Mary Bryan spent the morning of March 14, 1862, supervising slaves in the kitchen rather than preparing for her next three years as a refugee. Like many residents of New Bern, Bryan expected that Confederate defenders would be able to repulse the expected Union attack on the town and wanted to prepare extra dinners, hoping to feed the triumphant Confederate soldiers after the battle. Bryan had celebrated her twenty-first birthday only three days earlier. Married in 1859 to Henry Ravenscroft Bryan, a planter and lawyer, Mary Bryan had her first child, a son named Norcott, in 1860 and had recently discovered that her second child was on the way. Although many of the young men in New Bern had enlisted in the Confederate army, her husband had been prevented from joining up by a persistent physical malady. Both Mary and Henry Bryan were children of planters and had inherited or acquired nearly fifty slaves, most of whom worked on their plantation outside of town, though at least three house slaves lived with them in New Bern, attired in white caps and aprons. Although the exact menu they prepared that morning remains unclear, Mary Bryan later recalled that a proper feast would not be complete without “large turkeys, old hams, home-made pickles, mince pies, syllabub and calf foot jelly, [and] sweet potatoes.”

While Mary Bryan eagerly prepared for a Confederate victory, her husband was less optimistic. Henry Bryan had concluded that a Union invasion of the North Carolina coast was likely and therefore it would be “useless to make a crop for another year.” In January 1862 he sent some of their field slaves to his father’s plantation in Wake County near Raleigh, surmising that they would be safer in the interior. While they contemplated moving themselves to the interior, Mary Bryan was reluctant to leave their stately New Bern home. She had recently sold her childhood pony to buy a “very handsome bookcase” and the house was “nicely furnished, a year’s provisions in the smokehouse, in the pantry all sorts of Jellies, pickles, catsups, cordials.”

When the Confederate center broke just before noon, soldiers fled chaotically through the town, burning the Trent River Bridge in their retreat. Most soldiers headed to the westbound train that had been kept at full steam in preparation for a mass exodus. When the Bryans and other civilians still in New Bern witnessed the soldiers fleeing through the streets, they joined the evacuation, forming “a perfect panic and stampede, women, children, nurses, and baggage getting to the depot any way they could. Our home and hundreds of others were left with the dinners cooking, doors open and everything to give our Northern friends a royal feast, which I understand they thoroughly enjoyed.” The Bryans only had time to pack a few trunks before they left New Bern. As Mary Bryan left her house, she envisioned its fate when Union soldiers, “in their mad rage,” occupied the town. She also knew that their plantation outside of town would share a similar fate, later recalling that when the Union army invaded New Bern, “we lost everything. The negroes were freed, the houses burnt, the brick house, which was built of bricks brought from England, pulled down, trees cut down, and the plantation left a barren wilderness.”

Accompanied by their domestic slaves and Mary Bryan’s mother, the Bryans were lucky to make it to the train before its departure. Many refugees fleeing New Bern in advance of the Union army were forced to walk, either because they were turned away from the overcrowded train or because they tarried too long before heading to the depot. Another New Bern refugee remembered that she “left on the cars with my babies and their nurses. There was panic, women and children fleeing for their lives.” Overburdened by its civilian and military passengers, the train pulled slowly out of the New Bern depot, more slowly than many of its passengers would have liked. Huddled with her family, Mary Bryan did not know where she and her family would live when they disembarked. The overcrowding on the train made the air difficult to breathe. Young Norcott, sitting with his enslaved nanny, Mammy Ria, squirmed during their long journey inland.

After switching trains at Goldsboro, the Bryans disembarked at Company Shops, now called Burlington, a railroad town halfway between Hillsborough and Greensboro. There they were able to rent two small rooms in a house adjacent to the railroad tracks, cramming into tight quarters, “our excess baggage stored elsewhere.” Shortly after arriving at Company Shops, Mary Bryan’s mother, always in poor health, took ill, as did young Norcott, “who took the whooping cough on the [railroad] cars, which was followed by measles and then slow fever.” In July 8, 1862, less than four months after fleeing New Bern, Norcott died from his illnesses. Mary and Henry Bryan buried their son in a corner of a graveyard in Greensboro. After the war, Mary Bryan was unable to find his grave, as there was “so much burying there during the war.” She concluded that “I consider his death as much due to the war as if [he] had been killed by Yankee bullets.”

Shortly after Norcott’s death, Mary Bryan gave birth to a daughter, Fannie. When the family was well enough to move, they relocated briefly to Lexington, North Carolina. Located just south of Greensboro, Lexington, like Company Shops, was along the North Carolina Railroad, providing the family with the opportunity to return east when and if the opportunity presented itself. Apparently they did not receive a warm welcome in Lexington, leading Mary Bryan to observe that “the refugees in some instances were not cordially received by the up-country people, and had it not been for the yellow fever, which was so fatal in New Berne in 1863, it would have been better for us to have remained at home.” After several unpleasant months in Lexington, they decided to move to Wake County. They hoped to move to Raleigh, but the city had become saturated with refugees from eastern North Carolina and Virginia, and it proved impossible to rent a house, so they settled for a log cabin owned by Henry Bryan’s father in Wake Forest, a distinctly modest abode compared to their residence in New Bern. Here they were reunited with the slaves that Henry Bryan had removed to Wake County prior to the New Bern invasion. As they were overcrowded and temporarily impoverished, Mary’s mother suggested that they sell some of their slaves to buy more land and supplies, but Henry Bryan refused. Although he was physically unable to fight for the Confederacy, he was “heart and soul” with the cause and believed that selling his slaves would run contrary to the ideals of the new nation, “feeling we should risk all” in its defense.

More than one hundred miles from the nearest Union army, the Bryans felt secure in their Wake County refuge. Their stay, however, was not without incident. Late one night in early 1863, Mary Bryan was woken by her mother, who said she heard noises in the yard. Alarmed, Mary and Henry peered out of a small four-pane window into the yard, where “a great many negroes were singing and playing around the fire with many demonstrations of joy.” Swinging their arms as they danced, the slaves sang, “Hurrah, hurrah, we are free, we are free!” Glancing at Fannie, still asleep in her crib, Mary worried that “perhaps in a few hours the last of my race would be gone . . . perhaps before morning each one of us would be massacred.” Although they kept constant vigil during that “night of horrors,” by morning the threat had passed, with no evidence of “the terrible mental agony we passed through.” When Henry Bryan questioned his slaves about the events of the previous evening, he learned that “our negroes were having an unusual time with some neighboring negroes.” While it remains unclear what prompted the Bryans’ slaves to celebrate, they possibly had heard news of the Emancipation Proclamation. Although they had been removed to the Confederate interior to isolate them from the destructive effects of the war, when news of a future freedom reached them, they rejoiced, even when that freedom lay two years in the future.1

Sometime during her stay in Wake County, Mary Bryan glued a fifty-two-line poem published in the newspaper into her scrapbook. Written by another eastern North Carolina refugee who had sought safety in the North Carolina Piedmont, the poem was entitled “The Refugee,” and Mary Bryan returned to it over and over again during her time in Wake County and in later years when she reflected on her experience as a refugee. Like the poem’s titular character, Bryan had been “doomed to roam, away from my beloved home,” a home now “occupied by foes, who rudely scoff at all our woes.” In the poem’s central image, the refugee stands on the banks of the Neuse River in the Piedmont, imagining how a leaf entering the flow here would eventually flow past her home in New Bern. The similarity between the poem and her own circumstances resonated deeply with Mary Bryan, who saw herself “removed from all I love.”2

The story of Mary Bryan, her family, and their slaves resembled those of many other refugees who fled to the North Carolina Piedmont during the Civil War. Because of its location in the Confederate interior, the North Carolina Piedmont was among the preferred destinations for many white refugees. Until the final days of the Civil War, the Piedmont was effectively isolated from the threat of Union invasion. The nearest Federal army was in New Bern, more than one hundred miles to the east of the Piedmont, and rarely appeared interested in advancing into the interior. To the north, the Piedmont was protected by heavily defended Virginia, to the south by South Carolina and Georgia, and to the west by the Appalachian Mountains.

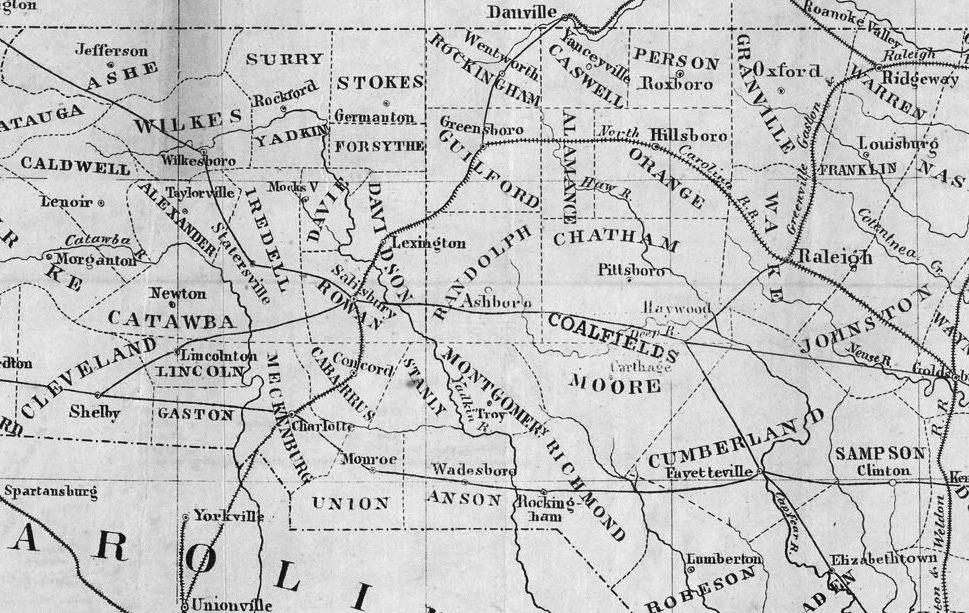

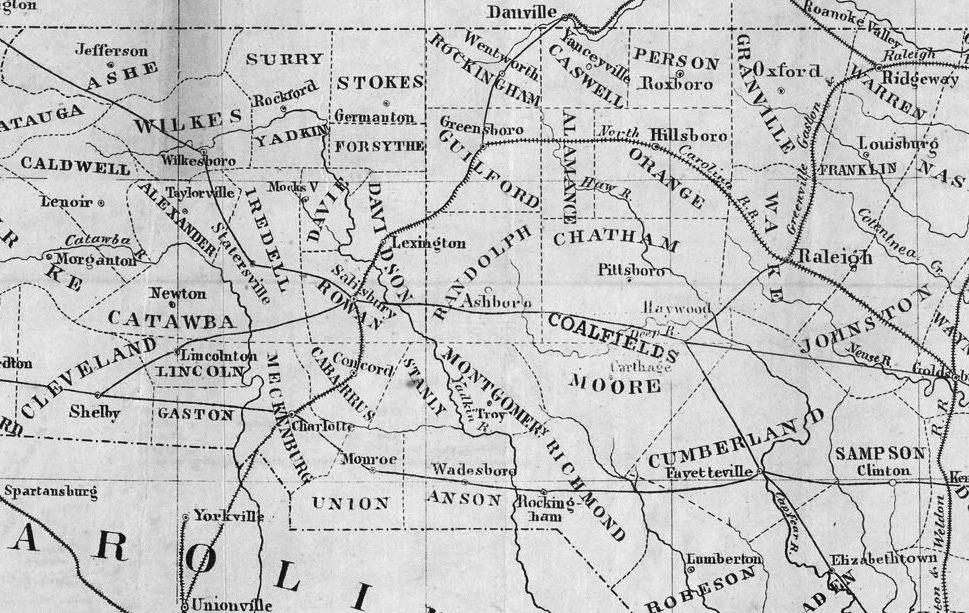

Figure 6. The North Carolina Piedmont. Compiled and drawn by G. Schroeter, from A North Carolinian’s Hints on the Internal Improvement of North Carolina (1854).

White refugees in the North Carolina Piedmont expected to find a sanctuary where they could continue their lives unencumbered by the effects of war. Anticipating that their geographic isolation from the front lines would permit them to create new homes in which they could mirror their lives before the war, white refugees flocked to the hills of central North Carolina. They discovered, however, that even in the Confederate interior, war exacted a heavy toll. The influx of refugees into the North Carolina Piedmont created significant housing and food shortages, leading many wealthy refugees to shelter in modest dwellings and feast on meager fare, while poorer refugees struggled with homelessness and starvation. Overcrowding and increased mobility in towns set the stage for contagious disease to spread through refugee communities. Far from home, white refugees struggled with homesickness and isolation, discovering that the North Carolina Piedmont was as much a prison as a sanctuary.

The North Carolina Piedmont had a particular attraction to slave owners. In December 1862 Wake County resident Giles Underhill wrote to his children in Mississippi that they should bring “your negroes to North Carolina . . . [as] they would be safer here than there for a while. There has been a great many negroes brought up from the eastern part of this state, to the middle and western counties.”3 While the removal of thousands of enslaved African Americans to the North Carolina Piedmont may have extended the term of their bondage, it simultaneously transformed the nature of their enslavement. A fuller understanding of the experiences of these slaves and slave owners should complicate our understanding of the effect of the Civil War on slavery and of the transition from slavery to freedom. While slave owners hoped that removal would enable them to perpetuate slavery in wartime, it fundamentally weakened owners’ authority over their slaves. Removal also fragmented established slave communities, as slave owners frequently divided their holdings.4

Slavery’s economic impact shaped important political and cultural differences between the eastern slaveholding regions of North Carolina and the Piedmont counties where slave owners removed their slaves. Sometimes referred to as the Quaker Belt because of significant Quaker settlement during the colonial period, the central Piedmont counties of North Carolina contained significant Unionist sentiment during the secession crisis and during the war itself. The Heroes of America, a secret Unionist organization, had a substantial base in the Piedmont, and prominent Unionists such as Bryan Tyson and Hinton Rowan Helper came from the area. Furthermore, many residents of central North Carolina who were not Unionists manifested a hostility toward Confederate and state policy during the war due to high taxes and conscription, resulting in some of the highest rates of desertion and draft evasion in the Confederacy. Therefore, when slave owners from eastern North Carolina and across the South removed their slaves to central North Carolina, they were taking them to a region in which anti-Confederate and antislavery sentiments were among the strongest in the Confederacy.5

Some white residents of coastal North Carolina quickly recognized the threat posed by the proximity of the Union army and made arrangements to remove themselves to the interior. In early September 1861, one week after the Union invasion of Hatteras Island, twelve-year-old Susie Mallett in Hillsborough wrote to her father, then serving with the Confederate army, that his sister had arrived in town. She wrote, “Aunt Mary arrived here from Newbern last week. The Yankee droved her from it. I suppose you heard that the Yankee had taked Fort Hatrass near Newbern. And all the people thought it wasn’t safe to stay.” In September 1861 lawyer David Schenck was among the first to note the removal of slaves to the interior, writing in his diary that trainloads of white refugees were arriving daily in Raleigh from coastal North Carolina and that “negroes too are being sent off in numbers to the west for security.”6 While a few slave owners began to remove their slaves from vulnerable parts of the Confederacy early in the war, and meticulously planned the removal of their slaves, most slave owners waited until the last minute to relocate their slaves and themselves from homes under threat from Union forces.

The refugee crisis in the North Carolina Piedmont began in earnest during the spring of 1862, after three events gave slaves and slaveholders reasons to hope and to despair. The first was the Union occupation of the North Carolina coast, with the capture of Roanoke Island in February and of New Bern a month later. White residents of New Bern, Beaufort, Washington, and other eastern towns fled en masse during the Union invasion. Most refugees, like Mary Bryan, left precipitously, taking little with them except what they could carry. The routes of most white refugees followed the railroad lines west from New Bern, through Goldsboro, Raleigh, Hillsborough, Greensboro, Lexington, Salisbury, and Charlotte, forming a crescent of refugee communities.7

For enslaved African Americans in the coastal plain, the Union occupation of coastal counties proved an irresistible lure. For slaveholders, the threat posed by Union occupation of eastern North Carolina caused many of them to forcibly remove their human property to locations they felt were more secure, beginning a mass forced exodus of slaves from the eastern third of the state to the North Carolina Piedmont. One planter estimated that “not fewer than two thousand negroes” were removed from Washington and Tyrell County to the interior during a ten-day period in October 1862. In October 1862 Cushing Hassell, a merchant and Primitive Baptist clergyman from Williamston, noted in his diary that there was “a constant stream of emigration from the lower counties to the upper Counties, especially a great many negroes being carried up.” Historian Bell I. Wiley observes that “travelers on the highways often met great droves of slaves moving from the coast.”8

A second impetus for the refugee crisis in the North Carolina Piedmont was the Peninsula Campaign during the spring and summer of 1862. With Union forces threatening Richmond and much of eastern Virginia, white refugees fled to Hillsborough, Raleigh, and Greensboro in hopes of finding a sanctuary from violence, and slaveholders sent thousands of slaves to central North Carolina, where they believed they would be secure. Among the thousands who fled Richmond that summer was Confederate president Jefferson Davis’s young wife, Varina, who fled the city with their four children, at least three servants, and $12,000 in Confederate currency. Safely ensconced in Raleigh’s prestigious Yarborough House, Varina Davis received both public and private denunciations for leaving her husband. She was accused of cowardice and harboring Yankee sympathies, with one newspaper comparing her to Marie Antoinette. While Varina Davis received unusual criticism because of her decision to leave, she was far from alone in deciding to flee Richmond for the safety of Raleigh, as the city became overcrowded with refugees. One Raleigh resident noted that “there are many here whose homes are threatened, and they have sought refuge here, and there are many who have no homes.”9

The overcrowding in Raleigh and other Piedmont communities increased throughout the summer of 1862. An outbreak of yellow fever in Wilmington in August 1862 caused many of its residents to flee the city for the North Carolina interior. Although many of Wilmington’s most prominent and wealthy residents had already left the city in March during Burnside’s invasion, at least nine thousand residents remained when yellow fever arrived aboard the blockade runner Kate, carrying “bacon and other supplies” from Nassau.10 According to the Wilmington Journal, more than half of the city’s population left for the North Carolina interior during the epidemic. Of the 4,000 who remained, 650 died of the disease. In his diary, Wilmington resident Nicholas Schenck described “a panic to get away—citizens and family—going in all directions. . . . Every body—who could get away—left town.” Another Wilmington resident noted in September 1862 that “the fever is much worse here and getting worse every hour. . . . Everyone that can get off are leaving.” When Schenck briefly visited at the height of the epidemic, he was shocked “to find almost a deserted town . . . every house on Front Street—closed and shut-up—did not met or see a soul.” William Calder, a Confederate soldier from Wilmington stationed in his hometown, wrote to his mother that “the physicians advise families to leave town, and all who can are doing so.” Frightened by the Union invasion of New Bern months earlier, Phila Calder had already left Wilmington for Warrenton, where both she and her sons felt she would be safer. In April 1862 William Calder had written her that “you can’t imagine the joy we feel that you have at last secured a place of refuge, and one that promises to be so pleasant. We could never content ourselves as long as you remained in Wilmington liable to be left alone and unprotected at any moment.”11

Many inland communities worried that refugees would bring yellow fever with them. How yellow fever spread remained a mystery, and medical authorities debated whether it could be contracted from infected patients.12 When Nicolas Schenck fled the city for Warsaw, some sixty miles to the north, he found “every hotel quarantined against us—coming from Wilmington.” In a September 1862 meeting, Fayetteville’s mayor and city council declared that “yellow fever exists in the town of Wilmington in a most malignant form, and a general apprehension having seized upon the inhabitants of this town that the disease may be communicated by continued intercourse between the two places.” To prevent its spread, they ordered that “all intercourse between the town of Wilmington and Fayetteville be and is hereby suspended,” requiring that refugees from Wilmington remain outside of the city limits and imposing a forty-eight-hour quarantine and medical inspection for all vessels that had passed through Wilmington. Recently elected governor Zebulon Vance also worried that refugees would bring yellow fever to the interior. In a letter to his wife, Vance warned her that “the yellow fever is raging so at Wilmington that some fears are entertained it may spread. The fugitives have already carried it to Fayetteville & there is one case reported here [Raleigh], though it is supposed it will hardly be communicated in that way.” Vance warned his wife, then in Buncombe County, not to come to Raleigh until later in the year, when winter cold would lessen the risk of yellow fever.13

News of the deaths in Wilmington reached refugees who had fled the city. Along with many others fleeing the city, the Cronly family settled in Laurinburg, more than one hundred miles to the west. Safe from both the direct effects of the war and the disease, they nonetheless experienced the epidemic vicariously, as “every day the train brought the small sized bulletin containing little but the list of the sick and the dead, and always among the latter the name of some familiar face that should never be seen among us again.” Eliza Hill, a refugee from Wilmington who had fled during Burnside’s invasion, contrasted her new home in Chapel Hill with the news she received daily from the coast, writing in her diary that “everything looks so bright & cheerful today that I can scarcely realize the melancholy truth, that hundreds are down in my native town with yellow fever. . . . [By] last accounts, Wilmington was said to be one vast Hospital.” Not all civilians were able to leave Wilmington before becoming infected. Marie Reston, married nine months earlier and with a newborn baby, was among the first people in Wilmington infected. During her illness, which lasted several weeks, many of her close associates also became infected, including her baby, who succumbed to the disease. Only after she was well enough did she travel to Hillsborough, where the colder weather was believed to be healthier.14

Many of the white refugees fleeing the yellow fever epidemic in Wilmington left their slaves behind. When the DeRosset family fled the outbreak, they left their home under the care of a few slaves, allowing them to rent out their time during the day. At the height of the epidemic, Eliza DeRosset, safely ensconced in Hillsborough, received a letter from William Henry, one of their slaves whom they had left in Wilmington. He informed her that “i hav bin sick all this week But ar gitting Better.” He warned them that several of their other slaves had “Bin vey Sick with the yeller fever for sevel days pass” and that one of them had been required to work by the family who had rented her despite her illness, such that “she is all mos wurk to Death By them.” William Henry’s letter also included a note from another sick slave, Bella, who noted that “provisions are very scarce here & nearly all the stores are shut up. The town looks lonesome most all the people has left.” Bella asked Eliza DeRosset about those slaves she had taken with her to Hillsborough and asked her to “give our love . . . to Marriah & Fanny & Peggy & tell them if I never see them in this world a gain I hope to meet them in heaven where parting will be no more.” When Eliza DeRosset wrote to her daughter in Charlotte about the suffering that William Henry and Bella described in their letters, she reassured her that “I have heard that the fever seldom proved fatal to negroes.”15

Despite the threat posed by Union forces and disease, many eastern North Carolina slave owners needed to be persuaded that removal was necessary. They received some of the earliest admonitions to remove their slaves from friends and family members. In December 1861 Alice DeRosset advised her sister that “as to your servants . . . you had better take every one of them up with you, away from the Coast.” Captain John Benbury, serving with the First North Carolina regiment in Virginia, repeatedly urged his wife in late 1861 and early 1862 to relocate herself, their infant daughter, and their slaves from their plantation near Edenton. Harriet Benbury ignored his advice until Union gunboats under Gen. Ambrose Burnside appeared near Edenton, when she relented and moved the family and slaves to the interior.16 Harriet Yellowley wrote to her brother about the propriety of keeping his slaves near sites of Union incursions in eastern North Carolina. “I feel very uneasy about our servants at home,” she wrote in September 1862. “I wish they were all away from there.” After her brother ignored her suggestion, she reiterated it a month later. “There are a great many Negroes being sent up from the lower countrys [sic],” she wrote. “Do you not think it would be advisable for you to have yours brought up after housing your crop?”17

After the Union invasion of eastern North Carolina in early 1862, newspapers joined the chorus of voices imploring eastern slave owners to relocate their slaves to the interior. In May 1862, three months after Union occupation of Roanoke Island, the North Carolina Standard “urged upon our Eastern planters, who may be thrown near the enemy’s lines . . . to remove their force as soon as possible to the up-country. . . . This is a matter of the greatest importance, and true patriotism should prompt them to do so.” Appealing to planters’ material self-interest, the paper argued that removed slaves could profitably harvest fields in the upcountry vacated by farmers now in the Confederate army. Three months later, the paper continued to urge eastern slave owners to remove their slaves. In August 1862 it claimed that “thousands of negroes have been lost or ruined, and the information we have from the Eastern Countries especially beyond Roanoke, is alarming. Every negro east of Kinston, Tarborough, Hamilton, Windsor, Murfreesboro, &c, should be removed, if possible, from that section.”18

Although many Confederate officials initially opposed the removal of slaves to the Confederate interior, after the Emancipation Proclamation and the enlistment of African Americans into the Union army, Confederate officials at both the state and national levels strongly advocated removal. A letter from Col. William Holland Thomas in November 1862 may have persuaded Governor Vance to reconsider his initial opposition to removal. Famous for leading a regiment of “Indians and mountaineers,” Thomas recommended that Vance should order “able bodied negro men belonging to the counties in reach of the enemy [be] transferred from their present positions to work on the extension of the [Western North Carolina] railroad.” Removing slaves, Thomas argued, had two main benefits. First, it would protect the institution of slavery from the threat posed by the presence of Union armies in the area. Second, “every able bodied negro kept out of the hands of the enemy would lessen the number of troops we have to raise in defence,” a savings, Thomas estimated, of $10,000. Therefore, not only would removing slaves prevent them from running away, but it would also facilitate a much needed railroad connection, resulting in a substantial savings for the state and slaveholder alike. In 1863 Governor Zebulon Vance issued a proclamation, declaring “it the duty of all slaveowners immediately to remove their slaves able to bear arms.” Vance’s stance on removal mirrored that presented by Confederate officials in Richmond, who, in March 1863, told planters in coastal Florida, Georgia, and the Carolinas to remove their slaves to the interior, “since they were liable to be lost at any moment.”19

Despite the pleading of friends, the press, and government officials to remove slaves, some slave owners resisted. For some, removal suggested retreat and submission, and they therefore stayed with their slaves in vulnerable areas of the Confederacy despite the threat posed by Union armies. According to his diary (which he wrote in the third person), Cushing Hassell had “made up his mind & so told them [his slaves] in the commencement of the war that he would keep them at home [in Williamston, North Carolina], not hire them out, or send them up the country or sell them.” Hassell believed that God would protect him and his human property from possible harm. His decision not to remove his slaves had decidedly mixed results. Almost all of his neighbors fled Williamston, which was visited by Union forces on several occasions, “leaving H. [Hassell] & his family almost entirely alone.” At the start of the Civil War, Hassell owned twelve slaves; by February 1865 he had lost three men, who had run to Union lines, and one woman, who had “behaved so badly that he was compelled to get clear of her & consequentially sent her & her child to Greensboro & sold her, supposed even that to be better for her than to send her to the Yankees.”20

Other slave owners were reluctant to remove their slaves because of the logistical difficulties involved. After a dinner with friends from Raleigh in October 1862, Catherine Edmondston confided in her diary that “the negroes they were urgent for us to remove, but where to carry them?—that is the question. How to support them, how to house them, all questions easier put than answered.” For large slaveholders, slave removal was an expensive proposition. Removing slaves might make it more difficult for them to run away to Union armies, but it also removed their productive labor from the plantation. Slave owners intuitively knew that while they might be able to find employment for their slaves in the upcountry, it was unlikely to be as profitable as that same labor on their home plantation. Further, slave owners recognized that finding housing and sufficient provisions for their slaves would be expensive and difficult, if not impossible, given wartime shortages. Finally, slave owners worried that transportation would be prohibitively expensive. Writing to his friend James C. Johnston, William Pettigrew estimated that it would cost approximately $2,500 for Johnston to remove his nearly three hundred slaves from Edenton to Rowan County by rail. Pettigrew himself, who had already successfully removed his slaves from Washington to Chatham County, debated the merits of taking them farther west to Davie County in order to place a greater distance between them and Union armies. In Pettigrew’s mind, the most significant barrier to a second removal was that “the cost would be very considerable.”21

Given these difficulties, few slave owners removed their slaves en masse. Instead, they adopted a piecemeal removal plan that prioritized some segments of the slave population. Deciding which slaves to remove often proved contentious in slaveholding families. Catherine Edmondston described in her diary a conference held between her husband, father, and brother in October 1862 concerning the removal of the family’s slaves. Her husband “advocates the removal of all the hands—women & children—leaving on the aged, the decrepit, and weakly. Father & brother oppose it—say the cost of feeding them is too great—impossible to build houses for them, etc.!” The men, she noted, after much deliberation “counted & assorted the negroes, so many to go, so many to stay.”22

Most slave owners placed the highest priority on removing their healthy male slaves. Not only were they the most valuable form of slave property, but they were also the most likely to run away to Union lines. Although he was only five years old, William Sykes vividly remembered the day that he and his father were informed that they would be removed to the interior. With approximately one hundred other slaves, Sykes and his father were marched from Tyrell County “straight ter de Blue Ridge mountains,” where their owner believed “dar won’t be no trouble, case dey [Union soldiers] won’t dar atter us.” In a decision that was not uncommon, Sykes’s owner decided to remove his only male slaves to Buncombe County, leaving female slaves at home, including Sykes’s mother and female cousins.23

Slave owners also prioritized the removal of domestic servants, especially those charged with childcare. When William Blount Rodman, a Beaufort County politician and lawyer, relocated his family to Greensboro while he served in the Confederate army, he arranged for only seven of his more than fifty slaves to accompany them. One of the Blount children later recalled that five of the seven were house slaves, and his mother rented the two others to work on the Piedmont Railroad. Tristim Skinner, away serving as an officer in the Confederate army, advised his wife, Eliza, to take only a handful of slaves from their Chowan County plantations, including a cook named Priss and a carpenter named Thomas “with part of his tools & soon make you all the tables, benches, & many other bulky articles you would want & let only compactly packing articles be brought from home.”24

Elderly and infirm slaves were the least likely to be removed. Not only would it be difficult for them to make the trip inland, but slave owners recognized that it would be impossible to find employment for elderly slaves in the interior. Indeed, some planters left their property in the hands of trusted elderly slaves. When Union soldiers made sallies into northeastern North Carolina in 1862 and 1863, they often found elderly slaves in charge of plantations, the owners having removed themselves and their most valuable slaves into the interior. Because of the cost involved in removing slaves, some slave owners were unable to relocate even their most valuable property. Alabama slave owner Sarah Espy recorded in her diary that her neighbor had sold much of his personal property prior taking his slaves “to N. C. to avoid the Yankees.” Espy herself believed that she could not afford the expense, staying in her Alabama home despite the threat posed to herself and her slaves by the approaching Union army.25

Slave removal could be a perilous business. The examples provided by the Pettigrew brothers illustrate how slaves actively resisted removal. Two of the wealthiest planters in Washington County and the elder brothers of Confederate general James Johnston Pettigrew, Charles and William Pettigrew owned 254 slaves between them on three plantations. While both brothers remained paragons of the planter class, William proved luckier in politics and finance than Charles, his senior by two years. While William Pettigrew was elected in 1861 to represent Washington County in the North Carolina Secession Convention, Charles Pettigrew made a series of bad investments in the 1850s, requiring him to borrow money from his younger brothers.

Like many planters, Charles Pettigrew decided to remove his adult male slaves first, “leaving the women & children for the present.” However, when they discovered that they would be separated from their wives and children, all but two of his male slaves “took to the woods.” Pettigrew coerced the fugitive slaves to return by temporarily cutting off food rations to the women and children and decided to forestall removal for the time being. Charles Pettigrew’s brother William, probably in an effort to avoid the same circumstances, kept his slaves ignorant of his plans to remove them to the interior and, on the night of the removal, arranged for twenty-five soldiers to surprise his slaves in their quarters and escort “every man, woman & child to Chatham [County].” Given the practical difficulties of slave removal, some slave owners hired others to transport their slaves inland. In May 1862 George Reel, a Craven County slave owner, hired James Beckwith to take a slave woman and her two children “up the country to a place of safety, beyond the reach of our Yankee invaders.” In payment, Reel agreed to give Beckwith the slave woman’s older child “as a compensation for his services and trouble.”26

As the Pettigrew brothers’ cases suggest, most slaves opposed relocation, not only because it took them farther away from freedom but because it often resulted in broken families. William Henry Thurber, one of the slaves that the DeRosset family left in charge of their Wilmington property, wrote frequently to his owners, safely ensconced in Hillsborough, asking them to “give my Love to my mother,” whom the DeRossets had taken with them. Forced removal was particularly devastating to cross-plantation marriages, as enslaved husbands and wives were refugeed to geographically disparate locations.27 When Lucilla Mosely’s owner took her with him to Hillsborough from Wilmington, he separated her from her husband, an enslaved carpenter named Joseph Hall. Both slaves eventually escaped from their owners, reuniting at the black refugee camp in Hampton Roads, “where the lovers met again and were happily [legally] married.”28

Slaves responded to the possibility of removal by running away in increasing numbers to Union lines. While planters often attempted to prevent slaves from knowing about their imminent forced migration, rumors of relocation pushed slaves who were on the fence about making an attempt to reach Union lines to take the opportunity while it was available. In her diary Catherine Edmondston described a conversation with a friend from Elizabeth City whose “negroes had refused to come with them, how their Coachmen stole their best horse & started to run away in the night but fortunately was overtaken & sent back in irons to them.” Similarly, Rowan County lawyer David Schenck observed in his diary that “slaves unanimously refuse to be removed and if it is insisted on, they flee to the swamps. They are fully aware of the causes of the invasion and know that it involves their freedom.”29 Thus the voluntary migration of slaves to Union lines and the involuntary migration of slaves to the Confederate interior reinforced each other, pushing North Carolina’s enslaved black population east and west, toward freedom and slavery. With each passing month, as some slaves escaped to freedom, slave owners removed others to keep them from running away.

Refugee planters who fled an unexpected Union advance often brought little with them except their slaves when they relocated to central and western North Carolina. Cornelia Phillips Spencer described the refugees in Orange County as “the best and most highly cultivated of our Southern aristocracy” who had “fled hither stripped of all their earthly possessions, except a few of their negroes.” In February 1862 Catherine Edmondston, while herself preparing to evacuate her Halifax County plantation, visited her father’s plantation, where she was surprised to find the dining room crowded with refugees “to the number of nineteen whites and seventy negroes, all homeless & houseless.” After talking with the refugees, she discovered that the head of this extended family had gone out “to endeavor to rent a place where he could put his negroes,” but until then, they were crowded into the space that Edmondston’s father had allotted them.30

The threat from Union armies was not the only reason why most slaveholders in eastern North Carolina relocated their slaves; they also feared that their slaves would be impressed as manual laborers by the Confederate military. Many planters assumed that the Confederate military would be more likely to impress slaves from coastal counties to construct coastal fortifications. An 1862 law authorized the governor to impress slaves and free African Americans for war-related projects. One Washington County planter who refused to remove his slaves to the interior described the effect of these twin perils: “The valuable portion of my slaves left and went to the Yankees, the Confederates came and took the remainder that had proved faithful to me.” Slave owners worried about dangerous conditions on coastal fortifications and about the proximity of such work to Union forces. Furthermore, although slave impressments were supposed to be for a limited duration, many planters discovered that while Confederate officials were quick to seize their slaves to work on Fort Fisher and other sites, they were loath to return them.31

For both white and black refugees, the journey inland proved difficult. Like Mary Bryan, many white refugees fled via the railroad. Overcrowded and overburdened, railroads in North Carolina and across the Confederacy suffered from frequent breakdowns and long delays. An anonymous Virginia refugee captured the experience of railroad travel through North Carolina in an 1864 poem. He had fled coastal Virginia in the winter of 1862-63, leaving his home under the control of the “negro Yankee.” Like many refugees, he believed that he could find affordable accommodations in the Piedmont as “in the up country I thought, things might be bought / At living rates by a refugee.” When he arrived at the railroad depot, he was callously treated by the crew, as “the masters of the cars were as rough as grizzly bears, to this fugitive refugee.” The conductor instructed him sit on the only available spot on the floor of the passenger car, where he huddled with other refugees. Many of the windows in the car were broken, and the winter snow made the journey unbearably cold, an antique stove in the car providing minimal relief. As the train lumbered slowly southward, the refugees on board endured “with nothing to eat, or warm our feet.”

As the trainload of refugees crossed from Virginia into North Carolina, one of the railcars derailed. While some refugees worked to return the car to the rails, others huddled together around a fire. Fortunately no one was killed in the accident. However, railroad accidents such as this one were common in Civil War North Carolina. Wartime traffic overtaxed the railroad infrastructure, leaving both tracks and rolling stock subject to failure and causing many North Carolinians to become wary of railroad travel. In January 1863 A. W. Mangum warned his sister about the perils of riding on railroads in the North Carolina Piedmont. Not only were the trains overcrowded, making it “exceedingly disagreeable travelling on railroads now,” but “it is also very dangerous.” He warned her that “everyone now looks on the Central Road [North Carolina Railroad] as unreliable & badly managed. Scarcely a day passes without an accident of some kind between here [Goldsboro] & Charlotte causing delay.” Once righted, the refugee-poet’s train continued toward Charlotte, punctuating its journey with frequent stops for coal and water. Hungry and tired after his long journey, he expressed his joy at no longer being crammed aboard a railcar: “At last we had got to the town of Charlotte, In good time to be left all alone.”32

In addition to the overcrowded and frequently perilous conditions, travel via railroad had other significant limitations. Railroad passage was expensive, beyond the reach of many less affluent refugees. Railroads also significantly limited the amount of personal possessions that refugees could take with them into the interior. This limitation was particularly acute during the mass exodus from New Bern, when, in order to make room on the train for additional passengers, refugees were forced to leave trunks of valuable personal possessions behind at the depot to be seized by the imminently arriving Union soldiers. When railcars became filled to capacity, some refugees clung to the exterior of the car.33

Refugee families often used wagons to transport themselves and their dearest possessions. Unlike railroads or stagecoaches, wagons allowed refugees to bring many of their household goods with them. Refugees who diligently prepared for removal usually selected a mixture of practical household goods, including clothing, bedding, and cooking utensils, along with an assortment of family heirlooms and keepsakes. Usually these keepsakes amounted to tokens of home and family: a daguerreotype of a son or husband in the army, a grandmother’s jewelry, or a family Bible. In February 1862, after the capture of Roanoke Island and in advance of the battle of New Bern, Catherine Edmondston wrote in her diary that the “roads are crowded with Refugees in vehicles of every description, endeavoring to move what of their property they can to save it from the grasp of the invader.” A newspaper noted that the refugees “came across the country in carriages, wagons and in any way they could.”34

Overburdened wagons frequently broke down, as the weight strained the wheels and axles. The wagons also frequently found themselves mired in the deep ruts of eastern North Carolina’s muddy wagon roads. After a breakdown, wagons had to be unloaded before they could be repaired, and heavy items were often discarded. One refugee described the chaos on the roads thronged with refugees, wagons, and draft horses: “We were constantly in the sight of, and often jostled by moving crowds of people and vehicles. . . . Fugitives of every grade and degree of misery were toiling on, on foot, or in any kind of broken-down vehicle. Sick men, hungry men, and women with crowds of children, all hurrying on.”35

The migration into the Confederate interior placed many white women in unfamiliar positions. Particularly for younger adult women, whose husbands had gone off to fight, refugeeing required them to step outside of prescribed gender roles. Social custom in the antebellum South significantly limited white women’s ability to navigate the public sphere alone. Respectable women needed a male escort to travel to church or school or to visit relatives. The social proscription on respectable white women traveling alone grew out of a deep-seated belief in women’s fragility and the need to protect their sexual purity. With the Union invasion of the North Carolina coast, however, many white women believed that the menacing presence of Federal soldiers posed a much more significant threat to their sexual purity than traveling without a chaperone did. In the flight from New Bern, many respectable women had to travel unaccompanied for the first time, navigating the novel circumstances of buying their own train tickets, shouldering their own luggage, and eventually finding and managing a new household. For slaveholding women, refugeeing with their human property magnified these difficulties. Although plantation mistresses had long played a significant, if underappreciated, role in slave management, the particular demands of relocating themselves, their children, and their slaves to the interior proved daunting.36

White women of more modest means, accustomed to the difficulties of living and working in the public sphere, had an easier time navigating and adjusting to the novel social demands presented by refugeeing.37 However, poorer white women faced significant challenges meeting the financial and material problems posed by leaving home. For poor women, the most significant initial decision was how to depart in the face of Union occupation. Rail travel proved prohibitively expensive for most poor white women. Rural poor women in eastern North Carolina usually loaded whatever material possessions they had onto a wagon before embarking on their journey westward. Poor women living in New Bern and other towns usually had to flee on foot, bringing with them only what they could carry.

Many less affluent women in eastern North Carolina came to the conclusion that even if they could escape Union occupation, the demands of refugeeing outweighed the benefits. Many yeomen families, owning little moveable property, reasoned that they could not abandon their homes, even for a short time, without impoverishing themselves. For many yeomen, the need to protect their immoveable property outweighed the desirability of removing themselves from the sphere of Yankee influence. While almost the entire eastern North Carolina planter class refugeed themselves to the interior, common whites had to balance their desire to live outside of Federal control with the practical difficulties of refugeeing. When common whites did decide to leave home, they were much more likely than their planter neighbors to select a nearby refuge, one that allowed them to return home as soon as possible. Many common whites living in the no-man’s land between Union-occupied New Bern and Confederate forces in Goldsboro established temporary refuges within close proximity of their homes, often taking to the woods when Union soldiers approached, only to return home when the threat had passed.38

For many white refugees, the decision about where to live proved just as challenging as the decision about whether to leave in the first place. For those who fled at the last minute, like Mary Bryan’s family, the decision about where to stay initially was almost made for them. Having escaped New Bern via train, their initial refuge was along the railroad in Company Shops, a town built around the rail yard. Indeed, most refugees settled along the corridor created by the North Carolina Railroad. Completed in 1854, the North Carolina Railroad ran from Goldsboro through Raleigh, Hillsborough, Greensboro, and Charlotte, each of which hosted hundreds of white refugees, many of whom brought slaves with them. White refugees who fled to the interior well in advance of the Union invasion of the North Carolina coast also preferred urban areas along the railroad, believing that these communities would offer greater access to telegraphs, newspapers, and mail, all vitally important conduits of news and commodities during wartime. Many refugees also believed, incorrectly, that urban areas would have available housing. For many refugees, however, the most important factor in deciding where to settle in the North Carolina Piedmont was where their friends and relatives were, and many refugees settled near other refugees from home. Hillsborough, for instance, was the preferred destination for refugees from Washington County, while nearby Chapel Hill hosted several refugee families from Edenton. Consequently, cities and towns in central North Carolina swelled in population as refugees from across the Confederacy sought sanctuary.39

Almost all refugees struggled to find adequate housing in the North Carolina Piedmont. The demand for housing in Raleigh, Greensboro, Charlotte, and other large towns led to an immediate and significant increase in prices. Cornelia Phillips Spencer noted that in Chapel Hill “every vacant room was crowded at one time by refugee families from the eastern part of the State, from Norfolk, and latterly from Petersburg. And this was the case with every town in the interior of the State.” In May 1862 the Raleigh Register lamented, “This city is at present crowded to repletion with refugees from Virginia and different parts of the State. On Thursday night several ladies were compelled to sleep on the floor of the parlor of the Yarborough House [a popular hotel], and one party of ladies were obliged to sit up the whole night for the want of beds to lie upon.” The hotel’s most famous refugee-guest, Varina Davis, complained to her husband in May 1862 about the conditions at the hotel, noting that “the house is full to overflowing here, and the fare dreadful.” She found the rooms “terribly crowded, and very rough” with “everything in rags.” While she regretted the relative poverty of her situation, Varina Davis struggled most with the cost, telling her husband that she “could get well on but for the exorbitant charges.”40 After an uncomfortable month at the Yarborough House, Varina Davis moved her family to St. Mary’s School, an Episcopal girls’ boarding school in Raleigh, where they stayed until it was safe to return to Richmond.41 In October 1862 one refugee claimed that there was “not a house for rent in Raleigh.” In May 1862 the Western Democrat observed that “the population of Charlotte has been considerably increased within the last week or two, caused by the evacuation of Norfolk and Portsmouth and other places. The town is about filled up, and it is almost impossible to accommodate more.” The newspaper encouraged refugees to find homes outside of the city, noting that “houses can be obtained in Lincolnton, Davidson College, and other interior villages, pleasant places and living much cheaper than in Charlotte.” The paper also encouraged rural residents to take in refugees, asking, “Could not the farmers through the country take a few boarders? Eatables are hard to get in towns at this season.”42

As white refugees had occupied all of the available housing, slaveholding refugees found housing their human property almost impossible. Eliza DeRosset complained to her sister that while she had found an appropriate rental property for her family in Hillsborough, it had “no place of the servants.” In late 1862 planter Paul Cameron noted that “the poor refugees who have brought their slaves up the Country find it impossible to provide a home. . . . Those who hold them in large numbers must provide by purchase both homes & food! It is indeed a hard time on the slave holder and we can hardly escape ruin.”43

With urban housing in short supply, many refugees reluctantly settled in less accessible areas. Mary Bayard Clarke desperately wanted to live in Raleigh, where she could be close to family. Her husband, then serving in the Confederate army, counseled her against it, arguing that he had “great misgivings about the plan of your living in Raleigh,” as “the towns are filled with refugees.” Instead, he hoped that she would “find some good country family” to live with. He suggested that she consider living with a distant relative in Randolph County, as “living may be cheap there, as it is an abundant country and not very convenient to market, consequently the people would have more for home consumption.” While her husband saw the isolation in rural Randolph County as an asset, Mary Bayard Clarke felt that she needed to stay near family and communication lines and remained in Raleigh for the remainder of the war.44

Hoping to attract refugees unable to secure housing in urban areas, rural landowners advertised available property as an alternative. In a June 1862 advertisement titled “TO REFUGEES AND OTHERS!” a hotel in Graham advertised in a Raleigh newspaper that it had vacant rooms for “transient and permanent boarders.” Contrasting its rates with the high prices in Raleigh, the hotel noted that it had moderate prices and “10 or 12 refugees can be accommodated if early application is made.” Knowing that many refugees in Raleigh would be unfamiliar with the smaller Piedmont communities, the advertisement informed them that “Graham is in Alamance County, on the N.C. Railroad, and about 50 miles above Raleigh.” By noting its proximity to the railroad, the hotel’s proprietors hoped to entice refugees who might be concerned about living in rural areas. The advertisement concluded by noting that “the country is healthy and pleasant in the warm season.”45

Within a short time, however, even rural property in the Piedmont was in short supply because of the demand created by refugees. In October 1864 the Raleigh Daily Confederate ran an advertisement headlined “ATTENTION REFUGEES! Valuable Property for Sale.” Among the assets of the two-hundred-acre property in Granville County were its relative proximity to railroads (twenty miles from both the Raleigh & Gaston Railroad and the North Carolina Railroad) and its location “in a healthy section of the county, and entirely safe from raids from the enemy.” The site also included ten slave cabins, which must have been very attractive to slaveholding refugees. The most remarkable aspect of this advertisement, however, is that the Daily Confederate chose to highlight it on a separate page in the newspaper, noting that “‘Attention Refugees’ is well worth the attention of all wishing to purchase valuable property. In these days it is scarcely possible to purchase such.”46

Some refugees claimed that they were being gouged by property owners. In April 1862, when the city was overwhelmed with refugees from eastern North Carolina and Virginia, the Raleigh Biblical Recorder opined that “there are three national sins in the Bible: the oppression of the widow, the fatherless, and the stranger. No people should ever oppress the stranger—When refugees come from the lower part of the State, board, house-rent, and provision should be afforded on moderate terms.” A month later the Salisbury Watchman expressed a similar sentiment, arguing that “the hospitality of the people of Western Carolina is likely to be called forth this spring and summer, by our refugee friends of the East, who have been driven from their comfortable, well-furnished homes by the ruthless invaders of our soil. . . . In their condition, we would desire, and could appreciate, an act of kindness and hospitality; and there should be some pains taken, therefore, and some self-denial made, for their accommodation. They will need boarding houses, or houses to live in.” The Raleigh Christian Advocate concurred that Piedmont residents had a moral obligation to extend a hand and open a door for refugees, placing treatment of refugees within the framework of nationalism and religious obligation. According to the paper, “Surely a generous and patriotic people will not endeavor to place whose who have been driven into exile by a cruel and vindictive foe; but will . . . relieve as far as possible, by delicate and courteous acts, their pressing necessities.” The newspaper urged its readers to empathize with refugees, so that “the refugees scattered throughout the uninvaded portions of our Confederacy would meet with a much more cordial hospitality, and be the recipients of a much more bounteous generosity than many of them have hitherto been favored with.” The paper particularly targeted farmers, who, many refugees believed, unnecessarily raised their prices and limited their supply. Farmers, the paper argued, “should bear it in mind that it is no fault of the refugee that he is enduring the sad pangs of banishment, but that he is unwillingly constrained to occupy the present position. The refugee must have fuel, and food, and it is your duty to contribute as far as you can to his comfort. Let him have of your surpluses at such moderate rates that he may live as well as you; and be sure to supply with wood and other necessaries, but without endeavoring to relieve him of all his money at once.”47 Despite the efforts of newspaper editors to engender hospitality and generosity, many refugees believed that Piedmont property owners and merchants took advantage of their situation.

D. W. Bagley, a refugee from Williamston, complained that his landlord in Rocky Mount was “an unprincipled scoundrel, and did everything in his power to make life unpleasant for the refugees whose dependence upon him for supplies placed them almost entirely at his mercy.” After a year in Rocky Mount, during which he claimed to have been “swindled out of $400 or $500 by his landlord,” Bagley moved his family to a house outside of the city, which he shared with his two daughters’ families, some twenty-nine people in total. Not only was their new home significantly overcrowded, compromising any expectation of privacy, but their remote location made it difficult to communicate with his son, then in Confederate service, and to secure provisions. According to Bagley, after 1863, “the difficulty of getting provisions now becomes a serious manner.” His son-in-law “often travels day after day, over rough road, through rain and all kinds of weather, without being able to buy anything whatever. They have a certificate of need from a government agent, but it does not avail;—they, the refugees, are turned away empty-handed, while others can buy.” In June 1864 the Raleigh Daily Confederate published a letter from “A Refugee” from New Bern who complained about the “poor shelters we have been able to crowd together in, and what we eat, for which we pay enough, I am sure. We do not expect or wish the citizens to feed us or give us shelter—we only ask them not to abuse us.”48

Prominent North Carolinians often received letters from refugees in search of housing. Former governor and senator William A. Graham received frequent inquiries about the availability of housing in Hillsborough. In October 1862 Evelyn Perkins, the wife of a Confederate congressman from Louisiana, wrote to Graham that she wanted to relocate the family to Orange County. “Our object,” she wrote, “is to find a home during the war, & while we wish it comfortable, we do not expect anything on a very large scale. The neighborhood of Hillsboro we thought desirable, as affording Church and School opportunities, with pleasant society, & at the same time, as being remote from any probable incursions of the enemy.”49 Another former North Carolina governor, David L. Swain, also received frequent requests to procure housing for refugees. In August 1864 he received a letter from Lloyd Beall, the commandant of the Confederate Marine Corps, asking for Swain’s assistance in finding housing for his family in Chapel Hill “either at a boarding house or at the Hotel.” Beall was reluctant to impose on Swain, then serving as the president of the University of North Carolina, but he knew of no one better positioned to help him find a safe place for his family. “Let the state of things engendered by the war be my apology,” he noted. His wife and two teenaged children were currently living in Pendleton, South Carolina, but Beall felt “compelled by circumstances to remove them in early October” to a safer location. Aware that housing in the North Carolina Piedmont was at a premium, Beall wrote that his family would require only two rooms. Not only would Chapel Hill provide safety for his family, Beall wrote, but also “my children could have the advantages of education that place affords.”50

From the very beginning of the refugee crisis in 1862, refugees struggled with the quest to find housing that was both safe and affordable. The experience of two North Carolina women, Harriet Yellowley and Mary Lacy, reveals the challenges of finding a good home. Both women began their lives as refugees in 1862, hoping to escape the horrors of war by living in the safety of the North Carolina Piedmont. Harriet Yellowley left her home in Greenville in September 1862, moving to Oak Grove in Nash County, between Rocky Mount and Wilson. The unmarried forty-seven-year-old had lived with her unmarried younger brother, a prominent lawyer, in a stately house on Fourth Street in Greenville, set on 180 acres. Between them, they owned fourteen slaves and employed an overseer to manage their estate. In late 1861 her brother had raised a company of soldiers and received a captain’s commission. When his unit was sent east to defend Roanoke Island, Harriet Yellowley was left alone in their home. Like many of Greenville’s white residents, she decided during the summer of 1862 to relocate to Nash County, fifty miles to the west. On her own for the first time in her life and in a strange place, she felt an immediate sense of homesickness. “Oh! How I missed my home,” she wrote in a letter to her brother shortly after arriving in Nash County. “I have never half appreciated it until now. Should I ever have another home or return to that dear one I will never leave it unless I am driven away again.”51

Like many refugees, Harriet Yellowley did not plan to stay away from home for long and anticipated returning to Greenville as soon as the threat had passed. By November 1862, however, she had concluded that she would not be returning home anytime soon. Over the past two months, she had persuaded her brother to remove their slaves to Nash County, since “a great many [Greenville slaves] had gone to the Yankees.” The decision proved fortuitous for her, as she had recently heard from other refugees that Union soldiers had visited Greenville and “gave a general invitation to all the negroes to go with them.” Few slaves in Greenville took the soldiers up on their offer, although Yellowley heard that “the negroes were all well pleased at the sight of the Yankees” and were “unmanageable for several days after there [sic] departure.” In the aftermath of the Union incursion, Greenville slave owners scrambled to remove their remaining slaves inland. Harriet Yellowley met several slave owners from Greenville who had arrived in Nash County after losing a significant number of their slaves, including a friend who had lost more than thirty slaves. The result of the exodus from Greenville to Nash County, she wrote her brother, was that “the neighborhood is crowded with Refugees and negroes. A great many people have left Greenville and are still moving. What is to become of us all I know not.”52

For slave owners like Harriet Yellowley, the influx of white refugees and their slaves into Nash County created significant housing and food shortages. In a series of letters to her brother in November and December 1862, she complained about her difficulties in feeding and housing their slaves. All of their slaves, she wrote to her brother, had been safely removed to Nash County, but “I haven’t yet been able to get homes for them” as “the Neighborhood is filled with refugee negroes.” A week later she reiterated her dilemma: “The negroes are all here. I haven’t yet been able to get any of them homes and I fear I shan’t be able to do so, unless you pay very high for keeping them, provisions are very scarce and high.” Although she lamented having to trouble her brother while he was on the front lines, Harriet Yellowley could not see a viable living arrangement for herself and their slaves and begged him for whatever advice and support he could offer. She desperately wanted to procure proper housing for their slaves, but “the whole country is stocked with negroes and white people. . . . They are crowded and piled together.”53

Mary Lacy shared many of Harriet Yellowley’s difficulties in finding a home that fulfilled her need for security at a price her family could afford. In July 1862 Mary Lacy wrote to her stepdaughter about the rising housing prices in Warrenton, a town in the northeastern Piedmont popular with refugees from eastern North Carolina and Virginia. With an antebellum population of 1,520, Warrenton doubled its inhabitants almost overnight, causing homeowners to dramatically increase rent and board. In 1861 Mary Lacy had moved to Warrenton with her husband, a Presbyterian minister and former president of Davidson College, their three young children, and two slaves. With housing at a premium in Warrenton, all seven members of the Lacy household crammed into one bedroom in a house that they shared with their landlord, Mr. Wilcox, and four refugee women, including one of Robert E. Lee’s nieces. According to Mary Lacy, the “four ladies in the house [are] beautiful enough to make the reputation of a town, much less a house.” Because of the demand for housing and food, their landlord had raised their board twice within the past year, leaving the family “in somewhat of a quandary what to do,” as on her husband’s modest ministerial salary they could not “afford to board at this rate.” They felt inclined to move but could not find any less expensive housing or board in Warrenton and “where else to go we are perfectly at a loss.” Like many refugees, Lacy believed that they could save money were they to procure housing that allowed them to feed themselves rather than boarding at another’s table, noting that “I am very anxious to go to housekeeping, if we only knew where to go.” She wondered if they could move to Raleigh, where they had lived prior to Reverend Lacy’s tenure as Davidson College president, but her husband’s ministry in Warrenton prevented that. Mary Lacy expressed to her stepdaughter that “I hope the way will be opened for us to go to some cheaper place.”54

Three months later, in October 1862, Mary and Drury Lacy were informed by their landlord that board would again be raised, this time by an additional thirty dollars per month. This third rate hike pushed them to leave Warrenton, as “it is now higher than we feel willing to pay & . . . it is higher than we are able to pay.” Rev. Drury Lacy packed his books and prepared to find a new home. Mary Lacy wrote to her stepdaughter that although they had decided to leave, “we do not know where we shall go.” Even though Warrenton had been her home for only slightly more than a year, Mary Lacy felt a sense of loss at the prospect of moving, noting that “Warrenton is one of the most charming little villages I know & I shall regret leaving it extremely.”55

The rising cost of food and housing, Reverend Lacy’s work, and the threats of Union incursions into the eastern Piedmont left the couple wandering throughout the remainder of the war. After leaving Warrenton, Reverend Lacy took a position as a hospital chaplain in Wilson, sixty miles south of Warrenton and closer to Union forces stationed at New Bern, Washington, and Plymouth. The location of their new home closer to the front lines initially concerned Mary Lacy, although she suppressed her fears, writing in July 1863 that “I used to be afraid of the Yankees coming to Warrenton (where there was not the slightest danger), but here where they can come at any time I scarcely feel a fear.” While she claimed that she did not fear a Union invasion, she did worry about the rising cost of housing and food in Wilson, noting that although “we are living in the plainest sort of way,” she feared that her landlord would “give us notice that he cannot keep us.” Only a couple of evenings later, while Mary Lacy walked with her husband in Wilson, they heard that Union forces had arrived in nearby Rocky Mount. The couple immediately prepared to flee Wilson. In “a fuss and excitement,” Mary Lacy packed a trunk with clothes, which she promptly sent to her stepdaughter in Charlotte. Reverend Lacy anxiously urged his wife to take their children to a safer location, although she decided to stay for the time being. Over the next few days, they received repeated warnings that Union soldiers could appear in Wilson at any time. Reverend Lacy eventually persuaded his wife to leave with the children for Warrenton. As their route passed close to areas Union soldiers were known to frequent, Drury Lacy waited anxiously to hear that his family had arrived in Warrenton.56

Mary Lacy returned to Wilson after the Union threat had passed, and the family continued to live in the shadow of the Federal army until November 1864, when they relocated to Raleigh. For more than two years, Mary Lacy had longed to move to Raleigh, where she believed that they would be safer. They managed to secure a house near the military hospital where Reverend Lacy had taken a position as a chaplain. After having lived as boarders with “two or three other families” in Warrenton and Wilson, Mary Lacy was glad to have a home of their own, though she observed that “it is very small & without any pantry, smoke house, or any place to store anything away. There are two rooms down stairs & two up, no passage & the stairs like a ladder.” Mary Lacy wrote to her stepdaughter that “I am might glad to get back to Raleigh & yet I fear we shall have a hard time to live here.”57

The experiences of Harriet Yellowley and Mary Lacy reveal the practical difficulties refugees faced securing housing. Many refugees discovered that providing enough food for themselves and their slaves was just as difficult as finding housing. The influx of white and black refugees into the region created unprecedented demands for food. Coupled with rampant Confederate inflation and shortages caused by Union blockade, even the wealthiest Confederate refugees had difficulties supplying their tables. One refugee concluded that the North Carolina interior had “too many servants & in consequence of such a high price of all edibles . . . [a] famine is approaching rapidly.” After the outbreak of yellow fever in Wilmington, another refugee wrote that “the bible tells us that before the end of the World we will have War, pestilence & famine the two first is upon us—& the other is fast approaching.” A refugee in Franklinton noted that “provisions [are] scarce and high.” Fayetteville became “crowded with refugees from down the river,” including many wealthy refugees who found “difficulty in procuring the bare necessities of life,” such that “corn bread formed the sole bill of fare at meals in families accustomed to comfort and even luxury.” A refugee in Hillsborough noted that “provisions [are] so hard to get & so enormously high. I give five dollars and a half for a bushel of meal, $1.30 for butter, & everything in proportion, & very scarce at these prices.” Even planters who managed to secure farms discovered that they could not produce enough for their slaves to be self-supporting. Many refugee planters concluded that slave ownership had become more of a liability than an asset. One Confederate military official observed in 1862 that refugee “Negroes, who, from being producers, became consumers and add to our calamities.”58

By the end of 1862 the North Carolina Piedmont had been transformed by the arrival of tens of thousands of refugees. Many refugees reconciled themselves to the fact that they could not return home until after the war ended. A homesick refugee from Virginia living near Raleigh recalled the last time she saw her home: “It never appeared more beautiful, never seemed more dear than when we left it, not knowing whether we would ever behold it again. We gazed through blinding tears, until the tops of the lofty oaks were lost in the distance, thinking of how the feet of the foe would desecrate every spot, and his hands delight to spoil whatever was dear to us.” They had planned to return home as soon as the danger had passed, but “weeks have lengthened to months, and months into a year.”59 Unable to return home, they had become permanent refugees in Raleigh. Like the refugees on North Carolina’s coast, Piedmont refugees greeted the end of 1862 with trepidation and fear, while at the same time laying the groundwork for refugee communities that would last for the duration of the war.