OF ALL THE “REAL” MONSTERS that stir the Western imagination, there are few so romantic as the Loch Ness monster. I’m not even slightly immune to that romance. My love affair with Nessie blossomed early and strongly. What could be more wonderful than the idea that a living plesiosaur might slide undetected through the frigid waters of a Scottish lake? I sought out and devoured every book available in my elementary-school and community libraries. As a young boy wishing to learn more in those pre-Google days, I even asked the local reference librarian to track down the address of the Loch Ness Phenomena Investigation Bureau. (Alas, the organization was defunct by the time I tried to contact it.)

In the pulpy books on the paranormal, I studied the famous cases, marveled at the amazing photographs of arching necks and underwater flippers, and absorbed the standard arguments. “Loch Ness is connected to the sea through underwater tunnels,” I told my classmates at recess. (I was unaware that the surface of Loch Ness is more than 50 feet above sea level.) “Do you know why Nessie wasn’t reported until 1933?” I asked on the playground. “Because that’s when they finally built the road beside the loch!” (I now know that the road predates Nessie by more than a century.)

1If my understanding of the Nessie literature was a bit uncritical, at least my research techniques were inventive. I remember crouching around a Ouija board in my fifth-grade classroom, pragmatically asking the spirits at which end of Loch Ness I should concentrate my search for the monster. (Or perhaps this was not so innovative. Seven years before my Ouija board consultation, mentalist Tony “Doc” Shiels allegedly led a team of psychics—successfully, he claimed—to summon Nessie and other “aquatic serpent dragons throughout the world.”)

2Years later, my love of these wonderful stories led me to the skeptical literature. Eventually, I found myself a magazine writer, which offered me the professional opportunity to pursue my childhood dreams of investigating monster mysteries. And so, it is with great pleasure that I turn now to the enduring mystery of the Loch Ness monster.

LOCH NESS

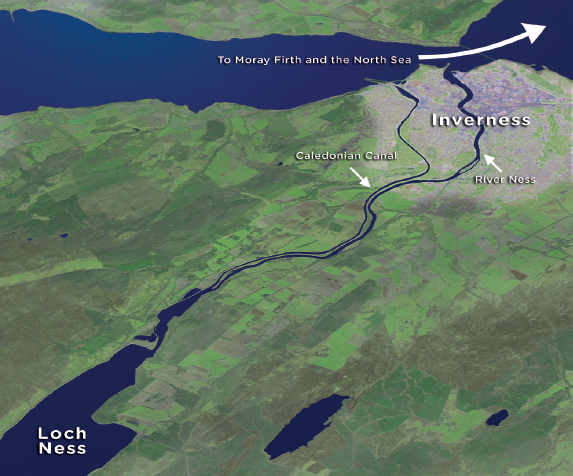

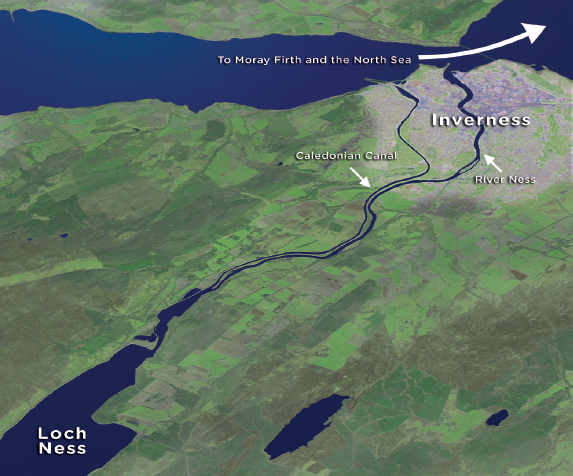

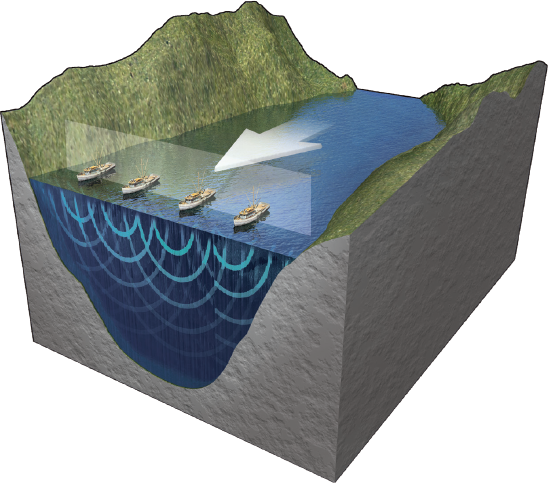

Loch Ness is a long, deep lake that lies on a geological fault line—a country-spanning cleft called the Great Glen. Bisecting Scotland from coast to coast, the Great Glen features several large lakes, of which Loch Ness is the largest (

figure 4.1). At 22 miles long and around 754 feet maximum depth, Loch Ness is the United Kingdom’s largest body of freshwater. It is also, according to legend, the home of an unknown species of large animal. If there is a Loch Ness monster, it is a recent arrival. The steep sides of the loch were scoured by glaciers during the Ice Age of the Pleistocene epoch (2.5 million–11,700 years ago). Indeed, the whole of Scotland was crushed beneath a half-mile-thick sheet of solid ice as recently as 18,000 years ago (or less)!

3

Figure 4.1 Loch Ness is the largest of the lakes along the Great Glen, which bisects Scotland. Since 1822, these lakes have been linked by the Caledonian Canal, allowing water travel from the North Sea to the Atlantic Ocean across the middle of Scotland. (Image by Daniel Loxton)

Today, Loch Ness is connected to the Moray Firth inlet of the North Sea by the 7-mile length of the River Ness (

figure 4.2).

4 Since 1822, Loch Ness has been also been part of a shipping channel called the Caledonian Canal.

5 Composed of a series of canals, locks, and natural lakes, the Caledonian Canal allows ships to cross Scotland from coast to coast. The route runs by canal through several locks from Moray Firth to Loch Ness (in parallel to the River Ness), continues down the length of Loch Ness, and then proceeds by canal to Loch Oich (and, eventually, to Scotland’s west coast). Thus Loch Ness has been busy and well traveled for almost 200 years. Indeed, Loch Ness was well used and well populated even before the construction of the canal, crossed for centuries by boats and bordered by roads, towns, and villages (and, at the mouth of the River Ness, near the loch’s northern end, the sizable city of Inverness). The opening of the canal ushered in a tourism boom, with daily steamship traffic running the length of Loch Ness. “Far from being a lonely, uninhabited spot before 1933,” explains Ronald Binns, “Loch Ness was extremely popular with the leisured English middle-classes during the previous hundred years.” Even Queen Victoria toured Loch Ness. Almost a century before the birth of the modern monster legend, Loch Ness was already overrun with recreational traffic, according to one disgruntled naturalist. He complained bitterly about the noisy, polluting steamboats “full of holiday people, with fiddles and parasols conspicuous on the deck.”

6

Figure 4.2 Loch Ness is connected to the Moray Firth and the North Sea by two short, parallel waterways: the River Ness and the Caledonian Canal–both of which run through the city of Inverness. (Image by Daniel Loxton)

BEFORE NESSIE

Water-Horses

As we look toward the emergence of the Loch Ness monster in the 1930s, it is important to understand that a teeming menagerie of water-based supernatural creatures had already lived for centuries in Scottish folklore. In addition to the Great Sea Serpent—such as the Stronsay Beast, whose carcass washed up on the island of Stronsay in 1808 (

chapter 5), and the sea serpent sighted in one of the inland freshwater lakes of the northern Isle of Lewis in 1856

7—Scotland’s feared folkloric monsters include the

boobrie (a giant carnivorous waterfowl), the

buarach-bhaoi (a nine-eyed eel that twists its body into a shackle around the feet of prey), the

biasd na srogaig (a clumsy one-horned water beast with vast legs), and even the twelve-legged “big beast of Lochawe.”

8Among this horde of folkloric creatures are the widespread traditions of kelpies (associated with running water), water-bulls, and water-horses (

Each uisge, which haunted lochs and the sea).

9 Today, these related but distinct mythological creatures are harnessed in service of the legend of the Loch Ness monster, but there are strong reasons to think that this linkage is inappropriate. First, none of these creatures is anything like the modern Loch Ness cryptid. Second, none of them is indigenous to Loch Ness.

In Scottish folklore, water-bulls are small black bulls that are encountered when they venture onto land; they sometimes breed with terrestrial cattle before returning to the water. Water-horses (whether

Each uisge or the distinct but similar kelpies) are lethal, shape-shifting demons. They are likewise encountered on land in the form of ordinary-looking horses, often with weeds in their manes and wet-looking, adhesive skin. If anyone is foolish enough to climb onto the back of a water-horse, he or she will become stuck in place—and the water-horse will carry the rider screaming into the water. Children are a favorite prey of water-horses. “Often he grazes in a field near the water,” as one historian described the folklore in 1933, “and by his tameness tempts children to mount him. As they mount, he lengthens his back until all are accommodated in a line, when he rushes with them into the water.” (A common folk tale describes a single surviving child who touches the monster and then must cut off his own finger to escape. But all his friends are carried off to their deaths.)

10

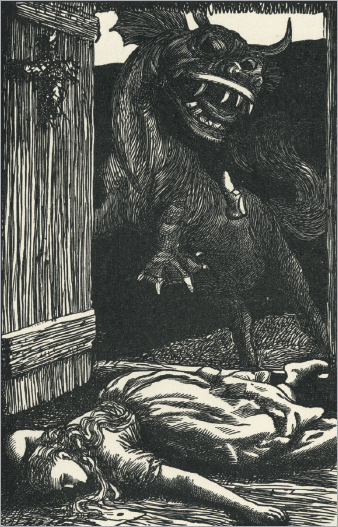

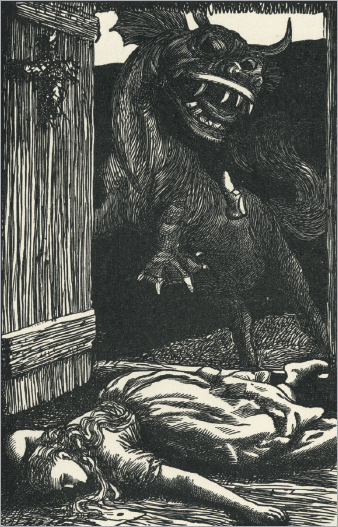

Figure 4.3

In a tale retold by W. Carew Hazlitt, a ravenous kelpie pursues a beautiful maiden. After a desperate flight, she escapes over the threshold of her house and collapses. Vampire-like, the kelpie is unable to enter the open door because it is protected by a branch from a rowan, a tree believed to offer protection against malevolent beings, but does capture the young woman’s shoe, which extended slightly beyond the boundary of magical protection when she fell. (From W. Carew Hazlitt, Dictionary of Faiths and Folklore: Beliefs, Superstitions, and Popular Customs [London: Reeves and Turner, 1905], facing 334)

Water-horses are much closer to vampires or werewolves than to any modern cryptid (

figure 4.3). “When killed, the water-horse proved to be nothing but turf and a soft mass like jelly-fish,” explained an article about the mythical beasts of Scotland, just weeks before the dawn of the Nessie legend. “It could be shot only with a silver bullet, excellent proof of its supernatural character.”

11 Even more vampire-like, water-horses can take human form: “In such form he very often goes courting a young woman, with the entirely unromantic object of eating her.”

12Supernatural creatures with no true physical form, water-horses can be identified with modern cryptids only by badly distorting Scottish folklore. They do not act like or resemble Nessie in any meaningful respect. Moreover, they are part of global folklore and have no unique association with Loch Ness. Water-horses are said to lurk in most of the bodies of water in Scotland, including Loch Lomond, Loch Glass, Loch Awe, Loch Rannoch,

13 Loch Cauldsheils, Loch Hourn, Loch Basibol,

14 Loch na Mna (on the island of Raasay),

15 Loch Garbet Beag, Loch Garten, and Loch Pityoulish.

16 Nor are they restricted to the United Kingdom. According to folklorist Michel Meurger, water-horses “are very widespread: the British Isles, Scandinavia, Siberian Russia, France, Italy, Czechoslovakia, and Southern Slavic countries.”

17 Water-horses were even found in the New World. In 1535, while exploring a tributary to the Saint Lawrence, Jacques Cartier heard that “within this river are some fish shaped like horses, which at night take to the land and by day to the sea, as we are told by our savages.”

18Hoaxes and Mistakes

The tradition of lake monster and sea serpent hoaxes also long predates the modern Nessie legend. One notable example occurred in upstate New York in 1904—an elaborate hoax involving a carved wooden monster submerged in Lake George by pulleys. (In 1934, the elderly hoaxer revealed the trick and expressed his opinion that Nessie was a similar prank.)

19 Indeed, it seems that monster hoaxing even occurred at Loch Ness in particular, several decades before Nessie. In 1868, a “bottle-nosed whale about six feet long” was found on the banks of Loch Ness. This “monster” caused quite a stir, drawing “large crowds of country people” before it was identified. The

Inverness Courier concluded that the cetacean “had, of course, been caught at sea, and had been cast adrift in the waters of Loch Ness by some waggish crew” as a prank. “The ruse,” said the newspaper, “was eminently successful.”

20 (Adrian Shine, head of the respected Loch Ness and Morar Project, describes this story as “the earliest reference we’ve found to something more than the Water Horse of legend.”

21 Similar hoaxes have occurred in more recent times: a dead elephant seal was dumped in Loch Ness in 1972 and dead conger eels in 2001.)

22Likewise, the history of water monster misidentification is long and well documented, throughout the world and at Loch Ness in particular. In 1852, as reported in the Inverness Courier, an armed mob prepared to battle a “sea serpent” at Loch Ness—literally with pitchforks!

One day last week, while Lochness lay in a perfect state of calm, without a ripple on its surface, the inhabitants of Lochend were suddenly thrown into a state of excitement by the appearance of two large bodies steadily moving on the loch, and making for the north side from the opposite shore of Aldourie. Every man, woman and child turned out to be witness to the extraordinary spectacle. Many were the conjectures as to what species of creation these animals could belong; some thought it was the sea serpent coiling along the surface, and others a couple of whales or large seals. As the uncanny objects approached the shore various weapons were prepared for the onslaught. The men were armed with hatchets … the young lads with scythes, and the women principally with pitchforks. One fierce-looking amazon, wielding a tremendous flail about her head, commenced to flagellate a hillock by way of practice. At last a venerable patriarch … set to fetch an old [rifle] … took aim, and was just on the eve of firing when suddenly he dashed the gun to the ground.

23The man cried out in shock at what he took to be supernatural waterhorses,

24 but the shock was short-lived. The creatures were “not actually the much dreaded ‘kelpies,’” the newspaper continued, but perfectly ordinary, well-known animals. In fact, “they proved to be a valuable pair of ponies … indulging themselves with a dip in the cooling waters of Lochness.” (Remarkably, the animals had swum “fully a mile” across the lake.)

This case brings two salient facts into sharp focus. First, it is possible for people to mistake ordinary animals for mysterious monsters—even crowds of people and even in broad daylight. Second, neither this group of locals nor the Inverness Courier gave any hint of an ongoing tradition of monsters in the loch. (All the explanations proposed in the story—sea serpent, whales, seals, and kelpies—are generic. None are specific to Loch Ness.)

Dressed with folklore and mischief, the Loch Ness stage had been prepared for decades—centuries—without any star to step on it. But in the 1930s, all that was to change.

A SERIES OF SIGHTINGS

“Three Young Anglers”

This brings us to a small news story from 1930 that may (depending on your point of view) be considered the first modern Loch Ness monster case. According to the

Northern Chronicle, “three young anglers”

25 had a strange experience while fishing for trout on Loch Ness, as described by Ian Milne, one of the men:

About 8:15 o’clock we heard a terrible noise on the water, and looking around we saw, about 600 yards distant, a great commotion with spray flying everywhere. Then the fish—or whatever it was—started coming toward us, and when it was about 300 yards away it turned to the right and went into the Holly Bush Bay above Dores and disappeared in the depths. During its rush it caused a wave about 2½ feet high, and we could see a wriggling motion, but that was all, the wash hiding it from view. The wash, however, was sufficient to cause our boat to rock violently. We have no idea what it was, but we are quite positive it could not have been a salmon.

26This story is in many ways a bit of a dud. The witnesses did not actually see a monster, and the story died in the news very quickly. (Interestingly, the newspaper also claimed to have spoken with an unnamed “keeper who dwells on the shores of the loch” who “some years ago saw … the fish—or whatever it was—coming along the centre of the loch, and afterwards stated that it was dark in color and like an upturned angling boat, and quite as big.” Little was made of this alleged sighting, which was not recorded at the time it occurred.)

27But the “three young anglers” story is noteworthy in other ways. It is one of the vanishingly few reports of anything like a Loch Ness monster recorded before 1933. It also is one of the first to use (even if offhand) the term “monster” in relation to Loch Ness. In a skeptical letter to the

Inverness Courier, someone going under the name Piscator paraphrased Milne’s account as describing “a wave 2½ feet high caused by some unknown monster that, presumably, inhabits Loch Ness.”

28 Retelling the tale in a small item two months later, the

Kokomo Tribune claimed, “People in the vicinity of Loch Ness, in Scotland, are much mystified over reports of a monster having taken up its abode in the lake.”

29“Strange Spectacle on Loch Ness”

The “three young anglers” case of 1930 failed to ignite a popular monster legend. But it was remembered by at least one person: a small-town, part-time reporter named Alex Campbell.

Then, in 1933, Campbell heard that his friends Aldie

30 and John Mackay (proprietors of the Drumnadrochit Hotel)

31 had spotted something in the water while driving along the shore of Loch Ness. Campbell wrote the story for the

Inverness Courier, which ran it under the headline “Strange Spectacle on Loch Ness: What Was It?”

Loch Ness has for generations been credited with being the home of a fear-some-looking monster, but, somehow or other, the “water kelpie,” as this legendary creature is called, has always been regarded as a myth, if not a joke. Now, however, comes the news that the beast has been seen once more, for, on Friday of last week, a well-known businessman, who lives in Inverness, and his wife (a University graduate), when motoring along the north shore of the loch … were startled to see a tremendous upheaval on the loch, which previously had been as calm as the proverbial millpond. The lady was the first to notice the disturbance, which occurred fully three-quarters of a mile from the shore, and it was her sudden cries to stop that drew her husband’s attention to the water. There, the creature disported itself, rolling and plunging for fully a minute, its body resembling that of a whale, and the water cascading and churning like a simmering cauldron. Soon, however, it disappeared in a boiling mass of foam.

32Presto: Loch Ness was home to a “fearsome-looking monster” and suddenly had been “for generations”!

Campbell’s story was a bit on the sensational side. The Mackays clarified their sighting later that year when they spoke with Rupert Gould. First, Aldie was the only one who saw any kind of object or animal; her husband saw only splashing. The article’s “tremendous upheaval” was perhaps a little exaggerated: Aldie “thought at first that it was caused by two ducks fighting” (although she decided, “on reflection,” that the splashing was “far too extensive to be caused this way”). When she finally saw the cause of the splashing, it was not one body “resembling that of a whale,” but two dark humps in the distance. The two humps had a total length (she estimated) of about 20 feet.

33 (If accurate, this would make each hump about the size of a seal. Because Loch Ness is connected to the North Sea by both a river and a canal, seals play an important role in Nessie debates to this day—as we will see.)

Campbell was quick to tie the Mackays’ sighting to the “three young anglers” case from three years earlier. In the original version of that story, the three fishermen did not see the cause of the splashing and had “no idea what it was”; in Campbell’s revisionist retelling, they saw “an unknown creature, whose bulk, movements, and the amount of water displaced at once suggested that it was either a very large seal, a porpoise, or, indeed, the monster itself!” This was pure embellishment by Campbell. The newspaper account from 1930 contains no hint that the three fishermen suggested a seal, porpoise, or monster as an explanation for the spray or the wave.

In any event, the news of the Mackays’ sighting (unimpressive even with the help of Campbell’s purple prose) was met with considerable skepticism. In a response to the

Inverness Courier, steamship captain John Macdonald expressed exasperation with the Mackays’ amateur description of a tremendous upheaval on the loch. “I am afraid,” he wrote, “that it was their imagination that was stirred, and that the spectacle is not an extraordinary one.” During fifty years of navigating the loch (“no fewer than 20,000 trips up and down Loch Ness”), Macdonald had become familiar with an ordinary occurrence that very closely matched the Mackays’ description: “sporting salmon in lively mood, who, by their leaping out of the water, and racing about, created a great commotion in the calm waters, and certainly looked strange and perhaps fearsome when viewed some distance from the scene.” Proposed within days, this very plausible explanation for the Mackay case—by most accounts, the original Loch Ness monster sighting—was an event that the steamship captain had “seen many hundred times.”

34The Mackays’ sighting was a weak case by any reasonable standard, but this small, faltering spark would soon flare into perhaps the greatest monster mystery of modern times. Why did the notion of a monster in Loch Ness come to catch the public imagination in 1933, when the “three young anglers” case of 1930 did not? The Mackays’ modest story and George Spicer’s much more spectacular sighting, which would soon follow it, had something going for them that the “three young anglers” story had not: the release of one of the biggest blockbuster monster films in Hollywood history.

King Kong

Between the Great Depression and the rise of Nazi Germany, media audiences were ready for a diverting popular mystery. The centuries-old folklore traditions of water-horses and sea serpents had the potential to supply such a mystery, but something more was needed—a catalyst.

Hollywood supplied the perfect catalyst at the perfect time: the gigantic, long-necked water monster depicted in

King Kong (and again in

Son of Kong, later in 1933). I am not the first researcher to draw a connection between Nessie and

King Kong. For example, Dick Raynor suggests a link, noting that, as a result of the film, the “entire western world was gripped by monster fever” in early 1933.

35 Ronald Binns agrees that “it is probably no coincidence that the Loch Ness monster was discovered at the very moment that

King Kong … was released across Scotland in 1933.”

36 But I think that a stronger relationship between the film and the myth can be asserted than has usually been argued in the past: in essence, that

King Kong directly inspired the Loch Ness monster.

There is no question that the birth of Nessie correlates closely in time with the release of the film.

King Kong opened in London on April 10, 1933, just four days before Aldie Mackay’s sighting of the “disturbance” in Loch Ness.

37 The film was an instant box-office smash: “Thousands are being turned away from

Kong,” reported the

Daily Express from Trafalgar Square. Those who did make it into the packed theaters came out “white and breathing heavily.” It was a sensation—a monster thriller so real and so terrifying that moviegoers cried out in their seats.

38As the notion of a “fearsome-looking monster” at Loch Ness began to quietly percolate, the

Scotsman marveled at

King Kong’s success in “giving the impression that its monsters have newly emerged from the primaeval slime.” Most important, the film created a viscerally believable illusion of “prehistoric monsters in contact with modern conditions.”

39These two correlated factors—the sighting by the Mackays and the release of King Kong—soon inspired the most influential Nessie report of all time.

“The Nearest Approach to a Dragon or Prehistoric Animal”

A very few vague sightings followed the Mackays’ story over the summer of 1933, but those first small embers of popular belief were fading. And then, in August, the legend suddenly burst into incandescence—and the influence of King Kong became unmistakable.

On August 4, the

Inverness Courier published an astonishing letter from a Londoner named George Spicer. He had, he said, recently spotted a strange creature while driving along the shore of Loch Ness with his wife. His description of their spectacular sighting in broad daylight changed the legend forever: “I saw the nearest approach to a dragon or prehistoric animal that I have ever seen in my life. It crossed my road about fifty yards ahead and appeared to be carrying a small lamb or animal of some kind. It seemed to have a long neck which moved up and down, in the manner of a scenic railway, and the body was fairly big, with a high back.”

40This account, essentially describing a dinosaur strolling across a road in modern Scotland, was (according to one respected Nessie researcher) “so extraordinary it taxed the imagination of even the most confirmed believers.”

41 Yet the influence of the Spicer case simply cannot be overstated. As Adrian Shine explains, “There were no records of long neck sightings before the Spicers’ encounter on land made the first connection to plesiosaurs.”

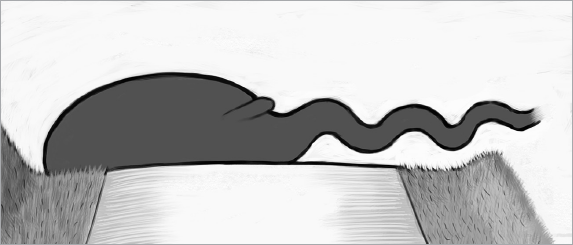

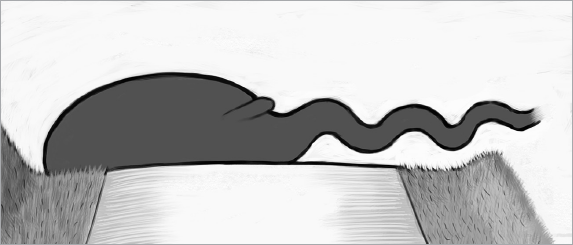

42Figure 4.4 The water monster in a scene from King Kong. (Redrawn by Daniel Loxton)

Whereas the few previous witnesses had reported mere splashes or humps in the water, Spicer claimed a close-up view of a long-necked creature that could have been lifted right off of King Kong’s Skull Island. And that, I believe, is exactly what happened.

Among the most memorable scenes in

King Kong is a night attack by a long-necked water monster. As crewmen from the

Venture raft tensely across a fog-shrouded lake in pursuit of the abducted heroine, something sinister stirs in the water. A dark, swan-like neck arcs out of the water and then slides back out of sight. The men peer through the dense fog, when suddenly the looming neck attacks out of the darkness. The raft is overturned, spilling the men into the lake. In a series of dramatic shots, the huge, plesiosaur-like animal plucks men out of the water and kills them. This creature—with its rounded back, arched neck, and small head—is essentially identical to the plesiosaur-like popular Nessie that would grow out of Spicer’s story (

figure 4.4). As the remaining

Venture crewmen scramble to the seeming safety of the shore, they learn a terrible truth: the creature is not an aquatic plesiosaur, but a

Diplodocus-like sauropod! The monster pursues the men onto land—and, at this point, Spicer’s sighting snaps sharply into focus.

In both his description and his sketch, Spicer almost exactly re-created this scene from

King Kong. Spicer’s creature crossed the road from left to right, just as the

Diplodocus on land crosses the movie screen (

figure 4.5). As Spicer’s beast “crossed the road, we could see a very long neck which moved rapidly up and down in curves … the body then came into view”;

43 for its part, the somewhat implausibly writhing neck of the film’s dinosaur enters first, followed by its huge body. The movie’s creature gives the impression of having gray, elephant-like skin; Spicer’s creature had gray skin, “like a dirty elephant or a rhinoceros.”

44 The 30-foot Loch Ness beast is of roughly similar size to the movie monster: “When it was broadside on it took up all the road…. It was big enough to have upset our car…. I estimated the creature’s length to be about 25–30 feet.”

45

Figure 4.5 The “prehistoric animal” as described by George Spicer. (Illustration by Rupert Gould, under Spicer’s direction; redrawn by Daniel Loxton from Rupert T. Gould, The Loch Ness Monster [1934; repr., Secaucus, N.J.: Citadel Press, 1976])

A few other diagnostic details make the case especially compelling. In the shots from the movie, the sauropod’s feet are not visible. (For ease of animation, they are shielded from view by bushes and enshrouding fog.) Likewise, in Spicer’s version, “We did not see any feet.” Especially striking is the profile that the two creatures have in common. The film’s

Diplodocus is shown with its tail curved out of view around the far side of its body. According to Spicer’s description of his monster, “I think its tail was curved round the other side from our view.”

46Finally, there is the troublesome description in Spicer’s letter to the

Inverness Courier that the monster “appeared to be carrying a small lamb or animal of some kind.”

47 Later, paraphrased versions of his story suggested that the “lamb or animal” could refer to the end of the creature’s tail sticking up above its shoulder (or perhaps something riding on the monster’s back); but, at face value, this appears to be a direct description of the last shot in

King Kong’s sauropod scene. Reaching into a tree, the dinosaur grabs a surviving crew member in its mouth and shakes him. In a shot that exactly matches Spicer’s sketch, the doomed man looks exactly like a “small lamb or animal of some kind” in the monster’s mouth!

This is not the first time that a similarity between the film and the sighting has been noted. Rupert Gould discussed

King Kong with Spicer just months after the sighting: “While discussing his experience, I happened to refer to the diplodocus-like dinosaur in

King Kong: a film which, I discovered, we had both seen. He told me that the creature he saw much resembled this, except that in his case no legs were visible, while the neck was much larger and more flexible.”

48 But despite the red flag of Spicer’s admission that he had seen

King Kong and that his creature looked like the monster in the film (and even though the obscuring of the creature’s legs and feet was a striking detail that the sighting and the film version shared), Gould seems to have moved on without further comment. More recently, Shine’s always thorough research zeroed in on both the pivotal importance of Spicer’s story (being, once again, the original report of a long-necked monster at Loch Ness) and the significance of Spicer’s discussion of

King Kong.

49 “I believe personally that

King Kong was the main influence behind the ‘Jurassic Park’ hypothesis at Loch Ness,” Shine confirmed, when asked about the likelihood of a connection. “Before Spicer’s land sighting there were no long neck reports at all and it was the long neck that was so crucial.”

50 Shine does not seem to have specified the details of the similarities in print, however, and most researchers overlook this smoking gun altogether.

What we are left with is familiar to critical researchers of other paranormal topics, such as UFOs: a feedback loop among popular entertainment, news media, and paranormal belief. The Loch Ness monster grew out of an existing genre of fictional encounters between modern humans and prehistoric creatures (plesiosaurs and sauropods, in particular). Audiences for the hit silent film

The Lost World (1925) watched a

Diplodocus rampage through the streets of London and those for

King Kong saw another stop-motion sauropod dinosaur attack a raft full of men. These fictional stories prepared the public imagination to accept similar “true” stories that the press happily publicized. The press hype ensured further public interest, which inevitably generated more reports. Some were hoaxes, of course, but many were mistakes generated by expectant attention. In 1934, Gould gravely noted “the undoubted fact that, in proportion, as more people looked for the ‘monster,’ more people saw it.”

51 Then, popular fiction stepped in to recursively capitalize on the media-based monster of Loch Ness. The first feature film version,

The Secret of the Loch, hit theaters less than a year after Spicer’s sighting! (Almost inevitably, the lead character declares the Loch Ness monster to be—what else?—a

Diplodocus.)

“Horrible Great Beast”

Triggered by the Spicer case, a wave of new sighting reports poured in. The sheer number of accounts not only seemed to show that the monster was real, but also exposed a critical flaw in the newly minted legend. “There is one vital question regarding it which must always cause warrantable doubt,” one writer nailed it in 1938. “Why have we heard of it only within the last five years or so, when there is no authenticated record of its existence in the centuries which have gone?”

52While news coverage asserted a “traditional Loch Ness ‘monster’—a superstition which has existed for generations,”

53 knowledgeable locals refuted these media claims. Scolding the

Inverness Courier in 1933, steamship captain John Macdonald wrote, “It is news to me to learn, as your correspondent states, that ‘for generations the Loch has been credited with being the home of a fearsome monster.’”

54A genuine monster should imply a history of monster sightings. Where were they? Seeking such a history, people turned to old sources—and old memories—in search of support. Newspapers carried many letters like this one from the Duke of Portland:

Sir,—The correspondence about “the Monster” recently seen in Loch Ness reminds me that when I became the tenant in 1895, nearly forty years ago, of the fishings in the River Garry and Loch Oich, the ghillies, the head forester, and several other individuals at Invergarry often discussed a “horrible great beast,” as they termed it, which appeared from time to time in Loch Ness. None of them, however, claimed to have seen it themselves, but each one knew individuals who had actually done so.

55It is difficult even to know what to say about this story. After the media hype started, the duke came forward to say that he remembered that forty years earlier, he had heard some hearsay about a monster? Rupert Gould rather understated the provenance problem when he said of this claim, “Although interesting, such stories are of no great value as evidence.”

56 Yet, to this day, many Loch Ness monster sources include this story, without comment, as a firsthand sighting in 1895 by multiple witnesses.

57 Other similarly backdated tales, about alleged but unrecorded events or hearsay from decades earlier, are interspersed with older stories of uncertain or unlikely relevance to create a fictional time line of Nessie prehistory. Some early references included on the canonical time line are invented from whole cloth. For example, one full-page article in the

Atlanta Constitution is rumored to have described a modern Loch Ness monster (complete with woodcut illustration) in the 1890s. This would be important if true, but it appears that the article never existed. (All attempts to locate it have failed.)

58Despite this fictive history, the truth is that unambiguous Nessie sightings did not exist before the release of

King Kong and the subsequent media hype. Some monster proponents confront this state of affairs honestly. With the possible exception of the “three young anglers” case, writes Henry Bauer, “I can produce nothing written before 1933 that unequivocally refers to large, nonmythical animals in Loch Ness.”

59Still, as 1933 wore on and reports of sightings of the Loch Ness monster accumulated, people found apparent corroboration in the form of supernatural folklore. To begin with, there were the kelpie traditions, notwithstanding that they are hardly exclusive to Loch Ness. But enthusiasts soon unearthed a more specific tale that appeared to establish Nessie’s antiquity.

THE STORY OF SAINT COLUMBA

Within an early medieval biography called The Life of Saint Columba, there is a brief but exciting description of a Catholic saint’s confrontation with a “water beast” at the River Ness. Now considered the canonical “first recorded sighting” of the Loch Ness monster, this anecdote is said to establish a provenance for Nessie that dates back 1,300 years. Unfortunately, there are good reasons to suspect that this encounter never occurred.

Columba (ca. 521–597) was an Irish monk who in 563 traveled to Scotland as a missionary and established a monastery on the island of Iona. About a century after Columba’s death, Adomnán, the ninth abbot of Iona, wrote a biography of his predecessor. This fascinating work is considered one of the most important windows into early Scottish culture, so it is not surprising that monster proponents wish to claim it.

The story goes like this: Columba and his monks encountered some locals conducting a burial at the river’s edge. When he asked what had happened, Columba was told that a terrible beast had killed a swimmer. Hearing this, Columba directed one of his companions to swim across the river and fetch a boat from the other side. The monk obediently leaped into the water:

But the beast, not so much satiated by what had gone before as whetted for prey, was lurking at the bottom of the river. Feeling the water above it disturbed by the swimming, and suddenly coming up to the surface, it rushed with a great roaring and with a wide-open mouth at the man swimming in the middle of the streambed. On seeing this, the blessed man, together with all who were there—the barbarians as much as the brethren being struck with terror—drew the sign of the saving cross in the empty air with his upraised holy hand. Having invoked the name of God, he commanded the ferocious beast, saying, “Go no further! Nor shall you touch the man. Turn back at once.” Then indeed the beast, hearing this command of the holy man, fled terrified in pretty swift retreat, as if it were being hauled back with ropes; though just before this it had approached the swimming [monk] so closely that, between man and beast, there had not been more than the length of a small boat-pole.

60This does sound like a powerful endorsement for the legend of the Loch Ness monster. But this superficial resemblance between the river monster and Nessie is a coincidence and is profoundly useless as evidence. The problem is that Adomnán’s Life of Saint Columba is a hearsay-based biography of a man whom Adomnán never met—a larger-than-life historical figure who was, by Adomnán’s day, already shrouded in legend. Drawing from monastic documents, local folklore, second- (and third- and fourth-) hand testimony, and travelers’ tales from faraway lands, Adomnán collected hundreds of unrelated and mostly implausible anecdotes—some as short as two unsupported sentences. He had no way even to put them in chronological order. Each story simply begins “At another time …” or “On another day….”

Like other early medieval hagiographic literature,

The Life of Saint Columba is packed with magic, monsters, and spine-tingling supernatural forces. In addition to making prophecies and performing healing miracles, Columba is said to have calmed storms, turned water into wine, summoned water from a stone, driven out “a Demon that Lurked in a Milk-pail,” raised the dead, enchanted a stick so that wild animals would impale themselves on it every night, comforted a weeping horse as it “shed copious tears”—and so on. The water beast story is but one of several animal-related anecdotes, each showing the saint’s holy power over wild beasts (a boar, a water beast, poisonous snakes). In this context, concluded historian Charles Thomas, the monster tale emerges as just “one minor literary trope within a deliberate and overt piece of religious propaganda.”

61 Worse, the story was a cliché. As Thomas points out, medieval hagiographies very often include saintly adventures “in which snakes, or serpents, or dragons—terrestrial or aquatic, with or without wings, silent or bellowing—figured as stock properties in every variety of resuscitation or repulsion miracle.”

62The bottom line is that no one knows what Columba saw. Indeed, there is no reason to think that this encounter happened. No one knows where the story came from, and it cannot be used as evidence of anything.

Unfortunately, Thomas was right when he wrote that it was “too much to hope that future writers on the topic of the Loch Ness Monster will abandon this reference as irrelevant and misleading.”

63 Today, more than twenty years later, virtually all Loch Ness monster sources continue to showcase Saint Columba’s as the “first recorded Nessie sighting”—the centerpiece of a revisionist time line cobbled together from “sightings” that entered the record (as decades-old or even millennia-old hearsay) only after the start of the Nessie media circus.

THE EMERGENCE OF THE “PLESIOSAUR HYPOTHESIS”

Inspired by the sauropod dinosaur in King Kong, George Spicer created the legend of a long-necked monster at Loch Ness. In turn, his yarn gave rise to many other dinosaur-like and plesiosaur-like sightings. Promoted in news reports and supported by photographs of alleged monsters, these eyewitness accounts made the “plesiosaur hypothesis” a favorite explanation for Nessie throughout the twentieth century.

The groundwork for this notion had been laid as early as 1833, when naturalists began to suggest that a surviving population of prehistoric marine reptiles (known from newly discovered fossils) could be the best explanation for sea serpent sightings.

64 The idea received a big boost from an immensely popular science writer named Philip Henry Gosse in 1861.

65 The concept of surviving plesiosaurs was further popularized in widely read science-fiction stories, such as Jules Verne’s

Journey to the Center of the Earth (1864). Science-fiction writers even relocated the marine reptiles to freshwater lakes. One short story, “The Monster of Lake LaMetrie” (1899) by Wardon Allan Curtis, features a violent encounter between a scientist and an

Elasmosaurus that has been cast up from the hollow center of Earth (

figure 4.6).

66 Familiar as we are with the conceit of a Loch Ness plesiosaur, these stories now read as clear foreshadowing of the Nessie narrative and the cryptozoological hopes that it embodies. Consider this passage from Arthur Conan Doyle’s runaway hit

The Lost World:

Figure 4.6 The skull of an elasmosaur at the Courtenay and District Museum and Palaeontology Centre, Courtenay, British Columbia. (Image by Daniel Loxton)

Here and there high serpent heads projected out of the water, cutting swiftly through it with a little collar of foam in front, and a long swirling wake behind, rising and falling in graceful, swan-like undulations as they went. It was not until one of these creatures wriggled on to a sand-bank within a few hundred yards of us, and exposed a barrel-shaped body and huge flippers behind the long serpent neck, that Challenger, and Summerlee, who had joined us, broke out into their duet of wonder and admiration.

“Plesiosaurus! A fresh-water plesiosaurus!” cried Summerlee. “That I should have lived to see such a sight! We are blessed, my dear Challenger, above all zoologists since the world began!”

67Perhaps not coincidentally, the speculation that a population of plesiosaurs could have survived in the oceans was advocated in 1930 by Rupert Gould,

68 who went on to write the first and most influential book about the Loch Ness monster! The notion that Loch Ness, in particular, might shelter plesiosaurs was raised as early as August 9, 1933, immediately following Spicer’s sighting of a long-necked monster. Linking Nessie to sea serpents, the

Northern Chronicle argued that there can be little doubt that the Loch Ness creature “is a surviving variant of the Plesiosaurus.”

69 Strangely enough, it was Alex Campbell, the author of the

Inverness Courier’s original Aldie Mackay sighting story, who pushed the plesiosaur idea the hardest. Having written the canonical first Loch Ness monster news story and conjured up the fakelore that “Loch Ness has for generations been credited with being the home of a fear-some-looking monster,” Campbell went on to claim that he personally had seen a plesiosaur in Loch Ness—multiple times.

In October 1933, Campbell and his neighbor told reporter Philip Stalker that they had experienced spectacular sightings of the monster.

70 Stalker wrote that these “men whose honesty and reliability have never been called in question” described the creature as “being of the same form as a prehistoric animal: resembling most nearly the plesiosaurus. That is to say that they described its form, and when shown a sketch of a plesiosaurus stated that was the kind of animal they had seen.”

71 Stalker went on to report Campbell’s detailed claim that “one afternoon a short time ago he saw a creature raise its head and body from the loch, pause, moving its head—a small head on a long neck—rapidly from side to side, apparently listening…. While it was above water, he said, he could see the swirl made by each movement of its limbs, and the creature seemed to him to be fully 30 feet in length.”

72 This was, Stalker admitted, “a description which, to anyone who is at all sceptical, must appear to be very fantastic.” Skepticism was, we know now, entirely appropriate: Campbell retracted his story just days after Stalker publicized it! In a letter, Campbell explained that his spectacular 30-foot plesiosaur was just a group of ordinary waterbirds:

I discovered that what I took to be the Monster was nothing more than a few cormorants, and what seemed to be the head was a cormorant standing in the water and flapping its wings as they often do. The other cormorants, which were strung out in a line behind the leading bird, looked in the poor light and at first glance just like the body or humps of the Monster, as it has been described by various witnesses. But the most important thing was, that owing to the uncertain light the bodies were magnified out of all proportion to their proper size.

73Campbell’s role in the development of the Nessie legend was absolutely pivotal, but it soon descended into farce. Having admitted that the long-necked creature “fully 30 feet in length,” with its head held “fully 5 feet above the water,” was just a flock of cormorants (

figure 4.7), Campbell then went on in 1934 to claim a nearly identical sighting of a creature “30 ft. long” with a “swanlike neck reached six feet or so above the water”!

74 By itself, the sheer implausibility of this coincidence seems to disqualify Campbell’s testimony (and, by extension, all later plesiosaur sightings following his example) from serious consideration. But Campbell was not done: he eventually claimed a whopping eighteen sightings of the Loch Ness monster—often close up and sometimes of multiple creatures at one time. (In one of these entertaining adventure tales, his rowboat was lifted into the air on the monster’s back!)

75

Figure 4.7 Waterbirds, such as the plesiosaur-like cormorant, are a frequent source of false-positive sightings of cryptids. (©

Stockphoto.com/Jesús David Carballo Prieto)

We will return to the “plesiosaur hypothesis” later in this chapter. For now, we should pause to discuss the variability of eyewitness descriptions of the monster. “It seems quite clear, from the inquiries which I made between Inverness and Fort Augustus,” wrote Stalker, “that the many observers … are divided, broadly-speaking, into two sections.” On the one hand, there were those “who have seen a long greyish-black shape, evidently the back of a creature”; on the other, “there are those who have … described its head and neck and form as resembling a plesiosaur.”

76 In dividing witnesses into these two camps, Stalker both captured and dramatically understated this critical problem. As F. W. Memory, writing in the

Daily Mail, explained, “Hardly two descriptions tallied, and the monster took on both curious and fantastic shapes—long neck, short neck … one hump, two humps, even eight humps, and no humps at all! In fact, it rivals the most versatile quick-change artist of the vaudeville stage in the appearances it was able to assume between one viewing and another.”

77This variability of description leads researchers in radically divergent directions. If it is true that “the most striking feature about the Loch Ness ‘monster’—one which differentiates it from all other known living creatures—is a very long and slender neck, capable of being elevated very considerably above the water-level,”

78 as Gould concluded, then this leads the investigation in one direction. If, instead, the creature has “a massive bull-like head set on a very thick neck, not unlike that of a seal or sea lion,”

79 then the search takes an entirely different turn.

MONEY AND THE MONSTER

The commercial potential of the Loch Ness monster was obvious from the first—so obvious, indeed, that the Scottish Travel Association found it necessary to issue a denial: “[C]ontrary to rumours which are circulating, the Loch Ness ‘monster’ was not ‘invented’ by this Association as a means of publicity for bringing people to Scotland.”

80 Yet, such is Nessie’s value as an attraction that rumors of deliberate tourism-related fraud continue to circulate. (It seems that even Joseph Goebbels, the Minister of Propaganda in Nazi Germany, argued that Nessie was a hoax created by British tourism agencies.)

81There seems little need to conjure a central conspiracy when good humor, expectation, and simple human error could so easily provide ample fuel to spark a monster myth. The Nessie legend seems to have emerged in a sporadic, haphazard, and organic manner, with free enterprise simply seizing the opportunity. And what an opportunity it was! As the Daily Express explained in December 1933:

It’s an industry. It is Scotland’s answer to the Taj Mahal, New York Empire State Building, Carnera, and Ripley, believe it or not. Many newspapers in many countries are doing all they can for it. Scotland is in the front-page news day by day…. When the winter sun pales on the Mediterranean the Riviera has no attraction left. Loch Ness can defy all weather, seasons, ages with this fellow. He’s a monster advertisement—whether he’s there or not.

82Travel companies leaped into the Nessie industry, aggressively promoting commercial train and bus tour packages.

83 Loch-side bus traffic became so excessive in 1934 that special safety rules had to be introduced.

84 And while Nessie brought crowds of visitors to Scotland, the monster could also be exported as popular entertainment. In addition to appearances on radio programs and in comic strips, Nessie splashed immediately onto the silver screen. For example, a British Pathé variety short presented a pop song called “I’m the Monster of Loch Ness” in January 1934.

85 Amazingly, “a new ‘talkie’” feature film,

The Secret of the Loch, was announced, shot, and released before the end of that year.

86Nessie was put to work as a sales monster as well. Advertisers raced to print Nessie-themed campaigns for consumer products from mustard to floor polish to breakfast cereal.

87 Nessie merchandising also exploded immediately. In January 1934, a parade featuring a 17-foot-long monster escorted by bagpipers ushered three sizes of a cuddly velveteen toy called Sandy, the Loch Ness Monster, into Selfridges, a posh department store.

88 A series of large advertisements and cash contests urged children to “Join the Monster Club” by purchasing a wooden puzzle toy called Archibald: The Loch Ness Monster.

89 Rubber beach toys were rushed into production in anticipation of the 1934 tourist season.

90The humor of the Nessie industry was not lost on commentators. As one headline put it, “Monster Bobs Up Again … Hotels Doing Fine.”

91 Another noted, “There have, of course, been unworthy suggestions that, as a major and unique tourist attraction, she is being very strictly preserved from any undue scientific de-bunking, by those who recognize her value as an invisible export.”

92A PARADE OF PHOTOGRAPHS

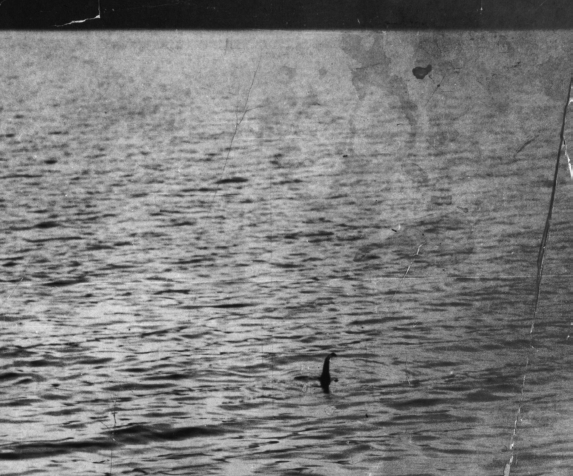

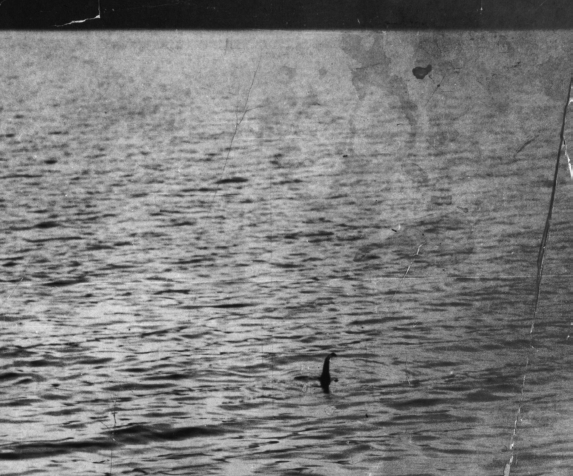

The Hugh Gray Photograph

The era of Loch Ness monster photography began in November 1933, when a British Aluminium Company employee named Hugh Gray was walking home from church along Loch Ness. Spotting the monster close to the shore, Gray apparently took five photographs, four of which showed nothing.

93 But the fifth photo showed—something wiggly? Or maybe not?

When Rupert Gould wrote that Gray’s photo, “although indefinite, is both interesting and undoubtedly genuine,” he rather understated the “indefinite” part.

94 The alleged monster photo is genuinely terrible (

figure 4.8). Its status as the first photograph of Nessie makes it worth mentioning, but it could show anything. To appreciate the true ambiguity of this photograph, consider that at least one book has printed it upside down.

95 Some researchers wisely refuse to argue on the basis of the photo. “I believe the picture is probably a genuine photograph of one of the aquatic animals in Loch Ness,” said Roy Mackal (on the strength of Gray’s verbal testimony). “However, objectively, nothing decisive can be derived from this picture. There is no apparent basis for determining which is front or back, and any such decisions must depend largely on what preconceptions one may have.”

96

Figure 4.8 The first photograph alleged to depict the Loch Ness monster, taken by Hugh Gray in November 1933. (Reproduced by permission of Fortean Picture Library, Ruthin, Wales)

While no source can claim any reliable insight into the identity of Gray’s monster, I confess that I can see only one thing: a yellow Labrador retriever, swimming toward the photographer. Once this interpretation was pointed out to me,

97 I found it impossible to un-see it. However, I cannot remotely prove that the photo depicts a dog, and this interpretation has been critiqued as pareidolia (the human tendency to perceive bogus patterns—especially faces—in random noise). At the same time, neither can anyone else prove anything on the basis of this picture. In and of itself, Gray’s photograph has negligible evidential value.

Is there circumstantial evidence that could shed light on the matter? Perhaps. One reason for suspicion is that Gray reported at least six Nessie sightings,

98 of which his photo was the second.

99 When one witness announces multiple, even habitual, sightings of an elusive cryptid, I regard this as a huge red flag. Think of the millions of people who have visited Loch Ness, the thousands who live and work around it, and the organized observation campaigns that have failed to catch any glimpse of the monster. Yet, inexplicably, certain names turn up repeatedly in the Loch Ness sighting record. Of these witnesses, some have admitted to misidentification errors (Alex Campbell disavowed at least one of his eighteen sightings), while others have been caught cheating. For example, Nessie researcher Frank Searle produced an absurdly lucky streak of photographs before his fellow monster hunters proved that he was a hoaxer. (Some of his fake photos showed parts of a painted sauropod dinosaur blatantly cut out of a postcard.) After Searle was exposed, tensions rose to such a point that he allegedly firebombed a Loch Ness and Morar Project expedition. No one was hurt, and he soon left the area.

100 Today, Searle is universally remembered as a fraud.

For his part, Gray also sighted Nessie with suspicious frequency—and there is a seemingly implausible convenience to his photograph as well. Walking home after church, he said, “I had hardly sat down on the bank when an object of considerable dimensions rose out of the loch two hundred yards away. I immediately got my camera into position and snapped the object which was two or three feet above the surface of the water.”

101 Then, having successfully captured, at close range, history’s first photograph of the Loch Ness monster, Gray apparently went home and left the film in a drawer for almost three weeks.

102Was Gray’s photograph a hoax? I don’t know, but the smart money would not bet any other way.

March of the Hippopotamus

In December 1933, the

Daily Mail dispatched a special investigator to Loch Ness to get to the bottom of the mystery: “big-game hunter” Marmaduke Wetherell. Almost as soon as he arrived, Wetherell announced that he had discovered (and cast in plaster) the monster’s footprints on the shore of the loch. This struck some observers as a little convenient. “I am aware,” Wetherell acknowledged in an interview, “that it is suggested that I have had phenomenal luck in finding such definite traces in two days, although others have failed after a long search.”

103 Still, it was an astonishing find. In a BBC interview (produced, as it happened, by Peter Fleming, the brother of the creator of James Bond),

104 Wetherell said, “You may imagine my great surprise when on a small patch of loose earth I found fresh spoor, or footprints, about nine inches wide, of a four-toed animal. It prints were very much like those of the hippo.”

105Recalling this interview, Fleming described Wetherell and his assistant as “transparent rogues” whose “account of their discoveries carried little conviction.” Wetherell struck Fleming as “a dense, fruity, pachydermatous man in pepper-and-salt tweeds.”

106 These ad hominem attacks are in keeping with the portrait painted by researchers David Martin and Alastair Boyd. Wetherell was “an eccentric, a likeable rogue, a master of hoaxes, a vain attention seeker.” They found that he was not, however, “as the literature would have it, merely a big-game hunter. He was primarily a film director and actor.”

107 A mid-level showman, in short—and, with his monster footprints, a showman in the spotlight.

But it was not to last. The cast of the footprints was sent to the Natural History Museum in London, where it was studied by the head of the Department of Zoology and other scientists. These experts identified it easily enough: “We are unable to find any significant difference between these impressions and those made by the foot of a hippopotamus.” Nor did the prints of the monster match those of a living hippo that the museum had cast at the zoo for comparison. Wetherell’s tracks had been made by using a “dried mounted specimen.”

108 The footprints were a hoax, and Wetherall himself had offered the first hint.

In 1999, Martin and Boyd revealed, “Marmaduke Wetherell planted the hippo footprints himself” by using a “silver cigarette ashtray mounted in a hippopotamus foot.” The ashtray still exists, in the possession of Wetherell’s grandson Peter.

109Saying that he “could not account” for the fake footprints, Wetherell soon announced that the Loch Ness monster was a seal—and left the area. But his role in the Nessie story was far from over.

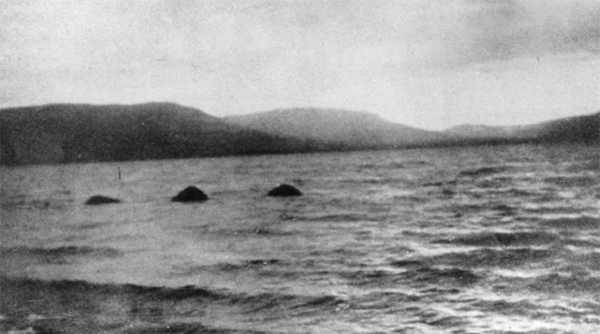

The Surgeon’s Photograph

On April 21, 1934, the

Daily Mail published a stunning new photograph of the Loch Ness monster, allegedly taken by a gynecologist named Robert Kenneth Wilson. Referred to today as the Surgeon’s Photograph, this is unquestionably the most famous Nessie image ever produced (and an icon for cryptozoology in general) (

figure 4.9).

110 With a few exceptions, Roy Mackal wrote in 1976, “every student of the Loch Ness phenomena … has accepted this picture as depicting the head-neck of a large animal in Loch Ness.”

111Figure 4.9 The hauntingly indistinct, close-cropped standard version of the Surgeon’s Photograph, taken in April 1934. (Reproduced by permission of Fortean Picture Library, Ruthin, Wales)

Contemporary critics were quick to propose alternative explanations. “I got a copy of the original from the

Times,” wrote legendary paleontological explorer Roy Chapman Andrews, “and it showed just what I expected—the dorsal fin of a killer whale.”

112 Others suggested, plausibly enough, that the photograph depicted a diving otter or waterfowl. However, it is now known that the photograph was a hoax. In 1975, the

Sunday Telegraph printed a short article in which Ian Wetherell, the sixty-three-year-old son of Nessie hippo-foot hoaxer Marmaduke Wetherell, revealed that the Surgeon’s Photograph was actually another Wetherell family hoax, created by using a small model monster built around a toy submarine: “So my father said, ‘All right, we’ll give them their monster.’ I remember that we drove up to Scotland…. I had the camera, which was a Leica, and still rather a novelty then…. We found an inlet where the tiny ripples would look like full size waves out of the loch, and with the actual scenery in the background…. I took about five shots with the Leica … and that was that.”

113 After the photo shoot with the model, Marmaduke Wetherell handed off the film to Maurice Chambers, a collaborator who passed it to Wilson, who submitted it to the newspaper—and history was made.

Strangely, Ian Wetherell’s public confession in 1975 remained little known for many years.

114 In 1990, Adrian Shine dug out the forgotten article and set researchers David Martin and Alastair Boyd on the trail. By this time, both Marmaduke and Ian Wetherell were dead, but the search led them to Marmaduke Wetherell’s stepson, an elderly gentleman named Christian Spurling. Spurling confirmed Ian Wetherell’s claim: “It’s not a genuine photograph. It’s a load of codswallop and always has been.”

115 Spurling and Ian Wetherell had built the monster model together.

For his part, Wilson was always cagey about “his” famous picture. He hinted to researchers that “there is a slight doubt or suspicion as to the authenticity of the photograph.”

116 He insisted, “I have never claimed that this photograph depicts the so-called ‘Monster.’ … In fact I am unconvinced and intend to remain so.”

117 Moreover, some witnesses have said that Wilson had confessed to the hoax. One such was a friend of Wilson’s named Major Egginton, who had served under Wilson in the military. In 1970, Egginton told a young Nessie researcher named Nicholas Witchell,

I always recall the occasion when in 1940 my late Colonel (of the Gunners) Lt. Col. R. K. Wilson, who was before the War a Harley Street specialist, told three of us, quietly in the mess how he and a friend had hoaxed the local inhabitants of Loch Ness. His friend with whom he used to fish the loch from time to time … had apparently superimposed a model of a monster on the plate…. [T]he resulting publicity according to “R. K.” so scared them that it was kept very quiet.

118The “friend with whom he used to fish” was Chambers, the link between Wilson and Wetherell. Wilson’s relatives confirmed that Chambers and Wilson used to hunt together in Scotland,

119 and Witchell related that the two men leased a “wild-fowl shoot … close to Inverness.”

120 (Egginton’s widow likewise confirmed that Wilson “used to fish and shoot up in Scotland.”)

121 Egginton’s statement that Wilson said his “friend” (Chambers) had supplied the Surgeon’s Photograph as a ready-made image independently confirms the first-person testimony from Ian Wetherell and Christian Spurling. And, as Egginton emphasized, “The story I have told you was that given to me by Lt. Col. Wilson and not second hand.”

122There is also a great deal of tantalizing hearsay evidence regarding skepticism on the part of Wilson’s friends and family. Researcher Maurice Burton was told that “everyone” in a London club to which Wilson had belonged “knew the picture was a hoax.” Following up this lead, Burton wrote to a friend of Wilson, who “evaded my question but answered rather in the nodis-as-good-as-a-wink manner.”

123 According to Wilson’s sister-in-law, Wilson’s younger son “was very skeptical over the whole Loch Ness question, and he told a cousin it was a hoax.”

124 A friend of Wilson’s surviving son related that “from all accounts R. K. was a great prankster with a wicked sense of humour…. R. K. didn’t discuss the photo with his family…. [T]he generally held opinion amongst the family is they are sure that it’s probably a fake.”

125 Finally, Egginton’s widow recalled that Wilson had told the hoax story for years. “Everybody knew,” she said, “we knew up there. We all laughed about it, we have done so for years. We knew the story, my husband did, I did too. I find it incredible that the hoax lasted so long.”

126

Figure 4.10 Less tightly cropped versions of the Surgeon’s Photograph reveal the small size of the model of the monster used to perpetrate the hoax. (Reproduced by permission of Fortean Picture Library, Ruthin, Wales)

The case for the photograph’s being a hoax is very strong, while that for its being real amounts, essentially, to the impression that the silhouette resembles a monster. Yet, even this gut test fails badly. Looking at the scale of the ripples in the photo—especially in the recently publicized less tightly cropped version—the image seems obviously to depict something very small (

figure 4.10). As early as 1960, commentators assessed the object as under 1 foot in height, based on the ripple size. Today, Martin and Boyd explain, “Avid believers in the authenticity of the photograph centre their faith around [Paul] LeBlond and [M. J.] Collins’ more recent size determination…. Using the wind waves visible in the uncropped photograph to deduce a scale for the object in the center, they concluded this to be about 1.2 m [4 feet] in height.”

127 Addressing this embarrassingly small upper-range estimate, Ronald Binns retorted, “Even if the object was 1.2 meters high, so what?”

128 That scale is obviously consistent with a small model, not with a dinosaur-size monster.

Despite all the evidence to the contrary, this vague, evocative image remains the most powerful icon for Nessie and continues to shape the public imagination. Such is its power. But serious students of the mystery have little choice but to face the historical truth: the Surgeon’s Photograph is a known fake.

The Lachlan Stuart Photograph

World War II suppressed interest in the Loch Ness monster, and sightings fell off correspondingly. But interest began to revive in the 1950s. Key to that cryptozoological renaissance was a new photograph, taken by a forester named Lachlan Stuart (

figure 4.11). Among dedicated Nessie researchers, it became arguably as influential as the Surgeon’s Photograph. And, like that famous icon, Lachlan Stuart’s photo was a hoax.

According to Stuart, he got up early on July 14, 1951, to milk his cow. Spotting something strange out his window, he shouted for his wife and house-guest, and grabbed his camera. Running to the shore of the loch, they watched three humps and “a long thin neck and a head about the size and shape of a sheep’s head. The head and neck kept bobbing down into the water.” As the creature cruised—astonishingly, just 40 yards offshore—Stuart snapped his famous photo. He developed the film on his lunch break, and Nessie researcher Constance Whyte saw the negative and photo later the same day.

129I must stop here to say that this photograph bothered me from the first moment I saw it. Even as a monster-loving child, I felt that the weirdly angular humps did not look like as though they belonged to an animal. They also conflicted badly with the plesiosaur I understood Nessie to be. (Of course, humps-in-a-line sightings have always composed a significant subset of reports.) But the photo was received as a major breakthrough in the 1950s, partly on the strength of Stuart’s apparent sincerity. “I could not,” Whyte raved, “put forward this photograph with more confidence if I had taken it myself.”

130 This confidence was misplaced. As researcher Nicholas Witchell learned, “Lachlan Stuart’s photograph, of three angular ‘humps’ a short distance offshore, was a hoax: Mr. Stuart’s account of what happened, a fabrication. He evidently intended no great mischief, and was both surprised and amused that his picture—in reality of three partly submerged bales of hay covered in tarpaulin—should have been taken seriously.” Shortly after admitting to having set up the hoax, Stuart took another Loch Ness local (author Richard Frere) to see the props. They were “hidden in a clump of bushes.”

131

Figure 4.11 The photograph taken by Lachlan Stuart in July 1951. (Reproduced by permission of Fortean Picture Library, Ruthin, Wales)

The revelation that the photograph is a crude fake may not seem surprising. It looks like a crude fake. Yet Ronald Binns argues that hindsight obscures the photo’s historical influence. Consider that in 1976, the scientific director of the Loch Ness Investigation Bureau characterized Lachlan Stuart’s photo as “direct photographic evidence as to the probable shape of the central back region of the animal.”

132 Looking back, Binns reflects, “What has probably been lost sight of over the years is the impact which the Wilson and Stuart photographs had on monster-hunters back in the 1960s and 1970s. In those days we all firmly believed that they were genuine photographs and that the monster was indeed a very big animal with a long giraffe-like neck, capable of transforming itself into a three-humped object.”

133The Tim Dinsdale Film

If asked to point to the Loch Ness mystery’s equivalent to the Roger Patterson–Bob Gimlin film, which allegedly caught a glimpse of Bigfoot, most people would select the famous Surgeon’s Photograph. Loch Ness researchers probably would give a different, deeper answer: the Tim Dinsdale film. This little piece of black-and-white movie footage, shot in 1960, shows a tantalizingly indistinct, far-off blob moving on the surface of the lake. Nessie researchers find it compelling and evocative. As Roy Mackal, scientific director of the Loch Ness Investigation Bureau, explained, when all other evidence seemed unconvincing, “the one thing that would not go away was the Dinsdale film sequence. Although it was grainy in quality because of the great distance involved in the photography, I could not explain it, try as I would. It alone was sufficient for me.”

134Dinsdale was an engineer who developed a sudden and powerful fascination for Nessie, after reading a magazine article late one night in 1959:

I kept turning the story over in my mind, and, late that night in bed, fitfully asleep, I dreamt I walked the steep jutting shores of the loch, and peered down at inky waters—searching for the monster; waiting for it to burst from the depths just as I had read, and as the wan light of dawn filtered through the curtains, I awoke and knew that the imaginary search beginning so clearly in my dream had grown into fact.

135Reviewing the literature on the monster, Dinsdale hatched a very simple plan: he would drive to Loch Ness and film Nessie. And that, he soon reported, is exactly what he did. Indeed, Dinsdale spotted the monster just minutes after his first view of the loch: “Intrigued, I drove up closer … and then, incredibly, two or three hundred yards from shore, I saw two sinuous grey humps breaking the surface with seven or eight feet of clear water between each! I looked again, blinking my eyes—but there it remained as large as life, lolling on the surface!”

136 Alas, this was a false alarm. Upon closer examination through binoculars, the monster “turned out to be a floating tree-trunk after all.”

137 But the excitement of his vacation was just beginning. Four days later, after driving about, visiting authors and witnesses, and periodically stopping to observe the loch—bingo! The Loch Ness monster!

The light began to fail, and then, quite suddenly, looking down towards the mouth of the river Foyers, I thought I could see a violent disturbance—a churning of rough water, centering about what appeared to be two long black shadows, or shapes, rising and falling in the water! Without hesitation I focused the camera upon it and exposed twenty feet or so of film…. I went straight to bed quite sure of the fact that the Monster, or part of it at least, was nicely in the bag!

138Nor was Dinsdale’s luck, it seemed, exhausted. On the sixth day of his vacation, he filmed Nessie a second time! Coming over a hill,

I saw an object on the surface about two-thirds of the way across the loch…. I dropped my binoculars, and turned to the camera, and with deliberate and icy control, started to film; pressing the button, firing long steady bursts of film like a machine gunner…. I could see the Monster through the optical camera sight … as it swam away across the loch it changed course, leaving a glassy zigzag wake; and then it slowly began to submerge.

139Flush with the knowledge that he and his camera had “reached out across a thousand yards, and more, to grasp the Monster by the tail,”

140 Dinsdale returned home. When his motion-picture film was developed, however, he discovered with disappointment that his first sequence of “Nessie” footage was “no more than the wash and swirl of waves around a hidden shoal of rocks; caused by a sudden squall of wind…. I had in fact been fooled completely!”

141Two of his three “monster” sightings had proved to be simple misidentification errors. But what of the last? Viewing the remaining film sequence, Dinsdale was convinced that he had truly captured proof of the existence of the Loch Ness monster—and felt that science would soon agree. Unfortunately, even he had to concede that this “shabby little black and white image that traced its way across the screen” looked fairly unimpressive.

142 Shot at extremely long range, the film depicts an indistinct blob moving on the surface of the water a mile in the distance. Not surprisingly, it was greeted with indifference by the scientists whom Dinsdale approached. However, television audiences proved much more receptive. Dinsdale’s television debut was covered by major newspapers as far away as Chicago,

143 securing him a Nessie book deal (the first of several) and launching his new career as a Nessie researcher, author, and lecturer.

144 Dinsdale became a monster celebrity. (He even appeared on

The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson during a lecture tour of the United States in 1972—a six-week “whirlwind of appointments, interviews and rehearsals for TV, radio and the newspapers.”)

145But what exactly did Dinsdale film? Certainly, his footage depicts a moving object on the surface of the loch; beyond that, it’s difficult to say. This “fuzzy, distant, inconclusive” film, as the

Boston Globe described it,

146 lends itself to various highly uncertain interpretations. For example, consider the conclusion of the Royal Air Force photographic experts from the Joint Air Reconnaissance Intelligence Centre (JARIC) who studied the film in 1966. Dinsdale felt that the investigators had “vindicated” his film,

147 but this is a significant overstatement. In fact, they found that the appearance and speed of the blob in the film are consistent with those of a motorboat (“a power boat hull with planing hull”). However, the report continued, if the blob were a motorboat, this “would scarcely be missed by an observer.” That is, because Dinsdale

said that it was not a boat, “it probably is an animate object.”

148 The assumption that Dinsdale would have recognized a distant motorboat is extremely shaky. After all, Dinsdale mistook other inanimate objects (first a log, and then some rocks) for the Loch Ness monster two other times during the same week!

Essentially, the experts at JARIC found that Dinsdale’s blob is consistent with a monster—or with a boat. This conclusion is not terribly helpful. Since the film was analyzed, various authors, experts, and television productions have attempted to enhance the film, with results supporting (variously) either a monster or a boat. For example, pro-Nessie author Henry Bauer asked “a faculty member in the Computer Science Department at Virginia Tech … [to] scan a number of frames at higher resolution and to examine them under various types of enhancing techniques”; from this, he concluded that the film does not show a boat.

149 By contrast, Adrian Shine found frames of Dinsdale’s film that suggest a manned boat. When he asked members of the original JARIC team to have another look at the film in 2005, they found that the object “has the overall appearance of a small craft with a feature at the extreme rear, consistent with the position of a helmsman.”

150The Dinsdale film has quite a bit in common with the Patterson–Gimlin film. Both are influential among core proponents. Both filmmakers took a short trip with the intention of filming a famous cryptid, and then immediately did. And both films ultimately frustrate the search for answers. Could Dinsdale really have filmed a monster? The film’s mysterious blob cannot tell us—not for sure.

Nonetheless, there are circumstantial hints that suggest a more prosaic explanation. For example, Dinsdale’s blob travels in plain sight of a motor vehicle on a road just 100 yards away. The vehicle’s driver and the “monster” would have had clear views of each other, but neither slows or reacts to this close encounter. To critic Ronald Binns, “The fact that the driver just kept going suggests that this was because the object passing by was something perfectly ordinary—a motor boat.”

151As well, there are some red flags about Dinsdale himself. Although he had a reputation among critics and friends alike as “a man of great sincerity,”

152 he sometimes let his imagination run away with him, as it did during the two false-positive Nessie sightings he made in the days immediately before he shot his famous film. Given those misidentification errors, it is hard to know how to interpret his spectacular claim of a later, close-up sighting in 1971:

I glanced to starboard and instantly recognized a shape I had seen so often in a photograph, the famous “Surgeon’s Photograph” of 1934—but it was alive and muscular! Incredulous, I stood for a moment without moving. All I could do was stare. Then I saw the neck-like object whip back underwater, only to reappear briefly, then go down in a boil of white foam. There was a battery of five cameras within inches of my right hand, but I made no move towards them.

153Inexplicably, his later books reduce this close encounter to a sort of aside or footnote: “The strangest radio interview I had was in 1971 at Inverness: moments after seeing the Monster’s head and neck from [a boat] I had switched on a tape recorder to make a commentary, and BBC radio wanted to use it for a science programme.” After barely mentioning having seen the Loch Ness monster, Dinsdale spends the next two paragraphs on a pointless anecdote about the “peculiar experience” of technical glitches for an interview.

154 What gives?

Dinsdale was also given to flights of supernatural fancy. He was, for example, “conscious of some dark influence” at one secluded beach where he often staked out the monster:

Four of the five expeditions based there resulted in illness or injury, or accident of a most unpleasant nature, and I became aware of some strange influence which seemed to be malevolent…. I do subscribe to the belief that … purely psychic influence can have a physical effect on people, and sometimes on material objects. I have witnessed such phenomena, which absolutely defy the physical laws as we understand them.

155In the same vein, he told the

Washington Post that he sometimes experienced “dread” while on his boat on the loch: “That’s the only word I have to describe it. Dread. I knew I wasn’t alone. I knew it.”