Susan D. Fischer

Sign languages arise almost anywhere there are deaf people. By definition, deaf people cannot hear, but most have an intact capacity for language, and language will out one way or another. While there are a few documented instances where sign languages have been invented, their emergence is generally spontaneous. When there is a critical mass of deaf people, as often occurs at school, the emergence of a fully developed sign language can be extremely rapid. In what follows, I shall give an overview of what we know about the history of signed languages. I shall concentrate mostly on the history of American Sign Language (ASL), but will also discuss historical developments in the Japanese Sign Language family (which comprises Japanese, Korean, and Taiwanese sign languages). Sign languages, like creoles, are relatively young, and there is some documentation on their beginnings, which is nearly unique in historical linguistics.

Two major factors put sign languages in a unique position: the channel in which they are communicated and the sociolinguistic environment in which deaf children are exposed to them. Specifically, sign languages are communicated through a gestural/visual rather than a vocal/auditory channel. Secondly, due to both genetics and educational policies, deaf children – and adults – can be exposed to sign languages at different ages, ranging from birth (to signing parents, often deaf themselves) to adulthood, with more or less successful acquisition of the surrounding spoken language. Since the vast majority of deaf children are born to hearing parents (Schein and Delk 1974), many deaf children learn sign languages not from their parents but from their peers. Third, due to attitudes in the general population (with some exceptions), sign languages are frequently stigmatised, seen as less than ‘true’ languages, and parents may be discouraged from signing with their deaf children.

With regard to the different channel of communication, although channel does not affect the overall structure of the grammar (Lillo-Martin 2002), there are certain ways in which relations are manifested in the grammar that are more frequent in a gestural/visual channel than in the vocal/auditory one; specifically, one notices a greater amount of simultaneity in sign languages than one often finds in spoken languages, due to the strengths of the channel. This is not to say that there is no linearity in sign languages or no simultaneity in spoken languages, but merely that simultaneity is facilitated by the visual channel. Features that appear to be facilitated by the strengths of the channel include classifiers (found in all established sign languages), the use of space for verb agreement, and simultaneous markers of syntactic processes such as the use of a headshake for negation and the use of raised eyebrows to form polar questions (see Fischer 2006).

The channel of communication may be responsible for some features of sign languages; the sociolinguistic context in which they are situated could well be responsible for others (see Fischer 1992 for more discussion). One of the reasons that a great deal of input is from peers rather than parents is that only about 8–10 per cent of deaf children have deaf parents (Schein and Delk 1974); and although more and more parents of deaf children are learning some form of signing, it is still a fairly small percentage. And again, even though some form of signing is used in most schools in the United States nowadays, the situation remains that the majority of users are not native. This creates the possibility of influencing the grammar.

Features that could be due to the sociolinguistic context include the use of topicalisation structures and other instances of non-segmental markers of grammatical functions such as questions and negation (Fischer 1978, 2006). Fischer (1978) argues that sign languages arise in much the same context as creoles, which share with sign languages features such as non-segmental marking of grammatical operators. T. Supalla and Webb (1995) point out that unlike creoles, pidginised and creolised sign systems such as International Sign Language have grammatical complexity such as morphological verb agreement that are lacking in spoken creoles. S. Supalla (1991) also notes that agreement develops spontaneously in the sign languages of children exposed exclusively to strict manual codes for English that lack agreement. However, we now know that some creoles (e.g., Haitian – DeGraff 2009) and even some pidgins (Bakker 1994) have inflections as well, so the parallels do still hold.

The fact that sign languages are frequently stigmatised leads to the phenomenon of code-switching especially with members of the outgroup (e.g., hearing non-signers). Signers will thus often strive to mirror the majority language in their signing, similar to the continuum between creoles and acrolects from which their vocabulary is largely derived. It thus becomes difficult to define where, say, ASL ends and signed English begins. This situation is changing in the United States and a few other Western countries but sign languages are still stigmatised in places. Thus, someone who can sign ‘in English’ may be more respected or valued than someone who can sign only in more basilectal ASL. Indeed, the policy of the Chinese educational system is that signed Chinese, rather than CSL, is the ‘official’ sign language of China.

Most users of sign languages end up being bilingual, in the sign language and the surrounding spoken language, or at least its written version. When deaf children go to school (there are some countries or situations where they don’t), they are inevitably exposed to the written language of the community.2 With some exceptions (notably Sweden and a few bilingual-bicultural schools in the United States), if signing is used in a school, it tends to be a signed version of the surrounding spoken language rather than the native sign language. Even when a sign language is not used in a school, there is contact with the written language. Contact with the spoken or written language is one of the things that helps to shape, but not determine, sign language grammars. It is no accident that ASL is underlyingly head-initial, based on influence from English, though there are remnants of the head-final constructions of 100+ years ago, and the structure of discourse often necessitates that some constructions are head-final on the surface, due to the requirement that referents be specified before agreement can operate.3

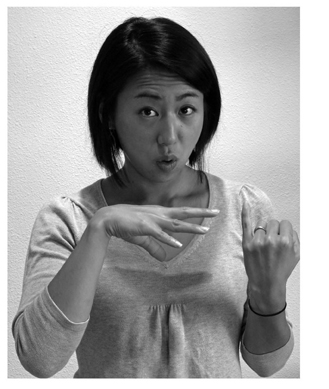

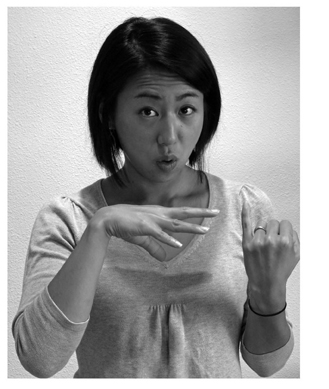

In addition to the strengths of the visual part of the gestural/visual channel are the strengths of the signing apparatus. The number of independent articulators permits the simultaneous expression of many morphemes. For example, in Japanese Sign Language (JSL), the dominant hand can show a verb while the non-dominant hand can express an anaphoric object; at the same time, mouth movement can express a TAM marker, direction of eye gaze expresses the subject, and raised eyebrows can express a polar question; the result is one sign (and one syllable) that means ‘did you tell her?’; see Figure 20.1.

One correlate of the use of a different channel is the thorny issue of iconicity and concomitantly, the often porous barriers between sign and gesture, or between sign and mime. I have often remarked that sign languages have more iconicity because they can (see, for example, Fischer 1979). While spoken languages contain some iconic material, such as the kinds of ideophones found in Japanese or Xhosa, sign languages have more. This is for several reasons: first, sign languages tend to be younger than spoken languages, so they have had effectively less time to become more conventionalised (see Frishberg 1975). The fact that many signers are not native could also have a continued influence. More importantly, however, is the fact that iconicity is more conducive to the visual channel than to the auditory channel; it is more difficult to evoke the physical world with sound than with vision. Sign languages have grammaticalised and conventionalised mime not only in the lexicon (e.g., the ASL sign MILK is, if not transparently, at least translucently, similar to the action of milking a cow) but also in the grammar. Two examples may be illustrative here. First, agreement for many verbs especially those showing transfer, is expressed by changing the direction of movement of the verb sign. The idea of moving the body forward to show giving and moving backward to show receiving was first remarked by Birdwhistell (1970), and is in some nontechnical sense, ‘natural’.

Figure 20.1 JSL ‘Did-you-tell-her?’

Second, ASL and many established sign languages use classifiers to express the theme or the instrument in a verb. This consists of a handshape that abstracts away from the shape of the object or the configuration of a hand holding an instrument. What might be called proto-classifiers have also been found in co-speech gesture by McNeill and his colleagues (McNeill 2004).

In addition to mime, gesture can also be grammaticalised into sign languages. While these gestures can sometimes have mimetic sources, they can be quite language-specific. Here are a few examples from JSL. The sign SUMIMASEN/GOMEN, which is variously translated as ‘excuse me’ or ‘I’m sorry’ among others, is transparently derived – and semantically broadened – from a gesture that hearing Japanese use for ‘excuse me’ in the context of trying to manoeuvre in a crowd. The Japanese classifier for female comes from a hearing gesture consisting of a fist with extended upraised pinkie which we saw in Figure 20.1 as the non-dominant hand denoting a previously mentioned female. This has both been lexicalised in signs like KEKKON (‘marry’) which involves female (upraised pinkie) and male (fist with extended upraised thumb) classifier approaching each other, as well as in kinship terms. Male and female classifiers can also take the place of referential loci for agreement verbs, as Figure 20.1 shows. Hearing persons’ gestures are also the source for the classifier that covers dogs, foxes, and other smallish snouted animals. The handshape resembles the Texas ‘hook-em horns’ handshape, and by itself represents the syllable KI in JSL fingerspelling (short for kitsune, ‘fox’).

I mentioned earlier that sign languages are relatively young. This means that their origins, rather than being shrouded in the distant past, are at least partially known. The earliest systematic description of a sign language occurs in the late eighteenth century, when L’Abbé de l’Épée founded the first school for the deaf that used sign language. L’Épée took signs that already existed in Paris and added what he called ‘methodical signs’ for use as both metalinguistic devices and ways of tying the signing to French grammar.4 The founder of the first school for the deaf in the United States, Edward Miner Gallaudet, visited L’Épée’s school and hired its star pupil, Laurent Clerc, to come and teach at his school in Hartford, Connecticut. According to Woodward (1978), children from Martha’s Vineyard, where a descendant of British Sign Language was used, attended the school and had some influence over the development of ASL. For ASL at least, then, we have some direct knowledge of how it came to be.5

The first thing to note about sign language families is that they bear at most a tenuous relation to spoken language families. A general misconception is that each country’s sign language is intimately tied to the spoken language of that country.6 This notion is false in two directions: there are countries that share the same sign language but not the same spoken language (more below); and there are countries that share a common spoken language but have two different sign languages. An example of both is Taiwan Sign Language, which is related to Japanese Sign Language, though the spoken language in Taiwan is Mandarin. Taiwan Sign Language is not related to Chinese Sign Language, though recent borrowings make the situation a little less clear-cut (see below). BSL is used in the United Kingdom; mutually comprehensible dialects are also used in Australia and New Zealand. BSL is almost totally distinct from ASL, although English is spoken in both the United States and the United Kingdom. Italy has two sign languages: one used in Trieste (which appears to be closely related to LSF [langue de signe frangaise]) and the one used elsewhere in the country, though Italian is spoken all over Italy. Trieste used to be part of Slovenia, and the sign language is closer to the sign languages spoken in Slavic countries, which are derived largely from LSF. Indo-Pakistani Sign Language (IPSL) is used all over India, despite differences in spoken language, e.g., Indo-European vs. Dravidian languages.7

The structure of sign language families depends in large part on the migration of teachers and the establishment of schools. The first school for the deaf that both used sign language and had more than a 1:1 student-teacher ratio, was founded in Paris in the late 1700s. The founder of the school, L’Abbé de l’Épée, took the signs that the students already had (which he called signes naturelles) and augmented them with metalinguistic signs (called signes méthodiques) that among other things made it possible to connect the sign language used in the school to French or Latin grammar. Many European sign languages, as well as ASL and several South American sign languages, came about through the diaspora of teachers and graduates from the Rue St. Jacques School in Paris.8

This story begs the question of where those signs that already existed came from. One explanation is of course that signs arise spontaneously where there is even one deaf person in a family, though it may take some kind of critical mass and even a generation or two for a full-fledged language to develop; see, for example, the work of Susan Goldin-Meadow and her associates on so-called home signs (e.g., Goldin-Meadow 2003). These signs are often the product of a deaf child, not of his or her parents.

Another aspect of the signing that developed into LSF comes from a surprising source. Cagle (2010) has found concrete evidence that one of the sources for LSF, which in turn is a major source of ASL, is the signing of Cistercian monks who maintain silence in much of their daily activity. Cagle found that a significant number of Cistercian signs going back 1,000 years, albeit with some semantic and phonological shifts, are still part of ASL.

Within Europe, LSF spread at least to Denmark, Russia, and Italy. As mentioned above, a variety of LSF spread to the United States and English-speaking Canada, and also to Brazil. The situation in the United States was somewhat complicated by the fact that the first school, in Hartford, Connecticut, attracted students from Martha’s Vineyard, which had its own sign language based on BSL. There were thus some indirect influences on ASL from BSL (Woodward 1978).

According to Wittman (1991), German Sign Language (DGS) spread at least to Poland. Swedish Sign Language also belongs to a distinct family, which has influenced some other Scandinavian sign languages and, according to Wittman (1991), also Portuguese, though Danish appears to be closer to French. There was apparently also an Austro-Hungarian Sign Language probably influenced by LSF. Israeli Sign Language appears to be an amalgam of the sign languages of many immigrants. Some African and Asian sign languages have been influenced by ASL; in the Philippines, for example, English education for deaf children is conducted in a manual code for English that uses ASL signs in English word order; lore has it that it was introduced by a deaf Peace Corps volunteer. However, parallel to this is an indigenous Philippine sign language that appears to be totally distinct.

In Asia, the Japanese Sign Language family comprises Japanese, Taiwanese, and Korean sign languages. This is related to the colonisation of Taiwan and Korea by Japan in the first half of the twentieth century, when the first schools for deaf children were established. A dialect of Chinese Sign Language is used in Hong Kong, and there appears to be some influence of Chinese Sign Language in southeast Asia; Thai Sign Language uses the same forms of morphological negation as CSL, for example.9 That said, the morphological negation used in China may have in turn been borrowed from BSL (Bencie Woll, personal communication).

Since sign languages have traditionally been fairly isolated, many have developed independently. This is especially true in cases where sign languages are not used in schools, or even more, where deaf children do not go to school at all. Recent non-historical influences on sign languages have come from two main sources: sign languages in adjacent communities and the surrounding spoken language. In addition, some governments have mandated the type of sign language to be used in education. As well as the example of the Philippines, in at least some parts of Indonesia an ASL-based signed form of English is used along with spoken Bahasa Indonesia.

Another influence (unfortunate in my view) on the development of sign language families arises from the fact that there are very few institutions of higher learning for deaf persons in the world. Until very recently, deaf people who wished to go to university pretty much had to go to Gallaudet University in Washington, DC. There they learned ASL, and when they went back to their home countries, many introduced ASL (or signed versions of English) as a language of instruction. This has had the effect of suppressing many indigenous sign languages. Just as sign languages are often stigmatised with respect to spoken languages, indigenous sign languages are often stigmatised – by deaf people themselves – vis-a-vis ASL. LSF, via ASL, has thus had a broad influence on sign languages in a diverse group of countries, especially in Africa. Dialects of ASL are also used in the West Indies, even in former British colonies like Trinidad-Tobago and Jamaica, where one might expect varieties of BSL to be adopted instead.

The introduction of ASL, or signed versions of English, in other countries is one example of lateral influences on sign languages. In Taiwan, the large influx of mainland Chinese since 1949 has led to borrowings not only of vocabulary but of grammatical devices such as person classifiers and negative morphology. This can lead to real confusion: the thumbs-up handshape constitutes a morpheme meaning male in the JSL family but positive in the CSL family; similarly, the extended pinkie means female in the JSL family but negative in the CSL family. TSL is thus very much in flux; furthermore, different parts of the island have different amounts of influence from CSL. Context can help to disambiguate meaning, but not always; the language is changing before our eyes.

We mentioned above that the morphological negation used systematically in CSL may have come from BSL. Another instance of language contact in which BSL has had a lateral influence on another sign language is the case of Martha’s Vineyard sign language. Martha’s Vineyard was initially settled by Britons, and apparently included some users of BSL. After the first school for the deaf in the United States was established in Hartford, Connecticut, children from Martha’s Vineyard attended, bringing their sign language with them. According to Woodward (1978), this had an influence on the LSF that had been brought to the United States from France. Lateral influences can come from spoken language as well as from other sign languages; as discussed above in section 2 and below in section 5, the syntax and even morphology of sign languages is often influenced by the surrounding spoken language. For example, the northern dialect of CSL uses the A-not-A construction to form some syntactic negatives (Yang and Fischer 2002).

Calques from English occur more frequently than previously realised in ASL; for example, even native deaf signers use phrases like CAN’T STAND, meaning ‘dislike’, using the sign STAND, which normally means only to stand up, instead of the sign PATIENT, which in that context would mean ‘tolerate’.

In the following sections, I shall describe in somewhat greater detail the kinds of change that have been observed in sign language, both as a result of contact with other signed and spoken languages and as a result of the kinds of pressures that guide the development of all types of languages, signed and spoken.

Like other natural languages, sign languages have duality of patterning, so that there is a sublexical level at which component parts are generally devoid of meaning but can be put together into forms that do have meaning. For example, an open hand with fingers spread can mean the number 5, but in combination with other parts (conventionally called parameters in the sign language literature) can convey meaning. That ‘5’ handshape with the thumb touching the chin means ‘mother’. If it touches the centre of the chest and the fingers wiggle, the entire sign means ‘great, fantastic’. If the same handshape touches the chin and then moves to the side, it means ‘farm’. If an extended index finger instead of an open ‘5’ hand touches the chin, the sign means ‘miss’ or ‘disappointed’, while if a ‘3’ hand (thumb, index, and middle finger extended) touches the chin, the whole thing means ‘swank’.

That picture of meaningless elements combining to form meaningful units is somewhat clouded by the iconic and gestural roots of sign languages. Early records of sign languages, such as they are, show the iconic and gestural roots of signs much more graphically than their more arbitrary descendants; that gestural substrate is closer to the surface and more pervasive than analogous phonetic symbolism is in spoken languages. For ASL, this has been documented by Frishberg (1975) and also T. Supalla (2013). Frishberg compared a sign language dictionary published in 1918 (Long 1918) with then-current signing in the early 1970s. She shows that both phonological and visual constraints conspire to make signs performed more centrally and more symmetrically. One vivid example of making signs more symmetrical and in the process more arbitrary is the sign SWEETHEART. In Long (1918), this sign is made on the left side of the chest with the hands forming a heart shape and the thumbs wiggling to convey the idea of a heart beating (see Figure 20.2). The current sign is made in the centre of the chest and the hands no longer form a heart shape (see Figure 20.3). Another example is the sign HELP: in Long (1918), as well as in the movies made in 1913 by the National Association of the Deaf (NAD), HELP is signed with a flat hand moving the forearm of the other side up, and the signing hand is to one side (Figure 20.4). In Stokoe et al. ‘s (1965) dictionary, HELP is described with the dominant hand touching the bottom of the other fist in a central location and moving it up. The sign has thus become more centralised and in some sense smaller. Now, it is fairly unusual for the dominant hand to be underneath the non-dominant hand, and in fact current versions of the sign have made it even smaller and more regular with what was the dominant hand becoming stationary and what was the nondominant hand moving downward to touch it, as shown in Figure 20.5. Note the reversal in the position of the hands with respect to each other. There is a movement currently to document phonological changes in JSL (Kanda and Osugi 2011). These also show a trend to centralisation and conventionalisation.

In terms of phonological constraints, Stokoe et al. (1965) implicitly, and Battison (1978) explicitly, posited a number of constraints for ASL, many of which hold also for other established sign languages. It is revealing, for example, that Stokoe’s notation system does not have provisions for monomorphemic signs to have two locations in different major areas of the body; Stokoe’s notation system allows for a sign to have two different major locations only in the case of compounds. For example, the sign LEARN is a compound of COPY and MIND; it starts on a hand and ends up on the forehead, two major locations. Stokoe is forced to treat it as a compound of two morphemes. The sign has since simplified by reducing the movement so that the signing hand does not go all the way to the forehead but rather goes up only a small distance; the result is a sign that stays in one major location.

Figure 20.2 Old version of ASL SWEETHEART

Figure 20.3 Current version of ASL SWEETHEART

Figure 20.4 Old version of ASL HELP

Figure 20.5 Current version of ASL HELP

Stokoe also implicitly restricts the number of handshapes in a sign: a single sign has at most two handshapes; for example, the active hand in the sign LEARN changes from an open hand to a tapered/closed hand, while the active hand in the sign SHOWER changes from a loose fist to an open hand. This is in contrast to at least one sign in Old French Sign Language (Lambert 1867). The Old LSF sign for ‘king’ consisted of spelling R-O-I while moving diagonally down and across the chest. (The ASL signs KING and QUEEN are clearly derived from LSF ROI; they use the same location and movement. However, the handshape has simplified to K or Q, respectively.) The restriction to no more than two handshapes in a sign is reflected in Stokoe’s notation system.

Battison’s (1978) Symmetry Condition states that in monomorphemic signs, when both hands move, and one hand does not impinge on the other, the handshapes will be the same. The sign HELP described in Stokoe is not a counterexample to this constraint since one hand is effectively pushing the other. Battison’s Dominance Condition states that when the two handshapes are different, the non-dominant or ‘weak’ hand does not move (unless impinged upon by the dominant or ‘strong’ hand), and must be one of five or six unmarked handshapes (e.g., a flat hand with fingers open or closed, an extended index finger, a curved hand with closed fingers, or a fist shape). Some interesting changes have occurred as a result of these constraints. For example in the early 1970s, when manual codes for English were very popular, many signs were initialised in ways that violated the Symmetry and Dominance conditions. For example, the basic sign TOWN was changed to VILLAGE by changing one of the handshapes to the fingerspelled letter V. That sign has mostly disappeared, but not before being regularised by changing both handshapes to Vs rather than only one. A similar change to a more symmetrical sign occurred earlier with the sign YEAR. This sign used to be made with two different handshapes. Over time the non-dominant hand has assimilated in shape to the dominant hand.

There is another kind of constraint on phonological change, based on the visual apparatus. Siple (1978) showed that if one is looking at one’s interlocutor’s chin, visual acuity is highest around the face and diminishes the farther away from the face the signing is. So, for example, visual acuity at the edge of the signing space, say the hips, is only about 10 per cent of what it is around the chin. There have been shifts in ASL such that two-handed signs made on the face become one-handed, while signs made at the periphery of the visual field have come to involve two hand and large movements.

Sign languages have, for at least 150 years, expanded their vocabulary by borrowing from their surrounding spoken – actually written – languages. The earliest example I have seen is the LSF sign for ‘king’, documented in Lambert (1867). It consists of the fingerspelled letters R-O-I being placed successively on a diagonal path on the signer’s chest. Note that in its 1867 form, this would violate the condition implicit in Stokoe et al. that there be no more than two handshapes in one sign. The modern ASL sign KING has only one handshape (a fingerspelled K), which traces the same movement as in the original French sign, but with two contact points instead of three (there are very few monomorphemic ASL signs with three movements; BUTTONS is the only one that comes to mind as of this writing).

A word is in order about fingerspelling. Fingerspelling has exceptional phonology vis-avis standard signs: it is relatively static; the only movement is in the changes in handshape going from letter to letter. Furthermore, there are some handshapes that occur distinctively only in fingerspelling (or in initialised signs made by superimposing a fingerspelled letter on a more basic sign). Also importantly, in real fingerspelling more than two handshapes are allowed. Thus, though an important part of ASL, it is phonologically marginal, in that it does not conform to the constraints on more integrated signs. And although fingerspelling preexisted both ASL and LSF by a few hundred years, it is often a much less integral part of other sign languages, even modern-day LSF. So, for example, place names are usually fingerspelled in ASL, but have their own signs in JSL. In addition to proper nouns, or more generally, for expressing English content words for which there is no sign, fingerspelling is also used for function words for signing ‘in English’.

A subset of frequent fingerspelled words have evolved into actual signs, called fingerspelled loan signs (Battison 1978). In contrast to normal fingerspelling, fingerspelled loan signs follow phonological constraints more closely. For example, all but two letters, usually leaving only the first and last letters, are elided, in order to obey the constraint of having only two handshapes per sign; but some kind of path movement is added to make it more sign-like. The number of fingerspelled loan signs is on the order of a couple of dozen, and include #JOB, #BACK, #BUSY, and #NO. Some can be grammatically active; for example, #BACK can express goal, and #NO, a verb meaning to refuse permission, agrees with the indirect object.

Fingerspelling is a relatively recent introduction to CSL and JSL. However, they also exploit Chinese characters in ways analogous to both fingerspelling and fingerspelled loan signs. The analogue of normal fingerspelling as a way to borrow from the written language is to draw a Chinese character on the hand or sometimes in the air (Ann 1998; Fischer and Gong, 2010, 2011). These so-called character signs are also on the order of a couple of dozen, though perhaps more in the case of Taiwan Sign Language and Hong Kong Sign Language, which lack fingerspelling as an alternative. As in the case of fingerspelled loan signs, character signs can be grammatically active; for example, the character sign for person, A, is made in JSL by tracing the character with one index finger (character signs tend to be based on relatively simple characters). To signify four persons, the handshape for the numeral four is substituted for the index finger. In CSL, that same character A is depicted by two index fingers touching at the tips. It too is grammatically active: ‘who’ is shown by twisting one of the fingers, and ‘how many people’ is indicated by substituting both the handshape and movement for ‘how many’ onto the existing sign. Both of these are productive processes that occur with other signs not related to Chinese characters.

Fingerspelling (or drawing Chinese characters in the air in Asian sign language) is a way of adding to the vocabulary of a sign language by borrowing from a spoken language. Another way is via the process of initialisation. This involves replacing the original handshape of a base sign with the fingerspelled letter that begins a spoken language word in the same semantic family. The process of adding the sign VILLAGE based on the general sign TOWN as seen in Figures 20.6 to 20.8 is an example of initialisation. Figure 20.6 shows the original sign, and Figures 20.7 and 20.8 show the initialised sign that substitutes the fingerspelled letter V for the original handshape, which happens to be a B but has no spoken-language relation to the meaning of ‘town’.

While frowned upon by sign language purists, initialisation has a long and venerable history. Cagle (2010) points out that the ASL sign SEARCH is made with a C handshape; the corresponding French word chercher begins with the letter c. Similarly, the ASL sign GOOD is made with a B handshape, after the French word bon, and SEE is made with a V handshape (French voir). Some of these actually go back to the Cistercians, according to Cagle. The initialised sign I (based on the more common ME) has been part of ASL for a long time, as has FAMILY (which uses an F handshape superimposed on the sign GROUP). In addition, initialisation is the most common way to form name signs in ASL; the fingerspelled letter that starts a person’s name is superimposed on either an arbitrary location or a sign that is associated with some characteristic of the person. For example, if a man has a beard and his name starts with an R, his name sign could be an R performed on the chin.

Figure 20.7 Intermediate version of ASL VILLAGE

Figure 20.8 Newer version of ASL VILLAGE

Japanese Sign Language has initialisation as well, but in a much more limited way, for several possible reasons: (1) many older Japanese deaf people do not know fingerspelling, since it was introduced fairly late; (2) most Japanese deaf schools are oral, which means that at least in the primary grades sign language is not used in the classroom, thus obviating the need to expand vocabulary; (3) formal Japanese name signs relate to the meaning and/or shape of the Chinese characters used to represent their family name, rather than the pronunciation of the name.

A great deal of morphophonological change in sign languages involves fusion, assimilation, and concomitant reduction processes which are also frequently part of the synchronic system in sign languages, though the roots of some of these processes have been lost and are no longer psychologically real. These are well-known phenomena that have been discussed amply for ASL in the sign language phonology literature (see, for example, the discussion in Sandler and Lillo-Martin 2006), so I will give only a couple of examples, one from ASL and the other from the Japanese Sign Language family.

Consider the ASL sign SISTER, which historically comes from GIRL plus SAME. In forming the fused sign, the handshapes for GIRL (a thumb extended from a fist) and SAME (an extended index finger) are combined, as shown in Figure 20.12.10 This resulting L handshape is echoed in the non-dominant hand by a process of assimilation. Another process of assimilation and reduction raises the non-dominant hand; furthermore, the dominant hand ends up on top of the non-dominant hand rather than next to it. As in all compounds in ASL, the movement in the first part of the compound is reduced or in this case deleted, leaving only the initial position of the extended thumb. The amount of reduction is sufficient to permit the formation of a compound meaning ‘siblings’ by concatenating BROTHER and SISTER. Figures 20.9 to 20.13 show BOY, GIRL, and SAME, and then the current signs for SISTER and BROTHER.

The example of assimilation, fusion, and reduction from the Japanese Sign Language family involves the expression of numbers, specifically teens. Figures 20.14 to 20.16 show the depiction of the numbers 10, 7, and 17, which is a combination of 10 and 7. Numerals in the JSL family can be incorporated into measure phrases, e.g., 7-JIN (7 PEOPLE) or predicates, as in 7-HIKOOKI-HAIRU (enter an airplane). The fused 17 handshape can also participate in those processes (see Fischer et al. 2011). As these types of handshapes exist in all three members of the JSL family, one can conclude that the change that permitted their formation must have occurred before the languages split in 1945.11

One interesting example of morphological change that has occurred in both ASL and TSL involves numerals, though in different spheres. In many sign languages, the numeral 1 is also the classifier for human being. Now, in Western European culture, counting on one’s fingers starts with the thumb for 1, and successive fingers are extended for the numerals 2–5. However, in the United States, counting starts with the forefinger, and the thumb is extended only for the numeral 5. In ASL there are many vestiges of the French system (see Fischer 1996), such as the signs for ‘chase’ and ‘baptise’, which utilise the French 1; and ‘second-hand (used)’, which involves the French 2; the ASL 3 is the same as the French. There is a dynamic tension between the French and US systems that occurs in less-frequent signs such as FOURTH-OF-FOUR, where previous generations used the French 4 (which has an uncommon handshape with all fingers except the pinkie extended; younger generations simplify to the American 4). Fischer (1996) used internal evidence within ASL to induce the development of the ASL numeral system. Here I examined the current ASL numeral system and found it to be partly a mash-up of French and American numeral gestures, but also that it incorporated the orientation of the French numerals 1–5 (different from current hearing French people’s gestures for the same numerals) and had some real innovations not found in either LSF or French or American gestures in the way teens were expressed. Furthermore, the classifier for ‘person’, which in many sign languages is cognate with the number 1, shows up in frozen signs (e.g., FOLLOW, BAPTISE, and HIGH-STATUS as the French 1 but in morphologically productive signs such as MEET12 as the American 1).

Figure 20.16 JSL family SEVENTEEN

The example from TSL involves the sign for Wednesday. This in turn is an indirect borrowing from Mandarin, where days of the week are numbered, e.g., Monday is 1-day, Tuesday is 2-day, etc. (in Japanese and JSL, by contrast, they are named as they were historically in English: moon-day, fire-day, water-day, etc.). TSL now uses the Chinese signs for days of the week. However, it uses the JSL numerals instead of the Chinese numerals. Specifically, the numeral 3 (which looks like the US gesture for 3) is used instead of the CSL numeral 3 (which looks like the American ‘OK’ gesture). See Figures 20.17 and 20.18. Here, then, we have TSL borrowing the structure of a sign from contact with another sign language while using part of the form of the native language.13

I can cite one other interesting type of variation within a language family, though one must speculate as to the direction of change. Fischer and Osugi (2000) noted an alternation between normal agreement verbs and agreement with what we called an indexical classifier, a handshape that replaced the locus of agreement in neutral space (agreement in sign languages usually involves movement to or from a locus for established referents). We found that virtually any verb that agreed with an animate object, and sometimes subject, could express agreement with an indexical classifier, and the only difference in meaning was that when an indexical classifier is used, its referent must be definite and specific. Interestingly, both TSL and KSL permit far fewer alternations between normal agreement and agreement using indexical classifiers, but for opposite reasons: in TSL, indexical classifiers are relatively rare. In contrast, according to Hong’s (2007) research on KSL, the use of indexical classifiers has become the norm for agreement and the alternates without the indexical classifier are not generally found. The likely path of change, in my view, would then be an initial variation in JSL and a regularisation in opposite directions to a preferred pattern.

I have mentioned earlier that constituent order in sign languages come to resemble the constituent order of the spoken languages surrounding them. So, for example, ASL is now predominantly head-initial, while JSL is consistently head-final (Fischer and Gong 2010). I have (Fischer 1975, 1990) discussed this phenomenon for ASL. As late as 1871 (Keep 1871) and even to some extent in the 1913 National Association of the Deaf (NAD) films, ASL was head-final, though not uniformly. The switch to head-initial had to have occurred by 1942, as NAD films from then look almost identical to current ASL. And the switch is across the board; in addition to verbs generally preceding their objects, auxiliaries and negation, which used to follow the verb now precede it, and such adpositions as there are now generally precede rather than follow their objects. Fischer (1975) offers a possible mechanism by which the change from verb-final to verb-initial occurred, namely that in an NP NP V sequence which was SOV, the first NP comes to be seen as a topicalised object, so that the second becomes the subject. Such a mechanism, however, would not really account for the total change in headedness that seems to have occurred in ASL in a few short generations. T. Supalla (2004) suggests that the change had already started by the time of the 1913 NAD films, and an examination of one of those films (Veditz’s defence of sign language) supports that claim. That film, even though it shows different headedness from what we find in Keep (1871), does exhibit a surface iconicity (see Figures 2–5 from Long [1918], which are contemporaneous with the NAD films) that was gone in another generation. Other films from the same session do show fairly strict head-final structures, so here we have some ferment that resolves itself in another generation. The borrowing of constituent order from adjacent languages thus occurs in sign languages as well as in spoken languages, though the mechanisms by which such changes occur may not be the same.

Very little research has been done on syntactic change in other sign language families. However, it is striking to note that within the Japanese Sign Language family, modern-day TSL is generally head-initial. Since JSL is head-final, presumably influenced by spoken/ written Japanese, this constitutes a change from the original (it is documented that TSL – and KSL – came originally from Japan: Nakamura 2006), presumably under the influence of Mandarin, or perhaps the influx of CSL, itself influenced by Mandarin, especially the northern dialect of CSL, after 1949. HKSL also appears to be head-initial.

Forty to sixty years is a remarkably short time for a language to change so drastically, especially at the level of syntax. To account for this we probably need to appeal to the fact that young languages such as creoles, to which sign languages bear both structural and sociolinguistic resemblance, tend to change more rapidly than more established ones. Woodward (1978) points out that viewed from the perspective of glottochronology, ASL would be classified as much older than it is given the extent of change over a well-documented short period of time.

Another kind of evolution has occurred in both ASL and the JSL family, namely the development of function words from content words. In ASL, at least one subordinating conjunction has developed from a verb. This is of course common to many languages. Concretely, in ASL the formation of the sign UNDERSTAND has been modified and weakened and means something like ‘although’; see Fischer and Lillo-Martin (1990). In addition, the sign WRONG can be modified to mean ‘but’ and both WELL and SUCCEED can, in different contexts, be used to mean ‘so’.

In TSL, Smith (1990) showed that two verbs, MEET and SEE, had been bled of meaning to serve as auxiliaries to carry agreement, analogous to Jo-support in English. A third auxiliary consisting only of the tracing of a path of agreement from subject to object, is used in JSL as well as in TSL. The use of MEET and SEE as auxiliaries appears to have dwindled in the 20 to 30 years since Smith collected his original data (Shiou-Fen Su, personal communication).

This kind of development of course occurs in mainstream spoken languages as well as in sign languages and creoles; in the development of Romance languages, for example, there is a continuous dynamic tension among pronouns, clitics, and inflection. Lord (1993: 242) provides evidence that in Yoruba two content words meaning ‘see’ have been bled of meaning and combined to become a complementiser. I have posited (Klima and Bellugi 1979: 396) that a verb agreement in ASL developed from deictic pronouns similarly to the way inflections arose in Romance. As mentioned above, verb agreement in sign languages is manifested by movement of the verb toward the goal, while the palm of the hand faces the object (Meir 1998). I have argued that what was there initially was a deictic pronoun, which then became cliticised to the verb, and then became an agreement marker.14

Semantic change is probably the least documented type of linguistic change with respect to sign languages, but we can pinpoint a few changes that have occurred in ASL and in the JSL family. As with many changes, some of these originate in language variation. JSL has two signs each for ‘100’ and ‘1000’. In the Osaka dialect, of JSL in fact, those phonologically marked handshapes are generally reserved for talking about money, so the marked forms have semantically narrowed. It is interesting that the marked forms are preferred in TSL over the unmarked forms, which goes against what one might predict, especially considering that the CSL sign for 1000 is the same as that in JSL, based presumably on the cursive form of the Chinese character.

In this section I would like to discuss the historical development of wh-questions in ASL, since they demonstrate a variety of types and sources of historical change. ASL has signs for all major wh-concepts, e.g., WHO, WHAT, WHICH, WHERE, WHEN, WHY, HOW, HOW-MANY, WHAT-FOR. There is also a verbal wh-sign, #DO meaning ‘what to do’, that I will discuss later. There are two signs for ‘when’ and two for ‘what’. ASL has no signs for ‘whose’ or ‘how much’ or indeed anything like ‘how long’. This is not surprising; many languages lack terms for these concepts. When used in main clauses, wh-signs in ASL are accompanied by a specific wh-facial expression consisting of furrowed brows and sometimes pursed lips. Lillo-Martin and Fischer (1992) talked about what they called ‘covert’ wh-signs; we showed that many wh-words actually consist of a normal sign plus that facial expression, sometimes accompanied by a modified movement, so for example, WHAT-TIME is actually TIME plus that wh-facial expression, and HOW-MANY is actually MANY with the same wh-facial expression and a slightly different movement in the sign. WHAT-FOR is the sign FOR repeated with that same wh-facial expression. There are many signs in this genre that are commonly used in ASL, such as WHAT-COLOUR, WHAT-NAME, WHAT-HAPPEN, and WHAT-SAY. Such covert wh-signs exist in many other sign languages, notably in the JSL family. Wh-signs in ASL are generally limited to interrogative uses, but the sign WHO with a different eye-gaze and eyebrow raises instead of furrows can be used to mean ‘whoever’. Perhaps other wh-signs can be used in similar environments but the research on this has not been done.

Alongside the lexical wh-signs mentioned above are fingerspelled versions for many of them. Using fingerspelled wh-words constitutes a type of borrowing, and has apparently occurred at several stages in the history of ASL; we shall return to that latter point. When there is a sign alternative and a fingerspelled equivalent is used instead, regardless of whether it is interrogative or not, it is usually being used for emphasis. That is certainly true in the case of H-O-W vs. HOW. But in addition to that change in emphasis, an interesting semantic – and syntactic – split has occurred due to the coexistence of fingerspelled and signed versions of the same concept. This is most notable in the case of WHAT vs. two different reductions of the fingerspelled loan sign #WHAT.

The two signs WHAT can be used to form full questions, e.g., (1)–(2):

(2) WHAT MOTHER LIKE? ‘what does Mom like?’

The order in (1) is not possible in embedded clauses; it appears only in main clauses. Otherwise, there is no discernible difference between the orders in (1) and (2). The fuller form of the fingerspelled loan sign is used to indicate incredulity in an echo question; it can be used at the end of a sentence or just by itself:

(3) MOTHER LIKE #WHATj ‘Mother likes what?’

The more reduced fingerspelled loan sign is always used by itself, often but not always as a challenge; it consists of rapidly repeating the only T in W-H-A-T but with the palm up to show its derivation:

(4) #WHAT2 ‘c’mon, give.’

A different case in terms of the function of a fingerspelled loan sign is the case of #WHEN. This can be used in exactly the same environment as WHEN. For many signers, the two real signs for ‘when’ have essentially disappeared from the language, and #WHEN has taken over completely.16 This is not unprecedented in language: fifty years ago the Japanese for black tea was koocha. Now it is mirukutei (from ‘milk tea’) or remontei (from ‘lemon tea’).

This use of #WHEN seems to be a fairly recent change, since I do not recall seeing it 40 years ago when I was first learning ASL. Of the two signs for ‘when’ that do not have a fingerspelled source, one, which fairly transparently relates to ‘at what point’ is viewed in some regions as indicating signed English; the other appears to be related to the sign HAPPEN. #WHEN would appear to have pushed out the former sign, perhaps as part of a resistance to the influence of English. In any case, the fingerspelled origin of #WHEN is still quite clear.

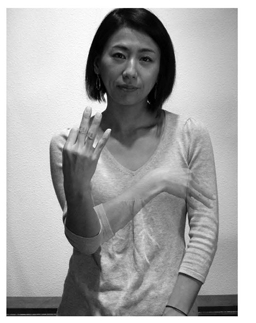

In contrast, the fingerspelled sources of two wh-signs have been obscured by linguistic change. These are WHO and WHY. WHO is now signed with an index finger in front of the mouth, as in Figure 20.19.

There may in fact be two sources for this sign. T. Supalla (2013) argues that it is a reduced form of FACE, which would put it with the other covert signs discussed above. However, in some areas, the source is a fingerspelled loan sign #WHO (a W closing to an O) in front of the mouth, which has been further reduced. Thirty years ago one of my sign language consultants, who was older than me at the time, still used this form. See Figure 20.20.

The second old borrowing from fingerspelling is the sign WHY; this sign starts with an open hand on the forehead that moves down and closes to a Y handshape. If one adds the Y handshape to the W handshape, one ends up with an open handshape. This sign can be further abbreviated by signing in neutral space with the middle and ring finger opening and closing repeatedly; that variant, like #WHATP must occur either by itself or sentence-finally only, and has a pragmatic use similar to that of the reduced form of #WHAT. Figure 20.21 shows the sign WHY (See also Fischer 2006).

The phenomenon of borrowing – or coining – from an adjacent or prestige language at different stages also occurs in spoken language, so we should not be surprised that it also occurs in a sign language.

I have discussed both fingerspelled wh-words and signs and also what Lillo-Martin and Fischer (1992) call covert wh-words. Those two phenomena converge in one other wh-word or sign that has been ‘borrowed’ from English in a way that English wouldn’t do it. There is a fingerspelled sign #DO, which when reduplicated means ‘errands’ (many things to do). However, when the wh-facial expression is overlaid onto it, means ‘what are you/am I to do?’ See Figure 20.22 (reprinted with permission from Fischer 2006).

All of these words that are derived from fingerspelling are unique to ASL and not part of any other sign language in the LSF family, and thus constitute an innovation, but an innovation influenced by the surrounding spoken language.

Figure 20.22 ASL ‘WH-#DO’ (‘what to do?’) reprinted with permission from Zeshan 2006

Like creole languages, sign languages are relatively young; the oldest on record is just over 200 years. Young languages, whether signed or spoken, change rapidly. We have available to us a few natural laboratories of emerging sign languages that demonstrate that rapidity. In the case of Nicaragua, successive cohorts at the school for the deaf that have been studied by Senghas and others (see, e.g., Senghas and Coppola 2001) show radically different amounts of grammatical productivity. Village sign languages such as ABSL (Aronoff et al. 2008) have arisen in only a few generations, and many still lack some of the grammatical mechanisms that we find in more established sign languages.17 This provides some support for Bickerton’s theories about the rise of creole languages from pidgins (Bickerton 1975), in that they differ substantially from their parent languages and continue to change rapidly over just a few generations.18 Even more established sign languages like ASL are still changing rapidly, from the adoption of new vocabulary (e.g., initialised signs) to phonological and morphological developments. The difference between the ASL signing of 1875 and 1942 is remarkable in the evolution of both arbitrariness and major and systematic changes in constituent order (Frishberg 1975; Fischer 1975, 1990).

When I first discussed the parallels between sign languages and creoles 35 years ago (Fischer 1978), I pointed out the parallels in the sociolinguistic contexts in which both types of languages arise. In recent work DeGraff (2003, 2009) argues that it is the nexus of sociolinguistic context (e.g., the stigmatisation of basilects) as well as the processes of first and second language acquisition that contribute to similarities both among creoles and between sign languages and creoles. He further argues that so-called creolisation is simply one instance of language change. That said, just as creolists have been finding that creoles aren’t as grammatically similar as we used to think (see, for example, some of the papers in Arends et al. 1994), more recent typological studies have been finding substantive grammatical differences among sign languages (e.g., Brentari 2010; Zeshan 2006; Zeshan and Perniss 2008). So, perhaps ironically, the parallels between sign languages and creoles remain valid, but then so do the parallels between new languages and more established ones.

One of the advantages of dealing with a young language is, then, that we can see language change in progress. The particular study of language change in sign languages tends to bring up issues that we have been happy sweeping under the rug but cannot afford to. With the exception of Labov and his followers, we often tend to ignore the variable raw materials that contribute to language change. There is probably greater variability in sign languages than in many spoken languages precisely because, even if used in schools, there are no equivalents to ‘language arts’ for sign languages. As a result the languages are far less standardised; this might help to contribute to the rapidity of language change. One might argue that many minority languages also have no equivalents of ‘language arts’ in majority language schools. However, there is an additional complication in the case of sign languages: namely the fact that sign languages are acquired at different ages with resulting differing degrees of competency by deaf children. Recall that only a very small percentage of deaf children are exposed to any kind of signing from birth. Some deaf children are exposed when they enter school, between the ages of 2–5; others, whose parents are counselled to eschew sign language, might start to learn to sign at much later ages. We know from the critical period literature that this makes a difference. In this case, it just adds to grammatical – and phonological – variability.

The second issue that needs to be addressed is the balance between language family trees and lateral influences via diffusion. When I took my first historical linguistics course, it was all about Indo-European trees. But with sign languages, the ‘trees’ look more like lattices, with ancestors and descendants but also influences from the side; the fact of bilingualism and how that can influence the language being learned has not been investigated sufficiently; more globally, we also see the influence of a hegemonic sign language (ASL) on the sign languages in many developing countries. One other example of lateral influence within a sign language is the introduction of CSL into Taiwan, which has the potential to sow confusion in the grammar (for example, the same handshapes used to signal positive vs. negative in the CSL family denote male and female in the JSL family; and classifier handshapes for such basic concepts as human being are different in the two families). It is not just signs, therefore, but morphological processes that are having an influence.

One of the contributions of sign languages for linguistic theory is that they force us to face issues that have sometimes been conveniently swept under the rug in the examination of spoken languages. The influence of language contact is one such issue, and indeed, historical linguists are once again examining many influences on language change, from contact to sociolinguistic context. The kinds of historical change I have been describing are not unique to sign languages, and therefore raise issues that merit further investigation within the field of historical linguistics.

1 Thanks to Patrick Graybill, Nozomi Tomita, and Brandon Scates for their help with the photos. Thanks also to Claire Bowern and Beth Evans for their insightful comments and suggestions. Following standard practice, I gloss signs in capital letters in the written language associated with the sign language. Hyphens between spoken-language words indicate that more than one spoken-language word is required to gloss the sign. Slashes between words show alternative meanings in the spoken language for the same sign. Agreement is marked with subscripts and classifiers with superscripts. Abbreviations: ASL=American Sign Language; CSL=Chinese Sign Language; JSL=Japanese Sign Language; TSL=Taiwanese Sign Language; KSL=Korean Sign Language; LSF=Langue de Signes Franjaise; LIS=Lingua Italiana di Segni; HKSL=Hong Kong Sign Language, BSL=British Sign Language

2 It’s actually more complicated than that; in some multilingual countries, deaf children may be exposed to, say, written English, even though their hearing parents use a totally different language. Hope Morgan (personal communication) says that this is largely the case in Kenya, where mouthed English words are used in schools along with Kenyan Sign Language. See also Michieka (2005).

3 ASL is often SOV on the surface, but most of the time auxiliaries precede verbs, which may provide more evidence for ASL being underlyingly head-initial.

4 This type of language planning has been used numerous times, and the artificial signs almost invariably disappear from the language in time.

5 When I was a young researcher, about 40 years ago, I had the honour of meeting an elderly deaf man who had studied at the American School in Hartford with Hotchkiss, who had himself studied with Clerc.

6 A corollary to that misconception is that sign languages are merely debased form of the spoken language, which contradicts another general misconception in the general population is that sign language is universal.

7 There is, however, a pocket of ASL users in Bangalore (Ulrike Zeshan, personal communication).

8 Schools are important for another reason: full-fledged sign languages require a community of users, and schools are often the main way to gather up enough users to make a difference; the notion of critical mass is key. Once there are enough deaf children gathered together a sign language will develop – language will out, as it were. This helps to account for the development of new sign languages that have been observed, from Nicaraguan Sign Language (establishment of a school) to ABSL and other village sign languages that result from an increase in the incidence of deafness in a community.

9 It is not clear that this is directly from CSL or through other sources; more research is necessary on this topic.

10 Actually they are combined only in the second half of the sign.

11 There’s actually quite a bit of variation among signers in the three languages. The native JSL model for the figures shown here does not in fact use these forms herself. It remains an open question whether these forms developed independently, but their marked phonology leads me to conclude that they existed prior to the split of the three languages.

12 The sign MEET permits numeral incorporation, which BAPTISE, CHASE, and HIGH-STATUS do not. One can thus substitute a numeral 2 handshape for one 1 and a 3 handshape for the other 1 and have the resulting sign mean ‘two people meet three people’.

13 I am grateful to Beth Evans for pointing out the significance of this phenomenon.

14 Liddell (2003) suggests that what is called verb agreement in sign languages is extra-linguistic. However, as Lillo-Martin (1986) and others have shown, the presence of agreement licenses prodrop and violation of the ECP, which strongly suggests that it cannot be extra-linguistic.

15 This section is based on Fischer (2011).

16 One of the WHEN signs is seen as ‘signed English’ and is thus dispreferred; the other, which appears to be related to the sign HAPPEN, is not as widespread.

17 Village sign languages do not all lack the same things; some may lack agreement, while others may lack classifiers. See Zeshan and de Vos 2012.

18 Two big differences between signed languages and creoles: first, in signed languages the vocabulary comes from the substrate and some of the grammar comes from the superstrate. Secondly, while there are contact varieties of signing, and there are some consciously invented [e.g., by educators] signs, the vast majority of signs appear spontaneously, not from any preexisting languages, meaning that there is no pre-existing ‘substrate’ except perhaps for gesture.

Fischer, Susan D. 1975. Influences on word order change in American Sign Language. In Charles Li (ed.) Word order and word order change. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1–25.

——1990. The head parameter in ASL. In William Edmondson and Fred Karlsson (eds) Proceedings of the fourth international symposium on sign language research. Hamburg: Signum Press, 75–85.

Frishberg, Nancy. 1975. Arbitrariness and iconicity: historical change in American Sign Language. Language 51: 696–719.

Supalla, Ted. 2004. The validity of the Gallaudet Lecture Films. Sign Language Studies 4: 261–292.

Ann, Jean. 1998. Contact between a sign language and a written language: character signs in Taiwan Sign Language. In Ceil Lucas (ed.) Pinky extension and eye gaze, sociolinguistics in deaf communities series. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press, 59–99.

Arends, Jacques, Pieter Muysken and Norval Smith (eds). 1994. Pidgins and creoles: an introduction. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Aronoff, Mark, Irit Meir, Carol Padden and Wendy Sandler. 2008. The roots of linguistic organization in a new language. In Derek Bickerton and Michael Arbib (eds) 2008. Holophrasis, Compositionality andprotolanguage. Special Issue of Interaction Studies, 133–149.

Bakker, Peter. 1994. Pidgins. In Arends et al., 21–39.

Battison, Robbin. 1978. Lexical borrowing in American Sign Language. Silver Spring, MD: Linstok Press.

Bickerton, Derek. 1975. Dynamics of a creole system. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Birdwhistell, Ray. 1970. Kinesics and context: essays on body motion communication. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Brentari, Diane (ed.). 2010. Sign languages: a Cambridge language survey. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Cagle, Keith. 2010. Exploring the ancestral roots of American Sign Language: lexical borrowing from Cistercian Sign Language and French Sign Language. Doctoral dissertation. University of New Mexico.

DeGraff, Michel. 2003. Against creole exceptionalism. Language 79: 391–410.

DeGraff, Michel. 2009. Language acquisition in creolization and, thus, language change: some Cartesian-uniformitarian boundary conditions. Language and Linguistics Compass 3(4): 888–971.

Fischer, Susan D. 1975. Influences on word order change in American Sign Language. In Charles Li (ed.) Word order and word order change. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1–25.

——1978. Sign language and creoles. In Patricia Siple (ed.) Understanding language through sign language research. New York: Academic Press, 309–333.

——1979. Many a slip ‘twixt the hand and the lip: applying linguistic theory to non-oral language. In Robert K. Herbert (ed.) Metatheory III: application of linguistics in the human sciences. East Lansing: MSU Press, 45–75.

——1990. The head parameter in ASL. In William H. Edmondson and Fred Karlsson (eds) Proceedings of the fourth international symposium on sign language research. Hamburg: Signum Press, 75–85.

——1992. Similarities and differences among sign languages: some hows and whys. Proceedings of the 11th World Federation of the Deaf. Tokyo, Japan, 733–739.

——1996. By the numbers: language-internal evidence for creolization. In William H. Edmondson and Ronnie B. Wilbur (eds) International review of sign linguistics. Volume 1. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum, 1–22.

——2006. Questions and negation in American Sign Language. In Ulrike Zeshan (ed.) Interrogative and negative constructions in sign languages. Nijmegen: Ishara Press, 165–197.

——2011. Contact borrowing of interrogative pronouns: the case of American Sign Language. Paper presented at the International Conference on Historical Linguistics, Osaka, Japan.

Fischer, Susan D. and Qunhu Gong. 2010. Variation in East Asian sign language structures. In Brentari (ed.), 502–521.

——2011. Marked handshapes in Asian sign languages. In Rachel Channon and Harry van der Hulst (eds). 2011. Formational units in sign language. Boston: DeGruyter, 19–41.

Fischer, Susan D., Yu Hung and Shih-Kai Liu. 2011. Numeral incorporation in Taiwan Sign Language. In J.-H. Chang (ed.) Language and cognition: Festschrift in honor of James H.-Y. Tai on his 70th birthday. Taipei: The Crane Press, 147–169.

Fischer, Susan D. and Diane Lillo-Martin. 1990. UNDERSTANDing conjunctions. International Journal of Sign Linguistics. 1: 71–81.

Fischer, Susan D. and Yutaka Osugi. 2000. Thumbs up vs. Giving the finger: Indexical classifiers in Japanese Sign Language. Paper presented at Theoretical Issues in Sign Language Research 7, Amsterdam.

Frishberg, Nancy. 1975. Arbitrariness and iconicity: historical change in American Sign Language. Language 51: 696–719.

Goldin-Meadow, Susan. 2003. The resilience of language: what gesture creation in deaf children can tell us about how all children learn language. New York: Psychology Press.

Hong, Sung-Eun. 2007. Agreement verbs in Korean Sign Language. Paper presented at Theoretical Issues in Sign Language Research 9, Florianopolos, Brazil.

Kanda, Kazuyuki and Yutaka Osugi. 2011. Database of historical changes in Japanese signs from 1901–2011. Paper presented at the International Conference on Historical Linguistics, Osaka, Japan.

Keep, J. R. 1871. The sign language. American Annals of the Deaf 16: 221–234.

Klima, Edward S. and Ursula Bellugi. 1979. The signs of language. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Lambert, Louis-Marie ,l’Abbé de. 1867. La clef du language de la physionomie et du geste (extrait de la Méthode courte, facile, et pratique d’enseignmement des sourds-muets illettrés. 3-ième édition. Paris: l’Institution Impériale de Paris.

Liddell, Scott. 2003. Grammar, gesture, and meaning in American Sign Language. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Lillo-Martin, Diane. 1986. Two kinds of null arguments in American Sign Language. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 4: 415–444.

——2002. Where are all the modality effects? In Richard P. Meier, Kearsy Cormier and David Quinto-Pozos (eds) Modality and structure in signed language and spoken language. New York: Cambridge University Press, 241–261.

Lillo-Martin, Diane and Susan D. Fischer. 1992. Overt and covert wh-questions in American Sign Language. Paper presented at Theoretical Issues in Sign Language Research 5, Salamanca, Spain.

Long, J. S. 1918. The sign language: a manual of sign illustrated, being a descriptive vocabulary of signs used by the deaf of the United States and Canada. Omaha, NE: D. L. Thompson.

Lord, Carol. 1993. Historical change in serial verb constructions. Typological Studies in Language No. 26. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

McNeill, David. 2004. Hand and mind: what gestures reveal about thought. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Meir, Irit. 1998. Thematic structure and verb agreement in Israeli Sign Language. PhD dissertation. Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Michieka, Martha M. 2005. English in Kenya: a sociolinguistic profile. World Englishes 24: 173–186.

Nakamura, Karen. 2006. Deaf in Japan: signing and the politics of identity. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Sandler, Wendy and Diane Lillo-Martin. 2006. Sign language and linguistic universals. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Schein, Jerome and Marcus Delk. 1974. The deafpopulation of the United States. Silver Spring, MD: National Association of the Deaf.

Senghas, Ann and Marie Coppola. 2001. Children creating language: how Nicaraguan Sign Language acquired a spatial grammar. Psychological Science 12: 323–328.

Siple, Patricia. 1978. Visual constraints for sign language communication. Sign Language Studies 19: 95–110.

Smith, Wayne. 1990. Evidence for auxiliaries in Taiwan Sign Language. In Susan D. Fischer and Patricia Siple (eds) Theoretical issues in sign language research 1. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 211–228.

Stokoe, William, Dorothy Casterline and Carl Croneberg. 1965. A dictionary of American Sign Language on linguistic principles. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press.

Supalla, Samuel. 1991. Manually coded English: the modality question in signed language development. In Patricia Siple and Susan D. Fischer (eds) Theoretical issues in sign language research 2. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 85–109.

Supalla, Ted. 2004. The validity of the Gallaudet Lecture Films. Sign Language Studies 4: 261–292.

——2013. The role of historical research in building a model of sign language typology, variation and change. In Ritsuko Kikusawa and Lawrence Reid (eds) Historical linguistics 2011: selected papers form the 20th international conference on historical linguistics. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 15–42.

Supalla, Ted and Rebecca Webb. 1995. The grammar of International Sign: a new look at pidgin languages. In Karen Emmorey and Judy S. Reilly (eds) Sign, gesture and space. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum, 333–352.

Wittmann, Henri. 1991. Classification linguistique des langues signées non vocalement. Revue québécoise de linguistiquethéoriqueetappliquée 10: 1.215–288.

Woodward, James. 1978. Historical bases of American Sign Language. In Patricia Siple (ed.) Understanding language through sign language research. New York: Academic Press, 333–348.

Yang, Jun-Hui and Susan D. Fischer. 2002. The expression of negation in Chinese Sign Language. Sign Language and Linguistics 5: 167–202.

Zeshan, Ulrike (ed.). 2006. Interrogative and negative constructions in sign languages. Nijmegen: Ishara Press.

Zeshan, Ulrike and Pamela Perniss (eds). 2008. Possessive and existential constructions in sign languages. Nijmegen: Ishara Press.

Zeshan, Ulrike and Connie de Vos (eds). 2012. Sign language in village communities. The Hague: Mouton deGruyter.