Milano

BETWEEN LA SCALA AND SFORZA CASTLE

NEAR BASILICA DI SANT’AMBROGIO

NEAR MILANO CENTRALE TRAIN STATION

Map: Milan Hotels & Restaurants

NAVIGLIO GRANDE (CANAL DISTRICT)

Map: Train Connections from Milan

For every church in Rome, there’s a bank in Milan. Italy’s second city and the capital of the Lombardy region, Milan is a hardworking, style-conscious, time-is-money city of 1.3 million. A melting pot of people and history, Milan’s industriousness may come from the Teutonic blood of its original inhabitants, the Lombards, or from its years under Austrian rule. Either way, Milan is modern Italy’s center of fashion, industry, banking, TV, publishing, and conventions. It’s also a major university town, a train hub, and host to two football (soccer) teams and the nearby Monza Formula One racetrack. And as home to a prestigious opera house, Milan is one of the touchstones of the world of opera.

Artistically, Milan can’t compare with Rome and Florence, but the city does have several unique and noteworthy sights: the Duomo and the Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II arcade, La Scala Opera House, Michelangelo’s last pietà sculpture (in Sforza Castle), and Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper.

Founded by the Romans as Mediolanum (“the place in the middle”), by the fourth century AD it was the capital of the western half of the Roman Empire, the namesake of Constantine’s “Edict of Milan” legalizing Christianity, and home of the powerful early Christian bishop, St. Ambrose.

After some barbarian darkness, medieval Milan became a successful mercantile city, eventually rising to regional prominence under the Visconti and Sforza families. The mammoth cathedral, or Duomo, is a testament to the city’s wealth and ambition. By the time of the Renaissance, Milan was nicknamed “the New Athens,” and was enough of a cultural center for Leonardo da Vinci to call it home. Then came 400 years of foreign domination (under Spain, Austria, France, more Austria). Milan was a focal point of the 1848 revolution against Austria and helped lead Italy to unification in 1870. The impressive Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II and La Scala Opera House reflect the sophistication of turn-of-the-20th-century Milan as one of Europe’s cultural powerhouses.

Mussolini left a heavy fascist touch on the architecture here (such as the central train station). His excesses also led to the WWII bombing of Milan. But the city rose again. The 1959 Pirelli Tower (the skinny skyscraper in front of the station), while a trendsetter in its day, now seems quaint considering Milan’s glassy new high-rise developments. Today, Milan is people-friendly, with a great transit system and inviting pedestrian zones.

Many tourists come to Italy for the past. But Milan is today’s Italy. In this city of refined tastes, window displays are gorgeous, cigarettes are chic, and even the cheese comes gift-wrapped. Yet, thankfully, Milan is no more expensive for tourists than any other Italian city.

For pleasant excursions nearby, consider visiting Lake Como or Lake Maggiore—both are about an hour from Milan by train (see the previous chapter).

Milan isn’t as charming as Venice or Florence, but it’s still a vibrant and vital piece of the Italian puzzle.

With two nights and a full day, you can gain an appreciation for the city and see most major sights. On a short visit, I’d focus on the center. Tour the Duomo, hit any art you like (reserve ahead to see The Last Supper), browse elegant shops and the Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II, and try to see an opera. To maximize your time in Milan, use the Metro to get around.

For those with a round-trip flight into Milan: I’d recommend starting your journey softly by going first to Lake Como (one-hour ride to Varenna). Then, with jet lag under control, dive into Milan.

Monday is a terrible sightseeing day, since many museums are closed (including The Last Supper). August is oppressively hot and muggy, and locals who can vacate do, leaving the city quiet. Those visiting in August find that the nightlife is sleepy, and many shops and restaurants are closed.

A Three-Hour Tour: If you’re just changing trains at Milan’s Centrale station (as, sooner or later, you probably will), consider catching a later train and taking this blitz tour: Check your bag at the station, ride the subway to the Duomo, peruse the square, explore the cathedral’s rooftop terraces and interior, drop into the Duomo Museum, have a scenic coffee in the Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II, spin on the floor mosaic of the bull for good luck, maybe see a museum (most are within a 10-minute walk of the main square), and return by subway to the station. A practical way to make the most of this quick visit is to use my free  Duomo neighborhood audio tour—see here.

Duomo neighborhood audio tour—see here.

My coverage focuses on the old center. Most sights and hotels listed are within a 15-minute walk of the cathedral (Duomo), which is a straight eight-minute Metro ride from the Centrale train station.

Milan’s TI, at the La Scala end of the Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II, isn’t worth a special trip (Mon-Fri 9:00-19:00, Sat-Sun until 18:00, Metro: Duomo, tel. 02-884-55555, www.turismo.milano.it).

For arrival by plane, see “Milan Connections” at the end of this chapter.

Visitors disembark at one of three major train stations: Milano Centrale, Porta Garibaldi, or Cadorna. Centrale handles most Trenitalia and Italo trains as well as airport buses. Porta Garibaldi receives trains from France and some Trenitalia trains from elsewhere in Italy. Both Centrale and Cadorna are terminals for trains from Malpensa Airport.

This huge, sternly decorated, fascist-built (in 1931) train station is a sight in itself. Notice how the monumental halls and art make you feel small—emphasizing that a powerful state is a good thing. In the front lobby, heroic people celebrate “modern” transportation (circa-1930 ships, trains, and cars) opposite reliefs depicting old-fashioned sailboats and horse carts.

Moving walkways link the station’s three main levels: platforms and eateries on top, shops and more food on a small mezzanine, and most services at ground level (including pay WCs and ATMs). For baggage check (deposito bagagli), taxis, or buses to Linate Airport, head toward the ground-level exit marked Piazza Luigi di Savoia. For buses to Malpensa Airport, head to the exit marked Piazza IV Novembre. Outside the station’s front entrance, under the atrium, are car-rental offices for Avis, Budget, and Maggiore, and a post office-run ATM. You’ll also find escalators down to the Metro and a fourth basement level with a few shops, including a Sapori & Dintorni supermarket.

To buy train tickets, follow blue signs to Biglietti and use the Trenitalia or Italo machines for most domestic trips. For international tickets or complicated questions, join the line at the Trenitalia ticket office on the ground floor. There’s also an Italo office on the ground floor.

Getting to the Center: “Centrale” is a misnomer—the Duomo is a 35-minute walk away. But it’s a straight shot on the Metro (8 minutes). Buy a ticket at a kiosk or from the machines, follow signs for yellow line 3 (direction: San Donato), and go four stops to the Duomo stop. You’ll surface facing the cathedral.

Taxis to the center are a good value for two or more people or if you don’t want to lug bags on the Metro (€12-15, departing taxis are to the left of the train station).

You’re most likely to use this commuter station if you take the Malpensa Express airport train, which uses track 1. The Cadorna Metro station—with a direct connection to the Duomo on Metro red line 1—is directly out front.

Some Trenitalia trains and the high-speed TGV from Paris use Porta Garibaldi station, north of the city center. Porta Garibaldi is on Metro green line 2, two stops from Milano Centrale, and purple line 5.

Leonardo never drove in Milan. Smart guy. Driving here is bad enough to make the €30/day fee for a downtown garage a blessing. And there’s a €5 congestion fee if you drive in the city center on weekdays. Do Milan (and Lake Como) before or after you rent your car, not while you’ve got it, and use the park-and-ride lots at suburban Metro stations such as Cascina Gobba. These are shown on the official Metro map, and full details are at www.atm.it (select English, then “Car Parks,” then “Parking Lots”).

Theft Alert: Be on guard. Milan’s thieves target tourists, especially at the Centrale train station, getting in and out of the subway, and around the Duomo. They can be dressed as tourists, businessmen, or beggars, or they can be gangs of too-young-to-arrest children. Watch out for ragged people carrying newspapers and cardboard—they’ll thrust these at you as a distraction while they pick your pocket. If you’re ripped off and plan to file an insurance claim, fill out a report with the police (main police station, “Questura,” Via Fatebenefratelli 11, Metro: Turati, open daily 24 hours, tel. 02-62261).

Medical Help: Here are two medical clinics with emergency care facilities (both closed Sat-Sun): the International Health Center in Galleria Strasburgo (also does dentistry, between Via Durini and Corso Europa, at #3, third floor, Metro: San Babila, tel. 02-7634-0720, www.ihc.it), and the American International Medical Center at Via Mercalli 11 (Metro: Missori or Crocetta, call for appointment, tel. 02-5831-9808, www.aimclinic.it).

Bookstores: The handiest major bookstore is La Feltrinelli, under the Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II (daily, tel. 02-8699-6903). The American Bookstore is at Via Manfredo Camperio 16, near Sforza Castle (closed Sun, Metro: Cairoli, tel. 02-878-920).

Events and Entertainment: HelloMilano.it, WantedinMilan.com, and Turismo.milano.it are decent websites for info on what’s happening in the city.

Soccer: For a dose of Europe’s soccer mania (which many believe provides a necessary testosterone vent to keep Europe out of a third big war), catch a match while you’re here. A.C. Milan and Inter Milan are the ferociously competitive home teams. Both teams play in the 85,000-seat Meazza Stadium (a.k.a. San Siro) most Sunday afternoons from September to June (ride Metro purple line 5 to San Siro Stadio, bring passport for security checks, www.acmilan.com or www.inter.it).

By Public Transit: It’s a pleasure to use Milan’s great public transit system, called ATM (“ATM Point” info desk in Duomo Metro station, www.atm.it). The clean, spacious, fast, and easy Metro zips you nearly anywhere you may want to go, and trams and city buses fill in the gaps. The handiest Metro line for a quick visit is the yellow line 3, which connects Centrale station to the Duomo. The other lines are red (1), green (2), and purple (5). The Metro shuts down at about midnight, but many trams continue until 1:00 or 2:00. With 100 miles of track, Milan’s classic, century-old yellow trams are both efficient and atmospheric.

A single ticket, valid for 90 minutes, can be used for one ride, including transfers, on Metro, bus, or tram (€2; sold at newsstands, tobacco shops, shops with ATM sticker in window, at machines in subway stations, and at many hotel reception desks). Other ticket options include a 24-hour pass (€7) and a 3-day pass (€12). Tickets must be run through the machines at Metro turnstiles when you enter and again when you leave the station. On buses and trams, the machines are at the front and rear and you need only validate upon entry. You also need to validate if transferring.

By Taxi: Small groups go cheap and fast by taxi (drop charge—€3.30, €1.10/kilometer; €5.40 drop charge on Sun and holidays, €6.50 from 21:00 to 6:00 in the morning). It can be easier to walk to a taxi stand than to flag down a cab. Handy stands are at Piazza del Duomo and in front of Sforza Castle. Hotels and restaurants are also happy to call one for you (tel. 02-8585 or 02-6969). The FreeNow app (www.free-now.com) lets you summon and pay for a taxi. Uber Black and UberLux also operate in Milan.

By Bike: Public BikeMi stations are generally near Metro stations. Download the BikeMi app to see available bikes and parking spots (subscription is €4.50/day, €9/week; first 30 minutes free, then €0.50/30 minutes up to 2 hours, after that €2/hour, www.bikemi.com).

To sightsee on your own, download my free Milan’s Duomo Neighborhood audio tour.

To sightsee on your own, download my free Milan’s Duomo Neighborhood audio tour.

Lorenza Scorti is a hardworking young guide who knows her city’s history and how to teach it. She also enjoys leading Lake Como day trips (€160/3 hours, same price for individuals or groups, evenings OK, mobile 347-735-1346, lorenza.scorti@libero.it). Sara Cerri is another good licensed local guide who enjoys passing on her knowledge (€195/3 hours, then €50/hour, mobile 380-433-3019, www.walkingtourmilan.it, walkingtourmilan@gmail.com). Valeria Andreoli, smart and fun-loving, leads a variety of themed tours (highlights tour—€60/hour, €180/half-day, mobile 338-301-2220, www.bellamilanotours.com, valeria@bellamilanotours.com).

If you can’t get a reservation for The Last Supper, consider joining a walking or bus tour that includes a guided visit to Leonardo’s masterpiece. These €65-80 tours (usually 3 hours) also take you to top sights such as the Duomo, Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II, La Scala Opera House, and Sforza Castle. Ideally book at least a week in advance, but it’s worth a try at the last minute, too.

For the best experience, I’d book a walking tour with Veditalia (www.veditalia.com) or City Wonders (www.citywonders.com). Both have good guides and solid reputations. Get Your Guide (www.getyourguide.com) is another worthwhile option. The bus-and-walking tours are less satisfying, but you can try Autostradale (“Look Mi” tour, offices in passage at far end of Piazza del Duomo and in front of Sforza Castle, tel. 02-8058-1354, www.autostradaleviaggi.it) or Zani Viaggi (office disguised as a “tourist information” point, corner of Foro Buonaparte and Via Cusani at #18, near Sforza Castle, tel. 02-867-131, www.zaniviaggi.com).

Hop-On, Hop-Off Option: Zani Viaggi also operates CitySightseeing Milano hop-on, hop-off buses (look for the red buses—easiest at Duomo and La Scala, €22/all day, €25/48 hours, buy on board, recorded commentary, www.milano.city-sightseeing.it). With the 48-hour bus ticket, you can pay an additional €44 for a Last Supper reservation—exorbitant but worth considering for the wealthy and the desperate (April-Oct only).

▲▲Duomo Museum (Museo del Duomo)

▲▲Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II

▲La Scala Opera House and Museum

Performances in the Opera House

Piazza degli Affari and a Towering Middle Finger

▲Church of San Maurizio (San Maurizio al Monastero Maggiore)

▲Leonardo da Vinci National Science and Technology Museum (Museo Nazionale della Scienza e Tecnica “Leonardo da Vinci”)

▲▲Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper (L’Ultima Cena/Cenacolo Vinciano)

▲▲Brera Art Gallery (Pinacoteca di Brera)

▲▲Sforza Castle (Castello Sforzesco)

Sempione Park (Parco Sempione)

▲Naviglio Grande (Canal District)

▲Monumental Cemetery (Il Cimitero Monumentale)

Milan’s core sights—the Duomo, Duomo Museum, and Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II—cluster within easy walking distance. Also in the Duomo area are the Piazza della Scala and La Scala Opera House.

The city’s other main sights—The Last Supper, Basilica di Sant’Ambrogio, Sforza Castle, and Brera Art Gallery—are scattered farther afield. It’s easiest to reach them by public transportation.

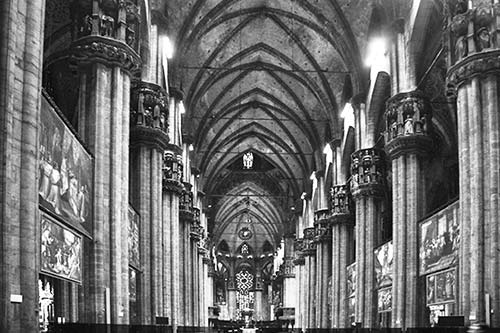

The city’s centerpiece is the third-largest church in Europe (after St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome and Sevilla’s cathedral). At 525 by 300 feet, the place is immense, with more than 2,000 statues inside (and another thousand outside) and 52 100-foot-tall, sequoia-size pillars representing the weeks of the year and the liturgical calendar. If you do two laps, you’ve done your daily walk. The church was built to hold 40,000 worshippers—the entire population of Milan when construction began.

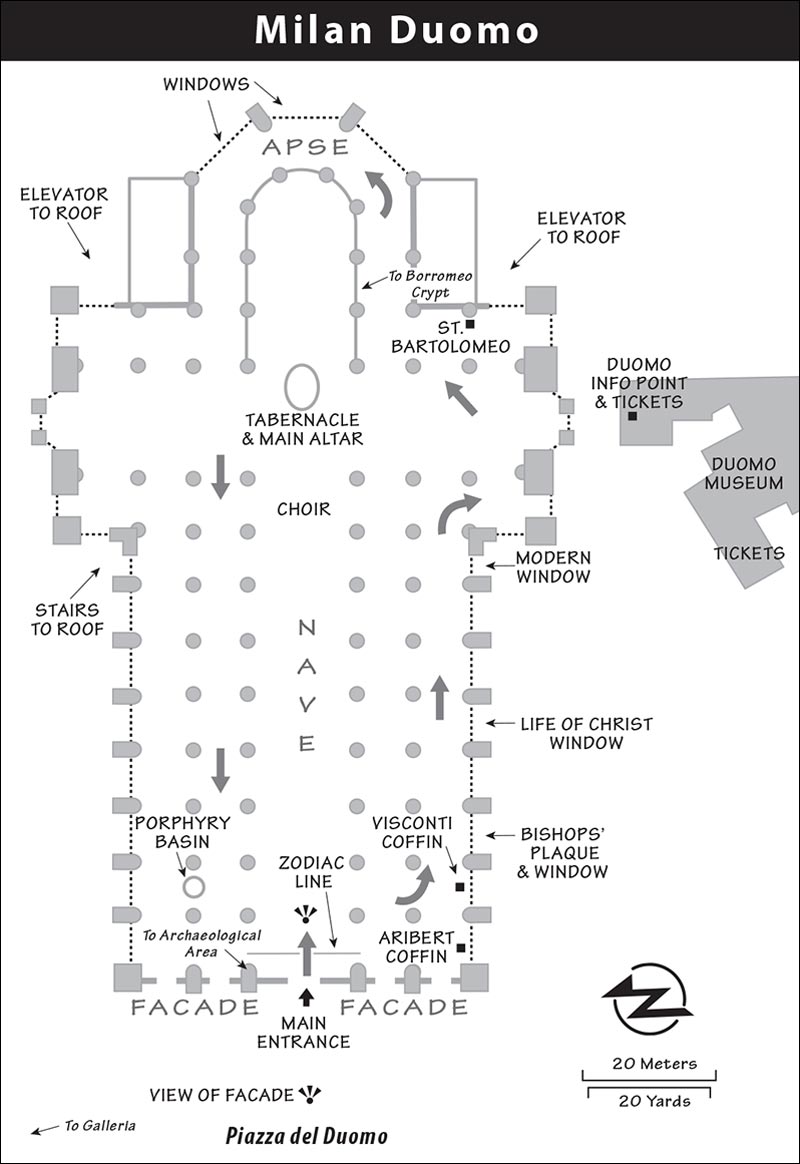

A visit here has several elements. First, take in the overwhelming exterior from various angles, admiring its remarkable bulk and many spires and statues. Then go inside to see the church’s vast nave, stained glass, historic tombs, basement archaeological area, and a quirky, one-of-a-kind statue of a flayed man. A visit to the adjacent Duomo Museum lets you see the church’s statues and details up close. Finally, take an elevator ride (or long stair climb) up to the Duomo rooftop for city views and a stroll through a forest of jagged church spires.

Cost: Cathedral-€3, museum-€3, rooftops by elevator-€14. The archaeological area is free with any ticket. Of the various combo-tickets, the best is the €17 Duomo Pass Lift, which includes the cathedral, rooftop terraces by elevator, archaeological area, and Duomo Museum.

Hours: Cathedral open daily 8:00-19:00, archaeological area and rooftop from 9:00; Duomo Museum Thu-Tue 10:00-18:00, closed Wed; last entry one hour before closing.

Information: Church tel. 02-7202-3375, museum tel. 02-3616-9351, www.duomomilano.it.

Buying Tickets and Avoiding Lines: There are two ticket booths (each with ticket machines): the big ticket center with info office (on the south side of the cathedral across from the Duomo’s right transept at #14a) and at the Duomo Museum.

You can avoid the occasionally very long ticket lines by buying timed-entry tickets online (€0.50/ticket surcharge); if buying on-site, the museum often has shorter lines. Security lines can also be long. You can avoid the church security line by doing the rooftop first and descending from there directly into the church. Or visit late in the day, when there are generally fewer people.

Dress Code: Modest dress is required to visit the church. Keep shoulders and knees covered, and don’t wear sports T-shirts or shorts.

Tours: A €6 audioguide for the church is available at a kiosk inside its main door (no rentals Sun).

Self-Guided Tour

Self-Guided TourStand facing the main facade. The Duomo is huge and angular, with prickly spires topped with statues. The style, Flamboyant Gothic, means “flame-like,” and the church seems to flicker toward heaven with flames of stone. The facade is a pentagon, divided by six vertical buttresses, all done in pink-white marble. The dozens of statues, pinnacles, and pointed-arch windows on the facade are just a fraction of the many adornments on this architecturally rich structure.

For more than 2,000 years, this spot has been the spiritual heart of Milan: In 2014, archaeologists probing for ancient Roman ruins beneath the Duomo discovered the remains of what might be a temple to the goddess Minerva. A church has stood on this site since the days of the ancient Romans and St. Ambrose (4th century), but construction of the building we see today began in 1386. Back then, the dukes of Milan wanted to impress their counterparts in Germany, France, and the Vatican with this massive cathedral. They chose the trendy Gothic style coming out of France, and stuck with it even after Renaissance-style domes came into vogue elsewhere in Italy. The cathedral was built not from ordinary stone, but from expensive marble, top to bottom. Pink Candoglia marble was rafted in from a quarry about 60 miles away, across Lake Maggiore and down a canal to a port at the cathedral—a journey that took about a week. Construction continued from 1386 to 1810, with final touches added as late as 1965.

The statues on the lower level of the facade—full of energy and movement—are early Baroque, from about 1600. Of the five bronze doors, the center one is biggest. Made in 1907 in the Liberty Style (Italian Art Nouveau), it features the Joy and Sorrow of the Virgin Mary. Sad scenes are on the left, joyful ones on the right, and on top is the coronation of Mary in heaven by Jesus, with all the saints and angels looking on. (High above that is what looks like the Statue of Liberty, dating from the 1820s—decades before Frédéric-Auguste Bartholdi designed the one Americans know and love. Hmmm.)

Topping the church (you may have to back up to see it) is its tallest spire. It rises up from the center of the Duomo to display a large golden statue of the Madonna of the Nativity, to whom the church is dedicated.

A Closer Look: Along the right side of the church are interesting views from every angle: the horizontal line of the long building, the verticals of the spires, and the diagonals of the flying buttresses supporting the roof. Get close to the facade’s right corner to appreciate the many intricate details: a nude Atlas holding up the corner buttress, robed saints, relief panels of Bible scenes, and tiny faces—angry, smiling, happy, sad.

Stroll a little farther down the right to see the range of statues, from placid saints to thrashing nudes. These statues were made between the 14th and 20th centuries by sculptors from all over Europe. There are hundreds of them—each different. Midway up are the fanciful gargoyles (96 in total) that functioned as drain spouts. Look way up to see the statues on the tips of the spires...they seem so relaxed, like they’re just hanging out, waiting for their big day.

The back end of the church (if you make it that far) is the oldest part, with the earliest stones, laid in the late 1300s. The sun-in-rose window was the proud symbol of the city’s leading Visconti family. It’s flanked by the angel telling Mary she’s going to bear the Messiah. Nearby, find the shrine to the leading religion of the 21st century: soccer. The Football Team store is filled with colorful vestments and relics of local soccer saints.

Nave: It’s the fourth-longest nave in Christendom, stretching more than 500 feet from the entrance to the stained-glass rose window at the far end. The apse at the far end was started in 1385. The wall behind you wasn’t finished until 1520. The style is Gothic, a rarity in Italy. Fifty-two tree-sized pillars rise to support a ribbed, pointed-arch ceiling, and the church is lit by glorious stained glass. At the far end, marking the altar, is a small tabernacle of a dome atop columns—a bit of an anomaly in a Gothic church (more on that later). Notice the little red light on the cross high above the altar. This marks where a nail from the cross of Jesus is kept. This relic was brought to Milan by St. Helen (Emperor Constantine’s mother) in the fourth century, when Milan was the capital of the western Roman Empire. It’s on display for three days a year (in mid-Sept).

Notice the two single-stone pillars flanking the main door—each is made from a single stone. Now, facing the altar, look high to the right, in the rear corner of the church, and find a tiny pinhole of white light. This is designed to shine a 10-inch sunbeam at noon onto the bronze line that runs across the floor, indicating where we are on the zodiac calendar.

This 600-year-old church is filled with history. It represents the continuous line of bishops who have presided over Milan, stretching back to the days of St. Ambrose (c. 340-397). Let’s see some of the earliest artifacts.

• Before wandering deeper into the church, head to the end of the...

Right Aisle: The first recess along the right wall has the 1,000-year-old gray-stone coffin of Archbishop Aribert, a formidable figure in 11th-century Milan. A couple of steps farther along, you’ll see a red coffin atop columns belonging to the noble Visconti family who commissioned this church.

The third bay has a plaque where you can trace the uninterrupted rule of 144 local archbishops back to AD 51. Check out the stained-glass window above the plaque. Find familiar scenes along the window’s bottom level: Cain killing Abel, the Flood, and the drunkenness of Noah. The brilliant and expensive colored glass (stained, not painted) is from the 15th century. Bought by wealthy families seeking the Church’s favor, the windows face south to get the most light. The windows’ purpose was to teach the illiterate masses the way to salvation through stories from the Old Testament and the life of Jesus. Many of the windows are more modern—from the 16th to the 20th century—and are generally made of dimmer, cheaper painted glass. Many are replacements for ones destroyed by the concussion of WWII bombs that fell nearby.

The fifth window dates from 1470, “just” 85 years after the first stone of the cathedral was laid. The window shows the story of Jesus, from Annunciation to Crucifixion. In the bottom window, as the angel Gabriel tells Mary the news, the Holy Spirit (in the form of a dove) enters Mary’s window and world.

The seventh window is from the 1980s. Bright and bold, it celebrates two local cardinals (whose tombs and bodies are behind glass). The memorials to Cardinal Ferrari (below the window) and Cardinal Schuster (in the next bay), who heroically helped the Milanese out of their post-WWII blues, are a reminder that this great church is more than a tourist attraction—it’s a living part of Milan.

• Now take a few steps back into the nave for a view of the...

Main Altar: The altar area is anchored by the domed tabernacle atop columns. This houses the receptacle that holds the Eucharist. Flanking the tabernacle are two silver statues of famous bishops. On the left is St. Ambrose, the influential fourth-century bishop who put Milan on the map and became the city’s patron saint. The other is St. Charles Borromeo, the bishop who transformed the Duomo in the 16th century. Charles had inherited a cathedral that was barely half-finished. He re-energized the project, and commissioned the tabernacle. Above are four 16th-century pipe organs.

While the rest of the church is Gothic, the altar is Baroque—a dramatic stage-like setting in the style of the Vatican in the 1570s. Borromeo was a great champion of the Catholic church, and this powerful style was a statement to counter the Protestant Reformation that was threatening the Roman Catholic Church. Look up into the dome above the altar—a round dome on an octangular base, rising 215 feet. Napoleon crowned himself king of Italy under this dome in 1805. It was Napoleon who sped up construction, so that in 1810—finally—the church was essentially completed.

• Before moving on, look to the rear, up at the ceiling, and see the fancy “carved” tracery on the ceiling’s ribs. Nope, that’s painted. It looks expensive, but paint is more affordable than carved stone. Now continue up the right aisle and into the south (right) transept. Find the bald statue.

St. Bartolomeo Statue: This is a grotesque 16th-century statue of St. Bartolomeo, an apostle and first-century martyr skinned alive by the Romans. Examine the details (face, hands, feet) of the poor guy. He piously holds a Bible in one hand and wears his own skin like a robe. Carved by a student of Leonardo da Vinci, this is a study in human anatomy learned by dissection, forbidden by the Church at the time. Read the sculptor’s proud Latin inscription on the base: “I was not made by Praxiteles”—the classical master of beautiful nudes—“but by Marco d’Agrate.”

• Walk toward the altar, checking out the fine 16th-century inlaid-marble floor. The black marble (quarried from Lake Como) is harder and more durable, while the lighter colors (white from Lake Maggiore, pink from Verona) look and feel more worn. At the altar, bear right around the corner 15 steps. You’ll see a door marked Scurolo di S. Carlo. This leads down to the...

Crypt of St. Charles Borromeo: Steps lead under the altar to the tomb of St. Charles Borromeo (1538-1584), the economic power behind the church. You can still see Charles’ withered body inside the rock-crystal coffin. Charles was bishop of Milan, and the second most important hometown saint after St. Ambrose. Tarnished silver reliefs around the ceiling show scenes from Charles’ life.

• Now resurface and continue around the apse, looking up at the...

Windows: The apse is lit by three huge windows, all 19th-century painted copies. The originals, destroyed in Napoleonic times, were made of precious stained glass. Each window has 12 panels and 12 rows, creating 144 separate scenes.

• From the apse, head back through the church toward the main entrance. Near the entrance stands a large basin of expensive purple porphyry. Made by Borromeo’s favorite architect, Pellegrini, it was used to baptize infants. Now find the entrance and stairs that lead down to the...

Archaeological Area: The church’s “basement” is a maze of ruined brick foundations of earlier churches that stood here long before the present one. Milan has been an important center of Christianity since its beginning. In Roman times, Mediolanum’s streets were 10 feet below today’s level. The stones and mosaics you see, the pavement you walk on, and the artifacts in the glass case date from the time of the Edict of Milan (AD 313) when Emperor Constantine, ruling from this city, made Christianity legal in the Roman Empire.

The highlight here is the scant remains of the eight-sided Paleo-Christian Baptistery of San Giovanni. It stands alongside the remains of a little church. Back then, since you couldn’t enter the church until you were baptized (which didn’t happen until age 18), churches had a little baptistery just outside for the unbaptized.

This humble baptistery was where St. Ambrose was baptized. Ambrose went on to become bishop here, and to mentor a randy and rebellious Roman named Augustine. On this spot in AD 387, Ambrose baptized the 31-year-old Augustine of Hippo, who later became one of Christianity’s (and the world’s) most influential thinkers, philosophers, and writers. And the rest—like this tour—is history.

For information on tickets and opening times for these sights, see the cost and hours for the Duomo, earlier.

This museum, to the right of the Duomo in the Palazzo Reale, helps fill in the rest of the story of Milan’s cathedral, and lets you see its original art and treasures up close. The collection is much more meaningful with the audioguide (€6, with standard earbud jack).

Visiting the Museum: Just after the ticket taker, notice (on the wall to your right) the original inlaid-marble floor of the Duomo. The black (from Lake Como) marble is harder. Go ahead, wear down the white a little more.

Now follow the roughly chronological one-way route. Among the early treasures of the cathedral is a 900-year-old, Byzantine-style crucifix. Made of copper gilded with real gold and nailed onto wood, it was part of the tomb of the archbishop of Milan. A copy is in today’s cathedral.

You’ll pass a big, wooden model of the church (we’ll get a better look at this later, on the way out). Then you’ll step through a long room with paintings, chalices, glass monstrances, and lifelike reliquary busts of Sts. Charles, Sebastian, and Thecla.

Look for the big, 600-year-old statue of St. George. Among the cathedral’s oldest statues, it once stood on the front (and first constructed) spire of the Duomo. Some think this is the face of Duke Visconti—the man who started the cathedral. The museum is filled with statues and spires like this, carved of marmo di Candoglia—marble from Candoglia. The duke’s family gave the entire Candoglia quarry (near Stresa) to the church for all the marble it would ever need.

You’ll pop into a long room filled with more statues. On your left, gaze into the eyes of the big gilded bust of God the Father. Made of wood, wrapped in copper, and gilded, this giant head covered the keystone connecting the tallest arches directly above the high altar of the Duomo.

Continue into a narrow room lined with grotesque gargoyles. When attached to the cathedral, they served two purposes: to scare away evil spirits and to spew rainwater away from the building.

Twist through several more rooms of 14th- and 15th-century statues big and small that embellished the church’s many spires. In one long, brick-walled hall, watch on the left for St. Paul the Hermit, who got close to God by living in the desert. While wearing only a simple robe, he’s filled with inner richness. The intent is for pilgrims to commune with him and feel at peace (but I couldn’t stop thinking of the Cowardly Lion—“Put ’em up! Put ’em up!”).

A few steps beyond Paul, look for the 15th-century dandy with the rolled-up contract in his hand. That’s Visconti’s descendant, Galeazzo Sforza, and if it weren’t for him, the church facade might still be brick as bare as the walls of this room. The contract he holds makes it official—the church now owns the marble quarry (and it makes money on it to this day).

In the next room, study the brilliantly gilded and dynamic statue God the Father (1554). Five steps farther is a sumptuous Flanders-style tapestry, woven of silk, silver, and gold in 1468. Half a millennium ago, this hung from the high altar. In true Flemish style, it weaves vivid details of everyday life into the theology. It tells the story of the Crucifixion by showing three scenes at once. Note the exquisite detail, down to the tears on Mary’s cheeks.

Next you’ll step through a stunning room with 360 degrees of gorgeous stained glass from the 12th to 15th century, telling the easily recognizable stories of the Creation, the Tower of Babel, and David and Goliath. Take a close look at details that used to be too far above the cathedral floor to be seen clearly—again, designed for God’s eyes only.

Farther on, you’ll reach a display of terra-cotta panels juxtaposed with large monochrome paintings (1628) by Giovanni Battista Crespi. After Crespi finished the paintings, they were translated into terra-cotta, and finally sculpted in marble to decorate the doorways of the cathedral. Study Crespi’s Creation of Eve (Creazione di Eva) and its terra-cotta twin. This served as the model for the marble statue that still stands above the center door on the church’s west portal (1643). You’ll pass a few more of these scenes, then hook into a room with the original, stone-carved, swirling Dancing Angels, which decorated the ceiling over the door.

• When you reach the doors leading into the museum shop, make a U-turn to see the final exhibits.

After passing several big tapestries, and a huge warehouse where statues are stacked on shelves stretching up to the ceiling, you’ll reach the Frame of the Madonnina (1773). Standing like a Picasso is the original iron frame for the statue of the Virgin Mary that still crowns the cathedral’s tallest spire. In 1967, a steel replacement was made for the 33 pieces of gilded copper bolted to the frame. The carved-wood face of Mary (in the corner) is the original mold for Mary’s cathedral-crowning copper face.

Soon you’ll get a better look at that wooden model of the Duomo. This is the actual model used in the 16th century by the architects and engineers to build the church. This version of the facade wasn’t built, and other rejected facades line the walls.

On your way out, you’ll pass models for the Duomo’s doors. And stepping outside, as your eyes adjust to the sunlight, you’ll see the grand church itself—looking so glorious thanks to the many centuries of hard work you’ve just learned about.

Strolling between the frilly spires of the cathedral rooftop terraces is the most memorable part of a Duomo visit. You can climb the stairs or take the elevators. On the left side, the stairs are in front of the transept, and the elevator is behind it. (Even those taking the elevator will have to climb a lot of stairs.) On the right side, look for the “fast-track” elevator behind the transept.

Once up there, you’ll loop around the rooftop, wandering through a fancy forest of spires with great views of the city, the square, and—on clear days—the crisp and jagged Alps to the north. And, 330 feet above everything, La Madonnina overlooks it all. This 15-foot-tall gilded Virgin Mary is a symbol of the city.

Visiting the Rooftop: As you emerge from the stairs or lift, you first walk along the lower side-terrace. You’ll enjoy close-ups of fanciful gargoyles, statue-topped spires, and ever-changing views of the rows of flying buttresses (which, on this lavishly ornamented Gothic church, are both decorative and functional).

Take a moment to appreciate the detail. Keep in mind that the stairs you climbed were designed not for the public but for workers. The exquisite figures carved in stone around you—every face and every glower all different—were unseen by the public for over 400 years. They were all carved as a gift to God.

Next you climb a richly carved staircase to the sloping rooftop—directly above the nave. As you wander among the spires, pick any one and appreciate its details. At the spires’ base is the marble “fence” that surrounds the entire rooftop, with its pointed arches topped with pinnacles, which themselves are mostly crowned with crosses. Each spire is supported by blocks of Candoglia marble, with its pink-white-green-blue hues (which blend into gray).

On the next level up, the spires have vertical ribs and saints in cages. Continuing up, they get more ornate, with flamboyant flames that flicker upward toward still more saints posing beneath church-like awnings. Finally, the spire tapers into a slender point, topped with a lifelike saint who gazes out over the city. The church has 135 spires—all similar, yet each different. No wonder it took 600 years to carve it all.

At the counter-facade (the back side of the church’s false-front facade), find a few 20th-century details that are among the last things done. To the left (as you face toward the Piazza del Duomo), find carved reliefs with boxing scenes. Just above and to the right of the boxing scenes is a relief of carved foliage. The proud-looking face peering out from the leaves is none other than the WWII dictator Benito Mussolini.

Before leaving, check out the great views of the city. To the east, you can peer down into the Piazza del Duomo, 20 stories below.

To the south of the Duomo is the red-brick, octagonal, statue-topped bell tower of San Gottardo Church, built in the 1300s by the same Visconti family that began the Duomo. The hard-to-miss Velasca Tower (Torre Velasca) is a top-heavy skyscraper from the 1950s (modeled on medieval watchtowers such as those at the Sforza Castle), which became a symbol of Milan’s rise from the ashes of World War II.

Looking north, there’s a skyline of a dozen-plus skyscrapers. At the far right of the group is the 32-story Pirelli Tower, a slender rectangle with tapering sides, which proclaimed Italy’s postwar “economic miracle.” The UniCredit Tower (from 2011), with its 750-foot-high rocket-like spire, is Italy’s tallest building, and represents Milan’s future. (This marks the Porta Nuova neighborhood, described later and worth a visit.)

Remember, as you leave you’ll find two descending staircases giving you two options: directly back to the street or into the church.

Stand in the center of Milan’s main square and take in the scene. Before you rises the massive, prickly facade of Milan’s cathedral, the Duomo. The huge equestrian statue in the center of the piazza is Victor Emmanuel II, the first king of Italy. He’s looking at the grand Galleria named for him. The words above the triumphal arch entrance read: “To Victor Emmanuel II, from the people of Milan.” This grand square is ground zero for public events, marches, and spectacles in Milan.

To the right of the Duomo are the twin fascist buildings of the Arengario Palace. Mussolini made grandiose speeches from the balcony on the left. Study the buildings’ relief panels, which tell—with fascist melodrama—the history of Milan. Today the palace houses the Museo del Novecento (described later).

Directly to the right of the Duomo is the historic ducal palace, the Palazzo Reale, which now houses the Duomo Museum (described earlier). The palace was redone in the Neoclassical style by Empress Maria Theresa in the late 1700s, when Milan was ruled by the Austrian Habsburgs.

Behind the Victor Emmanuel II statue (opposite the cathedral, about a block beyond the square), hiding in a small courtyard, is Piazza dei Mercanti, the center of medieval Milan (described later).

And all around you in Piazza del Duomo is a classic European scene and a local gathering point. Professionals scurry, fashion-forward kids loiter, and young thieves peruse.

This breathtaking four-story glass-domed arcade, next to Piazza del Duomo, is a symbol of Milan. The iron-and-glass shopping mall (built during the age of Eiffel and the heady days of Italian unification) showcased a new, modern era. It was the first building in town to have electric lighting, and since its inception it’s been an elegant and popular meeting place. (Sadly, its designer, Giuseppe Mengoni, died the day before the gallery opened.) Here, in this covered piazza, you can turn an expensive cup of coffee into a good value by enjoying some of Europe’s best people-watching.

The venerable Bar Camparino (at the Galleria’s Piazza del Duomo entry), with a friendly staff and a period interior surviving from the 1870s, is the former haunt of famous opera composer Giuseppe Verdi and conductor Arturo Toscanini, who used to stop by after their performances at La Scala. It’s a fine place to enjoy a drink and people-watch (€4 for an espresso is a great deal to take a seat, relax and enjoy the view, or pay €1.50 at the bar just to experience the scene). The café is named after the Campari family (its first owners), originators of the famous red Campari bitter. You can enjoy a Campari or a Campari spritz at this unforgettable perch for €13 (Tue-Sun 7:30-20:00, closed Mon and Aug, tel. 02-8646-4435).

Wander around the Galleria. Its art celebrates the establishment of Italy as an independent country. Around the central dome, patriotic mosaics symbolize the four major continents (sorry, Australia). The mosaic floor is also patriotic. The white cross in the center is part of the king’s coat of arms. The she-wolf with Romulus and Remus (on the south side—facing Rome) honors the city that, since 1870, has been the national capital. On the west side (facing Torino, the provisional capital of Italy from 1861 to 1865), you’ll find that city’s symbol: a torino (little bull). For good luck, locals step on his irresistible little testicles. Two local girls explained to me that it works better if you spin—two times, and it must be clockwise. Find the poor little bull and observe for a few minutes...it’s a cute scene. With so much spinning, the mosaic is replaced every few years.

Luxury shops have had outlets here from the beginning. Along with Gucci, Louis Vuitton, and Prada, you’ll find Borsalino (at the end near Piazza della Scala), which has been selling hats here since the gallery opened in 1877.

If you cut through the Galleria to the other side, you’ll pop out at Piazza della Scala, with its famous opera house and the Gallerie d’Italia—all described later. (While you may be tempted to walk the Highline Galleria, which hangs among the Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II rooftops, it’s not worth the time or money.)

Milan’s art of the 1900s (Novecento) fills the two buildings of the Arengario Palace, Mussolini’s fascist-era City Hall. In the beautifully laid-out museum, you’ll work your way up the escalators and through the last century, one decade at a time. Each section is well-described, and the capper is a fine panoramic view over Piazza del Duomo through grand fascist-era arches. The museum makes it clear that Milan—a trendy city today—has been setting design trends since the start of the Novecento.

Cost and Hours: €10; Tue-Sun 9:30-19:30 (Thu and Sat until 22:30), Mon from 14:30; last entry one hour before closing, audioguide—€5, facing Piazza del Duomo at Via Marconi 1, tel. 02-8844-4072, www.museodelnovecento.org.

Visiting the Museum: As you spiral up the ramp, pause at the large painting, The Fourth Estate, to gaze into the eyes of proud workers getting off their shift. Painted in 1901, the work was a bold manifesto of a new era, and is a good introduction to the revolutionary spirit of the museum.

On the second floor, minor works by Picasso, Matisse, Mondrian and others are a snapshot of “Modern Art” trends around Europe as the 1900s began. Next you see how they inspired Italy’s artists. Boccioni followed northern Europe’s lead, evolving from a placid painter of realistic portraits to a bold sculptor of swirling forms. He captured a world in high-tech motion—i.e., “Futurism.”

Escalate up to the third floor to see Giorgio de Chirico’s brooding canvases of long shadows and empty architecture—Italy’s great contribution to the movement called Surrealism.

The fourth floor focuses on the actual Novecento Italiano movement of the 1920s, which was based in Milan. These artists tried to merge Italy’s classic roots (of monumental ancient Roman art and geometrically solid Renaissance art) with abstract styles and the revivalist spirit of the Mussolini years.

Continuing up to the fifth floor, you emerge into a glass-walled space (often hosting temporary installations) with great views over Piazza del Duomo. Find the stairs up to the top room, with canvases by Lucio Fontana. In the 1950s and ‘60s, Fontana made his mark by slicing and puncturing canvases to transform a two-dimensional “painting” into a three-dimensional “sculpture.” Fontana also did the room’s textured ceiling and a large neon sculpture elsewhere on floor 5.

This small square, the center of political power in 13th-century Milan, hides one block off Piazza del Duomo (directly opposite the cathedral). A strangely peaceful place today, it offers a fine smattering of historic architecture that escaped the bombs of World War II.

The arcaded, red-brick building that dominates the center of the square was the City Hall (Palazzo della Ragione); its arcades once housed the market hall. Overlooking the wellhead in the middle of the square is a balcony with coats of arms—this is where new laws were announced. Eventually two big families—Visconti and Sforza—took power, Medici-style, in Milan; the snake is their symbol. Running the show in Renaissance times, these dynasties shaped much of the city we see today, including the Duomo and the fortress. In 1454, the Sforza family made peace with Venice while enjoying a friendship with the Medici in Florence (who taught them how to become successful bankers). This ushered in a time of stability and peace, when the region’s major city-states were run by banking families, and money was freed up for the Renaissance generation to make art, not war.

This square also held the Palace of Justice (the 16th-century courthouse with the clock tower), the market (not food, but crafts: leather, gold, and iron goods), the bank, the city’s first university, and its prison. All the elements of a great city were right here on the “Square of the Merchants.”

To reach these sights, cut through the Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II from Piazza del Duomo.

This smart little traffic-free square, between the Galleria and the opera house, is dominated by a statue of Leonardo da Vinci. The statue (from 1870) is a reminder that Leonardo spent his best 20 years in Milan, where he found well-paid, steady work. He was the brainy darling of the Sforza family (who dominated Milan as the Medici family dominated Florence). Under the great Renaissance genius stand four of his greatest “Leonardeschi.” (He apprenticed a sizable group of followers.) The reliefs show his various contributions as a painter, architect, and engineer. Leonardo, wearing his hydro-engineer hat, reengineered Milan’s canal system, complete with locks. (Until the 1920s, Milan was one of Italy’s major ports, with canals connecting the city to the Po River and Lake Maggiore. For more on this footnote of Milan’s history, read about the Naviglio Grande on here.)

The statue of Leonardo is looking at a plain but famous Neoclassical building, arguably the world’s most prestigious opera house (described next).

Milan’s famous Teatro alla Scala opened in 1778 with an opera by Antonio Salieri (Mozart’s wannabe rival). Today, opera buffs can get a glimpse of the theater and tour the adjacent museum’s extensive collection, featuring Verdi’s top hat, Rossini’s eyeglasses, Toscanini’s baton, Fettuccini’s pesto, original scores, diorama stage sets, busts, portraits, and death masks of great composers and musicians. For true devotees, La Scala is the Mecca of the religion of opera.

Cost and Hours: €9, daily 9:00-17:30, Piazza della Scala, tel. 02-8879-7473, www.teatroallascala.org.

Visiting the Museum: The main reason to visit the museum is the opportunity to peek into the theater (on many mornings you’ll see the orchestra practicing). The stage is as big as the seating area on the ground floor. (You can see the towering stage box from Piazza della Scala across the street.) A renovation corrected acoustical problems caused by WWII bombing and subsequent reconstruction. The royal box is just below your vantage point, in the center rear. Take in the ornate red-velvet seats, white-and-gold trim, the huge stage and orchestra pit, and the massive chandelier made of Bohemian crystal.

The museum itself is a handful of small rooms with low-tech displays. Room 1 has antique musical instruments—some are familiar-looking keyboards and guitars, some are strange and weirdly shaped. Room 2 takes you to the roots of opera in commedia dell’arte—those humorous plays of outsized characters and elaborate costumes, like clever harlequins and buffoonish doctors in masks. Room 3 features Liszt’s grand piano, still in playing condition.

Room 4’s paintings lead you through opera’s heyday in Milan. There’s a street scene of La Scala in 1852, with fancy carriages and well-dressed ladies and gents. Find portraits of great opera composers like portly Rossini, sideburned Donizetti, and thick-bearded Verdi (flanked by his three loves: two wives and a piano). In the glass case are miniature portraits of famous opera composers and singers, as well as Napoleon’s sword. Pass through Room 5 and into Room 6, with a glass case holding a snip of Mozart’s hair and a cast of Chopin’s slender hand. (The stairs lead up to temporary exhibits.)

Room 7 features many of opera’s all-stars. In the glass case is a snip of Verdi’s hair, scores by Verdi and Puccini, and batons of the great conductor (and music director of La Scala) Toscanini, who’s practically a saint in this town. The room’s portraits bring opera into the modern age. There’s the great composer Puccini whose accessible operas seem to unfold like realistic plays that just happen to be sung. The great early-20th-century tenor Enrico Caruso brought sophisticated Italian opera to barbaric lands like America. There are portraits of renowned sopranos (and world-class divas) Maria Callas and Renata Tebaldi.

The show goes on at the world-famous La Scala Opera House, which also hosts ballet and classical concerts. There are performances every month except August, and showtime is usually at 20:00 (for information, check online or call Scala Infotel Service, daily 9:00-18:00, tel. 02-7200-3744). On the opening night of an opera, a dress code is enforced for men (suit and tie).

Advance Booking: Seats sell out quickly. Online tickets go on sale two months before performances (www.teatroallascala.org).

Same-Day Tickets: On performance days, 140 sky-high, restricted-view, peanut-gallery tickets are offered at a low price (generally €15) at the box office (located down the left side of the theater toward the back on Via Filodrammatici, and marked with Biglietteria Serale sign). It’s a bit complicated: Show up at 13:00 with an official ID (driver’s license or passport) to put your name on a list (one ticket per person; for popular shows people start lining up long before, weekends tend to be busiest), then return at 17:30 for the roll call. You must be present when your name is called to receive a voucher, which you’ll then show at the window to purchase your ticket before the performance. Also, one hour before showtime, the box office sells any remaining tickets at a 25 percent discount.

This museum fills three adjacent buildings on Piazza della Scala with the amazing art collections of a bank that once occupied part of this space. The bank building’s architecture is early-20th-century Tiffany-like Historicism, with a hint of Art Nouveau; it’s connected to two impressive palazzos that boast the nicest Neoclassical interiors I’ve seen in Milan. They are filled with exquisite work by 19th- and 20th-century Italian painters.

Cost and Hours: €5, more during special exhibits, includes audioguide, free first Sun of the month; open Tue-Sun 9:30-19:30, Thu until 22:30, closed Mon, last entry one hour before closing; across from La Scala Opera House at Piazza della Scala 6, toll-free tel. 800-167-619, www.gallerieditalia.com.

Visiting the Museum: Enter through the bank building facing Piazza della Scala and take the red-velvet stairs to the basement to pick up an audioguide (also downstairs is a bag check, WCs, and the original bank vault, which now stores racks and racks of paintings not on display).

Back upstairs, head into the main atrium of the bank, and consider the special exhibits displayed there. Then, to tackle the permanent art collection in chronological order, head to the far end of the complex and work your way back (follow signs for Palazzo Anguissola Antona Traversi and Palazzo Brentani). You’ll go through the café back into the Neoclassical palaces, where you’ll trace the one-way route through the “Da Canova a Boccioni” exhibit, including marble reliefs by the Neoclassical sculptor Antonio Canova and Romantic paintings by Francesco Hayez. Upstairs, you’ll see dramatic and thrilling scenes from the unification of Italy, as well as beautiful landscapes and cityscapes, especially of Milan. (An entire room is devoted to depictions of the now-trendy Naviglio Grande canal area in its workaday prime.)

On your way back to the bank building and the rest of the exhibit, take a moment to poke around the courtyard to find the officina di restituzioni alle gallerie—a lab where you can watch art restorers at work. Rejoining the permanent exhibit, you’ll see paintings from the late 19th and early 20th centuries: Romantic landscapes; hyperrealistic, time-travel scenes of folk life; and Impressionism. Finally, you’ll catch up to the art of the late 20th century, tucked between old bank-teller windows.

These sights are listed roughly in the order you’ll reach them as you travel west from Piazza del Duomo. The first one is just a few short blocks from the cathedral, while the last is just over a mile away.

This oldest museum in Milan was inaugurated in 1618 to house Cardinal Federico Borromeo’s painting collection. It began as a teaching academy, which explains its many replicas of famous works of art. Highlights include original paintings by Botticelli, Caravaggio, and Titian—and, most important, a huge-scale sketch by Raphael and a rare oil painting by Leonardo da Vinci.

Cost and Hours: €15, Pinacoteca open Tue-Sun 10:00-18:00, closed Mon; Biblioteca open Mon-Fri 9:00-17:00, closed Sat-Sun; last entry one hour before closing, audioguide-€3, near Piazza del Duomo at Piazza Pio XI 2, Metro: Duomo or Cordusio, tel. 02-806-921, www.ambrosiana.eu.

Visiting the Museum: Pick up the English-language map locating the rooms and major works I highlight below, and rent the audioguide (covers both permanent and special exhibits). Then head upstairs to begin your visit.

Raphael’s Cartoon (Room 5): Filling an entire wall, this drawing served as an outline for Raphael’s famous School of Athens fresco at the Vatican Museums. (A cartoon—cartone in Italian—is a full-size sketch that’s used to transfer a design to another surface.) First, watch the five-minute video introduction. While the Vatican’s much-adored fresco is attributed entirely to Raphael, it was painted mostly by his students. But this cartone was wholly sketched by the hand of Raphael. To transfer the fresco design to the wall, his assistants riddled this cartoon with pinpricks along the outlines of the figures, stuck it to the wall of the pope’s study, and then applied a colored powder. (Where the master cared more about the detail, you’ll see more pinpricks.) When they removed the cartone, the figures’ shapes were marked on the wall, and completing the fresco was a lot like filling in a coloring book.

Jan Brueghel (Room 7): As Cardinal Borromeo was a friend of Jan Brueghel, this entire room is filled with delightful works by the artist and other Flemish masters. Study the wonderful detail in Brueghel’s Allegory of Fire and Allegory of Water. The Flemish paintings are extremely detailed—many are painted on copper to heighten the effect—and offer an insight into the psyche of the age. If the cardinal were asked why he enjoyed paintings that celebrated the secular life, he’d likely say, “Secular themes are God’s book of nature.”

Leonardo Hall (Room 24): During his productive Milan years, Leonardo painted (oil on wood) Portrait of a Musician—as delicate, mysterious, and thought-provoking as the Mona Lisa. (This is the only one of his paintings that remains in Milan.) The large fresco filling the far wall—with Christ receiving the crown of thorns—is by Bernardino Luini, one of Leonardo’s disciples. But I find the big replica painting of The Last Supper most interesting. When the cardinal realized that Leonardo’s marvelous frescoed original was fading, he commissioned Andrea Bianchi to paint on canvas a careful copy to be displayed here for posterity. Today, this copy gives a rare chance to appreciate the original colorful richness of the now-faded masterpiece.

Biblioteca Ambrosiana: The 17th-century library hosts a revolving display of Leonardo sketches and notes. These are from the precious Codex Atlanticus, with more than a thousand busy pages done by Leonardo for his own reference, giving us a peek into his amazing mind. On any given day 16 pages are on display with English descriptions.

This square and monument mark the center of Milan’s financial district. The bold fascist buildings in the neighborhood were built in the 1930s under Mussolini. Italy’s major stock exchange, the Borsa, faces the square. Stand in the center and appreciate the contemporary take on ancient aesthetics (you’re standing atop the city’s ancient Roman theater). Find the stern statues representing various labors and occupations and celebrating the nobility of workers—typical whistle-while-you-work fascist themes.

Now notice the equally bold modern statue in the center. After a 2009 contest to find the most appropriate sculpture to grace the financial district, this was the winner. With Italy’s continuing financial problems, here we see how “the 99 percent” feel when they stand before symbols of corporate power. (Notice how the finger is oriented—it’s the 1 percent, and not the 99 percent, who’s flipping the bird.) The 36-foot-tall Carrara marble digit was made by Maurizio Cattelan, the most famous—or, at least, most controversial—Italian sculptor of our age. L.O.V.E., as the statue is titled, was temporary at first. But locals liked it, and, by popular demand, it’s now permanent.

This church, part of a ninth-century convent built into a surviving bit of Milan’s ancient Roman wall, dates from around 1500. Despite its simple facade, it’s a hit with art lovers for its amazing cycle of Bernardino Luini frescoes. Stepping into this church is like stepping into the Sistine Chapel of Lombardy.

Cost and Hours: Free; Tue-Sun 9:30-19:30, closed Mon; Corso Magenta 15 at the Monastero Maggiore, Metro: Cadorna or Cairoli, tel. 02-8844-5208.

Visiting the Church: Bernardino Luini (1480-1532), a follower of Leonardo, was also inspired by his contemporaries Michelangelo and Raphael. Sit in a pew and take in the art, which has the movement and force of Michelangelo and the grace and calm beauty of Leonardo.

Maurizio, the patron saint of this church, was a third-century Roman soldier who persecuted Christians, then converted, and eventually worked to stop those same persecutions. He’s the guy standing on the pedestal in the upper right, wearing a bright yellow cape. The nobleman who paid for the art is to the left of the altar, kneeling and cloaked in black and white. His daughter, who joined the convent here and was treated as a queen (as nuns with noble connections were), is to the right. And all around are martyrs—identified by their palm fronds.

The adjacent Hall of Nuns (Aula delle Monache), a walled-off area behind the altar, is where cloistered sisters could worship apart from the general congregation. Fine Luini frescoes appear above and around the wooden crucifix. The Annunciation scene at the corners of the arch features a cute Baby Jesus zooming down from heaven (see Mary, on the right, ready to catch him). The organ dates from 1554, and the venue, with its fine acoustics, is popular for concerts with period instruments. Explore the pictorial Bible that lines the walls behind the wooden seats of the choir. Luini’s landscapes were groundbreaking in the 16th century. Leonardo incorporated landscapes into his paintings, but Luini was among the first to make landscape the main subject of the painting.

Nearby: You’ll exit the Hall of Nuns into the lobby of the adjacent Archaeological Museum, where you can pay €5 to see part of the ancient city wall and a third-century Roman tower.

One of Milan’s top religious, artistic, and historic sights, this church was first built on top of an early Christian martyr’s cemetery by St. Ambrose around AD 380, when Milan had become the capital of the fading (and Christian) western Roman Empire.

Cost and Hours: Free, Mon-Sat 10:00-12:30 & 14:30-18:00, Sun 15:00-17:00, modest attire required, Piazza Sant’Ambrogio 15, Metro: Sant’Ambrogio, tel. 02-8645-0895, www.basilicasantambrogio.it.

Visiting the Church: Ambrose was a local bishop and one of the great fathers of the early Church. Besides his writings, he’s remembered for converting and baptizing St. Augustine of Hippo, who himself became another great Church father. The original fourth-century church was later (in the 12th century) rebuilt in the Romanesque style you see today.

As you step “inside” from the street, you emerge into an arcaded atrium—standard in many churches back when people weren’t allowed to actually enter the church until they were baptized. The unbaptized waited here during Mass. The courtyard is textbook Romanesque, with playful capitals engraved with fanciful animals. Inset into the wall (right side, above the pagan sarcophagi) are stone markers of Christian tombs—a reminder that this church, like St. Peter’s at the Vatican, is built upon an ancient Roman cemetery.

From the atrium, marvel at the elegant 12th-century facade, or west portal. It’s typical Lombard medieval style. The local bishop would bless crowds from its upper loggia. As two different monastic communities shared the church and were divided in their theology, there were also two different bell towers.

Step into the nave and grab a pew. The mosaic in the apse features Christ Pantocrator (“All Powerful”) in the company of Milanese saints. Around you are pillars with Romanesque capitals and surviving fragments of the 12th-century frescoes that once covered the church.

The 12th-century pulpit sits atop a Christian sarcophagus dating from the year 400. Study its late Roman and early Christian iconography—on the side facing the altar, Apollo on his chariot morphs into Jesus on a chariot. You can see the moment when Jesus gave the Old Testament (the first five books, anyway) to his apostles.

The precious, ninth-century golden altar has four ancient porphyry columns under an elegant Romanesque 12th-century canopy. The entire ensemble was taken to the Vatican during World War II to avoid destruction. That was smart—the apse took a direct hit in 1943. A 13th-century mosaic was destroyed; today we see a reconstruction.

Step into the crypt, under the altar, to see the skeletal bodies of three people: Ambrose (in the middle, highest) and two earlier Christian martyrs whose tombs he visited before building the church.

Nearby: For a little bonus after visiting the church, consider this: The Benedictine monastery next to the church is now Cattolica University. With its stately colonnaded courtyards designed by Renaissance architect Donato Bramante, it’s a nice place to study. It’s fun to poke around and imagine being a student here.

The spirit of Leonardo lives here (a 10-minute walk from his Last Supper). Most tourists focus on the hall of Leonardo—the core of the museum—where wooden models illustrate his designs. But the rest of this immense collection of industrial cleverness is fascinating in its own right. There are exhibits on space exploration, mining, and radio and television (with some original Marconi radios); old musical instruments, computers, and telephones; chunks of the first transatlantic cable; and interactive science workshops. Out back are several more buildings containing antique locomotives and a 150-foot-long submarine from 1957. Ask for an English museum map from the ticket desk—you’ll need it. On weekends, this museum is very popular with families, so come early or be prepared to wait in line.

Cost and Hours: €10; Tue-Fri 10:00-18:00, Sat-Sun until 19:00, shorter hours off-season, closed Mon year-round; Via San Vittore 21, Metro: Sant’Ambrogio; tel. 02-485-551, www.museoscienza.org.

Decorating the former dining hall (cenacolo) of the Church of Santa Maria delle Grazie, this remarkable, exactingly crafted fresco is one of the ultimate masterpieces of the Renaissance. Reservations are mandatory and should be booked long in advance.

Cost and Hours: €15 (includes €2 reservation fee), four time slots include a tour and cost an extra €3.50 (9:30 and 15:30 in English; 10:00 and 16:00 in Italian); open Tue-Sun 8:15-18:45 (last entry), closed Mon, arrive 20 minutes before your timed entry; Piazza Santa Maria delle Grazie 2; tel. 02-9280-0360, http://cenacolovinciano.org.

Reservations: Mandatory timed-entry reservations can be made by phone or online—but they can sell out in minutes. Tickets for each calendar month go on sale about three months ahead; for example, bookings for July open in April. Check the website to find out when tickets for your dates will be released. For peak season tickets, be ready to book the moment they’re released (Milan time).

To book online, go to http://cenacolovinciano.vivaticket.it (you’ll have to create an account to book tickets). A calendar shows available time slots for the coming months. If your time slot includes a tour, you must add the €3.50 tour supplement when you check out (you won’t be able to buy a ticket without it).

If you book by phone, you’ll have more days and time slots to choose from (no same-day tickets, tel. 02-9280-0360, from the US dial 011-39-02-9280-0360, office open Mon-Sat 8:00-18:30, closed Sun; the number is often busy--once you get through, select 2 for an English-speaking operator).

Tour Option: If you can’t get a reservation, you can book a pricier (€65-80) walking or bus tour that includes a guided visit to The Last Supper. Reserve at least a week ahead (see here).

Last-Minute Tickets: A few same-day spots may be available due to cancellations. You can try showing up and asking at the desk--even if the sold out sign is posted (ideally when the office opens at 8:00, more likely on weekdays).

Getting There: The Church of Santa Maria delle Grazie is a seven-minute walk from Metro: Conciliazione. From the track, follow signs for Cenacolo. You’ll walk four blocks. After the first bend you’ll see the fine red-brick facade of the church ahead. Or take tram #16 from the Duomo (direction: San Siro or Piazzale Segesta), which drops you off in front of the church. When leaving, cross the street to catch the tram back to the Duomo.

Getting In: Stow your bag (free, required), pick up your ticket, and consider renting the audioguide. Your time will be called 15 minutes before, and you’ll enter the waiting room. Use this time to study up. At your appointed time, the doors open and your group enters. No stress, no crowds, beautifully organized...it’s a peaceful and inspiring experience. There’s a fine WC at the exit.

Audioguide: The fine €3.50 audioguide (standard jack) is very helpful. Its spiel fills every second of the time you’re in the room—a short intro (#100) and then tracks 1 through 5—for the entire 15 minutes you’re inside. You can start listening to it in the waiting room while studying the reproduction of The Last Supper.

Background: Milan’s leading family, the Sforzas, hired Leonardo to decorate the dining hall of the Dominican monastery that adjoins the church (the Dominican order traditionally placed a Last Supper on one end of their refectories, and a Crucifixion at the other). Leonardo worked on the project from about 1494 until 1498. This gift was essentially a bribe to the monks so that the Sforzas could place their family tomb in the church. Ultimately, the French drove the Sforzas out of Milan, they were never buried here, and the Dominicans got a great fresco for nothing.

Deterioration began within six years of The Last Supper’s completion because Leonardo painted on the wall in layers, as he would on a canvas, instead of applying pigment to wet plaster in the usual fresco technique. (Examining the extremely close-up photos in the waiting room lets you see how the paint is simply flaking off.) The church was bombed in World War II, but—miraculously, it seems—the wall holding The Last Supper remained standing. A 21-year restoration project (completed in 1999) peeled away 500 years of touch-ups, leaving Leonardo’s masterpiece faint but vibrant.

Visiting The Last Supper: To minimize damage from humidity, only 30 tourists are allowed in every 15 minutes for exactly 15 minutes. While you wait, read the history of the masterpiece or listen to the audioguide. As your appointed time nears, you’ll be herded between several rooms to dehumidify, while doors close behind you and open up slowly in front of you.

And then the last door opens, you take a step, you look right, and...there it is. In a big, vacant, whitewashed room, you’ll see faded pastels and not a crisp edge. The feet under the table look like negatives. But the composition is dreamy—Leonardo captures the psychological drama as the Lord says, “One of you will betray me,” and the apostles huddle in stressed-out groups of three, wondering, “Lord, is it I?” Some are scandalized. Others want more information. Simon (on the far right) gestures as if to ask a question that has no answer. In this agitated atmosphere, only Judas (fourth from left and the only one with his face in shadow)—clutching his 30 pieces of silver and looking pretty guilty—is not shocked.

The circle meant life and harmony to Leonardo. Deep into a study of how life emanates in circles—like ripples on a pool hit by a pebble—Leonardo positioned the 13 characters in a semicircle. Jesus is in the center, from whence the spiritual force of God emanates, or ripples out.

The room depicted in the painting seems like an architectural extension of the monk’s dining hall. The disciples form an apse, with Jesus as the altar—in keeping with the Eucharist. Jesus anticipates his sacrifice, his face sad, all-knowing, and accepting. His feet even foreshadow his death by crucifixion. Had the door, which was cut out in 1652, not been added, you’d see how Leonardo placed Jesus’ feet atop each other, ready for the nail.

The perspective is mathematically correct, with Jesus’ head as the vanishing point where the converging sight lines meet. In fact, restorers found a tiny nail hole in Jesus’ left eye, which anchored the strings Leonardo used to establish these lines. The table is cheated out to show the meal. Notice the exquisite lighting. The walls are lined with tapestries (as they would have been), and the one on the right is brighter in order to fit the actual lighting in the refectory (which has windows on the left). With the extremely natural effect of the light and the drama of the faces, Leonardo created a masterpiece.

The monks ate at three tables just like the one Leonardo painted, with a carefully ironed tablecloth also just like the one painted. The monks ate in silence, communicating with hand gestures (notice the ballet of hand gestures in Leonardo’s composition).

Save a minute or two for the fresco of the Crucifixion on the opposite wall, which provides an instructive contrast. This is done in the traditional fresco technique—less soul and subtlety but much better preserved. It needed to be done quickly (as the plaster dried) and was finished in three months (compared to over three years for The Last Supper). For a good look at the contrasting styles, find the faded image of the Sforza duchess in the lower right corner. She was added to the scene by Leonardo using the same technique he used in The Last Supper.

Before stepping out, from the back of the room look one last time at Leonardo’s masterpiece and imagine this room filled with three more tables and 60 monks immersed in devotion and with no idea that 500 years later travelers would be dropping by to appreciate the art decorating their hall.

The adjacent Church of Santa Maria delle Grazie survived World War II unscathed and is worth a quick look (free). Its fine Gothic arches lead to a Renaissance Bramante-designed dome. The Dominican monks frescoed in black and white on each pilaster were the first monks to eat under Leonardo’s Last Supper.

Milan’s top collection of Italian paintings (13th-20th century) is world class, but it can’t top those in Rome or Florence. Established in 1809 to house Napoleon’s looted art, it fills the first floor above a prestigious art college. You’ll dodge scruffy starving artists...and wonder if there’s a 21st-century Leonardo in your midst.

Cost and Hours: €12, free first Sun of month; Tue-Sun 8:30-19:15, closed Mon, last entry 45 minutes before closing; audio-guide–€5 (useful, ID required, but museum has excellent English descriptions), free lockers, Via Brera 28, Metro: Lanza or Montenapoleone, tel. 02-722-631, www.pinacotecabrera.org.

Visiting the Museum: Enter the grand courtyard of a former monastery, where you’ll be greeted by the nude Napoleon with Tinkerbell (by Antonio Canova). Climb the stairway (following signs to Pinacoteca), buy your ticket, and pick up an English map of the museum’s masterpieces, some of which I’ve highlighted below. You’ll follow a clockwise, chronological route through the huge collection. Take time to read the English descriptions, many of which are absolutely poetic. And, to get the most out of your visit, invest in the audioguide. Here are the highlights:

Next to the information desk peek through the window to see the 300-year-old library, then pop into the chapel (on the left) frescoed by a follower of Giotto in the 1300s. After the turnstile, enjoy the setup in the short entry hall.

Before Antonio Canova’s big marble statue of naked Napoleon, head left into the dark, narrow blue hall to see Andrea Mantegna’s iconic foreshortened Christ (and others by the influential early Renaissance master). Room 8 features more Mantegna, and bright and vivid paintings by the Bellini brothers from around 1500. Room 9 is for the big canvases by 16th-century Venetian masters (like Tintoretto and Paolo Veronese).

Past the towering marble statue of Napoleon, Room 15 holds four paintings by Vincenzo Campi, offering slices of local Milan life from 1591.

Then you reach the restoration lab, which offers a chance to peek in on the hard work of keeping these paintings looking so good.

Room 22 sparkles with High Gothic art. Carlo Crivelli, a contemporary of Leonardo, employed Renaissance technique while clinging to the mystique of the Gothic Age (that’s why I like him so much). And Gentile da Fabriano hints at the realism of the coming Renaissance (check out the lifelike flowers and realistic, bright gold paint—he used real gold powder).

Room 26 is nicknamed “The Golden Room” for its Renaissance masterpieces from the early 16th century by Raphael (The Marriage of the Virgin), Piero della Francesca (Madonna and Child with Saints), and Donato Bramante.

In Room 28 don’t miss gritty-yet-intimate realism of Caravaggio’s Supper at Emmaus. Room 31 features Rubens (and other Dutch and Flemish works). And Room 35 is dedicated to “postcard” art from the 18th-century Grand Tour days (like Venice-scapes by Canaletto and Francesco Guardi).

Finally, in Room 37 you come to 19th-century Romanticism, and in Room 38 three patriotic paintings, including The Kiss by Francesco Hayez, which evoke the spirit of Italy’s fight for independence, the Risorgimento.

With a quick swing through this quiet one-floor museum, you’ll get an idea of the interesting story of Italy’s rocky road to unity: from Napoleon (1796) to the victory in Rome (1870). You’ll see paintings, uniforms, monuments, a city model, and other artifacts. Thoughtful English descriptions help make this a meaningful look at this important period of Italian history.

Cost and Hours: Free; Tue-Sun 9:00-13:00 & 14:00-17:30, closed Mon; just around the block from Brera Art Gallery at Via Borgonuovo 23, Metro: Montenapoleone, tel. 02-8846-4176, www.museodelrisorgimento.mi.it.

This classy house of art features Italian paintings of the 15th through 18th century, old weaponry, and lots of interesting decorative arts, such as a roomful of old sundials and compasses. It’s all on view in a sumptuous 19th-century residence.

Cost and Hours: €10; Wed-Mon 10:00-18:00, closed Tue; audioguide-€1, Via Manzoni 12, Metro: Montenapoleone, tel. 02-794-889, www.museopoldipezzoli.it.

This unique 19th-century collection of Italian Renaissance furnishings was assembled by two aristocratic brothers who spent a wad turning their home into a Renaissance mansion.

Cost and Hours: €9, includes audioguide, €6 on Wed; Tue-Sun 13:00-17:45, closed Mon; Via Gesù 5, Metro: Montenapoleone, tel. 02-7600-6132, www.museobagattivalsecchi.org.

The castle of Milan tells the story of the city in brick. Today it features a vast courtyard, a sprawling museum, and—most importantly—a chance to see Michelangelo’s final, unfinished pietà.

Cost and Hours: €10; museum open Tue-Sun 9:00-17:30, closed Mon; castle grounds open daily 7:00-19:30; WCs and free/mandatory lockers downstairs from ticket counter, Metro: Cairoli or Lanza, tel. 02-8846-3700, www.milanocastello.it.