It is attractive to draw the boundaries of psychiatry in terms of trying to remove psychological obstacles to the good human life. One danger is seeing the good life too narrowly. The idea might have stifling consequences—some modern equivalent of imposing “treatment” on gays. Can we answer the question “What is a good life?” without forgetting that it takes all sorts to make a world?

There is an influential idea in the debate about choosing children with some sets of genes rather than others. If children are to have a decent chance of a good life, they should have “an open future.” No one has a totally open future: we are all partly constrained by genetic, environmental, and other factors. But parents should not aim simply to reproduce their own version of a good life. They should leave children plenty of scope to shape lives of their own. A good life includes choices about how to live. We should not follow the Brave New World model of creating “happy” children living in a built-in prison. The idea of an open future applies to psychiatry too.

Aristotle needs to be combined with “experiments in living,” John Stuart Mill’s reminder of how open-ended the vision of the good life should be. What follows in this chapter is tentative: not a blueprint for “the” good human life, but suggestions about some strands in a good life. The account is shaped by obstacles found in psychiatric conditions. The strands selected here come in two groups. There are features of “me” that underpin a life a person is comfortable with. And there are things that help make a life add up to something, or have some meaning.

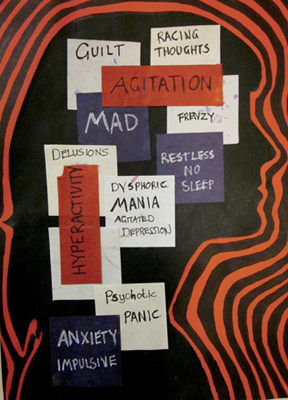

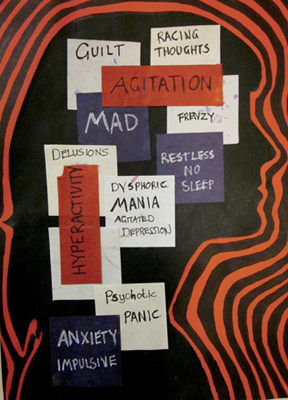

A good life is supported by certain features of a person’s psychology. One is being at peace with yourself. This is best understood by contrasts. It is what some of the artists in the Prinzhorn collection did not have. It is what John Clare missed: “I long for … / … sleep as I in childhood sweetly slept, / Untroubling and untroubled where I lie / The grass below, above, the vaulted sky.” Its lack is powerfully portrayed by Laura Freeman (Figure 20.1).

Figure 20.1: Laura Freeman, Thoughts That Go Through My Head during a Mixed Affective Episode. Courtesy of Laura Freeman.

Another strand is having a good deal of control over your own life. No one is fully autonomous. We have been shaped by so many influences outside our control: genes, family, friends, the time and place we live in, the pervasive influence of a culture, our education, the media, and so on. But most of us are not fatalists and know we still make choices and that these choices make a great difference to our lives.

This sense of being in charge of our lives, at least to some extent, can be diminished—sometimes almost to a vanishing point. Lack of control can come from poverty, political oppression, hierarchical conditions of work, cultural pressures to conform, oppressive families, and the disabling limits of some physical or mental disorders. Our control over our lives is only relative, but it matters enormously. This is central to the widespread and deep rejection of both Brave New World and the experience machine. There is also evidence that, where people’s work allows them little autonomy, the prospects for their physical health are poorer than for those whose position in the same profession gives them greater autonomy.1

A sense of inner peace and a degree of control are important foundations. But ideas of a good life often go beyond the foundations to what we can build on them. People’s hopes sometimes include the hope to have a life that adds up to something, that has some meaning. What does this come to?

The question “What is the meaning of life?” is sometimes asked seriously and sometimes ridiculed as pretentiously empty. What could possibly be the answer to such a question? It suggests that life is a puzzle to be decoded: the meaning of life to be interpreted like the meaning of a hieroglyphic. Like some hieroglyphics, life might elude our powers of interpretation. Or we might succeed in getting the answer. We might discover some plan of God’s in which we have a part. Or scientific discoveries might suggest that humans have a crucial role in the scheme of things. There seems no reason to think life contains some secret message for us to decode. Yet many people do want their lives have some meaning. This hope is better interpreted as wanting to make something of their lives.

Some of the most powerful reflections on people’s desire to give meaning to their lives came from a psychiatrist’s observation of himself and other prisoners in Auschwitz. Viktor Frankl described the psychological impact of the imposed suffering and degradation. The impossibility of knowing whether it would end in death or release, or of knowing when it would end, made their existence “provisional.” To some of the prisoners this made everything seem unreal, and so everything could seem pointless to them.2

Some prisoners suffered massive psychological collapse, others kept themselves intact. Frankl stresses that even there it was possible to retain human dignity. How a person accepts suffering and a terrible fate can still give a deeper meaning to his life: “Only the men who allowed their inner hold on their moral and spiritual selves to subside eventually fell victim to the camp’s degenerating influences.”3 The values that had to be held on to varied from person to person. What persuaded a prisoner not to kill himself might be his irreplaceability for his waiting daughter, or the book to be finished. Frankl quotes Nietzsche: “He who has a why to live can bear almost any how.”

One natural interpretation of making something of your life is giving it a pattern reflecting what you care about. For many people, this is part of the why that helps them bear almost any how. The natural expression of a pattern is a narrative that makes some sense of a life.

For many of us some kind of narrative is one of the threads holding our life together. But not everyone wants to give his life a pattern. Galen Strawson has drawn a distinction between two kinds of people: Narratives and Episodics. Narratives want to make something of their lives. Episodics do not; they include Galen Strawson himself: “I’m completely uninterested in the answer to the question ‘What has GS made of his life?’ or ‘What have I made of my life?’ I’m living it, and this sort of thinking is no part of it. This does not mean that I am in any way irresponsible. It is just that what I care about, in so far as I care about myself and my life, is how I am now.”4

The point is a useful corrective to exaggerations about narrative. But perhaps Narrative/Episodic is less a sharp contrast than a continuum. Some neurological conditions reduce awareness to little more than the immediate present. Short of such impairments, can anyone be completely episodic? People at that end of the continuum may still feel a twinge of embarrassment at the memory of something they blurted out last month. In “What I care about is how I am now,” a lot depends on the scope of “now.” Perhaps it includes last month. But I wonder if Galen Strawson would be indifferent if the stimulating books he has written over the years were pulped, and all traces of them destroyed?

Clearly there are people at the episodic end of the continuum. Galen Strawson’s list includes Virginia Woolf. It is true that what mattered most to her seem to have been what she called “moments of being.” They were not part of any pattern but were moments of rich or intense experience. As a child, fighting her brother, she suddenly felt, “Why hurt another person?” She stopped and then felt hopeless sadness about her powerlessness as he continued to beat her. Another time, having overheard that someone she remembered had killed himself, she walked in the moonlight by the apple tree in the garden and felt with horror that the apple tree was somehow linked to the suicide. Many moments of being were less dark and less intense: responding to the willow trees “all plumy and soft green and purple” against the sky, reading an absorbing book, or starting to write one of her own. But these moments were always “embedded in a kind of nondescript cotton wool” of much of a day—contrasted with having a slight temperature or dealing with the broken vacuum cleaner.5

If Virginia Woolf was at the episodic end of the continuum, it would still be absurd to say her life did not add up to anything. Quite apart from the books she wrote, so many “moments of being” speak for themselves. A life that adds up to something does not have to be a life you make add up to something. Self-creative narrative is only one important thing among many that give meaning to a life.

This episodic version of meaning is important for people with severe autism and other conditions that make narrative difficult or impossible. On the other hand, finding different ways of telling a narrative may be crucial to helping people with post-traumatic stress disorder bring themselves together.

I have argued in this part of the book that the core aim of psychiatry is to help people overcome psychological conditions that are harmful. On the human flourishing version, this harm consists in obstacles to their living a good human life. Most of the traditional psychiatric categories of disorder are such obstacles. But the medical conception of dysfunctional systems is too narrow to include all psychological obstacles calling for the offer of psychiatric help. In some cases there are problems in identifying psychological systems or their functions. Where dysfunctions can be identified, what calls for help is the harm rather than the dysfunction.

This in turn leads into questions about the kinds of harm that may justify offering psychiatric help, and the different accounts of the good life with which they are contrasted. Human flourishing and liberal accounts will sometimes diverge. And both may sometimes license nonmedical “treatment”: help against harmful psychological conditions that do not fit traditional categories of disorder. This in turn raises acute ethical issues about the need for boundaries to block stifling versions of psychiatry based on narrow conceptions of the good life.

The rest of the book is based on strands of the good life that have been gestured at in this chapter. Relationships and work, from which people often derive a sense of meaning, are linked to having a degree of control over your life. Another source of meaning, at least for non-Episodics, can be the shaping of one’s own identity. Control and the shaping of identity are both lost to external agents in Brave New World and the experience machine. The topics of the remainder of this book, Parts 5 and 6, are psychiatric issues affecting these two strands in the good life.

Some psychological conditions seriously limit people’s control over their lives and their ability to shape their identity. This is a case for seeing such conditions as harms calling for the offer of psychiatric help. (It is only a prima facie case. There are the identity and neurodiversity issues raised by autism. And the obstacles to the good life may come less from the condition itself than—as with being gay or with having “sinful” sexual desires—from pressures coming from the reaction of others.)

Psychiatry is shot through with interpretation. Its goals are shaped and limited by values. The rest of this book will link these two central thrusts of the argument so far. Most current accounts of psychiatric geography are based on causal mechanisms, either conjectured or established. The aim here is not to replace this geography but to supplement it with a different map that takes seriously the person’s own view from inside. This may bring out how different psychiatric problems subvert the values of control and identity. My hope is to open up new ways to interpret some conditions. Taking seriously the question of subversion of control in addiction or in some personality disorders means locating these conditions in a larger picture of agency and its distortions. And perhaps some versions of eating disorders and of post-traumatic stress disorder can be illuminated when they are seen as being, at their core, disorders of identity.