Pompeii • Herculaneum • Vesuvius

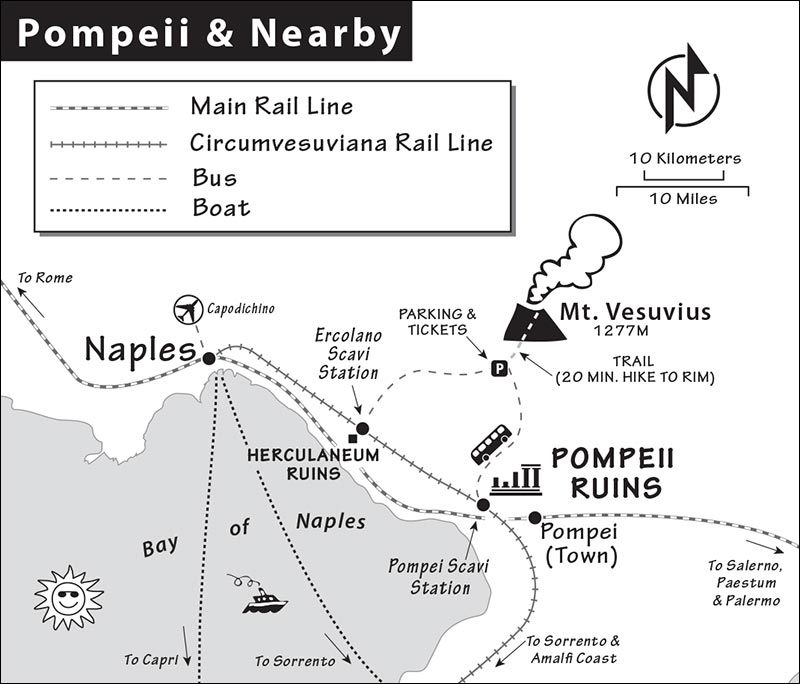

Stopped in their tracks by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79, Pompeii and Herculaneum offer the best look anywhere at what life in Rome must have been like around 2,000 years ago. These two cities of well-preserved ruins are yours to explore. Of the two sites, Pompeii is grander, while Herculaneum is smaller, more intimate, and more intact. Pompeii is easily reached from Naples on the CitySightseeing bus or the Circumvesuviana commuter (or Campania Express) train; Herculaneum is best reached by train. Vesuvius, still smoldering ominously, rises up on the horizon. It last erupted in 1944, and is still an active volcano. Buses from the train stations at Herculaneum or Pompeii drop you a half-hour hike below its crater rim.

A once-thriving commercial port of 20,000, Pompeii (worth ▲▲▲) grew from Greek and Etruscan roots to become an important Roman city. Then, on August 24, AD 79, everything changed. Vesuvius erupted and began to bury the city under 30 feet of hot volcanic ash. For the archaeologists who excavated it centuries later, this was a shake-and-bake windfall, teaching them volumes about daily Roman life. Pompeii was accidentally rediscovered in 1599; excavations began in 1748.

By Train or Train-and-Bus Combo from Rome: It’s possible to day-trip to Pompeii from Rome, if you start early and plan on a long day. For tips, see the “Planning Your Time” section in the Naples chapter.

By Shuttle Bus from Naples: CitySightseeing Italy offers a convenient, clean, and stress-free shuttle bus from Naples to Pompeii. The bus also allows you to experience Naples’ insane traffic without actually having to drive in it (a spectacle almost worth ▲). Three pick-up points are handy to all my recommended Naples hotels: the Molo Beverello boat dock, Piazza Bovio near the Università Metro stop, and Centrale Station (stop located across the street and left when exiting, near the Hotel D’Anna).

Tickets can be purchased online, but be aware that each bus has a specific return time about four hours after arrival; no return-trip changes are allowed. Early morning departures beat the heat at Pompeii, but traffic congestion can delay your arrival and cut into your sightseeing time. Departures from Centrale Station in summer are at 9:30, 10:15, and 11:15, with corresponding return trips at 13:20, 14:40, and 16:00; fewer departures off-season; 30-minute ride from the train station if traffic is light (€8 one-way, €15 round-trip, tel. 081-551-7279, www.city-sightseeing.it). Skip the option to purchase your Pompeii entrance ticket through CitySightseeing—you’ll pay more than buying it yourself online (details later).

By Train from Naples or Sorrento: Pompeii is roughly midway between Naples and Sorrento on the crowded, run-down Circumvesuviana commuter train line (2/hour, 35 minutes from Naples, 30 minutes from Sorrento, either trip costs €2.90 one-way, not covered by rail passes, no air-con, Italian-only website: www.eavsrl.it). Get off at the Pompei Scavi-Villa dei Misteri stop; from Naples, it’s the stop after Villa Regina. DD express trains (6/day) bypass several stations but do stop at Pompei Scavi, shaving 10 minutes off the trip from Naples.

Less-frequent Campania Express trains use the same tracks and stops, but are less crowded and have air-conditioning (4/day, 30 minutes from Naples, 25 minutes from Sorrento, either trip costs €6 one-way, mid-March-Oct only, http://ots.eavsrl.it). For train details, see here.

From the Pompei Scavi train station, it’s just a two-minute walk to the Porta Marina entrance: Leaving the station, turn right and walk down the road about a block to the entrance (on your left).

Pompei vs. Pompei Scavi: Make sure you’re taking the Circumvesuviana commuter train or Campania Express to Pompei Scavi (scavi means “excavations”), the station right next to the ancient site. Pompei is the name of a separate train station on the main national rail line that’s a long, dull walk from the ruins. It serves the ugly modern city of Pompei (always with one “i”).

When coming from Rome, it’s better to transfer at Naples’ Centrale Station to the CitySightseeing shuttle bus (or the Circumvesuviana/Campania Express for Pompei Scavi) than to take the national rail straight to the Pompei city station and walk from there.

By Car: Parking is available at Camping Zeus, next to the Pompei Scavi train station (€2.50/hour, €10/12 hours); several other campgrounds/parking lots are nearby.

Cost: €16, includes special exhibits. Consider the Campania ArteCard (see here) if visiting other sights in the region.

Hours: Mon-Fri 9:00-19:30, Sat-Sun 8:30-19:30, Nov-March daily until 17:00, last entry 1.5 hours before closing.

Free Entry: Some state museums in Italy, including Pompeii, are free to enter once or twice a month, usually on a Sunday. Check in advance and avoid these free days—they’re packed.

Information: Tel. 081-857-5347, general info at www.pompeiisites.org, tickets at www.ticketone.it.

Crowd-Beating Tips: To skip ahead of everyone, purchase your ticket online at www.ticketone.it (€2 surcharge). If you’re buying onsite and there’s a very long ticket line at the Porta Marina entrance, continue walking three minutes to the ticket booth near Hotel Vittoria (rarely a line). Buy your ticket, return to Porta Marina, and walk right in.

Closures: Some buildings and streets are bound to be closed for restoration when you visit. Make a point to use your map and numbers to find your way. Street names and building numbers are very clearly marked throughout the site.

Visitor Information: Admission includes a wonderful English guidebooklet and map (be sure to get and use this). Ask for it when you buy your ticket, or check at the info window to the left of the WCs—the maps aren’t available within the walls of Pompeii.

The bookshop sells a couple of books with plastic overlays that allow you to re-create Pompeii from the ruins (€16; if you buy from a street vendor, pay no more than that). Another good book is the €6 Pompeii (Brief) Guide, with excellent photos and additional walking routes.

Ignore the “info point” kiosk at the train station, which is a private agency selling tours.

Tours: Here are several ways to enjoy an organized and educational visit to Pompeii.

Simply follow the self-guided tour in this chapter (or, better, enjoy the audio version with my free  Rick Steves Audio Europe app). Both cover the basics and provide a good framework for exploring the site on your own. Combined with the fine booklet and map included with your entry fee, these provide plenty of information for do-it-yourselfers.

Rick Steves Audio Europe app). Both cover the basics and provide a good framework for exploring the site on your own. Combined with the fine booklet and map included with your entry fee, these provide plenty of information for do-it-yourselfers.

Join a Mondo Guide shared tour for Rick Steves readers. This is your best budget bet for a tour with an actual guide (€15, doesn’t include €15 Pompeii entry, daily at 11:00, reservations required; meet at Hotel/Ristorante Suisse, just down the hill from the Porta Marina entrance; for details, see here).

Hire guide Antonio Somma for a private or shared tour. Antonio and his team of guides offer good two-hour tours of Pompeii for €120 (mobile 393-406-3824, tel. 081-850-1992, www.tourspompeiiguide.com, info@pompeitour.com). The tour can be just for you, or, if you wish, they can try to book other travelers for the same tour to share the cost. Either way, the total price is no more than €120. For example, if six people take the tour, each pays €20. (A nice tip for the guide’s extra effort is appreciated.)

Other Options: Audioguides available from a kiosk near the ticket booth at the Porta Marina entrance (€8, €13 for 2, ID required) offer basically the same info as your free booklet.

When you step off the train, you’ll likely be accosted by touts for the “info point” kiosk, which sells €15 tours that depart whenever enough people sign up. Private guides (around €120/2 hours) of varying quality cluster near the ticket booth at the site and may try to herd you into a group with other travelers, which is fine if it makes the price more reasonable. It’s unethical for a guide to double charge by combining two groups into one tour. Instead, tourists should enjoy the savings and tip higher.

Rated Risqué: Parents, note that the ancient brothel and its sexually explicit frescoes are included on tours; let your guide know if you’d rather skip that stop.

Length of This Tour: Allow two hours, or three if you visit the theater and amphitheater. With less time, focus on the Forum, Baths of the Forum, House of the Vettii, House of the Faun, and brothel.

Baggage Check: Use the free baggage check near the turnstiles at the site entrance (just yards from the station). The train station also offers pay luggage storage (downstairs, by the WC).

Services: There’s a pay WC at the train station. The Pompeii site has three WCs—one near the entrance, one in the cafeteria, and another near the end of this tour, uphill from the theaters.

Eating: These $ eateries offer reasonably priced meals (though your cheapest bet may be to bring your own food for a discreet picnic).

The Ciao cafeteria, within the site, serves good sandwiches, pizza, and pasta. You’re welcome to picnic here if you buy a drink. Bar Sgambati, the café/restaurant at the train station, has air-conditioning, Wi-Fi, sandwiches to go, and pastas and pizzas. Marius Juice Shop (run by local guide Antonio Somma’s family) sells sandwiches to go, and is located between Bar Sgambati and the Porta Marina entrance.

A second cluster of eateries around the ticket booth near Hotel Vittoria dishes out handy slices of pizza, salads, and pasta.

Starring: Roofless (collapsed) but otherwise intact Roman buildings, plaster casts of hapless victims, some erotic frescoes, and the dawning realization that these ancient people were not that different from us.

Pompeii, founded in 600 BC, eventually became a booming Roman trading city. Not rich, not poor, it was middle class—a perfect example of typical Roman life. Most streets would have been lined with stalls and jammed with customers from sunup to sundown. Chariots vied with shoppers for street space. Two thousand years ago, Rome controlled the entire Mediterranean—making it a kind of free-trade zone—and Pompeii was a central and bustling port.

There were no posh neighborhoods in Pompeii. Rich and poor mixed it up as elegant houses existed side by side with simple homes. While nearby Herculaneum would have been a classier place to live (traffic-free streets, fancier houses, far better drainage), Pompeii was the place for action and shopping. It served an estimated 20,000 residents with more than 40 bakeries, 130 bars, restaurants and hotels, and 30 brothels. With most of its buildings covered by brilliant white ground-marble stucco, Pompeii in AD 79 was an impressive town.

As you tour Pompeii, remember that its best art is safeguarded in the Archaeological Museum in Naples (described in the Naples chapter). Visiting the museum before or after going to Pompeii will help put this fascinating sight into context.

SELF-GUIDED TOUR

SELF-GUIDED TOUR4 Basilica

7 Baths of the Forum (Terme del Foro)

9 House of the Tragic Poet (Casa del Poeta Tragico)

10 Aqueduct Arch—Running Water

11 House of the Faun (Casa del Fauno)

House of Menander (Casa di Menandro)

• Just past the ticket-taker, start your approach up to the...

The city of Pompeii was born on the hill ahead of you. This was the original town gate. Before Vesuvius blew and filled in the harbor, the sea came nearly to here. Notice the two openings in the gate (ahead, up the ramp). Both were left open by day to admit major traffic. At night, the larger one was closed for better security.

• Pass through the Porta Marina and continue up to the top of the street, pausing at the three large stepping-stones in the middle.

Every day, Pompeiians flooded the streets with gushing water to clean them. These stepping-stones let pedestrians cross without getting their sandals wet. Chariots traveling in either direction could straddle the stones (all had standard-size axles). A single stepping-stone in a road means it was a one-way street, a pair indicates an ordinary two-way, and three (like this) signifies a major thoroughfare. The basalt stones are the original Roman pavement. The sidewalks (elevated to hide the plumbing—you’ll see ancient plumbing revealed throughout the site) were paved with bits of broken pots (an ancient form of recycling) and studded with reflective bits of white marble. These “cats’ eyes” helped people get around after dark, either by moonlight or with the help of lamps.

• Continue straight ahead, don your mental toga, and enter the city as the Romans once did. The road opens up into the spacious main square: the Forum. Stand at the right end of this rectangular space and look toward Mount Vesuvius.

Pompeii’s commercial, religious, and political center stands at the intersection of the city’s two main streets. While it’s the most ruined part of Pompeii, it’s grand nonetheless. Picture the piazza surrounded by two-story buildings on all sides. The pedestals that line the square once held statues of VIPs and various gods (now safely displayed in the museum in Naples). In Pompeii’s heyday, its citizens gathered here in the main square to shop, talk politics, and socialize. Business took place in the important buildings that lined the piazza.

The Forum was dominated by the Temple of Jupiter, at the far end (marked by a half-dozen ruined columns atop a stair-step base). Jupiter was the supreme god of the Roman pantheon—you might be able to make out his little white marble head at the center-rear of the temple. To the left of the temple is a fenced-off area, the Forum granary, where many artifacts from Pompeii are stored (and which we’ll visit later).

At the near end of the Forum (behind where you’re standing) is the curia, or City Hall. Like many Roman buildings, it was built with brick and mortar, then covered with marble walls and floors. To your left (as you face Vesuvius and the Temple of Jupiter) is the basilica, or courthouse.

Since Pompeii was a pretty typical Roman town, it has the same layout and components that you’ll find in any Roman city—main square, curia, basilica, temples, axis of roads, and so on. All power converged at the Forum: religious (the temple), political (the curia), judicial (the basilica), and commercial (this piazza was the main marketplace). Even the power of the people was expressed here, since this is where they gathered to vote. Imagine the hubbub of this town square in its heyday.

Look beyond the Temple of Jupiter. Five miles to the north looms the ominous backstory to this site: Mount Vesuvius. Mentally draw a triangle up from the two remaining peaks to reconstruct the mountain before the eruption. When it blew, Pompeiians had no idea that they were living under a volcano, as Vesuvius hadn’t erupted for 1,200 years. Imagine the wonder—then the horror—as a column of pulverized rock roared upward, and then ash began to fall. The weight of the ash and small rocks collapsed Pompeii’s roofs later that day, crushing people who had taken refuge inside buildings instead of fleeing the city.

• As you face Vesuvius, the basilica is to your left, lined with stumps of columns. Step inside.

Pompeii’s basilica was a first-century palace of justice. This ancient law court has the same floor plan later adopted by many Christian churches (which are also called basilicas). The big central hall (or nave) is flanked by rows of columns marking off narrower side aisles. Along the side walls are traces of the original stucco imitating marble.

The columns—now stumps all about the same height—were not ruined by the volcano. Rather, they were left unfinished when Vesuvius blew. Pompeii had been devastated by an earthquake in AD 62, and was just in the process of rebuilding the basilica when Vesuvius erupted, 17 years later. The half-built columns show off the technology of the day. Uniform bricks were stacked around a cylindrical core. Once finished, they would have been coated with marble-dust stucco to simulate marble columns—an economical construction method found throughout Pompeii (and the Roman Empire).

Besides the earthquake and the eruption, Pompeii’s buildings have suffered other ravages over the years, including Spanish plunderers (c. 1800), 19th-century souvenir hunters, WWII bombs, creeping and destructive vegetation, another earthquake in 1980, and modern neglect. The fact that the entire city was covered by the eruption of AD 79 actually helped preserve it, saving it from the sixth-century barbarians who plundered many other towns into oblivion.

• Exit the basilica and cross the short side of the square to where the city’s main street hits the Forum. Stop at the three white stones that stick up from the cobbles.

Glance down Via Abbondanza, Pompeii’s main street. Lined with shops, bars, and restaurants, it was a lively, pedestrian-only zone. The three “beaver-teeth” stones are traffic barriers that kept chariots out. On the corner at the start of the street (just to the left), take a close look at the dark travertine column standing next to the white one. Notice that the marble drums of the white column are not chiseled entirely round—another construction project left unfinished when Vesuvius erupted.

• Our tour will eventually end a few blocks down Via Abbondanza after making a big loop. But now, head toward Vesuvius, cutting across the Forum. To the left of the Temple of Jupiter is the...

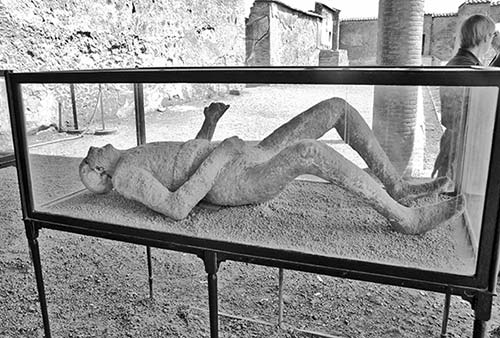

A substantial stretch of the west side of the Forum was the granary and ancient produce market. Today, it houses thousands of artifacts excavated from Pompeii. You’ll see lots of crockery, pots, pans, jugs, and containers used for transporting oil and wine. You’ll also see casts of a couple of victims (and a dog) of the eruption. These casts show Pompeiians eerily captured in their last moments, hands covering their mouths as they gasped for air. They were quickly suffocated by a superheated avalanche of gas and ash, and their bodies were encased in volcanic debris. While excavating, modern archaeologists detected hollow spaces underfoot, created when the victims’ bodies decomposed. By gently filling the holes with plaster, the archaeologists created molds of the Pompeiians who were caught in the disaster.

A few steps to the left of the granary is a tiny alcove that contained the Mensa Ponderaria, a counter where standard units (such as today’s liter or gallon) were used to measure the quantities of liquid and solid food that were sold. And just to the right of the granary is the remains of a public toilet. You can imagine the many seats, lack of privacy, and constantly flushing stream running through the room.

• Exit the Forum by crossing it again in front of the Temple of Jupiter and turning left. Go under the arch. In the road are more “beaver-teeth” traffic blocks. On the pillar to the right, look for the pedestrian-only road sign (two guys carrying an amphora, or ancient jug; it’s above the REG VII INS IV sign). The modern cafeteria (on the left) is the only eatery inside the archaeological site. Twenty yards past the cafeteria, on the left-hand side at #24, is the entrance to the...

Pompeii had six public baths, each with a men’s and a women’s section. You’re in the men’s zone. The leafy courtyard at the entrance was the gymnasium. After working out, clients could relax with a hot bath (caldarium), warm bath (tepidarium), or cold plunge (frigidarium).

The first big, plain room you enter served as the dressing room. Holes on the walls were for pegs to hang clothing. High up, the window (with a faded Neptune underneath) was originally covered with a less-translucent Roman glass. Walk over the nonslip mosaics into the next room.

The tepidarium is ringed by mini statues or telamones (male caryatids, figures used as supporting pillars), which divided the lockers. Clients would undress and warm up here, perhaps relaxing on one of the bronze cow-footed benches near the bronze heater while waiting for a massage. Look at the ceiling—half crushed by the eruption and half intact, with its fine blue-and-white stucco work.

Next, admire the engineering in the steam-bath room, or caldarium. The double floor was heated from below—so it was nice for bare feet (look into the grate across from where you entered to see the brick support towers). The double walls with brown terra-cotta tiles held the heat. Romans soaked in the big tub, which was filled with hot water. Opposite the big tub is a fountain, which spouted water onto the hot floor, creating steam. The lettering on the fountain reminded those enjoying the room which two politicians paid for it...and how much it cost them. (On the far right, the Roman numerals indicate they paid 5,250 sestertii). To keep condensation from dripping annoyingly from the ceiling, fluting (ribbing) was added to carry water down the walls.

• Today’s visitors exit the baths through the original entry (at the far end of the dressing room). Hungry? Immediately across the street is an ancient...

After a bath, it was only natural to want a little snack. So, just across the street is a fast-food joint, marked by a series of rectangular marble counters. Most ancient Romans didn’t cook for themselves in their tiny apartments, so to-go places like this were commonplace. The holes in the counters held the pots for food. Each container was like a thermos, with a wooden lid to keep the soup hot, the wine cool, and so on. You could dine in the back or get your food to go. Notice the groove in the front doorstep and the holes out on the curb. The holes likely accommodated cords for stretching awnings over the sidewalk to shield the clientele from the hot sun, while the grooves were for the shop’s folding accordion doors. Look at the wheel grooves in the pavement, worn down through centuries of use. Nearby are more stepping-stones for pedestrians to cross the flooded streets.

• Just a few steps uphill from the fast-food joint, at #5 (with a locked gate), is the...

This house is typical Roman style. The entry is flanked by two family-owned shops (each with a track for a collapsing accordion door). The home is like a train running straight away from the street: atrium (with skylight and pool to catch the rain), den (where deals were made by the shopkeeper), and garden (with rooms facing it and a shrine to remember both the gods and family ancestors). In the entryway is the famous “Beware of Dog” (Cave Canem) mosaic.

When it’s open, today’s visitors enter the home by the back door (circle around to the left). On your way there, look for the modern exposed pipe on the left side of the lane; this is the same as ones used in the ancient plumbing system, hidden beneath the raised sidewalk. The richly frescoed dining room is off the garden. Diners lounged on their couches (the Roman custom) and enjoyed frescoes with fake “windows,” giving the illusion of a bigger and airier room. Next to the dining room is a humble BBQ-style kitchen with a little closet for the toilet (the kitchen and bathroom shared the same plumbing).

• Return to the fast-food place and continue about 10 yards downhill to the big intersection. From the center of the intersection, look left to see a giant arch, framing a nice view of Mount Vesuvius.

Water was critical for this city of 20,000 people, and this arch was part of Pompeii’s water-delivery system. A 100-mile-long aqueduct carried fresh water down from the hillsides to a big reservoir perched at the highest point of the city wall. Since overall water pressure was disappointing, Pompeiians built arches like the brick one you see here (originally covered in marble) with hidden water tanks at the top. Located just below the altitude of the main tank, these smaller tanks were filled by gravity and provided each neighborhood with reliable pressure. Look closely at the arch and you’ll see 2,000-year-old pipes (made of lead imported all the way from Cornwall in Britannia) embedded deep in the brick.

If there was a water shortage, democratic priorities prevailed: First the baths were cut off, then the private homes. The last to go were the public fountains, where all citizens could get drinking and cooking water.

• If you’re thirsty, fill your water bottle from the modern fountain. Then continue straight downhill one block (50 yards) to #2 on the left.

Stand across the street and marvel at the grand entry with “HAVE” (hail to you) as a welcome mat. Go in. Notice the two shrines above the entryway—one dedicated to the gods, the other to this wealthy family’s ancestors. (Contemporary Neapolitans still carry on this practice; you’ll notice little shrines embedded in walls all over Naples.)

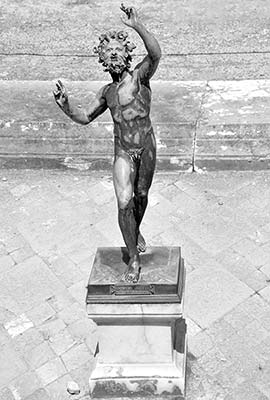

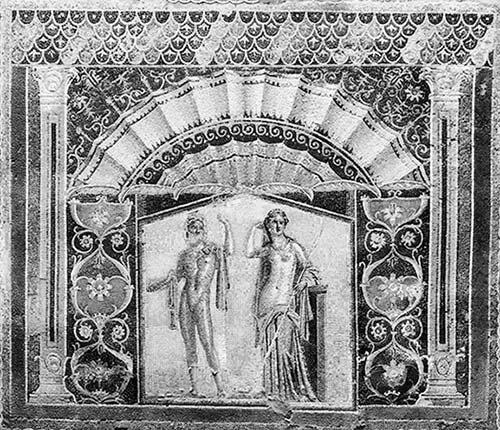

You are standing in Pompeii’s largest home, where you’re greeted by the delightful small bronze statue of the Dancing Faun, famed for its realistic movement and fine proportion. (The original, described on here, is in Naples’ Archaeological Museum.) With 40 rooms and 27,000 square feet, the House of the Faun covers an entire city block. The next floor mosaic, with an intricate diamond-like design, decorates the homeowner’s office. Note the pieces of multicolored stone that remain embedded in the floor, and think of how vibrant and luxurious this house would have seemed before the eruption. Beyond that, at the far end of the first garden, is the famous floor mosaic of the Battle of Alexander. (The original is also at the museum in Naples.) In 333 BC, Alexander the Great beat Darius and the Persians. Romans had much respect for Alexander, the first great emperor before Rome’s. While most of Pompeii’s nouveau riche had notoriously bad taste and stuffed their palaces with over-the-top, mismatched decor, this guy had class. Both the faun (an ancient copy of a famous Greek statue) and the Alexander mosaic show an appreciation for history.

The house’s back courtyard is lined with pillars rebuilt after the AD 62 earthquake. Take a close look at the brick, mortar, and fake-marble stucco veneer.

• Leave the House of the Faun through its back door in the far-right corner, past a tiny guard’s station. (If closed, exit out the front and walk around to the back.) Turn right and walk about a block until you see metal cages over the sidewalk protecting exposed stretches of ancient lead water pipes. Continue east and take your first left, walking about 20 yards to the entrance (on your left) to the...

This is Pompeii’s best-preserved home, retaining many of its mosaics and frescoes. The House of the Vettii was the bachelor pad of two wealthy merchant brothers. In the entryway, it’s hard to miss the huge erection. This was not pornography. This was a symbol of success: The penis and sack of money balance each other on the goldsmith scale above a fine bowl of fruit. Translation? Only with a balance of fertility and money can you enjoy true abundance.

Step into the atrium with its replica wooden ceiling open to the sky and a lead pipe to collect water for the house cistern. The pool was flanked by two large moneyboxes (one survives, the footprint of the other shows how it was secured to the ground). The brothers wanted all who entered to know how successful they were. A variety of rooms give an intimate peek at elegant Pompeiian life. The dark room to the right of the entrance (as you face out) is filled with exquisite frescoes. Notice more white “cat’s eye” stones embedded in the floor. Imagine these glinting like little eyes as the brothers and their friends wandered around by oil lamp late at night, with their sacks of gold, bowls of fruit, and enormous...egos.

• Our next stop, the Bakery, is located about 150 yards south (downhill) from here. To get there, return to the street in front of the House of the Vettii. Walk downhill along Vicolo dei Vetti. Go one block, to where you dead-end at a T-intersection with Via della Fortuna. Go a few steps left and then right at the first corner. Continue down this gently curving road to #22.

The stubby stone towers are flour grinders. Grain was poured into the top and donkeys or slaves, treading in a circle, pushed wooden bars that turned the stones that ground the grain. The powdered grain dropped out the bottom as flour—flavored with tiny bits of rock. Nearby, the thing that looks like a modern-day pizza oven was...a brick oven. Each neighborhood had a bakery just like this.

• Continue down the curvy road to the next intersection. As you walk consider the destructive power of all the plants and vines that you see around. Also, notice the chariot grooves worn into the pavement. When the curvy road reaches the intersection with Via degli Augustali, turn left. Ahead, in 50 yards, at #44, is the Taberna Hedones, an ancient tavern with an original floor mosaic still intact. A few steps past that, turn right and walk downhill to #18—one of many Pompeii brothels.

You’ll find the biggest crowds in Pompeii at a place that was likely also quite popular 2,000 years ago—the brothel. Prostitutes were nicknamed lupe (she-wolves), alluding to the call they made when attracting business. The brothel was a simple place, with beds and pillows made of stone and then covered with mattresses. The ancient graffiti includes tallies and exotic names of the women, indicating the prostitutes came from all corners of the Mediterranean (it also served as feedback from satisfied customers). The faded frescoes above the cells may have been a kind of menu for services offered. Note the idealized women (white, which was considered beautiful; one wears an early bra) and the rougher men (dark, considered horny). The bed legs came with little disk-like barriers to keep critters from crawling up, the tiny rooms had curtains for doors, and the prostitutes provided sheepskin condoms.

• Leaving the brothel, go right, then take the first left, and continue going downhill two blocks to return to Via Abbondanza. This walk is over. The Forum—and exit—are to the right. If you exit now, you’ll be routed through the exhibition rooms—where you’ll find a scale model of the city, an interesting video, some artifacts—and the gift shop.

But before you leave, consider these extra stops—all worth the time and energy (if you have any left). To locate them, refer to your map.

This temple served Pompeii’s Egyptian community. The little white stucco shrine with the modern plastic roof housed holy water from the Nile. Isis, from Egyptian myth, was one of many foreign gods adopted by the eclectic Romans. Pompeii must have had a synagogue, too, but it has yet to be excavated.

Originally a Greek theater (Greeks built theirs with the help of a hillside), this was the birthplace of the Greek port here in 470 BC. During Roman times, the theater sat 5,000 people in three sets of seats, all with different prices: the five marble terraces up close (filled with romantic wooden seats for two), the main section, and the cheap nosebleed section (surviving only on the high end, near the trees). The square stones above the cheap seats once supported a canvas rooftop. The high-profile boxes, flanking the stage, were for guests of honor. From this perch, you can see the gladiator barracks—the colonnaded courtyard beyond the theater. They lived in tiny rooms, trained in the courtyard, and fought in the nearby amphitheater. Check out the adjacent and well-preserved smaller Teatro Piccolo.

Once owned by a wealthy Pompeiian, this house takes its current name from a fresco of the Greek playwright Menander on one of the walls. Admire the grand atrium (with frescoes depicting scenes from Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, and an altar to the family gods), the wall frescoes, and the mosaics. The cloister-like back courtyard leads to a room with skeletons (not plaster casts) of eruption victims from this house. Farther back, a passage leads to the servants’ quarters.

You’re at ground level—post eruption. To the right (inland), the farmland shows how locals lived on top of the ruins for centuries without knowing what was underneath. To the left, you can see the entire ancient city of Pompeii spread out in front of you and appreciate the magnitude of the excavations.

There’s no better reminder in Pompeii of the horror caused by a volcanic eruption (and how we all might act given the same circumstances) than this “garden.” Archaeologists identified this house as belonging to a middle-class merchant family. Plaster casts of this fleeing (“fugitive”) family are placed exactly as the bodies were found after the eruption: lined up in single file as they attempted to escape several cubic feet of already fallen ash. Their exit was stopped by a sudden wave of hot gas and volcanic material, likely traveling over 100 miles per hour. Frozen in time, servants cannot be distinguished from their masters.

If you can, climb to the upper level of the amphitheater (though the stairs are often blocked). With Vesuvius looming in the background, mentally replace the tourists below with gladiators and wild animals locked in combat. Walk along the top of the amphitheater and look down into the grassy rectangular area surrounded by columns. This is the Palaestra, an area once used for athletic training. (If you can’t get to the top of the amphitheater, you can see the Palaestra from outside—in fact, you can’t miss it, as it’s right next door.) Facing the other way, look for the bell tower that tops the roofline of the modern city of Pompei, where locals go about their daily lives in the shadow of the volcano, just as their ancestors did 2,000 years ago.

• If it’s too crowded to bear hiking back along uneven lanes to the entrance, you can slip out the site’s “back door,” which is next to the amphitheater. Exiting, turn right and follow the site’s wall all the way back to the entrance.

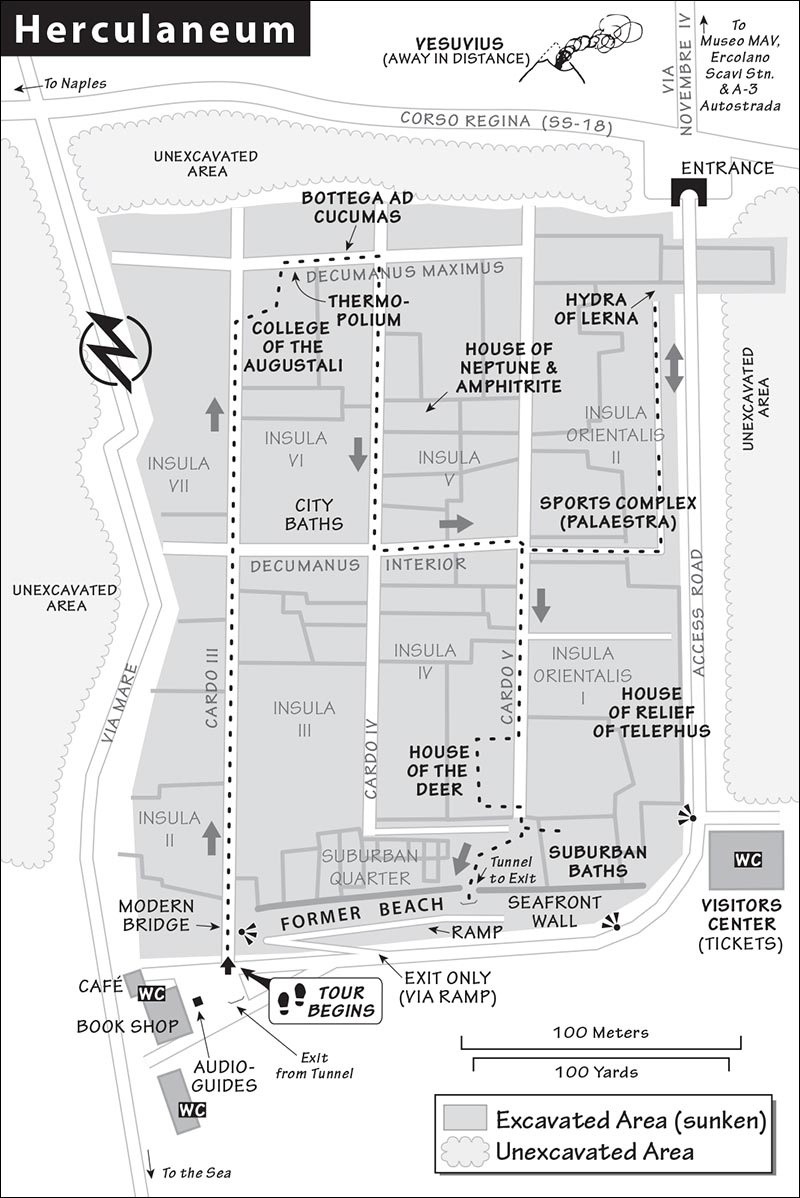

Smaller, less crowded, and not as ruined as its famous big sister, Herculaneum (worth ▲▲, Ercolano in Italian) offers a closer, more intimate peek into ancient Roman life but lacks the grandeur of Pompeii (there’s barely a colonnade).

Ercolano Scavi, the nearest train station to Herculaneum, is about 20 minutes from Naples and 50 minutes from Sorrento on the same Circumvesuviana train that goes to Pompeii (for details on the Circumvesuviana, see here). Walking from the Ercolano Scavi train station to the ruins takes 10 minutes: Leave the station and turn right, then left down the main drag; continue straight, eight blocks gradually downhill to the end of the road, where you’ll run right into the grand arch that marks the entrance to the ruins. (Skip Museo MAV.) Pass through the arch and continue 200 yards down the path—taking in the bird’s-eye first impression of the site to your right—to the ticket office in the modern building.

Cost: €12, free (and crowded) once or twice a month; the specific day varies in peak season (in low season, it’s the first Sun); covered by the Campania ArteCard (see here).

Hours: Daily April-Oct 8:30-19:30, Nov-March until 17:00, ticket office closes 1.5 hours earlier.

Information: Tel. 081-777-7008, http://ercolano.beniculturali.it [URL inactive].

Closures: Like Pompeii, various sections of Herculaneum can be closed unexpectedly.

Visitor Information: Pick up a free, detailed map and excellent booklet at the info desk next to the ticket window. The booklet gives you a quick explanation of each building. There’s a bookstore inside the site, next to the audioguide stand.

Tours: The audioguide basically recites the text in the free booklet (€8, €13 for 2, ID required, rent at kiosk near site entry).

Length of This Tour: Allow one hour.

Baggage Storage: Herculaneum is harder than Pompeii for those with luggage, but not impossible. Herculaneum’s train station has lots of stairs and no baggage storage, but you can roll wheeled luggage down to the ruins and store it for free in a locked area in the ticket office building (pick up bags at least 30 minutes prior to site closing). To get back to the station, consider splurging on a €5 taxi (ask the staff to call one for you).

Services: There’s a free WC in the ticket office building, and another near the site entry.

Eating: Vending machines and café tables are near the entry to the site. There are also several eateries on the way from the train station.

SELF-GUIDED TOUR

SELF-GUIDED TOURCaked and baked by the same AD 79 eruption that pummeled Pompeii (see sidebar on here), Herculaneum is a small community of intact buildings with plenty of surviving detail. While Pompeii was initially smothered in ash, Herculaneum was spared at first—due to the direction of the wind—but got slammed about 12 hours after the eruption started by a superheated avalanche of ash and hot gases roaring off the volcano. The city was eventually buried under nearly 60 feet of ash, which hardened into tuff, perfectly preserving the city until excavations began in 1748.

After leaving the ticket building, go through the turnstiles and walk the path below the site to the entrance. Look seaward and note where the shoreline is today; before the eruption, it was where you are standing, a quarter-mile inland. This gives you a sense of how much volcanic material piled up. The present-day city of Ercolano looms just above the ruins. The modern buildings don’t look much different from their ancient counterparts.

As you cross the modern bridge into the excavation site, look down into the moat-like ditch. On one side, you see Herculaneum’s seafront wall. On the other is the wall that you just walked on, a solidified ash layer from the volcano that shows how deeply the town was buried.

After crossing the bridge, stroll straight to the end of the street and find the College of the Augustali (Sede degli Augustali, #24). Decorated with frescoes of Hercules (for whom this city was named), it belonged to an association of freed slaves working together to climb their way up the ladder of Roman society. Here and farther on, look around doorways and ceilings to spot ancient wood charred by the pyroclastic flows. Most buildings were made of stone, with wooden floors and beams (which were preserved here by the ash but rarely survive at ancient sites).

Leave the building through the back and go to the right, down the lane. The adjacent thermopolium (#19) was the Roman equivalent of a lunch counter or fast-food joint, with giant jars for wine, oil, and snacks. Most of the buildings along here were shops, with apartments above.

A few steps on, the Bottega ad Cucumas wine shop (#14, on the right) still has charred remains of beams, and its drink list remains frescoed on the outside wall (under glass).

Take the next right, go halfway down the street, and on the left find the House of Neptune and Amphitrite (Casa di Nettuno e Anfitrite, #7). Outside, notice the intact upper floor and imagine it going even higher. Inside, you’ll see colorful mosaics and a unique “frame” made of shells.

Back outside, continue downhill to the intersection, then head left for a block and proceed straight across the street into the don’t-miss-it sports complex (palaestra; #4). First you’ll see a row of “marble” columns, which (look closer) are actually made of rounded bricks covered with a thick layer of plaster, shaped to look like carved marble. While important buildings in Rome had solid marble columns, these imitations are typical of ordinary buildings.

Continuing deeper into the complex, look for the hole in the hillside and walk through one of the triangular-shaped entrances to find the highlight: the Hydra of Lerna, a sculpted bronze fountain that features the seven-headed monster defeated by Hercules as one of his 12 labors. If this cavernous space is unlit, go to the second doorway on the left wall and press the light switch.

Return through the sports complex and turn downhill to the House of the Deer (Casa dei Cervi, #21). It’s named for the statues of deer being attacked by dogs in the garden courtyard (these are copies; the originals are in the Archaeological Museum in Naples). As you wander through the rooms, notice the colorfully frescoed walls. Ancient Herculaneum, like all Roman cities of that age, was filled with color, rather than the stark white we often imagine (even the statues were painted).

You can see more of these colors, this time bright orange, across the street in the House of Relief of Telephus (Casa del Rilievo del Telefo, #2).

Continue downhill through the archway. The Suburban Baths illustrate the city’s devastation (Terme Suburbane, #3; enter near the side of the statue on the terrace, sometimes closed). After you descend into the baths, look back at the steps. You’ll see the original wood charred in the disaster, protected by the wooden planks you just walked on. At the bottom of the stairs, in the waiting room to the right, notice where the floor collapsed under the sheer weight of the volcanic debris. (The sunken pavement reveals the baths’ heating system: hot air generated by wood-burning furnaces and circulated between the different levels of the floor.) A doorway in front of the stairs is still filled with solidified ash. Despite the damage, elements of refinement remain intact, such as the delicate stuccoes in the caldarium (hot bath).

Back outside, make your way down the steps to the sunken area just below. As you descend, you’re walking across what was formerly Herculaneum’s beach. Looking back, you’ll see arches that were part of boat storage areas. Archaeologists used to wonder why so few victims were found in Herculaneum. But during excavations in 1981, hundreds of skeletons were discovered here, between the wall of volcanic stone behind you and the city in front of you. Some of Herculaneum’s 4,000 citizens tried to escape by sea, but were overtaken by the pyroclastic flows.

Thankfully, your escape is easier. Either follow the sound of water and continue through the tunnel (you’ll climb up and pop out near the site entry), or, more scenically, backtrack and exit the same way you entered.

The 4,000-foot-high Vesuvius, mainland Europe’s only active volcano, has been sleeping restlessly since 1944. While Europe has other dangerous volcanoes, only Vesuvius sits in the middle of a three-million-person metropolitan area that would be impossible to evacuate quickly.

Many tourists don’t know that you can easily visit the summit. Up top, it’s desolate and lunar-like, and the rocks are newly born. Walk the entire accessible part of the crater lip for the most interesting views; the far end overlooks Pompeii. Be still. Listen to the wind and the occasional cascades of rocks tumbling into the crater. Any steam? Vesuvius could blow again. (Don’t worry—there’d likely be at least a few hours or days of warning.)

By Car or Taxi: Drivers take the exit Torre del Greco and follow the signs to Vesuvio. Just drive to the end of the road and pay to park. A taxi costs €90 round-trip from Naples, including a 2-hour wait; it’s about €70 from Pompeii.

By Private Bus from Pompeii: From near the Pompei Scavi train station on the Circumvesuviana line (just outside the main entrance to the Pompeii ruins), you have two bus services to choose from, each taking about three hours (40 minutes up, 40 minutes down, and about 1.5 hours at the summit).

The old-fashioned Vesuvius Trolley Tram (Tramvia del Vesuvio) uses the main road up (€25 round-trip plus €10 summit admission, 6/day, tickets sold at and tram departs from Pompei Scavi train station, tel. 081-777-6750, www.tramvianapoli.com).

Busvia del Vesuvio winds you up a bumpy back road to the crater rim (Via Boscotrecase) in a cross between a shuttle bus and a monster truck. The walk up to the rim at the end is about the same, but you approach it from the other direction. It’s a fun, more scenic way to go, but not for the easily queasy (€22 includes summit admission, hourly April-Oct Mon-Sat 9:00-15:00, until later June-Aug, buy tickets at “info point” at Pompei Scavi train station, tel. 0126-426-1213, www.busviadelvesuvio.com).

By Private Bus from Herculaneum: The quickest trip up is on the Vesuvio Express. These small buses leave from the Ercolano Scavi train station (on the Circumvesuviana line, where you get off for the Herculaneum ruins; €10 round-trip plus €10 summit admission, daily from 9:30, runs every 45 minutes based on demand, 20 minutes each way—about 2.5 hours total, office on square in front of train station, tel. 0414-525-1213, www.vesuvioexpress.it).

Cost and Hours: €10 covers national park entry and the park guide’s orientation; ticket office open daily July-Aug 9:00-18:00, April-June and Sept until 17:00, closes earlier off-season. Bad weather can occasionally close the trail.

Information: The ticket office is 200 yards downhill from the parking lot. Tel. 081-865-3911, www.vesuviopark.it (official site) or www.guidevesuvio.it (more helpful site run by guides).

When to Go: Early-morning visitors enjoy the freshest air and snare the best parking spots. The mountain is open all year, but spring and fall are the most comfortable times to visit. Yellow broom flowers blossom in May and June.

Bring sunscreen, water, a light jacket in summer, and a hat and warm coat in winter. By bus, taxi, or private car, you’ll reach the volcano crater up a good but windy road from Torre del Greco (between Herculaneum and Pompeii). As you drive up, you’ll pass the remnants of the pre-AD 79 mountain (on your left, now called Monte Somma) and lava flows from the most recent 1944 eruption. No matter how you travel up, you’ll land at the parking lot.

Backtrack 200 yards downhill to buy your ticket at the office. Use the pay WC, as there’s none at the summit. From the parking lot, it’s a moderately steep half-mile, 20-minute hike (with a 600-foot elevation gain) up a dirt access road to the top. Say “no thank you” to the gentleman passing out walking sticks in return for a tip—you don’t need one.

At the rim, a sweeping view of the Bay of Naples is on your right; on your left, fenced off, there’s a fearsome drop into the crater. Mountain guides orient you and then set you free.