Chapter Eleven

Damn the Torpedoes

Ever since the spring of 1862, several high-ranking Union officers—Farragut, Grant, and Banks—had been proposing attacks on Mobile. But other priorities always took precedence: control of the Mississippi; the attack on Charleston, which tied up most of the ironclads; Banks’s expeditions to Texas in the fall of 1863; and the Red River Campaign in the spring of 1864. In February 1864 Farragut champed at the bit once again. He wrote to his son, a cadet at West Point, that “if I had the permission I can tell you it would not be long before I would raise a row with the Rebels in Mobile.”1 With the abandonment of the Red River Campaign in May 1864 and the removal of Banks from field command, the stage was finally set for a combined operation against Mobile Bay with Farragut’s fleet and soldiers from the Army of the Gulf, now commanded by Major General Edward Canby.

The Confederate defenses of Mobile Bay had been much improved by then. The South’s only admiral, Franklin Buchanan, had taken command at Mobile in September 1862 and had built a naval squadron around the ironclad CSS Tennessee and two other uncompleted ironclads. Afflicted by shortages of everything from armor plate to experienced crew, Buchanan nevertheless put up a bold front that convinced Farragut in May 1864 that the Confederate fleet might come out and attack his blockaders. Buchanan did think of doing so, but he never managed to come out. Farragut was disappointed. “I . . . wish from the bottom of my heart that Buck would come out and try his hand upon us,” Farragut wrote in June. “We are ready to-day to try anything that comes along, be it wood or iron. . . . Anything is preferable to lying on our oars.” In July Farragut’s squadron finally got ironclads of its own: the double-turreted river monitors USS Chickasaw and USS Winnebago arrived off Mobile Bay. Soon to follow were the seagoing

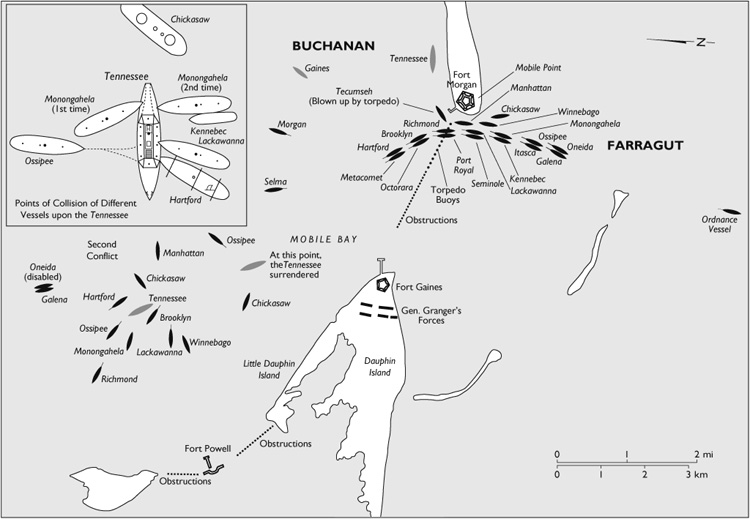

The Battle of Mobile Bay, August 5, 1864

monitors USS Manhattan and USS Tecumseh, each carrying two 15-inch Dahlgrens in its turret.2

The Manhattan and the Tecumseh were the newest monitors, but they were just as uncomfortable as their predecessors. A lieutenant in the Manhattan on its way to Mobile complained in his diary on July 1: “The day has been so excessively hot that I am almost melted. . . . Everything is dirty, everything smells bad, everybody is demoralized. . . . A man who would stay in an ironclad from choice is a candidate for the insane asylum, and he who stays from compulsion is an object of pity.” The next day was even worse. “I can’t imagine how the firemen and coalheavers stand it,” the lieutenant wrote. “The thermometer in the fireroom stands at 135° to 138°. The Chief Engineer goes in there semi-occasionally to superintend the work and comes out again wringing wet, [cursing] all the ironclad fleet.”3

By the end of July, Farragut had his fleet assembled and his plan of attack laid out. The four ironclads would lead the way on the right flank closest to Fort Morgan, the main Confederate defensive work at the mouth of the bay with eighty-six guns. The fourteen wooden ships would go in on their left, lashed together in seven pairs with the larger ships to starboard to absorb the fire from Fort Morgan. The Confederates had laid some 189 torpedoes across the channel, leaving an opening of perhaps 200 yards closest to Fort Morgan for blockade-runners. It was through this opening that Farragut planned to take his ships. After running this gauntlet, he would engage the Tennessee and the three Confederate gunboats in the bay. The eighteen Union ships would outgun the four Confederate vessels 147 to 22.

The paymaster’s clerk on the USS Galena described the preparation of his ship for the anticipated battle. The Galena had been rebuilt from the unsuccessful ironclad of 1862 into a three-masted wooden screw sloop. Its equipage was typical of the wooden vessels at Mobile Bay. “We are well prepared for the fight,” wrote the clerk. “The topmasts & yards are all sent down, chain Cable on the side, sand bags all around the boilers, cable over engine room hatch, sails & Hammocks around the wheel to protect it, splinter netting all around the ships sides, all the railing & stanchions of whatever kind removed.”4

Major General Gordon Granger had landed on Dauphin Island on August 3 with 1,500 troops to invest Fort Gaines, three miles across the entrance from Fort Morgan, while five gunboats attacked Fort Powell at Grant’s Pass, a shallow channel another five miles to the northwest. On the morning of August 5, the main fleet weighed anchor and proceeded toward the principal entrance to the bay. A southwest breeze blew the smoke toward Fort Morgan, which opened on the ships as they came within range. The leading monitor, Tecumseh, struck a torpedo and went down in less than a minute, taking ninety men with her. The USS Brooklyn and her consort, the USS Octorara, hesitated at the line of torpedoes, and the whole parade of ships came to a halt under the punishing guns of Fort Morgan.

Next in line was Farragut’s flagship, the USS Hartford. He ordered the Hartford and her consort, the USS Metacomet, to pass the Brooklyn, and in that moment a legend was born. “Damn the torpedoes! Full speed ahead!” Farragut supposedly shouted. A marine on the Hartford standing near Farragut later said that he had not heard any such cry.5 Whether Farragut said these words or not, he certainly did order the Hartford to go ahead. Percival Drayton, the captain commanding the flagship, described these events. When the Tecumseh went down, “our line was getting crowded and very soon we should all have been huddled together, a splendid mark for the enemy’s guns,” Drayton wrote. “The Admiral immediately gave the word to go ahead with the Hartford and pass the Brooklyn. We sheered to port, passing the Brooklyn on our starboard side. . . . We passed directly over the line of torpedoes planted by the enemy, and we could hear the snapping of the submerged devilish contrivances as our hull drove through the water—but it was neck or nothing, and that risk must be taken. All the other vessels followed in our wake and providentially all escaped.”6 The rapid and shifting currents in the channel off Fort Morgan had evidently broken loose some of the torpedoes and caused others to leak, dampening the powder.

As the Hartford forged ahead dueling with the guns of Fort Morgan, Farragut climbed the rigging for a better view above the smoke and was lashed to the shrouds by the boatswain. A rifleman on the Tennessee fired several shots at him. If the shooter had managed to hit him, Farragut would have been a martyred hero like Horatio Nelson at Trafalgar instead of merely the hero of Mobile Bay.7 Once past Fort Morgan and into the bay, the Hartford and the Brooklyn engaged the Tennessee, which tried to ram them in turn but was too slow. The Hartford cut loose its consort, the Metacomet, which went after the Confederate gunboat Selma and captured her. One of the other Southern gunboats was sunk by gunfire from several Union ships, and the third fled thirty miles up the bay to Mobile.

The Tennessee retreated temporarily under the protection of Fort Morgan, while the Union ships rendezvoused out of range to decide what to do next. Suddenly the Tennessee came at them, alone, in a do-or-die mission to take on the whole fleet. Several of Farragut’s ships rammed the Tennessee without much effect, while the monitor Chickasaw hung on her stern and peppered her with 11-inch bolts while the monitor Manhattan fired her 15-inch guns at point-blank range. With the Tennessee’s smokestack riddled, her steering chains cut, and Admiral Buchanan badly wounded (he would recover), the Confederate ironclad finally struck her colors.8

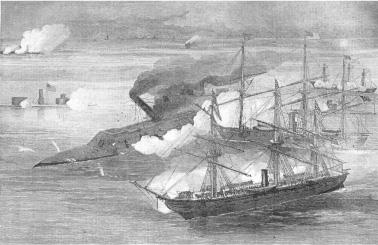

The capture of the CSS Tennessee by the Union fleet in Mobile Bay, August 5, 1864. The ship about to ram the Confederate ironclad is the USS Hartford, with Rear Admiral Farragut’s pennant flying on the foremast. The double-turreted river monitors USS Winnebago (on left) and USS Chickasaw, plus the single-turreted USS Manhattan, combine with two other sloops of war to surround the crippled Tennessee. (From Harper’s Pictorial History of the Civil War)

During the action, a twenty-year-old ensign in charge of a section of guns on the USS Monongahela described an adrenalin-fueled high as his ship rammed the Tennessee twice and poured broadsides into her. “I felt such pride and such a-good-all-over feeling that I wonder I did not go up in smoke,” he wrote to his father two days later. “During the battle, the wildest enthusiasm prevailed. . . . I’ll go through a dozen battles to feel that way again.”9

Taking stock of the casualties after the fighting was over, however, sobered men quickly. The lieutenant from the Manhattan who boarded the Tennessee to take possession of her colors wrote that “her decks looked like a butcher shop. One man had been struck by the fragments of one of our 15-inch shot, and was cut into pieces so small that the largest would not have weighed 2 lbs.”10 The Hartford was the hardest hit of the Union ships (except the Tecumseh), with twenty-five killed and twenty-eight wounded. A marine-corps private on the Hartford reported that “our ship presented a fearful sight after the action. A shell burst in the steerage tearing everything to pieces. A great many shots came in on the berth deck. . . . Our cockpit looked more like a slaughter house than anything else. At night twenty-one dead bodies were sewed up in hammocks . . . and taken away for burial.”11

In addition to the ninety men drowned in the Tecumseh, the Union fleet altogether suffered fifty-two killed and 170 wounded. Confederate casualties were only twelve killed and twenty wounded—plus 243 captured. By the standards of land battles in the Civil War, this was a small butcher’s bill for such an important victory, which sealed off Mobile from blockade-runners.

But the victory was not complete until the Confederate forts surrendered. The Chickasaw poured a heavy fire into Fort Powell on the afternoon of August 5, and the Confederates evacuated it that night. The next day, the monitors pounded Fort Gaines while 3,000 Union troops moved against its land face. On August 8 it also surrendered. Fort Morgan proved a tougher prospect. For two weeks, Union warships—now including the repaired Tennessee—fired tons of metal into the fort while General Granger’s troops moved inexorably forward and added army artillery to the mix. On August 23 Fort Morgan finally surrendered.

Ironically, this was the same day that President Lincoln penned his “blind memorandum” (so called because he asked his cabinet members to endorse it sight unseen) stating that because of Northern war weariness and the lack of important victories in 1864, he was likely to be defeated for reelection. News of the capture of all the forts at Mobile Bay reached the North a few days later. A neighbor of the Farraguts at Hastings-on-the-Hudson in New York wrote to the admiral that this news was “doing a great deal more than perhaps you dream of, in giving heart to the people here, and raising their confidence. Your victory has come at a most opportune moment, and will be attended by consequences of the most lasting and vital kind to the republic.”12 General Sherman’s capture of Atlanta on September 2 further electrified the North. In combination with other Union successes during the fall of 1864, Mobile Bay and Atlanta helped assure Lincoln’s reelection after all.

With complete control of Mobile Bay, Farragut advised against efforts to capture the city itself. “I consider an army of twenty or thirty thousand men necessary to take the city of Mobile and almost as many to hold it,” Farragut told Welles. Even if captured, “I can not believe that Mobile will be anything but a constant trouble and source of anxiety to us.”13 For the time being, Farragut’s advice prevailed. General Canby provided a small force to garrison the forts, and several gunboats maintained a presence in the bay. The following spring, a combined operation did capture Mobile—after the navy lost seven vessels to torpedoes there, including two monitors. The city of Mobile surrendered on April 12, 1865—three days after Appomattox.

FOLLOWING THE SUCCESS at Mobile Bay, Welles had a new mission for Farragut. After much backing and filling, both the army and the navy were finally in accord about a major effort to capture Fort Fisher and close down the port of Wilmington. Since the winter of 1862–63, Acting Rear Admiral Samuel Phillips Lee had come up with several proposals for a combined operation against Fort Caswell, Fort Fisher, or both. But General Halleck could never spare the troops for such a campaign, and Charleston continued to have priority for the ironclads and troops that were available. By September 1864, however, Grant seemed ready to provide enough troops to cooperate with the navy for an attack on Fort Fisher. Lee expected to command the naval part of this effort, but Welles thought he was not the man for the job. Lee “is true and loyal, careful, and circumspect almost to a fault,” wrote Welles in his diary, “but while fearless he has not dash and impetuous daring.”14 Farragut had those qualities in abundance, so Welles selected him to take Lee’s place as commander of the North Atlantic Squadron. Lee would switch with Farragut and take over the Gulf Squadron.

Welles’s letter to Farragut, however, crossed with one from Farragut to him in which the officer stated that constant service in the Gulf and on the Mississippi had broken down his health, and he requested a respite. Welles granted the request and turned instead to David D. Porter to command the Fort Fisher attack. “It will cut Lee to the quick,” Welles acknowledged, “but again personal considerations must yield to the public necessities.” Welles ordered Porter east to take over the North Atlantic Squadron and sent Lee west to replace Porter as head of the Mississippi Squadron.15

Porter took command with the energy and determination Welles expected of him. He assembled a large fleet for the attack. The army still dragged its feet, reluctant to take troops from the siege of Petersburg and Richmond. Grant finally detached 6,500 troops from the Army of the James and put twenty-nine-year-old Major General Godfrey Weitzel in command of them. The navy would land them north of the L-shaped Fort Fisher to attack its land face while the fleet bombarded the huge earthen fortification from the sea. Weitzel’s superior, Benjamin Butler, decided to accompany the expedition and, in effect, to supersede Weitzel.

The controversial Butler also came up with a scheme to fill an old ship with gunpowder, take it as close to the sea face of Fort Fisher as possible, and explode it. He had read of the accidental explosion of two powder barges at the British port of Erith, which had leveled nearby buildings. If the explosion of a ship could do the same to Fort Fisher, it might dismount many guns and stun the garrison. Butler presented his idea to the Navy Department. Porter and Fox were enthusiastic. They consulted several engineers and weapons experts, some of whom expressed skepticism. But in a memorandum dated November 23, 1864, Porter summarized the majority consensus: “The explosion would injure the earthworks to a very great extent, render the guns unserviceable for a time, and probably affect the garrison to such a degree as to deprive them of the power to resist the passage of naval vessels by the forts and the carrying of these works by immediate assault.”16

Porter supervised the loading of the USS Louisiana with more than 200 tons of powder and ordered Commander Alexander Rhind to take her as close to Fort Fisher at night as he could get, anchor her, and set the timers that were designed to explode the powder when the escape ship got far enough away. “Great risks have to be run, and there are chances that you may lose your life in this adventure,” Porter told Rhind, “but the risk is worth the running, when the importance of the object is to be considered and the fame to be gained by this novel undertaking. . . . I expect more good to our cause from a success in this instance than from an advance of all the armies in the field.”17

After delays because of bad weather, the Louisiana finally went in on the night of December 23–24. Rhind reported that he anchored her within 300 yards of the fort (it was actually 600 yards), set the timers, lit backup slow fuses in case the timers did not work, and departed on the escape ship USS Wilderness. As thousands of eyes in the fleet several miles away watched anxiously, the moment of 1:18 A.M. for the timed explosion went by, then more minutes until at 1:46 A.M. on December 24, an explosion lit the sky—actually four explosions, for the timers did not work and the various powder compartments exploded separately, with the first explosion probably blowing some of the unexploded powder overboard. The force of the blast was thus much diminished, and the current had also dragged the insecurely anchored ship farther from the fort. As a consequence, the explosion did almost no damage. Butler took some ridicule for this fizzle—but it was not a fair test of the scheme.18

This failure left it up to the naval bombardment to soften Fort Fisher for an assault by Butler’s troops. Porter’s fleet steamed into position by noon on December 24, with each of the thirty-seven ships (including five ironclads) assigned a particular area of the fort as a target. Nineteen smaller gunboats were held in reserve. For five hours, the fleet poured 10,000 rounds of shot and shell into the fort, setting barracks on fire, knocking out a few guns, and causing other damage. But many of the shells buried themselves in the sand and sod before exploding, doing little harm. The fort fired back sparingly, for Colonel William Lamb, its commander, knew that he had only 3,000 rounds for his forty-four guns and needed to save some for the infantry assault.

Butler’s troops arrived that evening, the general furious with Porter for attacking before they got there. The two men had maintained ill will toward each other since feuding during the New Orleans campaign back in 1862. On Christmas morning, Porter renewed the bombardment, pouring another 10,000 rounds into the fort, while part of the fleet covered the landing of troops a few miles to the north. An advance unit reconnoitered the land face of the fort. Weitzel concluded that the defenses were too strong and insufficiently damaged by the shelling for an attack to succeed. Butler decided to call it off and reembark his troops.

Porter was furious. After only an hour and a half of firing on the first day, he had reported that the batteries in the fort “are nearly demolished. . . . We have set them on fire, blown some of them up, and all that is wanted now is the troops to land and go into them.” After Butler withdrew, Porter could scarcely find words to denounce the army for “not attempting to take possession of the forts, which were so blown up, burst up, and torn up that the people inside had no intention of fighting any more. . . . It could have been taken on Christmas with 500 men, without losing a soldier. . . . I feel ashamed that men calling themselves soldiers should have left this

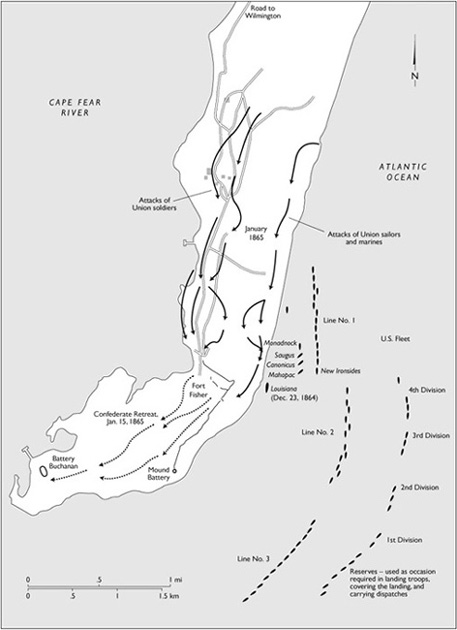

U.S. Naval Bombardment of Fort Fisher, December 1864 and January 1865

place so ingloriously; it was, however, nothing more than I expected when General Butler mixed himself up in this expedition.”19

Porter’s claims of damage to the fort were greatly exaggerated. Colonel Lamb reported that on the first day, the fleet’s fire “tore up large quantities of the earthworks, splintered some of the revetments, but did not injure a single bombproof or endanger any magazine.” On the second day, “a few more quarters were burned, more of the earthworks were displaced, but none seriously damaged, and [only] five guns were disabled by the enemy.” The Cape Fear district commander, Major General William H. C. Whiting, noted that the naval fire was concentrated mainly on the sea face of the fort, leaving the land face and its nineteen guns relatively intact. Because of the smoke and dust, Union gunners used the fort’s flag as an aiming point. Noticing this, Lamb had moved the flag back toward the Cape Fear River, causing many of the shots to fly harmlessly over the fort.20

Whatever the truth of these contrasting reports, Porter’s claims resonated with Grant, who had been looking for an excuse to get rid of Butler. He told Porter to keep his fleet ready and he would send the troops back under a new commander. At Grant’s behest, Lincoln relieved Butler, and Grant named Brigadier General Alfred Terry to command a beefed-up contingent of 8,000 troops for a renewed attack on Fort Fisher.

Porter and Terry hit it off, and the second attack was much better planned than the first. In an implicit admission that the shelling on December 24–25 did not inflict as much damage as he had reported, Porter issued special orders to his gunners to fire at the fort’s gun emplacements, not the flagstaff.21 On January 13 the fifty-nine vessels of the fleet opened a deadly barrage. The New Ironsides and four monitors moved to within a thousand yards and systematically knocked out all but one of the heavy guns on the land face, breached the stockade in many places, and plowed up the land mines and their wires in front of the stockade.

For two days, this shelling continued. On the evening of January 14, Porter and Terry planned for a coordinated assault at 3:00 P.M. the next day. Two thousand sailors and marines would land on the beach and attack the bastion at the corner of the land and sea face while 4,000 soldiers would charge the other end of the land face. A week earlier, Porter had written to Fox: “I don’t believe in any body but my own good officers and men. I can do anything with them, and you need not be surprised to hear that the web-footers have gone into the forts. I will try it anyhow, and show the soldiers how to do it.” He armed 1,600 sailors with cutlasses and revolvers and ordered them to “board the fort in a seaman-like way,” while the 400 marines “will form in the rear and cover the sailors.”22

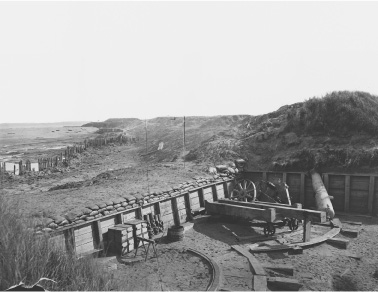

Part of the land face of Fort Fisher after the Union naval bombardment and army assault on January 15, 1865. Note the dismounted gun next to one of the traverses and the stockade splintered by Union shells. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress)

On January 15 the sailors and marines landed on the beach and rushed the parapet. They were a few minutes ahead of the soldiers, so the fort’s defenders crowded the bastion and decimated the sailors with heavy fire. Porter blamed the marines for the failure of this attack: “The marines could have cleared the parapets by keeping up a steady fire, but they failed to do so” and then broke and ran.23

But if the sailors did not succeed in their effort to “board the fort,” their attack diverted the defenders so that when the soldiers attacked the northwest corner, they got into the fort with minimal opposition. They then fought their way from traverse to traverse against increasingly furious opposition. In a striking example of coordination in that pre-radio age, the warships (especially the New Ironsides) brought down fire on each of thirteen traverses just ahead of the Union troops as they cleared one after another. Fighting in the front lines with their men, Colonel Lamb and General Whiting were wounded (the latter mortally). Desperate resistance continued after dark, but the Union forces finally prevailed. At the cost of about a thousand casualties, they captured more than 2,000 Confederates and all of the fort’s guns and equipment.24

It was the crowning achievement of combined operations in the war. Naval ships entered the Cape Fear River through New Inlet to shell Fort Caswell from the rear. The Confederates evacuated that fort and blew it up. Three blockade-runners, unaware that the river was in Union hands, were decoyed in by Lieutenant Commander William B. Cushing’s operation of the range lights. “We are having a jolly time with the blockade runners, which come into our trap,” Porter told Fox. “We almost kill ourselves laughing at their discomfiture, when they find they have set out their champagne to no purpose, and they say it is ‘a damned Yankee trick.’ . . . This is the greatest lark I ever was on.”25

The capture of Fort Fisher closed the last blockade-running port except faraway Galveston. (A few runners had been getting into Charleston in recent months by using Maffitt’s Channel close to Sullivan’s Island. The last one got in just before the evacuation of Charleston on the night of February 17–18, 1865.) Confederate Vice President Alexander Stephens considered the loss of Fort Fisher “one of the greatest disasters which has befallen our Cause from the beginning of the war.”26 The advance up the river by Porter’s gunboats and army troops to capture Wilmington on February 22 was something of an anticlimax. The same was true of the occupation of Charleston when the Confederates evacuated it on February 18 after Sherman’s army cut the city’s communications with the interior on their march through South Carolina. Clearly, the end of the Confederacy was in sight. But action continued on several fronts during the winter and spring of 1864–65.

While part of the James River Fleet was absent on the Fort Fisher campaign, Confederate Secretary of the Navy Stephen Mallory ordered Flag Officer John K. Mitchell, commander of the South’s own James River Fleet, to attack Grant’s supply base at City Point. Heavy rains in the James River’s watershed raised the river level enough that Confederate ironclads had a chance to get over the Union obstructions at Trent’s Reach twenty river miles above City Point. “I regard an attack upon the enemy . . . at City Point to cut off Grant’s supplies, as a movement of the first importance,” Mallory told Mitchell. “You have an opportunity . . . rarely presented to a naval officer and one which may lead to the most glorious results to your country.”27

With three ironclads carrying four guns each—the Virginia II, the Fredericksburg, and the Richmond—and eight smaller consorts, including two torpedo boats, Mitchell came down on the night of January 23–24. The Union fleet of ten gunboats, including the double-turreted monitor USS Onondaga with its two 15-inch Dahlgrens and two 150-pound rifles, dropped several miles downriver to a spot where they had maneuvering room against the enemy—or so their commander, Captain William A. Parker, later explained. But to General Grant, it looked like a panicked retreat. Grant himself untypically pushed the panic button. He fired off telegrams to Welles and ordered naval vessels back up to the obstructions on his own authority, complaining that “Captain Parker . . . seems helpless.” Two of the three Confederate ironclads ran aground at the obstructions; army artillery blasted them and the Fredericksburg, which had gotten through but was forced to return; the Onondaga came back upriver and added its big guns to the heavy fire that sank two Confederate gunboats and compelled the rest to retreat.28

In the end, this affair seemed like much ado about very little. But it resulted in the replacement of both fleet commanders. Lieutenant Commander Homer C. Black replaced Parker despite the latter’s pleas for a second chance. He was later tried by court-martial and found guilty of “keeping out of danger to which he should have exposed himself.” But the court recommended clemency in view of his thirty-three years of honorable service, “believing that he acted in this case from an error of judgment.” Welles accepted the clemency recommendation, but Parker’s career was essentially over.29 On the Confederate side, Mallory replaced Mitchell with Raphael Semmes, recently promoted to admiral and without a command.30 Semmes’s principal accomplishment as chief of the James River Squadron was to order its ships blown up when the Confederates evacuated Richmond on the night of April 2–3, 1865.

SAMUEL PHILLIPS LEE was indeed “cut to the quick” by Welles’s decision to replace him as commander of the North Atlantic Squadron just before the Fort Fisher campaign. But Lee went to work as head of the Mississippi Squadron with an earnest will. He was greeted soon after his arrival by a minor disaster at Johnsonville on the Tennessee River about thirty miles south of Fort Henry. Union forces in Tennessee had established a large supply depot at Johnsonville on the east bank connected by rail with Nashville. Many of the supplies for Sherman’s army in Georgia came up the Tennessee River by convoy and were shipped by rail from Johnsonville to Nashville and then south to Sherman. On November 4, 1864, 3,500 Confederate cavalry under Nathan Bedford Forrest appeared on the west bank and opened fire on the eleven transports and eighteen barges unloading at Johnsonville under the protection of three tinclads. The latter exchanged fire with Forrest’s guns for a half hour but could not maneuver in the narrow river full of sandbars and shoals. The crews set fire to the gunboats and other vessels, while Forrest’s guns shifted their fire to the unloaded supplies and warehouses, destroying them as well. Forrest subsequently crossed the river and joined General John Bell Hood’s army in its invasion of Tennessee.31

The autumnal rise in the Cumberland River made it navigable to Nashville in November 1864, so the Mississippi Squadron shifted its supply convoys to that river to support Major General George H. Thomas’s confrontation with Hood. Phillips Lee sent two tinclads and the ironclads Neosha and Carondelet to Nashville, where they prevented Hood’s left wing from crossing the Cumberland above the city and bolstered Thomas’s crushing attack that routed Hood’s army on December 15 and 16. As he pursued the retreating Confederates, Thomas asked Lee to send gunboats up the Tennessee River as far as they could go to find and destroy boats and pontoon bridges that the Confederates could use to cross the river. Hood was forced to cross above Muscle Shoals at a point the gunboats could not reach, but the navy’s active patrolling of 175 miles of the river below Muscle Shoals cut off the retreat of hundreds of stragglers, contributing to the demoralization and disintegration of the Confederacy’s second-largest army.32

Hood’s invasion and retreat were the last gasp of Confederate forces in the West. After the fall of Richmond and the flight of the Confederate government, Secretary Welles sent an alert to naval forces to be on the lookout for Jefferson Davis and his cabinet, reported to be on their way to Texas to continue the war. Lee mobilized his entire squadron for intensive patrols of the Mississippi and its tributaries, hoping to catch the biggest prize of all.33 But it was not to be; Davis got no farther than Irwinville, Georgia, where Union cavalry captured him on May 10, 1865.

NEWS OF THE END OF THE WAR traveled slowly across the oceans, where two Confederate warships were still in action, or hoping to be. Despite repeated failures to get ships out of Britain and France in 1863–64, James D. Bulloch kept trying. Secretary of the Navy Mallory wanted him to buy a fast ship to prey on the American whaling fleet. “The success of this measure would be such an effective blow upon a vital interest as would be felt throughout New England,” wrote Mallory in late 1864. “I regard a vigorous attack upon this interest as one of the heaviest blows we can strike the enemy”—surely an example of wishful thinking.34

In September 1864 Bulloch managed to buy in England a large vessel involved in the Bombay trade, the Sea King. He took elaborate precautions to disguise Confederate ownership and sent her to Madeira with an English crew to meet the Confederate commander, James I. Waddell. Taking on her armament and supplies there and changing her name to CSS Shenandoah, she steamed southward around the Cape of Good Hope, into the Indian Ocean, and finally to the whaling grounds in the Bering Sea in June 1865. Unaware that the war had ended, the Shenandoah captured and destroyed thirty-two whaling ships (having burned six merchant vessels earlier) before finally learning in August 1865 from a British ship that the war was indeed over. Waddell sailed his ship all the way back to Liverpool and turned it over to the British government after circumnavigating the globe.35

Even more futile in forwarding the Confederate cause was the saga of the CSS Stonewall. This ship was none other than one of the ironclad rams Bulloch had originally contracted for in France that was sold to Denmark. Its delivery was delayed until the Danish war with Prussia over Schleswig-Holstein had ended, when Denmark sold it back to the French builder. Using a go-between and complicated codes to keep the process secret, Bulloch acquired the ship for the Confederacy in December 1864.

Flag Officer Samuel Barron had big ambitions for this vessel, signified by naming it the Stonewall. It was armed with a 300-pound rifle, two 70-pound rifles, and a lethal ram at the bow. Its first task would be to break the blockade of Wilmington, then to capture the California gold steamers between Aspinwall and New York, and finally “a dash at the New England ports and commerce might be made very destructive. . . . A few days cruising on the banks may inflict severe injury on the fisheries of the United States.”36

The Stonewall headed for the South Atlantic coast in March 1865 but got only as far as the port of Ferrol in northwest Spain, where it put in because of bad weather and needed repairs. The USS Niagara, a large steam frigate armed with thirty-two heavy guns, arrived at Ferrol to maintain a watch on the Stonewall and was soon joined by the ten-gun USS Sacramento. On March 24 Confederate Captain Thomas J. Page took the Stonewall to sea expecting to fight the two Union warships. Living down to his name, Captain Thomas T. Craven of the Niagara watched the Stonewall go without firing a shot. “The odds in her favor were too great,” Craven explained to Welles, “to admit of the slightest hope of being able to inflict upon her even the most trifling injury, whereas, if we had gone out, the Niagara would undoubtedly have been easily and promptly destroyed. So thoroughly a one-sided combat I did not consider myself called to engage in.”37

Captain Page could scarcely believe he had gotten away without a fight. “This will doubtless seem as inexplicable to you as it is to myself,” he wrote to Bulloch. “To suppose that these two heavily armed men-of-war were afraid of the Stonewall is to me incredible.”38 Welles found it incredible, too, and when the Niagara returned to the United States, he ordered a court-martial trial of Craven, which convicted him and sentenced him to suspension for two years with leave pay. Welles was furious at this light sentence and set aside the verdict because he did not want it on record. Craven was subsequently promoted to rear admiral and retired in 1870.39

Meanwhile, the Stonewall made it to Havana, where Captain Page learned that the war was over. He sold the Stonewall to Spain, which in turn sold her to the United States. Thus ended the story of Confederate commerce raiders, except for the Shenandoah, which was still destroying whalers 5,000 miles from the now-defunct Confederacy.