‘DON’T LOSE SIGHT OF THAT POST!’

25

The Rashness of the Admiral

‘THAT WRETCHED CURLEW must have been whistling the wrong tune,’ said Port.

The morning had brought them an easterly wind.

‘Fine for going up the Bure,’ said Starboard.

‘But we’ve got to get down to Yarmouth against it first,’ said Port.

Tom and the twins began their calculations over again. How long must they allow to get down to Yarmouth against the wind so as to be at Breydon Bridge exactly at low water?

Meanwhile the Admiral and Dorothea were looking through the larder and calculating how to make four eggs (all that were left) do for six people. There was fortunately plenty of butter to scramble them, but when breakfast was over, nobody would have said ‘No’ to a second helping.

‘We don’t know what time we’re going to get down to Reedham,’ said the Admiral, ‘but we’ll get all we want there.’

‘We’d better keep the tongue to eat on the voyage,’ said Dorothea. ‘It’s only a very little one anyway.’

In the end the navigators gave up all hope of making their figures agree. There were too many things to think of, the speed of the current, the speed of the Teasel when tacking, the speed of the Teasel when reaching, how much of the river would be tacking, and how much of it would let them sail with the wind free, and, on the top of all that, the wind itself seemed very uncertain.

‘There’s only one thing to do,’ said Tom. ‘We’ll sail right down to Reedham straight away. People will know there what the tide’s doing.’

‘So long as we’re not too late, nothing else matters,’ said Starboard.

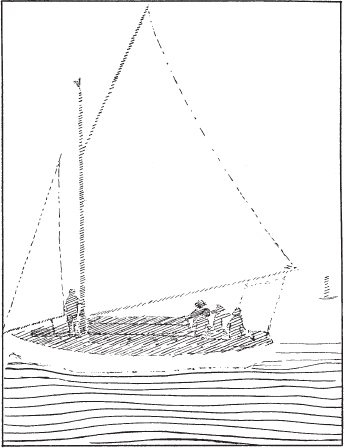

All down those long reaches by Langley and Cantley they sailed the Teasel as if she were a China clipper racing for home. Tom and the Coots were for ever hauling in or letting out the sheets to get the very best out of the wind. Dick and Dorothea took turns with the steering whenever the wind was free, but gave up the tiller to a Coot whenever it was a case of sailing close-hauled and stealing a yard or two when going about. The little tongue was eaten while they were under way, cut by the Admiral into seven equal bits, for William was as hungry as everybody else. Indeed, he did not think his bit was big enough, and the Admiral promised him that as soon as the Teasel came to Reedham he should have some more.

But as the Teasel turned the corner into the Reedham reach, and Tom was looking at the quay in front of the Lord Nelson, thinking where best he could tie up, above or below a couple of yachts that were lying there, they saw that the railway bridge was open, and that the signalman was leaning out of his window.

‘He’s beckoning to us to come on,’ said Dorothea.

‘He’s probably going to shut it for a long time,’ said Starboard.

‘Two trains, perhaps, or shunting,’ said Dick.

‘Well, I’m going through now, to make sure of it,’ said Tom. ‘It’d be awful to be held up.’

‘What about our stores?’ said the Admiral.

‘Let’s hang on till Yarmouth,’ said Tom. ‘We’ll have to stop there anyway.’

It was no use arguing. Tom had other things to think of. Beating against the wind, and carried down with the tide, he had to work the Teasel through Reedham bridge. Just as he came to it he had to go about and the tide swept the Titmouse round quicker than he thought it would. The Titmouse bumped hard against one of the piers. Tom glanced wretchedly over his shoulder, and winced as if he had been bumped himself.

‘She’s got that rope all round her,’ said Dorothea. ‘The bridge won’t have touched her really.’

‘Bad steering,’ said Tom. ‘My own fault.’

The bridge closed behind them. The red flag climbed up, and they knew that they might have had to wait a long time before it would be opened again. They were beating on towards the New Cut. Just for a moment they could see right down it, a long narrow lane of water, and, in the distance, the little road bridge, where the porters who open it catch their two shillings in a long-handled net.

‘Couldn’t we have stopped below the railway bridge?’ said Dorothea.

‘We can’t turn back,’ said Tom.

On and on they went, beating down the Yare against the wind but helped by the outflowing tide. And then, after being afraid of being too late, they began to be afraid of being too early. The Coots kept looking anxiously at Tom’s watch and at the Admiral’s, which she lent to Starboard because, as she said, she was tired of being asked the time. They kept looking at the mud that showed how far the level of the river had dropped since high water. It had dropped so little that anybody could see that the ebb must last for a long time yet.

They had just passed the three windmills, a mile and a half before the meeting of the Waveney and the Yare at the head of Breydon Water, when they had to change their plans once more.

‘It doesn’t look as if the ebb’s nearly half done,’ said Starboard.

‘We mustn’t get down there while it’s still pouring out.’

Last night they had been talking of what this might mean, and Dorothea saw the Teasel and the little Titmouse swirling, helpless in the tide, being swept down to sea under the Yarmouth bridges.

‘We’ll have to stop somewhere,’ said Tom.

‘The banks look unco’ dour,’ said Port.

‘Fare main bad to me,’ said Starboard, who talked broad Norfolk because of her sister’s talking Ginty language.

‘I’ll tell you what,’ said Tom. ‘We’ll go round into the Waveney and tie up by the Breydon pilot. He’ll tell us when to start again. …’

‘It said “Safe Moorings for Yachts”,’ said Dick. ‘And there’d be lots of waders to look at, with the tide going out.’

‘Why not?’ said Starboard.

‘Wind’s easterly,’ said Tom. ‘We’ll easily be able to sail that bit up to the pilot’s against the tide.’

‘All right,’ said the Admiral. ‘But what about stores? William and I are starving. And we can’t expect the pilot to have food for seven. Eggs? Who said eggs? We ate the last four. There isn’t an egg in the ship. And no bread. And both water-jars are empty. …’

Dorothea was looking at the map. ‘There are two houses marked near the mouth of the river,’ she said.

‘We could get milk and eggs at the Berney Arms,’ said Tom. ‘Water, too, probably.’

On and on they sailed. Already the wind seemed colder coming over Breydon, and they could hear the calling of the gulls. A red brick house came into sight on the bank, close above them.

‘That looks like a farm,’ said the Admiral. ‘Let’s tie up and ask here.’

‘I daren’t,’ said Tom. ‘Not with the Teasel, and the tide going out. No good getting stuck. Come on, Starboard. You take over. I’ll slip ashore in Titmouse. You sail round the corner. The pilot’ll tell you the best place to moor. I’ll be along with the stores by the time you get the sails down.’

He hauled Titmouse alongside, and dropped carefully into her, while Starboard took the speed off the Teasel by heading her into the wind. Port and Dick between them gave him the big earthenware water-jar. Dorothea handed down milk-can and egg-basket. The Admiral gave him the ship’s purse and told him to take what was wanted out of it.

‘Coming, too, Dick?’ Tom was bursting to have a little voyage in the Titmouse in these strange waters, and thought that Dick would be delighted at the chance.

But Dick was all for sticking to the Teasel. He wanted to get to the pilot’s. There might be another chance of seeing those spoonbills. He remembered the mudflats opposite the pilot’s hulk. He wanted all the time there that he could get.

Tom let go, and, as the Teasel sailed on, was left astern, fitting his rowlocks and getting out his oars. As they turned the bend, they saw him already rowing in towards the bank.

‘My word,’ said Starboard, ‘she sails a lot better without Titmouse to tow.’

‘Titmouse is very useful,’ said Dorothea.

‘All right,’ laughed Starboard. ‘We couldn’t do without her, but the Teasel does like kicking up her heels without a dinghy at her tail.’

‘There’s the Berney Arms,’ said the Admiral, and then, as they began beating down the last reach of the river, ‘And there are the Breydon posts.’

Ahead of them was black piling and a tall post marking the place where the two rivers met. Beyond it they could see where open water stretched far into the distance, with beacon posts marking the channel. They were at the mouth of the river. There, round the corner, was the old hulk of the Breydon pilot’s houseboat.1

‘We’ve never seen Breydon with the water all over everywhere,’ said Dorothea.

‘Just look at the birds,’ said Dick.

‘Can’t we just go down a little way to have a look at it?’ said Dorothea.

Port looked back up the river. There was no sign of Tom.

‘It’ll take Tom a long time to come round in Titmouse,’ said Dorothea, ‘and the Teasel sails awfully fast.’

Starboard was already bringing the Teasel round the end of the piling, and heading her up towards the Breydon pilot’s moored hulk.

‘What do the Coots think?’ said the Admiral.

‘We’d be able to get back all right with the wind as it is,’ said Starboard. ‘You can see by the way she’s going now.’

‘Do let’s,’ said Dorothea. ‘It must be all right if they used to have regattas on it.’

‘It is all right, really,’ said the Admiral. Far-off days were in her mind when Breydon Water was gay with yachts and she was listening for the crack of the winning gun in the commodore’s steam launch. She was seeing frilled parasols and rowing skiffs, and young women with little sailor hats, and spreading skirts and sleeves most strangely puffed above the elbows.

‘I don’t think we could possibly get into trouble if we went down as far as the end of the piling.’

‘Hurrah,’ said Dorothea.

‘Good,’ said Dick, who had the binoculars all ready in his hands in hopes of seeing the spoonbills.

‘All right,’ said Starboard. ‘In with the mainsheet. Ready about.’

The Teasel swung round into the wind, went about, and, with the tide helping her once more, beat down into Breydon Water.

‘Tom’ll see us all right,’ said Dorothea.

‘We’ll turn back in plenty of time,’ said the Admiral, and leaning on the top of the cabin roof, looked far ahead, seeing crowded boats, and remembered figures aboard them, where now was nothing but the salt lake, the posts marking the channel and the wild birds moving over the mudflats following the outgoing tide.

‘Just a little farther I think we might go,’ she said, when they came to the end of the piling that protects Reedham marshes from the river. ‘It isn’t really Breydon till it’s clear on both sides.’

On they sailed, beating slowly to and fro, against the north-east wind, but hardly noticing how fast the ebb was carrying them with it.

‘She can jolly well sail,’ said Starboard. Even the twins, though doubtful about what Tom would think of it, could not help enjoying themselves, sailing in this wide channel, leaving a red post on one side, and turning again when they came near a black post on the other, although, with the tide as it was, the water on both sides stretched far away beyond the posts.

‘There they are, I do believe,’ whispered Dick, looking through the glasses.

‘What?’ said Dorothea.

‘Spoonbills,’ said Dick. ‘They’re a long way off. But they can’t be anything else.’

‘Fog at sea,’ said Starboard, as they heard the foghorn of a lightship off the coast.

‘It really is just like the bittern,’ said Dick.

‘We’d better turn back now,’ said Port.

‘Just a wee bit farther,’ said Dorothea.

‘Two more posts and then we’ll turn,’ said the Admiral. ‘Wonderful it is, with that low bank of haze over Yarmouth.’

‘It isn’t as clear as it was,’ said Starboard. ‘Ready about.’ They came close up to a red post, sending a gull screaming from the top of it, went about, and stood away towards a black post on the other side of the channel.

Dorothea shivered, and laughed. ‘Cold wind,’ she said. ‘But isn’t this lovely sailing?’

‘I can’t see those spoonbills,’ said Dick, rubbing the lenses of the binoculars with his handkerchief.

‘It’s getting foggy over there,’ said Port.

‘It’s rather foggy here,’ said Dick. ‘It is like a bittern, that horn.’

And suddenly, almost before they knew it was coming, the fog was upon them. Yarmouth had disappeared, and the long line of those huge posts seemed to end nearer than it had. They could see only about a dozen … only six … and some of those were going … had gone. …

‘Turn her round,’ said the Admiral sharply. ‘We must get back to the river as quick as we can.’

But it was too late. The fog bank had reached them and rolled over them. The Teasel turned in her own length, and began driving slowly back over the tide, with the boom well out and the wind astern. But, already, her crew could not see the mouth of the river. They could see nothing at all except a black post close ahead of them.

‘Leave the post to starboard,’ said Port.

‘Teach your grandmother,’ said her sister.

‘Don’t lose sight of it until you see the next one,’ said the Admiral.

‘Not going to.’

‘We’ll just have to sail from post to post.’

There was something terrifying in sailing quite fast through the water with nothing in sight but a dim, phantom post that seemed hardly to move at all. That was the tide, of course, carrying them down almost as fast as they sailed up against it. It was quite natural, and nobody would have minded if only it had been possible to see a little farther. But now, alone, in this cold, wet fog, with everything vanished except that ghostly post, it was as if they had lost the rest of the world. The long deep hoots from the lightship out at sea and the sirens of the trawlers down in the harbour made things worse, not better. The fog played tricks with these distant noises, making them sound now close at hand and now so far away that they could hardly be heard. Dorothea knew that the Admiral was worried, and she listened anxiously for the note of fear in the voices of the others. She could tell nothing from their faces as they stared out into the fog.

‘I’m going forward,’ said Dick. ‘Even a few yards may make a difference in looking through the fog for that next post.’

He was gone, clambering carefully along the side deck with a hand on the cabin roof. On the foredeck, holding on by the mast, it was as if he were a boy made of fog, only of fog a little darker than the rest.

‘Keep your eye on that post,’ said the Admiral again.

‘It’s going.’

‘I can see it.’

‘Can’t see anything at all.’ Dick’s voice came from the foredeck.

Starboard was not accustomed to steering in the dark. And this pale fog was worse than darkness. Dimly, away to her right, she could see that post, but she had a lot of other things to remember. There was the tide trying to take the Teasel down to Yarmouth, and the wind blowing her the other way. What if the wind were dropping. She glanced over the side at the brown water sweeping by. The little ship was moving well, but oh how slowly she was leaving that post. She must not lose sight of it, until she had another to steer for. Was the wind changing? If it did change, why, anything might happen. Funny. There it was on her right cheek. She could feel it on her nose. A moment ago it was not like that. … Why, it wasn’t dead aft any more. …

‘Haul in on the sheet, Twin. She isn’t going like she was.’

‘The post’s moving,’ said Dorothea. ‘It’s going. Dick, Dick, can’t you see the next? We’ve passed this one. It’s gone. … No. … I can still see it. …’

‘Something’s wrong with the wind,’ said Starboard in a puzzled voice.

‘The post’s gone,’ said Port.

‘It was over there a moment ago,’ said Dorothea, pointing.

‘It can’t have been there,’ said Starboard. ‘More sheet in, Twin.’

‘We’re bound to see the next post in a moment,’ said the Admiral.

And then, suddenly, all five of them in the well, and William, tumbled against each other. It was as if someone lying under water had reached up and caught the Teasel by the keel. She pushed on a yard or two, stickily, heeling over more and more. She came to a standstill.

‘Ready about,’ said Starboard. Instantly Port let fly the jibsheet. But the rudder was useless. The Teasel did not stir. Starboard looked despairingly at the Admiral. ‘I’ve done it,’ she said. ‘I’ve gone and put her aground.’

‘It’s my fault,’ said the Admiral. ‘If you’d been alone you’d never have come down here.’

‘We might try backing the jib,’ said Starboard. ‘Or the quant.’

‘We’ll stay where we are,’ said the Admiral. ‘Nobody’ll run into us here. And anything’s better than drifting about in the fog.’

‘But what about Tom?’ said Dorothea.