TANZANIA & SURROUNDING TERRITORIES

It had been one of those hot and humid days in southern Tanzania and, as the lowering sun set the western clouds ablaze, the temperature showed no sign of dropping. The villagers noted that the lion they’d spotted in mid afternoon was still there, 500 metres (550 yards) away, head resting on its front paws. They weren’t particularly worried because the big cats – sometimes as many as a dozen – often passed by. Sometimes quite near. If they showed an inclination to go towards the cattle kraal, the men would rush at them shouting and banging anything that came to hand, and the dogs would go frantic. The lions would then move away.

And this lion showed no interest in the kraal.

Nevertheless Aiha Iddi called her four small children inside. It would soon be dark anyway and, once the sun goes down, few villagers venture out of doors.

Aiha’s husband, Mizengo, a woodworker, did not share his wife’s concern. There had been a man-eater 20 kilometres (12 miles) away near Kwtende in the west, where a young goatherd had been taken. But that was two weeks earlier. The lion was said to have moved even further west towards Nampungu where it killed a woman. This was some distance from where the Iddis lived south of the A19 road that runs from the interior to Lindi on the coast.

Although Aiha would have preferred to close the heavy sliding door, Mizengo felt it safe to leave it open to allow the evening breeze to cool the hut. The family slept on a wide, slightly raised platform strewn with three blankets on a thick pad of cardboard packaging. When there were man-eaters about, Mizengo would keep the door closed and, if he needed to urinate, he would do so rather noisily in a bucket inside the hut. So would everybody else. Aiha slept between her children and her husband who, a metre away, slept nearest the door.

When the family retired that night, Aiha was restless. One night two years back she had lost a younger sister to a lion, and the poor woman had screamed for some time after being carried off. Aiha still had nightmares about it.

In one of Aiha’s waking periods she heard her husband take a deep breath – that’s how she recalled it later. She thought little of it until, after a few minutes, she rolled over and reached across but Mizengo was no longer there. She listened but heard nothing and assumed he’d gone outside to relieve himself. Then she became aware that her arm was damp. Rubbing it, she instinctively knew it was sticky with blood – there was a pool of it where her husband had been sleeping. The children slept on but Aiha became aware of a sound well beyond the door that made her hair stand on end – the unmistakable sound of a lion feeding.

It was later assumed that her husband had been seized by the throat, hence no cry, and silently lifted clear of the bed. The village woke to Aiha’s screams. A single torch beam flickering from a nearby doorway settled on a gruesome sight.

Some bolder villagers rushed out shouting. The dogs, barking frenziedly, made half-hearted rushes at the cat. Somebody picked up a brand from the cooking fire and hurled it. The lion, in no great hurry, picked up Mizengo’s body as if it were a piece of rag and walked off into the night.

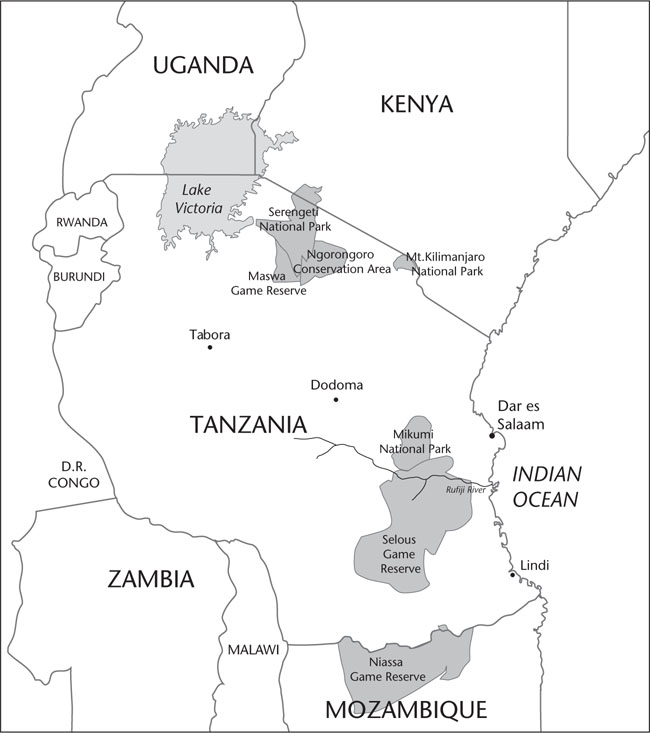

The incident took place in that belt of land sandwiched between Tanzania’s Selous Game Reserve to the north and the Ruvuma River, which marks the Mozambique border, to the south. On the south side of the Ruvuma is the Niassa Game Reserve. The two game reserves – each bigger than Switzerland – are the two largest in the world. Between the two is a 160-kilometre-wide (100-mile) corridor, along which elephants and lions and other wild animals travel, sometimes passing through some of the 27 villages. The region has the world’s highest incidence of man-eating – more than 500 victims have been killed by lions alone in the last few years. It is also notorious for crocodile attacks, mostly on women and children, because they are the ones who draw water from the river and streams.

Hyaenas and leopards also take people from time to time. Many say the elephant is the greater nuisance because a herd can, overnight, wreck a village’s entire crop of maize or cassava, leaving scores of people on a starvation diet. They sometimes raid the grain storage bins after harvest time, when it is too late to plant again. They also kill. They mostly kill men because it is mainly men who venture far and who move about after dark. Many are killed trying to scare elephants off when they threaten the community’s crops.

Yet, as is the case in most of Africa, these villagers have had no say in how wildlife in their region is managed. Wild animals, they will tell you, belong to the government.

North of the Limpopo, most of Africa’s large mammal species share their habitat with humans. Only a fifth of Africa’s wildlife is inside protected areas. And, while the presence of potentially man-eating lions or crocodiles adds a tingle of excitement to the foreign visitor’s experience in Africa, it is the bane of many who live there.

The majority of Africans are totally unaware of the economic benefits of wildlife, yet the national and regional income from wildlife is supposed to trickle down to the people. In much of Africa, it trickles up.

Vast areas of Tanzania, including the Selous Game Reserve, are still prime examples of wild Africa. Tanzania has some of the best virgin landscapes that remain of this magnificent continent. Mainly because the country is so poor, its beautiful reserves are still more or less as they always were – for instance, the Serengeti and Ngorongoro Crater – and the uniquely rich biodiversity is intact. But there has been a price and the price is borne to a large degree by the surrounding villages.

There are varying statistics regarding how many people are killed by lions in Tanzania. According to Professor Craig Packer, who heads the Lion Research Center at the University of Minnesota’s College of Biological Sciences, 563 Tanzanians were reported killed by lions north of the Ruvuma River between 1990 and 20042. An often-quoted number is 200 deaths by lions a year (reliable statistics are hard to come by in Africa’s developing states; in many cases deaths are not reported because villagers attribute them to supernatural forces). A few specialised man-eaters have been identified, including the notorious Osama (named after Osama bin Laden) that ate at least 34 people and terrorised thousands along the Rufiji between 2002 and 2004.

Packer found that more people are killed and eaten by predators wherever the population of smaller animals – the preferred diet of all the cats – had been reduced by bushmeat hunters and poachers. Paradoxically, there is another spike in man-eating when bushpigs are abundant. The reason for this is that bushpigs raid croplands and so villagers will sleep out in the fields in flimsy shelters to protect their crops – ‘and that is where [lion] attacks take place and where lions learn to eat people’3.

Hyaenas and leopards also take a steady toll – steady enough to keep many villages in a state of anxiety.

Most deaths are in the south of Tanzania, which has Africa’s largest population of lions, and most victims are taken at night when they are sitting in temporary shelters, either protecting their food storage bins from elephants or, especially at harvest time (March and April), protecting their crops from bushpigs. South of the Ruvuma River lies Mozambique whose northern province, Cabo Delgado, is where carnivores – mainly lions – in and around Niassa Game Reserve in 2008 and 2009 are known to have killed 116 people. In this same province crocodiles take scores of people a year. It was pointed out that this was only ‘a partial survey’ in a small section of a large region, and that in many cases attacks were not recorded because the locals believed the victims had been taken by ancestral spirits. Further south, in August 2009, the situation was worsening in Mozambique’s central provinces Manica and Sofala, to the point that it was becoming a political issue4. The governor of Manica, Mauricio Vieira, announced that a militia had been put together ‘to protect people and their property’. It comprised 66 trained community wardens and ‘six brigades’ aided by five hunters. National president Armando Guebuza saw fit to attend the extraordinary session of the Manica provincial government and said it ‘made no sense that Mozambicans were still being killed by wild animals’.

Packer says that in two years (July 2006 to September 2008), of 265 Mozambicans who were killed by wild animals, 31 were killed by elephants, 24 by lions, 12 by hippos and one each by buffalo, snakes and baboons and most of the rest by crocodiles. Sixty-one were killed by ‘species unknown’5. Many cases are not reported because people have little or no incentive to report them and because the deaths are attributed to witchcraft. And in even more cases people – possibly victims of predation – simply disappear and, if their disappearance is recorded at all, they are merely listed as ‘missing’.

An indication of how bad the situation is in northern Mozambique came in a 2010 FAO (Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations) report citing various research papers. In Cabo Delgado Province, between 1997 and 2004, 48 people were killed by lions and 70 more in 2000 and 2001. Forty-six people were killed in Muidimbe district on the Makonde plateau in 2002 and 2003 and in the Niassa Reserve ‘at least 73 lion attacks, with at least 34 people killed and 37 injured since 1974 and at least 11 people killed and 17 injured since 2001’6.

Dr Jeremy Anderson, who has spent many years studying the situation, believes crocodiles alone kill 300 Mozambicans a year – more than double the official estimate7.

The rural African’s main interest in wildlife is meat – a point that was stressed in the 2009 FAO report8. The report focused on the ‘human-wildlife conflict’ (HWC, an acronym that is increasingly being heard at 21st-century conservation conferences). An important step towards finding how rural dwellers perceive wildlife, it was published in the hope of finding ways to alleviate the suffering being experienced in Africa where people compete for living space with potentially dangerous animals. The idea is to achieve some sort of conciliation between humans and wild animals. Wildlife, after all, is the mainstay of Africa’s highly lucrative tourist trade and is a major source of protein. In the remote parts of Africa it is the only potential source of income for rural communities.

Poverty is a factor in man-eating. The FAO report gives the example of fishermen so desperate for food that they knowingly risk crocodile attacks every day by wading into rivers or lakes. Shortly after the FAO report was published, a grim example was announced in Harare, Zimbabwe. In a period of two weeks eight people were killed by crocodiles while illegally catching fish in Lake Chivero, not far from Zimbabwe’s capital. The poachers feed their families with the fish and sell the surplus door to door. Their deaths failed to deter other destitute poachers from wading waist deep into the lake with their fishing spears9. Another report said that, in 51 cases of crocodile attacks in neighbouring Mozambique, 39 of the victims had been fishing and presumably knew they were taking risks – although they might have underestimated the probability. They did so in the absence of alternative foods or livelihoods10.

Poverty sometimes makes it impossible for villagers to protect their crops with elephant-proof barriers or lion-proof fences, or even for those working in the veld to afford shoes or boots or long trousers to protect their legs against snakebite. It is estimated that snakes in barefoot Africa kill at least 20 000 people a year11.

One of the most respected voices in East Africa is that of Dr Rolf D. Baldus12 who has more experience than most when it comes to HWC in Tanzania, where he was in wildlife management for many years. It is a region of Africa he loves dearly. He believes that, unless communities in the major wildlife areas of Africa are allowed a significant say in the management of the wildlife around their villages, they will see no point in conserving it and Africa’s famed biodiversity will become greatly reduced. He is a strong advocate of sport hunting as a means for communities to derive sustainable income from the wildlife around them, arguing that it not only brings in millions of dollars a year, and a lot of it directly to the communities, but it does more to conserve wildlife than any punitive measures can achieve. Once lions, for example, have a value – and hunters pay tens of thousands of dollars to shoot just one trophy lion – the locals no longer poison and trap them. Kenya, under pressure from animal rights groups and other well-meaning overseas pressure groups, banned hunting more than 30 years ago, since when it has experienced an alarming decline in lion numbers. Since lions in Kenya no longer have a material value, cattle owners now regard them as vermin. Although they are not allowed to shoot them, not even to protect their cattle, many are killed – a surprising number by spears – and left to rot.

In 2007 Kenyan land-use economics researcher Mike Norton-Griffiths chastised the government-controlled Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS), virtually the sole owner of all of Kenya’s wildlife, and Europe’s wildlife societies for the lack of realistic and effective governance regarding wildlife13. Kenyans who live among wild animals have little chance of being heard on HWC issues and no opportunity to earn revenue from the animals they are expected to conserve. He says landowners have no rights regarding wildlife and receive no compensation for destruction and damage to life and property. The West’s wildlife ‘protectionists’ are ‘deeply at fault for they are too focused, obsessed even, on topical single issues that rarely concern the economics of producing wildlife’14. Norton-Griffiths suggests that animal lovers in Europe are ignorant of the market forces that determine land use and production decisions in rural Africa ‘and they are often too reticent in challenging the government over policy issues’. We can add that the KWS is equally reticent in challenging its funders in Europe, who then attach strings to their funding – strings that reflect the desires of TV watchers in middle-class European homes, rather than the needs of people living in the real Africa.

Rolf D. Baldus has campaigned for years for communities in wild Africa to be in charge of their own natural resources and to be empowered to host overseas hunters, but under strict ethical conditions.

It has been found that most attacks on people by lions, leopards and hyaenas, and on their crops and livestock by elephants, hippos, buffalo and bushpigs are concentrated around the game reserves. The people’s reaction is to retaliate, especially if they had been removed from ancestral lands to make way for the reserve, which is often the case. Many feel justified in killing or indiscriminately poisoning wild animals, as well as in poaching inside protected areas. If the government fails to protect rural dwellers, then they will protect themselves in any way they can. A particularly interesting example was a few years ago when the people of Makoko village on the western border of the Kruger National Park were found ‘roasting meat of four lions’ that had come from the park. The lions had come under the fence and killed eight cattle. The villagers had then removed 500 metres (550 yards) of the park’s high multi-strand fence and used it to protect their village and crops15.

Packer says the term ‘wildlife-damage’ is nowadays so much in use that there’s a tendency for rural dwellers to blame predation and marauding on wildlife in general and ‘to take it out on even beneficial species’. He shares Baldus’ view that adverse perceptions of wildlife are particularly pronounced near game reserves, where wild animals inflict daily costs on local communities – costs that are being increasingly resented16.

This view echoes a 2002 report on elephant–human conflict in Mozambique’s Niassa Game Reserve, which discussed how elephant–human conflict had become a significant problem, not only within the reserve but outside the reserve in nine of the 15 districts of Mozambique’s far north. It had become, according to the report, a priority issue for the provincial administration and incidents were rising. A provincial meeting of administrators and chiefs on local government ‘was largely hijacked by discussions on elephant crop damage. In Nipepe district it was estimated that 18 tonnes of maize had been lost this year in the fields around the district centre and this had contributed to the recent riots in which the community attacked the administration.’17 In the following decade various FAO reports indicated the problem was still unresolved18. Such reports make it clear that the future of conservation will depend on the relationship established by the wildlife authorities and those bearing the brunt along the front line. There is a lot of ground to be made up because most rural dwellers, understandably, regard elephants and lions only in terms of the damage they do to their crops and stock, and they bitterly resent being powerless to retaliate.

There is a consensus among those scientists and non-government organisations involved in redressing the situation that, whatever the answers are, they must not come as top-down edicts but as strategies jointly created with the communities themselves. Wildlife-management agencies, donor groups, conservation scientists, land-use planners and developers and law-enforcement agencies are all in their various ways responsible for the situation. Nor are the communities themselves blameless.

In South Africa, which is far more developed than the rest of sub-Saharan Africa, man-killing and man-eating is on a small scale but is increasing, and even the leopard appears to be changing its spots. The leopard has been a rapacious man-eater in India and sometimes in Africa, but prior to 1990 I had not heard of a single case of man-eating leopards (as opposed to man-killing) in the whole of South Africa. And then a series of incidents began just over 20 years ago19. It was around this time that lions in the Kruger Park began living off Mozambican border-jumpers who were fleeing the internecine war to the east. Leopards might also have turned to man-eating at that point, having discovered how weakened refugees travelling by night were easy prey.

But is there something else afoot?

There have been suggestions that we are witnessing a global heightening of aggression among large animals towards humans. Richly deserved perhaps, when you consider what humans have done to Africa’s wildlife over the last three centuries. In 2008 London’s Daily Telegraph, reporting a killer elephant terrorising a village in Assam, northeast India, made this observation:

Elephants haven’t always behaved like this. But in recent years, in India and all over Africa, too, some menacing change has come over them. And not just elephants – it’s almost any species. This disquieting pattern has only recently been detected, in part because it is so disparate and weird. But it’s now widely accepted that the relationship between humans and animals is changing.

One of the world’s leading ethologists [specialists in animal behaviour] believes that a critical point has been crossed and animals are beginning to snap back. After centuries of being eaten, evicted, subjected to vivisection, killed for fun, worn as hats and made to ride bicycles in circuses, something is causing them to turn on us.

It’s happening everywhere. Authorities in America and Canada are alarmed at the increase in attacks on humans by mountain lions, cougars, foxes and wolves. Romania and Colombia have seen a rise in bear maulings. In Mexico, in just the past few months, there’s been a spate of deadly shark attacks with the LA Times reporting that, ‘the worldwide rate in recent years is double the average of the previous 50‘. America and Sierra Leone have witnessed assaults and killings by chimps who, according to New Scientist, ‘almost never attack people’. In Uganda, they have started killing children by biting off their limbs then disembowelling them.20

The writer’s implication that there is some sort of international telepathy among predators seeking revenge on their tormentors is pure fantasy. Yet there is no doubt that incidents of human-animal conflict are increasing throughout Africa and across India and North America. On Lake Victoria in East Africa, where crocodiles were so docile during most of the 20th century that local people had no fear of them and even swam among them, crocodiles now kill people regularly. At Bwonda on Lake Victoria, hippos are increasingly attacking homes and killing people. Elephants, where they still exist in large numbers, are showing increased aggression. There’s evidence that today’s elephant populations are suffering from chronic stress brought about by prolonged habitat reduction, ceaseless poaching, culling and mass translocations. People who have had experience with these intelligent creatures know that elephants, like whales and dolphins, are sociable animals with strong family bonds and have an ultra long-range communication system. As a result dealing with the elephant overpopulation in parts of Southern Africa is proving to be extremely complex21.

Human-wildlife conflict is receiving unprecedented publicity, partly because the communications revolution is bringing stories from places that, in the past, were barely covered by the news media and because reporting has become far more penetrating, comprehensive and analytical – and, one supposes, people are becoming more interested in what’s eating them.

As C.A.W. Guggisberg put it:

It is easily understandable that human imagination is always stirred by stories of man-eaters, be they big cats, wolves, crocodiles or sharks. One experiences a by no means disagreeable shudder – provided there is no chance of being chosen as the next meal – as well as a feeling of outraged amazement that lowly animals can have the effrontery to gobble up the ‘lord of creation’. From this feeling probably stems the strange effort to show the man-eating habits, especially of the big cats, as something absolutely out of the ordinary – something almost monstrous. Thus a very eminent scientist compares the man-eating lion with a homicidal maniac. I admit that I am unable to follow his reasoning … a man-eater does not harm individuals of his own species. He kills other animals, only those victims are for once not zebras or wildebeest, they belong to that strange species known as Homo sapiens. Why should this be so monstrous?22

The 2009 FAO paper mentions how some people blame colonialism for ‘ruining traditionally harmonious relations between wildlife and local people’. But was there ever a harmonious relationship? There might have been, in the sense that we ate wild animals and wild animals ate us, but that is poetic rather than harmonious.

I am being facetious: the fact is there are, as we shall see, many instances of harmonious relationships. And there are even instances where rural dwellers have philosophically accepted that it is their fate that predators would eat them and pachyderms would trample their crops. Many people to this day rationalise it by blaming deaths from man-eaters on the supernatural. Many will not kill man-eaters for this reason.

It is hardly surprising, as human numbers grow and as people and wild animals compete for space and food, that the conflict has become more bitter and bloody. In 2008 in Tanzania’s Rombo district, which includes a great deal of Mount Kilimanjaro, 20 people were killed by elephants. Yet that year was shrugged off as just an ‘average year’23. During the year this region suffered crop damage to the tune of $500 000, which for a mainly peasant population is a considerable amount.

It is difficult for conservationists living in Baltimore or Wolverhampton to visualise what it is like for villagers during the night to hear a herd of elephants destroying their crop of cassava or maize, just before it is ready to harvest – which is when elephants are most attracted to a field. For farmers and their families it means months of hunger, even starvation – having to ration each day’s food carefully. This explains why so many villagers try so desperately to defend their fields. We cannot blame the elephants – there’s not an ounce of malevolence in an elephant under normal circumstances – but to the subsistence farmer the elephant can spell death.

Most African countries do not pay compensation for damages caused by wildlife. They argue that a compensation scheme can do little to reduce the conflict and might even encourage communities to relax precautions. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) African Elephant Specialist Group and the Human-Elephant Conflict Task Force recommended against compensation for elephant damage, arguing that it can at best address only the symptoms and not the causes. Some governments, which have tried and abandoned compensation schemes, prefer to assist villagers by improving their defences.

The 2009 FAO report said:

The failure of most compensation schemes is attributed to bureaucratic inadequacies, corruption, cheating, fraudulent claims, time and costs involved, moral hazard and the practical barriers that less literate farmers must overcome to generate a claim. Additionally, they are difficult to manage, requiring reliable and mobile personnel and logistics to verify and objectively quantify damage over wide areas.

A study of elephant damages in the region of Boromo (Burkina Faso) in 2001/2002 revealed that 98 per cent of the damage caused by elephants was not reported to the administration because the farmers knew there would be no compensation.

In Namibia, the Ministry of Environment and Tourism subsidises funeral costs (approximately US$710 per victim in 2007) for people killed by elephants, crocodiles and hippos ‘under conditions where the affected persons could not reasonably have been expected to defend himself or to avoid the incident, and where the family has to incur costs for a funeral’. In Ghana, while no compensation is paid for crop damage by wildlife, the Wildlife Division and the Ministry of Food & Agriculture assist victims to adopt both mitigation and crop-improvement techniques. In 1991 in Burkina Faso, the victims of elephant crop-raiding were preferentially contracted as workers to maintain the infrastructures in the Deux Balé Forest Reserve. This operation involved 127 farmers who received about US$40 each – the equivalent of three 50-kilogram (110-pound) bags of millet. ‘This compensation scheme was very much appreciated and sensitized the villagers to conservation.’24

Either we co-exist with wildlife or we continue to assist calculatedly in the extinction of the world’s lions, tigers, leopards, jaguars, elephants, rhinos, bears, gorillas and wolves. A positive step forward came in Durban in September 2003 at the IUCN’s fifth World Parks Congress. A 30-person workshop, comprising conservation scientists, field workers, sociologists and other disciplines from across the world, was convened by the IUCN to examine the topic ‘Creating coexistence between humans and wildlife – global perspectives on local efforts to address human-wildlife conflict’. The workshop’s deliberations were presented to the nearly 3 000 delegates at the congress – a congress that, in retrospect, has proved to be a landmark event in HWC. It addressed not just Africa’s HWC problems but also those in other parts of the world, for instance problems with bears in North America, jaguars and crop-raiding animals in South America, India’s tigers and elephant, crop-raiding gorillas in Uganda and dingoes in Australia. Right across the globe, as populations grow and protected areas become hemmed in, there are conflicts between humans and wild animals. What was significant at the congress was that, generally speaking, few saw the rifle as a solution and all saw the importance of conserving what is left of the world’s wildlife and wild places. Scientists, sociologists and field workers sought to find some sort of strategy towards reconciling the aims of conservationists and the needs of those outside the reserves. The idea was to review progress and suggest a course for the next 10 years and beyond – 10 years being the gap between each World Parks Congress25.

The workshop defined the problem of HWC, saying that, as populations grew, incidents involving conflict were increasing in frequency and severity worldwide and were likely to escalate. HWC involves more than problems with man-killers. It involves crop damage; the death or injury to domestic stock; the loss of crops and the consequent anxiety and frustration. HWC involves conflict not just between humans and wild animals but between humans and humans. Measures to counteract it can be divisive among communities and can involve retaliatory measures by desperate villagers, not only against problem animals but also against sluggish authorities who are often perceived as being unsympathetic. Generally, rural communities, especially in Central and East Africa and the Indian sub-continent, are powerless against, for instance, elephants and the big cats, either because they do not have the weaponry or because the law forbids them to take physical action. In such cases resentment builds up and the communities feel, understandably, that the authorities favour wildlife over human well-being, which in certain regions is probably true. In this situation are the seeds of bitter strife sown. It could in the long run be the death of Africa’s unique biodiversity.

If those who took part in the Durban congress came away with a common perception of the problems and solutions of HWC, it must have been that the situation is far more complicated than anybody imagined. There are few simple answers – just a lot of possible measures involving national, regional and local politics; cultural idiosyncrasies; economics; sociology; education, ethology; psychology; land-use planning; policing; climate change; the possible extinction of endangered and threatened species and a plethora of other biological challenges. And, whether in Asia, South America or Africa, the weighting of these factors differs, not just from region to region, but from locality to locality, even village to village and sometimes among those within a village.

There are also prejudices. Stray cattle might cause more destruction in a field than elephants. But the resentment against the marauding elephant is bitter indeed for the simple reason that the community has no control over the elephant, whereas straying cattle would have been their own fault.

The park conferences are important in more ways than one. A common characteristic among scientists who enjoy working in the field and people such as game rangers is that they often work in isolation and, indeed, are frequently loners by choice, who abhor having to visit cities and put on suits and becoming involved in formalities. Much of their knowledge is never disseminated because they get so few opportunities to engage with other disciplines. The Durban congress and subsequent sponsored seminars brought many of them out of the bush to mix with others, and it provided opportunities to add to the global ideas exchange. The deliberations indicated that what works, for instance, in counteracting crop-raiding baboons in South Africa’s Western Cape might well have application in India or Brazil with quite different species. It was perhaps inevitable that the congress’ most important conclusion was that constant dialogue and the global sharing of information was essential. With the revolution in electronic communication, this was now possible. Three years later, and arising directly from that suggestion, the Human-Wildlife Conflict Collaboration (HWCC) was established in Washington, D.C. In November 2006 more than 50 conservation professionals from 40 different institutions across the world met there and resolved to form an ideas exchange. One hundred organisations now participate in this global network and the HWCC has a two-person secretariat and has established a web-based resource. It also offers courses, among them a three-day training programme in ‘conflict resolution leadership’ techniques, and it processes a three-day critical skills training programme for all conservationists dealing with HWC26.

The acute situation in some regions of Africa has to an extent been engineered. In trying to conserve Africa’s unique variety of wildlife, governments have been compressing wildlife into isolated ‘island’ reserves – and there’s then a tendency to pave and plough in between – right up to the fences. Little room is left for buffer zones where land owners can erect lodges or conduct hunting safaris and there are few uncontested corridors for animals to move from one protected area to another. There are now attempts in Southern and East Africa to create protected corridors joining national parks and smaller reserves into contiguous zones, so encompassing a maximum variety of habitats and thereby preserving a maximum variety of plant and animal species. As far as conservation, biodiversity, job creation and land-use planning go, this is fine – but it might also exacerbate HWC. ‘Wildlife corridors’ are sometimes possible.

This is certainly so in Tanzania where, in 2012, there existed more than 30 opportunities to link protected areas, none of which was likely to exist in a few years’ time. There is plenty of scope too for lucrative buffer zones on community-held land, particularly outside the Selous Game Reserve, but the Tanzanian government, riddled with nepotism and corruption, will not release its grip on the multi-million-dollar income from the hunting industry27 and it brooks no opposition from outside the reserve. The wildlife and tourism ministry wants to have its hands on all hunting and photographic tourism and, in particular, it does not want to share proceeds from hunting on village land with the villagers. It would also like to control private tourism operators. Hunting regulations require all companies involved in tourism in any wildlife area – including non-protected areas – to obtain permission and licences from the ministry. Yet the ministry seems incapable of handling this. One community that wanted to build a tourist lodge waited 10 years for permission.

The government’s attitude has caused massive retaliatory poaching and, according to the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), the Selous and Mozambique’s Niassa Game Reserve are today’s major source of illegal ivory being shipped out of Africa.

The Kruger Park, which is the size of Belgium or Massachusetts, long ago took down the barbed wire and electrified barrier between it and the thousands of square kilometres of private game reserves on its western flank. More recently it did the same on its eastern side, thus incorporating within the South African protected zone a vast portion of protected Mozambican bushveld, to form the Great Limpopo Transfrontier Park. There has been talk of developing a belt of reserves extending westwards up into the high Escarpment, which divides South Africa’s temperate Highveld from the hot Lowveld. There has long been talk of linking the scattered reserves of Zululand28 (already linked from Maphelane to the Mozambique border) northwards into Mozambique. Then, via a chain of reserves, to the Great Limpopo Transfrontier Park and even further northwards (with Zimbabwe’s cooperation) to the Zambezi River. It is feasible then to link this complex – which would be the largest protected wildlife area on Earth – westwards along the wild valleys of the Limpopo and Zambezi to the large desert reserves in Namibia and Angola, offering unrivalled opportunities for safari lodges, wildlife viewing, birding, hiking, motoring, hunting and fishing (both fresh water and marine).

It is within the realms of possibility to link Southern Africa’s parks to Kenya and Tanzania – a concept first articulated by the South African statesman Jan Smuts in the 1930s. When Dr Richard Leakey revisited South Africa in the post-apartheid era and I introduced him to a meeting of the Institute for the Study of Man in Africa, I mentioned this and suggested that existing villages could be incorporated because to tourists they were a fascinating part of natural Africa. I was surprised by Leakey’s violent reaction. He said, ‘We don’t want to be stared at like animals by tourists!’ This was hardly a valid objection – it is rather like villagers in England’s protected Cotswold Hills or on America’s Appalachian Trail resenting being part of those heritage areas.

There’s also talk in the Peace Parks Foundation29 – though nothing more than that so far – of joining the huge Selous Game Reserve in Tanzania to Mozambique’s Niassa Game Reserve incorporating the 160-kilometre-deep stretch of community land in between30, creating a trans-border reserve of around 110 000 square kilometres (42 480 square miles). But, as long as those living outside develop up to their boundary fences, so the propensity for conflict remains and grows. Many reserves are already bordered by intensive agriculture and in places by dense human settlements. The Kruger Park’s southeastern flank is an example. The division is absolute: two different antagonistic worlds separated by barbed wire – the front line.

Mothers living outside Pilanesberg National Park31 not far from Johannesburg warn their children that if they misbehave they’ll be put over the fence. I doubt that this threat (which is obviously not meant seriously) is confined to those living around Pilanesberg but, in populated areas with an isolated ‘island reserve’ in their midst, it is leading to a generation of children growing up to view wildlife more with terror than wonder. The 2009 FAO report refers to rural dwellers ‘hating’ wildlife – especially elephants32. But we must be cautious about interpreting that as Africans ‘hating and detesting’ elephants or lions. There are significant and hopeful inconsistencies. In Uganda in 1999 a survey seeking rural views on the best way to deal with ‘problem’ lions found, surprisingly, only 37 per cent (out of 156 respondents) felt lions should be exterminated. An almost equal number (35 per cent) said a game-proof fence should be erected around protected areas. The rest felt people should be taught how to avoid lions. In Tanzania’s Rufiji district villagers who had, in a few short years during the 1990s, suffered 92 lion attacks, nevertheless had a ‘high tolerance for lions because the lions helped control the bush pig population’33.

In Namibia, Garth Owen-Smith, who has an intimate knowledge of the situation in the arid but intensely beautiful northern region where elephants share precious waterholes with cattle and humans, says resentment flares when they damage windmill water pumps and tanks and many elephants are killed in retribution. In contrast he writes of an old man, nicknamed Old Kaokoveld, who complained bitterly of the damage done by elephants in his area. Although there was a spring nearby, elephants chose to drink from the reservoir next to his house. Owen-Smith suggested the only solution was to have them shot, to which the old man replied, ‘No one must shoot my elephants!’ Owen-Smith, a courageous conservator, commented, ‘At the time I started to think that getting the local communities’ support for stopping [elephant] poaching was a hopeless task but Old Kaokoveld’s response made me believe it was possible. The key was – whose wild animals were they?’34

That unresolved question alone deserves the undivided attention of the IUCN’s future World Parks Conference.

Since the Durban accord there have been a few tentative signs from the usually sluggish and often devious government bureaucracies that their political consciences are being pricked regarding protecting villages and sharing with them the economic benefits coming from the natural resources around them. The Tanzanian government held a national workshop in 2009 ‘to prepare a national action plan for lion and leopard’ and made noises about letting communities in on wildlife management. But progress in the field is hard to find. The wildlife ministry still stifles private enterprise. A share of the millions of dollars from hunting inside and outside of the Selous Game Reserve – including on village land – does not go to those along the front line.

The former Zambian government frequently vowed to step up efforts to see that rural dwellers helped in the control of problem animals and often appeared to be trying to devolve power regarding wildlife to local communities. It achieved almost nothing and in September 2011 was defeated at the polls. The new president, Michael Sata (a former policeman and trade unionist), immediately disbanded the board of the Zambian Wildlife Authority (ZAWA) and also released 670 prisoners, who had mainly been convicted of poaching. He claimed that ‘the previous administration valued animals more than hungry humans’35. ZAWA provides national parks with armed scouts and rangers.

Sata warned during the opening of parliament that he would invoke bold measures: ‘In order for us to preserve our wildlife for tourism we must also put measures in place to control the problem of human-animal conflict in game management areas which has led to increased levels of hunger and poverty among our people.’ He announced, ‘I have today dissolved the ZAWA board and I have to look at it, to reconstitute it.’

Sata’s move shocked many and was widely seen as a green light for poaching. In the following hiatus two game guards were shot dead and a scout post was put to the torch, though the motives were unclear. The new Minister of Tourism, Environment and Natural Resources, Catherine Namugala, found it necessary to state that the new government would ‘deal strongly with individuals caught for poaching’. But Sata’s announcement was largely seen as an understanding that the law would be lenient towards those who hunt bushmeat to feed hungry families. Indeed some of the freed prisoners were mothers.

The Cape Times’ Tony Weaver, who knows Zambia well, claimed ZAWA’s board was dysfunctional and corrupt anyway and that the previous government fell because of corruption and gross incompetency:

Of those released only a few are commercial poachers. Most are villagers living on customary land; land supporting the wildlife owned by government from which they receive no benefit, being abused by the agents of the state for eating some duiker meat, and living unprotected from the depredations of wild animals. Zawa has been implicit in the bushmeat and (illicit) ivory trade in Zambia for 30 years or so and [protective of] the ‘Big Man’ networks… Sit back and watch a lit candle in the African dark.36

Other African governments have announced intentions to decentralise wildlife controls, but such statements of intent have been heard for the past 20 years. Judging by the lack of follow-up, the pronouncements appear to be aimed at appeasing overseas conservation lobbies and international donor agencies. Very little has been achieved after years of talking.

In 2011 there was an incident in South Africa that was a warning to all involved with HWC. A frustrated community in Zululand breached the front line. Rural dwellers tore down the fence of one of Africa’s prime game reserves – Ndumo on the Mozambican border, which is a beautiful wetland where five per cent of the world’s bird species can be seen. They moved in with their cattle, chopped down trees and defiantly tilled the land for crops. The intervention of 50 policemen failed to budge them. The standoff was solved diplomatically but it was a shot across the bows.

We then have to consider the tourist element. Visitors, well protected in their vehicles, cross the front line daily in their thousands. In recent years ‘ecotourism’ and ‘adventure tourism’ have increased enormously because tourists want to get closer to the animals. They want to experience wilderness but, understandably, more and more want to do so on foot. They are willing to take chances; they are looking for thrills. Some merely want to regale their friends back home about their adventures; some are seriously passionate and very knowledgeable about wildlife and plants and are interested in the minutiae of the educated class’ growing enthusiasm for ecology. The trend towards hiking in the bush is excellent news for reserves – if visitors walk rather than use vehicles it means more tourists and less impact.

Since visitors want to see ‘the big five’, more and more small reserves are finding it commercially advantageous to reintroduce these animals. As a consequence the big five are today far more widely spread, especially in the southern third of the continent and most certainly in South Africa, than they were a century ago.

The danger to tourists is increased by the lack of suitable game rangers and game guides. Scientist and former game park warden Jeremy Anderson, with his 40 years’ experience as an international wildlife management consultant, mostly in Africa, says that many people have been elevated into the position of game rangers before they are adequately trained37.

The Kruger Park has run ‘wilderness trails’ for tourists for the last 30 years and Zululand’s reserves, which pioneered the concept, have organised trails on a daily basis for 40 years. Several visitors have been injured but not one has been killed inside these particular reserves, though there have been tourist deaths in the private reserves. The trails, relaxed affairs taking up to five days walking in areas untouched by development of any kind, are led, single file, by an armed ranger and followed by an armed assistant.

After a series of attacks on trails in 2004 the Johannesburg Star newspaper reported that ‘animal attacks are increasing as tourists dare to get closer to the animals. Already this year eight attacks by wild animals have been reported [on Kruger Park trails] while only five were reported in 2003 and three in 2002.’ Although none of these attacks was fatal, in 2009 the Kruger Park suspended some of its trails. This was shortly after a ranger, escorting eight hikers, was severely mauled after spotting a lioness with cubs just outside the Metsi-Metsi Trails Camp, not far from the popular picnic spot Tshokwane. Despite two warning shots, the lioness attacked but after clawing and biting the ranger she ran off. The tourists, after recovering from the shock and with a new ranger, continued their hike.

While there have been no tourist fatalities on wilderness trails inside national parks, it seems just a matter of time before there are. There have been plenty of close shaves, including when a Kruger Park white rhino – a normally docile animal – charged into a line of eight walkers, injuring two.

In many parts of Africa hiking in the bush accompanied by game rangers or guides has become a daily occurrence; tourists are sleeping in tents and even in the open in lion and elephant country. The new growth and expansion of wilderness trails has outstripped the availability of experienced rangers and guides. Gone are the traditional rangers who, in their long years of apprenticeship, patrolled wild regions on foot, sometimes alone for weeks on end. Gone, mostly, are the cool-headed dead shots who were allowed to lead wilderness trails only after they had experienced many encounters with big game. An essential part of their training involved tracking down and shooting an elephant as part of a culling operation. But trainee rangers today are merely required to have shot, accurately, a pop-up life-sized effigy. The question is how would they react in a dire situation? A friend travelling around Madikwe National Park38 in an open tourist vehicle noticed the ranger did not have a gun. The ranger explained he was waiting for a police permit allowing him to possess one.

Perhaps the most hair-raising of all groups who go into the bush are the television crews who put pressure on rangers to take them closer to animals. Jeff Gaisford, recently retired public relations man with Ezemvelo KwaZulu-Natal Wildlife, has had much experience accompanying TV crews. He explained how ‘old hand’ rangers would put them firmly in their place if they made demands that entailed undue risk, but ‘the youngsters’ often give in. ‘Heaven knows, I have had the same pressure on me when guiding some film crews – “make the animal move”, “get us closer so we can get a better shot”. And when the animal in question disappears in a cloud of dust or a great splash of water they complain, “Gee, a pity you were not more careful”.

‘The fact that there have been so few tourist injuries and deaths is an enormous tribute to the good behaviour of the animals.’39