JULY 6 Griffon Down

A very bad day.

Right on the heels of the deaths of Corporal Bulger and Master Corporal Michaud came the news that one of our Griffon helicopters had crashed. This was not caused by enemy fire. Flying of any kind does not allow for much in the way of malfunction or error before catastrophic events occur; flying helicopters in combat conditions magnifies this risk. It takes a special kind of person to crew these aircraft, a person who has both courage and skill, in ample measure.

We know that two Canadians are dead, but we are unsure as to their identities. This is causing a lot of anxiety on the FOB. The pilots and flight engineers are from the helicopter squadron. We will feel the pain of their loss as we do that of any fellow soldier. But the door gunners are infantrymen, from the same regiment currently deployed here. The combat troopers are desperate to learn if one of their friends is dead.

Everyone feels a little guilty at times like this. It starts when we hear that there have been casualties on our side. We know the likelihood is that they will be Afghan, because in this civil war it is the ANA that is taking most of the casualties. If that turns out to be the case, we are relieved, although no one would ever admit it. If we learn a Coalition soldier has died, we hope he is from another country.

The guilty feeling increases when it is confirmed that one or more Canadians have died. Now we are wishing for the death of someone we know less well. We are wishing for another Canadian family to be devastated instead of ours. None of us enjoys feeling that way, but none of us can help it.

No matter who these fallen Canadians are, they will be the first to die in one of our own helicopters. It has only been since the winter of 2009 that our squadron, equipped with Griffon gunships and Chinook transports, arrived in Kandahar. They have been flying continuously ever since.

I had thought that most routine Canadian FOB-to-FOB travelling on this Roto would be done in our own helicopters. I had emphasized this to Claude as a way of minimizing her worry before I left. And while some Canadians fly back and forth from the FOBs to KAF, the number of people we have travelling by convoy appears unchanged. It seems our aircraft and crews have been integrated into the overall war effort and not specifically assigned to us: our Griffon crashed at an American FOB.

Griffon gunship door gunner

So it was already a bad day, and it came to a bad ending. At last light, as I was working in the staff lounge, I heard a hissing sound I recognized. A rocket was flying overhead and was a second or two away from impact. I threw myself against the wall, waited for the detonation and then ran for the bunker. The rest of the medical team had been on the bunker’s porch. When I got there, they were scrambling to get inside. We got our helmets and frag vests on and waited for the all clear.

It looks like “rocket season” is upon us.

Addendum, July 7 (morning): We now know the name of one of the dead Canadians. He is Master Corporal Patrice Audet, of the 430th Tactical Helicopter Squadron. There is no information about his duties on the aircraft, but there are already recriminations against his branch of the service.

Our helicopter crashed on takeoff. “Experts” have been on the CBC news explaining how this was predictable because our pilots, our aircraft or our procedures are not good enough for the kind of combat operations we are flying here in Kandahar province. Apart from being extraordinarily insensitive—coming even before the bodies of our dead comrades arrive home—this criticism is Monday-morning quarterbacking at its worst.

In this heat, a helicopter’s blades generate far less lift than they do in colder, denser air. This makes the aircraft harder to control and much less forgiving of even a tiny misstep at low altitude. The dust is so bad that pilots land and take off in a cloud through which they can see nothing. By themselves, these environmental factors would make for the most challenging flying conditions a helicopter pilot can face. And our pilots also contend with the enemy threat. Takeoff and landing, the trickiest manoeuvres in flying, are also the occasions when helicopters are most vulnerable to anti-aircraft fire.

In spite of these potentially lethal hazards, our air crews keep flying. In doing so, they give us an enormous edge over the Taliban: they resupply us in the most difficult terrain, they provide fire support that drives off Taliban attackers and they shuttle us around the battlefield, safe from IEDs.

Helicopters crash—even with the best pilots, flying the best machines, in the best of conditions. This is combat flying, so we should be prepared for the inevitability of incidents like this. I am sure that when this war is over our helicopters will have had an admirable safety record. I will not hesitate to get on one for the rest of my tour.

Addendum, July 7 (afternoon): The worst fears of the infantrymen here have come true. So have mine.

Corporal Martin “Jo” Joannette was a member of the Third Battalion, Royal 22nd Regiment. These are the Van Doos, the French Canadian infantry regiment that is serving here now. A lot of people on the FOB, including me, knew Jo. Though still a minority, veterans make up an important proportion of the troops deployed on this rotation. That Jo and I met during my previous deployment is no more than a minor coincidence, but it makes writing this entry physically painful.

Jo and I were together at Sperwan Ghar, the first FOB I served at in 2007. He was the combat team commander’s LAV (light armoured vehicle) driver. He went on every mission, big and small, that we ran out of that FOB. His vehicle was struck by an IED twice, had a near miss a third time, and he was under direct enemy fire numerous times. He came out of it all without a scratch. He had served another tour in Afghanistan before that. Knowing he came through so many close calls makes it somehow harder to accept that we have lost such a superlative soldier.

What I remember most about Jo was his uncanny ability to coax balky motors back to life. The internal combustion engine is something I know nearly nothing about, but Jo knew the inner workings of his armoured vehicle better than I know anatomy. He was the go-to guy for the combat team when it came to engine problems, and he was always ready to help.

In his photograph (at the back of this book), you will notice that Jo does not wear the traditional green beret of the infantry but rather the maroon beret of the airborne troops. So I close with the traditional parting wish of the paratrooper: “Light winds and soft landings, my brother.”

JULY 7 | Junior

On the two-way rifle range you will not rise to the occasion. You will sink to the level of your training. The combat arms attracts more than its fair share of big guys. Individuals of smaller stature stand out. Corporal Nicholas Cappelli Horth (the missing hyphen is intentional) stands out, in more ways than one.

—RSM BRIAN MCKENELLEY, Second Battalion, The Irish Regiment of Canada

Corporal Nicholas “Junior” Cappelli Horth

Although he is based here at FOB Ma’Sum Ghar, I had the opportunity to meet him before coming here. He is the medic assigned to the provincial reconstruction team, and these guys get around a fair bit. Whenever his team came to FOB Wilson he would pop by the UMS to look in on his medical brethren. He participated in some of the patient encounters I have described.

I know. In this photograph he does not look older than twelve, and I doubt he weighs more than fifty kilograms soaking wet. His nickname, “Junior,” seems almost preordained. But he is twenty-two and one of the more impressive young men you will ever meet. The gear he carries on patrol weighs almost as much as he does, but he never falters. It must be said that he is in amazingly good shape, being a marathon runner. He is also the prototypical “good soldier.” He always has a positive, can-do attitude.

His skills and attitude made him pretty much the perfect “garrison soldier.” In other words, he had everything the army looks for during training: fitness, drive, teamwork and smarts. But how will the aptitudes demonstrated during training translate when under fire? That is the question on everybody’s mind as a unit heads to war. For Junior, we got the answer today.

The provincial reconstruction team had been on a patrol not far from our FOB. The team was in the process of clearing a road, searching for IEDs. Junior was somewhere in the middle of the column of soldiers. An Afghan civilian on a motorcycle began to overtake them. Before he was allowed to go on, he was stopped and searched. He checked out: a villager, making his way to his fields.

The villager got back on his motorcycle and began to pass the soldiers. When he got level with Junior, a Taliban triggerman detonated a “directional” IED. The rear half of such a device is high explosive. This would not be lethal beyond a few feet. The front half consists of hundreds of metal fragments, which the high explosive will project forward at high speeds. You could think of a directional IED as a gigantic shotgun firing massive pellets.

The directional IED was a metre from the Afghan villager when it went off. Junior was two metres farther away. At such close range, a directional IED massively damages the human body. The villager had most of his mid-section blown apart. Junior was thrown to the ground, covered in blood and pieces of flesh, but the Afghan’s body had created a “blast shadow.” Junior’s ears were ringing, but he was otherwise unhurt.

What did Junior do then? On a patrol, soldiers are assigned an “arc of responsibility,” that area of the 360-degree circle around the patrol that they must watch. By the time Junior had finished rolling on the ground, he had his weapon up and facing outwards, covering his arc. In the time it took for the blast to stop acting on his body, he was back to being a fully operational combat soldier.

A patrol’s first priority when it comes under fire is to defeat the enemy. Even if there are wounded soldiers who need care, the combat medics will first help to drive back the enemy, “winning the firefight.” We are soldiers first, and Junior had reacted exactly as he had been trained to.

Although the IED attack was not followed up with gunfire or grenades, the patrol was still in grave danger. There were signs that the Taliban had laid secondary IEDs, additional mines whose purpose is to kill medics and others coming to assist those wounded by an initial blast.

When the patrol had secured the area, Junior rendered whatever aid he could to the villager. Before this, he had radioed the UMS to prepare us to receive a critically wounded patient. I got the team together and briefed them on the patient’s possible injuries, and we set up our IVs and other gear. Unfortunately, the man was long dead by the time we got to him.

Junior reported to the UMS when the patrol returned to the FOB. He still had his smile and his positive attitude . . . but his eyes had a slight watery sheen, and his voice had a touch of a tremor. I took him outside the UMS to have a word with him privately.

What do you say to someone who has come as close to dying as it is possible to do? You start by telling him how happy you are that he is okay. You follow that up with statements that are “normalizing.” This means that you list the possible reactions a normal human being might have after an event like this, so that he understands that what he is feeling is to be expected. Then you open the door for him to come and talk to you about those reactions if they prove to be distressing.

Then you step back, give your comrade some space and hope that he will prove to be one of the many who come through something like this psychically intact. And not one of the few who will be damaged forever.

Addendum, July 31: I am leaving FOB Ma’Sum Ghar in a few days. I have spoken to Junior a number of times since his close call. He seems remarkably well. His sleep patterns got back to normal three days after the incident and, a week ago, he had a dream in which he saw the Afghan villager who was killed. He could not recall much about the dream except that it had not been upsetting.

He has had a couple of other emotionally tough days, one of which I will describe in some detail later, but I think he will come through this war without any long-term emotional ill-effects.

JULY 8 | MRE: Medical Rules of Eligibility

One of today’s serious casualties was unusual, as war zone casualties go, because he was suffering from blunt trauma. This is the kind you get when your body is thrown against something hard. Whereas penetrating trauma is relatively simple to manage—plug the holes, stop the bleeding, get them breathing, ship them out—blunt trauma is a much more cerebral exercise. Patients have no holes or lacerations indicating where the damage lies. They must be examined much more carefully so that no serious injuries are missed. Keep that in mind as I present today’s interesting case.

As was the case at FOB Wilson, the perimeter security on the camp is the responsibility of a private company. One of their men was involved in a head-on collision with an American armoured vehicle. He was driving a pickup truck, so he was the loser in this exchange.

There was no external bleeding, and the patient was not having any difficulty breathing. He had no bruises, his vital signs were normal and ultrasound examination of the chest and abdomen were negative. He had no neurological symptoms, meaning that he had normal strength, sensation and movement in all four limbs. His only complaint was pain at the top of his head and in his cervical (neck) spine. He was alert and oriented, and he described having been projected into the roof of his vehicle.

A case like this could not be more straightforward. The accident had delivered a tremendous amount of “axial load” onto the patient’s cervical spine. This is the same thing that happens when people dive into shallow water. These individuals often break their cervical spines and end up paralyzed from the neck down. The medical team must therefore immobilize the patient’s spine immediately and keep it secure until X-rays or a CT scan can be done to rule out the presence of a fracture.

Pretty basic, eh? Not to some goof at KAF. The message we got back was: “We’re busy. Send the patient by road.”

I hit the roof. We are now doing helicopter medevacs for Canadians who need nothing more than a couple of stitches. The message I was getting was that this Afghan, with a potentially devastating injury, was not worth the same consideration. He may have been, for all intents and purposes, a mercenary, fighting for our side only for the money. That is irrelevant. He had been injured as a byproduct of the war. As a result, his care was our responsibility. Had he been a civilian or a Taliban soldier, I would have treated him the same way.

I am happy to report that this aberrant behaviour was limited to a single individual at battle group headquarters. I barked once (via a one-paragraph e-mail, dripping with sarcasm, venom and threat), and the air medevac was approved.

JULY 10 | Tac Recce: Tactical Reconnaissance

A quiet day—only a few patients, none of them critically injured.

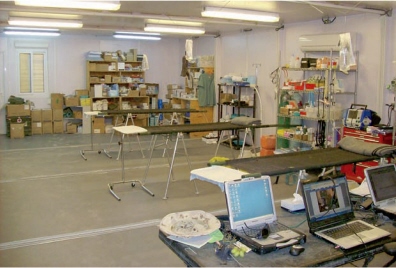

It looked as though I would not have much to write about, but that changed shortly after lunch. Two distinguished-looking gentlemen wandered into the UMS. One of them introduced himself by saying, “We are here to replace you.” I had no idea who he was so I flippantly answered, “Yeah, right! In my dreams!”

It was a poor choice of words. I was addressing Commander Robert Briggs, the head doctor of the rotation arriving in September. He was accompanied by Major Graeme Rodgman, who will be in command of the FOB medics. They were performing a “tactical reconnaissance,” a direct eyeballs-on look at the combat area. As part of this recce (pronounced “wreck-ee”), they had come to Ma’Sum Ghar to check out the FOB UMS, to learn what our capabilities were and to see where their people would be deployed starting this September. I showed them the UMS and our quarters, and we discussed the medical work of the FOB.

Not wanting our guests to be bored, Master Seaman Turcotte (one of the Bison crew commanders) decided to provide us with a chance to show them how sophisticated the care in our UMS could be. So he got on top of his vehicle . . . and fell off.

A Bison is not a small vehicle. A fall from the top generates precisely the kind of kinetic energy necessary for one of those blunt trauma cases I described in the previous entry. To enable us to display even more of our skills, MS Turcotte helpfully landed on his face. This gave us a tricky facial laceration to repair as well. This was an act of selfless devotion to the job, one that we will be reminding MS Turcotte about for some time.

I got the patient sewn up quickly. Apart from the cuts on his face, he had no other apparent injuries. That left the non-apparent injuries he might have suffered in his chest or abdomen. This presented me with the opportunity to give an impromptu lesson in EDE to my two visitors, neither of whom were familiar with the technique. They were interested in the ultrasound examination, so we discussed ways they could integrate this into the practice of their physicians.

We ended the visit with a run up to the hilltop observation post. You can see most of Zhari-Panjwayi from up there. You can also see where 85 per cent or more of the Canadians who have been killed in Afghanistan met their end. Neither of my colleagues had fully appreciated that before.

I brought them back to the UMS, and we talked about a few more things before it was time for them to go. I wished them well as they headed back to KAF.

I hope they have the most boring tour imaginable.

JULY 11 | Visitors

Two notable encounters with visitors today.

MORNING: THE QUIET ONES

Every morning, right after I wake up, I run to the top of Ma’Sum Ghar a few times to get my daily exercise. It is a steep climb, and I need to breathe a bit at the top before coming back. I usually say hello to the men manning the observation post located there. Depending on the situation, they could be from the private security company or some of our own troopers. Not today.

The men looking out over the Panjwayi valley this morning were unlike any you would ordinarily see on the FOB. They had beards and longish hair. They wore no insignia of rank or unit, no name tags. Their weapons had silencers and more sophisticated scopes than the ones on a standard infantry rifle. Their body armour was custom-made and lighter than that normally issued. This represented a tradeoff: less protection in exchange for increased mobility. Their demeanour, while polite, was distant. They asked no questions and offered no information about themselves, and introductions yielded only a first name.

The Quiet Ones had come to Ma’Sum Ghar.

When a soldier joins the combat arms, he is timid. The environment is new, his instructors are terrifying, and the skills he is being asked to master are foreign. No one feels self-confident in this situation.

When a soldier finishes basic training and can now call himself an infantryman, the opposite is true. He feels like a Dangerous Man. Even if he had no self-confidence before joining the army, he has a lot now.

If the soldier receives further instruction, such as paratrooper or reconnaissance training, his self-confidence grows even more. He may even become somewhat annoying, adopting an aggressive, in-your-face attitude. I can state this with some assurance, having been that annoying guy when I graduated from the Combat Training Centre. Most soldiers mature over the course of a few years, retaining the self-confidence while shedding the bluster.

There are a few soldiers who choose to go beyond the advanced infantry training available in the regular battalions. They go on to become some of the most skillful and lethal soldiers in the world. They are our best and they take a backseat to no one, regardless of what you may have heard about the British SAS, the American Green Berets or SEALs, or the Israeli Commandos.

The paradox is that, with this additional training, the linear relationship between training and bravado is broken. Instead, the opposite occurs. You can be in a room with several of these men and still feel like you are alone. Far from bragging about their considerable accomplishments, they prefer to fade into the walls and they do so quite effectively.

I had the opportunity, a few weeks before coming back to Afghanistan, to train a number of these men in some advanced emergency medical techniques. Even in that setting, with a man who was a veteran as their teacher, they kept to their strict code of self-effacing silence.

The Quiet Ones are not assigned to any particular FOB. Rather, they wander around Afghanistan on various assignments. They will not get into major confrontations with the Taliban. They will not be involved in reconstruction work. They will not help rid the country of IEDs. What they will do is watch. Silently. And with infinite patience.

The Quiet Ones are looking for a face, one that has been identified beyond any reasonable doubt. More often than not, their patience is rewarded. The face suddenly appears in their binoculars or telescopes. Just as quickly, the face disappears. But now they know where the face is.

The culmination of all that watching is coming soon. The Quiet Ones are human, and they are no doubt feeling excited and apprehensive about what is to follow, but you could not read that on their faces. Their conversation is muted, limited to an exchange of information as the plan is developed. Their faces remain neutral.

The Quiet Ones continue to watch, until the most propitious moment. Then they move, in the same silence and with the same patience they displayed while they watched.

Then they strike.

When I was at my first FOB during Roto 4, there was a poster on the wall showing the faces of the Taliban commanders in our area of operations at the start of the rotation. Roughly half of the faces were crossed out with a red X.

Thanks to the Quiet Ones, the life expectancy for Taliban commanders in Zhari-Panjwayi is not very good.

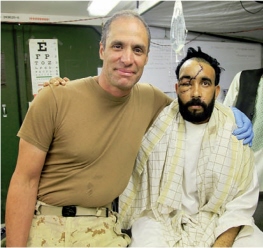

AFTERNOON: THE PRISONER

The ANP captured a Taliban soldier last night. The circumstances of that capture are unclear to me, but the Talib was in a prisoner cage this morning. It is also unclear to me how he got out of that cage, but get out of it he did. He then attempted to flee at high speed. The ANPobjected to this. An AK-47 bullet shot through the Talib’s left leg settled the squabble in the police’s favour.

It was a nasty wound. The bullet entered just above the calf muscle and exited in the middle of the leg, just below the kneecap. When a high-powered bullet such as this goes through a limb, it shatters the bone and causes a small explosion to occur where the bullet exits. While the entry wound was the size of the bullet (smaller than a dime), the exit wound was somewhat larger than a kiwi.

This was bad news for the patient. There are two bones in your leg: a small one on the outside that you can do without—the fibula— and a larger one on the inside—the tibia—that carries all your body’s weight. The part of the tibia closest to the knee had been destroyed. When I explored the exit wound, the bone seemed to end five centimetres short of where it should have. I could not detect a pulse in the foot, indicating that the patient’s blood vessels had also been damaged.

If a patient was to have a chance to keep his leg he needed surgery as soon as possible, so we called for a helicopter medevac, priority Alpha. We controlled the bleeding, bandaged the wound, splinted the leg and gave him intravenous antibiotics and pain medication. When I was done, I allowed two military intelligence types to question him.

It was interesting to watch this process. If you have visions of the interrogation sessions straight out of a James Bond movie, you could not be further off base. I had the impression I was watching the neighbourhood cops questioning a well-known and mostly harmless delinquent. The questioner was only mildly stern. He did not touch the patient, even when the patient tried to doze off. His questions were factual, and neither his words nor his tone were ever threatening. His companion took notes but said nothing.

Within thirty minutes we got word that the medevac choppers were arriving. I took a minute, as I always do in these situations, to tell the prisoner that we were Canadians and that we had taken very good care of him. I hoped that this would convince him to turn against his former Taliban mentors. Failing that, I hoped he would remember our kindness if a Canadian ever became his prisoner. Even if neither of these results ever occurs, this doesn’t change my approach: I will fight this war as hard as I can, but I will fight humanely.

JULY 14 | The Elements, Part 2: Earth

The FOBs are on the front line of a war zone. Although things are better than they were during Roto 4, our existence here is still one of physical discomfort. I would be denying a key part of the soldiers’ experience if I did not recognize that.

I have already described the effects of the heat. I am shielded from the worst effects of this because both the UMS and my bunker are air-conditioned. But none of us can get away from the dust, which is all-pervasive. It is a fine powder that coats everything it touches. Every footfall raises a small puff. Even in this relatively windless area, the dust seeps into the most remote recesses of our buildings. Master Corporal “Red” Ricard wages a daily battle, armed with mop and broom, to keep the floor of the UMS clean.

The dust also seems to impregnate all our belongings. Food becomes gritty before the meal can be finished. Clothing comes out of the dryer with sand trapped in the fibres. Even right after stepping out of the shower, you get the feeling that you are not completely clean.

It is in the air, however, that this phenomenon is most apparent. There was a stretch of three consecutive days last month when the dust in the air was so thick the sky looked like grey milk. There is menace in such a sky: dust is responsible for nearly all the “medevac red” periods, when our helicopters are grounded.

These are times of considerable anxiety for a FOB doc. I can do anything the patient needs for the first thirty to sixty minutes of resuscitation care. After that, the treatment options available to me are exhausted. If I have been unable to stabilize the patient, as would be the case with ongoing bleeding into the chest or abdomen, he or she needs to be in the O.R. at KAF. These patients need a blood transfusion and an operation, neither of which I can offer here. If the medevac birds are not flying, I might have to watch one of our soldiers bleed to death.

JULY 15 | Stand To

Stand to: the procedure whereby all soldiers on a base, regardless of their normal tasks, will grab a weapon and take a defensive position. Used when the base is under imminent threat of attack.

The FOB Ma’Sum Ghar combat team left for an operation at first light this morning.

It is impossible to conceal the departure of a dozen or more tanks and other armoured vehicles. The Taliban spies will have noted this. Usually, they are more concerned with where the combat team is headed. This time, it seems they focused their attention back towards the FOB.

It is unusual for the Taliban to attempt a ground attack against one of our FOBs, but it does happen. During one such attack against Ma’Sum Ghar during my last tour, the gunfight lasted so long that the soldiers on our perimeter began to run low on ammunition. The FOB commander ordered the cooks and the medical staff to reinforce them.

At today’s unit commanders meeting, we were told that our intelligence had reported the FOB being observed, possibly with an eye to a ground attack. Given our reduced numbers, the FOB commander called on all of us to be more vigilant than usual and to be prepared to repel any assault.

I reflected on our previous experience and thought that we could do better this time. The cooks and medical staff, though more than willing to get into a gunfight, are initially tasked to defend the UMS. On Roto 4, it had not been clear where the commander had wanted the perimeter reinforced. I mentioned this to the FOB commander, and he agreed to come by later to give us a precise assignment.

But once an infantryman, always an infantryman. When I got back from the meeting I went for a quick walk up the hill behind the UMS to look at where I could best place Red, the remaining Bison crew (one crew went on the operation) and myself to defend our little patch of ground. As frightening as it would be to get involved in a close-range gunfight, I found that prospect far preferable to sitting in our bunker, unable to see outside and waiting for someone to come to the door.

Before the FOB commander could come to visit us, the Taliban hit us with another rocket. This one landed right on the helipad, narrowly missed one trooper, bounced up and over another trooper and then slammed into one of the concrete walls but did not detonate. Had we been running a helicopter medevac or personnel transfer at the time, it could have done a lot of damage. The EOD team went to get the rocket and placed it on the other side of the little hill located right behind the UMS. How comforting. They plan to BIP it tomorrow.

The threat of a ground attack takes everybody’s anxiety up a notch. It is one thing to know that there are people here who want to kill us. It is another thing to contemplate that they might come and try it tonight.

JULY 16 | Terror

When you’re wounded and left on

Afghanistan’s plains,

And the women come out to cut up what remains,

Jest roll to your rifle and blow out your brains

An’ go to your Gawd like a soldier.

—RUDYARD KIPLING, “The Young British Soldier”

The day started badly. When Red and I came into the UMS and checked our communication devices, we saw that we were in “coms lockdown.”

This meant that one of our own was dead. As bad as that was, things soon got much worse.

One of our recce patrols had been deployed southeast of here onto a mountain known as Salavat Ghar to support the operation that jumped off yesterday. It is their job to explore the battlefield, to detect the enemy and report their location to the main body of our troops.

The recce troopers are highly skilled and extremely fit. During a pre-deployment exercise I underwent prior to this mission, I was taken on a patrol by one of these men. He was so adept at camouflaging himself and was able to move through the bush so quietly that I felt I was walking with a ghost. Usually when these men go out, the Taliban have no idea they are there. Today was one of the rare exceptions to this rule.

The recce soldiers were establishing an observation post when one of them, Private Sébastien Courcy, tripped a mine. The explosion threw him off a cliff. At the same time, the patrol was under fire from a Taliban mortar. After the blast, the other members of the patrol had no idea where Private Courcy was.

That news travelled back to the FOB at lightning speed. As bad as we feel when one of us is killed, this was much, much worse. Our comrade might have been captured. It has been said that the Taliban do not take prisoners. That is inaccurate. What they do not do is allow prisoners to live. And the way they torture prisoners before killing them is nothing short of barbaric. When we heard the first reports about our missing recce trooper, we were terrified that this would be his fate.

Within an hour of the initial reports, we had more details. It was uncertain whether he had been blown off the mountain by an explosion or if he had slipped off while running, but there was no doubt that our comrade had fallen a long distance, to his death. It was nonetheless some small comfort that his body was found by Canadians, and not by the enemy.

THE POWER OF FEAR

Terror works.

If it did not, terrorists would not use it. By torturing and beheading their captives, al Qaeda and the Taliban extremists demonstrate how far they are willing to go to achieve their goals. When they threaten the local civilian population with reprisals if those civilians co-operate with us, those threats are often effective.

Occasionally, I hear a Canadian soldier complain that the Afghans are not doing enough to ward off the Taliban themselves. When I hear that, I get annoyed and I say so. For a member of a heavily armed Canadian battle group to compare himself to unarmed Afghan civilians is beyond ridiculous. Our experience of terror in Canada is limited, mostly confined to the 1963–70 bombing-and-murder campaign of the FLQ. We cannot know how we would react if we were constantly subjected to it. But the historical record is clear. When a powerful group terrorizes a population, nearly all the members of that population—regardless of ethnicity, nationality, religion or anything else—try to get along with those who are able to harm them. This is true even if it is virtually certain that the intent of those in power is to kill everyone. The key word in that last sentence is “virtually.” People in these situations will cling to the slightest hope that they might survive, and they will go to unimaginable lengths to appease those who might kill them rather than commit suicide by fighting them.

But if terror can make people do unspeakable things, is it a source of real power? Only in the short run. Terrorists can cause unimaginable suffering and be very difficult to oppose, but they cut themselves off from any legitimate claim to authority. All through history, tyrants have done their best to terrorize populations. They have always fallen.

JULY 17 | Boredom

Against boredom, the gods themselves struggle in vain.

— FRIEDRICH NIETZSCHE

Reading the entries in which I describe dealing with multiple war casualties, you might get the impression that those days are busy. Nothing could be further from the truth. Even a MasCal with multiple casualties only occupies me for an hour, two at the most if we include cleanup and debrief. After that, all the casualties are either evacuated or have been treated and released. The busiest day here does not begin to approach an average shift in a large emergency department.

It would also be a mistake to assume that the presence of imminent danger, which has loomed large in the previous two days’ entries, is in any way entertaining. As described in “Downregulation” (June 17), soldiers get used to this quickly. It is common to feel bored while being scared. But as boring as even my busiest day can be, one group of soldiers are a lot worse off than I am.

Individuals who have drawn shifts in the various observation posts (OPs) that ring the FOB have the worst job to which one can be assigned here. It combines the need to be constantly vigilant— a source of stress and fatigue—with the need to look at the same unchanging terrain for hours—a source of yet more stress and fatigue. If wars are 95 per cent boredom and 5 per cent terror, OP duty is 99.99 per cent boredom and 0.01 per cent “What the fuck was that?”

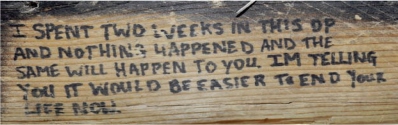

The graffiti one encounters in an OP reflects the mind-numbing boredom of hours spent watching the Afghan dust . . . get dustier: “I spent two weeks in this OP and nothing happened and the same will happen to you. I’m telling you it would be easier to end your life now.” A few feet away, we find the franco version: “Oubliez pas vous êtes ici pour un crisse de boutte.” (“Don’t forget you’re gonna be here for a fuck of a long while.”)

Observation post philosophy

A third one says: “They should really change that military commercial so that it says: Fight boredom. Fight bullshit. Fight each other.” The commercial in question shows Canadian soldiers saving civilians, either on search and rescue or peacekeeping operations. The captions are: “Fight fear. Fight chaos. Fight distress.”

Our army is at war, yet it produces a recruitment ad that does not mention that key detail. A little disconcerting, that.

JULY 18 | Middle of the Night Conversion

Catchy title, eh? A reference to our converting the heathens? Nope. The Coalition forces are respectful of the Islamic faith. This is about a completely different kind of conversion.

At 0230, the phone linking us to the command post rang and Red answered it: “Afghan soldier. Unconscious. ETA five minutes.” Red and I bolted for the UMS. Corporal Bouthillier, the Bison medic, joined us a minute later. A minute after that, a jeep drove up. The unconscious patient was quickly moved into the UMS. Corporal Bouthillier started an IV, and Red checked the vital signs while I proceeded with my examination. When I finished, I had a patient without any detectable injuries or signs of a drug overdose but who was deeply unconscious. Stumped, I went outside to question the other Afghan soldiers.

The soldier had been on a patrol that had returned to the FOB at 0200. A half-hour later, he suddenly collapsed. They had not come under fire during the patrol, and he had seemed fine until that point. The patient had had a similar episode six months earlier and been evacuated to KAF. He had been kept there for a couple of days, but no diagnosis had been established. I went back in the UMS and carefully examined the patient again to ensure I hadn’t missed any subtle signs of disease or injury. Finding none, I began to wonder if I was dealing with a “conversion reaction.”

Sometimes called “hysterical conversion reaction,” this is a psychological state in which stress produces a direct effect on the body: the mental feeling is “converted” into a physical symptom. This can take the form of paralysis, blindness or a number of other manifestations. The patient has very little control over a conversion reaction. It is quite different from malingering, which is the conscious attempt to fake an injury or disease.

The societal demand on Afghan men to be good fighters is extreme. To fail as a soldier is to fail at everything it means to be an Afghan man. During my previous tour, there was only one Afghan soldier who I thought might have had a conversion reaction. I was reluctant to advance the diagnosis in this case. An emergency physician should always hesitate before deciding “it’s all in his head.”

I then noticed that we had not checked the patient’s temperature, the most commonly forgotten vital sign. Since an unconscious patient cannot co-operate with an oral temperature, I ordered Red to use the rectal thermometer. As Red touched the thermometer to the patient’s anus, the buttocks clenched tightly. Seeing that, I began to relax. The patient might be unresponsive, but it was unlikely that he was sick. When Red tried again, the patient opened his eyes to look at me, then quickly shut them again.

At that point, the jig was up. While this patient may have had a conversion reaction when this all started, he was now malingering. I told the interpreter to tell him to get up and walk out. Within a couple of minutes, he did exactly that. No trip to KAF this time, bucko.

JULY 19 | Haji Baran

The title of today’s entry is based in part on one of the Five Pillars of Islam. The teacher in me cannot resist telling you about all five.

The shahadah is a verbal expression of belief that recognizes the singular nature of God and accepts that Muhammad was God’s messenger.

Zakat is compulsory charity. In Islam, you get hit for 2.5 per cent of your total income. The key question is how low your income has to be before you can cross over from payer to payee. The answer is clever, in that it has remained the same since it was established: three ounces of gold. Today, that would be a per annum income of $3,139.29 in Canadian dollars.

Salat is the requirement to pray five times a day: at dawn, noon, mid-afternoon, sunset and night. Each salat is performed facing towards Mecca, the Saudi Arabian city that is the holiest place in the Muslim world.

Sawm is compulsory fasting during the month of Ramadan, when Muslims must abstain from food, drink and sexual intercourse from dawn to dusk. The fast is a way to empathize with those who are hungry and to express gratitude to God for his gifts—kind of a Thanksgiving in reverse.

The hajj is a pilgrimage to Mecca. All Muslims who can afford it are obliged to do this at least once in their lifetime. After a Muslim makes the hajj, he or she is known as a haji or a hajja. This is a high honour in the community, so much so that many small villages in the Panjwayi are named “Haji-something,” in homage to the one member of their village who went to Mecca.

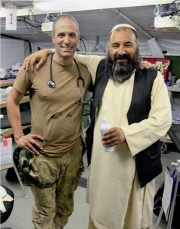

This concludes the educational session; onward with current events. One of the Afghans we most depend on in the Panjwayi is Haji Baran, the district leader. I had seen him a couple of weeks ago for a stomach ailment, which I diagnosed as gastric reflux (heartburn) and treated with antacids.

Like many powerful people, Haji Baran is mindful of his special status. The first time we met, he had gone out of his way to explain to me how he had no confidence in Afghan doctors and would only be treated by Canadian M.D.s. This is a common thing for Western physicians to hear when we are overseas. It is an unfortunate example of reverse racism, and I am always a bit offended by it. I am sure most of my developing-world colleagues are doing the best they can with what they have.

Haji Baran returned today, complaining of chest pain. This placed me in a quandary. He had been seen at the FOB for chest pain a few months ago and had been helicoptered to KAF, where he underwent a standard North American cardiac workup. The workup had been negative, and Haji Baran was returned home without any cardiac medications. There was a strong probability that he was looking forward to the same treatment today. He had intimated as much during his last visit.

A satisfied patient

The Canadian officer who had come with him remained neutral on the surface. It was obvious, however, that the happier I made my patient the better things would be for our mission. Given his stature in the community, you could make an argument that another helicopter medevac might be money well spent in terms of earning his loyalty.

The complicating factor was an e-mail we received yesterday informing us that the medical rules of eligibility had been tightened up considerably. As things stood today, there was no way Haji Baran would qualify for a helicopter medevac.

What to do? There is a simple action that goes a long way towards convincing patients that your attention is focused on them. All you have to do is sit down. Numerous studies have shown that physicians who interview patients while seated are perceived to have spent twice as long with the patient as they actually did. Patients are far more satisfied with these encounters. When Haji Baran walked into the UMS, I sat us both down and proceeded with the lengthiest and most thorough interview I have done since medical school. When we were done I was convinced that Haji Baran was suffering from nothing worse than more heartburn. More importantly, he was convinced as well.*

JULY 20 | Tanker

I was run over by a tank once.

In the summer of 1980, I was at the Combat Training Centre completing the process of becoming a CF infantry officer. All my training until then had been done with small groups of foot soldiers. In this last phase, we had to learn how to operate in conjunction with the other branches of the combat arms: the artillery and the tanks.

In the June 21 entry, I described the relationship between the infantry and the artillery. The infantry go out and get into a fight. When they figure out where the bad guys are, the artillery is called to blow them to ratshit. It is a long-distance affair, the parties being at either end of a radio set.

The infantry’s relationship with the tanks is very different. Since World War One, tanks and infantry have always fought side-by-side on the battlefield. The affiliation is much more intimate than with the artillery.

The tanker instructors assigned to us wanted to make this point forcefully. They achieved this the first day we were with them by having us lie down in a straight line on a road and driving over us with a tank. I do not know what I learned by having dozens of tons of metal pass less than a foot from my nose while treads clanked a few feet on either side of me. I did listen attentively to everything the tankers said after that, so that they would not want to run over me again. That may have been their objective.

When civilians see a Leopard tank for the first time they cannot help but be overwhelmed by the size of the main armament. Pointing phallicly forward is a 120 mm cannon, not much smaller than the 155 mm M777 I have described earlier. This gun can shoot a massive shell several kilometres and destroy even well-protected Taliban bunkers. This massive firepower is great, but the Leopard’s contribution in this war goes further. The complete story takes a bit of explanation.

Although our initial deployment to Afghanistan began in Kandahar province, this lasted less than a year. By 2003, the mission was focused on providing security to the capital, Kabul. Our soldiers were based outside the city at Camp Julien. We would conduct some combat operations, but mostly we patrolled Kabul and the surrounding area on foot and in jeeps.

In October 2003, Sergeant Robert Short and Corporal Robbie Beerenfenger were conducting one of these patrols on the outskirts of Kabul when their vehicle hit a mine. By the time they were discovered, both of them were dead. In January 2004, Corporal Jamie Murphy was killed while patrolling downtown Kabul, when a suicide bomber jumped onto the hood of his vehicle and detonated himself.*

The vehicle implicated in both these incidents was the Iltis jeep. This was a “soft skinned” vehicle, meaning that it was not armoured and offered virtually no protection against IEDs and other explosives. Following these deaths, the CF was pilloried for sending soldiers to Afghanistan without such protection.

There was some justification for this criticism. The Afghan resistance had made extensive use of IEDs and mines in the war against the Russians in the 1980s, and many Taliban fighters had benefited directly or indirectly from this experience. As for suicide bombing, it was a staple of Islamic extremism. It was predictable that our enemies would launch attacks on our patrols using high explosives delivered by a variety of means.

Pain may not be the best way to teach, but it is undeniably effective. Within months, contracts were rushed through for the purchase of small armoured vehicles called G-wagons. These were used with some success in Kabul.

Even before Canada shifted its deployment to Kandahar, however, the push was on to equip our forces with the LAV. The LAV is a wheeled vehicle. With even marginal roads or reasonably solid terrain, it can get around far better than a tank. Armed with a 25 mm cannon, it packs more than enough punch to defeat soldiers on foot. Its armour is thick enough to offer good protection against bullets and moderate protection against mines and other explosions. At three million dollars apiece, a LAV costs less than half what a tank costs.

With the end of the Cold War, it was unlikely that we would ever again have to face an enemy equipped with thousands of tanks, like the Soviet Union and its Warsaw Pact allies had been. The L AV was more suitable for the low-intensity conflicts in which we might become involved. We would become a lighter, more nimble force. After dominating the battlefield for a century, the tank seemed to be on its way out (in the Canadian Army, at least).

Task Force Afghanistan was equipped with L AVs by the summer of 2006. This is an important date because at the end of that summer, in September 20 06, we launched Operation Medusa, Canada’s largest combat operation since the end of the Korean War. Over several weeks the Canadian battle group fought its way into Zhari-Panjwayi.* Among other things, these Canadians established our first crude outposts in this area. These outposts evolved into the FOBs we have today.

The fighting during Op Medusa was unlike anything we have seen since. The Taliban had massed over a thousand fighters in a determined attempt to take, or at least to attack, Kandahar City. The city had been the capital of Afghanistan during their reign, and it still held a powerful attraction for them. It was the job of the Canadians to prevent this.

Canadians may recall that period, the late summer and early fall of 2006, because a dozen Canadians were killed—more than in the previous four years combined. What very few Canadians know is that Op Medusa was an overwhelming Canadian victory. Hundreds of Taliban were killed, and their access to Kandahar City was permanently denied. Apart from the infiltrators who have come singly or in pairs to plant bombs, there has been only one meaningful Taliban incursion into the city limits since then.* This was also the last time that large numbers of Taliban attempted to go toe to toe with a Canadian battle group.

The Taliban learned from their pain as well as we had. Since they could not defeat us in face-to-face encounters, they turned to IEDs. They were mirroring the actions of insurgents in Iraq, who had learned that vehicles like the L AV could be defeated with IEDs. Tanks, on the other hand, were almost impervious to these weapons.

As our losses from IEDs mounted, an urgent call went out for tanks to be deployed with our battle group. In an astounding tour de force, the Lord Strathcona’s Horse was able to deploy a squadron of tanks to Kandahar in only six weeks.

When the Canadian Leopards took to the field, they gave us a weapons platform that was invulnerable to anything the Taliban could throw at it. Wherever one of these beasts goes, it automatically creates a circle several kilometres in diameter within which any Taliban foolish enough to fire a weapon is very likely to die.

Another important feature of the tanks is their ability to smash through the mud brick walls that surround the compounds and line many of the roads and tracks in the area. Taliban ambushes are often launched from abandoned compounds or other areas where these walls can afford them some protection. This protection can be nullified by having a tank drive through the wall, a procedure called “breaching.”

Finally, the sound of a tank attacking with its main armament is an experience that defines “shock and awe.” This element is explained by Lieutenant Colonel David Grossman in his seminal book On Combat. * Grossman calls it the Bigger Bang Theory.

The equivalent of the Leopard in the American army is the Abrams. It has the same-size cannon and roughly the same dimensions. In his book, Grossman relates that battles fought in Iraq between insurgents armed with rifles and RPGs (much like the Taliban are here) lasted only a minute or two when Abrams tanks were involved. The insurgents would break contact and flee as soon as the tanks opened fire.

When the same insurgents went up against Stryker vehicles (the equivalent of our LAVs), the battles could last for hours, even though the 40 mm grenade launchers and .50 -calibre machine guns on the Stryker were as lethal against insurgents on foot as the 120 mm gun of the Abrams. It seems that the sound of the tank’s gun affected the insurgents on a primal level.

There are many similar occurrences throughout history. The first time muskets were used against men armed with crossbows is an excellent example. A man armed with a crossbow could fire a deadly projectile farther, more often and with greater accuracy than could a man armed with a musket. Nonetheless, the bowmen fled in disorder when confronted with the roar of these primitive firearms. The Leopard tank gives us a similar advantage over our enemies.

A successful mission, a happy crew

Captain Sandy Cooper’s tank is named “Stephanie,” after his wife. Clockwise from left, standing: Trooper Derek (“Never-Miss”) Tonn, gunner; top right: Master Corporal Darryl Hordyk, loader, tank second-in-command (a new master corporal, but he seamlessly starts directing the crew when Captain Cooper is busy talking to his commander on the radio); bottom right: Trooper Felix “I brake forIEDs” Lussier, driver; Captain Cooper.

Most importantly, this firepower, breaching capability and psychological impact can be delivered with minimal risk to our troops. Leopards lead the way down the roads of the combat area and they routinely hit IEDs, but virtually all of the damage is suffered by the vehicle rather than by the men inside.

Basing our Leopards at Ma’Sum Ghar places them in the centre of our area of operations, making them readily available anytime heavy firepower and strong protection are required. They go out on operations as often as the infantry, and yesterday they returned from a five-day jaunt through Nakhonay (Operation Constrictor IV), during which they kicked some serious ass.*

JULY 21 | Michelle and Mariam

I had finished eating dinner around 1715 and my thoughts were turning to the pleasant experience I would soon have of hearing the voices of my wife and daughter. Michelle is usually full of energy in the morning, eager to tell me her plans for the day.

Mariam probably woke up the same way. She had come from Kandahar City to visit her grandfather. He lives in Bazaar-e-Panjwayi, the village beside FOB Ma’Sum Ghar. Like Michelle, Mariam would have been excited at the dawning of a new day. A trip like this would have been quite an adventure for her.

Mariam would have spent the day exploring her new surroundings. Bazaar-e-Panjwayi is a lot poorer than Kandahar City, but children do not focus on things like that. I imagine Mariam’s attention was drawn more to the big mountains right beside the village. For a little girl from Kandahar City, this is “the country.” It may be poor, but it is full of new sights and sounds that fascinate the young mind. No doubt she also spent a good deal of time today snuggling up to her grandfather. He may have been a fierce Pashtun in his youth, but age has mellowed him. I have no trouble seeing him doting on his granddaughter. This gives the two girls something else in common: my parents adore Michelle and love her almost as much as I do.

When one looks for hope in a place as desperate as Afghanistan, it is almost a cliché to look at the children. Will they have the wisdom and the strength to do a better job than we have? Will they find a way to bring peace to this land? I hope Michelle becomes the kind of person who could contribute to this process. Mariam, tragically, will never get the chance to do so.

Around 1800 hours, one of our patrols was checking things in Bazaar-e-Panjwayi. These “presence patrols” show the enemy that we are keeping our eye on things and that there is no place we cannot go. The patrol entered the marketplace, where more people than usual were shopping and walking around.

This was neither a good thing nor a bad thing. The presence of many civilians does not guarantee that the Taliban will not detonate a mine or launch an ambush, as we have seen countless times in the past. Occasionally, the local population will get some warning of an impending Taliban attack. This makes it a very bad sign to see villagers scatter as we approach. This is called a “combat indicator,” and our troops go on high alert when that happens.

Whenever our troops are out and about, they maintain a security bubble into which no civilian can penetrate without showing due cause and harmless intent. After IEDs, suicide bombers are the most lethal weapon at the Taliban’s disposal. We want to make it difficult for them to get close enough to us to launch their attacks.

Taliban suicide bombers wear civilian clothing and are indistinguishable from the innocent. That is why Coalition forces have made strenuous attempts to educate the population. Signs on the roads and on our vehicles admonish civilians that they must never approach our patrols, checkpoints or convoys in a threatening manner. After eight years of war, a civilian would have to be mentally deficient not to be aware of this.

At approximately 1815, a man on a motorcycle drove towards the patrol. As he approached, the patrol made hand signals that clearly indicated the driver had to stop. The driver ignored these signals and kept driving, passing an Afghan police vehicle at the head of the patrol and getting even closer to the Canadians. This led to an “escalation of force”: the patrol aimed its weapons at the motorcyclist. That did the trick, and the driver stopped at a safe distance from the patrol. He was apprehended by the Afghan police and taken away. People who approach Coalition patrols are so likely to be motivated by nefarious intent that they are inevitably questioned and, almost as inevitably, released for lack of evidence.

The patrol had gone only a few metres farther when a second man approached, also on a motorcycle. He circled the patrol four times, just outside the security bubble. He stopped and turned his motorcycle directly towards the patrol and gunned the engine several times. Then he sped forward.

The two soldiers closest to the motorcyclist had already discussed what they would do if they had to go beyond hand signals. One of them carried a C9 light machine gun and the other carried our standard C7 rifle. The C7 is capable of firing a single, well-aimed shot, whereas a single pull of the trigger on the C9 sends several bullets into a rough general area. The soldiers had therefore agreed that any warning shots would be fired by the rifleman to minimize the risk to the civilians.

This time, the hand signals and the raised weapon that followed had no effect on the driver’s behaviour. The motorcyclist kept moving towards the patrol. The rifleman then fired a warning shot into the ground several metres in front of the motorcycle. The motorcyclist turned and fled.

The patrol formed into a perimeter, scanning 360 degrees for any further threats. Then it noticed a body lying on the ground. The soldiers rushed over to see if they could help, but there was nothing to be done.

The bullet had skipped off the ground and hit Mariam in the forehead. The back of her head had exploded, and most of her brain ended up on the ground beside her. She died in the blink of an eye.

“Junior” Cappelli Horth was the medic on the patrol. He bandaged Mariam’s head, picked up her skull and brain matter and put them in a plastic bag, loaded her into a vehicle and rushed back to the FOB. He did not attempt CPR. This was the perfect way to deal with this horrible situation. Junior had treated the patient with dignity and professionalism. Even across cultural divides, families can see that.

The “right thing” to do, however, depends on whether one is in Canada or in the developing world. Back home, I have run a number of resuscitations on children who I knew were long gone. By the time I go to tell their parents the bad news, I can show them all the things we did to try to save their child. Parents in the West accept that even if the doctor does everything right, the resuscitation attempt might fail. They have seen enough T V shows in which that happens that it has become part of their reality. Even when it is obvious their loved one is dead, Canadians are comforted when they believe the doctor “did everything that could be done.”

People in the developing world, on the other hand, are exposed to death much more often than we are. Between 10 and 20 per cent of their children die before age five, and elderly family members often die at home. Because of this, they accept that various diseases and injuries lead inevitably to death. Conversely, they often have an unrealistic view of what modern medicine can do. The things we achieve seem so miraculous to them that they can have trouble accepting the fact that our best efforts are sometimes not enough. The futile resuscitation attempt we undertake in Canada to ease parents into the grieving process is sometimes seen in the developing world as a failure that has at least an element of physician error involved. It is wiser to forgo any such attempt if the conclusion is preordained.

Tracer bullet ricocheting

(Photo courtesy Master Corporal Julien Ricard)

That was what I had in mind when Mariam arrived at the UMS. A quick exam determined that she had no pulse, was not breathing and had fixed and midrange pupils. I loosened her bandage and felt her skull. It felt like picking up a bag of marbles. Although there was only a tiny hole in her forehead, everything behind her face was shattered.

I turned to her grandfather and told him that I was terribly sorry, but there was nothing I could do. I told him I deeply regretted his loss, but it looked like he was past that. He seemed to have already accepted the death of his granddaughter. His questions had to do with the details of getting her body back to his home. Nonetheless, I asked the interpreter to explain to him that Mariam had not suffered. I say the same thing to bereaved families I deal with in Canada. It seems to help.

When Mariam and her grandfather had gone, I turned my attention to the Canadians. I told Junior that he had done an outstanding job. He seemed okay. I spent a long time after that talking to the shooter. He is a sensitive and sophisticated man. By the time we were done talking, I think he had settled into the healthiest and most appropriate emotional reaction to this incident. He was distraught, but he recognized that his actions had been correct under the circumstances. Had he failed to defend the patrol, he might have allowed a suicide bomber to get close enough to kill several of his comrades.

The second motorcyclist, the one who caused all this, was not caught by the Afghan police. He has to have been a Taliban sympathizer, if not an active fighter. He was testing the patrol to see at what range our soldiers would fire warning shots, in an attempt to analyze its defensive procedures. In doing so, he deliberately provoked the patrol into shooting when there were numerous civilians around. He recklessly endangered those civilians and caused Mariam’s death. I doubt he feels as bad about that as the shooter does.

It is now a little after 2100. I am going to call home and talk to Michelle. I will ask her what she is doing, and we will laugh together for a few minutes. Then I will try to fall asleep while thinking about her face and not the one I saw tonight.

Addendum, July 31: The press reports in Canada have been reasonable about this incident, with the exception of one news outlet in Montreal that implied we had fired several rounds at civilians without explaining the threat our troops had faced. There has been a thorough investigation, which I will write more about in a later entry. It goes without saying that the family will be compensated.

Our procedures have been reviewed, and all troops have been ordered to fire warning shots into the air from now on. This is not as effective as firing into the ground. A shot into the air generates only a loud noise, whereas a shot into the ground also produces the visual stimulus of the dust kicking up where the bullet strikes. Firing into the ground is a much more powerful deterrent. It is also awkward and time-consuming to move to a “shoot to kill” position after having fired into the air. Nonetheless, we will use this method to increase the population’s safety.

Now, some context. The UN has issued a report on civilian casualties in Afghanistan over the first six months of 2009. There have been more than a thousand such deaths, over 70 per cent of them caused by the Taliban. These numbers are the opposite of what insurgencies should produce. Look at the civilian casualty rates in Sudan, El Salvador, Rhodesia and many others. Poorly armed rebel forces try to earn the trust and co-operation of the civilian population and cause few casualties among them. Entrenched powers use heavy weapons in sometimes indiscriminate ways and cause a lot of civilian casualties. Here, the proportions are completely inverted.

The report also accuses the Taliban of taking advantage of Pashtun culture, specifically nanawati (see the June 9 entry), to coerce civilians into giving them shelter and then attacking Coalition forces from those same dwellings. According to the report, this sometimes tricks Coalition forces into attacking the area and causing civilian casualties. This is something we are trying very hard to avoid.

Addendum, August 1: This is rich! Within twenty-four hours of the UN report coming out, the Taliban issued a statement saying they would “stop using suicide bombers to avoid harming Afghan civilians.” Eight years of war and thousands of civilian deaths later.

JULY 22 | Rules of Evidence, Rules of War

We had only one war casualty today, a fifteen-year-old who took a bullet to the shoulder. His injuries were not life-threatening, the care was straightforward and the medevac helicopter came quickly. I met his father at the gate after the helicopter had left and assured him his son would be returned to him shortly and in good health.

The most important aspect of the case had nothing to do with the medicine. The boy had been brought in after FOB Zettlemeyer, an ANP outpost a kilometre north of here, had been attacked. He told us he had been catching small crabs in the Arghandab River when he was shot. The problem with his story is that he was discovered north of the outpost whereas the river is to the south, between the FOB and the outpost. For his story to be true, he would have had to have walked close to one kilometre through the bush with his gunshot shoulder. This is very difficult to believe, as this would have meant he had walked away from the FOB, to which he claimed to have requested to come when he was found by the ANP.

Although still a juvenile, the patient fell into the category we call FA M, a fighting-age male (the Taliban make extensive use of child soldiers). We all had a gut feeling that this guy was wrong somehow. That is not enough. He was sent to Kandahar without any restrictions on his future movements. He was not even questioned by our military intelligence people.

We have had people about whom our suspicions of Taliban affiliation were much stronger but who were also released for lack of sufficient evidence. Some soldiers are frustrated when that happens, because it is likely that these individuals will go right back to their Taliban units and be attacking us the next day. Whenever I sense that this might be the case, I tell the aggravated soldier that the ones we let go are living proof that, despite the savagery of our enemies, we continue to fight this war in a clean and honourable way.

I say the same thing when a soldier expresses frustration with our rules of engagement, the criteria we must satisfy before we open fire. The rules are different for different weapons, with the most restrictive criteria being reserved for the heaviest weapons, the ones most at risk of killing innocent bystanders. The combat troopers who are getting shot at from one family compound sometimes resent it when a commander, safe at KAF, denies them an air strike because it might damage a neighbouring compound. It speaks volumes about the discipline and professionalism of these men that they follow these rules.

JULY 23 | Investigations

I spent a good deal of time yesterday describing the circumstances of Mariam’s death with a representative of the CF National Investigation Service (NIS). Any incident of this severity is investigated by NIS. Its members are senior members of the military police and serve as the detectives of that branch.

It is common for emergency physicians to have to discuss cases with police and lawyers, both in and out of court. I have had to do so several times and no longer feel any anxiety during the process. Although I had never met an NIS man before, much less been interviewed by one, this did not feel any different. Once the tape recorder was turned on, I gave my statement in one long speech. The investigator asked a few more questions and we were done. I had to go through the same process again today because of an incident that occurred this morning.

An Afghan policeman had been standing near the front gate of the FOB when one of our armoured vehicles came in. The Canadians indicated their intention to come in and turn to the left. However, it seems that the policeman did not know that tracked vehicles do not turn in the same way a wheeled vehicle does. To turn a tracked vehicle, you make one track go forward while the other one goes backward. As a result, the vehicle pivots, more or less in the same place. Unfortunately, the policeman did not wait for the vehicle to pass but rather walked right into its blind spot, whereupon his head was crushed between the vehicle and a wall. He was rushed to the UMS.

When he arrived, his head was covered with a sheet and he was not moving. One of the policemen accompanying him, perhaps a family relation or close friend, was distraught and screaming. He was controlled by the camp sergeant-major and removed from the premises.

I took half a second to steel myself before removing the sheet. Given the mechanism of injury and the other man’s emotional state, I thought I was going to be looking at a skull that had been squashed like a grape. Somewhat to my surprise and very much to my relief, the patient started talking as soon as I exposed his head. He had multiple facial lacerations and a skull fracture of the right forehead. His right eye socket had caved in and his eye was “extruded”—it went much further forward than it should have. The optic nerve, the thing that connects the eyeball to the brain, had been stretched a considerable distance. His pupil did not react at all when a light was shined into it.

This case gave me a chance to do some on-the-spot teaching. Everyone in the UMS, medics included, was focusing on the facial wounds. These are very distracting for medical personnel because the face is such a big part of who we are as human beings. You can lose a hand or a leg and, once your prosthesis is in place, people will barely notice the difference. A mangled face, however, dramatically changes how people see you.

I therefore took a minute to show my crew that, as bad as these injuries were, none of them was life-threatening. The patient was breathing on his own, he had good air entry into both lungs and his vital signs were stable. You could see that he was protecting his airway because he was spitting up the blood that pooled in his mouth. He also appeared neurologically intact because he was moving all four limbs and was able to speak coherently. He needed maxillofacial and plastic surgery procedures, but these could be safely delayed for hours.

I like to say that these patients are “stable in their instability.” So long as nothing else goes wrong, they are likely to remain stable for quite some time. It would be a terrible mistake, however, to assume that will be the case when a helicopter transfer is imminent. We therefore proceeded with a standard emergency department intubation, giving additional drugs to protect the brain as well as the usual ones to put the patient to sleep and paralyze him. We protected his cervical spine while we did this—always a good habit when the patient has a head trauma. We had barely finished securing the tube when the helicopter arrived to take him to KAF.

No more than an hour had gone by when another helicopter arrived at the FOB. This one carried a different member of the NIS, sent to investigate today’s incident.

I have a number of friends who are senior police officers, and the two NIS men came across the same way my buddies do: professional, very good at their jobs, completely ethical and determined to get to the truth. Both of them are investigating incidents in which the actions of Canadians have injured Afghans. Having spoken to the men involved, I am convinced that both occurrences were tragic accidents. I am equally convinced that the investigators will only reach that conclusion themselves when they have examined all the evidence and interviewed all the witnesses. And re-interviewed them, if necessary: the NIS man in charge of the investigation into Mariam’s death called me back to confirm which side of the forehead the bullet had entered, because there was disagreement among the witnesses. This may seem trivial, but it shows how badly this guy wanted to get the story absolutely right.

JULY 24 | A Righteous Shoot?

Emergency physicians like cops. We see each other a lot in the course of our duties and we have a lot in common. Both our jobs involve some drudgery leavened by regular moments of drama. We both see people when they are at their weakest, angriest and/or most distraught. We both do shift work, that notorious killer of relationships. A lot of emergency nurses end up married to cops.

I like cops more than most people do. For the past five years, I have acted as the medical adviser for the “tactical unit” (a.k.a. SWAT team) of our police department. This relationship proved to be very useful when I re-enrolled in the CF two years ago. By the time I got back in uniform, I had already reacquired many of the infantry reflexes of my youth, thanks to the training I had done with my “tac” buddies.

Emergency physicians and policemen have something else in common: people lie to us regularly, for any number of reasons. For policemen, it only goes one way: people try to hide what they have done or what they know. For emergency physicians, the untruths cover a wider spectrum. Some people exaggerate their symptoms in the hopes of obtaining a particular treatment, commonly narcotics. Others minimize their symptoms, because they are afraid of what the diagnosis might be. Some people go either way, depending on what psychopathology is dominant in their family that particular day. And some people are just nuts.

Having to sort through all these emotions and agendas every time we are on shift gives us an ability, like cops, to “read” people. While I think I do this reasonably well, the skill is situational. It is essential to consider the patient’s social and cultural milieu before drawing any conclusions. Nonetheless, my travels have taught me that there are some universal human behaviours. I may have stumbled on one more.

One of today’s patients was Abdul Rahzak, a man in his forties. He had been shot three times by the ANP. One bullet went through his right ankle, shattering the tibia and leaving his foot hanging limply. One bullet went through his right hand, breaking several bones in his palm and wrist. The last bullet could have been the widow maker, but Allah was watching over Mr. Rahzak. The slug entered below his right armpit and exited halfway up his right shoulder blade, passing outside his chest cavity. Though he was in severe pain Mr. Rahzak was breathing normally, and ultrasound confirmed there was no blood or air leaking into his chest.

The medical management was almost mundane: bandage all the wounds, splint the broken bones, give pain medicine and antibiotics, wait for the chopper. Managing the circumstances in which Mr. Rahzak was wounded proved to be far more ambiguous.

For a guy who had been shot by the police, a couple of details did not add up. After dropping Mr. Rahzak off at the UMS, none of the Afghan policemen stayed behind. Somehow, an individual on whom they had used potentially lethal force half an hour ago was not even worth questioning, much less arresting.

Mr. Rahzak’s behaviour in the UMS was equally unusual. The patients I have treated whom we either knew or suspected to be Taliban have all had one thing in common: they have all been afraid of me well into the patient encounter. They think we are going to torture them, because that is what the Taliban do to their prisoners. It takes a long time to convince these patients that I will treat them properly.

Mr. Rahzak behaved very differently. As soon as I identified myself in Pashto as a physician, he began to relax. When I had determined that no life-threatening injuries were present, I told him: “Tah bah shah kaygee” (“You’re going to be all right”). Although I had not given him any pain medication, I could tell that the patient-doctor connection had been made. Mr. Rahzak looked at me with that mixture of awe and gratitude that is the emergency physician’s reward when patients are convinced they will be well looked after. That struck me as un-Talibanlike.

While we were waiting for a helicopter I shared this observation with the camp’s sergeant-major, Master Warrant Officer Richard Stacey of the “Strats.” He is the senior non-commissioned officer on the base and a man of infinite wisdom. He was sure he had seen the patient a number of times on patrols around the FOB, and he agreed that Mr. Rahzak did not seem “wrong.”

I was still wondering why Mr. Rahzak had been shot when I was called to a meeting a few hours later. Attending the meeting were Mr. Rahzak’s brother, three local elders (two of them “Hajis” and the other a pharmacist) and two representatives of the police training team.

The meeting began with my report about the patient’s injuries. I reassured his brother that the patient’s life was not in danger, but I emphasized that the long-term function of both his right foot and right hand could be affected. Mr. Rahzak’s brother asked if he could go to Kandahar to visit him, and we will try to arrange this tomorrow.

The elders spoke next. The nagging suspicion I’d had that this had not been a “righteous shoot” became much stronger. All three of the elders were emphatic: Mr. Rahzak was in no way associated with the Taliban. He was a farmer, and he had been tending his crops when he was shot. According to the elders, the police had opened fire without any provocation whatsoever.