Jason S. Starr and Thomas J. George, Jr.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second leading cause of cancer deaths among men and women combined in the United States and is the third most common cause of cancer, separately, in men and in women.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second leading cause of cancer deaths among men and women combined in the United States and is the third most common cause of cancer, separately, in men and in women.

An estimated 135,430 cases of CRC (70% colon; 30% rectal) will be diagnosed in 2017, and over one-third will die as a result of the disease.

An estimated 135,430 cases of CRC (70% colon; 30% rectal) will be diagnosed in 2017, and over one-third will die as a result of the disease.

The lifetime risk of developing CRC for both men and women is 5%.

The lifetime risk of developing CRC for both men and women is 5%.

Surgery will cure almost 50% of all diagnosed patients; however, 40% to 50% of newly diagnosed CRC cases will eventually develop metastatic disease.

Surgery will cure almost 50% of all diagnosed patients; however, 40% to 50% of newly diagnosed CRC cases will eventually develop metastatic disease.

The incidence of colon cancer is higher in the more economically developed regions, such as the United States or Western Europe, than in Asia, Africa, or South America.

The incidence of colon cancer is higher in the more economically developed regions, such as the United States or Western Europe, than in Asia, Africa, or South America.

US incidence and mortality rates from CRC continue to decline among patients 50 years of age or older (4.5% decrease per year from 2008 to 2012). On the contrary, incidence rates have increased among patients younger than age 50 (1.8% increase per year from 2008 to 2012). The reason for this increase in younger adults is unclear.

US incidence and mortality rates from CRC continue to decline among patients 50 years of age or older (4.5% decrease per year from 2008 to 2012). On the contrary, incidence rates have increased among patients younger than age 50 (1.8% increase per year from 2008 to 2012). The reason for this increase in younger adults is unclear.

RISK FACTORS

Although certain conditions predispose patients to develop colon cancer, up to 70% of patients have no identifiable risk factors:

Age: More than 90% of colon cancers occur in patients older than 50 years.

Age: More than 90% of colon cancers occur in patients older than 50 years.

Gender: The incidence of colon cancer is similar in men and women, but rectal cancer is more prominent in men.

Gender: The incidence of colon cancer is similar in men and women, but rectal cancer is more prominent in men.

Ethnicity: The occurrence of CRC is more common in African Americans than in whites, and mortality is nearly 45% higher in African Americans compared to whites.

Ethnicity: The occurrence of CRC is more common in African Americans than in whites, and mortality is nearly 45% higher in African Americans compared to whites.

Personal history of CRC or adenomatous polyps:

Personal history of CRC or adenomatous polyps:

•Tubular adenomas (lowest risk)

•Tubulovillous adenomas (intermediate risk)

•Villous adenomas (highest risk)

Tobacco use is associated with increased incidence and mortality from CRC compared to never smokers. The association is stronger for rectal cancers.

Tobacco use is associated with increased incidence and mortality from CRC compared to never smokers. The association is stronger for rectal cancers.

Obesity: Two prospective cohort studies show a 1.5-fold increased risk of CRC in people that have a high body mass index (BMI) compared to that in normal.

Obesity: Two prospective cohort studies show a 1.5-fold increased risk of CRC in people that have a high body mass index (BMI) compared to that in normal.

Dietary factors: High-fiber, low caloric intake, and low animal fat diets may reduce the risk of cancer.

Dietary factors: High-fiber, low caloric intake, and low animal fat diets may reduce the risk of cancer.

Calcium deficiency: Daily intake of 1.25 to 2.0 g of calcium was associated with a reduced risk of recurrent adenomas in a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Oral bisphosphonate therapy for at least 1 year’s duration may also reduce CRC risk.

Calcium deficiency: Daily intake of 1.25 to 2.0 g of calcium was associated with a reduced risk of recurrent adenomas in a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Oral bisphosphonate therapy for at least 1 year’s duration may also reduce CRC risk.

Vitamin D: There is no prospective evidence that vitamin D supplementation reduces risk of colorectal adenomas or cancer although a meta-analysis of five studies showed that patients with CRC and higher levels of vitamin D had improved overall survival and disease-specific mortality.

Vitamin D: There is no prospective evidence that vitamin D supplementation reduces risk of colorectal adenomas or cancer although a meta-analysis of five studies showed that patients with CRC and higher levels of vitamin D had improved overall survival and disease-specific mortality.

Micronutrient deficiency: Selenium and vitamins E and D deficiency may increase the risk of cancer. The role of folate remains unclear.

Micronutrient deficiency: Selenium and vitamins E and D deficiency may increase the risk of cancer. The role of folate remains unclear.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): IBD is associated with a 2.9-fold increase risk of CRC. The risk of CRC is associated with duration of IBD.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): IBD is associated with a 2.9-fold increase risk of CRC. The risk of CRC is associated with duration of IBD.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: An American Cancer Society study reported 40% lower mortality in regular aspirin users, and similar reductions in mortality were seen in prolonged nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use in patients with rheumatologic disorders. The cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitor celecoxib is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for adjunctive treatment of patients with familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP). Chemoprevention with selective COX-2 inhibitors must be balanced against increased cardiovascular risks.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: An American Cancer Society study reported 40% lower mortality in regular aspirin users, and similar reductions in mortality were seen in prolonged nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use in patients with rheumatologic disorders. The cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitor celecoxib is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for adjunctive treatment of patients with familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP). Chemoprevention with selective COX-2 inhibitors must be balanced against increased cardiovascular risks.

Family history: 80% of colon cancer cases are diagnosed in the absence of a positive family history. In the general population, if one first-degree relative develops cancer, it increases the relative risk for other family members to 1.72, and if two relatives are affected, the relative risk increases to 2.75. Increased risk is also observed when a first-degree relative develops an adenomatous polyp before age 60. True hereditary forms of cancer account for only 6% of CRCs.

Family history: 80% of colon cancer cases are diagnosed in the absence of a positive family history. In the general population, if one first-degree relative develops cancer, it increases the relative risk for other family members to 1.72, and if two relatives are affected, the relative risk increases to 2.75. Increased risk is also observed when a first-degree relative develops an adenomatous polyp before age 60. True hereditary forms of cancer account for only 6% of CRCs.

FAMILIAL CANCER SYNDROMES

Familial Adenomatous Polyposis

FAP is an autosomal-dominant inherited syndrome with more than 90% penetrance, manifested by hundreds of polyps developing by late adolescence. The risk of developing invasive cancer over time is virtually 100%. Germline mutations in the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene on chromosome 5q21 have been identified. The loss of the APC gene results in altered signal transduction with increased transcriptional activity of β-catenin. Several FAP variants with extraintestinal manifestations also exist:

Attenuated FAP: This variant generates flat adenomas that arise at an older age. Mutations tend to occur in the proximal and distal portions of the APC gene.

Attenuated FAP: This variant generates flat adenomas that arise at an older age. Mutations tend to occur in the proximal and distal portions of the APC gene.

Gardner’s syndrome: Associated with desmoid tumors, osteomas, lipomas, and fibromas of the mesentery or abdominal wall.

Gardner’s syndrome: Associated with desmoid tumors, osteomas, lipomas, and fibromas of the mesentery or abdominal wall.

Turcot’s syndrome: Involves tumors (esp. medulloblastoma) of the central nervous system.

Turcot’s syndrome: Involves tumors (esp. medulloblastoma) of the central nervous system.

Peutz–Jeghers syndrome: Includes non-neoplastic hamartomatous polyps throughout the gastrointestinal tract and perioral melanin pigmentation.

Peutz–Jeghers syndrome: Includes non-neoplastic hamartomatous polyps throughout the gastrointestinal tract and perioral melanin pigmentation.

Juvenile polyposis: Associated with hamartomas in colon, small bowel, and stomach.

Juvenile polyposis: Associated with hamartomas in colon, small bowel, and stomach.

Hereditary Nonpolyposis Colorectal Cancer (Lynch Syndrome)

The Lynch syndromes, named after Henry T. Lynch, include Lynch I or the colonic syndrome, which is an autosomal-dominant trait characterized by distinct clinical features, including proximal colon involvement, mucinous or poorly differentiated histology, pseudodiploidy, and the presence of synchronous or metachronous tumors. Patients develop colon cancer before 50 years, with a lifetime risk of cancer approximating 75%. In Lynch II or the extracolonic syndrome, individuals are susceptible to malignancies in the endometrium, ovary, stomach, hepatobiliary tract, small intestine, and genitourinary tract.

The Amsterdam criteria (3-2-1 rule) were established to identify potential kindreds and include the following:

Histologically verified CRC in at least three family members, one being a first-degree relative of the other two members

Histologically verified CRC in at least three family members, one being a first-degree relative of the other two members

CRC involving at least two successive generations

CRC involving at least two successive generations

At least one family member being diagnosed by 50 years

At least one family member being diagnosed by 50 years

Inclusion of extracolonic tumors and clinicopathologic and age modifications was introduced by the Bethesda criteria in 1997 and subsequently revised to account for microsatellite instability (MSI). Lynch syndrome is characterized by germline defects in DNA mismatch–repair genes (e.g., hMLH1, hMSH2, hMSH6, and hPMS2). These defects result in alterations to the length of microsatellites, segments of DNA with repeating nucleotide sequences, thus making them unstable and detectable in diagnostic assays. This MSI can be identified in virtually all Lynch syndrome kindred and in approximately 15% of sporadic CRCs.

SCREENING

Several professional societies have developed screening guidelines for the early detection of colon cancer. There are a number of early detection tests for colon cancer in average-risk asymptomatic patients. The American Cancer Society and US Preventative Service Task Force (USPSTF) screening guidelines (Table 9.1) are the most widely cited. The USPSTF does not endorse one test over the other, only that some form of recommended screening be done. Beginning at age 50, both men and women should discuss the full range of testing options with their physician. Any positive or abnormal screening test should be followed up with colonoscopy. Individuals with a family or personal history of colon cancer or polyps, or a history of chronic IBD, should be tested earlier and possibly more often.

TABLE 9.1 Recommended Colorectal Cancer Screening Guidelines for Asymptomatic Average-Risk Individuals Beginning at Age 50, All Patients at Average Risk of Colorectal Cancer Should Have One of the Screening Options Listed Below.a

Test | Frequency |

Guaiac-based fecal occult blood test (gFOBT) or fecal immunochemical test (FIT) | Every year |

Multitarget stool DNA | Every 3 y |

Colonoscopyb | Every 10 y |

Flexible sigmoidoscopy | Every 5 y |

Flexible sigmoidoscopy with FIT | Flex sigmoidoscopy every 10 y, FIT every year |

CT colonography (virtual colonoscopy) | Every 5 y |

a2016 USPSTF Recommendations did not specify which screening approach is preferred.

bColonoscopy should be done if the fecal blood test shows blood in the stool or if sigmoidoscopy shows a polyp. This colonoscopy is considered a screening completion colonoscopy.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

More than 90% of CRCs are adenocarcinomas, the focus of this chapter. Other primary cancers of the colon and rectum include Kaposi’s sarcoma, non-Hodgkin lymphomas, small cell carcinoma, and carcinoid tumors. Metastases to the large bowel can rarely occur with melanoma, ovarian, and gastric cancer.

Colon carcinogenesis involves progression from hyperproliferative mucosa to polyp formation, with dysplasia, and transformation to noninvasive lesions and subsequent tumor cells, with invasive and metastatic capabilities. CRC is a unique model of multistep carcinogenesis resulting from the accumulation of multiple genetic alterations. Stage-by-stage molecular analysis has revealed that this progression involves several types of genetic instability, including loss of heterozygosity, with chromosomes 8p, 17p, and 18q representing the most common chromosomal losses. The 17p deletion accounts for loss of p53 function, and 18q contains the tumor-suppressor genes deleted in colon cancer (i.e., DCC) and the gene deleted in pancreatic 4 (i.e., DPC4).

Colon carcinogenesis also occurs as a consequence of defects in the DNA mismatch–repair system (dMMR). The loss of hMLH1 and hMSH2, predominantly, in sporadic cancers leads to accelerated accumulation of additions or deletions in DNA. This MSI contributes to the loss of growth inhibition mediated by transforming growth factor-β due to a mutation in the type II receptor. Mutations in the APC gene on chromosome 5q21 are responsible for FAP and are involved in cell signaling and in cellular adhesion, with binding of β-catenin. Alterations in the APC gene occur early in tumor progression. Mutations in the proto-oncogene ras family, including K-ras and N-ras, are important for transformation and also are common in early tumor development.

DIAGNOSIS

Signs and Symptoms

The presentation of CRC can include abdominal pain, which is typically intermittent and vague, weight loss, early satiety, and/or fatigue. Bowel changes may be noted for left-sided colon and rectal cancers, including constipation, decreased stool caliber (pencil stools), and tenesmus. Bowel obstruction or perforation is less common. Unusual presentations include deep venous thrombosis, nephrotic-range proteinuria, and Streptococcus bovis bacteremia with or without endocarditis. The clinical finding of iron deficiency in the absence of an overt source should prompt a diagnostic endoscopic workup.

Diagnostic Evaluation

Endoscopic studies provide histologic information, potential therapeutic intervention, and overall greater sensitivity and specificity.

Endoscopic studies provide histologic information, potential therapeutic intervention, and overall greater sensitivity and specificity.

CEA elevations occur in non–cancer-related conditions, reducing the specificity of CEA measurements alone in the initial detection of colon cancer.

CEA elevations occur in non–cancer-related conditions, reducing the specificity of CEA measurements alone in the initial detection of colon cancer.

Basic laboratory studies including complete blood count, electrolytes, liver and renal function tests, and CT scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis with IV contrast are useful in initial cancer diagnosis and staging.

Basic laboratory studies including complete blood count, electrolytes, liver and renal function tests, and CT scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis with IV contrast are useful in initial cancer diagnosis and staging.

In colon cancers, CT scan sensitivity for detecting distant metastasis is higher (75% to 87%) than for detecting nodal involvement (45% to 73%) or the extent of local invasion (~50%).

In colon cancers, CT scan sensitivity for detecting distant metastasis is higher (75% to 87%) than for detecting nodal involvement (45% to 73%) or the extent of local invasion (~50%).

FDG-PET scanning adds little over conventional imaging in the initial staging and diagnosis of CRC in the absence of abnormalities seen on CT scan.

FDG-PET scanning adds little over conventional imaging in the initial staging and diagnosis of CRC in the absence of abnormalities seen on CT scan.

Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can help determine the status of suspicious lesions in the liver as well as the characteristics (not just size) of rectal cancers.

Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can help determine the status of suspicious lesions in the liver as well as the characteristics (not just size) of rectal cancers.

For rectal cancers, endoscopic rectal ultrasound (ERUS) is a valuable tool in the preoperative evaluation, with high accuracy of determining the extent of the primary tumor (sensitivity 63% to 95%) and perirectal nodal status (sensitivity 63% to 82%). However, as compared to ERUS, MRI can better visualize proximal tumors and allow for noninvasive evaluation of circumferential (i.e., obstructing) tumors. Additionally, MRI can better characterize the perirectal lymph nodes and approximate the tumor to the pelvic side wall.

For rectal cancers, endoscopic rectal ultrasound (ERUS) is a valuable tool in the preoperative evaluation, with high accuracy of determining the extent of the primary tumor (sensitivity 63% to 95%) and perirectal nodal status (sensitivity 63% to 82%). However, as compared to ERUS, MRI can better visualize proximal tumors and allow for noninvasive evaluation of circumferential (i.e., obstructing) tumors. Additionally, MRI can better characterize the perirectal lymph nodes and approximate the tumor to the pelvic side wall.

STAGING

The eighth edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging for CRC uses the TNM classification system. The Dukes or MAC staging systems are only of historic interest. The tumor designation, or T stage, defines the extent of bowel wall penetration including invasion into the submucosa (T1), muscularis propria (T2), pericolic tissue (T3), visceral peritoneal surface (T4a), or an adjacent organ or other structure (T4b). At least 12 lymph nodes must be sampled for accurate staging and represents an important quality control metric. The number of regional nodes involved varies from 1 to 3 (N1a/b) to 4 or more (N2a/b). N1c includes direct tumor deposits in the subserosa, mesentery, or nonperitonealized pericolic or perirectal tissues without regional nodal metastasis. Metastases confined to one organ or site (M1a) have a better prognosis than metastases confined to the peritoneum or multiple sites (M1b).

PROGNOSIS

Pathologic stage remains the most important determinant of prognosis (Table 9.2) with similar outcomes for both colon and rectal cancers in the modern era. Other prognostic variables proposed to be associated with an unfavorable outcome include advanced age of the patient, high tumor grade, perineural or lymphovascular invasion, high serum CEA level, and bowel obstruction or perforation at the time of presentation.

Biochemical and molecular markers such as elevated thymidylate synthase, p53 mutations, loss of heterozygosity of chromosome 18q (DCC gene), and lack of CDX2 expression are also proposed as prognostic. The latter appears to portend for a worse 5-year disease-free survival (DFS) in patients with stage II and III colon cancers, yet adjuvant chemotherapy was associated with a significant DFS improvement upon retrospective analysis. However, a defective DNA mismatch–repair system (e.g., altered MLH1, MSH2; associated with Lynch syndrome) is associated with an improved outcome for patients with early stage, node-negative disease. Regardless of stage, the presence of a B-raf (V600E) mutation has been associated with a worse prognosis. The presence of a somatic B-raf mutation in the setting of MLH1 absence precludes the germline diagnosis of Lynch syndrome. There are multiple commercially available multigene assays that have been developed to help define the risk of recurrence and prognosis for stage II CRC (see “Adjuvant Chemotherapy Regimens for Colon Cancer”).

Biochemical and molecular markers such as elevated thymidylate synthase, p53 mutations, loss of heterozygosity of chromosome 18q (DCC gene), and lack of CDX2 expression are also proposed as prognostic. The latter appears to portend for a worse 5-year disease-free survival (DFS) in patients with stage II and III colon cancers, yet adjuvant chemotherapy was associated with a significant DFS improvement upon retrospective analysis. However, a defective DNA mismatch–repair system (e.g., altered MLH1, MSH2; associated with Lynch syndrome) is associated with an improved outcome for patients with early stage, node-negative disease. Regardless of stage, the presence of a B-raf (V600E) mutation has been associated with a worse prognosis. The presence of a somatic B-raf mutation in the setting of MLH1 absence precludes the germline diagnosis of Lynch syndrome. There are multiple commercially available multigene assays that have been developed to help define the risk of recurrence and prognosis for stage II CRC (see “Adjuvant Chemotherapy Regimens for Colon Cancer”).

TABLE 9.2 Prognosis by Stage for Colorectal Cancers

Stage | 5-Y Observed Survival Rate (%) |

I | 74 |

IIA | 65 |

IIB | 58 |

IIC | 37 |

IIIA | 73 |

IIIB | 45 |

IIIC | 28 |

IV | 6 |

Adapted from Gunderson LL, Jessup JM, Sargent DJ, et al. Revised TN categorization for colon cancer based on national survival outcomes data. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(2):264–271.

MANAGEMENT ALGORITHM

Surgery

For colon cancers, the primary curative intervention requires en bloc resection of the involved bowel segment and mesentery, with pericolic and intermediate lymphadenectomy for both staging and therapeutic intent. Negative proximal, distal, and lateral surgical margins are of paramount importance. Laparoscopic techniques adhering to these surgical principles are an acceptable option.

For colon cancers, the primary curative intervention requires en bloc resection of the involved bowel segment and mesentery, with pericolic and intermediate lymphadenectomy for both staging and therapeutic intent. Negative proximal, distal, and lateral surgical margins are of paramount importance. Laparoscopic techniques adhering to these surgical principles are an acceptable option.

For rectal cancers, en bloc resection of the primary tumor with negative proximal, distal, and radial margins is critical as well as a sharp dissection of the mesorectum (total mesorectal excision) to optimally reduce local recurrence. The location of the tumor in relation to the anal sphincter is the primary determinant in a low anterior resection (LAR) versus an abdominoperineal resection (APR). The latter generates a permanent colostomy. For highly selected early-stage rectal cancer cases, transanal endoscopic microsurgery may be considered.

For rectal cancers, en bloc resection of the primary tumor with negative proximal, distal, and radial margins is critical as well as a sharp dissection of the mesorectum (total mesorectal excision) to optimally reduce local recurrence. The location of the tumor in relation to the anal sphincter is the primary determinant in a low anterior resection (LAR) versus an abdominoperineal resection (APR). The latter generates a permanent colostomy. For highly selected early-stage rectal cancer cases, transanal endoscopic microsurgery may be considered.

Surgical intervention is indicated if polypectomy pathology reveals muscularis mucosa involvement or penetration.

Surgical intervention is indicated if polypectomy pathology reveals muscularis mucosa involvement or penetration.

Surgical palliation may include colostomy or even resection of metastatic disease for symptoms of acute obstruction or persistent bleeding.

Surgical palliation may include colostomy or even resection of metastatic disease for symptoms of acute obstruction or persistent bleeding.

Radiation Therapy

Routine administration of abdominal radiotherapy (RT) is limited by bowel-segment mobility, adjacent small bowel toxicity, previous surgery with adhesion formation, and other medical comorbidities.

Routine administration of abdominal radiotherapy (RT) is limited by bowel-segment mobility, adjacent small bowel toxicity, previous surgery with adhesion formation, and other medical comorbidities.

Local control and improved DFS have been reported in retrospective series of patients with T4 lesions or perforations, nodal disease, and subtotal resections, who have been treated with 5,000 to 5,400 cGy directed at the primary tumor bed and draining lymph nodes. However, there are no randomized data to support the routine use of RT in the management of colon cancer.

Local control and improved DFS have been reported in retrospective series of patients with T4 lesions or perforations, nodal disease, and subtotal resections, who have been treated with 5,000 to 5,400 cGy directed at the primary tumor bed and draining lymph nodes. However, there are no randomized data to support the routine use of RT in the management of colon cancer.

In contrast, RT is routinely utilized in rectal cancers to reduce local recurrence and improve resectability. RT can also be useful for palliation of pain and bleeding in rectal cancer.

In contrast, RT is routinely utilized in rectal cancers to reduce local recurrence and improve resectability. RT can also be useful for palliation of pain and bleeding in rectal cancer.

Pivotal Adjuvant Chemotherapy Studies for Colon Cancer

Establishing Benefit and Duration of Adjuvant Fluoropyrimidine Therapy

The Intergroup 0035 trial is of historic importance because it demonstrated that the use of 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) and levamisole (Lev) reduced the relapse rate by 41% and overall cancer mortality by 33%. This study resulted in the National Institutes of Health consensus panel recommending that 5-FU-based adjuvant therapy be administered to all patients with resected stage III colon cancer.

The subsequent Intergroup 0089 trial randomized 3,759 patients with stage II or III disease to one of four therapeutic arms. The results demonstrated that the 5-FU- and leucovorin (LV)-containing schedules (Mayo Clinic and Roswell Park regimens) were equivalent without the need for Lev. A 6-month schedule of the 5-FU and LV was similar to a protracted 12 months of therapy.

Utilization of an oral fluoropyrimidine (capecitabine) was evaluated in patients with stage III disease. Capecitabine (1,250 mg/m2 b.i.d. for 14 days, every 3 weeks) was compared with the Mayo Clinic bolus of 5-FU and LV. The study was designed to demonstrate equivalency, with a primary endpoint of 3-year DFS. The capecitabine (cape) arm was non-inferior and demonstrated a trend toward DFS superiority (64% vs. 60%; HR 0.87; 95% CI, 0.75 to 1.00; P = 0.0526). Toxicity was improved in cape arm in all categories except hand–foot syndrome (HFS). A 3-year DFS endpoint was chosen because a retrospective analysis of more than 20,000 patients treated with 5-FU demonstrated equivalency to the conventional 5-year OS benchmark.

Intensifying Adjuvant Chemotherapy

With adjuvant fluoropyrimidine monotherapy well established, studies began testing the potential benefit of polychemotherapy. In Europe, 2,246 patients with stage II (40%) and III disease were treated with infusional 5-FU with LV modulation versus the same combination with oxaliplatin (FOLFOX4) every 2 weeks for 6 months, demonstrated a 3-year DFS benefit favoring the FOLFOX4 combination over standard 5-FU with LV (78.2% vs. 72.9%; HR 0.77; 95% CI, 0.65 to 0.92; P = 0.002). With a median 6-year follow-up, the OS advantage was confirmed in the patients with stage III disease (72.9% vs. 68.7%; HR 0.80; 95% CI, 0.65 to 0.97; P = 0.023). No difference in OS was seen in the stage II population. Treatment with FOLFOX4 was well tolerated, with 41% patients having grade 3 and 4 neutropenia, only 0.7% being associated with fever. Anticipated grade 3 peripheral neuropathy or paresthesias were observed (12%), which almost entirely resolved two years later (persisted in only 0.7% of patients).

The addition of oxaliplatin to three cycles of adjuvant Roswell Park 5-FU with LV (FLOX) was evaluated in 2,407 stage II (30%) and III patients. The combination improved 3-year DFS (76.1% vs. 71.8%; HR 0.80; 95% CI, 0.69 to 0.93; P = 0.003). Grade 3 diarrhea (38%) and peripheral neuropathy (8%) were significantly worse with FLOX without any difference in treatment-related mortality. MOSAIC and C-07 established doublet adjuvant chemotherapy with fluoropyrimidine and oxaliplatin as a standard of care.

While 6 months of adjuvant therapy is currently the standard of care for adjuvant therapy, an ongoing global study (IDEA Study) is assessing the benefit of 3 versus 6 months of FOLFOX or CAPOX (capecitabine and oxaliplatin) chemotherapy in completely resected stage III patients. This potential practice changing study should have early results available in 2017.

Unlike oxaliplatin, at least three studies failed to confirm a benefit for the use of adjuvant irinotecan. CALGB 89803 was a study of irinotecan with bolus 5-FU and LV (IFL) versus weekly 5-FU in patients with stage III disease. Increased grade 3 and 4 neutropenia and early deaths were observed in the experimental arm, and a higher number of patients withdrew from the study. Overall, IFL was not better than the 5-FU and LV arm. The two European studies (PETACC-3 and ACCORD) together randomized over 3,500 patients to infusional 5-FU with or without irinotecan. Both studies failed to reach their primary endpoint of 3-year DFS, although toxicities were less than in the IFL study. The use of irinotecan is thus not recommended in the adjuvant setting.

Both cetuximab (cmab) and bevacizumab (bev) are biologic-targeted agents (see the metastatic CRC section) that have been shown to improve outcomes when combined with chemotherapy in metastatic CRC and have been definitively tested in the adjuvant setting.

Intergroup 0147 tested whether the addition of cmab to standard mFOLFOX6 adjuvant chemotherapy for resected stage III colon cancer improved outcomes. The protocol was amended to allow only patients with wild-type K-ras tumors to be eligible. The study terminated early after a second interim analysis demonstrated no benefit when adding cmab. Three-year DFS for patients with wild-type K-ras was 71.5% with mFOLFOX plus cmab and 74.6% with mFOLFOX alone (HR 1.21; 95% CI, 0.98 to 1.49; P = 0.08), suggesting a trend toward harm. There were no subgroups that benefitted from cmab, with increased toxicity and greater detrimental differences in all outcomes in patients aged greater than 70.

The addition of bev to mFOLFOX6 was tested in NSABP C-08. This randomized phase III trial assessed DFS in stage II (25%) and III patients. Bev was administered for 6 months concurrently with chemotherapy and then continued for an additional 6 months beyond (total of 1 year of biologic therapy). mFOLFOX6 plus bev did not significantly improve 3-year DFS compared to mFOLFOX6 (77.4% vs. 75.5%; HR 0.89; 95% CI, 0.76 to 1.04; P = 0.15). However, survival curve analysis suggested a time-dependent improvement in DFS with maximal separation of the curves occurring at 15 months, which correlated with 1 year of bev treatment followed by 3 months off drug. This benefit disappeared with time. No OS benefit, unexpected toxicity, or difference in patterns of relapse was seen. A study testing the benefit of expanded duration suppression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in high risk stage III colon cancer patients using regorafenib or placebo after completion of standard adjuvant therapy is ongoing.

The AVANT trial also tested bev in a three-arm study that randomized 3,451 patients with high-risk stage II (17%) or stage III colon cancer to either FOLFOX4, FOLFOX4 plus bev, or CAPOX plus bev. The 3-year DFS was not significantly different between the groups with 5-year OS hazard ratio for FOLFOX 4 plus bev versus FOLFOX4 (HR 1.27; 95% CI, 1.03 to 1.57; P = 0.02), and CAPOX plus bev versus FOLFOX4 (HR 1.15; 95% CI 0.93 to 1.42; P = 0.21) suggesting a potential detriment.

Adjuvant Chemotherapy Regimens for Stage III Colon Cancer

Based on these studies, 6 months of adjuvant chemotherapy is recommended for all patients with stage III colon cancer. Several acceptable options exist (Table 9.3), with combination regimens offering increased efficacy and modest toxicity. Ongoing studies are assessing whether shorter duration adjuvant therapy is just as beneficial. The use of irinotecan or biologic-targeted therapies in the adjuvant setting is not recommended outside of a clinical trial. Adjuvant chemotherapy should be started within 8 weeks of surgery with data supporting that a delay beyond 2 months may compromise the effectiveness of adjuvant treatment.

TABLE 9.3 Acceptable Adjuvant Chemotherapy Regimens for Stage III Colon Cancer

Name | Regimen and Dose | Repeated (d) | Total Cycles |

Mayo Clinic | LV 20 mg/m2/d IV followed by | 28 | 6 |

5-FU 425 mg/m2/d IV days 1–5 | |||

Roswell Park | LV 500 mg/m2 IV followed by | 8 wk | 3–4 |

5-FU 500 mg/m2 IV weekly × 6 | |||

Capecitabine | 1,250 mg/m2 PO twice daily × 14 d | 21 | 8 |

FOLFOX4 | Oxaliplatin 85 mg/m2 IV on day 1 followed by | 14 | 12 |

LV 200 mg/m2/d IV on days 1 and 2 followed by | |||

5-FU 400 mg/m2/d IV on days 1 and 2 followed by | |||

5-FU 600 mg/m2/d CIVI for 22 h on days 1 and 2 | |||

FOLFOX6 | Oxaliplatin 85–100 mg/m2 IV on day 1 followed by | 14 | 12 |

LV 400 mg/m2/d IV on day 1 followed by | |||

5-FU 400 mg/m2/d IV on day 1 followed by | |||

5-FU 2,400 mg/m2 CIVI for 46 h | |||

FLOX | LV 500 mg/m2 IV followed by | 8 wk | 3 |

5-FU 500 mg/m2 IV on days 1, 8, 15, 22, 29, 36 and | |||

Oxaliplatin 85 mg/m2 IV on days 1, 15, and 29 | |||

CAPOX | Oxaliplatin 100–130 mg/m2 IV on day 1 | 21 | 8 |

Capecitabine 1,000 mg/m2 PO twice daily on days 1–14 |

There is no role for biologic-targeted therapy or irinotecan-containing regimens in the adjuvant setting at this time.

LV, leucovorin; IV, intravenous; 5-FU, 5-fluorouracil; CIVI, continuous intravenous infusion.

Adjuvant Chemotherapy for Stage II Colon Cancer

Despite the 75% 5-year survival with surgery alone, some patients with stage II disease have a higher risk of relapse, with outcomes being similar to those of node-positive patients. Adjuvant chemotherapy provides up to 33% relative risk reduction in mortality, resulting in an absolute treatment benefit of approximately 5%.

Several analyses have reported varying outcomes in patients with stage II disease who received adjuvant treatment:

The National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) summary of protocols (C-01 to C-04) of 1,565 patients with stage II disease reported a 32% relative reduction in mortality (cumulative odds, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.50 to 0.92; P = 0.01). This reduction in mortality translated into an absolute survival advantage of 5%.

The National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) summary of protocols (C-01 to C-04) of 1,565 patients with stage II disease reported a 32% relative reduction in mortality (cumulative odds, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.50 to 0.92; P = 0.01). This reduction in mortality translated into an absolute survival advantage of 5%.

A meta-analysis by Erlichman et al. detected a nonsignificant 2% benefit (82% vs. 80%; P = 0.217) in 1,020 patients with high-risk T3 and T4 cancer treated with 5-FU and LV for 5 consecutive days.

A meta-analysis by Erlichman et al. detected a nonsignificant 2% benefit (82% vs. 80%; P = 0.217) in 1,020 patients with high-risk T3 and T4 cancer treated with 5-FU and LV for 5 consecutive days.

Schrag et al. reviewed Medicare claims for chemotherapy within the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database and identified 3,700 patients with resected stage II disease among whom 31% received adjuvant treatment. No survival benefit was detected with 5-FU compared to surgery alone (74% vs. 72%) even with patients considered to be at high risk because of obstruction, perforation, or T4 lesions.

Schrag et al. reviewed Medicare claims for chemotherapy within the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database and identified 3,700 patients with resected stage II disease among whom 31% received adjuvant treatment. No survival benefit was detected with 5-FU compared to surgery alone (74% vs. 72%) even with patients considered to be at high risk because of obstruction, perforation, or T4 lesions.

The Quasar Collaborative Group study reported an OS benefit of 3.6% in 3,239 patients (91% Dukes B colon cancer) prospectively randomized to chemotherapy versus surgery alone. With a median follow-up of 5.5 years, the risk of recurrence (HR 0.78; 95% CI, 0.67 to 0.91; P = 0.001) and death (HR 0.82; 95% CI, 0.70 to 0.95; P = 0.008) favored 5-FU and LV chemotherapy.

The Quasar Collaborative Group study reported an OS benefit of 3.6% in 3,239 patients (91% Dukes B colon cancer) prospectively randomized to chemotherapy versus surgery alone. With a median follow-up of 5.5 years, the risk of recurrence (HR 0.78; 95% CI, 0.67 to 0.91; P = 0.001) and death (HR 0.82; 95% CI, 0.70 to 0.95; P = 0.008) favored 5-FU and LV chemotherapy.

In the MOSAIC study, FOLFOX4 chemotherapy showed nonsignificant benefits in DFS over 5-FU and LV in patients with stage II disease (86.6% vs. 83.9%; HR 0.82; 95% CI, 0.57 to 1.17).

In the MOSAIC study, FOLFOX4 chemotherapy showed nonsignificant benefits in DFS over 5-FU and LV in patients with stage II disease (86.6% vs. 83.9%; HR 0.82; 95% CI, 0.57 to 1.17).

The American Society of Clinical Oncology Panel concluded that the routine use of adjuvant chemotherapy for patients with stage II disease could not be recommended. A review of 37 randomized controlled trials and 11 meta-analyses found no evidence of a statistically significant survival benefit with postoperative treatment of stage II patients. However, treatment should be considered for specific subsets of patients (e.g., T4 lesions, perforation, poorly differentiated histology, or inadequately sampled nodes), and patient input is critical.

The American Society of Clinical Oncology Panel concluded that the routine use of adjuvant chemotherapy for patients with stage II disease could not be recommended. A review of 37 randomized controlled trials and 11 meta-analyses found no evidence of a statistically significant survival benefit with postoperative treatment of stage II patients. However, treatment should be considered for specific subsets of patients (e.g., T4 lesions, perforation, poorly differentiated histology, or inadequately sampled nodes), and patient input is critical.

For stage II patients without high-risk features, molecular analysis can provide improved recurrence risk determination.

For stage II patients without high-risk features, molecular analysis can provide improved recurrence risk determination.

MSI is a surrogate marker for functional defects in the DNA mismatch–repair system. When these occur at a high frequency (MSI-high) in node-negative colon cancer, it portends a very favorable prognosis. There is controversy as to whether MSI-high tumors benefit from adjuvant fluoropyrimidine chemotherapy. Given the more favorable outcome and questionable response to adjuvant chemotherapy, it is recommended to test this molecular marker in all stage II patients to aid in personalized treatment decisions.

MSI is a surrogate marker for functional defects in the DNA mismatch–repair system. When these occur at a high frequency (MSI-high) in node-negative colon cancer, it portends a very favorable prognosis. There is controversy as to whether MSI-high tumors benefit from adjuvant fluoropyrimidine chemotherapy. Given the more favorable outcome and questionable response to adjuvant chemotherapy, it is recommended to test this molecular marker in all stage II patients to aid in personalized treatment decisions.

Commercially available microarray gene expression profile assays may aid in determining the risk of recurrence of stage II CRC. An example is Oncotype Dx (Genomic Health, Inc), which uses a 12-gene signature and excludes patients with MSI-high tumors. A recurrence score can be generated for an individual patient with stage II disease that classifies them as low, intermediate, or high risk. Given these tests only offer prognostic and not predictive value, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) states there is insufficient evidence to recommend use of the multigene assays to determine adjuvant therapy.

Commercially available microarray gene expression profile assays may aid in determining the risk of recurrence of stage II CRC. An example is Oncotype Dx (Genomic Health, Inc), which uses a 12-gene signature and excludes patients with MSI-high tumors. A recurrence score can be generated for an individual patient with stage II disease that classifies them as low, intermediate, or high risk. Given these tests only offer prognostic and not predictive value, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) states there is insufficient evidence to recommend use of the multigene assays to determine adjuvant therapy.

Treatment for Rectal Cancer

In contrast to colon cancer, local treatment failures after potentially curative resections represent a major clinical problem. Combined-modality chemotherapy with RT (chemoRT) is the standard therapy for patients with stage II and III rectal cancer (T3, T4, and nodal involvement).

Establishing Combined Modality Neoadjuvant Therapy as Standard of Care

A four-arm study of 1,695 post-operative patients compared 5-FU alone, 5-FU and LV combination, 5-FU and Lev combination, and 5-FU and LV and Lev combination. Two cycles of chemotherapy were administered before and after chemoRT using 5,040 cGy of external beam RT (4,500 cGy with 540 cGy boost). The chemotherapy during the RT was given as a bolus with or without LV. The DFS and OS were similar in all treatment arms, leading to the conclusion that 5-FU alone was as effective as other combinations. Subsequent studies sponsored by the North Central Cancer Treatment Group (NCCTG) demonstrated improvements in both DFS and OS when continuous infusion of 5-FU was provided during RT compared with those receiving bolus 5-FU. This survival benefit has led to continuous infusion of 5-FU during RT being considered as a standard.

The benefit of delivering chemoRT in a preoperative (neoadjuvant) fashion was evaluated by the German Rectal Study Group in 421 patients compared to 401 similar patients randomized to receive postoperative chemoRT. In both groups, 5-FU was administered in a continuous fashion during the first and fifth weeks of RT. All patients received an additional four cycles of adjuvant 5-FU after chemoRT and surgery. Results of neoadjuvant treatment provided improvement in local recurrence (6% vs. 13%; P = 0.006), but no difference in 5-year OS. Both acute toxic effects (27% vs. 40%; P = 0.001) and long-term toxicities (14% vs. 24%; P = 0.01) were less common with neoadjuvant treatment. Preoperative chemoRT followed by surgical resection with postoperative 5-FU-based chemotherapy represents a standard for patients with stage II and III rectal cancer.

NSABP R-04 was a phase III, 2 × 2 non-inferiority trial, which evaluated the substitution of oral capecitabine (cape) for infusional 5-FU (CVI 5-FU) as well as the intensification of radiosensitization by adding oxaliplatin in stage II and III rectal carcinoma. Over 1,500 patients were randomized into one of four neoadjuvant chemoRT arms. The primary endpoint for this study was local regional tumor control. The 3-year local regional tumor event rates were similar in both the cape and CVI 5-FU arms, 11.2% versus 11.8%, respectively. There was also equivalence for cape and CVI 5-FU in terms of rates of pathologic complete response (pCR) and surgical downstaging. Rates of grade 3 diarrhea were equal in both arms (11.7%). However, the addition of oxaliplatin failed to improve DFS, OS, pCR rates, surgical downstaging, or sphincter-sparing surgery. The addition of oxaliplatin did increase (16.5% vs. 6.9%) grade 3 and 4 diarrhea. This and other studies confirmed that cape is an acceptable replacement for CVI 5-FU, and that adding oxaliplatin to chemoRT offers no benefit in the neoadjuvant treatment of rectal cancer.

Sequencing of Therapy and Future Directions

Most patients with rectal cancer who recur succumb to metastatic disease yet contemporary randomized controlled trials show that 25% to 70% of the patients never receive or complete their intended adjuvant systemic chemotherapy. Thus, a “total neoadjuvant therapy” (TNT) approach to care has been developed, which provides systemic chemotherapy and chemoRT preoperatively. This has proven to be safe and feasible in early studies and has the benefit of determining therapeutic response, which can guide potential delay or elimination of certain portions of traditional treatment in an attempt to reduce morbidity. For example, a multicenter randomized phase II trial (OPRA; ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02008656) is looking at the TNT approach whereby patients with a clinical complete response (cCR) will be managed nonoperatively. This trial is based on a Brazilian report of 265 patients with resectable rectal cancers who were treated with standard neoadjuvant chemoRT, and those with a cCR were observed while all others were taken to surgery. A provocative 27% of patients maintained a cCR at one year and were spared from TME. Another important phase II/III trial (PROSPECT; ClinicalTrials.gov #NCT01515787) is randomizing low risk patients with stage II and III rectal cancer to standard of care chemoRT versus induction chemotherapy (FOLFOX for 12 weeks) followed by MRI and/or ERUS. If the tumor decreases by >20% with neoadjuvant chemotherapy alone, patients proceed to surgery without chemoRT. Post-op chemoRT is allowable should pathology support that need, but avoidance of pelvic radiotherapy for those patients with highly chemo-sensitive disease is the goal of the study design. Lastly, of interest is the randomized phase II platform TNT study (NRG GI002; ClinicalTrials.gov #NCT02921256) that has parallel, non-comparative experimental arms with a single comparative control arm of neoadjuvant chemotherapy and chemoRT. The TNT experimental arms are testing new systemic therapies and/or radiation sensitizers to improve pathologic endpoints. The first two experimental arms are assessing the potential radiosensitizing activity of the poly [ADP-ribose] polymerase (PARP) inhibitor, veliparib and the potential immunogenic capability of chemoRT with pembrolizumab, a programmed cell death-1 (PD-1) inhibitor.

Combined-Modality Options for Rectal Cancer

1.Neoadjuvant therapy (chemoRT):

Continuous infusion 5-FU (1,000 mg/m2/day) given daily for 5 days during the first and fifth week of radiation therapy OR 225 mg/m2/day given Monday through Friday continuously throughout RT .

Continuous infusion 5-FU (1,000 mg/m2/day) given daily for 5 days during the first and fifth week of radiation therapy OR 225 mg/m2/day given Monday through Friday continuously throughout RT .

Oral capecitabine 825 mg/m2 twice daily given Monday through Friday on days of RT.

Oral capecitabine 825 mg/m2 twice daily given Monday through Friday on days of RT.

All concurrent with external beam RT given in 180 cGy fractions to a total dose of 5,040 cGy.

All concurrent with external beam RT given in 180 cGy fractions to a total dose of 5,040 cGy.

2.Complete surgical resection adhering to total mesorectal excision standards.

3.Systemic therapy for 4 months (before or after from surgery):

5-FU bolus (500 mg/m2/day) on days 1 to 5 repeated every 28 days for four cycles. Given the previously discussed data for adjuvant chemotherapy regimens in colon cancer, several different regimens (see Table 9.3) may also be considered as components of the systemic chemotherapy phase of therapy in rectal cancer (e.g., fluoropyrimidine and oxaliplatin).

5-FU bolus (500 mg/m2/day) on days 1 to 5 repeated every 28 days for four cycles. Given the previously discussed data for adjuvant chemotherapy regimens in colon cancer, several different regimens (see Table 9.3) may also be considered as components of the systemic chemotherapy phase of therapy in rectal cancer (e.g., fluoropyrimidine and oxaliplatin).

FOLLOW-UP AFTER CURATIVE TREATMENT

Eighty percent of recurrences are seen within 2 years of initial therapy. The American Cancer Society recommends total colonic evaluation with either colonoscopy or double-contrast barium enema within 1 year of resection, followed every 3 to 5 years if findings remain normal. Synchronous cancers must be excluded during initial surgical resection, and metachronous malignancies in the form of polyps must be detected and excised before more malignant behavior develops.

History and physical evaluations with serum CEA measurements should be performed every 3 to 6 months for the first few years after therapy. These evaluations can be further reduced during subsequent years. Surveillance imaging should be reserved for those individuals who would be considered operable candidates if localized metastases were to be identified. Elevations of CEA postoperatively may suggest residual tumor or early metastasis. Patients with initially negative levels of CEA can subsequently exhibit positive levels; therefore, serial CEA measurements after completion of treatment may identify patients who are eligible for a curative surgery, in particular, patients with oligometastatic liver or lung recurrence.

TREATMENT FOR ADVANCED COLORECTAL CANCER

Unprecedented improvements in OS have been recognized during the past decade with systemic chemotherapy in advanced or metastatic disease. Median survival has improved from 6 months with best supportive care to approximately 30 months with incorporation of all active agents. Based upon clinical practice and supported by total cancer genomic analyses, there are no differences in the molecular characteristics or systemic management of metastatic colon or rectal cancers. Data also support proceeding with systemic therapy without surgical intervention on the primary tumor, as long as the intact primary tumor is asymptomatic. Determination of molecular profiling for RAS, BRAF, and MMR/MSI status at the time of diagnosis is now critical for optimal treatment selection.

Fluoropyrimidine-Based Chemotherapy

5-FU inhibits thymidylate synthase, an enzyme critical in thymidine generation. LV potentiates this inhibition. 5-FU and LV chemotherapy regimens in advanced CRC have objective response rates of 15% to 20%, with median survival of 8 to 12 months. Toxicity is predictable and manageable. The activity of continuous infusion of 5-FU may be equivalent to or slightly better than that of bolus 5-FU and LV and is generally well tolerated despite the inconvenience of a prolonged intravenous ambulatory infusion apparatus. Toxicities include mucositis and palmar–plantar erythrodysesthesia (HFS); however, myelosuppression is less common. Continuous infusions of 5-FU may have activity in patients who have progressed with bolus 5-FU.

Capecitabine, an oral fluoropyrimidine prodrug, undergoes a series of three enzymatic steps in its conversion to 5-FU. The final enzymatic step is catalyzed by thymidine phosphorylase, which is overexpressed in tumor tissues and upregulated by RT. Two phase III studies have compared single-agent capecitabine to the Mayo Clinic 5-FU and LV regimen and demonstrated higher response rates for the former but equivalent time to progression and median survival. Capecitabine was associated with decreased gastrointestinal and hematologic toxicities and fewer hospitalizations, but with an increased frequency of HFS and hyperbilirubinemia.

Trifluridine and tipiracil is an FDA-approved oral therapy for the treatment of metastatic CRC who have been previously treated with all other standard therapies. Trifluridine is a thymidine-based nucleoside analog while tipiracil is a thymidine phosphorylase inhibitor and in effect increases trifluridine activity. Once trifluridine is taken up in the cancer cell it is incorporated into the DNA and inhibits cell proliferation and interferes with DNA synthesis. The phase III, randomized placebo-controlled registration trial (RECOURSE) studied trifluridine and tipiracil in patients with previously treated (at least two prior lines) metastatic CRC. Results showed an improvement in median PFS (2 vs. 1.7 months; P < 0.001) and OS (7.1 vs. 5.3 months; P < 0.001) for trifluridine/tipiracil versus placebo, respectively. The main side effects of trifluridine/tipiracil were grade 3 to 4 asthenia/fatigue (7%), grade 3 anemia (18%), grade 3 to 4 neutropenia (38%), and grade 3 to 4 thrombocytopenia (5%).

Oxaliplatin

Oxaliplatin is an agent that differs structurally from other platinums in its 1,2-diaminocyclohexane (DACH) moiety, but acts similarly by generating DNA adducts. Oxaliplatin exhibits synergy with 5-FU with response rates as high as 66% even in patients who are refractory to 5-FU. Despite its unique toxicities (i.e., peripheral neuropathy, laryngopharyngeal dysesthesias, and cold hypersensitivities), oxaliplatin lacks the emetogenic and nephrogenic toxicities of cisplatin.

The North Central Cancer Treatment Group (NCCTG-9741) conducted a trial comparing first-line FOLFOX4 versus IFL versus IROX (irinotecan in combination with oxaliplatin). Higher 60-day mortality was detected in the IFL arm, resulting in a dose reduction in the protocol. The response rate, time to progression, and OS were significantly better in the FOLFOX4 arm than in the modified IFL arm. However, imbalances in the second-line chemotherapy administered to patients in this study may confound the survival differences. Approximately 60% of the oxaliplatin failures were treated with irinotecan, whereas only 24% of patients who were refractory to irinotecan received oxaliplatin. In addition, the study was not designed to address the effect of infusional 5-FU. The observed toxicities in the study were reflective of the specific drug combinations and included grade 3 or higher paresthesias (18%) in the FOLFOX arm and a 28% incidence of diarrhea in the IFL arm. Despite a higher degree of neutropenia (60% in FOLFOX vs. 40% in IFL) with FOLFOX, febrile neutropenia was significantly greater in the IFL arm. IROX also exhibited significant toxicities. Oxaliplatin was approved by the FDA for use in the first-line treatment of patients with metastatic CRC largely based on this study.

Although FOLFOX is clearly a superior regimen compared to IFL, the use of infusional 5-FU with irinotecan (FOLFIRI) may produce results similar to those seen using FOLFOX. Tournigand et al. reported an equivalent median survival of 21.5 months with FOLFIRI followed by FOLFOX and a median survival of 20.6 months with the opposite sequence (P = 0.99). Similar survival is observed in patients receiving either sequence, and both are acceptable first-line therapies for advanced disease.

Irinotecan

Irinotecan is a topoisomerase I inhibitor, with activity in advanced CRC deemed refractory to 5-FU. As a single agent, response rates as high as 20% are observed, and an additional 45% of patients achieve disease stabilization. Significant survival advantages have been shown for irinotecan as second-line therapy after 5-FU compared with supportive care or with continuous-infusion 5-FU regimens. Several schedules are typically administered with and without 5-FU; however, the cumulative data suggest that irinotecan should not be utilized with bolus 5-FU (i.e., IFL) due to excessive treatment-related mortality. Irinotecan obtained initial FDA approval based on a study comparing IFL to the 5-FU bolus Mayo Clinic regimen. A higher response rate (39% vs. 21%; P = 0.0001) and OS (14.8 vs. 12.6 months; P = 0.042) were observed favoring IFL.

Delayed-onset diarrhea is common and requires close monitoring and aggressive management (high-dose loperamide, 4 mg initially and then 2 mg every 2 hours until diarrhea stops for at least 12 hours). Neutropenia, mild nausea, and vomiting are common. This combination of toxicities can be severe and life-threatening, which was evident in NCCTG 9741 (see previous oxaliplatin section). A higher 60-day mortality was observed (4.5% vs. 1.8%), and the dose of irinotecan required reduction.

Anti-VEGF Therapies

Bevacizumab (bev) is a recombinant humanized monoclonal antibody targeting the VEGF, which blocks VEGF-induced angiogenesis by preventing it from binding to VEGF receptors. When added to IFL, bev increased the response rate (45% vs. 35%; P = 0.004) and had a longer median survival (20.3 vs. 15.6 months; P < 0.001). When added to FOLFOX in the second-line setting, response rates are again increased (23% vs. 9%; P < 0.001) along with an improvement in OS (12.9 vs. 10.8 months; P = 0.0011). Bev has been approved by the FDA for the treatment of patients with advanced CRC in combination with any intravenous 5-FU-based regimen. Two trials (ML18147, BRiTE) looked at bev beyond progression following first-line chemotherapy. Both studies showed PFS and OS advantage with continuation of bev with second line chemotherapy. This approach was further explored as a maintenance strategy. The CAIRO-3 study was a European study that enrolled 558 patients to receive “induction” chemotherapy with CAPOX plus bev for six cycles. Patients were then randomized to observation versus maintenance treatment with cape and bev. Upon progression (PFS1) patients on either observation or cape and bev were restarted on CAPOX plus bev, and the next progression (PFS2) was the primary endpoint. The maintenance group had a significantly improved PFS2 compared to observation, 11.7 versus 8.5 months, respectively (HR 0.67; 95% CI 0.56 to 0.81; P < 0.0001).

Ziv-aflibercept is a fully humanized recombinant fusion protein that blocks angiogenesis by binding to VEGF-A, VEGF-B, and placental growth factor and preventing their interaction with endogenous receptors. It is FDA approved for use in combination with FOLFIRI for second-line treatment in metastatic CRC based on results from the VELOUR study. This phase III, placebo-controlled trial randomized 1,226 metastatic patients with CRC after an oxaliplatin-based regimen to second-line therapy with FOLFIRI plus ziv-aflibercept or placebo. Median OS of FOLFIRI plus ziv-aflibercept was statistically superior to FOLFIRI (13.5 vs. 12 months; HR 0.87; 95% CI 0.713 to 0.937; P = 0.0032) as was PFS (6.9 vs. 4.7 months; P < 0.0001).

Ramucirumab is another humanized monoclonal antibody that blocks activation of VEGF receptor 2, effectively blocking the binding of VEGF-A, VEGF-C, and VEGF-D. It is FDA approved for use in combination with FOLFIRI for second-line treatment in metastatic CRC based on results from the RAISE study. This phase III, placebo-controlled trial randomized 1,072 patients with previously oxaliplatin treated metastatic CRC to FOLFIRI plus ramucirumab or placebo. The addition of ramucirumab demonstrated a median PFS improvement of 1.2 months (5.7 vs. 4.5 months; P < 0.001) and median OS improvement of 1.6 months (13.3 vs. 11.7 months; P = 0.023).

The first and currently only approved oral multikinase inhibitor for metastatic CRC is regorafenib. This agent blocks several kinases involved in angiogenic and oncogenic survival pathways including VEGFR1, VEGFR2, VEGFR3, TIE2, KIT, RET, RAF1, BRAF, PDGFR, and FGFR. The CORRECT trial randomized heavily pretreated metastatic CRC patients who progressed within 3 months after treatment with all currently available standard therapies to oral regorafenib versus placebo. Median OS was found to be improved with regorafenib compared to placebo (6.4 vs. 5 months; HR 0.77; P = 0.0052). Studies which incorporate this treatment in earlier lines of therapy are ongoing.

Anti-Epidermal Growth Factor Therapies

The epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and pathway represent another targeted approach in advanced CRC therapy. Two monoclonal antibodies are FDA approved for use in patients with metastatic CRC. Importantly, tumor EGFR positivity by IHC staining does not correlate with treatment response; however, K-ras, N-ras, and B-raf mutational status does. Both intracellular signal transduction proteins exist in either a wild-type (normal functional) or mutated (via activating mutation resulting in continuous overactivity) state. Mutations in K- and N-ras (~50% together) and B-raf (5% to 10%) have high concordance between primary and metastatic CRC tumors (in excess of 90%), with recommendations for testing these at the time of metastatic diagnosis. Of note, B-raf V600E mutations have become increasingly important in identifying a subset of CRC patients with a particularly aggressive disease associated with short PFS (4 to 6 months) and OS (9 to 14 months). Attempts to directly target this pathway with the B-raf inhibitor vemurafenib failed given unanticipated feedback through the EGFR accessory pathways. Treatments aimed at combining dual pathway targets or maximizing first-line cytotoxic regimens are under active investigation. Testing for extended ras and raf mutations is recommended and widely commercially available.

Cetuximab (cmab) is a chimerized IgG1 antibody that prevents ligand binding to the EGFR and its heterodimers through competitive displacement. Panitumumab (pmab) is a fully humanized IgG2 antibody also targeting EGFR in a similar manner. These agents both block receptor dimerization, tyrosine kinase phosphorylation, and subsequent downstream signal transduction. Both can cause a skin rash, diarrhea, hypomagnesemia, and infusion reactions, but to a less degree with pmab for the latter two toxicities. A correlation between the intensity of the skin rash and improved survival has been consistently noted with agents in this class.

Cmab was initially FDA approved based on a study in irinotecan-refractory advanced disease. Patients were randomized to the combination of cmab and irinotecan versus cmab alone with improvements in the response rate (22.9% vs. 10.8%; P = 0.0074) and time to progression (4.1 vs. 1.5 months; P < 0.0001) favoring the combination. Despite manageable toxicity, no improvements in survival outcomes were observed, but tumor resensitization to irinotecan was clearly demonstrated. Cmab is also approved for use as first-line metastatic treatment for patients with wild-type K-ras tumors. The CRYSTAL phase III trial randomized 1,217 patients to FOLFIRI with or without cmab. FOLFIRI plus cmab demonstrated a 15% relative reduction in the risk of recurrence (HR 0.85; 95% CI 0.72 to 0.99; P = 0.048) with an improvement in the median PFS (8.9 vs. 8 months). The addition of cmab produced significantly more skin reactions, diarrhea, and infusional reactions. Median progression-free survival directly correlated with increased grade of skin rash. K-ras status was available on a subgroup analysis of 540 tissue samples. Patients with wild-type K-ras had a favorable outcome on response rate, OS, and PFS (HR 0.68). However, mutated K-ras tumors were associated with a decrease in OS and response rates, particularly with cmab addition, confirming that ras mutations are a negative predictor of response to EGFR inhibition.

Panitumumab is FDA approved as monotherapy given improvement in progression-free survival over best supportive care in heavily pretreated patients (HR 0.54; 95% CI 0.44 to 0.66; P < 0.0001), although no OS advantage was noted. This agent also has data supporting improvements in PFS when combined with FOLFIRI in the second-line treatment.

PD-1 Antibody

Programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) is expressed on activated T-cells and is a negative regulator of T-cell activity when it interacts with its ligand PD-L1. As a mechanism of immune evasion, tumor cells overexpress PD-L1. Antibodies to block this interaction have been developed with varying success in a multitude of malignancies. In CRC, anti-PD-1 therapy has been most notable in tumors harboring mismatch-repair deficiency (dMMR/MSI-High). This represents about 5% of patients with metastatic CRC.

The PD-1 checkpoint inhibitor, pembrolizumab, received accelerated approval from the FDA (May 2017) for dMMR and/or MSI-H metastatic CRC who have progressed on fluoropyrimidine, oxaliplatin, or irinotecan. Approval was based on aggregate data from 149 patients (90 with CRC) with dMMR/MSI-H status. For the CRC subset, ORR was 36% with median duration of response not reached. Shortly thereafter, the FDA granted an accelerated approval (August 2017) to nivolumab with the same indication. This approval was based on preliminary results of the Checkmate-142 trial that randomized dMMR/MSI-H metastatic CRC patients to nivolumab or nivolumab and ipilimumab, an anti CTLA-4 antibody. In the 74 patients who received single agent nivolumab the ORR was 31% with median duration of response was not reached. Current clinical trials are determining the impact of moving such agents earlier in treatment paradigms and stage. It remains critical to determine the MMR/MSI status of all patients with metastatic CRC at the time of diagnosis.

CHEMOTHERAPY REGIMENS FOR METASTATIC CRC

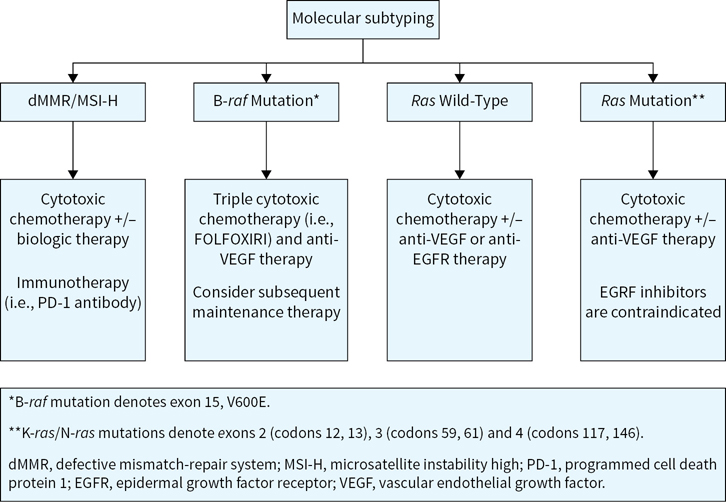

See Tables 9.3 and 9.4 and Figure 9.1. Investigations into the optimal timing and sequence of treatment combinations both with and without EGFR and VEGF inhibition continue.

TABLE 9.4 Select Chemotherapy Regimens for Advanced Colorectal Cancera

Name | Regimen and Dose | Repeated (d) |

CAPOX | Oxaliplatin 100–130 mg/m2 IV on day 1 | 21 |

Capecitabine 850–1,000 mg/m2 PO twice daily on days 1–14 | ||

Irinotecan | 300–350 mg/m2 IV | 21 |

Irinotecan | 125 mg/m2 IV on days 1, 8, 15, and 22 | 6 wk |

FOLFIRI | Irinotecan 180 mg/m2 IV on day 1 followed by | 14 |

LV 400 mg/m2/d IV on day 1 followed by | ||

5-FU 400 mg/m2/d IV on day 1 followed by | ||

5-FU 2,400 mg/m2 CIVI for 46 h | ||

Bevacizumabb | 5 mg/kg IV on day 1 | 14 |

Ziv-aflibercept | 4 mg/kg IV on day 1 | 14 |

Ramucirumab | 8 mg/kg IV on day 1 | 14 |

Cetuximabc | 400 mg/m2 IV on day 1 followed by | weekly |

250 mg/m2 IV weekly thereafter | ||

Panitumumabc | 6 mg/kg IV on day 1 | 14 |

Regorafenib | 160 mg PO once daily for 21 d | 28 |

Trifluridine and tipiracil | 35 mg/m2/dose PO twice daily on days 1–5 and 8–12 | 28 |

Pembrolizumabd | 200 mg IV on day 1 | 21 |

Nivolumabd | 240 mg IV on day 1 | 14 |

aThese are in addition to those presented in Table 9.3.

bIn combination with any 5-FU–containing regimen.

cOnly indicated for patients with RAS and/or RAF wild-type tumors.

dOnly indicated for patients with dMMR or MSI-H tumors.

LV, leucovorin; IV, intravenous; 5-FU, 5-fluorouracil; CIVI, continuous intravenous infusion.

FIGURE 9.1 Palliative treatment considerations for metastatic colorectal cancer as defined by molecular subtypes. Note: Consideration of clinical trial enrollment for each patient in these categories for each line of therapy is prudent.

Optimal Therapy Selection and Sequencing

CALGB 80405 was an important international phase III trial, which tested the optimal first line treatment in 1,137 patients with metastatic K-ras wild-type (WT) CRC. Patients were treated with FOLFOX (or FOLFIRI at provider discretion) and randomized to the addition of either cmab or bev. Median OS (the primary endpoint) was essentially the same (32 vs. 31.2 months; P = 0.40) between treatment with chemo and cmab versus bev, respectively. PFS was also similar between the arms. Retrospective analysis identified that left-sided tumors were associated with a longer median compared to those from the right colon (OS 33.3 vs. 19.4 months; P < 0.0001). Results suggested that bev may also benefit right sided tumors more than cmab-based chemotherapy (OS 24.2 vs. 16.7 months; P < 0.0001). The opposite was true for left-sided cancers suggesting cmab was more effective than bev-based chemotherapy (OS 36 vs. 31.4 months; P < 0.0001). This suggests distinct molecular variability of colon cancers depending on their “sidedness.”

The FIRE-3 study was the European equivalent of the CALGB 80405 study. It enrolled 592 similar patients and randomized them to FOLFIRI plus either bev or cmab. In contrast to the prior study, the median OS favored treatment with cmab (33.1 vs. 25.6 months; P = 0.011). Importantly, there was no difference in PFS between the groups suggesting subsequent therapy may have accounted for the improvement in OS. It should be noted that neither trial prospectively tested for N-ras or B-raf mutations, as either predictive or prognostic biomarkers.

OLIGOMETASTATIC DISEASE

The liver is the most common site for metastasis, with one-third of cases involving only the liver. Approximately 25% of liver metastases are resectable, with certain patient subsets showing 30% to 40% 5-year survival after resection and 3% to 5% operative morbidity and mortality. Nonoperative ablative techniques (i.e., cryoablation, radiofrequency ablation, stereotactic RT, and hepatic artery embolization with or without chemotherapy) have not shown consistent durable prospective survival benefits. Intraoperative ultrasound is the most sensitive test for initial detection, followed by CT scan or MRI. PET scanning can help identify occult extrahepatic disease in select patients being considered for resection.

Patients with unresectable disease limited to the liver can be treated with locoregional hepatic artery infusion (HAI) or systemic chemotherapy. Kemeny et al. reported a 4-year DFS and hepatic disease-free benefit in patients with resected liver metastases who had received intra-arterial floxuridine with systemic 5-FU compared to those who did not receive any postoperative therapy, although there was no statistically significant difference in OS (62% vs. 53%; P = 0.06). Such an approach has typically been reserved for select centers and its utility has been challenged by the advent of more effective systemic chemotherapy.

The feasibility of converting initially unresectable disease to a potentially curative disease has been investigated by Bismuth and colleagues. Resection was possible in 99 patients with either downstaged or stable disease, and the 3-year survival was encouraging (58% for responders, 45% for patients with stable disease). Similar observations have been reported by Alberts using preoperative FOLFOX4 on 41% of patients undergoing resection with an observed median survival of 31.4 months (95% CI 20.4 to 34.8) for the entire cohort. Given objective response rates of 60% to 70% in RAS WT tumors treated initially with cmab-based chemotherapy, this could provide rationale for personalizing treatment selection to optimize response and improve chances of conversion of borderline or unresectable disease. Alternatively, for those with RAS mutations where anti-EGFR therapies are contraindicated, FOLFOXIRI (5-FU/LV, irinotecan, oxaliplatin) with bev demonstrated a 65% objective response rate, however the rate of hepatic R0 surgical resections was not improved over FOLFIRI with bev.

Indeed, current management of resectable liver disease typically includes appropriate patient selection, adequate imaging to confirm isolated and limited disease burden, multidisciplinary clinical collaboration, and consideration of perioperative systemic chemotherapy. The latter recommendation is based, in part, on the results of a European study showing a progression-free survival advantage to the use of 3 months of FOLFOX4 chemotherapy pre- and post-resection compared to surgery alone. However, attention must be paid to the potential hepatotoxicity and surgical complications from prolonged perioperative chemotherapy. The maximum radiographic response from chemotherapy is typically seen at 12 weeks. Importantly, systemic chemotherapy fails to sterilize hepatic metastases, even if radiographic complete response is noted. Patients with B-raf mutations appear to have limited benefit from oligometastatic management given the aggressive and refractory nature of metastatic disease.

Suggested Readings

1.Alberts SR, Donohue JH, Mahoney MR. Liver resection after 5-fluorouracil, leucovorin and oxaliplatin for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (MCRC) limited to the liver: a North Central Cancer Treatment Group (NCCTG) Phase II Study. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2003; 22:268(abstr 1053).

2.Alberts SR, Sargent DJ, Nair S, et al. Effect of oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin with or without cetuximab on survival among patients with resected stage III colon cancer: a randomized trial. JAMA. Apr 2012;307(13):1383–1393.

3.Allegra CJ, Yothers G, O’Connell MJ, et al. Phase III trial assessing bevacizumab in stages II and III carcinoma of the colon: results of NSABP protocol C-08. J Clin Oncol. Jan 2011;29(1):11–16.

4.Allegra CJ, Yothers G, O’Connell MJ. Final results from NSABP protocol R-04: neoadjuvant chemoradiation comparing continuous infusion 5-FU with capecitabine with or without oxaliplatin in patients with stage II and III rectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014; 32(5): 3603(abstr).

5.American Cancer Society. Cancer facts and figures 2016. http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@research/documents/document/acspc-047079.pdf. Accessed September 1, 2016.

6.Amin M, Edge S, Greene F, et al. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. Chicago, IL: Springer; 2017.

7.André T, Blons H, Mabro M, et al. Panitumumab combined with irinotecan for patients with KRAS wild-type metastatic colorectal cancer refractory to standard chemotherapy: a GERCOR efficacy, tolerance, and translational molecular study. Ann Oncol. Feb 2013;24(2):412–419.

8.André T, Boni C, Mounedji-Boudiaf L, et al. Oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin as adjuvant treatment for colon cancer. N Engl J Med. Jun 2004;350(23):2343–2351.

9.André T, Boni C, Navarro M, et al. Improved overall survival with oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin as adjuvant treatment in stage II or III colon cancer in the MOSAIC trial. J Clin Oncol. Jul 2009;27(19):3109–3116.

10.Bennouna J, Sastre J, Arnold D, et al. Continuation of bevacizumab after first progression in metastatic colorectal cancer (ML18147): a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. Jan 2013;14(1):29–37.

11.Benson AB, Schrag D, Somerfield MR, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology recommendations on adjuvant chemotherapy for stage II colon cancer. J Clin Oncol. Aug 2004;22(16):3408–3419.

12.Bismuth H, Adam R, Lévi F, et al. Resection of nonresectable liver metastases from colorectal cancer after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Ann Surg. Oct 1996;224(4):509–520.

13.Cremolini C, Loupakis F, Antoniotti C, et al. FOLFOXIRI plus bevacizumab versus FOLFIRI plus bevacizumab as first-line treatment of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: updated overall survival and molecular subgroup analyses of the open-label, phase 3 TRIBE study. Lancet Oncol. Oct 2015;16(13):1306–1315.

14.Cunningham D, Humblet Y, Siena S, et al. Cetuximab monotherapy and cetuximab plus irinotecan in irinotecan-refractory metastatic colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. Jul 2004;351(4):337–345.

15.de Gramont A, Van Cutsem E, Schmoll HJ, et al. Bevacizumab plus oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy as adjuvant treatment for colon cancer (AVANT): a phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. Dec 2012;13(12):1225–1233.

16.Efficacy of adjuvant fluorouracil and folinic acid in B2 colon cancer. International Multicentre Pooled Analysis of B2 Colon Cancer Trials (IMPACT B2) Investigators. J Clin Oncol. May 1999;17(5):1356–1363.

17.Fearon ER, Vogelstein B. A genetic model for colorectal tumorigenesis. Cell. Jun 1990;61(5):759–767.

18.George TJ, Laplant KD, Walden EO, et al. Managing cetuximab hypersensitivity-infusion reactions: incidence, risk factors, prevention, and retreatment. J Support Oncol. 2010 Mar–Apr 2010;8(2):72–77.

19.Goldberg RM. N9741: a phase III study comparing irinotecan to oxaliplatin-containing regimens in advanced colorectal cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer. Aug 2002;2(2):81.

20.Gray R, Barnwell J, McConkey C, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy versus observation in patients with colorectal cancer: a randomised study. Lancet. Dec 2007;370(9604):2020–2029.

21.Grothey A, Sugrue MM, Purdie DM, et al. Bevacizumab beyond first progression is associated with prolonged overall survival in metastatic colorectal cancer: results from a large observational cohort study (BRiTE). J Clin Oncol. Nov 2008;26(33):5326–5334.

22.Grothey A, Van Cutsem E, Sobrero A, et al. Regorafenib monotherapy for previously treated metastatic colorectal cancer (CORRECT): an international, multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. Jan 2013;381(9863):303–312.

23.Habr-Gama A, Perez RO, Nadalin W, et al. Operative versus nonoperative treatment for stage 0 distal rectal cancer following chemoradiation therapy: long-term results. Ann Surg. Oct 2004;240(4):711–717.

24.Haller DG, Catalano PJ, Macdonald JS. Fluorouracil (FU), leucovorin (LV) and levamisole (LEV) adjuvant therapy for colon cancer: five-year final report of INT-0089. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 1998;15:211.