Sarah M. Temkin and Charles A. Kunos

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Uterine cervix cancer represents the fourth most common cancer in women, and the seventh overall, representing an estimated 527,624 new cancer cases from around the world in 2012.

Uterine cervix cancer represents the fourth most common cancer in women, and the seventh overall, representing an estimated 527,624 new cancer cases from around the world in 2012.

There were an estimated 265,672 deaths from uterine cervix cancer worldwide in 2012, making it the fourth most common lethal cancer in women and 10th overall. Uterine cervix cancer accounts for 8% of all female cancer-related deaths.

There were an estimated 265,672 deaths from uterine cervix cancer worldwide in 2012, making it the fourth most common lethal cancer in women and 10th overall. Uterine cervix cancer accounts for 8% of all female cancer-related deaths.

Among American women, uterine cervix cancer is the third most common cancer of the genital system, with an estimated 12,990 new cases and 4,120 deaths estimated in 2016.

Among American women, uterine cervix cancer is the third most common cancer of the genital system, with an estimated 12,990 new cases and 4,120 deaths estimated in 2016.

Papanicolaou (Pap) smear screening has lowered the incidence and mortality of invasive uterine cervix cancer by almost 75% over the past 50 years; however, nearly 85% of cases occur in less developed regions where Pap screening may not be available.

Papanicolaou (Pap) smear screening has lowered the incidence and mortality of invasive uterine cervix cancer by almost 75% over the past 50 years; however, nearly 85% of cases occur in less developed regions where Pap screening may not be available.

Uterine cervix cancer incidence among American women continues to decline but remains disproportionately high among subpopulation (American blacks, Hispanics of any race, Asian/Pacific Islander Americans, American Indian/Alaskan Natives).

Uterine cervix cancer incidence among American women continues to decline but remains disproportionately high among subpopulation (American blacks, Hispanics of any race, Asian/Pacific Islander Americans, American Indian/Alaskan Natives).

In developed socioeconomic regions, the cumulative risk of uterine cervix cancer by age 75 years is 0.9% and the mortality risk is 0.3%; in less developed regions, those same risks are 1.9% and 1.1%, respectively.

In developed socioeconomic regions, the cumulative risk of uterine cervix cancer by age 75 years is 0.9% and the mortality risk is 0.3%; in less developed regions, those same risks are 1.9% and 1.1%, respectively.

RISK FACTORS

Human Papillomavirus

Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection is the most important factor in disease progression to uterine cervix cancer. Up to 90% of uterine cervix cancers retain HPV DNA in the malignant cell phenotype.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection is the most important factor in disease progression to uterine cervix cancer. Up to 90% of uterine cervix cancers retain HPV DNA in the malignant cell phenotype.

Over 170 HPV subtypes are known, and about 40 subtypes infect the genital system.

Over 170 HPV subtypes are known, and about 40 subtypes infect the genital system.

HPV virus subtypes associated with high risk for uterine cervix cancer include types 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, and 59. A 9-valent HPV vaccine includes HPV 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58 virus-like particles.

HPV virus subtypes associated with high risk for uterine cervix cancer include types 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, and 59. A 9-valent HPV vaccine includes HPV 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58 virus-like particles.

HPV types 16 and 18 account for 70% of uterine cervix cancer incidence.

HPV types 16 and 18 account for 70% of uterine cervix cancer incidence.

In the United States, up to 50% of sexually active young women will be HPV (+) within 36 months of sexual activity; however, most women clear the infection within 8 to 24 months.

In the United States, up to 50% of sexually active young women will be HPV (+) within 36 months of sexual activity; however, most women clear the infection within 8 to 24 months.

HPV prevalence in regions with a high incidence of uterine cervix cancer is 10% to 20%, while in regions with a lower incidence of uterine cervix cancer, HPV prevalence is 5% to 10%.

HPV prevalence in regions with a high incidence of uterine cervix cancer is 10% to 20%, while in regions with a lower incidence of uterine cervix cancer, HPV prevalence is 5% to 10%.

The HPV oncogenic phenotype involves HPV E6 protein, which inactivates p53, and HPV E7 protein, which inactivates pRb. Resulting loss of a G1/S cell cycle checkpoint leads to unregulated DNA replication, favorable for viral DNA duplication and implicated in malignant transformation of uterine cervix cells.

The HPV oncogenic phenotype involves HPV E6 protein, which inactivates p53, and HPV E7 protein, which inactivates pRb. Resulting loss of a G1/S cell cycle checkpoint leads to unregulated DNA replication, favorable for viral DNA duplication and implicated in malignant transformation of uterine cervix cells.

It is not known whether HPV subtyping of invasive uterine cervix cancer impacts clinical outcome or cancer care provider management. For women with high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSIL), the presence of high-risk HPV subtypes elevates the hazard for invasive uterine cervix cancer.

It is not known whether HPV subtyping of invasive uterine cervix cancer impacts clinical outcome or cancer care provider management. For women with high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSIL), the presence of high-risk HPV subtypes elevates the hazard for invasive uterine cervix cancer.

Demographic, Personal, or Sexual Risk Factors

Risk of invasive uterine cervix cancer is largely influenced by HPV exposure, vaccination, and screening as well as immune response to HPV infection.

Risk of invasive uterine cervix cancer is largely influenced by HPV exposure, vaccination, and screening as well as immune response to HPV infection.

Demographic risk factors include race (elevated among Hispanics of any race, American blacks, and American Indian/Alaskan Natives), low socioeconomic status (reflective of poverty and poor education status), and immigration from high-HPV prevalence or low-screening worldwide regions.

Demographic risk factors include race (elevated among Hispanics of any race, American blacks, and American Indian/Alaskan Natives), low socioeconomic status (reflective of poverty and poor education status), and immigration from high-HPV prevalence or low-screening worldwide regions.

Personal risk factors include early onset of coitus (relative risk [RR] is 2-fold for younger than 18 years compared to 21 years or older), multiple sex partners (RR is 3-fold with six or more partners compared to one partner), and a history of sexually transmitted infections.

Personal risk factors include early onset of coitus (relative risk [RR] is 2-fold for younger than 18 years compared to 21 years or older), multiple sex partners (RR is 3-fold with six or more partners compared to one partner), and a history of sexually transmitted infections.

Among males with multiple sex partners (a known risk factor for HPV infection), penile circumcision appears to reduce the risk of uterine cervix cancer in their female partners.

Among males with multiple sex partners (a known risk factor for HPV infection), penile circumcision appears to reduce the risk of uterine cervix cancer in their female partners.

A “current smoker” status raises the RR of squamous cell uterine cervix cancer 4-fold and has been shown to accelerate progression of dysplasia to invasive carcinoma 2-fold.

A “current smoker” status raises the RR of squamous cell uterine cervix cancer 4-fold and has been shown to accelerate progression of dysplasia to invasive carcinoma 2-fold.

Additional risk factors include multiparity (RR = 3.8), use of oral contraceptives for more than 5 years (RR of 1.90), and immunosuppression.

Additional risk factors include multiparity (RR = 3.8), use of oral contraceptives for more than 5 years (RR of 1.90), and immunosuppression.

Renal transplantation (RR = 5.7) and HIV infection (RR = 2.5) increase the risk of uterine cervix cancer—a uterine cervix cancer diagnosis identifies an indicator condition for acquired immunodeficiency syndrome [AIDS] in human immunodeficiency virus [HIV]-positive women according to 1993 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention criteria.

Renal transplantation (RR = 5.7) and HIV infection (RR = 2.5) increase the risk of uterine cervix cancer—a uterine cervix cancer diagnosis identifies an indicator condition for acquired immunodeficiency syndrome [AIDS] in human immunodeficiency virus [HIV]-positive women according to 1993 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention criteria.

SCREENING

Joint national guidelines provide the following consensus screening recommendations:

Joint national guidelines provide the following consensus screening recommendations:

•Uterine cervix cancer screening of women in the general population should begin no sooner than age 21.

•Women aged 21 to 29 should be screened with cervical cytology alone every 3 years.

•In women aged 30 to 65, cotesting with cervical cytology and HPV testing every 5 years is preferred. Continued screening with cervical cytology every 3 years is acceptable.

•Screening should end at age 65 in women with negative prior screening and no history of HSIL. Likewise, it should end in women who have had a (total) hysterectomy with removal of the cervix and no prior history of HSIL.

Cervical cytology should be described using the 2001 Bethesda System detailing specimen adequacy and interpretation.

Cervical cytology should be described using the 2001 Bethesda System detailing specimen adequacy and interpretation.

Interpretation is divided into nonmalignant findings and epithelial cell abnormalities including squamous and glandular abnormalities.

Interpretation is divided into nonmalignant findings and epithelial cell abnormalities including squamous and glandular abnormalities.

Adenocarcinoma incidence has been increasing over past three decades because Pap screening is often inadequate for detecting endocervical lesions; however, HPV screening and vaccine may decrease both squamous and adenocarcinoma rates.

Adenocarcinoma incidence has been increasing over past three decades because Pap screening is often inadequate for detecting endocervical lesions; however, HPV screening and vaccine may decrease both squamous and adenocarcinoma rates.

PRECURSOR LESIONS

Mild, moderate, and severe cervical dysplasias are categorized as low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (LSIL, formerly CIN 1) or HSIL (formerly CIN 2 or 3).

Mild, moderate, and severe cervical dysplasias are categorized as low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (LSIL, formerly CIN 1) or HSIL (formerly CIN 2 or 3).

Mild-to-moderate dysplasias are more likely to regress than progress. Nevertheless, the rate of progression of mild dysplasia to severe dysplasia is 1% per year; the rate of progression of moderate dysplasia to severe dysplasia is 16% within 2 years and 25% within 5 years.

Mild-to-moderate dysplasias are more likely to regress than progress. Nevertheless, the rate of progression of mild dysplasia to severe dysplasia is 1% per year; the rate of progression of moderate dysplasia to severe dysplasia is 16% within 2 years and 25% within 5 years.

Untreated carcinoma in situ has a 30% probability of progression to invasive cancer over a 30-year observation period.

Untreated carcinoma in situ has a 30% probability of progression to invasive cancer over a 30-year observation period.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

HSIL and early uterine cervix cancer are often asymptomatic.

HSIL and early uterine cervix cancer are often asymptomatic.

In symptomatic patients, abnormal vaginal bleeding (i.e., postcoital, intermenstrual, or menorrhagia) is the most common symptom and may lead to anemia-related fatigue.

In symptomatic patients, abnormal vaginal bleeding (i.e., postcoital, intermenstrual, or menorrhagia) is the most common symptom and may lead to anemia-related fatigue.

Vaginal discharge (serosanguinous or yellowish, sometimes foul smelling) may represent a more advanced lesion.

Vaginal discharge (serosanguinous or yellowish, sometimes foul smelling) may represent a more advanced lesion.

Pain in the lumbosacral or gluteal area may suggest hydronephrosis caused by tumor, or tumor extension to lumbar nerve roots.

Pain in the lumbosacral or gluteal area may suggest hydronephrosis caused by tumor, or tumor extension to lumbar nerve roots.

Bladder or rectum symptoms (hematuria, rectal bleeding, etc.) may indicate organ invasion.

Bladder or rectum symptoms (hematuria, rectal bleeding, etc.) may indicate organ invasion.

Persistent, unilateral, or bilateral leg edema may indicate lymphatic and venous blockage caused by extensive pelvic sidewall nodal or tissue disease.

Persistent, unilateral, or bilateral leg edema may indicate lymphatic and venous blockage caused by extensive pelvic sidewall nodal or tissue disease.

Leg pain, edema, and hydronephrosis are characteristic of advanced-stage disease (IIIB).

Leg pain, edema, and hydronephrosis are characteristic of advanced-stage disease (IIIB).

DIAGNOSTIC WORKUP

History and physical examination should include bimanual pelvic and rectovaginal septum examinations. These are usually normal with stage IA disease (microscopic invasion only).

History and physical examination should include bimanual pelvic and rectovaginal septum examinations. These are usually normal with stage IA disease (microscopic invasion only).

The most frequent examination abnormalities include visible cervical lesions or abnormalities on bimanual pelvic examination.

The most frequent examination abnormalities include visible cervical lesions or abnormalities on bimanual pelvic examination.

About 15% of adenocarcinomas have no visible lesion because the carcinoma is within the endocervical canal.

About 15% of adenocarcinomas have no visible lesion because the carcinoma is within the endocervical canal.

Standard Diagnostic Procedures

Cervical cytology for routine screening and in the absence of a gross lesion

Cervical cytology for routine screening and in the absence of a gross lesion

Cervical biopsy of any gross lesion (perhaps by colposcopy)

Cervical biopsy of any gross lesion (perhaps by colposcopy)

Conization for subclinical tumor, or after negative biopsy when malignancy is suspected

Conization for subclinical tumor, or after negative biopsy when malignancy is suspected

Conization for microinvasive cancer to assist in primary treatment triage

Conization for microinvasive cancer to assist in primary treatment triage

Endocervical curettage for suspected endocervical lesions

Endocervical curettage for suspected endocervical lesions

Cystoscopy and proctoscopy for symptoms worrisome for bladder or rectal tumor extension

Cystoscopy and proctoscopy for symptoms worrisome for bladder or rectal tumor extension

Radiologic Studies

Because of the limits of low-resource regions, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) clinical staging limits radiographic imaging for staging purposes to chest x-ray, intravenous pyelography (IVP), and barium enema.

Because of the limits of low-resource regions, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) clinical staging limits radiographic imaging for staging purposes to chest x-ray, intravenous pyelography (IVP), and barium enema.

If available for treatment planning purposes, computed tomography (CT), positron emission tomography (PET), PET/CT, or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are informative.

If available for treatment planning purposes, computed tomography (CT), positron emission tomography (PET), PET/CT, or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are informative.

MRI is the best for delineating soft-tissue or parametrial tissue invasion.

MRI is the best for delineating soft-tissue or parametrial tissue invasion.

CT or PET/CT is useful to evaluate initial pelvic or para-aortic lymph node involvement.

CT or PET/CT is useful to evaluate initial pelvic or para-aortic lymph node involvement.

Laboratory Studies

Complete blood count to evaluate for anemia

Complete blood count to evaluate for anemia

Blood chemistries to evaluate for renal function

Blood chemistries to evaluate for renal function

Liver function tests to evaluate synthetic and metabolic factors

Liver function tests to evaluate synthetic and metabolic factors

HISTOLOGY

Cervical carcinoma often originates at a squamous-columnar cell junction of the uterine cervix, by name, the transformation zone.

Cervical carcinoma often originates at a squamous-columnar cell junction of the uterine cervix, by name, the transformation zone.

Seventy-five percent to 80% of uterine cervix cancers are of squamous cell histology; the remaining 20% to 25% are mostly adenocarcinomas or adenosquamous carcinomas.

Seventy-five percent to 80% of uterine cervix cancers are of squamous cell histology; the remaining 20% to 25% are mostly adenocarcinomas or adenosquamous carcinomas.

STAGING

Because the global burden of uterine cervix cancer occurs in low-resource regions where abilities to surgically stage women with disease may be limited, uterine cervix cancer is clinically staged. The 2010 FIGO definitions and staging system are accepted uniformly. This system has been endorsed by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC).

Because the global burden of uterine cervix cancer occurs in low-resource regions where abilities to surgically stage women with disease may be limited, uterine cervix cancer is clinically staged. The 2010 FIGO definitions and staging system are accepted uniformly. This system has been endorsed by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC).

Laparoscopy, lymphangiography, CT, CT/PET, and/or MRI have all been used for primary treatment planning.

Laparoscopy, lymphangiography, CT, CT/PET, and/or MRI have all been used for primary treatment planning.

PROGNOSTIC FACTORS

Major prognostic factors include clinical stage, lymph node involvement, tumor volume (or >4 cm in unidimensional measurement), depth of cervical stroma invasion, lymphovascular space invasion (LVSI), and to a lesser extent histologic type and grade.

Major prognostic factors include clinical stage, lymph node involvement, tumor volume (or >4 cm in unidimensional measurement), depth of cervical stroma invasion, lymphovascular space invasion (LVSI), and to a lesser extent histologic type and grade.

Stage is the most important prognostic factor, followed by lymph node involvement.

Stage is the most important prognostic factor, followed by lymph node involvement.

Five-year survival based on the extent of tumor at diagnosis:

Five-year survival based on the extent of tumor at diagnosis:

•Uterine cervix confined: 92%

•Pelvis-contained: 56%

•Extrapelvic metastatic disease: 16.5%

•Unstaged at diagnosis: 60%

MODE OF SPREAD

Disease spread is orderly, occurring first along lymphovascular planes to involve parametrial tissues. Disease may extend to the vaginal mucosa or the uterine corpus. Disease spread to adjacent organs is typically by direct extension.

Disease spread is orderly, occurring first along lymphovascular planes to involve parametrial tissues. Disease may extend to the vaginal mucosa or the uterine corpus. Disease spread to adjacent organs is typically by direct extension.

Ovarian involvement by direct extension of uterine cervix cancer is rare (0.5% of squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs), 1.7% adenocarcinomas).

Ovarian involvement by direct extension of uterine cervix cancer is rare (0.5% of squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs), 1.7% adenocarcinomas).

Lymphatic dissemination most commonly involves pelvic lymph nodes first and then para-aortic lymph nodes. Skip para-aortic nodal lesions occur.

Lymphatic dissemination most commonly involves pelvic lymph nodes first and then para-aortic lymph nodes. Skip para-aortic nodal lesions occur.

Vascular spread is late in the disease process, and metastases occur in lung, liver, and bone.

Vascular spread is late in the disease process, and metastases occur in lung, liver, and bone.

Risk of pelvic lymph node metastases increases with increasing depth of tumor invasion, tumor bulk, and presence of LVSI.

Risk of pelvic lymph node metastases increases with increasing depth of tumor invasion, tumor bulk, and presence of LVSI.

TREATMENT

High-Grade Intraepithelial Lesions/Carcinoma in Situ

AJCC includes stage 0 for in situ disease (Tis), while FIGO no longer includes stage 0 (Tis).

AJCC includes stage 0 for in situ disease (Tis), while FIGO no longer includes stage 0 (Tis).

Noninvasive lesions can be treated with electrosurgical excision, cryotherapy, laser excision or ablation, surgical conization, or other surgical procedures.

Noninvasive lesions can be treated with electrosurgical excision, cryotherapy, laser excision or ablation, surgical conization, or other surgical procedures.

A one-step diagnostic and therapeutic option is the loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP), which allows excision of the entire transformation zone of the cervix with a low-voltage diathermy loop.

A one-step diagnostic and therapeutic option is the loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP), which allows excision of the entire transformation zone of the cervix with a low-voltage diathermy loop.

A cold-knife conization (CKC) excises the transformation zone with a scalpel, avoiding cautery artifact on the surgical margins. In the majority of situations, LEEP may be an acceptable alternative to CKC because it is a quick, outpatient procedure requiring only local anesthesia.

A cold-knife conization (CKC) excises the transformation zone with a scalpel, avoiding cautery artifact on the surgical margins. In the majority of situations, LEEP may be an acceptable alternative to CKC because it is a quick, outpatient procedure requiring only local anesthesia.

When margin status will dictate the need for, and type of, additional therapy, as in cases of adenocarcinoma in situ or microinvasive SCC, a CKC is preferred.

When margin status will dictate the need for, and type of, additional therapy, as in cases of adenocarcinoma in situ or microinvasive SCC, a CKC is preferred.

Extrafascial (i.e., simple or total) hysterectomy is preferred for management of adenocarcinoma in situ in women who have completed childbearing. If preservation of fertility is desired, conization with negative margins followed by surveillance is reasonable.

Extrafascial (i.e., simple or total) hysterectomy is preferred for management of adenocarcinoma in situ in women who have completed childbearing. If preservation of fertility is desired, conization with negative margins followed by surveillance is reasonable.

Invasive Uterine Cervix Cancer

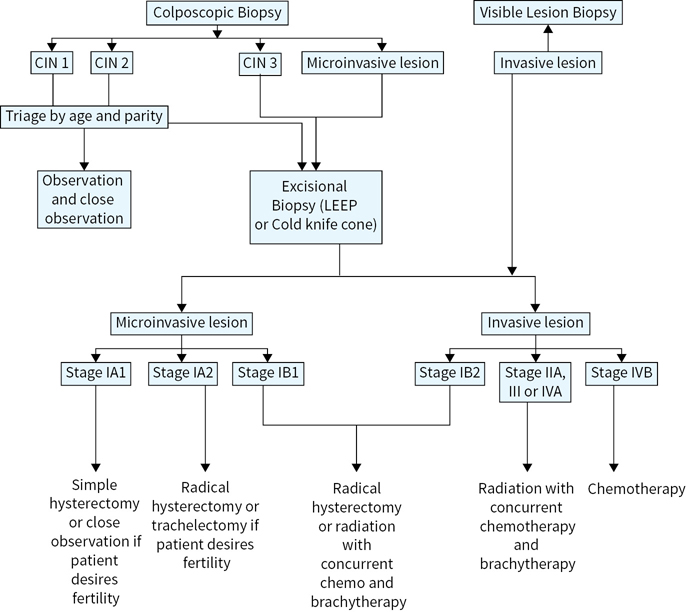

Treatment for each clinical stage varies depending on the size of the tumor (Figure 19.1). Smaller tumors may be treated surgically or with radiation. Larger tumors are usually only treated with radiochemotherapy (or, radiation alone in special circumstances).

Treatment for each clinical stage varies depending on the size of the tumor (Figure 19.1). Smaller tumors may be treated surgically or with radiation. Larger tumors are usually only treated with radiochemotherapy (or, radiation alone in special circumstances).

Results from five randomized phase III trials demonstrated an overall survival (OS) advantage for cisplatin-based chemotherapy co-administered with radiotherapy when compared to radiation-only therapy. These trials demonstrated a 30% to 50% risk reduction overall for death in women with FIGO stages IB2 to IVA tumors, or in women with FIGO stages I to IIA tumors with poor prognostic factors (i.e., pelvic lymph node involvement, parametrial disease, and positive surgical margins).

Results from five randomized phase III trials demonstrated an overall survival (OS) advantage for cisplatin-based chemotherapy co-administered with radiotherapy when compared to radiation-only therapy. These trials demonstrated a 30% to 50% risk reduction overall for death in women with FIGO stages IB2 to IVA tumors, or in women with FIGO stages I to IIA tumors with poor prognostic factors (i.e., pelvic lymph node involvement, parametrial disease, and positive surgical margins).

Based on these data, the National Cancer Institute issued a clinical alert informing cancer care providers that a strong consideration should be given to adding cisplatin-based chemotherapy to radiotherapy in the treatment of invasive uterine cervix cancer.

Based on these data, the National Cancer Institute issued a clinical alert informing cancer care providers that a strong consideration should be given to adding cisplatin-based chemotherapy to radiotherapy in the treatment of invasive uterine cervix cancer.

The most common regimen for concurrent radiochemotherapy is once-weekly cisplatin, 40 mg/m2 IV (maximum 70 mg) for six weekly cycles during daily radiation therapy.

The most common regimen for concurrent radiochemotherapy is once-weekly cisplatin, 40 mg/m2 IV (maximum 70 mg) for six weekly cycles during daily radiation therapy.

Alternatively, cisplatin with 5-FU given every 3 to 4 weeks during radiation is acceptable.

Alternatively, cisplatin with 5-FU given every 3 to 4 weeks during radiation is acceptable.

Stage IA1

Prior to initial therapy, the most important factors confounding cancer care include (1) a woman’s fertility desires, (2) medical operability, and (3) presence of LVSI at biopsy.

Prior to initial therapy, the most important factors confounding cancer care include (1) a woman’s fertility desires, (2) medical operability, and (3) presence of LVSI at biopsy.

For women with no LVSI and negative histopathological margins on their LEEP or CKC specimen, and who have completed childbearing, a simple hysterectomy is indicated.

For women with no LVSI and negative histopathological margins on their LEEP or CKC specimen, and who have completed childbearing, a simple hysterectomy is indicated.

For those with LVSI or positive margins, a modified radical hysterectomy with pelvic lymph node dissection is indicated.

For those with LVSI or positive margins, a modified radical hysterectomy with pelvic lymph node dissection is indicated.

For those who wish to preserve fertility, a conization with negative margins, followed by observation is adequate therapy. However, if margins are positive, options include radical trachelectomy or repeat cone biopsy.

For those who wish to preserve fertility, a conization with negative margins, followed by observation is adequate therapy. However, if margins are positive, options include radical trachelectomy or repeat cone biopsy.

Para-aortic lymph node dissection is reserved for patients with known or suspected nodal disease.

Para-aortic lymph node dissection is reserved for patients with known or suspected nodal disease.

Stages IA2, IB1, IIA1 (Early-Stage Disease)

General options for early-stage disease include the following:

General options for early-stage disease include the following:

•Fertility sparing—radical trachelectomy and pelvic lymph node dissection with (or without) para-aortic lymph node dissection

•Modified radical hysterectomy and pelvic lymph node dissection with para-aortic lymph node dissection for known or suspected nodal disease

•Definitive radiochemotherapy

All options are equally effective but differ in associated morbidity and complications.

All options are equally effective but differ in associated morbidity and complications.

For early-stage uterine cervix cancers, primary surgery is often recommended.

For early-stage uterine cervix cancers, primary surgery is often recommended.

Optimal therapy selection depends on patient’s age and childbearing plans, disease stage, current comorbidities, and the presence of histologic characteristics associated with the increased risk of recurrence.

Optimal therapy selection depends on patient’s age and childbearing plans, disease stage, current comorbidities, and the presence of histologic characteristics associated with the increased risk of recurrence.

Stage IB2 or IIA2 (Bulky Disease)

General options for bulky disease include the following:

General options for bulky disease include the following:

•Definitive radiochemotherapy (whole pelvic radiation and brachytherapy), or

•Radical hysterectomy plus pelvic lymph node dissection with para-aortic lymph node dissection for known or suspected nodal disease.

Radiologic imaging (including PET/CT) is recommended for assessing bulky disease.

Radiologic imaging (including PET/CT) is recommended for assessing bulky disease.

Radiochemotherapy has been shown to improve patient survival.

Radiochemotherapy has been shown to improve patient survival.

Adjuvant hysterectomy after primary radiochemotherapy appears to improve pelvic control, but not OS and has increased morbidity. Adjuvant surgery (i.e., after pelvic radiotherapy) is not routinely performed but may be considered in patients with residual tumor confined to the cervix or in patients with suboptimal brachytherapy because of vaginal anatomy.

Adjuvant hysterectomy after primary radiochemotherapy appears to improve pelvic control, but not OS and has increased morbidity. Adjuvant surgery (i.e., after pelvic radiotherapy) is not routinely performed but may be considered in patients with residual tumor confined to the cervix or in patients with suboptimal brachytherapy because of vaginal anatomy.

Laparoscopic and robotic approaches are associated with shortened recovery time, decreased hospital stay, and less blood loss. They are used routinely in many institutions with promising early outcome data.

Laparoscopic and robotic approaches are associated with shortened recovery time, decreased hospital stay, and less blood loss. They are used routinely in many institutions with promising early outcome data.

Radical trachelectomy is a fertility-preserving surgery, which may be an option for small-volume, early-stage disease (IA1–IB1).

Radical trachelectomy is a fertility-preserving surgery, which may be an option for small-volume, early-stage disease (IA1–IB1).

Para-aortic lymph node sampling may be indicated in patients with positive pelvic nodes, clinically enlarged nodes, or patients with large-volume disease.

Para-aortic lymph node sampling may be indicated in patients with positive pelvic nodes, clinically enlarged nodes, or patients with large-volume disease.

Indications for Adjuvant Therapy

High risk for recurrent disease:

High risk for recurrent disease:

•Positive or close margins

•Positive lymph nodes

•Positive parametrial involvement

Intermediate risk for recurrent disease:

Intermediate risk for recurrent disease:

•LVSI

•Deep stromal invasion (greater than one-third)

•Large tumor size (greater than 4 cm)

Women who undergo a modified radical hysterectomy should receive adjuvant radiochemotherapy treatment in the presence of risk factors (listed above).

Women who undergo a modified radical hysterectomy should receive adjuvant radiochemotherapy treatment in the presence of risk factors (listed above).

•For women with intermediate risk factors, a randomized trial demonstrated that adjuvant RT improved progression-free survival (PFS), with a trend toward improved OS.

•For women with high risk factors, a randomized trial demonstrated that adjuvant radiochemotherapy was associated with an improved PFS and OS.

If definitive radiotherapy is chosen over radical hysterectomy, concurrent cisplatin-based chemotherapy should be administered.

If definitive radiotherapy is chosen over radical hysterectomy, concurrent cisplatin-based chemotherapy should be administered.

Stages IIB, III, IV

Patients with stage IIB to IVA disease (commonly referred to as locally advanced-stage disease) should be treated with tumor volume–directed radiotherapy and concurrent cisplatin-based chemotherapy.

Patients with stage IIB to IVA disease (commonly referred to as locally advanced-stage disease) should be treated with tumor volume–directed radiotherapy and concurrent cisplatin-based chemotherapy.

Radiologic imaging (PET/CT) and potentially surgical staging (i.e., extraperitoneal or laparoscopic lymph node dissection) are recommended to assess lymph node involvement and serves as a guide to radiation therapy portal design.

Radiologic imaging (PET/CT) and potentially surgical staging (i.e., extraperitoneal or laparoscopic lymph node dissection) are recommended to assess lymph node involvement and serves as a guide to radiation therapy portal design.

Patients with stage IVA disease (bowel or bladder mucosa invasion), who are poor candidates for radiochemotherapy (i.e., acute or chronic pelvic inflammatory disease, coexistent pelvic mass), may be candidates for pelvic exenteration surgery.

Patients with stage IVA disease (bowel or bladder mucosa invasion), who are poor candidates for radiochemotherapy (i.e., acute or chronic pelvic inflammatory disease, coexistent pelvic mass), may be candidates for pelvic exenteration surgery.

Patients who have distant metastasis (IVB disease) should receive systemic and/or biologic agent chemotherapy with (most often) or without (less often) pelvis-directed radiation therapy.

Patients who have distant metastasis (IVB disease) should receive systemic and/or biologic agent chemotherapy with (most often) or without (less often) pelvis-directed radiation therapy.

For definitive treatment, pelvic external beam radiation therapy (EBRT) with intracavitary brachytherapy is used routinely.

For definitive treatment, pelvic external beam radiation therapy (EBRT) with intracavitary brachytherapy is used routinely.

High (>8000 cGy) radiation dose may be delivered to central primary tumors through use of EBRT and intracavitary brachytherapy. EBRT alone often cannot achieve these doses due to intervening normal tissues (e.g., small bowel, large bowel, and bladder).

High (>8000 cGy) radiation dose may be delivered to central primary tumors through use of EBRT and intracavitary brachytherapy. EBRT alone often cannot achieve these doses due to intervening normal tissues (e.g., small bowel, large bowel, and bladder).

In select cases of very early disease (stage IA2) brachytherapy alone may be an option.

In select cases of very early disease (stage IA2) brachytherapy alone may be an option.

Pelvic inflammatory disease, inflammatory bowel disease, and pelvic kidney are relative contraindications to conventional pelvic radiation, but may not impede intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT).

Pelvic inflammatory disease, inflammatory bowel disease, and pelvic kidney are relative contraindications to conventional pelvic radiation, but may not impede intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT).

CT-based treatment planning is considered standard-of-care for EBRT.

CT-based treatment planning is considered standard-of-care for EBRT.

EBRT should encompass gross disease (vaginal margin 3 cm from tumor), parametrial tissues, uterosacral ligaments, and presacral, external/internal iliac, and obturator lymph nodes. For patients at high risk for lymph nodes involvement, the radiation field should also cover common iliac lymph nodes. If common iliac or para-aortic lymph node involvement is clinically suspected, extended-field radiation that raises the superior radiation portal boundary up at least to the level of renal vessels is recommended.

EBRT should encompass gross disease (vaginal margin 3 cm from tumor), parametrial tissues, uterosacral ligaments, and presacral, external/internal iliac, and obturator lymph nodes. For patients at high risk for lymph nodes involvement, the radiation field should also cover common iliac lymph nodes. If common iliac or para-aortic lymph node involvement is clinically suspected, extended-field radiation that raises the superior radiation portal boundary up at least to the level of renal vessels is recommended.

Both high-dose brachytherapy (isotope 192Iridium; rate 200 to 300 cGy per hour) and low-dose brachytherapy (isotope 137Cesium; rate 40 to 70 cGy per hour) are used. Either brachytherapy source or technique are acceptable.

Both high-dose brachytherapy (isotope 192Iridium; rate 200 to 300 cGy per hour) and low-dose brachytherapy (isotope 137Cesium; rate 40 to 70 cGy per hour) are used. Either brachytherapy source or technique are acceptable.

Determining maximum effective dose to the primary tumor, as well as to the bladder and rectum, is of primary importance. A typical regimen of EBRT is 4000 to 5000 cGy plus 3000 to 4000 cGy point A brachytherapy, for a total dose of 8000 to 9000 cGy to point A.

Determining maximum effective dose to the primary tumor, as well as to the bladder and rectum, is of primary importance. A typical regimen of EBRT is 4000 to 5000 cGy plus 3000 to 4000 cGy point A brachytherapy, for a total dose of 8000 to 9000 cGy to point A.

Point A is located 2 cm cephalad and 2 cm lateral to the cervical OS. Anatomically, it correlates with the boundary between the lateral uterine cervix and the medial edge of parametrial tissue, an anatomic point where the ureter and uterine artery cross.

Point A is located 2 cm cephalad and 2 cm lateral to the cervical OS. Anatomically, it correlates with the boundary between the lateral uterine cervix and the medial edge of parametrial tissue, an anatomic point where the ureter and uterine artery cross.

A parametrial boost (900 to 1440 Gy) by EBRT may be applied to point B (defined as 5 cm lateral to patient midline and corresponding to the pelvic sidewall lymph nodes).

A parametrial boost (900 to 1440 Gy) by EBRT may be applied to point B (defined as 5 cm lateral to patient midline and corresponding to the pelvic sidewall lymph nodes).

Radiation treatment is equivalent to surgery for stages IB and IIA, with identical 5-year OS and disease-free survival. Expected cure rate is 75% to 80% (85% to 90% in small-volume disease).

Radiation treatment is equivalent to surgery for stages IB and IIA, with identical 5-year OS and disease-free survival. Expected cure rate is 75% to 80% (85% to 90% in small-volume disease).

A study by the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG 79-20) showed a 11% 10-year survival advantage for patients with IB2, IIA, and IIB disease treated with prophylactic para-aortic nodal (extended field RT) and total pelvic irradiation compared to those treated with pelvic irradiation alone.

A study by the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG 79-20) showed a 11% 10-year survival advantage for patients with IB2, IIA, and IIB disease treated with prophylactic para-aortic nodal (extended field RT) and total pelvic irradiation compared to those treated with pelvic irradiation alone.

Multivariate analyses have shown that a total dose of >8500 cGy intracavitary radiation to point A (locally advanced stage only), radiosensitizers like cisplatin, and overall treatment time of <8 weeks are associated with improved pelvic tumor control and survival in women with uterine cervix cancer. Treatment times beyond 8 weeks (56 days) result in an up to 1% decline, per extended treatment day, in recurrence-free survival.

Multivariate analyses have shown that a total dose of >8500 cGy intracavitary radiation to point A (locally advanced stage only), radiosensitizers like cisplatin, and overall treatment time of <8 weeks are associated with improved pelvic tumor control and survival in women with uterine cervix cancer. Treatment times beyond 8 weeks (56 days) result in an up to 1% decline, per extended treatment day, in recurrence-free survival.

No standard chemotherapy regimen has been shown to produce prolonged complete remissions.

No standard chemotherapy regimen has been shown to produce prolonged complete remissions.

Combination platinum-based chemotherapy has demonstrated improved response rates in randomized trials compared to single-agent therapy.

Combination platinum-based chemotherapy has demonstrated improved response rates in randomized trials compared to single-agent therapy.

Cisplatin/paclitaxel demonstrated higher response rate and improved PFS compared to single-agent cisplatin in Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) 169. Preliminary data from a Japanese randomized trial demonstrate equivalency of carboplatin/paclitaxel with cisplatin/paclitaxel.

Cisplatin/paclitaxel demonstrated higher response rate and improved PFS compared to single-agent cisplatin in Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) 169. Preliminary data from a Japanese randomized trial demonstrate equivalency of carboplatin/paclitaxel with cisplatin/paclitaxel.

Cisplatin/topotecan demonstrated superior response rate, PFS, and median survival compared to single-agent cisplatin in GOG 179.

Cisplatin/topotecan demonstrated superior response rate, PFS, and median survival compared to single-agent cisplatin in GOG 179.

A comparison trial of cisplatin/topotecan, cisplatin/gemcitabine, and cisplatin/vinorelbine compared to a control arm of cisplatin/paclitaxel was halted when the experimental arms were not superior to the control. Cisplatin/paclitaxel had the best response rate, 29.1%.

A comparison trial of cisplatin/topotecan, cisplatin/gemcitabine, and cisplatin/vinorelbine compared to a control arm of cisplatin/paclitaxel was halted when the experimental arms were not superior to the control. Cisplatin/paclitaxel had the best response rate, 29.1%.

Based on the above, cisplatin/paclitaxel and carboplatin/paclitaxel are the most commonly used regimens for metastatic and recurrent uterine cervix cancer. Cisplatin/topotecan, cisplatin/gemcitabine, or single-agent therapies are reasonable alternatives.

Based on the above, cisplatin/paclitaxel and carboplatin/paclitaxel are the most commonly used regimens for metastatic and recurrent uterine cervix cancer. Cisplatin/topotecan, cisplatin/gemcitabine, or single-agent therapies are reasonable alternatives.

The most active single agents include

The most active single agents include

•cisplatin (response rate 20% to 30%)

•carboplatin (response rate 15% to 28%)

•ifosfamide (response rate 15% to 33%)

•paclitaxel (response rate 17% to 25%)

Other agents with activity include irinotecan, vinorelbine, gemcitabine, bevacizumab, docetaxel, 5-FU, mitomycin, topotecan, and pemetrexed.

Other agents with activity include irinotecan, vinorelbine, gemcitabine, bevacizumab, docetaxel, 5-FU, mitomycin, topotecan, and pemetrexed.

The benefit of chemotherapy with or without radiation versus best supportive care in this patient population has not yet been established.

The benefit of chemotherapy with or without radiation versus best supportive care in this patient population has not yet been established.

Recent studies have clearly demonstrated the deleterious effect of anemia on patients receiving radiation therapy. Hemoglobin levels <10 g/dL at the time of radiation therapy impede local disease control and survival. Blood transfusions to raise hemoglobin levels above 10 g/dL are recommended.

Recent studies have clearly demonstrated the deleterious effect of anemia on patients receiving radiation therapy. Hemoglobin levels <10 g/dL at the time of radiation therapy impede local disease control and survival. Blood transfusions to raise hemoglobin levels above 10 g/dL are recommended.

Some patients with small-volume disease in para-aortic lymph nodes and controllable pelvic disease can potentially be cured. Removal of grossly involved para-aortic lymph nodes prior to radiotherapy may be therapeutic.

Some patients with small-volume disease in para-aortic lymph nodes and controllable pelvic disease can potentially be cured. Removal of grossly involved para-aortic lymph nodes prior to radiotherapy may be therapeutic.

Toxicity from extended-field radiation exceeds that of pelvic radiation alone, but most commonly is seen in women with prior abdominopelvic surgery.

Toxicity from extended-field radiation exceeds that of pelvic radiation alone, but most commonly is seen in women with prior abdominopelvic surgery.

Different surgical techniques affect the incidence of complications secondary to para-aortic lymph node extended-field radiation. For example, extraperitoneal lymph node sampling leads to fewer radiation-related posttherapy complications than transperitoneal lymph node sampling.

Different surgical techniques affect the incidence of complications secondary to para-aortic lymph node extended-field radiation. For example, extraperitoneal lymph node sampling leads to fewer radiation-related posttherapy complications than transperitoneal lymph node sampling.

IMRT has been shown to reduce sequelae of pelvic and extended-field radiation therapy. Clinical trials evaluating IMRT are underway in this patient population.

IMRT has been shown to reduce sequelae of pelvic and extended-field radiation therapy. Clinical trials evaluating IMRT are underway in this patient population.

Recurrent Disease

A 10% to 20% recurrence rate has been reported in stage IB to IIA women with negative nodal sampling treated by primary surgery or radiation therapy.

A 10% to 20% recurrence rate has been reported in stage IB to IIA women with negative nodal sampling treated by primary surgery or radiation therapy.

Up to 70% of women with stage IIB, III, or IVA disease with or without positive nodal sampling exhibit recurrences.

Up to 70% of women with stage IIB, III, or IVA disease with or without positive nodal sampling exhibit recurrences.

Intrapelvic recurrences are symptomatic, with 80% to 90% detected by 2 years posttherapy.

Intrapelvic recurrences are symptomatic, with 80% to 90% detected by 2 years posttherapy.

In the recurrence setting, favorable prognostic factors include central pelvis disease site, disease not fixed to the pelvic sidewall, the posttherapy disease-free interval is 6 months or longer, and the recurrent tumor measures less than 3 cm.

In the recurrence setting, favorable prognostic factors include central pelvis disease site, disease not fixed to the pelvic sidewall, the posttherapy disease-free interval is 6 months or longer, and the recurrent tumor measures less than 3 cm.

More than 90% of women with distant extrapelvic recurrence die of disease within 5 years.

More than 90% of women with distant extrapelvic recurrence die of disease within 5 years.

For stage I-IIA disease, the predominant anatomic site of recurrence is local (vaginal apex) or intrapelvic (pelvic sidewall).

For stage I-IIA disease, the predominant anatomic site of recurrence is local (vaginal apex) or intrapelvic (pelvic sidewall).

Multiple studies have shown that the distribution of recurrence site as

Multiple studies have shown that the distribution of recurrence site as

•Central pelvis (vaginal apex)—22% to 56%

•Regional pelvis (pelvic sidewall)—28% to 37%

•Distant extrapelvic metastasis—15% to 61%

Women with positive lymph nodes at initial diagnosis, particularly para-aortic lymph node involvement, have a higher risk of distant metastases as compared to women with negative lymph nodes.

Women with positive lymph nodes at initial diagnosis, particularly para-aortic lymph node involvement, have a higher risk of distant metastases as compared to women with negative lymph nodes.

No curative therapy is available for metastatic disease. In direct contrast, intrapelvic recurrence can potentially be treated with curative intent.

No curative therapy is available for metastatic disease. In direct contrast, intrapelvic recurrence can potentially be treated with curative intent.

Surgical resection of limited metastatic disease, such as in the lung, may result in prolonged clinical remission.

Surgical resection of limited metastatic disease, such as in the lung, may result in prolonged clinical remission.

For patients with intrapelvic recurrence after radical surgery, cisplatin-based radiochemotherapy has a 40% to 50% durable control rate and long-term survival rate.

For patients with intrapelvic recurrence after radical surgery, cisplatin-based radiochemotherapy has a 40% to 50% durable control rate and long-term survival rate.

Pelvic exenteration (resection of the bladder, rectum, vagina, uterus/cervix) is a preferred treatment for centrally located recurrent disease after primary radiation therapy, with a 32% to 62% 5-year survival in select women. Reconstructive procedures include continent urinary conduit, end-to-end rectosigmoid reanastomosis, and myocutaneous graft for a neovagina.

Pelvic exenteration (resection of the bladder, rectum, vagina, uterus/cervix) is a preferred treatment for centrally located recurrent disease after primary radiation therapy, with a 32% to 62% 5-year survival in select women. Reconstructive procedures include continent urinary conduit, end-to-end rectosigmoid reanastomosis, and myocutaneous graft for a neovagina.

High-dose intraoperative radiation therapy combined with surgical resection is offered by some centers for patients whose tumors extend close to the pelvic sidewalls.

High-dose intraoperative radiation therapy combined with surgical resection is offered by some centers for patients whose tumors extend close to the pelvic sidewalls.

Chemotherapy for distant recurrent disease is palliative, not curative, demonstrating low response rates, short response duration, and low OS rates (see the Palliative Chemotherapy section). Cisplatin is the most active single agent, with a median survival of seven months.

Chemotherapy for distant recurrent disease is palliative, not curative, demonstrating low response rates, short response duration, and low OS rates (see the Palliative Chemotherapy section). Cisplatin is the most active single agent, with a median survival of seven months.

Factors associated with higher likelihood of recurrence to cisplatin-based combination chemotherapy include

Factors associated with higher likelihood of recurrence to cisplatin-based combination chemotherapy include

•American black race

•Performance status 1 or 2

•Disease in the pelvis

•Prior treatment by cisplatin-containing regimen

•Relapse within one year of initial diagnosis

Chemotherapy-naive patients have a higher response rate than those exposed to chemotherapy as part of their initial treatment.

Chemotherapy-naive patients have a higher response rate than those exposed to chemotherapy as part of their initial treatment.

TREATMENT DURING PREGNANCY

Uterine cervix cancer is the most common gynecologic malignancy associated with pregnancy, ranging from 1 in 1,200 to 1 in 2,200 pregnancies.

Uterine cervix cancer is the most common gynecologic malignancy associated with pregnancy, ranging from 1 in 1,200 to 1 in 2,200 pregnancies.

No therapy is warranted for preinvasive lesions; colposcopy, but not endocervical curettage, is recommended to rule out invasive cancer.

No therapy is warranted for preinvasive lesions; colposcopy, but not endocervical curettage, is recommended to rule out invasive cancer.

Conization is reserved for suspicion of invasion or for persistent cytologic evidence of invasive cancer in the absence of colposcopic confirmation. Management of dysplasia is usually postponed until postpartum.

Conization is reserved for suspicion of invasion or for persistent cytologic evidence of invasive cancer in the absence of colposcopic confirmation. Management of dysplasia is usually postponed until postpartum.

Treatment of invasive cancer depends on the tumor stage and the fetus’s gestational age. If cancer is diagnosed before fetal maturity, immediate appropriate cancer therapy for the relevant stage is recommended. However, with close surveillance, delay of therapy to achieve fetal maturity is a reasonable option for patients with stage IA and early IB disease. For more advanced disease, delaying therapy is not recommended unless diagnosis is made in the final trimester. When the fetus reaches acceptable maturity, a cesarean section precedes definitive treatment.

Treatment of invasive cancer depends on the tumor stage and the fetus’s gestational age. If cancer is diagnosed before fetal maturity, immediate appropriate cancer therapy for the relevant stage is recommended. However, with close surveillance, delay of therapy to achieve fetal maturity is a reasonable option for patients with stage IA and early IB disease. For more advanced disease, delaying therapy is not recommended unless diagnosis is made in the final trimester. When the fetus reaches acceptable maturity, a cesarean section precedes definitive treatment.

TREATMENT OF HIV (+) WOMEN

HIV-infected women (or immunocompromised) should undergo uterine cervix cancer screening twice in the first year after diagnosis and then annually.

HIV-infected women (or immunocompromised) should undergo uterine cervix cancer screening twice in the first year after diagnosis and then annually.

Each examination should include a thorough visual inspection of the anus, vulva, vagina, as well as the uterine cervix.

Each examination should include a thorough visual inspection of the anus, vulva, vagina, as well as the uterine cervix.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Centers for Disease Control do not endorse HPV testing in the triage of HIV-infected patients. This conflicts with 2006 American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology Consensus Guidelines, which endorse similar management of patients irrespective of HIV status.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Centers for Disease Control do not endorse HPV testing in the triage of HIV-infected patients. This conflicts with 2006 American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology Consensus Guidelines, which endorse similar management of patients irrespective of HIV status.

Treatment of preinvasive lesions and uterine cervix cancers in HIV (+) patients is the same as in HIV-negative patients, though response to therapy is usually poorer.

Treatment of preinvasive lesions and uterine cervix cancers in HIV (+) patients is the same as in HIV-negative patients, though response to therapy is usually poorer.

Incidence of HSIL is four- to five-times higher in HIV (+) women compared to HIV-negative women with high-risk behaviors.

Incidence of HSIL is four- to five-times higher in HIV (+) women compared to HIV-negative women with high-risk behaviors.

Among HIV-infected women, rates of oncogenic HPV and HSIL increase with diminished CD4 counts and higher circulating HIV RNA levels.

Among HIV-infected women, rates of oncogenic HPV and HSIL increase with diminished CD4 counts and higher circulating HIV RNA levels.

Women with HIV are more likely to have persistent HPV and HSIL than uninfected women.

Women with HIV are more likely to have persistent HPV and HSIL than uninfected women.

Although anti-retroviral therapy has altered the natural history of HIV, its effect on HPV and HPV-associated neoplasia is less clear.

Although anti-retroviral therapy has altered the natural history of HIV, its effect on HPV and HPV-associated neoplasia is less clear.

FOLLOW-UP AFTER PRIMARY THERAPY

Eighty percent to 90% of recurrences occur within 2 years of completing therapy suggesting a role for increased surveillance during this period.

Eighty percent to 90% of recurrences occur within 2 years of completing therapy suggesting a role for increased surveillance during this period.

Follow-up visits, including thorough physical examination, should occur every 3 to 6 months in the first 2 years posttherapy, every 6 to 12 months for the following 3 years then annually to detect any potentially curable recurrences.

Follow-up visits, including thorough physical examination, should occur every 3 to 6 months in the first 2 years posttherapy, every 6 to 12 months for the following 3 years then annually to detect any potentially curable recurrences.

Additionally, patients should have annual cervical or vaginal cytology, though an exception can be made for those that have undergone pelvic radiation.

Additionally, patients should have annual cervical or vaginal cytology, though an exception can be made for those that have undergone pelvic radiation.

There are insufficient data to support the routine use of radiographic imaging; chest x-ray, CT, and PET or PET/CT should only be used if recurrence is suspected.

There are insufficient data to support the routine use of radiographic imaging; chest x-ray, CT, and PET or PET/CT should only be used if recurrence is suspected.

Patients should be counseled about signs and symptoms of recurrence to include persistent abdominal and pelvic pain, leg symptoms such as pain or lymphedema, vaginal bleeding or discharge, urinary symptoms, cough, weight loss, and anorexia.

Patients should be counseled about signs and symptoms of recurrence to include persistent abdominal and pelvic pain, leg symptoms such as pain or lymphedema, vaginal bleeding or discharge, urinary symptoms, cough, weight loss, and anorexia.

PREVENTION

The efficacy of HPV vaccination against HSIL and cancer has been demonstrated in multiple studies since 2002. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend that females aged 9 to 12 years of age be vaccinated by the three (3) dose regimen. Vaccine administrations to “catch up” occur through age 26 in females. The 9-valent HPV vaccine is most commonly administered.

The efficacy of HPV vaccination against HSIL and cancer has been demonstrated in multiple studies since 2002. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend that females aged 9 to 12 years of age be vaccinated by the three (3) dose regimen. Vaccine administrations to “catch up” occur through age 26 in females. The 9-valent HPV vaccine is most commonly administered.

FIGURE 19.1 Overview of the management of preinvasive and invasive lesions of the cervix.

Suggested Readings

1.ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 117. Gynecologic care for women with human immunodeficiency virus. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(6):1492–1509.

2.ACOG Practice Bulletin Number 131. Screening for cervical. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(5):1222–1238.

3.Berrington de Gonzalez A, Green J. Comparison of risk factors for invasive squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma of the cervix: collaborative reanalysis of individual data on 8,097 women with squamous cell carcinoma and 1,374 women with adenocarcinoma from 12 epidemiological studies. Int J Cancer. 2007;120(4):885–891.

4.de Sanjose S, Quint WG, Alemany L, et al. Human papillomavirus genotype attribution in invasive cervical cancer: a retrospective cross-sectional worldwide study. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11(11):1048–1056.

5.Holowaty P, Miller AB, Rohan T, et al. Natural history of dysplasia of the uterine cervix. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91(3):252–258.

6.Kaplan JE, Benson C, Holmes KH, et al. Guidelines for prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in HIV-infected adults and adolescents: recommendations from CDC, the National Institutes of Health, and the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2009;58(RR-4):1–207; quiz CE1–4.

7.Keys HM, Bundy BN, Stehman FB, et al. Cisplatin, radiation, and adjuvant hysterectomy compared with radiation and adjuvant hysterectomy for bulky stage IB cervical carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(15):1154–1161.

8.Keys HM, Bundy BN, Stehman FB, et al. Radiation therapy with and without extrafascial hysterectomy for bulky stage IB cervical carcinoma: a randomized trial of the Gynecologic Oncology Group. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;89(3):343–353.

9.Kitagawa R, Katsumata N, Ando M, et al. A multi-institutional phase II trial of paclitaxel and carboplatin in the treatment of advanced or recurrent cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;125(2):307–311.

10.Kunos CA, Radivoyevitch T, Waggoner S, et al. Radiochemotherapy plus 3-aminopyridine-2-carboxaldehyde thiosemicarbazone (3-AP, NSC #663249) in advanced-stage cervical and vaginal cancers. Gynecol Oncol 2013;130(1):75–80.

11.Long HJ III, Bundy BN, Grendys EC Jr, et al. Randomized phase III trial of cisplatin with or without topotecan in carcinoma of the uterine cervix: a Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(21):4626–4633.

12.Markowitz LE, Dunne EF, Saraiya M, et al. Quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2007;56(RR-2):1–24.

13.McCredie MR, Sharples KJ, Paul C, et al. Natural history of cervical neoplasia and risk of invasive cancer in women with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 3: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9(5):425–434.

14.Moore DH, Blessing JA, McQuellon RP, et al. Phase III study of cisplatin with or without paclitaxel in stage IVB, recurrent, or persistent squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix: a gynecologic oncology group study. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(15): 3113–3119.

15.Morris M, Eifel PJ, Lu J, et al. Pelvic radiation with concurrent chemotherapy compared with pelvic and para-aortic radiation for high-risk cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(15):1137–1143.

16.NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Cervical Cancer. 2012; Version 1.2018. Available at: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/default.aspx. Last accessed November 14, 2017.

17.Peters WA III, Liu PY, Barrett RJ II, et al. Concurrent chemotherapy and pelvic radiation therapy compared with pelvic radiation therapy alone as adjuvant therapy after radical surgery in high-risk early-stage cancer of the cervix. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(8):1606–1613.

18.Rogers L, Siu SS, Luesley D, et al. Radiotherapy and chemoradiation after surgery for early cervical cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;5:CD007583.

19.Rose PG, Bundy BN, Watkins EB, et al. Concurrent cisplatin-based radiotherapy and chemotherapy for locally advanced cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(15):1144–1153.

20.Rotman M, Sedlis A, Piedmonte MR, et al. A phase III randomized trial of postoperative pelvic irradiation in Stage IB cervical carcinoma with poor prognostic features: follow-up of a gynecologic oncology group study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;65(1):169–176.

21.Salani R, Backes FJ, Fung MF, et al. Posttreatment surveillance and diagnosis of recurrence in women with gynecologic malignancies: Society of Gynecologic Oncologists recommendations. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204(6):466–478.

22.Saslow D, Solomon D, Lawson HW, et al. American Cancer Society, American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, and American Society for Clinical Pathology screening guidelines for the prevention and early detection of cervical cancer. Am J Clin Pathol. 2012;137(4):516–542.

23.Tewari KS, Sill MW, Long HJ, et al. Improved survival with bevacizumab in advanced cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(8):734–743.

24.Walboomers JM, Jacobs MV, Manos MM, et al. Human papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical cancer worldwide. J Pathol. 1999;189(1):12–19.

25.Wright TC Jr, Massad LS, Dunton CJ, et al. 2006 consensus guidelines for the management of women with abnormal cervical cancer screening tests. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197(4):346–355.