A typology of phonological restructuring

Paul Sidwell

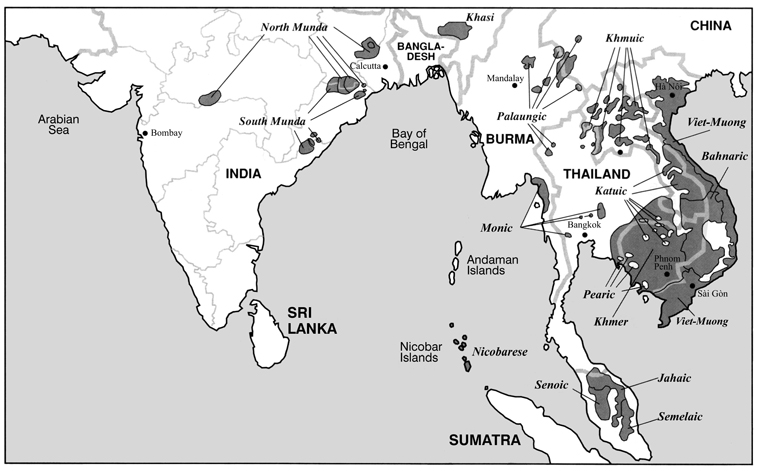

The Austroasiatic (AA) phylum is the oldest recognisable language family in the mainland of South and Southeast Asia, with approximately 150 – mostly small – languages straddling a discontinuous geographical distribution from central India to the coast of Indo-China (see Figure 32.1). Austroasiatic also includes national languages Vietnamese and Khmer, the historically important Mon with a written tradition going back some 1,500 years, and in India Khasi, with perhaps half a million speakers, has official status in Meghalaya state. Spread over such a vast area for thousands of years, and subject to sustained external influences from numerous unrelated languages, remarkable typological diversity has understandably accrued from branch to branch. The diversity found within the phylum is so great that, as Donegan and Stampe (2004: 4) put it, “the Munda and Mon-Khmer1 branches of Austroasiatic, rarely studied by typologists, provide a nearly exhaustive inventory of the extremes of difference in human language structures.”

There are at least a dozen recognised Austroasiatic branches, although recent scholarly opinion is sharply divided on how they coordinate phylogenetically. Diffloth (2005) proposes a deeply nested branching tree, with Central, Northern and Western (Munda) coordinated sub-families, although no evidence for this model has been published. More recently, Sidwell and Blench (2011) have argued from historical phonology and computational phylogenetics that the family tree is effectively rake-like, with branches diversifying internally well after initial radical radiation. The former view is traditionally gradualist, while the latter is more punctuated. For substantial reference materials that profile the phylum, its geography, demographics, and the history of Austroasiatic studies, refer to Parkin (1991), van Driem (2001) and Sidwell (2009, 2011).

Despite strong disagreements within the small field of Austroasiatic studies, the phylum has been subject to comparative-historical studies since the end of the nineteenth century, and we are in the happy position today of having large comparative data sets, extensive phonological and lexical reconstructions of various subgroupings, and working models of Proto-Austroasiatic phonology and lexicon (see Sidwell 2011 for a review). This work is so far developed that we can describe and characterise many of the kinds of historical changes that have occurred in Austroasiatic, although for the sake of space and coherence this chapterwill focus on phonological change, from word level to segments. The dominant theme that will be discussed here is one of restructuring of syllable and phonological word, and segmental change that occurred within that context, as the two must often be considered together to be fully understood.

Figure 32.1 Geographical distribution of Austroasiatic branches (originally appearing in van Driem 2001: 267; reproduced with permission)

In the sections that follow I will try to categorise and exemplify these changes. Time and again the kinds of changes we find/reconstruct are best conceptualised as change in syllable structure; either in terms of restructuring sesquisyllabic and disyllabic forms towards monosyllables, or augmenting mono- and sesquisyllables to create more complex forms. At a deeper lever level both processes can be thought of as a tendency towards structural symmetry, coming from a starting point of a markedly asymmetrical phonological word template in the context of a highly isolating typology.

The Proto-Austroasiatic canonical word is reconstructed (e.g. Donegan 1983; Diffloth 2005; Shorto 2006) as conforming to the widespread Southeast Asian pattern that prefers monosyllables or iambic disyllables. Prefixing and infixing were the principal morphological processes. We can also suggest that, as in contemporary conservative Austroasiatic languages such as Katu (Costello 1966, 1971, 1991; Nguyễn Hữu Hoành 1995; etc.), reduplication and segmental alternations played an important role, especially in terms of expressive (non-prosodic) lexicon. Additionally, word formation through compounding – although areally common today under Tai, Indic, Sinitic and other external influences – was absent or at best only marginally productive. The above considerations allow us to reconstruct the following Proto-Austroasiatic word template:

(1) Austroasiatic phonological word template

The word template consisting of the combination of presyllable and main syllable is conventionally referred to as the sesquisyllable (literally ‘syllable and a half’; coined by Matisoff 1973). Roots could be mono- or disyllabic, and further augmented by prefixation, infixation or cliticisation. Most affixes were single consonant or vowel segments, with infixes always inserted immediately to the right of the leftmost consonantal segment. Consonantal affixes were commonly realised with vowel epenthesis to maintain preferred syllable structure. Additionally there were roots with initial consonant sequences that included plateaued or falling sonority, and were resyllabified phonetically. Thus there was often complex interaction between phonetics and morphology that could render forms morphologically opaque.

Within the phonological word positional restrictions created strong internal asymmetries. The most privileged positions were C2 and V2, in which any of the full inventory of consonants or vowels available in the system were permitted, while other positions were limited. C3, being an optional component of the main syllable onset, permitted only the approximants /r, l, w, j, h/). C4 segments corresponded to the C2 inventory but without the voicing contrast; final oral stops were unreleased voiceless, with simultaneous glottal constriction; C4 sonorants were voiced and probably significantly longer in duration than their C2 counterparts. C1 and V1 constituted the presyllable, in which the vowel may or may not have been phonemic, hence the distinction between sesqui- and disyllabic forms. C1 excluded at least glides and implosives, while the other consonants were apparently utilised. V1, conventionally represented with a schwa, was present either as an epenthetic vowel or as a vocalic infix, in the latter case timbre may have been significant.2 N1 represents a nasal coda in the presyllable; this could be etymological or reflect an infix, and given its relatively high sonority would not normally co-occur with V1 .

Proto-Austroasiatic root structure was essentially C(C)V(:)C with more complex forms built up by affixations. This is illustrated with some contemporary Katu examples (from Costello 1966):3

(2) Monosyllabic roots plus derived forms:

| ca: ‘to eat’ | : paca: ‘cause to eat’ | p- prefix plus vowel epenthesis |

| tam ‘root’ | : tanam ‘classifier for plants’ | <n> infix plus vowel epenthesis |

| teŋ ‘to work’ | : tarneŋ ‘work’ | <rn> infix plus vowel epenthesis |

| kliaŋ ‘to lock door’ | : kaliaŋ ‘wood to lock door’ | <a> infix |

(3) Sesquisyllabic roots plus derived forms:

| kanɔʔ ‘to think’ | : karnɔʔ ‘thoughts’ | <r> infix |

| galək ‘to trick’ | : paglək ‘classifier for plants’ | p- prefix |

| ʔntoʔ ‘to fall’ | : pantoʔ ‘cause to fall’ | p- prefix plus vocalisation of glottal onset |

| ʔmbuah ‘to bump’ | : tambuah ‘to bump (myself)’ | t- prefix plus vocalisation of glottal onset |

Mainland Southeast Asia as a linguistic area has been widely recognised and discussed (e.g. Bisang 1996; Enfield 2003, 2011; Matisoff 1978; Migliazza 1996) and among the defining features is a supposed “trend toward monosyllabicity” to lift a phrase from Enfield (2005: 186). However, as Brunelle and Pittayaporn (in press) point out:

[…] the tendency for sesquisyllables to become monosyllabic is less common than is usually assumed: the overwhelming majority of sesquisyllabic languages do not undergo monosyllabization, even when in contact with languages with more reduced word types.

This applies particularly to Austroasiatic; in just a few cases there has been complete reduction to monosyllables, more often there is substantial but incomplete reduction. Each presents a story of change in circumstances that do not always fit a simple narrative of assimilation to a dominant areal pattern.

2.2.1 Vietnamese: complete monosyllabism

Vietnamese is very much the poster child of monosyllabisation in Austroasiatic, given its status as the single largest Austroasiatic language and controversies that have raged for decades over its history and genetic affiliation (see Alves 2000 for an overview). Haudricourt (1952, 1954) made it clear that Vietnamese is neither Sinitic, Tai nor even especially mixed in origins once the literary component is taken into account, and the basic tonogenetic mechanism explained. More recently, Ferlus (1997, 1998, 2004) has reconstructed a detailed account of Vietnamese historical phonology.

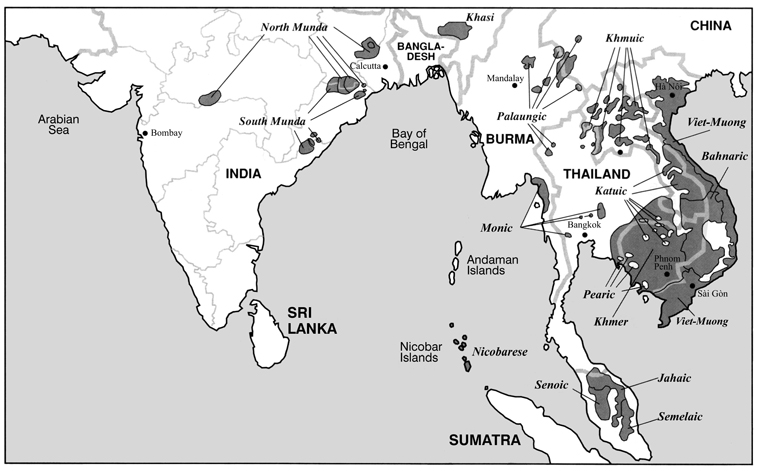

Sesquisyllables were reduced in Vietnamese variously by simple lenition of initial segments plus assimilations/spirantisations of certain clustered onsets, although the specific changes and their environments can be quite complicated. Additionally there are extensive other changes, some of which are discussed elsewhere in this chapter. As a result, it was not just sesquisyllables that were reduced, but also monosyllables of the type C2C3V(C) became simple CV(C) syllables. See examples in (4).

| Proto-Austroasiatic (Shorto 2006)4 | Proto-Vietic (Ferlus 2007) | Vietnamese | Glosses |

| *slaʔ | *s-laːʔ | lá [lá] | ‘leaf’ |

| *phoːm | *k-samʔ | rắm [rắm] | ‘to fart’ |

| *kʔiːp ‘centipede’ | *kr-siːp | rệp [rẹp] | ‘bug’ |

| *kraʔ | *k-raːʔ | sá [sá] | ‘road, path’ |

| *klmiəʔ | *k-mɛːʔ | mía [míə] | ‘sugarcane’ |

| *ɟkaw | *c-kuːʔ | gấu [gə́w] | ‘bear’ |

| *gmaʔ | *k-maː | mưa [mɨə] | ‘rain’ |

Vietnamese is actually the typological oddity within Vietic; the minor Vietic languages of the Lao-Viet borderlands maintain sesquisyllables quite robustly, and remain important witness languages for Proto-Austroasiatic. Phonological reduction in Vietnamese has effectively eliminated affixation and compounding is now the dominant method of word formation, so we could say that disyllabisity is emerging as the new norm.

2.2.2 Nyaheun: complete monosyllabism

Nyaheun is a small endangered West Bahnaric language spoken in the south of Laos. The remarkable phonology of Nyaheun was first described by Davis (1973) and Ferlus (1971), and the phonological history worked out in detail by Sidwell and Jacq (2003). While other Bahnaric languages robustly maintain sesquisyllables (with only partial exceptions) Nyaheun has uniquely undergone a complete restructuring to monosyllables. This was accomplished by two processes: 1) assimilation of clusters creating geminates; and 2) lenition of prevocalic segments creating medial approximants. In some cases both processes acted on the same etyma, producing double outcomes, the reasons for which are not well understood. The result is a language so transformed that it is almost unrecognisable to speakers of closely related neighbouring tongues, whom I have heard characterise it as ‘baby talk’. See examples in (5).

2.2.3 Mangic/Pakanic: complete monosyllabism

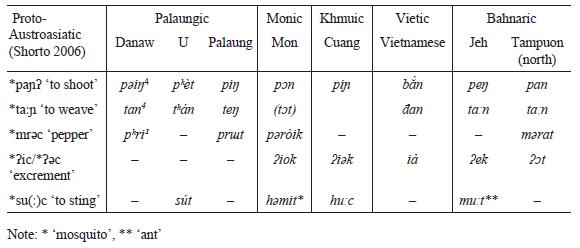

The Mangic/Pakanic group consists of three small languages: Bugan (aka Pakan) and Bolyu (aka Lai, Paliu), two isolated but clearly related languages spoken in Guangxi, and Mang spoken in Northern Vietnam. It remains controversial whether Mang actually groups with Bugan and Bolyu, but the hypothesis is accepted by this writer. Bugan and Bolyu are both structurally Sinosised, with all etymological sesquisyllables reduced to monosyllables, and compounding is now the dominant word formational process (Benedict 1990; Edmondson and Gregerson 1995; Li Jingfang 1996). Mang has also undergone significant restructuring, but the notation used in the principal source (Lợi 2008) is difficult to interpret so it is not discussed further here. The examples in (6) show that monosyllabism was achieved by both simple loss of presyllables, and fusion of sequences into single segments (e.g. *ɟh- > s-, *st- > ʨ-, *cʔ- > ʑ-).

| Proto-Austroasiatic (Shorto 2006) | Bugan | Bolyu | Gloss |

| *cʔaːŋ | ʑa35 | – | ‘bone’ |

| *ktəm | tham33 | thəm13 | ‘egg’ |

| *ɟhoːʔ | saw31 | saːw55 | ‘tree, wood’ |

| *cna(ː)m | nam35 | nəːm13 | ‘year’ |

| *(t)ɓəl/(t)ɓul | mən33 | mən13 | ‘thick’ |

| *tɓa(ː)ŋ | – | mbɔŋ55 | ‘bamboo shoots’ |

| *ln[b][o]ʔ | – | vɔ13 | ‘buffalo’ |

| *rməŋ ( | – | mɔŋ33 | ‘to hear’ |

| *stam/stu(ː)m | – | ʨəm55 | ‘right side’ |

| *tmɔʔ | – | maw11 | ‘stone’ |

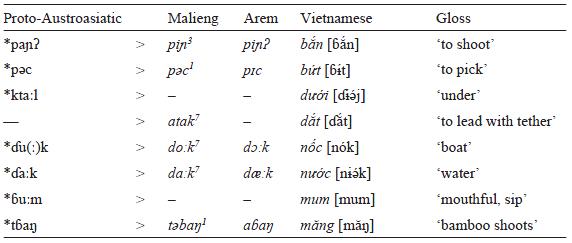

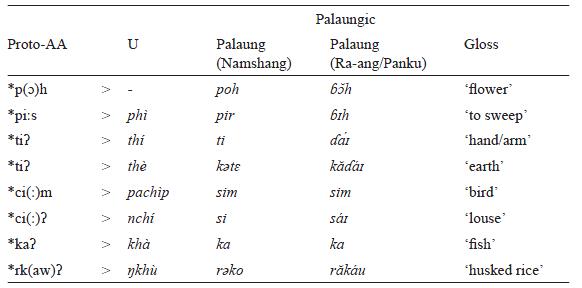

2.2.4 U: partial monosyllabism

U, a Palaungic language of the Angkuic subgroup spoken in Yunnan, was documented and analysed by Svantesson (1988). U underwent strong syllable restructuring that resulted in reduction of the vast majority of sesquisyllables into monosyllables, leaving only four possible presyllables in its inventory: /sa/, /ʔa/, /pa/ and a homorganic nasal presyllable.

The restructuring also involved complex changes within the rhymes, resulting in a four-tone system, loss of quantity contrast, and much reduced inventory of codas. Mostly the reductions involved simple loss of initial segments, with remaining main syllable initials undergoing regular sound changes as if there had never been a presyllable. However, rhotic clusters (e.g. tər-) became alveolar affricates. See examples in (7).

| Proto-Austroasiatic (Shorto 2006) | Proto-Palaungic (Sidwell 2010) | U | Gloss |

| *kcas | *kcas | sé | ‘charcoal’ |

| *(b)saɲʔ | *psəɲ | sèt | ‘snake’ |

| *ɟheːʔ | *kseʔ ‘wood, tree’ | sì | ‘stick’ |

| *ktaːm | *ktaːm | thám | ‘crab’ |

| *rtuːŋ | *rnɗɔːŋ ‘ladder’ | thúʕ | ‘bridge’ |

| *dəl | *kɗəl | tû | ‘belly, stomach’ |

| *trɔːʔ | *tərɔʔ | ʦɔ̀ | ‘to hit’ |

Restructuring in Austroasiatic languages sometimes went against the broader trend of stable sesquisyllabism or shift to monosyllabism. Munda languages have dramatically restructured towards a highly agglutinative and synthetic typology, especially in verbal morphology, that can allow speakers to pack informationally rich clauses into single inflected verbs. Less dramatically, Nicobarese languages have added several suffixes to the otherwise modest inventory of affixes, leading to formations that are polysyllabic and do not have stress on the final syllable. Elsewhere, various Austroasiatic languages that lack suffixes permit the accretion of multiple prefixes that allow words of four or even five syllables (without violating iambicity).

Within the confines of the Austroasiatic phonological word template there are also opportunities for segmental/syllabic augmentation. While some languages are happy to tolerate simple presyllables (such that, for example, a single oral or nasal stop may suffice) others require a full presyllable with coda consonant. These codas may be built partially from features of the following main syllable onset, or be copies of the main syllable coda.

2.3.1 Munda: creating disyllabic roots

The Munda languages of India have been characterised as “typologically opposite at every level” to the rest of the phylum (Donegan and Stampe 1983: 337, and elsewhere), having shifted from analytical to synthetic grammar. At the same time their Austroasiatic roots mostly restructured into full disyllables, while some shifted stress forward and lost their original main syllable vowels. The crucial phonological change was that (C)V(C) became the only permitted syllable type, and this was associated with widescale resyllabification. Much of this was achieved by copying main syllable vowels, which in some cases underwent further conditioned changes. Even some Austroasiatic CVC monosyllables become resyllabified in Munda, although why some did and others did not is not clear; a common strategy was to add the copy vowel finally. See examples in (8).

(8)

2.3.2 Extending the sesquisyllabic word template by affixation

Understandably, the strongly sesquisyllabic languages restrict the number of affixes that can be added to a stem, such that phonology consistently overrides morphology. This tendency is arguably violated by cliticisation, which is a fairly marginal phenomenon in much of the phylum, although it is being recognised with increasing frequency (see, for example, Watson 2011). One approach taken by scholars has been to analyse as clitics those morphemes that superficially extend words phonologically beyond the sesquisyllabic template, citing the phonological restriction as evidence for the clitic analysis.

For Bahnar, Banker (1964: 112) identifies a ɟə- ‘completed action’ clitic, explaining that, “[a]ffixes can only occur with one-syllable roots, but the clitic ɟə- is able to occur with two- syllable roots and prefixed stems as well.” Examples are given in (9).

| cəkal ‘to lock door’ | : ɟəcəkal ‘to have locked door’ |

| gənam ‘to threaten’ | : ɟəgənam ‘to have threatened’ |

| Prefixed stems: | |

| pəloc ‘to kill’ | : ɟəpəloc ‘to have killed’ |

| təɓoh ‘to show’ | : ɟətəɓoh ‘to have killed’ |

More elaborate multiple affixation is described for Katu by Costello (1966: 63):

A word in Katu has a maximum of four syllables, made possible when two prefixes are added to a two syllable root. It is expected that some unidentified presyllables will later be found to be prefixes, but until the root of a word is determined, these syllables will be treated as non-morphemic presyllables.

Costello (1966: 63–64) offers the following Katu examples (retranscribed into IPA):

| (10) dalɔːŋ ‘to call’ | : padalɔːŋ ‘to cause to call’ |

| paɟuək ‘to persuade’ | : tapaɟuək ‘to persuade each other’ |

| karuəʔ ‘to hurt’ | : pakaruəʔ ‘to cause to hurt’ |

| saruːm ‘to fall’ | : tapasaruːm ‘to cause each other to fall’ |

The only four-syllable examples offered by Costello are formations with the tapa- ‘involuntary causative’ prefixes, which is a combination of the ta- involuntary and the pa- causative (note that the /a/ vowel in these affixes is a weak epenthesis, the underlying morphemes are consonantal).

Nicobarese languages also allow longer words to be built up by affixation, which also includes a small set of suffixes. According to Radakrishnan’s (1981) analysis of Nancowry, these include -u ‘possessive’ and -a ‘agentive’, and have the effect of marking things which are possessed or which result from some activity or state; see examples in (11).

| (11) kan ‘a female’ | : kanu ‘married’ |

| katəh ‘beneath’ | : katəhu ‘bottom’ |

| wiʔ ‘to make’ | : wiʔa ‘a thing made’ |

| harəŋ ‘to paint’ | : harəŋa ‘the object painted’ |

The addition of further affixes – prefixes and infixes – especially to disyllabic roots, potentially creates four-syllable words. A couple of abridged paradigms taken from Radakrishnan’s lexicon are given in (12).

Another strategy that augments the phonological word by violating the preferred Austroasiatic template is coda copying (also called ‘incopyfixation’ by Matisoff 2003). This is a morphological strategy found productively in Aslian, Nicobarese, and fossilised in Khmuic. When a presyllable is created, such as by prefixing, the main syllable coda is copied into the presyllable to give it a coda.

2.4.1 Nancowry coda copying

Nicobarese languages tolerate only CV(C) syllables, such that any CC sequence is unambiguously indicative of a syllable boundary. In Radakrishnan’s (1981) analysis of Nancowry (which does not discuss semantics), when the prefix ʔu- is attached to monosyllabic roots, a stop or nasal coda is copied into the presyllable (with regressive dissimilation of palatals). Examples are given in (13).

| (13) jak > | ʔukˈjak ‘to conceive’ |

| kap > | ʔupˈkap ‘to bite’ |

| ʔiŋ > | ʔuŋˈʔiŋ ‘bone’ |

| tin > | ʔinˈtin ‘to push’ |

| cɯc > | ʔitˈcɯc ‘to be silent’ |

2.4.2 Aslian coda copying

Among the Aslian languages of Malaysia more elaborate coda copying is attested; Matisoff (2003: 28–32) distinguishes several types illustrated in (14).

2.4.3 Khmuic coda copying

Apparently we find fossilised copy codas in the Khmuic languages of Northern Laos and neighbouring areas. Some Khmu Cuang examples from Premsrirat’s (2002) dictionary follow in (15).

| (15) dɔŋ dɔŋ kmɲaːm | ‘pointed tuft of hair’ |

| gləʔ suɲruɲ | ‘curly and spongy hair’ |

| hɛːt cŋriəŋ | ‘to scream’ |

| hiəŋ klweːl | ‘black (a shade of)’ |

| hʔɨr stŋut | ‘very fragile’ |

The Khmu examples perhaps suggest a phonological mechanism for the origin of coda copying. Generally, the examples are in expressive or descriptive lexicon; we might think of the copied codas as phonological bulk in new syllables that were given form by rhyming. Rhyming of other segments is common in two- and four-syllable elaborate expressions.

2.5.1 Epenthesis with presyllables in South Bahnaric

In South Bahnaric languages there is a strong tendency for voiced stops to become prenasalised, creating a nasal presyllable coda, when stop prefixes are attached to roots with voiced initials (see Sidwell 2000 for further discussion). Some examples are given in (16), with comparisons to Bahnar, a Central Bahnaric language that does not share this epenthesis.

| (16) Stieng | kəmbɔŋ | ‘bill (of bird)’ | Stieng | səŋgər | ‘drum’ |

| Sre | kəmboŋ | ‘large bill of bird’ | Sre | səŋgər | ‘drum’ |

| Bahnar | təɓɔ:ŋ | ‘snout’ | Bahnar | səgər, həgər | ‘drum’ |

Another example of presyllable epenthesis in South Bahnaric involves the resyllabification of diphthongs in Chrau and Central Mnong. For etymological *iə, *uə, a rhotic onset triggers resyllabification. Interestingly in Bahnar the same environment triggers monophthongisation; see (17).

2.5.2 Epenthesis of monosyllables in Gta’

Anderson (2008) presents a sketch grammar of Gta’, a small Munda language of southern Orissa with fewer than 4,500 speakers. Several distinct varieties are spoken, including a Hill Gta’ and a Plains Gta’. The language and people are also called Didayi or Didei. As Anderson reports, Gta’ undoes much Munda restructuring, restoring sesquisyllabicity:

Gta’ is an unusual language from the perspective of syllable structure or phonotactics. It has an enormous number of ‘clusters’ found in word-initial position but a restricted number of consonants found in coda position. A small number of words with syllabic nasals and prenasalized stops may also be found.

(Anderson 2008: 684–685)

Apparently both Munda disyllables and monosyllables restructured to CCV(C), and Munda with simple CVC monosyllables appending a homorganic augment, even when the onset is itself nasal. Anderson characterises these as pseudo-archaisms; see (18).

(18) Gta’ epenthetic prenasalisation of monosyllables (examples from Anderson 2008 compared to Remo and Proto-Austroasiatic reconstructions)

| Gloss | Gta’ | Remo | Proto-Austroasiatic (Shorto 2006) |

| ‘two’ | mbar | bar | *ɓaːr |

| ‘nose’ | mmu | seː-mi | *muh |

| ‘bone’ | ncia | saŋ | *cʔaːŋ |

| ‘foot’ | nco | suŋ | *ɟu(ə)ŋ |

| ‘water’ | nɖiaʔ | ɖag | *ɗaːk |

| ‘root’ | nɖræʔ | regi | *ris |

| ‘hand’ | nti, tti | ti | *tiːʔ |

| ‘deep’ | cri | siri | *ɟruːʔ |

| ‘uncultivated land’ | bri | biri | *briːʔ |

| ‘long/tall’ | clæʔ | sileŋ | *ɟla(i)ŋ |

| ‘rope’ | ghæʔ | gieʔ/gije | *ks(i)ʔ |

| ‘uncooked rice’ | rkoʔ | rŋku | *rk(aw)ʔ |

| ‘village’ | hni | suŋ | *sŋiʔ |

| ‘sun’ | sni | siŋi | *tŋiːʔ |

Proto-Austroasiatic is reconstructed with a three-way phonation contrast in main syllable onset oral stops – voiceless, voiced and voiced implosive (Shorto 2006), with all three series surviving intact into Old Mon, Katu, and at least partially in Bahnar, and is reconstructable on internal grounds for five out of the dozen Austroasiatic branches (Palaungic, Vietic, Katuic, Bahnaric, Monic; see Sidwell 2010 for correspondences and discussion). It is fair to say that to a great extent the phonological history of Austroasiatic is dominated by the restructuring of these contrasts, and their secondary consequences (especially in respect of vocalism).

3.1.1 Merger of voiced and implosive series

Five out of a dozen branches show a complete merger of voiced and implosive stops at the proto-branch level: Munda, Khmuic, Khmer, Pearic and Aslian, plus Nicobarese shows a merger restricted just to bilabials. The merger of implosive and voiced series is typically an unconditioned change that can be characterised as a lenition. It was followed by various secondary changes in individual branches.

• In Munda and Aslian the merger resulted in a stable two-series contrast (±voice) in onset oral stops, with only isolated cases of subsequent further change.

• In Khmuic, the Khmu Chuang dialect retains a ±voiced contrast, while most other Khmuic languages have subsequently undergone a general devoicing of stops associated with tonogenesis.

• Pre-Khmer, implosion was lost, but later remerged in a conditioned shift of voiceless stops.

• In Pearic languages the merged voiced series later devoiced in association with the emergence of breathy registers.

3.1.2 ‘Germanic’ sound shift

Pearic, and various northern groups, have undergone a so-called (by Haudricourt 1965) ‘Germanic’ sound shift in which the voiceless series acquires a positive voice onset timing, becoming aspirated. Apparently the increased VOT serves to improve perceptual distance from the implosive series, which tends to have a rather short lead voicing duration. The Germanic shift has occurred in Mal/Thin (Khmuic), Angkuic, Khasi, and Pearic, although with some exceptions that are problematic to explain (marked with † below). See (19) for examples.

3.1.3 Restoration of implosives

In several branches (Khmeric, Vietic, Palaungic) a restructuring of the consonant series after loss of implosion has resulted in a restoration of implosion, both conditioned and unconditioned.

The phonological history of Khmer is rather well understood (e.g. Ferlus 1992). The Austroasiatic implosive series was lost before inscriptional Old Khmer appeared in the sixth century, reflecting a merger of implosives and plain voiced stops (e.g. Proto-Austroasiatic *ɗa:k > Old Khmer dik ‘water’, Proto-Austroasiatic *ɓa:r > Old Khmerber/vyar ‘two’). Subsequently (perhaps early in the Middle Khmer period) there was a further shift in which prevocalic labial and apical voiceless stops became implosives. Examples are given in (20).

| (20) Proto-Austroasiatic | Modern Khmer |

| *piʔ | > ɓɤj ‘three’ |

| *tiʔ | > ɗɤj ‘earth’ |

| *tpal | > tɓal ‘mortar’ |

| *pta:w | > pɗaw ‘rattan’ |

In Vietic (see Phan [2012] for a recent discussion of Vietnamese historical phonology) there was a general devoicing of stops throughout the group. The imploded series survived as stops in most minor Vietic languages, but lenited to /v/ and /r/ in some Muong dialects (e.g. Muốt, Chỏi), and became nasals /m/ and /n/ in Vietnamese. The gap left by the loss of implosives was subsequently refilled by a general shift of /p, t/ to /ɓ, ɗ/, including /p, t/ that had previously originated in the devoicing of voiced oral stops. Examples illustrating the loss and reemergence of implosives in Vietnamese are given in (21).

Within Palaungic at least one language underwent a shift in which voiceless labials and apicals became voiced implosives. Luce (1965) provides a short lexion of ‘Palaung of Panku’ recorded at Panku in Shan State (also reporting ‘Ra-ang’ as the autonym of this group). That lexicon provides clear examples of the labial and apical voiceless stops becoming implosive while the palatal and velar had the otherwise regular Palaungic outcomes (*c- > /s-/, *k- > /k-/); see (22).

(22)

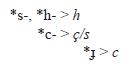

Throughout Austroasiatic there is a strong tendency to lenite palatals in onsets, varying greatly even within individual branches. It is important to note in this context that the phoneme typically transcribed as /s/ in Austroasiatic linguistics often has a considerable allophonic range that includes alveopalatal/laminal articulation (/ɕ, ʃ/) or even palatal (/ç/), and this is not always evident from the written sources.

The general pattern is one of a chain shift that proceeds partly or completely as follows:

Paul Sidwell

Variations on this pattern include the following:

• In East Bahnaric (Cua) a shift of *s > /ɬ/ followed by *c > /s/.

• In Mang a shift of *s > /h/ followed by *c > /Ɵ/.

• In Danaw a shift of *s > /Ɵ/ followed by merger of *c, *ɟ > /ʦ/.

• In Munda a tendency for s > zero (and k > /h/) followed by shift of *c > /s/.

Examples of palatal lenition across Austroasiatic are shown in (23).

(23)

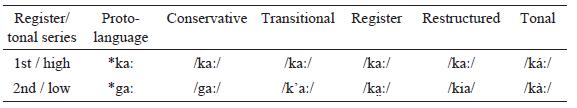

The Austroasiatic languages are well known for their complex vocalism, and examples with inventories of 40 or more vowel phonemes are known (see section 4.1.1). The essential mechanism behind such complexity is the splitting of vowel systems into high and low ‘registers’ by the assimilation of consonant phonation features, with concomitant diphthongisations or other vowel shifts characteristic of each register series. The processes can variously lead to languages becoming tonal and/or acquiring ‘restructured’ vocalism in the terminology of Huffman (1985), who schematised the evolution of two hypothetical proto-syllables *ka: and *ga:5

(24)

Over subsequent decades a more complete understanding of the laryngeal mechanisms underlying these patterns of change has emerged, and our present understanding of both tonogenesis and registrogenesis is now quite advanced (see: Brunelle 2005; Gordon and Ladefoged 2001; Ladefoged and Maddieson 1996; Mortenson 2006; Thurgood 2002, 2007). From language to language, different features or combinations of features gain or lose salience in the process of restructuring. Thurgood tabulates these phonetic correlates of register as follows.

| Tense Register | Unmarked | Breathy Register | |

| original initials: | proto-voiceless | proto-voiced | |

| voice quality: | tense (creaky) | modal (clear) | breathy |

| vowel quality: | lower (open); more fronted vowels; tendency to diphthongisation; often shorter | higher (closed); more backed vowels; tendency to centralisation; often longer | |

| pitch distinctions: | higher pitch | lower pitch | |

| state of larynx: | larynx tense and/or raised (reduced supraglottal cavity) | larynx lax and/or lowered (increased supraglottal cavity |

Consequently we are now much better placed to understand the nature of the complex phonologies encountered in Austroasiatic, and model their emergence from the simpler system of Proto-Austroasiatic, which presumably resembled closely one or more of the extant apparently unrestructured conservative Austroasiatic languages.

4.1.1 Restructured vocalisms of Khmer, Mon and Bru

The topics of vowel splitting and register formation are so intimately linked that it is difficult to treat them separately. As can been seen in Thurgood’s table of ‘most common register complexes’ in (25), there is a correlation between vowel height and phonation. The basis of this relationship is articulations that serve to increase or decrease the volume of the immediate supra-laryngeal chamber such that voiced onsets tend to suppress F1, and thus condition higher vowels (Brunelle 2005). The effect may be quite subtle, for example there may be no effect on /i, u/, but /e, o/ may be pronounced with perceptibly raised onglides, e.g. [ɪe, ʊo]. Conversely, voiceless onsets may condition lowering, such that /i, u/ are realised as [ei, ou] or similar. These effects can lead to most or all of the vowel inventory bifurcating according to the voice quality of the onset, so that not only do rhymes acquire a distinct phonation (e.g. breathy versus model, etc.) but also distinctive timbre. Languages may be in the midst of such transitions, and consequently the analyses can be difficult or ambivalent; for example researchers may treat one or other feature of the emerging system as subphonemic.

The classic examples of Austroasiatic vowel splitting and registrogenesis are Mon and Khmer. In each case the languages were reduced to writing before the relevant sound changes occurred – when they were still phonologically conservative in Huffman’s terminology – and this is reflected in the epigraphic record and the modern orthographies. These days Khmer is in the category of a fully restructured language, having lost the breathy contrast (although it survives in Cardamom/Chanthaburi Khmer; see Wayland and Jongman [2001]), leaving only the distinct vowel reflexes. Although the inventory effectively doubled with the vowel split, some positional mergers left a system with only some 30 members distinguished (while similar process have yielded more than 40 in some Katuic languages). The split, as it affected the long vowels, is represented schematically by Huffman (with some notational adaptation) as in (26).

(26) Vowel split among long monophthongs in Khmer (based on Huffman [1985: 142])

Note: vowels in italics are historical values indicated by the writing system.

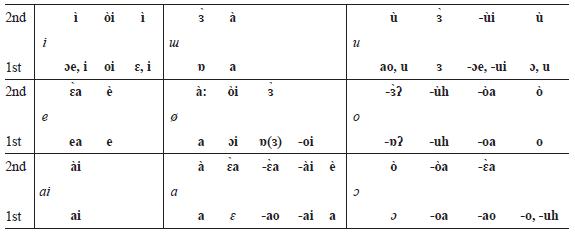

The history of Mon is quite different, to a large extent because the quantity distinction was lost while the breathy-modal register was maintained. This resulted in many mergers such that today there are phonetically only ten monophthongs and eight diphthongs, yet potentially all of these may be breathy or modal. This puts Mon into Huffman’s ‘Register’ category. The phonological evolution of Mon is well researched (e.g. Diffloth 1984; Ferlus 1983; Shorto 1971, 2006) and although one will find various notational discrepancies and minor differences of analysis between various authors, there is broad agreement on the details of how the complex phonetics of Modern Spoken Mon emerged from the apparently much simpler Old Mon system. To illustrate this history, I have reconfigured the table of “Mon historical developments” from Shorto (2006: 6) along the lines of Huffman’s (1985) schema for representing vowel splits.

(27) Summary vowel splits in the transition from Old Mon to Modern Spoken Mon (adapted from Shorto 2006: 6)

Note: vowels in italics are historical values indicated by the writing system.

We see in Mon that the second register vowels are higher (having a lower F1) than their corresponding first register members (such as /ɔ/ (1st), /ò/ 2nd). It is also important to note that there remain plenty of register pairs that are so similar in vowel quality that phonation remains salient, and is an important part of the contemporary phonology.

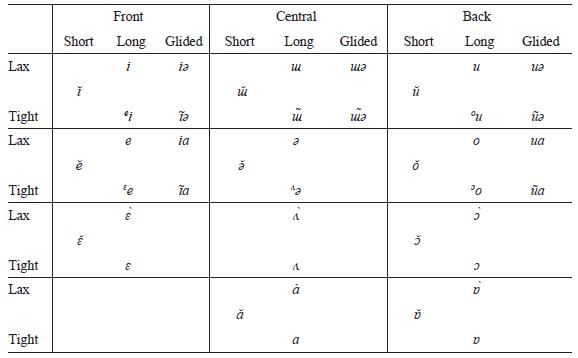

Another Austroasiatic language exemplifying such changes is Bru (also Bruu, Brôu, Brũ), a West Katuic language with many closely related dialects spoken across a large area from Northeast Thailand, through Laos and into Vietnam. Remarkably, various analyses count up to 42 distinct vowel phonemes in Bru (e.g. Chinowat 1983; Gainey 1985; Luang-Thongkum and Puengpa 1980; Luang-Thongkum 1979; Miller and Nưan 1974; Phillips et al. 1976; Vương Hoàng Tuyên 1963; Vương Hừu Lễ. 1999). In the most recent of these papers, Vương Hừu Lễ compares several analyses, discussing their merits. I reproduce in (28) his “Chart of Bru vowels arranged by register contrasts,” showing a system structurally somewhere between Khmer and Mon; length remains important and short vowels are unmarked for register, while among the long vowels splitting is restricted to the high and mid-high series only, leaving register most salient for the low and mid-low. Consequently, speakers of Bru must track an asymmetrical combination of quantity, small quality (ongliding) distinctions, phonation, and even nasalisation. We may expect that such a system is likely to be unstable over the longer term, and may eventually settle down through losses/merges into one of Huffman’s less ambiguous categories.

(28) Chart of Bru vowels adapted from Vương Hừu Lễ (1999: 105)

Note: Lax/tight corresponds to 2nd/1st registers; short vowels are unmarked for register.

4.2.1 Conventional tonogenesis

Tonal languages are not particularly common within Austroasiatic, unsurprisingly given the relative stability of sesquisyllabism, but they do occur, often in conditions of close contact with other tonal languages such as Chinese, Thai or Burmese. However, even when they do occur in such language contact conditions, it is generally apparent that the native resources of the language have played the dominant role in conditioning the paths and outcomes of tonogenesis. For example, in the case of tonal Khmu dialects, language contact can be more or less ruled out as the primary driver of tonogenesis. Premsrirat (2002, 2004) discusses tonogenesis in Khmu, a large Austroasiatic dialect chain that is spread over much of Northern Laos and spills into neighbouring countries. While the eastern dialects are phonologically conservative, western dialects show all of Huffman’s stages including tonality, specifically simple high/low tone systems.

(29) Abridged version of Premsrirat’s (2004: 14) Khmu “Stages of tonogenesis: words with initial stop,” illustrating various transitional stages to tonality in extant Khmu dialects

| 1. Beginning stage: | 2. Intermediate stage: | 3. Final stage | ||

| ls, vt, cl | lk, tw | lb | ct | |

| Voicing contrast | Register contrast | Tone contrast with aspirated initial | Tone contrast | |

| ‘rice wine’ | buːc | pṳːc | phùːc | pùːc |

| ‘to take clothes off’ | puːc | puːc | púːc | púːc |

| ‘to cut down a tree’ | bok | po̤k | phòk | pòk |

| ‘to take a bite’ | pok | pok | pók | pók |

| ‘to chew’ | buːm | pṳːm | phùːm | pùːm |

| ‘to fart’ | puːm | puːm | púːm | púːm |

| ‘to weigh’ | ɟaŋ | ca̤ŋ | chàŋ | càŋ |

| ‘astringent’ | caŋ | caŋ | cáŋ | cáŋ |

Dialects: ls Hua Phan, vt Nghệ-An, cl Pung Soa Sipsongpanna, lk Nalae Udomsaj, tw Chiengkhong, lb Muang Hun Udomsaj, ct Om Kae Sipsongpanna.

The basic pattern of high/low tone series emerging from voicing in onsets can be further modified by the effects of codas. The best known example of this in Austroasiatic is Vietnamese, whose tones were first explained by Haudricourt (1954), who showed that it has little to do with the five and six tone southern Chinese varieties with which Vietnamese has long been in contact with and often compared to typologically. Example (30) from Diffloth (1989: 146) shows in simplified form the correlation between tones and segmental features in the history of Vietnamese.

(30) Summary development of Vietnamese tones from Diffloth (1989: 146)

| Finals: | *voiced continuants | *stops, *-ʔ | *voiceless fricatives | |

| Initials: | ||||

| *voiceless | v (ngang) | v́ (sắc) | v̉ (hỏi) | |

| *voiced | v̀ (huyên) | ṿ (nặng) | ṽ (ngã) |

A further case in point: Bolyu and Bugan, small Austroasiatic languages spoken in the far west of the Guangxi (China); both are heavily Sinosised languages with complete reduction to monosyllables and both have six tone systems. However, Edmondson and Gregerson (1996) and Li Jinfang (1996) show that the tones in these languages pattern in ways that strongly parallel Vietic, providing additional strong indications that although being in contact with a dominant tonal language may be a factor in tonogenesis, the specific phonological developments will be largely governed by internal factors.

4.2.2 Unconventional tonogenesis

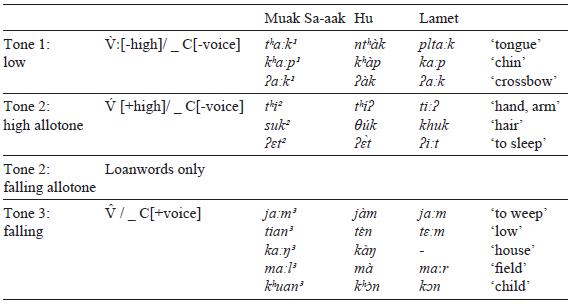

Another Austroasiatic group in which tones are important is the Angkuic sub-branch of Palaungic, spoken by small communities in Yunnan and broader areas. Work in recent decades has revealed a fascinating story of syllabic, segmental and tonal restructuring that runs counter to the immediate areal trends. Three languages are discussed here: U and Hu (Svantesson 1988, 1989, 1991) and Muak Sa-aak (Hall 2010). The striking thing about the Angkuic languages is that devoicing among initial stops must have occurred at an early period in the group’s history, such that it is unconnected with tonogenesis, and instead vowel length appears to be the crucial feature that separated high and low tone series, with codas conditioning further splits. This is very unusual. Kingston (2011) could only nominate Western Lugbara (Nilo-Saharan) as another example tone originating with length.

Discussion begins with Hu, which shows a straightforward two-tone high/low system. Svantesson (1991: 75) shows the relation between tone and vowel length (mean values only shown), which I compare to Lamet, a more distantly related Palaungic language that preserves Proto-Palaungic vowel length; see (31).

| Hu | Mean durations by rime | Lamet | Glosses | |

| jám | 126 ms | jam | ‘to die’ | |

| High tone | páp | 102 ms | – | ‘to speak’ |

| kák | 117 ms | kak | ‘to bite’ | |

| jàm | 200 ms | jaːm | ‘to cry, weep’ | |

| High tone | kàp | 120 ms | kaːp | ‘jaw’ |

| ʔàk | 188 ms | ʔaːk | ‘crossbow’ |

Svantesson’s measurements show that length distinctions have not completely levelled in Hu; the Hu measurements effectively show all vowels falling within the typical range of Austroasiatic long vowels, with high tone vowels in the lower end of the range while low tone vowels distribute over a wider range. It is apparent that within Hu, the vowel quantity distinction is being lost with short vowels lengthening until they merge phonetically with the long series. This is consistent with a broader view that among Austroasiatic languages long tends to be the unmarked length. Elsewhere in Austroasiatic for example, Vietnamese retains only two short vowels (/ă, ə̆/) versus nine long monophthongs and three diphthongs, while Sedang (Smith 1979) neutralised quantity by lengthening all short monophthongs.

The closely related U language underwent even more extensive restructuring, especially reduction of syllables (Svantesson 1988). Importantly, the basic two-tone system underlying Hu elaborated considerably into a four-way high/low/rising/falling contrast. However, the emergence of four tones in U was not simple; there are nine distinct outcomes according to different rimes, which then sort out into an overall four-way tone system. Putting aside two marginal cases, the broad picture of tonal development in U, with conditioning environments specified, is as in (32).

The other Angkuic language for which we have good data and analysis is Muak Sa-aak. In Hall’s (2010) thesis it is described as having three tones as follows:

• Tone 1: low tone with tense phonation, not consistently creaky.

• Tone 2: so called ‘checked tone’, high pitch on short open syllables and with stop codas, and falling pitch on long open syllables and with nasal codas.

• Tone 3: high falling tone occurring only with sonorant codas and open syllables (’live’ syllables).

Hall’s analysis is extensive, but is principally synchronic; stripping out Shan loanwords important asymmetries emerge, allowing us to establish that there is a clear connection between etymological vowel length and tone. The basic relations are tabled in (33), again with reference to Lamet comparisons.

(33) Muak Sa-aak tonal developments (based on Hall 2010)

Strikingly it appears that quantity played only a marginal role in Muak Sa-aak tonogenesis, instead voice quality of codas and vowel height in syllables with voiceless or zero codas, recalling part of the complex phonological history of U.

4.3.1 Coda depalatalisation

An important feature of Austroasiatic is that historically palatal stops and nasals are frequent syllable codas, whereas it is common in other language phyla of the region to lack these entirely. Nonetheless, it is quite common for Austroasiatic languages, sometimes apparently in the context of contact with dominant national or trade languages, to lose their palatal finals, usually by merger with apical or velar series, or sometimes by dissimilation/feature shuffling. Split reflexes, such as oral stops > apical while nasals > velar, or even split reflexes for a given manner of articulation, occur frequently. Examples are in (33).

(33) Depalatalisation of codas across Austroasiatic

4.3.2 Coda denasalisation

Some geographically southern Austroasiatic languages (Aslian, Nicobarese) show a hardening of nasal codas, variously to prestopped nasals or oral stops. At least once the opposite also happened; in Jah Hut the nasal codas are preserved and the stops unpack into post-glottalised nasals (e.g. /mat/ ‘eye’ [mãnʔ]). The phenomenon is discussed in detail by Matisoff (2003: 19–22), whose account includes the following:

• In most Semai dialects, Proto-Aslian final *nasals have been completely denasalised.

• In Sabum denasalisation is correlated with the length of the preceding vowel: complete after *short vowels, but only partial after *long.

• In a Temiar final *nasals are completely occlusivised, usually to voiceless stops – but in dialects where the original *stops did not voice, the final *nasals became voiced stops.

• Northern Temiar distinguishes three types of double articulated coda; e.g. -pm̥, -bm̆, -bm reflecting Proto-Aslian *V̆m, *Vp, *Vm respectively.

Additionally, the Shom Pen language of the Nicobar shows denasalisation of codas. The following comparisons in (34), taking forms from Chattopadhyay and Mukhopadhyay (2003), are indicative.

| Shom Pen | Proto-Austroasiatic (Shorto 2006) |

| kāʔeem ‘bone’ | *cʔaːŋ ‘id.’ |

| khoāg ‘boiling’ | *guəŋ ‘to cook in water’ |

| ceog ‘foot’ | *ɟəːŋ ‘id.’ |

| peāg ‘cockroach’ | *ɓiəŋ ‘spider’ |

| cuoid ‘heavy’ | *ɟən ‘id.’ |

| leɔb ‘leech’ | *tləːm ‘id.’ |

| tiub ‘blood’ | *ɟhaːm ‘id.’ |

| hoɔp ‘wash, clean’ | *huːm ‘bathe’ |

Much of what is surveyed in this chapter can be conceptualised as bringing structural symmetry to the otherwise highly asymmetrical sesquisyllables. Processes include loss of presyllables by elision or assimilation that reduce morphemes and words to simpler monosyllables, and the restructuring of syllables into simple repeated units that support polysyllabic morphemes and morphologically complex words. Additionally there are tendencies that run counter to this drive for symmetry, and can result in direct augmentation of the sesquisyllabic template, producing greater structural asymmetry. The motivations and explanations for these various changes, and conflicting directions of change, surely lay in complex interplays between linguistic tendencies and the dynamics of languages contact, topics too vast to be treated in meaningful detail here.

1 The widely received division of Austroasiatic into primary Munda and Mon-Khmer is without historical foundation and is rejected outright by this author (see Sidwell and Blench 2011). The view originated as a misinterpretation of the typological division of Austroasiatic by Pinnow (1960/1963).

2 In present day languages where the timbre of presyllable vowels is important, such as in the so-called case-marking forms of Ta-ioh (Solntseva 1996) or the person marking prefixes/clitics in Palaung (Milne 1921), a secondary origin is clearly evident in the form of absorbed pronouns or similar grammaticalisation.

3 Note that Katu continues unchanged from Proto-Austroasiatic; it actually permits up to four syllables in morphologically complex forms (although some morphemes are better analysed as clitics, such as the individuating m- from muj ‘one’, e.g. com ‘cup’, macom ‘one cup’), and as Proto-Austroasiatic glottal stop codas were lost in Katuic open syllables are permitted.

4 All the Proto-Austroasiatic reconstructions are from Shorto’s (2006) Proto-Mon-Khmer, which for the present purposes is treated as equivalent to Proto-Austroasiatic. This is a reasonable approach if one accepts, as I do, that the marked characteristics of Munda languages are essentially entirely innovative vis-a-vis Proto-Austroasiatic.

5 Note that minor notational changes have been made to bring the forms more into line with IPA.

Anderson, Gregory (ed.). 2008. The Munda languages. London: Routledge.

Donegan, Patricia and David Stampe. 2004. Rhythm and the synthetic drift of Munda. In Rajendra Singh (ed.) The yearbook of South Asian languages and linguistics. Berlin: de Gruyter, 3–36.

Shorto, Harry L. 2006. A Mon-Khmer comparative dictionary. [edited by: Paul Sidwell, Doug Cooper and Christian Bauer] Canberra: Pacific Linguistics.

Sidwell, Paul. 2011. Comparative Mon-Khmer Linguistics in the 20th century: where from, where to? In K. S. Nagaraja (ed.) Austro-Asiatic linguistics: in memory of R. Elangaiyan. Mysore: Central Institute of Indian Languages, 38–104.

van Driem, George. 2001. Languages of the Himalayas, Volume 1. Leiden: Brill.

Alves, Mark J. 2000. The current status of Vietnamese genetic linguistic studies. In The Fifth International Symposium on Languages and Linguistics. Ho Chi Minh City: Vietnam National University and Ho Chi Minh City University of Social Sciences and Humanities, 6–17.

Anderson, Gregory (ed.). 2008. The Munda languages. London: Routledge.

Banker, Elizabeth M. 1964. Bahnar Affixation. Mon-Khmer Studies 1: 99–117.

Banker, Elizabeth M., Sip and Mơ. 1973. Bahnar Language Lessons (Pleiku Province). Trilingual Language Lessons, No. 20. Manila: Summer Institute of Linguistics.

Benedict, Paul K. 1990. How to Tell Lai: An exercise in classification. Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area. 13(2):1–26.

Bisang, W. 1996. Areal typology and grammaticalization: processes of grammaticalization based on nouns and verbs in South-East Asian languages. Studies in Language 20(3): 519–597.

Blench, Roger and Paul Sidwell. 2011. Is Shom Pen a Distinct Branch of Austroasiatic? In Sophana Srichampa, Paul Sidwell and Kenneth Gregerson (eds.) Austroasiatic Studies: papers from the ICAAL4: Mon-Khmer Studies Journal Special Issue No. 3. Dallas: SIL International; Canberra: Pacific Linguistics and Salaya: Mahidol University, 90–101

Brunelle, Marc. 2005. Register in Eastern Cham: phonological, phonetic and sociolinguistic approaches. PhD dissertation, Cornell University.

Brunelle, Marc and Pittayawat Pittayaporn. in press. Phonologically-constrained change: the role of the foot in monosyllabization and rhythmic shifts in Mainland Southeast Asia. Diachronica.

Chattopadhyay, Subhash Chandra and Asok Kumar Mukhopadhyay. 2003. The language of the Shompen of Great Nicobar: a preliminary appraisal. Kolkata: Anthropological Survey of India.

Chinowat, Ekawit. 1983. Su̧ ksā Prīap Thīap Withī Sāng Kham Nai Phāsā Kūy, Brū, Lae Sō. [A comparative study of the morphological processes of Kui, Bruu and So]. MA dissertation, Chulalongkorn University.

Costello, Nancy A. 1966. Affixes in Katu. Mon-Khmer Studies 1: 63–86.

——1971. Ngữ-vựng Katu: Katu vocabulary. Saigon: Department of Education. [Summer Institute of Linguistics Dallas Microfiche]

——1991. Katu Dictionary (Katu-Vietnamese-English). Dallas: Summer Institute of Linguistics.

Davis, John J. 1968. Nyaheun Phonemes. Paxse, Laos: Overseas Missionary Fellowship. [Copy held at Summer Institute of Linguistics Bangkok file 495.955(6)]

——1973. Notes on Nyaheun grammar. Mon-Khmer Studies, 4: 69–75.

Diffloth, Gérard. 1984. The Dvaravati-Old Mon language and Nyah Kur (Monic Language Studies 1). Bangkok: Chulalongkorn University Printing House.

——1989. Proto-Austroasiatic Creaky Voice. Mon-Khmer Studies 15: 139–154.

——2005. The contribution of linguistic palaeontology to the homeland of Austro-asiatic. In Laurent Sagart, Roger Blench and Alicia Sanchez-Mazas (eds) The peopling of East Asia: putting together archaeology, linguistics and genetics. London: Routledge Curzon, 79–82.

Donegan, Patricia. 1993. Rhythm and vocalic drift in Munda and Mon-Khmer. Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area 16(1): 1–43.

Donegan, Patricia and David Stampe. 1983. Rhythm and holistic organization of language structure. In John F. Richardson, Mitchell Lee Marks and Amy Chukerman (eds) Papers from the Parasession on the Interplay of Phonology, Morphology and Syntax. Chicago: Chicago Linguistic Society, 337–353.

Donegan, Patricia and David Stampe. 2004. Rhythm and the synthetic drift of Munda. In Rajendra Singh (ed.) The yearbook of South Asian languages and linguistics. Berlin: de Gruyter, 3–36.

Edmondson, Jerold and Kenneth Gregerson. 1995. Bolyu tone in Vietic perspective. Mon-Khmer Studies 26: 117–134.

Edmondson, J. A and K. Gregerson. 1996. Bolyu tone in Vietic perspective, Mon-Khmer Studies 26: 117–133.

Enfield, N. J. 2003. Linguistic epidemiology: semantics and grammar of language contact in mainland Southeast Asia. London: RoutledgeCurzon.

——2005. Areal linguistics and mainland Southeast Asia. Annual Review of Anthropology, Vol. 34, 181–206.

——2011. Linguistic diversity in mainland Southeast Asia. In N. J. Enfield (ed.) Dynamics of human diversity: the case of mainland Southeast Asia. Canberra, Pacific Linguistics. 63–80.

Ferlus, Michel. 1971. Simplification des groupes consonantiques dans deux dialectes austroasiens du sud-Laos. Bulletin de la Société de Linguistique de Paris 66: 389–403.

——1983. Essai de phonétique historique de môn. Mon-Khmer Studies 12: 1–90.

——1992. Essai de phonétique historique du khmer (Du milieu du premier millénaire de notre ère à l’époque actuelle), Mon-Khmer Studies 21: 57–89.

——1997. Problèmes de la formation du systèm vocalique du vietnamien. Cahiers de Linguistique, Asie Orientale 26(1): 37–51.

——1998. Les systèmes de tons dans les langues viet-muong. Diachronica 15(1): 1–27.

——2004. The orign of tones in Viet-Muong. In S. Burusphat (ed.) Papers in the Eleventh Annual Meeting of the Southeast Asian Linguistic Society. Tempe, Arizona: Arizona State University, Program for Southeast Asian Studies, 297–313.

——2007 Lexique de racines Proto Viet-Muong (Proto Vietic Lexicon). Unpublished Ms. [Available online at http://sealang.net/monkhmer/database/; Accessed 6 November 2013].

Gainey, Jerry. 1985. A comparative study of Kui, Bruu and So phonology from a genetic point of view. MA dissertation, Chulalongkorn University.

Gordon, Matthew and Peter Ladefoged. 2001. Phonation types: a cross-linguistic overview. Journal of Phonetics 29: 383–406.

Hall, Elizabeth. 2010. A Phonology of Muak Sa-aak. MA dissertation, Payap University Thailand.

Haudricourt, André-Georges. 1952. L’origine môn-khmèr des tons en viêtnamien. Journal Asiatique 240: 264–265.

——1954. De l’origine des tons en viêtnamien. Journal Asiatique 242: 69–82.

——1965. Mutation consonantique en Mon-Khmer. Bulletin de la Société Linguistique de Paris 60: 160–172.

Henderson, Eugénie J. A. 1985. Feature shuffling in Southeast Asian languages. In Suriya Ratanakul, David D. Thomas and Suwilai Premsrirat (eds) Southeast Asian Linguistic Studies Presented to André-G. Haudricourt. Bangkok: Mahidol University, 1–22.

Huffman, Franklin E. 1977. An examination of lexical correspondences between Vietnamese and some other Austro-Asiatic languages. Lingua 43: 171–198.

——1985. Vowel permutations in Austroasiatic languages. In Graham Thurgood, James A. Matisoff and David Bradley (eds) Linguistics of the Sino-Tibetan Area: the state of the art. Papers presented to Paul K. Benedict for his 71st birthday. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics, 141–145.

Kingston, John. 2011. Tonogenesis. In Marc van Oostendorp, Colin J. Ewen, Elizabeth Hume and Keren Rice (eds) Blackwell Companion to Phonology, Volume 4: Phonological interfaces. Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishing, 2304–2333.

Ladefoged, Peter and Ian Maddieson. 1996. The sounds of the world’s languages. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Li, Jingfang. 1996. Bugan: a new Mon-Khmer language of Yunan Province, China. The Mon-Khmer Studies Journal 26: 135–159.

Luce, Gordon H. 1965. Danaw, a dying Austroasiatic language. Lingua 14: 98–129.

Matisoff, James. 1973. Tonogenesis in Southeast Asia. In Larry M. Hyman, (ed.) Consonant Type and Tones: Southern California Occasional Papers in Linguistics, 71–95.

——1978. Variational Semantics in Tibeto-Burman: the ‘organic’ approach to linguistic comparison. Occasional Papers of the Wolfenden Society on Tibeto-Burman Linguistics, Volume VI. Publication of the Institute for the Study of Human Issues (ISHI), Philadelphia. xviii + 331 pp.

Matisoff, James. 2003. Aslian: Mon-Khmer of the Malay Peninsula. Mon-Khmer Studies 33: 1–58.

Migliazza, Brian. 1996. Mainland Southeast Asia: a unique linguistic area. Note on Linguistics, 17–25.

Miller, Carolyn. 1974. Bru language lessons. Trilingual Language Lessons, No.13, part 2. Manila: Summer Institute of Linguistics.

Milne, Leslie. 1921. An elementary Palaung grammar. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Mortenson, David. 2006. Tonally conditioned vowel raising in Shuijingping Hmong. Handout from the LSA 80th Annual Meeting, Albuquerque, New Mexico. January 6, 2006.

Nguyễn Hữu, Hoành. 1995. Katu language word formation. Data Papers on Minority Languages of Vietnam. Hanoi: Nhả xuất bản Khoa học Xã hội.

Nguyễn Văn, Lợi. 2008. Tiếng Mảng. Hanoi: Nhả xuất bản Khoa học Xã hội.

Parkin, Robert. 1991. A guide to Austroasiatic speakers and their languages. Oceanic Linguistics Special Publications No. 23. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

Phan, John. 2012. Mường is not a subgroup: phonological evidence for a paraphyletic taxon in the Viet-Muong sub-family. Mon-Khmer Studies 40: 1–18.

Phillips, Richard L., John D. Miller, Carolyn P. Miller. 1976. The Brũ vowel system: alternate analyses. The Mon-Khmer Studies Journal 5: 203–218.

Pinnow, Heinz-Jürgen. 1963. The position of the Munda languages within the Austroasiatic language family. In H. L. Shorto (ed.) Linguistic comparison in Southeast Asia and the Pacific. London: SOAS, 140–152.

Premsrirat, Suwilai. 2002. Thesaurus of Khmu dialects in Southeast Asia. Bangkok: Mahidol University.

——2004. Register complex and tonogenesis in Khmu dialects. The Mon-Khmer Studies Journal 34: 1–17.

Radhakrishnan, R. 1981. The Nancowry word: phonology, affixual morphology and roots of a Nicobarese language. Edmonton, Alberta: Linguistic Research Inc.

Shorto, Harry L. 1971. A dictionary of the Mon inscriptions, from the sixth to the sixteenth centuries, incorporating materials collected by the late C. O. Blagden. London: Oxford University Press.

——2006. A Mon-Khmer comparative dictionary. [edited by: Paul Sidwell, Doug Cooper and Christian Bauer] Canberra: Pacific Linguistics.

Sidwell, Paul. 2000. Proto South Bahnaric: a reconstruction of a Mon-Khmer language of Indo-China. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics.

——2009. Classifying the Austroasiatic languages: history and state of the art. Munich: Lincom Europa.

——2010. The Austroasiatic central riverine hypothesis. Journal of Language Relationship. 4: 117–134.

——2011. Comparative Mon-Khmer linguistics in the 20th century: where from, where to? In K. S. Nagaraja (ed.) Austro-Asiatic linguistics: in memory of R. Elangaiyan. Mysore: Central Institute of Indian Languages, 38–104.

Sidwell, Paul and Roger Blench. 2011. The Austroasiatic Urheimat: the Southeastern Riverine Hypothesis. In N. J. Enfield (ed.) Dynamics of human diversity. Canberra, Pacific Linguistics. pp. 315–344.

Sidwell, Paul and Pascale Jacq. 2003. A handbook of comparative Bahnaric. Volume 1: West Bahnaric. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics.

Smith, Kenneth D. 1979. Sedang grammar. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics.

Solntseva, V. Nina. 1996. Case-marked pronouns in the Taoih language. The Mon-Khmer Studies Journal 26: 33–36.

Svantesson, Jan-Olof. 1988. U. Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman area 11(1): 64–133.

——1989. Tonogenic mechanisms in Northern Mon-Khmer. Phonetics 46: 60–79.

——1991. Hu – a language with unorthodox tonogenesis. In Jeremy H.C.S. Davidson (ed.) Austroasiatic languages. Essays in honour of H. L. Shorto. London: SOAS University of London, 67–80.

Thongkum, Theraphan L. 1979. The distribution of the sounds of Bruu. The Mon-Khmer Studies Journal 8: 221–293.

Thongkum, Theraphan L. and See Puengpa. 1980. A Bruu-Thai-English dictionary. Bangkok: Chulalongkorn University Printing House.

Thurgood, Graham. 2002. Vietnamese and tonogenesis: revising the model and the analysis. Diachronica 19(2): 333–363.

——2007. Tonogenesis revisted: revising the model and the analysis. [An updating of my Diachronica tonogenesis paper]. In Jimmy G. Harris, Somsonge Burusphat and James E. Harris (eds) Studies in Tai and Southeast Asian Linguistics. Bangkok: Ek Phim Thai Co., 263–291.

van Driem, George. 2001. Languages of the Himalayas, Volume 1. Leiden: Brill.

Vương, Hoàng Tuyên. 1963. Các dân tộc nguồn gốc Nam Á ở Tây Bắc Việt Nam. Nxb Giáo dục, Hà Nội.

Vương, Hừu Lễ. 1999. A new interpretation of the Bru Vân Kiêu vowel system. The Mon-Khmer Studies Journal 29: 97–106.

Watson, Richard. 2011. A case for clitics in Pacoh. In Sophana Srichampa, Paul Sidwell and Kenneth Gregerson (eds) Austroasiatic Studies: papers from the ICAAL4. Mon-Khmer Studies Journal Special Issue No. 3. Dallas, SIL International; Canberra, Pacific Linguistics; Salaya, Mahidol University, 222–232.

Wayland, Ratree and Allard Jongman. 2001. Chanthaburi Khmer vowels: phonetic and phonemic analyses. The Mon-Khmer Studies Journal 31: 65–82.