We all want to be special to someone or several someones. We all want to be valued and valuable. This could look like joining the elite club of Academy Award winners, Olympic athletes, or Nobel Prize winners. There are formal inner rings with official membership, and there are many more informal inner rings. We all aspire to belong to prestigious inner rings, perhaps not just for authority and respect but for new ways to participate and contribute. This desire is so powerful that we’re rarely satisfied with the rings we already inhabit. We simply differ on the inner rings we aspire to join and what we’re willing to do for admission.

I’ve not yet discovered a single spiritual tradition without some sort of inner-ring organization. The most beautiful description I’ve heard was by my friend and Tibetan Buddhist teacher Lama Surya Das. He explained that in his tradition these rings can be mapped on a mandala, a circular figure or diagram that represents wholeness and the universe with material and nonmaterial parts. As one travels deeper into the community, it can be described as a journey from the outer part to the inner part and then to the secret or subtler part. The journey from the periphery into the inner rings can be described in this way:1

Students

Joining Members

Practitioners

Lay Vowed

Acolyte or Neophyte Vowed

Monastic Vowed

Mystics and Sages

The progression may look like a hierarchy, but it’s not. Every part of the mandala is the center, and every part is connected to every other part. The heart center, or the mandala’s center, “is bigger than the space outside.” In other words, for those who enter the smallest inner ring, they’ll find that in the center there is oneness where all are linked. New members are concerned about what they can get out of the tradition. The mystics and sages in the center are concerned for all beings in the universe.

Almost everyone aspires to join inner rings (if you are normal). When I lived in New York City as a young documentary filmmaker, I aspired to join an inner ring of professional documentary filmmakers. It was an informal ring that socialized at particular locations in the city, meeting up at filmmaking events including certain workshops, festivals, and panels. But when I succeeded in joining this group, I realized that the ring I really wanted to join was the ring of PBS filmmakers, then a ring of filmmakers whose work was funded by a particular list of funders, then a ring of international award-winning filmmakers, then a ring of filmmakers whose work was distributed internationally on television and via other media, then the ring of filmmakers who won an Academy Award.

The members of each progressive ring, I believed, could teach me more, have better wisdom, have access to more power, better understand how to accomplish goals, and maybe even have more fun. Obviously this was not always true. These were informal rings. There were no group presidents, selection committees, membership cards, or annual meetings. I wanted to continue into these inner rings all the same. For better or worse, I saw the progression as a reflection of my own growth, even as important for my continued advancement. I wanted evidence that I was becoming a more established filmmaker. Inclusion in these informal inner rings was one way to evaluate my success at the time.

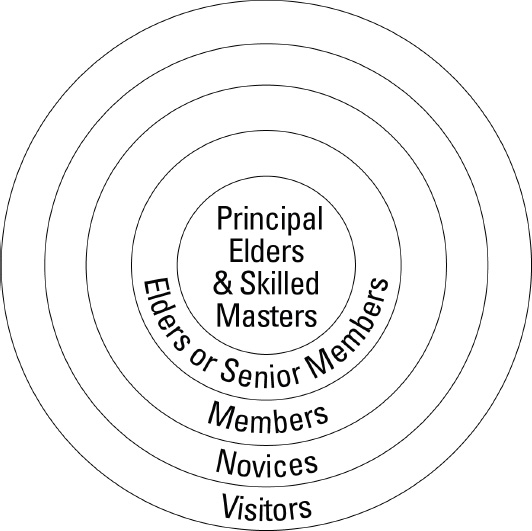

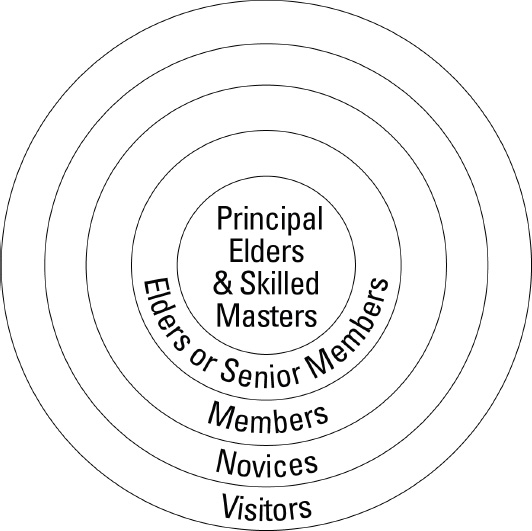

The endless striving for the next ring can be a dangerous trap. In mature and formal communities, there’s a much more satisfying and healthy way to relate to inner rings. Mature and strong communities create different levels of inner rings that members can enter (not to be superior snobs but to serve differently). At each level, members gain some benefits related to their maturation or formation. The benefits could include new access, knowledge, authority, acknowledgment, or respect. Groups have many different names for these inner rings. A typical progression will look something like this, with different labels:

Visitors

Novices

Members

Elders or senior members

Principal elders and skilled masters

In our dinner series community, the rings are labeled this way:

Information seekers (visitors)

Dinner guests (novices)

Volunteers (members)

Dinner leaders (senior members)

Leader coordinators (elders)

Hosts (principal elders)

A community can decide what makes an appropriate inner ring and how many there should be. Obviously there’s a point at which it becomes pointless and silly: imagine an organization with only ten members and seven inner rings! Even small organizations, however, will see at least a few informal rings form.

It’s not important that each member pursue inner rings. Not all members in our dinner series aspired to be a dinner leader. It’s perfectly fine for a member to find a preferred level and remain there. Success in life or in the community should never be defined only by progression into increasingly exclusive rings.

Strong communities offer a journey (progression) into successive inner rings. While some members may choose to stay at a particular level, mature communities provide opportunities to progress in their series of inner rings. In the best examples, the progression reflects a journey of growth or maturation.

This is true even if the community is based on a shared interest or skill like bicycling, gaming, or dinner parties. One type of growth can simply be a level of skill or competitive achievement (for example, bicycle racing, kite making, or boat building). Evaluating improving skill is one way to evaluate the journey across levels. But skill improvement (e.g., making higher-flying kites) is a superficial measure that may usefully organize a group, but not a community.

The most powerful journey reflects “maturation” of growing concern for others. On this journey, we follow a path of progression during which concern for ourselves diminishes while concern for the others—an ever-widening circle beyond ourselves—grows. The irony is that the smaller and the more exclusive the ring to which we belong, the broader our concern for others.

Visitor: May have concern for no one else, seeks novelty or fun experiences.

Novice: Concern for individual self, seeks personal achievement and legitimacy.

Member: Concern for one’s peer group, seeks success and respect for the group.

Elder: Concern for everyone in the tribe everywhere, seeks the whole tribe’s success and respect.

Principal elder: Concern for the whole world, seeks to help the worldwide tribe fit within and serve the dynamic world.

Not all communities have principal elders with a whole-world perspective for their tribe, but the most respected communities often do. Again, consider our dinner community as an example with this idea in mind. The descriptions below articulate the minimum maturation required within each level. If individuals never achieve a level’s minimum, either they won’t advance or they’ll make very poor advanced members. This example highlights how skills alone are not enough to make the next inner ring appropriate for someone’s journey.

Information seekers (visitors): Not concerned yet for anyone else, seeking knowledge about the series.

Dinner guests (novices): Concerned for self to have a good experience.

Volunteers (members): Concerned that guests have a good experience and perhaps learn skills themselves.

Dinner leaders (senior members): Concerned that volunteers and guests have a valuable experience.

Leader coordinators (elders): Concerned that all the leaders, their teams, and guests create something valuable and fun.

Hosts (principal elders): Concerned that all involved get value and the series enriches the community it lives within and makes a difference in the future.

The 1984 film The Karate Kid presents a good example of how crossing inner rings is a journey into maturation. The film tells the story of a boy named Daniel who’s seeking a karate master with whom to study. Daniel starts out as a visitor to the karate tradition: he wants to learn to defend himself. The gatekeeper who can teach the martial art controls the entry into the inner ring of the tradition. Daniel learns about two apparent skilled masters, the calm Kesuke Miyagi and the violent and aggressive John Kreese. After Daniel’s pleading, Miyagi agrees to teach him. The training assignments are strange and seemingly pointless: Miyagi instructs Daniel to do menial tasks all day, such as painting, sanding, and washing. Only after Daniel completes several days of boring and painful assignments is the wisdom behind the training revealed. Daniel, a novice, is encouraged to do the behavior before understanding and believing in their value or philosophy.

Then the training philosophy is revealed and after he has developed karate muscle memory through the tasks, Daniel becomes an insider. Miyagi gives him a headband as a token of his new status. When Daniel completes his training, Miyagi gives him a competition uniform with a bonsai tree depicted on the back. It’s a token of Daniel’s transition from student to competitor given by his senior elder. He’ll take it with him through the upcoming challenges.

In the third act, Daniel enters a karate competition. He’s asked what color belt rank he has. This question is designed to determine if he’s really an elder-level insider. Miyagi, a skilled master, assures the tournament official that Daniel is a black belt (elder). He can approve Daniel’s authenticity as a gatekeeper in the karate community. Though other competitors have much more experience, Daniel reaches the final match. Throughout, he is the only competitor wearing a Japanese rising sun headband, the token from his training.

In the semifinal, when it appears that Daniel could win, Kreese instructs his competing students to “show no mercy” and to hurt Daniel. They do. Then, even with a hurt leg, Daniel wins the championship match with a flying crane kick. He’s lifted up by the crowd and recognized by all as a mature elder. We see that he’s grown and can now defend himself and presumably others from threats that, before his journey, would have overwhelmed him.

The most interesting part is how the two karate instructors are presented. We can tell that Miyagi is the real principal elder because Kreese is interested only in the welfare, success, and recognition of his own group; he’s clearly not concerned with the welfare of strangers. This is revealed in the first act when he refuses to ask his students to respect Daniel. Nor does he care for the karate tribe in general. We know this because he tells his students to hurt Daniel in competition. We see that Kreese is really an immature member pretending to be a principal. He has skills but not the maturity that makes a true principal elder.

Miyagi, on the other hand, defends Daniel when he’s a stranger and cares for all karate competitors. This is made explicit in the sequel film when Miyagi protects one of Kreese’s students from Kreese’s own abuse. Both we, the audience, and the karate competitors can see that Miyagi is an authentic elder not only because of his skill but also because of his broad concern, even generosity. We also have a sense that Daniel has found the right path to follow. If Daniel continues to study with Miyagi, he will also mature into a true principal with far more internal growth than just physical growth.

Even a principal elder never achieves “all” knowledge. Miyagi may say that he has learned from Daniel as Daniel has learned from him; Kreese, of course, wouldn’t admit that a student could teach him anything. So a true principal can learn from novices, members, and others as much as others learn from her. What the principal learns will be very different from what the novices learn, and how the novices teach will be very different from how the principal teach.

In creating inner ring journeys, we offer opportunities to teach. As we progress into ever more exclusive inner rings, we want new ways to express both our own and our community’s values. This could consist of additional opportunities to practice an activity, develop a tradition, or teach others. But because the best inner-ring journeys teach us to care for increasingly wider circles of people, advanced inner rings must give members an opportunity to teach others—to share not just skills but values and beliefs that help us mature internally as people. On our journey, we want to be taught, and we also want to teach. This is why creating opportunities to both mentor and be mentored are powerful.

For a healthy and growing community, it must be clear how one crosses into inner rings. The journey may be difficult, whether naturally or by design. This difficulty is what keeps the inner rings exclusive. But the path must be both known and available for those who are willing to commit and learn. For example, in our dinner community advancement required a commitment to scheduling time, planning a meal, recruiting volunteers, funding an evening, and hosting an event for four hours. When a volunteer could do this, then that volunteer would become a fully recognized dinner leader.

Whatever the path is, it should help foster the member’s maturity and include an evaluation that assesses this maturity. If you choose, this can mean informal teaching by more senior members or a formal evaluation from leaders. Some new members will have skills and maturity that are more advanced than that of their peers. Those members should cross into inner rings more quickly, in a way that reflects their journey. As long as each ring’s values are honored, members should be allowed to progress at their own pace. If all members are forced to progress at the exact same pace, then time is honored more than maturation. This is an unattractive and uninspiring path. For the right reasons, talented and skilled members will get frustrated and likely leave. This can be particularly important in a corporate setting. Talented people want to know how they can progress in the company or their own field. If it’s unclear how they can do this in your organization, then they’ll look for options elsewhere.

As I mentioned in the preface, C. S. Lewis explained the attraction and danger of pursuing an inner ring in his 1944 speech, “The Inner Ring.” The trap of the inner ring is the spiraling cycle that pulls us from one ring to the next; as soon as we achieve one, we inevitably long for the next, even more exclusive (and thus more attractive) ring beyond it.

The desire to be inside the invisible line illustrates this rule. As long as you are governed by that desire you will never get what you want. You are trying to peel an onion: if you succeed there will be nothing left. Until you conquer the fear of being an outsider, an outsider you will remain.2

For example, admission into an elite school is an invitation to join an inner ring. But when we arrive at the school, we discover that there’s a group of cool kids who have formed a better, and more exclusive, inner ring. If we enter that ring, we discover yet another, more exclusive ring of student organization leaders, presidential scholars, or sports stars. Beyond that ring, we discover a still more exclusive ring of accomplished students. There we discover that there’s an inner ring of society presidents and alumni, and so on: the inner rings go on forever. Even if we become president of our own country, we’ll discover that there’s a smaller inner ring of world leaders who have won the Nobel Peace Prize. Because an even more inner ring will always exist, our aspirations can never be satisfied. Without awareness and conscious effort on our part, we will fall into the self-created trap of striving to be somewhere that we are not.

My friend Patricia shared with me that when she entered law school, she heard how prestigious it was to work on the law review. In fact, the current US president served on the same publication! It sounded so special that she immediately wanted to join that exclusive group. Then, over the next weeks, she considered what she wanted to learn in law school and what she wanted to do after law school. She wanted to work on international justice. The hours on the law review wouldn’t really help her do that as much as other opportunities. It wasn’t a good investment of her time except that it might result in becoming an elite insider. She told me how hard it was to let go of the draw of the law review inner ring and return to pursuing what inspires her.

Lewis says that there’s nothing wrong with inner rings in and of themselves. They’re simply structures filled with people longing to be connected. What he warns us against is our insatiable desire to pursue new rings. Once we recognize this desire, we can choose to give it up.

There is a way to escape the inner ring trap. Lewis recommends that we participate in some activity that we enjoy and do it often. His example is playing music. We can then invite others who would like to join us in playing music. As we regularly gather to do this, we’ll form a specific kind of relationship that saves us from longing to be elsewhere. That relationship is friendship. This is the real foundation for a community. Remember our definition of community? A community is a group of individuals who share mutual concern for each other’s welfare. When we form a community that grows friendship, we create what we seek, friends who care about the welfare of one another. To outsiders, it may look like an exclusive inner ring. We’ll know, however, that it’s open to anyone who shares our values, even if this is simply valuing friends with whom we play music.

Avoiding the inner ring trap is why our communities must offer clear paths to personal growth for those who share our values. This access prevents us from creating meaningless inner rings that remain unattainable (and pointless). If we consciously create inner rings with our communities, and build them based on our core values, and invite anyone with those same values to enter, we create a forum for friendship. For example, when we started our dinner series, we sent out invitations by e-mail across the campus and beyond. Anyone was welcome to join us as long as they reserved an available seat early enough. Within the first four months, it became clear who our regulars were. They helped set up, and they knew where our supplies were kept. They helped with the flow of the long evening. Eventually some regulars began leading dinners. We called them dinner leaders. A few years in, the series grew so large that our friend Arjan began coordinating and Sam handled administration.

Graduate and undergraduate students, faculty members, administrators, visiting lecturers, theologians, medical doctors, journalists, human rights activists, ethicists, poets, and rocket scientists joined us. I learned how rare it was for students to sit down for three or more hours, connecting with others, uninterrupted and without an agenda. For many, the dinners became a highlight of their university experience. A funny thing happened in the second year: two regulars, Courtney and Bjorn, told me that when strangers discovered that they had been to “the dinners on Prospect Street,” the strangers wanted to know how to get invited, how to get inside what of course looked like our inner ring. Several of us laughed about this. We knew that we had worked hard to create a system for anyone to join, as long as they RSVP’d on our public website! We learned that this simple commitment to share dinner created something that indeed looked like an exclusive inner ring to others. What we really had was a community of friends always ready to welcome more. If you want to learn more about our dinner series community, I share more as an example in Appendix B.

A community may have many different inner rings. Some may lead naturally into other rings. For example, airline pilots may have a more exclusive ring of airline captains. Within that ring, there may be another for airline captains who fly international routes. Other inner rings may not have any more exclusive rings. For example, my wife is in a community of Cambodian women professionals in Oakland. There’s really only one ring among those particular women. But an increase in the group’s size might inspire or require, down the road, the creation of more inner rings. Most mature communities have at least one ring, if not a hierarchy of rings, that I call the diaconate.3 Like temple and rituals, the term diaconate comes from spiritual communities, but can be applied to all kinds of communities.

The diaconate are people who have more authority in the community than other members. The diaconate should also have more wisdom about the community, but that’s a best-case scenario. Their opinions are more valued than those of other members. The diaconate is always made up of members who are elders and leaders. The gatekeepers mentioned earlier are part of the diaconate. They obviously have more authority. In this age, it’s likely that your members will respect the diaconate and maintain its legitimacy because members believe that the leaders are or could be their friends. Members believe this because they understand that the diaconate embodies the community values that members hold dear.

Such authority can be either helpful or abusive. We have all seen both. Danger usually arises when leaders no longer prioritize enriching members but think of themselves as infallible and forbid any questioning of their moral rightness. The diaconate has informal or formal authority in three key areas:

Protecting the boundary: They have the authority to exclude or reject someone from the community, ideally for lacking values consistent with the community.

Officiating at rituals: Their attendance makes rituals either important or more important. These can include formal rites of passage like initiations or informal celebratory feasts.

Teaching on community values: Their teachings on community values are more influential than those of other members.

Think about the communities you value. Whether there’s a formal structure or not, there are almost certainly people who have more authority than others in these three areas. There may be a single person who has responsibility for all three domains.

There are ways to identify the diaconate in a community. In an informal community, there may be no titles that would help an outsider identify the diaconate. There may even be pride in not appointing an official diaconate. But a mature and strong community always has a diaconate of some kind. Members may simply refer to these people as popular, respected, influential, or a “big deal.” You can usually identify the diaconate by answering these questions:

Who has the authority to reject someone from this community?

Who can bring someone into the community on his or her say-so?

Whose attendance makes a simple gathering more important or exciting?

Who are the members to whom the rest of the community will (almost) always listen?

Whose wisdom and insight is repeated within the community?

Whose approval will allow or expedite an idea that can change the community?

Problems arise if there’s no diaconate. Some communities pride themselves in giving all members, even visitors perhaps, an equal voice. Part of the idea is to ensure that no one can be left out or drowned out. It’s certainly true that good ideas and maturation can come from the least appreciated member. This is often how young communities start. But strict egalitarianism leads to problems as communities grow larger, do more, and mature in philosophy. At some point, ideas aren’t all equally valuable. For example, new members who are uninformed about the community history may make suggestions that have already been tried, and have failed, many times.

Without a diaconate, there’s no way to differentiate the contribution of an Einstein from that of a village bonehead or crackpot. If both are given equal consideration and time, then the overall community will grow upset. Moreover, visitors will be unable to tell if the community itself can distinguish between an Einstein and a crackpot. Rightfully, they’ll question the community values and fall away. A more dangerous possibility is that some members will advocate for values that conflict with those of the community, like violence, racism, or xenophobia. Without a diaconate, it’s impossible for the larger community to rightfully tell outsiders that these radicals don’t reflect the core community. The diaconate allows boundary enforcement so that radicals can be forced out, perhaps to create their own separate community.

It’s important to identify the diaconate, even an informal one, because new and maturing members will want to know what the values are and what’s permitted (that is, what allows one to stay in the group). Without a diaconate, visitors won’t know what (if anything) the community stands for. They won’t know if they’re listening to the uninformed village drunk or the moral backbone of the community. There’s a common cycle in the role of the diaconate, as informal authority moves to formal authority and then schism, which starts the cycle again in a new community. As a community matures, the need for a diaconate grows.

I mentioned my friend Amanda, a member of what I call the Lowell moms community. Over time, other mothers joined the small initial online community, and the larger membership brought more resources to serve one another. As new mothers joined, they were put into smaller cohorts (inner rings) so they could discuss the issues relevant to newborns. The membership has grown to thousands of mothers, including those who live beyond Lowell. The online platform-managing moms and forum managers became the formal diaconate even without an election or any of the current members aware how they got the authority. Amanda loves getting support from and providing support to the mothers in her cohort. She especially looks forward to seeing them offline in parks or visiting one another in their homes.

This past year, the online leaders decided that the community had grown too large and announced that they would end membership for anyone living outside Lowell. As you can imagine, this generated outrage from many members, some because they were getting rejected for their zip code and others because they would lose connection with friends for a seemingly trivial reason.

When Amanda told me about this, it sounded like a classic example where the leadership values something (proximity and management ease) and the membership values something different (participation and support). Amanda explained that the moms in her inner ring handled the tumult by moving their online connection to another social media platform. There, the Lowell moms leaders couldn’t impose rules (based on values) that Amanda’s ring didn’t like. Amanda’s ring had its own leadership. She didn’t call this a community schism, but it certainly looked like one to me.

Over time, values will almost invariably shift within a community: becoming more or less inclusive, choosing different priorities, or setting more ambitious goals. A values debate will begin, and a new informal diaconate will rise, advocating the new values. If the formal diaconate does not recognize the importance of the informal one, there will be a schism. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing. It can simply mean that subgroups with differing values are differentiating themselves. To prevent a schism, the diaconate must continually accommodate evolving values in the community. At some point, the new values may no longer fit in the original community. In this case, allowing some members to fall away may be the best choice.

Mature and strong communities give members opportunities to learn how to succeed in some way. That is, they help members grow in a way they would like to grow. The community supports growth and may explicitly lead this growth. This growth can be toward managing life as a whole or in some specific skill set or area of life.

For example, succeeding as a mom, entrepreneur, or bush pilot are all pursuits that communities can help us achieve. Strong communities teach members how to succeed in ways they cannot achieve on their own. The education comes from a body of knowledge and wisdom that members cannot access or manage on their own. So, in a strong community, members must know how to access the knowledge held by others. This can be informal (by hanging out with other members) or formal (with personal lessons, classes, or apprenticeships). If members no longer believe that the community can teach them how to succeed, their commitment will almost certainly fall away. Alternatively, if members have a sense that somehow membership can help them succeed, but they don’t understand how membership does this or how they can gain access to the wisdom, training, teachers, or mentors, then the community is weakened.

Members want to be taught by (and share time with) community elders. It’s important for elders to have opportunities both to teach and to learn. They’re resources for skills, internal health, and member-only knowledge. They can do this formally by hosting classes and retreats, or informally through unstructured conversation and private invitations. Imagine how differently visitors would experience that large urban church if elders invited new members to dinner, private walks, or classes on how the church creates its activism. The community would almost certainly have grown stronger.

As a New York filmmaker, I joined several documentary film groups. I went to social events, screenings, and panel presentations. I desperately wanted to grow as a filmmaker and have the wisdom that comes from the experience of being an international documentary filmmaker. I didn’t know what I didn’t know. But I did know that I could access this only by talking with veterans. You can imagine how disappointed I would have been if I had attended those events and the veterans were separated from the new filmmakers by a red rope, an all-access pass, and a knowing smirk. Fortunately, this is not how it happened. I had fantastic, life-changing conversations with filmmakers in lobbies, over dinner, and in theater lines.

Many of us share fairly universal goals. It’s possible that you have a community that just looks like a group of friends, or people who live near one another, or people who are related to each other. You may not think that the community you have or want to build is helping with any particular growth, success, or skill set development. You may be right: I haven’t met your group.

Consider that even if you didn’t necessarily gather originally to succeed at a skill set, there are some common goals in life that each member brought to your community, and your community is helping with them. Just about everyone wants to achieve some combination of the two goals below. In this context, they’re neither good nor bad. They’re simply the things that we worry about without even knowing why much of the time. If your community can help others handle one or more of these, it’s doing a great service indeed.

The first goal is to belong, to be welcomed somewhere and to connect with others. In 1943 Abraham Maslow wrote about a psychology theory on the hierarchy of needs. It’s widely used to understand people’s priorities. The theory places “love & belonging” in the middle of the hierarchy.4 In other words, after shelter, food, and safety, we need love and belonging, which are even more essential than esteem and self-actualization.

The psychologists Roy Baumeister and Mark Leary write: “The belongingness hypothesis is that human beings have a pervasive drive to form and maintain at least a minimum quantity of lasting, positive, and significant interpersonal relationships.” In other words, deep connections matter. Baumeister and Leary are not the first psychologists to say that belongingness is important, but they provide a nuance: that belongingness is created through “frequent interactions, plus persistent caring.”5

It may be that we want to belong so much that we’ll conform to a group simply to not stand out. As early as 1951 the research psychologist Solomon Asch put subjects in a group that conspired to misstate which drawn line appeared to match other lines in a set of three. Three out of four subjects conformed to the group and agreed to what they knew was wrong.6 Our longing to belong may be so strong that we’ll deny what we believe to be true.

The fear many of us felt in middle school when we knew we didn’t fit in and wondered if we ever would, never completely goes away for most of us. It may be built into our nature. I’ve gotten better at remembering that there are friends and family who support and cheer on my success. Despite that, the panic of not being good enough, of never being fully welcomed, of maybe being left out or seen as a fraud, still haunts me sometimes. Every day I want to know I fit in somewhere and I belong.

The second goal is to contribute to someone or something. Even in the early stage of psychology, one of the founding minds of the field, Alfred Adler, postulated that “the only individuals who can really meet and master the problems of life . . . are those who show in their striving a tendency to enrich everyone else.”7 It’s not just that many of us want to contribute. Contributing actually helps make us healthy and feel better.

Social research by Carolyn Schwartz in the past fifteen years indicates that “both helping others and receiving help were significant predictors of mental health . . . [and] giving help was a more important predictor of better reported mental health than receiving help.”8 A study by William Harbaugh at the University of Oregon put subjects in an fMRI machine while they decided how to split money between themselves and a local food bank. The research indicated that giving money away to charity activates the same pleasure centers of the brain that are also activated with exposure to cocaine, art, and attractive faces.9 Last, a survey by Baumeister and colleagues found that being a giver was positively related to experiencing meaningfulness, while being a taker diminished it.10

Over the years, I’ve spoken to thousands of people on five continents. Some are almost mythically successful and internationally famous. Some don’t have access to enough food. Wealth and geography don’t make a difference in wanting to make a difference. If your community helps members make a bigger or better difference, then it’s of tremendous value. This alone can be the binding value of many communities. The Byron Fellowship is a great example of a community formed explicitly to support members’ growth. For over ten years, the fellowship has brought together about twenty-five social change leaders from around the world and from widely varying fields for a weeklong workshop. In this experience, they learn to clarify their intentions, visions for the world, and their next steps during a secluded training intensive. After the week, fellows and “mentors” (instructors) participate in the ongoing fellowship community through self-organized events and projects, and by staying connected through an online community. Some fellows go on to volunteer in future trainings, and some return to lead parts of the weeklong workshop themselves.

The fellows go on to support one another as they create programs, develop their strategies, and take on fund-raising goals. The fellowship was founded by Mark Boyce and Gabriel Grant, who met at Indiana University, where they worked to grow education on sustainability far beyond the current offerings. They discovered a mutual passion for creating a living laboratory education experience. If and when the community no longer helps these members grow, make a difference, or know they fit in someplace, the membership will dissipate.

On one notable occasion, the Byron Fellowship failed painfully at enriching fellows as intended. The directors changed the schedule to involve more mentors. In the process, the plan’s bigger goals were never effectively shared with the mentors. The conversation in planning meetings and session evaluations revolved around keeping the schedule moving. As you can imagine, the programming was exhausting for all involved. The days felt like a race.

On the fifth day, the new fellows called an unscheduled community conversation where they expressed their own dissatisfaction. They (rightly) felt rushed. They didn’t feel confident that they had enough time to wrestle with the ideas presented or spend time building the relationships they longed for with one another. In short, they staged a strike and refused to continue with the schedule as planned. The good news is that the directors responded to these concerns, and the remaining days were rescheduled with the whole community in conversation. The event also prompted a deep reflection on what the program was trying to create during the week and an attempt to find what was obviously missing to achieve this.

I mention this experience because it’s a great example of leadership intending to provide more value to members but, in the end, doing the opposite. Gabriel did bring the fellows together, brought in instructors, prepared presentations, and scheduled field trips, but he actually failed to help them grow in the way they wanted to that week. If the program didn’t find its way in growing members, then its future would be in doubt. In this case Gabriel learned that more time was needed for reflection and relatedness among fellows. He changed the programming for the next cohort. This participation breakdown hasn’t happened again.

Communities offer external and internal growth. Almost all communities teach members some external skills. These can be as varied as hitchhiking across Africa, hosting dinner parties in America, or creating a more supportive neighborhood. The strongest communities also teach their members how to improve internal health, including emotional and mental growth that cannot be learned from books or videos.

My friend Alison is active in a meditation community in San Francisco. She began attending the evening sessions to learn how to meditate, including posture, breathing cadence, and scheduling practice time. She learned how to concentrate on her breath, to visualize her body full of white light, and to create healing meditations. The more she participated, the more her skills grew. But far more important was her personal growth—she began noticing her own desires and personal pride. The more she noticed these, the calmer and more content she felt. This gave her a new way to relate and connect to people. Such internal growth couldn’t be learned from a book. No one in the group is really impressed if she can now sit for hours at a time. Her internal changes, even if for moments, are the marker of true growth.

My friend Bjorn was a Boy Scout for many years. He learned a “ton” of technical skills, like tying knots, building fires, and treating wounds. Officially, he advanced based on his technical skills, for which he received merit badges. But Bjorn sees now that the true growth was learning to live out his values. He understands that the real value was supporting him to grow into a person who seeks to help others and remains physically strong, mentally awake, and morally committed. It’s no surprise to him that these are tenets delineated in the actual Boy Scout oath.

That real growth could never have been learned from Scout manuals. It grew over time, in relationship with Scout mentors and peers on a similar journey. In communities that you value, you may recognize skills you learned that anyone could get from a book or from much practice. I hope that you also recognize how communities have come to shape your character and maturity. That’s the value that makes a community so much richer than a collection of how-to manuals or a series of classes. Communities provide the time and space for that internal growth to happen among friends.

Strong communities teach esoteric knowledge. In mature communities, there are at least two kinds of “insider knowledge” that are only intended for or only truly understood by insiders. The first kind I call “data.” This is information that’s shared only with people who are determined to have the right intentions, integrity, and values. For example, I know of a professional women’s business group that shares salary information with other members so they can all understand how women are paid in their field. This is meant to help rising professional women negotiate appropriate pay when the time comes. I also know that my search and rescue friend Joel knows codes, meeting locations, and security protocols shared only with credentialed responders.

There’s also a more powerful kind of insider knowledge that indicates belonging. I call it “perception.” Perception comes when members learn either from explicit teaching or from experience that certain things are not as they appear to outsiders. Access to this esoteric perception is one of the jewels of membership (formal or informal). Remember The Karate Kid: karate for self-defense looked like fancy moves, aggression, and arrogance, but Daniel learned that true karate includes growth in humility, determination, discipline, and respect for the tradition and the elder who teaches it. Earlier, I explained how rituals may seem silly to outsiders but meaningful to insiders. It’s the esoteric knowledge that allows insiders to appreciate what outsiders cannot understand.

For example, my friend Alison participates in Weight Watchers. She knows that losing weight is not simply about eating less, as general outsiders may believe. Weight Watchers members know that achieving and maintaining a healthy weight includes working toward understanding and accepting self-worth, personal identity, feelings, expectations, and daily discipline. There are levels of emotional and mental health that must be addressed for long-term success.

Then there’s my friend Patricia, who’s part of a storytelling group in her city. The members know that the most powerful storytelling is vulnerable and creates strong and treasured connections. Storytellers need a private, safe, and respectful space to offer their full selves in order to move and inspire listeners. Outsiders think storytelling is about entertainment and deft wordcraft. They cannot understand why members would share vulnerable stories with people they don’t know.

My search and rescue dog handler friend Joel has told me that outsiders think his work is fun and exciting. Insiders know that how they and their dogs perform and the choices they make are critical for someone’s life when the calls come. There’s a lot of complication in considering how someone behaves when lost and in finding relevant information. Those searching feel enormous responsibility. The work is filled with seriousness and long, cold hours.

I’m hopeful you understand how important and sophisticated inner rings can be for a growing community. It is easy to make a meaningless ring series for member glorification. It is far more rewarding and rich to create rings that serve and help members grow. Who doesn’t want to share time with people who help us become who we aspire to be?