Megan Greally and Gregory D. Leonard

Worldwide, esophageal cancer is the eighth most commonly occurring cancer and the sixth most common cause of cancer-related mortality. Approximately 50% to 60% of patients present with incurable locally advanced or metastatic disease. Recent years have seen advances in the management of esophageal cancer resulting in meaningful improvements in outcomes.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

United States

Esophageal cancer occurs less frequently in the United States than in other geographic regions. It is estimated that there will be 16,910 cases and 15,690 deaths in 2016, 2.6% of all cancer deaths in the United States. The age-adjusted incidence from 2009 to 2013 was 4.3 per 100,000 per year. The median age at diagnosis is 67 years.

Esophageal cancer is approximately four times more common in men than women. The incidence is higher in lower socioeconomic groups and in urban areas, particularly in black men. Overall the incidence is similar among black people and white people. Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is more common in black people than adenocarcinoma (ADC). Incidence of ADC has increased significantly, and ADC now account for over half of all cases in Western countries. After a steep increase from 1973 to 2001, there has been a plateau in incidence in recent years. In contrast, rates for SCC have been decreasing because of reduced tobacco and alcohol consumption. Five-year relative survival rates were 5% from 1975 to 1977, 10% from 1987 to 1989, and 20% from 2005 to 2011.

Worldwide

About 80% of cases of esophageal cancer occur in less developed regions. The highest incidence occurs in Asia (Northern China, India, and Iran) followed by Southern and Eastern Africa. In the high risk areas of Asia, 90% of cases are SCC, which may be related to low intake of fruits and vegetables and drinking beverages at high temperatures.

ETIOLOGY

TABLE 4.1 Causes of Esophageal Adenocarcinoma and Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Adenocarcinoma | Squamous Cell Carcinoma |

Barrett’s esophagus | Tobacco smoking |

Induced by chronic GERD | Alcohol |

GERD | Achalasia |

Obesity | Plummer–Vinson syndrome |

Due to risk of GERD | Tylosis |

Smoking | Human papillomavirus (HPV) |

Celiac disease | |

Esophageal diverticula and webs | |

Dietary factors |

Recognized causes of esophageal cancer are described in Table 4.1 above. Smoking has a synergistic effect with alcohol consumption and together they are responsible for 90% of all SCC cases in Western countries. Barretts esophagus is the greatest risk factor for ADC. It increases the risk of ADC 30-fold over the general population. Management recommendations are as follows:

Nondysplastic Barrett’s esophagus: endoscopy every 3 to 5 years.

Nondysplastic Barrett’s esophagus: endoscopy every 3 to 5 years.

Low-grade dysplasia: endoscopic ablation or surveillance every 6 to 12 months.

Low-grade dysplasia: endoscopic ablation or surveillance every 6 to 12 months.

High-grade dysplasia: endoscopic eradication therapy (resection of visible irregularities followed by radiofrequency ablation) preferred over esophagectomy or intensive three monthly endoscopy.

High-grade dysplasia: endoscopic eradication therapy (resection of visible irregularities followed by radiofrequency ablation) preferred over esophagectomy or intensive three monthly endoscopy.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Both ADC and SCC have similar presentations. Early symptoms are subtle and nonspecific. Later symptoms are described in Table 4.2. Physical signs, usually only seen at late presentation, include Horner syndrome, left supraclavicular lymphadenopathy (Virchow’s node), hepatomegaly, and those related to a pleural effusion.

TABLE 4.2 Clinical Presentation of Esophageal Cancer

Local Tumor Effects | |

Dysphagia (solids then liquids) | Odynophagia |

Weight loss and anorexia | Regurgitation of undigested food |

Iron-deficiency anemia secondary to chronic gastrointestinal blood loss | |

Invasion of Surrounding Structures | |

Hoarseness secondary to recurrent laryngeal nerve involvement | |

Tracheo- or bronchio-esophageal fistula | Hiccups (phrenic nerve invasion) |

Distant Metastases | |

Cachexia | Pain |

Hypercalcemia | Dyspnoea/Jaundice/ascites (metastatic sites) |

DIAGNOSIS

Endoscopy is the gold standard investigation and allows for histological confirmation with biopsy. It has been shown that several biopsies improve diagnostic accuracy and six to eight biopsies are recommended to allow sufficient tissue for histological interpretation and yield a diagnostic accuracy close to 100%.

PATHOLOGY

The common histologic subtypes are ADC and SCC, which account for approximately 90% of esophageal cancers. Rarely, small cell carcinoma, melanoma, sarcoma, lymphoma, or carcinosarcoma may arise in the esophagus. Fifty percent of tumors arise in the lower one-third, 40% in the middle one-third, and 10% in the upper one-third of the esophagus. Most SCCs occur in the upper and mid esophagus while ADC generally arises in the distal esophagus and esophagogastric junction (EGJ). Metastases to locoregional lymph nodes occur early because the lymphatics are located in the lamina propria. Involvement of celiac and perihepatic nodes is more common in ADC due to distal tumor location.

STAGING

Adequate staging is required in order to determine the appropriate therapeutic approach. Patients should be assigned a clinical stage according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) classification. The advent of modern staging modalities has resulted in more accurate clinical TNM staging. The Siewert classification subclassifies EGJ tumors into three types according to their anatomic location and may be useful for selecting the surgical approach. Type I are distal esophagus tumors, type II are cardia tumors, and type III are subcardia gastric tumors.

Standard staging includes computed tomography (CT) and endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS). CT evaluates for the presence of metastatic disease, with an accuracy of over 90%, and for direct invasion of local structures, which may preclude surgical intervention. EUS allows assessment of the relationship of an esophageal mass to the five-layered esophageal wall and is superior to CT in evaluating the histologic depth of the tumor and determining nodal burden (accuracy of ~80% and 75%, respectively). EUS can facilitate fine-needle aspiration of suspicious lymph nodes to allow confirmation of disease involvement. The accuracy of EUS is operator dependent and interobserver variability is significant.

Positron emission tomography (PET)/CT is more sensitive than CT for detecting distant disease, and guidelines recommend its use in patients who are surgical candidates after routine staging. Several studies have suggested a change in management in up to 20% of patients with the use of PET/CT in preoperative assessment. The role of laparoscopy in outruling peritoneal disease is uncertain. It is an optional staging investigation for those with no evidence of distant metastatic disease who have distally located tumors.

TREATMENT

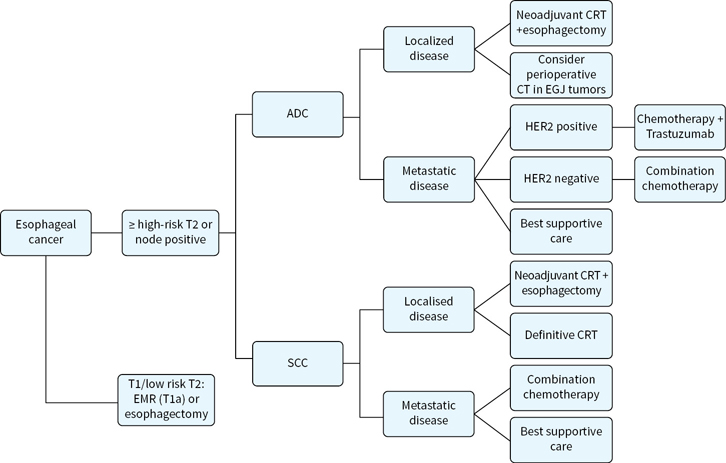

An overview of management strategies for localized and advanced disease is shown in Figure 4.1.

FIGURE 4.1 Algorithm for management of esophageal cancers, localized and metastatic.

Surgical Management

Esophageal cancer is confined to the esophagus in about 22% and regional nodal disease accounts for a further 30% of cases. Therefore, approximately 50% of patients are potential surgical candidates.

Esophageal cancer is confined to the esophagus in about 22% and regional nodal disease accounts for a further 30% of cases. Therefore, approximately 50% of patients are potential surgical candidates.

In recent years, the improved survival seen with combined modality treatment has meant that surgery alone is generally only considered for patients with T1-2N0M0 disease.

In recent years, the improved survival seen with combined modality treatment has meant that surgery alone is generally only considered for patients with T1-2N0M0 disease.

Endomucosal resection (EMR) is a treatment option for select patients with T1a disease as similar cure rates to esophagectomy have been reported in specialized centers. EMR is not recommended for T1b cancers as submucosal involvement is associated with a 30% rate of nodal metastases.

Endomucosal resection (EMR) is a treatment option for select patients with T1a disease as similar cure rates to esophagectomy have been reported in specialized centers. EMR is not recommended for T1b cancers as submucosal involvement is associated with a 30% rate of nodal metastases.

Advances in staging techniques and patient selection have improved surgical morbidity and mortality. Surgical expertise, multidisciplinary management, and audit of outcomes in high volume centers all contribute to operative mortality rates of less than 5%.

Advances in staging techniques and patient selection have improved surgical morbidity and mortality. Surgical expertise, multidisciplinary management, and audit of outcomes in high volume centers all contribute to operative mortality rates of less than 5%.

Surgical principles include a wide resection of the primary tumor and regional lymphadenectomy. Intraoperative frozen section can assess for the presence of residual disease, which may be R1 (microscopic tumor) or R2 (macroscopic tumor). The resection status is one of the strongest prognostic factors in esophageal cancer. The probability of achieving an R0 resection (no residual tumor) is associated with the depth of tumor infiltration into the esophageal wall.

Surgical principles include a wide resection of the primary tumor and regional lymphadenectomy. Intraoperative frozen section can assess for the presence of residual disease, which may be R1 (microscopic tumor) or R2 (macroscopic tumor). The resection status is one of the strongest prognostic factors in esophageal cancer. The probability of achieving an R0 resection (no residual tumor) is associated with the depth of tumor infiltration into the esophageal wall.

Definitive chemoradiotherapy (CRT) is favored for patients with cervical carcinoma of the esophagus (above the aortic arch) as they are usually not surgical candidates, and is standard in those with unresectable disease (T4 or extensive nodal burden) or poor performance status.

Definitive chemoradiotherapy (CRT) is favored for patients with cervical carcinoma of the esophagus (above the aortic arch) as they are usually not surgical candidates, and is standard in those with unresectable disease (T4 or extensive nodal burden) or poor performance status.

The transhiatal, transthoracic (Ivor-Lewis), and tri-incisional esophagectomy procedures are the usual approaches employed in the United States while esophagectomy with an extended (three-field) lymphadenectomy is commonly utilized in Asia.

The transhiatal, transthoracic (Ivor-Lewis), and tri-incisional esophagectomy procedures are the usual approaches employed in the United States while esophagectomy with an extended (three-field) lymphadenectomy is commonly utilized in Asia.

A total thoracic esophagectomy (TTE) is recommended for patients with thoracic esophageal cancer. This involves a cervical esophagogastrostomy, radical two-field lymph node dissection (mediastinum and upper abdomen nodes), and jejunostomy feeding.

A total thoracic esophagectomy (TTE) is recommended for patients with thoracic esophageal cancer. This involves a cervical esophagogastrostomy, radical two-field lymph node dissection (mediastinum and upper abdomen nodes), and jejunostomy feeding.

A tri-incisional approach involving laparotomy, thoracotomy and a left neck incision for cervical anastomosis is generally advocated over an Ivor-Lewis transthoracic procedure as tri-incisional surgery allows for more extensive proximal resection margins and a reduced risk of reflux.

A tri-incisional approach involving laparotomy, thoracotomy and a left neck incision for cervical anastomosis is generally advocated over an Ivor-Lewis transthoracic procedure as tri-incisional surgery allows for more extensive proximal resection margins and a reduced risk of reflux.

A transhiatal (TH) esophagectomy is utilized in patients with Siewert II and III EGJ tumors. This involves laparotomy and cervical esophagogastrostomy after resection of the distal esophagus and partial or extended gastrectomy with a two-field lymphadenectomy. TH esophagectomy can also be used for Siewert I EGJ tumors, but a TTE and partrial gastrectomy with two-field lymphadenectomy is an option based on a randomized study which showed a nonsignificant improvement in overall survival (OS) for this approach compared to TH esophagectomy.

A transhiatal (TH) esophagectomy is utilized in patients with Siewert II and III EGJ tumors. This involves laparotomy and cervical esophagogastrostomy after resection of the distal esophagus and partial or extended gastrectomy with a two-field lymphadenectomy. TH esophagectomy can also be used for Siewert I EGJ tumors, but a TTE and partrial gastrectomy with two-field lymphadenectomy is an option based on a randomized study which showed a nonsignificant improvement in overall survival (OS) for this approach compared to TH esophagectomy.

Minimally invasive laparoscopic and thoracoscopic techniques aim to reduce complication rates and enhance recovery times. One randomized trial showed a 3-fold decrease in postoperative pulmonary infection rate after minimally invasive surgery compared with open transthoracic surgery. This is significant as pulmonary complications, including pneumonia, are the most frequent complications following esophageal surgery. However, more data are required regarding this approach and open surgery remains standard of care.

Minimally invasive laparoscopic and thoracoscopic techniques aim to reduce complication rates and enhance recovery times. One randomized trial showed a 3-fold decrease in postoperative pulmonary infection rate after minimally invasive surgery compared with open transthoracic surgery. This is significant as pulmonary complications, including pneumonia, are the most frequent complications following esophageal surgery. However, more data are required regarding this approach and open surgery remains standard of care.

The minimum number of lymph nodes that should be removed has not been established. Some data suggest that a more extensive lymphadenectomy is associated with a better survival. Three-field lymphadenectomy is standard for proximal tumors in Asia but it is unclear if this approach improves outcomes and it is associated with increased toxicity.

The minimum number of lymph nodes that should be removed has not been established. Some data suggest that a more extensive lymphadenectomy is associated with a better survival. Three-field lymphadenectomy is standard for proximal tumors in Asia but it is unclear if this approach improves outcomes and it is associated with increased toxicity.

Chemoradiotherapy

Neoadjuvant (Trimodality Approach)

In patients with locally advanced disease (T3-4, N0-3), preoperative therapy is standard. With surgery alone, an R0 resection is not possible in about 30% to 50% and long-term survival rarely exceeds 20%. Preoperative CRT has been shown to result in higher rates of complete resection, better local control, and OS.

Several randomised trials have evaluated preoperative CRT versus surgery alone. Neoadjuvant CRT is standard for T3 and resectable T4 esophageal cancers based on two of these studies demonstrating a statistically significant OS benefit for CRT. Three studies did not show a benefit, however, two of these were underpowered and debate continues regarding their interpretation. The two most important studies are the CROSS and CALGB 9781 studies:

CALGB 9781 was a randomized Intergroup trial of trimodality therapy versus surgery alone in 56 patients (42 ADC, 14 SCC) with stage I–III esophageal cancer. Five-year OS was 39% versus 16% in favor of trimodality therapy but this did not reach statistical significance. A pathological complete response (pCR) was achieved in 40% of assessable patients in the trimodality arm, and there was no increase in perioperative mortality.

CALGB 9781 was a randomized Intergroup trial of trimodality therapy versus surgery alone in 56 patients (42 ADC, 14 SCC) with stage I–III esophageal cancer. Five-year OS was 39% versus 16% in favor of trimodality therapy but this did not reach statistical significance. A pathological complete response (pCR) was achieved in 40% of assessable patients in the trimodality arm, and there was no increase in perioperative mortality.

The CROSS trial included 363 patients, a majority (75%) had ADC, over 80% had T3/4 tumors, and over 60% were node positive. Preoperative radiation, at a dose of 41.4 Gy, concurrent with carboplatin and paclitaxel weekly for 5 weeks was compared to surgery alone. A significant 5-year OS advantage of 47% versus 33% in favor of the CRT arm was observed, HR 0.67. The benefit appeared greater in patients with SCC. There was also a higher rate of R0 resections (92% vs. 69%) and a 29% complete response rate observed with the use of CRT. Treatment was well tolerated and there was no increased postoperative mortality associated with the use of CRT.

The CROSS trial included 363 patients, a majority (75%) had ADC, over 80% had T3/4 tumors, and over 60% were node positive. Preoperative radiation, at a dose of 41.4 Gy, concurrent with carboplatin and paclitaxel weekly for 5 weeks was compared to surgery alone. A significant 5-year OS advantage of 47% versus 33% in favor of the CRT arm was observed, HR 0.67. The benefit appeared greater in patients with SCC. There was also a higher rate of R0 resections (92% vs. 69%) and a 29% complete response rate observed with the use of CRT. Treatment was well tolerated and there was no increased postoperative mortality associated with the use of CRT.

A meta-analyses in 2011 reported a benefit for trimodality therapy over surgery alone. This included 12 randomized trials of concurrent or sequential neoadjuvant CRT versus surgery alone. The above studies were included. There was an absolute OS benefit of 8.7% at 2 years and benefit was observed across histologic subtypes.

Management of patients with clinical T2N0 disease is less well defined. These patients were included in three trials including the CROSS trial that showed survival benefit for neoadjuvant CRT but currently there is no clear consensus as to the best approach. An RTOG phase III study is currently ongoing evaluating the addition of trastuzumab to trimodality therapy in patients with HER2 positive disease based on the survival advantage seen in the ToGA trial in patients with advanced disease.

Neoadjuvant CRT has been compared with neoadjuvant chemotherapy in three trials, which reported similar results. There was no difference in OS between groups but higher rates of pathologic complete response and R0 resections were observed in the CRT groups in all three studies. Of note, two of these trials were underpowered to show a survival advantage.

Definitive Chemoradiotherapy in Resectable Disease

Direct comparisons of CRT versus surgery in resectable esophageal cancer are limited. Definitive CRT is reasonable in patients who are not surgical candidates and in those with SCC and an endoscopic complete response. The benefit of nonoperative management (avoidance of morbidity and mortality) must be weighed against the lower rates of local control. Patients with ADC have lower rates of pCR after CRT and there is limited data on nonsurgical management in this group. Some retrospective studies have reported inferior survival with a nonsurgical approach and it is recommended that definitive CRT is reserved for ADC patients with major operative risk.

Two randomized trials have compared CRT with CRT followed by surgery and have provided evidence to support a nonsurgical approach in select patients. Despite better local control neither showed improved survival with trimodality therapy. The patient populations were predominantly SCC.

A German study evaluated 172 patients with locally advanced resectable SCC. Patients received three cycles of induction 5-FU, leucovorin, etoposide, and cisplatin followed by concurrent CRT (cisplatin/etoposide with 40 Gy radiotherapy) and patients with at least a partial response were randomized to continued CRT (chemotherapy with 20 Gy radiotherapy) or surgery. There was an improvement in local control rates with surgery (64% vs. 41% at 2 years), but no difference in OS, and early mortality was less in the CRT arm (12.8% vs. 3.5%; P = 0.03).

A German study evaluated 172 patients with locally advanced resectable SCC. Patients received three cycles of induction 5-FU, leucovorin, etoposide, and cisplatin followed by concurrent CRT (cisplatin/etoposide with 40 Gy radiotherapy) and patients with at least a partial response were randomized to continued CRT (chemotherapy with 20 Gy radiotherapy) or surgery. There was an improvement in local control rates with surgery (64% vs. 41% at 2 years), but no difference in OS, and early mortality was less in the CRT arm (12.8% vs. 3.5%; P = 0.03).

FFCD 9102 randomized 444 patients with T3, N0-1, M0 disease to definitive CRT with cisplatin and 5-FU or CRT (lower dose of radiation) and surgery (patients with at least a partial response were randomly assigned to continue CRT or undergo surgery). The majority (89%) had SCC. There was no significant difference in 2-year OS (34% vs. 40% for surgery and CRT, respectively) between the groups. Surgically resected patients had lower rates of local recurrence and were less likely to require palliative procedures.

FFCD 9102 randomized 444 patients with T3, N0-1, M0 disease to definitive CRT with cisplatin and 5-FU or CRT (lower dose of radiation) and surgery (patients with at least a partial response were randomly assigned to continue CRT or undergo surgery). The majority (89%) had SCC. There was no significant difference in 2-year OS (34% vs. 40% for surgery and CRT, respectively) between the groups. Surgically resected patients had lower rates of local recurrence and were less likely to require palliative procedures.

A Cochrane analysis published in 2016 explored this question further, including these two trials, two others comparing CRT alone versus surgery alone and one comparing CRT with surgery and chemotherapy. Again, most patients had SCC. There was no difference in long-term mortality in the CRT group compared with the surgery group (HR 0.88; 95% CI, 0.76 to 1.03). However, the evidence was considered low-quality and included trials had a high risk of bias.

A Cochrane analysis published in 2016 explored this question further, including these two trials, two others comparing CRT alone versus surgery alone and one comparing CRT with surgery and chemotherapy. Again, most patients had SCC. There was no difference in long-term mortality in the CRT group compared with the surgery group (HR 0.88; 95% CI, 0.76 to 1.03). However, the evidence was considered low-quality and included trials had a high risk of bias.

Experienced multidisciplinary teamwork is required for appropriate use of definitive CRT and decision making around surgery versus CRT should be taken together with the informed patient.

Definitive Chemoradiotherapy in Inoperable Disease

Locally advanced unresectable esophageal cancer is generally incurable but combined modality therapy does offer a small chance of lasting disease control and long-term survival as well as improving quality of life through relief of dysphagia.

The optimal combination, doses and schedule of drugs, that should be used during CRT is not definitively established. Based on the RTOG 85-01 study, cisplatin and 5-FU with radiotherapy is recommended for patients with SCC. This study demonstrated an OS advantage (14 vs. 9 months median survival and 27% vs. 0% 5-year survival) in favor of CRT over radiotherapy alone. The majority of patients had SCC but eligibility for this study did not require surgical unresectability and patients with T4 disease and high nodal burden were not included. Therefore, this cohort likely represents a prognostically more favorable population. A number of randomized trials of CRT versus radiotherapy alone have failed to duplicate these results; however, a Cochrane review has confirmed the superiority of CRT over radiotherapy in patients with a good performance status. Combination cisplatin/5-FU is associated with significant toxicity and weekly carboplatin plus paclitaxel and oxaliplatin/5-FU based chemotherapy have been shown in phase II and phase III trials, respectively, to be appropriate alternative options.

There are few data available on the use of postoperative CRT in esophageal cancer. It is generally recommended in patients with resected node-positive or T3-4 disease who did not undergo preoperative therapy.

An influential Intergroup trial compared postoperative CRT with 5-FU/calcium leucovorin, to surgery alone in resected stage ≥ IB esophagogastric (20% of patients) and gastric ADC. The 3-year OS (50% vs. 41%) was significantly better with CRT. While EGJ tumors are usually treated with neoadjuvant therapy, postoperative CRT remains a standard option based on this data when required. However, there may be significant toxicity associated with this approach.

An influential Intergroup trial compared postoperative CRT with 5-FU/calcium leucovorin, to surgery alone in resected stage ≥ IB esophagogastric (20% of patients) and gastric ADC. The 3-year OS (50% vs. 41%) was significantly better with CRT. While EGJ tumors are usually treated with neoadjuvant therapy, postoperative CRT remains a standard option based on this data when required. However, there may be significant toxicity associated with this approach.

The CALGB 80101 investigated the use of more intensive chemotherapy (ECF) given before and after the INT-0116 protocol regimen, but found no improvement in survival compared with the 5-FU regimen used in the Intergroup trial.

The CALGB 80101 investigated the use of more intensive chemotherapy (ECF) given before and after the INT-0116 protocol regimen, but found no improvement in survival compared with the 5-FU regimen used in the Intergroup trial.

The CRITICS trial compared postoperative epirubicin, cisplatin/oxaliplatin and capecitabine (ECC or EOC) to postoperative cisplatin/capecitabine-based CRT in patients with gastric ADCs. Patients received three cycles of preoperative ECC or EOC. In a preliminary report at the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) 2016 meeting there was no significant difference in 5-year OS (40.8% vs. 40.9%). Seventeen percent of patients had EGJ tumors.

The CRITICS trial compared postoperative epirubicin, cisplatin/oxaliplatin and capecitabine (ECC or EOC) to postoperative cisplatin/capecitabine-based CRT in patients with gastric ADCs. Patients received three cycles of preoperative ECC or EOC. In a preliminary report at the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) 2016 meeting there was no significant difference in 5-year OS (40.8% vs. 40.9%). Seventeen percent of patients had EGJ tumors.

Only one half to two thirds of patients in INT-0116 and CRITICS completed planned postoperative therapy, providing further rationale for the use of preoperative therapy in this patient group.

Only one half to two thirds of patients in INT-0116 and CRITICS completed planned postoperative therapy, providing further rationale for the use of preoperative therapy in this patient group.

Chemotherapy

Neoadjuvant and Perioperative Chemotherapy

Several trials have evaluated the benefit of preoperative and perioperative chemotherapy with the rational that haematogenous relapses remain a significant issue and early systemic therapy might eradicate micrometastatic disease. To date, trials have focused on distal esophagus and EGJ disease and mixed results have been observed:

INT-0113 randomized 440 patients to preoperative chemotherapy with three cycles of cisplatin and 5-FU or immediate surgery. There was no significant difference in survival in either the overall population or between the SCC and ADC groups.

INT-0113 randomized 440 patients to preoperative chemotherapy with three cycles of cisplatin and 5-FU or immediate surgery. There was no significant difference in survival in either the overall population or between the SCC and ADC groups.

The Medical Research Council (MRC) OE2 trial of surgery with or without preoperative cisplatin/5-FU demonstrated a survival benefit for this approach.

The Medical Research Council (MRC) OE2 trial of surgery with or without preoperative cisplatin/5-FU demonstrated a survival benefit for this approach.

MRC MAGIC evaluated perioperative ECF versus surgery alone in gastric and EGJ ADC. Of 503 patients, 15% and 11% had EGJ and lower esophageal tumors, respectively. Patients who received chemotherapy in addition to surgery had better 5-year OS (23% vs. 36%). Only 42% of patients completed all planned treatment, again highlighting the difficulty administering postoperative therapy.

MRC MAGIC evaluated perioperative ECF versus surgery alone in gastric and EGJ ADC. Of 503 patients, 15% and 11% had EGJ and lower esophageal tumors, respectively. Patients who received chemotherapy in addition to surgery had better 5-year OS (23% vs. 36%). Only 42% of patients completed all planned treatment, again highlighting the difficulty administering postoperative therapy.

Preliminary results of the MRC OEO5 study were presented at the ASCO 2015 annual meeting. This study examined the optimal duration of preoperative chemotherapy and compared four cycles of epirubicin, cisplatin, and capecitabine (ECX) to two cycles of cisplatin/5-FU, both followed by surgery, in patients with T3N0-1 lower esophageal and EGJ ADC. There was no significant difference in disease-free survival (DFS) or OS despite use of ECX being associated with higher R0 resection and pCR rates. There was less toxicity associated with CF but surgical morbidity was similar between the groups.

Preliminary results of the MRC OEO5 study were presented at the ASCO 2015 annual meeting. This study examined the optimal duration of preoperative chemotherapy and compared four cycles of epirubicin, cisplatin, and capecitabine (ECX) to two cycles of cisplatin/5-FU, both followed by surgery, in patients with T3N0-1 lower esophageal and EGJ ADC. There was no significant difference in disease-free survival (DFS) or OS despite use of ECX being associated with higher R0 resection and pCR rates. There was less toxicity associated with CF but surgical morbidity was similar between the groups.

The FLOT trial composed the combination of docetaxel, oxaliplatin and fluorouracil to a “MAGIC” regimen and improved the median survival from 35 months to 50 months. This is likely to be a new standard of case.

The FLOT trial composed the combination of docetaxel, oxaliplatin and fluorouracil to a “MAGIC” regimen and improved the median survival from 35 months to 50 months. This is likely to be a new standard of case.

A 2015 meta-analysis that included nine randomized comparisons of preoperative chemotherapy versus surgery alone for esophageal or EGJ cancers showed a survival benefit for neoadjuvant chemotherapy with a hazard ratio of 0.88. No significant difference in the rate of R0 resections or risk of distant recurrence was observed.

A 2015 meta-analysis that included nine randomized comparisons of preoperative chemotherapy versus surgery alone for esophageal or EGJ cancers showed a survival benefit for neoadjuvant chemotherapy with a hazard ratio of 0.88. No significant difference in the rate of R0 resections or risk of distant recurrence was observed.

With the above data in mind, perioperative chemotherapy is considered a rational approach in patients unable to tolerate trimodality therapy.

In patients who have not received preoperative chemotherapy or CRT, postoperative chemotherapy may be beneficial but data is limited. One study evaluating adjuvant chemotherapy have been completed in Asian patients. The JCOG 9204 is a Japanese trial that compared surgery alone to surgery followed by two cycles of cisplatin and 5-FU in 242 patients with esophageal SCC. The 5-year DFS was significantly better with chemotherapy (55% vs. 45%) but there was no significant difference in OS (61% vs. 52%). The JCOG 9907 study showed superiority of neoadjuvant cisplatin/5-FU over adjuvant cisplatin/5-FU. With regards to EGJ ADC, data for the use of adjuvant chemotherapy may be extrapolated from gastric cancer where a benefit has been seen. For example, one such trial, the CLASSIC trial demonstrated a benefit for postoperative capecitabine/oxaliplatin in gastric cancer and a small proportion of EGJ tumors were included (2.3%).

Palliative Therapy

The goals of therapy in the metastatic setting include improvement in disease-related symptoms and quality of life as well as prolongation of survival. When deciding on the most appropriate treatment strategy, performance status, histologic subtype, symptom burden, and patient preference should be considered.

There is limited data for chemotherapy in the setting of advanced disease and most evidence is extrapolated from gastric cancer trials that include EGJ tumors. In the first instance therefore, clinical trial enrolment should be considered as there remains a lack of consensus as to the best regimen in the first line setting. Combination chemotherapy regimens provide higher response rates, in the range of 25% to 45% versus 15% to 25% for single agent therapies, but this has been shown to translate into only limited improvements in duration of disease control and survival. Patients with ADC should have their tumors evaluated for HER2 overexpression using immmunohistochemical (IHC) or fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis. Approximately 7% to 22% of EGJ adenocarcinomas overexpress HER2.

There are a number of first-line chemotherapy options:

Cisplatin and 5-FU (CF) is a well-established regimen although, despite higher response rates, the combination did not show a statistically significant survival benefit over cisplatin alone in a randomized trial of patients with advanced esophageal SCC.

Cisplatin and 5-FU (CF) is a well-established regimen although, despite higher response rates, the combination did not show a statistically significant survival benefit over cisplatin alone in a randomized trial of patients with advanced esophageal SCC.

5-FU/calcium leucovorin with either oxaliplatin or irinotecan (FOLFOX or FOLFIRI) has shown equivalence to cisplatin and 5-FU in advanced EGJ studies and is potentially less toxic.

5-FU/calcium leucovorin with either oxaliplatin or irinotecan (FOLFOX or FOLFIRI) has shown equivalence to cisplatin and 5-FU in advanced EGJ studies and is potentially less toxic.

Docetaxel, cisplatin, and 5-FU (DCF) have been compared to CF and demonstrated an improvement in response rates (37% vs. 25%), time to progression (5.6 vs. 3.7 months) and 2-year OS (18% vs. 9%). However, DCF was associated with significant toxicity in this study and doses have been modified in other trials evaluating this regimen.

Docetaxel, cisplatin, and 5-FU (DCF) have been compared to CF and demonstrated an improvement in response rates (37% vs. 25%), time to progression (5.6 vs. 3.7 months) and 2-year OS (18% vs. 9%). However, DCF was associated with significant toxicity in this study and doses have been modified in other trials evaluating this regimen.

The REAL-2 trial published in 2008 was a landmark trial, which evaluated oxaliplatin and capecitabine as alternatives to cisplatin and 5-FU. It randomized 1,002 patients to ECF, ECX (epirubicin/cisplatin/capecitabine), EOF (epirubicin/oxaliplatin/5-fluorouracil), or EOX (epirubicin/oxaliplatin/capecitabine). The median survival was 9.9, 9.9, 9.3, and 11.2 months, respectively. As OS was highest with EOX (P = 0.02) EOX subsequently became a standard of care in the first-line setting in many institutions.

The REAL-2 trial published in 2008 was a landmark trial, which evaluated oxaliplatin and capecitabine as alternatives to cisplatin and 5-FU. It randomized 1,002 patients to ECF, ECX (epirubicin/cisplatin/capecitabine), EOF (epirubicin/oxaliplatin/5-fluorouracil), or EOX (epirubicin/oxaliplatin/capecitabine). The median survival was 9.9, 9.9, 9.3, and 11.2 months, respectively. As OS was highest with EOX (P = 0.02) EOX subsequently became a standard of care in the first-line setting in many institutions.

Increasingly, in many institutions, doublet regimens are preferred over triplet regimens as the latter are not felt to offer a significant advantage and result in more toxicity.

Increasingly, in many institutions, doublet regimens are preferred over triplet regimens as the latter are not felt to offer a significant advantage and result in more toxicity.

S1 in combination with cisplatin or docetaxel showed superiority compared to S1 in Asian studies. The FLAGS study was subsequently conducted in a global population and showed equivalence of cisplatin/S1 and cisplatin/5-FU in the first-line setting. Cisplatin/S1 was associated with a favorable toxicity profile.

S1 in combination with cisplatin or docetaxel showed superiority compared to S1 in Asian studies. The FLAGS study was subsequently conducted in a global population and showed equivalence of cisplatin/S1 and cisplatin/5-FU in the first-line setting. Cisplatin/S1 was associated with a favorable toxicity profile.

In elderly patients and those with poor performance status single agent chemotherapy with 5-FU/leucovorin, capecitabine, weekly taxanes, or irinotecan is appropriate.

In elderly patients and those with poor performance status single agent chemotherapy with 5-FU/leucovorin, capecitabine, weekly taxanes, or irinotecan is appropriate.

Targeted therapies have been evaluated in the first-line setting:

The addition of Trastuzumab to combination chemotherapy is recommended in patients with HER2 positive esophageal ADC. The ToGA trial demonstrated an improvement in response rate (47% vs. 35%) and OS (13.8 vs. 11.1 months) for patients treated with trastuzumab in combination with cisplatin/5-FU compared with cisplatin/5-FU alone. In a post-hoc subgroup analysis, patients whose tumors were IHC 2+ and FISH positive or IHC 3+ benefitted substantially from addition of Trastzumab with an OS benefit of 16 versus 11 months, HR 0.65. In contrast, patients whose tumors were IHC 0/1+ and FISH positive did not demonstrate a significant improvement in OS (10 vs. 8.7 months; HR 1.07). National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines (www.nccn.org) suggest that Trastuzumab can be used with most active first-line regimens except those containing anthracyclines.

The addition of Trastuzumab to combination chemotherapy is recommended in patients with HER2 positive esophageal ADC. The ToGA trial demonstrated an improvement in response rate (47% vs. 35%) and OS (13.8 vs. 11.1 months) for patients treated with trastuzumab in combination with cisplatin/5-FU compared with cisplatin/5-FU alone. In a post-hoc subgroup analysis, patients whose tumors were IHC 2+ and FISH positive or IHC 3+ benefitted substantially from addition of Trastzumab with an OS benefit of 16 versus 11 months, HR 0.65. In contrast, patients whose tumors were IHC 0/1+ and FISH positive did not demonstrate a significant improvement in OS (10 vs. 8.7 months; HR 1.07). National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines (www.nccn.org) suggest that Trastuzumab can be used with most active first-line regimens except those containing anthracyclines.

Other anti-HER2 agents have also been evaluated. The LOGiC study assessed the addition of lapatinib to first-line chemotherapy (capecitabine/oxaliplatin) and found no benefit while the JACOB study evaluating addition of Pertuzumab to first-line chemotherapy (cisplatin/5-FU) with Trastuzumab and also showed no benefit.

Other anti-HER2 agents have also been evaluated. The LOGiC study assessed the addition of lapatinib to first-line chemotherapy (capecitabine/oxaliplatin) and found no benefit while the JACOB study evaluating addition of Pertuzumab to first-line chemotherapy (cisplatin/5-FU) with Trastuzumab and also showed no benefit.

The benefit of bevacizumab in combination with capecitabine and cisplatin in EGJ ADC in the first-line treatment was evaluated in the phase III AVAGAST trial and found no improvement in OS (12.1 vs. 10.1 months) despite improvements in response rates and progression free survival. Subgroup analysis suggests a potential benefit for patients in the Americas and while biomarkers may prove useful in identifying patients who might gain from addition of Bevacizumab to standard therapy, its role remains poorly defined.

The benefit of bevacizumab in combination with capecitabine and cisplatin in EGJ ADC in the first-line treatment was evaluated in the phase III AVAGAST trial and found no improvement in OS (12.1 vs. 10.1 months) despite improvements in response rates and progression free survival. Subgroup analysis suggests a potential benefit for patients in the Americas and while biomarkers may prove useful in identifying patients who might gain from addition of Bevacizumab to standard therapy, its role remains poorly defined.

EGFR is expressed in the majority of esophageal SCC but addition of Panitumumab or Cetuximab to chemotherapy in the first-line setting showed no benefit in two phase III trials.

EGFR is expressed in the majority of esophageal SCC but addition of Panitumumab or Cetuximab to chemotherapy in the first-line setting showed no benefit in two phase III trials.

Decision-making around second-line therapy upon progression should also take performance status, patient preference, and histological subtype into account and clinical trials should be considered where available.

Phase III data has shown benefit for docetaxel, irinotecan, or weekly paclitaxel with or without ramicirumab. Best supportive care is recommended for patients with poor performance status or significant comorbidities.

Phase III data has shown benefit for docetaxel, irinotecan, or weekly paclitaxel with or without ramicirumab. Best supportive care is recommended for patients with poor performance status or significant comorbidities.

Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 (VEGFR-2) was evaluated as a therapeutic target in the second-line setting in the REGARD and RAINBOW phase III trials. REGARD demonstrated a modest but significant OS benefit with the use of the VEGFR-2 inhibitor ramucirumab compared to placebo after progression on first-line therapy and RAINBOW reported an improvement in OS with the addition of ramucirumab to weekly paclitaxel.

Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 (VEGFR-2) was evaluated as a therapeutic target in the second-line setting in the REGARD and RAINBOW phase III trials. REGARD demonstrated a modest but significant OS benefit with the use of the VEGFR-2 inhibitor ramucirumab compared to placebo after progression on first-line therapy and RAINBOW reported an improvement in OS with the addition of ramucirumab to weekly paclitaxel.

Anti-HER2 therapy has also been evaluated in the second-line setting. Lapatinib did not show benefit when added to a taxane in the TyTAN study and T-DM1 demonstrated no benefit when compared to a taxane in the GATSBY study.

Anti-HER2 therapy has also been evaluated in the second-line setting. Lapatinib did not show benefit when added to a taxane in the TyTAN study and T-DM1 demonstrated no benefit when compared to a taxane in the GATSBY study.

In the third-line setting, apatinib was shown to modestly improve OS when compared to placebo in a Chinese population and regorafenib has demonstrated modest activity in the second- and third-line settings in a randomized phase II study. However, neither of these agents is considered standard.

Finally, immunotherapy is also being evaluated in esophageal cancer. KEYNOTE-059 demonstrated the benefit of pembrolizumab in third line and was given FDA approval for this indication.

Nivolumab showed a similar benefit over placebo in an Asian study published in the Lancent in 2017. Studies are also ongoing evaluating the role for immunotherapy in early-stage disease.

Radiotherapy alone may be used in the palliative setting for control of dysphagia. Endoscopic laser or balloon dilatation or stenting are alternative options and placement of a gastrostomy or jejunostomy may improve a patient’s nutritional status.

Surveillance of Patients with Locoregional Disease

The majority of recurrences develop within one year and over 90% develop within 2 to 3 years.

Isolated local recurrences occur more frequently after definitive CRT where salvage surgery may have a role and more vigilant surveillance is recommended in the first 2 years.

There is currently no data that demonstrate improved survival from earlier detection of recurrences or to guide the optimal surveillance strategy. The European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO) guidelines suggest surveillance with clinical review and multidisciplinary input, however, NCCN do advocate imaging and endoscopy in selected patients.

Suggested Readings

1.Ajani JA, Rodriguez W, Bodoky G, et al. Multicenter phase III comparison of cisplatin/S-1 with cisplatin/infusional fluorouracil in advanced gastric or gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma study: the FLAGS trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1547–1553.

2.Al-Batran SE, Homann N, Schmalenberg H, et al. Perioperative chemotherapy with docetaxel, oxaliplatin, and fluorouracil/leucovorin (FLOT) versus epirubicin, cisplatin, and fluorouracil or capecitabine (ECF/ECX) for resectable gastric or gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) adenocarcinoma (FLOT4-AIO): A multicenter, randomized phase 3 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(15_suppl):Abstract 4004.

3.Alderson D, Langley RE, Nankivell MG, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy for resectable oesophageal and junctional adenocarcinoma: results from the UK Medical Research Council randomised OEO5 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(suppl):Abstract 4002.

4.Allum WH, Stenning SP, Bancewicz J, et al. Long-term results of a randomized trial of surgery with or without preoperative chemotherapy in esophageal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5062–5067.

5.Best LM, Mughal M, Gurusamy KS. Non-surgical versus surgical treatment for esophageal cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;3:CD011498.

6.Conroy T, Galais MP, Raoul JL, et al. Definitive chemoradiotherapy with FOLFOX versus fluorouracil and cisplatin in patients with oesophageal cancer (PRODIGE5/ACCORD17): final results of a randomised, phase 2/3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:305–314.

7.Cooper JS, Guo MD, Herskovic A, et al. Chemoradiotherapy of locally advanced esophageal cancer: long-term follow-up of a prospective randomized trial (RTOG 85-01). Radiation Therapy Oncology Group. JAMA. 1999;281(17):1623–1627.

8.Cunningham D, Allum WH, Stenning SP, et al. Perioperative chemotherapy versus surgery alone for resectable gastroesophageal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:11–20.

9.Cunningham D, Starling N, Rao S, et al. Capecitabine and oxaliplatin for advanced esophagogastric cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:36–46.

10.Fuchs CS, Doi T, Jang RW, et al. KEYNOTE-059 cohort 1: Efficacy and safety of pembrolizumab (pembro) monotherapy in patients with previously treated advanced gastric cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(15_suppl):Abstract 4003.

11.Fuchs CS, Niedzwiecki D, Mamon HJ, et al. Adjuvant chemoradiotherapy with epirubicin, cisplatin, and fluorouracil compared with adjuvant chemoradiotherapy with fluorouracil and leucovorin after curative resection of gastric cancer: results from CALGB 80101 (Alliance). J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(32):3671–3677.

12.Fuchs CS, Tomasek J, Yong CJ, et al. Ramucirumab monotherapy for previously treated advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (REGARD): an international, randomized, multicentre, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2014;383:31–39.

13.Hecht JR, Bang YJ, Qin SK, et al. Lapatinib in combination with capecitabine plus oxaliplatin in human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive advanced or metastatic gastric, esophageal or gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma: TRIO-013/LOGIC—a randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(5):443–451.

14.Kang YK, Boku N, Satoh T, et al. Nivolumab in patients with advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer refractory to, or intolerant of, at least two previous chemotherapy regimens (ONO-4538-12, ATTRACTION-2): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;390:2461–2471.

15.Kelsen DP, Ginsberg R, Pajak TF, et al. Chemotherapy followed by surgery compared with surgery alone for localized esophageal cancer. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(27):1979–1984.

16.Kidane B, Coughlin S, Vogt K, et al. Preoperative chemotherapy for resectable thoracic esophageal cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(5):CD001556.

17.MacDonald JS, Smalley SR, Benedetti J, et al. Chemoradiotherapy after surgery compared with surgery alone for adenocarcinoma of the stomach or gastroesophageal junction. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:725–730.

18.Njei B, McCarty TR, Birk JW, et al. Trends in esophageal cancer survival in United States adults from 1973-2009: A SEER database analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;31(6):1141–1146.

19.Ohtsu A, Shah MA, Van Cutsem E, et al. Bevacizumab in combination with chemotherapy as first-line therapy in advanced gastric cancer: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3968–3976.

20.Omloo JM, Lagarde SM, Hulscher JB et al. Extended transthoracic resection compared with limited transhiatal resection for adenocarcinoma of the mid/distal esophagus. Five-year survival of a randomized clinical trial. Ann Surg. 2007;246:992–1000.

21.Satoh T, Xu RH, Chung HC, et al. Lapatinib plus paclitaxel versus paclitaxel alone in the second-line treatment of HER2-amplified advanced gastric cancer in Asian populations: TyTAN—a randomized, phase III study. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:2039–2049.

22.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A, et al. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:7–30.

23.Sjoquist KM, Burmeister BH, Smithers BM, et al. Survival after neoadjuvant chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy for resectable esophageal carcinoma: an updated meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(7):681–692.

24.Stahl M, Stuschke M, Lehmann N, et al. Chemoradiation with and without surgery in patients with locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(10):2310–2317.

25.Tepper J, Krasna MJ, Niedzwiecki D, et al. Phase III trial of trimodality therapy with cisplatin, fluorouracil, radiotherapy, and surgery compared with surgery alone for esophageal cancer: CALGB 9781. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(7):1086–1092.

26.Tougeron D, Scotté M, Hamidou H, et al. Definitive chemoradiotherapy in patients with esophageal adenocarcinoma: an alternative to surgery? J Surg Oncol. 2012;105(8):761–766.

27.Van Cutsem E, Moiseyenko VM, Tjulandin S, et al. Phase III study of docetaxol and cisplatin plus fluorouracil compared with cisplatin and fluorouracil as first-line therapy for advanced gastric cancer: a report of the V325 Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4991–4997.

28.Van Hagen P, Hulshof MC, van der Gaast A, et al. Preoperative chemoradiotherapy for esophageal or junctional cancer: Results from a multicentre randomized phase III trial. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2074–2084.

29.Verheij M, Jansen EPM, Cats A, et al. A multicenter randomized phase III trial of neo-adjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgery and chemotherapy or by surgery and chemoradiotherapy in resectable gastric cancer: first results from the CRITICS study (abstract). J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(suppl): abstr 4000.

30.Wong R, Malthaner R. Combined chemotherapy and radiotherapy (without surgery) compared with radiotherapy alone in localized carcinoma of the esophagus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(1):CD002092.