MAY 31 | Departure

Going to war, a second time. How did I feel on this day? A lot different from the first time.

The last time I went, my preparations were rushed and my emotions were completely focused on the task at hand. Like a lot of soldiers, I disconnected from my family before I left. I particularly did not attend to my daughter very much. Michelle was only two then and not very verbal. My civilian job often took me away from home for days at a time, and Michelle’s lack of a sense of time seemed to protect her from any feelings of missing me. I thought the same thing would happen during my deployment. I was wrong. In the second week of that first tour my wife, Claude, found Michelle crying silently one night in bed. She asked her if she was crying because she missed her daddy, and Michelle nodded yes. It would not be the last time she cried during that tour.

As happens with a lot of men, my connection to my daughter deepened after she turned three and began to interact in what I considered a meaningful way. I knew Michelle would react even more negatively to my absence this time, so I took a number of steps in hopes of lessening her pain. The most helpful thing was purchasing a high-quality video camera to record myself reading bedtime stories for her. I spent the first minutes of my last day at home recording a few more.

I had been videotaping for about half an hour when Michelle woke up and came looking for me. This is her normal practice, as we both wake up earlier than Claude. Michelle and I will often spend an hour or more together in the mornings.

For a couple of months before my departure, our routine had been the same: I would put Michelle in a backpack and work out on our Stairmaster while we watched a movie. This was the only time that Claude and I would allow Michelle to watch TV, so she looked forward to our morning sessions quite a bit.

For the past several weeks, she always asked for the same movie: Monsters, Inc., an animated film whose central plot revolves around a father-daughter relationship. Michelle quickly learned that DVDs can be controlled, and she would ask for her favourite segments to be played over and over. By far the part she liked best was the ending, a rousing chase scene where the father figure struggles to save his “daughter” from an evil monster. She never seemed to get enough of that.

This scene is followed by a sad one in which the father figure must leave his “daughter” behind. Every time we viewed this scene, I explained to Michelle that her daddy would soon have to go away as well, for “a lot of sleeps.” I explained that it was okay to be sad and that Daddy was going to come back. She took this in very thoughtfully.

We had almost finished breakfast when Claude got up. Our conversation was cordial, with only a trace of the strain that had been all too evident before my previous tour of duty in 2007.

I was much more present for Claude in the period leading up to my deployment this time. I spent more time at home, and I tried to keep things as normal as possible. I never wore my uniform around the house, and I even let my hair grow longer. Most importantly, I remained emotionally focused on Claude as much as possible.

This is not to say that this deployment has been easier on her. What I am asking of Claude goes way beyond anything she imagined she would have to do when she entered into this relationship. Many of my friends have told me that their marriages would not have survived one combat deployment, much less a second.

I had finished packing the night before, so we were able to have a leisurely morning together as a family. But all too soon, it was time to put my bags in the car and head off. I spent one last minute looking around my neighbourhood before we left. Quiet, peaceful, prosperous. It seemed unbelievable that I was leaving this behind.

We first drove to my parents’ home. Claude chose not to come in, partly to give my parents and me some time to ourselves, partly because she felt it would be stressful to watch me say goodbye to them. She was right—it was an awkward moment.

My father is one of only two true pacifists I have met in my life, individuals who would be incapable of harming another human being even if they were being attacked. We have discussed the various crimes of the Taliban, and he recognizes that they are horrible abusers of human rights. It does not follow for him that Canadians in general—and his son in particular—have to go to war to stop them.

As for my mother . . . well, she’s a mom. Her spontaneous reaction, the first time I told her I was thinking of volunteering to go to Afghanistan, was: “If you do that, I’ll shoot you myself!” Although I knew six months ago I would be going back, I did not tell my parents until four weeks ago. This time, my mother said: “C’est une bêtise!” (“That’s really stupid!”). You could say that things are improving.

My mother’s initial reaction—motivated by her concern about my safety—was replaced within minutes by unconditional support. During my last tour, she e-mailed me every day and her messages were invariably upbeat and encouraging. I drew strength and comfort from those e-mails, more than my mom will ever know. I have no doubt she will do the same thing this time.*

We had a brief discussion about the mission and my role in it. It ended with my mother telling me that she would always support me, no matter what I did, as long as I always came back. I promised that I would, both of us knowing full well that might be a promise I would be unable to keep.

By the time we got to the airport, there were only a few minutes left before boarding. There is nothing good about being at the airport in this situation, so it is best if it is short and over with quickly. Claude and I shared a few more hugs and I love yous and it was time to go. Michelle was happy as I said goodbye to her and hugged her. She did not even seem perturbed when she called out to me, after I had gone through security, that “Mommy’s crying.” From where I was standing, I could see that Claude’s cheeks were dry. Michelle, sensitive as all children are to a parent’s distress, had noticed her mother’s shiny eyes. I replied to her that Mommy was crying because Daddy was going away for a lot of sleeps but that Daddy would come back. I repeated “Daddy will come back” at least four times.

After an uneventful flight to Toronto and a quick stop to get a regulation haircut, I called up a taxi company the army uses to ferry soldiers from Toronto to Canadian Forces Base (CFB) Trenton. You have almost certainly heard of this base, as it is also the place our fallen return: the “Highway of Heroes” leads from Trenton back to Toronto.

The ride to Trenton is a sombre one. You can’t help but think of the Canadian soldiers whose return to Canada was followed by a trip down this road. You can’t help but desperately wish you will not join them.

I got to Trenton in time for dinner. I reported in to the base accommodations (which were—by army standards—superb, like a good roadside motel), called Claude to let her know I had arrived, then went out for one last restaurant meal. I then went for a long walk by myself before turning in for the night. I tried to reflect on what I was doing, but I couldn’t focus.

I have given so many presentations since returning from Afghanistan that I am usually clear about why I am going back. But it is difficult to remember those motivations when I think about my wife crying, my daughter saying goodbye and the risks ahead.

I am going to war, again.

JUNE 1–2 | Getting to Kandahar: The Easy Way

My first flight from Canada to Kandahar had been a painful, prolonged and exhausting ordeal. Things were much better this time.

The trip began with a civilized wake-up at the unmilitarily congenial hour of eight o’clock. I threw on a pair of jeans and a T-shirt, revelling in my last chance to wear normal clothing. A short walk to the mess hall (cafeteria) next door was all that was needed to acquire breakfast. I then had to call a taxi to get from the sleeping quarters to the air terminal. And that’s where the civilian part ended. Waiting for me in the terminal were several dozen other individuals with short hair and military packs.

The plane we boarded was a gigantic Airbus model, owned and operated by the Canadian Forces (CF). When we boarded—via the forward hatch—we were met with some extraordinary institutional insensitivity. What was in the first-class section for all to see? Generals in comfortable seats? Politicians with their entourage?

Stretchers.

These same planes ferry seriously wounded Canadian soldiers home from the tertiary care hospital in Germany to which they are evacuated if they cannot be treated at Kandahar Air Field (KAF). We were on the outbound flight, so the stretchers were empty. Yet seeing these stretchers was sobering. I’m sure the administrators who organize these flights only consider the aircraft layout in terms of seating availability. They have probably never been on the aircraft itself, so they have never thought that it would be easier for all concerned if passengers entered only from the rear of the aircraft. This is not because of any discomfort I or other Canadian soldiers feel at the sight of our wounded. Rather, it is out of a desire not to intrude on them when they are so vulnerable.

After a couple of hours, I got up to stretch my legs and ran into an air force nurse named Rhonda Crew. We had worked together for a few weeks at KAF in 2008, and she had impressed me with her competence and collegiality. She was also pretty gutsy: she had volunteered to fly on the medevac helicopters, landing on battlefields to pick up our wounded. She had even been under small-arms fire during several missions. This means that Taliban soldiers were shooting at her with rifles and machine guns from a distance of a few hundred metres. As I said, gutsy.

Rhonda was in charge of the medical evacuation component of these flights. She was on her way to Germany to pick up a couple of our guys. I commented on the layout of the aircraft, and she agreed that it was far from optimal.

We compared notes about our activities since we had last seen each other, and I got updates on friends we have in common. We were soon joined by the nurse and medic who made up the rest of the medevac team. As frequently happens in our small army (including reservists, the CF has fewer than 100,000 people in uniform), we all knew people in common. The medic had served on Roto 2 and had been on the scene when Glen Arnold and David Byers, two soldiers from my part of northern Ontario, were killed in 2006. The nurse had served in the 1990 Persian Gulf War with a doctor who had been my roommate at KAF during my first tour.

The stopover in Germany lasted an hour and a bit. We all piled into a special military waiting area graced with the presence of a Subway restaurant, where I got one last dose of North American junk food. Six hours later we landed at a small, isolated civilian airport in the “host nation,” the Middle Eastern country that allows us to maintain a logistics base close to Afghanistan. After a short bus ride, we arrived at “Camp Mirage,” our pseudo-secret base in the aforementioned host nation.

Before I racked out, I called home. I had promised to call every day. To make sure that I would be able to do so no matter what happened, I had bought my own global satellite phone. Voice communication with Canada, even from here, can be a little iffy. It was wonderful to be able to simply reach into my backpack and talk to my wife and daughter. Expensive, but worth it.

With things settled back at home (as much as they could be) I was able to focus on what was coming next. “Battlemind” preparation, getting oneself emotionally prepared for exposure to combat, is an essential process for any soldier to go through. I had done very little of this before departure, for a number of reasons. As a veteran, there was no need for me to repeat many parts of the training process I had gone through the first time. Although this allowed me to spend more time with my family, it cut me off from my military brethren.

The military flight had not contributed much to my preparation. The host nation is extremely sensitive about having Canadian soldiers on its soil, so the trip is done in civilian clothing. You don’t feel very soldierly when you’re unarmed and wearing jeans and a T-shirt. And upon landing in the Middle East, the pilot wishes good luck to those who are “going up north.” No one seems to want to say “Afghanistan.”

After I got settled into my room, I went for a walk around the base to try to “get my head in the game.” Halfway around the world, alone and in the dark, having left a much-loved family behind and heading towards possible death or dismemberment, it can be hard to feel the clarity of purpose that was so strong a few months ago. The heart aches for peace and a soft, warm embrace.

JUNE 3 | Afghanistan Again

I woke up at 0900, dragged my gear over to the baggage loading area, then headed over to the weapons shack to draw my rifle, pistol and ammunition. This area is no longer a sea container but a real building; in the daylight I could see that the base had expanded considerably.

As we climbed aboard the Hercules, the transport gods (who had so cursed my last trip to KAF) smiled upon me yet again: the aircraft was only half full. There was ample room to stretch out. I tried hard not to sleep, to get over the jet lag quickly.

When we got to KAF, I went to the orderly room to get the routine in-clearance paperwork done.* I then reported to my company commander, Major Annie Bouchard, a little dynamo whom I had met during my pre-deployment phase.

Major Bouchard began by congratulating me on the impact that ultrasound has had on the ability of her medical company to provide cutting-edge emergency care. In the months before the company’s doctors and physician assistants (PAs) deployed, I had given them a basic Emergency Department Echo (EDE)† course and conducted advanced training for three of them. I had also gotten the SonoSite company to donate (Yes, donate! For use in a war zone!) three brand-new systems for the duration of the rotation for use on the FOBs, or forward operating bases. The guys I trained have been making excellent use of this gear, detecting injuries that would have been missed otherwise.

Major Bouchard then briefed me on my mission. It’s going to be a busy summer. A lot of enemy activity is expected, which we will do our best to counter. We will also continue to support reconstruction as much as possible. The “operational tempo” (military-talk for how hard we will be working) will be extremely high.

One thing hasn’t changed: this is still a civil war, and it is still the Afghans who are enduring most of the suffering. Since the current rotation (Roto 7) began in late March, only one Canadian soldier has been killed: twenty-one-year-old Karine Blais, the second Canadian woman to die in combat in Afghanistan. Casualties among Afghan troops and Afghan civilians have been high.

Major Bouchard then said something that struck me as very odd. It seems that, at the FOBs, I will be treating Afghan casualties almost exclusively. The helicopter evacuation system has become much more efficient in the eighteen months since I was here last, and wounded Canadians are almost invariably picked up from the battlefield by air medevac. Helicopters have also changed the way non-medevac functions are accomplished. Since February of this year Canada has had its own helicopter squadron at KAF for transportation and air assault missions. We no longer depend on our allies to fly us around. This should have a positive impact on our casualty rate, since most of our deaths have occurred as a result of roadside bombs striking our vehicles.

The major adroitly anticipated my next question. The Afghan army and police, she said, can call for helicopter evacuation, but to date they have not been fully integrated into the Coalition communication network. If they are not accompanied by a Coalition mentor, communication with the medevac choppers is extremely arduous. It is therefore more efficient for the Afghan forces to load their wounded, and even their dead, into the back of a truck and bolt for the nearest FOB.

I also learned that I will be joining this war very soon: I head for my first FOB at dawn tomorrow. That being the case, I had to draw additional ammunition as well as a desert-pattern flak jacket this evening. The ammunition was no problem, but getting my flak jacket proved to be a challenge because the clothing store where these items are kept is run by civilians and closes at 1800, and it was well past 2100 when I arrived. The clothing store supervisor explained that it was inconceivable—inconceivable!—that he would wake up one of his people to allow me to get the gear I needed. We had to get Captain François Aziz-Beaulieu, one of the senior officers of the medical company, involved. Captain Aziz-Beaulieu, who can bark with the best of them, resolved the problem. It seems that not everybody here accepts that we are at war.*

With all my gear collected, I went back to my room to pack. I started by loading my rifle ammunition into the (many) additional magazines I had been given. My infantry background shows when I do this. At the top of the magazine I load a few ordinary bullets, to be fired off quickly if a firefight starts unexpectedly. This gives the enemy something to think about, and gives me something proactive to do. That helps to calm you down, even if the shots are only vaguely aimed. By the time those shots are away I hope to be in good cover, trying to locate the source of the enemy fire. Once I figure out precisely where the bad guys are, I want some tracer rounds ready to go to indicate to my comrades where the enemy is. Finally, I leave my mags slightly underfilled, because mags filled to capacity are more prone to jamming.

I finished loading my two backpacks with what I would need for the next four months: clothing (which, given the heat, is pretty limited), my laptop, my DVDs and some books. I learned during my previous tour that the boredom of the FOBs needs to be countered with more than movies. After the first month, I was desperate for something to read.

By midnight I was done, and I stepped outside to call home. I couldn’t bring myself to tell Claude that I was headed outside the wire the next day. This meant that I could also avoid talking about the worst part of the next day’s activities: I will be going by road rather than helicopter. There is a convoy headed to my first FOB, and it makes more sense to send me now than to wait for a helicopter. The helicopters are so occupied with medevacs and combat operations that routine KAF-to-FOB transfers are unpredictable. It is essential that I get to my first FOB to provide coverage, so I have to go tomorrow. I will be going with the Bison (armoured ambulance) crew from my FOB. They returned from vacation today and are headed out tomorrow.

Going down the roads of Zhari-Panjwayi, the threat of roadside bombs and ambushes are ever-present. The place where most Canadian deaths have occurred.

The worst thing you can do.

After Major Bouchard told me that, she sent me to get my picture taken. I went to pack my gear instead. The picture in question is the one they show on the news when you are killed, the one with the Canadian flag off to the left. No way was I letting anyone take that picture.

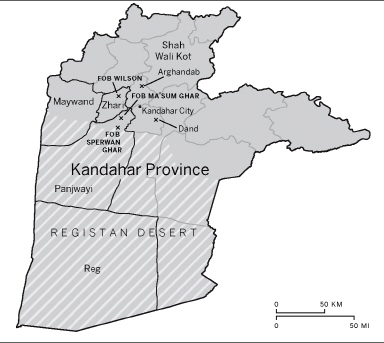

Afghanistan’s Kandahar province, showing three Canadian FOBs

Kandahar street scene: dilapidated building . . . with satellite dish*

JUNE 4 | Back to the FOB

I woke up at 0500 and spent the next half hour finishing my packing. The Bison crew arrived in front of my quarters half an hour later to pick me up. I jumped in the back and took my usual position in the right rear (starboard) “air sentry” hatch, and we drove off to the area where the convoy was being marshalled.

The pre-convoy briefing began with a description of enemy activity in the area we will be traversing. The briefer began with a map indicating the locations where the Taliban had planted bombs or had sprung an ambush in the past week. I couldn’t believe how much activity there had been between Kandahar City and the FOB. Things were not nearly this bad when I was here during Roto 4 , a “winter tour”. There has always been an increase in the fighting in Afghanistan in the summer, and it was clear that the “fighting season” was upon us.”

The view from Northeast Observation Post, looking south

There are a number of routes you can take to get to Zhari-Panjwayi from KAF. The one we chose took us through Kandahar City. This is a strange experience. You’re driving through a city of a half-million people that looks like many other communities in the developing world. This should be a cultural experience to be savoured. But here you’re riding in an armoured vehicle, part of a convoy bristling with heavy weapons. Every vehicle that crosses your path might contain several hundred kilograms of high explosive accompanied by an individual convinced that he will go to heaven if he blows himself up beside you. Your attention is focused on vehicles that are within fifty metres of your own. The city itself goes by in a blur.

Away from the city, the likelihood of suicide bombers decreases. That leaves the possibility of improvised explosive devices (IEDs) that are either remote controlled or wire controlled or that blow up when you drive or step on them. The correct term for this is VOIED—victim-operated improvised explosive device. I hate that term: it implies that it will be my own fault if I step on one of these things.

In the end, the trip was a quiet but nonetheless unpleasant drive.

At 1100 we arrived at the first FOB I will serve at: FOB Wilson. It lies at the northern edge of Zhari district and at about its east-west midpoint. It is the northernmost of our FOBs. It was named for Trooper Mark Wilson, who was killed in action near here on October 7, 2006.

FOB Wilson is the only FOB I did not serve at during my first tour. Its layout is striking: whereas our other FOBs are built on heights of land, Wilson is flat. It is a big square of Hesco Bastions (gigantic sandbags) plopped down in the desert. This explains why it has been hit by only two rockets in the past three years: it is difficult for these devastating but inaccurate weapons to hit a target that is flat on the ground.

This is not to say that the area around FOB Wilson is safe. Enemy activity is high, and one can watch Canadian and Afghan soldiers engage in close-quarters gun battles right outside the FOB’s walls. IEDs have even been placed no more than a hundred metres from the main guard post. Be that as it may, life inside the FOB walls is quite safe. Everyone walks around in T-shirts—no helmets, no frag vests, no ballistic glasses. Things are a lot more relaxed than they were at either of the FOBs I served at in 2007–08.

As for creature comforts, things have improved considerably since my first tour. We get two hot meals a day, breakfast and supper, served in a wide-open area with handwashing stations that make it easy to be hygienic. At lunch, the cooks lay out all kinds of salads, cold cuts and warmed-up leftovers from the previous night’s meal. The grub is fantastic. No more ration packs!

There are two “shower cans,” each with three washing machines and dryers! No more washing by hand!

“Triple-7” in action

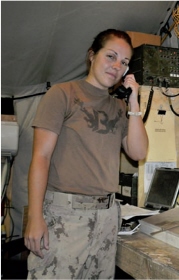

We have the same kind of communications shack I remembered from FOB Ma’Sum Ghar last time, with three Internet connections (mostly reliable) and three phones (somewhat reliable).

Right beside the Internet shack we have an amazing gym. It is named “Greener’s Gym” in honour of Sapper * Sean Greenfield, who was killed in action on January 31 of this year. There had been a gym at the first FOB I served at in 2007, but it was a dark, dusty place with only a small amount of gear. I think I went twice before deciding that pumping iron in that place was too depressing.

And get this. There is also a “Rock House,” a wooden structure the size of a large room with a climbing wall on the outside and a music studio on the inside.

In the UMS, the unit medical station, we have a wall of munchies, a large coffee maker (permanently filled), a toaster, a microwave oven and a fridge. And outside we have a large freezer, filled with water bottles that have been frozen—ice in the desert!

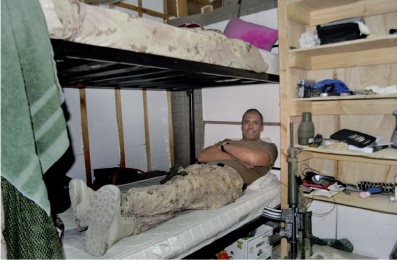

Instead of being in a bunker with five guys, I am in a “sea can” that has three curtained-off “rooms” and a central area that serves as an office. My bed has a mattress (no canvas cot!) and my “room” has an air conditioner.

The FOB is home to a combat team centred on a company of infantry, Bravo Company of the Second Battalion of the Royal 22nd Regiment, the “Van Doos”—the same French Canadian outfit I spent most of my tour with last time. They left for an operation this morning, so the base is deserted.

The only downside of living at FOB Wilson is that the M777 155 mm cannons are located less than a hundred metres from my quarters. They often have to fire right over my shack. This isn’t dangerous, but the noise and the concussion wave of the shot makes sleeping pretty much impossible.

The cannons can’t fire very close to the FOB—even with a minimum of propellant, the shells go too far. For close-in bombardment, the artillery has some 81 mm mortars. These weapons “arc” their bombs, making it possible for them to hit targets that are very close.

“The guns” (as everyone refers to the artillery) were busy today. Before the day was out, they would fire over eighty rounds in support of Bravo Company’s operations in the Panjwayi. This was one of the largest “fire missions” executed by Canadians since arriving in Afghanistan. The combat team had encountered an unusually high number of enemy while they were on foot and away from their vehicles. They had used the artillery to blast a path back to their “leager.” * After eight years of war, it is disappointing that there are still so many Taliban targets to shoot at—another disturbing indicator that things are not going as well as we would like.

But as badly as things might be going, I learned two things at the end of the day that convinced me we are doing the right thing here. Two things that got my battlemind to where it needed to be.

First, on the national scale. In 2007, the Taliban burnt or blew up 130 schools in Afghanistan, while forcing another 300 to close by threatening the teachers. They also murdered at least 105 students and teachers. Convinced of the correctness of this course of action, they have continued in the same vein since then.

If you look at everything written about Afghanistan in the news, you can catch a glimpse of this,* but it is something else to get a briefing that shows you, on a local map, all the schools that have been destroyed.

Locally, I learned that there is an Afghan medical clinic within sight of the FOB. This is the last functioning clinic in the area. Four others farther away have closed their doors because of Taliban threats. Apart from this last clinic and our UMS, there are no health care facilities of any kind in Zhari district. This does not seem to matter to our enemies.

Regardless of the challenges, regardless of mistakes we may have made, whatever our chances of success, Canada is in the right place. I am in the right place.

I am here to help defeat the Taliban. Let’s get on with it.

Addendum, June 9: Major Bouchard, ever mindful of the morale of the people in her company, called me tonight to see how I was doing. She asked how I was getting along with “the bayonets,” the slightly derogatory term used by the medical services to refer to the combat arms. I answered that I was getting along with them quite well, and I left it at that.

If I had known her better, I would have told her that I felt I was back with my brothers, and that I saw myself more as one of them than as a member of the health services. I am a bayonet.

Battlemind set—good to go

JUNE 5 | The Shop

Another night of lousy sleep, thanks to artillery fire over my head during the night and the first call to Muslim prayers from the Afghan National Army (ANA) compound ten metres away at 0430 (first light). I take over as FOB Wilson medical officer today—time to go to work.

The UMS is across the street from my quarters. There is also a four-stretcher tent close to it that can hold four more minor casualties. All told, the UMS can handle three times more patients than it could in 2007.

As a doctor, my first reflex was to be pleased with the improvements. I have spent a good part of my career in Canada pleading for more resources for emergency medicine, so I was chuffed to see that I would have more of everything with which to do my job than I’d had during my previous tour.

The FOB Wilson UMS

As a soldier, though, I was troubled. Those with access to far more information than I, our leaders and decision makers, believe that we are going to need these resources to care for a larger number of wounded. It seemed the major’s briefing two nights ago was bang on.

The UMS itself shows the effects of the lessons learned over three years of warfare in Kandahar province. Again, I was pleased to see that many of the recommendations I made after my last tour have been put into effect. The place functions like a small community emergency department in Canada onto which the resuscitation area of a Level 1 trauma centre has been grafted. The specialized medications and gear that I’d had to request for myself last time are already in place. The military medical staff may not be familiar with all this stuff, but at least it is here. This makes me as functional as possible, and it will give me the chance to do a bit of teaching with the person I am replacing.

The communications have vastly improved. We now have e-mail right in the UMS, a land line to the key places on the camp (command post, district centre, etc.), and a phone that can make a call to KAF or Canada as easily as a call across town back home. We also have secure communication devices that allow us to monitor what is going on with the units in the field so that we can anticipate their medical requirements. And my desk has drawers! We had none of this on Roto 4.

Wounded Afghans—who so far have represented 100 per cent of the casualties treated here—arrive via the main gate, regardless of whether they are military, police or civilian. This places them close to the UMS. Since they almost invariably arrive by vehicle, the warning call we get from the gate coincides with the arrival of the patients at the UMS door. For some reason, the Afghan soldiers and police rarely use their radios to alert the FOB of the arrival of their wounded.

It is therefore not unusual for a load of casualties to arrive at the doors of the UMS with very little warning. This is not unlike what I have been dealing with in emergency medicine for over a decade now, and it is something I have had a lot of experience with in the developing world. The worst MasCal (mass casualty) incident I ever dealt with occurred during the Nicaraguan Contra War and involved eighty patients, worse than anything Canadians have had to deal with in Afghanistan.

Rather unusually, the FOB had been covered for the past few weeks by a doctor, rather than by a PA. She has had additional training to prepare her for the trauma patients who dominate the caseload here, but she remains what the army calls a general duty medical officer, an office-based general practitioner.

The arrival of unscheduled patients was something she seemed to have found very surprising. She kept repeating over and over, “Patients will just show up!” as if to warn me of the probability of these anomalous events. I tried to reassure her that I had lived through these events many times before. As an emergency specialist, that is what my career entails: if bad things happen to people unexpectedly, I want to be there to take care of them.

Let me now introduce the crew of the Bison armoured ambulance based here. *

Master Corporal Nick Beaulieu (centre in the following photograph) is the crew commander. At the age of forty-one, Nick should be much further along in terms of rank. He is not lacking in courage— he still goes out on foot patrols when the combat units are short a medic—but he is one of those guys who is more comfortable with less responsibility and therefore less authority. You get the impression he has almost engineered various disciplinary incidents—some of them quite funny—so that he will not be promoted.†

The driver (left) is twenty-three-year-old Corporal Pierre Yves (“P.Y.”) Lavoie. P.Y. is on his second tour in Afghanistan, having been a convoy driver during Roto 4. P.Y. went down the roads of Zhari-Panjwayi—what I said yesterday was “the worst thing you can do”— almost every day for six months. He signed up for this tour two months before it was scheduled to go. Although he had never driven a Bison before, he quickly mastered the vehicle. He seems to be a natural around heavy machinery.

The Bison medic is twenty-nine-year-old Private Dominic Vaillancourt-Larose (even he laughs about the length of that surname). Like all our medics, he is extraordinarily competent when it comes to caring for a trauma victim. Dominic is also one of the most eager learners I have ever met in medicine: he is constantly asking me questions. There is also a medic assigned to the UMS proper, but he will not arrive for another week. Currently, that position is filled by Master Corporal Sylvie Guay.

The FOB Wilson Bison crew

Only one trauma patient today. An Afghan convoy guard was shot through the top of his foot. Through-and-through, no major damage, but ultrasound confirmed a fracture of one of his metatarsals (the bones that connect the toes to the foot), so I sent him to KAF for an orthopedic consultation. The helicopter arrived to take him away within thirty minutes. Cool!

There’s another positive aspect about being assigned to the FOB Wilson UMS. During my last roto, a Taliban rocket detonated about two metres from the UMS. The two medics inside were very fortunate: they survived with minor injuries.

I like to think that this makes it unlikely the UMS will get hit by another rocket while I am here. Statistically, that is incorrect. The odds of a rocket strike on a particular spot are always exactly the same, regardless of where one hit before.

In a war zone, superstition trumps statistics.

JUNE 6 | “Collateral” Damage

The jet lag was still beating me up this morning, and after a couple of hours I collapsed back into bed. The UMS is only ten metres from my shack, but I brought the UMS radio with me so that I would be immediately available. Emergency physicians never stray from their resuscitation area when they are on duty. And I am on duty here 24/7.

That turned out to be a good move: as I was entering REM sleep, Master Corporal Guay radioed that I was needed immediately. I staggered over and was still prying my eyes open when I came to the door of the UMS. Inside, I was confronted with something that is all too common in this war. Two children, one of them eight years old and the other one in his mid-teens, had set off a Taliban IED. They were “collateral damage,” a horrible term that tries to gloss over the fact that civilians are often killed and maimed in war.

The younger child had been hit by a half-dozen small pieces of gravel that had been thrown off by the explosion. His wounds were trivial, but he was very upset. Like most children who go through such events, all he needed was to sleep in the arms of someone who cared for him.

The older child was far worse off. The detonation had taken place no more than three metres from him. From the pattern of his injuries, it seemed that the mine had been placed in a soft plastic container. (Plastic jugs, not unlike the things you see at campgrounds in Canada, are used by the Taliban to store their explosives.) I drew this conclusion because the patient was shredded from his groin down to his calf on both sides, but there were none of the amputations or deep penetrations that occur when the explosive is encased in metal.

About a third of the soft tissue on both legs had been lost, giving the limbs the appearance of raw, bloody hamburger. The nerves remained at least partially intact; the patient was still moving both his limbs, although not purposefully. His abdomen and chest were untouched, but his face looked like it had been sandblasted. Both corneas were coated with grains of sand that had been forced into the tissue. His eyes must have been open when the blast occurred.

He was still breathing on his own, but he was semi-conscious, barely moaning when I tried to stimulate him by rubbing hard with my knuckles on his breastbone. He was also in shock: we could detect a pulse in his neck, but not in his wrist or in his groin. This meant that his blood pressure was somewhere around 70/nothing.

We proceeded with a straightforward resuscitation. We started two IVs, one on each arm, and gave the patient large amounts of fluids to bring his blood pressure back up. Meanwhile we prepared him for evacuation. Both his legs were swathed in pressure bandages and we administered two medications, etomidate to put him to sleep and rocuronium to paralyze him. Intubating—putting a breathing tube from the mouth down into the lungs so that we can take over breathing for the patient—can make patients vomit. If this happens when they are semi-conscious or unconscious, the vomit can be sucked into the lungs and choke them to death. Paralyzing the patient makes it far less likely that this will happen because the stomach can no longer contract and expel its contents back up into the throat.

The destination for this patient was none other than Camp Hero, an Afghan army hospital that opened its doors in February 2008 and at which I had done some teaching on my last tour. It is functioning at a high level now and is accepting a large proportion of the Afghan civilian and military casualties.

Addendum, June 7: The teenager is dead. No life-threatening injuries were missed; he had spent too long in shock before getting to us. This delay damaged the internal organs, notably the liver and kidneys, so badly that the patient died even though his injuries had been repaired and his lost blood had been replaced.

Events like these are so common as to be barely worth mentioning. The Taliban do not hesitate to plant their weapons in populated areas because they know our patrols go there to interact with the locals. Most civilian casualties in this war are caused by these incidents.

Remember that when you hear about American air strikes going astray. Yes, these incidents are tragic. They need to be investigated, and we need to do a better job to reduce these casualties. But when Afghan civilians are hurt by Coalition weapons, it is because we screwed up. When they are hurt by Taliban weapons, it is a direct and predictable result of intentional Taliban tactics.

JUNE 8 | Every Body Goes Home

It could have been a lot worse.

One of the platoons of Bravo Company, the company based at my FOB, had been clearing a dirt road, searching for IEDs. The four troopers who were leading the advance had come to an intersection. The road running to the left had mud brick walls on either side. Another wall of similar construction ran along the left side of the road leading straight ahead.

Three walls needing to be cleared, four troopers. The trooper in charge directed one of his men to start clearing the left-hand side of the side road while he sent the other two to the other side. Once there, these two split up. One headed farther down the main road, following the wall on the left side. The other one, Private Alexandre Peloquin, took the right-hand side on the side road and started moving away from the intersection.

He had not gone far when the IED detonated—but far enough that his partner was shielded from the blast. The trooper supervising the team from the other side of the road was knocked off his feet and temporarily lost his hearing, but was otherwise unhurt.

His buddies rushed to Private Peloquin’s side and started administering first aid. They were joined in less than a minute by the platoon medic, who did a superb job. But Private Peloquin’s injuries were devastating. Every part of his body that had not been covered by the fragmentation vest was torn apart. He was a big man, and very strong, but he lost consciousness almost immediately and died soon after.

This is the first fatality for this FOB and this company, and everyone is taking it pretty hard. Nothing can prepare you for this, not even having gone through it several times before. Unfortunately, I am not in a position to help the troops very much. As I am the “new guy” on the FOB, it would be awkward to reach out to them. For their part, the soldiers are unlikely to seek me out for support unless they are severely affected.

Our jobs as battlefield medical personnel did not end with the evacuation of the victim. We had one more important task to accomplish. Last December, Warrant Officer Gaëtan Roberge of Hanmer (a small village in Greater Sudbury) was killed by a roadside bomb. As with Private Peloquin, he suffered devastating injuries, including the loss of an arm. The soldiers with him that day, under enemy fire, had focused on trying to save their comrade and, failing that, extracting his body. We will never know for certain if the missing limb was vaporized, which seems likely, or thrown far away. Either way, the arm never made it home.

Warrant Roberge’s parents found this very hard to accept, and complained bitterly about it in a front-page story in the Sudbury Star. This was noticed by the CF, which tries to do the best that can be done for casualties and their families. It is now standard operating procedure to ensure that all human remains are collected. The combat team commander and the medics made sure, personally, that this was done.

Sounds grim, doesn’t it? It was. But by the time Private Peloquin gets on the Hercules, he will be whole.

Through the ages and in all cultures, there are stories of soldiers taking insane risks and sometimes even losing their lives to retrieve the bodies of their comrades from the battlefield. “Everybody goes home” is part of the soldier’s code. We are taking it one step further.

Every body goes home.

JUNE 9 | Pashtunwali

Some of the injuries I treated today were due to local societal norms, so this is a good time to delve into the subject of tribal society.

Most of the population of southern Afghanistan belongs to the Pashtun tribe. This is the largest tribe in Afghanistan, comprising some 42 per cent of the country’s population. Because the Taliban are drawn almost exclusively from this tribe, some Canadians believe the tribe is opposed to us. This is incorrect: most Pashtuns oppose the Taliban to varying degrees, often with very good reason. The current president of Afghanistan, Hamid Karzai, is a Pashtun who fought the Taliban for years before 9/11. Like so many of his countrymen, he too had a family member murdered by the Taliban, in this case his father.

The Pashtuns live by a strict tribal code of honour and behaviour called Pashtunwali. There are three key elements in Pashtunwali, the first two of which are closely related. Melmastia refers to the obligation to extend hospitality to anyone who arrives in one’s home. Pashtuns will deprive their own family of basic nutrition to be able to provide a meal to the visitor. Closely related to melmastia is nanawati, which mandates that hospitality can never be denied to any fugitive.

Afghanistan’s geography has had a large role to play in this. Since the time of Alexander the Great, this area has been transited by invading armies. No one cared about Afghanistan per se. The country is mostly rocks and desert—only about 20 per cent of its land mass is arable. It is the topography of the region—the high mountain ranges of the Himalayas and the Karakoram and the deserts of what is now southern Afghanistan and southwestern Pakistan—that has funnelled invaders through here as they headed somewhere else. Depending on which way they were going, these invaders sought to reach the wealth of the Middle East, the markets of Central Asia or the ports of the Indian Ocean. Several empires were built on any one of these prizes, and those same empires often tried to conquer the other two. An area that spent most of its time dealing with foreign invaders developed a social code that supported anyone who was fleeing, since the chance that they were fleeing a common oppressor was high.

But since good-news stories never have much traction, the existence of melmastia and nanawati are relatively unknown outside of Afghanistan. And since violence gets you on the evening news, a lot more people have heard about the third component of Pashtunwali: badal—the right of revenge.

The tribe takes this so seriously that it is not an exaggeration to say that crossing a Pashtun is one of the unhealthiest things you can do on this planet. There is even an ancient Hindu incantation to the gods, asking to be saved from various natural disasters and one human one: “The revenge of the Afghan.”

You might think that this cannot bode well for any kind of national reconciliation after so many years of civil war, but armed conflict between large groups doesn’t seem to trigger an intense need for badal.

To really make a Pashtun crazy, you have to go after his zar (gold), zan (women) or zamin (land). Then you have a blood feud on your hands. In every reference I have read on the subject, the order of these three is always the same: zar, zan, zamin. First gold, then women, then land. You can infer from that what you will.

On to today’s medical misadventures. Two young men arrived with stab wounds. One had a single wound to his upper arm which, though it was squirting arterial blood, was easy to control and to bandage. The other one had three small wounds in his upper back. One of these wounds was trivial, but the other two—one on each side of the chest a few centimetres below the shoulder blade—proved to be quite deep.

A quick look with ultrasound determined that the patient had a pneumothorax, popularly called a “collapsed lung,” on the left. In this situation, air has escaped from the lung and gone into the chest cavity. This air does not move in and out of the body with respiration, and as it accumulates it can exert so much pressure that the lung can no longer expand—hence “collapsed lung.” This is a Bad Thing: the patient’s oxygen saturation (a test that allows us to determine how well the lungs are functioning) was worrisomely low.

The treatment for this condition is to make a small hole above the fifth rib, in line with the middle of the armpit, and to insert a plastic tube into the chest cavity to allow the trapped air to escape. I punched through the chest wall and was rewarded with a satisfying “hiss” of pressurized air escaping. The patient’s oxygen saturation improved.

I then switched the probes on the ultrasound machine to look for bleeding in the chest and in the abdomen. The abdomen was fine. There was bleeding in the left chest, but I already knew that—it was coming out of the chest tube on that side. I discovered that there was also bleeding on the right, caused by the stab wound on that side of the chest. Blood can do the same thing as air: if too much of it accumulates in the chest cavity, it can also collapse the lung and provoke the same kind of breathing problems. So I zipped a second chest tube into him and managed to secure it as the medevac helicopter landed.

Lots of blood, lots of life-saving procedures, everybody alive at the end. The perfect emergency medicine interaction!

The unique aspect of the case was the “mechanism of injury.” It turns out that the two patients are cousins. They live in one of the ubiquitous mud brick dwellings that house most of the population here in the hinterland. These structures, called “compounds,” are designed with Afghan history in mind: a country constantly at war prepares for defence in even the most mundane of circumstances. Each compound resembles a small fort. The walls are thick enough to stop even a modern rifle bullet, and there is often a well in the centre of the compound. Add some food and ammunition, and you are ready for a siege.

Back to our story about the cousins. The compound they live in has two doors, one on the front and one on the side. Persons exiting from the side door are in a position to look into the neighbour’s backyard for a few seconds before they turn a corner. As said neighbour is unable to afford a high enough wall around his yard, there is the possibility that his women will be seen by someone exiting from the side door. These women would be in full burka, but would be unaccompanied by a male relative.

This was unacceptable to the owner of the house in question. He had warned the cousins that exiting through their side door was intolerable to him. This intervention failed to achieve the desired result: the cousins kept exiting via their side door. Their neighbour then took things to what was, for him, the next logical step: physical violence, with at least the possibility of killing the target.

View of several Afghan family compounds

(Photo courtesy Master Corporal Julien Ricard)

Close-up of corner of compound (the well is visible)

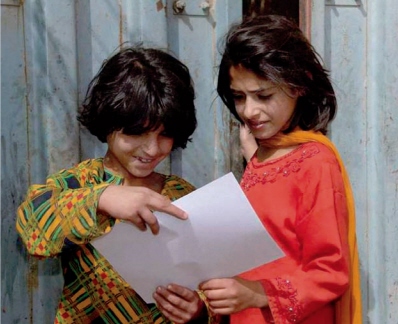

Graduation day

This kind of behaviour will have to be moderated if Afghanistan is to evolve. While a functioning government and legal system, backed up by a professional police force, will help, the lasting solution is education. Far more than any legal means or coercive system, it is education that rids humans of their baser instincts.

More precisely, we must focus on the education of women. Those of us involved in developing-world work have known for decades that the highest return on investment comes from educating women. It is much more likely that the skills acquired will remain close to the family and village of the person receiving the training.

Addendum, October 15: Under the Taliban, there were 600,000 students and 1,500 schools in Afghanistan. In 2007, those numbers were 6 million students and 9,000 schools. Despite the Taliban’s out-and-out war on the educational system, that system has grown by leaps and bounds: in 2009, there were 8 million Afghan children in school.

JUNE 10 | The Contractor

There is a man here who could be said to be performing both the oldest and the newest function in warfare. Let’s call him “the contractor.” In reality, the contractor is a composite of a few different people who are doing the same job. I have commingled them to protect their anonymity.

The contractor is a Canadian who has had extensive military experience in the CF, both in Canada and on various deployments. He was approached by a fellow veteran and asked to return to Afghanistan to work for a private security company. He agreed. For all intents and purposes, he is a mercenary, a soldier for hire.

The Iraq war saw the advent of companies that, for a hefty fee, would take over functions that previously had been the sole purview of the military. These included perimeter defence of bases, escorting supply convoys and even limited, but nonetheless aggressive, patrolling. The rationale was that these companies could provide additional manpower right away. No need for the military’s recruitment and training cycle, no benefits or pensions to pay during and after the individual’s employment.

The behaviour of these companies has been controversial. Thanks to a statute rammed through by Paul Bremmer when he was the “administrator” of Iraq,* employees of these organizations are not subject to Iraqi law. The problems caused by granting this immunity came to the fore on September 16, 2007, when employees of the Black-water company (now re-incorporated under the name of Xe) who were escorting a convoy through Nisoor Square in downtown Baghdad shot and killed seventeen Iraqi civilians. The Blackwater men claimed they thought they were under attack. They were mistaken. The incident was investigated by the FBI, which found that at least fourteen of the dead were innocent Iraqi bystanders. Despite this, none of the Blackwater employees have faced criminal charges for this incident (though a civil suit is ongoing).

A number of these companies are now active in Afghanistan, including the Canadian entry into the market, the company that employs the contractor. He has sixty-three men under his command, most of them ANA veterans who have been attracted to this job by the higher pay.

The contractor’s men take care of the “perimeter defence” of the FOB. This means they have the relatively easy job of protecting the base from attack. They staff various observation posts along the FOB walls twenty-four hours a day. These are strong defensive structures, with excellent fields of fire that are constantly illuminated. Thus the tedious guard post duty is removed from the list of chores our soldiers have to perform while on the FOB. If we ever face more than harassing fire on our walls, the Canadians will join the contractor’s men in repelling the attackers.

I asked the contractor the obvious question: if the Canadian Army is willing to pay these individuals more than Afghan soldiers receive, why not give the same amount of money to the Afghan government to fund the training of more soldiers? This would enhance the links between the population and the government by providing more government jobs while giving us closer control over these individuals.

The answer I got was quite reasonable. The contractor maintained that many of these individuals do not want to join the army, even for better pay, for any number of reasons. The private security company therefore gives us access to men who would otherwise be unavailable. The presence of these men on the gates of the FOB frees up far better trained and equipped Canadian soldiers to go outside the FOB and take the fight to the Taliban.

There is no question this is useful. We do not have enough soldiers to patrol all of Zhari-Panjwayi while defending our FOBs and outposts. Either we hire this company or we sit in our FOBs and let the Taliban run riot.

So it makes sense. Nonetheless, there is something disquieting about the concept of privatizing war. Although I can’t quite articulate why, I think that nations need to take responsibility for everything that happens when they decide to participate in an armed conflict. Putting some of the people armed by the state in a legal environment that is removed from military discipline doesn’t seem right. I am sure these companies would claim they are not “armed by the state,” but that would be a meaningless splitting of philosophical hairs. The state allows them to be armed and is their only employer.

The first Baron de Rothschild said, “When there is blood in the streets, buy property.” Cynical, yes, but he was stating an eternal truth: there is money to be made during wars. In its purest expression, that money is made by men who are willing to soldier for a fee. Until their most recent incarnation as organized, for-profit companies, mercenaries always joined a national army. They fought, albeit for cash rather than for ideals, under the command of an existing military structure. What we are doing now separates the mercenary from the army he is serving.

JUNE 11 | The Things I Miss, the Things I Enjoy

Today is Michelle’s fourth birthday. Although we celebrated it a few days before I left, it is still the first important family event I will miss on this rotation.

I can’t help but wonder what the long-term effect of this absence will be on my daughter. I plan to cut back on my professional activities for several months after I return from this mission, to try to make up for my time away. I worry that that will not be enough.

As much as Michelle’s future emotional well-being concerns me, I didn’t have much time to think about it today. FOB Wilson sits astride Ring Road South, the main highway that runs the length of the northern edge of Zhari district. This road links Kandahar City with the district of Maywand (farthest west in Kandahar province) and Helmand province even farther to the west.

Supply convoys travel down this road to get to the Coalition outposts in the western part of the district and in Helmand province. These convoys are run by private Afghan companies that hire armed guards to ride shotgun on their vehicles. These guards, and the drivers they are meant to protect, provide the FOB Wilson UMS with a large proportion of its patients. The Taliban attack these convoys almost daily.

Today there were attacks on two separate convoys. Two critically injured men were sent in from the first attack. One of them had received a large piece of shrapnel in his lower left abdomen and arrived with very low blood pressure. A part of his bowel was hanging out of his body. He was barely responsive. A quick physical exam assisted by ultrasound confirmed that he had no other injuries and that there was serious bleeding in his abdomen. It is impossible to control this bleeding in the field, so it was urgent to get him evacuated to a surgical facility. My priorities were to get IV lines started to bring his blood pressure up with fluids, but only a little. If a bleeding site cannot be controlled by direct pressure, as is the case in the chest and abdomen, it is unwise to bring the blood pressure up higher than is needed for a safe transfer. We achieved this quickly; the medics here are slick at starting IVs.

Although this man was now stable in the cardiovascular sense (his blood pressure was okay), his diminished level of consciousness made it essential that I protect his airway before the medevac took place. The danger was that he would choke on his tongue or vomit into his lungs during the helicopter ride.

His intubation was delayed, however, by the arrival of the second patient. This man was alert and oriented and had normal vital signs, but he had been shot in the middle of his throat. The bullet had travelled down and to the right, exiting to the right side of his right shoulder blade. Ultrasound examination showed that there was bleeding into his chest cavity, so we prepared to place a chest tube. But it was the neck injury that needed attention first.

The danger was that one of the arteries in that part of the body had been partially cut. If this artery ruptures, a hematoma (large blood collection) can accumulate so quickly that the patient’s airway is crushed. When this occurs, it is no longer possible to pass a tube from the mouth into the lungs. As much as I wanted to secure the airway of the other patient expeditiously, I intubated this man first. Once he was under general anaesthesia, I was able to put the chest tube in very easily. This drained off the blood that had been accumulating in his chest cavity, preventing it from collapsing his lung.

I then returned to the first patient. Dominic the Medic had cleaned off the extruded bowel and replaced it in the man’s abdomen, then bandaged the wound. The patient’s level of consciousness was still diminished, so I proceeded with the intubation I had planned for him.

We had just gotten these two patients loaded onto the medevac helicopter when another casualty reached us from the second convoy attack. He also had a gunshot wound to the chest, and ultrasound confirmed blood and air in his chest cavity. He also got a chest tube. We called for yet another helicopter, and he was away in less than twenty minutes.

My medic team performed admirably throughout this period, and I felt as well surrounded as I am in the Level 1 trauma centres I have practised in back home. This was all the more impressive because this group had not been led by an emergency specialist prior to my arrival. They had to work more quickly and more intricately than before. Master Corporal Guay, for instance, had seen chest tubes placed during her few weeks at the FOB, but never under sterile technique. She immediately understood that this additional step would help to achieve the best outcome and figured out how to assist me with the procedure.

Later in the day I called Lieutenant Colonel Ron Wojtyk, the highest-ranking doctor of the task force, to asKAFter my patients. Ron, who is a visionary physician, had been a student of mine on a couple of emergency ultrasound courses before we deployed. He is quite senior to me in rank, but we are close in age and careers and we have become good friends. He informed me that my patients had fared well. Two of them had required emergency surgery, but both were now on a regular ward. They will all be going home in a week or so.

Ron then asked me what I thought of the day. I replied that it had been very satisfying. Again, lots of blood and lots of life-saving procedures, everybody alive and doing well at the end. It had been pure emergency medicine, and it doesn’t get any better than that.

JUNE 12 | Political Science Lesson (or, Not Much Going On)

To understand what is going on in Afghanistan, it is necessary to understand another country: Pakistan. The fates of both nations are inextricably linked.

Let’s start with a bit of geography, since politics so often derives from the land. I mentioned earlier that the Taliban are almost exclusively drawn from the Pashtun tribe of southern Afghanistan. But while it is true that most Afghans living in the south are Pashtuns, it is not true that most Pashtuns are Afghans. The legacy of colonialism here, as in so many places, has split a tribe between two countries.

All through the 1800s, Great Britain and Russia vied for influence in Central Asia (roughly present-day Iran, Afghanistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan and Pakistan). Occasionally they would invade, but more often they would try to establish alliances with local warlords through bribes of money, weapons or other inducements. This went back and forth in what came to be called “the Great Game.”

Warlords controlled one main city and the surrounding countryside. By the mid-1800s, the territory that would be roughly recognized as present-day Afghanistan came to be controlled by a single king-like entity, an emir. The British wanted to demarcate where Afghanistan ended and where their own colony of India began. Sir Mortimer Durand, at the time the foreign secretary of the British Indian government, mapped out the line that to this day is the border between the two countries. The only difference is that, in 1947, the Muslim part of India became Pakistan. So the Durand Line is now the border between Afghanistan and Pakistan. The problem is that the Durand Line followed physical features such as rivers or watersheds. In doing so, it divided the Pashtun tribe.

Afghanistan’s government, long dominated by Pashtuns, has never recognized the Durand Line. The tribe longs to be reunited in a “Greater Pashtunistan.” One could argue that Pashtunistan already exists. Pakistan has never exerted much influence or control over those of its provinces that lie next to Afghanistan. The border is a nonentity, and Pashtuns pass effortlessly in both directions.

This state of affairs served Pakistan and the United States well during the Russian occupation of Afghanistan. The Pashtun provinces of Pakistan were training grounds, rest areas and logistics bases for the mujahedeen fighters who were being armed by the CIA. The situation in Afghanistan today stems in large part from the different goals held by America and Pakistan in the war against the Russians.

The Americans wanted the Russians to hemorrhage blood and treasure. This was done out of revenge for their losses in Vietnam. Russia invaded Afghanistan less than five years after the Vietnam War had ended. America’s sixty thousand dead, many of them killed by weapons supplied by Russia, still constituted a raw wound in the American psyche. It was only much later, when the Afghans began to inflict serious damage on the Red Army, that the Americans began to think of this as a proxy war they could win.

When the war was won and the last Russian soldier had left, the Americans lost interest in Afghanistan. They had won a skirmish in the Cold War. That war was ongoing, and their attention turned to where they thought the next battles would take place. No one was predicting that within two years the stresses caused by Russia’s defeat here would provoke the disintegration of the Soviet Union.

Pakistan’s goals were radically different. With CIA money, Pakistan was training and advising the Afghans as they prosecuted all-out war against the Russians. As Muslims, most Pakistanis had no love for the atheist communists and it suited them to help their co-religionists. The war raging to the west also served to better prepare them to confront the far more serious enemy they faced to the east: India.

Since India and Pakistan’s independence, there have been three full-blown wars and countless skirmishes between these two countries. But whereas India sees Pakistan as a constant irritant, Pakistan sees India as an existential threat. A glance at the map explains why: India is gigantic. You may think of it as a Third World nation, but that would be inaccurate. It is the regional superpower. Its economy dwarfs that of Pakistan, it has five times Pakistan’s population and its army is much larger and better equipped.

The Pakistani army, on its best day, could never do more than conduct raids into Indian territory. The Indian army, on the other hand, has a large number of tanks and troops massed across the border at Pakistan’s midpoint. As the bomber flies or the tank drives, it is two-to three-hundred kilometres to the Afghan border. If Indian troops capture that central part of Pakistan, they will cut the country in half. The capital, Islamabad, would be cut off from the port of Karachi, the economic hub of the country. Pakistan would disintegrate.

This equation changed in 1997 when both countries became nuclear-armed (each detonated five warheads that year), but old habits die hard. Pakistan’s fear of invasion remains the same, even though it can now inflict such damage on India that New Delhi would never order such an attack.

This fear dictated Pakistan’s goal during the Afghans’ war against the Russians and in the civil war that followed: to establish a friendly government in Afghanistan that would give Pakistan “strategic depth.” In theory, Afghanistan would serve as a backstop for Pakistan, allowing the Pakistani army to continue to retreat westward in the face of the Indian onslaught. This would give the Pakistani army time to regroup and counterattack while leaving the Indian army at the end of a long and vulnerable supply line.

Although this has been advocated by the Pakistani military for decades, it is a lunatic concept. Afghanistan has minimal transportation infrastructure, and while the Pashtuns on either side of the border have an affinity for each other, it does not follow that the Afghans would welcome the retreating Pakistani army with open arms. The best the Pakistani army could hope for would be for a few of its members to hide in the caves of western Afghanistan. For Pakistan’s generals to cling to “strategic depth” as a matter of policy shows how detached from reality they are.

Whatever the logic of the matter (or lack thereof), that was the motivation for Pakistan’s support of the anti-Soviet resistance in Afghanistan. There is a further complication: “Pakistan” cannot be taken to mean a nation-state in the sense that Canadians use the term. Pakistan is not one country; it is three countries.

One Pakistan is run by the civilian government. It has institutions that look like our parties, prime minister and parliament. Although influenced by the Islamic character of most of its citizens, it is nonetheless nominally secular. Think of the United States before Kennedy was elected president. It was a huge deal, in 1960, for a Catholic to even run for this office, much less win it. And yet, the unbroken string of Protestant presidents elected before then would have described their country as having a separation between church and state. Religion was not an official government policy, but it informed people’s decisions. Pakistan’s civilian governments would identify with this.

Another Pakistan is run by the army. This goes beyond the regular military coups that have overthrown the civilian government. Even when it is not in power, the Pakistani army exists as a national entity unto itself. It has its own economic base: it runs thriving import-export businesses in a wide range of fields; it owns hotels and shopping malls; it runs several factories. Even more astoundingly, it conducts its own foreign policy.

The most remarkable example of this occurred in the spring of 1999. Pervez Musharraf, then the chief of the army’s land forces, decided to attack India at a place called Kargil. Only a few thousand Pakistani soldiers were involved, so this was never going to be more than a raid that penetrated a few kilometres into Indian territory. Nonetheless, it was a blatant act of war, and it could have provoked India to retaliate and perhaps have led to a nuclear exchange. Musharraf decided to do this on his own. He did not even discuss it with the then prime minister, Nawaz Sharif,* much less any other members of the civilian government.

In Canada, our country has an army. It is beholden to our elected civilian leaders. In Pakistan, as in a lot of developing-world nations, the army has a country; the elected civilians serve only as long as the army allows them to.

Finally, there is a third Pakistan. This one is run by the spies. Their organization is called the Inter Services Intelligence, or ISI. Think of this as a combination of the CIA, the FBI and military intelligence in the United States.

The ISI is a power unto itself. The civilian government (when there is one) is not even allowed to know what the ISI’s budget is. Like the army, the ISI runs a number of businesses to support its activities. And it is even more aggressive in the foreign policy arena than the army is.

During the Russian occupation of Afghanistan, the ISI controlled the CIA money that flowed to the Afghan resistance. Being largely run by Islamic fundamentalists, the ISI favoured those resistance groups who shared their theological beliefs.

This continued during the civil war that followed the Russian withdrawal and when the Taliban conquered the country. Despite the Taliban’s behaviour while in power, Pakistan did not sever its links with the Taliban until after 9/11. Even after that, the ISI continued to arm, train and otherwise support the Taliban for many years, even as the Coalition fought them in Afghanistan.

Pakistan is the piece of the puzzle that George W. Bush never addressed. Since Afghanistan is landlocked, Coalition forces have to ship most of their heavy supplies via Pakistani airports and harbours. In exchange for this access, the Bush White House ignored the overwhelming evidence that a proportion of the Pakistani military and intelligence establishments were helping the Coalition’s enemies. Instead, it kept praising Musharraf as a vigorous leader in the war against the Taliban. Musharraf would thank Bush for the compliment . . . and continue to pretend that his country was not playing both sides of the fence.

Until Pakistan is cajoled/encouraged/pressured/assisted to do its part in bringing responsible government to this area, our mission here will not have succeeded.

Addendum: The best review of the situation in Pakistan today is Descent into Chaos, a book by Ahmed Rashid, a Pakistani journalist who has covered Central Asia for two decades.* Rashid is critical of all sides in this mess. The difference, which he recognizes, is that his criticisms of the Coalition side will stimulate debate, which has a chance of leading to policy changes. His criticisms of the Taliban, on the other hand, have only led to death threats against him.

JUNE 13 | Combat Psychology, Combat Psychologist

The CF tries hard to identify those who will not be able to withstand the rigours of combat and to weed them out ahead of time. For the soldiers who make it into combat, the CF does everything it can to support them psychologically. Here’s an illustration of how far we go to make this happen.

For the past four days we have been joined in the camp by a social worker, Captain Josiane Giroux, who is posted to KAF. She has a master’s degree in counselling and does a lot of the critical-incident debriefing sessions for our troops. She will spend a week at our FOB, counselling any soldier who feels the need to talk. Her timing could not have been better. She arrived the day of the ramp ceremony for Private Alexandre Peloquin, twenty-four hours before Bravo Company came back to the FOB.

A number of soldiers, including some commanders, have come to see her. This is good to see. If our troops are no longer worried about discussing their anxieties, it means that the stigma attached to these feelings is nearly gone. This bodes well for the ongoing mental health of Canadian soldiers.

It is appropriate and indeed necessary to be tough and unemotional when the bullets are flying. To be otherwise would put oneself and one’s comrades at risk. After the shooting is over, many people will benefit from being able to vent their feelings. Often soldiers will seek out friends or trusted leaders to do so. The CF also provides well-trained mental health professionals to those who want to avail themselves of that service.

Things are markedly different than they were even ten years ago. It used to be that soldiers who admitted they were scared were seen as weaklings. Discussion of one’s fears was subtly (and sometimes not so subtly) discouraged. Like all pendulums, this can go too far the other way. One of the men on the FOB asked to see Captain Giroux, saying that he had been ordered to talk about his feelings. He had been involved with our KIA—killed in action—and someone in the chain of command thought he was doing the right thing by shoving this soldier on the social worker. I am sure the commander’s heart was in the right place, but his actions were overzealous. Some people come through a combat experience with no emotional damage whatsoever, and others are not ready to talk about their feelings. Both types of individuals should be left alone until they feel the need for help.

Captain Giroux spent some time with me discussing the relaxation and visualization techniques she uses to coax the emotionally wounded back to health. She has had good success with these techniques, but she worries about the few individuals who have not responded. I can’t blame her. When my treatments fail, my patient’s suffering has ended; when her treatments fail, her patient’s suffering is only beginning.

JUNE 14 | EOD: Explosive Ordnance Disposal

Another day of heavy fighting all around the FOB.

The Taliban managed to pull off three attacks right after we had finished breakfast, one to the west and two to the east of our position. Two of these were ambushes of civilian convoys, and one was an attack on a police substation. ANA units and our own quick reaction force headed out to engage the enemy.

The first reports of casualties came in one hour later. There was one patient with a gunshot wound from the fighting to the west, and possibly other casualties to the east. We got ourselves revved up and ready to receive them. This involved calling all the medically trained personnel on the camp, especially the combat medics who are assigned to each platoon, to join us in the UMS. They are trained to the same level as Dominic, the Bison medic, so they are superb.

The other resources available to us in a MasCal event are the soldiers who have taken a course called Tactical Combat Casualty Care, or TCCC. They can perform basic emergency procedures and, most importantly, can help us control life-threatening bleeding. They do this with a number of different kinds of sophisticated bandages, modern tourniquets and an ingenious substance called Combat Gauze, a dressing impregnated with a substance that accelerates the formation of blood clots. Using this dressing to pack a large open wound greatly decreases the speed with which the patient loses blood. Blast injuries can also give you a tremendous amount of blood loss from diffuse oozing. Combat Gauze is invaluable in these situations.

Combat Gauze has largely replaced its predecessor, Quick Clot. This was a substance we used liberally during Roto 4. It produced an exothermic reaction when it came in contact with blood or any other source of moisture. When you sprinkled it into a wound, it got so hot it cooked the torn flesh. This sealed off the bleeding vessels.

Sounds like a wonder drug, eh? It turns out to be, like so many things doctors have tried over the centuries, a beautiful theory that gets killed by an ugly fact. Since Quick Clot would burn itself into the tissues, it was often necessary to “debride” (cut away) more tissue than would otherwise have been the case. Combat Gauze has the advantages of Quick Clot without the drawbacks.

We also put the word out for two of the senior non-commissioned officers (NCOs) to join us. These two men handle the flow of information from me to the KAF Tactical Operation Centre, or TOC, which marshalls the medevac choppers and provides a summary of the incoming patients’ injuries to the receiving physicians. There is no physician-to-physician contact.

This may strike those familiar with Canadian medicine as aberrant, but in this setting it works well. Battlefield injuries, though devastating to the victim, are straightforward to manage. There’s a hole in the front and a hole in the back? The part that has to be fixed is in between the two holes. The leg is ripped off? Try to save as much of it as you can. The thorough description of the patient’s history and physical exam that is so crucial in civilian emergency medicine is not necessary here. In a MasCal, it would be an inappropriate use of my time—I have to focus on treating and stabilizing patients.