In February 1862 a band of fifteen to twenty slaves fled from their plantation along the Chowan River in northeastern North Carolina, boarded a small boat, and floated downriver toward the Albemarle Sound. The group, which consisted of men, women, and children, had heard about the Union occupation of Roanoke Island only days earlier. Union forces under the command of Gen. Ambrose Burnside had overwhelmed the nominal Confederate defenses, establishing a base from which they could move against the North Carolina mainland. The fugitive slaves also knew that slave owners in the region were beginning to remove their human property inland to isolate them from the threat posed by the presence of Union soldiers.

Their departure did not go unnoticed, as their owners chased them along the riverbank with dogs and unsuccessfully fired at them. In the pouring rain, they made their way to the Federal encampment on Roanoke Island. Met there by Union soldiers, most of whom came from New England and some of whom professed abolitionist sentiments, the “happy party rejoic[ed] at their escape from slavery and danger, and at the hearty welcome which was at once extended to them.” Cold and dripping wet, the women and children in the party were offered shelter by Vincent Colyer, a civilian representing the U.S. Christian Commission, who volunteered his tent.1

The fugitive slaves sheltering in Vincent Colyer’s tent represented the first wave of thousands of refugees in eastern North Carolina during the Civil War. The Burnside invasion of 1862 created several distinct streams of refugees. The first and the largest was composed of the thousands of African Americans who escaped from slavery to the potential and promise of freedom under the banner of the Union army. The second stream, almost as large as the first, consisted of pro-Confederate civilians who moved into the North Carolina interior in advance of the Union invasion. Many of these pro-Confederate refugees brought their slaves with them to central and western North Carolina in order to place as much distance between them and Union armies as possible. Finally, a smaller third stream of white Unionists fled from their homes in Confederate-controlled territory into Union-occupied towns.

The following chapters highlight three themes about the refugee experience in eastern North Carolina. First, refugees dealt with significant material and physical hardships. Housing and food shortages, overcrowding, and disease were chronic problems in eastern North Carolina throughout the Civil War, and these problems grew more significant as the refugee population increased. Second, the contested status of slavery and loyalty shaped the nature of the refugee experience. The first black refugees arrived inside Union lines when that did not necessarily entail freedom, a freedom that remained contested for the duration of the war. White refugees entering Union lines had to demonstrate and perform their fidelity to the Union cause, constantly under the suspicion of disloyalty. Third, both white and black refugees had to work with and against military officials, soldiers, and Northern aid workers, many of whom had their own priorities and prejudices concerning refugees. Each of these themes contributes to a deeper understanding of the refugee experience and the formation of refugee communities.

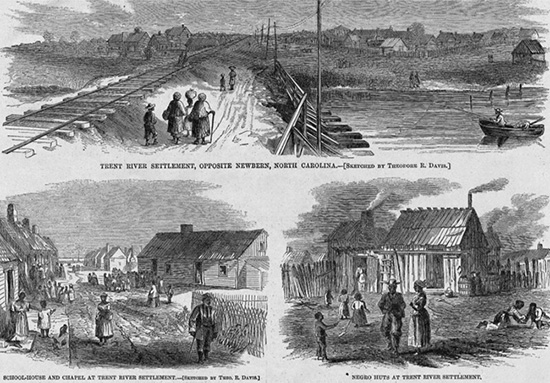

In eastern North Carolina, refugee communities were formed within the confines and context of refugee camps. The refugee camps established in early 1862 matured over the next three years, becoming increasingly overcrowded, polluted, and disease-ridden. Historian Jim Downs has recently described black refugee camps as “holding grounds” created by the federal government to contain fugitive slaves until they could “re-create the plantation labor force,” with the federal government taking “over the role of slaveholders.” According to Downs, “contraband camps performed a similar function to antebellum slave pens where auctioneers held people before they were sold on the market.”2 Although Downs has identified a thread of paternalism that informed the creation of refugee camps, his characterization obscures and distorts much more complex processes at work. As Downs points out, for black and white refugees, living in refugee camps meant dangerously overcrowded conditions, poor sanitation that promoted epidemic disease, and federal officials who often did not sympathize or understand what refugees wanted or needed. However, camps were also sites where refugees raised (and rebuilt) families, established churches, schools, and fraternal organizations, and crafted new identities. They were the birthplace of Southern free labor and black politics. Their construction and development were the result of a complex and often contentious partnership between the federal government (especially the army), relief workers, and the refugees themselves. They were neither purely places of oppression nor sites of liberation, but oftentimes both.

Compared to the white refugees who fled to the Piedmont, who left voluminous records of their experiences in diaries and letters, black refugees on North Carolina’s coast left few written accounts, especially during their early months in New Bern. Evidence of their experiences must be read primarily through the words of white Union soldiers and relief workers like Vincent Colyer. The windows that they provide into the black refugee experience are both revealing and limited. Even sympathetic whites, like the abolitionist Vincent Colyer, brought with them decades of prejudices and misconceptions that blinded them to black refugees’ priorities, hopes, and needs. Most white Union soldiers held racist assumptions about African Africans that colored their accounts of black refugees. Reconstructing the lived experience of black refugees, therefore, requires reading these sources carefully, recognizing that much of what transpired within the refugee camps remained invisible to white eyes.

In March 1862 New Bern became the heart of the Union occupation in eastern North Carolina and the locus for both the black and white refugee migrations. Founded in 1710, New Bern served as the colonial capital of North Carolina. With a population of 5,432 in 1860, New Bern was the second-largest city in the state, after Wilmington, and slightly larger than the capital, Raleigh. The town’s antiquity, history, and Federal architecture gave it a regal bearing, leading to its reputation as “The Athens of North Carolina.” New Bern’s antebellum economic importance and its Civil War strategic significance rested in its location at the confluence of the Neuse and Trent Rivers. Running through the center of town, the Atlantic and North Carolina Railroad linked New Bern to Morehead City on the coast and to Goldsboro in the west. On the eve of the Civil War, New Bern featured two hotels, a courthouse, several churches, an academy, and wharfs and warehouses lining the rivers.3

Despite its antebellum prosperity, the town that greeted Union soldiers on March 14, 1862, paled in comparison, as the preceding months had transformed New Bern into a shell of its former self. New Bern residents had been expecting and dreading the Union invasion for months. When rumors about a potential attack began circulating in September 1861, a few of the region’s white residents decided that refugeeing themselves to the North Carolina interior would be prudent. The vast majority, however, waited and watched for the planned invasion. A January 1862 newspaper editorial complained that invasion rumors had resulted in a “cruel and unnecessary panic now raging in our town, crushing up furniture and driving crowds of people from their homes.” Fearing that Confederate currency would become worthless in the aftermath of a Union occupation, the Bank of New Bern stopped accepting it in February 1862.4 On the evening of March 13, the day before the invasion, most of the white population nervously remained in New Bern, fearful of the immediate future.

Most New Bern residents correctly assessed that the thinly spread Confederate forces were unlikely to repulse a Union attack. Writing in her diary in late January 1862, Clarrisa Phelps Hanks, a New Bern resident, observed, “We have no naval force to meet them on water[;] they have every advantage of us in that respect and unless God fight for us we must be defeated.” In the days leading up to the expected attack, many white New Bern residents, especially women and children, fled the city, taking trains and boats bound for the interior. One resident observed that since New Bern was “in an exposed position, it was thought best for as many women and children as could leave to do so.” Despite the preinvasion exodus, however, many white New Bern residents remained in the city until it became clear that Union forces would be entering the city within hours, creating “a perfect panic and stampede, women, children, nurses, and baggage getting to the depot any way they could.” Retreating with the rest of his unit, William Curtis, a Confederate soldier from Cherokee County, came across dozens of fleeing soldiers and civilians on the road from New Bern to Kinston. “We found a perfect stampede,” he wrote. “The panic stricken crowd consisted of a heterogeneous mixture of soldiers, citizens,—men, women, children, and negroes leaving the town in the utmost confusion.” Curtis found the road littered with debris—“trunks, boxes, and household plunder”—as fleeing civilians abandoned their treasured possessions to stay ahead of the Union advance. “It was an affecting sight to see ladies, both young and old, many of whom appeared unaccustomed to hardships and toil, trudging along the road in mud and water, on foot, carrying immense loads of their household articles, perhaps those most highly prized, and with tears, beseeching for some mode of conveyance to enable them to escape from the ruthless invader.”5

This last-minute exodus of all but approximately two hundred of the town’s white residents left the streets littered with baggage and furniture that could not be loaded onto railroad cars and ferries. To deprive Union soldiers of the benefits of holding New Bern, retreating Confederate soldiers set fire to the town. One Union soldier noted that “only for the prompt efforts of the troops crossing into the city, and aid furnished by the colored people, New Berne would have been destroyed.” Refugees fleeing along the Kinston road could see their homes go up in flames. William Curtis observed that many of the refugees fleeing New Bern were wealthy young women, who “now turned their backs sadly upon homes, that a short time before were pleasant and happy, and perhaps could now, for the first time in life, cast a lingering glance back, only to be met by the lurid glare of the fiery element consuming the home. . . . Their agonizing cries of grief, and anxious entreaties for assistance, were heard on all sides, amid the din and clatter . . . and the panic stricken-rabble.”6

Shortly after their victory at New Bern, Union forces occupied the towns of Washington, Beaufort, Morehead City, and Plymouth. Together with New Bern, Roanoke, and the Outer Banks island of Hatteras (occupied by Union forces in August 1861), these towns formed the heart of the Union occupation of eastern North Carolina that would last the duration of war. As in New Bern, a significant proportion of the white population refugeed themselves inland in advance of the Union occupation. When Union soldiers marched into the town of Washington, a Northern journalist noted that “some two thirds” of Washington’s twenty-five hundred inhabitants “have seen fit to leave for the interior.” Similarly, in Plymouth, Union forces discovered that “the most rabid of the secessionists here all left the city, including all the ministers of the gospel, except the Baptist.”7

In the months to come, as Union soldiers established control over northeastern North Carolina, slaves took every available opportunity to seize their own freedom. Even before they had established firm control over the region, Union officials found themselves inundated by fugitive slaves. Indeed, in many locations, fugitive slaves occupied coastal towns after the white residents had fled and before Union soldiers marched in.8 Rev. Horace James, serving as chaplain for the Massachusetts Twenty-Fifth Volunteers, observed that when Union soldiers marched into New Bern on March 14, 1862, “one class of the population gave us a hearty welcome, viz: the negroes. They stood in lines along the street as we advanced, and showed their ivory in the most remarkable manner. . . . They seemed too happy for expression, and were actually wild with delight.” On the next day, one Massachusetts soldier noted that the “Negroes are coming in by the hundreds.” A few days later, Gen. Ambrose Burnside observed that New Bern was “overrun with fugitives from the surrounding towns and plantations.” Burnside regarded these fugitives as “a source of very great anxiety” but concluded that “it would be utterly impossible if we were so disposed to keep them outside of our lines, as they find their way to us through the woods and swamps from every side.” One of Burnside’s soldiers agreed with his assessment of the situation in New Bern, noting that “every expedition to the interior, securing a passage safe from rebel pursuit over all the space between our troops and New Berne, was the sign for great numbers [of fugitive slaves] to come in.” Burnside’s personal secretary observed in March 1862 that fugitive slaves were “stealing in from every direction by land & sea—in squads from 6 to 30 each—they come and dump themselves by the side of the fence and ‘wait for order from Mr. Burnside.’” Although she was only a small child at the time of the invasion, the slave Hattie Rogers remembered that “all who could swim the [White Oak] river [in Onslow County] and get to the Yankees were free.” Dr. R. R. Clarke of the Thirty-Sixth Massachusetts observed in April 1862 that fugitive slaves were “continually coming in, in squads from one to a dozen—wending their way through the swamps at night, avoiding pickets—they at last reach our lines.”9

Although most of the fugitive slaves arriving in New Bern came from eastern North Carolina, some black refugees had traveled much farther. According to Vincent Colyer, two runaway slaves came from northern Alabama, having spent the previous year hidden in the woods and having trekked for three months “through the woods and bye-paths, avoiding white men all the way” to New Bern, a distance of 750 miles. Two other slaves arrived in New Bern in 1862 from South Carolina, where they had fled to the woods shortly after the fall of Fort Sumter. The New York Times reported in June 1862 that one literate slave arriving in New Bern had traveled some five hundred miles to reach Union lines, having written himself passes to facilitate his journey.10

In making the decision to run to Union lines, slaves drew on decades of experience with clandestine travel. Most slaves in eastern North Carolina knew, either directly or indirectly, how to leave their plantations undetected, how to evade slave patrols, and how to navigate the woods and swamps, at least in their immediate vicinity. They used this knowledge to covertly visit friends and relatives on neighboring plantations, to seek a temporary respite from the brutality of slavery by taking refuge in the wild, and, on rare occasions, to escape slavery entirely. Born a slave in Chowan County between 1835 and 1840, Allen Parker noted that “in spite of the danger of being caught the slaves were often out nights without passes.” Parker admitted that he often left the plantation at night, usually to steal and butcher hogs, “for the night was the slaves’ holiday.” While Parker usually returned before daybreak, on one occasion he ran away for two weeks, living in the woods. In August 1862, six months after Union forces had invaded eastern North Carolina and established a permanent foothold in the state, Allen Parker met with slaves from neighboring plantations to plan their escape. After some deliberation, Parker and his associates, “finding that lots of the slaves from the neighboring plantation were running away we concluded that we would take our chance, as soon as we could get any.” After seeing a Union gunboat positioned on the Chowan River, Parker plotted with three other slaves to escape that night. Waiting until the dead of night, they eluded slave patrols, making their way to the river, where they unchained a dugout canoe and rowed to the Union gunboat.11

Many African Americans in coastal North Carolina, both free and enslaved, worked as boatmen and brought information about the broader world to slaves on plantations, including information about Union and Confederate troop movements, slave patrols, and routes to freedom. In 1862 Sutton Davis, an enslaved boatbuilder and carpenter living in Carteret County, rowed a small boat to deliver himself and his family across Jarrett Bay to the outskirts of New Bern and Union lines. In March 1862 Union soldiers from Massachusetts preparing to leave Roanoke for the impeding invasion of New Bern were confronted by a little schooner carrying twenty-four fugitive slaves. Several months later, slave families sailed into Beaufort via Bogue Sound. In August 1863 a Beaufort resident wrote in his diary that “about fifteen negroes—men, women, and children—arrived here today by sea in a small open boat, from Snead’s Ferry in Onslow County. They are fugitives in search of freedom.”12

Fugitive slaves’ determination to reach Union lines manifested itself during the siege of Washington, North Carolina. Captured by Union forces shortly after the occupation of New Bern in March 1862, Washington had served as an important Union base in Beaufort County. In March 1863 Confederate forces under Gen. D. H. Hill began a lengthy siege of the town, erecting batteries on the Pamlico River, effectively cutting the town off from resupply or reinforcement by water. Confederate brigades stationed between Chockowinity crossroads and Blount’s Creek prevented reinforcement by land, leaving the town cut off from the outside world. In the midst of the siege, seventeen fugitive slaves managed to pass through the Confederate blockade. Led by an enslaved preacher named “Big Bob,” they had traveled fifty miles the previous night, evading Confederate patrols on both land and water.13

Some fugitive slaves arriving in Union lines were experienced refugees. Union territory in northeastern North Carolina abutted the Great Dismal Swamp, a vast wilderness that straddled the border of North Carolina and Virginia. More than a thousand square miles in area, the Great Dismal Swamp had been a refuge for fugitive slaves for more than a century, sheltering one of the largest maroon communities in the United States. Although the number of fugitive slaves living in the swamp at the time of the Civil War is impossible to estimate with any degree of certainty, its population must have run into the hundreds, if not thousands. During the Burnside invasion of 1862 most Dismal Swamp refugees joined the flood of fugitive slaves converging on New Bern and other Unionheld sites. In his postaction report to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, Burnside reported in March 1862 that among the fugitive slaves arriving in New Bern were two men “who have been in the swamps for five years.” William Kinnegy, a fugitive slave who later worked as a Union scout, had lived in the swamp since February 1857. Kinnegy described the swamp as “a close jungle, so thick that you could not penetrate it, except with an axe.” During his years in the swamp, Kinnegy lived in a hut constructed from tree branches and killed cattle and hogs that grazed on the edge of the swamp. Although Kinnegy used the swamp as a refuge, he was not entirely cut off from the surrounding communities. He continued to visit his enslaved wife during brief clandestine nighttime rendezvous, occasionally traded with poor whites, and evaded slave patrols that periodically visited the swamp.14

In May 1862 a company of the Ninth New York Volunteer Regiment was assigned to patrol the Dismal Swamp Canal. Constructed in 1805, the canal ran along the eastern edge of the swamp, connecting New Bern to Norfolk. While on patrol, they were confronted by five fugitive slaves who had been living in the Dismal Swamp. One soldier remembered that they “presented themselves fearlessly and asked to be permitted to join the party. There was no hesitation or distrust. They had evidently received full information regarding the situation by that unexplained and mysterious system used for spreading information, known only to them and which no white man has yet been able to discover.” One of these five men informed the commanding officer that he had escaped in 1855 and had been living in the swamp during the seven years since.15

Free African Americans also fled to Union lines. Vincent Colyer noted that two free African Americans from Onslow County arrived in New Bern in 1862 “to escape being drafted to work on the enemy’s fortifications,” presumably at Fort Fisher near Wilmington. They had spent more than a year in the woods avoiding Confederate conscription agents and slave patrols before they successfully made their way to New Bern. Emily Pailin, a free black woman from Elizabeth City, moved to New Bern with her nine-year-old son, hoping that there would be more opportunities there, far from the threat of Confederate attack.16

Native Americans living in eastern North Carolina, most prominently the Lumbee of Robeson County, also joined the flood of refugees fleeing to Union lines. In June 1861 a trainload of white refugees from Wilmington en route to Laurinburg stopped at “a Station called Scuffletown” (now Pembroke), where they saw “a collection of [the] most singular-looking mulattoes, who inhabited that neighborhood, and had come in crowds both men and women, to see that novel sight to them, an engine with a train of cars attached.” From aboard the train, one white refugee marveled at the Lumbees’ “reddish yellow color” and “long straight black hair,” which the women wore in “long thin braids,” all of which seemed not to fit within the white refugee’s neat racial classifications. She speculated that they were of Portuguese origin but “also had Indian and negro blood in their veins.” Staring at each other as the train refueled, the Lumbees at the station and the white refugees aboard the train must have wondered at the strange places and people the war, then only a few months old, had brought into their lives.

Although the Lumbee would have preferred to sit out the war in Scuffletown, many of the forces that drove white and black North Carolinians to become refugees also impinged on the Lumbee. Like free blacks and enslaved African Americans, the Lumbee were subject to Confederate conscription. Hundreds of Lumbees were compelled to labor in the construction of Fort Fisher near Wilmington, where many died from yellow fever. To avoid conscription, many Lumbees fled to the swamps along the Lumber River. One of the white refugees on board the train to Laurinburg later commented that Lumbees “knew every hiding place in the swamps around & very exceedingly cunning, like their Indian fore-fathers, in concealing themselves.” Many Lumbees would remain in the wilds of Robeson County for the duration of the war, with some participating in guerrilla warfare against Confederate forces, culminating in the Lowry War, a conflict between the Lumbee and local whites that lasted well into Reconstruction. Although most Lumbees remained in Robeson County, at least some Lumbees made their way to Union-occupied territory. Mary Barbour, a runaway slave who had escaped with her parents from McDowell County, lived in the refugee camp on Roanoke Island, where she remembered that the residents included an “ole Indian Witch ’oman.” Some of the refugees whom white Union soldiers classified as mulattoes may have been Lumbees.17

Most of the earliest slaves to flee to Union lines were young men. Enslaved men in their teens and twenties had always been the most likely to run away prior to the Civil War. Fugitive slave ads suggest that four out of every five runaway slaves were male and a similar proportion were described as young, between the ages of thirteen and twenty-nine. In Civil War North Carolina this propensity for young men to run away was exacerbated, as young men were the most likely to be removed by their owners to the interior, in large measure because they were the most liable to run away and because they were the most valuable slaves. Furthermore, slave women may have been frightened by the prospect of entering a military camp, home to hundreds of soldiers and potentially dangerous places for women and children.18

Having made their way within Union lines, some refugee men returned to Confederate territory to help their families escape. In February 1862 a group of black men on Roanoke Island left the protection of the Union army to return to the mainland. They explained to a disingenuous Union officer that “We’se wives and chillern in slavery. We can’t leave them. Bress de Lord, de day ob jubilee is come. We’se all to be free now. We must go back and get our wives and chillern.” As the number of fugitive slaves entering Union lines grew, so too did the demographic diversity of the refugee slave population. After the initial wave, the vast majority of fugitives arrived in family groups, including very young children, the elderly, and the disabled. Two weeks after the battle of New Bern, one Massachusetts soldier noted that “there are swarms of negroes here. They are of all sexes, ages, sizes and conditions.” On Roanoke Island, the refugee population included many infants and an elderly slave who claimed to be 102 years old. In New Bern, Massachusetts soldier Henry Clapp met several fugitive slaves who claimed to remember the Revolution, including one who said she was 107 years old. In December 1862 a Beaufort resident claimed that the “town is crowded with runaway negroes. Not only the able bodied, but the lame, the halt, the blind and crazy.” A Massachusetts soldier noted that “the contrabands in our vicinity of all ages, sizes and colors, and of both sexes, paid us daily visits in great numbers.”19

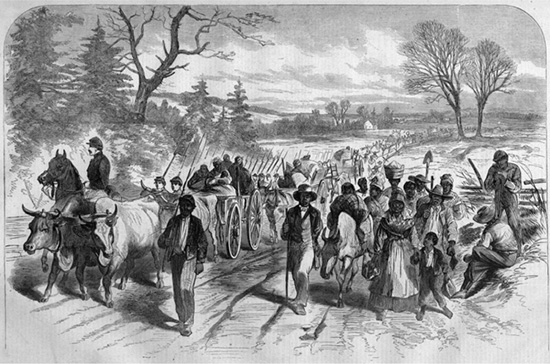

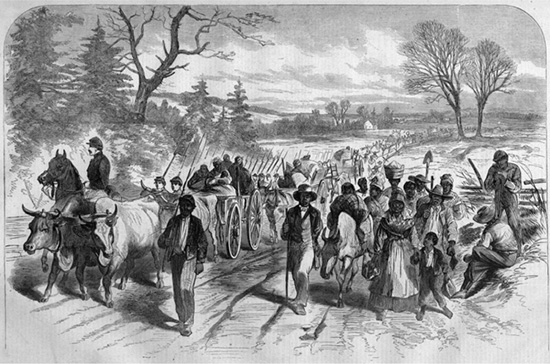

Every Union expedition into Confederate territory brought more refugee slaves into Union lines. In June 1862 a Union scouting party along the Neuse River encountered four slave women on the Latham plantation who asked if “they might go with us to Newbern.” They knew that the presence of Union soldiers meant safe passage to freedom. When the women departed with the Union soldiers, Mrs. Latham “came running down the lawn, shouting after them at the top of her voice, ‘Here, Kitty, Peggy, Rosa, Dinah, where are you going with those horrid men? Come back here right this minute!’ The women, looking back over their shoulders and showing immense rows of ivory, replied to her, ‘Goo-bye, missus, goo-bye! spec we’es gwine ober to Newbern.’” Later that summer, as the unit marched through Martin County, a soldier observed that “the contrabands flocked in droves to our standard.” At the end of their expedition, he claimed that among their spoils were “upwards of 1000 negroes.” Similarly, a Massachusetts soldier noted that after one scouting expedition in late 1862 “Negroes by the hundreds followed us into Plymouth.” In December 1862 another Massachusetts soldier noted that “one of the unlooked-for results of the expedition was the bringing back with the soldiers a large number of ex-slaves, who, putting their entire possessions in a bundle, larger or smaller, as the case might be, added themselves to the column, and to the number of 500 or more came into Newbern with the army.” On a mission in early 1863, “negroes by hundreds followed us on our return march to Winton, with little bundles tied up and swung on sticks over their shoulders, shouting ‘We’s gwine to liberty, hi-yah, gwine to liberty!’ The negroes would stop work in the fields, gaze at the Yankee column a few minutes, drop hoe or axe, and fling up their old hats and shout ‘Gwine to liberty.’” In November 1862 a Massachusetts soldier noted that “a day or two after our return from the mudmarch to Trenton, some of the results of that raid came straggling through our camp, a hundred or more contrabands, escaped from slavery.” Sometimes the column of black refugees following Union soldiers into camp resembled a parade. One soldier observed that “another feature of the return march is a procession of ‘contrabands,’ men, women, and children, in [the] strangest medley of rags, but with a kind of earnest and solemn joy on their faces, that make them look sublime. . . . They followed the flag and saw its bright folds streaming over them, red with the flames of their morning, Freedom’s star leading them on.”20

Not all slaves encountered by Union soldiers during their ventures into the interior accompanied them on their return to New Bern. One elderly slave in Trenton told Massachusetts soldiers that his owner had gone “up country.” When they asked him if he would return with them, he “said he wanted his freedom, but he wanted to go ‘clar,’ meaning that he wanted to take his whole family with him, four of his children were at home, but he had five still in slavery.” Presumably, these five enslaved children had been removed by their owner during his retreat “up country.” At other times, Union soldiers saw slaves who desired to secure their freedom but refused to help them. One Massachusetts soldier on a Union gunboat en route to New Bern witnessed “some 40 or 50 negroes came running down to the shore and begged to be taken aboard.” Although his unit had recently liberated “upwards of 1000 negroes,” they had no room aboard ship for these additional passengers. Describing them as “the most forlorn and wretched looking beings I had ever seen,” clothed in “little else than rags, scarcely covering their nakedness,” the Massachusetts soldier watched them as they followed the boat downriver for nearly a mile, “begging piteously to be taken aboard.”21

Slave owners in eastern North Carolina tried to dissuade their slaves from running away. One black refugee indicated that his owner had told him “that the yankees will harness them to their carts & if they don’t draw they will bayonet them—that they will sell them in Cuba.” The slave evidently saw through the lie, claiming, “I said yes sir at the same time I was making preparations to leave him. . . . I Knowed that you [the Union soldiers] was our friends because they told such stories about you.” Slaves inherently distrusted what their owners told them. After being told the horrors that awaited them among Union soldiers, one fugitive slave revealed, “We knowed dey lied—we’d be praying to de Lord dat you Yankees might come.” After the occupation of New Bern, a Massachusetts soldier observed that “the slaves did not appear to be afraid of the [Union] soldiers, although they had been taught to fear us.”22

Not all slaves who fled the plantation for Union lines reached their destination. Slaveholders in eastern North Carolina increased slave patrols starting in 1861 in an effort to dissuade slaves from running away and to capture them if they did. Slave patrols worked in conjunction with the Home Guard and the Confederate army in eastern North Carolina to monitor slaves, creating a powerful disincentive for slaves contemplating escape. According to one North Carolina slaveholder, increased patrols in Duplin County had been “of great service in preventing the escape of slaves.” A corps of twenty patrollers had been hired, accompanied by hounds (“at heavy cost”), as “we are not distant from Yankee lines.”23

In their efforts to prevent the exodus of slaves to Federal-controlled territory, slaveholders authorized patrollers to use lethal violence. In contrast to antebellum practice, which emphasized capturing runaway slaves unharmed, wartime slave patrols and Confederate pickets adopted a more militant approach. When Amos Homans, a slave on Riley Murray’s plantation in Hyde County, fled towards New Bern in 1862, he was mercilessly pursued by Confederate soldiers, who shot him in both legs before capturing him. Planters also authorized overseers to use lethal violence to prevent slaves from running away. An overseer reported in September 1862 that “I had a dificulty withe old Pompey . . . heay broke and run [so] I shot him withe my pistol.”24

Maps of the Burnside invasion of eastern North Carolina, including those produced by the army during the war, often overstated the extent of Union control in the region. In truth, Union authority fell over only a handful of coastal towns, such as New Bern, Beaufort, and Morehead City, and the sandy Outer Banks islands. While Union boats patrolled the coast and made regular sorties upriver, and scouting missions frequently probed the interior, the territory safely under Union control stopped somewhere short of the picket lines established around each town. All of the land beyond the picket lines was effectively a no-man’s land, under neither Union nor Confederate control. The territory where black and white refugees could find protection under the Union army, therefore, was small. Like midday shadows, refugees in eastern North Carolina stuck close to fortified Union enclaves. According to one relief worker, “We control, indeed, a broad area of navigable waters, . . . but have scarcely room enough on land to spread our tents upon.”25

Much of this no-man’s land between Union and Confederate lines quickly became depopulated by a mass exodus, as pro-Confederate whites removed themselves and their slaves west to the interior and fugitive slaves and Unionist whites fled eastward. One Union soldier described this region where “wide fields remained uncultivated, and in not a few cases ripened crops were left to perish unharvested. Vast barns and granaries were left entirely empty. On the most extensive plantations but few signs of life were visible. A few aged negroes, too old to run away and too valueless to be removed, were loitering about, bewildered by the sudden and inexplicable change.”26

Approaching Union lines could also be fatal for fugitive slaves. Expecting a Confederate attack, Union soldiers on picket duty often mistook refugee slaves for Confederate soldiers. A New York soldier stationed on Roanoke Island in 1862 described the danger that fugitive slaves faced when approaching the island:

Nearly every night one or more boat-loads of slaves landed on the beach and were taken in charge by the guard. This was an extremely dangerous proceeding for escaping slaves, and would have been considered heroic bravery had they been white men. No sooner had the danger of pursuit and capture by wrathful owners abated, and the peril of the watery journey been overcome, than a new danger, demanding the greatest caution, presented itself. They were obliged to approach a strange shore in the darkness of night, where the sentinels were keenly alert for the approach of an enemy, especially by water. The flapping of sails or the sound of oars from the water was naturally accepted by the picket guard to denote an attempted night attack and surprise, and their faculties were doubly keen, and they were ready to at once fire in the direction of the sound. . . . In their efforts to gain their freedom they had risked death at the hands of the very men from whom they sought protection.

In April 1862 a half dozen runaway slaves approaching New Bern were surprised by a picket, who fired on them, the bullet “wizzing by old darkie’s head.” The frightened refugees were spared a second shot when they called out and the pickets recognized their distinctive accent.27

Rowland Hall, a Union officer stationed in New Bern, wrote to his father in May 1863 that “a poor negro was shot dead in the middle of the night by our picquets [sic].” The next day another fugitive slave arrived in camp, who revealed that the two men had escaped from Danville, Virginia, three weeks earlier. They had trekked more than two hundred miles, evading slave patrols and Confederate soldiers and living in the woods. “They knew not where they were, only knew that they were seeking our lines. They had nothing to eat in three days, not one mouthful of any kind,” Hall wrote. “The survivor was naked except the remains of a pair of cotton drawers, torn with briers, bleeding all over, emaciated, haggard, such an object as you have no idea of. No wolf ever looked more frightful.”28

The Burnside expedition of March 1862 occurred against the backdrop of evolving federal policy on fugitive slaves. In May 1861 Gen. Benjamin F. Butler, stationed at Fort Monroe, Virginia, argued that the use of slave labor by the Confederacy transformed slaves from private property to implements of war, and he could therefore prohibit the return of refugee slaves on the grounds that they were “contrabands of war.” In August 1861 the First Confiscation Act made Butler’s reasoning into national policy, authorizing the confiscation of all property used in support of the rebellion. As historian James Oakes has recently observed, in theory, the First Confiscation Act freed only those slaves used in the Confederate war effort, but in practice, the act effectively emancipated all slaves entering Union lines from disloyal states. On March 13, 1862, the day before Burnside’s attack on New Bern, Congress enacted legislation prohibiting Union soldiers from returning fugitive slaves to their owners, effectively repealing one of the key provisions of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850.29

In authorizing the assault on North Carolina, General-in-Chief George McClellan advised Burnside to avoid linking the invasion to emancipation. A vocal critic of the recent changes in federal policy, McClellan wrote to Burnside that “I would urge great caution in regard to proclamation . . . say as little as possible about politics or the negro. Merely state that the true issue for which we are fighting is the preservation of the Union and upholding the laws of the General Government, and stating that all who conduct themselves properly will as far as possible be protected in their persons and property.” Unwilling to disobey a directive from his military superior, Ambrose Burnside ordered his men to “protect the persons and property of the loyal and peaceable citizens of this State,” and in a February 1862 “Proclamation made to the People of North Carolina” indicated that he had no intention “to interfere with your laws constitutionally established, your institutions of any kind whatever, your property of any sort, or your usages in any respect.” Furthermore, he assured them that rumors that he intended to “liberate your slaves” were “not only ridiculous, but utterly and willfully false.”30

Although Burnside pledged not to interfere with slavery, his actions immediately after the invasion indicate the opposite. Shortly after the occupation of New Bern, Burnside wrote to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton that “in the absence of definite instructions upon the subject of fugitive slaves,” he had adopted a policy to “allow all slave who come to my lines to enter” and “to give them employment as far as possible, and to exercise toward old and young a judicious charity.” He also pledged to “deliver none to their owners under any circumstance.”31 As James Oakes has recently observed, Burnside’s actions mirror the decisions made only a few months earlier by Gen. Thomas W. Sherman in the Sea Islands. Both generals issued conservative proclamations about their intentions regarding slavery prior to invasion, only to pursue a more liberal track afterward. Cognizant of the shifting federal policy on black refugees, Burnside followed the model established by Butler in Virginia and Sherman in South Carolina and outlined in the First Confiscation Act. He allowed fugitive slaves to enter Union lines, refused to return them to their former owners, and authorized their employment as manual laborers.

Like Butler, Burnside saw fugitive slaves largely in terms of the labor they could perform for the Union army. Col. Rush C. Hawkins of the Ninth New York, whom Burnside had left in command of Roanoke Island before the invasion of New Bern, arranged for fugitive slaves to work as cooks, laundresses, teamsters, woodcutters, and porters. By mid-March 1862, Hawkins informed General Burnside that 130 former slaves were now working on Roanoke Island, building a storehouse and, when proper tools arrived, a wharf. Hawkins also outlined a payment schema for fugitive slaves working for the Union army—men would receive ten dollars per month plus rations and “a soldier’s allowance of clothing,” while women would receive four dollars per month plus rations and an “allowance of money equal to an[d] in lieu of a soldier’s allowance of clothing.” In addition to providing for wages for fugitive slaves in the employ of the army, Hawkins’s General Order No. 2 also created a broader framework for free labor on Roanoke, mandating that fugitive slaves privately employed would receive at minimum the same wages and benefits afforded to those working for the army. Hawkins’s General Order No. 2 marked the birth of free labor in North Carolina, but it also marked a turning point in the relationship between the black family and the federal government. It authorized black children under the age of twelve to also receive a ration and specified that they would “remain with their parents,” providing one of the earliest legal claims that black parents had for their children. Unlike their parents, these black refugee children were not expected to work for their rations. Hawkins concluded that “in all cases they [fugitive slaves] will be treated with great care and humanity. It is to be hope[d] that their helpless and dependent condition will protect them against injustice and imposition.” In effect, Hawkins situated the army and the government as the fugitive slaves’ protectors. While he had neither the power nor the authority to emancipate the fugitive slaves on Roanoke Island, General Order No. 2 effectively created a framework for de facto emancipation and free labor.32

Neither Burnside nor Hawkins saw himself as an abolitionist or the emancipation of black refugees as a critical aspect of their mission in North Carolina. Nonetheless, the presence of the U.S. army under their command quickly and dramatically undermined slavery in eastern North Carolina. By May 1862, William H. Doherty, an Irish-born college professor who had established a school in New Bern, claimed in a letter to President Lincoln that “it is sufficiently evident to every unprejudiced man dwelling in or visiting the South, that the victories of the U.S. troops, & the occupation of the country by Northern armies, have, unintentionally perhaps, but necessarily, overthrown the whole fabric of society, founded as it was, on the Institution of Negro Slavery.” From what Doherty could see on the ground in New Bern, the Burnside invasion had almost instantaneously ended slavery within the occupied portion of North Carolina. The social changes brought about by military emancipation, according to Doherty, were permanent, as “it is perfectly futile to hope, that the slaves now practically emancipated, will ever return to their former condition, or that they can be forced, any longer, to labor for their former owners.” What remained unclear, however, was how black refugees, “now practically emancipated,” would rebuild their lives in Union-occupied North Carolina.33

By the end of March 1862, Burnside reported to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton that “the negroes continue to come in [to New Bern] and I am employing them to the best possible advantage.”34 Fearing that the influx of fugitive slaves would overwhelm his time and resources, Burnside appointed Vincent Colyer as the superintendent of the poor on March 30, 1862, to coordinate fugitive slave policy in eastern North Carolina. Born in Bloomington, New York, in 1825, Colyer had studied painting at the National Academy in New York City. A devoted Quaker, Colyer had involved himself in a number of philanthropic organizations, especially the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA). Starting in April 1861, Colyer spent three months visiting military encampments around New York, holding “meetings for prayer, singing, and exhortation, distributing tracts, Testaments, [and] hymn-books.” After the battle of Bull Run in July 1861, Colyer traveled to Washington to tend to soldiers in hospitals and assist chaplains in camps. Working tirelessly among soldiers in Washington for six months, Colyer saw the need for a more orchestrated civilian relief effort. Corresponding with other YMCA workers, Colyer became one of the founding leaders of the U.S. Christian Commission, an organization formally established in November 1861.35

After the formation of the Christian Commission, Colyer decided to eschew a leadership position in the organization in favor of continuing his relief work in the field. In February 1862 he attached himself to Burnside’s expedition as a civilian representative of the Christian Commission, where he assisted the regimental chaplain in tending to the sick and wounded after the battle of Roanoke Island. Soon thereafter a boatload of refugee slaves arrived in Roanoke, about which Colyer later wrote, “Commenced my work with the freed people of color, in North Carolina.” In March 1862 Colyer accompanied Burnside’s soldiers during the invasion of New Bern.36

Colyer’s appointment created an uneasy partnership between civilian relief workers and military officers that would last for the duration of the war. Colyer and other relief workers felt their mission in North Carolina was primarily to care for the spiritual and physical needs of soldiers and civilians in a combat zone. “Gen. Burnside,” Colyer wrote, was “by no means an abolitionist.” Instead, from Colyer’s perspective, Burnside saw fugitive African Americans primarily as a source of potential labor. The first order that Colyer received from Burnside was to “employ as many negro men as I could . . . to work on the building of forts.” Burnside authorized Colyer to recruit as many as five thousand African American men, offering them eight dollars per month, along with “one ration and clothes.”37 Left to his own devices, Colyer probably would have prioritized his time differently.

Under Vincent Colyer’s supervision, refugee slaves were put to work during the spring and early summer of 1862 building fortifications at New Bern, Roanoke, and Washington. He also organized refugees to work as stevedores and as manual laborers in the Quartermaster, Commissary, and Ordinance Offices. Skilled black refugees were put to work as carpenters, blacksmiths, and coopers, building wooden hospital cots, a railroad bridge across the Trent River in New Bern, and docks on Roanoke Island. One Union soldier noted in April 1862, one month after the occupation of New Bern, that over seven hundred fugitive slaves had arrived in town, eager to work in whatever capacity would support the Union cause. “They all find employment,” he wrote. “Some work on fortifications, some unloading ships.”38

Vincent Colyer also supervised a volunteer corps of more than fifty fugitive slaves who worked as spies, scouts, and guides in 1862. Prohibited from officially enlisting in the Union army, fugitive slaves volunteered in these extra-military roles. According to Colyer, these spies “frequently went from thirty to three hundred miles within the enemy lines; visiting his principal camps and most important posts, and bringing us back important and reliable information.” Reporting on Confederate forces in Kinston, Goldsboro, Trenton, Onslow, Swansboro, and Tarboro, fugitive slaves became the eyes and ears of the Union army. Colyer was repeatedly impressed by their bravery. One scout, a teenager named Charley, made three separate trips from New Bern to Kinston, a distance of forty-five miles, most of it in Confederate hands. Home to Fort Campbell and Fort Johnston, Kinston had the largest concentration of Confederate soldiers in eastern North Carolina, with approximately four thousand men under arms. During his third expedition, Charley, this time accompanied by another fugitive slave turned spy, was nearly captured by a Confederate sentry on horseback who was tracking them with bloodhounds. Hiding in the woods, they managed to ambush the sentry, shooting his horse and two of the dogs with revolvers. To evade capture, the two young men split up, taking to swamps and woods while Confederate scouts took chase. Over a thirty-six-mile sojourn, they “came home as fast as they could run, throwing off coats, pants, caps, and everything but their shirts, drawers, and revolvers, finally reaching our lines in safety, completely exhausted.” Simon H. Mix, a soldier with the Second New York Cavalry, claimed that white Union soldiers relied heavily on the local knowledge that black scouts provided, noting that “in all our expeditions in North Carolina we have depended upon the negroes for our guides, for without them we could not have moved with any safety.”39

Refugee slaves working as spies and scouts risked their lives not only to aid the Union war effort but also, and probably primarily, to rescue family members still enslaved. Shortly after his arrival in New Bern, William Kinnegy heard, presumably from other refugee slaves, that “my wife’s owner has run away, and she and the children are up in the country alone.” He asked Vincent Colyer for a pass to bring them to New Bern. Colyer told Kinnegy that he would pay Kinnegy if he would, “while after his wife, . . . go a little further, up to Kingston and thereabout, and take a good look at the rebel encampments, make a careful note on his memory of their number and situation, inquire of the negroes in their cabins all about the enemy, and bring this information, with his wife and children on his return.”40

Union officers ignored the advice proffered by fugitive slaves at their peril. In 1862 the fugitive slave William Henry Singleton was called into General Burnside’s headquarters in New Bern in preparation for the Union assault on Wise Forks (which Singleton referred to as “Wives Forks”), near Kinston. Singleton recalled that “I laid the route out for them the best I knew how, but said that if I were going to command the expedition I would give them a flank movement by way of the Trent river, which was five miles farther from Wives Forks than the Neuse river.” General Burnside, however, did not heed Singleton’s advice, “with the result that they were repulsed.”41

Confederate North Carolinians, slaveholding and nonslaveholding alike, were amazed and horrified at the number of slaves escaping to Union lines. In March 1862 Pvt. William Loftin wrote to his mother that “a good many negroes are running away and are going to the Yankees everyday. All of mine are going to them. From the oldest to the youngest left as soon as they herd [sic] that New Bern had fallen.” Living in Union-occupied Beaufort, Confederate sympathizer and slave owner James Rumley had a firsthand perspective on the influx of black refugees into Union lines. In May 1862 Rumley wrote in his diary that “slaves are now deserting in scores from all the parts of the country, and our worst fears on this subject are likely to be realized.” Stationed in Goldsboro, Confederate general Thomas Clingman wrote to D. H. Hill in August 1862 that “negroes are escaping rapidly, probably a million dollars’ worth weekly in all.” In December 1863 overseer Henry Jones wrote to planter John R. Donnell that “something like 100 [slaves had] gone off in past month,” including 35 in a single night.42

For Union soldiers who had only experienced slavery in the abstract, the arrival of hundreds of refugee slaves challenged their ideas about race and slavery. Coming primarily from Massachusetts and New York, most of the soldiers on the Burnside expedition knew slavery only through reading Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin or through newspaper accounts. One Massachusetts soldier noted in April 1862 that although he had “always been a very stiff advocate for southern rights,” his experience with fugitive slaves in New Bern had transformed his view of slavery, such that “I have become so far ‘educated up,’” that now there was only a “little strip of land between Charles Sumner’s views and mine.” His understanding of slavery was galvanized by a conversation with a five-year-old fugitive boy. He had asked the boy why he and his family had fled slavery, “not thinking that the little fellow could realize anything.” To the soldier’s surprise, the boy quickly responded, “Kase I don’t want to be a slave—I’se want to be free.”43

Even those soldiers who had considered themselves abolitionists were transformed by the sight of fugitive slaves. Speaking at the New England Anti-Slavery Convention, Lt. Thomas Earle of the Twenty-Fifth Massachusetts revealed that he “had listened from his boyhood to anti-slavery lectures but only after his enlistment as a private in this war had he realized what it was to be an antislavery man.” His regiment’s experience with fugitive slaves had “abolitionized the young men.” Some of the soldiers had “been proslavery from Worcester [Massachusetts] to Hatteras, but their eyes were opened on that island.” Henry Clapp, also from Massachusetts, wrote to his family in February 1863 that the sight of refugee slaves who “flocked into Plymouth . . . to the tune of two hundred or so” moved him. He noted that, time permitting, he was “going to let myself out on the subject of emancipation and the negro-race. I feel strongly enough on the subjects and am much more decided in my anti-slavery ideas that I ever was before.”44

Although their experiences with fugitive slaves caused many soldiers to reconsider their views on slavery, they did not erase Union soldiers’ ideas about black racial inferiority. James Emmerton of the Twenty-Third Massachusetts claimed that fugitive slaves’ “mental development was, as a rule, in direct ratio to the proportion of white blood.” However, he was surprised to see that the slaves were more civilized and less savage than he had expected, such that “the brutishness of the black field-hand of the Gulf States was rare in our part of North Carolina.” A New York soldier claimed that the “negroes hardly appear like human beings. You would be surprised to see such uncouth ragged miserable savages landed direct from the coast of Africa.”45

Many Northern soldiers marveled at black refugees’ appearance. A Massachusetts soldier stationed in New Bern observed that “we no longer wondered where the minstrels at the north procured their absurd costumes; here was material for an endless variety. It was better than any play simply to walk about and examine the different styles of dress.” Expecting slaves to embody the traits seen in minstrel shows, soldiers often demanded that black refugees dance and sing for them. A Massachusetts soldier recalled that when his regiment arrived in Washington, North Carolina, in 1862, “squads were sent out to pick up negroes and bring them to the quarters, where they were made to show their agility in dancing.” Not all refugee slaves were willing to play along. One demurred, claiming that he was unable to dance because “I’se got de rheumatiz,” only to be told by the soldiers to “never mind, you must dance.” Another fugitive slave refused to dance on religious grounds, while a third “was brought in, struggling violently with the soldiers . . . then making a sudden spring he broke through the crowd and ran like a deer.” The abusive treatment that black refugees faced at the hands of white Union soldiers revealed not only the racist attitudes that most Union soldiers held but also how piecemeal the transition was from slavery to freedom in refugee camps.46

Fugitive slaves were not the only refugees to seek asylum behind Union lines. White Unionists by the thousands also fled to Union encampments in coastal North Carolina, creating a second distinct refugee population in the shadow of the federal army. In late 1862 a Massachusetts soldier observed the twin streams of refugees flowing into Union lines: “Many people came into Plymouth while we were there, coming down the river in dugouts. . . . These people were both whites and blacks, and were seeking protection under the starry flag.” While the motivation to attain freedom within Union lines united African American refugees in eastern North Carolina, white refugees who sought asylum did so for a variety of reasons. As Barton Myers has recently argued, North Carolina’s Unionists were a heterogeneous lot that incorporated a spectrum of political opinions. Their number included unconditional Unionists, whose support for the federal government remained unwavering during the secession crisis and afterward, but also many white Southerners who grew dissatisfied with Confederate policies, especially conscription. The first wave of white Unionists to arrive as refugees in eastern North Carolina consisted primarily of the former variety, committed Unionists who had never supported the Confederacy. In February 1862, shortly after the battle of Roanoke Island, eight white men arrived via boat on the island. Their spokesman, a well-dressed, gray-haired gentleman, saluted the Union flag, proclaiming that “we come to you as citizens of North Carolina, and, in the name of God, in the name of the Constitution to which we are loyal, we claim protection of that flag.” With a cheer from the surrounding soldiers, the commanding officer granted them refuge. A Massachusetts soldier stationed in Plymouth observed that “refugees kept coming down the river, some from a distance of fifty miles, in their dugouts. Some of these boats were quite large; one, I remember, contained three men, three women and six children, with all their household effects. Most of these people were going to New Berne, having been driven from their homes on account of their Union sentiments.”47

The second wave of white refugees to arrive in Union-occupied eastern North Carolina were distinguished less by their embrace of a Union identity than by their rejection of Confederate conscription. The institution of the Confederate draft in April 1862 pushed many reluctant Confederates to pass into Union lines, some alone, others bringing their families with them. In September 1862 Bertie County planter and Confederate John Pool worried that “the attempted execution of the [military conscription] law has driven many [men] of not very reliable character to the enemy at Plymouth.” Because the 1862 draft exempted planters, many nonslaveholding whites in eastern North Carolina became disaffected with the Confederate war effort and sought refuge in federally occupied towns. Pool pleaded with Confederate officials to exempt the county from conscription because “any further attempt at executing the law . . . would run recruits to the enemy.” Pool’s statement reveals the growing distrust between affluent and poor white North Carolinians in the eastern coastal plain. In February 1862 Washington County planter Charles Pettigrew argued that “the low whites are not to be trusted at all. They would betray or murder any gentleman.”48

Other white refugees, seeking to avoid being caught in the no-man’s land between Confederate and Union armies, acted pragmatically, assuming that they would be safer in Union-held territory. As noted earlier, much of the land between Union-occupied New Bern and Confederate-occupied Goldsboro became deserted, and many of its few remaining residents experienced significant hardships. A Massachusetts soldier noted that after the Union occupation of Kinston in December 1862, “many of the poorer class came rambling through the Union camp, begging bread of the soldiers, and eagerly picking up the fragments which our surfeited troops had thrown away.” Still other white refugees saw the war as an opportunity to escape a bad situation. For instance, in September 1861 two white apprentices fled to Hatteras Island, then the only Federally occupied territory in North Carolina, in order to escape their indenture to a planter on Roanoke Island. Like black refugees, they provided valuable military information about Confederate troop strength that paved the way for the upcoming invasion.49

Some white refugees did not linger long within Union lines but proceeded on to the North. Teacher William Eddins told a Union provost marshal in Newport that he “came in these lines because I became tired of being hemmed in so narrowly in rebeldom. . . . I wish to go North, to go into business.”50 In February 1864, fourteen refugee Quakers from Guilford County in central North Carolina arrived in New York City. They had successfully avoided conscription because of a religious exemption, until 1864, when they were ordered to join the Confederate ranks. Hiding in the woods during the day and traveling at night, they managed to make their way to New Bern, two hundred miles distant, “where they were joined by other escaped conscripts and some negroes.” Not lingering in New Bern, they boarded a ship bound for New York.51 The vast majority of white refugees, however, remained in eastern North Carolina. Longing to return home, they had no inclination to go elsewhere. Further, most white refugees could not afford the passage to New York or Boston and had no social connections there.

Union soldiers presumed that white civilians were secessionists unless they demonstrated otherwise. Whereas African American refugees were generally assumed to be dedicated to the Union cause, white refugees arriving in Union lines were not given the benefit of the doubt, and the association in the minds of many Federal soldiers between white Southerners and the Confederacy made them inherently suspect. White refugees, therefore, had to regularly prove their Unionist bona fides. While African American refugees usually received only a cursory examination upon their arrival in New Bern, Washington, Beaufort, or other Union-occupied towns, white refugees bore much more close examination.

The passport system reflected some of the significant differences in the Union treatment of white and black refugees in eastern North Carolina. According to one Union soldier in New Bern, “All civilians were obliged to prove identity before the provost-marshall, and no one allowed to move about the city without a pass, except officers in uniform and the colored people.” The soldier noted that “there was not the least demonstration of loyalty or Union sentiment with the whites, but a sullen moroseness, indicative of intense disloyalty.” For black refugees, a passport system that required whites to carry documents to travel while permitting blacks to move freely without documentation marked a significant role reversal, as slaves traditionally had to carry passes issued by their owners in order to travel beyond their plantation. A black refugee in New Bern told a Union soldier, “‘Bress de Lord an Massa Lincoln! Hallelujer! Dat dis yer ole nigger should lib to see dis happy time, when white folks mus hab a pass to go bout, and dis nigger wid the officer can go whar him pleas widout one! Bress de Lord!” Conversely, white refugees bristled at the passport system, believing that it effectively demarked them as slaves.52

Even after admission into Union lines, white refugees remained a suspect commodity. One Massachusetts soldier in New Bern noted in the fall of 1862 that “all the white hereabouts are of doubtful loyalty and have to be watched all the time.” Another Massachusetts solider noted that “many white residents, professedly Union, are believed to be playing possum.” Even sympathetic Union soldiers regarded white refugees with suspicion. Giles Ward, a first lieutenant in the Twelfth New York Cavalry Regiment, remarked in a letter home that “I know the truth of the reports of famine among them; day after day, men, women, and children come to our lines to get into New-Bern to buy bread, and beg to be allowed to enter the lines; the women weeping and children crying for food.” Although he sympathized with their plight, Ward approved of severe restrictions on white refugees, as “many of them are spies, and we can not sacrifice our cause to alleviate the suffering.” Some Union soldiers believed that as many as two-thirds of the “men that passes our lines were rebs with citizens’ clothes.”53

Union soldiers’ fear of espionage by white refugees was not unwarranted. Several white refugees in New Bern passed information and goods to Confederate scouts stationed outside of the town. Probably the best known of the Confederate spies in Union-occupied North Carolina was Emmeline Pigott. Born to a prosperous coastal family, Pigott had fled New Bern in 1862 aboard the final train to leave the town after the invasion. After working for several months as a nurse in Kinston, tending to wounded Confederate soldiers, Pigott relocated to Concord, a town in Cabarrus County just north of Charlotte. While in Concord, Pigott learned of the death of her beau at Gettysburg and rededicated her commitment to the Confederate cause. According to a memorial recorded after her death, Pigott befriended a “Mrs. Brent,” the widow of a Union chaplain, in Concord. Traveling together, the two women moved from Concord to Union-occupied Morehead City by “means of ox carts, on foot and rail, back to the little farm on Calico Creek.” Pigott’s choice of traveling companion probably eased her entry into Union territory, as did her youthful, innocent-looking visage. Once within the Federal zone, Pigott quickly developed a smuggling and intelligence network in New Bern, Morehead City, and Beaufort, gathering information from fishermen about the comings and goings of Federal vessels. According to her diary, Pigott “often met the Confederate scouts & often carried the scouts their meals in the woods. They had places to hide. Some times Yankeys would be in the house while the Confederates were both fed from the same table.” Like many female smugglers, Pigott concealed her wares beneath her voluminous hoopskirts. When she was arrested in February 1865, Pigott’s hoops bore dozens of items intended for Confederate soldiers, including boots, shirts, gloves, candy, and “several letters addressed to rebels denouncing the federals . . . and giving information about supposed movement of federal troops.”54

Pigott was not alone in smuggling goods and intelligence to Confederate scouts. In New Bern alone, at least five women actively participated as Confederate couriers. Throughout their occupation of coastal North Carolina, Union officials suspected that white refugees were smuggling across the lines but struggled to apprehend those responsible. Not only did fears of espionage temper much of the sympathy that Union soldiers might have felt for poor refugees, but many white refugees proudly displayed their Confederate sympathies. While white men risked arrest if they exhibited any pro-Confederate feeling, white women felt empowered to vocalize their support for the Confederate cause. Dr. William Smith, a surgeon in the Eighty-Fifth New York Volunteer Infantry, arranged to board at a house in New Bern and observed that “my hostess & her fair daughter are intensely ‘secesh’—they set a good table, however, and are courteous and kind. . . . Mrs. Allen, with whom I board, is an elderly lady with very motherly ways, except when her Rebel proclivities are displayed. She has a very pretty daughter of some 20 years, ‘Miss Susie,’ who is very charming, so long as the ‘secesh’ in her is not roused. She has one or two brothers in the service of the Rebellion.”55

Union soldiers generally had a low opinion of white North Carolinians. One Massachusetts soldier observed, “We saw some of the native whites here, ‘the poor white trash.’ . . . They all, as far as I have seen them, look inferior to the negroes, in intelligence, energy, and everything else that makes up a noble character. They are horribly sallow, pale, and all have the shakes. The women are frightful and are chewers of clay and snuff-dippers.” The habit of snuff-dipping among white refugee women disgusted many Union soldiers, who frequently commented on it in their letters home. One Massachusetts soldier described his revulsion with white North Carolina women, noting that

most of the females were so coarse and unfeminine in habits, as to degrade their sex. The leaded eye, sallow skin, swaggering gait and uncouth slang were too much for the Northern man, and made him devoutly thankful he descended from a nobler lineage. A lady’s evening call (they never speak of afternoon) would be incomplete without snuff, and to omit to offer it to a caller was unpardonable. After the seating of the guests, the hostess was expected to pass saucers, twigs, and a bladder of snuff, with which the visitors regaled themselves during the call. Some were so addicted to the habit of snuff-dipping, as to indulge in it upon the streets, regardless of their disgusting appearance.

Refugee men also received the soldiers’ scorn. A Massachusetts soldier noted that “the alleged loyal North Carolinians, whom the soldiers denominate ‘buffaloes,’ do not stand very high in the minds of the men from Massachusetts. Seemingly they are more observant of calls for rations than for work of any kind.”56

During the summer of 1862, Vincent Colyer grew concerned about the emergent humanitarian crisis among white and black refugees within Union lines. Most African Americans fled to Union lines with few material possessions. For fugitive slaves whose flight had required hiding in the woods or swamps, their clothes were often reduced to rags. According to Colyer, slaves entering Union lines at New Bern “were immediately provided with food and hot coffee, which they relished highly for they were usually both hungry and tired from their oftentimes long journeys and fastings.”57 While Colyer could provide this modest repast when fugitives entered camp, he had neither the resources nor the authority to distribute food to hungry refugees on a more permanent basis.

Even if he had been granted the ability to distribute food more generously, it is unlikely that Colyer would have done so. Like most Northern aid workers, Colyer espoused the “free labor” ethic, a central tenet in Republican thought. Such thinking held that the problems of poverty could not be resolved through charity alone but rather required the creation of opportunities for individual advancement. Charity in isolation, Colyer believed, created dependence, a form of enslavement. Part of a coherent Northern philanthropist ideology, this aversion to dependence had deep roots and fundamentally shaped much of Colyer’s (and later others’) approach to the refugee crisis in North Carolina.58 Significantly, Colyer titled his account of his work with black refugees in North Carolina Report of the Services Rendered by the Freed People to the United States Army in North Carolina. By emphasizing the productive work of black refugees on behalf of the Union war effort, Colyer was indicating that they were not dependent on the generosity of the federal government, but rather that the army depended heavily on the labor of freed slaves in North Carolina. Indeed, Colyer labeled one of the first sections in his report “Negroes Not a Burthen.”59

Especially during the spring of 1862, in the immediate aftermath of the occupation of New Bern, most fugitive slaves arrived in camp empty-handed. However, some fugitive slaves, especially those from plantations near Union-occupied towns, were able to abscond with some of their personal possessions. Those whose owners had fled in advance of the Union invasion often appropriated whatever material goods they believed necessary, limited by what they could reasonably transport. Vincent Colyer noted that some fugitive slaves arrived in New Bern with “the women carrying their pickaninnies and the men huge bundles of clothing, occasionally with a cart or old wagon, with a mule drawing their household possessions.”60 Even these few fugitive slaves who did arrive bearing clothing, blankets, and other household items could bring only enough food to sustain themselves during their escape. Once inside Union lines, they needed to find a new source of sustenance.

The material poverty of black refugees manifested itself in July 1862, when General Burnside was ordered to take part of his force north to support McClellan during the Peninsula Campaign. Burnside ordered several regiments to pack quickly, and, as they were unable to take with them the material goods (“mattress, tables, chairs, Dutch ovens, etc.”) they had accumulated over several months, soldiers left them in camp. As the soldiers boarded their ships, “crowds of negroes pounced upon the household goods which we had been enjoying.”61

The employment of adult men did little to alleviate the deepening humanitarian crisis. Working as manual laborers or scouts, men were provided with clothing, a soldier’s ration, and a small income. However, an informal census taken by Vincent Colyer during the summer of 1862 revealed that only one out of every four black refugees was an adult male. With the exception of a handful of black women who worked as hospital nurses (earning four dollars per month), the majority of the refugee population, women and children, were left to fend for themselves. From the very beginning of the Union occupation of eastern North Carolina, black women found themselves excluded from Union labor policies that empowered black men. While black refugee men gained government employment as spies, scouts, and manual labors (and eventually as soldiers), no equivalent positions existed for black refugee women, who found themselves excluded from the federal bounty. Some fugitive women offered Union soldiers their services as cooks and laundresses. One soldier noted that “the Negro women are round every day selling gingerbread[,] cakes[,] pies[,] and other things.” Another New Bern soldier noted that with the exception of bread, meat, and coffee, the majority of foodstuffs consumed by soldiers in his unit were “bought of negresses, who come up here by scores to sell their stuff,” including apple and sweet potato pies and yams. When army rations proved unpalatable, he and a dozen of his company evaded the guard patrolling the town to have “supper at the little low house of a negro woman, famous for her skill in cookery,” where they dined on “a stunning ham, boiled sweet potatoes, tea, coffee, and oysters and tripe.” A Massachusetts soldier noted that “there are lots of ‘contrabands’ around; from sunrise to sunset they are in the camp with almost everything in the eating line: gingerbread, pies, oysters, plenty of cookies, sweet potatoes, fried fish, etc.” Teenage boys not old enough to work on fortifications hired themselves to Union officers as servants. One soldier noted that “the black boys want to hire out as servants, and at such low rates that many of the men in the ranks have one to run errands, draw water, [and] wash their tin dishes.” A tent of Massachusetts soldiers hired “a darkey boy (about 16 years old) to wash dishes[,] black our shoes and do our errands. He is a treasure and a character.”62

Desperate for employment, fugitive slaves took whatever positions were available to them, which at times included tolerating abuse by Union soldiers. Writing to his family from New Bern in June 1862, Union officer Rowland Hall described Richard Butler, a fugitive teenage slave from Warrenton whom Hall had charged with the maintenance of his horse. Although Hall praised Butler for his diligence and expertise with horses, he derided his intelligence, noting that he had “a forehead less than an inch high.” Coming from a wealthy New York family, Hall instinctively treated Butler as his inferior, claiming that he was “just as much my slave as if I owned him. I am obliged to govern him in this way because he can understand no other. I sometimes threaten to have him tied up, & always to good effect.” Richard Butler’s experience suggests that his employment options were limited. One Massachusetts soldier dismissively compared black children to pets, noting that “we picked up at Plymouth, as soldiers will, many pets—a curious lot—squirrels, owls, raccoons, birds, and little darkies, the latter quite useful in blacking shoes and such odd jobs.”63 As the population of refugee black women and children within Union lines grew to approximately seventy-five hundred by July 1862, finding employment became increasingly difficult.

The material condition of white refugees in eastern North Carolina in the spring and summer of 1862 did not differ significantly from that of African American refugees. Most arrived with little more than the clothes on their backs, especially those men fleeing Confederate conscription. According to one solider in Washington, “Every [white] family coming into our lines required immediate attention . . . not less than one family daily, and often as many as half a dozen families in one day, the duty falling upon the Provost-Marshal to procure a tenement for each, supply them with some kind of furniture, and make provisions for rations until they could manage for themselves.” However, as both housing and furniture were in short supply, “it was often necessary to rob Peter to pay Paul, the result being that both were left poverty-stricken. . . . Many poor women with children, were forced to live in small rooms, without bed, table or chairs, subsisting on the meager rations furnished by the government.” Unlike black refugees, white refugees had no immediate employment opportunities devolving from the Union military occupation. Distrusted by Union officers and enlisted men, white refugees were not hired to work on fortifications by the Union army or by Union officers as servants. White refugees were also unwilling to work for the low wages that black refugees accepted. One soldier noted that while black refugees were “very intelligent and charge reasonable prices,” white refugees “ask four times what they are worth.”64

Unable or unwilling to find work, white refugees turned to the federal government to provide food. Vincent Colyer reported that four hundred white refugee families, some eighteen hundred individuals, received food from the army commissary. Colyer noted that “some of these families had a few months before been in affluence, [and] many children and ladies of refinement came for food.” For white refugees accustomed to luxury, such dependence on the beneficence of strangers proved humbling. A white refugee identified only as “Miss Mary —” pleaded to Vincent Colyer that “necessity compels me to come and ask you for provisions, although it is very galling. . . . We have been raised in affluence, but we are poor now. . . . Our rents are all stopped and our servants have left us. We must now have something to live on.”65