CHAPTER IV

THE UPPER EXTREMITY

THIS, as has just been indicated, is made up of the arm joined to the trunk and neck by the region of the shoulder and armpit; of the forearm joined to the arm by the elbow; and of the hand joined to the forearm by the wrist.

When any limb is considered as a whole, it is at once seen to be more massive in the neighbourhood of the joints than in the parts between them, and in the upper parts than the lower. The reasons for this are (1) that in the regions of the joints the ends of the bones are larger than the shafts; (2) that muscles often take their origins in fleshy groups, while their insertions are usually tendinous and widely divergent; (3) that in the upper regions of the limbs the muscles have harder work to do, and are therefore larger, than the muscles lower down, which have less powerful but more delicate tasks to perform.

The Shoulder.

A description of this region must trespass upon and overlap that of the trunk and neck.

In the upper part of the back, and lying on each side of the vertebral column, is a flat eminence, roughly triangular in shape. It is formed by the scapula or shoulder-blade and the muscles which cover it (Figs. 19,20; Plates XI., XII., XIII., XVII., XXIV.).

The eminence is divided into two parts by a transverse furrow if the subject be well covered, or ridge if he be wasted, indicating the position of the spine of the scapula, which is continuous externally with the acromion process. The acromion is directed upwards and forwards from the spine to articulate with the clavicle, and so to form the point of the shoulder.

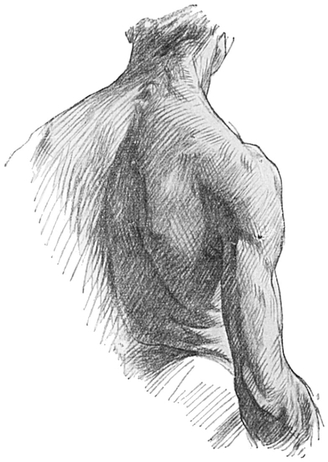

Fig. 19.—The Back of the Neck, Upper Part of Trunk. and Arm.

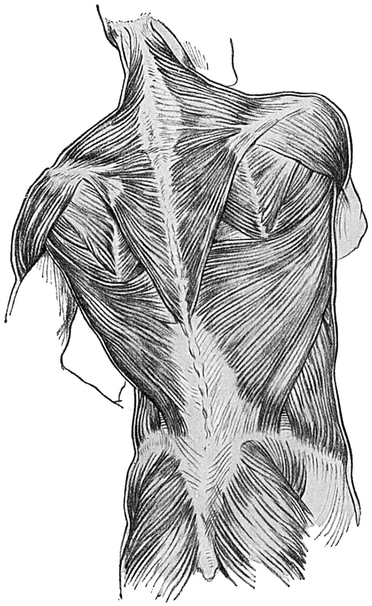

The part above the ridge or furrow is the smaller, lodges the supra-spinatus muscle, and is obscured by the flat Trapezius (Figs. 20 and 21) muscle as the latter passes to its insertion into the spine, acromion process, and posterior border of the outer third of the clavicle.

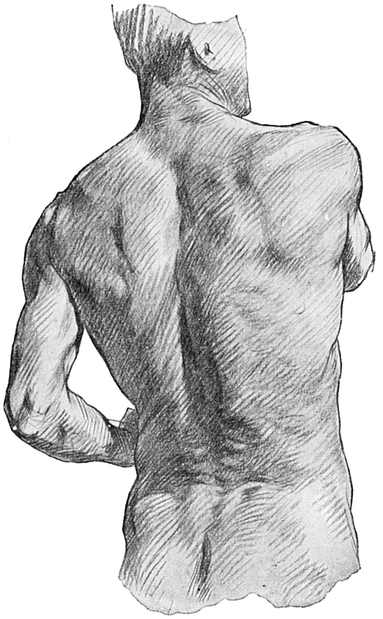

Fig. 20.—The Muscular Prominences on the Back of the Trunk, Buttock, and Neck.

The lower part of the trapezius also conceals, over somewhat less than its inner quarter, the infra-spinatus muscle, which, as its name implies, occupies the hollow in the scapula below its spine (Fig. 21).

Fig. 21.—The Muscles on the Back of the Trunk, Buttock,and Neck.

The inner limit of this flat triangular eminence is of course, the vertebral border of the scapula, which lies parallel with the vertebral column and is made more obvious by the subject placing the hand upon the opposite shoulder.

The rounded inferior angle of the eminence is concealed by the upper edge of the Latissimus dorsi (Fig. 21) on its way from the vertebral column to the upper part of the humerus. This inferior angle stands out when the subject places his hand behind his back.

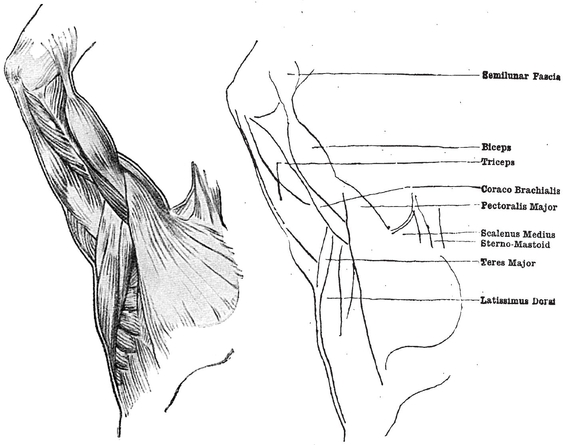

Fig. 22.—The Outer Side of the Upper Extremity.

The upper part of the infra-spinatus is obscured by the thick posterior border of the Deltoid muscle.

The posterior edge of the deltoid passes from the spine of the scapula near its root or inner part downwards and outwards, and, in the dependent position of the arm, also slightly forwards, to its humeral attachment.

It is owing to the great development of the trapezius and deltoid muscles that the position of the spine of the scapula is often actually indicated by a furrow in the living subject.

Fig. 23.—The Muscles of the Shoulder.

The lower angle of the scapula is directed downwards when the arm is hanging by the side or is raised to form a right angle, or less, with the side. If the angle formed by arm and side exceeds 90°, the inferior angle of the scapula moves outwards, owing to the rotation of the scapula upon the thorax around an antero - posterior axis, and it then becomes obvious in the back part of the armpit.

The Deltoid (Figs. 22 and 23) is the large fan-shaped muscle which covers the back, front, and outer side of the shoulder-joint. Together with the head of the humerus it determines the rounded form of the shoulder.

The curved and conspicuous clavicle is a useful landmark on the front of the upper part of the trunk, as it is subcutaneous and easily traced by eye or hand. It is joined to the sternum near the middle line of the root of the neck, and curves first forwards and outwards, then backwards and outwards, and finally a little forwards again to join the acromion process just above the shoulder-joint (Fig. 25).

Viewed from the front, the outer end of the clavicle is narrower, and is always situated on a higher plane than its inner end.

The remaining part of the deltoid—viz. its anterior part—arises from this thin anterior border of the outer third of the clavicle, also from its upper surface, and from the outer border of the acromion.

Fig. 24.—The Muscles of the Inner Surface of the Arm and of the Armpit

The anterior border of the deltoid is directed downwards, outwards, and slightly backwards as it converges upon the posterior border, the muscle being inserted by the apex of its delta into the middle of the outer surface of the shaft of the humerus.

The deltoid raises the arm at the shoulder, and it also has an important function in keeping the parts of the shoulder-joint in apposition.

Notice the tendinous intersections—four of origin and three of insertion—which groove the surface of the muscle longitudinally when in forcible action (Fig. 23, p. 78; Plate XX.).

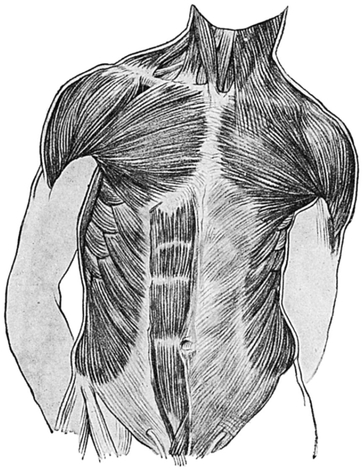

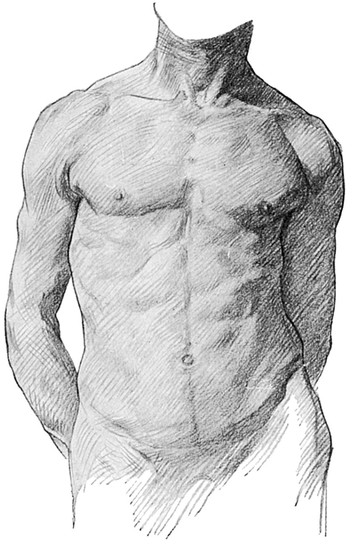

Fig. 25.—The Muscles on the Front of the Trunk and Neck.

The Pectoralis Major (Figs. 24 and 25).—Arising from the anterior surface of the inner half of the clavicle, the clavicular portion of this fan-shaped muscle passes outwards and slightly downwards to the upper part of the humerus.

The inclination of its upper border is less than that of the anterior border of the deltoid, so that the contiguous edges of these two muscles bound a narrow groove, which opens out above under the middle of the clavicle to form the infra-clavicular fossa.

In very thin persons the apex of the coracoid process may be seen projecting forwards in this fossa. It is situated below the anterior border of the clavicle in the outer part of the infra-. clavicular fossa, and is in close contiguity, if not in actual contact, with the under surface of the clavicle at the junction of its outer and middle thirds.

The large median cephalic vein (Fig. 26) runs in the groove between the deltoid and pectoralis major muscles, and disappears in the infra-clavicular fossa. It is especially noticeable when hard manual labour is being performed.

Fig. 26.—Muscles and Superficial Veins on Front of Arm and Elbow.

So far we have only spoken of the thick clavicular head of the pectoralis major. There is, however, another and more extensive but thinner fan-like origin from the sternum and rib cartilages, the fibres of which passing outwards, and with increasing degrees upwards, converge to add to the thick mass of muscle whose tendon is inserted into the humerus, under cover of the deltoid muscle.

The thick rounded lower border is directed from the bone of the seventh rib in its anterior part upwards and outwards to the humerus. About the middle of this border the inner part of the pectoralis minor may sometimes be seen as a slight ridge when the arm is raised above the head (Fig. 24).

Emerging from the under surface of the outer part of the pectoralis major is a ridge formed by the biceps and coraco-brachialis muscles (Fig. 24, p. 79). The pectoralis major in its extreme outer part passes under the anterior part of the deltoid.

The Axilla or armpit (Fig. 24).

This is a pyramidal space with its base directed downwards and outwards, and its apex directed upwards and inwards behind the clavicle. In the adult the skin covering its base bears long, coarse hairs.

The armpit is bounded in, front by the pectorales major and minor; behind, by the front of the scapula—or rather the sub-scapularis muscle, which arises therefrom, but is unimportant to the art student—and by the latissimus dorsi, which winds from behind forwards and outwards in a spiral manner round the lower portion of another muscle in this region named the teres major. Both of these muscles are attached to the humerus near the pectoralis major.

The pectoralis major from the front, and the latissimus dorsi from behind, thus converge upon the humerus, a small width only of which forms the narrow outer wall, while the wider inner wall of the unequally four-sided pyramidal armpit is formed by the thoracic wall covered by the Serratus magnus.

This important muscle arises by “digitations,” which are very obvious on the side of the chest when the muscle is in action (Figs. 24, 25, pp. 79, 80), from the nine upper ribs, half-way between the vertebral column and the sternum. Passing horizontally backwards in front of the scapula, the sheet which is constituted of these digitations is attached to the front of its inner or vertebral border.

Fig. 27.—The Muscular Prominences on the Front of the Trunk and Neck.

The muscle is brought into use when the upper limb is outstretched, because it fixes the scapula, and so gives the muscles which arise from the latter a fixed origin from which to act.

The Coraco-brachialis muscle lies on the inner side of the short head of the Biceps. It passes from above downwards on the outer wall of the armpit (Fig. 24).

The Arm denotes anatomically only that part of the subject which extends from the shoulder to the elbow (Figs. 4, p. 39; 19, p. 74; 22, p. 77).

The two last-mentioned muscles form a distinct ridge on the front of the limb, which is more prominent when the arm is lifted up from the side, and which is seen emerging from under cover of the outer part of the pectoralis major.

The coraco-brachialis (Fig. 24, p.79) terminates half-way down the arm, where it is inserted into the humerus.

Fig. 28.—The Front and Inner Side of the Upper Extremity.

The short head of the Biceps joins with the long head, which also emerges from underneath the pectoralis major, to form a fusiform mass of muscle, thicker in the middle than at its extremities, and very prominent upon the front of the arm when thrown into action.

Even when it is not in a contracted condition, as it is in Fig. 28, an obvious ridge, extending the whole distance of the lower two-thirds of the arm, may be observed (Fig. 29).

As the biceps passes to its insertion in the tuberosity on the radius, it becomes narrow and tendinous. The tendon may be traced as a sharp ridge vertically across the hollow in front of the elbow nearly to its insertion.

The Semilunar fascia (Figs. 24, 26, 28) is a thin but strong fibrous expansion from the biceps in the upper part of the front of the forearm, extending from the inner border of the tendon of the biceps downwards and inwards to join the deep fascia of the forearm, and indenting transversely the mass of muscles which arises from the internal condyle of the humerus.

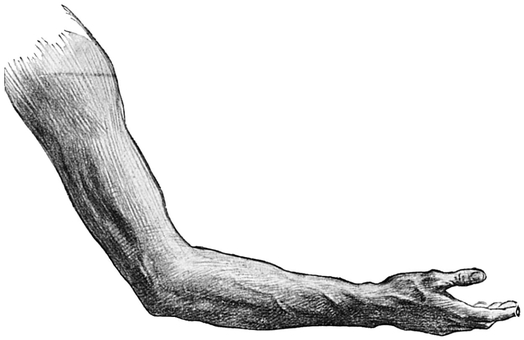

Fig. 29.—The Outer Side of the Right Upper Extremity.

On each side of the biceps is a groove (Fig. 26); in the outer lies the cephalic vein, in the inner the basilic vein and brachial artery, the latter more deeply situated, but visible sometimes in thin old persons, and especially if it is tortuous.

Lying behind the biceps on the inner side of the arm is the inner head of the Triceps, which arises from the humerus all the way from the lower border of the pectoralis major to the internal condyle of the humerus (Figs. 24, 28, 30).

To the outer side of the biceps in the upper half of the arm is the great mass of the deltoid muscle (Figs. 22, 23, 26), and in the lower half, arising from the external supra-condylar ridge, are the Supinator longus, a muscle which is chiefly important as a flexor of the elbow joint, and forming when in the contracted condition a very obvious swelling; and the Extensor carpi radialis longior, a smaller and very similarly arranged muscle lying below and behind the supinator longus (Figs. 19, 22, 30).

Fig. 30.—Muscles on the Back and Outer Side of the Right Elbow-Joint.

The furrows which lie on each side of the biceps converge below where the mass of the muscle narrows, and terminate in a hollow on the front of the elbow called the Ante-cubital fossa. This fossa is triangular, with its base, directed upwards, opposite the elbow-joint (Figs. 26, 31, 34, 35).

An important vein lies in the lower half of the groove upon the inner side of the biceps. It is known as the basilic vein. At the centre of the arm it passes through the deep fascia, and disappears from view to join the deep veins of the arm accompanying the brachial artery (Figs. 26, 33, 35).

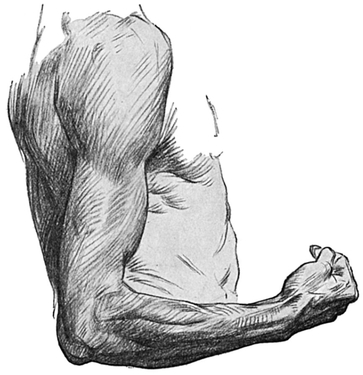

The back of the arm presents for examination two large muscles, the deltoid and the triceps.

The posterior border of the deltoid runs from the inner part of the spine of the scapula downwards and outwards to the insertion of the muscle a little above the centre of the outer surface of the humerus. This ridge of muscle bounds a deep and obliquely placed groove which lies parallel to and immediately below it, and is succeeded again by the mass of the Triceps (Figs. 22, 23, 29), which passes downwards with a slight inclination inwards, to terminate below by being inserted into the upper part of the Olecranon process, or point of the elbow (Fig. 30).

A second groove, passing similarly downwards and inwards, across the inner part of the back of the arm but nearer to the elbow, separates the upper and outer humeral head from the inner and lower humeral head of the triceps (Figs. 19, 22, 29).

When the arm is abducted from the side against resistance, three other features are to be noted upon the posterior aspect of the arm.

First, below (i.e. in the present abducted position of the arm) the posterior deltoid border, the scapular, or long, head of the triceps forms a slightly elevated ridge, passing from the back of the shoulder-blade to the arm (Fig. 24; Plates XIII., XVI.).

Secondly, above the triceps, the biceps muscle may be seen, producing a marked prominence (Plate XVI.).

Thirdly, the skin over the deltoid presents some longitudinal grooves, which indicate the position of some tendons within that muscle (Plate XX.).

Thus it is to be noticed that, although the biceps is situated on the front of the arm, so prominent is it that a portion of it may be seen from the back on the outer side of the arm; and similarly we have already pointed out (p. 85) that the triceps, although situated upon the back of the arm, can be seen also, in part, from the front.

The Elbow.— The bony landmarks are very obvious. The “point of the elbow ” is formed by the posterior part of the upper surface of the olecranon process (Fig. 5, p. 40). It bounds above a triangular subcutaneous area of bone, the sides of which converge below to form the posterior border, which is also subcutaneous, of the ulna.

The Internal and external condyles of the humerus lie a little above the bend of the elbow. The internal condyle is the more prominent, partly because of its actual size, and partly because the muscles arising from the external supra-condylar ridge of the humerus obscure the external condyle (Fig. 30). The two condyles lie on the same level, and the olecranon just comes up to this level in the extended position of the elbow-joint, but in the acutely flexed position these three bony eminences form the apices of an equilateral triangle.

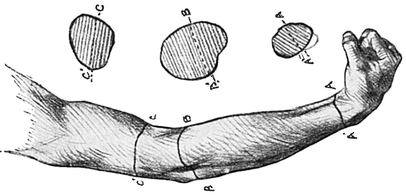

Fig. 31.—The Outer Side of the Upper Extremity, with indication of the varying shape of transverse sections at different levels.

A transverse section of the arm above the elbow is nearly circular. The forearm just below the elbow is flattened from before backwards and bulges laterally. It tapers towards the wrist, but remains more flat in males, while in females it has a more circular outline (Fig. 31).

The Carrying Angle.—The extended forearm makes with the arm an angle of 160° or thereabouts, open outwards (Fig. 35). This “carrying angle,” as it is called, diminishes progressively as the arm is flexed until it completely disappears in full flexion (Fig. 32). Indeed, by the time the elbow is fully flexed, the hand will be seen to have been carried over actually on to the inner side of the arm. The presence of the carrying angle is independent of supination or pronation of the hand, and is of great importance mechanically; indeed, it looks very much as if it was designed to allow weights which are being carried, e.g. a bucket, to swing clear of the pelvis and lower limbs, thus saving much muscular effort. The carrying angle is due to the large size of the inner lip of the trochlea of the humerus (Figs. 3 and 4, pp. 38, 39).

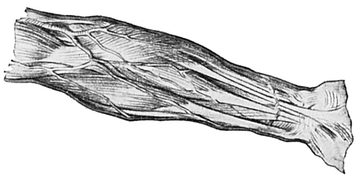

The Forearm.—The triangular ante-cubital fossa is bounded on each side by prominent ridges of muscles (Figs. 26, 33, 34).

Fig. 32.—The Back of the Forearm and Hand, showing surface markings of muscles and tendons. Notice the disappearance of “carrying angle,” when arm is flexed at elbow.

On the inner side is the ridge formed by the supperfacial flexors muscles of the hand and the pronator radii teres. The latter is inserted into the middle of the outer surface of the radius. Notice the wisp of semi-lunar fascia springing off the inner side of the tendon of the biceps and passing inwards over, and indenting, the mass of muscle just below the internal condyle (Figs. 24, 26). The indentation is most obvious when a muscular subject strongly flexes and supinates the forearm. The ridge which bounds the triangle externally is formed by the Supinator longus muscle (Fig. 26). Under this the pronator radii teres passes to its insertion, and it is by the convergence of these muscles that the apex of the fossa is formed at a point which lies under cover of the largest of the superficial veins depicted in Fig. 33, p. 89.

Fig. 33.—Muscles and Superficial Veins on Front of Right Forearm.

Fig. 34.—Muscles on Back of Right Forearm.

Lower down the limb tapers gradually, because the muscles give place to tendons, only two of which are prominent on the surface, viz. the palmaris longus and the flexors carpi radialis. These two tendons lie one on each side of the mid point at the wrist (Fig. 33).

[A slight prominence which affords no evidence of extensive muscular development may occasionally be seen on the front of the forearm two or three inches above the wrist in the middle line. It is due to an extra muscular belly formed in connection with the palmaris longus.]

The “pulse” in the radial artery may sometimes be seen, and nearly always felt, just external to the flexor carpi radialis tendon.

On the inner side of the tendons previously mentioned is the flexor carpi ulnaris. This does not produce any external form, but internal to it is a small shallow depression (Fig. 28).

The Veins of the Foerarm (Figs. 26, 29, 33, 34, 35).—The main superficial veins of the forearm are found chiefly upon the front. They may be made to stand out much more clearly than usual if the fist be repeatedly clenched, especially if some constricting band is lightly applied meanwhile just above the elbow. Under these circumstances the veins will be dilated at intervals in bead-like eminences, due to the presence of valves within them.

Fig. 35.—Right Upper Extremity Surface markings of Muscles. Tendons, and Superficial Veins.

These veins drain the hand. The median vein passes from the radial border of the lower part of the forearm to the ante-cubital fossa, where it divides into two branches, viz. :—

1. The median cephalic, which joins with some veins passing from the radial side of the upper two-thirds of the forearm, to form the cephalic vein, and to pass upwards in the groove on the outer side of the biceps 91 muscle, afterwards entering the groove between the pectoralis major and the deltoid, where it has already been alluded to.

2. The median Basilic, which passes over, or super-. ficial to, the semi-lunar fascia and joins with some veins draining the ulnar side of the forearm to form the basilic, and then up the arm on the inner side of the biceps. This vein is not seen when it reaches the middle of the arm, as it then ceases to be superficial.

The median basilic is the vein which is most conveniently opened for the purpose of blood-letting, a practice quite fashionable a few decades ago, and still resorted to occasionally.

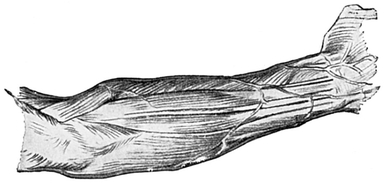

If we now study the back of the forearm (Figs. 29, 30, 32, 34), the first thing to be noticed is the triangular subcutaneous area of the ulna below the olecranon process, continuing downwards into the posterior border of the shaft of the ulna, and easily traceable by the examining finger right down to the prominent little head of the same bone near the wrist. This border of bone lies close to the inner aspect of the forearm, being as a rule at the bottom of a small but distinct furrow, because it is subcutaneous all the way and therefore easily felt. The furrow is bounded by two ridges; that on the inner side is due to the flexors carpi ulnaris, and that on the outer side, less well marked, to the extensors carpi ulnaris muscle.

External to the olecranon is a slight fossa (Figs. 30, 31), in which the head of the radius lies, and can be felt and sometimes seen. A distinct furrow runs downwards and inwards from this fossa, and to its outer side is a ridge due to the muscular mass of the extensor communis digitorum, which when it contracts draws the fingers backwards (Figs. 31, 32, pp. 88, 89, and Fig. 34, p. 90).

Another slight groove to the outer side of the extensor communis separates this muscle from the extensor carpi radialis brevior above and from the extensor ossis metacarpi pollicis below.

The anconeus (Fig. 34, p. 90) is a very short muscle which forms a triangular mass extending from the external condyle towards the posterior border of the ulna.

The tendons of the extensor muscles (Fig. 34) passing to the fingers are placed in deep grooves on the back of the radius and ulna, and cannot be seen through the skin till they get below the wrist, being hidden above by dense deep fascia.

It is probably a very common rule that when any muscle in the limbs is thrown into voluntary action its opponent undergoes a simultaneous but slighter contraction, so as to steady the moved part. A pretty illustration of this rule is found in the fact that if you watch the back of the forearm while .you flex your fingers, however slightly, you will see the extensor communis digitorum become more prominent.

Fig. 36.—The Creases upon the Front of the Hand and Digits.

The Wrist(Figs. 36etseq.).—This is the region which connects the hand with the forearm. On the inner side of the Dorsum or back of the wrist is a bony prominence formed by the head of the ulna (Plate XXXI.). The styloid processes of the ulna and radius, that of the latter being placed a little lower, can be easily felt, but, except in very thin persons, they cannot be seen. Although a large number of tendons pass from the extensor muscle bellies in the forearm to become obvious on the dorsum of the hand, none of them is visible at or above the wrist, because they are bound down and obscured by a transverse, or rather a slightly oblique, band of the deep fascia, known as the posterior annular ligament (Fig. 34). It may be traced by dissection from the region of the lower end of the ulna to the outer surface of the radius on a rather higher level. This special thickening of the deep fascia bridges the grooves on the lower end of the radius and ulna, which transmit the extensor tendons from the back of the forearm to the dorsum of the hand.

Fig. 38.—The Short Muscles of the Hand, and the Tendons passing under the Anterior Annular Ligament.

The Palmaris longus is cut as it passes over the annular ligament.

Fig. 37.—The Deep Palmar Fascia.

The Hand (Figs. 31, 32, 35, et seq.) presents for examination the palm and the dorsum, and the fingers and thumb collectively known as digits.

The hand is broader and flatter than the wrist, the increased breadth being due in great part to the thumb. When this is bent into the palm—or, as the technical expression goes, when the thumb is “opposed ”—the hand becomes much narrower, and its breadth approximates to that of the wrist.

The palm of the hand (Fig. 36 et seq.) is continuous with the front of the forearm, but its general surface is raised from that of the forearm by the thenar and hypo-thenar eminences, composed of small muscles. Between these two eminences is a hollow lined by a thick fibrous structure, the palmar fascia, which succeeds to a fibrous transverse arch, the anterior annular ligament, whose function is to form the roof of a tunnel through which the flexor tendons pass on their way from the front of the forearm to the front of the fingers. The walls and floor of the tunnel are formed by the carpal bones (Fig. 38).

The skin over the palm is very thick, and in persons accustomed to hard manual work it is horny. It is plentifully supplied with sweat-glands, but devoid of hairs and sebaceous glands. Certain lines or skin folds found on the palm will be described later.

The palm of the hand forms a shallow, saucer-like hollow, bounded above and at the sides by the thenar and hypo-thenar eminences, and below by the prominences at the bases of the fingers. When the fingers are forcibly extended, these prominences can be seen, and in every position of the fingers they can be felt, to be due to the heads of the metacarpal bones.

Between the four metacarpal heads there are easily seen, when the fingers are semi-flexed, three little soft eminences—caused really by pads of fat. The slight depressions between these three eminences are due to the prolongations from the base of a triangular sheet of fibrous structure (Fig. 37), which is attached by its apex above to the anterior annular ligament. Below, at the root of the fingers, the base of the triangle is split into four processes, each of which is attached to the tendon sheath on the front of a finger. The structure is dense and fibrous, and is known as the palmar fascia. It is continuous above with the palmaris longus (cut short in Fig. 38, p. 94). The anterior annular ligament is a strong fibrous bridge springing across from the base of the thenar eminence to the base of the hypothenar eminence. Its superficial surface is about the size of a postage stamp placed transversely, and under it the flexor tendons pass from the front of the forearm into the palm of the hand.

Fig. 39.—Showing Formation of Creases or “Lines of Flexion ” in the Skin of the Hand and Digits.

The lines on the palms, upon which “palmistry” is founded, are due to the varied and frequent movements of the fingers and thumb and the presence of underlying muscles. Their actual position and length undoubtedly vary in different individuals.

A very brief description of these lines must suffice (Fig. 36, p. 93, and Fig. 39).

There are three main lines. The first passes from the inner side of the upper end of the thenar eminence and curves downwards and outwards to a point on the outer border of the palm, situated half an inch below its centre, and on a level with the distal part of the outstretched thumb. This line is due to the movement of the thumb in “opposition” (p. 95), an action brought about by the short muscles of the thumb which form the thenar eminence.

The second line passes from the inner border of the palm, three-quarters of an inch above the little finger, to the cleft between the index and middle fingers, but to the outer part of the cleft. It is made obvious by flexing the inner three metacarpo-phalangeal joints while the index and thumb are extended.

The third main line passes outwards from the lower part of the hypo-thenar eminence between the other two main lines, and reaches the outer border of the hand one inch above the index finger, on about the same transverse level as the point at which the second line begins. It is made obvious by flexing the four inner metacarpo-phalangeal joints.

The thenar eminence at the base of the thumb is especially scored by numerous smaller lines.

The fingers are not attached to the palm on an exactly transverse plane. Their line of attachment is slightly curved, so that the cleft between the middle and ring fingers is one-third of an inch further from the wrist than the clefts between the other fingers.

The Back of the Hand.—The skin on the back of the hand is rougher, looser, and thinner than that of the palm. It is covered with fine hair, and immediately beneath the skin lies an irregular venous plexus which receives the veins from the digits. There is usually discernible a more or less well marked venous arch, with convexity towards the digits, which receives these digital veins.

In delicately nurtured hands the veins appear as thin blue lines; in the horny hand of the labourer they are tortuous, dilated, and bulging; in old age they become more obvious, and so do the spaces between the metacarpal bones, owing to the wasting of the soft tissues.

Upon the back of the hand, and situated under-neath the veins, are various ridges corresponding to the tendons of the extensor muscles of the fingers. (The thumb is not now being described.) These ridges are seen to great advantage when the wrist is extended, i.e. bent backwards, and the metacarpo-phalangeal joints extended and the inter-phalangeal joints flexed, and the hand kept tight in this position (Fig. 40).

Fig. 40.—The Hand in the best position for demonstrating the Extensor Tendons.

Certain tendons make more obvious and constant ridges than others. Thus, in most subjects, the tendons passing to the middle and ring fingers stand out distinctly as compared with those passing to the index and little fingers. The tendons passing to the index and little fingers are duplicated, a fact which doubtless is associated with their freer movements.

The innermost tendon of the index finger sends a slip to join the tendon passing to the middle finger, and the tendon of the ring finger sends a slip on each side to the adjacent tendons of the middle and little fingers. These slips lie subcutaneously, and may occasionally be seen close to the base of the fingers. They are probably responsible for the difficulty the pianist experiences in raising the ring finger independently of the others.

The Thumb.—It is chiefly the extraordinary mobility of the thumb that distinguishes the hand of man from the paw of the lower animals, including the anthropoid apes.

When it is in its natural position of rest its surfaces look inwards and outwards—an important fact, for the surfaces of the other digits look directly forwards and backwards. It follows from this that when the limb is extended with the palm looking to the front, the nail of the thumb can be seen, whereas the nails of the fingers are not visible—except, of course, in those Eastern races, and their rare Western mimics, who cultivate extraordinary length of nails.

The thumb rises from the surface of the palm in a distinct rounded prominence called the thenar eminence, oval, with its long axis directed downwards and outwards, and its skin scored by numerous transverse lines. Through this skin one or two veins may show, and occasionally in old persons the superficialis volœ artery may be observed pulsating as it pursues a vertical course across the thenar eminence, but it disappears suddenly before it reaches the palm.

The upper and outer free border of the thenar eminence is formed by the metacarpal bone of the thumb, and is straight, and inclined from the outer border of the forearm, with which it is continuous, at an angle of 45°, when the hand is in a position of rest with the palm forwards. This angle may, however, be increased to 60° or 70° by powerful abduction, or by adduction of the thumb it may be wiped out altogether.

This outer border of the thenar eminence, if traced on to the two phalanges, becomes the outer surface of the thumb. The metacarpo-phalangeal joint is rather less than half-way from the base of the thenar eminence to the tip of the thumb, and is nearly always kept slightly flexed. It is not a joint which permits of much mobility, but such as it has is extremely important to the function of this most important digit. Near the termination of this outer surface, the thumb-nail breaks into its continuity; but short of this, in the part which corresponds to the first phalanx, the surface is concave.

The internal surface of the thumb (Fig. 40) is also concave opposite the first phalanx, convex opposite the second. It is united by a web to the outer border of the palm, a little above the centre of a line drawn from the upper limit of the thenar eminence to the base of the index finger.

The thumb is the shortest digit with the exception of the little finger. It is, however, much more massive than the other digits. Its shape is roughly cylindrical; at its root it is thicker from before back, and distally where the nail comes it is thicker from side to side. On its palmar aspect the skin presents the same characteristics as that of the palm. Its surface is broken at the joints by one or two lines of flexion; and shows multitudes of very fine lines, especially on the terminal phalanx, which, if studied with a hand lens, are seen to be arranged concentrically, but never exactly alike in any two individuals—a fact which has in recent years been used for the registration of criminals and others by taking and preserving their “finger-prints.”

These finer lines are seen over the whole palmar aspect of the hand and digits, and are associated with the high development in these regions of the sense of touch. On the outer, inner, and posterior aspects of the thumb the skin is similar to that on the back of the hand. On the distal knuckle of the thumb are numerous transverse lines.

The anatomical snuff-box is the name given to a depression on the back of quite the upper part of the thumb. Its boundaries are two ridges that are particularly obvious if the thumb is actively extended. The outer ridge is formed by the extensor ossis metacarpi pollicis and extensors primi internodii pollicis tendons; on the inner side the snuff-box is bounded by the ridge of the tendon of the extensor secundi internodii pollicis (Plate XXX.).

By waggling the thumb slightly while keeping it extended, each of these three tendons can be traced to the base of the bone indicated in its name.

The Fingers.—The middle finger is the longest, and the ring and index fingers are commonly of equal length. The bases of the three inner fingers are of about equal breadth, but the base of the index is broader than the others in the proportion of 11 to 10. With these figures as a guide, the base of the first phalanx of the thumb would be represented by the figure 12.

The fingers, as a rule, taper to their extremities, and the more they taper the more beautiful they are supposed to be; but the ends of the ring and middle fingers are frequently a little expanded. The fingers widen across the plane of the middle knuckles, but contract slightly across the plane of the distal knuckles.

Transverse lines are seen on the palmar surface of the joints. The upper set lies three-quarters of an inch below the knuckle, the middle set exactly opposite, and the lowest set one-quarter of an inch above the corresponding knuckle (Fig. 39, p. 96).

The individual variations of the hand are considerable, and indeed second only in importance and interest to the variations in type and character of the head and face. Sir Charles Bell and Sir George Humphry have written most able accounts of this fascinating subject, and the student should turn to their books if he would fathom its interest. But even the most casual observer sees at the first glance the essential difference between the tapering fingers and small supple hand of the lady of ease, the large horny and rigid fist of the manual worker, the clubbed and bluish fingers of the chronic pulmonary invalid, the chubby “braceletted” hand of the infant, the podgy, smooth, insensitive hand of the well-fed successful man of sedentary habit, and the bony, dry hand of old age with its fingers all tending to lean their tips towards the ulnar side.