Robert Dean and Matt Kalaycio

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) is a common lymphoid malignancy, representing 10% of all lymphomas. The National Cancer Institute SEER registry estimates that approximately 8,500 patients will be diagnosed with HL in 2016 in the United States. Median age at the time of diagnosis is 39 years, with a peak incidence at age 20 to 35 years. The age-adjusted incidence rate of HL is 2.6 per 100,000 individuals per year. Unlike non-Hodgkin lymphoma, HL incidence has not increased over the past decades. The male to female ratio is 1.3:1.0. In the United States, it affects African Americans slightly less commonly than Caucasians.

ETIOLOGY AND RISK FACTORS

The cause of HL remains unknown.

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) has been postulated to play a role in the pathogenesis of some cases of classical HL (CHL) (particularly mixed cellularity and lymphocyte-depleted subtypes).

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) has been postulated to play a role in the pathogenesis of some cases of classical HL (CHL) (particularly mixed cellularity and lymphocyte-depleted subtypes).

Loss of immune surveillance in immunodeficiency states (e.g., HIV infection, allogeneic stem cell transplantation, and solid organ transplantation) may predispose to development of HL.

Loss of immune surveillance in immunodeficiency states (e.g., HIV infection, allogeneic stem cell transplantation, and solid organ transplantation) may predispose to development of HL.

Two-fold increased risk of HL is seen in smokers.

Two-fold increased risk of HL is seen in smokers.

Family history of classical HL increases the risk to develop disease by 3-fold to 9-fold. Identical twin sibling of a HL patient has a 99-fold higher risk of developing HL.

Family history of classical HL increases the risk to develop disease by 3-fold to 9-fold. Identical twin sibling of a HL patient has a 99-fold higher risk of developing HL.

PATHOLOGY

HL is a neoplastic disease of B-cell origin. Classical HL (CHL) is characterized by the presence of Reed-Sternberg (RS) cells and mononuclear variants, amidst an inflammatory background consisting of lymphocytes, eosinophils, monocytes, and histiocytes. Nodular lymphocyte predominant HL (NLPHL) is characterized by RS variants termed LP cells in a background of lymphocytes and histiocytes but without other inflammatory cells.

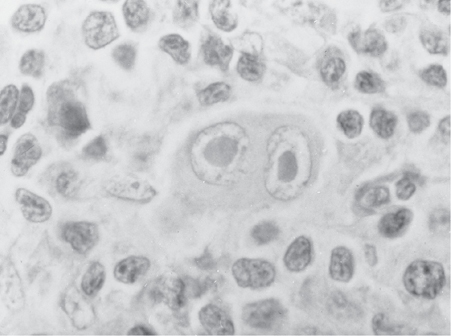

RS and LP cells are derived from follicular center B cells with clonally rearranged V heavy-chain genes. RS cells often exhibit symmetrical bilobed nuclei (owl’s eyes appearance) (Fig. 29.1). RS cells are positive for CD30 and CD15 and typically negative for CD20 and CD45, whereas LP cells express B-cell markers including CD20, CD45, and CD79a but are negative for CD30 and CD15.

FIGURE 29.1Diagnostic Reed-Sternberg (RS) cell, with Owl’s Eye nucleus, seen in classic types of Hodgkin lymphomas (mixed cellularity, nodular sclerosis, lymphocyte depletion).

Pathologic Classification

The World Health Organization (WHO) classification divides HL into two main types (Table 29.1):

TABLE 29.1Immunophenotypic Features of Hodgkin Lymphoma

| Classical Hodgkin Lymphoma | Nodular Lymphocyte Predominant Hodgkin Lymphoma |

CD45 | Negative | Positive |

CD30 | Positive | Negativea |

CD15 | Positive (80% of cases) | Negative |

CD20 | Variableb | Positive |

CD79a | Negativea | Positive |

EMA | Majority of cases positive | Negative |

aPositive in rare cases.

bPresent in up to 40% of the cases but usually expressed on minority of tumor cells with variable intensity.

Classical Hodgkin lymphoma (CHL)

Classical Hodgkin lymphoma (CHL)

•CHL is characterized by the presence of RS cells in an inflammatory background and is divided into four histologic subtypes, based mainly on the characteristics of the non-neoplastic reactive infiltrate.

•Nodular sclerosis HL

•Mixed cellularity HL

•Lymphocyte-rich HL

•Lymphocyte-depleted HL

NLPHL

NLPHL

•NLPHL lacks RS cells but is characterized by LP cells, which are sometimes referred to as popcorn cells.

Table 29.2 summarizes the clinical and pathologic features of the disease subtypes.

TABLE 29.2Classification of Hodgkin Lymphoma

Pathologic Type | Pathologic Features | Clinical Features |

Classical Hodgkin lymphoma | ||

Nodular sclerosis | Nodular growth pattern with broad bands of fibrosis | Most common type; and has a better prognosis. Common in resource-rich countries. Peak incidence at ages 15–34 y |

Mixed cellularity | Typical RS cells in a rich inflammatory background and fine reticular fibrosis; 70% are positive for Epstein-Barr virus | Second most common type; more common in patients with HIV infection and in developing countries. Median age is 38 y, with a male predominance |

Lymphocyte-rich | Scattered RS cells in a usually nodular background consisting of small lymphocytes | Common in elderly; has good prognosis |

Lymphocyte-depleted | Relative predominance of RS cells with depletion of background lymphocytes | Rare, often associated with HIV infection; has poor prognosis. Median age ranges from 30 to 37 y |

Nodular lymphocyte predominant | ||

No RS cells, but characterized by “popcorn” or LP cells (lobulated nucleus) | More common in adult males; often presents with early stage and has good prognosis, but late relapses are not uncommon. Peak incidence at ages 30–50 y | |

CLINICAL FEATURES

Lymphadenopathy: Most commonly above the diaphragm (cervical, axillary, or mediastinal). Enlarged nodes are non-tender, with a characteristic firm rubbery consistency. Lymph node pain may occasionally be precipitated by alcohol intake.

Lymphadenopathy: Most commonly above the diaphragm (cervical, axillary, or mediastinal). Enlarged nodes are non-tender, with a characteristic firm rubbery consistency. Lymph node pain may occasionally be precipitated by alcohol intake.

Chronic pruritus.

Chronic pruritus.

Most common extranodal sites of involvement are lung, bone marrow, liver, and bones.

Most common extranodal sites of involvement are lung, bone marrow, liver, and bones.

B symptoms.

B symptoms.

•Unexplained weight loss (>10% body weight over 6 months before diagnosis)

•Fever of >38°C, intermittent with 1- to 2-week cycles

•Drenching night sweats

Staging

The modified Ann Arbor staging of lymphoma is used to clinically stage HL (Table 29.3).

TABLE 29.3Cotswolds Modified Ann Arbor Staging of Lymphoma

Stage I | Single lymph node region, lymphoid structure (e.g., spleen, thymus, or Waldeyer ring), or a single extralymphatic site (IE) |

Stage II | Two or more lymph node regions on the same side of the diaphragm, or localized extranodal extension (contagious to a nodal site) plus one or more nodal regions (IIE) |

Stage III | Lymph node regions on both sides of the diaphragm. This may be accompanied by localized extranodal site (IIIE), or splenic involvement (IIIS), or both (IIIE+S) |

Stage IV | Diffuse or disseminated involvement of one or more extranodal organs or tissue beyond that designated E, with or without associated lymph node involvement |

Each stage is designated A or B, where B means presence and A means absence of B symptom | |

X: A mass >10 cm or a mediastinal mass larger than one-third of the thoracic diameter | |

E: Extranodal contiguous extension, which can be encompassed within an irradiation field appropriate for nodal disease of the same anatomic extent. More extensive extranodal disease is designated stage IV |

Diagnostic Evaluation

Excisional biopsy of an enlarged lymph node is strongly recommended for initial diagnosis. A core biopsy may be appropriate if adequate tissue can be obtained to avoid major surgery, but this may limit accurate classification among CHL subtypes. A fine-needle aspiration is not recommended for initial diagnosis.

Complete blood count (CBC), differential, and platelets.

Complete blood count (CBC), differential, and platelets.

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR): Adverse prognostic biomarker, if elevated.

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR): Adverse prognostic biomarker, if elevated.

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and albumin.

Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and albumin.

Liver function tests: If abnormal, may be associated with liver involvement.

Liver function tests: If abnormal, may be associated with liver involvement.

Alkaline phosphatase: May be nonspecifically high or associated with bone involvement.

Alkaline phosphatase: May be nonspecifically high or associated with bone involvement.

BUN, creatinine, electrolytes, and uric acid.

BUN, creatinine, electrolytes, and uric acid.

Pregnancy test: Women of childbearing age.

Pregnancy test: Women of childbearing age.

HIV testing in patients with risk factors for HIV.

HIV testing in patients with risk factors for HIV.

Chest radiograph (PA and lateral views) for assessment of mediastinal disease bulk.

Chest radiograph (PA and lateral views) for assessment of mediastinal disease bulk.

Diagnostic computerized tomography (CT) scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis are recommended for staging. CT scan of the neck may be needed for objective assessment of palpable lymphadenopathy, or in obese patients.

Diagnostic computerized tomography (CT) scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis are recommended for staging. CT scan of the neck may be needed for objective assessment of palpable lymphadenopathy, or in obese patients.

Positron emission tomography/computerized tomography (PET/CT) scan.

Positron emission tomography/computerized tomography (PET/CT) scan.

Unilateral Bone Marrow Biopsy and Aspiration

Recommended if PET/CT shows focal areas of skeletal uptake, or if unexplained cytopenias are present. Generally not needed in clinical stage III or IV.

Evaluation/Procedures for Specific Treatments and Counseling

MUGA scan or echocardiography to evaluate left ventricular ejection fraction before anthracycline treatment.

MUGA scan or echocardiography to evaluate left ventricular ejection fraction before anthracycline treatment.

Pulmonary function tests (including DLCO) are recommended prior to bleomycin-containing treatment.

Pulmonary function tests (including DLCO) are recommended prior to bleomycin-containing treatment.

Fertility counseling (to discuss sperm, ovarian tissue, and/or oocyte cryopreservation).

Fertility counseling (to discuss sperm, ovarian tissue, and/or oocyte cryopreservation).

Smoking cessation counseling.

Smoking cessation counseling.

MANAGEMENT

HL is sensitive to radiation and many chemotherapeutic agents. All patients, regardless of stage, should be treated with a curative intent. Cure rates are high (>80%), thus limiting long-term toxicities is a major consideration of treatment.

HL is sensitive to radiation and many chemotherapeutic agents. All patients, regardless of stage, should be treated with a curative intent. Cure rates are high (>80%), thus limiting long-term toxicities is a major consideration of treatment.

Early-stage disease may be treated with combined-modality chemotherapy and radiation treatment (RT), or chemotherapy alone.

Early-stage disease may be treated with combined-modality chemotherapy and radiation treatment (RT), or chemotherapy alone.

Advanced-stage disease is usually treated with chemotherapy alone.

Advanced-stage disease is usually treated with chemotherapy alone.

In advanced-stage disease, radiation consolidation can be considered for PET-positive areas following a full course of chemotherapy, particularly in patients who are poor candidates for intensive second-line therapy including autologous transplantation. Radiation consolidation should be omitted in patients with PET-negative residual masses. Based on pre-PET era studies, routine radiation consolidation in patients with bulky (≥10 cm or one-third the diameter of the chest on CXR) disease is widely practiced in North American centers; however, radiation consolidation may not be necessary in PET-negative bulky masses.

In advanced-stage disease, radiation consolidation can be considered for PET-positive areas following a full course of chemotherapy, particularly in patients who are poor candidates for intensive second-line therapy including autologous transplantation. Radiation consolidation should be omitted in patients with PET-negative residual masses. Based on pre-PET era studies, routine radiation consolidation in patients with bulky (≥10 cm or one-third the diameter of the chest on CXR) disease is widely practiced in North American centers; however, radiation consolidation may not be necessary in PET-negative bulky masses.

Principles of Chemotherapy

The standard regimen for HL in North America is ABVD (doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine) since it superseded MOPP (mechlorethamine, vincristine, procarbazine, prednisone) regimen in the large randomized trial of the Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB) in 1992 (Table 29.4). ABVD was associated with less myelosuppression and reduced risk of secondary leukemias and infertility compared to MOPP regimen. Prophylactic use of growth factors may increase the risk of pulmonary toxicity with ABVD and is therefore discouraged. Treatment delay and/or dose reduction due to uncomplicated leukopenia is not recommended, given that febrile neutropenia is uncommon with ABVD.

The standard regimen for HL in North America is ABVD (doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine) since it superseded MOPP (mechlorethamine, vincristine, procarbazine, prednisone) regimen in the large randomized trial of the Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB) in 1992 (Table 29.4). ABVD was associated with less myelosuppression and reduced risk of secondary leukemias and infertility compared to MOPP regimen. Prophylactic use of growth factors may increase the risk of pulmonary toxicity with ABVD and is therefore discouraged. Treatment delay and/or dose reduction due to uncomplicated leukopenia is not recommended, given that febrile neutropenia is uncommon with ABVD.

The German Hodgkin Lymphoma Study Group (GHSG) developed the dose-escalated BEACOPP regimen and showed it to be superior to COPP-ABVD and standard-dose BEACOPP in advanced HL. However the significant associated toxicities of dose-escalated BEACOPP (3% rate of treatment-related death, 2% to 3% rate of secondary leukemias, and nearly universal infertility) have precluded its widespread use in North America. Dose-escalated BEACOPP is not recommended for older HL patients (≥60 years).

The German Hodgkin Lymphoma Study Group (GHSG) developed the dose-escalated BEACOPP regimen and showed it to be superior to COPP-ABVD and standard-dose BEACOPP in advanced HL. However the significant associated toxicities of dose-escalated BEACOPP (3% rate of treatment-related death, 2% to 3% rate of secondary leukemias, and nearly universal infertility) have precluded its widespread use in North America. Dose-escalated BEACOPP is not recommended for older HL patients (≥60 years).

Stanford V is a dose-intense 12-week regimen. Involved field radiation to macroscopic splenic disease and all lymph nodes measuring ≥5 cm in size is an integral part of Stanford V. The cumulative doses of doxorubicin and bleomycin in Stanford V are less than those in ABVD, with potentially less risk for cardiac and pulmonary toxicity. In the three randomized prospective trials (from Italy, United Kingdom, and United States) compared to ABVD, Stanford V had inferior complete remission rates and was associated with more hematologic and neurologic toxicity.

Stanford V is a dose-intense 12-week regimen. Involved field radiation to macroscopic splenic disease and all lymph nodes measuring ≥5 cm in size is an integral part of Stanford V. The cumulative doses of doxorubicin and bleomycin in Stanford V are less than those in ABVD, with potentially less risk for cardiac and pulmonary toxicity. In the three randomized prospective trials (from Italy, United Kingdom, and United States) compared to ABVD, Stanford V had inferior complete remission rates and was associated with more hematologic and neurologic toxicity.

TABLE 29.4CALGB Study Comparing Different Regimens in Hodgkin Lymphoma

Regimen | Complete Response Rate (%) | 5-y Overall Survival Rate (%) |

MOPP | 67 | 66 |

ABVD | 82 | 73 |

Alternating MOPP/ABVD | 83 | 75 |

Chemotherapy regimens are described in Table 29.5.

TABLE 29.5Commonly Used Chemotherapy Regimens for Hodgkin Lymphoma

ABVD (every 28 d) | Doxorubicin 25 mg/m2/dose IV on days 1 and 15 |

Bleomycin 10 units/m2/dose IV on days 1 and 15 | |

Vinblastine 6 mg/m2/dose IV on days 1 and 15 | |

Dacarbazine (DTIC) 375 mg/m2/dose IV on days 1 and 15 | |

Dose-escalated BEACOPP (every 3 wk) | Bleomycin 10 international units/m2 IV on day 8 |

Etoposide (VP-16) 200 mg/m2 IV on days 1–3 | |

Doxorubicin (driamycin) 35 mg/m2 on day 1 | |

Cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan) 1,200 mg/m2 on day 1 | |

Vincristine 1.4 mg/m2 (max 2 mg) on day 8 | |

Procarbazine 100 mg/m2 PO on days 1–7 | |

Prednisone 40 mg/m2 PO on days 1–14 | |

Filgrastim (G-CSF) support is needed | |

Stanford V (every 4 wk) × three cycles (12 wk) | Nitrogen mustard 6 mg/m2 IV day 1 |

Doxorubicin (Adriamycin) 25 mg/m2 IV days1 and 15 | |

Vinblastine 6 mg/m2 IV days 1 and 15 | |

Vincristine 1.4 mg/m2 IV days 8 and 22 (maximum dose is 2 mg/dose). | |

Bleomycin 5 units/m2 IV days 8 and 22 | |

Etoposide (VP-16) 60 mg/m2 IV days 15 and 16 | |

Prednisone 40 mg PO qod × 10 wk, then taper by 10 mg every other day between weeks 10 and 12 | |

For patients older than 50, reduce vinblastine to 4 mg/m2 and vincristine to 1 mg/m2 in cycle 3 |

Principles of Radiotherapy

Radiation therapy for HL targets sites with radiographic disease (involved nodal or involved site). Historical approaches included involved areas alone (involved field), involved plus adjacent areas (extended field). Extended fields are either “mantle field” for the cervical, axillary, and mediastinal regions or “inverted Y field” for spleen, para-aortic, and pelvic regions. When inverted Y field radiation is given together with mantle field radiation, the combination is called total nodal radiation.

Radiation therapy for HL targets sites with radiographic disease (involved nodal or involved site). Historical approaches included involved areas alone (involved field), involved plus adjacent areas (extended field). Extended fields are either “mantle field” for the cervical, axillary, and mediastinal regions or “inverted Y field” for spleen, para-aortic, and pelvic regions. When inverted Y field radiation is given together with mantle field radiation, the combination is called total nodal radiation.

Dose of RT depends on the extent of the disease. In combined-modality therapy, RT is initiated ideally within 3 weeks of finishing chemotherapy.

Dose of RT depends on the extent of the disease. In combined-modality therapy, RT is initiated ideally within 3 weeks of finishing chemotherapy.

Treatment Response Evaluation

All patients (early and late stages) should receive interim restaging with PET/CT after two cycles of chemotherapy to evaluate the response to treatment. Restaging may be repeated after four cycles of chemotherapy to evaluate ongoing response, where applicable. Restaging should be repeated 2 months after the end of treatment if complete remission is not achieved in the interim assessment.

TREATMENT OF EARLY DISEASE (STAGES I AND II)

Early-stage CHL is stratified as favorable or unfavorable disease, and treatment varies accordingly. Unfavorable risk factors in this subset of patients vary somewhat among international clinical trial groups and are also summarized in guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN).

NCCN Unfavorable Prognostic Features for Early-Stage Disease (I and II)

Any of the following features:

|

Early-stage patients with unfavorable risk factors are best treated like advanced-stage (stage III/IV) disease. The remaining favorable-risk early-stage patients are managed as follows:

Favorable early-stage disease (by NCCN criteria): These patients may be treated with ABVD × two cycles followed by 20 Gy of involved nodal or involved site radiation. The cure rate of these patients is >90%.

|

|

TREATMENT OF ADVANCED DISEASE (STAGES III AND IV)

Aggressive histology (e.g., mixed cellularity or lymphocyte-depleted) is more common among patients with advanced CHL.

Unfavorable Prognostic Features for Advanced Stages (III and IV)

Hasenclever index (also called international prognostic score [IPS]) identifies seven adverse prognostic factors:

The 5-year overall survival decreases with higher IPS scores as follows: 0 factor (89%), 1 factor (90%), 2 factors (81%), 3 factors (78%), 4 factors (61%), and 5 or more factors (56%). |

The primary treatment of advanced-stage CHL is chemotherapy. ABVD is the standard of care in North American centers. The recommended initial treatment is six cycles of ABVD. In a phase III trial, initial treatment of advanced-stage CHL with brentuximab vedotin, doxorubicin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine was associated with improved progression-free survival, decreased pulmonary toxicity, and a trend toward lower overall mortality compared with ABVD. Brentuximab vedotin is not currently approved for primary treatment of CHL. Initial therapy with dose-escalated BEACOPP does not improve survival and increases the risk of subsequent myelodysplastic syndrome. Stanford V is also not recommended as initial therapy outside the setting of a clinical trial.

Treatment decisions are increasingly being made on the basis of PET scans obtained after chemotherapy has begun (Interim PET).

Evidence supports continuing ABVD if a PET or PET/CT scan is negative following two cycles of ABVD chemotherapy. Current data indicate that bleomycin may be discontinued in patients who achieve PET-negative response after two cycles of ABVD, continuing with AVD to complete six cycles with outcomes comparable to ABVD. This approach merits particular consideration in older adults, who are at higher risk for pulmonary toxicity and mortality with bleomycin-based therapy.

Evidence supports continuing ABVD if a PET or PET/CT scan is negative following two cycles of ABVD chemotherapy. Current data indicate that bleomycin may be discontinued in patients who achieve PET-negative response after two cycles of ABVD, continuing with AVD to complete six cycles with outcomes comparable to ABVD. This approach merits particular consideration in older adults, who are at higher risk for pulmonary toxicity and mortality with bleomycin-based therapy.

If a PET or PET/CT scan is positive according to the Deauville criteria, then evidence supports intensification of treatment with either 1) 6 cycles of dose-escalated BEACOPP or 2) ifosfamide-based rescue chemotherapy followed by high-dose chemotherapy with autologous hematopoietic cell rescue.

If a PET or PET/CT scan is positive according to the Deauville criteria, then evidence supports intensification of treatment with either 1) 6 cycles of dose-escalated BEACOPP or 2) ifosfamide-based rescue chemotherapy followed by high-dose chemotherapy with autologous hematopoietic cell rescue.

Nonbulky advanced-stage patients with a negative PET/CT at the end of chemotherapy do not need radiotherapy consolidation, particularly if interim restaging with PET or PET/CT scan was negative following 2 cycles of chemotherapy. RT can also be omitted in bulky disease patients with a negative CT or PET/CT after finishing chemotherapy, but this is an area of significant controversy. Bulky HL patients with a positive PET/CT after finishing chemotherapy can be offered 36 Gy of involved field RT.

TREATMENT OF NODULAR LYMPHOCYTE–PREDOMINANT HODGKIN LYMPHOMA

The NLPHL subtype represents 5% of HL. Unlike CHL, NLPHL is strongly CD20 positive and typically behaves like an indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma. While conventional HL approaches continue to be applied to NLPHL, as outlined below, there are compelling biologic and clinical arguments for a different therapeutic approach.

Conventional Treatment Approaches

Stages IA and IIA can be treated with 30 to 36 Gy of involved field radiation alone.

Stages IA and IIA can be treated with 30 to 36 Gy of involved field radiation alone.

Stages IA, IB, IIA, and IIB can be managed with a combined-modality approach (e.g., two to four cycles of ABVD or R-CHOP followed by involved field radiation).

Stages IA, IB, IIA, and IIB can be managed with a combined-modality approach (e.g., two to four cycles of ABVD or R-CHOP followed by involved field radiation).

Watchful waiting in patients with asymptomatic stage III/IV disease is reasonable. Patients with symptomatic advanced-stage disease are managed with systemic chemotherapy. The optimal chemotherapy regimen for NLPHL remains unknown. While ABVD is the “historical” standard, regimens designed for non-Hodgkin lymphomas such as CHOP, CVP, or dose-escalated EPOCH with rituximab (because of strong CD20 expression on LP Hodgkin cells) are also appropriate. Single-agent rituximab is also active in NLPHL and can be considered in patients with low bulk disease. It is important to recognize the “aggressive” presentations of NLPHL such as those with disseminated disease, including cases involving the bones and bone marrow and transformation to aggressive histologies. Such cases should be managed like aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphomas.

Watchful waiting in patients with asymptomatic stage III/IV disease is reasonable. Patients with symptomatic advanced-stage disease are managed with systemic chemotherapy. The optimal chemotherapy regimen for NLPHL remains unknown. While ABVD is the “historical” standard, regimens designed for non-Hodgkin lymphomas such as CHOP, CVP, or dose-escalated EPOCH with rituximab (because of strong CD20 expression on LP Hodgkin cells) are also appropriate. Single-agent rituximab is also active in NLPHL and can be considered in patients with low bulk disease. It is important to recognize the “aggressive” presentations of NLPHL such as those with disseminated disease, including cases involving the bones and bone marrow and transformation to aggressive histologies. Such cases should be managed like aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphomas.

FOLLOW-UP AFTER COMPLETION OF TREATMENT

The purpose of follow-up is the detection of disease relapse and late treatment-related complications.

Clinical evaluation with CBC, ESR, chemistry panel every 3 months for 2 years, then every 6 months for 5 years.

Clinical evaluation with CBC, ESR, chemistry panel every 3 months for 2 years, then every 6 months for 5 years.

There is no evidence to support routine radiographic surveillance following completion of treatment and confirmation of complete remission. Surveillance PET/CT imaging should be avoided because of frequent false-positive results.

There is no evidence to support routine radiographic surveillance following completion of treatment and confirmation of complete remission. Surveillance PET/CT imaging should be avoided because of frequent false-positive results.

Annual influenza vaccination.

Annual influenza vaccination.

Thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) annually if neck RT was given (risk of hypothyroidism).

Thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) annually if neck RT was given (risk of hypothyroidism).

Annual mammogram screening should start 8 to 10 years after RT or at age of 40 years, whichever is earlier, for patients who received RT above the diaphragm. Annual breast MRI is also recommended by the American Cancer Society in addition to mammogram in female patients who received radiation to chest or axillae between the ages 10 and 30 years. Breast self-exam should be encouraged.

Annual mammogram screening should start 8 to 10 years after RT or at age of 40 years, whichever is earlier, for patients who received RT above the diaphragm. Annual breast MRI is also recommended by the American Cancer Society in addition to mammogram in female patients who received radiation to chest or axillae between the ages 10 and 30 years. Breast self-exam should be encouraged.

LATE TREATMENT–RELATED COMPLICATIONS

Hypothyroidism and thyroid cancer can occur after neck or mediastinal RT.

Hypothyroidism and thyroid cancer can occur after neck or mediastinal RT.

Breast cancer can occur in females after chest or axillary RT. The risk is higher in patients who receive RT at younger age. It occurs after an average of 15 years after finishing treatment.

Breast cancer can occur in females after chest or axillary RT. The risk is higher in patients who receive RT at younger age. It occurs after an average of 15 years after finishing treatment.

Lung cancer: High risk is evident in patients who received RT to chest, received alkylating agents, and smoke cigarettes.

Lung cancer: High risk is evident in patients who received RT to chest, received alkylating agents, and smoke cigarettes.

Infertility risk is high after pelvic RT, MOPP regimen, BEACOPP regimen, and autologous transplantation.

Infertility risk is high after pelvic RT, MOPP regimen, BEACOPP regimen, and autologous transplantation.

Leukemia and myelodysplastic syndromes (especially with MOPP, BEACOPP, RT, and autologous transplantation).

Leukemia and myelodysplastic syndromes (especially with MOPP, BEACOPP, RT, and autologous transplantation).

Pulmonary toxicity after bleomycin treatment: Risk may be increased when G-CSF is used during treatment; hence G-CSF use is discouraged with ABVD. Supplemental oxygen should be used sparingly when needed, to minimize the risk of inducing pneumonitis.

Pulmonary toxicity after bleomycin treatment: Risk may be increased when G-CSF is used during treatment; hence G-CSF use is discouraged with ABVD. Supplemental oxygen should be used sparingly when needed, to minimize the risk of inducing pneumonitis.

Cardiac toxicity secondary to anthracycline is uncommon (total cumulative anthracycline dose is not prohibitive). The risk for premature coronary artery disease and cerebrovascular accidents is increased after mediastinal and cervical RT, respectively.

Cardiac toxicity secondary to anthracycline is uncommon (total cumulative anthracycline dose is not prohibitive). The risk for premature coronary artery disease and cerebrovascular accidents is increased after mediastinal and cervical RT, respectively.

Lhermitte sign: It is an infrequent complication that can occur 6 to 12 weeks after neck RT and resolves spontaneously. Patients feel electric-like shock sensation radiating down the back and extremities when neck is flexed. This sign is attributed to transient spinal cord demyelinization.

Lhermitte sign: It is an infrequent complication that can occur 6 to 12 weeks after neck RT and resolves spontaneously. Patients feel electric-like shock sensation radiating down the back and extremities when neck is flexed. This sign is attributed to transient spinal cord demyelinization.

Encapsulated organism infection (pneumococcal, meningococcal, and hemophilus) can occur in patients not vaccinated after splenic RT or splenectomy (rarely used now).

Encapsulated organism infection (pneumococcal, meningococcal, and hemophilus) can occur in patients not vaccinated after splenic RT or splenectomy (rarely used now).

TREATMENT OF RELAPSED HODGKIN LYMPHOMA

Relapsed disease must be confirmed by repeat biopsy.

Relapsed disease must be confirmed by repeat biopsy.

CHL:

CHL:

•In rare cases where RT was the first-line treatment, conventional chemotherapy (ABVD) at the time of relapse without autologous transplantation can be curative.

•If conventional chemotherapy (with or without RT) was the primary treatment, salvage chemotherapy such as ICE, DHAP, ESHAP, or GND (Table 29.6) followed by autologous transplantation is curative for about 50% of the patients.

•Brentuximab vedotin consists of an anti-CD30 chimeric monoclonal antibody; brentuximab, linked to the antimitotic agent monomethyl auristatin E (MMAE). The antibody portion of the drug attaches to CD30 on the surface of HL cells, delivering MMAE which exerts anti-HL activity. In patients with relapsed or refractory Hodgkin lymphoma after autologous transplant, brentuximab vedotin induces remission in 75% with estimated 3-year overall survival and progression-free survival rates of 73% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 57%, 88%) and 58% (95% CI: 41%, 76%), respectively.

•For brentuximab naïve HL patients, brentuximab vedotin added as maintenance therapy following autologous stem cell transplant improves progression-free survival compared to placebo, particularly in high-risk HL patients who do not achieve complete remission with rescue chemotherapy before autologous stem cell transplant.

•In patients with relapsed and refractory HL, the PD-1 inhibitor nivolumab induced remission in 87% resulting in a progression-free survival of 86% with 6 months of follow-up. Similarly, the PD-1 inhibitor pembrolizumab induced responses in 69% of patients with previously treated HL, with 63.4% progression-free survival at 9 months of follow-up.

•A small proportion of heavily pretreated, but otherwise healthy HL patients relapsing after an autologous transplant can be cured with an allogeneic stem cell transplant with better results obtained in those achieving remission first.

•NLPHL: Relapsed disease is best approached as an indolent lymphoma. Reasonable options include observation, rituximab alone or with chemotherapy, and/or RT.

TABLE 29.6Salvage Chemotherapy Regimen for Hodgkin Lymphoma

ESHAP (etoposide, methylprednisolone, high-dose cytarabine, and cisplatin) |

ICE (ifosfamide, carboplatin, and etoposide) |

DHAP (dexamethasone, high-dose cytarabine, and cisplatin) |

GND (gemcitabine, vinorelbine, and liposomal doxorubicin) |

GCP (gemcitabine, cisplatin, and methylprednisolone) |

Palliative Treatment

Sequential single-agent chemotherapy such as gemcitabine, vinblastine, bendamustine, or lenalidomide.

Sequential single-agent chemotherapy such as gemcitabine, vinblastine, bendamustine, or lenalidomide.

RT can be used to relieve pain or pressure symptoms of bulky masses.

RT can be used to relieve pain or pressure symptoms of bulky masses.

Investigational treatment is encouraged through enrollment in clinical trials.

Investigational treatment is encouraged through enrollment in clinical trials.

Future Directions

Phase III studies are underway or planned to combine standard chemotherapy with novel agents such as brentuximab vedotin and checkpoint inhibitors like nivolumab in the first-line setting to improve patient outcomes.

Phase III studies are underway or planned to combine standard chemotherapy with novel agents such as brentuximab vedotin and checkpoint inhibitors like nivolumab in the first-line setting to improve patient outcomes.

Suggested Readings

1.Aleman BM, Raemaekers JM, Tirelli U, et al. Involved-field radiotherapy for advanced Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2396–2406.

2.Ansell SM, Lesokhin AM, Borrello I, et al. PD-1 blockade with nivolumab in relapsed or refractory Hodgkin's lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:311–319.

3.Bonadonna G, Bonfante V, Viviani S, et al. ABVD plus subtotal nodal versus involved-field radiotherapy in early-stage Hodgkin’s disease: long-term results. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2835–2841.

4.Canellos GP, Anderson JR, Propert KJ, et al. Chemotherapy of advanced Hodgkin’s disease with MOPP, ABVD, or MOPP alternating with ABVD. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:1478–1484.

5.Chen R, Zinzani PL, Fanale MA, et al. Phase II study of the efficacy and safety of pembrolizumab for relapsed/refractory classic Hodgkin lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:2125–2132.

6.Chisesi T, Bellei M, Luminari S, et al. Long-term follow-up analysis of HD9601 trial comparing ABVD versus Stanford V versus MOPP/EBV/CAD in patients with newly diagnosed advanced-stage Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a study from the Intergruppo Italiano Linfomi. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4227–4233.

7.Connors JM, Klimo P, Adams G, et al. Treatment of advanced Hodgkin’s disease with chemotherapy—comparison of MOPP/ABV hybrid regimen with alternating courses of MOPP and ABVD: a report from the National Cancer Institute of Canada clinical trials group. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:1638–1645.

8.Diehl V, Franklin J, Pfreundschuh M, et al. Standard and increased-dose BEACOPP chemotherapy compared with COPP-ABVD for advanced Hodgkin’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2386–2395.

9.Eberle FC, Mani H, Jaffe ES. Histopathology of Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Cancer J. 2009;15(2):129–137.

10.Eich HT, Diehl V, Görgen H, et al. Intensified chemotherapy and dose-reduced involved-field radiotherapy in patients with early unfavorable Hodgkin’s lymphoma: final analysis of the German Hodgkin Study Group HD11 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4199–4206.

11.Engert A, Plütschow A, Eich HT, et al. Reduced treatment intensity in patients with early-stage Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:640–652.

12.Fabian CJ, Mansfield CM, Dahlberg S, et al. Low-dose involved field radiation after chemotherapy in advanced Hodgkin disease. A Southwest Oncology Group randomized study. Ann Intern Med. 1994;120:903–912.

13.Ferme C, Eghbali H, Meerwaldt JH, et al. Chemotherapy plus involved-field radiation in early-stage Hodgkin’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1916–1927.

14.Gopal AK, Chen R, Smith SE, et al. Durable remissions in a pivotal phase 2 study of brentuximab vedotin in relapsed or refractory Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2015 125:1236–1243.

15.Harris NL. Hodgkin’s disease: classification and differential diagnosis. Mod Pathol. 1999;12:159–175.

16.Hasenclever D, Diehl V. A prognostic score for advanced Hodgkin’s disease. International Prognostic Factors Project on Advanced Hodgkin’s Disease. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1506–1514.

17.Hoskin PJ, Lowry L, Horwich A, et al. Randomized comparison of the stanford V regimen and ABVD in the treatment of advanced Hodgkin’s lymphoma: United Kingdom National Cancer Research Institute Lymphoma Group Study ISRCTN 64141244. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5390–5396.

18.Kobe C, Dietlein M, Franklin J, et al. Positron emission tomography has a high negative predictive value for progression or early relapse for patients with residual disease after first-line chemotherapy in advanced-stage Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2008;112:3989–3994.

19.Johnson P, Federico M, Kirkwood A, et al. Adapted treatment guided by interim PET/CT scan in advanced Hodgkin’s Lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2016; 374: 2420–2429.

20.Lister TA, Crowther D, Sutcliffe SB, et al. Report of a committee convened to discuss the evaluation and staging of patients with Hodgkin’s disease: Cotswolds meeting. J Clin Oncol. 1989;7:1630–1636.

21.Meyer RM, Gospodarowicz MK, Connors JM, et al. ABVD alone versus radiation-based therapy in limited-stage Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:399–408.

22.Moskowitz CH, Nademanee A, Masszi T, et al. AETHERA Study Group. Brentuximab vedotin as consolidation therapy after autologous stem-cell transplantation in patients with Hodgkin's lymphoma at risk of relapse or progression (AETHERA): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2015;385:1853–1862.

23.Noordijk EM, Carde P, Dupouy N, et al. Combined-modality therapy for clinical stage I or II Hodgkin’s lymphoma: long-term results of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer H7 randomized controlled trials. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3128–3135.

24.Press OW, Li H, Schoder H, et al. US Intergroup trial of response-adapted therapy for stage III to IV Hodgkin lymphoma using early interim flurodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography imaging: Southwest Oncology Group S0816. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:2020–2026.

25.Savage KJ, Skinnider B, Al-Mansour M, et al. Treating limited-stage nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin lymphoma similarly to classical Hodgkin lymphoma with ABVD may improve outcome. Blood. 2011;118:4585–4590.

26.Schmitz N, Pfistner B, Sextro M, et al. Aggressive conventional chemotherapy compared with high-dose chemotherapy with autologous haemopoietic stem-cell transplantation for relapsed chemosensitive Hodgkin’s disease: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;359:2065–2071.

27.Steidl C, Lee T, Shah SP, et al. Tumor-associated macrophages and survival in classic Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:875–885.

28van Leeuwen FE, Klokman WJ, Hagenbeek A, et al. Second cancer risk following Hodgkin’s disease: a 20-year follow-up study. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12:312–325.

29.Viviani S, Zinzani PL, Rambaldi A, et al. ABVD versus BEACOPP for Hodgkin’s lymphoma when high-dose salvage is planned. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:203–212.

30.von Tresckow B, Plütschow A, Fuchs M, et al. Dose-intensification in early unfavorable Hodgkin’s lymphoma: final analysis of the German Hodgkin study group HD14 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:907–913.

31.Younes A, Gopal AK, Smith SE, et al. Results of a pivotal phase II study of brentuximab vedotin for patients with relapsed or refractory Hodgkin’s lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2183–2189.

32.Zinzani PL, Broccoli A, Gioia DM, et al. Interim Positron Emission Tomography Response-Adapted Therapy in Advanced-Stage Hodgkin Lymphoma: Final Results of the Phase II Part of the HD0801 Study. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:1376–1385.