LEE RAIL UNDER

23

Storm Over Oulton

THE TWINS HAD joined the Teasel none too soon. All the way from Horning to Beccles there had been nothing too difficult to be managed by Tom with no one to help him but the Admiral and a most inexperienced crew. But when they were waked in Beccles by a milkman bringing the morning milk down to the staithe, they saw, as soon as they put their heads out, that the weather did not look so kind as it had been. There was a sulky feeling in the air, and the sky was dark in the east.

‘Thunder coming,’ said Tom, when he and Dick went aboard the Teasel for breakfast.

‘Looks as if it’s going to blow,’ said Starboard.

‘Rain, too,’ said Port.

‘Let’s get away quick,’ said the hopeful Admiral, ‘and we’ll be in Oulton before it starts.’

The moment breakfast was over they were off. With a full crew once more, two to a halyard and one to spare, not counting the Admiral and William, the Teasel set sail in record time, while Mr Whittle and Mr Hawkins, smoking their pipes, watched from the deck of the Welcome at the other side of the river.

‘You’ve got a smart ship, you ’ave,’ said Mr Whittle as the Teasel headed towards the big barge, swung round close by her and was off, racing down the river with the wind abeam.

Mrs Whittle came up the companion to shake a duster just in time to use it to wave farewell.

‘You’ll be wanting a reef later,’ called Mr Hawkins, pointing at the dark clouds in the eastern sky.

No one was on the staithe when they sailed, but just before they lost sight of it, Dorothea looking back at the town the returned native was leaving once more, saw a boy on a red post office bicycle ride across the staithe to the water’s edge. No one else saw him. The Admiral was tidying the cabin and filling in the time of sailing in the ship’s log, which, as usual, everybody else forgot in the bustle of getting away. Tom and Dick were busy with mainsheet and tiller. Port was swabbing the decks round with a mop, to clear off any mud brought aboard from the shore. Starboard was washing a muddy anchor over the side. The boy jumped off his bicycle and stood on the edge of the staithe, waving. Dorothea, thinking it was rather nice of him, waved back. The next moment they were round a bend in the river and could see the staithe no more.

The wind was easy enough at first, and when they had got through Aldeby Bridge, Dick was being allowed to steer when, without a moment’s warning, a squall came whistling over the marshes, and the Teasel swept suddenly round as if she wanted to charge the bank.

‘Keep her going,’ said Tom, who was on the foredeck tightening up the flag halyards.

Starboard steadied the Teasel with a quick, helping hand on the tiller. The squall was gone as suddenly as it had come, but the three Coots looked anxiously over the marshland at a threatening wall of cloud.

‘I wonder if we ought to,’ said Port.

‘Reef?’ said Starboard. ‘We’ll have to if it gets worse.’

‘We may get through to Oulton before it really comes on,’ said Mrs Barrable cheerfully.

The Coots looked at each other. That was the Admiral, being rash. But everybody is glad of an excuse not to reef, and Tom and the twins were happy to put it off. They were happier still when they sailed into the shelter of the trees and, so far from wanting to reef, would have been glad of a little more wind than found its way through the leaves.

‘The leaves are getting thicker every day,’ said Starboard.

‘It must be rotten getting through here in summer,’ said Tom, ‘nearly as bad as Wroxham.’

They let Dick and Dorothea take turns in steering, as the Teasel tacked along that reach under the tall trees just breaking out into their summer green. First to one side of the river and then to the other, watching the Teasel’s wake to see how well or badly they had brought her about. The Teasel was a training ship once more.

‘Not so hard,’ Port kept saying. ‘Let her come round gently, and she’ll get a little bit for nothing.’

‘For nothing?’

‘If you bring her hard round, the rudder stops her, and you lose. Gently. … Gently!’

They came out of the trees at last, and, just as they reached the open, they heard again that wild, hissing, whistling noise over the marshes.

‘A Roger1 coming,’ said Port.

‘A Roger,’ laughed Dorothea. ‘Give him some chocolate. The Roger we know’s always ready for some.’

But the Coots hardly heard her. Things were much too serious.

‘Better take the tiller, Tom,’ said Starboard. ‘We’ll look after the sheets. Look out! Here it comes.’

A sudden violent gust of wind hit the Teasel. She heeled over. Port and Starboard eased the sheets, just a little. She lifted, and again heeled over. Tom, clenching his teeth, held her firmly on her course. If only the gust would slacken before he had to go about. But the river was narrow. The Teasel was foaming towards the bank. ‘Ready about!’ he called. The yacht churned round with flapping head-sail. The wind dropped as suddenly as it had come.

‘Now’s our chance,’ said Tom. ‘Jam her nose in by those reeds. I’ll skip forrard. Let go jib sheet.’

The Admiral, Dick and Dorothea were utterly disregarded. This was an affair for experienced seamen. The three Coots knew that the Teasel was carrying too much sail if the squalls were going to be as hard as that one. They were going to take a reef in at once. In a moment Port had the tiller and was bringing the Teasel up to the bank, Tom was on the foredeck with the rond-anchor in his hand, and Starboard was standing by to let go the sheets. There was a gentle swish as the Teasel’s bows pushed into the reeds, and a squelch as Tom jumped.

‘What’s going to happen?’ asked Dorothea.

‘Reefing,’ said Starboard.

‘It’ll hold all right,’ said Tom, and was aboard again and busy at the mast. Port ran forward to help. The jib was coming down, the boom was lifting, the peak was dipping, and all at once. The mainsail came quickly down. The boom was lowered into the crutches that Starboard had fished up out of the Titmouse.

‘I suppose you’re right,’ said the Admiral.

‘More squalls coming,’ said Tom.

The next twenty minutes were full of hard work. Everybody had something to do, and William, feeling the excitement, cheered them on at their work with one of his barking fits. Just as they had finished neatly rolling up the reef, and lacing it along the foot of the sail, down came the first large spots of rain.

‘Never mind,’ said the Admiral, ‘we’ve all got oilskins, except poor William.’ But William was not going to let himself get wet. While other people were struggling into oilskins, and those who had been wearing sandshoes were changing them for sea-boots, William decided that it was not the sort of day he liked, went into the cabin and made himself comfortable on the Admiral’s bunk.

‘What about your Titmouse?’ said the Admiral. ‘How are you and Dick going to sleep in her if she gets all wet?’

‘Come on, Dick,’ said Tom, who was beginning to regard Dick as the mate of the Titmouse, even if, in the Teasel, he was only an apprentice. ‘We’ll use the awning as a hatch cover. We’ll lace it all round over everything. It’ll keep things pretty dry.’

The Titmouse was covered all over. She was pulled up alongside so that the last bit of the lacing, round the stern, could be done from the deck of the Teasel after Tom and Dick had scrambled out. They looked down at her, with her mast and sail making a sort of mountain range between two valleys in the awning.

‘There’ll be a lot of water in the hollows,’ said Dick.

‘We can empty it out by lifting the awning in the middle,’ said Tom.

‘She’ll be dry enough inside,’ said Starboard.

A few minutes later the Teasel, with a reef in her mainsail, was off again, and there was hardly enough wind to give her steerage way.

‘That’s what it always does,’ said Port. ‘It makes you reef and then it drops away altogether and makes you wish you hadn’t.’

‘Not for long,’ said Tom, looking ahead of them at the dark sky behind the rain.

They were just moving with the stream, while the rain poured down on them, dripping off the sail on the cabin roof and off the cabin roof on the side decks. Already there were lakes in the valleys of the Titmouse’s awning. Then, gently at first, the wind came again, and they worked round the bends by Black Mill and Castle Mill, and were able to reach the rest of the way down the Waveney to Burgh St Peter and the mouth of Oulton Dyke. Here the wind headed them. They had long ago stopped wishing they had not reefed. Squall after squall had made them wish they had taken in two reefs instead of only one. It was really hard work sailing, and in a wind like this, that found its way through everything, not even oilskins seemed able to keep the rain out.

‘I can feel it trickling down my collar,’ said Dick. ‘And, oh, my beastly spectacles!’

‘It’s gone right up my sleeves,’ said Port, who had been looking after the mainsheet.

Tom said nothing. His were old oilskins, and the proofing had cracked across the shoulders, and all the top part of him was wet. While steering he had not noticed until it was too late that water was running off the oilskins straight into one of his sea-boots. Every time he moved his right foot he could feel the water seeping round it. But this was no time to think of things like that. The wind was growing harder and harder, and backing to the east. If it was as bad as this between the banks of sheltering reeds, what would it be like when they came out into Oulton Broad?

‘It isn’t very much farther,’ said the Admiral, ‘and it really does look rather fine.’

‘Thunder,’ said Dorothea.

‘I thought it must be coming,’ said Starboard.

There was a distant rumbling, and then a sudden crash, followed by a clattering as if an iron tea-tray ten miles wide was tumbling down a stone staircase big enough to match it.

‘Look!’

‘And over there!’

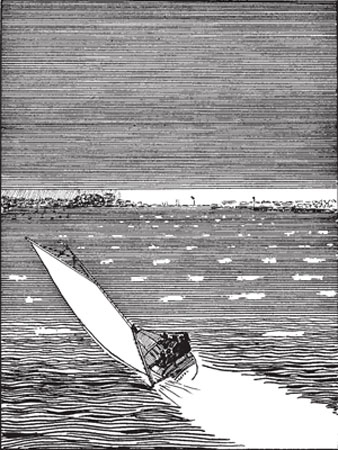

Threads of bright fire shot down the purple curtain of cloud into which they were beating their way. There was a tremendous roll of thunder. And then, just as they were coming out of the dyke into the Broad, the rain turned to hail, stinging their hands and faces, bouncing off the cabin roof, splashing down into the water. In a few moments the decks were white with hailstones. The noise of the hail was so loud that no one tried to speak. It stopped suddenly, and a moment later the wind was upon them again. The Teasel heeled over and yet further over, till the water was sluicing the hailstones off her lee deck.

‘Ease away mainsheet,’ shouted Tom. ‘Quick!’

There was a crash somewhere close to them, in the Teasel herself. They looked at each other.

‘Water-jar gone over,’ said Port.

‘Ready about!’

Crash.

‘There goes the other jar.’

‘Ease out. In again. Must keep her sailing.’

‘Look out, Tom, you’ll have her over.’

‘Sit down, you two. On the floor,’ said the Admiral. ‘My word,’ she murmured, ‘Brother Richard ought to see this.’

It was a gorgeous sight. There was that purple wall of cloud, with a bright line along the foot of it, and against this startling background, white yachts and cruisers afloat at their moorings in the Broad shone as if they had been lit up by some strange artificial light. The green of the trees and gardens looked too vivid to be real, wherever it was not veiled by a rain-squall. It was a gorgeous sight, but not for the Coots, who were finding it all they could do to keep the yacht sailing and yet not lying over on her beam ends. It was a gorgeous sight, but not for Dick and Dorothea, who began to think that they had not yet learnt much about sailing after all. And it was not at all a gorgeous sight for poor William, who was thrown from one side to the other whenever the Teasel went about, and was shivering miserably on the floor of the cabin, sliding this way and that with the sandshoes that had been thrown in to keep dry.

They were half-way down the Broad now, looking at the Lowestoft chimneys, and the Wherry Inn, and a great crowd of yachts at their moorings. Tom kept telling himself to think only of keeping the Teasel sailing, and not to bother about the yacht harbour until they came to it. But he could not help wondering all the time what he would find. He knew it had been changed since he had been there with the twins and their father. He would soon have to be making up his mind where to tie up. With the wind that was blowing he did not think the Teasel’s mudweight would hold her if they were to try to anchor in the open Broad. And all the time they were getting nearer. The Teasel was crashing to and fro, beating up in short tacks nearer and nearer to all those boats, and the road beyond them, where motor buses were driving through the rain. Suddenly to starboard he saw a wooden pier with a tall flagstaff at the farther end of it, where the opening must be. Behind it was clear water … a stone quay … little grey buildings … a moored houseboat. And there was a man in oilskins running out on the quay and waving. To the Teasel? It must be to her. There was no other boat sailing.

Tom headed for the flagstaff. The Teasel flew past it, round the end of the wooden pier, and was in the yacht harbour. The harbour seemed much too small, as a squall sent her flying along between the pier and the quay. Tom swung her round, judging his distance from the beckoning man. How far would she shoot, going like this? He had never before had to moor her in such a wind, and against a stone quay, too.

‘Let fly jib sheet! Slack away main! Fenders out!’

‘Not you, Dick!’ But Dick was already out of the well, and hanging the fenders over the sides.

‘Look, out of the way, Dick.’ Port was hurrying forward.

Nearer and nearer. Tom looked up at the high stone quay. Would she fail to get so far? Would he have to bring her round and get her sailing again? Nearer and nearer. And then, close alongside the quay, the Teasel stopped, without even touching. That man in oilskins was holding her by the forestay. Port was already on the foredeck, handing him up the mooring warp, rond-anchor and all. The rain was stopping. The wind had suddenly dropped now that the Teasel had escaped it. Tom, rather shaky in the knees, went forward to help in lowering the sails. The man was talking.

‘Good bit of work you did then,’ he was saying. ‘Didn’t think you’d make it as neat as that with the wind blowing as it was. She had all she wanted coming up the Broad. The Teasel, is she? Are you Mr Tom Dudgeon? I’ve a telegram for you sent on from Beccles.’

‘A telegram?’

‘I’ve got it in the office. I’m the harbour-master.’

He ran across the quay and was back in a moment with a red envelope. Tom tore it open. He had never had a telegram in his life. But there it was, plain on the envelope, and again on the telegram form:

‘TOM DUDGEON YACHT TEASEL BECCLES

ARE TWINS WITH YOU TELEPHONE

IMMEDIATELY

MOTHER.’

Tom read the telegram aloud, and took it to the well to show it to Mrs Barrable.

‘Why does she want to know about us?’ said Port.

‘How did they know at Beccles we’d gone here?’ said Tom.

Dorothea remembered the boy with a red bicycle on Beccles staithe. ‘It only just missed us,’ she said. ‘I saw the boy waving, but I never thought he wanted to stop us. He probably asked the barge people, and they knew we were going to Oulton because we told them.’

‘You can use the telephone in my office,’ said the harbour-master, and Tom, dripping as he walked and squelching in his sea-boots, one of which was half full of water, hurried with him across the wet quay.

‘We’d better go, too,’ said Starboard.

‘Yes,’ said the Admiral, and the twins, shaking the water from their sou’westers as they ran, hurried after Tom.

‘I do hope something isn’t wrong,’ said the Admiral.

The harbour-master left the Coots at the telephone in his office and came back to the Teasel to lend a hand with the soaking wet sails. He came aboard and took charge and had the sails down in no time, while Dick and Dorothea did their best to help.

‘Don’t tie them up,’ he said. ‘We’ll be having sunshine after this and getting them dry. But it’s wet you are, and no wonder. Will you be having hot baths, and I’ll be having your wet clothes dried the while?’

‘Hot baths!’ exclaimed Mrs Barrable, and there, on the quay, by the harbour-master’s office, Dorothea saw the notice and pointed it out, ‘Hot baths, 1s.’

‘We have fallen on our feet,’ said Mrs Barrable, and then hesitated, looking across the quay towards the office where the ringing of a telephone bell suggested that Tom had got through to Horning. ‘We must wait till we know what that telegram means.’

In the harbour-master’s little office, all three Coots wanted to use the telephone at once. Tom was talking to his Mother.

‘But they’re here. … They caught us up at Beccles just after we’d sent off those postcards. … Jim Wooddall gave them a lift … and then a barge. … They’re here now.’ He turned to speak to the twins. ‘It’s those postcards we sent to you first thing in the morning. They got the early post. And Ginty went flying round to Mother. …’

Starboard grabbed the receiver. ‘Good morning, Aunty. … Oh, no. … We’re as good as gold, really. … We always are. … Rather wet. … Come on, Port. … Your turn. …’

Tom got the telephone again. ‘Hullo, Mother. No. I’ve shut them both up. Oh, Ginty wants to talk to them. All right. What did Joe say?… I can’t hear. … Sorry. … Beasts. … Stuck in Wroxham? Three cheers. … Awning for the Death and Glory. … Good. … I thought they would. … I’ll telephone from Norwich. Somewhere, anyhow. Everything’s going fine. The Teasel’s a beauty. Oh, no. The storm wasn’t so awfully bad. We got through it quite all right. What? Ginty waiting? Oh, all right. Goodbye, Mother. Love to our baby and Dad. Come on, Port, Ginty’s coming to the telephone to give you what for. …’

Port took the telephone and waited. There was a short pause. She frowned and signalled to Tom and Starboard to keep quiet. Tom was bursting with good news.

Then: ‘Yes. Hullo. It’s a braw mornin’, Ginty, and we’re all well the noo, and hoping your ainsel’s the same.’

‘Oh, Port, you idiot,’ said Tom. ‘What did Ginty say?’

‘Ye young limb. … All right, Ginty. … I’m only trying to tell them what you said to me. …’

The anxious watchers in the Teasel knew the moment the Coots came out of the office that the telegram had not brought bad news.

‘It was only those postcards,’ Tom explained to Mrs Barrable from the edge of the quay. ‘Ginty couldn’t think what had happened when those postcards came for the twins saying how much we wished they were with us. So she shot round to Mother, and wanted to send telegrams all over the place. It’s lucky Mother didn’t let her send one to Uncle Frank. And the Hullabaloos are stuck at Wroxham for repairs. They bust someone’s bowsprit, and got a hole in old Margoletta at the same time, charging across the bows of a sailing yacht … big one, luckily. And Joe’s been making an awning for the Death and Glory. I thought he would when he’d seen Titmouse’s. I’ve promised to telephone again from wherever we go to next.’

‘Stupid of me,’ said the Admiral. ‘I ought to have thought of telephoning myself.’

‘It would have been much worse if you’d telephoned before we arrived,’ said Starboard.

‘It’s all right now, anyhow,’ said Port.

‘Everything’s going righter and righter,’ said Dorothea. ‘First, Port and Starboard coming, so we’re all together. And now no more Hullabaloos.’

‘They were bound to have a smash sooner or later,’ said Starboard, ‘charging about and expecting all sailing boats to get out of their way.’

‘Well,’ said the Admiral, ‘Tom’s worries are over at last. And everybody is soaked through, and perfectly happy. Hot baths all round come next. Oilskins for dressing-gowns. And a hot meal at the Wherry Hotel with no cooking to do. And then we’ll take the bus to Lowestoft and see the fishing harbour. But first of all I must give William a dose of his cod-liver oil. He mustn’t catch a chill, poor little dog.’

The rain had stopped, and the sun was coming out as the harbour-master had said it would. Dorothea climbed up on the quay and shook the wet from her oilskins.

‘It feels rather nice to be on land just for a change,’ she said, and wanted to know if the Coots counted what they had been through that day as a proper storm.

‘Quite proper enough for the Teasel,’ said Starboard.

Tom looked at her. ‘Good bit of work,’ the harbour-master had said. But what would have happened if he had not had the twins to help?

1 A Roger is the Norfolk name for a sudden squall which makes a loud hissing noise as it comes sweeping over the reeds.