AUGUST 22 | Ramadan

This is the first day of Ramadan, the holiest month in the Muslim lunar calendar. Over the next twenty-nine or thirty days, depending on the behaviour of the moon, Muslims must refrain from eating, drinking, sex, smoking or “anything that is in excess or ill-natured” from dawn till dusk. The fasting in particular is meant to give Muslims a chance to cleanse themselves, to appreciate what they have and to recognize that others may have less. The two most important themes seem to be connecting with family and caring for the poor.

During this month Muslims get up before dawn to eat. Even though they gorge themselves then, the grumpiness level starts to rise around midafternoon. This is alleviated by another large meal after sundown. Between lack of sleep, post-meal torpor and late-afternoon grumpiness, there are only a couple of hours each day when everyone is firing on all cylinders.

Some Muslims take their fasting so seriously that they carry around a little cup into which they spit their saliva. This prompts the obvious question: if the Taliban see themselves as good Muslims, will they take this month off to fast? Or will they accept a decrease in their operational effectiveness as their soldiers go around hungry and tired during the afternoons, when most of the fighting takes place?

The answer is no. The Taliban have given their troops a pass on this one, just as they have played fast and loose with most other parts of the Quran as well. That has been the case in years past. Summer is traditionally the “fighting season” in Afghanistan and there has been no decrease in combat activity during Ramadan for the past three years. The most intense fighting Canadians ever experienced in Zhari-Panjwayi occurred when they arrived here in 2006. The Taliban massed their troops to try to prevent Canadian troops from entering these districts. The fighting continued for several weeks, well past the date Ramadan began that year. If things remain as quiet as they have for the past two days, it will be because the Taliban shot their bolt on election day.

Ramadan ends on the first day of the next new moon. This is the holiday of Eid ul-Fitr, “The Festival of the Breaking of the Fast,” a daylong party during which there is supposed to be a lot of eating, praying and donating to the poor. Human nature being what it is, I am willing to bet that the order I listed for those items is the order in which they are given priority.

I dropped in on the ANA officers late this afternoon, happy to see that they were none the worse for wear for their twelve foodless hours. They invited me to join them for dinner, and I readily agreed. They told me to drop by at 1900, which is the same time that they had told me to arrive every other time I had had dinner with them. On each occasion, dinner had started at 1930 or a little later. This is no different from what goes on elsewhere in developing world environments, and I have no trouble with it. Either I wait and chat with the officers until dinner starts, or I factor this in and arrive late myself.

On this day, I knew they could not start eating until after sunset, so I waited until about ten minutes after dark to wander over. As I was walking towards their barracks, it dawned on me that I was displaying, if not cultural, then at least culinary, insensitivity. This was confirmed when I arrived.

After fasting for twelve hours, no one had been in the mood to wait a minute longer for dinner. They have made sure that everything was ready to go the second the sun dipped below the horizon. By the time I got there, everyone had finished eating. This didn’t stop them from welcoming me warmly and sitting me down to a large dish of some kind of vegetable I’ve never eaten before, supplemented by the usual huge piece of naan.

AUGUST 23 | The Warrior Princes

When I described the role of Major Tim Arsenault, the combat team commander at FOB Wilson, I spoke mostly in terms of his responsibilities. Let’s look at the other side of that coin and consider the power of Major Steve Jourdain, the combat team commander here. I compared Major Jourdain earlier to the warrior kings of antiquity. This is not an exaggeration.

Just as Major Arsenault’s responsibilities dwarf anything encountered in the civilian world, the destructive force Major Jourdain has at his disposal is almost beyond comprehension for someone outside the military.

There are very few officers the CF trusts this much. There is no one looking over Major Jourdain’s shoulder here, and his word is law. We have to be sure that he will never abuse his position. If that were to happen, the damage he could inflict on innocent Afghan civilians, on our mission’s goals and even on his own troops would be incalculable. In Major Jourdain’s case, the trust is entirely merited.

So how does Major Jourdain exercise a good portion of his power? The combat team contains a large number of “supporting arms.” I have already introduced several of these groups, including the engineers, tankers, artillerymen and reconnaissance soldiers. But no matter how many members of the supporting arms might be in a combat team, by far the largest group of soldiers belongs to the “arm” that is being supported: the infantry. Since more than one hundred men are in the company based at the FOB, Major Jourdain could not possibly control them all on the battlefield. Rather, he guides the three men who are most responsible for turning his orders into reality.

These are the platoon commanders, each one of whom is in charge of thirty to forty soldiers, divided into three infantry sections with ten soldiers each and a fourth “headquarters/heavy weapons” section. This last section contains the platoon commander, platoon second-in-command and other specialized soldiers such as radio operators and the soldiers who man the rocket launchers.

I admit that I have a fondness for the platoon commanders. When I graduated from the Infantry School of the Combat Training Centre in 1979, this is the job I did for the next three years. I learned a great deal about leadership as a platoon commander, and this was one of the key formative experiences of my life.

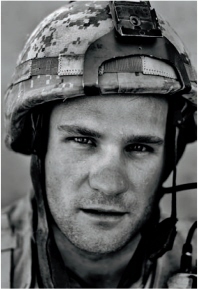

I was a competent platoon commander: my platoon was regularly chosen to take on the more challenging assignments, and I had good success in field exercises. But after observing the three platoon commanders of Combat Team Cobra for a few weeks, I can see that I was not in the same league as they are. The war has made them develop as commanders, but they had to have been quite sharp to begin with. I sat down with each of these extraordinary young men separately to conduct the only formal interviews I did for this book.

Captain Vincent “Vince” Lussier, like me a Franco-Ontarian, is the oldest of the three. He shares many of my beliefs about the value of the mission and has a sophisticated understanding of who we are fighting and why. During our interview, he astounded me by describing the effect of Taliban rule on infant mortality— the single best measure of a population’s health. This is something very few non-medical people would do.

Major Steve Jourdain, the warrior king

Captain Vincent “Vince” Lussier, commander, First Platoon

Almost twenty-seven years old, he has been a platoon commander for three years. All that time has been spent with the same platoon. Many of the men he has taken to war were wet-behind-the-ears seventeen-year-old recruits when they joined him. He has watched them grow up not only as soldiers but also as individuals.

The affection he feels for his men is intense. He expresses this in familial terms: “I feel more like their older brother than their commander.” It is a cliché to refer to an infantry platoon as a “band of brothers,” but it is very apt.

Even stronger than this affection is Captain Lussier’s pride in his platoon’s troopers. This pride has not blinded him to their failings. On the contrary, Captain Lussier spontaneously volunteers that “the other platoons have men who are better shooters, better patrollers or better tacticians than mine.” But he insists that his men have the most heart: “We may not be the best soldiers, but we are definitely the best team.”

Captain Lussier told me that he moulded this team in the best but also the most tiring way possible. He was present for all their training exercises, even the physical training that he was not required to attend. During this time, he was able to assess how well various individuals worked together. If they are the best team today, it is because Captain Lussier specifically chose them for that role.

This devotion to his men has been returned to Captain Lussier in powerful ways, at both the platoon and the personal levels. As a platoon, his men accept the tasks they are assigned, no matter how dangerous or onerous. As individuals, several of them have already saved his life. He describes a poignant example of a trooper whose soldier-skills were marginal when in training back in Canada but who had guts and drive. So Captain Lussier brought him along. On one mission, the trooper placed himself with a mine detector in a position of maximum danger and discovered an IED on a path Captain Lussier was about to take. “If he had not been there that day, I’d probably be dead,” Captain Lussier says. There are many similar stories in his platoon, connecting each man to several others. It is those connections that Vince tells me are what he will treasure most about his experiences here.

Lieutenant Alex Bolduc-Leblanc, twenty-four years old, was encouraged to join the army by his uncles, both of whom were infantry officers. He graduated from the Royal Military College in 2007 and joined his battalion in September that year. He was assigned to a platoon and, a few months later, began work-up training to go to Afghanistan.

Lieutenant Bolduc-Leblanc’s motivation for coming to Afghanistan mirrors my own: he sees this conflict as a war of good against evil. His upbringing gave him a strong moral code and, in a way, he looked forward to being able to do his part here. His view on the strategy we must pursue to achieve victory is also similar to mine: protecting the population until they are educated and trained enough to defend themselves militarily against the Taliban and to reject their extremist ideology.

Lieutenant Bolduc-Leblanc had all the normal anxieties one would expect prior to deployment: “Would I be able to function under fire? Would I be frightened?” But if anyone was born to be a warrior, it is this guy. “Being in combat is a rush!” he says, with a bit more enthusiasm than most civilians would find proper. But he is only being honest. Combat hyperstimulated all his senses and he “felt more alive than ever before.”

He has not killed anyone yet, but his men have. “Even though this is a war, that was hard on them,” he told me. “I had to counsel a number of them afterwards.” It is reassuring to me that Canadian soldiers do not take killing lightly. And it is comforting to know that, when they have to take a human life, Lieutenant Bolduc-Leblanc is there to help them come to terms with what they have done.

Lieutenant Alex Bolduc-Leblanc, commander, Second Platoon

( © Louie Palu/ZUMA Press, reprinted with permission)

Lieutenant Bolduc-Leblanc admitted that he has been “scared, really scared” three times since arriving in the Panjwayi. Those were the occasions when vehicles containing some of his men hit an IED. Each time, the vehicle disappeared in a cloud of dust. “Each time, it took a full minute for the crew commander of the vehicle to get on the radio to tell me that everyone was all right.” The way Lieutenant Bolduc-Leblanc described his emotions during those three one-minute eternities was so vivid that the intensity of the anxiety he felt was physically palpable to me as a listener.

In some ways, Lieutenant Bolduc-Leblanc is still a very young man. This is his first time in the developing world, and he admits he was shocked at the backwardness of the people around the FOB. “It’s ‘Jesus time’ out there,” he says with disbelief. The absence of any modern amenities (cars, electricity, running water, health clinics, etc.) is something he had not believed existed.

He also cannot understand the persistence of the Taliban. After a battle in which his platoon killed several of them, he overheard the Taliban leader congratulating his group on their radios because they had been able to inflict a minor wound on a single Canadian. “I don’t get it! Why don’t they care about their men the same way I care about mine?” he asks.

In other ways, Lieutenant Bolduc-Leblanc displays more maturity and professionalism than someone twice his age. He routinely goes out on patrols in which he engages the local population in conversation. Often he holds shuras with the local elders. During his time here, he estimates that he has spoken and shaken hands with at least a few dozen Taliban. “These guys will shoot at me, then hide their weapons and share a cup of tea with me.” I asked if he found this intensely frustrating. The same situation has led many soldiers in many armies to abuse and even murder civilians, often with far less suspicion than Lieutenant Bolduc-Leblanc has had. But he describes these events as barely annoying.

“My rules of engagement are clear. We cannot open fire unless directly threatened, and we cannot arrest a civilian without clear evidence of wrongdoing. Until one of those conditions is met, I will extend my hand in friendship to anyone and everyone I meet here.”

That is counterinsurgency at its best.

Twenty-five-year-old Lieutenant Josh Makuch could be a poster boy for the benefits of multiculturalism. Although he is nominally an anglophone Ontarian, I lost track of the number of ethnic groups represented in his DNA. These have given him a broad and sophisticated world view as well as almost flawless French.

When unilingual anglophone infantry officers graduate from the Combat Training Centre, they must choose to serve in one of two anglophone regiments. For Lieutenant Makuch, this would have meant being posted to Shilo, Manitoba, or Gagetown, New Brunswick. His French-language skills gave him a third option: by joining the Van Doos, he could be posted to Quebec City and stay close to Montreal, where he had done his undergraduate degree.

Shilo, Gagetown or close to Montreal? It was an easy choice to make. Lieutenant Makuch arrived in Quebec and joined the combat team in August of 2008. There were only nine months left before deployment, and he had to work hard to integrate himself into the platoon’s leadership team and to be accepted by the men. By the time they went to war together, he had achieved that.

He describes his time here as being “seven months spent at Maslow’s fifth level.” For those of you unfamiliar with Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, the fifth level is “self-actualization,” in which one is achieving one’s full potential as a human being. It is a profoundly rewarding experience to be at this level, but it is something few people ever attain.

Lieutenant Makuch’s self-actualization has come as a result of the heavy responsibility he has been given at such a young age. “I matured more in the first five months of this tour than in the previous five years,” he states. “I have to stand in front of forty men and explain to them what we are going to do and how we are going to do it. And we all know that our lives depend on my plan being sound.”

Hearing him express these feelings, I was reminded of the way young doctors will describe their first night on-call by themselves. The sacred trust, the awesome responsibility and the feeling of being extraordinarily privileged to be in this position are similar, but much more intense for infantry officers. And like a young doctor, Lieutenant Makuch has learned that even the best decisions sometimes lead to the worst possible outcome—Master Corporal Charles-Philippe

Lieutenant Josh Makuch, commander, Third Platoon

“Chuck” Michaud was one of his men.

Of the three, Lieutenant Makuch is the one who was interested in going to war for “the experience,” and he sees the mission in more abstract philosophical terms than I do. “I agree with our goals here and they may well be worth my life. But I am not ready to die for the cause. This is not because I am scared of dying. I am just so curious about what the rest of this life has in store for me.”

Lieutenant Makuch is unsure about his future. Being chosen for this job marks him as an up-and-comer in the CF, but he has yet to decide whether or not he will stick it out for twenty years. “I have already

Lieutenant Josh Makuch, commander, Third Platoon had the best job the army could ever give me: commanding a platoon in combat. No matter what happens next, I will never be called to do this task again.”

A few years from now, you might bump into the young man pictured here. He might have somewhat longer hair and be living a bohemian lifestyle as he decides what he is going to do next. If you recognize him, take the time to talk to him and listen closely to what he has to say.

He was a warrior prince once; he led Canadians in battle. You could learn a lot from him.

Addendum, August 25—A close call: I have not spoken much about the other medical types at this FOB because my contact with them has been limited. There has been no medic assigned to the UMS for weeks. A Bison ambulance crew was here when I arrived, but they left after four days. Another Bison dropped by for a few days, then they were reassigned as well. One of the four combat team medics left on leave right after I got here, and another one left a week ago on a two-weeklong mission. The gang here is just as impressive as their colleagues, as this brief entry will demonstrate.

At 2100, one of our patrols left to set up an ambush in an area where we suspected the Taliban might be transiting. Things were going well till around midnight when a trooper came to tell me that a member of the patrol had fallen into a well. My heart stopped. On June 7, 2008, Captain Jonathan Snyder had been participating in a nighttime combat patrol. Somewhere in Zhari district he fell into a kariz, a kind of open-pit well used by Afghan farmers. Weighed down by nearly a hundred pounds of gear, Captain Snyder drowned. I had the sick feeling that in this case the result would be the same.

Things ended differently this time. One of the reasons for this was the rapid reaction of Master Seaman Charles Cloutier, the senior medic of the combat team. Although he was some distance away from the well when our soldier fell into it, MS Cloutier immediately recognized what had occurred and started shoving people out of the way to get closer to the victim. When he got to the side of the well, he quickly organized the other members of the patrol. They fished out a somewhat banged-up, but very much alive, Lieutenant Josh Makuch. MS Cloutier checked the lieutenant and, detecting no major injuries or bleeding, organized the evacuation back to the FOB.

Master Seaman Charles Cloutier, senior combat medic (after lifeguard duty)

Corporal Alex Cloutier-Dupont, combat medic

Once they arrived at the UMS, MS Cloutier and I carried out a thorough assessment of his patient. After an hour of observation, we discharged the lieutenant in good condition. Later, when MS Cloutier described his terrible anxiety as he ran towards the well, I could see that he felt as strongly about any wounded Canadian as platoon commanders feel about their men.

Anytime Canadian soldiers go down, for any reason, they can be sure that Master Seaman Cloutier will come for them. Or die trying. That is his commitment to them. He is their “doc.”

The only other member of the Sperwan Ghar medical crew here now is Corporal Alex Cloutier-Dupont. I could go on about him at length, but it would sound boringly similar to what I have written about the other combat medics: he is very good at his job, in excellent physical condition, always good humoured and keen to help out wherever and whenever he can. I will therefore limit myself to a single observation. Take a close look at the following photograph of him. Does anything seem unusual?

Military readers may notice that Corporal Cloutier-Dupont is not wearing the standard Canadian Army tactical vest. Instead, he is wearing a modular vest that is far more functional for a combat medic than the one the army issues.

As with the special medic pack, which he has also bought, this piece of equipment cost him six hundred dollars. A week’s pay, so that he can do his job better. Do his government job better.

AUGUST 24 | The Internal Contradiction of the Taliban

A quiet day. This gives me a chance to write about something which happened a few weeks ago.

It was my last day at FOB Ma’Sum Ghar. The combat team based there had been out on a mission for a few days. They had been in a heavy firefight on the second-last day of the operation, not far from the FOB.

On their way back to Ma’Sum Ghar, they were flagged down by a wounded Afghan. He was lying beside the road, propped up against a rock. He stated he had been a bystander during the fighting the day before and had been hit during the exchange of fire. He had a number of bullet wounds, some of them large and gaping. None of them were bleeding, and all appeared to be several hours old.

Master Corporal Turcotte’s ambulance crew picked him up and treated him. As they packed and dressed his wounds, they noticed something bizarre: the wounds appeared to have been cleaned and . . . he had an IV catheter in place on one of his arms. What the hell? He had received medical care of some kind after being wounded. So what was he doing on the side of the road?

When the Canadian medics began to question him about this, he fell silent. That made everybody suspicious. These suspicions were confirmed when we checked his skin for gunpowder residue: the test was strongly positive. He was evacuated to the KAF hospital in good condition . . . but with a military police escort.

As mentioned earlier, we treat Taliban prisoners the same as anyone else, and I make sure these prisoners know that it was the Canadians who took good care of them. It seems that our enemies have finally understood this. Although I have heard of similar incidents before, this is the first time I have had direct knowledge of a wounded Taliban being deliberately placed in the path of our troops so that we will pick him up and treat him. I’ve discussed this with other senior officers, and apparently this is not a rare occurrence.

You cannot help but wonder what effect this will have on the ordinary Taliban trooper. He is told that we are infidels who should be tortured to death if we are captured. Then he is told to leave his wounded comrade-in-arms in the path of one of our convoys because he will be well treated. At some point, the contradiction of those two statements has to make all but the most fanatical ideologue question the legitimacy of the first declaration.

AUGUST 25 | The Observer Observed

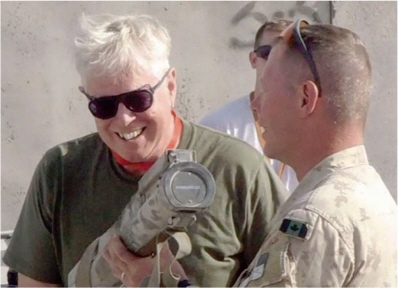

After three months of observing everything around me, I have spent the last forty-eight hours being observed myself. A Canadian journalist has joined us on the FOB and has spent a fair bit of time with me. He has interviewed me about the upcoming release of FOB Doc, and we have had a number of informal conversations.

This being his fourth visit to Afghanistan, he has learned a lot about the country. He is familiar with the geography, understands the politics and knows something about half of the presidential candidates (forty-one people—some of them women—ran for the position in last week’s elections). As he is the first “journo” I have spent any time with, I thought I would read his articles and write an entry explaining whether I agreed with him or not. But something happened this evening that is more newsworthy.

I have been spending a fair bit of time with the Afghan soldiers. I regretted not having done this previously and was determined to make up for it before I left. While I feel that my readings have given me a clear sense of Afghanistan as a country, I was hungry for more personal contact with its people.

This is not a common thing for Canadian soldiers to want to do. By and large, they prefer to keep to their own when not on operations with the ANA. The Afghan soldiers are not shy about making remarks about this. The frequency of my visits is something they seem to appreciate.

The journalist became aware of the relationship I had with the Afghan officers and asked if he could come along the next time I had dinner with them. I was happy to arrange that, and got the best interpreter on the camp to facilitate our discussions.

A few minutes before the evening prayer call (which defines the end of the day’s fast during the month of Ramadan) I went to collect the journalist. As we walked over to the ANA barracks, I commented on the tastiness of the meal we were about to receive. What he said next stunned me: he had no intention of eating anything because he was afraid the Afghan food would make him sick.

I should have stopped right there and flatly refused to bring him to dinner with people I consider my friends. I did not, and the result was predictable. The Afghans sat us down on the thickest cushions, served us first and provided us with a series of courses. My countryman rejected everything that was offered to him, with the exception of a few bites of bread. He gave the excuse of having a “bad belly,” which fooled no one. The Afghans commented that “only the Doc likes our food.” The protestations of the journalist to the contrary were unconvincing.

This refusal to participate in a social event he was there to document did not stop him from taking numerous pictures and writing an article about his meeting. I was left with the feeling that I had facilitated something that was at least mildly exploitive.

AUGUST 26 | The Bomb

At least forty-one dead. A number that is sure to rise because many of the wounded, who currently number sixty-six, are critical.

The Taliban set off a massive bomb last night in Kandahar City. They packed five cars full of explosives and detonated them. A city block was wrecked, and more than forty shops were destroyed, many of them the only source of a family’s livelihood.

The story on the CBC website about this event gives us the total of Coalition deaths for the year to date. The story emphasizes that this is the most in a single year since the beginning of the war. It does not explain that this is due to the massive influx of American soldiers into Afghanistan and that, with these additional troops, we are challenging the Taliban far more than we used to. As in all these stories, the total number of civilians killed by the Taliban this year is not mentioned. The fact that most of the people the Taliban kill are civilians is also omitted.*

Data without context, again.

Addendum, August 27—Inside the Blast Radius: The second Bison ambulance crew to spend time with me at this FOB had been quickly reassigned to Kandahar City for the election. They were to be the medical element of an additional QRF (quick reaction force) located at Camp Nathan Smith (CNS). This is a base on the outskirts of Kan-dahar, separate from KAF. CNS is the home of the Provincial Reconstruction Team. Units located here have rapid access to the eastern half of Kandahar City.

The medic of that Bison is Corporal Marie Gionet, a remarkable thirty-one-year-old woman who earned an anthropology degree before joining the CF Health Services five years ago. She was attracted by Egyptology but realized that not many people can earn their livelihood doing this. She describes joining the CF as a wise career move. In Afghanistan, you could argue that she has the best of both worlds: a secure career in the military and a job where an attractive lady still gets to wear shapeless clothing, live cheek-by-jowl with a bunch of smelly guys and work in a hot, sandy environment.

On the evening of August 25, Corporal Gionet heard a blast so loud that she thought it had taken place right outside the camp walls. She rushed to get her gear on and she reported to the sergeant in command of the QRF. He told her to stand by until they had a clearer idea of what was going on. She went back to her Bison and got ready to head out.

The order to deploy into Kandahar City came thirty minutes later. Corporal Gionet was shocked to learn that they would be going to a blast site over four kilometres away. This was her first inkling of how massive the bomb had been. Basing the ambulance at CNS proved to be a prescient move: this supplementary QRF was the first Coalition force to arrive at the scene of the blast.

Corporal Marie Gionet, Bison medic

When the QRF arrived, Corporal Gionet was faced with a scene of unbelievable destruction. An area the size of three football fields had been blasted and blackened. Many fires were burning, the air was thick with smoke and it was getting dark.

Contrary to what the media had first reported, a single vehicle was involved in the attack—a tanker truck filled with explosives. It had more destructive power than anything we drop from our planes. The priority was to secure the scene and light it. The QRF vehicles formed a circle around the blast area, guns pointing out and headlights pointing in.

Corporal Gionet relates that two events marked her strongly during this incident. The first occurred once the perimeter had been secured and she rushed out of her ambulance to render aid to the wounded.

There weren’t any.

Further information confirms that there were forty-one dead after the blast, but that the total number of wounded was seventy-six, not sixty-six as written above. Six of wounded died, bringing the total deaths to forty-seven. But not one of these seventy-six people was still on the scene when Corporal Gionet arrived. The Afghan civilian medical personnel had, in her words, done a spectacular job. They had secured the scene—ensuring that no secondary explosions (whether intentional or accidental) or any other hazard threatened the rescuers—triaged the patients effectively and organized an efficient entry-exit system for the many ambulances to come in, pick up a patient and depart. The job of saving lives had been done as well as it could have been done. By the Afghans themselves. Without anybody’s help.

This had quite an impact on Corporal Gionet. As a medical professional, she grasped the sophistication required to accomplish what the Afghans had done. “This was the first time I have seen a non-military branch of the Afghan government functioning at a high level without any outside assistance,” she told me. “I had been unsure about the mission’s chances of success until I saw that, but I’m more optimistic now.”

This reminded me of how distorted our perception of Afghanistan can become because we spend all our time fighting the Taliban in Zhari-Panjwayi. Not too far from here is a city of a half-million people that works reasonably well, by developing world standards.

These people dealt quickly and efficiently with the biggest mass casualty event Afghanistan has seen in two years. All that was left was to pick up the pieces of those who could not be saved. Corporal Gionet went through her entire supply of body bags. She then started to use baggies, and ran out of those as well. One of the baggies was being requested by a soldier who called on the radio to say that he had found a hand, but that it was not an adult hand. He kept repeating he needed a small bag for the small hand. I wonder if he was not saying that it was a child’s hand in order to avoid confronting what had happened to the child.

There were no Afghan or Coalition military personnel or installations in the vicinity of the blast—only civilians. And how did our enemies, the authors of this atrocity, choose to follow up on their actions? Did they express any regret? Did they say it had been a mistake? No. A few of them opened fire on the QRF. The ANA soldiers present quickly drove them off.

For the next four and a half hours, the Canadian QRF kept the site secure while Canadian infantry searched through the rubble with digging equipment, search dogs and their bare hands. They found only more body parts.

Sometime after midnight, an American unit arrived to take over from the Canadians. As Corporal Gionet was getting ready to leave, she had her second head-spinning experience of the evening.

Although the Afghans had conducted the evacuation of the wounded from the blast site efficiently, they had brought all these patients to hospitals with limited resources. Some of the walking wounded were therefore given first aid and told to return in the morning for definitive treatment, such as suturing or casting. One of these partially treated patients was brought to Corporal Gionet.

The patient in question was an eleven-year-old girl who had been brought to the Bison on her father’s back. The parents asked if it were possible for their child to be seen by a female medic, but Corporal Gionet got the impression that this consideration took a back seat to getting their child well treated. She invited the patient and her parents into the ambulance. Then, her world shifted.

The mother sat down across from Corporal Gionet, promptly removed her burka and fairly threw it at her husband. She then began speaking in fluent English, describing her child’s injury and thanking Corporal Gionet for agreeing to see her.

As a Bison medic assigned to a combat team, Corporal Gionet’s contact with Afghan civilians has almost exclusively been in the context of a combat operation. The connection she was able to achieve by caring for the child would have been remarkable in and of itself. But she was also able to connect directly, without interpreters, to another woman. “This was the first woman I have met here that I didn’t have to search,” she said. She found the experience extremely rewarding.

I wish every Canadian could have heard the conversation between Corporal Gionet and the mother. This Afghan woman could not comprehend why Corporal Gionet would have come all the way from Canada to help the Afghans. She emphasized to Corporal Gionet that this was very dangerous, as if she was unsure whether the corporal fully understood the risks Coalition soldiers face here. But as difficult as it was for this Afghan to grasp that Canadians would come here and risk their lives to help her, she and her husband were nonetheless deeply appreciative.

She then said something that should be juxtaposed with the media reports about the election. She said that there had been far less violence on election day than she had feared there would be. The Tal-iban attacks, other than in Zhari-Panjwayi, had been pinpricks, in her opinion. The media had made it sound like the roof was caving in.

Corporal Gionet finished taking care of the child. The girl had a nasty laceration on her knee, which was closed and bandaged. Throughout the treatment, the child remained calm and stoic. Once Corporal Gionet was done, the daughter reattached herself to her father’s back and the family headed off.

In talking to the mother, Corporal Gionet had discovered that the young girl was going to school. The mother felt very strongly about this—in a city where the Taliban will throw acid in the faces of girls who try to get an education. If they do not kill them. This family is fighting the Taliban as much as we are.

AUGUST 27 | Quick Draw

Earlier I introduced the “Battle Captain” of the armoured squadron. The equivalent in the infantry is the “LAV Captain” (“Capitaine d’assaut” in francophone units), an individual who plans operations and missions. The LAV captain of Combat Team Cobra is Captain Sacha Bois-vert-Novak. From my trips to the command post and the card table, I have gotten to know him and have enjoyed his company.

Captain Boisvert-Novak knew he wanted to be a soldier from childhood and joined up when he was only seventeen. He had his university education paid for by the CF, earning a degree in political science. Given the complex nature of international conflict in the twenty-first century, this will no doubt serve him well.

Captain Sacha Boisvert-Novak, battle captain*

After graduation, Captain Boisver t-Novak completed his infantry officer training as well as paratrooper training. He then reported to his infantry battalion and began work-up training to come to Afghanistan on Roto 4. He spent most of his time on his first tour as a liaison officer with the British Gur-khas. Returning to Canada after Roto 4 , he immediately volunteered to return to Afghanistan. His wish was granted, and he was given that most coveted of positions for a young officer: infantry platoon commander in a combat team. But halfway through the year-long work-up training for Roto 7, his assignment was changed.

Captain Boisvert-Novak’s other assignment on Roto 4 had been to oversee the digitization of many of our command and control systems. As a combat officer he was not thrilled to be surrounded by techies and computers instead of infantrymen, but he did a fantastic job. Maybe a little too good—when Major Jourdain, the combat team commander, was rounding out his leadership team, he came looking for Captain Boisvert-Novak. As battle captain, he has made the command post “100 per cent more efficient” (in the words of Major Jourdain) because of his intimate knowledge of all the new technology.

Captain Boisvert-Novak, however, was bitterly disappointed. The accelerated promotion (coming two years sooner than it normally would) and the esteem of his superiors could not fully erase the frustration of no longer commanding men “at the sharp end of the stick.” But he is a soldier first and foremost; he took up his new post without complaint and with considerable energy. He is the only veteran among the officers of the combat team. As battle captain, he draws on his experience to advise the commander and to counsel the junior officers.

Joined the army at seventeen. Paratrooper. Volunteered for a combat tour, then a second one. Has already volunteered for a third. Civilians reading that curriculum vitae may decide that Captain Boisvert-Novak enjoys war, for some deranged reason. The motivation for such a career path is best explained by David Grossman in On Combat:

Everyone has been given a gift in life. Warriors have been given the gift of aggression. They would no more misuse this gift than a doctor would misuse his healing arts, but they yearn for the opportunity to use their gift to help others. These people, the ones who have been blessed with the gift of aggression and a love for others, are our warriors.*

Here’s how a warrior like Captain Boisvert-Novak puts these words into action. If you look in the dictionary under “phlegmatic,” you will see a picture of Captain Boisvert-Novak. Whether he is helping to coordinate the defence of the FOB while we are under attack or winning (or losing) a gigantic pile of poker chips, his face remains inscrutable. I had formed an impression of him as being unshakably calm in any situation. That impression was dramatically confirmed at supper yesterday.

Captain Boisvert-Novak and I, along with a couple of the combat team’s senior NCOs, were dining together at the same table. The discussion was lighthearted and jovial, mostly centring on how best to ingest massive quantities of alcohol while on leave. Everyone was enjoying themselves, things were quiet and the day’s work was done. So we lingered, remaining seated at the table long after our meals were eaten and the rest of the soldiers had left the mess tent. We were comparing stories of earlier excessive alcohol intake when the unmistakable sound of an automatic rifle on “full auto” was heard coming from much too close.

In unison, everyone seated at the table dove onto the concrete tent pad. The firing continued, but no holes were appearing in the canvas wall of the mess tent. Either the shooter’s aim was off or he was hitting some of the concrete barriers surrounding our tent. He could also have been shooting at something other than the mess tent.

I must explain that whenever we leave the FOB, we wear all our protective clothing. We are heavily armed and ready for anything. But when we go to dinner, we are only wearing our combat uniforms or gym clothing. The only weapon we carry is a 9 mm pistol.

With that background in mind, we return to the three senior soldiers and me as we land on the mess tent’s concrete floor. There was gunfire outside. Without leaving the tent, we had no way of knowing what was going on. Everybody was thinking about the worst-case scenario: Afghan soldiers who had never shown signs of disloyalty suddenly turn on their Coalition allies. Had a Taliban infiltrator made his way into the FOB?

Civilian readers might think that staying close to the floor inside the tent would be a reasonable option here. We could aim our weapons at the doors and challenge anybody who tried to come inside. This group of Canadian soldiers felt differently. Anyone attacking our FOB would have to fight their way in. In unison, we stood up and started running to the door.

In the few seconds it took us to get to the other side of the mess tent, we all had our pistols out of our holsters. I was so focused on the door that I experienced a classic case of tunnel vision.* But while I could not see my comrades, I could clearly hear the metallic chick-kachick of all our pistols chambering around. We did not have rifles, frag vests or helmets, but we were ready to fight if necessary.

FOB Sperwan Ghar mess tent (letters A and B indicate positions relevant to the story)

Because of where I had been sitting, I reached the door first. I went outside, turned to my right (the direction the firing had come from) and took cover behind a concrete barrier (position A in the photograph). That was far enough for me, but not for Captain Boisvert-Novak. I watched in amazement as he went running across the open ground in front of me to the next good position of cover some ten metres away. No frag vest, no protective gear, just a desire to protect his comrades.

From position A, I could not see very far at all. Captain Boisvert-Novak had sized that up in a heartbeat and gone to position B, from where he had an excellent view of the nearest side of the ANA barracks. I heard him call out to someone, asking where the firing had come from. In a few seconds, he had determined that the enemy shooters were still outside the FOB walls. The loud gunfire we had heard was likely someone on our side shooting from inside the FOB. Only then did Captain Boisvert-Novak turn and lead us back to the shelter of the command post.

As we headed inside, the heavy machine guns on the hilltop opened fire. Combined with the fire from the defensive positions on the FOB perimeter, this quickly drove the attackers away. Throughout this episode, Captain Boisvert-Novak looked like he was out for a Sunday stroll. As I said, phlegmatic.

AUGUST 28 | Doctor in an Undoctored Land

I have made a conscious effort to get to know the ANA soldiers at this FOB. Effort is perhaps too strong a word. All I have done is sit down to dinner with them two or three times a week and dropped by occasionally during the daytime for a conversation. But these regular visits have marked me as someone with a sincere desire to connect with the Afghans. This affection has been returned several times over.

I also warmly welcome the Afghan soldiers who come to the UMS and I try to make them feel at ease with my rudimentary Pashto. This has led to an increase in visits by Afghan soldiers to the UMS. This exposure to patients from another culture prompts me to make two observations.

In these parts of the world, modern Western medicine represents something of great value, something the people here could never afford. When they can access such medicine for free, they come to see the Western doctor with a minor ailment: a stuffed-up nose, a sore back or, my favourite, “total body pain” (a complaint I have now heard from at least five distinct cultural groups). They do not really think the problem will go away. They only want to have the experience of being seen by someone who appears to them to be a miracle worker.

A lot of Westerners fail to appreciate this and go down one of two erroneous paths. The first mistake is to assume that the patient has a serious condition. This may lead doctors to provide treatments that are unnecessary and sometimes harmful.

The second mistake lies at the other end of spectrum. This occurs when Westerners assume that the patient is malingering. In these instances, the doctors often get angry and rudely show the patient the door.

The best way to deal with these situations is to respond as you would during any other patient encounter. Sit down, give the patient your full attention, take a thorough history and perform a careful physical exam. These patients want the same thing that patients in our emergency departments want: to be listened to, and to have the feeling that someone cares about them.

Beyond that, they often want a taste of high-tech medicine, and frequently ask for IV medication. But these people are not all that different from us. By giving them a sympathetic ear, I can achieve as much or more healing as I could by shooting them full of antibiotics. I have been here nearly four weeks now, and I have not given a single injection or intravenous drug to an Afghan soldier. And yet they seem very pleased with the service they receive.

The second observation has to do with a subset of patients who are unlike any I have ever had to deal with in emergency medicine in Canada or anywhere else in the world. At least once every three or four days, one of the Afghans on the base will come to me with a complaint having to do with sexual function. Not sexual dysfunction, but sexual function: things are going too well.

Usually, this takes the form of wet dreams. As observant Muslims, the patients are disturbed by nocturnal emissions because they are “unclean.” The first time I heard that one, I recommended the patient masturbate before going to sleep. I was informed that, because of the Islamic religion, this was not going to happen.

Talk about irony! Theologically enforced sexual abstinence causing a desire that theologically enforced rejection of masturbation renders one unable to relieve. I was left to recommend that fallback of the British boarding school, the cold shower.

At the other end of the masturbation spectrum, a member of the interpreter staff arrived with a complaint that he was initially reluctant to describe. After some beating around the bush, he came out with it: he was masturbating so often and so vigorously that he had developed arm and back pain.

The physical exam was . . . unremarkable, as we say. The patient was discharged with anti-inflammatory medication and reassurance that this was normal behaviour for a nineteen-year-old male.

The things that bind us together as human beings: parents love their offspring, children need lots of fresh air, the elderly are smarter than anyone thinks and adolescent males will jerk off until their dick and/or hand drops off.

Addendum, September 6, 2009: As if to prove the above observation, a Canadian soldier came in today with the following complaint: “Every time I masturbate, I see little brown specks in my sperm.” And how long has this been happening? “Twice a day for two months.” And this concerns you now because . . . ? “I dunno. I thought it would go away.”

AUGUST 29 | Company Sergeant-Major

Since I have re-enlisted in the CF, I have been gratified to see the esteem that ordinary Canadians have for those who wear the uniform. Even individuals who oppose our mission in Afghanistan make a clear distinction between the mission and those who carry it out. There is none of the vile rejection of soldiers that was seen in the United States when American soldiers returned home from Vietnam. Instead, a common slogan of the anti-mission side is that they support the troops and do not want to see us hurt or killed in a mission they feel is flawed. I disagree with that view, but I respect it.

This affection for the troops, however, does not translate into an understanding of our world. To appreciate this next section requires a basic knowledge of the ranks of the combat team’s leadership. I will provide an abbreviated version of it here.

The army is divided into two distinct groups: officers and enlisted men. An adequate civilian analogy would be that the officers are management whereas the enlisted men are labour. The military reality is much more nuanced. While it is true that the officers lead and make the decisions, they do so in close collaboration with the senior enlisted men. Although the most junior officer has the authority to give an order to the most senior enlisted man, in practice that would never happen. Instead, officers work as partners with enlisted men who have been in the army roughly ten years longer than they have. Like parents, they may have vigorous disagreements behind closed doors, but they will never oppose one another in front of their subordinates.

The most senior enlisted man in the combat team is the company sergeant-major. This position is held by a master warrant officer, the second-highest rank among the enlisted men. When I joined my battalion as a junior infantry platoon commander, there was a sign on the orderly room wall that summarized the various ranks in the company:

MAJOR: Commands the company. Faster than a speeding bullet. More powerful than a locomotive. Able to leap tall buildings in a single bound. Walks on water. Raises the dead.

Relationship to higher authority: Has lunch with God every few days.

CAPTAIN: Company second-in-command. As fast as a speeding bullet. Wins tug-of-war against a locomotive two out of three times. Able to leap tall buildings with a running start. Can swim across the ocean. Performs open heart surgery with a bayonet.

Relationship to higher authority: Has weekly meetings with God.

LIEUTENANT: Platoon commander. Pedals a bicycle faster than a speeding bullet. Carries a heavier load than a Mack truck. Can clear a multi-storey building if there is a trampoline to assist him. Able to swim across Lake Ontario. Can perform life-saving CPR for hours.

Relationship to higher authority: Talks to God on the phone.

COMPANY SERGEANT-MAJOR : Catches bullets and eats them. Throws locomotives off the tracks. Lifts tall buildings and walks under them. Freezes water with a single glance. Tells you when you can die. If he does, drop dead immediately. Stay dead.

Relationship to higher authority: IS GOD!

Any questions?

Now that we have clarified the rank structure, we can go on. Because no description of the leadership of a combat team would be complete without describing the man who holds the thing together, the company sergeant-major.

Major Jourdain, like all combat team commanders, has a second-in-command. This post is ably filled by Captain Hugo Dallaire, a senior captain of long experience. He is capable of taking over and running the combat team if anything were to happen to the major, and he did so during the commander’s leave. But if Major Jourdain has a right-hand man, it is his company sergeant-major.

This person is the essential link between the major and the men. It is the sergeant-major that the commander turns to for assistance in dealing with morale and discipline problems, providing invaluable advice when the commander has to make the most difficult decisions.

Earlier I quoted David Grossman’s explanation of the motivation of the warrior. Grossman goes on to explain that a person is not born to be a warrior but can make the choice to become one. If ever there was an exception to that rule, it is Master Warrant Officer Guy Lapierre.

MWO Lapierre can remember wanting to be a member of the CF since he was five years old. He spent his childhood and adolescence dreaming of joining the Canadian Navy. When he turned seventeen, he headed straight for the recruitment centre. The power of the open ocean and the excitement of foreign ports were only days ahead. Then a rather large fly landed in his career ointment. The economy was in recession and the army was having no trouble recruiting. When MWO Lapierre came looking for his long-awaited job as a sailor, he found that they had all been taken. He was told that the waiting time to get a position in the navy would be a year or more.

Seventeen-year-olds are not known for their patience. The recruiting officer must have sensed this. There is no other way to explain what he proposed next: “You can’t get into the navy for at least a year but . . . you can be in the infantry in three weeks!”

Translated into civilianese, that would be: “If you want a career on a clean boat, wearing clean clothes, eating three square, hot meals a day, you have to wait for twelve months. If you want to carry a heavy pack through swamps while eating scraps of freeze-dried crud, you can start working right away.”

As often happens when males are in their teens, testosterone won out over patience and good judgment. MWO Lapierre signed up on the spot and found himself in an army uniform within the month.

MWO Lapierre’s high testosterone levels now put him at a distinct advantage. After his basic infantryman’s course, he was sent to the paratrooper school. He was then assigned to the Airborne Regiment, the most elite formation in the CF. He must have been one hell of an impressive kid; he got into the infantry a year after I got out, and I knew soldiers who had been trying for three years to get into the Airborne. Being accepted into that regiment after basic training would be like being invited to play high school football . . . in Grade 7.

MWO Lapierre, who had so wanted to be a sailor, proceeded to have a career dominated by the most intense infantry experiences imaginable. During a decade as a paratrooper, he made the rounds of the more arduous peacekeeping missions Canada was involved in, including tours in Cyprus in 1986, Bosnia in 1993 and Haiti in 1997.* The most impressive part of his résumé, however, would have to be the two years he spent testing paratrooper equipment.

The conversations during these two years would have gone something like this:

(Note: Before any other old paratroopers out there think I am exaggerating, let me tell you that I have seen the video—not of the conversations—the video of the jumps. If I hadn’t seen it, I wouldn’t have believed it. But it happened exactly as I am about to describe.)

“Lapierre! We have this new rucksack/piece of gear/whatever. But there’s a chance it will completely screw up the flight characteristics of the free-falling paratrooper, get tangled in his chute and he will crater.

Strap it on, go jump out of a plane and tell us how well it works. Or not.”

“Yes, Sir!”

“Lapierre! That seemed to work when you jumped by yourself, so we want you to do the same jump, but ‘tandem.’ Attached to another paratrooper. That way, we can drop paratroopers more closely together. But there’s a chance it will completely screw up the flight characteristics of the free-falling soldiers. They could get tangled in their chute and crater. Go jump out of a plane and tell us how well it works. Or not.”

“Yes, Sir!”

Even the most determined soldier would be having second thoughts about his career choice at this point. But the main event was still to come.

“Lapierre! We want to see if we could drop a paratrooper with a big bunch of gear at the same time. They could drop food into famine areas or large amounts of ammunition to our forces, with pinpoint accuracy. So we want you to strap this gigantic barrel to your chest harness. It is five feet high and two and a half feet across. It weighs 630 pounds. You will fall much faster than normal paratroopers do, and there’s no telling what might happen. It could get tangled in your chute, and you will crater. With the barrel on top of you. Strap it on, and go jump out of a plane and tell us how well it works. Or not.”

“Yes, Sir!”

There is an old joke about undesirable jobs whose punch line was “parachute tester.” MWO Lapierre did it for real.

He describes his time at the Airborne School as having been the most enjoyable of his career. But he has the warrior’s skills, and he lives by the warrior’s code. There were evil men doing evil things, and his country was at war against them. There was only one place he wanted to be.

He started to angle for a combat posting on Roto 4. Having seen war in Bosnia and misery in Haiti, he had no illusions about what he would be facing. He was nonetheless frustrated when he was not chosen. For the men of Combat Team Cobra, that was a good thing: it meant that he was available to come with them on Roto 7. Major Jourdain knew a good thing when he saw it and snapped him up. This made it easier to staff the rest of the combat team. MWO Lapierre’s reputation was such that soldiers from other companies were asking to transfer into Combat Team Cobra to serve under him.

If I tell you that MWO Lapierre is the very picture of what the ideal sergeant-major should be, most civilians will think back to the tongue-in-cheek description at the beginning of this entry and imagine that he is a fire-breathing terror. But while he can be harsh when the occasion calls for it, that is not his leadership style. On the contrary, this soft-spoken man motivates his troops by being tougher on himself than on anyone else.

He starts off by being in amazing physical shape. He has been in Ironman competitions, and he has come at or near the top of any group physical fitness test that he has ever participated in. In a group as fit as the paratroopers, that would be impressive enough. Call that Airborne tough.

But what does it become when you learn that MWO Lapierre broke his back in 1996? And was told he would never be in the infantry again, much less jump out of airplanes? And then attacked his rehab program with such determination that he was doing parachute jumps again eighteen months later? That is sergeant-major tough.

Master Warrant Officer Guy Lapierre in his element: the field

MWO Lapierre brings the same energy to everything he does. He pushes himself to always be more upbeat, more confident, more “together” in every way a soldier can be than any of the men who serve under him. In private conversation, he is candid about his weaknesses. For instance, he admits that he is not as good a public speaker as other men in his position. He compensates for this by working much harder than they do to get to know his men. When he speaks to them one-on-one, the impact is magnified.

The thing he enjoys least about his job is dealing with the interpersonal conflicts that are inevitable in any large group. This falls to him when it cannot be resolved at a lower level, so he gets to deal with the worst cases. But he knows his men so well that he can see the value in each one. This makes it challenging to resolve their quarrels—he can always see both sides.

When I asked MWO Lapierre to summarize what it meant to be a sergeant-major, he replied without hesitation. He sees himself as a teacher, one who demonstrates for the undisciplined the advantages of superb self-discipline.

Like all Canadians, MWO Lapierre is proud of our role as peacekeepers. But he also describes, with passion, the outstanding performance of Canadian combat soldiers in every war we have ever been involved in. He sees no contradiction in being good peacekeepers and good warriors. The job we have here in Afghanistan calls on the attributes of both.

MWO Lapierre is living the crowning achievement of an outstanding career. He does not enjoy being at war but, like most of the soldiers here, he has been given “the gift of aggression.” He is where he needs to be, not where he wants to be. He is serving his nation to the best of his abilities.

What is he getting out of it? He speaks with remarkable sensitivity and insight about achieving as much personal growth as possible from the experience. He feels that most of this growth will come from having been a member of a team, a team involved in the most valuable work a group can possibly do: bringing hope where there was none before.

AUGUST 31 | RCIED: Radio-Controlled Improvised Explosive Device

Every day, small groups of Canadian soldiers go into some of the most hostile territory on Earth. Reconnaissance patrols seek to obtain information. Ambush patrols lay traps for Taliban infiltrators. Some patrols escort our officers to a shura with a local elder. Others are “presence patrols” that make the point that we can go wherever we like. The territory the media likes to describe as being under Taliban “control” is territory they cannot stop even a few of our soldiers from traversing.

It is during these patrols that the skill of the Canadian soldier becomes overwhelmingly apparent. By day and by night, these men and women will engage in an activity that requires the peak level of the warrior’s craft. Camouflage, tactical movement, silent communication and combat skills must all be of the highest order.

The patrol that left at first light this morning was tasked with an engineering function. Led by Lieutenant Jonathan Martineau of the 5th Combat Engineer Regiment, their goal was to weld grates onto a culvert that passes under the main access route to the FOB. It is easy for the Taliban to sneak an IED into such culverts. They use the cover of darkness, civilian passers-by or even a wandering herd of sheep to gain access to the culvert undetected. Because they do not have to dig, it takes only seconds for them to place their lethal device. This obliges us to clear the road at least once a day, a time-consuming and occasionally dangerous task. The heavy metal grates would make it more difficult to access these culverts.

Accompanying the patrol this morning was Corporal Pascal Girard, the thirty-two-year-old combat medic assigned to Captain Lussier’s First Platoon. This platoon had just come back from two weeks of QRF duty. This was an exhausting time for Corporal Girard. When the QRF was called out, as it could be several times in a single day, it was common for Captain Lussier to assign only a portion of his men to the task. But it was necessary for the platoon medic to go out every time.

With his platoon back at the FOB, the soldiers of First Platoon now had to assume their share of the patrols. Most of these would not involve all the men of the platoon, but a medic has to go every time.

Master Seaman Cloutier, the senior combat medic, tries to even this out between the medics on the FOB. The fact remains that these young people work hard and are exposed to tremendous risk. I have never heard any of them complain about that.

The diagram accompanying this story offers a visual representation of the ground. When the patrol arrived at the culvert, Corporal Girard, the medic (M), took his place in the security cordon. From here he could cover the footpath which headed northeast. With his back against the wall of the abandoned family compound, he was invisible to anyone coming from the south. Because of the position of the sun, anyone coming from that direction would cast a shadow that would alert Corporal Girard to their presence before they came around the corner. Lieutenant Martineau (L) stood close to the culvert, supervising his engineers (E). Sergeant Luc Voyer (S), commanding the infantry, stood between the lieutenant and the medic, with an interpreter, or “terp” (T). Other infantrymen (I) completed the security cordon.

While the engineers were performing their tasks, two children (C) walking down the footpath from the east approached Corporal Girard’s position. Sergeant Voyer went to meet them and began The blast site talking to them through the terp, immediately to the west of the berm of hard earth shown in the diagram. The children, a boy and a girl both about ten years old, offered the soldiers pomegranates. Sergeant Voyer asked them where all the adults were. The children explained that, it being Ramadan, most people were staying inside and not exerting themselves. Corporal Girard saw that the sergeant and the terp were now exposed to anyone coming from the south. The compound to the south of the footpath blocked the view of the infantrymen near the road. He therefore moved further east to better protect his sergeant. Then a massive explosion occurred. The sergeant, the terp and Corporal Girard disappeared in a cloud of smoke.

The blast site

Corporal Girard was hit by some gravel and rocks, but was unhurt. Remembering where the abandoned compound had been, he headed in that direction. When he found it, he turned west and followed the wall until he got out of the smoke. Then he called to his sergeant and the terp, guiding them out of the smoke by his voice. Sergeant Voyer reached him first. Having gotten his bearings, Sergeant Voyer went a short way back into the smoke, found the terp and brought him out.

Lieutenant Martineau could not believe they were all still alive. He had thought they were dead, given the size of the explosion and their proximity to it. His relief would be short-lived. Once out of the smoke and with the terp headed to safety, Sergeant Voyer and Corporal Girard both looked at each other and said, simultaneously: “The fucking kids!” Then they ran back to the blast site, still completely obscured by thick smoke.

It was an extremely brave thing to do. It was also foolhardy. The Taliban routinely plant secondary devices to kill Coalition soldiers who have the life-saving reflexes displayed by Sergeant Voyer and Corporal Girard. Lieutenant Martineau ran after them, screaming at them to stop. Although none were under his command, he has lost three engineer brothers on this tour. He had no intention of losing any more friends. He ordered the men to return to the road. Reluctantly, they obeyed.

As the smoke began to clear, the engineers moved around the south side of the blast site, checking for secondary devices and casualties. Corporal Girard and Sergeant Voyer stood on the edge of the smoke cloud, peering into the haze with their rifle scopes and listening for screams or moans.

Back at the FOB, we had no idea how bad this could get. I ordered all preparations to be made for a MasCal and my team responded superbly: within fifteen minutes we had three medics, ten TCCCs, two terps and a dozen stretcher-bearers standing by in and around the UMS. Our triage and holding areas were ready, and all our resuscitation gear, including our pediatric bag, was ready to go.

The engineers continued to inspect the blast site from the east and then from the north, crossing the stream at a small footbridge. Corporal Girard and the other infantrymen rearranged themselves to cover the perimeter.

As the engineers walked past the east side of the farm building, they noticed that two Afghan men were inside. There was no good reason for these men to be in that spot. They claimed to be working on the grapes, but these were already all hung to dry. The engineers brought the men back to the main body of troops to question them further. Along the way, they found three more Afghan men in another farm building farther south (not shown in the diagram), and they brought these men along as well.

The engineers had not seen any casualties, but Corporal Girard was still not satisfied. He headed down the footpath to stand right on the spot where the children had been when the explosion occurred. This was clearly against the lieutenant’s wishes. Corporal Girard figured he would ask for forgiveness rather than permission.

The explosion had taken place less than ten feet from where they had all been standing. Once there, Corporal Girard realized that their lives had been saved by the berm of hardened earth. It had deflected the force of the blast and most of the shrapnel over their heads. There was nothing on the ground, such as bits of clothing or blood or tissue, to suggest that the children had been wounded. It was evident that they had run away to the east. Only then did Corporal Girard relax.

With the site now secured, the engineers proceeded with what they call “exploitation.” This involves examining the blast site to learn as much as possible about how the enemy makes their weapons, so as to better defeat them.

No one had been standing on the mine when it went off. This ruled out any pressure plate or tripwire mechanism. No wires were leading away from the blast site. This left only one option: it had been an RCIED, a radio-controlled IED. The mine had been deliberately set off by someone who had been watching the place where it had been hidden. There was nothing accidental about this detonation. Someone had watched the Canadian soldiers and the Afghan children together and decided to trigger the blast.

That “someone” had to be close. The two Afghan men hiding in the farm building to the north of the stream were very suspicious. They told contradictory stories to explain what they had been doing in the area and how they had gotten there. They were tested for explosives residue. One of them tested strongly positive for military-grade explosives. Both were taken into custody. Tests on the other three men were negative. They were released.

The men were brought to the FOB, where we followed our standard procedure for detainees. The first step is to examine them medically, to document their state of health and any injuries they may have had prior to entering a Canadian or Afghan detention facility. If anyone mistreats these detainees, the military police and any investigative body will be able to refer to these documents. If injuries are later found that were not noted on the initial exam, then whoever is responsible for the detainee has some serious explaining to do. I had done a few of these “detainee medicals” during my first tour, and this one was no different.

After the two Afghan men had been interviewed, it was the opinion of the officer in charge of the process that the older man had been coerced by the younger one, either to participate in the mine attack or at least to vouch that they were both farmers.

Even if the Taliban had killed both of the children, it is unlikely you would have heard about the incident in Canada. This is incomprehensible to me. The only way we can justify our actions here is that they are occurring in the context of a moral war, and a moral war is defined by the degree to which our enemies are evil. The people we are fighting will not hesitate to kill children if there is a chance that they might wound one of us. So why does the media so rarely report these stories?

I felt no rancour towards this man as I examined him. He was a detainee now, and I would no more have mistreated him than I would have harmed my own daughter. I regretted that his world view was so opposed to mine that we had to struggle against one another with lethal force. And I wondered whether he and I could ever come to an accommodation that satisfied his obedience to his god while respecting my passion for human rights.

Face to face with evil

Addendum—March 27, 2010 About Detainees and Torture: “It’s worse than a crime. It’s a mistake”—attributed to various French diplomats of the Napoleonic era, referring to the execution of the Duke of Enghien.

A number of post-hoc justifications have been advanced through the ages to rationalize the use of torture. These range from the utilitarian—“ We needed to obtain information”—to the theological—“It is God’s will.”

The reason people torture in the first place is much simpler: for those who are capable of it, the act of torturing is enjoyable. If you do not think this is possible, watch a seven-year-old child burning ants. An individual whose ego is not well developed can feel greatly empowered by inflicting pain on another creature. For those who have been brutalized themselves, this can be tremendously gratifying. The gratification comes at the cost of even more long-term psychic damage, but the torturer is unable to appreciate that.

It is this underlying emotional trauma, or childlike immaturity, that renders the torturer incapable of accepting that torture has a dismal track record. But the evidence is overwhelming: quite apart from the fact that it is it utterly immoral, torture is also spectacularly counterproductive.

Prisoners who have valuable information represent a tiny minority of torture victims. There has never been any proof that these individuals are more likely to reveal this information under torture. Meanwhile, the great mass of those who are tortured have no useful information to divulge and will blurt out anything they think the torturer wants to hear. This leaves the side doing the torturing with a mass of misleading and contradictory data. The intelligence services must then expend an inordinate amount of time sorting through this junk, which distracts them and diverts resources that could and should be used more effectively. Even worse, torture guarantees that if the victim was not an enemy before, he or she almost certainly will become one.

I am bringing all this up because, shortly after I returned to Canada, the controversy over our handling of Taliban prisoners of war, a.k.a. detainees, exploded. This debate, like many others about the war in Afghanistan, has been marked by misinformation, a lack of context, political manoeuvring and hyperbole that is way over the top.

Let’s begin with some cultural context: harshness and physical violence are commonplace in Afghan society. Many Afghan men beat their wives, virtually all parents beat their children and superiors in any field occasionally beat their subordinates. I alluded to this earlier when I related that the Afghan officers I met during my first rotation would occasionally throw rocks at underperforming soldiers. Individuals who may have been involved in atrocities against Afghan soldiers, as would be the case with suspected Taliban prisoners, can be in for a rough ride from their Afghan captors.

It does not follow that the Canadian Forces had direct knowledge of systematic abuse. Our CDS, General Walter Natynczyk, has been pilloried for not being aware of a single memo in which a military policeman reported seeing an Afghan policeman hit a Taliban detainee with a shoe. It is a grotesque exaggeration to extrapolate from this that CF commanders had definite knowledge that “100 per cent of detainees” were being viciously tortured and that they ignored this information. We certainly had our suspicions, and those suspicions led to occasions on which we would stop transferring detainees to the Afghans. We even sent officials to monitor conditions in the Afghan jails. Our actions have led to vastly improved conditions for detainees when compared with the situation in 2006, when most of the incidents are said to have occurred.

What was happening to the Canadian Forces in Afghanistan at that time? In the four years leading up to that point, we had been stationed in Kabul. During that period, we had lost eight soldiers, only three—three—to enemy action, less than one per year. Then we moved into Kandahar province and took on the reorganized and reinvigorated Taliban on their home turf. The intensity of the combat we faced was several orders of magnitude greater than anything we had experienced before then, and we started dying at the rate of two a month. On top of that, our infrastructure was still getting organized; things were chaotic. It would have been impossible to track each detainee we turned over to the Afghan security services. It is easy now, in the calm of an Ottawa parliamentary committee room, to criticize the CF for having failed to protect these individuals. None of the persons doing the criticizing, however, have offered much insight into how this oversight should have been implemented.

Finally, nowhere in the detainee debate is there any kind of comparison to what our enemies are doing. Hundreds of Afghan soldiers and policemen have been captured by the Taliban since the beginning of the war. Nearly all of these men were tortured to death within days, if not hours. I described finding the bodies of some of these unlucky men on two occasions in my first book. There is no “detainee issue” on the Taliban side because there are no detainees. This is an important distinction to make. Our Afghan allies are imperfect. Some of them can be brutal, even sadistic at times. But they are nowhere near as bad as those we are fighting.

This is a civil war. We cannot fight it without the Afghans, nor would we want to. What we must do is continue to fight it in as moral manner as possible and, in doing so, show the Afghans a different way of thinking.

Again, education (writ large) is the solution.

“The highest result of education is tolerance”—Helen Keller.

SEPTEMBER 1 | Chuck

Corporal Pierre-Luc Vallières turned twenty-three today.

His best friend in the combat team, Master Corporal Charles-Philippe “Chuck” Michaud, would have turned twenty-nine next March. I would have liked nothing better than to have talked to Chuck myself and to have told you his story, but that is not possible. He was wounded on June 23 and died of his wounds on July 4. So I will tell you

Corporal Pierre-Luc Vallières

the story of his friend instead. Through that, you will get a glimpse of our absent brother. We are known by the company we keep, and Chuck kept very good company.

Corporal Vallières and I got together in a bit of a roundabout way. It is inevitable that a writer who is chronicling the lives of a group of soldiers at war will focus on the leaders. I have tried not to fall into this trap, writing about our front-line troopers in the tanks, artillery, engineers and health services.

I realized, however, that I had not yet included a member of the branch closest to my heart. I asked Sergeant-Major Lapierre to choose a soldier he felt best represented the combat infantryman. He suggested someone to Lieutenant Makuch, and the lieutenant agreed. They both felt Corporal Vallières was one of the best soldiers in the combat team.