Kevin R. Rice, Michelle A. Ojemuyiwa, and Ravi A. Madan

INTRODUCTION

Germ cell tumors (GCT) comprise 95% of testicular neoplasms. Testicular GCT is the most common malignancy in men between the ages of 20 and 35, but represents only 1% of all malignancies in males. The disease is believed to originate from the malignant transformation of primordial germ cells that may occur early in embryonic development. Testicular GCT is divided in seminoma and nonseminomatous germ cell tumors (NSGCT) due to distinct clinical behavior and treatment paradigms. As late as the 1970s, metastatic testicular carcinoma was associated with a 20% survival. However, subsequent demonstration of testicular cancer’s marked sensitivity to cisplatin-based chemotherapeutic regimens has led to cancer-specific survival rates of >99% for early-stage disease and >90% for disseminated testicular cancer. Given these high cure rates, a considerable amount research effort has been directed at minimizing treatment-related toxicity, improving functional outcomes, and appropriately tailoring post diagnosis/treatment surveillance based on likelihood of recurrence. Despite these favorable outcomes, one cannot overemphasize the importance of rigorous adherence to the latest guidelines for post-treatment surveillance in maximizing oncologic and functional outcomes.

CLINICAL FEATURES

Epidemiology

It was estimated that in 2016 there would be 8720 new cases of testicular carcinoma and 380 deaths due to the disease in the United States.

It was estimated that in 2016 there would be 8720 new cases of testicular carcinoma and 380 deaths due to the disease in the United States.

Testicular cancer accounts for 1% of all malignancies in men but the majority of cases occur between the ages of 20 to 35 years. NSGCT peaks in the third decade while seminoma peaks in the fourth decade. Testicular GCT is rare after age 40.

Testicular cancer accounts for 1% of all malignancies in men but the majority of cases occur between the ages of 20 to 35 years. NSGCT peaks in the third decade while seminoma peaks in the fourth decade. Testicular GCT is rare after age 40.

There is significant variability in the incidence by ethnicity with American Caucasians being 5 times more likely than African Americans, 4 times more likely than Asian Americans, and 1.3 times more likely than Hispanics to develop testicular GCT.

There is significant variability in the incidence by ethnicity with American Caucasians being 5 times more likely than African Americans, 4 times more likely than Asian Americans, and 1.3 times more likely than Hispanics to develop testicular GCT.

For unclear reasons, the incidence of testicular cancer has been increasing over the past four to five decades in most western countries.

For unclear reasons, the incidence of testicular cancer has been increasing over the past four to five decades in most western countries.

Risk Factors

Cryptorchidism: Cryptorchid testis, defined as a maldescended testis located above the external inguinal ring, is associated with a 4- to 6-fold increase in the risk of testicular cancer with intra-abdominal testes having a higher risk than inguinal testes. Performance of orchiopexy before puberty is now thought to decrease risk of GCT development. There is also an increased risk of developing GCT in the normally-descended contralateral testis.

Cryptorchidism: Cryptorchid testis, defined as a maldescended testis located above the external inguinal ring, is associated with a 4- to 6-fold increase in the risk of testicular cancer with intra-abdominal testes having a higher risk than inguinal testes. Performance of orchiopexy before puberty is now thought to decrease risk of GCT development. There is also an increased risk of developing GCT in the normally-descended contralateral testis.

Second primary tumors: Synchronous or metachronous testicular carcinoma may occur in the contralateral testis in a few group of patients; 1% to 5% of patients have bilateral disease at presentation. After treatment of testicular cancer, patients should be counseled that they have an approximately 2% chance of metachronous contralateral GCT.

Second primary tumors: Synchronous or metachronous testicular carcinoma may occur in the contralateral testis in a few group of patients; 1% to 5% of patients have bilateral disease at presentation. After treatment of testicular cancer, patients should be counseled that they have an approximately 2% chance of metachronous contralateral GCT.

Intratubular germ cell neoplasia (ITGCN): A premalignant condition seen in 90% of testicular carcinomas (not typically seen with spermatocytic seminoma). The finding of ITGCN on testis biopsy is associated with an at least 50% chance of development of ipsilateral GCT at 5 years and 70% at 7 years. ITGCN is believed to be present in at least 5% of contralateral testicles at the time of orchiectomy for GCT.

Intratubular germ cell neoplasia (ITGCN): A premalignant condition seen in 90% of testicular carcinomas (not typically seen with spermatocytic seminoma). The finding of ITGCN on testis biopsy is associated with an at least 50% chance of development of ipsilateral GCT at 5 years and 70% at 7 years. ITGCN is believed to be present in at least 5% of contralateral testicles at the time of orchiectomy for GCT.

Hereditary: Despite the overwhelming evidence of a strong familial component to the risk of testicular carcinoma, to date, no definite oncogene has been identified. About 1.4% of patients with testicular carcinoma have a positive family history of the disease. A son of an affected father has a 4- to 6-fold increased risk while for a brother of an affected sibling the risk increases to 8- to 10-fold. The risk is reportedly greater than 70-fold in monozygotic twins.

Hereditary: Despite the overwhelming evidence of a strong familial component to the risk of testicular carcinoma, to date, no definite oncogene has been identified. About 1.4% of patients with testicular carcinoma have a positive family history of the disease. A son of an affected father has a 4- to 6-fold increased risk while for a brother of an affected sibling the risk increases to 8- to 10-fold. The risk is reportedly greater than 70-fold in monozygotic twins.

Chromosomal abnormalities: Klinefelter syndrome has been shown to be associated with increased risk of primary mediastinal germ cell tumors in a few case series and surveys. Similar studies have also suggested the possibility of an increased risk of testicular cancer with Down syndrome. Additionally, disorders of sexual differentiation (DSD) are associated with a variable increased risk of developing GCT when a Y-chromosome is present. The typical pre-GCT neoplasm in these patients is gonadoblastoma. For this reason, prophylactic gonadectomy is often recommended before puberty for abnormal or streak gonads.

Chromosomal abnormalities: Klinefelter syndrome has been shown to be associated with increased risk of primary mediastinal germ cell tumors in a few case series and surveys. Similar studies have also suggested the possibility of an increased risk of testicular cancer with Down syndrome. Additionally, disorders of sexual differentiation (DSD) are associated with a variable increased risk of developing GCT when a Y-chromosome is present. The typical pre-GCT neoplasm in these patients is gonadoblastoma. For this reason, prophylactic gonadectomy is often recommended before puberty for abnormal or streak gonads.

Viral infections: Possible associations between Epstein-Barr (EBV), Cytomegalovirus (CMV), and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and testicular cancer have been reports, although most associations are modest or inconclusive. The risk of seminomatous testicular tumors is considerably higher in HIV-infected men compared to age-matched HIV-negative men. There are also recent reports of non-Hodgkin lymphoma of the testicles in patients with HIV infection.

Viral infections: Possible associations between Epstein-Barr (EBV), Cytomegalovirus (CMV), and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and testicular cancer have been reports, although most associations are modest or inconclusive. The risk of seminomatous testicular tumors is considerably higher in HIV-infected men compared to age-matched HIV-negative men. There are also recent reports of non-Hodgkin lymphoma of the testicles in patients with HIV infection.

Hypospadias: Analyses of data from Danish health registry have suggested a potential association between hypospadias and testicular tumor.

Hypospadias: Analyses of data from Danish health registry have suggested a potential association between hypospadias and testicular tumor.

The opinions expressed in this chapter represent those of the authors and do not necessarily represent official positions or opinions of the US government or of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Presentation

Asymptomatic testicular nodule or swelling (painful in 10% to 20% of patients)

Asymptomatic testicular nodule or swelling (painful in 10% to 20% of patients)

Feeling of testicular heaviness, dull ache, and/or hardness (up to 40% of patients)

Feeling of testicular heaviness, dull ache, and/or hardness (up to 40% of patients)

Disease at extragonadal site (5% to 10% of patients; symptoms vary with site):

Disease at extragonadal site (5% to 10% of patients; symptoms vary with site):

•Dyspnea, cough, or hemoptysis (pulmonary metastases)

•Weight loss, anorexia, nausea, abdominal, or back pain (retroperitoneal adenopathy)

•Mass or swelling in neck (left-sided supraclavicular lymphadenopathy)

•Superior vena cava syndrome due to mediastinal disease

Rare presentations:

Rare presentations:

•Urinary obstruction

•Headaches, seizures, or other neurologic complaints due to brain metastases

•Bone pain due to bone metastases

•Gynecomastia due to elevated β-human chorionic gonadotropin (β-HCG).

•Anti-Ma2-associated paraneoplastic encephalitis

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Epididymitis (initial diagnosis and treatment in 18% to 33% of testicular cancer patients)

Epididymitis (initial diagnosis and treatment in 18% to 33% of testicular cancer patients)

Testicular trauma (GCT often comes to attention after trauma to the testis)

Testicular trauma (GCT often comes to attention after trauma to the testis)

Orchitis, hydrocele, varicocele, or spermatocele

Orchitis, hydrocele, varicocele, or spermatocele

Paratesticular neoplasm (can be benign or malignant)

Paratesticular neoplasm (can be benign or malignant)

Testicular torsion

Testicular torsion

Metastasis from other tumors including melanoma or lung cancer

Metastasis from other tumors including melanoma or lung cancer

Infectious diseases including tuberculosis and tertiary syphilis causing gumma

Infectious diseases including tuberculosis and tertiary syphilis causing gumma

DIAGNOSIS

The initial evaluation of a suspicious testicular mass should include measurement of serum tumor markers—alphafetoprotein (AFP), beta-human chorionic gonadotropin (β-HCG), and serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and —testicular ultrasound, and a chest x-ray. Subsequently, if findings support a testicular tumor, a radical inguinal orchiectomy should be performed. Postoperatively, if germ cell tumor is confirmed, an abdominopelvic CT scan should be performed and serum tumor markers should be repeated. Chest CT should be performed for abnormalities on preoperative chest film, pulmonary symptoms, or if retroperitoneal/abdominal disease is noted on staging CT of the abdomen/pelvis. Brain imaging is generally only indicated for neurologic symptoms or for high-stage disease with markedly elevated serum tumor markers. This is particularly important in the setting of significant HCG elevation, as this usually indicates the presence of choriocarcinoma, which has a propensity for widespread hematogenous dissemination.

Goals

Expediency—Every testicular mass requires a timely workup to exclude testicular carcinoma. Delay in diagnosis can lead to disease progression, increasing treatment toxicity and leading to poorer oncologic and functional outcomes. Thus, urgent referral to urology should be standard.

Expediency—Every testicular mass requires a timely workup to exclude testicular carcinoma. Delay in diagnosis can lead to disease progression, increasing treatment toxicity and leading to poorer oncologic and functional outcomes. Thus, urgent referral to urology should be standard.

Appropriate diagnostic evaluation—Avoid unnecessary diagnostic tests in patients where the diagnosis of testicular cancer is unclear. Similarly, avoid unnecessary imaging in low-stage, low-risk patients (i scans or CNS imaging).

Appropriate diagnostic evaluation—Avoid unnecessary diagnostic tests in patients where the diagnosis of testicular cancer is unclear. Similarly, avoid unnecessary imaging in low-stage, low-risk patients (i scans or CNS imaging).

Fertility—If future paternity is desired by the patient, provide him the opportunity and resources to bank sperm prior to orchiectomy in all but the most advanced and ominous cases.

Fertility—If future paternity is desired by the patient, provide him the opportunity and resources to bank sperm prior to orchiectomy in all but the most advanced and ominous cases.

Appropriate surgical approach—radical inguinal orchiectomy is the standard of care. There is no role for transscrotal orchiectomy, biopsy, or fine-needle aspiration due to potential scrotal contamination, inadequate local control of the spermatic cord, and inadequate tissue sampling.

Appropriate surgical approach—radical inguinal orchiectomy is the standard of care. There is no role for transscrotal orchiectomy, biopsy, or fine-needle aspiration due to potential scrotal contamination, inadequate local control of the spermatic cord, and inadequate tissue sampling.

Laboratory

A glycoprotein with a half-life of approximately 4 to 6 days.

A glycoprotein with a half-life of approximately 4 to 6 days.

Commonly produced by the fetal yolk sac, liver, and gastrointestinal tract.

Commonly produced by the fetal yolk sac, liver, and gastrointestinal tract.

Should not be elevated in serum of healthy men. Can be elevated in setting of liver disease/malignancy. Alcohol intake should be determined and a liver function panel should be sent in cases of mild elevation.

Should not be elevated in serum of healthy men. Can be elevated in setting of liver disease/malignancy. Alcohol intake should be determined and a liver function panel should be sent in cases of mild elevation.

Can be produced by yolk sac tumor and embryonal cell carcinoma.

Can be produced by yolk sac tumor and embryonal cell carcinoma.

Not present in patients with pure seminoma. Elevated serum α-fetoprotein (AFP) levels indicate a nonseminomatous component to the patient’s testicular cancer. Thus, patients with AFP elevation should be managed as NSGCT even when testicular specimen demonstrates pure seminoma.

Not present in patients with pure seminoma. Elevated serum α-fetoprotein (AFP) levels indicate a nonseminomatous component to the patient’s testicular cancer. Thus, patients with AFP elevation should be managed as NSGCT even when testicular specimen demonstrates pure seminoma.

Serum β-Human Chorionic Gonadotropin

Secreted by syncytiotrophoblasts; half-life of 0.5 to 1.5 days.

Secreted by syncytiotrophoblasts; half-life of 0.5 to 1.5 days.

Most commonly elevated tumor marker in patients with testicular cancer.

Most commonly elevated tumor marker in patients with testicular cancer.

Present in choriocarcinomas; may be modestly elevated in approxiatel 15% of pure seminomas due to presence of syncytiotrophoblastic blood islands.

Present in choriocarcinomas; may be modestly elevated in approxiatel 15% of pure seminomas due to presence of syncytiotrophoblastic blood islands.

High levels may lead to gynecomastia.

High levels may lead to gynecomastia.

False positives may be seen in patients with low testosterone due to cross reactivity of luteinizing hormone (LH) with the β-HCG assay. Thus, if β-HCG is elevated after orchiectomy for solitary testicle or if remaining testicle is atrophic/soft, serum testosterone should be analyzed and if low, IM testosterone 200 mcg should be administered. β-HCG can then be rechecked in 1 week.

False positives may be seen in patients with low testosterone due to cross reactivity of luteinizing hormone (LH) with the β-HCG assay. Thus, if β-HCG is elevated after orchiectomy for solitary testicle or if remaining testicle is atrophic/soft, serum testosterone should be analyzed and if low, IM testosterone 200 mcg should be administered. β-HCG can then be rechecked in 1 week.

Nonspecific tumor marker in testicular cancer

Nonspecific tumor marker in testicular cancer

Elevated in 80% of metastatic seminomas and 60% of advanced nonseminomatous tumors

Elevated in 80% of metastatic seminomas and 60% of advanced nonseminomatous tumors

Reflects overall tumor burden, tumor growth rate, and cellular proliferation

Reflects overall tumor burden, tumor growth rate, and cellular proliferation

Imaging

Testicular Ultrasound: evaluates for the presence of testicular parenchymal abnormality.

Testicular Ultrasound: evaluates for the presence of testicular parenchymal abnormality.

Chest x-ray: Posterior–anterior and lateral film evaluation for pulmonary metastases and evidence of mediastinal adenopathy if widened mediastinum is seen.

Chest x-ray: Posterior–anterior and lateral film evaluation for pulmonary metastases and evidence of mediastinal adenopathy if widened mediastinum is seen.

Computerized tomography (CT): CT scans of chest, abdomen, and pelvis determine extragonadal metastasis and are the most effective modality for staging the disease. However, a plain posterior anterior film of the chest can be substituted for the Chest CT in clinical stage I disease to minimize radiation load.

Computerized tomography (CT): CT scans of chest, abdomen, and pelvis determine extragonadal metastasis and are the most effective modality for staging the disease. However, a plain posterior anterior film of the chest can be substituted for the Chest CT in clinical stage I disease to minimize radiation load.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): Testicular MRI may provide additional information if ultrasound is indeterminate, although this scenario is extremely rare. MRI of the brain is necessary only when there are symptoms involving the central nervous system (e.g., headache, neurologic deficit, seizure).

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): Testicular MRI may provide additional information if ultrasound is indeterminate, although this scenario is extremely rare. MRI of the brain is necessary only when there are symptoms involving the central nervous system (e.g., headache, neurologic deficit, seizure).

Positron emission tomography (PET) scan: PET scans are not indicated in primary staging, but may have limited utility for characterizing postchemotherapy/postradiotherapy residual masses in pure seminoma patients (see below). The routine use of PET scans has not been shown to improve outcome in NSGCT.

Positron emission tomography (PET) scan: PET scans are not indicated in primary staging, but may have limited utility for characterizing postchemotherapy/postradiotherapy residual masses in pure seminoma patients (see below). The routine use of PET scans has not been shown to improve outcome in NSGCT.

Pathology

Patients with testicular masses should have surgical exploration, with complete removal of the testis and spermatic cord up to the internal inguinal ring. Transscrotal orchiectomy or testicular biopsy are not recommended due to incomplete control of the spermatic cord in the inguinal canal as well as the theoretical risk of scrotal seeding of tumor cells.

GCTs can be composed of pure histologies or combinations of 5 histologic subtypes Table 16.1:

GCTs can be composed of pure histologies or combinations of 5 histologic subtypes Table 16.1:

•Seminoma

•Embryonal cell carcinoma

•Yolk sac tumor

•Choriocarcinoma

•Teratoma

Immunohistochemical staining can be used to distinguish the different histologic subtypes of testicular carcinoma. While an experienced genitourinary pathologist is able to distinguish subtypes of GCT based on morphologic features alone in the great majority of cases, immunohistochemical staining can be used to confirm diagnoses in difficult cases.

Immunohistochemical staining can be used to distinguish the different histologic subtypes of testicular carcinoma. While an experienced genitourinary pathologist is able to distinguish subtypes of GCT based on morphologic features alone in the great majority of cases, immunohistochemical staining can be used to confirm diagnoses in difficult cases.

Several genes (either deleted or amplified) located on isochromosome 12p have been implicated in the malignant transformation of primordial germ cells. Among patients with familial testicular germ cell tumors compatible with X-linked inheritance, evidence suggests the presence of a susceptibility gene on chromosome Xq27.

Several genes (either deleted or amplified) located on isochromosome 12p have been implicated in the malignant transformation of primordial germ cells. Among patients with familial testicular germ cell tumors compatible with X-linked inheritance, evidence suggests the presence of a susceptibility gene on chromosome Xq27.

TABLE 16.1 Histopathologic Characteristics of Testicular tumors

Tumor Type | Percentage | Pathologic Feature(s) | Percentage |

Germ cell tumors | 95 | Seminomas | 40–50 |

Single cell–type tumors | 60 | Primordial germ cell |

|

Mixed cell–type tumors | 40 | Nonseminomas | 50–60 |

|

| Embryonal cell tumors |

|

|

| Yolk sac tumors |

|

|

| Teratomas |

|

|

| Choriocarinomas |

|

Tumors of gonadal stroma | 1–2 | Leydig cell |

|

|

| Sertoli cell |

|

|

| Granulosa cell |

|

|

| Primitive gonadal structures |

|

Gonadoblastoma | 1 | Germ cell + stromal cell |

|

STAGING

Staging is in accordance with the American Joint Committee on Cancer tumor/node/metastasis (TNM) criteria.

T classification is based on pathological finding after radical orchiectomy, hence pT nomenclature. pT0 means there is no evidence of disease. pTis refers to intratubular germ cell neoplasia or carcinoma in situ. pT1 refers to disease limited to the testis and epididymis without lymphovascular invasion, although it may invade the tunica albuginea but the tunica vaginalis. pT2 tumor is similar to pT1 but with lymphovascular invasion or the involvement of the tunica vaginalis. In pT3 tumor, there is invasion of the spermatic cord with or without lymphovascular invasion. Involvement of the scrotum with or without lymphovascular invasion is designated as pT4. pTx is used when the primary tumor cannot be assessed.

T classification is based on pathological finding after radical orchiectomy, hence pT nomenclature. pT0 means there is no evidence of disease. pTis refers to intratubular germ cell neoplasia or carcinoma in situ. pT1 refers to disease limited to the testis and epididymis without lymphovascular invasion, although it may invade the tunica albuginea but the tunica vaginalis. pT2 tumor is similar to pT1 but with lymphovascular invasion or the involvement of the tunica vaginalis. In pT3 tumor, there is invasion of the spermatic cord with or without lymphovascular invasion. Involvement of the scrotum with or without lymphovascular invasion is designated as pT4. pTx is used when the primary tumor cannot be assessed.

N classification is based on lymph node involvement and may be pathologic (pN) or clinical. When there is no regional lymph node involvement, the N0 designation is used. N1 refers to metastasis with a lymph node mass of 2 cm or less in greatest dimension. N2 is a lymph node metastasis or multiple lymph nodes metastasis with any one mass greater than 2 cm but not more than 5 cm in greatest dimension. Lymph node metastasis greater than 5 cm is termed N3. If a lymph node metastasis is ascertained pathologically after surgery, it is termed as pN nomenclature is used. pN0 means no evidence of lymph node involvement, while pN1 refers to involvement of less than 5 lymph nodes with none greater than 2 cm. Likewise, pN2 is similar to N2 but also include the involvement of more than 5 lymph nodes, none more than 5 cm or evidence of extra nodal extension. pN3 has similar definition as N3. When regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed the Nx or pNx designation is used.

N classification is based on lymph node involvement and may be pathologic (pN) or clinical. When there is no regional lymph node involvement, the N0 designation is used. N1 refers to metastasis with a lymph node mass of 2 cm or less in greatest dimension. N2 is a lymph node metastasis or multiple lymph nodes metastasis with any one mass greater than 2 cm but not more than 5 cm in greatest dimension. Lymph node metastasis greater than 5 cm is termed N3. If a lymph node metastasis is ascertained pathologically after surgery, it is termed as pN nomenclature is used. pN0 means no evidence of lymph node involvement, while pN1 refers to involvement of less than 5 lymph nodes with none greater than 2 cm. Likewise, pN2 is similar to N2 but also include the involvement of more than 5 lymph nodes, none more than 5 cm or evidence of extra nodal extension. pN3 has similar definition as N3. When regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed the Nx or pNx designation is used.

M classification is based on the extent of distant metastasis. M0 means there is no distant metastasis, while M1, which is further divided to M1a and M1b, signifies distant metastasis. M1a refers to nonregional nodal or pulmonary metastasis, while M1b indicates distant metastasis other than nonregional lymph nodes and lung.

M classification is based on the extent of distant metastasis. M0 means there is no distant metastasis, while M1, which is further divided to M1a and M1b, signifies distant metastasis. M1a refers to nonregional nodal or pulmonary metastasis, while M1b indicates distant metastasis other than nonregional lymph nodes and lung.

Unique to testicular germ cell tumors is the use of serum tumor markers in the staging process. S0 refers to normal serum levels of tumor markers. S1 indicates that the lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) is <1.5 times the upper limit of normal, BHCG is <5,000 milli-international units/ml, and AFP is <1000 ng/ml. S2 is used when the LDH is between 1.5 and 10 times the upper limit of normal, or B-HCG is between 5,000 and 50,000 milli-international units/mL, or AFP 1,000 to 10,000 ng/mL. S3 refers to LDH >10 times the upper limit of normal, or BHCG >50,000 milli-international units/mL or AFP >10, 000 ng/mL. Sx refers to tumor markers not available or not completed.

Unique to testicular germ cell tumors is the use of serum tumor markers in the staging process. S0 refers to normal serum levels of tumor markers. S1 indicates that the lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) is <1.5 times the upper limit of normal, BHCG is <5,000 milli-international units/ml, and AFP is <1000 ng/ml. S2 is used when the LDH is between 1.5 and 10 times the upper limit of normal, or B-HCG is between 5,000 and 50,000 milli-international units/mL, or AFP 1,000 to 10,000 ng/mL. S3 refers to LDH >10 times the upper limit of normal, or BHCG >50,000 milli-international units/mL or AFP >10, 000 ng/mL. Sx refers to tumor markers not available or not completed.

The TNM classification is then used in the anatomic stage grouping as follows:

The TNM classification is then used in the anatomic stage grouping as follows:

•Stage I: pT1-4, N0, M0, Sx/S0

•Stage Ia: pT1, N0, M0, Sx/0

•Stage Ib: pT2-4, N0, M0, Sx/0

•Stage IS: Any p T/Tx, N0, M0, S1-3

•Stage II: Any pT/Tx, N1-3, M0, Sx/S0-1

•Stage IIa: Any pT/Tx, N1, M0, S0-1

•Stage IIb, Any pT/Tx, N2, M0, S0-1

•Stage IIc, Any pT/Tx, N3, S0-1

•Stage III: Any pT/Tx, any N, M1, Sx/S0-3

•Stage IIIa: Any pT/Tx, Any N, M1a, S0-1

•Stage IIIb: Any pT/Tx, AND N0-3, M1a, S2 OR N1-3, M0, S2

•Stage IIIc: Any pT/Tx, N0-3, M1b, Any S OR M1a, S3 OR N1-3, Any M and S3

PROGNOSIS

Patients with clinical stage Ia and Ib GCT have a 99% to 100% survival. The prognosis for patients with metastatic disease GCT can be estimated by utilizing the international germ cell consensus classification system developed by the International Germ Cell Cancer Collaborative Group (IGCCCG) and published in 1997. This system utilizes postorchiectomy levels of tumor markers, site of primary tumor (for NSGCT) and the site of metastasis (pulmonary vs. nonpulmonary visceral metastases) to predict the progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) (Table 16.2).

Patients with clinical stage Ia and Ib GCT have a 99% to 100% survival. The prognosis for patients with metastatic disease GCT can be estimated by utilizing the international germ cell consensus classification system developed by the International Germ Cell Cancer Collaborative Group (IGCCCG) and published in 1997. This system utilizes postorchiectomy levels of tumor markers, site of primary tumor (for NSGCT) and the site of metastasis (pulmonary vs. nonpulmonary visceral metastases) to predict the progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) (Table 16.2).

The 5-year PFS and 5-year OS for disseminated seminomatous and nonseminomatous germ cell tumors are given in Table 16.3. However, it should be noted that many patients included in development and validation of the IGCCCG model were treated in the early cisplatin-era. Thus, survival is likely underestimated in this model. For example, a more contemporary review of 273 poor risk patients treated at a referral center revealed IGCCCG poor risk patients to demonstrate a 73% 5-year OS and 58% 5-year PFS.

The 5-year PFS and 5-year OS for disseminated seminomatous and nonseminomatous germ cell tumors are given in Table 16.3. However, it should be noted that many patients included in development and validation of the IGCCCG model were treated in the early cisplatin-era. Thus, survival is likely underestimated in this model. For example, a more contemporary review of 273 poor risk patients treated at a referral center revealed IGCCCG poor risk patients to demonstrate a 73% 5-year OS and 58% 5-year PFS.

TABLE 16.2 International Consensus Risk Classification for Germ Cell Tumors

Prognosis | Nonseminoma | Seminoma |

Good | Testis/retroperitoneal primary. No nonpulmonary visceral metastases. AFP <1,000 mg/mL; HCG <5,000 international units/L (1,000 mg/mL); LDH <1.5 × ULN (56% of all nonseminomas) | Any primary site. No nonpulmonary visceral metastases. Normal AFP; any concentration of HCG; any concentration of LDH (90% of all seminomas) |

Intermediate | Testis/retroperitoneal primary. No nonpulmonary visceral metastases. AFP ≥1,000 and ≤10,000 ng/mL or HCG ≥5,000 milli-International units/milliliter (mIU/mL) and ≤50,000 international units/L or LDH = 1.5 × NL and ≥10 × NL (28% of all nonseminomas) | Any primary site. No nonpulmonary visceral metastases. Normal AFP; any concentration of HCG; any concentration of LDH (10% of all seminomas) |

Poor | Mediastinal primary or nonpulmonary visceral metastases or AFP >10,000 ng/mL or HCG >50,000 international units/L (10,000 ng/mL) or LDH >10 × ULN (16% of all nonseminomas) | No patients classified as poor prognosis |

LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; HCG, human chorionic gonadotropin; AFP, α-fetoprotein; ULN, upper limit of normal; NL, normal limit.

TABLE 16.3 Expected Survival for Disseminated Disease

| 5-y Progression-Free Survival (%) | 5-y Overall Survival (%) | ||

Prognosis | Seminoma | Nonseminoma | Seminoma | Nonseminoma |

Good | 82 | 89 | 86 | 92 |

Intermediate | 67 | 75 | 72 | 80 |

Poora | — | 41 | — | 48 |

aThere is no poor prognosis category for seminoma.

TREATMENT MODALITIES

Radical inguinal orchiectomy is the preferred surgical approach for all patients with a testicular mass for reasons described previously. This is both a diagnostic and therapeutic procedure. Adjuvant therapy, which may include chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or further surgery, is tailored to the disease stage and histology. Radiation therapy is only offered to pure seminoma patient due to known radiosensitivity and very low likelihood of radioresistant (and chemoresistant) teratomatous elements. The need for adjuvant therapy after orchiectomy in clinical stage I disease is generally not recommended in pure seminoma and Stage Ia NSGCT patients. The use of adjuvant therapy in Stage Ib NSGCT is controversial.

Pure Seminoma

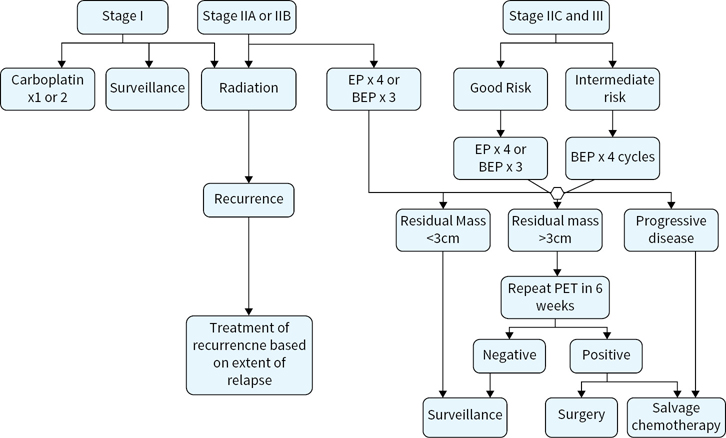

Adjuvant treatment options for seminoma are outlined in Figure 16.1.

FIGURE 16.1 Adjuvant treatment options for seminoma. Radiation*, radiation therapy to para-aortic lymph nodes; BEP, bleomycin, etoposide, and cisplatin; EP, etoposide, and cispaltin; PET positron emission tomography.

Orchiectomy is curative in 80% to 85% of patients with clinical stage (CS) I seminoma.

Orchiectomy is curative in 80% to 85% of patients with clinical stage (CS) I seminoma.

Postorchiectomy management options include 1) surveillance, 2) radiotherapy, and 3) single agent carboplatin.

Postorchiectomy management options include 1) surveillance, 2) radiotherapy, and 3) single agent carboplatin.

Risk factors for recurrence of CS I seminoma include primary tumor size of >4cm and rete testis invasion. When one or both factors are present, recurrence rate increases to approximately 30%.

Risk factors for recurrence of CS I seminoma include primary tumor size of >4cm and rete testis invasion. When one or both factors are present, recurrence rate increases to approximately 30%.

Adjuvant treatment with radiotherapy to the para-aortic lymph nodes or single agent carboplatin both increase recurrence-free survival (RFS) to approximately 94%.

Adjuvant treatment with radiotherapy to the para-aortic lymph nodes or single agent carboplatin both increase recurrence-free survival (RFS) to approximately 94%.

With a recurrence rate of <20% and OS of 99% to 100% regardless of postorhiectomy management strategy, active surveillance is the preferred postorchiectomy management option. Risk-adapted utilization of posthorchiectomy adjuvant therapy is generally not recommended. Rather, physicians and patients must discuss the short-term and long-term advantages and disadvantages of surveillance versus chemotherapy or radiation in CS I seminoma. All patients must understand the need to comply with surveillance protocols.

With a recurrence rate of <20% and OS of 99% to 100% regardless of postorhiectomy management strategy, active surveillance is the preferred postorchiectomy management option. Risk-adapted utilization of posthorchiectomy adjuvant therapy is generally not recommended. Rather, physicians and patients must discuss the short-term and long-term advantages and disadvantages of surveillance versus chemotherapy or radiation in CS I seminoma. All patients must understand the need to comply with surveillance protocols.

Disease relapse typically occurs in the retroperitoneal lymph nodes and nearly all patients are successfully salvaged with radiation or chemotherapy.

Disease relapse typically occurs in the retroperitoneal lymph nodes and nearly all patients are successfully salvaged with radiation or chemotherapy.

For stage IIA–B seminoma, postorchiectomy-managed options include external beam radiation or induction cisplatin-based chemotherapy (IGCCCG good risk). Both radiation therapy (30 Gy for stage IIA; 36 Gy for stage IIB) to ipsilateral iliac and retroperitoneal lymph nodes (“modified dog-leg”) and induction chemotherapy are associated with a 90% RFS.

For stage IIA–B seminoma, postorchiectomy-managed options include external beam radiation or induction cisplatin-based chemotherapy (IGCCCG good risk). Both radiation therapy (30 Gy for stage IIA; 36 Gy for stage IIB) to ipsilateral iliac and retroperitoneal lymph nodes (“modified dog-leg”) and induction chemotherapy are associated with a 90% RFS.

In general, radiation therapy is preferred for stage IIA patients. However, in select stage IIA cases where radiation is contraindicated (i.e., horseshoe kidney, inflammatory bowel disease, or history of abdominal/retroperitoneal radiation) or when the patient’s preference is to avoid radiation, IGCCCG good risk cisplatin-based chemotherapy is appropriate. For stage IIB serminoma, IGCCCG good risk cisplatin-based chemotherapy can be utilized as an equivalent (and perhaps superior) alternative to radiation therapy.

In general, radiation therapy is preferred for stage IIA patients. However, in select stage IIA cases where radiation is contraindicated (i.e., horseshoe kidney, inflammatory bowel disease, or history of abdominal/retroperitoneal radiation) or when the patient’s preference is to avoid radiation, IGCCCG good risk cisplatin-based chemotherapy is appropriate. For stage IIB serminoma, IGCCCG good risk cisplatin-based chemotherapy can be utilized as an equivalent (and perhaps superior) alternative to radiation therapy.

Patients with stage II seminoma may be treated with IGCCCG good risk chemotherapy regimens, which include three cycles of bleomycin, etoposide, and cisplatin (BEP) or four cycles of etoposide and cisplatin (EP).

Patients with stage II seminoma may be treated with IGCCCG good risk chemotherapy regimens, which include three cycles of bleomycin, etoposide, and cisplatin (BEP) or four cycles of etoposide and cisplatin (EP).

There is no evidence that the combination of both radiation and chemotherapy increases RFS or OS.

There is no evidence that the combination of both radiation and chemotherapy increases RFS or OS.

Stages IIC and III seminoma are curable in most cases. Even intermediate risk pure seminoma is associated with a >70% 5-year cancer-specific survival. These patients should be managed with full induction courses of cisplatin-based chemotherapy following radical orchiectomy. Patients with IGCCCG good risk disease may be treated with three cycles of BEP or four cycles of EP; intermediate risk patients (nonpulmonary visceral metastases) should be treated with four cycles of BEP or four cycles of etoposide, ifosfamide, and cisplatin (VIP) if bleomycin is contraindicated.

Management of residual retroperitoneal masses after radiation and/or chemotherapy:

In most cases, a residual mass after treatment of seminoma with radiation or systemic chemotherapy does not indicate persistent disease. Rather, it tends to be a manifestation of the dense desmoplastic reaction that this tumor has to treatment. In series where resections have been performed, the rate of persistent viable tumor was <10%. The likelihood of persistent seminoma seems to correlate with the size of the residual mass. A cut point of 3 cm has been proposed.

In most cases, a residual mass after treatment of seminoma with radiation or systemic chemotherapy does not indicate persistent disease. Rather, it tends to be a manifestation of the dense desmoplastic reaction that this tumor has to treatment. In series where resections have been performed, the rate of persistent viable tumor was <10%. The likelihood of persistent seminoma seems to correlate with the size of the residual mass. A cut point of 3 cm has been proposed.

For residual masses <3 cm in greatest dimension, observation is recommended.

For residual masses <3 cm in greatest dimension, observation is recommended.

For residual masses >3cm, a PET scan should be performed at least 6 weeks from completion of induction chemotherapy or radiation. If negative, observation is recommended. If positive, treatment options include salvage chemotherapy (standard or high dose) or postchemotherapy (PC)-RPLND (Retroperitoneal lymph node dissection) in select cases where disease appears easily resectable as judged by an experienced urologic oncologist.

For residual masses >3cm, a PET scan should be performed at least 6 weeks from completion of induction chemotherapy or radiation. If negative, observation is recommended. If positive, treatment options include salvage chemotherapy (standard or high dose) or postchemotherapy (PC)-RPLND (Retroperitoneal lymph node dissection) in select cases where disease appears easily resectable as judged by an experienced urologic oncologist.

Nonseminoma

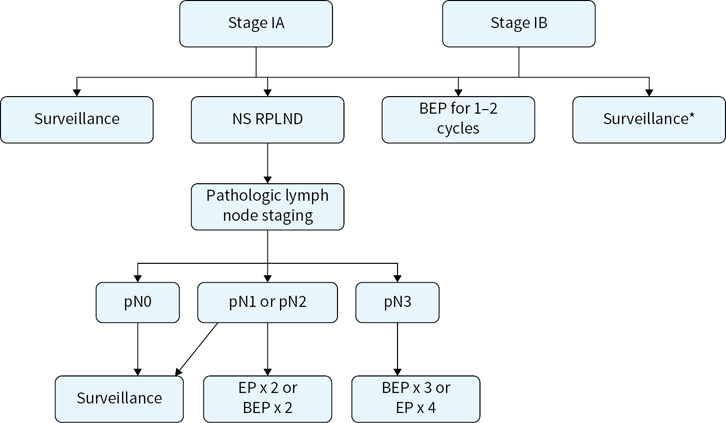

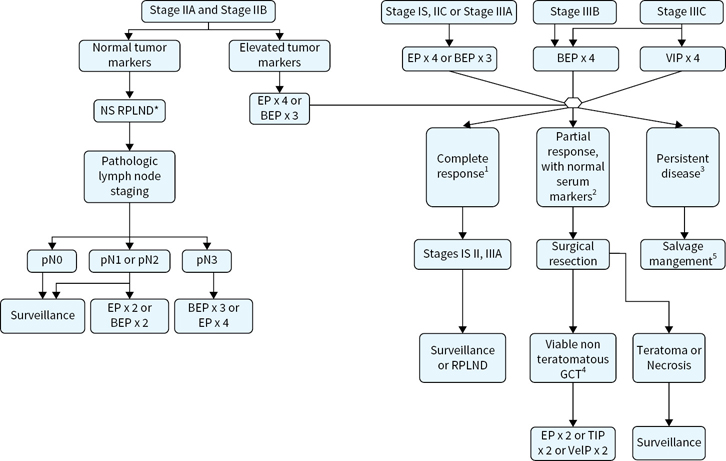

Adjuvant treatment options for stages I, II, and III nonseminoma are outlined in Figures 16.2 and 16.3.

FIGURE 16.2 Adjuvant treatment options for stage I nonseminoma. RPLN, never sparing retroperitoneal lymph node dissection; BEP, bleomycin, etoposide, and cisplatin; EP, etoposide and cisplatin.

FIGURE 16.3 Adjuvant treatment options for stage II and III nonseminoma.

Stage I NSGCT (including pure testicular seminomas with elevated levels of serum AFP) has a 99% to 100% survival regardless of postorchiectomy management option. Overall chance of recurrence/occult disease is approximately 25% to 30%. Risk factors for recurrence/occult disease increases with lymphovascular invasion (LVI) and/or embryonal predominance (>40% of primary tumor). Patients that have LVI and/or embryonal predominance have a >50% chance of recurrence. Those with neither risk factor have an approximately 15% chance of recurrence.

Stage I NSGCT (including pure testicular seminomas with elevated levels of serum AFP) has a 99% to 100% survival regardless of postorchiectomy management option. Overall chance of recurrence/occult disease is approximately 25% to 30%. Risk factors for recurrence/occult disease increases with lymphovascular invasion (LVI) and/or embryonal predominance (>40% of primary tumor). Patients that have LVI and/or embryonal predominance have a >50% chance of recurrence. Those with neither risk factor have an approximately 15% chance of recurrence.

Management options include 1) surveillance, 2) primary RPLND, and 3) systemic chemotherapy.

Management options include 1) surveillance, 2) primary RPLND, and 3) systemic chemotherapy.

Surveillance has become the preferred option for patients without the risk factors listed above. Surveillance is a reasonable option for patients with risk factors for recurrence given the fact that while primary RPLND and adjuvant chemotherapy can improve RFS, they have no effect on cancer-specific survival in this population.

Surveillance has become the preferred option for patients without the risk factors listed above. Surveillance is a reasonable option for patients with risk factors for recurrence given the fact that while primary RPLND and adjuvant chemotherapy can improve RFS, they have no effect on cancer-specific survival in this population.

RPLND was traditionally the preferred approach given that most small volume regional lymph node metastases remain curable with RPLND alone. Some experts continue to advocate for primary RPLND in CS IB patients. This surgery is utilized based on the predictable lymphatic spread from the testicles to the retroperitoneum and the fact that regionally metastatic testicular cancer remains largely curable with surgery alone. Generally, the main advantage/goal of primary RPLND is avoidance of chemotherapy. In the absence of adjuvant post-RPLND chemotherapy, patients with pN0 disease have a 10% chance of recurrence (usually pulmonary), those with pN1-2 disease have a 30% to 50% chance of recurrence. Two cycles of cisplatin-based chemotherapy (BEP or EP) virtually eliminate chance of recurrence in patients with pN1-2 disease at primary RPLND. However, adjuvant chemotherapy after primary RPLND has no effect on cancer-specific survival, which should approach 100%. Adjuvant chemotherapy is an option, but is generally not recommended for pN1 disease. Utilization of adjuvant chemotherapy for pN2 disease varies from center to center. Patients found to have pN3 disease at primary RPLND should have full induction chemotherapy (BEPx3 or EPx4), although this situation is vanishingly rare with sensitivity of preoperative CT for retroperitoneal metastases.

RPLND was traditionally the preferred approach given that most small volume regional lymph node metastases remain curable with RPLND alone. Some experts continue to advocate for primary RPLND in CS IB patients. This surgery is utilized based on the predictable lymphatic spread from the testicles to the retroperitoneum and the fact that regionally metastatic testicular cancer remains largely curable with surgery alone. Generally, the main advantage/goal of primary RPLND is avoidance of chemotherapy. In the absence of adjuvant post-RPLND chemotherapy, patients with pN0 disease have a 10% chance of recurrence (usually pulmonary), those with pN1-2 disease have a 30% to 50% chance of recurrence. Two cycles of cisplatin-based chemotherapy (BEP or EP) virtually eliminate chance of recurrence in patients with pN1-2 disease at primary RPLND. However, adjuvant chemotherapy after primary RPLND has no effect on cancer-specific survival, which should approach 100%. Adjuvant chemotherapy is an option, but is generally not recommended for pN1 disease. Utilization of adjuvant chemotherapy for pN2 disease varies from center to center. Patients found to have pN3 disease at primary RPLND should have full induction chemotherapy (BEPx3 or EPx4), although this situation is vanishingly rare with sensitivity of preoperative CT for retroperitoneal metastases.

Adjuvant chemotherapy: BEPx1 or BEPx2 has been recommended by some experts for CS I patients with LVI or embryonal predominance given the 50% chance of disease recurrence. Proponents of this approach cite the fact that surgeons who can properly perform an RPLND are not available at all centers and that treatment in the adjuvant setting avoids three to four cycle induction with cisplatin-based chemotherapy in patient’s destined to recur on surveillance. Opponents to such risk-adapted utilization of adjuvant chemotherapy cite the 99% to 100% CSS regardless of approach and propose that avoiding chemotherapy entirely in 50% of patients who are not destined to recur may be more beneficial than avoiding one to two additional cycles of chemotherapy in the 50% of patients destined to recur on surveillance.

Adjuvant chemotherapy: BEPx1 or BEPx2 has been recommended by some experts for CS I patients with LVI or embryonal predominance given the 50% chance of disease recurrence. Proponents of this approach cite the fact that surgeons who can properly perform an RPLND are not available at all centers and that treatment in the adjuvant setting avoids three to four cycle induction with cisplatin-based chemotherapy in patient’s destined to recur on surveillance. Opponents to such risk-adapted utilization of adjuvant chemotherapy cite the 99% to 100% CSS regardless of approach and propose that avoiding chemotherapy entirely in 50% of patients who are not destined to recur may be more beneficial than avoiding one to two additional cycles of chemotherapy in the 50% of patients destined to recur on surveillance.

Several factors must be considered before choosing active surveillance. These include the patient’s level of anxiety, compliance, and access to a facility with experienced physicians, radiologists, and CT scanners to detect recurrence. Interestingly, sequelae of treatment, rather than fear of recurrence have been demonstrated to have a negative impact on quality of life in GCT tumor patients. Additionally, there are no reliable predictors of patient compliance.

Several factors must be considered before choosing active surveillance. These include the patient’s level of anxiety, compliance, and access to a facility with experienced physicians, radiologists, and CT scanners to detect recurrence. Interestingly, sequelae of treatment, rather than fear of recurrence have been demonstrated to have a negative impact on quality of life in GCT tumor patients. Additionally, there are no reliable predictors of patient compliance.

Stage IS

Patients with Stage IS disease have elevated postorchiectomy serum tumor markers but no radiographically measurable metastatic disease outside of the testicle.

Patients with Stage IS disease have elevated postorchiectomy serum tumor markers but no radiographically measurable metastatic disease outside of the testicle.

Management is full induction chemotherapy per IGCCCG risk group.

Management is full induction chemotherapy per IGCCCG risk group.

RPLND should not be performed due to unacceptably high relapse rate outside of the retroperitoneum.

RPLND should not be performed due to unacceptably high relapse rate outside of the retroperitoneum.

Management options include primary RPLND or induction cisplatin-based chemotherapy per IGCCCG risk group.

Management options include primary RPLND or induction cisplatin-based chemotherapy per IGCCCG risk group.

Stage IIA–B disease with normal tumor markers and lymph node mass ≤3 cm in greatest dimension may be treated with RPLND or full induction chemotherapy after orchiectomy. Both therapeutic approaches are associated with an approximately 65% chance of complete clinical remission to single modality therapy. Patients with pN1 disease at RPLND for stage CS II disease have an approximately 30% chance of relapse while those with pN2 disease have an approximately 50% chance of relapse. However, 99% to 100% of patients will be cured regardless of whether they receive chemotherapy in the adjuvant setting or if it is reserved for relapse. Interestingly, 20% of clinical stage II patients are found to pathologically negative nodes at primary RPLND.

Stage IIA–B disease with normal tumor markers and lymph node mass ≤3 cm in greatest dimension may be treated with RPLND or full induction chemotherapy after orchiectomy. Both therapeutic approaches are associated with an approximately 65% chance of complete clinical remission to single modality therapy. Patients with pN1 disease at RPLND for stage CS II disease have an approximately 30% chance of relapse while those with pN2 disease have an approximately 50% chance of relapse. However, 99% to 100% of patients will be cured regardless of whether they receive chemotherapy in the adjuvant setting or if it is reserved for relapse. Interestingly, 20% of clinical stage II patients are found to pathologically negative nodes at primary RPLND.

Patients with stage II NSGCT and elevated serum tumor markers or stage IIB/C tumors and nodal disease >3 cm should receive induction cisplatin-based chemotherapy per IGCCCG risk category. Those with a residual postchemotherapy mass of >1 cm should undergo consolidative RPLND.

Patients with stage II NSGCT and elevated serum tumor markers or stage IIB/C tumors and nodal disease >3 cm should receive induction cisplatin-based chemotherapy per IGCCCG risk category. Those with a residual postchemotherapy mass of >1 cm should undergo consolidative RPLND.

The majority of stage III NSGCT remain curable and should be treated per IGCCCG risk group.

The majority of stage III NSGCT remain curable and should be treated per IGCCCG risk group.

Management of Postchemotherapy Masses in NSGCT:

Patients with residual postchemotherapy masses >1 cm in greatest dimension should undergo full bilateral template PC-RPLND with resection of all residual masses. Tumorectomy alone should be discouraged. Utilization of modified unilateral template PC-RPLND in highly selected patients remains controversial.

Patients with residual postchemotherapy masses >1 cm in greatest dimension should undergo full bilateral template PC-RPLND with resection of all residual masses. Tumorectomy alone should be discouraged. Utilization of modified unilateral template PC-RPLND in highly selected patients remains controversial.

Management of patients with complete clinical response (no residual masses >1 cm in greatest dimension) to induction chemotherapy is somewhat controversial. Although most experts agree that observation of these patients is safe citing a 97% 15-year CSS in one large study, some experts advocate for consolidative PC-RPLND in all patients who had a retroperitoneal mass prior to chemotherapy.

Management of patients with complete clinical response (no residual masses >1 cm in greatest dimension) to induction chemotherapy is somewhat controversial. Although most experts agree that observation of these patients is safe citing a 97% 15-year CSS in one large study, some experts advocate for consolidative PC-RPLND in all patients who had a retroperitoneal mass prior to chemotherapy.

Patients with brain metastases at diagnosis should receive an IGCCCG Poor Risk chemotherapy regimen (BEPx4 in most patients). While multimodality treatment is often necessary, treatment should be individualized based primarily on response to chemotherapy, but also on the location and surgical resectability of residual lesions as determined by neurosurgery. Utilization of stereotactic radiation therapy has been described, but the specific role remains to be defined. While whole brain radiotherapy has been used extensively in the past, the survival benefit of this modality has not been clear and it can be associated with significant long-term neurologic sequelae.

Patients with brain metastases at diagnosis should receive an IGCCCG Poor Risk chemotherapy regimen (BEPx4 in most patients). While multimodality treatment is often necessary, treatment should be individualized based primarily on response to chemotherapy, but also on the location and surgical resectability of residual lesions as determined by neurosurgery. Utilization of stereotactic radiation therapy has been described, but the specific role remains to be defined. While whole brain radiotherapy has been used extensively in the past, the survival benefit of this modality has not been clear and it can be associated with significant long-term neurologic sequelae.

In general histology of residual masses are fibrosis 40% to 45%, teratoma in 40% to 45%, and viable nonteratomatous GCT 10% to 15% of the time.

In general histology of residual masses are fibrosis 40% to 45%, teratoma in 40% to 45%, and viable nonteratomatous GCT 10% to 15% of the time.

Patients found to have fibrosis or teratoma without viable GCT at PC-RPLND demonstrate a >95% 5-year CSS. Those with viable GCT have a 60% to 70% 5-year CSS.

Patients found to have fibrosis or teratoma without viable GCT at PC-RPLND demonstrate a >95% 5-year CSS. Those with viable GCT have a 60% to 70% 5-year CSS.

Adjuvant EPx2 can be delivered to minimize chance of relapse in patients with viable nonteratomatous GCT. However, it may not provide any benefit in patients with complete resection of all gross disease, viable malignancy involving <10% of the specimen, and history IGCCCG good risk disease at presentation as patients with these favorable risk factors demonstrate a 90% 5-year RFS.

Adjuvant EPx2 can be delivered to minimize chance of relapse in patients with viable nonteratomatous GCT. However, it may not provide any benefit in patients with complete resection of all gross disease, viable malignancy involving <10% of the specimen, and history IGCCCG good risk disease at presentation as patients with these favorable risk factors demonstrate a 90% 5-year RFS.

Chemotherapy Regimens

Commonly used chemotherapy regimens (Table 16.4) include BEP and EP. VIP and VeIP are used less often.

TABLE 16.4 Commonly Used Chemotherapeutic Agents and Regimens

Agent | Dose | Schedule |

BEP | Bleomycin, 30 units IV weekly on days 1, 8, and 15 (can also be administered on days 2, 9, and 16) | 2 to 4 cycles administered at 21-d intervals |

| Etoposide, 100 mg/m2 IV daily × 5 d |

|

| Platinol (cisplatin), 20 mg/m2 IV daily × 5 d |

|

EP | Etoposide, 100 mg/m2 IV daily × 5 d Platinol (cisplatin), 20 mg/m2 IV daily × 5 d | 4 cycles administered at 21-d intervals |

VIPa | VePesid (etoposide), 75 mg/m2 IV daily × 5 d | 4 cycles administered at 21-d intervals |

| Ifosfamide, 1.2 g/m2 IV daily × 5 d |

|

| Platinol (cisplatin), 20 mg/m2 IV daily × 5 d |

|

| Mesna, 400 mg IV bolus prior to first ifosfamide dose, then 1.2 g/m2 IV infused continuously daily for 5 d |

|

VeIPb | Velban (vinblastine), 0.11 mg/kg on days 1 and 2 | 3 to 4 cycles administered at 21-d intervals |

| Ifosfamide, 1.2 g/m2 IV daily × 5 d |

|

| Platinol (cisplatin), 20 mg/m2 IV daily × 5 d |

|

| Mesna, 400 mg IV bolus prior to first ifosfamide dose, then 1.2 g/m2 IV infused continuously daily for 5 d |

|

TIPb | Taxol (paclitaxel), 175 mg/m2 IV on day 1 | 4 cycles administered at 21-d intervals |

| Ifosfamide, 1 g/m2 daily × 5 d |

|

| Platinol (cisplatin), 20 mg/m2 daily × 5 d |

|

| Mesna, 400 mg IV bolus prior to first ifosfamide dose, then 1.2 g/m2 IV infused continuously daily for 5 d |

|

a May be used in patients with contraindications to bleomycin.

b Generally reserved for tumors that recur after prior chemotherapy.

d, days; IV, intravenous.

Follow-Up

Appropriate surveillance of patients with testicular cancer is essential and should be determined by the tumor’s histology, stage, and treatment (Tables 16.5 and 16.6).

Table 16.5Surveillance Schedule for Seminoma

Year | H&P, Markers (interval in months) | ABD/Pelvic CT (interval in months) | CXR |

Stages I (active surveillance) | |||

1 | 3–6 | 3, 6, 12 | As clinically indicated |

2–3 | 6–12 | 6–12 | |

4–5+ | 12 | 12–24 | |

Stages IA, IB, IS (post radiation)a | |||

1–2 | 6–12 | 12 | As clinically indicated |

3–10 | 12 | 12 (up to year 3) | |

Stages IIA, nonbulky IIB (post radiation or chemotherapy) | |||

1 | 3 | 3, 6–12 | 6 |

2–5 | 6 | 12 (at 4 yrs as clinically indicated) | 6 upto year two |

6–10 | 12 | ||

Stages IIB, IIC, III (post radiation or chemotherapy) | |||

1 | 2 | At 3 to 6 months, then as clinical indicated | 2 |

2 | 3 | 3 | |

3–4 | 6 | *PET as clinical indicated | Annual |

H&P, history and physical; CXR, chest x-ray; ABD, abdomen; CT, computed tomography.

Adapted from National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines. There is considerable interinstitutional variation in the standard of follow-up care, with little evidence that different schedules lead to different outcomes.

a Surveillance schedule for stages IA and IB (postchemotherapy) is similar.

Table 16.6Surveillance Schedule for Nonseminoma

Year | H&P, Markers (interval in months) | ABD/Pelvic CT (interval in months) | CXR |

Stages I (active surveillance) | |||

1 | 2 | 4–6 | At 4 and 12 |

2 | 3 | 6–12 | 12 |

3 | 4–6 | 12 | 12 |

4 | 6 | 12 | |

5 | 12 | 12 | |

Stages IB (active surveillance) | |||

1 | 2 | 4 | 2 |

2 | 2 | 4–6 | 3 |

3 | 4–6 | 6 | 4–6 |

4 | 4 | 12 | 6 |

5 | 12 | 12 | |

Stages IB treated with 1–2 cycles of adjuvant BEP chemotheraphy | |||

1 | 3 | 12 | 6–12 |

2 | 3 | 12 | 12 |

3–4 | 6 | ||

5 | 12 | ||

Stages II–III nonseminoma that has shown a complete response to chemotherapy, with or without post-chemotherapy RPLND | |||

1 | 2 | 6 | 6 |

2 | 3 | 6 | 6 |

3-4 | 6 | 12 | |

5 | 6 | 12 | |

Stage IIA–B nonseminoma, after primary RPLND and treatment with adjuvant chemotherapy | |||

1 | 6 | After RPLND | 6 |

2 | 6 | As clinically indicated | 12 |

3-5 | 4-6 ( annually after year 5) | 12 | |

Stage IIA–B nonseminoma, after primary RPLND and not treated with adjuvant chemotherapy | |||

1 | 2 | 3–4 | 2–4 |

2 | 3 | As clinically indicated | 3–6 |

3 | 4 | 12 | |

4 | 6 | 12 | |

5 | 12 | 12 | |

H&P, history and physical; CXR, chest x-ray; ABD, abdomen; CT, computed tomography.

Adapted from National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines. There is considerable interinstitutional variation in the standard of follow-up care, with little evidence that different schedules lead to different outcomes.

Salvage therapy is usually reserved for disease that has not had a durable response to primary chemotherapy with platinum-based regimen. Such patients may also be considered for a clinical trial especially if they have poor prognostic features.

Salvage therapy is usually reserved for disease that has not had a durable response to primary chemotherapy with platinum-based regimen. Such patients may also be considered for a clinical trial especially if they have poor prognostic features.

Conventional dose regimens incorporate ifosfamide and cisplatin with either vinblastine (VeIP) or paclitaxel (TIP).

Conventional dose regimens incorporate ifosfamide and cisplatin with either vinblastine (VeIP) or paclitaxel (TIP).

High-dose chemotherapy with autologous bone marrow or peripheral stem cell has demonstrated superior oncologic outcomes to standard-dose salvage therapy particularly when used as second- line treatment. Thus, it has replaced standard dose treatment in a significant number of patients—particularly with cisplatin-refractory or cisplatin-resistant disease.

High-dose chemotherapy with autologous bone marrow or peripheral stem cell has demonstrated superior oncologic outcomes to standard-dose salvage therapy particularly when used as second- line treatment. Thus, it has replaced standard dose treatment in a significant number of patients—particularly with cisplatin-refractory or cisplatin-resistant disease.

Agents currently under investigation include gemcitabine, paclitaxel, epirubicin, and oxaliplatin.

Agents currently under investigation include gemcitabine, paclitaxel, epirubicin, and oxaliplatin.

High-Dose Chemotherapy with Autologous Hematopoietic Stem Cell Rescue

The benefit of high-dose chemotherapy with hematopoietic stem cell rescue (HDT) as first-line salvage therapy has been shown in nonrandomized trials but not in randomized phase III studies (Table 16.7).

The benefit of high-dose chemotherapy with hematopoietic stem cell rescue (HDT) as first-line salvage therapy has been shown in nonrandomized trials but not in randomized phase III studies (Table 16.7).

In a large retrospective study, 5-year survival was 53% with HDT as the first salvage therapy.

In a large retrospective study, 5-year survival was 53% with HDT as the first salvage therapy.

Cisplatin refractory germ cell tumors are less likely to have durable response to HDT as compared with tumors that are not refractory to cisplatin.

Cisplatin refractory germ cell tumors are less likely to have durable response to HDT as compared with tumors that are not refractory to cisplatin.

HDT should be considered in patients with germ cell tumors that are refractory to primary chemotherapy or those that failed first-line conventional salvage chemotherapy.

HDT should be considered in patients with germ cell tumors that are refractory to primary chemotherapy or those that failed first-line conventional salvage chemotherapy.

TABLE 16.7 Commonly Used High-Dose Regimens

Agent/Dose | Schedule |

IU regimen | |

Carboplatin 700 mg/m2 IV on days 1, 2, and 3 | 2 cycles given at 14-d interval. Autologous peripheral stem cell infusion on day 6 of each cycle |

Etoposide 750 mg/m2 IV on days 1, 2, and 3 | |

MSKCC regimen | |

Paclitaxel 200 mg/m2 over 24 h on day 1 | 2 cycles given at 14-d interval. Leukapheresis on days 11–13 |

Ifosfamide 2,000 mg/m2 over 4 h daily on days 2–4 with mesna | |

Followed by | |

Carboplatin AUC 7-–8 IV daily on days 1–3 | 3 cycles given at 14-d to 21-d interval. Autologous peripheral stem cell infusion on day 5 of each cycle |

Etoposide 400 mg/m2 IV daily on days 1–3 |

|

IU, Indiana University; MSKCC, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center.

Defined as recurrent GCT >24 months after complete remission to primary therapy.

Defined as recurrent GCT >24 months after complete remission to primary therapy.

Relatively poor prognosis with reported 5-year CSS of 60% to 70% in most series.

Relatively poor prognosis with reported 5-year CSS of 60% to 70% in most series.

Tends to be chemorefractory in patients with prior receipt of cisplatin-based chemotherapy. Thus, initially management should be surgical resection in patients with disease is deemed resectable. Chemotherapy can be utilized to cytoreduce unresectable masses prior to consolidative resection where possible.

Tends to be chemorefractory in patients with prior receipt of cisplatin-based chemotherapy. Thus, initially management should be surgical resection in patients with disease is deemed resectable. Chemotherapy can be utilized to cytoreduce unresectable masses prior to consolidative resection where possible.

Most common histologies are yolk sac tumor and teratoma

Most common histologies are yolk sac tumor and teratoma

AFP is often elevated (reflecting high prevalence of yolk sac tumor).

AFP is often elevated (reflecting high prevalence of yolk sac tumor).

Disproportionally high rate of GCT with somatic-type malignancy (i.e., sarcoma, primitive neuroectodermal tumor, adenocarcinoma).

Disproportionally high rate of GCT with somatic-type malignancy (i.e., sarcoma, primitive neuroectodermal tumor, adenocarcinoma).

Extragonadal Germ Cell Tumors:

Germ cell tumors can arise anywhere along the path of migration of the primordial germ cells from the pineal gland, down through the midline to the gonads. The most common locations of extragonadal GCTs are the anterior mediastinum and retroperitoneum. It should be noted that up to 70% of primary retroperitoneal GCTs are thought to represent the metastatic spread of a burned out testicular germ cell tumor.

Germ cell tumors can arise anywhere along the path of migration of the primordial germ cells from the pineal gland, down through the midline to the gonads. The most common locations of extragonadal GCTs are the anterior mediastinum and retroperitoneum. It should be noted that up to 70% of primary retroperitoneal GCTs are thought to represent the metastatic spread of a burned out testicular germ cell tumor.

Primary mediastinal GCTs should be distinguished from benign or malignant tumors. About 80% of mediastinal germ cell tumors are benign.

Primary mediastinal GCTs should be distinguished from benign or malignant tumors. About 80% of mediastinal germ cell tumors are benign.

While the prognosis of seminoma is not thought to be affected by site of disease, primary mediastinal NSGCT carries a distinctly poorer prognosis than testicular primaries. These tumors are often refractory to cisplatin-based chemotherapy, particularly in the salvage setting. In fact, the futility of high dose chemotherapy in most of these patients has led some experts to recommend against its utilization in this setting given its toxicity.

While the prognosis of seminoma is not thought to be affected by site of disease, primary mediastinal NSGCT carries a distinctly poorer prognosis than testicular primaries. These tumors are often refractory to cisplatin-based chemotherapy, particularly in the salvage setting. In fact, the futility of high dose chemotherapy in most of these patients has led some experts to recommend against its utilization in this setting given its toxicity.

Therapy-Related Toxicity

Overall complication rates have been reported to range from 10% to 20% with major complication rates of <10%.

Overall complication rates have been reported to range from 10% to 20% with major complication rates of <10%.

Complications are more common with PC-RPLND than primary RPLND.

Complications are more common with PC-RPLND than primary RPLND.

Mortality rate for primary RPLND is 0% and <1% for PC-RPLND.

Mortality rate for primary RPLND is 0% and <1% for PC-RPLND.

Most common complications include wound infections and pulmonary complications, which occur in <5% of patients.

Most common complications include wound infections and pulmonary complications, which occur in <5% of patients.

Chylous ascites, symptomatic lymphocele, or postoperative small bowel obstruction occurs in <3% of patients.

Chylous ascites, symptomatic lymphocele, or postoperative small bowel obstruction occurs in <3% of patients.

Utilization of modified unilateral templates as well as sparing of the L1-4 postganglionic sympathetic fibers preserves postoperative antegrade ejaculation in nearly all patients where these techniques can be employed. However, nerve-sparing and/or modified template dissections are not always possible or appropriate in the postchemotherapy setting.

Utilization of modified unilateral templates as well as sparing of the L1-4 postganglionic sympathetic fibers preserves postoperative antegrade ejaculation in nearly all patients where these techniques can be employed. However, nerve-sparing and/or modified template dissections are not always possible or appropriate in the postchemotherapy setting.

Although 70% to 80% of patients treated with chemotherapy may recover sperm production within 5 years, sperm banking should be discussed with all patients desiring to father children after therapy.

At diagnosis, approximately 45% of patients have oligospermia, sperm abnormalities, or altered follicular-stimulating hormone levels due in part to the association of testicular cancer with conditions such as cryptorchidism or testicular atrophy.

At diagnosis, approximately 45% of patients have oligospermia, sperm abnormalities, or altered follicular-stimulating hormone levels due in part to the association of testicular cancer with conditions such as cryptorchidism or testicular atrophy.

Orchiectomy may further impair spermatogenesis.

Orchiectomy may further impair spermatogenesis.

Almost all patients become azospermic or oligospermic during chemotherapy.

Almost all patients become azospermic or oligospermic during chemotherapy.

Children of treated patients do not appear to have an increased risk of congenital abnormalities.

Children of treated patients do not appear to have an increased risk of congenital abnormalities.

Bleomycin may cause pneumonitis and pulmonary fibrosis, which is now rare, but may be fatal in up to 50% of patients.

Bleomycin may cause pneumonitis and pulmonary fibrosis, which is now rare, but may be fatal in up to 50% of patients.

More frequently, asymptomatic decreases in pulmonary function resolve after completion of bleomycin therapy.

More frequently, asymptomatic decreases in pulmonary function resolve after completion of bleomycin therapy.

Bleomycin should be discontinued if early signs of pulmonary toxicity develop or if there is a decline of ≥40% in diffusing capacity of lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO).

Bleomycin should be discontinued if early signs of pulmonary toxicity develop or if there is a decline of ≥40% in diffusing capacity of lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO).

Routine pulmonary function tests are rarely indicated and should be reserved for patients with signs and symptoms of pulmonary toxicity (e.g., dry rales or pulmonary lag on physical examination or dyspnea on exertion).

Routine pulmonary function tests are rarely indicated and should be reserved for patients with signs and symptoms of pulmonary toxicity (e.g., dry rales or pulmonary lag on physical examination or dyspnea on exertion).

Corticosteroids may be used to reduce lung inflammation if pulmonary toxicity occurs.

Corticosteroids may be used to reduce lung inflammation if pulmonary toxicity occurs.

Smokers treated with bleomycin should be particularly discouraged from tobacco use and alternatives to bleomycin-containing regimens should be considered (i.e., EPx4 in good risk patients and VIPx4 in intermediate and poor risk patients).

Smokers treated with bleomycin should be particularly discouraged from tobacco use and alternatives to bleomycin-containing regimens should be considered (i.e., EPx4 in good risk patients and VIPx4 in intermediate and poor risk patients).

Retrospective studies have suggested that low fraction of inspired oxygen and conservative intravascular volume management during PC-RPLND may reduce the incidence of postoperative bleomycin-induced pulmonary toxicity.

Retrospective studies have suggested that low fraction of inspired oxygen and conservative intravascular volume management during PC-RPLND may reduce the incidence of postoperative bleomycin-induced pulmonary toxicity.

Cisplatin-based chemotherapy may result in decreased glomerular filtration rate, which can be permanent in 20% to 30% of patients.

Cisplatin-based chemotherapy may result in decreased glomerular filtration rate, which can be permanent in 20% to 30% of patients.

Hypokalemia and hypomagnesemia are also frequent manifestations of altered kidney function in these patients.

Hypokalemia and hypomagnesemia are also frequent manifestations of altered kidney function in these patients.

Cisplatin-based chemotherapy may result in persistent peripheral neuropathy in 20% to 30% of patients.

Cisplatin-based chemotherapy may result in persistent peripheral neuropathy in 20% to 30% of patients.

Cisplatin-induced neuropathy is sensory and distal. Peripheral digital dysesthesias and paresthesias are the most common manifestations.

Cisplatin-induced neuropathy is sensory and distal. Peripheral digital dysesthesias and paresthesias are the most common manifestations.

Polymorphism in the glutathione S-transferase gene may increase the susceptibility to cisplatin-induced neurotoxicity.

Polymorphism in the glutathione S-transferase gene may increase the susceptibility to cisplatin-induced neurotoxicity.

Ototoxicity in the form of tinnitus or high-frequency hearing loss, usually outside the frequency of spoken language, may be seen in up to 20% of the patients treated with cisplatin-based regimen. The risk increases with increasing number of treatment cycles.

Ototoxicity in the form of tinnitus or high-frequency hearing loss, usually outside the frequency of spoken language, may be seen in up to 20% of the patients treated with cisplatin-based regimen. The risk increases with increasing number of treatment cycles.

Bleomycin, cisplatin, and radiation alone or in combination can increase the risk of cardiovascular disease.

Bleomycin, cisplatin, and radiation alone or in combination can increase the risk of cardiovascular disease.

Angina, myocardial infarction, and sudden cardiac death are increased by up to twofold.

Angina, myocardial infarction, and sudden cardiac death are increased by up to twofold.

The risk of hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and insulin resistance is increased in patients with testicular cancer treated with chemotherapy.

The risk of hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and insulin resistance is increased in patients with testicular cancer treated with chemotherapy.

Patients are also at increased risk of thromboembolism and Raynaud phenomenon.

Patients are also at increased risk of thromboembolism and Raynaud phenomenon.

Secondary malignancies are associated with the use of cisplatin, etoposide, and radiation. Patients treated for testicular cancer with these agents reportedly have a 1.7-fold increase in their risk of developing a secondary malignancy.

Secondary malignancies are associated with the use of cisplatin, etoposide, and radiation. Patients treated for testicular cancer with these agents reportedly have a 1.7-fold increase in their risk of developing a secondary malignancy.

The increased risk of second malignancy may persist for up to 35 years after the completion of chemotherapy or radiotherapy for testicular carcinoma.

The increased risk of second malignancy may persist for up to 35 years after the completion of chemotherapy or radiotherapy for testicular carcinoma.

Alkylating agents such as cisplatin may lead to a myelodysplastic syndrome within 5 to 7 years that can eventually progress to leukemia. Topoisomerase inhibitors such as etoposide may cause secondary leukemias within 3 years.

Alkylating agents such as cisplatin may lead to a myelodysplastic syndrome within 5 to 7 years that can eventually progress to leukemia. Topoisomerase inhibitors such as etoposide may cause secondary leukemias within 3 years.

There is an increased incidence of solid tumors in previous radiation fields, including the bladder, stomach, pancreas, and kidney.

There is an increased incidence of solid tumors in previous radiation fields, including the bladder, stomach, pancreas, and kidney.

Suggested Readings

1.Albers P, Albrecht W, Algaba F, et al. Guidelines on Testicular Cancer: 2015 Update. Eur Urol. 2015;68:1054.

2.Beard CJ, Gupta S, Motzer RJ, et al. Follow-up management of patients with testicular cancer: a multidisciplinary consensus-based approach. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2015;13:811–822.

3.CR Nichols, B Roth, P Albers, et al. Active surveillance is the preferred approach to clinical stage I testicular cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3490–3493.

4.De Santis M, Becherer A, Bokemeyer C, et al. 2-18fluoro-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography is a reliable predictor for viable tumor in postchemotherapy seminoma: an update of the prospective multicentric SEMPET trial. J Clin Oncol. 2004 Mar;22(6):1034–1039.

5.de Wit R, Fizazi K. Controversies in the management of clinical stage I testis cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5482–5492.

6.Ehrlich, Yaron et al. Advances in the treatment of testicular cancer. Transl Androl Urol. 2015;4(3):381–390.

7.Einhorn LH, Williams SD, Chamness A, et al. High-dose chemotherapy and stem-cell rescue for metastatic germ-cell tumors. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:340–348.

8.Farmakis D, Pectasides M, Pectasides D. Recent advances in conventional-dose salvage chemotherapy in patients with cisplatin-resistant or refractory testicular germ cell tumors. Eur Urol. 2005;48:400–407.