Nikhil P. Joshi, David J. Adelstein, and Brian Burkey

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND RISK FACTORS

The overwhelming majority of head and neck cancers are squamous cell cancers (HNSCC). More than 500,000 cases of HNSCC are diagnosed worldwide, and 40,000 to 60,000 cases occur in the United States. HNSCC comprise approximately 3% to 5% of all new cancers and 2% of all cancer deaths in the United States. Most patients are older than 50 years, incidence increases with age, and the male-to-female ratio is 2:1 to 5:1. The age-adjusted incidence is higher among black men, and, stage-for-stage, survival among African Americans is lower overall than in whites. Death rates have been decreasing since at least 1975, with rates declining more rapidly in the past decade. Human papillomavirus (HPV)–related oropharyngeal cancer is a subset of head and neck cancers that is increasing in number and is associated with a better prognosis, in part due to better response to treatment. The most common sites of head and neck cancer are the oral cavity, pharynx, larynx, and hypopharynx in the United States. Nasal cavity, buccal, paranasal sinus cancers, salivary gland malignancies, and various sarcomas, lymphomas, and melanoma are less common. This chapter will limit its discussion to the more common tumors found in the head and neck region, namely squamous cell carcinomas and related histologies. Lymphomas, sarcomas, cutaneous malignancies including melanoma and thyroid gland cancer will not be discussed.

Common risk factors include tobacco (smoking tobacco and other forms) and alcohol intake. Heavy alcohol consumption increases the risk of developing squamous head and neck cancer 2- to 6-fold, whereas smoking increases the risk 5- to 25-fold, depending on gender, race, and the amount of smoking. Both factors together increase the risk 15- to 40-fold. Smokeless/chewing tobacco and snuff are associated with oral cavity cancers. Use of smokeless tobacco, or chewing betel with or without tobacco, and slaked lime (common in many parts of Asia and some parts of Africa), is associated with premalignant lesions and oral squamous cancers. Chronic dental irritation due to ill-fitting dentures, sharp teeth, or inflammatory lesions like oral lichen planus also predispose to oral cavity cancers.

Multifocal mucosal abnormalities have been described in patients with head and neck cancer (“field cancerization”). There is a 2% to 6% risk per year for a second head and neck, lung, or esophageal cancer in patients with a history of a tobacco-related cancer in this area. Those who continue to smoke have the highest risk. Second primary cancers represent a major risk factor for death among survivors of an initial squamous carcinoma of the head and neck.

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) has been detected in almost all nonkeratinizing and undifferentiated nasopharyngeal cancers in North America but less consistently in keratinizing squamous nasopharyngeal cancers. HPV infection is associated with up to 70% of cancers of the oropharynx (base of tongue and tonsil), and some squamous nasopharyngeal cancers. The incidence of HPV-related oropharyngeal cancers is increasing in several countries, and HPV positivity is more common in cancers of nonsmokers. Disorders of DNA repair (e.g., Fanconi anemia and dyskeratosis congenita) as well as organ transplantation with immunosuppression are also associated with increased risk of squamous head and neck cancer.

ANATOMY AND PATHOLOGY

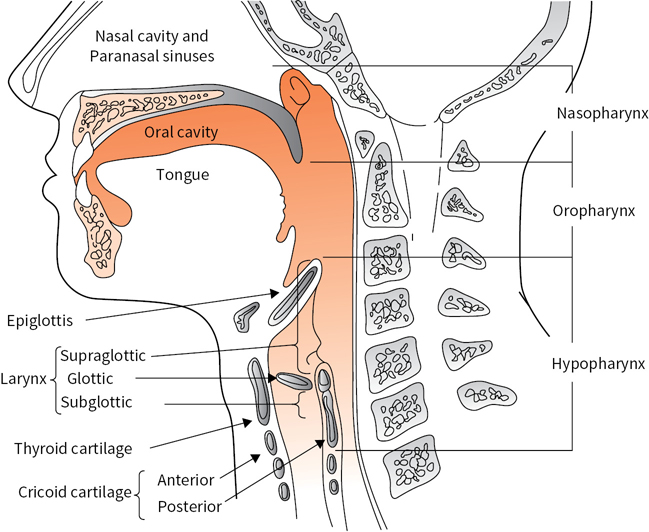

A simplified depiction of extracranial head and neck anatomy is presented in Figure 1.1. The major regions and subsites of the upper aerodigestive tract are divided into the nose and paranasal sinuses; nasopharynx (NP); oral cavity (OC; lips, gingiva, buccal areas, floor of mouth, hard palate, and tongue anterior to the circumvallate papillae); oropharynx (OP; soft palate, tonsils, base of tongue and lingual tonsils, and pharyngeal wall between palate and vallecula); hypopharynx (HP; posterior pharyngeal wall between vallecula and esophageal inlet, piriform sinuses, and postcricoid space); and larynx (supraglottis, glottis, and subglottis). The supraglottic larynx comprises the epiglottis, aryepiglottic folds, false vocal cords, and ventricles. The glottis comprises the true vocal cords, anterior commissure, and posterior commissure. The subglottis extends under the glottis to the cricoid cartilage and continues as the trachea.

FIGURE 1.1 Sagittal section of the upper aerodigestive tract. (Adapted from Oatis CA. Kinesiology: The Mechanics and Pathomechanics of Human Movement. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004.)

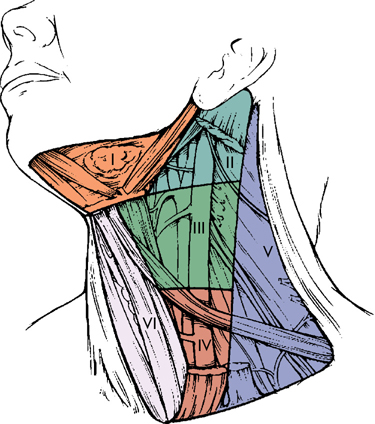

Knowledge of the lymphatic drainage of the neck assists in identification of the site of a primary tumor when a palpable lymph node is the initial presentation, and in staging metastatic spread, enabling the surgeon or radiation oncologist to plan appropriate treatment of both primary and neck disease. The patterns of lymphatic drainage divide the neck into several levels (Fig. 1.2): Level I includes the submental or submandibular nodes, which are most often involved with lesions of the oral cavity, nasal cavity, or submandibular salivary gland. Level II (upper jugular lymph nodes) extends from the skull base to the hyoid bone, and is frequently the site of metastatic presentation of naso- or oropharyngeal primaries. Level III (middle jugular lymph nodes between the hyoid bone and the lower border of the cricoid cartilage) and level IV (lower jugular lymph nodes between the cricoid cartilage and the clavicle) are most often involved by metastases from the hypopharynx, larynx, or above. Level V is the posterior triangle, including cervical nodes along cranial nerve XI, frequently involved along with level II sites in cancers of the naso- and oropharynx. Level VI is the anterior compartment from the hyoid bone to the suprasternal notch bounded on each side by the medial carotid sheath, and is an important region for the spread of laryngeal and thyroid carcinomas. Level VII is the area of the superior mediastinum, and mostly portends distant metastasis except for thyroid cancers.

FIGURE 1.2 Diagram of the neck showing levels of lymph nodes. Level I, submandibular; level II, high jugular; level III, midjugular; level IV, low jugular; level V, posterior triangle; level VI, tracheoesophageal; level VII, superior mediastinal, is not shown. (From Robbins KT, Samant S, Ronen O. Neck dissection. In: Flint PW, Haughey BH, Lund VJ, et al., eds. Cumming’s Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery. 5th ed. Copyright Elsevier, 2010. Used with permission.)

PRESENTATION, EVALUATION, DIAGNOSIS, AND STAGING

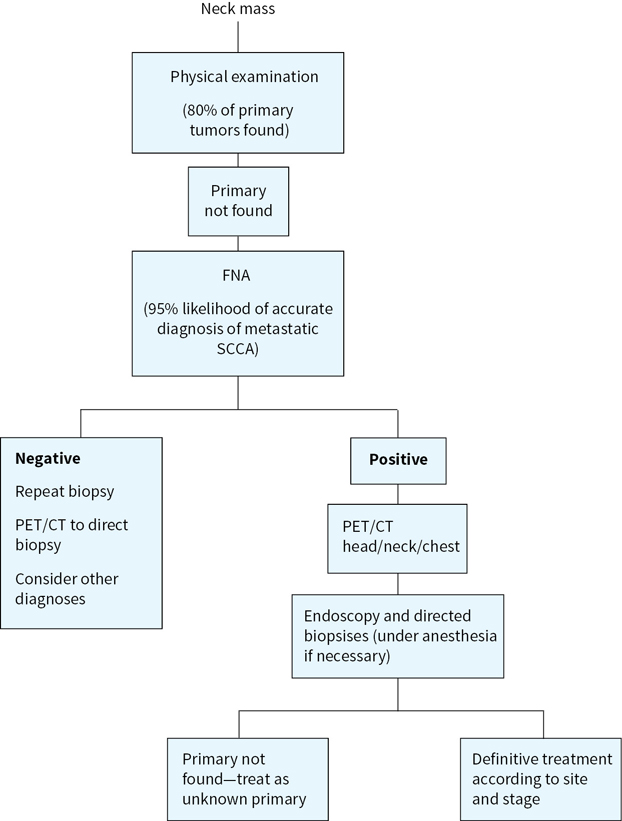

Signs and symptoms most often include pain and/or mass effects of tumor, involving adjacent structures, nerves, or regional lymph nodes (Table 1.1). This is common for oral cavity cancers. Adult patients with any of these symptoms for more than 2 weeks should be referred to an otolaryngologist. Delay in diagnosis is common due to patient delay, repeated courses of antibiotics for otitis media or sore throat, or lack of follow-up. A persistent lateralized symptom or firm cervical mass is highly suggestive of malignancy, and may represent a squamous cell carcinoma (Fig. 1.3). For nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal cancers, a common presenting symptom is a neck mass, often in a node in the jugulodigastric area and/or the posterior triangle. In advanced lesions, cranial nerve abnormalities may be present. Symptoms like hoarseness, hemoptysis, and odynophagia or dysphagia may indicate a laryngeal or hypopharyngeal primary. Distant metastases are uncommon at presentation, but may occur with nasopharyngeal, oropharyngeal, and hypopharyngeal cancers. The most common sites of distant metastases are lung and bone; liver and central nervous system involvement is less common.

TABLE 1.1 Common Presenting Signs and Symptoms of Head and Neck Cancer

Painless neck mass |

Odynophagia |

Dysphagia |

Hoarseness |

Hemoptysis |

Trismus |

Otalgia |

Otitis media |

Loose teeth |

Ill-fitting dentures |

Cranial nerve deficits |

Nonhealing oral ulcers |

Nasal bleeding |

FIGURE 1.3 Evaluation of cervical adenopathy when a primary cancer of the head and neck is suspected.

The history should include the following:

1.Signs and symptoms as listed in Table 1.1 and above

2.Tobacco exposure (pack-years; amount chewed; and duration of habit, current or former)

3.Alcohol exposure (number of drinks per day and duration of habit)

4.Other risk factors (chewing betel nut, chronic dental irritation, oral lichen planus, oral submucous fibrosis, leukoplakia, or erythroplakia)

5.Cancer history of patient and family; history of immunosuppression or congenital disorder

6.Thorough review of systems

The head and neck physical examination should include the following:

1.Careful inspection of the scalp, ears, nose, and mouth.

2.Palpation of the neck including the thyroid gland and oral cavity, assessment of tongue mobility, determination of restrictions in the ability to open the mouth (trismus), and bimanual palpation of the base of the tongue and floor of the mouth.

3.During examination of the nasal passages, NP, oropharynx, hypopharynx, and larynx, flexible endoscopes or mirrors as appropriate should be strongly considered for symptoms of hoarseness, sore throat, or enlarged lymph nodes not cured by a single course of antibiotics. When a neck mass with occult primary is the first presentation, the primary site can be located by clinical or flexible endoscopic examination in approximately 80% of cases.

4.Special attention to the examination of cranial nerves.

5.Look for possible skin cancers.

For abnormalities identified by history, physical examination, and/or endoscopy, the following evaluations should be performed. Superficial cutaneous or oral mucosal lesions, with irregular shape, erythema, induration, ulceration, and/or friability (easy bleeding) of greater than 2-week duration warrant biopsy, as these frequently are early indicators of severe dysplasia, carcinoma in situ, or invasive malignant process. For findings or lesions involving the nose, NP, oropharynx, hypopharynx and larynx, or neck with unknown primary, computed tomography (CT), and/or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with contrast should first be performed to identify origin, extent, and potential vascularity of lesions. Surgical biopsy of a neck mass before endoscopy is generally not advisable if a squamous cell carcinoma is suspected. Open biopsy may complicate regional control although an open biopsy may provide additional information to that obtained from fine needle aspiration (FNA) or a core needle biopsy. A direct laryngoscopy is still necessary for staging and treatment planning. Tissue diagnosis obtained by FNA biopsy of the node has a sensitivity and specificity approaching 99%. However, a nondiagnostic FNA or negative flexible endoscopy does not rule out the presence of tumor. Positron emission tomography (PET) scans combined with CT (PET/CT) or MRI can often localize smaller or submucosal primaries of the naso- and oropharynx that present with level II or V cervical adenopathy. Intraoperative endoscopic biopsy is then done with a secure airway under anesthesia. Bilateral tonsillectomy will sometimes reveal the source of an occult cancer, especially for HPV+ cancers. Esophagoscopy and bronchoscopy may be indicated for symptoms such as dysphagia, hoarseness, cough, or to search for occult primary. Transoral robotic surgery (TORS) can also be used to diagnose otherwise occult oropharyngeal cancers.

After a diagnosis of cancer is established, the patient should be staged using physical examination, endoscopic studies, and radiologic studies, which usually include CT scan and/or MRI of the primary tumor, neck, and chest. CT scan is considered the primary imaging study for evaluation of bone involvement, regional, mediastinal, and pulmonary metastasis. MRI may complement the CT scan with greater resolution of soft tissue for primary tumor staging, and evaluation of skull base and intracranial involvement. PET/CT scans are being used more frequently to detect tumors or nodes that are not obvious on other scans and for monitoring for disease recurrence in patients with advanced locoregional disease treated with concurrent chemotherapy and radiotherapy. PET/CT scanning is also indicated for staging patients with unknown primaries and for advanced head and neck cancers. A chest CT (or PET/CT) may also be useful for patients with locally advanced disease because of the risk of metastasis or a second lung malignancy.

Specialized tests include tissue p16 immunostaining for oropharyngeal cancers, and tissue Epstein-Barr encoded RNA (EBER) and plasma EBV DNA copy number for nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Laboratory tests typically obtained prior to initiating therapy include complete blood counts, renal and liver function tests, serum calcium and magnesium (if platinum-based chemotherapy is to be given), baseline thyroid function tests, and pregnancy testing in females of child-bearing age. Baseline and post treatment EBV DNA levels are recommended in EBV-related nasopharyngeal cancers.

Dental evaluation should be performed and any necessary extractions should be carried out at least 2 weeks prior to any planned radiation. Baseline speech, swallow, and audiometry evaluation may be indicated depending on the primary site involved and the treatment anticipated.

Clinical staging is based on physical and endoscopic examinations and imaging tests. The staging systems of the American Joint Committee for Cancer (AJCC) or the Union Internationale Contre le Cancer (UICC) (tumor, node, metastasis [TNM], stages I to IV) are used. The AJCC classification has further subdivided the most advanced disease stages into stage IVA (moderately advanced), stage IVB (very advanced), and stage IVC (distant metastatic).

The staging of primary tumors is different for each site within the head and neck, although some common themes exist. The AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, which entered its eighth edition in 2017, has made several significant changes in the previous T, N, and staging definition.

Below is a summary of the pertinent changes for head and neck cancer staging detailed in the AJCC eighth edition:

(1)Oral cavity cancer staging now reflects the depth of invasion as an important factor.

(2)p16-positive and p16-negative oropharynx cancers have separate staging systems for their T and N stage.

(3)The nodal staging for p16-positive oropharynx cancer is more akin to nasopharynx nodal staging; the stage grouping is different from other head and neck subsites as well.

(4)The tumor staging for nasopharynx cancer has been revised to more accurately reflect anatomic involvement.

(5)The nodal staging for nasopharynx cancer has been revised to reflect involvement above and below the cricoid cartilage; stage IVC has been eliminated.

(6)Nonoropharyngeal/nasopharyngeal cancer nodal staging has been revised to reflect the importance of extranodal extension (ENE)—clinical and pathologic nodal staging is different on the basis of node size and presence of ENE.

Discussion regarding staging in this chapter refers to the seventh edition of the AJCC staging manual. The eighth edition of the AJCC Staging Manual will be used to stage head and neck cancers starting January 2018 and should be consulted for details.

PRINCIPLES OF DISEASE MANAGEMENT AND GOALS OF THERAPY

Since head and neck cancer involves multiple individual sites of disease, it is useful to think of disease management principles according to the extent of disease. Certain common themes of management are evident as described below.

Early Disease (Usually Stages I, II, and Selected Stage III)

Early disease is optimally managed with single modality treatment. This could include surgery or radiation. The objective is to achieve high rates of locoregional control and cure while limiting morbidity of treatment and preserving functional outcomes. Organ conservation is central to management of early cancers. The choice of modality is dependent on how best these goals are achieved along with availability of expertise and patient choice.

Locoregionally Advanced Disease (Usually Stages III, IVA, IVB)

This is a heterogeneous group of patients spanning the spectrum of resectable and unresectable disease. Two or more treatment modalities are often combined to achieve optimal disease control. The primary modality of treatment depends on the site of disease. For example, while primary surgery is considered standard for oral cavity cases, radiation with chemotherapy might be considered for laryngeal cancer cases. Nasopharyngeal cases are treated with definitive chemoradiation in most cases. Trimodality treatment is necessary on occasion. Examples include surgery followed by adjuvant chemoradiation for locally advanced oral cavity cancers or surgical salvage after definitive chemoradiation for oropharynx/larynx/hypopharynx cancers. While organ preservation remains an important goal for larynx and hypopharynx cancers, disease control is the primary objective. Multimodality therapy including surgical resection is often required to reduce the risk of locoregional recurrence and/or distant metastases and improve survival when organ preservation is not possible.

Recurrent/Metastatic Disease (Stage IVC)

Recurrent and metastatic diseases often have equally poor prognoses. Exceptions may include “oligometastatic” disease, second cancers after a long disease-free interval and metastatic disease from HPV-associated oropharyngeal cancers. These categories may have a long natural history and a comparatively long disease course with therapy. Long term cures though uncommon are seen, especially with second cancers. This is discussed separately below. The large bulk of recurrent/metastatic cancers are best treated with palliative therapy. Palliative radiation, palliative chemotherapy, or a combination of the two is often used. Occasionally surgery might be used to debulk the cancer and offer quick relief of symptoms. A tracheostomy may be necessary for airway compromise and a feeding tube procedure may be required for alimentation. High-dose radiation with stereotactic techniques may be used to achieve durable palliation with lower toxicity rates. Early intervention with hospice care and palliative medicine may be appropriate during the course of disease.

PRINCIPLES OF SURGERY

Surgery plays a central role in the management of head and neck cancers. This includes management of the primary and the neck in most cases. For the primary cancer, surgical goals include resection of the tumor with an adequate margin (usually 0.5 cm microscopic margin) while preserving function (for early cancers), often with an en-block resection. Piece-meal resection is usually not favored. Exceptions include resection of sinus tumors via an endoscopic approach as opposed to an open surgical approach. The extent of primary oncologic cancer surgery depends on the subsite involved and is variably described as such. For example, oral tongue cancer surgery can span the spectrum of wide local excision to hemiglossectomy to total glossectomy depending on the extent of the disease. Early oropharynx and larynx cancers are amenable to transoral robotic resection or transoral microsurgery using laser. These modern procedures are far less morbid than open procedures like a transcervical approach or mandibular swing done in the past. On occasion however, an open procedure might be necessary and the morbidity of this approach has to be balanced against the alternative of nonoperative therapy. While transoral procedures are becoming more popular, appropriate case selection is crucial to optimize outcomes.

Management of the neck includes removal of all fibrofatty tissue in the neck levels at risk for disease spread for early disease or removal of all grossly involved nodes along with structures involved by the nodes for locoregionally advanced disease. The extent of neck dissection depends on the amount of neck disease. More aggressive neck dissections are needed for more extensive neck disease. For example, a selective neck dissection or modified radical neck dissection (type III) is adequate for elective nodal dissection/limited neck disease but a more extensive neck dissection might be needed if various structures in the neck are involved by disease (type I). A radical neck dissection might be needed in the salvage setting or if extensive neck disease is present, which involves the sternoclei-domastoid muscle (SCM) and/or internal jugular vein. On occasion, multimodality surgical expertise is needed—cardiovascular surgery for reconstructing the carotid and subclavian artery or neurosurgery to assist with skull base resections or intracranial disease.

Surgical resection, as described, inevitably results in tissue deficits, which can significantly affect function and cosmesis or both. This has led to a separate practice of surgery dedicated to reconstructive surgery. This entails various grafts involving the transfer of skin and muscle/bone to reconstruct or cover tissue defects. This is especially of value for salvage of recurrent disease after initial surgery or definitive radiation/chemoradiation. A detailed discussion is beyond the scope of this chapter, but suffice it to say that modern day head and neck surgery requires the ability to do elaborate reconstruction simultaneously with tumor extirpation.

PRINCIPLES OF RADIATION

Radiation, like surgery, also plays an important role in the treatment of HNSCC. It involves the precise delivery of radiation using x-rays or electrons to tumor targets while sparing as much normal tissue as reasonably possible. The intent of radiation therapy may be definitive (with or without concurrent chemotherapy), adjuvant after surgery (for microscopic disease), or palliative. Definitive doses of radiation (70 Gy equivalent) are generally used to treat gross disease, while lower doses (60 to 66 Gy equivalent) are used to treat microscopic disease in the postoperative setting. Certain recurrent cases may be treated with definitive reirradiation or with postoperative reirradiation. Reirradiation may be delivered once daily or twice daily as hyperfractionated radiation. Occasionally, induction radiation (with or without chemotherapy) may be used. In general, definitive doses of radiation are used for single modality treatment or when combined with chemotherapy for nonsurgical treatment of locally advanced disease. The dose is usually 70 Gy delivered at 2 Gy per fraction over 7 weeks. This is considered standard fractionation in the United States. However, other definitive dose fractionation schedules have been used around the world. Examples include 60 Gy in 25 fractions over 5 weeks, 64 Gy in 40 fractions over 4 weeks, and 55 Gy in 20 fractions over 4 weeks. Altered fractionation schemes include acceleration (same dose given over shorter periods of time), hyperfractionation (2 or more smaller fractions per day, higher total dose, and same overall treatment period), and hypofractionation (larger doses per fraction with a lower total dose). Hyperfractionation has shown an overall survival benefit and locoregional control benefit compared with standard fractionation. Toxicity profiles are different as well. In general, acute toxicities are worse but late toxicities are similar with hyperfractionation compared with standard fractionation. Adjuvant radiation after surgery is used to reduce the risk of locoregional recurrence. This is combined with chemotherapy for high-risk disease (positive margins or extracapsular nodal disease) based on a combined analysis of two studies (RTOG 9501 and EORTC 22931). The doses of adjuvant radiation are 60 to 66 Gy in 2 Gy fractions given over 6 to 6½ weeks. General indications for adjuvant radiation include T3, T4 disease, close margins (<0.5 cm), positive margins, lymphovascular space invasion, perineural disease, and node positive disease.

The technique of radiation delivery has improved dramatically over the years, and intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) is considered standard for HNSCC. This involves using multiple beams of radiation to target the disease with variable radiation beam intensity in order to optimally spare normal tissue. Many centers have graduated to volumetric modulated arc therapy (VMAT). This is a special form of IMRT using radiation arcs to generate more degrees of freedom and modulate the radiation intensity better. Moreover, this technique is now usually combined with image guidance (IGRT). This involves the use of daily cone-beam CT scanning while the patient is on the treatment machine to ensure precise and reproducible patient positioning, thereby reducing the amount of normal tissue in the radiation field.

Palliative radiation involves the delivery of a quick and limited volume of radiation often to the gross disease for rapid relief of symptoms. Different fractionation schemes include 20 Gy in 5 fractions, 30 Gy in 10 fractions, 8 Gy in one fraction, or 14 Gy in 4 fractions (2 fractions a day, 6 hours apart). The response is often short-lived but serves the goal for patients with 4 to 6 months life expectancy. Apart from HPV/EBV positive disease involving the oropharynx or nasopharynx, HNSCC remains a locoregionally recurrent problem. Recognition of this pattern of recurrence combined with the short-lived response to conventional palliative radiation has led to the development of stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT). SBRT is a high-precision radiation delivery technique used to deliver a very high-dose of radiation over a few treatments (usually 5) in the recurrent/metastatic disease setting. This technique is associated with durable response rates with acceptable morbidity and is favored when life expectancy is more than 6 months.

Proton therapy is a special form of radiation which enables the deposition of dose in the target while sparing the structures beyond the target. It is most often used for pediatric tumors, skull base tumors, and tumors close to optic structures and spinal cord, especially in the recurrent setting. Proton therapy is only recently being used for HNSCC and has yet to establish a role for routine cases. There remain several challenges with Proton therapy for HNSCC. Some of these are technique specific (range uncertainty, radiobiologic effectiveness values near the end of range, need for intensity modulation, lack of image guidance, etc.). Perhaps, the most important challenge remains the cost of proton therapy, which is several fold higher than standard photon therapy. More evidence for proton therapy in HNSCC is warranted before considering this therapy as a standard option especially when compared with techniques like VMAT IGRT using photons. Lastly, all these sophisticated techniques have a long learning curve, and there is evidence of better outcomes for patients treated at high-volume centers.

PRINCIPLES OF SYSTEMIC THERAPY

The use of systemic therapy in head and neck cancer is based on the assumption that squamous cell malignancies of the head and neck share a common sensitivity to chemotherapy. Thus most clinical trials of systemic chemotherapy have included patients with multiple and varied disease subsites. As for most solid tumors, initial exploration of the role of systemic chemotherapy began with the use of these agents as palliation for patients with recurrent or metastatic cancers deemed incurable by other treatment modalities. Despite the fact that these patients were often heavily pre-treated with surgery and radiation therapy, and often had a poor or suboptimal performance status, multiple single chemotherapeutic agents were found to have modest activity. Drugs such as methotrexate, bleomycin, fluorouracil, the platins (cisplatin and carboplatin), the taxanes (docetaxel and paclitaxel), and gemcitabine have all demonstrated modest efficacy as single agents prompting further study of their use in combination. The best studied of these combinations has been the fluorouracil and cisplatin regimen, which has produced consistent responses in approximately one third of patients with advanced disease. Other drug combinations have been similarly effective. Although these responses can have important palliative benefit, overall survival was not meaningfully impacted by this treatment.

The epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors, including both the monoclonal antibodies like cetuximab, and the tyrosine kinase inhibitors like gefitinib, erlotinib, and afatinib have resulted in very marginal response rates in recurrent disease patients progressing after conventional chemotherapy, although temporary disease stability has been frequently possible. When cetuximab was added to the fluorouracil and cisplatin (or carboplatin) combination, however, for the first time, a modest survival improvement was identified in the European EXTREME clinical trial reported in 2008.

Recent success using the immune checkpoint inhibitors in other diseases has led to their study in patients with recurrent head and neck cancer. Phase III data have now been generated demonstrating a survival benefit for the anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibodies when used after failure of first line platinum containing therapeutic regimens, and these drugs have now been approved for use in this setting. Although response rates are quite modest, the responses seen can be durable and active study of these agents is ongoing. Table 1.2 depicts selected chemotherapy regimens used for palliation.

TABLE 1.2 Selected Palliative Systemic Therapy Regimens for Metastatic Head and Neck Cancer

Regimens | Common Toxicities |

Cisplatin 100 mg/m2 IV (or Carboplatin AUC 5) on day 1 every 3 wk for six cycles plus 5-FU 1,000 mg/m2/day by continuous IV infusion on days 1–4 every 3 wk for six cycles plus cetuximab 400 mg/m2 IV loading dose on day 1, then 250 mg/m2 IV weekly (EXTREME regimen) | Nephrotoxicity, ototoxicity, myelosuppresion, mucositis, diarrhea, hand foot syndrome, allergic reaction, and acneiform rash |

Carboplatin AUC 6 IV on day 1 plus paclitaxel 175–200 mg/m2 IV on day 1 every 3 wk | Neuropathy, myelosuppresion, alopecia |

Methotrexate 40 mg/m2 IV weekly | Mucositis, myelosuppresion |

Docetaxel 30–40 mg/m2 weekly | Neuropathy, alopecia, diarrhea |

The activity of systemic chemotherapy in poor performance status patients with advanced disease suggested that there might be better ways to utilize this treatment modality. As for other malignancies, the previously untreated patients given systemic chemotherapy experience a considerably higher response rate than that seen in patients with recurrent tumors. In head and neck cancer, the fluorouracil and cisplatin combination results in only a 30% response rate in the previously treated recurrent disease patient, but has been reported to produce response rates of up to 90% in the previously untreated. When patients continue to receive multiple course of chemotherapy, however, they invariably progress, and single modality chemotherapy cannot be considered a curative treatment when given alone. The obvious suggestion, instead, would be to exploit this biologic activity as part of definitive management, rather than limiting its use to the recurrent and metastatic disease setting. This has led to a number of multimodality treatment schedules.

The first approach considered was the use of induction chemotherapy. This is based on the high response rates in previously untreated patients and the hope that tumor shrinkage induced by chemotherapy might result in more successful definitive locoregional management. Multiple phase II clinical trials of induction chemotherapy were successfully completed suggesting a high but transient response rate to systemic chemotherapy, with good tolerance of subsequent locoregional definitive management. Phase III trials, however, comparing induction followed by definitive radiation or surgery, to definitive treatment alone, were unsuccessful, and failed to produce any meaningful survival improvement. As such this treatment schedule has not been adopted.

The alternative of adding systemic chemotherapy after definitive surgery and/or radiation has also been tested. Phase III trials of this approach have similarly failed to demonstrate an improvement in overall survival. It should be noted however that with both the induction and the adjuvant schedules the use of systemic chemotherapy was successful in reducing the risk of distant metastatic disease. The lack of impact on overall survival likely reflected the limited importance of distant metastases in disease natural history.

It is only when the chemotherapy is given concurrently with radiation that any benefit can be consistently identified. Concurrent treatment appears to be effective due to the ability of chemotherapy to potentiate the impact of radiation, coupled with its demonstrated success in reducing the risk of distant micrometastatic disease. The approach has several potential disadvantages however, including the additive toxicity from the concurrent use of two treatment modalities, which then results in a tendency to compromise dose intensity of either radiation or chemotherapy. Nonetheless, phase III trials comparing concurrent chemotherapy and radiation with radiation alone have now reproducibly demonstrated a clear survival benefit for the concomitant regimens. The best studied of these concurrent regimens has employed high-dose single-agent cisplatin given every three weeks in conjunction with the radiation. Alternative single agent and multiagent concurrent chemoradiotherapy regimens have also proven successful, but have been less well studied. Meta-analysis data from more than 17,000 patients and 93 clinical trials have confirmed the lack of a survival benefit from either induction or adjuvant chemotherapy, compared to a clear improvement in survival when chemotherapy is used concurrently. As a result, this treatment approach has become the standard of care in the definitive nonsurgical management of patients with locoregionally advanced disease. Table 1.3 includes induction and concurrent chemotherapy regimens used most often.

TABLE 1.3 Concurrent and Induction Therapy Systemic Agents in Head and Neck Cancer

Regimens | Common Toxicities |

Concurrent: Cisplatin 100 mg/m2 IV every 21 days during radiation or cisplatin 40 mg/m2 every week | Nephrotoxicity, severe nausea/delayed vomiting, dehydration, mucositis, ototoxicity, neuropathy, myelosuppresion |

Concurrent: Carboplatin 70 mg/m2/day IV on days 1–4, 22–25, and 43–46 plus 5-FU 600 mg/m2/day by continuous IV infusion on days 1–4, 22–25, and 43–46 | Thrombocytopenia, mucositis, diarrhea, hand foot syndrome, neuropathy |

Concurrent: Cetuximab loading dose 400 mg/m2 IV followed by 250 mg/m2/week IV | Acneiform rash, mucositis, allergic reaction |

Induction: Docetaxel 75 mg/m2 IV day 1, Cisplatin 100 mg/m2 IV day 1, 5-FU 1,000 mg/m2 per day (continuous 24-hour infusion) for 4 days (Days 1–4) | Nephrotoxicity, severe nausea/delayed vomiting, dehydration, mucositis, ototoxicity, neuropathy, myelosuppresion, diarrhea |

Induction: Cisplatin 80–100 mg/m2 IV day 1, 5-FU 1,000 mg/m2 per day (continuous 24-hour infusion) for 4–5 days | Nephrotoxicity, severe nausea/delayed vomiting, dehydration, mucositis, ototoxicity, neuropathy, myelosuppresion, diarrhea |

The monoclonal anti-EGFR antibody cetuximab has also been studied in conjunction with radiation and compared to radiation therapy alone. Again, a survival benefit was demonstrated for the combination. This approach has thus become another potential treatment option for the nonoperative management of locoregionally advanced disease. It remains unknown however whether radiation and concurrent cetuximab is equivalent to radiation and concurrent chemotherapy. Clinical trials are addressing this question but the results are not yet available.

The marked improvement in locoregional control achieved with concurrent chemoradiotherapy has, not surprisingly, been accompanied by an increase in the relative frequency of distant metastatic disease. Given the reproducible benefit of induction chemotherapy on the incidence of distant metastases, the suggestion has emerged that the use of induction chemotherapy followed by concurrent chemoradiotherapy, or “sequential treatment” might further improve treatment results. In addition, the incorporation of a taxane into the fluorouracil and cisplatin induction combination has proven successful in increasing the response rates after induction chemotherapy suggesting additional potential benefit from a three-drug regimen in this sequential schedule. Although a theoretically attractive approach, this treatment paradigm is accompanied by an increase in treatment duration, an increase in treatment toxicity, and a significant increase in expense. To date, three phase III trials comparing concurrent chemoradiotherapy to sequential induction followed by concurrent chemoradiotherapy have been completed. None of these three trials have demonstrated a survival benefit for the sequential treatment, and all have resulted in increased toxicity. Thus the current standard of care for the nonoperative management of locoregionally advanced disease is the use of concurrent chemoradiotherapy, and the sequential treatment schedules have no defined role.

Many patients however will first undergo surgical resection but are then found to have pathologic features suggesting a high risk of disease recurrence. The standard approach for these high risk patients has been the use of postoperative adjuvant radiation. Two phase III cooperative group clinical trials from the RTOG and the EORTC have explored the role of postoperative radiation and concurrent high-dose cisplatin, compared to radiation alone in patients with high-risk features after surgical resection. These trials both reported a clear improvement in local disease control and disease-free survival in the concurrently treated patients. When an unplanned subgroup analysis was conducted of pooled data from both trials, it appeared that this benefit was limited to those patients with extracapsular nodal spread or margin positivity. As such, the use of concurrent high dose cisplatin with radiation has become a treatment standard for this subgroup of postoperative patients.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Oral Cavity

The oral cavity includes the lip, anterior two-thirds of the tongue, floor of the mouth, buccal mucosa, gingiva, hard palate, and retromolar trigone. Approximately 20,000 new cases are diagnosed annually in the United States. The epidemiology, natural history, common presenting symptoms, risk of nodal involvement, and prognosis for specific subsites are shown in Table 1.4

TABLE 1.4 Head and Neck Cancer: Oral Cavity

Site | Epidemiology | Natural History and Common Presenting Symptoms | Nodal Involvement |

Lip | Risk factors are sun exposure and tobacco; 3,600 new cases a year; 10–40 times more common in white men than in black men or women (black or white) | Exophytic mass or ulcerative lesion; more common in lower lip (92%); slow-growing tumors; pain and bleeding | 5%–10% Midline tumors spread bilaterally Level I more common (submandibular and submental); upper lip lesions metastasize earlier: Level I and also preauricular |

Alveolar ridge and retromolar trigone | 10% of all oral cancers; M:F, 4:1 | Exophytic mass or infiltrating tumor, may invade bone; bleeding, pain exacerbated by chewing, loose teeth, and ill-fitting dentures | 30% (70% if T4) Levels I and II more common |

Floor of mouth | 10%–15% of oral cancers, (occurrence 0.6/100,000); M:F, 3:1; median age, 60 y | Painful infiltrative lesions, may invade bone, muscles of floor of mouth and tongue | T1, 12%; T2, 30%; T3, 47%; and T4, 53% Levels I and II more common |

Hard palate | 0.4 cases/100,000 (5% of oral cavity); M:F, 8:1; 50% cases squamous, 50% salivary glands | Deeply infiltrating or superficially spreading pain | Less frequently: 6%–29% |

Buccal mucosa | 8% of oral cavity cancers in United States; women > men | Exophytic more often, silent presentation; pain, bleeding, difficulty in chewing, trismus | 10% at diagnosis |

M:F, male-to-female ratio.

Early oral cavity cancers are treated with surgery alone. This usually involves a wide local excision of the primary with surgical management of the neck. Elective nodal dissection is considered standard except for very small, superficial primaries (tumors less than 4 mm thick). Small primaries of the oral cavity resected with a wide margin, without adverse pathologic features and with negative nodes may be followed without adjuvant management. An alternative approach to manage the primary is with definitive radiation, usually using brachytherapy. This approach remains dependent on local practice patterns and availability of expertise and is generally not a standard of care in the United States.

Locoregionally advanced cases including T2 oral tongue cancers with more than 4 mm thickness are usually treated with wide local excision and neck dissection. The extent of primary site excision depends on the size of the primary and its extent. For example, an oral tongue resection might range from a wide local excision to a near total or total glossectomy. Similarly, the extent of neck dissection varies by the extent of disease in the neck. A recent phase III trial of elective nodal dissection versus therapeutic nodal dissection at relapse for early-stage lateralized oral squamous cell carcinoma has shown a survival advantage to elective nodal dissection. A selective neck dissection (levels I to IV) or modified radical neck dissection is done in most cases for node negative necks and those with minimal neck disease. Patients with more extensive neck disease and salvage cases may require a more extensive surgery like a radical neck dissection. Of late, sentinel lymph node biopsy is gaining popularity especially for oral cavity cancers. Head and neck cancers have complex lymph node drainage patterns, and oral tongue cancers have traditionally been known to drain directly to the lower neck while skipping intervening lymph nodal stations. Sentinel lymph node biopsy is not considered standard and is not recommended outside of a clinical trial. Tumor thickness, especially for oral tongue cancers, has traditionally been a prognostic factor for disease outcomes and also correlates with neck nodal disease. It is generally agreed that increasing thickness of the tumor correlates with outcome. The actual thickness however is variable across studies. Most cases require reconstruction with the help of a surgeon trained in head and neck reconstruction techniques. Definitive radiation or chemoradiation is an inferior alternative to initial surgical management of locally advanced oral cavity cancers and is not favored unless the patient is medically inoperable or unresectable.

Radiation plays an important role in the adjuvant management of locoregionally advanced oral cavity cancers and has been shown to improve locoregional control. Chemotherapy is generally added for positive margin or extracapsular extension of nodal disease. This approach has been shown to provide a locoregional control benefit over radiation alone. Several intermediate risk factors are recognized including close margins (<5 mm), lymphovascular space invasion, perineural invasion, T3/T4 disease, T2 oral cancer with >5 mm thickness of primary and node positive disease without extracapsular extension. Adjuvant radiation with cetuximab is being explored in a phase III trial to improve outcomes for intermediate risk disease where surgery and radiation remain the current standard but locoregional control still remains far from optimal. Similarly, even with adjuvant chemoradiation after surgery for high-risk disease (extracapsular extension from a node, positive margin), locoregional control and overall survival remain poor. RTOG 0234 was a phase II study exploring the safety and efficacy of docetaxel and cetuximab to further intensify treatment for high-risk disease. Encouraging results from this study have resulted in the ongoing RTOG 1216 study comparing radiation with cisplatin to radiation with docetaxel or radiation with docetaxel and cetuximab for the management of high-risk cancers.

Oropharynx

The oropharynx includes the base of the tongue, vallecula, tonsils, posterior pharyngeal wall, and the soft palate. The epidemiology, natural history, common presenting symptoms, and risk of nodal involvement are shown in Table 1.5.

TABLE 1.5 Head and Neck Cancer: Oropharynx

Site | Epidemiology | Natural History and Common Presenting Symptoms | Nodal Involvement |

Base of tongue | 4,000 new cases annually in the United States; M:F ratio, 3–5:1. May be HPV-associated | Advanced at presentation (silent location, aggressive behavior); pain, dysphagia, weight loss, and otalgia (from cranial nerve involvement); neck mass is a frequent presentation | All stages: 70% (T1) to 80% (T4) Levels II and III more commonly involved |

Tonsil, tonsillar pillar, and soft palate | Tobacco and alcohol; HPV common | Tonsillar fossa: more advanced at presentation: 75% stage III or IV, pain, dysphagia, weight loss, and neck mass Soft palate: more indolent, may present as erythroplakia | Tonsillar pillar T2, 38% Tonsillar fossa T2, 68% (55% present with N2 or N3 disease) |

Posterior pharyngeal wall | Advanced at diagnosis (silent location); pain, bleeding, and weight loss; neck mass is common initial symptom | Clinically palpable nodes T1, 25% T2, 30% T3, 66% T4, 75% Bilateral involvement is common |

Oropharyngeal cancers can be divided into two large prognostic groups by their etiology, namely HPV-induced or HPV-unrelated, usually tobacco-induced cancers and the most recent AJCC staging system now recognizes these as two different diseases with two separate staging systems. The overwhelming majority of oropharyngeal cancers are HPV positive in the western world. Positive immunohistochemistry for p16 is a surrogate for the presence of HPV as a causative factor. A large RTOG experience has validated the prognostic value of HPV and divided oropharyngeal cancers in low, intermediate, and high-risk groups. Data from the Princess Margaret Hospital in Canada have further categorized HPV positive disease into low- and high-risk groups. Age and smoking have stood out as prognostic factors as well. Based on these data, it is clear that the HPV positive disease has a far better prognosis than HPV negative tumors. Although, at present, treatment algorithms are the same for HPV-induced and carcinogen-induced oropharynx cancer, active investigation is currently underway in an effort to identify whether these treatments can be altered based on disease etiology.

Early stage oropharynx cancers are usually managed with single modality treatment, namely surgery or definitive radiation (T1/T2, N0/N1). Locoregional control and overall survival remain high for these stages. More locally advanced disease is traditionally managed with definitive chemoradiation or bioradiation (with cetuximab) with surgery reserved for salvage (especially for advanced neck disease). A select subset of patients can be managed with surgery followed by adjuvant treatment. Surgical options include transoral resection (less commonly open surgery) and appropriate neck dissection. Case selection is often tailored to achieve optimal outcomes and avoid multiple modalities of therapy thereby minimizing morbidity. For example, a T2N2bM0, tonsil primary amenable to TORS may undergo this procedure and neck dissection in the absence of clinical extracapsular extension of disease in the nodes, thereby avoiding the addition of concurrent chemotherapy with adjuvant radiation.

It must again be emphasized that the current standard of care treatment does not differ by HPV status. However, for low risk, HPV positive disease (T1-T3, N1-2b, </= 10 pack-years smoking history), locoregional control and distant control are excellent and have encouraged treatment de-escalation trials in order to maintain good outcomes and reduce the morbidity of treatment. This includes the recently concluded RTOG 1016 study comparing chemoradiation with cisplatin to bioradiation with cetuximab. Other studies like the ECOG 3311 are exploring the role of TORS to choose patients for radiation dose de-escalation while the HN 002 study is exploring the role of radiation dose de-escalation and elimination of chemotherapy. These and other studies being conducted will help to establish the role of treatment de-escalation for low risk HPV-related disease.

High risk HPV positive oropharyngeal cancer (T4, N2c-N3 disease) is still associated with a high locoregional control rate but distant failure occurs in up to a quarter of cases. Therefore, this group may not benefit from treatment de-escalation (particularly elimination of systemic therapy) and strategies to improve systemic control are warranted. High risk HPV negative cancer (T3, T4, N2c-N3 disease) is associated with equally poor distant failure. Locoregional control is also inferior with about 40% failure at 3 years. Fortunately, this group of patients is becoming less common. Aggressive therapy is warranted for these patients and usually takes the form of definitive chemoradiation followed by surgical salvage as needed.

Larynx

Laryngeal cancers can be supraglottic, glottic, and/or subglottic. The epidemiology, natural history, common presenting symptoms, risk of nodal involvement, and prognosis for specific subsites of the larynx are shown in Table 1.6.

TABLE 1.6 Head and Neck Cancer: Larynx

Site | Epidemiology | Natural History and Common Presenting Symptoms | Nodal Involvement |

Supraglottis | 35% of laryngeal cancers | Most arise in epiglottis; early lymph node involvement due to extensive lymphatic drainage; two-thirds of patients have nodal metastases at diagnosis | Overall rate: T1, 63%; T2, 70%; T3, 79%; T4, 73% Levels II, III, and IV more common |

Glottis | Most common laryngeal cancer | Most favorable prognosis; late lymph node involvement; usually well differentiated, but with infiltrative growth pattern; hoarseness is an early symptom; 70% have localized disease at diagnosis | Sparse lymphatic drainage, early lesions rarely metastasize to lymph nodes. Clinically positive: T1, T2 Levels II, III, and IV more common T3, T4, 20%–25% |

Subglottis | Rare, 1%–8% of laryngeal cancers | Poorly differentiated, infiltrative growth pattern unrestricted by tissue barriers; rarely causes hoarseness, may cause dyspnea from airway involvement; two-thirds of patients have metastatic disease at presentation | 20%–30% overall pretracheal and paratracheal nodes more commonly involved |

M:F, male-to-female ratio.

Larynx cancer mainly comprises cancers of the glottis and supraglottis and less commonly of the subglottis. This distinction is important considering the glottis is devoid of lymphatics while the supraglottis and subglottis are rich in lymphatics.

Early T1 glottic cancers can be managed with voice conserving transoral laryngeal microsurgery. The local control with this technique is excellent often with superior voice quality. In general, superficial lesions affecting one vocal cord and not extending to the anterior commissure are best treated with this technique. Local recurrences can be managed with further surgery so long as they are superficial. Deeply invasive lesions require more extensive surgery. While these lesions are technically resectable, more extensive surgery or multiple surgeries can lead to deterioration in the voice quality. Such procedures are thus avoided.

Definitive radiation is considered an alternative for early glottic cancers especially when the lesion is more extensive and not suitable for microsurgical excision. Voice quality is often superior with radiation but depends on the baseline voice quality. Early glottic cancers can be treated with definitive radiation with excellent outcomes. The radiation field is usually a small laryngeal parallel-opposed field. Mild hypofractionation to 2.25 Gy has shown improved local control versus 2 Gy fractions.

T1 cancers of the supraglottis can be treated with transoral voice preserving surgery. An open or endoscopic supraglottic laryngectomy is often done and some form of bilateral neck management is usually advocated given the high risk of lymph node spread. Definitive radiation is an alternative management option and usually includes both necks in the treatment field.

T2 tumors of the glottis and supraglottis can be managed with either surgery or definitive radiation. Various forms of voice preserving laryngectomy procedures are utilized based on the extent of the tumor. Some of these options include a supraglottic laryngectomy, supracricoid laryngectomy, and a vertical partial laryngectomy. Bilateral neck dissections are also advised for supraglottic disease. Alternatively the primary and both necks can be treated with definitive radiation. The dose is usually slightly higher than for T1 tumors. Though not a part of formal AJCC staging, T2 glottic cancers have been divided into T2a and T2b based on true vocal cord mobility restriction. T2b glottic cancers have a worse outcome with standard-dose radiation alone. It is believed that these cases represent early paraglottic space involvement, and these may require more intensive treatment. Hyperfractionation and chemoradiation are some strategies utilized to achieve better local control.

The management of T3N0M0 laryngeal cancer is controversial. In certain cases, a voice preserving surgical approach may be warranted. A fixed cord is usually a contraindication for such a procedure like a vertical partial laryngectomy. If no adverse postoperative pathologic factors are identified, the patient may be observed without further adjuvant treatment. Total laryngectomy is usually avoided but remains an oncologically acceptable option. Definitive chemoradiation remains an alternative voice preserving treatment strategy.

The management of locally advanced laryngeal cancer takes into account the baseline function of the larynx, baseline swallowing function, and disease extent. The standard surgical procedure remains a total laryngectomy with bilateral node dissection. This may be followed by adjuvant radiation or chemoradiation based on the pathologic risk factors. This surgical management approach is best used for patient with severely compromised laryngeal and/or swallowing function. Select cases might undergo a voice-preserving surgery for the primary with neck dissections followed by adjuvant treatment as indicated. Perioperative speech rehabilitation is critically important for patients with advanced laryngeal cancer who are undergoing total laryngectomy. Phonation options include tracheoesophageal puncture at the time of total laryngectomy, esophageal speech, or a mechanical electrolarynx. Most patients can obtain satisfactory communication through one of these techniques.

Nonetheless, because of the significant resulting functional compromise, a total laryngectomy is not a surgical procedure that is readily embraced by patients. Larynx-preserving, nonoperative approaches have emerged as reasonable options, and are most appropriate for those patients without significant pre-existing laryngeal and/or swallowing dysfunction. The nonoperative management of locally advanced larynx cancer with radiation/chemoradiation has evolved in a systematic fashion. The VA larynx study compared induction chemotherapy with cisplatin/5-FU followed by radiation with total laryngectomy followed by radiation for locally advanced larynx cancers. The rate of larynx preservation was 64% and overall survival was not compromised. The RTOG 91-11 study compared induction chemotherapy followed by radiation to either definitive concurrent chemoradiation or to radiation alone. Large volume T4 lesions (with destruction of larynx or massive extension of supraglottic laryngeal cancer to the base of tongue) were excluded as these are felt to be best treated with a primary surgical approach. The larynx preservation rate at 10 years was 82% for the concurrent chemoradiation arm and this approach has become a treatment standard in North America. Although the overall survival was statistically similar between all three treatment arms, likely reflecting the success of salvage surgery, a concerning trend toward an inferior survival was noted in the concurrent arm for reasons that are not entirely clear. As a result, induction chemotherapy followed by radiation, or even radiation alone remain acceptable treatment standards despite the reduced likelihood of larynx preservation.

Hypopharynx

The epidemiology, natural history, common presenting symptoms, risk of nodal involvement, and prognosis for specific subsites of the hypopharynx are shown in Table 1.7.

TABLE 1.7 Head and Neck Cancer: Hypopharynx, Nasal Cavity, Paranasal Sinuses, and Nasopharynx

Site | Epidemiology | Natural History and Common Presenting Symptoms | Nodal Involvement |

Hypopharynx | 2,500 new cases yearly in United States; etiology: tobacco, alcohol, and nutritional abnormalities | Aggressive, diffuse local spread, early lymph node involvement; occult metastases to thyroid and paratracheal node chain; pain, neck stiffness (retropharyngeal nodes), otalgia (cranial nerve X), irritation, and mucus retention 50% present as neck mass; high risk of distant metastases | Abundant lymphatic drainage Up to 60% have clinically positive lymph nodes at diagnosis |

Nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses | Rare 0.75/100,000 occurrence in United States Nasal cavity and maxillary sinus, four-fifths of all cases M:F, 2:1 Increased risk with exposure to furniture, shoe, textile industries; nickel, chromium, mustard gas, isopropyl alcohol, and radium | Nonhealing ulcer, occasional bleeding, unilateral nasal obstruction, dental pain, loose teeth, ill-fitting dentures, trismus, diplopia, proptosis, epiphora, anosmia, and headache, depending on the site of invasion Usually advanced at presentation | 10%–20% clinically positive nodes Levels I and II more common |

Nasopharynx | Rare (1/100,000) except in North Africa, Southeast Asia, and China, far northern hemisphere Associated with EBV, diet, genetic factors | Most common initial presentation: neck mass Other presentations: otitis media, nasal obstruction, tinnitus, pain, and cranial nerve involvement | Clinically positive: WHO I, 60% WHO II and III, 80%–90% |

M:F, male-to-female ratio; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus.

The large majority of hypopharynx cancers present at an advanced stage. The hypopharynx has a rich lymphatic network and nodal metastases are common at presentation. The retropharyngeal nodes may be involved as well. Early stage primary cancers may be addressed with transoral or open voice conserving procedures with neck dissections as indicated. Adjuvant therapy can then be administered if required.

The standard surgical approach for locally advanced hypopharynx cancer is a total laryngectomy with a partial pharyngectomy and bilateral node dissections. Microvascular free flap reconstruction of the surgical defect is common in the modern era. Adjuvant treatment is based on the adverse factors noted on pathology and usually includes adjuvant radiation. Similar to the trials conducted in larynx cancer, voice conserving nonoperative treatment has been studied for hypopharygeal cancers as well. The EORTC 24891 study compared induction cisplatin/5-FU followed by radiation with surgery followed by radiation. Larynx preservation at 5 years was 22% (in surviving patients). Overall survival was similar in both arms. Several recent retrospective institutional series have shown high larynx preservation rates (around 90% at 3 years) with better overall survival (around 50% at 3 years) with modern radiation/chemoradiation techniques. Overall, similar to larynx cancer, patients with significant laryngeal/swallowing dysfunction are best treated with initial surgery and adjuvant therapy. Patients with retained laryngeal and swallowing function may be best served by definitive nonoperative chemoradiation. General medical fitness for either approach is of paramount importance since these patients are often medically compromised.

Nasopharynx

The epidemiology, natural history, common presenting symptoms, risk of nodal involvement, and prognosis for nasopharyngeal cancer are shown in Table 1.7.

Nasopharyngeal cancers span a spectrum from more endemic EBV-associated undifferentiated carcinoma (WHO type III) to keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma (WHO type I). More recently, a p16-positive, EBV-negative subset has also been identified. The nasopharynx is very rich in lymphatics and nodal metastases are commonly found with nasopharyngeal cancer. The anatomy of the nasopharynx generally precludes a primary surgical approach especially since both necks are at risk from disease spread. As such, radiation plays a major role in the management of this cancer. Early node negative primaries of the nasopharynx are treated with radiation alone. This includes the primary and both necks. Appropriate elective skull base coverage is necessary. Locally advanced nasopharyngeal cancers are often treated with definitive chemoradiation followed by three cycles of adjuvant chemotherapy, based on the INT 0099 study, which demonstrated a large survival benefit with concurrent and adjuvant chemotherapy versus radiation alone. Despite several criticisms to this approach and the demographic differences noted with nasopharyngeal SCC in the west versus the east, this approach remains standard. The ongoing NRG HN 001 study is a randomized trial exploring the importance of this adjuvant chemotherapy based on clinical response and plasma EBV DNA levels. Patients with undetectable plasma EBV DNA after concurrent chemoradiation will be randomized to standard adjuvant CDDP/5-FU versus observation. Patients with detectable plasma EBV DNA after concurrent chemoradiation will be randomized to standard adjuvant CDDP/5-FU versus an alternative combination of paclitaxel/gemcitabine. Locally recurrent nasopharyngeal cancer that is nonmetastatic can be treated with surgical and nonsurgical approaches. Re-irradiation is usually advocated especially when the patient is not a surgical candidate.

Nasal Cavity and Paranasal Sinuses

The epidemiology, natural history, common presenting symptoms, risk of nodal involvement, and prognosis for carcinomas of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses are shown in Table 1.7. Nasal cavity and the paranasal sinus tumors comprise a broad variety of tumors. Some of these include squamous cell carcinomas, various types of adenocarcinomas, transitional cell carcinomas, minor salivary gland carcinomas, small cell carcinomas, esthesioneuroblastomas, and sinonasal undifferentiated carcinomas. Rare benign tumors like hemangiomas and angiofibromas may be seen.

There is no consensus on the management of these tumors. In general, these tumors are resected surgically, optimally using an endoscopic approach, or if necessary a combined open and endoscopic approach. Tumor resection often proceeds in a piecemeal rather than en-bloc fashion, and negative margins are often difficult to obtain. A combined team approach with neurosurgery may be needed especially for tumors involving the skull base. Certain cases where the tumor approaches the orbit might necessitate an orbital exenteration. Exceptions include radiosensitive and chemosensitive tumors like small cell carcinoma, which may be treated with definitive chemoradiation. Adjuvant radiation/chemoradiation usually follows surgical management. Locally advanced unresectable tumors may be treated with definitive chemoradiation provided the patient has adequate performance status and is medically fit to receive aggressive chemoradiation therapy. The remaining patients are best treated with palliative radiation and chemotherapy.

Salivary Glands

Salivary gland cancers are a rare subset of head and neck cancers. They comprise a variety of histologies and are found in various locations throughout the head and neck region, including the major and minor salivary glands. Salivary gland cancers may be both benign and malignant. Benign lesions are more commonly found in major salivary glands while lesions of the minor salivary glands are more likely to be malignant. Although the current pathologic classification of salivary gland cancers is currently under revision, the WHO 2005 system is still most commonly used. The benign salivary gland tumors are listed in Table 1.8.1 and malignant salivary gland tumors are listed in Table 1.8.2.

TABLE 1.8.1 Salivary Gland Benign Tumors

Pleomorphic adenoma (benign mixed tumor) |

Warthin tumor (papillary cystadenoma lymphomatosum) |

Monomorphic adenoma |

Benign lymphoepithelial lesion |

Oncocytoma |

Ductal papilloma |

Sebaceous lymphadenoma |

TABLE 1.8.2 Salivary Gland Malignant Tumors

Acinic cell carcinoma |

Mucoepidermoid carcinoma |

Adenoid cystic carcinoma |

Polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinoma |

Epithelial-myoepithelial carcinoma |

Basal cell adenocarcinoma |

Sebaceous carcinoma |

Papillary cystadenocarcinoma |

Mucinous adenocarcinoma |

Oncocytic carcinoma |

Salivary duct carcinoma |

Adenocarcinoma |

Myoepithelial carcinoma |

Carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma |

Squamous cell carcinoma |

Small cell carcinoma |

The clinical characteristics and prognosis of specific malignant salivary gland tumors are shown in Table 1.8.3.

TABLE 1.8.3 Selected Salivary Gland Malignant Tumors: Clinical Characteristics and Prognosis

Histology | Clinical Characteristics |

Mucoepidermoid carcinoma | Most common malignant tumor in major salivary glands; most common in parotid glands (32%) Low grade: local symptoms, long history, cure with aggressive resection; rarely metastasizes t(11;19)(q21;p13) in 50%–70% High grade: locally aggressive, invades nerves and vessels, and metastasizes early |

Adenocarcinoma | 16% of parotid and 9% of submandibular malignant tumors Grade correlates with survival |

Squamous cell carcinoma | Very rare Grade correlates with survival Squamous cell carcinoma of temple, auricular, and facial skin can metastasize to parotid nodes and can be confused with primary parotid tumor |

Acinic cell carcinoma | <10% of all salivary gland malignant tumors Low grade with slow growth, infrequent facial nerve involvement, infrequent and late metastases (lungs) Regional metastasis in 5%–10% of patients |

Adenoid cystic carcinoma | Most common malignant tumor in submandibular gland (41%), 11% of parotid gland High incidence of nerve invasion, which compromises local control t(6;9)(q22–23;p23–24) in 50% 40% of patients develop metastases; most common site of metastases is the lung. Patients may live many years with lung metastasis, but visceral or bone metastases indicate poor prognosis |

While major salivary gland cancers are clinically obvious as to site of origin, minor salivary gland tumors are often mistaken for more common mucosal lesions. Pretreatment imaging and tissue diagnosis are important for optimal management. Inadvertent partial excision of a lesion can compromise further oncological surgical excision. FNA biopsy is usually the first diagnostic step although definitive classification of salivary gland cancers can be difficult using this approach. Definitive surgical management is considered the standard initial treatment. In the absence of clear diagnosis, major salivary gland lesions are often resected with intraoperative frozen section for diagnosis. An oncological resection is attempted after establishing the diagnosis. Benign lesions like pleomorphic adenomas are also resected keeping oncological principles in mind (no tumor spillage) since these tumors show preponderance for local recurrence. Obviously malignant lesions (fast preoperative growth, facial nerve paralysis) are resected with a wide local margin. Negative resection margins are desired but may be difficult to obtain in proximity to the facial nerve. The facial nerve is usually preserved if it is functioning preoperatively and grossly uninvolved intraoperatively. A paralyzed facial nerve is sacrificed and an attempt is made to obtain a negative proximal margin. Meticulous skull base dissection may be required. The facial nerve should be reconstructed (grafted) during the primary surgery, and other adjunct procedures considered for facial reanimation, for example, temporalis tendon transfer. Management of the neck is controversial. In general, patients with T3/T4, high grade, or node positive diseases are usually managed with ipsilateral neck dissection.

The adjuvant management of salivary gland cancers is based on retrospective data. Adjuvant radiation appears to play an important role in improving locoregional control. General indications for postoperative radiation include T3/T4 primary lesions, high grade, lymphovascular space invasion, perineural invasion, close/positive margins, node positive disease, or recurrent disease. The principles of adjuvant radiation including doses required are similar to more common mucosal tumors discussed previously. Adjuvant radiation also plays a role in improving locoregional control for benign tumors like multiply recurrent pleomorphic adenomas. The role of chemotherapy is controversial and far less established for salivary gland tumors. The RTOG 1008 trial is a phase III trial exploring the role of concurrent cisplatin with radiation for high-risk salivary gland tumors. Some histologic subtypes may express potential hormonal or other therapeutic targets, such as HER2 and androgen receptors in salivary duct carcinomas. The role of targeted therapies for these diseases is being explored. Like other head and neck cancers, single modality adjuvant chemotherapy currently does not have a defined role in the current management of salivary gland cancers.

Unknown Primary of the Head and Neck

Unknown primary of the head and neck region comprises about 3% of all head and neck cancers. While squamous cell carcinomas are thought to originate from mucosal sites, other histologies are also seen and may indicate the source of their primary origin. For example, adenocarcinomas might arise from the salivary glands or the thyroid/parathyroid gland. The site of lymph node presentation is often linked to the potential site of the primary and this knowledge helps in evaluation and management. For example, a level III node might arise from the larynx, hypopharynx, or upper cervical esophagus. A level IA node is likely to arise from an oral cavity primary, while a level IB node might indicate a primary in the oral cavity, maxillary sinus, or nasal cavity. A level II node might indicate a primary in the oropharynx although several sites primarily drain to level II. A level V node raises the possibility of a nasopharynx or skin cancer. A parotid gland node usually indicates a cutaneous primary squamous cell carcinoma. An isolated supraclavicular node is very unlikely to indicate a head and neck primary. The primary in this case is almost always below the clavicle (lung, thoracic esophagus, breast, etc.). Evaluation follows the usual workup of head and neck cancers. A core needle biopsy of the node is preferred especially to obtain p16 and EBER evaluation, which may point to an HPV-related oropharyngeal primary or nasopharyngeal primary, respectively. However, caution is advised while doing so and the primary drainage pattern of the involved node should be taken into account before interpreting the immunohistochemistry results. For example, an isolated level V node might be p16+ but is more likely to indicate a cutaneous primary/nasopharynx primary rather an oropharyngeal primary. A PET CT should be considered before surgical diagnostic procedures are performed since this information might aid in finding the primary. A tonsillectomy, tongue base, and nasopharynx biopsy are considered standard although the yield is low for blind biopsies. Transoral lingual tonsillectomy (tongue base resection) is being increasingly utilized to detect a tongue base primary and is usually found in a high number of cases with a level II node presentation.

When no primary is found after surgical biopsies, management usually follows the purported site of the primary. For example, a level I node is subjected to a neck dissection assuming the oral cavity as the primary site. N1 disease may be resected and in the absence of adverse pathologic features, the patient may be observed without further treatment. This is based on the fact that data regarding emergence rates of the primary, although inconsistent in the literature, appear low. When radiation is used for treatment, however, it is considered standard to prophylactically radiate potential primary sites. For example, a p16+ level II node is treated with definitive neck radiation and prophylactic coverage of the oropharynx. A p16– level II node is treated similarly but prophylactic coverage often includes the nasopharynx and hypopharynx as well. An EBV+ node is treated along the lines of nasopharynx cancer. In general, the oral cavity, larynx, and hypopharynx are excluded in the prophylactic radiation volume since this approach is considered excessively morbid with low yield. More advanced disease may be treated with surgery followed by radiation with or without chemotherapy based on pathologic risk factors. When treating N2/N3 disease nonoperatively, concurrent chemotherapy is usually added to the radiation although the benefit of this is unclear. Salvage surgery may be needed for more advanced neck disease. Patients with distant metastases presenting with a neck node and no primary are treated with palliation (radiation and chemotherapy). The results of treatment usually follow similarly staged head and neck cancers with a known primary site. Therefore, in nonmetastatic cases, a cure is possible despite not knowing where the primary originated.

Recurrent Nonmetastatic Disease

Local recurrence is the most frequent pattern of disease failure in patients with locally advanced head and neck cancer. Distant failure however is being recognized more frequently, particularly in patients with HPV-induced oropharyngeal tumors. Locoregionally recurrent disease remains a major challenge in clinical oncology. These cancers could either be true recurrent disease or second primaries, a distinction that is often difficult, especially if disease is identified within 2 to 3 years of the primary disease. Management is based on the intent of treatment, which may be either palliative or definitive. Recurrent cancer within a short time span (usually 6 months), advanced age, poor performance status, and large burden of unresectable disease are factors associated with particularly poor outcomes and are best treated with palliative radiation and/or systemic palliative therapy. SBRT may be an option for some cases with an estimated survival of more than 6 months. This strategy is employed to quickly deliver reasonably durable palliative treatment with acceptable morbidity.

More favorable disease features include second primaries, or recurrent disease occurring more than 3 years after treatment of the initial tumor, young age, good performance status, low volume disease, resectable disease, and low morbidity from previous treatment. When possible, these patients should be treated with surgery followed by adjuvant chemoradiation. The GORTEC trial demonstrated a disease-free survival, but not overall survival advantage to adjuvant chemoradiation versus observation after surgery in this group of patients. The adjuvant radiation may be hyperfractionated or once daily radiation aimed at minimizing the side effects of therapy. The volume of radiation is usually minimized to include the recurrent disease bed while maximally sparing normal tissue thereby sparing morbidity. Case selection is crucial since the morbidity of this approach is not trivial. More modern and technologically advanced radiation delivery may offset the morbidity noted historically.

TOXICITY MANAGEMENT AND FOLLOW-UP

Acute Toxicities of Treatment

Patients treated with radiation therapy or concomitant chemoradiation therapy require frequent clinical assessment and prompt institution of supportive care to avoid severe or fatal consequences during the acute phase of treatment (during treatment and for the first several months after treatment).

Careful assessment of the need for a feeding tube should be done. In general, reactive feeding tube placement is preferred to prophylactic placement before therapy begins. These devices have been shown to be beneficial for patients who are thin, or have lost significant weight. They are not necessary for all patients, but if not placed, such patients must be assessed every 1 to 2 weeks for toxicity and weight loss.

Radiation and chemoradiation leads to increased fluid loss, especially with severe mucositis, and/or with loss of normal taste or appetite. Patients should be assessed every 1 to 2 weeks for skin turgor, orthostatic blood pressure changes, lightheadedness on standing, or renal dysfunction (especially when platinum-based chemotherapy is used).

A significant number of patients receiving chemoradiation therapy will develop severe mucositis that impairs nutrition and causes severe pain. Candida infection of the affected mucosal surfaces is fairly common. At the first sign of candidiasis, antifungal therapy should be instituted, topically and/or orally. A preparation containing an antifungal, anesthetic, and calcium carbonate suspension is useful. Narcotic pain control should be aggressive and patients should be taught to track pain severity and self-administer their narcotics before the peak of pain occurs. It is useful to use a transdermal administration route, using careful dose calculation based on the total use of short acting narcotic, plus a short-acting (liquid) narcotic to control pain.

Mild radiation dermatitis is managed with a moisturizer during and after radiation. Moist desquamation may be managed with vinegar soaks and saline dressings. These reactions will often heal after radiation is concluded. Superficial infections should be managed with antibiotics.