the Laird rams’ Confederate provenance. They also pressed Foreign Secretary Lord Russell to seize the Alexandra, a small steamer just completed in Liverpool as another commerce raider.

In April the government did seize the Alexandra. The Court of Exchequer ruled the seizure illegal on the grounds that there was no proof of Confederate ownership or of the arming or fitting out of the vessel in England. That was technically true—it had been built for Fraser, Trenholm, and Company, a British firm that just happened to be the Confederacy’s financial agent in London. The government appealed the Exchequer’s decision and continued to detain the Alexandra. The officer slated to command that ship pronounced its Confederate epitaph. “It is clear that the English Government never intends to permit anything in the way of a man-of-war to leave its shores,” he wrote. “I know Mr. Adams is accurately informed of the whereabouts and employment of every one of us, and that the Yankee spies are aided by the English Government detectives. . . . With the other vessels the same plan will be instituted as with the A[lexandra]. They will be exchequered, and thus put into a court where the Government has superior opportunities of instituting delays.”41

Recognizing the impossibility of getting the two Laird rams out of England under these changed circumstances, Bulloch arranged for the dummy purchase of them by Bravay & Company of Paris acting as agents for “his Serene Highness the Pasha of Egypt.” This subterfuge fooled no one. Thomas Dudley continued to amass evidence of their Confederate ownership, while Adams bombarded the Foreign Office with veiled threats of war if the rams were allowed to escape. On September 6, 1863, the British government detained the ships and subsequently bought them for the Royal Navy.42

In Glasgow, James North had signed a contract with the Thomson Works to build a 3,000-ton ironclad frigate for the Confederacy. Delays and cost overruns plagued the project. By the time the ship neared completion in late 1863, Bulloch acknowledged that “the chances of getting her out are absolutely nil.” North finally arranged for the sale of the ship to Denmark for more than the Confederacy had paid for it.43

Bulloch shifted his efforts to the apparently more friendly environs of France. Napoleon III and the French Foreign Ministry seemed willing to look the other way from Confederate intrigues to secure warships. Using funds and credit from the bond issue floated for the Confederates in Europe by the banking firm of Emile Erlanger, Bulloch contracted with French shipbuilders for construction of four “corvettes” as commerce raiders and two ironclad rams in 1863. In June 1864, however, Bulloch was forced to report the “most remarkable and astounding circumstance that has yet occurred in reference to our operations in Europe.” Napoleon had changed his mind and ordered the corvettes seized and sold to “bona fide” purchasers—that is, those not fronting for the Confederacy.44

Napoleon had evidently concluded that his delicate relations with the United States concerning French intervention in Mexico should not be complicated by allowing French-built warships to fall into Confederate hands. One of the two ironclads was sold to Sweden, which in turn sold it to Denmark, which was then at war with Prussia. Bulloch tried to arrange the sale of the second one also to Sweden to be then resold to the Confederacy. The U.S. legation in Paris discovered evidence of this fictitious sale and presented it to the French Foreign Ministry, which quashed the effort. The Confederate envoy in Paris, John Slidell, informed Secretary of State Judah Benjamin that “no further attempts to fit out ships of war in Europe should be made at present. . . . This is a most lame and impotent conclusion to all our efforts to create a Navy.”45

These disappointments caused Bulloch “greater pain and regret than I ever considered it possible to feel.”46 But he did not give up completely. In both France and England, he purchased and contracted for the construction of a dozen or more fast steamers as blockade-runners for the Confederate Navy Department, using money from the forced sales of the Laird rams and James North’s ironclad frigate.47

In the midst of all this activity came startling news from Cherbourg. On June 11, 1864, the CSS Alabama put in at this port for much-needed repairs. The USS Kearsarge arrived three days later to blockade the rebel raider. The Alabama’s captain, Raphael Semmes, decided to challenge the Kearsarge, which was commanded by Captain John A. Winslow, a shipmate of Semmes during the Mexican War. Semmes informed Flag Officer Samuel Barron, chief Confederate naval officer in Europe, that “I shall go out to engage her as soon as I can make the necessary preparations. . . . The combat will no doubt be contested and obstinate, but the two ships are so equally matched that I do not feel at liberty to decline it.”48

The Alabama’s armament consisted of six 32-pounders, a 68-pound smoothbore, and a 7-inch (110-pounder) British-made Blakely rifle. The Kearsarge was armed with four 32-pounders, two 11-inch Dahlgrens, and a 30-pounder rifle. She also had chain cables strung over vital parts of her hull to protect the engines and boilers. The Alabama steamed out of Cherbourg on the morning of June 19 as thousands gathered to watch the duel. The two ships met six or seven miles outside the harbor. They steamed in circles while pounding each other with starboard broadsides and their pivot guns. The Alabama fired faster but wilder, logging 370 shots to the Kearsarge’s more disciplined and accurate 173. One of the Alabama’s 110-pound rifle shells smashed into the Kearsarge’s sternpost—a potentially fatal shot, but it failed to explode.

Indeed, many of the Alabama’s shells did not explode because the powder was old and defective. The Kearsarge’s more accurate fire began to tell. After sixty-five minutes, the Alabama, in a sinking condition, struck her colors and sent a gig to the Kearsarge to ask for help to rescue her men from the water. Winslow sent his two undamaged boats and also signaled the Deerhound, an English yacht that had been watching the action, to come to their aid as well. The Deerhound picked up Semmes and most of his officers along with two dozen sailors, a total of forty-one men, and sailed for England, while an outraged Winslow, whose boats were rescuing other survivors, watched helplessly. “The Deerhound ran off with prisoners which I could not believe any cur dog could have been guilty of under the circumstances, since I did not open upon him,” wrote Winslow in disgust.49 The Kearsarge rescued seventy-seven of the Alabama’s crew, including twenty-one wounded; twenty-six were killed or drowned. On the Kearsarge only three were wounded, of whom one died.50 When the news arrived across the Atlantic, it produced elation in the North and mourning in the South for the loss of the famous raider, which had burned fifty-five merchant ships, ransomed nine, and sunk the USS Hatteras.

The duel between the USS Kearsarge (in the foreground) and the CSS Alabama, June 19, 1864. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress)

The Florida was still in action, but not for much longer. She captured and burned her last prize off the coast of Brazil on September 26, 1864, then put into the port of Bahia on October 4. The next day, Commander Napoleon Collins steered his USS Wachusett into the harbor. He had been on the lookout for the Florida; now that he had found her, he did not intend to let her go. Maintaining that the Florida had violated Brazil’s neutrality by bringing three prizes into one of its ports the previous year, Collins considered her fair game. At 3:00 A.M. on October 7, while the Florida’s captain and several officers were ashore, the Wachusett got up steam and rammed the raider on the starboard quarter. Failing to sink her, the Wachusett took her in tow and steamed out of the harbor.

Brazilian guns fired on the Wachusett but failed to hit her, and Collins got away with his prize. He brought it back to Hampton Roads to a big welcome but also an international outcry about violation of Brazilian sovereignty. Brazil demanded the return of the Florida and an apology. She got the latter, but the Florida sank at Hampton Roads after an “accidental” collision with an army boat. Collins was tried by court-martial and dismissed from the navy in April 1865, but sixteen months later, Welles restored him to command, and he later retired as rear admiral.51

While the Union navy basked in the glow of success in the sinking of the Alabama, it suffered embarrassment over the fiasco of the Casco class of shallow-draft monitors. These twenty single-turret, two-gun ironclads were initially designed by John Ericsson to have a six-foot draft, but they were repeatedly altered by Chief Engineer Alban Stimers and by Fox, so that when the first one, the USS Chimo, was launched in May 1864, it seemed to have been designed by a committee—each member of which knew nothing of what the others were doing. Without turret and stores, the Chimo floated with only three inches of freeboard; if fully loaded and equipped, it would have sunk. The builders made modifications and finally launched another ship of this class, the USS Tunxis, which almost foundered in September 1864 before it could get back to the dock. Only eight of the class were completed by the time the war ended, and none of them ever went into action.52

The failure of these vessels contrasted sharply with the success of the turreted river monitors in the Mississippi valley designed by James B. Eads, which did good service, especially in the Battle of Mobile Bay in August 1864. With that victory and with the capture of Fort Fisher and Wilmington six months later, the Union navy made two of its most significant contributions to ultimate victory in the war.