Primary Cancers of the Liver 7

Bassam Estfan and Alok A. Khorana

INTRODUCTION

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) arises from hepatocytes and is the most common type of primary liver cancer, generally occurring in the setting of cirrhosis. It is a leading cause of global cancer death. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma arises from hepatic biliary epithelium. Secondary or metastatic cancer to the liver is the most common type of malignancy discovered in the liver. This section will focus on HCC.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Hepatocellular carcinoma is the sixth most common cancer, and second leading cause of death from cancer around the world. In the United States it is the thirteenth most common cancer but the fourth leading cause of cancer death.

Hepatocellular carcinoma is the sixth most common cancer, and second leading cause of death from cancer around the world. In the United States it is the thirteenth most common cancer but the fourth leading cause of cancer death.

The highest incidence is in Asia and Africa, correlating with prevalence of Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection. China accounts for more than 50% of global cases.

The highest incidence is in Asia and Africa, correlating with prevalence of Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection. China accounts for more than 50% of global cases.

In the United States the incidence has risen steadily since early 1980s but appears to have plateaued after 2010.

In the United States the incidence has risen steadily since early 1980s but appears to have plateaued after 2010.

•Incidence of HCC in the United States between 2008 and 2013 is 13 per 100,000 for men and 4.4 per 100,000 for women (http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/livibd.html).

•Black, Hispanics, Pacific Islanders, and American Indians have higher incidence rates than White and non-Hispanics.

Thirty-six percent of new cases are diagnosed between the ages of 55 and 65.

Thirty-six percent of new cases are diagnosed between the ages of 55 and 65.

In 2016, 39,230 new primary liver cancer cases and 27,170 deaths are expected in the United States.

In 2016, 39,230 new primary liver cancer cases and 27,170 deaths are expected in the United States.

The 5-year overall survival (OS) for all stages is 17%.

The 5-year overall survival (OS) for all stages is 17%.

ETIOLOGY

In high incidence global regions, chronic HBV infection is the major risk factor for HCC. The risk increases with cirrhosis and higher serum levels of HBV DNA.

In high incidence global regions, chronic HBV infection is the major risk factor for HCC. The risk increases with cirrhosis and higher serum levels of HBV DNA.

•HBV can lead to HCC through cirrhosis or integration into host DNA.

In lower incidence regions such as the United States, cirrhosis due to chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, alcohol abuse, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease plays a major role in hepatocellular carcinoma development.

In lower incidence regions such as the United States, cirrhosis due to chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, alcohol abuse, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease plays a major role in hepatocellular carcinoma development.

•HCV infection accounts for up to 50% of HCC cases in the United States.

•Alcoholic cirrhosis accounts for 15% of HCC cases and commonly coexists with chronic HCV infection.

Other less common etiologies include hemochromatosis, α1-antitrypsin deficiency, and aflatoxin exposure.

Other less common etiologies include hemochromatosis, α1-antitrypsin deficiency, and aflatoxin exposure.

Five-year cumulative risk of developing HCC in cirrhotic patients ranges from 5% to 30% depending on region, cause of cirrhosis, and degree of liver inflammation/cirrhosis.

Five-year cumulative risk of developing HCC in cirrhotic patients ranges from 5% to 30% depending on region, cause of cirrhosis, and degree of liver inflammation/cirrhosis.

CLINICAL FEATURES

Hepatocellular carcinoma is commonly asymptomatic and is either incidentally found, or discovered during screening in cirrhotic patients.

Hepatocellular carcinoma is commonly asymptomatic and is either incidentally found, or discovered during screening in cirrhotic patients.

Symptoms are usually a sign of advanced disease (pain, constitutional symptoms), and most accompanying symptoms are due to cirrhosis or co-existing hepatic disease.

Symptoms are usually a sign of advanced disease (pain, constitutional symptoms), and most accompanying symptoms are due to cirrhosis or co-existing hepatic disease.

HCC is usually confined to liver, but the risk of metastases increases with larger tumor size and vascular involvement.

HCC is usually confined to liver, but the risk of metastases increases with larger tumor size and vascular involvement.

•Common metastatic sites are regional lymph nodes, lung, and bone.

•There is a very small risk (<3%) of needle track seeding in abdominal wall following percutaneous biopsy.

Acute pain with large and/or superficial tumors in the liver may indicate rupture.

Acute pain with large and/or superficial tumors in the liver may indicate rupture.

DIAGNOSIS

Diagnosis is usually suspected in patients with known cirrhosis with abnormal routine screening ultrasound of the liver and/or alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) serum levels.

Diagnosis is usually suspected in patients with known cirrhosis with abnormal routine screening ultrasound of the liver and/or alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) serum levels.

The American Association for the Study of Liver Disease has issued guidelines outlining the diagnosis, staging, and management of HCC.

The American Association for the Study of Liver Disease has issued guidelines outlining the diagnosis, staging, and management of HCC.

Screening

Screening

•At-risk population should be screened with liver ultrasound every 6 months.

•Abnormal liver ultrasound should be followed by dedicated liver sectional imaging such as computed tomography scan (CT), or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

•Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) use for screening is controversial but commonly used; AFP has ineffective sensitivity and specificity for screening.

Liver Imaging

Liver Imaging

•A multiphasic CT scan or MRI is indicated when HCC is suspected (arterial, venous, delayed phases).

•Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) has devised new imaging classification system for transplant listing approval.

•HCC compatible lesions are referred to as OPTN5 lesions.

•Characteristic HCC lesions show arterial phase enhancement and venous or delayed phase washout at risk population in lesions larger than 2 cm.

•Lesions less than 1 cm should be followed every 3 months.

•Lesions between 1 and 2 cm should have a pseudo-capsule in addition to meet diagnostic criteria.

•If first imaging modality was not confirmatory (CT or MRI) and suspicion was high, a diagnosis can be made if the other imaging modality shows characteristic OPTN5 lesions.

•The United Network for Organ Sharing allows only biopsy proven or OPTN5 lesions for orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT) approval.

Liver Biopsy

Liver Biopsy

•Liver biopsy is indicated for suspicious lesions when diagnosis cannot be confirmed radiologically, or if alternative diagnoses are suspected.

•Percutaneous biopsies should be avoided as much as possible especially in those who may be candidate for OLT due to risk of needle track seeding and abdominal wall recurrence.

AFP

AFP

•The presence of a liver mass with cirrhosis and an AFP >400 ng/mL is usually indicative of HCC. This is not acceptable for OLT listing. Liver disease and cholangiocarcinoma can also elevate AFP.

•AFP is neither sensitive nor specific for diagnosis.

•AFP can be normal in up to 40% of cases.

PATHOLOGY

Hepatocellular carcinoma is the most common primary liver cancer accounting for 80% to 90%, followed by intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (10% to 20%).

Hepatocellular carcinoma is the most common primary liver cancer accounting for 80% to 90%, followed by intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (10% to 20%).

Other rare primary liver malignancies include fibrolamellar carcinoma (a subtype of HCC), hepatoblastoma, angiosarcoma, hemangiosarcoma, and epithelioid hemangioendothelioma.

Other rare primary liver malignancies include fibrolamellar carcinoma (a subtype of HCC), hepatoblastoma, angiosarcoma, hemangiosarcoma, and epithelioid hemangioendothelioma.

Although rare, liver metastases should be suspected in cirrhotic patients with liver lesions not meeting radiological characteristics of HCC.

Although rare, liver metastases should be suspected in cirrhotic patients with liver lesions not meeting radiological characteristics of HCC.

HCCs are vascular tumors and are frequently associated with micro- or macrovascular invasion.

HCCs are vascular tumors and are frequently associated with micro- or macrovascular invasion.

STAGING

Multiple staging systems have been developed for HCC.

Multiple staging systems have been developed for HCC.

Although the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM staging system is prognostic, it lacks incorporation of liver function and functional status.

Although the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM staging system is prognostic, it lacks incorporation of liver function and functional status.

Other staging systems such as Okuda, Cancer of the Liver Italian Program (CLIP), and Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) have incorporated elements pertaining to liver function.

Other staging systems such as Okuda, Cancer of the Liver Italian Program (CLIP), and Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) have incorporated elements pertaining to liver function.

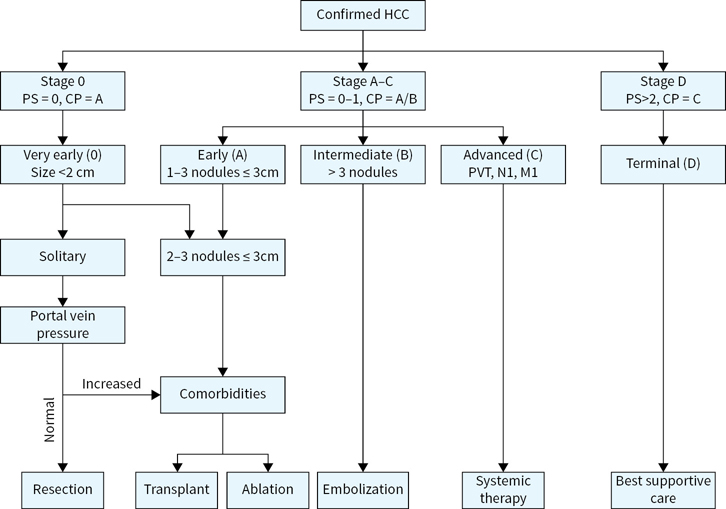

The BCLC staging system is the most widely used and incorporates elements of cancer size, number, Child-Pugh score, and performance status with implications in regards to treatment options (Fig. 7.1).

The BCLC staging system is the most widely used and incorporates elements of cancer size, number, Child-Pugh score, and performance status with implications in regards to treatment options (Fig. 7.1).

Child Pugh scoring system is key in assessment of liver health and determining management options (Table 7.1).

Child Pugh scoring system is key in assessment of liver health and determining management options (Table 7.1).

Child Pugh class corresponds to expected 1- and 2-year survival.

Child Pugh class corresponds to expected 1- and 2-year survival.

FIGURE 7.1 Barcelona clinic liver cancer (BCLC) hepatocellular carcinoma staging classification. The BCLC algorithm incorporates liver function, tumor characteristics, performance status and comorbidities in staging and treatment assignment. (Adapted from Bruix J, Sherman M. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Hepatology. 2011;53:1020–1022.)

TABLE 7.1 Child Pugh Classification

Score Attribution | 1 | 2 | 3 |

Bilirubin (mg/dL) | <2 | 2–3 | >3 |

Albumin (g/dL) | >3.5 | 2.8–3.5 | <2.8 |

INR (or PT) | <1.7 (<4) | 1.7–2.3 (4–6) | >2.3 (>6) |

Ascites | None | Mild (or medically suppressed) | Moderate to severe (or refractory) |

Encephalopathy grade | None | 1–2 | 3–4 |

Class A: score 5–6, Class B: score 7–9, Class C: score 10–15.

One and two year survival are 100% and 85% for Class A, 81% and 57% for Class B, and 45% and 35% for Class C, respectively.

INR, international normalization ratio; PT, prothrombin time.

TREATMENT

Surgery

Surgery is the main curative option for HCC whether through resection or transplantation.

Surgery is the main curative option for HCC whether through resection or transplantation.

Candidacy for surgery is determined by liver function, presence of portal hypertension, tumor burden (see Fig. 7.1), and to a certain extent anatomical location of lesions.

Candidacy for surgery is determined by liver function, presence of portal hypertension, tumor burden (see Fig. 7.1), and to a certain extent anatomical location of lesions.

Those who undergo surgery should have liver confined disease, no macrovascular invasion, and no regional lymph node involvement. Except in highly select situations, metastatic disease is a contraindication to surgery.

Those who undergo surgery should have liver confined disease, no macrovascular invasion, and no regional lymph node involvement. Except in highly select situations, metastatic disease is a contraindication to surgery.

Hepatic resection

Hepatic resection

•Resection can be curative for those with liver-confined disease without underlying cirrhosis or fibrosis.

•Cirrhotic patients without portal hypertension may be eligible for resection, but are still at risk of de novo HCC.

•Five-year survival is 50% to 70%. Factors affecting survival include size and number of lesions.

•Risk of recurrence at 5 years can be as high as 70% (60% intrahepatic metastases, 40% de novo HCC).

Liver transplantation

Liver transplantation

•Liver transplantation is the mainstay of curative management for patients with both HCC and cirrhosis.

•Candidates for transplantation should meet Milan selection criteria:

•One lesion ≤5 cm, or up to three lesions each ≤3 cm

•No macrovascular invasion or portal vein thrombosis

•No regional lymph node involvement or metastatic disease

•Liver transplantation is dependent on available cadaveric livers. Living donor transplantation is another viable option.

•For HCC within Milan criteria, OLT is associated with 4-year OS of 70% and recurrence free survival of 80%.

•In the United States, eligible patients should have OPTN5 lesions, and can only be given exception points for enlisting after a period of 6 months of controlled or stable disease.

•Locoregional control with chemoembolization is frequently used as “bridging” therapy awaiting transplantation.

•Patients with chronic viral hepatitis infections should be treated with goal of sustained viral response prior to transplantation.

•Imaging of chest, liver, and pelvis every 3 to 6 months for 2 years, then annually.

•AFP ever 3 to 6 months for 2 years then every 6 months

Locoregional treatment

Locoregional therapies for HCC can be employed with curative (ablation) or palliative intent for local control (embolization). They can also be used to maintain local control awaiting OLT.

Locoregional therapies for HCC can be employed with curative (ablation) or palliative intent for local control (embolization). They can also be used to maintain local control awaiting OLT.

Ablative therapy

Ablative therapy

•These include percutaneous ethanol injection (PEI), radiofrequency ablation (RFA), and microwave ablation (MWA).

•RFA and MWA can be done percutaneously or laparascopically.

•PEI is less commonly used in recent years.

•RFA or MWA are very effective for local control in lesions <2 cm.

•Local recurrence can be as high as 50% to 70%.

•Factors influencing recurrence include larger size, proximity to major vessels, subcapsular lesions, percutaneous approach, and ablation margin <1 cm.

•Best candidates are those with very early or early BCLC stage who are not candidate for resection.

•Needle tract seeding recurrence can occur in up to 3% after RFA, especially with repeat intervention and treatment of subcapsular lesions.

Hepatic artery embolization

Hepatic artery embolization

•Transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) and bland embolization are effective means of locoregional control of liver confined HCC, but are not considered curative interventions.

•Eighty percent of HCC vascular supply is derived from hepatic artery branches; in contrast, normal liver parenchyma receives its main vascular supply from the portal vein.

•TACE has been shown to improve survival compared to best supportive care with 2-year survival rate of 63% versus 27%, respectively.

•TACE is commonly done using drug-eluting beads (DEBs) laden with doxorubicin.

•A randomized trial of conventional TACE compared to DEBs in unresectable HCC showed better local control (44% vs. 52% at 6 months, respectively) and lower rate of toxicity in favor of DEB/TACE.

•There is continued controversy in regards to the added benefit of chemotherapy to bead therapy.

•Suitable patients are those with relatively preserved liver function (Child Pugh Class A-B), unresectable disease, “bridging” therapy prior to transplantation. Chemoembolization often requires more than one treatment for optimal local control.

•TACE may be used with the intent of “down-staging” to meet Milan criteria.

•There is no role for systemic therapy in conjunction with TACE per the SPACE phase II trial.

Radioembolization

Radioembolization

•Hepatocellular carcinoma is radiosensitive but is also located in a radiosensitive organ. Normal liver can tolerate radiation up to about 20 Gy.

•Radioembolization utilizes Yttrium-90 microspheres. Resin and glass microspheres are commercially available.

•Glass microspheres have an FDA humanitarian device exemption approval for unresectable HCC.

•A mapping hepatic artery angiogram is an important first step to rule out vascular shunting prior to therapy. Radiation pneumonitis is a major complication with large pulmonary radiation shunting.

•It is generally contraindicated in decompensated hepatic function, and if bilirubin is >2 mg/dL.

•Radiation segmentectomy is a method whereby the radiation dose is selectively delivered to one or two segments instead of the whole lobe. This allows higher radiation dose exposure leading to better tumor necrosis and local control.

•There is indication overlap with chemoembolization. Larger lesions, significant lobar involvement, or diffuse disease are usually indications for radioembolization. Deciding the best locoregional therapeutic intervention should be done in a multidisciplinary tumor board setting.

Radiation

Stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) is a precise and conformal way of delivering external radiation in high dosage to a specific area. In radiosensitive tumors SBRT has a high success rate of achieving local control.

Stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) is a precise and conformal way of delivering external radiation in high dosage to a specific area. In radiosensitive tumors SBRT has a high success rate of achieving local control.

SBRT for hepatocellular carcinoma is a plausible option in small (preferably less than 5 cm) lesions not amenable to locoregional therapy or ablation. Anatomically challenging location for ablation such as liver dome can be treated with SBRT.

SBRT for hepatocellular carcinoma is a plausible option in small (preferably less than 5 cm) lesions not amenable to locoregional therapy or ablation. Anatomically challenging location for ablation such as liver dome can be treated with SBRT.

Tumor thrombus (especially symptomatic) can also be treated with SBRT in combination with other locoregional treatment.

Tumor thrombus (especially symptomatic) can also be treated with SBRT in combination with other locoregional treatment.

In one series, local control rate with or without TACE was 96% with an overall survival rate of 67% at 3 years.

In one series, local control rate with or without TACE was 96% with an overall survival rate of 67% at 3 years.

Systemic Therapy

Systemic therapy for HCC is indicated in advanced disease not amenable to locoregional treatment, or metastatic disease. The goal of therapy is palliation with the main benefit being increase in life expectancy.

Systemic therapy for HCC is indicated in advanced disease not amenable to locoregional treatment, or metastatic disease. The goal of therapy is palliation with the main benefit being increase in life expectancy.

Patients with advanced HCC should be considered for clinical trials when possible.

Patients with advanced HCC should be considered for clinical trials when possible.

While chemotherapy has been associated with low rates of partial response in certain series, it has not been shown to improve survival.

While chemotherapy has been associated with low rates of partial response in certain series, it has not been shown to improve survival.

Sorafenib is a multikinase inhibitor with antiangiogenic properties. It targets RAF-1, BRAF, VGEFR1, 2, and 3, and PDGFR-β. It is the only FDA-approved drug for treatment of advanced HCC in the United States. It has mainly been studied in Child Pugh Class A cirrhosis.

Sorafenib is a multikinase inhibitor with antiangiogenic properties. It targets RAF-1, BRAF, VGEFR1, 2, and 3, and PDGFR-β. It is the only FDA-approved drug for treatment of advanced HCC in the United States. It has mainly been studied in Child Pugh Class A cirrhosis.

In the SHARP trial, patients with advanced HCC and Child Pugh Class A cirrhosis where randomized to placebo or sorafenib at 400 mg twice daily. Survival was significantly improved with placebo (10.7 vs. 7.9 months). The Asia-Pacific trial used a similar design in Asian population and a statistically significant improvement in survival was also noted in favor of sorafenib (6.5 vs. 4.2 months).

In the SHARP trial, patients with advanced HCC and Child Pugh Class A cirrhosis where randomized to placebo or sorafenib at 400 mg twice daily. Survival was significantly improved with placebo (10.7 vs. 7.9 months). The Asia-Pacific trial used a similar design in Asian population and a statistically significant improvement in survival was also noted in favor of sorafenib (6.5 vs. 4.2 months).

Response rates are 2% to 3%; about 70% will have stable disease at follow-up.

Response rates are 2% to 3%; about 70% will have stable disease at follow-up.

Side effects of sorafenib include fatigue, diarrhea, hypertension, mouth sores, bone marrow, and hepatic toxicity. Palmar plantar erythema (hand-foot syndrome) can occur in up to 45% of patients. At least 30% will require dose reduction due to side effects.

Side effects of sorafenib include fatigue, diarrhea, hypertension, mouth sores, bone marrow, and hepatic toxicity. Palmar plantar erythema (hand-foot syndrome) can occur in up to 45% of patients. At least 30% will require dose reduction due to side effects.

Sorafenib should be used with caution in patient with Child Pugh Class B cirrhosis.

Sorafenib should be used with caution in patient with Child Pugh Class B cirrhosis.

Other targeted therapies have been tried in HCC including sunitinib, brivanib, erlotinib, everolimus, linifanib, and ramucirumab. None have proven to be more effective or tolerable than sorafenib. Sunitinib was actually associated with worse survival.

Other targeted therapies have been tried in HCC including sunitinib, brivanib, erlotinib, everolimus, linifanib, and ramucirumab. None have proven to be more effective or tolerable than sorafenib. Sunitinib was actually associated with worse survival.

There is no adjuvant role for sorafenib after curative intent resection or ablation. The STROM trial showed no difference in recurrence-free survival between adjuvant sorafenib and placebo given up to 4 years.

There is no adjuvant role for sorafenib after curative intent resection or ablation. The STROM trial showed no difference in recurrence-free survival between adjuvant sorafenib and placebo given up to 4 years.

Sorafenib was studied in conjunction with TACE in locally advanced HCC in the phase II SPACE trial. There was no difference in time to progression between sorafenib and placebo.

Sorafenib was studied in conjunction with TACE in locally advanced HCC in the phase II SPACE trial. There was no difference in time to progression between sorafenib and placebo.

In a randomized clinical trial of regorafenib versus placebo in patients with preserved liver function who had progressive hepatocellular carcinoma on sorafenib, regorafenib was associated with statistically significant improvement in survival (10.6 vs. 7.8 months, respectively). Nivolumab is a PD-1 monoclonal antibody, which has shown activity in HCC after progression on sorafenib. It was well tolerated and was associated with response rate of 20% and a 9 months survival rate of 74%. It has been approved for advanced HCC in the second-line setting.

In a randomized clinical trial of regorafenib versus placebo in patients with preserved liver function who had progressive hepatocellular carcinoma on sorafenib, regorafenib was associated with statistically significant improvement in survival (10.6 vs. 7.8 months, respectively). Nivolumab is a PD-1 monoclonal antibody, which has shown activity in HCC after progression on sorafenib. It was well tolerated and was associated with response rate of 20% and a 9 months survival rate of 74%. It has been approved for advanced HCC in the second-line setting.

Suggested Readings

1.Brown KT, Do RK, Gonen M, et al. Randomized trial of hepatic artery embolization for hepatocellular carcinoma using doxorubicin-eluting microspheres compared with embolization with microspheres alone. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(17):2046–2053.

2.Bruix J, Qin S, Merle P, et al. Regorafenib for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who progressed on sorafenib treatment (RESORCE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10064):56–66.

3.Bruix J, Sherman M. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Hepatology. 2011;53:1020–1022.

4.Bruix J, Takayama T, Mazzaferro V, et al. Adjuvant sorafenib for hepatocellular carcinoma after resection or ablation (STORM): a phase 3, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(13):1344–1354.

5.El-Khoueiry AB, Sangro B, Yau T, et al. Nivolumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (CheckMate 040): an open-label, non-comparative, phase 1/2 dose escalation and expansion trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10088):2492–2502.

6.El-Serag HB. Hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1118–1127.

7.Hickey RM, Lewandowski RJ, Salem R. Yttrium-90 radioembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Nucl Med. 2016;46(2):105–108.

8.Lencioni R, Llovett JM, Han G, et al. Sorafenib or placebo plus TACE with doxorubicin-eluting beads for intermediate stage HCC: the SPACE trial. J Hepatol. 2016;64(5):1090–1098.

9.Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, et al. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(4)378–390.

10.Llovet JM, Schwartz M, Mazzaferro V. Resection and liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Liver Dis. 2005;25(2); 181–200.

11.Lovet JM, Real MI, Montana X, et al. Arterial embolisation or chemoembolisation versus symptomatic treatment in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;359(9319):1734–1739.

12.Mazzaferro V, Regalia E, Doci R, et al. Liver transplantation for the treatment of small hepatocellular carcinomas in patients with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(11):693–699.

13.McGlynn KA, Petrick JL, London WT. Global epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma: an emphasis on demographic and regional variability. Clin Liver Dis. 2015 May;19(2):223–238.

14.Riaz A, Gate VL, Atassi B, et al. Radiation segmentectomy: a novel approach to increase safety and efficacy of radioembolization. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;79(1):163–171.

15.Takeda A, Sanuki N, Tsurugai Y, et al. Phase 2 study of stereotactic body radiotherapy and optional transarterial chemoembolization for solitary hepatocellular carcinoma not amenable to resection and radiofrequency ablation. Cancer. 2016;122(13):2041–2049.

16.Wald C, Russo MW, Heimbach JK, et al. New OPTN/UNOS policy for liver transplant allocation: standardization of liver imaging, diagnosis, classification, and reporting of hepatocellular carcinoma. Radiology. 2013;266(2):376–382.