Hiral Parekh and Thomas J. George, Jr.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Worldwide, gastric carcinoma represents the fifth most common malignancy. The frequency of gastric carcinoma at different sites within the stomach has changed in the United States over recent decades. Cancer of the distal half of the stomach has been decreasing in the United States since the 1930s. However, over the past two decades, the incidence of cancer of the cardia and gastroesophageal junction has been rapidly rising, particularly in patients younger than 40 years. There are expected to be 28,000 new cases and 10,960 deaths from gastric carcinoma in the United States in 2017.

RISK FACTORS

Average age at onset is fifth decade.

Average age at onset is fifth decade.

Male-to-female ratio is 1.7:1.

Male-to-female ratio is 1.7:1.

African-American-to-white ratio is 1.8:1.

African-American-to-white ratio is 1.8:1.

Precursor conditions include chronic atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia, pernicious anemia (10% to 20% incidence), partial gastrectomy for benign disease, Helicobacter pylori infection (especially childhood exposure—3- to 5-fold increase), Ménétrier’s disease, and gastric adenomatous polyps. These precursor lesions are largely linked to distal (intestinal type) gastric carcinoma.

Precursor conditions include chronic atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia, pernicious anemia (10% to 20% incidence), partial gastrectomy for benign disease, Helicobacter pylori infection (especially childhood exposure—3- to 5-fold increase), Ménétrier’s disease, and gastric adenomatous polyps. These precursor lesions are largely linked to distal (intestinal type) gastric carcinoma.

Family history: first degree (2- to 3-fold); the family of Napoléon Bonaparte is an example; familial clustering; patients with hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (Lynch syndrome II) are at increased risk; germline mutations of E-cadherin (CDH1 gene) have been linked to familial diffuse gastric cancer and associated lobular breast cancer. Gastric adenocarcinoma and proximal polyposis of the stomach (GAPPS) is an autosomal dominant syndrome characterized by fundic gland polyposis and intestinal type adenocarcinoma.

Family history: first degree (2- to 3-fold); the family of Napoléon Bonaparte is an example; familial clustering; patients with hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (Lynch syndrome II) are at increased risk; germline mutations of E-cadherin (CDH1 gene) have been linked to familial diffuse gastric cancer and associated lobular breast cancer. Gastric adenocarcinoma and proximal polyposis of the stomach (GAPPS) is an autosomal dominant syndrome characterized by fundic gland polyposis and intestinal type adenocarcinoma.

Tobacco use results in a 1.5- to 3-fold increased risk for cancer.

Tobacco use results in a 1.5- to 3-fold increased risk for cancer.

High salt and nitrosamine food content from fermenting and smoking process.

High salt and nitrosamine food content from fermenting and smoking process.

Deficiencies of vitamins A, C, and E; β-carotene; selenium; and fiber.

Deficiencies of vitamins A, C, and E; β-carotene; selenium; and fiber.

Blood type A.

Blood type A.

Alcohol.

Alcohol.

The marked rise in the incidence of gastroesophageal and proximal gastric adenocarcinoma appears to be strongly correlated to the rising incidence of Barrett’s esophagus.

The marked rise in the incidence of gastroesophageal and proximal gastric adenocarcinoma appears to be strongly correlated to the rising incidence of Barrett’s esophagus.

SCREENING

In most countries, screening of the general populations is not practical because of a low incidence of gastric cancer. However, screening is justified in countries where the incidence of gastric cancer is high. Japanese screening guidelines include initial upper endoscopy at age 50, with follow-up endoscopy for abnormalities. Routine screening is not recommended in the United States.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Most gastric cancers are adenocarcinomas (more than 90%) of two distinct histologic types: intestinal and diffuse. In general, the term “gastric cancer” is commonly used to refer to adenocarcinoma of the stomach. Other cancers of the stomach include non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas (NHL), leiomyosarcomas, carcinoids, and gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST). Differentiating between adenocarcinoma and lymphoma is critical because the prognosis and treatment for these two entities differ considerably. Although less common, metastases to the stomach include melanoma, breast, and ovarian cancers.

Intestinal Type

The epidemic form of cancer is further differentiated by gland formation and is associated with precancerous lesions, gastric atrophy, and intestinal metaplasia. The intestinal form accounts for most distal cancers with a stable or declining incidence. These cancers in particular are associated with H. pylori infection. In this carcinogenesis model, the interplay of environmental factors leads to glandular atrophy, relative achlorhydria, and increased gastric pH. The resulting bacterial overgrowth leads to production of nitrites and nitroso compounds causing further gastric atrophy and intestinal metaplasia, thereby increasing the risk of cancer.

The recent decline in gastric carcinoma in the United States is likely the result of a decline in the incidence of intestinal-type lesions but remains a common cause of gastric carcinoma worldwide. Intestinal-type lesions are associated with an increased frequency of overexpression of epidermal growth factor receptor erbB-2 and erbB-3.

Diffuse Type

The endemic form of carcinoma is more common in younger patients and exhibits undifferentiated signet-ring histology. There is a predilection for diffuse submucosal spread because of lack of cell cohesion, leading to linitis plastica. Contiguous spread of the carcinoma to the peritoneum is common. Precancerous lesions have not been identified. Although a carcinogenesis model has not been proposed, it is associated with H. pylori infection. Genetic predispositions to endemic forms of carcinoma have been reported, as have associations between carcinoma and individuals with type A blood. These cancers occur in the proximal stomach where increased incidence has been observed worldwide. Stage for stage, these cancers have a worse prognosis than do distal cancers.

Diffuse lesions have been linked to abnormalities of fibroblast growth factor systems, including the K-sam oncogene as well as E-cadherin mutations. The latter results in loss of cell–cell adhesions.

Molecular Analysis

Loss of heterozygosity of chromosome 5q or APC gene (deleted in 34% of gastric cancers), 17p, and 18q (DCC gene).

Loss of heterozygosity of chromosome 5q or APC gene (deleted in 34% of gastric cancers), 17p, and 18q (DCC gene).

Microsatellite instability, particularly of transforming growth factor-β type II receptor, with subsequent growth-inhibition deregulation.

Microsatellite instability, particularly of transforming growth factor-β type II receptor, with subsequent growth-inhibition deregulation.

p53 is mutated in approximately 40% to 60% caused by allelic loss and base transition mutations.

p53 is mutated in approximately 40% to 60% caused by allelic loss and base transition mutations.

Mutations of E-cadherin expression (CDH1 gene on 16q), a cell adhesion mediator, is observed in diffuse-type undifferentiated cancers and is associated with an increased incidence of lobular breast cancer.

Mutations of E-cadherin expression (CDH1 gene on 16q), a cell adhesion mediator, is observed in diffuse-type undifferentiated cancers and is associated with an increased incidence of lobular breast cancer.

Epidermal growth factor receptor overexpression, specifically Her2/neu and erbB-2/erbB-3 especially in intestinal forms.

Epidermal growth factor receptor overexpression, specifically Her2/neu and erbB-2/erbB-3 especially in intestinal forms.

Epstein-Barr viral genomes are detected.

Epstein-Barr viral genomes are detected.

Ras mutations are rarely reported (less than 10%) in contrast to other gastrointestinal cancers.

Ras mutations are rarely reported (less than 10%) in contrast to other gastrointestinal cancers.

DIAGNOSIS

Gastric carcinoma, when superficial and surgically curable, typically produces no symptoms. Among 18,365 patients analyzed by the American College of Surgeons, patients presented with the following symptoms: weight loss (62%), abdominal pain (52%), nausea (34%), anorexia (32%), dysphagia (26%), melena (20%), early satiety (18%), ulcer-type pain (17%), and lower-extremity edema (6%).

Clinical findings at presentation may include anemia (42%), hypoproteinemia (26%), abnormal liver functions (26%), and fecal occult blood (40%). Medically refractory or persistent peptic ulcer should prompt endoscopic evaluation.

Gastric carcinomas primarily spread by direct extension, invading adjacent structures with resultant peritoneal carcinomatosis and malignant ascites. The liver, followed by the lung, is the most common site of hematogenous dissemination. The disease may also spread as follows:

To intra-abdominal nodes and left supraclavicular nodes (Virchow’s node).

To intra-abdominal nodes and left supraclavicular nodes (Virchow’s node).

Along peritoneal surfaces, resulting in a periumbilical lymph node (Sister Mary Joseph node, named after an operating room nurse at the Mayo Clinic, which form as tumor spreads along the falciform ligament to subcutaneous sites).

Along peritoneal surfaces, resulting in a periumbilical lymph node (Sister Mary Joseph node, named after an operating room nurse at the Mayo Clinic, which form as tumor spreads along the falciform ligament to subcutaneous sites).

To a left anterior axillary lymph node resulting from the spread of proximal primary cancer to lower esophageal and intrathoracic lymphatics (Irish node).

To a left anterior axillary lymph node resulting from the spread of proximal primary cancer to lower esophageal and intrathoracic lymphatics (Irish node).

To enlarged ovary (Krukenberg tumor; ovarian metastases).

To enlarged ovary (Krukenberg tumor; ovarian metastases).

To a mass in the cul-de-sac (Blumer shelf), which is palpable on rectal or bimanual examination.

To a mass in the cul-de-sac (Blumer shelf), which is palpable on rectal or bimanual examination.

Paraneoplastic Syndromes

Skin syndromes: acanthosis nigricans, dermatomyositis, circinate erythemas, pemphigoid, and acute onset of seborrheic keratoses (Leser-Trélat sign).

Skin syndromes: acanthosis nigricans, dermatomyositis, circinate erythemas, pemphigoid, and acute onset of seborrheic keratoses (Leser-Trélat sign).

Central nervous system syndromes: dementia and cerebellar ataxia.

Central nervous system syndromes: dementia and cerebellar ataxia.

Miscellaneous: thrombophlebitis, microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, membranous nephropathy.

Miscellaneous: thrombophlebitis, microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, membranous nephropathy.

Tumor Markers

Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) is elevated in 40% to 50% of cases. It is useful in follow-up and monitoring response to therapy, but not for screening. α-Fetoprotein and CA 19-9 are elevated in 30% of patients with gastric cancer, but are of limited clinical use.

STAGING

The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) has designated staging by TNM classification. In the 2017 AJCC eighth edition, tumors arising at the gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) or in the cardia of the stomach within 5 cm of the GEJ that extend into the GEJ or esophagus are termed esophageal rather than gastric cancers. Gastric tumors involving muscolaris propria (T2), subserosa (T3), and serosa (T4a) are considered resectable whereas tumors with invasion of adjacent structures (T4b) are not. Nodal stage relates to number of involved regional nodes: N1, 1 to 2 involved nodes; N2, 3 to 6 involved nodes; N3a, 7 to 15 involved nodes; and N3b, 16 or more involved nodes. The presence of positive peritoneal cytology is considered M1 as are distant metastases. Many of these staging classifiers represent changes from previous AJCC staging system editions but continue to refine prognostic groups based on the best available outcomes data (Table 5.1). Of note, alternative staging systems are used in Japan.

TABLE 5.1 Observed Survival Rates for Surgically Resected Gastric Adenocarcinomas in a Representative Western Population

Stage | Survival Rates | ||

5 year (%) | 10 year (%) | Median (mo) | |

IA | 82 | 68 | ND |

IB | 69 | 60 | 151 |

IIA | 60 | 43 | 102 |

IIB | 42 | 32 | 48 |

IIIA | 28 | 18 | 28 |

IIIB | 18 | 11 | 19 |

IIIC | 11 | 6 | 12 |

IV | 6 | 5 | 9 |

ND, not determined.

Modified from Reim D, Loos M, Vogl F, et al. Prognostic implications of the seventh edition of the international union against cancer classification for patients with gastric cancer: the Western experience of patients treated in a single-center European institution. J Clin Oncol. 2013 Jan 10;31(2):263–271.

Initial upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and double-contrast barium swallow identify suggestive lesions and have diagnostic accuracy of 95% and 75%, respectively, but add little to preoperative staging otherwise.

Initial upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and double-contrast barium swallow identify suggestive lesions and have diagnostic accuracy of 95% and 75%, respectively, but add little to preoperative staging otherwise.

Endoscopic ultrasonography assesses the depth of tumor invasion (T staging) and nodal involvement (N staging) with accuracies up to 90% and 75%, respectively.

Endoscopic ultrasonography assesses the depth of tumor invasion (T staging) and nodal involvement (N staging) with accuracies up to 90% and 75%, respectively.

Computerized tomographic scanning is useful for assessing local extension, lymph node involvement, and presence of metastasis, although understaging occurs in most cases.

Computerized tomographic scanning is useful for assessing local extension, lymph node involvement, and presence of metastasis, although understaging occurs in most cases.

Although whole-body 2-[18F]fluoro-2-deoxyglucose (FDG)–positron emission tomography (PET) may be useful in detecting metastasis as part of preoperative staging in some gastric cancer patients, the sensitivity in detecting early stage gastric cancer is only about 20% and overall appears less reliable than in esophageal cancer.

Although whole-body 2-[18F]fluoro-2-deoxyglucose (FDG)–positron emission tomography (PET) may be useful in detecting metastasis as part of preoperative staging in some gastric cancer patients, the sensitivity in detecting early stage gastric cancer is only about 20% and overall appears less reliable than in esophageal cancer.

PROGNOSIS

Pathologic staging remains the most important determinant of prognosis (Table 5.1). Other prognostic variables that have been proposed to be associated with an unfavorable outcome include the following:

Older age

Older age

Male gender

Male gender

Weight loss greater than 10%

Weight loss greater than 10%

Location of tumor

Location of tumor

Tumor histology: Diffuse versus intestinal (5-year survival after resection, 16% vs. 26%, respectively); high grade or undifferentiated tumors

Tumor histology: Diffuse versus intestinal (5-year survival after resection, 16% vs. 26%, respectively); high grade or undifferentiated tumors

Four or more lymph nodes involved

Four or more lymph nodes involved

Aneuploid tumors

Aneuploid tumors

Elevations in epidermal growth factor or P-glycoprotein level

Elevations in epidermal growth factor or P-glycoprotein level

Overexpression of ERCC1 and p53; loss of p21 and p27

Overexpression of ERCC1 and p53; loss of p21 and p27

MANAGEMENT OF GASTRIC CANCER

Standard of Care

Although surgical resection remains the cornerstone of gastric cancer treatment, the optimal extent of nodal resection remains controversial. The high rate of recurrence and poor survival of patients following surgery provide a rationale for the use of adjuvant or perioperative treatment. Adjuvant radiotherapy alone does not improve survival following resection. In addition to complete surgical resection, either postoperative adjuvant chemoradiotherapy (chemoRT) or perioperative polychemotherapy appear to confer survival advantages. The results of the Intergroup 0116 study show that the combination of 5-fluorouracil (5-FU)–based chemoRT significantly prolongs disease-free (DFS) and overall survival (OS) when compared to no adjuvant treatment. Similarly, the use of polychemotherapy pre- and postoperatively can increase DFS and OS compared to observation.

In advanced gastric cancer, chemotherapy enhances quality of life and prolongs survival when compared with the best supportive care. Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), a key driver of tumorigenesis, is overexpressed in 7% to 34% of esophagogastric tumors. The standard of care for HER2 overexpressing advanced or metastatic gastric cancer is trastuzumab in combination with cytotoxic chemotherapy. Of the commonly used regimens, triple combination chemotherapy with either docetaxel, cisplatin, and 5-FU (DCF) or epirubicin, oxaliplatin, and capecitabine (EOX) probably has the strongest claims to this role for the majority of fit patients, with modified FOLFOX (5-FU, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin) also frequently used in the United States. However, there is a pressing need for assessing new agents, both cytotoxic and molecularly targeted, in the advanced and adjuvant settings and enrollment in clinical trial is highly encouraged.

Resectable Disease

Complete surgical resection of the tumor and adjacent lymph nodes remains the only chance for cure. Unfortunately, only 20% of U.S. patients with gastric cancer have disease at presentation amenable to such therapy. Resection of gastric cancer is indicated in patients with stage I to III disease. Tumor size and location dictate the type of surgical procedure to be used. An exploration to exclude carcinomatosis just prior to the definitive resection is justified in this disease. Current surgical issues include subtotal versus total gastrectomy, extent of lymph node dissection, and palliative surgery.

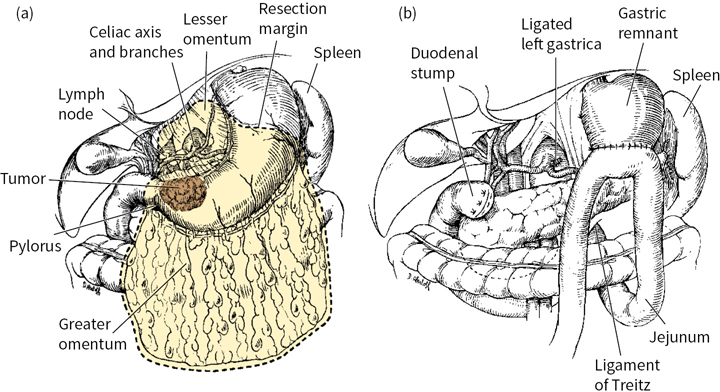

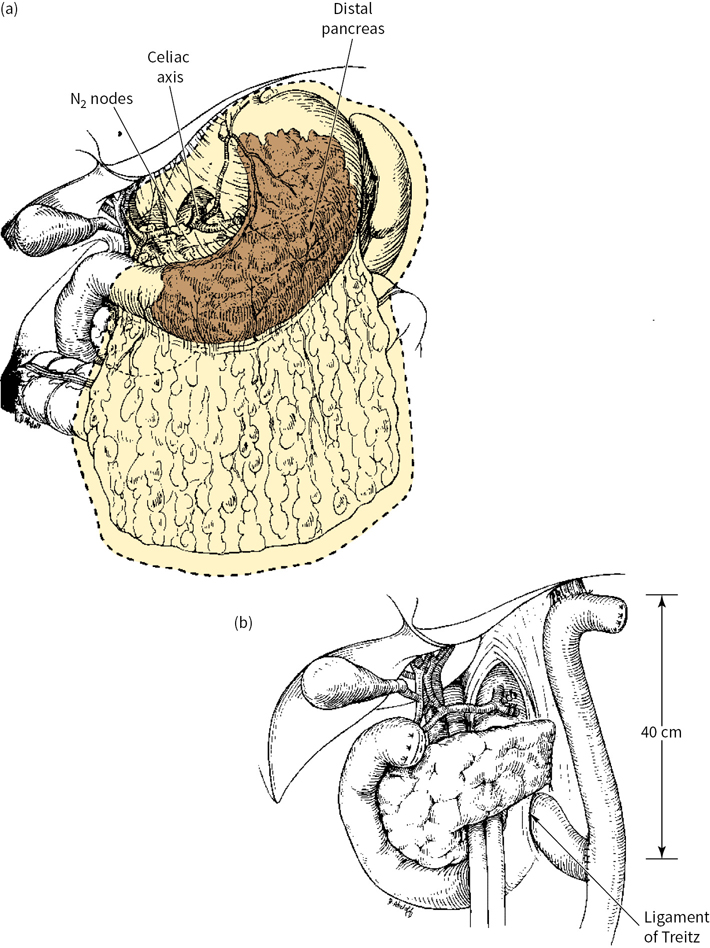

Subtotal versus Total Gastrectomy

Subtotal gastrectomy (SG) may be performed for proximal cardia or distal lesions, provided that the fundus or cardioesophageal junction is not involved (Fig. 5.1). Total gastrectomy (TG) is more appropriate if tumor involvement is diffuse and arises in the body of the stomach, with extension to within 6 cm of the cardia. TG is associated with increased postoperative complications, mortality, and quality-of-life decrement, necessitating thorough consideration of complete gastric resection (Fig. 5.2).

FIGURE 5.1 (a) and (b): Subtotal gastrectomy.

FIGURE 5.2 (a) and (b): Total gastrectomy.

Extent of Lymph Node Dissection

Regional lymph node dissection is important for accurate staging and may have therapeutic benefit as well. The extent of lymphadenectomy is categorized by the regional nodal groups removed (Table 5.2). At least 16 lymph nodes must be reported for accurate AJCC staging. D2 lymphadenectomy is reported to improve survival in patients with T1, T2, T3, and some serosa-involved (currently T4a) lesions as compared to D1. However, factors such as operative time, hospitalization length, transfusion requirements, and morbidity are all increased. The routine inclusion of splenectomy in D2 resections is no longer advocated given higher postoperative complications. The greatest benefit of more extensive lymph node dissection may occur in early gastric cancer lesions with small tumors and superficial mucosal involvement as up to 20% of such lesions have occult lymph node involvement.

TABLE 5.2 Classification of Regional Lymph Node Dissection

Dissection (D) | Regional Lymph Node Groups Removed |

D0 | None |

D1 | Perigastric |

D2 | D1 plus nodes along hepatic, left gastric, celiac, and splenic arteries; splenic hilar nodes; +/– splenectomy |

D3a | D2 plus periaortic and portahepatis |

a Periaortic and portahepatis nodes are typically considered distant metastatic disease.

For patients with locally advanced or metastatic disease, moderate doses of external-beam radiation can be used to palliate symptoms of pain, obstruction, and bleeding but do not routinely improve survival.

For patients with locally advanced or metastatic disease, moderate doses of external-beam radiation can be used to palliate symptoms of pain, obstruction, and bleeding but do not routinely improve survival.

Local or regional recurrence in the gastric or tumor bed, the anastomosis, or regional lymph nodes occurs in 40% to 65% of patients after gastric resection with curative intent. The high frequency of such relapses has generated interest in perioperative therapy. Radiotherapy (RT) in this setting is limited by the technical challenges inherent in abdominal irradiation, optimal definition of fields, diminished performance status, and nutritional state of many patients with gastric cancer.

Local or regional recurrence in the gastric or tumor bed, the anastomosis, or regional lymph nodes occurs in 40% to 65% of patients after gastric resection with curative intent. The high frequency of such relapses has generated interest in perioperative therapy. Radiotherapy (RT) in this setting is limited by the technical challenges inherent in abdominal irradiation, optimal definition of fields, diminished performance status, and nutritional state of many patients with gastric cancer.

A prospective randomized trial from the British Stomach Cancer Group failed to demonstrate a survival benefit for postoperative adjuvant radiation alone, although locoregional failures had decreased from 27% to 10.6%.

A prospective randomized trial from the British Stomach Cancer Group failed to demonstrate a survival benefit for postoperative adjuvant radiation alone, although locoregional failures had decreased from 27% to 10.6%.

Attempts to improve the efficacy and minimize toxicity with newer RT techniques have been investigated. Sixty patients who underwent curative resection at the National Cancer Institute were randomized to receive either adjuvant intraoperative radiotherapy (IORT) or conventional RT. IORT failed to afford a benefit over conventional therapy in OS and remains unavailable to many outside of a clinical trial or specialized center.

Attempts to improve the efficacy and minimize toxicity with newer RT techniques have been investigated. Sixty patients who underwent curative resection at the National Cancer Institute were randomized to receive either adjuvant intraoperative radiotherapy (IORT) or conventional RT. IORT failed to afford a benefit over conventional therapy in OS and remains unavailable to many outside of a clinical trial or specialized center.

In patients with locally unresectable pancreatic and gastric adenocarcinoma, the Gastrointestinal Tumor Study Group (GITSG) has shown that combined-modality therapy is superior to either RT or chemotherapy alone. On the basis of this concept, combined chemoRT (typically in combination with 5-FU) has been evaluated in both the neoadjuvant (preoperative) and the adjuvant (postoperative) settings.

In patients with locally unresectable pancreatic and gastric adenocarcinoma, the Gastrointestinal Tumor Study Group (GITSG) has shown that combined-modality therapy is superior to either RT or chemotherapy alone. On the basis of this concept, combined chemoRT (typically in combination with 5-FU) has been evaluated in both the neoadjuvant (preoperative) and the adjuvant (postoperative) settings.

Perioperative Chemoradiotherapy

Aside from GEJ and high gastric cardia tumors, the available data on the role of neoadjuvant chemoRT for gastric cancer are not conclusive. Although neoadjuvant therapy may reduce the tumor mass in many patients, several randomized controlled trials have shown that compared with primary resection, a multimodal approach does not result in a survival benefit in patients with potentially resectable tumors. In contrast, for some patients with locally advanced tumors (i.e., patients in whom complete tumor removal with upfront surgery seems unlikely), neoadjuvant chemoRT may increase the likelihood of complete tumor resection on subsequent surgery. However, predicting those likely to benefit from this approach remains an ongoing research question.

Adjuvant chemoRT has been evaluated in the United States. In a phase III Intergroup trial (INT-0116), 556 patients with completely resected stage IB to stage IV M0 adenocarcinoma of the stomach and gastroesophageal junction were randomized to receive best supportive care or adjuvant chemotherapy (5-FU and leucovorin) and concurrent radiation therapy (45 Gy). With >6-year median follow-up, median survival was 35 months for the adjuvant chemoRT group as compared to 27 months for the surgery-alone arm (P = 0.006). Both 3-year OS (50% vs. 41%; P = 0.006) and relapse-free survival (48% vs. 31%; P < 0.0001) favored adjuvant chemoRT. Although treatment-related mortality was 1% in this study, only 65% of patients completed all therapy as planned and many had inadequate lymph node resections (54% D0). After 10-year median follow-up, persistent benefit in OS (HR 1.32; 95% CI, 1.10 to 1.60; P = 0.0046) and relapse-free survival (HR 1.51; 95% CI, 1.25 to 1.83; P = 0.001) were observed without excess treatment related late toxicities. This study established adjuvant chemoRT as a standard of care for gastric cancer in the United States.

In Japan, patients who underwent complete surgical resection for stage II or III gastric cancer with D2 lymphadenectomy appeared to benefit from adjuvant S-1, a novel oral fluoropyrimidine. In a randomized controlled trial, patients were randomized to 1 year of monotherapy or surveillance alone. The study was closed early after interim analysis confirmed a 3-year OS (80% vs. 70%; P = 0.002) and relapse-free survival (72% vs. 60%; P = 0.002) advantage in favor of adjuvant chemotherapy. At 5-year follow up, the improved OS rate (72% vs. 61%) and relapse-free survival rate (65% vs. 53%) persisted. S-1 is approved for adjuvant therapy for gastric cancer in Japan and for advanced gastric cancer in Europe, but it is not commercially available in the United States.

In Europe, focus has been on the role of more potent polychemotherapy regimens in the perioperative setting without RT. The UK Medical Research Council conducted a randomized controlled trial (MAGIC trial) comparing three cycles of pre- and postoperative epirubicin, cisplatin, and 5-FU (ECF) to surgery alone in patients with resectable stage II to IV nonmetastatic gastric cancer; 503 patients were stratified according to surgeon, tumor site, and performance status. Perioperative chemotherapy improved 5-year OS (36% vs. 23%; P = 0.009) and reduced local and distant recurrence. There appeared to be significant downstaging by chemotherapy treatment, with more patients deemed by the operating surgeon to have had a “curative” resection (79% vs. 70%; P = 0.03), smaller tumors (median 3 vs. 5 cm; P < 0.001), T1/T2 stage tumors (52% vs. 37%; P = 0.002), and N1/N2 stage disease (84% vs. 71%; P = 0.01). Toxicity was feasible with postoperative complications comparable; however, nearly one-third of patients who began with preoperative chemotherapy did not receive postoperative chemotherapy owing to progressive disease, complications, or patient request.

A French multicenter trial also showed a survival benefit for perioperative chemotherapy. Patients with potentially resectable stage II or higher adenocarcinoma of the stomach, GEJ or distal esophagus (total 224) were randomly assigned to two or three preoperative cycles of cisplatin/5-FU infusion and three or four postoperative cycles of the same regimen versus surgery alone. At a median follow-up of 5.7 years, 5-year OS (38% vs. 24%; HR 0.69; 95% CI, 0.50 to 0.95; P = 0.02) and DFS (34% vs. 19%; HR 0.65; 95% CI, 0.48 to 0.89; P = 0.003) were improved in the polychemotherapy arm. Curative resection rate was significantly improved with perioperative polychemotherapy (84% vs. 73%; P = 0.04) with similar postoperative morbidity in the two groups. The phase II/III FLOT4-AIO trial compared four preoperative and four postoperative courses of the docetaxel-based triplet FLOT regimen (docetaxel, oxaliplatin, and 5FU) versus epirubicin-based triplet therapy in patients with resectable adenocarcinoma of the stomach or EGJ. In the 716 enrolled patients, FLOT was associated with a median OS improvement (50 vs. 35 months; HR 0.77; P = 0.012). In Europe, perioperative polychemotherapy is considered a standard of care.

Postoperative Chemoradiotherapy versus Perioperative Chemotherapy

There are no randomized controlled trials directly comparing these two standards of care. The ARTIST randomized phase III trial did not show a survival improvement with adjuvant chemoRT compared to adjuvant chemotherapy alone in patients with D2 resected gastric cancer. Patients (n = 458, stage IB-IV M0) were randomly assigned to chemotherapy (capecitabine and cisplatin) or chemoRT (cisplatin/capecitabine followed by capecitabine/radiation [45 Gy] followed by cisplatin/capecitabine). After >4 years follow-up, no significant difference in locoregional recurrences (8.3% in chemo alone vs. 4.8% in chemoRT; P = 0.3533) or distant metastases (24.6% in chemo vs. 20.4% in chemoRT; P = 0.5568) was observed. Treatment completion rate was better than the INT-0116 trial with 75% of patients having completed the planned chemotherapy and 82% the chemoRT. Given that a multivariate analysis showed that chemoRT improved 3-year DFS in those with node-positive disease (HR 0.68; 95% CI, 0.47 to 0.99; P = 0.047), a subsequent phase III trial (ARTIST-II) study to evaluate the benefit of chemoRT in patients who have undergone D2 lymph node dissection with positive lymph nodes is currently enrolling.

CALGB 80101, a US Intergroup study, compared the INT-0116 adjuvant chemoRT versus postoperative ECF before and after chemoRT. Patients (n = 546) with completely resected gastric or GEJ tumors that were >T2 or node positive were included. Through a preliminary report, patients receiving ECF had lower rates of diarrhea, mucositis, and grade >4 neutropenia. However, the primary endpoint of OS was not significantly better with ECF at 3 years (52% vs. 50%). The primary tumor location did not affect treatment outcome.

With the goal of assessing the role of postoperative intensification of treatment with chemoRT, the phase III CRITICS study recently completed. Patients with stage Ib-IVa gastric cancer (n = 788) were treated with preoperative epirubicin, capecitabine, and a platinum compound (cisplatin or oxaliplatin) followed by surgery. After surgery, patients were randomized to an additional three cycles of the same chemotherapy versus chemoRT (45 Gy with weekly cisplatin and daily capecitabine). There was no difference in the 5-year survival between two arms. (40.8% vs. 40.9%).

Unresectable or Metastatic Disease

Primary goals of therapy should focus on improvement in symptoms, delay of disease progression, pain control, nutritional support, and quality of life. Although a role for palliative surgery and radiotherapy exists (see previous sections), chemotherapy remains the primary means of palliative treatment in this setting. The most commonly administered chemotherapeutic agents with objective response rates in advanced gastric cancer include mitomycin, antifolates, anthracyclines, fluoropyrimidines, platinums, taxanes, and topoisomerase inhibitors. Monotherapy with a single agent results in a 10% to 30% response rate with mild toxicities (Table 5.3). 5-FU is the most extensively studied, producing a 20% response rate. Complete responses with single agents are rare and disease control is relatively brief. Combination chemotherapy provides a better response rate with survival advantage over best supportive care in randomized studies. Molecularly targeted therapies against the HER2 and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) pathways now have an active role in the treatment of metastatic gastric cancer.

TABLE 5.3 Antineoplastic Therapy with Activity in Advanced Gastric Cancer

Class | Examples |

Antifolates | Methotrexate |

Anthracyclines | Doxorubicin, epirubicin |

Fluoropyrimidines | 5-FU, capecitabine, S-1, UFT |

Platinums | Cisplatin, carboplatin, oxaliplatin |

Taxanes | Docetaxel, paclitaxel |

Topoisomerase inhibitors | Etoposide, irinotecan |

Targeted therapies | Trastuzumab, ramucirumab, apatinib |

Palliative surgery and stents should be considered in patients with obstruction, bleeding, or pain, despite operative mortalities of 25% to 50%. Gastrojejunostomy bypass surgery alone may provide a 2-fold increase in mean survival. The selection of patients most likely to benefit from this or other palliative surgical interventions require further evaluation with prospective studies and multidisciplinary conference discussion.

Plastic and expansile metal stents are associated with successful palliation of obstructive symptoms in more than 85% of patients with tumors in the GEJ and in the cardia.

Various combinations of active agents have been reported to improve the response rate (20% to 50%) among patients with advanced gastric carcinoma (Table 5.4). While utilizing 5-FU as a backbone, FAMTX (5-FU, doxorubicin, methotrexate) became an international standard after direct comparison to FAM (5-FU, doxorubicin, mitomycin) supported a superiority with a survival advantage for FAMTX. The addition of cisplatin into combination regimens was supported by subsequent studies in both Europe and the United States.

Historically, the most commonly used combination regimens include FAMTX, FAM, FAP, ECF, ELF, FLAP (5-FU, leucovorin, doxorubicin, cisplatin), PELF (cisplatin, epidoxorubicin, leucovorin, 5-FU with glutathione and filgrastim), and FUP or CF (5-FU, cisplatin). The combination of a fluoropyrimidine and platinum is most commonly used in the United States.

TABLE 5.4 Randomized Studies of Combination Antineoplastic Therapy in Advanced Gastric Cancer

Treatment Arms | Patients (n) | RR (%) | Median Survival (mo) |

FAMTX vs. FAM | 213 | 41 vs. 9a | 10.5 vs. 7.3a |

PELF vs. FAM | 147 | 43 vs. 15a | 8.8 vs. 5.8 |

FAMTX vs. EAP | 60 | 33 vs. 20 | 7.3 vs. 6.1 |

ECF vs. FAMTX | 274 | 45 vs. 21a | 8.9 vs. 5.7a |

DCF vs. CF | 445 | 37 vs. 25a | 9.2 vs. 8.6a |

EOX vs. ECF | 488 | 48 vs. 40 | 11.2 vs. 9.9a |

Cis/S-1 vs. Cis/5-FU | 1,053 | 29 vs. 32 | 8.6 vs. 7.9 |

CF + Trastuzumab vs. CF | 298 | 47 vs. 35 | 13.8 vs. 11.1 |

PAC + Ram vs. PAC | 655 | 28 vs. 16 | 9.6 vs. 7.4 |

Ram vs. BSC | 355 | 8 vs. 3 | 5.2 vs. 3.8 |

Apatinib vs. BSC | 270 | 3 vs. 0 | 6.5 vs. 3.7 |

aDifference is statistically significant (P < 0.05).

RR, response rate; FAMTX, 5-FU, doxorubicin, and methotrexate; FAM, 5-FU, doxorubicin, mitomycin-C; PELF, cisplatin, epidoxorubicin, leucovorin, 5-FU with glutathione and filgrastim; EAP, etoposide, doxorubicin, cisplatin; ECF, epirubicin, cisplatin and 5-FU; EOX, epirubicin, oxaliplatin, capecitabine; DCF, docetaxel, cisplatin, 5-FU; CF, cisplatin, 5-FU; S-1, oral fluoropyrimidine; Ram, ramucirumab; PAC, paclitaxel; BSC, best supportive care.

Chemotherapeutic agents, including irinotecan, docetaxel, paclitaxel, and alternative platinums and fluoropyrimidines, have shown promising activity as single agents and have been actively incorporated into combination therapy (see Tables 5.3 and 5.4). A complete review of all agents is beyond the scope of this chapter.

Docetaxel is Federal Drug Administration approved in combination with cisplatin and 5-FU (DCF) in patients with advanced or metastatic gastric cancer, based on the results of a large phase III international trial; 445 patients were randomized to receive cisplatin and 5-FU with or without docetaxel. The addition of docetaxel resulted in an improvement in tumor response (37% vs. 25%; P = 0.01), time to progression (5.6 vs. 3.7 months; P < 0.001), and median survival (9.2 vs. 8.6 months; P = 0.02) with a doubling of 2-year survival (18% vs. 9%). These findings were at the cost of anticipated increased toxicity; however, maintenance of quality of life and performance status indices were longer for DCF. In a Japanese study, 20% of patients who showed no response to previous chemotherapy had a partial response to monotherapy with docetaxel.

S-1 is an oral fluoropyrimidine derivative composed of tegafur (5-FU prodrug), 5-chloro-2, 4-dihydroxypyridine (inhibitor of 5-FU degradation), and potassium oxonate (inhibitor of gastrointestinal toxicities). Because of the favorable safety profile of S-1 compared to infusional 5-FU, a multicenter prospective randomized phase III trial was conducted in 24 Western countries including the United States. Previously untreated patients (n = 1,053) with advanced gastric or GEJ adenocarcinoma were randomized to either cisplatin/S-1 or cisplatin/infusional 5-FU. The median OS (8.6 vs. 7.9 months; P = 0.20), overall response rate (29.1% vs. 31.9%; P = 0.40), median duration of response (6.5 vs. 5.8 months; P = 0.08), and treatment-related deaths (2.5% vs. 4.9%; P < 0.05) favored the cisplatin/S-1 arm. The cisplatin/S-1 arm had significant favorable toxicities as well. The lack of survival benefit but improved toxicity profile could have been due to the lower dose of cisplatin used in the cisplatin/S-1 arm.

Capecitabine is another oral fluoropyrimidine that has been substituted for infusional 5-FU in a variety of settings. It was formally evaluated with encouraging results in combination with a platinum alternative.

Oxaliplatin is a third-generation platinum with less nephrotoxicity, nausea, and bone marrow suppression than cisplatin. In a two-by-two designed study in patients with advanced gastric cancer, standard ECF chemotherapy was modified with oxaliplatin substituted for cisplatin and capecitabine substituted for 5-FU; 1,002 patients were randomly allocated between the four arms (ECF, EOF, ECX, and EOX). Capecitabine and oxaliplatin appeared as effective as 5-FU and cisplatin, respectively. Response rates and progression-free survival were nearly identical between the groups, with the EOX regimen showing superiority in OS over ECF (11.2 vs. 9.9 months; P = 0.02).

Biologic/Targeted Agents/Immunotherapy

New biologic therapies designed to inhibit or modulate targets of aberrant signal transduction in gastric cancer have been actively investigated. Inhibition of angiogenesis, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and epidermal growth factor (EGF) pathways are undergoing clinical testing and have shown early promising activity (see Tables 5.3 and 5.4). Immunotherapy (IO) treatments are active in advanced disease and represent a relatively new option for some patients. Predictors of durable response remain elusive to date.

Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor-2 (HER2)

Overexpression of EGF receptor (EGFR)-2 (HER2) is seen in approximately 7% to 22% of esophageogastric cancers. The prognostic significance of HER2 overexpression in esophagogastric adenocarcinoma is unclear. Similar to breast cancer, HER2 overexpression is predictive for response to anti-HER2 therapies. HER2 protein expression is assessed by immunohistochemical (IHC) staining and gene amplification by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH). HER2 overexpression in esophagogastric cancer is different from that in breast cancer because it tends to spare the digestive luminal membrane. Thus, an esophagogastric cancer with only partially circumferential (i.e., “basolateral” or “lateral”) membrane staining can still be categorized as 2+ or 3+. In contrast, a breast tumor must demonstrate complete circumferential membrane staining to be designated as 2+ or 3+. Using breast cancer HER2 interpretation criteria may underestimate expression in esophagogastric cancers. Modified criteria for interpreting HER2 by IHC in esophagogastric cancers were developed and validated with a high concordance rate of HER2 gene amplification and HER2 protein overexpression for IHC 0-1+ and 3+ cases. For an equivocal IHC 2+ expression, FISH analysis is recommended for confirmation.

Therapeutic targeting of HER2 overexpressing esophagogastric adenocarcinoma by a monoclonal antibody, trastuzumab, was studied in combination with chemotherapy. Patients (n = 592) with HER2-overexpressed advanced gastric and GEJ adenocarcinoma (ToGA trial) were randomized to standard chemotherapy (cisplatin/5-FU) with or without trastuzumab. The study demonstrated improved median OS (13.8 vs. 11.1 months; HR 0∙74; 95% CI 0∙60 to 0∙91; P = 0.0046) in those receiving trastuzumab. The toxicities between the two arms were comparable. Subgroup analysis demonstrated patients with HER2 IHC 3+ scores derived the greatest benefit from targeted therapy (HR 0.66; 95% CI 0.50 to 0.87). This trial established a new standard of care for advanced HER2 overexpressing esophagogastric tumors. Lapatinib, an orally active small molecule targeting EGFR1 and EGFR2 (HER2), failed to show a survival benefit when added to chemotherapy with capecitabine and oxalaplatin. Lapatinib also failed to improve OS when combined with paclitaxel in second-line therapy but demonstrated a trend toward improvement in the median OS (11 vs. 8.9 months; P = 0.1044). It is noteworthy that few patients had received prior trastuzumab (only 7% in lapatinib arm and 15% in combination). Thus, testing for and targeting HER2 overexpressing tumors with trastuzumab represents a clinically meaningful treatment option.

Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR)

Overexpression of EGFR is seen in 27% to 64% of gastric cancers with some studies suggesting it as a poor prognostic variable. Cetuximab is a partially humanized murine anti-EGFR monoclonal antibody that has been most extensively studied in gastric cancer. This agent has minimal activity as a single agent while in combination with doublet or triplet chemotherapy regimens it showed variable overall response rates (Table 5.4). The EXPAND trial randomized 904 patients with metastatic or locally advanced gastric cancer to chemotherapy (cisplatin and capecitabine) with or without cetuximab. The addition of cetuximab provided no benefit in progression-free survival but added toxicity. A fully humanized anti-EGFR monoclonal antibody (panitumumab) in combination with EOC (epirubicin, oxaliplatin, and capecitabine) was investigated in a randomized phase III (REAL-3) study. The addition of panitumumab to chemotherapy significantly reduced survival from 11.3 to 8.8 months. Of note, small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors of the EGFR (i.e., erlotinib and gefitinib) showed very limited activity in multiple phase II trials. Based upon currently available evidence, anti-EGFR therapy should not be used outside the context of a clinical trial.

A high tumor and circulating serum level of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in gastric cancer is associated with a poor prognosis. Ramucirumab, a recombinant monoclonal antibody of the IgG1 class targeting VEGFR-2, has demonstrated a survival advantage for palliative patients with previously treated gastric cancer. In the phase III REGARD trial, 355 previously treated patients with advanced or metastatic esophagogastric adenocarcinoma were randomly assigned to ramucirumab versus best supportive care. Ramucirumab was associated with significantly improved median progression free (2.1 vs. 1.3 months) and OS (5.2 vs. 3.8 months; HR 0.78; 95% CI 0.60 to 0.998; P = 0.047). The phase III RAINBOW trial added ramucirumab or placebo to weekly paclitaxel in 665 patients with metastatic esophagogastric adenocarcinoma who had disease progression on or within four months after first-line platinum and fluoropyrimidine-based combination therapy. The combination treatment was also associated with an improved median progression free (4.4 vs. 2.9 months) and OS (9.6 vs. 7.4 months; HR 0.807; 95% CI 0.678 to 0.962; P = 0.017). Ramucirumab, either alone or in combination with paclitaxel, is considered a standard targeted therapy for previously treated patients with metastatic gastric adenocarcinoma. Clinical trials are ongoing to determine any benefit in the first-line setting.

Of note, another monoclonal antibody against VEGF, bevacizumab, has already been tested in combination with first line chemotherapy (cisplatin/capecitabine or 5-FU) in advanced gastric cancer. Although the initial phase II study showed promising OS, the benefit was not sustained in the global, phase III AVAGAST study. This study randomized 774 patients to cisplatin/fluoropyrimidine combination chemotherapy with or without bevacizumab. Response rate (46% vs. 37%; P = 0.0315) and progression-free survival (6.7 vs. 5.3 months; P = 0.0037) were both improved with bevacizumab; however, there was no improvement in OS (12.2 vs. 10.1 months; P = 0.1002). Bevacizumab is currently under investigation in the perioperative setting.

Another orally active VEGFR 2 inhibitor is currently approved for use in China based on a multicenter randomized, double-blind trial in which 270 patients with advanced gastric cancer were randomly assigned in a 2:1 ratio to apatinib (850 mg daily) or placebo. Apatinib was associated with prolonged median progression free (2.6 vs. 1.8 months) and OS (6.5 vs. 4.7 months; HR 0.709; 95% CI, 0.537 to 0.937; P = 0.0156).

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy targeting programmed cell death receptor and ligand (PD-1 or PD-L1) has shown activity in early phase clinical trials using single or combination checkpoint inhibitors. The anti PD-1 antibody, nivolumab, was compared to placebo in a phase 3 study enrolling patients with refractory gastric cancer. Compared to placebo, nivolumab was associated with modest improvement in median OS. (5.26 months vs 4.14 months; HR 0·63; 95% CI 0·51 to 0·78; P < 0·0001). Based on this study, nivolumab obtained approval for the treatment of advanced gastric cancer that has progressed after conventional chemotherapy in Japan. Pembrolizumab, another anti PD-1 antibody, was similarly studied in 259 patients with recurrent or advanced gastric or gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) adenocarcinoma who have received 2 or more lines of chemotherapy. In this study, 143 of 259 patients had PD-L1 positive tumor and the ORR was 13.3%. PD-L1 positivity was assessed by PD-L1 IHC 22C3 pharmDx Kit (Dako) with PD-L1 positivity based on a combined positive score (CPS) ≥ 1. CPS was determined by the number of PD-L1 staining cells (tumor cells, lymphocytes, macrophages) divided by total number of tumor cells evaluated, multiplied by 100. The duration of response among the 19 responding patients ranged from 2.8 to 19.4 months with responses being 6 months or longer in 11 (58%) patients and 12 months or longer in 5 (26%) patients. Based on these results, pembrolizumab obtained FDA-approval for the treatment of PD-L1 positive recurrent or advanced gastric or gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) adenocarcinoma who have received 2 or more lines of chemotherapy.

As described earlier, a small percentage of patients harbor microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H) or mismatch repair deficient (dMMR) gastroesophageal tumors. The safety and efficacy of pembrolizumab was studied in 149 patients with 15 different tumor types (5 patients with gastric ca) across five single arm clinical trials. In this patient population, the ORR was 39.6% and for 78% of responders, response lasted more than 6 months. Based on this data, pembrolizumab obtained FDA-approval for MSI-H or dMMR cancers (including gastroesophageal cancers) after progression of standard treatments.

TREATMENT OF GASTRIC CANCER ACCORDING TO STAGE

Stage 0 Gastric Cancer

Stage 0 indicates gastric cancer confined to the mucosa. Based on the experience in Japan, where stage 0 is diagnosed more frequently, it has been found that more than 90% of patients treated by gastrectomy with lymphadenectomy will survive beyond 5 years. An American series has confirmed these findings. No additional perioperative therapy is necessary.

Stage I and II Gastric Cancer

1.One of the following surgical procedures is recommended for stage I and II gastric cancer:

•Distal SG (if the lesion is not in the fundus or at the cardioesophageal junction)

•Proximal SG or TG, with distal esophagectomy (if the lesion involves the cardia)

•TG (if the tumor involves the stomach diffusely or arises in the body of the stomach and extends to within 6 cm of the cardia or distal antrum)

•Regional lymphadenectomy is recommended with all of the previously noted procedures

•Splenectomy is not routinely performed

2.Postoperative chemoRT is recommended for patients with at least stage IB disease.

3.Perioperative polychemotherapy could also be considered for patients who present with at least a T2 lesion preoperatively.

Stage III Gastric Cancer

1.Radical surgery: Curative resection procedures are confined to patients who do not have extensive nodal involvement at the time of surgical exploration.

2.Postoperative chemoRT or perioperative polychemotherapy is recommended. The latter should be considered particularly for bulky tumors or with significant nodal burden.

Stage IV Gastric Cancer

Patients with Distant Metastases (M1)

All newly diagnosed patients with hematogenous or peritoneal metastases should be considered as candidates for clinical trials. For many patients, chemotherapy may provide substantial palliative benefit and occasional durable remission, although the disease remains incurable. Patients with HER2 overexpression should be treated with trastuzumab in combination with chemotherapy. Balancing the risks to benefits of therapy in any individual patient is recommended.

In approximately 50% of patients with advanced gastric cancer, the disease recurs locally or at an intraperitoneal site, and this recurrence has a negative effect on quality of life and survival. Intraperitoneal (IP) 5-FU, cisplatin, and/or mitomycin have been used at select centers. IP chemotherapy administration does not routinely alter survival and should be reserved only for clinical trial at an experienced center.

POSTSURGICAL FOLLOW-UP

Follow-up in patients after complete surgical resection should include routine history and physical, with liver function tests and CEA measurements being performed.

Follow-up in patients after complete surgical resection should include routine history and physical, with liver function tests and CEA measurements being performed.

Evaluation intervals of every 3 to 6 months for the first 3 years, then annually thereafter have been suggested.

Evaluation intervals of every 3 to 6 months for the first 3 years, then annually thereafter have been suggested.

Symptom-directed imaging and laboratory workup is indicated, without routine recommendations otherwise.

Symptom-directed imaging and laboratory workup is indicated, without routine recommendations otherwise.

If TG is not performed, annual upper endoscopy is recommended due to a 1% to 2% incidence of second primary gastric tumors.

If TG is not performed, annual upper endoscopy is recommended due to a 1% to 2% incidence of second primary gastric tumors.

Vitamin B12 deficiency develops in most TG patients and 20% of SG patients, typically within 4 to 10 years. Replacement must be administered at 1,000 mcg subcutaneously or intramuscularly every month indefinitely.

Vitamin B12 deficiency develops in most TG patients and 20% of SG patients, typically within 4 to 10 years. Replacement must be administered at 1,000 mcg subcutaneously or intramuscularly every month indefinitely.

PRIMARY GASTRIC LYMPHOMA

Gastric lymphomas are uncommon malignancies representing 3% of gastric neoplasms and 10% of lymphomas.

Classification and Histopathology

Gastric lymphomas can be generally classified as primary or secondary:

Primary gastric lymphoma (PGL) is defined as a lymphoma arising in the stomach, typically originating from mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT). PGL can spread to regional lymph nodes and can become disseminated. Most are of B-cell NHL origin, with occasional cases of T-cell and Hodgkin’s lymphoma seen. Examples of PGLs include extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of MALT type previously called low-grade MALT lymphoma, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) previously called high-grade MALT lymphoma, and Burkitt’s and Burkitt’s-like lymphoma. This section will primarily address PGLs.

Primary gastric lymphoma (PGL) is defined as a lymphoma arising in the stomach, typically originating from mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT). PGL can spread to regional lymph nodes and can become disseminated. Most are of B-cell NHL origin, with occasional cases of T-cell and Hodgkin’s lymphoma seen. Examples of PGLs include extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of MALT type previously called low-grade MALT lymphoma, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) previously called high-grade MALT lymphoma, and Burkitt’s and Burkitt’s-like lymphoma. This section will primarily address PGLs.

Secondary gastric lymphoma indicates involvement of the stomach associated with lymphoma arising elsewhere. The stomach is the most common extranodal site of lymphoma. In an autopsy series, patients who died from disseminated NHL showed involvement of the gastrointestinal tract in 50% to 60% of cases. Examples of secondary gastric lymphoma include several common advanced-stage systemic NHLs, particularly mantle cell lymphoma.

Secondary gastric lymphoma indicates involvement of the stomach associated with lymphoma arising elsewhere. The stomach is the most common extranodal site of lymphoma. In an autopsy series, patients who died from disseminated NHL showed involvement of the gastrointestinal tract in 50% to 60% of cases. Examples of secondary gastric lymphoma include several common advanced-stage systemic NHLs, particularly mantle cell lymphoma.

Epidemiology

The prevalence of PGL has been increasing over the past 20 years without a clear explanation.

The prevalence of PGL has been increasing over the past 20 years without a clear explanation.

PGL incidence rises with age, with a peak in the sixth to seventh decades with a slight male predominance.

PGL incidence rises with age, with a peak in the sixth to seventh decades with a slight male predominance.

Risk factors include H. pylori-associated chronic gastritis (particularly low-grade MALT lymphoma), autoimmune diseases, and immunodeficiency syndromes including AIDS and chronic immunosuppression.

Risk factors include H. pylori-associated chronic gastritis (particularly low-grade MALT lymphoma), autoimmune diseases, and immunodeficiency syndromes including AIDS and chronic immunosuppression.

Diagnosis

Clinical symptoms that are most common at presentation include abdominal pain, weight loss, nausea, vomiting, and early satiety. Frank bleeding is uncommon and patients rarely present with perforation. Findings on upper endoscopy are diverse and may be identical to typical adenocarcinoma.

Since PGL can infiltrate the submucosa without overlying mucosal changes, conventional punch biopsies may miss the diagnosis. Deeper biopsy techniques should be employed. If an ulcer is present, the biopsy should be at multiple sites along the edge of the ulcer crater. Specimens should be pathologically evaluated by both standard techniques to determine histology and H. pylori positivity as well as flow cytometry to determine clonality and characteristics of any infiltrating lymphocytes. The latter requires fresh tissue placed in saline, not preservative. In addition, fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) are used to test for t(11;18). This cytogenetic finding is associated with more advanced disease and relative resistance to H. pylori therapy.

Staging

Lugano staging system is commonly used for gastric lymphoma because the Ann Arbor stating system is considered to be inadequate as it does not incorporate depth of tumor invasion, which is known to affect the prognosis. Early (stage IE/IIE) disease includes a single primary lesion or multiple, noncontiguous lesions confined to the GI tract that may have local or distant nodal involvement. There is no stage III in the Lugano system. Advanced (stage IV) has disseminated nodal involvement or concomitant supradiaphragmatic involvement. Patients present with stage IE and stage IIE PGL with an equal prevalence ranging between 28% and 72%.

Presentation with high-grade and low-grade disease is also equal, with 34% to 65% of disease presenting as high-grade lymphoma and 35% to 65% presenting as low-grade lymphoma. CT scanning of the chest and abdomen is important to determine the lymphoma nodal involvement. FDG-PET scanning and bone marrow biopsy may be useful in high-grade PGL staging.

Treatment

Treatment of PGL is dependent primarily by stage and histologic grade of the lymphoma. However, given the rarity of the disease and lack of clinical trial data, treatment recommendations are based primarily on retrospective studies.

Extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of MALT type is usually of low-grade histology (40% to 50%) and confined to the stomach (70% to 80% stage IE). Very good epidemiologic data support H. pylori-induced chronic gastritis as a major etiology for this tumor. Eradication of H. pylori infection with antibiotics should be the initial standard treatment. Complete histologic regression of the lymphoma has been demonstrated in 50% to 80% of patients treated in this manner with good long-term DFS. Radiation therapy (RT) can provide durable remission for cases that relapse or are H. pylori-negative. One third of PGL is associated with the t(11;18) translocation, which has a low response to H. pylori therapy and should warrant consideration of RT as a primary treatment. More advanced stage or aggressive histologies at presentation should be treated like DLBCL.

Previously called high-grade MALT lymphoma, DLBCL is a more aggressive PGL. Eradication of H. pylori provides less reliable and durable disease control. Gastrectomy was the traditional treatment of choice; however, this appears to be no longer necessary. Five hundred eighty-nine patients with stage IE and IIE DLBCL PGL were randomized to receive surgery, surgery plus radiotherapy, surgery plus chemotherapy, or chemotherapy alone. Chemotherapy was six cycles of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (CHOP). Overall survivals at 10 years were 54%, 53%, 91%, and 96%, respectively. Late toxicity and complications were more frequent and severe in those receiving surgery. Gastric perforation or bleeding as a result of initial chemotherapy was not evident. Organ preservation has been a major advance for this disease with the use of chemotherapy.

Highly aggressive PGLs including Burkitt’s and Burkitt’s-like lymphoma have seen dramatic improvement in survival over the past decade as a result of potent chemotherapy combinations for systemic disease as well as better treatment of underlying immunodeficiency states (i.e., highly effective antiretroviral therapy for AIDS).

Suggested Readings

1.A comparison of combination chemotherapy and combined modality therapy for locally advanced gastric carcinoma. Gastrointestinal Tumor Study Group. Cancer. 1982;49:1771–1777.

2.Adachi Y, Yasuda K, Inomata M, Sato K, Shiraishi N, Kitano S. Pathology and prognosis of gastric carcinoma: well versus poorly differentiated type. Cancer. 2000;89:1418–1424.

3.Ajani JA, Rodriguez W, Bodoky G, et al. Multicenter phase III comparison of cisplatin/S-1 with cisplatin/infusional fluorouracil in advanced gastric or gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma study: the FLAGS trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1547–1553.

4.Al Batran S-E, Homann N, Schmalenberg H, et al. Perioperative chemotherapy with docetaxel, oxaliplatin, and fluorouracil/leucovorin (FLOT) versus epirubicin, cisplatin, and fluorouracil or capecitabine (ECF/ECX) for resectable gastric or gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) adenocarcinoma (FLOT4-AIO): A multicenter, randomized phase 3 trial (abstract). J Clin Oncol. 2017;35 (suppl; abstr 4004).

5.Amin M, Edge S, Greene F, et al. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. Chicago, IL: Springer; 2018.

6.Avilés A, Nambo MJ, Neri N, et al. The role of surgery in primary gastric lymphoma: results of a controlled clinical trial. Ann Surg. 2004;240:44–50.

7.Bang YJ, Van Cutsem E, Feyereislova A, et al. Trastuzumab in combination with chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for treatment of HER2-positive advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer (ToGA): a phase 3, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;376:687–697.

8.Bonenkamp JJ, Hermans J, Sasako M, et al. Extended lymph-node dissection for gastric cancer. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:908–914.

9.Cocconi G, Bella M, Zironi S, et al. Fluorouracil, doxorubicin, and mitomycin combination versus PELF chemotherapy in advanced gastric cancer: a prospective randomized trial of the Italian Oncology Group for Clinical Research. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12:2687–2693.

10.Cunningham D, Allum WH, Stenning SP, et al. Perioperative chemotherapy versus surgery alone for resectable gastroesophageal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:11–20.

11.Cunningham D, Starling N, Rao S, et al. Capecitabine and oxaliplatin for advanced esophagogastric cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:36–46.

12.Fuchs CS DT, Jang RW-J, et al. KEYNOTE-059 cohort 1: Efficacy and safety of pembrolizumab (pembro) monotherapy in patients with previously treated advanced gastric cancer (abstract). J Clin Oncol. 2017;35 (suppl; abstr 4003).

13.Fuchs CS, Tomasek J, Yong CJ, et al. Ramucirumab monotherapy for previously treated advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (REGARD): an international, randomised, multicentre, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2014;383:31–39.

14.Fuchs CS,TJ, Niedzwiecke D, et al. Postoperative adjuvant chemoradiation for gastric or gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) adenocarcinoma using epirubicin, cisplatin, and infusional (CI) 5-FU (ECF) before and after CI 5-FU and radiotherapy (CRT) compared with bolus 5-FU/LV before and after CRT: intergroup trial CALGB 80101. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:256s (abstract 4003).

15.Hallissey MT, Dunn JA, Ward LC, Allum WH. The second British Stomach Cancer Group trial of adjuvant radiotherapy or chemotherapy in resectable gastric cancer: five-year follow-up. Lancet. 1994;343:1309–1312.

16.Hecht JR, Bang YJ, Qin SK, et al. Lapatinib in combination with capecitabine plus oxaliplatin in human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive advanced or metastatic gastric, esophageal, or gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma: TRIO-013/LOGiC—a randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:443–451.

17.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, et al. Global Cancer Statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61(2):69–90.

18.Kang YK, Boku N, Satoh T, et al. Nivolumab in patients with advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer refractory to, or intolerant of, at least two previous chemotherapy regimens (ONO-4538-12, ATTRACTION-2): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017.

19.Kattan MW, Karpeh MS, Mazumdar M, Brennan MF. Postoperative nomogram for disease-specific survival after an R0 resection for gastric carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3647–3650.

20.Kelsen D, Atiq OT, Saltz L, et al. FAMTX versus etoposide, doxorubicin, and cisplatin: a random assignment trial in gastric cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1992;10:541–548.

21.Le DT, Durham JN, Smith KN, et al. Mismatch repair deficiency predicts response of solid tumors to PD-1 blockade. Science. 2017;357:409–413.

22.Lee J, Lim DH, Kim S, et al. Phase III trial comparing capecitabine plus cisplatin versus capecitabine plus cisplatin with concurrent capecitabine radiotherapy in completely resected gastric cancer with D2 lymph node dissection: the ARTIST trial. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:268–273.

23.Li J, Qin S, Xu J, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III trial of apatinib in patients with chemotherapy-refractory advanced or metastatic adenocarcinoma of the stomach or gastroesophageal junction. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:1448–1454.

24.Lordick F, Kang YK, Chung HC, et al. Capecitabine and cisplatin with or without cetuximab for patients with previously untreated advanced gastric cancer (EXPAND): a randomised, open-label phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:490–499.

25.Macdonald JS, Smalley SR, Benedetti J, et al. Chemoradiotherapy after surgery compared with surgery alone for adenocarcinoma of the stomach or gastroesophageal junction. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:725–730.

26.Marrelli D, Morgagni P, de Manzoni G, et al. Prognostic value of the 7th AJCC/UICC TNM classification of noncardia gastric cancer: analysis of a large series from specialized Western centers. Ann Surg. 2012;255:486–491.

27.Ohtsu A, Shah MA, Van Cutsem E, et al. Bevacizumab in combination with chemotherapy as first-line therapy in advanced gastric cancer: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3968–3976.

28.Sakuramoto S, Sasako M, Yamaguchi T, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy for gastric cancer with S-1, an oral fluoropyrimidine. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1810–1820.

29.Sasako M, Sakuramoto S, Katai H, et al. Five-year outcomes of a randomized phase III trial comparing adjuvant chemotherapy with S-1 versus surgery alone in stage II or III gastric cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4387–4393.

30.Satoh T, Xu RH, Chung HC, et al. Lapatinib plus paclitaxel versus paclitaxel alone in the second-line treatment of HER2-amplified advanced gastric cancer in Asian populations: TyTAN—a randomized, phase III study. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:2039–2049.

31.Smalley SR, Benedetti JK, Haller DG, et al. Updated analysis of SWOG-directed intergroup study 0116: a phase III trial of adjuvant radiochemotherapy versus observation after curative gastric cancer resection. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2327–2333.

32.Songun I, Putter H, Kranenbarg EM, Sasako M, van de Velde CJ. Surgical treatment of gastric cancer: 15-year follow-up results of the randomised nationwide Dutch D1D2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:439–449.

33.Stephens J, Smith J. Treatment of primary gastric lymphoma and gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma. J Am Coll Surg. 1998;187:312–320.

34.Van Cutsem E, Bang YJ, Feng-Yi F, et al. HER2 screening data from ToGA: targeting HER2 in gastric and gastroesophageal junction cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2015;18:476–484.

35.Van Cutsem E, Moiseyenko VM, Tjulandin S, et al. Phase III study of docetaxel and cisplatin plus fluorouracil compared with cisplatin and fluorouracil as first-line therapy for advanced gastric cancer: a report of the V325 Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4991–4997.

36.Verheij M,JE, Cats A, et al. A multicenter randomized phase III trial of neo-adjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgery and chemotherapy or by surgery and chemoradiotherapy in resectable gastric cancer: first results from the CRITICS study. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(suppl): abstr 4000.

37.Waddell T, Chau I, Cunningham D, et al. Epirubicin, oxaliplatin, and capecitabine with or without panitumumab for patients with previously untreated advanced oesophagogastric cancer (REAL3): a randomised, open-label phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:481–489.

38.Webb A, Cunningham D, Scarffe JH, et al. Randomized trial comparing epirubicin, cisplatin, and fluorouracil versus fluorouracil, doxorubicin, and methotrexate in advanced esophagogastric cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:261–267.

39.Wilke H, Muro K, Van Cutsem E, et al. Ramucirumab plus paclitaxel versus placebo plus paclitaxel in patients with previously treated advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (RAINBOW): a double-blind, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:1224–1235.

40.Wils JA, Klein HO, Wagener DJ, et al. Sequential high-dose methotrexate and fluorouracil combined with doxorubicin—a step ahead in the treatment of advanced gastric cancer: a trial of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Gastrointestinal Tract Cooperative Group. J Clin Oncol. 1991;9:827–831.

41.Worthley DL, Phillips KD, Wayte N, et al. Gastric adenocarcinoma and proximal polyposis of the stomach (GAPPS): a new autosomal dominant syndrome. Gut. 2012;61:774–779.

42.Ychou M, Boige V, Pignon JP, et al. Perioperative chemotherapy compared with surgery alone for resectable gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma: an FNCLCC and FFCD multicenter phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1715–1721.