Table 1: Ontology in Thomas Pynchon’s Bleeding Edge (2013). Courtesy of Amy J. Elias.

REALIST ONTOLOGY IN WILLIAM GIBSON’S THE PERIPHERAL

One of the most important keywords in arts theory and criticism today is “ontology.” From AI experimentation to climate fiction to posthumanist ethics to object-oriented ontology, we in the arts and humanities are rethinking our relations to reality, as well as how that reality might be understood in new knowledge paradigms that accommodate burgeoning technologies and the environmental effects of the Anthropocene. 1 William Gibson’s novels have always raised ontological questions, such as “What is a world?” Indeed, critics analyzing the Sprawl and Blue Ant trilogies focus attention on the nature of hyperreality and the relation between worlds inside and outside of the matrix (cyberspace versus “meat space,” human versus posthuman technologies, etc.). Often studies examine how affordances and hierarchies of power in the worlds reflect and inflect the perceptions and ethics of the humans who reside in them; differences between worlds are often configured as an aesthetic relation, the world of cyberspace mimicking and revealing (even as it often displaces) the Baudrillardian “false reality” of the aestheticized social space determined by late capitalism. 2 Defining worlds or types of being in these novels is linked to political, phenomenological, or epistemological analysis: worlds are explained as ways of knowing—that is, in terms of human perception and consciousness or the unique landscapes of merged human–machine cognition. 3

The appearance of The Peripheral in 2014, however, forces consideration of ontological questions as such and demands a reconsideration of the effects of a realist ontology on a novel’s ethical and social commitments. The novel is the first of what seems to be Gibson’s new “postapocalypse” cyberspace trilogy (the second in the series, Agency , appeared in 2020) that concerns the intersections of time travel and artificial intelligence. Wrecked, postapocalypse, or post–World War III societies have appeared in Gibson’s work before, but he always maintained that his works are more about his present, the time of the novel’s writing, than they are any future the novel might depict. It is significant, perhaps, that this novel, which creates a science fiction realist ontology new to Gibson’s fiction, appears at the same moment that a real-world climate crisis and an intellectual zeitgeist about apocalypse and ontologies is burgeoning on the world horizon.

Gibson’s Ontologies

While Gibson’s first cyberspace texts in the Sprawl trilogy were concerned with how technology fundamentally alters near-future space (cyberspace, the Sprawl, the Well, Chiba City, Villa Straylight, London), The Peripheral (and, it seems, Agency ) focuses on how technology fundamentally alters future time. The Sprawl trilogy presents infinity as an interior territory in cyberspace; it is something console cowboys navigate, something that Case and Angie can visually apprehend. In contrast, The Peripheral exteriorizes infinity in the vast space-time of the material universe. It plays with a generalized version of multiverse theories that sometimes look like Hugh Everett’s 1957 many-worlds interpretation in quantum mechanics (which claims that there are many parallel, noninteracting worlds that exist at the same space and time as our own and are generated each time a quantum measurement is made) or Wiseman’s and Hall’s idea of “many interacting worlds,” in which universes can interact (in that all quantum phenomena arise from a universal force of repulsion between similar worlds which tends to make them more dissimilar). 4

Like most philosophers and literary critics, Gibson does not get mired in the science. He has noted in interviews that The Peripheral is his attempt at hardcore science fiction, which since at least H. G. Wells’s The Time Machine has been obsessed with time-travel narratives as scientific problems, logical paradoxes, and opportunities for social commentary. 5 The Peripheral explores the ethical and social meaning of accessing multiple worlds in a multiverse—of having power to manipulate space-time—and the role of new technologies, particularly artificial intelligence, in reshaping our relationship to time and thus to one another. While typically the protagonists of time-travel fiction move backward in time (a safe choice for writers in some ways, because we know what happened in the past) or far into the future (allowing the construction of utopian or dystopian worlds that will never contradict the lived experience of their present or future readers), The Peripheral primarily tells the story of a move forward in time toward a not-so-distant future of the early twenty-second century. (According to characters in the novel, the future cannot connect with the past before 2023, so the world of “the past” in the novel is basically the reader’s own). The novel’s protagonist, Flynne Fisher, travels into a near future that results from the Jackpot—a cataclysmic series of linked events that eventually eradicates 80 percent of the world’s population within forty years and leaves the world to rich oligarchs (klepts) whose money has allowed them to escape the Jackpot’s most devastating effects. Gibson has noted that his model here was Bruce Sterling and Lewis Shiner’s story “Mozart in Mirrorshades,” in which characters also economically exploit the resources of an alternate continuum and (like the Borges stories that Gibson loves) the novel is an alternate reality book “more like forking paths.” 6

Although there are nods to Gibson’s present in the text (the presence of cronuts, a fictional allusion in the group Luke 4:5 to the deeply right-wing Westboro Baptist Church, etc.), there are also allusions to Gibson’s earlier books. Flynne’s online handle is “Easy Ice,” recollecting the Intrusion Countermeasures Electronics (ICE) popularized by Neuromancer ; like the Bridge trilogy, this novel sets up class conflict between the very rich and the working poor in the near future, with connectivity and actual wealth a marker of privilege. As in other novels in the Sprawl and Blue Ant trilogies, here the US South is a backdrop for some of the action. Most important, however, The Peripheral seems to continue the evolutionary development of AI that began in Neuromancer and continued through at least the Sprawl trilogy. This is what allows its unique realist ontology to emerge.

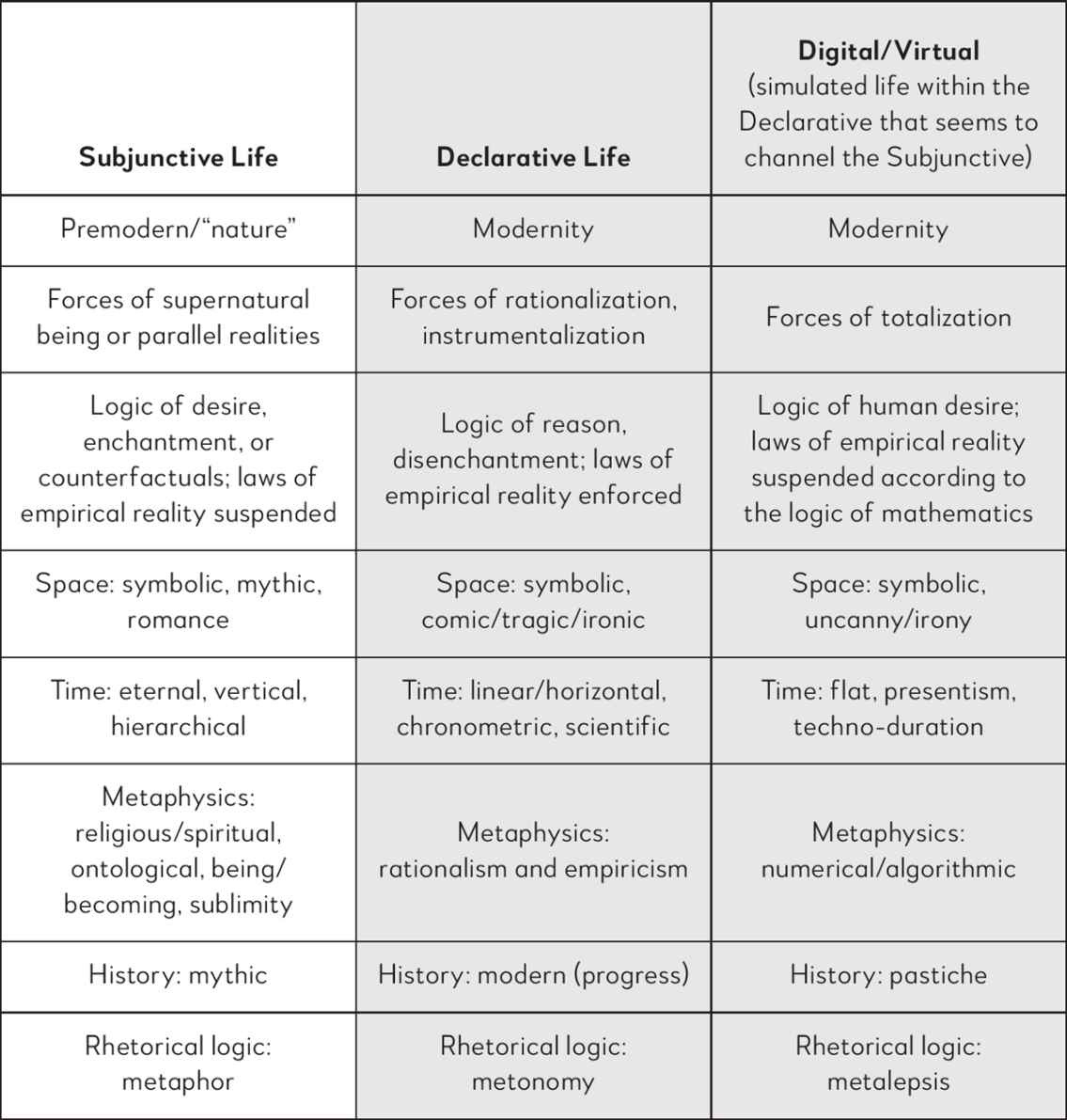

I’m going to take a brief detour here, because I have found it useful when thinking about Gibson’s ontologies to compare them to one set up by his peer, Thomas Pynchon, who constructs a two-tiered ontology of what he calls “the Declarative” and “the Subjunctive.” The Declarative reality is the space of modernity, what we might call rationalized consensus reality: the largely three-dimensional, “common-sense” time-space inhabited by “Western” humans and largely defined by their perceptive abilities and epistemological and hermeneutic philosophies. The Subjunctive is the space of the mythic or non-Western epistemology that exceeds Declarative reality. It has been described by literary criticism as the realm of the sublime, the realm of romance, or the realm of quantum possibility. In Pynchon’s work, it is represented in The Crying of Lot 49 as Maxwell’s Demon, in Gravity’s Rainbow as the Zone, in Mason & Dixon as the American Territory filled with mysterious energies not yet mapped by rationalized Royal Society science, and in Against the Day as the world of gothic and romance that is increasingly shut down by industrial capitalism’s rape of the natural world. 7 Often Pynchon opposes the Declarative and the Subjunctive as different ontological levels of being, but in his 2013 novel Bleeding Edge , he offers a third ontological sphere, the “Digital/Virtual.” 8 In the form of the “dark web,” this becomes a territory populated by hackers and other nonconformists—a new, metaleptic ontological level that erupts within the Declarative as a kind of eternal return to the Subjunctive, a fracturing of the Declarative’s rationalist and totalitarian control. As a result, in Bleeding Edge the Virtual seems salvational, displacing the Subjunctive to cyberspace and thereby plugging into cyberutopian theories of virtual anarchism and liberatory collective virtual action. One is reminded of McKenzie Wark’s observation: “The redemptive vision of second nature withered in both its Marxist and bourgeois forms. Yet . . . Redemption is always around the corner in virtual reality, hypertext, cyberspace, Web 2.0, mobile media, social networking, or the ‘cloud.’” 9

In Gibson’s novels, a similar kind of ontology is emerging, one that acknowledges a more nuanced understanding of AI’s strangeness and possibilities and that does not romanticize the virtual. This perspective is set up at the end of his first novel, when two important pieces of information are relayed to Henry Dorsett Case in his conversation with the newly merged Wintermute/Neuromancer AI. First, the AI tells him that “I am the matrix . . . the sum total of the works, the whole show,” and beyond any human imagining. This prompts Case to ask, “So what’s the score? How are things different? You running the world now? You God?” The AI replies, “Things aren’t different. Things are things.” 10 I would argue that the AI and Case are not really communicating here; they are talking past one another. The AI is alluding to a posthuman or transhuman way of understanding the world that Case cannot yet understand—one that forms the basis of the future world in The Peripheral .

What the transmogrified AI seems to imply at the end of Neuromancer is that it is plugging into a realist metaphysics in which “things are things” rather than projections of human logic, desire, or control. David Chambers notes that “Ontological realism is often traced to Quine . . . who held that we can determine what exists by seeing which entities are endorsed by our best scientific theory of the world. In recent years, the practice of ontology has often presupposed an ever-stronger ontological realism.” 11 As a metaphysical philosophy, realism generally has two aspects: a claim about existence (i.e., that some things like tables and rocks exist, as do their properties of roundness, hardness, color, etc.) and a claim about independence (such things exist and have their properties independent of anything anyone perceives, says, or believes about them). 12 The AI in Neuromancer is in fact located at the genesis of a world in which humans need play no part at all. Seen through the lens of posthumanist and object-oriented ontologies circulating in theory today, we might say that the AI is alluding to a realist ontology that conforms to the claims of object-oriented ontology and vitalist materialism:

1. Reality is not discourse nor a phenomenological projection. It is real. It is living, creative vitality, as are all objects in it. Correlationism is false. 13

2. All animate and inanimate things are equally things/objects. Anthropocentrism and biocentrism are false.

3. Philosophies that impose hierarchies on the real are false. Object-oriented ontology levels violent hierarchies (such as subject/object) and eliminates moralities imposed on being (such as Elect/Preterite).

4. Things resist cognitive mastery: things have “allure,” “vibratory intensity,” and immanent properties but are “withdrawn” from other objects, from presence. We cannot ever penetrate or fathom the full being of something else.

5. All object relations distort the things that are in relation; things can’t relate fully to each other’s thingness. 14

Readers see the development of the AI’s reality in the next books of the Sprawl trilogy. In Count Zero , Angie Mitchell interacts with the matrix through the “voodoo gods” who populate it. 15 Critics have discussed these entities as the result of a fracturing or implosion of Wintermute/Neuromancer, but I tend to read them in light of The Peripheral and see them as trickster figures (there is Legba, after all) that serve as intermediaries between ontological levels, between the world of the now-independent Wintermute/Neuromancer AI and the world of humans. After Count Zero , in Mona Lisa Overdrive , the moment when Wintermute merged with Neuromancer is characterized as “When It Changed.” 16 As Gary Westfahl notes, “Angie obtains information through casual conversations with ‘Continuity,’ an artificial intelligence that speaks like a person, while Kumiko is accompanied by a ‘ghost’—a computer-created personality taking the form of a hologram of a young man only she can see.” 17 By the time of Mona Lisa Overdrive , artificial intelligence is appearing at all ontological levels, but there seems an important distinction between those AI that operate in the human, “declarative” world and those that operate in their own cyberspace realm, which is fast becoming a space of the transhuman (the AI can re-create human consciousness there) and the algorithmic subjunctive (not inhabited by humans but embodying the “magic” humans associate with romance or mythology) (see Table 1 ).

In The Peripheral , the Wintermute/Neuromancer AI (whatever it may have evolved into at this point) is absent as a story actant, but it may still be present in the narrated world as an absent cause. It has become, in effect, a kind of hyperobject in Timothy Morton’s sense. 18 In this novel, the prophetic or mystical function is served by “the aunties,” a set of algorithms so sophisticated that they have assumed the status of oracles (often portrayed as female and, like computer consoles, portals through which beings from another realm spoke directly to people). Ainsley Lowbeer admits, “We have a great many, built up over decades. I doubt anyone today knows quite how they work, in any given instance.” 19 The aunties don’t seem to control the world of The Peripheral , but they seem central to it, as if acting as its steward or caretaker, a demythologized version of the voodoo gods of Count Zero .

The second important piece of information relayed to Case in his last conversation with Wintermute/Neuromancer is that the AI has moved into deep space-time. When the AIs merge, the new construct searches 1970s records of alien transmissions and finds “others”—particularly another AI in the Alpha Centauri star system with which it can communicate. The reality that the AI accesses is neither internal to the cyberspace that Case can access nor is completely external to it. It seems that this new AI consciousness can connect with cyberspaces of other worlds. As noted, The Peripheral may present the most evolved version of what is perhaps Wintermute/Neuromancer in the aunties or in the Chinese computer, which, Ned Beauman notes, has the ability to access “a sort of transtemporal Skype running on a mysterious Chinese server that accounts for those two eras becoming entangled in a single story.” 20 That “transtemporal Skype” is a connection that accesses space-time, much as Wintermute/Neuromancer accessed it earlier. If in Neuromancer Wintermute/Neuromancer gained access to cyberspace across vast, Real space (the AI “other” of the Alpha Centauri system existing simultaneously with Wintermute/Neuromancer), in The Peripheral some kind of AI (Wintermute/Neuromancer?) has gained access to cyberspace across Real time. Flynne can enter cyberspace and work a drone in the future; she can enter cyberspace and inhabit a future peripheral running software in the same space but not at the same time.

My point is twofold: first, that somehow there seems to be a connection between the merged Wintermute/Neuromancer of the first novels and a much-evolved version (linked to the mysterious Chinese computer) in The Peripheral , and second, that in The Peripheral , for the first time in Gibson’s fictional worlds, we access another ontological dimension, that of space-time itself. This new access to time puts cyberspace up against its own limits, for it is now not just an interface with Declarative reality (as it was, for instance, in Count Zero with the voodoo gods as intermediaries) but also, for the first time, with another reality on the other side of cyberspace, what I call “the Real.” The Real is the physical universe, governed by its own logics and thus outside the complete control of both humans and AI. The Real is revealed, not created, when the elite of the future start to time-travel into the past. The oligarchs in Wilf Netherton’s world, such as Lev Zubov, can buy telepresence access to the past but can’t change events in their own timeline, because as soon as they intervene in the past, time splits into a new “continua” or dimensional pathways called “stubs.” The Real is self-healing, and its logic is absolute, no matter how sophisticated the algorithms manipulating it. 21 In The Peripheral , Gibson uses a realist ontology in which things and states of being exist independently of human sense and/or perception—a metaphysical perspective that underlies object oriented ontology and “thing theory” as well as some forms of posthumanist ethics.

If the number of possible Real dimensions is infinite, then it doesn’t really matter ontologically what people like Lev Zubov or Ainsley Lowbeer do to the past worlds they visit—as it does, for example, in speculative time-travel novels such as Octavia Butler’s Kindred (1979). In The Peripheral , the Real is self-healing, and those interfering in the past are not endangering their own present; there will be an infinite number of other “pasts,” always new stubs produced.

But it does matter ethically. Positing the Real as a self-healing ontological dimension actually provokes the thorny ethical questions of this novel. As Gibson has noted in interviews, the ability of very rich people to use the past raises political questions about class privilege and ethical questions about colonial desire: rich people can “third-world” the past as if it were a labor force they can exploit (here, by hiring Flynne and her brother as security guards for a private party, though Flynne doesn’t realize she’s in this situation). Gibson has noted,

The concept of third-worlding the past, because the past you contact can’t become the past where you live, is from ‘Mozart in Mirrorshades’ by Bruce Sterling and Lewis Shiner. . . . It’s a brilliant story of colonialization. . . . I appropriated that, but what I realized almost before I appropriated it is the difference since 1984 when they wrote it, is that you don’t need to go there physically at all. . . . And I thought, okay, fair cop, this is the 21st century version of their model, if you can do it all virtually, and by telepresence. 22

Peripherals are the symbolic markers of this colonial attitude, bodies instrumentalized by power and evacuated of self-determination. Like eighteenth-century absent landlords in the New World, in The Peripheral the rich are immune from the consequences of their colonial intervention, since the realities they enter and exploit will never converge with their own. At one point in the story, Flynne’s brother, Burton, remarks, “Know what collateral damage is? . . . Think that’s us. . . . None of this is happening because any of us are who we are, what we are. Accident, or it started with one, and now we’ve got people who might as well be able to suspend basic laws of physics, or anyway finance, doing whatever it is they’re doing, whatever reason they’re doing it for.” 23 Netherton’s world is one where class is absolutely divided and the privileged run the world, while Flynne lives in a poverty-stricken rural landscape of Hefty Marts and drug economies. As Karin Kross has noted, “Among the worst, their power is inversely proportional to their concern for the lives that they damage in pursuit of more money, more power, or even just a little advantage over someone they don’t like.” 24

The ethical questions thus involve intervention and self-determination. First, those with the power to intervene in the lives (and futures) of others can do so for good or for ill. One can manipulate the stub to help it avoid the evils of one’s own present, which is actually what Lowbeer ends up doing. She cannot change the history of her time or her present, but she can help Flynne’s reality avoid the Jackpot and avoid ending up like her own oligarchic, surveillance society. Toward the end of the novel, Flynne worries that she, Lowbeer, and others are accumulating too much power, and Lowbeer responds that Flynne’s fear of power is precisely why she is the right person to hold it:

She’d told Ainsley, earlier . . . how she sometimes worried that they weren’t really doing more than just building their own version of the klept. Which Ainsley had said was not just a good thing, but an essential thing, for all of them to keep in mind. Because people who couldn’t imagine themselves capable of evil were at a major disadvantage in dealing with people who didn’t need to imagine, because they already were. She’d said it was always a mistake, to believe those people were different, special, infected with something that was inhuman, subhuman, fundamentally other. . . .

“All too human, dear,” Ainsley had said, her blue old eyes looking at the Thames, “and the moment we forget it, we’re lost.” 25

In addition, Lowbeer’s actions have effects in her own world. Meddling in the past is an action in her present, and it does actually change the trajectory of events in that present because it is an action that takes place there—as all of our actions in our lives affect the worlds we inhabit. Colonial imposition on another territory changes the home territory as much as it changes the past—here, the problem posed by “time travel” is that it will create obligations and ethical traps for those who intervene.

Table 2: Realist ontology in William Gibson’s The Peripheral (2014). Courtesy of Maria Alberto and Elizabeth Swanstrom.

As I’ve noted elsewhere, this sounds ethically better than it is. To pin one’s hopes of freedom on the continuing goodwill of another who has complete power over you and whose profit could be increased by your exploitation is a precarious act of faith and a stupid one. There is a strong tension in the novel between Gibson’s cyberpunk vision (which implies that this world is built on flows of power and allows for the critique of “third worlding”) and his humanism, for which the outcome of social structures depends on private, ethical decisions by individuals. At the end of The Peripheral , the “happy ending” to Flynne’s colonial situation depends not on revolution by the oppressed, by political liberalism that allows for self-determination, or by disconnection of the oppressed from their oppressors but solely on the goodwill of the colonial landlord and on being that landlord’s favorite. Gibson realized this immediately, expressing in interviews how uncomfortable he was with the fictional world’s “solution” and model of political quietism:

these guys had an immensely powerful—if possibly dangerously crazy—fairy godmother who altered their continuum, who has for some reason decided that she’s going to rake all of their chestnuts out of the fire, so that the world can’t go the horrible way it went in hers. And whatever else is going to happen, that’s not going to happen for us, you know? We’re going to have to find another way. We’re not going to luck into Lowbeer. . . . Well, also, how it’s set up for Flynne at the end—gave me the creeps! Really, its potential for not being good is really, really high. . . . I mean, she’s lovely, but what are they building there [in her pre-Jackpot reality]? It’s got all kind of weird third-world bad possibilities. 26

The new realist ontology throws us back to very old human problems. I believe that it also raises questions for us today that are often unacknowledged in theoretical discussions about realist ontology, object-oriented ontology, thing theory, and some versions of posthumanism. Essentially it raises the problem of relation, for though we may be in relation to all other things in a flat ontology, we still have the ability to act according to our abilities and enact power over others. In The Peripheral , we see how recognizing the Real throws us back to ourselves, in the coldness of the universe’s machinic logic.