Upendra P. Hegde and Sanjiv S. Agarwala

INTRODUCTION

The skin is the largest organ of the human body, embryologically derived from the neuroectoderm and the mesoderm, eventually organized into epidermis, dermis, and subcutis.

Cancer of the skin arises from the cell types of structures in all the three layers (Table 22.1).

Direct exposure of the skin to sun’s ultraviolet radiation and a wide variety of environmental carcinogens predisposes to genetic damage and increased risk of cancer. Skin cancers are best divided into melanoma and nonmelanoma.

Table 22.1Cell of Epidermis, Dermis, and Respective Tumor Types

Cells of Epidermis | Tumor-Type/ Incidence | Cells of Dermis | Tumor-Typea |

Melanocytes | Melanoma 5%–7% | Fibroblasts | Benign and malignant fibrous tumor |

Epidermal basal cells | Basal cell carcinoma 60% | Histiocytes | Histiocytic tumor |

Keratinocytes | Squamous cell carcinoma 30% | Mast cells | Mast cell tumor |

Merkel cells | Merkel cell tumor 1%–2% | Vasculature | Angioma, Angiosarcoma, Lymphangioma |

Langerhans cells | Histiocytosis X <1% | Lymphocytes | Non-Hodgkin lymphoma |

Appendage cells | Appendageal tumors <1% | — | — |

a Incidence of tumors in dermis <1% each type.

MELANOMA

Melanoma arises from the melanocyte, a neural crest–derived cell that migrates during embryogenesis predominantly to the basal layer of the epidermal skin and less commonly to the other tissues in the body such as mucosa of the upper aerodigestive and the lower genitourinary tract, the meninges, and the ocular choroid, where melanoma is rarely encountered.

Epidemiology

Melanoma ranks as the 5th and 7th leading type of cancer in US men and women, respectively.

Melanoma ranks as the 5th and 7th leading type of cancer in US men and women, respectively.

Incidence is high in young, middle age, and elderly subjects.

Incidence is high in young, middle age, and elderly subjects.

Estimated lifetime risk of developing invasive melanoma in US whites is about 1 in 33 in males and 1 in 52 in women.

Estimated lifetime risk of developing invasive melanoma in US whites is about 1 in 33 in males and 1 in 52 in women.

In 2017, 87,110 new cases of invasive melanoma are expected to be diagnosed in the US with 9,73010,130 subjects projected to die from it.

In 2017, 87,110 new cases of invasive melanoma are expected to be diagnosed in the US with 9,73010,130 subjects projected to die from it.

The incidence of melanoma is higher in men than women, Northern than Eastern and Central Europeans and more than 10 times greater in whites than in blacks.

The incidence of melanoma is higher in men than women, Northern than Eastern and Central Europeans and more than 10 times greater in whites than in blacks.

Australia has the highest incidence of melanoma in the world, approximately 40 cases compared to 23.6 cases among US whites per 100,000 population per year.

Australia has the highest incidence of melanoma in the world, approximately 40 cases compared to 23.6 cases among US whites per 100,000 population per year.

The rate of rise in melanoma incidence has decreased from 6% a year in the 1970s to 3% a year between 1980 and 2000 and stabilized after that period in younger subjects.

The rate of rise in melanoma incidence has decreased from 6% a year in the 1970s to 3% a year between 1980 and 2000 and stabilized after that period in younger subjects.

In white males over 50 years of age, the incidence continues to climb at the fastest rate.

In white males over 50 years of age, the incidence continues to climb at the fastest rate.

The median age at diagnosis and death from melanoma is 63 and 69 years, respectively.

The median age at diagnosis and death from melanoma is 63 and 69 years, respectively.

The percent of cutaneous melanoma deaths is highest among people aged 75 to 84 years.

The percent of cutaneous melanoma deaths is highest among people aged 75 to 84 years.

Etiology

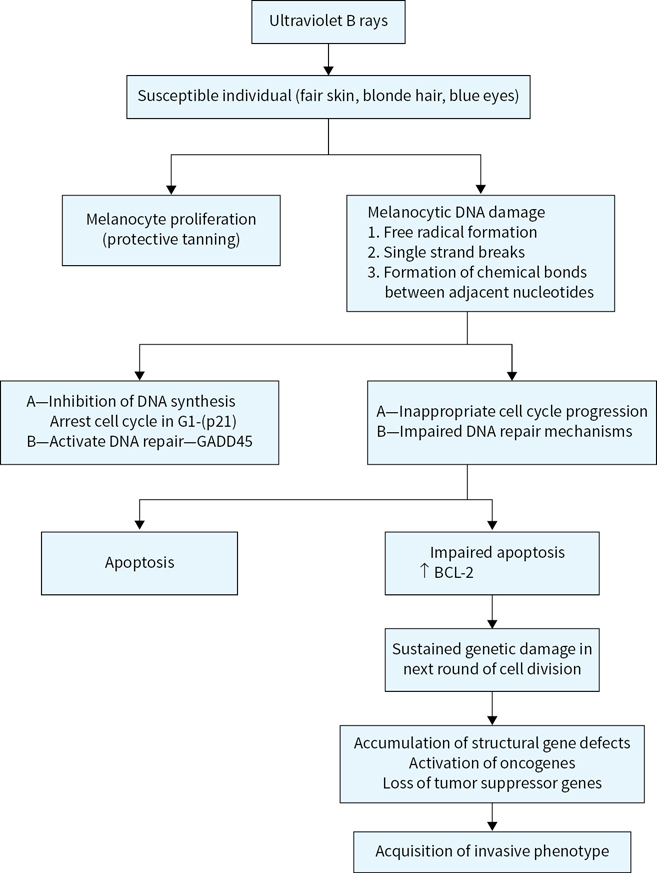

Ultraviolet rays’ exposure is a major risk factor for melanoma development and is related to (Fig. 22.1)

Ultraviolet rays’ exposure is a major risk factor for melanoma development and is related to (Fig. 22.1)

•Intermittent intense exposure

•Exposure at a young age

•Fair skin, blue eyes, blonde or red hair, propensity for sunburns, and inability to tan

About 5% to 10% of melanomas are familial among which up to 40% have hereditary basis.

About 5% to 10% of melanomas are familial among which up to 40% have hereditary basis.

A tumor suppressor gene cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (CDKN2A).

A tumor suppressor gene cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (CDKN2A).

is the most commonly implicated gene located on the short arm of chromosome 9, which could be either mutated or suppressed by epigenetic silencing.

is the most commonly implicated gene located on the short arm of chromosome 9, which could be either mutated or suppressed by epigenetic silencing.

The protective effect of CDKN2A is mediated by encoded protein p16INK4A.

The protective effect of CDKN2A is mediated by encoded protein p16INK4A.

Other candidate genes in this category include cyclin-dependent kinase 4 (CDK4) and CDKN2A/p14 alternate reading frame CDKN2A/ARF.

Other candidate genes in this category include cyclin-dependent kinase 4 (CDK4) and CDKN2A/p14 alternate reading frame CDKN2A/ARF.

Mutations in the telomere-related genes such as POT1, shelterin complex genes, and TERT have been identified in families with clusters of cutaneous melanoma.

Mutations in the telomere-related genes such as POT1, shelterin complex genes, and TERT have been identified in families with clusters of cutaneous melanoma.

A high-risk variant of the α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone receptor gene (MC1R) located on chromosome 16q24 and associated with red hair and freckles confer high risk of familial melanoma in families segregating the CDKN2A gene.

A high-risk variant of the α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone receptor gene (MC1R) located on chromosome 16q24 and associated with red hair and freckles confer high risk of familial melanoma in families segregating the CDKN2A gene.

Hereditary basis of melanoma should be suspected in the following circumstances:

Hereditary basis of melanoma should be suspected in the following circumstances:

•Individuals with three or more primary cutaneous melanomas

•Melanoma at a young age and a family history of melanoma (mean age between 30 and 40)

•Individuals with cutaneous melanoma and a family history of at least one invasive melanoma and two or more other diagnoses of melanoma and/or pancreatic cancer among first- or second-degree relatives on the same side of the family

•Melanoma associated in patients with dysplastic nevi and atypical nevi

Precursor lesions of melanoma include the following:

Precursor lesions of melanoma include the following:

•Dysplastic nevi genetic locus of which resides on short arm of chromosome 1

•Congenital nevi and acquired melanocytic nevi

Risk Factors for Cutaneous Melanoma

Xeroderma pigmentosum (caused by mutations in UV damage repair genes)

Xeroderma pigmentosum (caused by mutations in UV damage repair genes)

Familial atypical mole melanoma syndrome (FAMMS)

Familial atypical mole melanoma syndrome (FAMMS)

Advanced age and immune-suppressed states

Advanced age and immune-suppressed states

Melanoma in a first-degree relative and previous history of melanoma

Melanoma in a first-degree relative and previous history of melanoma

Common Chromosomal Abnormalities in Melanoma

Early chromosomal abnormalities:

Early chromosomal abnormalities:

Late chromosomal abnormalities:

Late chromosomal abnormalities:

•Deletion of 6q, 11q23

•Loss of terminal part of 1p

•Duplication of chromosome 7

Clinical Features of Cutaneous Melanoma (ABCDE)

Most cutaneous melanoma lesions are pigmented and display asymmetry (A), irregular borders (B), variegate colors (C) with shades of brown, black, pink, white, red, or blue have diameter of at least 6 mm (D) and evolve in size, color, nodularity, ulceration, or bleeding (E). Cutaneous melanoma may be painless or, at times, cause itching and discomfort.

Most cutaneous melanoma lesions are pigmented and display asymmetry (A), irregular borders (B), variegate colors (C) with shades of brown, black, pink, white, red, or blue have diameter of at least 6 mm (D) and evolve in size, color, nodularity, ulceration, or bleeding (E). Cutaneous melanoma may be painless or, at times, cause itching and discomfort.

Rarely (<1%) cutaneous melanomas lack pigment (amelanotic) posing diagnostic challenges.

Rarely (<1%) cutaneous melanomas lack pigment (amelanotic) posing diagnostic challenges.

Cutaneous melanoma is more common in the lower extremities in women, the trunk in men, and head and neck region in the elderly subjects although it can occur anywhere in the body.

Cutaneous melanoma is more common in the lower extremities in women, the trunk in men, and head and neck region in the elderly subjects although it can occur anywhere in the body.

Pathologic Diagnosis of Cutaneous Melanoma

Morphologically identified melanoma cells express vimentin and are negative for cytokeratin.

Morphologically identified melanoma cells express vimentin and are negative for cytokeratin.

Diagnosis is confirmed by the detection of melanoma-associated antigens such as S-100, premelanosomal protein HMB-45, nerve growth factor receptor, and tyrosinase-related protein 1 (MEL-5) detected by immunohistochemistry.

Diagnosis is confirmed by the detection of melanoma-associated antigens such as S-100, premelanosomal protein HMB-45, nerve growth factor receptor, and tyrosinase-related protein 1 (MEL-5) detected by immunohistochemistry.

In melanoma in situ, the transformed melanocyte is restricted to the epidermal layer of skin.

In melanoma in situ, the transformed melanocyte is restricted to the epidermal layer of skin.

Invasive melanoma is defined by its invasion of the dermis quantified by Clark and Breslow.

Invasive melanoma is defined by its invasion of the dermis quantified by Clark and Breslow.

Histologic characteristics (microstaging) help prognosticate the tumor and include, tumor thickness, mitosis, ulceration, Clark levels, vascular or perineural invasion, lymphocyte infiltration, morphologic variants, and regression.

Histologic characteristics (microstaging) help prognosticate the tumor and include, tumor thickness, mitosis, ulceration, Clark levels, vascular or perineural invasion, lymphocyte infiltration, morphologic variants, and regression.

Independent variables of melanoma prognosis are Breslow thickness, mitosis, ulceration, and older age (Table 22.2).

Independent variables of melanoma prognosis are Breslow thickness, mitosis, ulceration, and older age (Table 22.2).

Table 22.2Independent Prognostic Factors of Cutaneous Melanoma

Prognostic Factors | Good Prognostic Factors | Poor Prognostic Factors |

Tumor thickness (Breslow) | Thin tumor (tumor ≤1 mm deep) | Thick tumor (tumor >1 mm deep) |

Ulceration | No ulceration of tumor | Tumor ulceration present |

Mitosis | No tumor cell mitosis | Tumor mitosis present |

Age | Less than 60 years | Sixty years or over |

Clinico-histologic Types of Melanoma

Breslow used an ocular micrometer to measure the vertical depth of penetration of tumor from the granular layer of the epidermis or from the base of the ulcerated melanoma to the deepest identifiable contiguous melanoma cell.

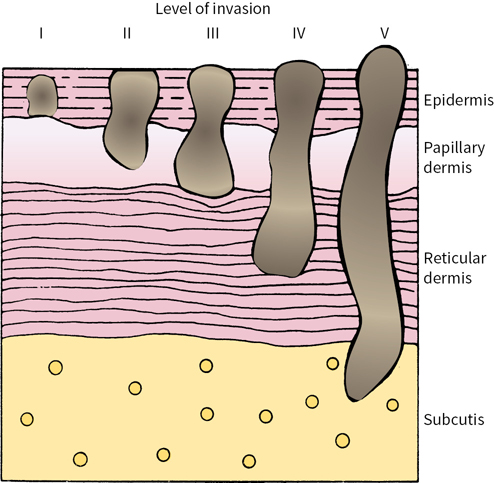

Clark et al. subdivided melanoma invasion of the papillary dermis into a deep group in which tumor cells accumulate at the junction of the papillary and reticular dermis and a superficial group in which tumor cells did not invade deeper layers (Fig. 22.2).

FIGURE 22.2 Schematic diagram of Clark levels of invasion.

Principles of American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Melanoma Staging

Melanoma stage is based on the information derived from three key categories (TNM):

(T) Tumor characteristics on microscopic examination

(T) Tumor characteristics on microscopic examination

(N) Nodes—status of the regional lymph node metastasis

(N) Nodes—status of the regional lymph node metastasis

(M) Distant metastasis—either present or absent

(M) Distant metastasis—either present or absent

In AJCC staging, melanoma is divided into four stages:

Stage I—Thin melanoma (subdivided into IA and IB)

Stage I—Thin melanoma (subdivided into IA and IB)

Stage II—Deeper melanoma without lymph node metastasis (subdivided into IIA, IIB, and IIC)

Stage II—Deeper melanoma without lymph node metastasis (subdivided into IIA, IIB, and IIC)

Stage III—Melanoma spread to regional lymph nodes (subdivided into IIIA, IIIB, and IIIC)

Stage III—Melanoma spread to regional lymph nodes (subdivided into IIIA, IIIB, and IIIC)

Stage IV—Distant metastasis (subdivided into M1a, M1b, and M1c)

Stage IV—Distant metastasis (subdivided into M1a, M1b, and M1c)

The following factors are taken into consideration for subdividing each stage into A, B, or C:

Stages IA and IB: Depth of invasion, ulceration, and mitosis

Stages IA and IB: Depth of invasion, ulceration, and mitosis

Stages IIA, IIB, and IIC: Depth of invasion, presence, or absence of ulceration.

Stages IIA, IIB, and IIC: Depth of invasion, presence, or absence of ulceration.

Stages IIIA, IIIB, and IIIC: Depth, ulceration of the primary melanoma, number of lymph node metastases, microscopic versus macroscopic (clinically palpable) lymph nodes, intralymphatic metastases (in transit metastasis), or satellite lesions.

Stages IIIA, IIIB, and IIIC: Depth, ulceration of the primary melanoma, number of lymph node metastases, microscopic versus macroscopic (clinically palpable) lymph nodes, intralymphatic metastases (in transit metastasis), or satellite lesions.

Sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) is recommended for detection of occult melanoma metastasis in a lymph node when clinical examination is negative.

Sentinel lymph node is not usually recommended in a thin melanoma ≤1mm deep, without mitosis or ulceration since in such a case lymph node metastasis is rare.

Sentinel lymph node is not usually recommended in a thin melanoma ≤1mm deep, without mitosis or ulceration since in such a case lymph node metastasis is rare.

The sensitivity of finding melanoma cells or clusters in a sentinel lymph node is enhanced by subjecting it for immunohistochemical staining of melanoma-associated antigens.

The sensitivity of finding melanoma cells or clusters in a sentinel lymph node is enhanced by subjecting it for immunohistochemical staining of melanoma-associated antigens.

Dividing stage IV melanoma into M1a, M1b, and M1c helps characterize prognosis:

Dividing stage IV melanoma into M1a, M1b, and M1c helps characterize prognosis:

M1a—Metastasis to the distant lymph node and subcutaneous tissues (favorable stage IV)

M1a—Metastasis to the distant lymph node and subcutaneous tissues (favorable stage IV)

M1b—Lung metastasis (intermediate prognosis)

M1b—Lung metastasis (intermediate prognosis)

M1c—Non–lung visceral metastasis such as liver, bone, brain, and other organs (poor prognosis)

M1c—Non–lung visceral metastasis such as liver, bone, brain, and other organs (poor prognosis)

Serum enzyme lactate dehydrogenase enzyme (LDH) if elevated upgrades M1a and M1b to M1c

Serum enzyme lactate dehydrogenase enzyme (LDH) if elevated upgrades M1a and M1b to M1c

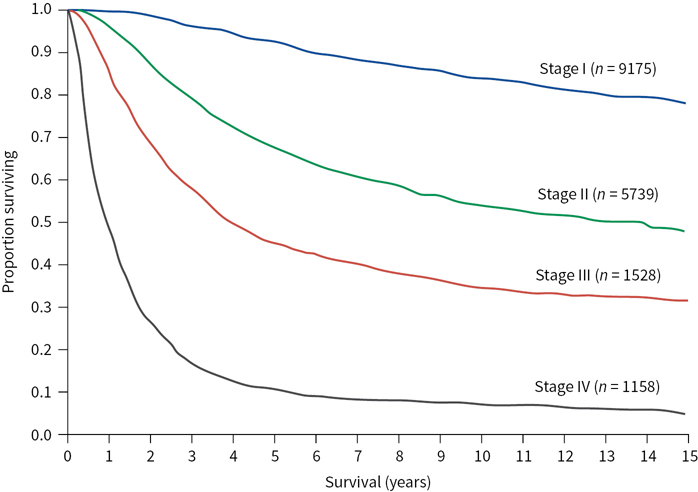

Prediction of Patient Outcome Based on AJCC Melanoma Staging 2009 (Figure 22.3)

FIGURE 22.3 Relationship between the stage of melanoma and survival (20-year follow-up). (Kaplan-Meier survival curves adapted from Balch CM, Gershenwald JE, Soong S-J, et al. Final version of 2009 AJCC melanoma staging and classification. J Clin Oncol. 2009; 27:6199–6206.)

Low risk: Stages I and IIA (melanoma-specific mortality less than 25% at 20 years)

Low risk: Stages I and IIA (melanoma-specific mortality less than 25% at 20 years)

Medium to high risk: Stages IIB, IIC, and III (melanoma-specific mortality between 55% and 75% at 20 years)

Medium to high risk: Stages IIB, IIC, and III (melanoma-specific mortality between 55% and 75% at 20 years)

Poor risk: Stage IV (melanoma-specific mortality more than 90% at 5 years)

Poor risk: Stage IV (melanoma-specific mortality more than 90% at 5 years)

Cutaneous Melanoma: Prevention and Early Diagnosis

Public health education measures specific for melanoma include emphasis on spreading awareness of melanoma as a serious cancer, focus on its risk factors such as ultraviolet light exposure and tanning booth use, preventive strategies such as sun avoidance techniques, light clothing, sun screen use, and early diagnosis by periodic self-skin and total body skin examinations (TBSE).

TBSE performed by a dermatologist provides the opportunity to identify suspicious skin lesions for biopsy and early diagnosis.

Digital photography helps to track suspicious skin lesions over time in patients with multiple nevi or dysplastic nevus syndrome.

Digital photography helps to track suspicious skin lesions over time in patients with multiple nevi or dysplastic nevus syndrome.

Dermoscopy (epiluminescence microscopy) improves diagnostic sensitivity, and utilizes either a dermatoscope or 10× ocular scope (microscope ocular eyepiece held upside down) to visualize structures and patterns in pigmented skin lesions not discernible to the eye.

Dermoscopy (epiluminescence microscopy) improves diagnostic sensitivity, and utilizes either a dermatoscope or 10× ocular scope (microscope ocular eyepiece held upside down) to visualize structures and patterns in pigmented skin lesions not discernible to the eye.

Cutaneous Melanoma Management

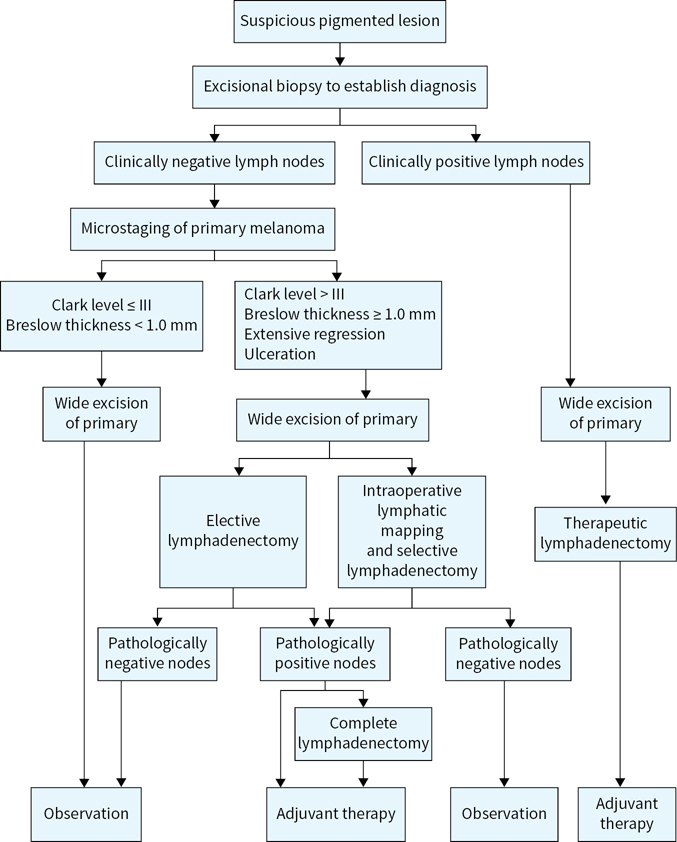

An algorithm for melanoma management is presented in Figure 22.4.

FIGURE 22.4 Algorithm for cutaneous melanoma management.

Primary surgical treatment: Principles

Complete excision of primary melanoma confirmed by comprehensive histologic examination of the entire excised specimen and assessment of melanoma metastasis to the regional lymph node (except in stage IA where the risk is low) forms the basis of surgical treatment.

Complete excision of primary melanoma confirmed by comprehensive histologic examination of the entire excised specimen and assessment of melanoma metastasis to the regional lymph node (except in stage IA where the risk is low) forms the basis of surgical treatment.

Recommendations for extent of surgical margins vary by depth of cutaneous melanoma (Table 22.3), but risk of local recurrence relates to completeness rather than extent of surgical margins.

Recommendations for extent of surgical margins vary by depth of cutaneous melanoma (Table 22.3), but risk of local recurrence relates to completeness rather than extent of surgical margins.

Table 22.3Recommended Margin of Surgical Excision Based upon Pathologic Stage of Primary Cutaneous Melanoma

Pathologic Stage | Tumor Thickness | Margin of Excision |

p tis | Melanoma in situ | 5 mm |

pT1 and pT2 | 0–2 mm | 1 cm |

pT3 | 2–4 mm | 1–2 cm |

pT4 | >4 mm | 2–3 cm |

Assessment of the Regional Lymph Node Metastasis and Lymph Node Dissection: Principle

The risk of regional lymph node metastasis is directly proportional to the depth of invasion, tumor ulceration, and mitosis, all reflecting tumor biology.

The risk of regional lymph node metastasis is directly proportional to the depth of invasion, tumor ulceration, and mitosis, all reflecting tumor biology.

Historically, complete excision of primary cutaneous melanoma is followed with elective, therapeutic, or delayed lymph node dissection from the respective basin.

Elective lymph node dissection consists of removal of all the lymph nodes from the respective basin grounded on a belief that metastasis is present, without positive identification of a sentinel lymp node.

Elective lymph node dissection consists of removal of all the lymph nodes from the respective basin grounded on a belief that metastasis is present, without positive identification of a sentinel lymp node.

•Elective lymph node dissection carried significant morbidity of the procedure to the patient in the clinical circumstances where lymph node metastasis did not occur and is no longer recommended.

•In head and neck melanoma where the site of lymphatic drainage is unpredictable, elective lymph node dissection may be considered on a case by case basis.

Therapeutic lymph node dissection is performed if a clinically enlarged lymph node is present that is considered or proven to harbor metastasis.

Therapeutic lymph node dissection is performed if a clinically enlarged lymph node is present that is considered or proven to harbor metastasis.

Delayed lymph node dissection is performed when initially nonpalpable regional lymph nodes become enlarged over a follow-up period due to the delayed onset of lymph node metastasis. With the widespread adoption of SLNB, this scenario is much less common.

Delayed lymph node dissection is performed when initially nonpalpable regional lymph nodes become enlarged over a follow-up period due to the delayed onset of lymph node metastasis. With the widespread adoption of SLNB, this scenario is much less common.

Lymphoscintigraphy and Sentinel Node Biopsy

Lymphoscintigraphy is a tool to identify sentinel lymph node in the corresponding lymph node basin for the detection of occult regional lymph node metastasis.

Lymphoscintigraphy is a tool to identify sentinel lymph node in the corresponding lymph node basin for the detection of occult regional lymph node metastasis.

Characteristics of a sentinel lymph node:

Characteristics of a sentinel lymph node:

•First lymph node in the basin at the greatest risk of metastasis.

•Easily accessible and identified by lymphoscintigraphy.

•Pathologic evaluation helps to detect occult melanoma metastasis.

•Success rate of sentinel lymph node detection is 95% in experienced hands with less than 5% false negative rates.

Surgical approach to obtain a sentinel lymph node: lymphoscintigraphy

Surgical approach to obtain a sentinel lymph node: lymphoscintigraphy

•Preoperative lymphoscintigraphy uses a vital blue dye injected around the cutaneous melanoma that provides a road map of the lymph node basin.

•Intraoperative lymphoscintigraphy uses a radio colloid injection around the primary tumor, and a handheld device detects the radioactivity from the involved lymph node.

•The combination of the vital blue dye and radio colloid helps the surgeon navigate the identity of sentinel lymph node in the respective nodal basin in 95% of cases.

Implications of SLNB results:

Implications of SLNB results:

•Only those patients with melanoma metastasis to the sentinel lymph node (positive sentinel lymph node) will undergo complete lymph node dissection.

•A negative sentinel lymph node saves the patient the morbidity of lymph node dissection.

•SLNB–guided information about the extent of lymph node metastasis helps in prognostication of primary melanoma and reduces the risk of recurrence in the lymph node basin. Its impact on overall survival is not clear.

The Multicenter Selective Lymphadenectomy Trial I (MSLT-1) was designed to find if SLNB followed by early complete lymph node dissection would have an overall survival benefit in patients with intermediate thickness melanoma (1.2 to 3.5 mm depth).

The results showed improved 5-year disease-free survival (83.2% vs. 53.4%) in subjects assigned to lymphoscintigraphy whose SLNB was negative for metastasis compared to those whose sentinel lymph nodes were positive.

The results showed improved 5-year disease-free survival (83.2% vs. 53.4%) in subjects assigned to lymphoscintigraphy whose SLNB was negative for metastasis compared to those whose sentinel lymph nodes were positive.

A subgroup analysis was suggestive of the improved melanoma specific five-year survival for patients with node-positive microscopic disease who underwent immediate lymph node dissection compared to the observation arm who underwent lymph node dissection upon macroscopic lymph node metastasis (72.3% vs. 52.4%), but this did not translate into an overall melanoma-specific survival benefit in the intention-to-treat population.

A subgroup analysis was suggestive of the improved melanoma specific five-year survival for patients with node-positive microscopic disease who underwent immediate lymph node dissection compared to the observation arm who underwent lymph node dissection upon macroscopic lymph node metastasis (72.3% vs. 52.4%), but this did not translate into an overall melanoma-specific survival benefit in the intention-to-treat population.

We should include MSLT-2 results as they will be available soon.

Ongoing debate about SLNB and completion lymphadenectomy:

Is completion lymphadenectomy necessary in all sentinel lymph node positive tumors?

Is completion lymphadenectomy necessary in all sentinel lymph node positive tumors?

Can tumor bulk in sentinel lymph node determine need for completion lymphadenectomy?

Can tumor bulk in sentinel lymph node determine need for completion lymphadenectomy?

Melanoma Sentinel Lymphadenectomy Trial (MSLT-2) is evaluating the therapeutic benefit of completion lymphadenectomy after positive SLNB. Patients with positive SLNB are randomized to either completion lymphadenectomy or nodal observation by periodic ultrasound. The results are awaited.

Melanoma Sentinel Lymphadenectomy Trial (MSLT-2) is evaluating the therapeutic benefit of completion lymphadenectomy after positive SLNB. Patients with positive SLNB are randomized to either completion lymphadenectomy or nodal observation by periodic ultrasound. The results are awaited.

The German DECOG study group randomized cutaneous melanoma patients with a positive sentinel lymph node to either completion lymphadenectomy or nodal observation. In a short median follow-up of 34 months, there were no differences in recurrence-free survival, distant metastases-free survival or melanoma-specific survival.

The German DECOG study group randomized cutaneous melanoma patients with a positive sentinel lymph node to either completion lymphadenectomy or nodal observation. In a short median follow-up of 34 months, there were no differences in recurrence-free survival, distant metastases-free survival or melanoma-specific survival.

The Sunbelt Melanoma Trial reported no difference in overall survival after complete lymph node dissection compared to observation after positive SLNB (although the study was underpowered and this was not be the main objective of the study).

The Sunbelt Melanoma Trial reported no difference in overall survival after complete lymph node dissection compared to observation after positive SLNB (although the study was underpowered and this was not be the main objective of the study).

EORTC 1208 Minitub is a prospective registry that aims to examine which cutaneous melanoma patients with sentinel lymph node metastasis will benefit from completion lymph node dissection based on sentinel lymph node tumor burden.

EORTC 1208 Minitub is a prospective registry that aims to examine which cutaneous melanoma patients with sentinel lymph node metastasis will benefit from completion lymph node dissection based on sentinel lymph node tumor burden.

Adjuvant Treatment of Melanoma in Patients at Risk of Recurrence after Surgery

Adjuvant treatment of melanoma is recommended in stage IIB, IIC, and III patients since follow-up studies following surgical treatment of cutaneous melanoma showed a high rate of relapse and melanoma specific mortality (35% to 75%).

Interferon alpha (IFNα-2b) as adjuvant treatment of cutaneous melanoma: Principles based on antiproliferative and immunomodulatory effects, prolonged use of IFNα-2b (high dose, low dose, intermediate dose for variable periods of time) has been extensively studied in an adjuvant setting after surgery and approved by the FDA in the adjuvant setting (Table 22.4).

Table 22.4FDA-approved Adjuvant Therapy in Cutaneous Melanoma

Study Group | Treatment Regimen |

EORTC 18071 Ipilimumab vs. placebo | Ipilimumab Induction phase: Ipilimumab 10mg/Kg IV every 3 weeks for four doses |

Maintenance phase: Ipilimumab 10mg/Kg every 12 weeks for up to 3 years | |

ECOG E 1684 Interferon alpha vs. observation | High-dose interferon treatment Induction phase: IFN-α 2b, 20 million units/m2/dose IV, 5 d/wk × 4 wk (total dose/wk, 100 million units/m2), followed by |

| Maintenance phase: IFN-α 2b, 10 million units/m2 SC, three times/wk for 48 wk (total dose/wk, 30 million units/m2) vs. observation |

ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; EORTC, European Organization for the Research and Treatment of Cancer; IV intravenous; SC subcutaneous.

High dose IFNα-2b treatment conferred consistent relapse and disease-free survival benefits in multiple trials.

High dose IFNα-2b treatment conferred consistent relapse and disease-free survival benefits in multiple trials.

Its impact upon overall survival has been variable and less consistent.

Its impact upon overall survival has been variable and less consistent.

Reducing the dose (low dose) or duration (induction only) of IFNα-2b for one month does not provide clinical benefit compared to high dose treatment.

Reducing the dose (low dose) or duration (induction only) of IFNα-2b for one month does not provide clinical benefit compared to high dose treatment.

Pegylated form of IFN-α (slow release) given subcutaneously once weekly for up to 5 years conferred relapse-free survival advantage without overall survival benefit.

Pegylated form of IFN-α (slow release) given subcutaneously once weekly for up to 5 years conferred relapse-free survival advantage without overall survival benefit.

The predominant toxicities of high-dose IFNα-2b include severe flu-like symptoms, chronic fatigue, nausea, bone marrow suppression, liver toxicity, and depression that adversely affect quality of life and may compromise the intended benefit.

The predominant toxicities of high-dose IFNα-2b include severe flu-like symptoms, chronic fatigue, nausea, bone marrow suppression, liver toxicity, and depression that adversely affect quality of life and may compromise the intended benefit.

The decision to use interferon in the adjuvant setting of cutaneous melanoma treatment should be based on the perceived relative merits of disease control, quality of life, and financial cost.

Ipilimumab (anti CTLA-4 antibody) as an adjuvant therapy of melanoma: Principles based on the survival benefit conferred by Ipilimumab in about 25% of patients in metastatic melanoma, it was investigated as a candidate in the adjuvant setting.

Ipilimumab administered intravenously at a dose of 10 mg/kg body weight every 3 weeks for four doses (induction phase) followed by same dose given every 12 weeks for up to 3 years (maintenance phase) improved relapse-free survival and overall survival compared to placebo.

Ipilimumab administered intravenously at a dose of 10 mg/kg body weight every 3 weeks for four doses (induction phase) followed by same dose given every 12 weeks for up to 3 years (maintenance phase) improved relapse-free survival and overall survival compared to placebo.

At a median follow-up of 27.4 months, relapse-free survival was 26.1 months following Ipilimumab versus 17.1 months in patients receiving placebo (HR 0.75, P=.0013).

At a median follow-up of 27.4 months, relapse-free survival was 26.1 months following Ipilimumab versus 17.1 months in patients receiving placebo (HR 0.75, P=.0013).

At 5 years of follow-up, Ipilimumab treatment-led recurrence-free survival was translated into distant metastasis-free survival and overall survival compared to placebo. The overall survival rate at 5 years was 65.4% in the Ipilimumab group, as compared with 54.4% in the placebo group (hazard ratio for death from any cause, 0.72, P = 0.001).

At 5 years of follow-up, Ipilimumab treatment-led recurrence-free survival was translated into distant metastasis-free survival and overall survival compared to placebo. The overall survival rate at 5 years was 65.4% in the Ipilimumab group, as compared with 54.4% in the placebo group (hazard ratio for death from any cause, 0.72, P = 0.001).

Ipilimumab-induced survival advantage occurred in all subgroups of stage III patients including those with microscopic as well as macroscopic recurrences and irrespective of ulceration of the primary melanoma. Ipilimumab was FDA approved for stage III melanoma in 2016 (Table 22.4).

Ipilimumab-induced survival advantage occurred in all subgroups of stage III patients including those with microscopic as well as macroscopic recurrences and irrespective of ulceration of the primary melanoma. Ipilimumab was FDA approved for stage III melanoma in 2016 (Table 22.4).

Serious autoimmune side effects referred to as immune-related adverse events (irAE) of Ipilimumab led to discontinuation of treatment in 52% of patients (39% patients in induction phase and 13% during maintenance phase).

Serious autoimmune side effects referred to as immune-related adverse events (irAE) of Ipilimumab led to discontinuation of treatment in 52% of patients (39% patients in induction phase and 13% during maintenance phase).

Common irAE involved gastrointestinal system (16%), liver (11%), and endocrine organs (8%).

Common irAE involved gastrointestinal system (16%), liver (11%), and endocrine organs (8%).

Five patients (1%) died of severe irAE including 3 from colitis two of whom had perforation, 1 patient of myocarditis and 1developed Guillain-Barré syndrome and multi-organ failure.

Five patients (1%) died of severe irAE including 3 from colitis two of whom had perforation, 1 patient of myocarditis and 1developed Guillain-Barré syndrome and multi-organ failure.

Biochemotherapy as adjuvant treatment of cutaneous melanoma: Principles

Biochemotherapy produced favorable response rates and occasional durable responses in newly diagnosed metastatic melanoma patients leading to its study in the adjuvant setting.

Biochemotherapy administered every 3 weeks with G-CSF support for three cycles was compared to high dose interferon α 2b treatment.

Biochemotherapy administered every 3 weeks with G-CSF support for three cycles was compared to high dose interferon α 2b treatment.

The results showed a significant relapse-free survival advantage for biochemotherapy without overall survival benefit but it also caused severe grade 3/4 toxicities.

The results showed a significant relapse-free survival advantage for biochemotherapy without overall survival benefit but it also caused severe grade 3/4 toxicities.

Some of the ongoing clinical trials in adjuvant treatment of melanoma:

•A phase III ECOG 1609 trial is comparing two doses of ipilimumab (3 mg/kg and 10 mg/kg) to high-dose interferon. This study may help find the optimal dose of ipilimumab as compared to high-dose interferon alpha.

•A randomized, double-blind phase III trial of the EORTC Melanoma Group is studying the anti PD-1 agent pembrolizumab versus placebo after complete resection of high-risk stage III melanoma. The primary end point is recurrence-free survival, secondary end points are distant metastases-free survival and overall survival. Patients will be stratified by PD-L1 expression. At relapse, patients will be unblended and allowed to cross over to the active treatment arm if on placebo.

•COMBI-AD is an ongoing phase III trial that plans to randomize 852 patients with stage III BRAF V600E/K mutation-positive melanoma to combined dabrafenib and trametinib versus placebo. The primary end point is RFS.

•BRIM-8 plans to randomize 725 patients with stage IIC and III BRAF V600 mutation-positive melanoma to adjuvant vemurafenib versus placebo. The primary end point is DFS.

Role of Radiation Therapy in Melanoma

Radiation therapy of melanoma may be used in the following clinical scenarios:

Bulky and/or four or more lymph node metastasis or extracapsular spread in a lymph node

Bulky and/or four or more lymph node metastasis or extracapsular spread in a lymph node

Local recurrence of melanoma in a previously dissected lymph node basin

Local recurrence of melanoma in a previously dissected lymph node basin

After surgical resection of desmoplastic melanoma with neurotropism

After surgical resection of desmoplastic melanoma with neurotropism

Pain relief of melanoma metastasis to the musculoskeletal region

Pain relief of melanoma metastasis to the musculoskeletal region

Brain metastasis of melanoma

Brain metastasis of melanoma

Radiation therapy in brain metastasis of melanoma includes the following:

Whole-brain radiation if multiple and/or large size brain metastases are present.

Whole-brain radiation if multiple and/or large size brain metastases are present.

Stereotactic brain radiation is preferred in small-sized or fewer (two to three) brain metastases.

Stereotactic brain radiation is preferred in small-sized or fewer (two to three) brain metastases.

Results of studies by Skibber et al. and others suggest that external radiation to the whole brain after resection of solitary brain metastasis of malignant melanoma has survival benefits.

Isolated Limb Perfusion or Infusion as a Treatment of Melanoma: Principles

To deliver maximally tolerated chemotherapy in patients with locally advanced and metastatic melanoma to a regionally confined tumor area such as a limb while limiting systemic toxicity.

Isolated limb perfusion (ILP): Involves hyperthermia and oxygenation of the circulation that potentiates the tumoricidal effects of the chemotherapeutic agents such as melphalan (L-PAM), thiotepa, mechlorethamine with or without tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α), and IFN-γ.

Isolated limb perfusion (ILP): Involves hyperthermia and oxygenation of the circulation that potentiates the tumoricidal effects of the chemotherapeutic agents such as melphalan (L-PAM), thiotepa, mechlorethamine with or without tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α), and IFN-γ.

Isolated limb infusion (ILI): Is a simplified and minimally invasive procedure developed at the Sydney Melanoma Unit (SMU) intended to obtain the benefits of ILP without major disadvantages. It is a low-flow ILP procedure performed via percutaneous catheters without oxygenation.

Isolated limb infusion (ILI): Is a simplified and minimally invasive procedure developed at the Sydney Melanoma Unit (SMU) intended to obtain the benefits of ILP without major disadvantages. It is a low-flow ILP procedure performed via percutaneous catheters without oxygenation.

Both procedures may help improve the patient’s quality of life by controlling the local pain following effective shrinkage of local tumor metastasis that is not possible with surgery or at high risk of recurrence after surgery. It does not provide a survival advantage.

Potential complications of the procedure include ischemia of the limb, peripheral neuropathy, and bone marrow suppression.

Management of Patients with Metastatic Melanoma

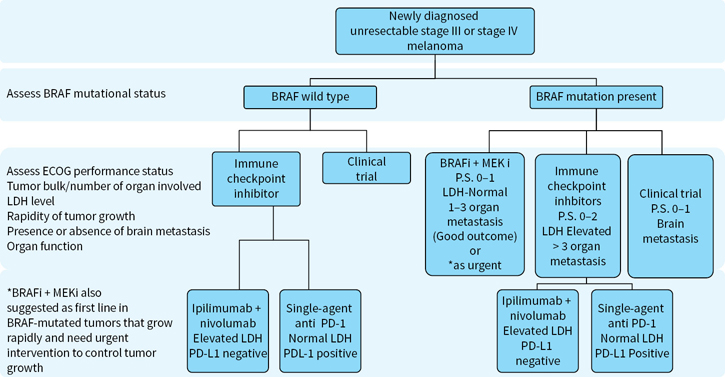

The management options for a patient with metastatic melanoma have expanded following the recent FDA approvals of immune based and targeted therapy (Figure 22.5). Surgery has a role in resection of isolated metastasis while chemotherapy may have a role in palliative treatment of selected patients who have failed upfront therapy.

FIGURE 22.5 Algorithm for treatment of newly diagnosed unresectable stage III/IV melanoma.

TABLE 22.6 FDA-approved Systemic Immune Therapy of Metastatic Melanoma

High dose IL-2 | Pembrolizumab | Nivolumab | Ipilimumab +Nivolumab |

High-dose IL-2 administered at 600,000 to 720,000 units per kilogram by 15 min bolus intravenous infusion every 8 h on days 1 to 5 and 15 to 19. Treatment courses were repeated at 8- to 12-wk intervals in responding patients until complete response is achieved or toxicity sets in that the physician decides to stop treatment for safety reasons | 2mg/Kg dose IV over 30 min every 3 wks for up to 2 y unless disease progression or unacceptable toxicity occurred | 3mg/kg IV over 30 min every 2 wks for up to 2 y unless disease progression or unacceptable toxicity occurred | Induction phase: Ipilimumab 3 mg/Kg IV over 90 min plus nivolumab 1mg/Kg IV over 30 min every 3 wks x 4 doses, followed by Maintenance phase: Nivolumab at 3mg/Kg IV every 2 wks for up to 2 y unless disease progression or unacceptable toxicity occurred |

TABLE 22.7 FDA-approved Immune Therapy and Their Efficacy in Metastatic Melanoma

Treatment | Complete Remission | Partial Remission | Stable Disease | Clinical Benefit | MPFS Months | MOS Months | 1-year Survival | 2- and 3-year Survival Rates |

High-dose Interleukin-2 (IL-2) | 6% | 10% | NA | 20% | 13.1 | 11.4 | 50% | 6% |

Ipilimumab | 1.5% | 9.5% | 17.5% | 28.5% | 2.9 | 10.1 | 45.6% | 23.5% |

Pembrolizumab | 6.1% | 26.8% | 4.1 | NR | 68.4% | |||

Nivolumab | 7.6% | 32.4% | 16.7% | 56.7% | 5.1 | NR | 72.9% | |

Ipilimumab + Nivolumab | 11.5% | 46.2% | 13.1% | 70.8% | 11.5 | NR | NR | NA |

T-VEK* (intra-tumoral injection) | 10.8%* | 15.6% | NR | 26.4% |

Immune-based Therapy of Metastatic Melanoma: Principles

Melanoma is considered to be one of the best models of an immunogenic tumor attracting lymphocytes at both the primary and metastatic sites.

Melanoma is considered to be one of the best models of an immunogenic tumor attracting lymphocytes at both the primary and metastatic sites.

A number of well-defined melanoma antigens have been identified both at a protein and gene level that evoke a cellular immune-based antimelanoma response (Table 22.5).

A number of well-defined melanoma antigens have been identified both at a protein and gene level that evoke a cellular immune-based antimelanoma response (Table 22.5).

Antigen-specific CD8+ Cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) lead the antimelanoma response with critical help from CD4+ helper T cells and antigen-presenting cells (APCs).

Antigen-specific CD8+ Cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) lead the antimelanoma response with critical help from CD4+ helper T cells and antigen-presenting cells (APCs).

Table 22.5Melanoma-associated Antigens, Peptides, and Presenting MHC Molecules

Melanoma Antigens | Peptides | Presenting MHC Molecules |

MAGE-A1a | EADPTGHSY | HLA-A1 & B37 |

MAGE-A1a | TSCILESLFRAVITK | HLA-DP4 |

MAGE-A3a | EVDPIGHLY | HLA-A1 |

NY-ESO-1a | SLLMWITQC | HLA-A2 |

NY-ESO-1a | MPFATPMEA | HLA-B51 |

Melan-A/MART-1b | EAAGIGILTV | HLAB35 |

Melan-A/MART-1b | ILTVILGVL | HLA-A2 |

Tyrosinaseb | MLLAVLYCL | HLA-A2 |

Gp100/pmel17b | KTWGQYWQV | HLA-A2 |

β-Cateninc | SYLDSGIHF | HLA-A24 |

a Shared antigens; b differentiation antigens; c mutated antigens.

Activation of CTLs against melanoma requires two signals: Priming and activation

Signal 1: Priming of CD8+ or CD4+ CTL requires presentation of melanoma antigen (peptide epitope) either by the tumor cell or by the APCs at the MHC class I or MHC class II molecules, respectively, to the T-cell receptor of CD8+ CTL or CD4+ T cells.

Signal 1: Priming of CD8+ or CD4+ CTL requires presentation of melanoma antigen (peptide epitope) either by the tumor cell or by the APCs at the MHC class I or MHC class II molecules, respectively, to the T-cell receptor of CD8+ CTL or CD4+ T cells.

Signal 2: Activation of antigen primed CD8+ or CD4+ CTL requires co-stimulatory signaling through binding of its CD28 molecules with costimulatory molecules B7.1 (CD80) and B7.2 (CD86) on the APCs forming a tight synapse between the two cells critical for signal transduction to the T cell nucleus.

Signal 2: Activation of antigen primed CD8+ or CD4+ CTL requires co-stimulatory signaling through binding of its CD28 molecules with costimulatory molecules B7.1 (CD80) and B7.2 (CD86) on the APCs forming a tight synapse between the two cells critical for signal transduction to the T cell nucleus.

The transcribed genes include cytokines and effector molecules necessary for T cell growth, proliferation and survival as well as tumor killer activity.

The transcribed genes include cytokines and effector molecules necessary for T cell growth, proliferation and survival as well as tumor killer activity.

Activated CD8+ CTLs kill tumor cells directly through production of perforins and granzyme and indirectly by the elaboration of secreted cytokines such as TNF-α, IFN γ, granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (GMCSF), and IL-2 all which help shape the composition of tumor immune microenvironment.

Activated CD8+ CTLs kill tumor cells directly through production of perforins and granzyme and indirectly by the elaboration of secreted cytokines such as TNF-α, IFN γ, granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (GMCSF), and IL-2 all which help shape the composition of tumor immune microenvironment.

Immune-based Treatment Strategies of Metastatic Melanoma: Two Approaches

Specific immunity evoked by melanoma vaccines:

Administration of one or more (monovalent or polyvalent) melanoma antigens as a tumor vaccine either directly or after being pulsed on to monocyte-derived APCs (dendritic cell vaccine) in the subcutis or in the dermis evoke melanoma antigen specific CTLs.

Administration of one or more (monovalent or polyvalent) melanoma antigens as a tumor vaccine either directly or after being pulsed on to monocyte-derived APCs (dendritic cell vaccine) in the subcutis or in the dermis evoke melanoma antigen specific CTLs.

Adjuvants are intended to enhance the immune response and are either premixed with vaccine or preapplied to the skin at the site of the vaccine.

Adjuvants are intended to enhance the immune response and are either premixed with vaccine or preapplied to the skin at the site of the vaccine.

Although successful in a mouse model, induction of antimelanoma specific immunity by vaccine treatment has been unpredictable and not uniformly successful in humans. Also, generation of melanoma-specific T-cell activity did not always correlate with patient responses.

Nonspecific immunity (Table 22.6) involves

Re-activation by T cell growth factors of melanoma antigen sensitized effector T cells or

Re-activation by T cell growth factors of melanoma antigen sensitized effector T cells or

Releasing inhibition of immune checkpoint inhibitors on activated T cells

Releasing inhibition of immune checkpoint inhibitors on activated T cells

Biologic Agents in the Treatment of Metastatic Melanoma

IFN-α was the first recombinant cytokine investigated in phase I and II clinical trials of patients with metastatic melanoma based on its antiproliferative and immunomodulatory effects.

Initial studies showed response rates of about 15% in patients with metastatic melanoma.

Initial studies showed response rates of about 15% in patients with metastatic melanoma.

One-third of these responses were complete and durable.

One-third of these responses were complete and durable.

Responses could be observed up to 6 months after the therapy was initiated.

Responses could be observed up to 6 months after the therapy was initiated.

Small volume disease and uninterrupted use resulted in pronounced responses.

Small volume disease and uninterrupted use resulted in pronounced responses.

These results could not be reproduced in subsequent randomized phase III studies.

These results could not be reproduced in subsequent randomized phase III studies.

Essentially, IFN-α is rarely used as primary therapy for metastatic melanoma.

Essentially, IFN-α is rarely used as primary therapy for metastatic melanoma.

Interleukin 2 (IL-2) is a T cell growth factor produced by T lymphocytes that help growth and expansion of T cells including antigen-specific CD8+ CTL precursors and LAK cells.

Multiple large single institution studies confirmed the ability of high dose IL-2 to cure metastatic melanoma in a small subset of patients leading to its FDA approval in 1998 to treat this disease.

The overall response rate is about 16% that include complete response of about 6%.

The overall response rate is about 16% that include complete response of about 6%.

Responses are more common in patients with subcutaneous, lymph node, and lung metastasis.

Responses are more common in patients with subcutaneous, lymph node, and lung metastasis.

Complete responses are durable in the majority of patients leading to potential cure.

Complete responses are durable in the majority of patients leading to potential cure.

Good baseline performance and treatment naive status are predictive of response.

Good baseline performance and treatment naive status are predictive of response.

Toxicity of high dose IL-2 is dose limiting and is mediated by endothelial damage that result in vascular leak in multiple organs. Common manifestations of toxicity include the following:

High fevers and nausea, vomiting, diarrhea (gastrointestinal), hypotension, cardiac arrhythmias (cardiac), hypoxemia, pleural effusions (pulmonary), azotemia and renal failure (renal), confusion and delirium (central nervous system).

High fevers and nausea, vomiting, diarrhea (gastrointestinal), hypotension, cardiac arrhythmias (cardiac), hypoxemia, pleural effusions (pulmonary), azotemia and renal failure (renal), confusion and delirium (central nervous system).

IL-2 induced defects of neutrophil chemotaxis function require prompt management of infections with antibiotics.

IL-2 induced defects of neutrophil chemotaxis function require prompt management of infections with antibiotics.

Common autoimmune side effects include hypothyroidism, vitiligo anduveitis although a number of other unusual manifestations are described and require prompt management.

Common autoimmune side effects include hypothyroidism, vitiligo anduveitis although a number of other unusual manifestations are described and require prompt management.

Patients with active comorbidities involving heart, lung, kidney, and liver or those with untreated hemorrhagic brain metastasis with vasogenic edema are excluded from high dose IL-2 treatment due to elevated risk of life-threatening complications.

Patients with active comorbidities involving heart, lung, kidney, and liver or those with untreated hemorrhagic brain metastasis with vasogenic edema are excluded from high dose IL-2 treatment due to elevated risk of life-threatening complications.

Lower doses of IL-2 administered either subcutaneously or as a continuous intravenous infusion at 9 to 18 million international units/m2/day for 4 to 5 days have been studied in patients not eligible for high-dose IL-2 treatment. Although total response rates as high as 20% have been reported, complete responses appear to be lower than those with high-dose.

Barriers to Achieving a Successful Immune Response in Melanoma: Immune Regulation and Tolerance

Antigen activated CTLs are “highly regulated” or held in check by a number of biological processes so as to prevent body injury associated with uncontrolled inflammation. These regulatory processes arise from mechanisms either intrinsic to CTL or by a negative influence imposed by regulatory T cells (immune system) or tumor or its microenvironment.

Intrinsic T cell regulation by immune checkpoints:

Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen-4 (CTLA- 4) is a high affinity molecule rapidly expressed by activated T lymphocytes to mediate CTL inhibition by outcompeting CD28 molecule for binding to costimulatory molecules CD80 and CD86 on antigen-presenting cells.

Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen-4 (CTLA- 4) is a high affinity molecule rapidly expressed by activated T lymphocytes to mediate CTL inhibition by outcompeting CD28 molecule for binding to costimulatory molecules CD80 and CD86 on antigen-presenting cells.

Programmed cell death protein-1 (PD-1) receptor is expressed on activated CTL that traffic into tumor tissue intending to destroy it. The PD-1 receptor is expressed by CTL in response to immune stimulatory cytokines (such as interferons) or constitutively in response to inhibitory ligands PD-L1 and PD-L2 expressed on tumor or antigen presenting cells. Ligation of PD-L1/L2 with PD-1 results in CTL exhaustion, premature death, and abrogation of anti-melanoma tumor activity.

Programmed cell death protein-1 (PD-1) receptor is expressed on activated CTL that traffic into tumor tissue intending to destroy it. The PD-1 receptor is expressed by CTL in response to immune stimulatory cytokines (such as interferons) or constitutively in response to inhibitory ligands PD-L1 and PD-L2 expressed on tumor or antigen presenting cells. Ligation of PD-L1/L2 with PD-1 results in CTL exhaustion, premature death, and abrogation of anti-melanoma tumor activity.

Extrinsic mechanisms that regulate the immune response: regulatory T cells

CD8+ CTL responses are regulated by thymus-derived, naturally occurring CD4+CD25+ T cells referred to as nTreg as well as by CD4 + T cells that acquire inhibitory properties upon encountering antigen, referred to as induced T regulatory cells (iTreg).

CD8+ CTL responses are regulated by thymus-derived, naturally occurring CD4+CD25+ T cells referred to as nTreg as well as by CD4 + T cells that acquire inhibitory properties upon encountering antigen, referred to as induced T regulatory cells (iTreg).

Regulatory T cells cause CTL inhibition through inhibitory cytokines or directly by contact inhibition mediated by transcription factor FOXP3.

Regulatory T cells cause CTL inhibition through inhibitory cytokines or directly by contact inhibition mediated by transcription factor FOXP3.

Tumor and its immune microenvironment mediated immune tolerance:

Antigen presentation to CTL is seriously compromised by downregulation of MHC class I molecules by tumor and antigen-presenting cells.

Antigen presentation to CTL is seriously compromised by downregulation of MHC class I molecules by tumor and antigen-presenting cells.

•Immune tolerance is facilitated by inhibitory cytokines such as IL-10, TGF beta, IL-6, and VEG-F produced by tumor cells, hypoxemia, and myeloid-derived suppressive cells.

•Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) is an immune suppressive molecule secreted by the tumor cells, stromal cells, macrophages, and APC in the tumor microenvironment that starve T cells from an important amino acid tryptophan critical for a rate-limiting step in the de-novo biosynthesis of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD). Additionally, accumulation of N-formyl-kynurenine, an IDO induced by product of tryptophan catabolism, inhibit T cell activity.

Reactivating antimelanoma immunity by inhibiting immune checkpoint on T cells: Successful reactivation of antimelanoma immunity is become possible by effective blockade of inhibitory immune checkpoints (CTLA-4 and PD-1) expressed on activated T cell through monoclonal antibodies. Two classes of monoclonal antibodies are approved by the FDA (Table 22.7).

Ipilimumab is an IGG1 monoclonal antibody designed to block inhibitory checkpoint CTLA-4 antigen on activated CD8+ CTLs leading to their reactivation.

Ipilimumab is an IGG1 monoclonal antibody designed to block inhibitory checkpoint CTLA-4 antigen on activated CD8+ CTLs leading to their reactivation.

Pembrolizumab and Nivolumab are two highly selective humanized IgG4-kappa isotype antibodies against PD-1 receptor expressed on the membrane of activated CTLs designed to block its engagement with its two known inhibitory ligands, PD-L1 and PD-L2. The interruption of the PD-1-PD-L1/2 axis reverses adoptive T cell resistance and restores antimelanoma activity.

Pembrolizumab and Nivolumab are two highly selective humanized IgG4-kappa isotype antibodies against PD-1 receptor expressed on the membrane of activated CTLs designed to block its engagement with its two known inhibitory ligands, PD-L1 and PD-L2. The interruption of the PD-1-PD-L1/2 axis reverses adoptive T cell resistance and restores antimelanoma activity.

Ipilimumab treatment of melanoma: In two large randomized phase III clinical trials, ipilimumab improved both progression-free and overall survival in patients with unresectable stage III and stage IV melanoma compared to a glycoprotein 100 (gp100) peptide vaccine or chemotherapy.

In March 2011, ipilimumab was approved by the FDA for the treatment of unresectable stage III or IV melanoma administered intravenously at 3 mg/kg dose every 3 weeks for four doses.

Important facts about ipilimumab treatment of patients with metastatic melanoma:

Objective responses occur in between 10% and 16% patients while about 15% of patients develop stabilization of the disease resulting in long-term survival benefit in 20% to 25% of patients.

Objective responses occur in between 10% and 16% patients while about 15% of patients develop stabilization of the disease resulting in long-term survival benefit in 20% to 25% of patients.

Immune responses sometimes continued beyond 24 weeks converting nonresponsive disease to stable, stable disease to partial, and partial responses to complete responses.

Immune responses sometimes continued beyond 24 weeks converting nonresponsive disease to stable, stable disease to partial, and partial responses to complete responses.

Responses are seen in treatment naïve or previously treated patients including those with high-risk visceral metastasis and elevated serum LDH levels.

Responses are seen in treatment naïve or previously treated patients including those with high-risk visceral metastasis and elevated serum LDH levels.

The onset of response is slow and mediated by antigen-specific tumor infiltrating CD8+ CTLs consistent as the proposed mechanism.

The onset of response is slow and mediated by antigen-specific tumor infiltrating CD8+ CTLs consistent as the proposed mechanism.

Reinduction therapy with ipilimumab at the time of disease progression can result in further benefit in a proportion of patients (reinduction is not FDA approved).

Reinduction therapy with ipilimumab at the time of disease progression can result in further benefit in a proportion of patients (reinduction is not FDA approved).

The effect on overall survival is independent of age, sex, baseline serum LDH levels, metastatic stage, and previous treatment with IL-2 therapy.

The effect on overall survival is independent of age, sex, baseline serum LDH levels, metastatic stage, and previous treatment with IL-2 therapy.

The non-specific activation of pre-sensitized CTL against both tumor as well as host (shared antigens) resulted in loss of self-tolerance manifesting as serious irAEs in organs.

The non-specific activation of pre-sensitized CTL against both tumor as well as host (shared antigens) resulted in loss of self-tolerance manifesting as serious irAEs in organs.

Ipilimumab caused irAE in about 60% but grade 3/4 toxicity occurred in 20% to 30% patients.

Ipilimumab caused irAE in about 60% but grade 3/4 toxicity occurred in 20% to 30% patients.

Common irAEs involve skin, gastrointestinal tract, liver, and endocrine organs although careful symptom evaluation is important to detect other organ involvement.

Common irAEs involve skin, gastrointestinal tract, liver, and endocrine organs although careful symptom evaluation is important to detect other organ involvement.

Skin irAEs manifest as rashes and are first to appear after 3 to 4 weeks of treatment followed by colitis, liver (hepatitis), and endocrine organ involvement in that order.

Skin irAEs manifest as rashes and are first to appear after 3 to 4 weeks of treatment followed by colitis, liver (hepatitis), and endocrine organ involvement in that order.

Colitis symptoms should be distinguished from diarrhea by the presence of fever, abdominal cramps, distension and blood in stools as they can progress to intestinal obstruction or perforation.

Colitis symptoms should be distinguished from diarrhea by the presence of fever, abdominal cramps, distension and blood in stools as they can progress to intestinal obstruction or perforation.

Patient education about toxicity is critical, and prompt reporting of side effects improves outcomes from early initiation of immune suppressive treatment.

Patient education about toxicity is critical, and prompt reporting of side effects improves outcomes from early initiation of immune suppressive treatment.

Oral steroids at 1–2 mg/kg dose or its parenteral equivalent followed by gradual taper remain first line of treatment of irAE and best managed with a multidisciplinary team approach.

Oral steroids at 1–2 mg/kg dose or its parenteral equivalent followed by gradual taper remain first line of treatment of irAE and best managed with a multidisciplinary team approach.

Patients not responsive to steroids within 2 to 3 days may need to be administered higher level of immune suppression with agents such as anti–TNF-alpha antibody infliximab, antimetabolite mycophenylate mofetil, calcineurin inhibitor tacrolimus, and cyclosporine. Rarely, T-cell depleting antibody such as anti-thymocyte globulin has been used to achieve effective T cell suppression

Patients not responsive to steroids within 2 to 3 days may need to be administered higher level of immune suppression with agents such as anti–TNF-alpha antibody infliximab, antimetabolite mycophenylate mofetil, calcineurin inhibitor tacrolimus, and cyclosporine. Rarely, T-cell depleting antibody such as anti-thymocyte globulin has been used to achieve effective T cell suppression

The median time to resolution of severe irAEs of grade 2, 3, or 4 after initiation of immune-suppressive therapy is about 6.3 weeks and sometimes longer.

The median time to resolution of severe irAEs of grade 2, 3, or 4 after initiation of immune-suppressive therapy is about 6.3 weeks and sometimes longer.

Anti PD-1 treatment of metastatic melanoma: Phase I/II and randomized phase III studies of anti PD-1 agents Pembrolizumab and Nivolumab in treatment naïve and previously treated patients reported response rates between 52% to 38%, respectively.

Responses were seen in those with high risk features such as visceral metastasis (stage M1c), elevated LDH, and those with history of brain metastasis.

Responses were seen in those with high risk features such as visceral metastasis (stage M1c), elevated LDH, and those with history of brain metastasis.

The effect on overall survival is independent of age, sex, baseline LDH levels, stage, and previous treatment with ipilimumab therapy.

The effect on overall survival is independent of age, sex, baseline LDH levels, stage, and previous treatment with ipilimumab therapy.

Responses were durable even after stopping treatment leading to progression-free and overall survival.

Responses were durable even after stopping treatment leading to progression-free and overall survival.

Common irAE included skin rashes, fatigue, diarrhea, and pruritus while serious grade 3/4 toxicity in 5% to 15% patients was lower than seen with ipilimumab treatment (20% to 30%).

Common irAE included skin rashes, fatigue, diarrhea, and pruritus while serious grade 3/4 toxicity in 5% to 15% patients was lower than seen with ipilimumab treatment (20% to 30%).

Unusual irAE included autoimmune pneumonitis (presenting as cough, shortness of breath, and even fatal respiratory failure) and endocrine toxicity that appeared higher than with anti CTLA-4 antibody. Unusual irAEs included diabetes mellitus, nephritis besides others.

Unusual irAE included autoimmune pneumonitis (presenting as cough, shortness of breath, and even fatal respiratory failure) and endocrine toxicity that appeared higher than with anti CTLA-4 antibody. Unusual irAEs included diabetes mellitus, nephritis besides others.

Management principle of irAEs of anti PD-1 are same as that of ipilimumab (see above).

Management principle of irAEs of anti PD-1 are same as that of ipilimumab (see above).

Combined Immune Checkpoint Inhibition and Metastatic Melanoma: Principles

Hypothesis: Since CTLA-4 and PD-1 are two nonredundant inhibitory pathways affecting activated CTL, their combined inhibition might result in superior antimelanoma response.

Proof of this hypothesis obtained in preclinical models was confirmed in humans.

Proof of this hypothesis obtained in preclinical models was confirmed in humans.

Phase I/II as well as randomized phase III studies showed superior clinical benefit of iIpilimumab + nivolumab compared to single agent nivolumab or ipilimumab. The response rates were higher including complete responses of 11% to 22% and progression-free survival reached highest ever compared to single agents (11.5 vs. 6.9 vs. 2.9 months, respectively).

Phase I/II as well as randomized phase III studies showed superior clinical benefit of iIpilimumab + nivolumab compared to single agent nivolumab or ipilimumab. The response rates were higher including complete responses of 11% to 22% and progression-free survival reached highest ever compared to single agents (11.5 vs. 6.9 vs. 2.9 months, respectively).

Onset of responses was earlier and the majority of responses were deep (more than 80% tumor reduction) and durable although follow-up studies await its impact on overall survival.

Onset of responses was earlier and the majority of responses were deep (more than 80% tumor reduction) and durable although follow-up studies await its impact on overall survival.

The adverse prognostic effects of elevated LDH and negative PD-L1 expression affecting single agent ipilimumab or nivolumab treatment were not seen with the combination.

The adverse prognostic effects of elevated LDH and negative PD-L1 expression affecting single agent ipilimumab or nivolumab treatment were not seen with the combination.

Serious irAE were much higher with ipilimumab + nivolumab versus ipilimumab (54% vs.24%).

Serious irAE were much higher with ipilimumab + nivolumab versus ipilimumab (54% vs.24%).

irAE led to discontinuation of treatment in 36.4% patients receiving ipilimumab + nivolumab.

irAE led to discontinuation of treatment in 36.4% patients receiving ipilimumab + nivolumab.

The combined use of ipilimumab and nivolumab was approved by the FDA for the treatment of immune checkpoint inhibitor naïve unresectable stage III or IV melanoma.

The combined use of ipilimumab and nivolumab was approved by the FDA for the treatment of immune checkpoint inhibitor naïve unresectable stage III or IV melanoma.

The choice between using monotherapy with a PD-1 inhibitor or combination anti-CTLA4 and PD-1 remains controversial. Data on PDL-1 staining of tumors suggest that patients with low staining (less than 1%) may benefit from combined blockade while those with high staining (>5%) may do well with monotherapy.

The choice between using monotherapy with a PD-1 inhibitor or combination anti-CTLA4 and PD-1 remains controversial. Data on PDL-1 staining of tumors suggest that patients with low staining (less than 1%) may benefit from combined blockade while those with high staining (>5%) may do well with monotherapy.

Oncolytic Therapy and Antimelanoma Immune Responses: Principles

Oncolytic therapy is intralesional injection of agents that may produce both, a local and a systemic response. They could be viral or nonviral based.

Oncolytic viruses are modified live viruses designed to selectively replicate in tumor cells after intratumoral administration leading to release of tumor antigens in the proximity of tumor and evoking regional and systemic anti melanoma immunity. The immune response is facilitated by insertion and expression of gene encoding human granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF), local production of which help recruit and activate antigen-presenting cells.

T–VEC is a first in class FDA-approved agent for intratumoral injection and contains a modified herpes simplex virus (HSV) type I through the deletion of two nonessential viral genes.

Functional deletion of herpes virus neurovirulence factor gene (ICP34.5) attenuates viral pathogenicity and enhances tumor-selective replication.

Functional deletion of herpes virus neurovirulence factor gene (ICP34.5) attenuates viral pathogenicity and enhances tumor-selective replication.

Deletion of the ICP47 gene helps to reduce virally mediated suppression of antigen presentation and increases the expression of the HSV US11 gene.

Deletion of the ICP47 gene helps to reduce virally mediated suppression of antigen presentation and increases the expression of the HSV US11 gene.

A multicenter, open-label study assigned eligible surgically unresectable stage IIIB, IIIC, or IV melanoma patients suitable for direct or ultrasound-guided injection of T-VEC (at least one cutaneous, subcutaneous, or nodal lesion or aggregation of lesions more than or equal to 10 mm in diameter) versus subcutaneous injection of recombinant GM-CSF at a dose of 125 microgram/M2 randomly at a two-to-one ratio every 3 weeks after the first dose and then every 2 weeks until tumor progression or occurrence of toxicity.

Overall response rate was 26.4% with T-VEC versus 5.7% with GM-CSF, with durable responses of at least six months duration seen in 16.3% and 2.1% in each arms, respectively.

Overall response rate was 26.4% with T-VEC versus 5.7% with GM-CSF, with durable responses of at least six months duration seen in 16.3% and 2.1% in each arms, respectively.

Unresectable and treatment naive IIIB, IIIC, and IV M1a patients experienced more benefit compared to previously treated patients or stage IV M1b or M1c patients.

Unresectable and treatment naive IIIB, IIIC, and IV M1a patients experienced more benefit compared to previously treated patients or stage IV M1b or M1c patients.

Systemic immune effects were seen in 15% uninjected measurable lesions in systemic visceral sites that shrunk by > or = 50% size.

Systemic immune effects were seen in 15% uninjected measurable lesions in systemic visceral sites that shrunk by > or = 50% size.

Side effects of T-VEC were minor and included chills, fever, injection-site pain, nausea, influenza-like illness and fatigue. Vitiligo was reported in 5% of patients.

Side effects of T-VEC were minor and included chills, fever, injection-site pain, nausea, influenza-like illness and fatigue. Vitiligo was reported in 5% of patients.

Grade 3/4 irAE were seen respectively in 11% and 5% patients after TVEC and GM-CSF.

Grade 3/4 irAE were seen respectively in 11% and 5% patients after TVEC and GM-CSF.

A pattern of pseudo progression seen in some responding patients suggested continued treatment in clinically stable patients even if lesions appeared to grow or new lesions appeared.

A pattern of pseudo progression seen in some responding patients suggested continued treatment in clinically stable patients even if lesions appeared to grow or new lesions appeared.

Vitiligo and increased numbers of MART-1 specific T cells as well as decreased CD4+ and CD8+ FoxP3+ regulatory T cells in injected lesions suggested systemic antitumor immunity.

Vitiligo and increased numbers of MART-1 specific T cells as well as decreased CD4+ and CD8+ FoxP3+ regulatory T cells in injected lesions suggested systemic antitumor immunity.

Several other oncolytic agents are in clinical trials at this time both as monotherapy and in combination with checkpoint inhibitors.

Several other oncolytic agents are in clinical trials at this time both as monotherapy and in combination with checkpoint inhibitors.

Adaptive Cell Therapy of Metastatic Melanoma: Principles

Adaptive cell therapy refers to boosting antitumor immunity by transfer of autologous melanoma specific T cells obtained from the tumor (tumor infiltrating lymphocytes) or peripheral blood, back to the patient after their expansion ex vivo to large numbers. Conditioning regimens help provide space and growth factors for survival of the infused T cells. This treatment is based on the following fundamental facts:

In animal systems tumors can be controlled with adoptively transferred syngeneic T cells.

In animal systems tumors can be controlled with adoptively transferred syngeneic T cells.

T cells capable of recognizing autologous tumors in humans exist and they can be activated and expanded ex vivo, as well as engineered to express a set of highly avid T cell receptors for targeting tumor expressed epitopes displayed canonically on their MHC molecules.

T cells capable of recognizing autologous tumors in humans exist and they can be activated and expanded ex vivo, as well as engineered to express a set of highly avid T cell receptors for targeting tumor expressed epitopes displayed canonically on their MHC molecules.

Pioneered at the National Cancer Institute, response rates of as high as 50% were seen with this treatment modality with durable responses in subset of patients refractory to other treatments.

Targeted Therapy of Melanoma: Principles

Targeted therapy of melanoma is based upon a better understanding of functional cellular genetic machinery critical for transducing signals of cellular growth from outside of the cells to the nucleus leading to the transcription of key genes important for maintaining cellular homeostasis through control of proliferation, differentiation, and cell death.

The mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway is an important signaling cascade containing Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK proteins.

The mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway is an important signaling cascade containing Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK proteins.

B-Raf is a serine/threonine kinase occupying a central place in the MAPK pathway that harbors activating mutations in 50% to 60% of cutaneous melanomas conferring RAS independent proliferation and survival of melanoma cells.

B-Raf is a serine/threonine kinase occupying a central place in the MAPK pathway that harbors activating mutations in 50% to 60% of cutaneous melanomas conferring RAS independent proliferation and survival of melanoma cells.

Molecular identity of BRAF mutations led to its targeted inhibition through the design of small inhibitory molecules.

Molecular identity of BRAF mutations led to its targeted inhibition through the design of small inhibitory molecules.

About 90% of mutations in BRAF result in the substitution of glutamic acid for valine at codon 600 (BRAF V600E). Other BRAF mutations include V600K and V600D/V600R variants.

About 90% of mutations in BRAF result in the substitution of glutamic acid for valine at codon 600 (BRAF V600E). Other BRAF mutations include V600K and V600D/V600R variants.

Vemurafenib (first-in-class) and Dabrafenib are two FDA-approved reversible oral small molecule BRAF kinase inhibitors that selectively target cells harboring BRAF mutation. The resulting tumor cell death and inhibition of growth translated into survival in patients.

Vemurafenib (first-in-class) and Dabrafenib are two FDA-approved reversible oral small molecule BRAF kinase inhibitors that selectively target cells harboring BRAF mutation. The resulting tumor cell death and inhibition of growth translated into survival in patients.

Results from randomized clinical trials showed high response rates of up to 55%, and tumor stabilization of 30% for a clinical benefit to 80% to 90% of metastatic melanoma patients resulting in improved progression-free and overall survival compared to dacarbazine treatment (Table 22.8).

Results from randomized clinical trials showed high response rates of up to 55%, and tumor stabilization of 30% for a clinical benefit to 80% to 90% of metastatic melanoma patients resulting in improved progression-free and overall survival compared to dacarbazine treatment (Table 22.8).

TABLE 22.8 FDA-approved Targeted Therapy of BRAF Mutant Melanoma and Their Clinical efficacy

Treatment | Complete remission | Partial remission | Stable disease | MPFS months | MOS months | 12 month Survival (%) | 24 month Survival (%) | 2 and 3 year survival rates |

Vemurafenib 960mg PO BID | 8% | 44% | 30% | 7.3 | 13.6 | 65% | 38% | NA |

Dabrafenib 150mg PO BID | 3% | 47% | 42% | 5.1 | 18.7 | 68% | NA | 42% |

Trametinib 2mg PO daily | 2% | 20% | 56% | 4.8 | 16.1 | NA | NA | NA |

Dabrafenib 150mg PO BID+ Trametinib 2mg PO daily | 13% | 51% | 26% | 11.4 | 25.1 | 74% | 50% | 51% |

Vemurafenib 960mg PO BID+ Cobimetinib | 16%% | 54% | 18% | 12.3 | 22.3 | 75% | 49% | NA |

The FDA-approved vemurafenib at a dose of 960 mg administered orally twice a day while dabrafenib is approved at a dose of 150 mg administered orally twice a day for metastatic melanoma.

Important facts about BRAF kinase inhibitor treatment of metastatic melanoma:

The survival benefit of vemurafenib and dabrafenib was observed in each pre-specified subgroup according to age, sex, performance status, tumor stage, serum levels of lactate dehydrogenase, and geographic region.

The survival benefit of vemurafenib and dabrafenib was observed in each pre-specified subgroup according to age, sex, performance status, tumor stage, serum levels of lactate dehydrogenase, and geographic region.

Patient compliance with medication is important to maintain continued inhibition of MAPK pathway in tumor cells to ensure continued clinical benefit to the patient.

Patient compliance with medication is important to maintain continued inhibition of MAPK pathway in tumor cells to ensure continued clinical benefit to the patient.