Megan Kruse, Leticia Varella, Stephanie Valente, Paulette Lebda, Andrew Vassil, and Jame Abraham

INTRODUCTION

Breast cancer is the most common cancer among women worldwide and it accounts for 25% of all cancer diagnosed among women. It is second only to lung cancer as the leading cause of death from cancer in women in North America. When diagnosed early, breast cancer can be treated primarily using surgery, radiation, and systemic therapy. In Western countries at the time of diagnosis more than 90% of patients will have only localized disease. But many other parts of the world, about 60% of patients will have locally advanced or metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

In the United States, as per American Cancer Society, in 2017, an estimated 252,170 women and 2,470 men will be diagnosed with breast cancer.

In the United States, as per American Cancer Society, in 2017, an estimated 252,170 women and 2,470 men will be diagnosed with breast cancer.

In addition, about 63,410 new cases of noninvasive (in situ) breast cancer will be diagnosed in 2017.

In addition, about 63,410 new cases of noninvasive (in situ) breast cancer will be diagnosed in 2017.

In 2017, 40,610 women and 460 men are expected to die from breast cancer in the United States.

In 2017, 40,610 women and 460 men are expected to die from breast cancer in the United States.

As per International Agency for Cancer Research (IARC) about 1.7 million women will get a diagnosis of breast cancer worldwide in 2017 and about half a million will die globally from breast cancer.

As per International Agency for Cancer Research (IARC) about 1.7 million women will get a diagnosis of breast cancer worldwide in 2017 and about half a million will die globally from breast cancer.

A U.S woman’s lifetime risk of developing breast cancer is one in eight, or about 12% will develop breast cancer.

A U.S woman’s lifetime risk of developing breast cancer is one in eight, or about 12% will develop breast cancer.

There are currently more than 3.1 million breast cancer survivors in the United States in 2017.

There are currently more than 3.1 million breast cancer survivors in the United States in 2017.

RISK FACTORS

The risk factors for developing breast cancer in women are listed in Table 12.1. The etiologies of most breast cancers are unknown and sporadic. About 5% to 10% of breast cancers are familial or hereditary.

TABLE 12.1 Risk Factors for Breast Cancer in Women

Increasing age |

Family history of breast cancer at a young age |

Genetic mutations such as BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations |

Increased mammographic breast density |

Early menarche |

Late menopause |

Nulliparity |

Older age at first child birth |

Increased body mass index (BMI) |

History of atypical lobular hyperplasia, atypical ductal hyperplasia, lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS), or flat epithelial atypia |

Prior breast biopsies |

Long-term postmenopausal estrogen and progesterone replacement |

Prior thoracic radiation therapy at age under 30 |

Genetics (For More Details Refer to Chapter 44 on Genetics)

About 5% to 10% of all women with breast cancer may have a specific mutation in a single gene that is responsible for the breast cancer, with the most common mutations occurring in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes. Other genes implicated with breast cancer are PTEN (associated with Cowden syndrome), TP53 (associated with Li-Fraumeni syndrome), CDH1 (associated with hereditary diffuse gastric cancer syndrome), STK11, PALB2, CHEK2, and ATM.

About 5% to 10% of all women with breast cancer may have a specific mutation in a single gene that is responsible for the breast cancer, with the most common mutations occurring in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes. Other genes implicated with breast cancer are PTEN (associated with Cowden syndrome), TP53 (associated with Li-Fraumeni syndrome), CDH1 (associated with hereditary diffuse gastric cancer syndrome), STK11, PALB2, CHEK2, and ATM.

Individuals with these hereditary syndromes may develop cancers early in life or multiple cancers, including bilateral breast cancer.

Individuals with these hereditary syndromes may develop cancers early in life or multiple cancers, including bilateral breast cancer.

Mutations of BRCA1 (chromosome 17q21) and BRCA2 (chromosome 13q12–13q13) are responsible for 85% of hereditary breast cancer. These genes are involved in DNA repair.

Mutations of BRCA1 (chromosome 17q21) and BRCA2 (chromosome 13q12–13q13) are responsible for 85% of hereditary breast cancer. These genes are involved in DNA repair.

Specific mutations of BRCA1 and BRCA2 are more common in women of Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry.

Specific mutations of BRCA1 and BRCA2 are more common in women of Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry.

Overall prevalence of disease-related mutation in BRCA1 has been estimated at 1 in 300, while BRCA2 is 1 in 800.

Overall prevalence of disease-related mutation in BRCA1 has been estimated at 1 in 300, while BRCA2 is 1 in 800.

The cumulative risk estimates for developing breast cancer by age 80 were 72% for BRCA1 carriers and 69% for BRCA2 carriers.

The cumulative risk estimates for developing breast cancer by age 80 were 72% for BRCA1 carriers and 69% for BRCA2 carriers.

The cumulative risk of a contralateral breast cancer 20 years after a first breast cancer was 40% for BRCA1 mutation carriers and 26% for BRCA2 mutation carriers.

The cumulative risk of a contralateral breast cancer 20 years after a first breast cancer was 40% for BRCA1 mutation carriers and 26% for BRCA2 mutation carriers.

BRCA-related breast cancer is more likely to be triple negative particularly in the setting of BRCA1 mutations.

BRCA-related breast cancer is more likely to be triple negative particularly in the setting of BRCA1 mutations.

The cumulative risk estimates for developing ovarian cancer by age 80 were 44% for BRCA1 mutation carriers and 17% for BRCA2 mutation carriers.

The cumulative risk estimates for developing ovarian cancer by age 80 were 44% for BRCA1 mutation carriers and 17% for BRCA2 mutation carriers.

Indications for Genetic Testing

All patients should have a basic assessment for risk of a hereditary breast/ovarian cancer syndrome including documentation of personal and family history (both paternal and maternal sides) of malignancy. All patients with high risk for a hereditary syndrome based on personal/family history and age at diagnosis should undergo genetic counseling before undergoing the genetic test. The genetic counseling visit is an important step in addressing the patient’s goals of testing and is an opportunity to address misconceptions/limitations of genetic testing. There are three possible outcomes of genetic testing for the BRCA mutations: positive, variant of uncertain significance, or negative. A negative result indicates no increased risk of breast cancer due to a germline mutation. A variant of uncertain significance (indeterminate) test result indicates that no conclusive evidence exists to indicate that the mutation does or does not carry an increased risk of the development of breast cancer due to an inherited genetic mutation. A positive result indicates that there exists a mutation in the patient’s genes that has been associated with an inherited risk of developing breast cancer. In general, patients with a history suggestive of a single inherited cancer syndrome should have testing sent for that specific syndrome.

Multigene testing may be cost-effective and efficient if multiple different inherited cancer syndromes could be considered based on history or if single gene testing is negative in a patient with a compelling personal or family history suggestive of an inherited cancer syndrome. One concern with the multigene testing approach is the increased likelihood of detecting a variant of uncertain significance. This also increases the importance of appropriate genetic counseling in conjunction with genetic testing such that results are interpreted in the appropriate manner.

As per NCCN guidelines (accessed in July 2017), patients with breast cancer and one or more of the following features should undergo further genetic risk evaluation:

Early-age onset breast cancer (age ≤45)

Early-age onset breast cancer (age ≤45)

Triple negative breast cancer (ER–, PR–, HER-2/neu-) diagnosed age ≤60

Triple negative breast cancer (ER–, PR–, HER-2/neu-) diagnosed age ≤60

≥2 breast primaries (with first diagnosed at age ≤50)

≥2 breast primaries (with first diagnosed at age ≤50)

Diagnosed at age ≤50 with ≥1 close blood relative (first-, second-, or third-degree relative) with breast cancer at any age, pancreatic cancer, or prostate cancer (Gleason score ≥7)

Diagnosed at age ≤50 with ≥1 close blood relative (first-, second-, or third-degree relative) with breast cancer at any age, pancreatic cancer, or prostate cancer (Gleason score ≥7)

Diagnosed at any age with ≥1 close blood relative with breast cancer diagnosed at age ≤50

Diagnosed at any age with ≥1 close blood relative with breast cancer diagnosed at age ≤50

Diagnosed at any age with ≥2 close blood relatives with breast cancer, pancreatic cancer, or prostate cancer (Gleason score ≥7) at any age

Diagnosed at any age with ≥2 close blood relatives with breast cancer, pancreatic cancer, or prostate cancer (Gleason score ≥7) at any age

Personal history of ovarian cancer or ≥1 close blood relative with ovarian cancer, fallopian tube cancer, or primary peritoneal cancers diagnosed at any age

Personal history of ovarian cancer or ≥1 close blood relative with ovarian cancer, fallopian tube cancer, or primary peritoneal cancers diagnosed at any age

Ashkenazi Jewish descent

Ashkenazi Jewish descent

Personal history of male breast cancer or male breast cancer in close blood relative at any age

Personal history of male breast cancer or male breast cancer in close blood relative at any age

Management of Patients with Positive BRCA Test

Management recommendations for patients with a known genetic mutation are highly individualized and should be made by an expert. General recommendations include the following:

Clinical breast examination every 6 to 12 months, starting at age 25

Clinical breast examination every 6 to 12 months, starting at age 25

Breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with contrast starting at age 25 or earlier based on family history or mammogram if breast MRI is not available

Breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with contrast starting at age 25 or earlier based on family history or mammogram if breast MRI is not available

Annual mammogram and annual breast MRI with contrast from age 30 to 75

Annual mammogram and annual breast MRI with contrast from age 30 to 75

Discuss option of bilateral prophylactic mastectomy on a case-by-case basis, since it could prevent breast cancer in >90% of patients with known BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation

Discuss option of bilateral prophylactic mastectomy on a case-by-case basis, since it could prevent breast cancer in >90% of patients with known BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation

Recommend bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO) ideally between the ages of 35 and 40 or after completion of child bearing. BSO alone will reduce breast cancer risk by about 50%, but it may vary depending upon the specific genes and prevents ovarian cancer by about 95%.

Recommend bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO) ideally between the ages of 35 and 40 or after completion of child bearing. BSO alone will reduce breast cancer risk by about 50%, but it may vary depending upon the specific genes and prevents ovarian cancer by about 95%.

Patients who defer BSO may consider concurrent trans-vaginal ultrasound and blood test such as CA-125, although it is not sufficiently sensitive or specific. This can be done at the discretion of the clinician, starting from the age of 30 and 35 years or 5 to 10 years prior to the earliest age of ovarian cancer in family history.

Patients who defer BSO may consider concurrent trans-vaginal ultrasound and blood test such as CA-125, although it is not sufficiently sensitive or specific. This can be done at the discretion of the clinician, starting from the age of 30 and 35 years or 5 to 10 years prior to the earliest age of ovarian cancer in family history.

CHEMOPREVENTION

Risk Assessment

There are many risk models available to assess a women’s risk for sporadic breast cancer, which accounts for 90% of the breast cancer. One of the most commonly used models is the Gail Risk model (https://www.cancer.gov/bcrisktool). It is a statistical model that calculates a woman’s absolute risk of developing breast cancer by using the following criteria:

1.Age

2.Age at menarche

3.Age at first live birth

4.Number of previous biopsies

5.History of atypical ductal hyperplasia (ADH)

6.Number of first-degree relatives with breast cancer

This model is not intended to be used in patients with an existing history of invasive cancer, DCIS, or lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS). It underestimates the risk of breast cancer in a person with hereditary breast cancer. It is used in calculating the risk in many breast cancer prevention studies including NSABP-P1 and NSABP-P2.

Prevention Studies

The National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project Breast Cancer Prevention Trial (P-1)

The National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) P-1 study showed a 49% reduction in the incidence of invasive breast cancer in high-risk subjects (based upon the Gail Risk Model) who took tamoxifen at a dose of 20 mg daily for 5 years. Women eligible for this trial were at least 35 years old and were assessed to have an absolute risk of at least 1.66% over the period of 5 years using the Gail model or a pathologic diagnosis of LCIS. Twenty-five percent of woman assigned to tamoxifen in this study discontinued the medication compared to 20% in the placebo group. Notable adverse events associated with tamoxifen therapy in this study include increased risk of endometrial cancer (particularly in women age 50 or older), cataracts, and venous thromboembolism (both deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism). An update of results with 7 years of follow-up was published in 2005 showing a continued statistically significant improvement in rate of invasive breast cancer (risk ratio 0.57) and noninvasive breast cancer (risk ratio 0.63) with tamoxifen compared to placebo.

Use of tamoxifen for breast cancer risk reduction should be considered after weighing the risk benefit ratio for each patient. Women with a life expectancy of ≥10 years and no diagnosis/history of breast cancer who are considered at increased risk of breast cancer should receive individualized counseling to decrease breast cancer risk.

NSABP P-2: Study of Tamoxifen and Raloxifene

In the NSABP P-2 study, tamoxifen 20 mg daily was compared with raloxifene 60 mg daily in postmenopausal women with high risk of developing breast cancer (Gail risk model estimate of 5-year breast cancer risk of at least 1.66%). The results of the study revealed that raloxifene was equivalent to tamoxifen in preventing invasive breast cancer (about a 50% reduction). Raloxifene did not reduce the risk of DCIS or LCIS unlike tamoxifen.

Raloxifene has a better side effect profile, which resulted in a lower incidence of uterine hyperplasia, hysterectomy, cataracts, and a lower rate of thromboembolic events. In postmenopausal patients, due to equal efficacy and better side effect profile, raloxifene 60 mg daily could be used instead of tamoxifen for breast cancer prevention. A 2010 update of the NSABP P-2 study after a median follow-up of nearly 7 years confirmed no statistical difference between invasive breast cancer events in the tamoxifen- and raloxifene-treated patients. In addition, significant reductions in risk of endometrial cancer/hyperplasia as well as thromboembolic events were reported with raloxifene compared to tamoxifen.

Aromatase Inhibitors for Risk Reduction

Aromatase inhibitors were shown to decrease the incidence of contralateral breast cancer when used in the adjuvant setting (ATAC, BIG 1-98). These data led to the investigation of AI as chemoprevention for women at high-risk for developing breast cancer.

The MAP.3 trial evaluated the role of exemestane in a risk reduction setting, randomizing women at increased risk for breast cancer (based on age 60 or older, Gail 5-year risk score of at least 1.66%, prior atypical ductal/lobular hyperplasia or LCIS or DCIS status postmastectomy) to either exemestane or placebo. At a median follow-up of 3 years, it was found that exemestane reduced the relative incidence of breast cancers by 65% when compared to placebo. Exemestane was not associated with any significant serious side effects, although hot flashes and arthritis were very common in both the exemestane and placebo groups. Quality of life was minimally impacted by exemestane use with respect to menopausal symptoms.

In the randomized phase III IBIS II trial, postmenopausal women at increased risk of breast cancer (defined as significant family history, history of atypical hyperplasia, or LCIS, nulliparity or age at first birth of ≥ 30) were randomized to receive anastrozole or placebo for 5 years. Results showed a reduction in the risk of developing breast cancer (both invasive and noninvasive) of more than 50% (HR of 0.47) with use of anastrozole compared to placebo. Musculoskeletal events and vasomotor symptoms were significantly more common in patients receiving anastrozole rather than placebo.

In premenopausal women with increased risk of breast cancer as per the Gail risk model, it is reasonable to recommend tamoxifen 20 mg daily for 5 years. In postmenopausal women raloxifene and tamoxifen are equally effective, but raloxifene has been shown to have less side effects. Aromatase inhibitors can also be considered given the data from the MAP.3 and IBIS II trials; however, the FDA has not approved aromatase inhibitors in this setting. Any risk reduction approach should be carefully decided after a detailed risk versus benefit discussion with the patient.

BREAST CANCER SCREENING

Screening Mammograms

Screening mammography has been shown to decrease breast cancer mortality in women between the ages of 40 and 70 years with an absolute mortality benefit of 1% for women screened annually for 10 years.

Screening mammography has been shown to decrease breast cancer mortality in women between the ages of 40 and 70 years with an absolute mortality benefit of 1% for women screened annually for 10 years.

Potential harms associated with screening mammography include overdiagnosis and treatment of cancers that would otherwise have been clinically insignificant in a woman’s lifetime as well as the unnecessary anxiety and additional testing that is associated with false positive screening examination.

Potential harms associated with screening mammography include overdiagnosis and treatment of cancers that would otherwise have been clinically insignificant in a woman’s lifetime as well as the unnecessary anxiety and additional testing that is associated with false positive screening examination.

The American Cancer Society recommends that women ages 40 to 44 should have the choice to start annual mammography screening and women ages 45 to 54 should receive annual mammograms. At age 55, the American Cancer Society suggests that women may switch to having mammograms every other year for breast cancer screening although annual screening may be continued if the patient desires.

The American Cancer Society recommends that women ages 40 to 44 should have the choice to start annual mammography screening and women ages 45 to 54 should receive annual mammograms. At age 55, the American Cancer Society suggests that women may switch to having mammograms every other year for breast cancer screening although annual screening may be continued if the patient desires.

Women who are at higher than average risk of breast cancer (women with a family history of breast cancer, women with either the BRCA1 or the BRCA2 gene, women with a history of chest irradiation between the ages of 10 and 30, or women with a lifetime risk of breast cancer ≥20%) are recommended to initiate screening mammograms at age 25 to 30 or 10 years earlier than the age of the affected first-degree relative at diagnosis (whichever is later) or 8 years after radiation therapy, as per the American College of Radiology guidelines.

Women who are at higher than average risk of breast cancer (women with a family history of breast cancer, women with either the BRCA1 or the BRCA2 gene, women with a history of chest irradiation between the ages of 10 and 30, or women with a lifetime risk of breast cancer ≥20%) are recommended to initiate screening mammograms at age 25 to 30 or 10 years earlier than the age of the affected first-degree relative at diagnosis (whichever is later) or 8 years after radiation therapy, as per the American College of Radiology guidelines.

Mammograms should be continued regardless of a woman’s age, as long as she is in good health with an expected life expectancy of at least 10 years. Age alone should not be the reason to stop having regular mammograms. Women with serious health problems or short life expectancies should discuss with their doctors whether to continue having mammograms.

Mammograms should be continued regardless of a woman’s age, as long as she is in good health with an expected life expectancy of at least 10 years. Age alone should not be the reason to stop having regular mammograms. Women with serious health problems or short life expectancies should discuss with their doctors whether to continue having mammograms.

The diagnostic superiority of digital mammography was demonstrated in the Digital Mammographic Imaging Screening Trial (DMIST) published in 2005. This study concluded that the overall accuracy of digital and film mammography was similar however in pre- or peri-menopausal women under the age of 50 or women at any age with dense breasts, digital mammography more accurately detected of breast cancer.

Digital breast tomosynthesis (DBT), commonly referred to as 3-D mammography, is an x-ray technique that uses a finite number of low-dose projections to reconstruct a series of thin-section images of the breast. The STORM (screening with tomosynthesis or standard mammography) trial was a large prospective Italian study that compared conventional screening digital mammography to combined digital mammography and DBT for breast cancer screening in an average risk population. The study demonstrated that detection of breast cancer significantly increased with the addition of DBT to conventional digital mammography. A 2014 study from Friedewald et al. also demonstrated that this technology can decrease the rate of recall for benign findings. As per discussion by Houssami and Skanne, it is important to note that integrated use of 2D mammography and DBT nearly doubles the overall radiation exposure, so careful consideration must be given of how to incorporate DBT to usual 2D screening. However, some DBT vendors have introduced synthetic 2D views which when used in place of conventional 2D images reduces the radiation dose of DBT combination examination.

While breast MRI has been shown to have a higher sensitivity than mammography, the specificity of breast MRI is lower, which can result in more false positives and therefore more biopsies. Patients need to be carefully selected for additional screening with breast MRI. In a high-risk population, the sensitivity of mammography when combined with MRI (92.7%) is higher than the sensitivity of mammography when combined with ultrasound (52%). Therefore, in women in whom supplemental screening is indicated, MRI is recommended when possible. According to the American Cancer Society recommendations, breast MRI can be used as an adjunct to screening mammography in high-risk women, specifically those with BRCA gene mutations (along with their untested first-degree relatives), those who received chest radiation between the ages of 10 and 30, and those whose lifetime risk of breast cancer exceeds 20%.

CLINICAL FEATURES OF BREAST CANCER

Clinical features may include a breast lump, skin thickening or alteration, peau d’orange, dimpling of the skin, nipple inversion or crusting (Paget disease), unilateral nipple discharge, and new onset pain. Patients may instead present with signs and symptoms of metastatic disease.

DIAGNOSIS

1.History and physical examination

2.Bilateral mammogram (80% to 90% accuracy)

3.Biopsy: Any distinct mass should be considered for a biopsy, even if the mammograms are negative

The standard method of diagnosis for palpable lesions is

Core-needle biopsy

Core-needle biopsy

The options in nonpalpable breast lesions are

Ultrasound-guided core-needle biopsy

Ultrasound-guided core-needle biopsy

Stereotactic core-needle biopsy under mammographic localization

Stereotactic core-needle biopsy under mammographic localization

Needle localization under mammography, followed by surgical excision

Needle localization under mammography, followed by surgical excision

MRI-guided biopsy

MRI-guided biopsy

4.Laboratory studies

Complete blood count, liver function tests, and alkaline phosphatase level can be considered depending upon the history and physical.

Complete blood count, liver function tests, and alkaline phosphatase level can be considered depending upon the history and physical.

Routine use of breast cancer markers such as CA 27:29 and CA 15:3 is not recommended.

Routine use of breast cancer markers such as CA 27:29 and CA 15:3 is not recommended.

5.Pathology and special studies

Histology and diagnosis (invasive vs. in situ)

Histology and diagnosis (invasive vs. in situ)

Pathologic grade of the tumor

Pathologic grade of the tumor

Tumor involvement of the margin

Tumor involvement of the margin

Tumor size

Tumor size

Lymphovascular invasion

Lymphovascular invasion

6.Estrogen receptor/progesterone receptor (ER/PR) status should be done in all tumors (both invasive and noninvasive) and biopsies of metastatic or recurrent (patients those who relapsed) lesions.

As per the ASCO/CAP guidelines (2010), ER/PR is considered as positive if ≥1% of tumor cell nuclei are immunoreactive.

As per the ASCO/CAP guidelines (2010), ER/PR is considered as positive if ≥1% of tumor cell nuclei are immunoreactive.

7.HER-2/neu- testing (as per ASCO/CAP Guidelines 2013)

Positive for HER-2/neu- is either IHC 3 + (defined as uniform intense membrane staining of more than 30% of invasive tumor cells) or FISH amplified (ratio of HER-2/neu- to CEP17 of ≥2.0 or average HER-2/neu- gene copy number ≥6 signals/nucleus for those test systems without an internal control probe).

Positive for HER-2/neu- is either IHC 3 + (defined as uniform intense membrane staining of more than 30% of invasive tumor cells) or FISH amplified (ratio of HER-2/neu- to CEP17 of ≥2.0 or average HER-2/neu- gene copy number ≥6 signals/nucleus for those test systems without an internal control probe).

Equivocal for HER-2/neu- is defined as either IHC 2 + or FISH ratio of <2 and average HER-2/neu- gene copy number of ≥ 4.0 and < 6.0 signals/nucleus for test systems without an internal control probe.

Equivocal for HER-2/neu- is defined as either IHC 2 + or FISH ratio of <2 and average HER-2/neu- gene copy number of ≥ 4.0 and < 6.0 signals/nucleus for test systems without an internal control probe.

Negative for HER-2/neu- is defined as either IHC 0–1 + or FISH ratio < 2 with an average HER-2/neu- gene copy number < 4 signals/nucleus for test systems without an internal control probe.

Negative for HER-2/neu- is defined as either IHC 0–1 + or FISH ratio < 2 with an average HER-2/neu- gene copy number < 4 signals/nucleus for test systems without an internal control probe.

8.Indices of proliferation (e.g., mitotic index, Ki-67, or S phase) can be helpful. Ki-67 can be helpful in distinguishing luminal A versus B in ER/PR-positive lesions. Lack of standardization of Ki-67 testing limits its wide utilization in clinical practice.

9.Radiographic studies are performed on the basis of the findings of the history and physical examination, diagnostic breast imaging and blood tests. Appropriate imaging studies such as CT scan, ultrasound, MRI, or CT/PET scan can be considered as per the clinical indications. They are not routinely recommended for all patients.

As per the American Society of Clinical Oncology “Choosing Wisely” guidelines, it is not recommended that patients with DCIS or clinical stage I/ II disease receive staging PET, CT, or radionucleotide bone scan as there is no clear evidence indicating benefit, and unnecessary imaging can lead to unnecessary invasive procedures/radiation exposure, overtreatment or misdiagnosis.

As per the American Society of Clinical Oncology “Choosing Wisely” guidelines, it is not recommended that patients with DCIS or clinical stage I/ II disease receive staging PET, CT, or radionucleotide bone scan as there is no clear evidence indicating benefit, and unnecessary imaging can lead to unnecessary invasive procedures/radiation exposure, overtreatment or misdiagnosis.

The NCCN guidelines recommend that systemic imaging be considered in patients with locally advanced (Stage III) patients and in those with signs or symptoms suggestive of metastatic disease.

The NCCN guidelines recommend that systemic imaging be considered in patients with locally advanced (Stage III) patients and in those with signs or symptoms suggestive of metastatic disease.

10.Breast MRI may be helpful in determining the extent of disease and to facilitate surgical planning in the following patients (as per NCCN guidelines):

Those with heterogenous and extremely dense mammographic tissue

Those with heterogenous and extremely dense mammographic tissue

Those with newly diagnosed invasive lobular carcinoma

Those with newly diagnosed invasive lobular carcinoma

Those with axillary nodal metastasis with unknown primary

Those with axillary nodal metastasis with unknown primary

Those who are candidates for neoadjuvant chemotherapy and as part of monitoring response to neoadjuvant therapy

Those who are candidates for neoadjuvant chemotherapy and as part of monitoring response to neoadjuvant therapy

Evaluating the extent of disease in known cancer patients

Evaluating the extent of disease in known cancer patients

•Multifocal and multicentric disease

•Pectoralis and chest wall involvement

Postlumpectomy patients to evaluate residual disease (close or positive margins)

Postlumpectomy patients to evaluate residual disease (close or positive margins)

Suspected recurrence of breast cancer

Suspected recurrence of breast cancer

•Inconclusive mammographic/clinical findings

•Reconstruction with tissue flaps or implants

Lesion characterization

Lesion characterization

Inconclusive findings on mammogram, ultrasound, and physical examination

Inconclusive findings on mammogram, ultrasound, and physical examination

PATHOLOGY

Infiltrating or invasive ductal cancer is the most common breast cancer histologic type and comprises 70% to 80% of all cases (Table 12.2).

TABLE 12.2 Pathologic Classification of Breast Cancer

Ductal |

Intraductal (in situ) |

Invasive with predominant intraductal component |

Invasive, NOS |

Comedo |

Inflammatory |

Medullary with lymphocytic infiltrate |

Mucinous (colloid) |

Papillary |

Scirrhous |

Tubular |

Other |

Other |

Undifferentiated |

Lobular |

In situ |

Invasive with predominant in situ component |

Invasive |

Nipple |

Paget disease, NOS |

Paget disease with intraductal carcinoma |

Paget disease with invasive ductal carcinoma |

Other types (not typical breast cancer) |

Phyllodes tumor |

Angiosarcoma |

Primary lymphoma |

NOS, not otherwise specified.

STAGING OF BREAST CANCER

For staging of breast cancer the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) manual, eighth edition, should be followed. This edition of the AJCC manual includes separate anatomic and prognostic staging group systems for breast cancer, reflecting the importance of biomarkers in breast cancer prognosis and treatment decisions. These biomarkers provide a sense of tumor biology. The traditional anatomic stage groups (including only the “TNM” or tumor size, nodal status, and metastasis categories) should now only be used in regions of the world where biomarker tests are not routinely available. The new eighth edition AJCC prognostic staging is the standard for cancer registries in the United States moving forward. This prognostic group staging system includes the TNM categories in addition to

1.Histologic grade

2.HER2 status

3.ER status

4.PR status

5.Oncotype Dx recurrence score (for certain TNM groups only)

Key stage changes that have occurred as a result of the eighth edition of the AJCC staging are summarized in Table 12.3.

Table 12.3Key Stage Changes in AJCC Eighth Edition Breast Cancer Staging

Anatomic TNM Staging | Relevant Biomarkers in AJCC Eighth Edition | AJCC Seventh Edition Stage Group | AJCC Eighth Edition Prognostic Stage Group |

T2N0M0 | Grades 1–3 HER2 negative ER positive PR any Oncotype Dx Recurrence score <11 | IIA | IA |

T2N1M0 | Grade 1 HER2 negative ER positive PR positive | IIB | IB |

T2N1M0 | Grade 2 HER2 positive ER positive PR positive | IIB | IB |

T0-2N2M0 | Grades 1–2 HER-2 positive ER positive PR positive | IIIA | IB |

T3N1-2M0 | Grades 1–2 HER2 positive ER positive PR positive | IIIA | IB |

T1N0M0 | Grades 1–3 HER2 negative ER negative PR negative | IA | IIA |

T1N0M0 | Grade 3 HER2 negative ER positive PR negative | IA | IIA |

T1N0M0 | Grade 3 HER2 negative ER negative PR positive | IA | IIA |

T0-2N2 | Grade 1 HER2 negative ER positive PR positive | IIIA | IIA |

T0-1N1M0 | Grade 2 HER2 negative ER negative PR negative | IIA | IIIA |

T2N0M0 | Grade 2 HER2 negative ER negative PR negative | IIA | IIIA |

Grade 3 HER2 negative ER positive PR negative | IIA | IIIA | |

T2N0M0 | Grade 3 HER2 negative ER negative PR any | IIA | IIIA |

T1-4N3M0 | Grade 1 HER2 negative ER positive PR positive | IIIC | IIIA |

T2N1M0 | Grades 1–2 HER2 negative ER negative PR negative | IIB | IIIB |

T2N1M0 | Grade 3 HER2 negative ER positive PR negative | IIB | IIIB |

T2N1M0 | Grade 3 HER2 negative ER negative PR any | IIB | IIIC |

T0-2N2M0 | Grades 2–3 HER2 negative AND ER/PR negative OR ER positive/PR negative OR ER negative/PR any | IIIA | IIIC |

T3N1-2M0 | Grades 2–3 HER2 negative AND ER/PR negative OR ER positive/PR negative OR ER negative/PR any | IIIA | IIIC |

Prognostic Factors

Anatomic features such as tumor size and lymph node status are important prognostic features. But biologic features of the tumor are equally important or possibly even more important than anatomic features.

1.Number of positive axillary lymph nodes

•This is an important prognostic indicator. Prognosis is worse with increasing number of lymph nodes.

2.Tumor size

•In general, tumors smaller than 1 cm have a good prognosis in patients without lymph node involvement.

3.Histologic or nuclear grade

•Patients with poorly differentiated histology and high nuclear grade have a worse prognosis than others.

•Scarff-Bloom-Richardson grading system and Fisher nuclear grade are commonly used systems. The modified Scarff-Bloom-Richardson grading system assigns a score (1 to 3 points) for features such as size, mitosis, and tubule formation. These scores are added and tumors are labeled low grade (3 to 5 points), intermediate grade (6 to 7 points), or high grade (8 to 9 points).

4.ER/PR status

•ER- and/or PR-positive tumors have better prognosis and these patients are eligible to receive endocrine therapy.

5.Histologic tumor type

•Prognoses of infiltrating ductal and lobular carcinoma are similar.

•Mucinous (colloid) and tubular histologies have better prognosis.

•Inflammatory breast cancer is one of the most aggressive forms of breast cancer.

6.HER-2/neu expression

•HER-2/neu overexpression is a poor prognostic marker and patients with HER-2/neu overexpression are candidates for HER-2/neu-targeted therapies. Availability of effective HER-2/neu-targeted therapies has revolutionized the treatment and outcome of HER-2/neu-positive breast cancer. Because of targeted therapies, for all practical purposes, HER-2/neu positivity can be considered as a good prognostic feature now.

7.Gene expression profiles

•Oncotype DX is a diagnostic genomic assay based on reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) on paraffin-embedded tissue (Fig. 12.1). This assay was initially developed to quantify the likelihood of cancer recurrence in women with newly diagnosed, stage I or II, node-negative, ER-positive breast cancer. Patients are divided into low-risk, intermediate-risk, and high-risk groups on the basis of the expression of a panel of 21 genes. The recurrence score determined by this assay is found to be a better predictor of outcome than standard measures such as age, tumor size, and tumor grade.

•The TAILORx study demonstrated excellent overall survival (OS), freedom from recurrence and invasive disease-free survival (DFS) at 5 years in “low risk” patients defined as those with a recurrence score of 0 to 10, all of whom received endocrine therapy only. Patients with recurrence score of 11 to 25 were randomly assigned to receive chemotherapy plus endocrine therapy or endocrine therapy alone, and outcome data on these patients is awaited. Studies have validated the role of Oncotype DX patients with ER-positive node-positive tumors and it can be used in selected settings. Oncotype DX testing has also been studied in DCIS where the resulting “DCIS score” quantifies the ipsilateral breast event risk for both invasive and noninvasive disease after surgical excision without radiation.

FIGURE 12.1 Oncotype DX assay.

•MammaPrint is a DNA microarray assay of 70 genes designed to predict the risk of recurrence of early-stage breast cancer. This testing classifies patients as low risk or high risk. There is no “intermediate” group as there is with the Oncotype. In February 2007, the FDA approved the use of MammaPrint in patients less than the age of 61, with a tumor size less than 5 cm and lymph node negative. The MINDACT study, which was published in 2016, was done to prospectively assess the clinical utility of the MammaPrint in selecting early-stage patients with up to 3 axillary lymph nodes involved for adjuvant chemotherapy. The patients in this study had both genomic and clinical risk defined and those with discordant results (meaning low genomic risk /high clinical risk or high genomic risk/low clinical risk) were randomized to either receive chemotherapy or not. The primary endpoint of the study was survival without distant metastases in patients with high-risk clinical features and low-risk genomic features. It was found that 5-year metastasis-free survival in these patients was similar whether or not chemotherapy was given (absolute difference 1.5%).

An update to the ASCO clinical guidelines regarding use of MammaPrint was released in July 2017 stating that use of the MammaPrint can be considered to assist in decisions regarding adjuvant chemotherapy in ER-positive or PR-positive, HER2-negative, N0 or N1 breast cancer patients with high clinical risk of recurrence as described in the MINDACT study. For those who have low clinical risk of recurrence, use of MammaPrint is not recommended.

Other genomic assays available for decision making in early breast cancer include the Breast Cancer Index, EndoPredict, PAM50 risk of recurrence score, Mammostrat and Urokinase plasminogen activator, and plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1. Each of these tests is intended to help clinicians identify patients with hormone receptor–positive, HER2-negative early-stage breast cancer who have a low risk of distant recurrence. This information can then be used to aide in making decisions regarding adjuvant systemic therapy.

Other genomic assays available for decision making in early breast cancer include the Breast Cancer Index, EndoPredict, PAM50 risk of recurrence score, Mammostrat and Urokinase plasminogen activator, and plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1. Each of these tests is intended to help clinicians identify patients with hormone receptor–positive, HER2-negative early-stage breast cancer who have a low risk of distant recurrence. This information can then be used to aide in making decisions regarding adjuvant systemic therapy.

As per the 2016 ASCO clinical practice guideline on “use of biomarkers to guide decisions on adjuvant systemic therapy for women with early-stage invasive breast cancer,” there is intermediate quality evidence for use of EndoPredict and Breast Cancer Index in ER/PR-positive, HER2-negative patients with node negative breast cancer to guide decisions on adjuvant systemic therapy. For the PAM50 risk of recurrence score, the evidence is considered high quality and recommendation for use in the above setting is strong.

As per the 2016 ASCO clinical practice guideline on “use of biomarkers to guide decisions on adjuvant systemic therapy for women with early-stage invasive breast cancer,” there is intermediate quality evidence for use of EndoPredict and Breast Cancer Index in ER/PR-positive, HER2-negative patients with node negative breast cancer to guide decisions on adjuvant systemic therapy. For the PAM50 risk of recurrence score, the evidence is considered high quality and recommendation for use in the above setting is strong.

Genomic Subtypes of Breast Cancer

Several distinct types of breast cancer are identified by gene expression studies. They differ markedly in prognosis and in the therapeutic targets they express (Table 12.4). The 5 main subtypes, known as the “intrinsic subtypes of breast cancer,” are described here:

TABLE 12.4 Systemic Treatment Recommendations Based upon Subtypes

Luminal A | Endocrine therapy alone |

Luminal B (HER-2/neu-negative) | Endocrine +/− Chemo |

Luminal B (HER-2/neu-positive) | Chemo + anti-HER-2/neu-drugs endocrine therapy |

HER-2/neu-positive (nonluminal) | Chemo + anti-HER-2/neu-drugs |

Triple negative | Chemotherapy |

Special Biologic Subtypes |

|

Endocrine responsive (cribriform, tubular, and mucinous) | Endocrine therapy |

Endocrine nonresponsive (medullary, adenoid, and metaplastic) | Chemotherapy |

Luminal A and B subtypes: Luminal A and luminal B subtypes express genes associated with luminal epithelial cells of normal breast tissue and overlap with ER-positive breast cancers defined by clinical assays. The luminal A subtype amounts to about 40% to 50% of cancers and has the best prognosis. These tumors are generally ER/PR-positive and HER-2 negative. Approximately 20% of breast cancers are of luminal B subtype, and they have worse prognosis compared to luminal A. The luminal B subtype tends to include tumors that are ER or PR positive and HER2-negative as well as those that are ER, PR, and HER2-positive. Luminal B cancers also tend to be higher grade tumors compared to luminal A cancers. Luminal A cancers are generally responsive to endocrine therapy while luminal B tumors may benefit from a combined approach including chemotherapy and endocrine therapy.

Luminal A and B subtypes: Luminal A and luminal B subtypes express genes associated with luminal epithelial cells of normal breast tissue and overlap with ER-positive breast cancers defined by clinical assays. The luminal A subtype amounts to about 40% to 50% of cancers and has the best prognosis. These tumors are generally ER/PR-positive and HER-2 negative. Approximately 20% of breast cancers are of luminal B subtype, and they have worse prognosis compared to luminal A. The luminal B subtype tends to include tumors that are ER or PR positive and HER2-negative as well as those that are ER, PR, and HER2-positive. Luminal B cancers also tend to be higher grade tumors compared to luminal A cancers. Luminal A cancers are generally responsive to endocrine therapy while luminal B tumors may benefit from a combined approach including chemotherapy and endocrine therapy.

HER-2-enriched subtype: The HER-2-enriched subtype comprises the majority of clinically HER-2/neu-positive breast cancers. It accounts for 10% to 15% of breast cancers. Not all HER-2/neu-positive tumors are HER-2/neu-enriched. About half of clinical HER-2/neu-positive breast cancers are HER-2/neu- enriched; the other half can include any molecular subtype including HER-2/neu-positive luminal subtypes. Those tumors that are ER/PR-negative and grade 3 tend to fall into the HER2-enriched subtype.

HER-2-enriched subtype: The HER-2-enriched subtype comprises the majority of clinically HER-2/neu-positive breast cancers. It accounts for 10% to 15% of breast cancers. Not all HER-2/neu-positive tumors are HER-2/neu-enriched. About half of clinical HER-2/neu-positive breast cancers are HER-2/neu- enriched; the other half can include any molecular subtype including HER-2/neu-positive luminal subtypes. Those tumors that are ER/PR-negative and grade 3 tend to fall into the HER2-enriched subtype.

Basal-like subtype: These tumors are usually ER-negative and characterized by low expression of hormone receptor–related genes. Up to 90% of triple negative breast cancers (those that are ER-negative, PR-negative, and HER2-negative) are classified in the basal-like subtype. They have a more aggressive clinical course with higher risk of relapse and derive benefit from chemotherapy.

Basal-like subtype: These tumors are usually ER-negative and characterized by low expression of hormone receptor–related genes. Up to 90% of triple negative breast cancers (those that are ER-negative, PR-negative, and HER2-negative) are classified in the basal-like subtype. They have a more aggressive clinical course with higher risk of relapse and derive benefit from chemotherapy.

Normal-like subtype: This subtype is represented in a minority of breast cancers and is similar in biomarker profile to luminal A tumors but with a gene profile more consistent with normal breast tissue rather than a luminal A tumor.

Normal-like subtype: This subtype is represented in a minority of breast cancers and is similar in biomarker profile to luminal A tumors but with a gene profile more consistent with normal breast tissue rather than a luminal A tumor.

MANAGEMENT

High-Risk Lesions

Patients with high-risk lesions may be eligible for breast cancer prevention studies. Tamoxifen and raloxifene are two FDA-approved drugs for breast cancer prevention in high-risk settings. As per the MAP.3 study exemestane was found to be effective in breast cancer prevention; however, the drug is not FDA approved for this indication. For breast cancer prevention, in premenopausal patients, tamoxifen is the drug of choice, but in postmenopausal patients, raloxifene or aromatase inhibitors can be used.

Atypical Ductal Hyperplasia (ADH)

There is a 4- to 5-fold increase in the risk of developing breast cancer in patients with ADH.

There is a 4- to 5-fold increase in the risk of developing breast cancer in patients with ADH.

There is wide variation in the criteria used in the diagnosis of ADH.

There is wide variation in the criteria used in the diagnosis of ADH.

If diagnosis is made with core-needle biopsy, the presence of invasive cancer may be missed due to sampling error. As a result, surgical excision of the site of ADH is recommended.

If diagnosis is made with core-needle biopsy, the presence of invasive cancer may be missed due to sampling error. As a result, surgical excision of the site of ADH is recommended.

Fifteen percent to 30% of cases may be “upgraded” to diagnosis of invasive cancer.

Fifteen percent to 30% of cases may be “upgraded” to diagnosis of invasive cancer.

Clinical breast examination and mammogram are the preferred screening methods, role of MRI is under investigation.

Clinical breast examination and mammogram are the preferred screening methods, role of MRI is under investigation.

Tamoxifen 20 mg PO for 5 years: The NSABP P-1 study showed 86% reduction in the risk of developing invasive breast cancer in patients who received tamoxifen.

Tamoxifen 20 mg PO for 5 years: The NSABP P-1 study showed 86% reduction in the risk of developing invasive breast cancer in patients who received tamoxifen.

The NSABP P-2 study showed similar efficacy for raloxifene 60 mg daily for 5 years, but with fewer adverse effects. Hence, in postmenopausal patients, raloxifene could be considered as the preferred treatment option.

The NSABP P-2 study showed similar efficacy for raloxifene 60 mg daily for 5 years, but with fewer adverse effects. Hence, in postmenopausal patients, raloxifene could be considered as the preferred treatment option.

LCIS is not considered a form of cancer, but rather a benign lesion that indicates an increased risk of developing invasive breast cancer. In the eighth edition of the AJCC staging system, Tis(LCIS) has been eliminated reflecting the nonmalignant nature of these lesions.

LCIS is not considered a form of cancer, but rather a benign lesion that indicates an increased risk of developing invasive breast cancer. In the eighth edition of the AJCC staging system, Tis(LCIS) has been eliminated reflecting the nonmalignant nature of these lesions.

There is a 24% chance of developing breast cancer in patients within 10 years of developing LCIS.

Classical LCIS is not managed with surgery; it is managed with close clinical follow-up. If the LCIS is pleomorphic or has necrosis, excision with negative margins can be considered.

Classical LCIS is not managed with surgery; it is managed with close clinical follow-up. If the LCIS is pleomorphic or has necrosis, excision with negative margins can be considered.

Patients with classical LCIS can be followed up by clinical breast examination every 4 to 12 months and annual mammogram. As per the American Cancer Society, there is insufficient data to recommend regular breast MRIs for all patients with LCIS although this can be considered on an individual basis.

Patients with classical LCIS can be followed up by clinical breast examination every 4 to 12 months and annual mammogram. As per the American Cancer Society, there is insufficient data to recommend regular breast MRIs for all patients with LCIS although this can be considered on an individual basis.

Tamoxifen or raloxifene (postmenopausal) may be used for prevention of breast cancer (56% reduction in risk as per the NSABP P-1 and P-2 studies).

Tamoxifen or raloxifene (postmenopausal) may be used for prevention of breast cancer (56% reduction in risk as per the NSABP P-1 and P-2 studies).

Noninvasive Breast Cancer

The extensive use of mammograms has led to the increasing diagnosis of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS)

The extensive use of mammograms has led to the increasing diagnosis of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS)

Microcalcification or soft tissue abnormality is seen in the mammogram of DCIS.

Microcalcification or soft tissue abnormality is seen in the mammogram of DCIS.

DCIS is considered a precursor lesion for invasive breast cancer

DCIS is considered a precursor lesion for invasive breast cancer

Comedonecrosis and high nuclear grade have been associated with shorter time to recurrence but do not predict higher overall recurrence rates

Comedonecrosis and high nuclear grade have been associated with shorter time to recurrence but do not predict higher overall recurrence rates

In patients with ER positive DCIS, lumpectomy followed by radiation treatment followed by endocrine therapy for 5 years can be considered as the standard treatment approach.

Based upon NSABP B-24, in premenopausal women with ER positive DCIS treated with lumpectomy, tamoxifen 20 mg daily for 5 years reduced the risk of breast cancer recurrence (ipsilateral and contralateral)

Based upon NSABP B-24, in premenopausal women with ER positive DCIS treated with lumpectomy, tamoxifen 20 mg daily for 5 years reduced the risk of breast cancer recurrence (ipsilateral and contralateral)

Based upon NSABP B-35, in postmenopausal women with ER positive DCIS, anastrozole 1 mg daily resulted in improvement in breast cancer–free interval for women < 60 years. Based on this data, aromatase inhibitors can be used in postmenopausal patients with ER positive DCIS after lumpectomy.

Based upon NSABP B-35, in postmenopausal women with ER positive DCIS, anastrozole 1 mg daily resulted in improvement in breast cancer–free interval for women < 60 years. Based on this data, aromatase inhibitors can be used in postmenopausal patients with ER positive DCIS after lumpectomy.

Mastectomy with or without lymph node evaluation can also be considered as a treatment option. In patients who undergo mastectomy, the role of endocrine therapy is limited. In selected patients, endocrine therapy can be considered for contralateral breast cancer prevention.

Mastectomy with or without lymph node evaluation can also be considered as a treatment option. In patients who undergo mastectomy, the role of endocrine therapy is limited. In selected patients, endocrine therapy can be considered for contralateral breast cancer prevention.

Axillary lymph node evaluation is not recommended in pure DCIS without evidence of invasive cancer. In patients with DCIS on biopsy who are treated with mastectomy, a sentinel lymph node evaluation can be considered at the time of initial surgery as a future sentinel node evaluation would not be possible if invasive disease is found on final surgical pathology.

Axillary lymph node evaluation is not recommended in pure DCIS without evidence of invasive cancer. In patients with DCIS on biopsy who are treated with mastectomy, a sentinel lymph node evaluation can be considered at the time of initial surgery as a future sentinel node evaluation would not be possible if invasive disease is found on final surgical pathology.

NSABP B-43: study of trastuzumab in HER-2/neu-positive DCIS has completed and waiting for the results.

NSABP B-43: study of trastuzumab in HER-2/neu-positive DCIS has completed and waiting for the results.

Invasive Breast Cancer

A multidisciplinary team should manage breast cancer, with the input from a radiologist, pathologist, breast surgeon, reconstructive surgeon, medical oncologist, and radiation oncologist. Other key members of the multidisciplinary team should include genetic counselors, psychologists, social workers, nurses, and navigators.

After the diagnosis of breast cancer with a core-needle biopsy or fine-needle aspiration cytology, it is important to confirm the histology, prognostic markers, and receptors. Various treatment options should then be discussed with the patient before the treatment plan is finalized.

There are two components to surgical management of breast cancer: removal of the breast cancer and evaluation of lymph nodes.

Patients with DCIS or invasive cancer have two options for removing breast cancer, mastectomy, or lumpectomy. As per NSABP B-06 and EORTC 10801, 20 year local recurrence for mastectomy is 5%, for lumpectomy alone 40%, and lumpectomy with radiation is 14%. Despite these differences in local recurrence, there is no survival difference seen in patients who are treated with mastectomy versus lumpectomy and radiation therapy (breast conservation therapy [BCT]) and therefore both are offered as treatment options. Additionally, for those electing for BCT, adjuvant breast radiation is recommended.

In some cases, despite a desire for BCT, a mastectomy may be recommended. These include a contraindication to receiving radiation, multicentric disease, inflammatory breast cancer, or a large tumor in a small breast where resection would leave a cosmetically unpleasing result.

As per NCCN guidelines, contraindications for breast-conserving therapy requiring radiation therapy include

Radiation therapy during pregnancy

Radiation therapy during pregnancy

Widespread disease or calcifications that cannot be incorporated by breast conservation that achieves negative margins with a satisfactory cosmetic result

Widespread disease or calcifications that cannot be incorporated by breast conservation that achieves negative margins with a satisfactory cosmetic result

Positive pathologic margin (no ink on tumor for invasive cancer, 2 mm margin for DCIS)

Positive pathologic margin (no ink on tumor for invasive cancer, 2 mm margin for DCIS)

Prior radiation therapy to the breast or chest wall

Prior radiation therapy to the breast or chest wall

Active connective tissue disease involving the skin (especially scleroderma and lupus)

Active connective tissue disease involving the skin (especially scleroderma and lupus)

Tumors >5 cm

Tumors >5 cm

Women with a known genetic predisposition to breast cancer such as BRCA 1 or 2 have an increased risk of contralateral breast cancer or ipsilateral breast recurrence with breast-conserving therapy. Prophylactic bilateral mastectomy for risk reduction in these patients may be considered.

The goal of sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) is to provide prognostic information regarding the accurate pathologic staging of breast cancer. This information is used to guide additional management decisions. The SLN is defined as the main lymph node(s) that receives drainage directly from the primary tumor. SLN mapping and resection is the preferred method for staging the clinically negative axilla per NCCN guidelines. SLNB is performed by injection of technetium-labeled sulfur colloid, vital blue dye, or both around the tumor, or the subareolar area is taken up into the breast lymphatic system with a predominant pattern into the axilla. Nodes that contain dye or technetium are identified as the SLN. Identification rates of 92% to 98% of patients are the standard, especially when both techniques are used. If breast cancer were to spread, typically it would spread to the sentinel lymph node (SLN) first before moving to the other lymph nodes. This selective biopsy of potentially positive SLN, and sparing removal of negative lymph nodes decreases pain, sensation loss, and lymphedema compared to traditional axillary lymph node dissection (ALND).

The ACOSOG Z 0011 clinical trial showed that in patients with T1–T2 invasive breast cancer with clinically negative lymph nodes, found to have one to two positive lymph nodes on SLNB, there is no benefit in OS and DFS in performing a complete axillary node dissection. For patients who meet these criteria, a complete ALND can be potentially avoided.

Axillary Lymph Node Dissection

Among patients with clinically negative axillary lymph nodes, 14% will have positive SLNB and will require additional axillary surgery.

Among patients with clinically negative axillary lymph nodes, 14% will have positive SLNB and will require additional axillary surgery.

Axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) is complete surgical removal of level I and II axillary lymph nodes. The goal of ALND is to remove axillary burden of disease.

Axillary lymph node dissection (ALND) is complete surgical removal of level I and II axillary lymph nodes. The goal of ALND is to remove axillary burden of disease.

A complete axillary node dissection is associated with approximately 10% to 25% risk of lymphedema, which can be mild to severe.

A complete axillary node dissection is associated with approximately 10% to 25% risk of lymphedema, which can be mild to severe.

Reconstructive surgery may be used for patients who opt for a mastectomy. It may be done at the time of the mastectomy (immediate reconstruction) or at a later time (delayed reconstruction). Patients diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer and electing to undergo a mastectomy should be offered immediate reconstruction as long as their comorbid conditions do not preclude this intervention. For patients with locally advanced or inflammatory breast cancer, undergoing mastectomy with delayed reconstruction may be the more appropriate management option.

Reconstruction can be done in one of two ways: implant-based (silicone or saline implants) or an autologous tissue graft. Examples of autologous tissue grafts include TRAM (transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous) flaps, the latissimus dorsi flap, and the DIEP (deep inferior epigastric perforator) flap.

Radiotherapy

Radiotherapy (RT) is an integral part of breast-conserving treatment (lumpectomy). It is associated with a large reduction in local recurrence and a positive impact on survival.

Radiotherapy (RT) is an integral part of breast-conserving treatment (lumpectomy). It is associated with a large reduction in local recurrence and a positive impact on survival.

Standard radiation is 45 to 50.4 Gy at 1.8 to 2 Gy per fraction to the whole breast. RT boost to the tumor bed cavity is recommended in patients at higher risk for local failure (based on age, pathology, and margin status). The boost dose is 10 to 16 Gy at 2 Gy per fraction. An alternative hypofractionation schedule is 40 to 42.5 Gy at 2.66 Gy per fraction to the whole breast. This treatment method has been demonstrated to provide comparable cosmetic and oncologic results following breast-conserving surgery in patients with clear surgical margins and negative lymph nodes. Three-dimensional planning, inverse planning for intensity modulation, respiratory control, prone positioning, and proton therapy are techniques employed to minimize cardiac risks for whole breast and postmastectomy chest wall RT in patients with left-sided breast cancer.

Standard radiation is 45 to 50.4 Gy at 1.8 to 2 Gy per fraction to the whole breast. RT boost to the tumor bed cavity is recommended in patients at higher risk for local failure (based on age, pathology, and margin status). The boost dose is 10 to 16 Gy at 2 Gy per fraction. An alternative hypofractionation schedule is 40 to 42.5 Gy at 2.66 Gy per fraction to the whole breast. This treatment method has been demonstrated to provide comparable cosmetic and oncologic results following breast-conserving surgery in patients with clear surgical margins and negative lymph nodes. Three-dimensional planning, inverse planning for intensity modulation, respiratory control, prone positioning, and proton therapy are techniques employed to minimize cardiac risks for whole breast and postmastectomy chest wall RT in patients with left-sided breast cancer.

RT is usually done after chemotherapy when systemic chemotherapy is indicated.

RT is usually done after chemotherapy when systemic chemotherapy is indicated.

Postmastectomy radiation treatment to the chest wall, axillary, supraclavicular- and internal mammary lymph node regions decreases the risk of locoregional recurrence and improves survival in patients with multiple positive lymph nodes and patients with T3 or T4 tumors.

Postmastectomy radiation treatment to the chest wall, axillary, supraclavicular- and internal mammary lymph node regions decreases the risk of locoregional recurrence and improves survival in patients with multiple positive lymph nodes and patients with T3 or T4 tumors.

Two randomized trials showed improvement in OS for postmastectomy radiation in patients with one to three positive lymph nodes, and is being evaluated in more clinical trials. In selected patients, this should be discussed.

Two randomized trials showed improvement in OS for postmastectomy radiation in patients with one to three positive lymph nodes, and is being evaluated in more clinical trials. In selected patients, this should be discussed.

Other indications that may place patients at risk for local-regional failure and drive the decision for postmastectomy radiation include positive margins, extranodal extension and high-grade disease, young age and high-risk biology (e.g., triple-negative disease), and omission of axillary dissection after positive sentinel lymph node biopsy if sufficient information is present without needing to know if additional axillary lymph nodes are involved. ASCO (American Society of Clinical Oncology), ASTRO (American Society for Radiation Oncology), and SSO (Society of Surgical Oncology) updated guidelines for postmastectomy radiation therapy in 2016.

Other indications that may place patients at risk for local-regional failure and drive the decision for postmastectomy radiation include positive margins, extranodal extension and high-grade disease, young age and high-risk biology (e.g., triple-negative disease), and omission of axillary dissection after positive sentinel lymph node biopsy if sufficient information is present without needing to know if additional axillary lymph nodes are involved. ASCO (American Society of Clinical Oncology), ASTRO (American Society for Radiation Oncology), and SSO (Society of Surgical Oncology) updated guidelines for postmastectomy radiation therapy in 2016.

For patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy, those who present with clinically node positive, cT3 or cT4 disease, will typically be recommended for postmastectomy radiation regardless of pathologic response outside of a clinical trial. Biopsy is recommended to confirm clinical suspicion of lymph node involvement prior to the initiation of chemotherapy.

For patients receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy, those who present with clinically node positive, cT3 or cT4 disease, will typically be recommended for postmastectomy radiation regardless of pathologic response outside of a clinical trial. Biopsy is recommended to confirm clinical suspicion of lymph node involvement prior to the initiation of chemotherapy.

Accelerated Partial Breast Irradiation

The primary goal of accelerated partial breast irradiation (APBI) is to shorten the duration of radiation therapy while maintaining adequate local control by targeting the lumpectomy cavity and adjacent at-risk tissue while sparing normal tissues. There are several APBI techniques currently in use and under study, including external beam radiation techniques, intraoperative radiation therapy, and brachytherapy; however, brachytherapy is the most widely used technique. Patients who are clinically felt to be at a lower risk recurrence outside of the lumpectomy site should be selected according to published criteria since the whole breast is not treated. ASTRO and SSO have published guidelines to aid in patient selection, e.g., older patients with Tis or T1 disease, screen-detected, low-intermediate grade, <2.5 cm with margins negative by at least 3 mm. The standard dose for balloon catheter brachytherapy is 34 Gy in 10 fractions delivered twice daily. Phase III data supports the use of intensity modulated external beam radiation therapy delivering 30 Gy in 5 fractions for select patients.

Intraoperative Radiation Therapy (IORT)

Intraoperative radiation therapy (IORT) delivers a concentrated dose of radiation to the tumor bed immediately after the tumor is removed. Two large studies evaluated the role of IORT in women with early-stage breast cancer. In the TARGIT-A study, women ages 45 or older were randomized to receive IORT or whole breast external beam radiation (WBRT) after lumpectomy. Survival rates were similar in both groups but local recurrence was more common in the IORT group. These findings are supported by the ELIOT trial results. In this study, women ages 48 to 75 with tumors ≤ 2.5 cm were randomized to IORT or WBRT, and survival rates were similar in both groups but local recurrence was more common in the IORT group.

Per the 2017 ASTRO/SSO APBI consensus statement update, IORT should be restricted to patients who are also suitable to partial breast radiation, and patients should be counseled that the risk of ipsilateral breast cancer might be higher with IORT.

Adjuvant Systemic Therapy

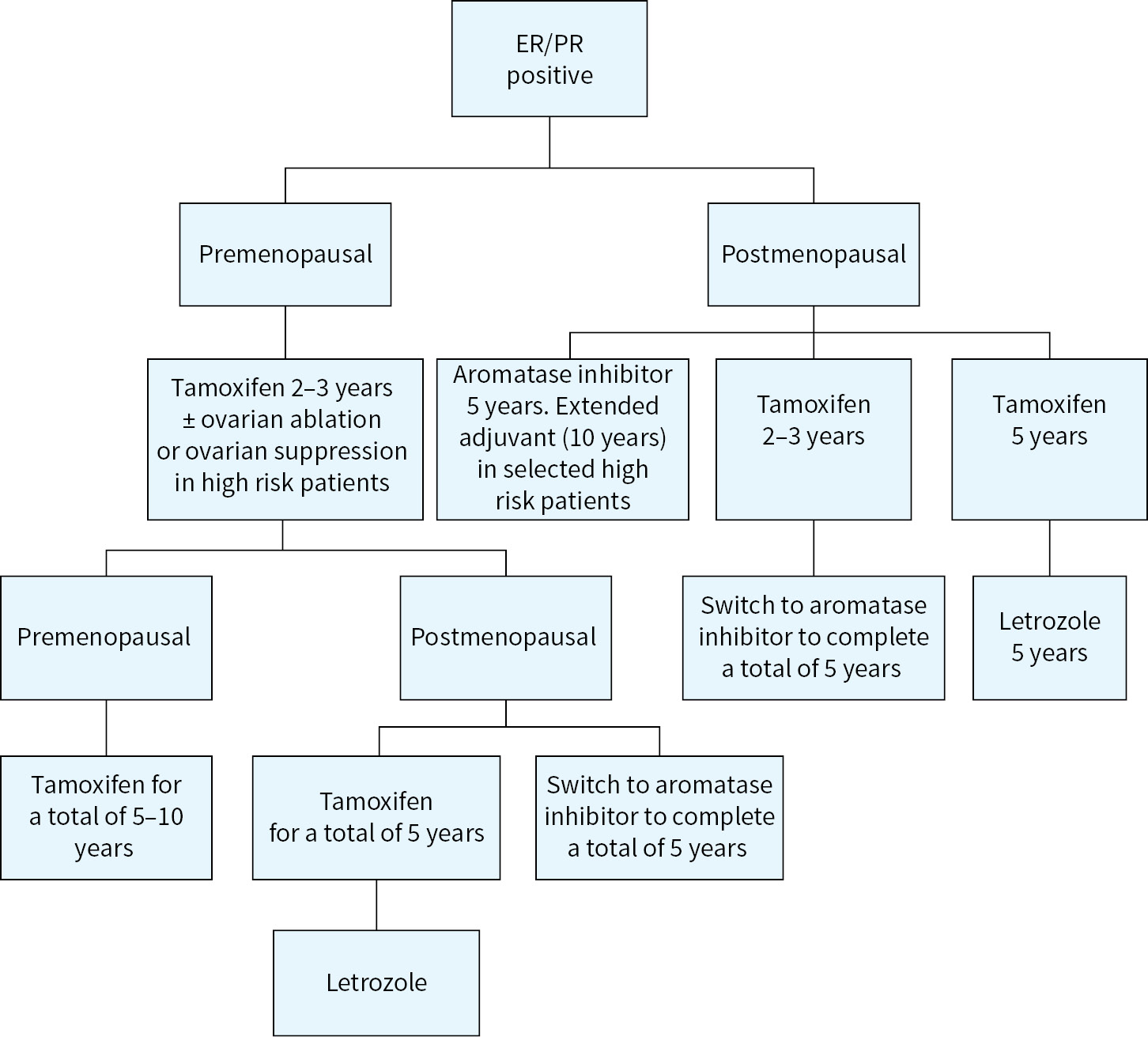

Adjuvant therapy decisions are made after carefully considering patient-related and tumor-related factors. Patient related factors include, age, comorbid conditions, performance status, patient preference, risk–benefit discussion, and life expectancy. Tumor-related factors are tumor size, lymph node status (stage) ER/PR status, Her-2/neu, grade of the tumor and genomic expression profile (e.g.: Oncotype DX, MammaPrint, etc.) (Fig. 12.2).

FIGURE 12.2 Algorithm for systemic adjuvant therapy.

General Principles of Adjuvant Therapy

1.All patients with breast cancer should be screened for potential clinical trials.

2.ER/PR-positive patients should be considered for antiestrogen therapy.

3.HER-2/neu-positive patients should be considered for HER-2/neu-targeted therapy.

4.Chemotherapy should be considered for the following patients (Table 12.3):

a.ER/PR-negative patients

b.Triple negative patients

c.HER-2/neu-positive patients

d.Node-positive patients

e.High-risk patients based upon Oncotype DX, MammaPrint, or other prognostic classification

Adjuvant Therapy in HER-2/neu-Negative Patients

A variety of adjuvant regimens have been used across the world. Depending upon the biology of the tumor, stage of the disease, patient’s health status, comorbid conditions, and chance of recurrence, an optimal regimen can be chosen (Table 12.5). There is no major difference in efficacy among the regimens.

Estrogen or progesterone receptor positive, HER-2 neu negative patients:

A nonanthracycline-containing regimen such as docetaxel and cyclophosphamide (TC) for four to six cycles can be used in ER positive patients who require systemic chemotherapy. The benefit of anthracycline-containing regimens in receptor positive patients is limited. This was illustrated in the ABC (anthracyclines in early breast cancer) trials (combined analysis of USOR 06-090, NSABP B-46 and NSABP B-49) where women with early-stage breast cancer were randomized to TC for six cycles versus standard anthracycline/taxane/cyclophosphamide based chemotherapy. This trial showed the anthracycline-based chemotherapy improved invasive DFS compared to TC for six cycles overall; however, in subgroup analysis, it was found that the benefit of anthracyclines for ER/PR-positive patients was most substantial for those with four or more lymph nodes involved. In high-risk (such as more than four nodes) ER/PR positive patients, an anthracycline-containing regimen such as dose dense AC followed by dose dense Paclitaxel or TAC regimen should be considered.

Estrogen and progesterone receptor negative, HER-2/neu negative (Triple Negative) patients

These patients are often treated with anthracycline-based chemotherapy in the adjuvant setting; however, the ABC trials showed that the greatest benefit of anthracycline-containing chemotherapy for ER/PR-negative patients occurred when patients had one or more lymph nodes involved. For patients with lymph node negative or small tumors (less than 2 cm), TC chemotherapy for four to six cycles can be considered. In high-risk Triple Negative patients, anthracycline-containing regimens, such as Dose Dense AC followed by Dose Dense Paclitaxel or a TAC regimen should be considered. Role of carboplatin in adjuvant triple negative breast cancer is evaluated in NRG 003 clinical trial.

TABLE 12.5 Nontrastuzumab-Containing Combinations

Commonly Used Regimens |

Dose-dense AC followed by dose-dense paclitaxel chemotherapy

Cycled every 14 d for 4 cycles (All cycles are with filgrastim support) Followed by:

Cycled every 14 d for 4 cycles (All cycles are with filgrastim support) |

Dose-dense AC followed by weekly paclitaxel chemotherapy

Cycled every 14 d for 4 cycles (All cycles are with filgrastim support) Followed by:

|

TC chemotherapy

Cycled every 21 d for 4 -6 cycles |

AC chemotherapy

Cycled every 21 d for 4 cycles |

TAC chemotherapy

Cycled every 21 d for 6 cycles (All cycles are with filgrastim support) |

Other Regimens |

FAC chemotherapy

Cycled every 21 d for 6 cycles |

CAF chemotherapy

Cycled every 28 d for 6 cycles |

CEF chemotherapy

Cycled every 28 d for 6 cycles With cotrimoxazole support |

|

Cycled every 28 d for 6 cycles |

AC followed by docetaxel chemotherapy

Cycled every 21 d for 4 cycles Followed by:

Cycled every 21 d for 4 cycles |

EC chemotherapy

Cycled every 21 d for 8 cycles |

FEC followed by docetaxel

Cycled every 21 d for 3 cycles Followed by:

Cycled every 21 d for 3 cycles |

FEC followed by weekly paclitaxel

Cycled every 21 d for 4 cycles Followed by:

|

FAC followed by weekly paclitaxel

Cycled every 21 d for 4 cycles Followed by:

|

TABLE 12.6 Trastuzumab-Containing Regimens

AC followed by T chemotherapy with trastuzumab

Cycled every 21 d for 4 cycles Followed by:

With:

Followed by:

|

TCH chemotherapy with trastuzumab

Cycled every 21 d for 6 cycles With

Followed by:

|

TCHP chemotherapy followed by trastuzumab (+/- pertuzumab)

Cycled every 21 d for 6 cycles With

Followed by:

|

Dose-dense AC followed by dose-dense paclitaxel chemotherapy with trastuzumab

Cycled every 14 d for 4 cycles Followed by:

Cycled every 14 d for 4 cycles (All cycles are with filgrastim support) With

Followed by:

(Cardiac monitoring is recommended before and during treatment) |

Paclitaxel chemotherapy and trastuzumab

With

Followed by:

|

Adapted from NCCN 2017 Guidelines

Adjuvant Therapy in HER-2/neu-Positive Patients

Incorporation of trastuzumab in the adjuvant therapy is the most important development in the treatment of breast cancer in the past 10 to 15 years. The clinical trials that initially showed benefit for the addition of trastuzumab to standard chemotherapy in treatment of HER2+ breast cancer (NSABP B-31 and NCCTG N9831) have published 10 year of follow-up showing 40% improvement in DFS and 37% improvement in OS. Many trastuzumab-containing regimens have been tested and all are equally effective (Table 12.6). The major difference between regimens is in the cardiac toxicity. Nonanthracycline-containing regimens (such as TCH from the BCIRG 006 trial) and the HERA trial regimens (the majority of which were anthracycline based but used sequential rather than concurrent trastuzumab) had less cardiac toxicity compared to other anthracycline-containing regimens. In the adjuvant setting, trastuzumab has only been tested in combination with chemotherapy.

Based upon the long-term follow-up of BCIRG 006 presented at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium in 2015, a nonanthracycline regimen–containing TCH for six cycles could be considered for most patients with her-2 positive disease given the excellent outcomes. In very high-risk patients (multiple lymph nodes and very young patients), an anthracycline-containing regimen such as AC followed by TH or AC-THP can be considered after discussing about potential side effects such as cardiac toxicity and risk of secondary malignancies (MDS and AML).

The APHINITY study presented and published in June 2017, showed that the addition of adjuvant pertuzumab to standard adjuvant trastuzumab-containing regimen for HER2+ breast cancer resulted in a statistically significant, but a small 1.7% improvement in invasive DFS benefit predominantly in the lymph node positive and hormone receptor–negative patients. A 3.2% improvement in invasive DFS was seen in lymph node positive patients versus 0.5% improvement in lymph node negative patients and 1.6% improvement in invasive DFS improvement was seen in hormone receptor–negative patients compared to 0.5% improvement in hormone receptor–positive patients. Addition of pertuzumab was associated with a greater incidence of diarrhea. Given these results, use of adjuvant pertuzumab for one year in addition to trastuzumab can be considered in selected high-risk patients such as those with positive lymph nodes and those that are ER/PR-negative. The added cost should be considered before recommending pertuzumab in adjuvant setting.

In low-risk patients, especially patients with ER-positive, stage I or II tumors, weekly paclitaxel for 12 cycles with trastuzumab is a very reasonable option as per the APT (adjuvant paclitaxel and trastuzumab in node negative HER2 positive breast cancer) study.

Extended HER2-targeted therapy has also been investigated. The ExteNET study tested the irreversible pan-HER inhibitor neratinib 240 mg PO for 12 months in patients who completed standard trastuzumab-based adjuvant therapy and found a 2.3% benefit in 2-year invasive DFS for patients who received neratinib compared to placebo. Interestingly, pre-specified subgroup analysis showed greater benefit in hormone receptor–positive patients compared to hormone receptor–negative patients. Based on these results, the FDA approved neratinib 240 mg daily for 12 months for extended adjuvant treatment of early-stage HER2-positive breast cancer following adjuvant trastuzumab based therapy in July 2017.

Neoadjuvant or Preoperative Chemotherapy

Neoadjuvant or preoperative chemotherapy can be considered for patients with locally advanced breast cancer (IIB, IIIA, IIIB, IIIC), and inflammatory breast cancer. Response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy is much higher in triple negative and her-2 neu positive patients. In patients with stage III disease or inflammatory breast cancer, neoadjuvant therapy is the treatment of choice.

Initial surgery is limited to biopsy to confirm the diagnosis and to identify the ER/PR, HER-2/neu- status, and other prognostic features.

Initial surgery is limited to biopsy to confirm the diagnosis and to identify the ER/PR, HER-2/neu- status, and other prognostic features.