Oncologic Emergencies and Paraneoplastic Syndromes 36

Meena Sadaps and James P. Stevenson

INTRODUCTION

While statistics show that the number of new cancer diagnoses in recent years has been climbing, the 5-year relative survival rate has now increased to 69%. This translates to the prevention of more than 1.7 million cancer deaths. These improvements in survival are a reflection of both patients being diagnosed at earlier stages and the introduction of novel agents into standard care. Because of these notable advances in oncology and the subsequent expanding population of cancer survivors, it is pertinent to gain familiarity with the diagnosis of and initial treatment for common oncological emergencies. Cancer patients are at increased risk of developing unique complications that can require emergent evaluation and treatment, often by frontline providers such as primary care and emergency department practitioners. The most common emergencies we encounter can be classified into metabolic, hematologic, cardiovascular, neurologic, infectious, and chemotherapy-related side effects. In this chapter, we will discuss each emergency in detail to facilitate their prompt recognition and management.

SUPERIOR VENA CAVA (SVC) SYNDROME

SVC syndrome occurs when blood flow through the thin-walled vessel becomes obstructed due to external compression by a tumor or internal occlusion by tumor invasion, fibrosis, or an intraluminal thrombus. This subsequently impairs venous drainage from the head, neck, upper extremities, and thorax. Decreased venous return to the heart, in turn, causes decreased cardiac output, increased venous congestion, and edema.

Etiology

The causes of SVC syndrome can be classified into two main categories: malignant (>90% of cases) and benign. The most common malignancies associated with SVC syndrome include lung cancer (primarily small cell and squamous cell), lymphoma (primarily non-Hodgkin’s including diffuse large cell lymphoma (DLCL) or lymphoblastic lymphoma), and metastatic disease (breast cancer being the most common). Other mediastinal tumors, such as thymomas and germ cell tumors, account for <2% of cases. The most common benign etiology is an intravascular device (indwelling central venous catheter or pacemaker), and in these cases the findings are predominantly unilateral. Other benign causes include retrosternal goiter, sarcoidosis, TB, and postradiation or idiopathic fibrosis.

Clinical Signs/Symptoms

The severity of symptoms (see Table 36.1) depends on the acuity of the obstruction/occlusion. Gradual progression allows for the development of collateral circulation in the azygous venous system and thus a more benign presentation. However, sudden obstruction is a true emergency that can lead to airway compromise, increased intracranial pressure, and cerebral edema.

Common symptoms include dyspnea (63%) and facial swelling/sensation of head fullness (50%). Cough, chest pain, and dysphagia are less frequently encountered. Characteristic physical exam findings include venous distention of neck (66%), venous distention of chest wall (54%), and facial edema (46%). Other exam findings may include cyanosis, arm swelling, facial plethora, and edema of arms. Symptoms are generally exacerbated by bending forward, stooping, or lying down.

TABLE 36.1 Clinical Presentation of SVC Syndrome

Dyspnea | 63% | Arm swelling | 18% |

Facial plethora | 50% | Chest pain | 15% |

Cough | 24% | Dysphagia | 9% |

Diagnosis

Although SVC syndrome is a clinical diagnosis, imaging studies may be obtained for further confirmation. Common abnormalities seen on CXR include superior mediastinal widening and pleural effusion. CT scan +/– venography, however, remains the most useful study for imaging the mediastinum, through identification of the site of obstruction, and, if warranted, to guide percutaneous biopsy. More invasive methods such as bronchoscopy, thoracotomy, and mediastinoscopy represent alternative methods to obtain diagnostic tissue if needed in these patients.

Treatment

The treatment and prognosis of SVC syndrome is driven by the underlying pathological process, and its management has shifted over the years from empiric radiotherapy to a more methodological and individualized approach. It has been shown that radiation prior to obtaining tissue diagnosis impedes accurate interpretation of the biopsy sample in >50% of cases. Exceptions to this rule, however, may include those with impending airway obstruction and/or a severe increase in intracranial pressure.

Symptomatic treatment with supplemental oxygen, diuretics, bedrest with head of bed elevation (>45 degrees), and corticosteroids can help provide initial relief. Once a histologic diagnosis has been made, treatment should be tailored accordingly. Chemotherapy alone or in combination with radiotherapy is effective in patients with SCLC. In patients with recurrent disease, it has actually been shown that additional chemotherapy +/– radiotherapy is still likely to provide further alleviation.

Radiotherapy or chemotherapy can also be used in patients with NSCLC; however, the percentage of patients who have been reported to have experienced relief were less than that of the SCLC population. The obstruction was also found to recur in approximately 20% of patients. Thus, the general recommendation for these patients consists primarily of radiation therapy, endovascular stenting, or a combination of both modalities. Some studies have shown that the presence of SVCS in patients with NSCLC foreshadows a shorter median survival of only 6 months as compared to 9 months in those without.

No treatment modality (chemo, chemo + XRT, XRT alone) has proven superior in the treatment for NHL. Relapse, however, remains common in this population and median survival has been approximated at 21 months.

When the goals of therapy are palliative or when urgent intervention is required (significant cerebral edema, laryngeal edema with stridor, or significant hemodynamic compromise), direct opening of the occlusion by endovascular stenting, angioplasty, and/or possible thrombolysis should be considered. Complete occlusion of the SVC is not a contraindication to stent placement.

If SVC syndrome is detected early in patients with an indwelling venous catheter, fibrinolytic therapy can be used without removal of the catheter. Otherwise, these patients should have the catheter removed and be placed on anticoagulation to prevent embolization. The role for SVC bypass surgery in patients with SVC syndrome secondary to other benign causes (e.g., mediastinal granuloma, fibrosing mediastinitis) has been one of great debate. While the overall good prognosis of these patients sways physicians away from surgical methods, many have advocated surgical consideration in patients where the syndrome develops suddenly or progresses/persists after 6 to 12 months of observation.

INCREASED INTRACRANIAL PRESSURE

The contents of our skull and dura can be divided into three main compartments: brain parenchyma (which occupies a volume of approximately 1.4 L), spinal fluid (52 to 160 ml), and blood (150 ml). An increase in any of these three compartments, as per the Monro-Kellie hypothesis, will occur at the expense of the remaining two. In addition, intracranial compliance has been noted to decrease with rising pressure, thus causing further compromise in cerebral perfusion. The normal range of ICP has been reported to be 5 to 15 mm Hg.

Etiology

In cancer patients, volume changes in brain parenchyma can be the result of primary or secondary brain tumors +/– intratumoral hemorrhage, vasogenic (peritumoral) or cytotoxic (in the setting of cytotoxic chemotherapy) edema, extra-axial mass lesions (dural tumors, infection, or hemorrhage), or indirect neurologic complications. Brain metastases are, in fact, the most common cause of increased ICP in this population. Lung cancer and melanoma, specifically, are most commonly associated with central nervous system (CNS) metastasis.

An imbalance between cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) production and reabsorption may also contribute to increased intracranial pressure (ICP). Mass lesions located at or near “bottleneck regions” (foramen of Monro, cerebral aqueduct, medullary foramina, basilar subarachnoid cisterns) cause obstruction. Some examples of primary brain tumors that favor these locations include subependymal giant cell astrocytoma, lymphoma, choroid plexus papilloma, ependymoma, and meningioma. Carcinomatosis and meningitis impede CSF reabsorption at the arachnoid granulations. Fibrosis of arachnoid granulations can be seen in patients that have received whole-brain or less commonly, partial-brain irradiation. Retinoic acid, an agent used for the treatment of promyelocytic leukemia, has also been associated with decreased CSF reabsorption. Increased production of CSF, on the other hand, is a rare cause of increased ICP. It can sometimes be seen in patients with choroid plexus papilloma, especially if the disease is multifocal in nature.

The third and last compartment within the skull is blood. Cerebral perfusion pressures are normally maintained over a wide range (50 to 160 mmHg), however, passive increases in ICP are seen when this autoregulatory mechanism fails. Venous outflow obstruction can be thrombotic or non-thrombotic. Patients receiving L-asparaginase therapy are at increased risk of developing dural venous sinus thrombosis. Nonthrombotic causes may include dural mass lesions such as meningioma, metastases from breast or prostate cancer, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, Ewing sarcoma, plasmacytoma, or neuroblastoma.

Intrathoracic pressure changes reflect on ICP as well, as demonstrated by coughing, sneezing, and straining. While these minimal fluctuations may not seem significant alone, patients with decreased compliance may experience transient decompensation.

Clinical Signs/Symptoms

The presentation of elevated ICP largely depends on the acuity of the underlying cause, with rapid progression often indicating hemorrhage. Slow, progressive changes may be accompanied by little to no symptoms, whereas dynamic changes can cause clinical deterioration. The Cushing response details the body’s response to a rise in intracranial pressures. First, the systolic blood pressure rises. In response, pulse pressure widens and bradycardia and irregular breathing ensue. Without correction, the heart rate will begin to rise, breathing will become shallow with episodes of apnea, and blood pressure will fall. With herniation and eventual cessation of brain stem activity, the patient goes into cardiac and respiratory arrest.

In the vast majority of cancer patients, the onset of symptoms occurs over days to weeks. Headache is the most common presenting symptom. Due to decreased venous drainage while in the supine position, patients generally report that their pain is most severe in the morning. Common analgesics rarely provide relief, however, patients have been noted to experience immediate relief with emesis. Fundoscopic examination may be revealing, with absence of venous pulsations in the center of the optic disc being an early findings and papilledema with blurring of disc margins and/or small hemorrhages being a later finding. Elevated ICP in the setting of mass-effect can present with focal neurologic deficits based on the location of the mass. Patients with chronic disturbance of spinal fluid reabsorption can present with a triad of cognitive decline, incontinence, and ataxic gait. Hyponatremia may also be noted on laboratory testing as SIADH is a common metabolic complication seen with elevated ICP.

Diagnosis

While imaging is critical in the determination of the underlying etiology, thorough clinical history and physical examination are most pertinent for diagnosis of increased ICP. Lumbar puncture is used to directly measure CSF pressure; however, CT should be obtained prior in order to rule out mass lesions of the posterior fossa and/or compartmentalization, as these would be contraindications due to the risk of herniation. CT scan without contrast is generally the initial preferred imaging study as it can identify the presence of CSF obstruction, herniation, hemorrhage, or neoplastic/infectious mass lesions. MRI with gadolinium can further be used to differentiate between neoplastic, infectious, inflammatory, and ischemic process. Obstruction or infiltration of the dural venous sinuses is best visualized with magnetic resonance venography.

Treatment

Few patients present emergently, such as those with obstructive hydrocephalus, and in these cases immediate neurosurgical intervention will be necessary. In non-emergent cases, certain measures can be taken initially to help decrease intracranial pressure. These include elevation of the head of the bed above 30 degrees, antipyretic use when the patient is febrile, and maintenance of high-normal serum osmolality with osmotic diuresis as needed. The most commonly used hyperosmolar agent used is 20% to 25% mannitol solution given at 0.75 to 1 g/kg body weight followed by 0.25 to 0.5 g/kg body weight every 3 to 6 hours. While moderate to high dose dexamethasone (6 to 10 mg every 6 hours up to 100 mg/day) can be effective in patients with vasogenic edema, they should be avoided in patients suspected to have CNS lymphoma prior to tissue diagnosis. Steroids are known to induce lymphocytic apoptosis and can therefore obscure the diagnosis. The most rapid, but transient, method to decreasing ICP is mechanical hyperventilation with goal PCO2 25 to 30 mmHg.

In addition to symptomatic management in these patients, it is crucial to treat the underlying disease process, whether that includes surgical resection/decompression, systemic/intrathecal chemotherapy, and/or whole brain irradiation.

SPINAL CORD COMPRESSION

Spinal cord compression (SCC) is a true oncologic emergency as delays in diagnosis can cause severe, irreversible neurologic compromise, decline in functional status, and impaired quality of life. Spinal cord compression affects roughly 5% to 10% of all patients with cancer; an estimated 20,000 patients are diagnosed each year in the United States. The majority of cases result from spine metastases with extension into the epidural space. It is the second most frequent neurologic complication of cancer after brain metastases. The median overall survival of patients with spinal cord compression ranges from 3 to 16 months and most die of systemic tumor progression.

Etiology

Although all cancers capable of hematogenous spread can cause malignant spinal cord compression, the most common underlying cancer diagnoses associated with this complication are breast, prostate, lung, multiple myeloma, and lymphoma.

Hematogenous seeding of tumor to the vertebral bodies is the most common cause of spinal metastases, followed by direct extension and cerebrospinal fluid spread. Nearly 66% of spinal cord compression involves the thoracic spine and 20% involves the lumbar spine. Colon and prostate malignancies more commonly spread to the lumbosacral spine while lung and breast cancers frequently affect the thoracic spine. The cervical and sacral spines are rarely involved (less than 10% for each region).

The median time interval between cancer diagnosis and manifestation of SCC is approximately 6 to 12.5 months. Malignant spinal cord compression is rarely the primary manifestation of a malignancy.

Clinical Signs/Symptoms

The most common presenting symptom of malignant spinal cord compression is back pain. The complaint of back pain in a cancer patient, specifically with a malignancy that frequently seeds the spine, should be considered metastatic in origin until proven otherwise. The characteristic back pain that is described is often worst in the recumbent position, thus resulting in maximal intensity upon morning awakening. As time progresses, the back pain can become radicular in nature.

Other symptoms of malignant SCC are primarily dependent on the region of the spine that is affected.

Cervical spine involvement generally presents with headache, arm/shoulder/neck pain, breathing difficulties, loss of sensation, and weakness/paralysis in the upper extremities. Thoracic and lumbosacral spine involvement can present with pain in the back or chest, loss of sensation below the level of tumor, increased sensation above the level of tumor, positive Babinski sign, bladder/bowel retention, and/or sexual dysfunction.

A thorough physical exam should be performed including percussion of the spinal column, evaluation for motor and sensory deficits including pinprick testing, straight-leg raise, and a rectal examination to assess sphincter tone.

The most important prognostic factor for regaining ambulatory function after treatment of SCC is pretreatment neurologic status, making the physical exam a vital component of overall prognosis. Generally speaking, the quicker the neurologic deficit evolves, the lower the chance of recovery after treatment.

Diagnosis

Despite the availability of diagnostic testing, there remains a lag between onset of symptoms and diagnosis (approximately 3 months). This delay can be primarily attributed to a delay in obtaining the diagnostic imaging by health-care professionals. As back pain is a common complaint and the differential remains broad, having a high clinical suspicion is crucial. Red flags for SCC should include pain in the thoracic spine, persistence of symptoms despite conservative measures, and exacerbation of pain in the supine position.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with contrast of the spine is the most sensitive diagnostic test. Its advantages include the ability to accurately identify the level of the metastatic lesion, define soft tissue from bone, and separate metastatic cord compression from other pathologic processes involving the axial skeleton, epi- or intradural space, and spinal cord. It avoids the need for lumbar or cervical puncture that is required with CT myelography and can be safely performed in most patients.

CT myelography after intrathecal injection of contrast was the study of choice in the pre-MRI era but is now used much less frequently. It remains useful, however, for patients in whom MRI is contraindicated.

If SCC is the initial presentation for a malignancy, a biopsy is mandatory prior to initiation of treatment.

Treatment

Primary goals of treatment include pain control, preservation/recovery of neurologic function, and prevention of complications secondary to tumor growth.

Treatment with corticosteroids should be initiated immediately when spinal cord compression is suspected. This begins with an initial loading dose of 10 mg IV dexamethasone followed by 4 mg IV dexamethasone every 6 hours afterwards. Corticosteroids facilitate pain management but also reduce swelling around the cord and may prevent additional spinal cord damage from decreased blood perfusion.

Immediate consultations to surgery and radiation oncology are required after diagnosis. Further therapy is then decided based on the clinical picture, availability of histologic diagnosis, spinal stability, and previous treatment. Patients with spinal instability, even in the absence of clinical signs/symptoms, should undergo surgery unless otherwise contraindicated.

At the time of diagnosis, 66% of patients receive radiation, 16% to 20% undergo surgical decompression, and the remainder are provided with comfort care measures. In a study of symptomatic patients with SCC with metastatic tumors other than lymphoma, debulking surgery followed by radiation resulted in four times longer duration of maintained ambulation after treatment and three times higher chance of regaining ambulation for non-ambulatory patients than radiation alone. Combined-modality approaches help to achieve better pain control and bladder continence. This can also reduce steroid and narcotic use.

Radiation therapy is the most commonly used treatment modality. It is typically applied in asymptomatic individuals or symptomatic patients who are poor surgical candidates. Patients with radiosensitive tumors (breast, lymphoma, myeloma, prostate cancer) have a higher chance of regaining/preserving motor function than those with less radiosensitive tumors (non-small cell lung cancer, melanoma, and renal cell carcinoma). Standard radiation doses consist of 3000 to 4000 cGy in 5 to 10 fractions. It can also be used for palliative purposes with one fraction of 8 Gy. Stereotactic radiation therapy is becoming a more frequent modality for spine metastases. It provides the ability to deliver a higher radiation dose without exceeding the tolerance of the spinal cord.

Systemic chemotherapy is most appropriate as a primary treatment modality only for patients with SCC caused by highly chemosensitive tumors such as Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma, small cell lung cancer, breast, and prostate cancers. It can also be used in those who are not candidates for radiation or surgery.

TUMOR LYSIS SYNDROME

Tumor lysis syndrome (TLS) refers to a constellation of metabolic imbalances that occurs when malignant cells rapidly undergo lysis and empty their intracellular contents into the bloodstream at a rate that far exceeds the kidney’s clearance capacity. The overwhelming release of nucleic acid products results in hyperuricemia, which can then contribute to crystallization and subsequent obstruction within the renal tubules. Hyperkalemia and hyperphosphatemia with secondary hypocalcemia can also be seen in these patients. Without appropriate time-sensitive treatment (see Table 36.2), TLS can lead to lactic acidosis, acute renal failure, and even death.

Etiology

While TLS is most commonly seen in patients with high-grade lymphomas (particularly Burkitt lymphoma) or acute leukemias, it can also be seen in those with kinetically active solid tumors and, at times, may even occur spontaneously. Factors that increase the risk of TLS include high baseline urate levels, large tumor burden (white blood cell count >50 x 109/L, high low-density lipoprotein, large tumor size), and chemo-sensitive disease. Generally speaking, many of the patients that develop TLS are patients that have recently started chemotherapy. TLS most commonly occurs within hours to 3 days following chemotherapy. Additional incidences, though fewer, have been reported following other treatment modalities including ionizing radiation, embolization, radiofrequency ablation, monoclonal antibody therapy, glucocorticoids, interferon, and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

Clinical Signs/Symptoms

The presentation of patients with TLS is fairly non-specific and depends on the electrolyte abnormalities that are present. Although symptoms may precede initiation of chemotherapy, they are most often noted within 12 to 72 hours after initiation of cytoreductive treatment. Hyperkalemia can manifest with arrhythmias, muscle cramps, weakness, paresthesia, nausea/vomiting, and diarrhea. Hyperphosphatemia and hyperuricemia contribute to acute renal failure, which is evidenced by decreased urine output (UOP) and/or volume overload. Hyperphosphatemia also leads to secondary hypocalcemia. Hypocalcemic signs include muscle twitches, cramps, carpopedal spasm, paresthesia, tetany, mental status changes, nephrocalcinosis and rarely, seizures.

TABLE 36.2Management of Electrolyte Abnormalities in TLS

Metabolic Derangement | Severity | Treatment |

Hyperkalemia | Moderate (≥6 mmol/L) and asymptomatic |

|

Severe (>7 mmol/L) and/or symptomatic | As above, plus any of the following:

| |

Hypocalcemia (≤7 mg/dL) | Asymptomatic | No treatment necessary |

Symptomatic |

| |

Hyperphosphatemia | Moderate (≥6.5 mg/dL) |

|

Severe |

| |

Hyperuricemia (≥8 mg/dL) | Low risk |

+/–Allopurinol 300 mg PO daily (100 mg/m2 every 8 hr) |

Intermediate risk | -IV normal saline 150–200 cc/hr -Allopurinol 300 mg PO daily (100 mg/m2 every 8 hr) +/-Rasburicase 0.15 mg/kg IV daily for 5–7 days | |

High risk |

+/–Dialysis |

Diagnosis

Of all the metabolic abnormalities seen with TLS, hyperkalemia poses the most immediate threat and is often the first sign of the disease. Hyperuricemia, on the other hand, is the most common lab abnormality noted in these patients. Additional labs may be notable for elevated phosphorus, elevated lactate dehydrogenase, and low calcium levels. Clinical and laboratory TLS is defined by the Cairo and Bishop classification and grading system. Laboratory TLS is diagnosed when levels of two or more serum values of urate, potassium, phosphate, or calcium are abnormal at presentation or if there is a 25% change within 3 days before or 7 days after the initiation of treatment. Clinical TLS is diagnosed when laboratory TLS is present and one or more of the following complications are present: renal insufficiency, cardiac arrhythmias/sudden death, and seizures. Laboratory TLS is either present or absent, whereas, clinical TLS is graded on a scale of 0 to 5 based on the severity of the clinical manifestation.

Treatment

Prevention is key in the management of TLS. Patients at low risk can be closely monitored while patients at intermediate or high risk should be treated prophylactically to reduce incidence of TLS. The recommended prophylactic treatment for intermediate risk patients is allopurinol (100 mg/m2 every 8 hours) for 2 to 3 days prior to administration of chemotherapy and continued for 3 to 7 days afterward until normalization of serum urate levels. Severe cutaneous adverse events have been reported with allopurinol in patients with inheritance of the HLA-B*58:01 allele; screening is advised in high risk patients (Han Chinese, Thai, Korean populations). Patients should also undergo aggressive hydration (in order to maintain urine output of atleast 100 cc/m2/hr) and be given oral phosphate binders. Metabolites should be vigilantly monitored in intervals of 3 to 4 hours after initiation of treatment.

Uric acid levels are generally not expected to decrease until 48 to 72 hours of treatment as the mechanism of allopurinol is through the inhibition of xanthine oxidase. The medication, therefore, only affects further uric acid synthesis and not pre-existing uric acid. Rasburicase can be considered in patients at intermediate or high risk of TLS and with pre-existing hyperuricemia (>= 7.5 mg/dl) and should be administered within four hours of presentation. This medication, in contrast, acts on the degradation of uric acid. There has only been one phase III clinical trial to compare allopurinol with rasburicase in adults. While rasburicase was proven superior in time to control serum uric acid levels, there was a lack of evidence to determine whether clinical outcomes were improved. At this time, the evidence remains stronger for rasburicase use in children with high-risk conditions than in adults, however, the medication has been approved for use in both populations, with the recommended dose of 0.2 mg/kg/day for 5 to 7 days. In patients at intermediate risk, a single dose of 0.15 mg/kg may be sufficient and can minimize cost. In a retrospective study utilizing patient data from over 400 U.S. hospitals from 2005 to 2009, it was noted that rasburicase administration compared to allopurinol was associated with a significant reduction in uric acid levels, ICU length of stay (LOS), overall LOS, overall cost. In patients receiving single dose rasburicase, it is recommended that they receive allopurinol following the rasburicase treatment. G6PD deficiency is a contraindication for rasburicase treatment because hydrogen peroxide can cause severe hemolysis; therefore patients should undergo screening prior to use.

In patients in whom allopurinol and rasburicase are not an option, febuxostat can be cautiously considered as an alternative. Febuxostat was compared with allopurinol in the FLORENCE trial. The decrease in mean serum urate levels observed with febuxostat did not translate to improvement in laboratory or clinical TLS following chemotherapy. In addition, the arm that received febuxostat was noted to have a higher incidence of liver dysfunction, nausea, joint pain, and rash.

Patients diagnosed with TLS require hospitalization for further monitoring and treatment. An ECG should be obtained in these patients to evaluate for serious arrhythmias and conduction abnormalities. Hyperkalemia can be treated with any combination of calcium gluconate, sodium bicarbonate, insulin with hypertonic dextrose, loop diuretics, and kayexalate (sodium polystyrene sulfonate). Patients may require hemodialysis depending on the severity of the hyperkalemia, renal dysfunction, and volume status. With the exception of hyperkalemia management, calcium administration is generally avoided as it can promote metastatic calcifications. Hyperphosphatemia is treated with phosphate binders (i.e. aluminum hydroxide) or hypertonic dextrose with insulin. As hypocalcemia resolves with management of the underlying hyperphosphatemia, treatment with calcium gluconate is only needed if the patient is symptomatic. Urine alkalinization is no longer common practice as there is a lack of data to demonstrate its efficacy and it poses the risk of calcium phosphate deposition in the kidneys, heart, and other organs.

HYPONATREMIA

Cancer patients may develop hyponatremia due to imbalances in water and sodium homeostasis. The reported incidence is 3.7%.

Etiology

The differential for hyponatremia is quite extensive, including pulmonary infections, intracranial lesions, recent radiation therapy, gastrointestinal (GI) losses, heart failure, hypothyroidism, diabetes, and offending medications. In cancer patients specifically, the leading causes remain dehydration, GI or renal losses, and syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone (SIADH). SIADH generally occurs as either a paraneoplastic syndrome or as a complication of chemotherapy. The excess production of antidiuretic hormone (ADH) may originate from the hypothalamus or be ectopic, arising from cancer cells. Ectopic ADH is most commonly associated with small cell lung cancer, indicating a poor prognosis. Other associated malignancies include head and neck carcinomas, hematological malignancies, and non-small cell lung cancer. Chemotherapy agents that can cause SIADH include cyclophosphamide, ifosfamide, vincristine, vinblastine, vinorelbine, bortezomib, carboplatin, and cisplatin.

Ectopic production of a peptide similar to ADH, known as atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP), has also been described in patients with small cell lung cancer (SCLC). ANP is released from atrial myocytes and works by increasing renal sodium excretion and possibly by suppressing an aldosterone response.

“Pseudohyponatremia” is a condition frequently seen in patients with multiple myeloma and hyperproteinemia as a way for the body to preserve electrical neutrality. Lastly, hyponatremia can also occur with cerebral salt wasting syndrome (CSWS) in patients with cerebral malignancies or metastases.

Clinical Signs/Symptoms

The clinical manifestations of hyponatremia largely depend on the severity. If the imbalance develops over a prolonged time period and/or the hyponatremia is not significant, patients may be asymptomatic. The most common symptoms reported in patients with mild hyponatremia have been nausea and weakness. Other symptoms may include anorexia, constipation, myalgia, polyuria, and polydipsia. With severe hyponatremia, patients may experience altered mentation, seizures, and even coma or death from the resultant cerebral edema and increased intracranial pressure. Physical exam findings, if present, may be notable for papilledema and hypoactive reflexes.

Diagnosis

Hyponatremia is defined as serum sodium level less than 130 mEq/L. The essential features for diagnosis of SIADH, in particular, include decreased effective osmolality, urine osmolality >100 mOsm/kg of water, clinical euvolemia, urine sodium >40 mmol/L in the setting of normal salt intake, normal thyroid and adrenal function, and no recent diuretic use. The major criteria for CSWS include the presence of a cerebral lesion and high urinary excretion of sodium and chloride in a patient with contraction of extracellular fluid volume.

Treatment

The initial step in the treatment of hyponatremia should be to determine the underlying cause. Any offending medications should immediately be stopped. The cornerstone of therapy consists of free water restriction (500 to 1000 ml per day) and furosemide. As a general rule, the rapidity of correction of serum sodium is determined by its acuity, so as to prevent patients from developing an osmotic demyelination syndrome. Patients with acute presentations are likely to be more symptomatic and can tolerate more rapid correction. For asymptomatic patients who developed hyponatremia over weeks with serum sodium less than 125 mmol/L, the goal should be to increase serum sodium by 0.5 to 2 mmol/L/hr. For symptomatic patients or patients with a serum sodium level below 115 mmol/L, sodium should be increased by 2 mmol/L/hr, with the initial use of hypertonic saline. If the hyponatremia does not improve or worsen after 72 to 96 hours of free water restriction, IV fluids, and lasix, plasma levels of AVP and ANP should be measured to evaluate for SIADH and SIANP. Patients with SIADH should be treated with demeclocycline 300 to 600 mg twice daily and ADH-receptor antagonists such as IV conivaptan or oral tolvaptan may also be considered. Patients with SIANP will continue to have worsening hyponatremia, despite free water restriction, if they do not increase their salt intake. Management of cerebral salt wasting includes aggressive fluid and electrolyte replacement as well as mineralocorticoid supplementation with fludrocortisone 100 to 400 mg/day.

HYPERCALCEMIA

Of all paraneoplastic syndromes, hypercalcemia is the most common, seen in 10% to 30% of cancer patients at some time during their disease. Severe hypercalcemia, especially if combined with elevated parathyroid hormone-related protein, indicates a poor prognosis. Survival is often less than 6 months following diagnosis of hypercalcemia.

Etiology

The etiology of hypercalcemia in cancer patients can be divided into two distinct groups: the first being a humoral paraneoplastic syndrome (most common cause of hypercalcemia in cancer patients) and second, the result of bone destruction. Humoral hypercalcemia is most frequently seen with malignancies of the breast, lung, kidney, and head and neck whereas hypercalcemia in the setting of osteolytic metastases is most frequently seen with multiple myeloma. In the latter group, tumor cells have been found to release local factors such as cytokines and growth factors that activate osteoclasts, either directly or indirectly via osteoblast-related up-regulation of osteoclast-activating factors (OAFs). In the former group, tumor cells release systemic factors that affect bone resorption and calcium reabsorption at the level of the kidney. Parathyroid hormone-related protein (PTHrP) is the most commonly secreted systemic factor, found in about 80% of hypercalcemic cancer patients. PTHrP further exacerbates hypercalcemia via its synergistic activity with local factors such as interleukin-1, interleukin-6, and tumor necrosis factor alpha. As a third mechanism, some lymphomas cause hypercalcemia by releasing 1,25 dihydroxy-vitamin D, which then promotes intestinal calcium absorption and bone resorption.

Clinical Signs/Symptoms

Patients will generally present with nonspecific findings such as nausea, vomiting, constipation, polyuria, dehydration, and/or confusion. These patients are also at high risk for bradycardia, arrhythmias, shortened QT interval, prolonged PR interval, and cardiac arrest.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of hypercalcemia is determined by measuring the serum ionized calcium level. If total serum calcium is obtained, it must be appropriately adjusted for albumin levels. Corrected calcium = measured total calcium + [0.8 x (4 – serum albumin concentration)]. A low chloride level should raise suspicion for malignancy-related hypercalcemia.

Treatment

Patients who are asymptomatic with calcium levels less than 13 mg/dl only require conservative management with hydration. Symptomatic patients with calcium levels greater than 13 mg/dl require hydration in addition to more aggressive treatment. Hemodialysis should be considered when calcium levels exceed 18 to 20 mg/dl and/or the patient develops neurological symptoms. Once adequate hydration has been attained, small doses of furosemide can be utilized to enhance calcium excretion. Bisphosphonates remain the most effective treatment for malignancy-related hypercalcemia, with zoledronate being the current best choice. Pamidronate may also be used. Normalization of serum calcium levels is achieved in 4 to 10 days and the effects last for about 4 to 6 weeks in 90% of patients. Bisphosphonates have a complex mechanism of action that ultimately leads to a decrease in bone resorption. As they have no effect on humorally mediated calcium reabsorption, they are less effective in patients with humoral-mediated hypercalcemia. Osteonecrosis of the jaw may be a potentially devastating adverse effect of bisphosphonate use, with myeloma patients at higher risk. Depending on the clinical urgency of bisphosphonate use, patients should undergo dental evaluation prior, if able, as poor dentition also places patients at increased risk.

Novel agents in the pipeline include osteoprotegerin (OPG), a decoy receptor that acts to inhibit bone resorption. The cytokine system of which OPG is a part of also consists of the receptor RANK and its ligand RANKL. When RANKL binds to RANK, osteoclast formation is increased and osteoclast apoptosis is inhibited. This process is counterbalanced by OPG. Denosumab is a monoclonal antibody with high affinity for RANKL and has been approved for treatment of hypercalcemia of malignancy refractory to bisphosphonate therapy as well as for treatment of bone metastases. In three randomized, phase III clinical trials, denosumab has proven to be superior than zoledronic acid by a median of 8.21 months for prevention of skeletal-related events in patients with bone metastases from advanced disease. Denosumab also does not require the close monitoring and renal dosing that is needed with zoledronic acid.

Hypercalcemia that is refractory to bisphosphonates may be treated with gallium nitrate, plicamycin, or calcitonin. Calcitonin can quickly lower calcium levels, however, the effect is often transient. Plicamycin and gallium nitrate are associated with serious adverse effects and therefore, infrequently used. Glucocorticoids are effective in hypercalcemia secondary to elevated levels of vitamin D and can also be useful for relief of other symptoms related to metastatic disease. Long-term treatment and prevention of recurrence will ultimately require treatment of the underlying malignancy. Comfort care should be considered for truly refractory cases.

FEBRILE NEUTROPENIA

Infection can be a significant source of morbidity and mortality in cancer patients, especially in patients who are immunosuppressed from chemotherapy or who have low neutrophil counts secondary to their disease.

Etiology

While febrile neutropenia most frequently occurs in patients undergoing chemotherapy, it can also be seen in patients with acute leukemia, myelodysplatic syndrome, or in other diseases with leukopenias. In general, patients’ neutrophil counts tend to be at their lowest 510 days following the last dose of chemotherapy with recovery of counts within 5 days of this nadir. Common pathogens that cause febrile neutropenia include gram negative bacteria (E.coli, pseudomonas aeruginosa, and klebsiella pneumoniae), gram positive bacteria (staphylococcus species, streptococcus species, and enterococcus species) or polymicrobial infections. In about 75–80% of cases, however, no organism is able to be identified.

Clinical Signs/Symptoms

Fever is commonly the only symptom that these patients present with as other typical signs of infection can be masked in the setting of neutropenia. Other possible symptoms may include chills, diarrhea, rash, nausea, vomiting, cough, and shortness of breath. A thorough physical exam, including inspection of the oral cavity and perianal region, should be performed on these patients.

Diagnosis

Neutropenia is defined as an absolute neutrophil count (ANC) less than 1500 cells/microL and severe neutropenia is defined as an ANC less than 500 cells/microL or an ANC that is expected to decrease to less than 500 cells/microL in the next 48 hours. Risk of infection is higher in patients with severe neutropenia, especially when the neutropenia is prolonged (>7 days). Fever is defined as a temperature greater than 100.4°F that is sustained for more than an hour or a single temperature greater than 101.3°F. All patients who have received chemotherapy within 6 weeks of presentation and meet criteria for a systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) are assumed to have a neutropenic sepsis syndrome, unless proven otherwise.

Treatment

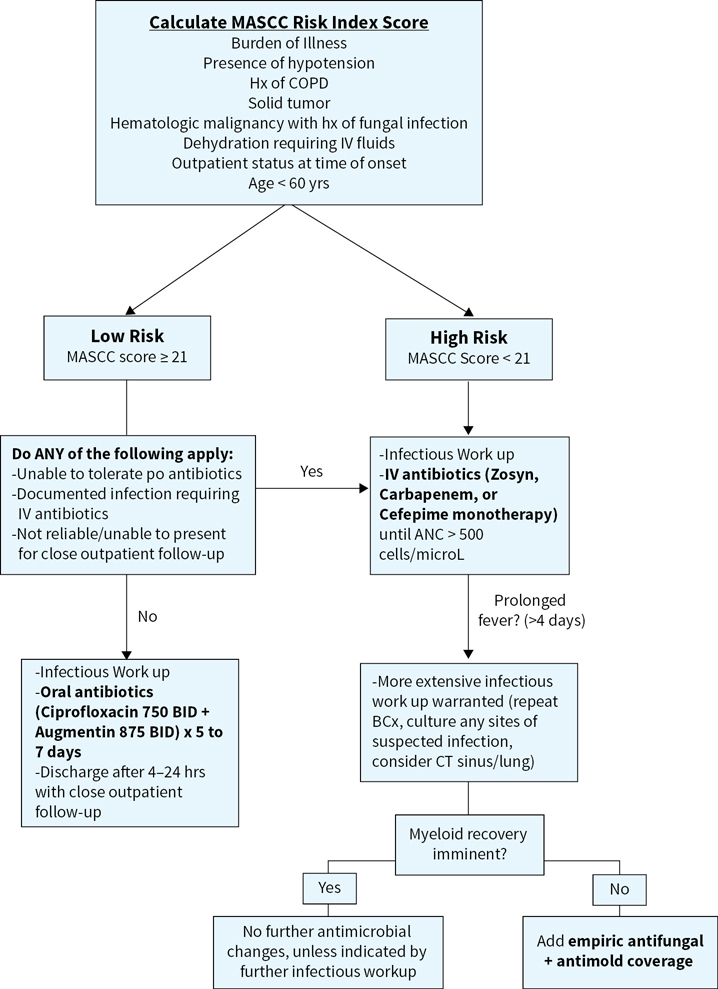

Febrile neutropenic patients should initially be stratified based on the MASCC (Multinational Association for Supportive Care in Cancer) risk index score to identify those that can be treated in an outpatient setting (see Figure 36.1). The MASCC score takes into account burden of illness, presence or absence of hypotension, history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), the type of tumor (solid vs. liquid), history of fungal infections, volume status, and age. A total score of 21 or greater indicates low risk of serious infection. These patients can be monitored in the ED for at least four hours after antibiotic initiation and should have all cultures drawn prior to discharge. They can be further treated as an outpatient with ciprofloxacin 750 mg twice daily in addition to amoxicillin/clavulanate 500 to 125 mg every 8 hours or alternatively with moxifloxacin monotherapy. Patients already on prophylactic fluoroquinolone therapy should not receive fluoroquinolone therapy for empiric treatment. For these patients, it would be reasonable to treat with an IV antibiotic regimen on an outpatient basis. Daily evaluation by a health-care provider is recommended for the first three days of treatment. Outpatient therapy is continued for 7 days or until the patient has been afebrile for 4 to 5 days.

Patients with a MASCC score of less than 21 are stratified as high-risk and should be admitted to the hospital for IV antibiotics and closer monitoring. Blood cultures, with one sample drawn from a peripheral vein and one from a central line, if available, should be drawn upon presentation. The remainder of the infectious workup may include urine culture, sputum culture (if available), stool studies, CSF analysis, chest X-ray +/– high resolution CT Chest. Once the diagnosis has been established and cultures have been collected, patients should be started on empiric antibiotic therapy (ideally within an hour of triage). Common agents used as monotherapy include cefepime, meropenem, imipenem-cilastatin, ceftazidime, and zosyn. Dual therapy agents include an aminoglycoside in addition to either piperacillin, cefepime, ceftazidime, or a carbapenem. Patients at high risk of gram-positive bacteremia should be started on an additional antibiotic with appropriate coverage, usually vancomycin. This group includes patients with gram positive colonization, catheter-related infections, and severe sepsis +/– hypotension. Urine output should be maintained at >0.5 ml/kg/hr. Fevers, on average, are expected to defervesce within 2 to 5 days of treatment. If the patient remains febrile on empiric antibiotics (>4 days) and is hemodynamically stable, the ANC should be evaluated. If myeloid recovery appears imminent, no change in antibiotics is needed. If myeloid recovery does not appear to be imminent, consideration should be given to obtaining a CT scan of the sinuses and lungs. It may also be beneficial to add anti-fungal +/– antimold coverage. If there is a documented infection and the patient is not responsive to targeted antibiotics, consider re-imaging, culture/biopsy/drain sites of worsening infection, and the addition of empiric antifungal therapy.

FIGURE 36.1Treatment algorithm for febrile neutropenia.

Suggested Readings

1.Araki, Kazuhiro, Yoshinori Ito, and Shunji Takahashi. Re: Superiority of denosumab to zoledronic acid for prevention of skeletal-related events: A combined analysis of three pivotal, randomised, phase 3 trials. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49(9):2264–2265. Web.

2.Cairo, Mitchell S, Stephen Thompson, Krishna Tangirala, and Michael T. Eaddy. Costs and outcomes associated with rasburicase versus allopurinol in patients with tumor lysis syndrome. Blood. 120.3175 (2012): Web.

3.Cancer Facts and Figures 2016. American Cancer Society. Web. 17 Oct. 2016.

4.Cervantes A, and Chirivella I. Oncological Emergencies. Annals of Oncology. 2004:299–306. Web.

5.Coiffier B, Altman A, Pui C-H, Younes A, and Cairo MS. Guidelines for the management of pediatric and adult tumor lysis syndrome: An evidence-based review. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(16):2767–2778. Web.

6.DeVita, Vincent T, Theodore S. Lawrence, and Steven A. Rosenberg. Section 16 Oncologic Emergencies. DeVita, Hellman, and Rosenberg's Cancer: Principles & Practice of Oncology. 9th ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2011:2123–2152. Print.

7.Halfdanarson, Thorvardur R, William J. Hogan, and Timothy J. Moynihan. Oncologic Emergencies: Diagnosis and Treatment. Mayo Clin Proc.2006;81(6):835–848. Web.

8.Higdon, Mark L, and Jennifer A. Higdon. Treatment of oncologic emergencies. American Family Physician.2006;74(11): 873–880. Web.

9.Larson, Richard A., and Ching-Hon Pui. Tumor Lysis Syndrome: Prevention and treatment. UpToDate, Oct. 2016. Web. Oct.17, 2016.

10.Nagaiah, Govardhanan, Quoc Truong, and Manish Monga. Chapter 36 oncologic emergencies and paraneoplastic syndromes. The Bethesda Handbook of Clinical Oncology. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2014. 468-79. Print.