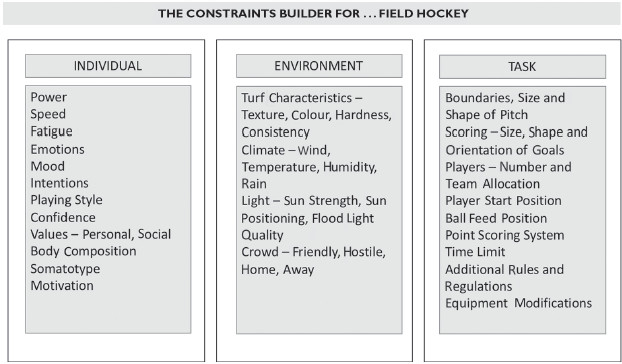

Figure 7.1 The constraint builder for field hockey.

7 A constraints-led approach to coaching field hockey

Introduction

The aim of this chapter is to demonstrate how the constraints-led approach can be applied in the context of international field hockey. Here, we draw on the experiences of Danny Newcombe, a co-author of the book who is applying a CLA in action within domestic and international field hockey contexts. Danny has been the assistant coach for a men’s national team for the past seven years. In addition, he has been the head coach of an English National League club for the past three years. First, we take the reader through the step-by-step process employed when designing and adapting practice environments in a field hockey context. Following this, we bring the constraints builder to life by discussing how a range of different constraints pertinent to this context can be employed. Next, we introduce the case study, which begins with an analysis of the current landscape of the national team, followed by implementing the GROW planning process as per Chapter 5. To simplify this section, where appropriate, it will be written from the first-person perspective of Danny. This activity sets the scene for the session design we unpack in the following sections. The session planner section then provides an example of the three linked practices and demonstrates how a coach might systematically design-in affordances to illustrate the application of the constrain to afford principle to the practice design process as well as varying the amount of representativeness and variability designed-in to their practice tasks. Finally, we provide a reflection from the coaching team on the practice environments delivered. The next section brings to life the three-step practice design process employed by Danny and his coaching teams.

Offer key affordances

Step one is to build an environment that provides learners with the opportunity to engage with the affordances related to the development focus (session intention). By using knowledge of the sport, it is the role of the coach to facilitate these opportunities for action through the manipulation of the task constraints. For example, if the intention of the session is to facilitate an improvement in a player’s ability to defend a large space, in a 1 vs 1 context, versus an opposition player who has the ability to attack at high speed, the environment must be designed to offer the player the opportunity to engage with related affordances. In this example, we would need to adapt the playing space, ensuring it is large enough to facilitate high-speed 1 vs 1 contests. In addition, the start positions of the attacker and defender would need to offer the attacking player a large space to attack. Furthermore, it is important to manage both the orientation and positioning of the players in relation to the goal, to ensure a situation where the defender organises their movement solutions in a representative manner.

Invite and encourage interaction with key affordances

Step 2 involves manipulating the constraints of the practice environment to encourage players to engage with the important affordances in an effective and efficient manner as they self-organise to solve the problem presented. For example, if the intention of the session is to encourage players to pass the ball earlier, it is essential that the practice environment not only provides the learners with opportunities to pass the ball early but also exaggerates (see Renshaw et al., 2015) and thus invites those actions. The manipulation of the task constraint to provide likely opportunities (but not 100% certain ones) can be achieved through creating numerical superiority by ensuring that the attacking team have at least one more player than the defence in a threatening attacking zone. While a traditional approach to this problem may be to simply create imbalanced teams (i.e. 4 vs 3, 3 vs 2, 2 vs 1), simply giving a team an advantage without requiring them to ‘earn it’ may lead to team co-ordination solutions that are less representative of the game and lead to a reduction in action fidelity (i.e. it looks like the real thing). Alternative approaches might be to reduce the number of defenders in the immediate area in ways that replicate those that happen in games. For example, in a game an overload might emerge due to a slow recovery run, a defender getting out of position, or perhaps a player being slow back to their feet after a minor injury. Coaches can therefore analyse games to identify the range of possible scenarios and then design them into their practice. For example, the coach could simulate the scenario of a defender being caught out of position after a change of possession by putting a temporal constraint on his or her ‘recovery’ run to give the attacking team a short time window to exploit their numerical superiority. Alternatively, the coach may require defenders to start in ‘poor’ positions where a numerical superiority can be exploited, if the attackers can attune to the available affordances (i.e. of an out of position defender). Developing representative scenarios such as these will afford the learner the correct context to attune to the available affordances and develop the perception–action couplings needed to pass the ball early more often. This environment manipulation should create a scenario where there is a ‘potential’ unmarked teammate in a threatening position at the moment that our player receives the ball providing an excellent opportunity for our learners to learn to look and perceive this affordance and pass the ball early. In addition, the introduction of task constraints, for example, in the form of a reward-based points system that invites learners to successfully passes the ball early when a ‘good’ affordance emerges during performance, may result in learners utilising the process of self-organisation to search for functional affordances. This process is a valuable tool in educating the attention of players as they search for opportunities to earn points within the reward structure.

Avoid the over-constraining trap

A key goal of Step 3 is to ensure that the designing-in of constraints does not lead to over constraining players and forcing them to make the desired response. While the desired actions are certainly encouraged and, indeed, invited by the coach’s design, it is important to re-emphasise that the action should not be forced and should emerge as the learner searches through the dynamically available affordances within the environmental and task constraints. A key point for performers is not just about learning to identify which affordance to use but also when and then how to use it. If the decision to act upon the emergence of an affordance comes from exploration of the landscape of affordance available in the environment rather than being forced by the task constraint to use one affordance, we can be more confident that functional, transferable perception–action synergies will emerge. Typical examples of over-constraining tasks include imposing rules such as, a ‘minimum of five passes’ prior to scoring or the ubiquitous ‘two touches only’ rule when in possession. An analogy from an urban design perspective to show how not to over-constrain would be that if an architect wanted to guide walkers around the park she may create a series of connected concrete paths surrounded by lawns to reach the gate on the opposite side of the park. This would invite walkers to walk on different paths, but it does not force them to take one path (or indeed any path as they could still walk on the grass) by giving them no option. Another example of an architect over-constraining the environment would be to force walkers to stay on the path by building high walls alongside it. In terms of judging the success of the design, with regards the desired outcome goal (i.e. they walk on the path most of the time; they pass the ball forward and early most of the time), then there is compelling evidence that the practice has being constrained in a functional way.

As can be seen from the previous discussion, the ability to learn to choose the most appropriate affordance at any one moment is a key part of learning to play games; however, as we began to highlight above, in their desire to focus practice to achieve one specific goal, there is often a temptation by coaches to over-constrain practice by introducing rules or restrictions to explicitly force desired actions (see Partington & Cushion, 2013). As highlighted, a ‘two touches only’ task constraint is a common way that coaches use to force their learners to pass the ball early. By introducing a ‘two touches’ rule, the coach prescribes intentionality, which, in turn, shapes perception and action (of attackers and defenders). In line with the comments above, removing the decision about ‘when’ to pass from the learner prevents him/her from learning to identify and attune to the key affordances related to ‘when’ to pass early or when best to hold onto the ball. Two-touch also prescribes the decision of where to stand for defenders, as once the first touch is made, the attacker has solved the problem for the defender. Over constraining task constraints stop the natural processes of self-organisation based on the perceived affordances in the environment. For example, at times it might be important to recognise when a pass should be made on the first or second touch and when it might be beneficial to dribble the ball to space or slow play down by keeping possession of the ball. So, the question for coaches is how they can promote effective engagement to achieve set session goals with the environment presented without forcing it.

Apply an understanding of co-adaptation

While not an actual step that Danny goes through in his session design, one key concept of ED he focusses upon when designing a session is that of co-adaptation. Co-adaptation (as we presented in Chapter 3) is the continuous interactions that emerge as athletes co-adapt to each other’s behaviours (i.e. team mates and opponents) while self-organising to achieve their goal-directed behaviour. The concept of co-adaptation can therefore be utilised by coaches as a powerful tool to facilitate an implicit behaviour change in the players. Within the performance environment, the opposition team are the provider of an unpredictable dynamic instability that players must self-organise against in order to be successful. This is in contrast to other more static constraints such as pitch dimensions and the goal directed behaviour. As the players co-adapt against this instability, they will be building dexterous perception–action synergies that are truly representative of the performance context. Therefore, a good way to create co-adaptation in a team is for the coach to manipulate the ‘opposition’ (in practice). In training, the concept is operationalised by:

Applying task constraints to the defending team to facilitate a behaviour change in the attacking team.

Applying task constraints to the attacking team to facilitate a behaviour change in the defending team.

An example of how to create co-adaptability to meet a session intention

As we mentioned above, the implementation of two-touch play in practice is a common solution for coaches who want their players to move the ball forward quickly. However, as we also highlighted in the previous section, this task constraint over-constrains both attackers and defenders. If the principle of co-adaptation is used to design a session with the intention of facilitating the attacking team to pass the ball early, coaches can use a range of constraints to influence the behaviour of the defending team. For example, rewarding the defending team by having them close down the attackers and increase the pressure on the attacking player in possession of the ball is one solution. Defenders can be encouraged to close down the ball carrier by awarding them points based on how quickly they ‘engage’ the ball carrier. For example, if the coach counts down from five to one, the number on which they ‘engage’ the ball carrier is the number of points they are awarded. The winning team is the one who score the most points at the end of the game. An alternative constraint would be to provide the defending team with an opportunity to win an additional defending player for their team if they can consistently put pressure on the ball within a set time frame over a series of possessions. The consequences of placing these task constraints on the defence will be a resultant co-adaptive behaviour by the attacking team. Experiential knowledge shows that the attacking players will adopt self-organising solutions and pass the ball early to make it difficult for the defending team to close the attackers down and negate the opportunity to earn the additional defending player back.

The constraints builder for field hockey

The following section presents the reader with pertinent constraints for consideration in a field hockey context. In Figure 7.1 we present a constraints builder employed for field hockey. The panel comprises three sections, each representing one of the three core constraint categories, namely individual, environment and task.

Figure 7.1 The constraint builder for field hockey.

Individual field hockey constraints

While there are a wide range of individual constraints for hockey players, perhaps the most important is the intentions of a player that act as the key organising feature shaping cognitions, emotions, perceptions and actions. An example of how a coach can influence a player’s intentions, is through the presentation of the principles of the game. A player that understands the principles of the game can apply them to the game contexts in which they find themselves in and as a result they act explicitly or implicitly to shape perception–action couplings in specific moments. The recently published GB Hockey, Talent Development Framework (https://view.joomag.com/great-britain-hockey-93026-gbh-talent-development-framework-booklet/0794501001518100531?short) provides excellent examples of attacking principles. For example, having an understanding of the guiding attacking principle of Forward, First, Fast will encourage players to select and execute the best mode and method to move the ball forward in an attacking context. In a CLA, the instructions given and the questions asked by a coach are more powerful when grounded in the principles of play. For example, ‘I am interested in why you thought that was the right time to play forwards?’ is a question that could be employed to help manipulate a player’s intentions and constrain conscious processes like strategy, in addition to unconscious processes like the perception of, and interaction with, affordances. However, true understanding of the principle must be developed through ‘doing’ and knowing ‘of’ the environment. Knowing why Forward, First, Fast is a desirable principle can only be realised by experiencing the relative effects of slow build-up play in contrast to a Forward, Fast, First intentions. Coaches therefore need to develop an understanding of the principles of play by having players learn them ‘in action’.

Task field hockey constraints

The task constraints that are most commonly manipulated by hockey coaches are pitch boundaries, goal orientations, the number of players allocated to each team, the starting position of the players and the ball feed position, the manipulation of the point scoring system and the addition of any time limits, additional rules and regulations.

Environmental field hockey constraints

Environmental constraints for hockey are significantly impactful in shaping human behaviour but manipulating them is notably less practical in nature than changing task constraints, and as a result requires more creativity from the coach. A significant environmental constraint in hockey is the surface type with hockey at the highest level being exclusively played on artificial surfaces. However, these surfaces can vary in terms of; base (sand or water based); texture (high or low grip – high friction vs low friction); moisture level (dry or saturated), consistency (even versus variable bounce) and hardness (high or low bounce). All of these different physical environmental constraints act to shape the intentions, perception and actions of the players. For example, if a turf has high bounce characteristics it is advantageous when controlling the ball for players to adapt their movement solutions; normally, this is achieved by positioning the stick in a more vertical position. In international hockey, players are constantly exposed to a wide variety of surfaces to which they must ‘re-calibrate’ actions to adapt very quickly. To that end, coaches should consider systematically varying the training pitches they utilise (or, where possible, make alterations to the turf characteristics) in order to support the emergence of players with adaptable movement solutions (dexterity) to exploit different pitch characteristics.

Field hockey case study

Introduction – the current landscape

As highlighted above, the case study is centred around a performance field hockey context. The team Danny coaches is currently ranked in the top 25 international teams in the world (current FIH world rankings) and takes part in regular international tournaments on a European, Commonwealth and World level. The squad is made up of approximately 30 players, all aged between 17 and 30 years. The majority of the players operate as part-time or semi-professional hockey players, requiring them to balance work, domestic and international hockey commitments. On average, the group has between 50 and 60 contact days per year. The majority of training contact time is ‘camp’ based, comprising 4 × 2-hour training sessions across two-day periods. Additionally, the team is brought together approximately four days before each tournament. The group is working hard to build on its recent significant improvement with the goal of continuing to narrow the gap between the current level of performance and that of the leading teams in the world.

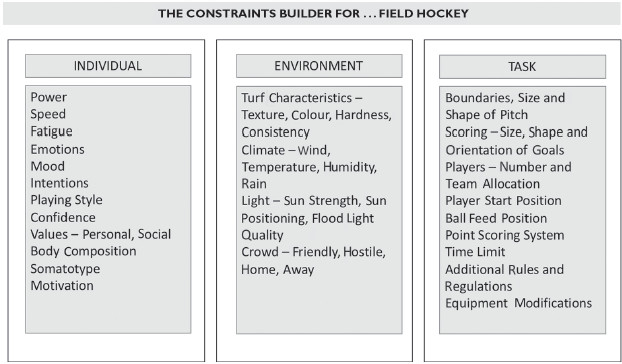

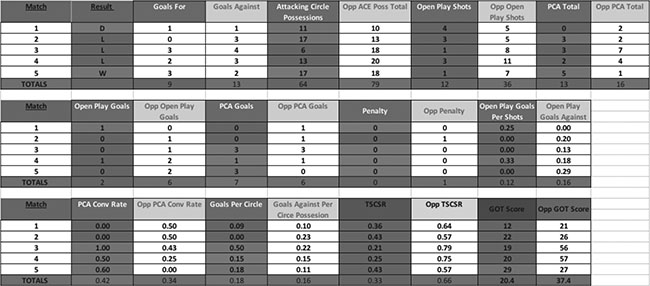

In line with every other top team in the world, the team has access to a performance analysist who records and collects data on each Game. Figure 7.2 provides a stripped-down example of the performance analysis data received by the coaching team following five competitive fixtures played at a recent high-ranking tournament. All five games were played against higher-ranked international teams. The analysis provides the performance outcomes achieved by both teams, including: score; number of circle possessions; number of shots; penalty corners and penalty strokes. As can be observed in the data, a significant point of difference between the team Danny coaches and the higher-ranked teams was the number of open-play shots taken and as a result the number of open play goals scored (i.e. X vs Y). In addition, the analysis provides two ratios, the number of goals scored per shot and the number of goals scored per circle possession. This data reveal the quality of the opportunities created alongside the ability of the team to convert them. The ‘GOT’ (Goal Opportunity Threat) score provides an indication of the quantity and quality of the shooting opportunities created. Each shooting opportunity is given a score out of 5. For example, unopposed shots in the centre of the attacking circle are valued as being the most desirable opportunities and are awarded 5 points. Shooting opportunities are awarded fewer points as the shooting angle decreases and scoring becomes more difficult, for example shots from close to the goal line are awarded 1 point. In addition, if any shot is judged to be contested by a defender the score is reduced by –1. Finally, the ‘Team Shot Corner Stroke Ratio’ (TSCSR) score provides a percentage likelihood of winning the game based on the scoring opportunities generated by both teams (the shots at goal/the number of corners/penalty strokes earnt). Previous data shows that any score of over 0.40 provides an excellent opportunity to win the game. As can be viewed from Figure 7.2, the team’s average ‘TSCSR’ score for the tournament was 0.33, clearly identifying an area for performance improvement.

Based on the analysis of the data and conversations with the coaching and playing group, the key rate limiter was determined as the lack of ability to create goal-scoring opportunities from open play (12 open play shots to the oppositions 36), particularly when playing against higher ranked teams. As confirmed by the post-match analysis, shooting opportunities were only one-third of those created by our opponents and when they did emerge, were quickly prevented due to highly organised, tight defending. Deeper analysis looking at our attacks after we had re-gained possession in open play in their own half, demonstrated that the players were turning down the opportunity to counter-attack by taking too long to move the ball into the final third. Essentially, the team were failing to follow the principle of Forward, Fast, First, as discussed above. Consequently, this was giving opposing defences time to funnel back into organised defensive positions. A team’s defence is most disorganised when it loses the ball, particularly when the ball and team are committed to attack and are deep in the opposition half. Consequently, losing the ball at this point, means they are vulnerable to a fast counter-attack. A counter-attack opportunity is defined by a loss of possession by the opposition team, which could be anywhere on the field, that in-turn facilitates an attacking opportunity against a disorganised defence. Often, this transition of possession facilitates a numerical overload for the attacking team, with the opportunity to exploit a large space defended by fewer defenders (i.e. a large playing area to defender ratio) in the attacking phase and is the reason that a counter-attack offers an excellent opportunity score. An effective counter-attack is therefore characterised by a fast transition from defence to attack where the ball is moved down the field as quickly as possible to exploit out of position defenders and the potential numerical superiority. The counter-attacking opportunity requires exploiting a short temporal window of opportunity and therefore requires playing at high speed, a particularly challenging task constraint as it requires highly precise execution of passes from the attacking team.

Figure 7.2 Performance analysis data from five international field hockey fixtures. The data includes (both for and against): Goals, Attacking Circle Possessions (ACE), Open Play Shots, Penalty Corner Attack (PCA), Open Play Goals, Penalty Corner Attack Goals (PCA), Penalty, Open Play Goals Per Shot, Penalty Corner Attack Conversion Rate (PCA Conv Rate), Goals Per Circle Possession, Team Shot Corner Stroke Ratio (TSCSR), Goal Opportunity Threat Score (GOT).

Based on the background and analysis above, the coaching team decided that one of the most effective ways to increase the scoring opportunities was to place a focus on improving the team’s ability to counter-attack. Discussions with the players revealed that a significant barrier to using a counter-attacking strategy was one of perception, with the players either not aware of when to counter-attack or turning down emergent counter-attack opportunities. It was clear from the exploratory conversations with the players that maintaining possession was valued higher than the opportunity to counter-attack and the associated increase risk of losing possession. This mindset was particularly evident when playing against higher-ranked teams and, as a result, it was clear that the players did not know how to manage risk-reward, that is, when to play carefully and make safer slower passes or when to play faster, making higher risk passes where loss of possession is a greater risk. We address the constraint of player intentions in the case study we present later in the chapter.

Traditional counter-attack practices

Practice at counter-attacking has traditionally been very prescribed with players told where to run and when and how to pass. A good example of such practice is the typical three-man weave seen in basketball. This unopposed practice rehearses what is perceived to be the ideal solution. However, due to the dynamic nature of invasion games, we would argue that an ideal solution does not exist as the solution required is never the same for two different counter-attack opportunities. The aim of any counter-attack practice is therefore the development of players who can effectively react to the emergent dynamic environment, co-adapting their intra and inter-personal co-ordination patterns to optimise emergent counter-attack opportunities. Therefore, the practice environments provided must facilitate the construction of these effective and adaptable behaviours. The following case study provides a worked example of how Danny attempted to facilitate these behaviours in practice.

GROW planning process

A completed example of the four-step GROW planning process (Figure 7.3) and the additional elements of the design process (GROW) are unpacked in the following sections.

What is the goal/intention for this session?

The goal of the session was to improve the team’s ability to exploit and execute counter-attack opportunities.

Figure 7.3 GROW analysis in preparation for counter-attack development session.

How does this link to the overall goal?

Improving the ability to counter-attack will increase the number of goal attempts in open play particularly when playing against higher ranked teams.

The focus for learning is?

Three linked areas were identified as the significant ‘rate limiters’ to counter-attack performance and formed the focus for learning. The first problem identified was a poor level of recognition by the player in possession of when and where to play forwards; this results in the counter-attack opportunities disappearing before they could be exploited. The second problem was an inability to adapt to the player on the ball, with supporting team members struggling to identify when and where to position themselves in the field of play to support the attack. This results in players collapsing the playing space and making it easier to defend against. The final problem: once a support player received the ball there was a lack of accuracy in the technical execution, with players commonly making ball-handling errors, for example, the poor execution of passes when moving at pace.

What’s the current skill level?

The current skill level of the group was identified as being mixed, with some players at the level of ‘coordination’ and others at ‘adaptability’.

What affordances of the performance environment do you want to design-in to the practice?

The aim of the training session is to develop the team’s ability to exploit and execute counter-attack opportunities, therefore, the practice needs to provide the players with multiple opportunities to practise counter-attacking. The practice environments provided need to include an opportunity generated from a transition in possession to exploit defensive dis-organisation along with the potential for an attacking overload in a large space in attack. Additionally, the amount of time allowed to successfully execute the attack needs to be short due to a rapidly re-organising defence.

Which practice environment will you use?

Using the environment selector Danny utilises within his invasion game of field hockey (Figure 7.4), the coaches decided to employ pitch-orientated, performance environments that are more representative of the performance environment.

Figure 7.4 The environment selector – field hockey example.

Which practice environments will you use?

Three practices were selected by the coaching team to bridge the learning gap. Namely, a small-unit practice, a small-sided game and a macro game. These specific practices are presented in the session planner section that follows.

Which constraints from the environment builder will you use and how will you manipulate them?

The constraint builder (Figure 7.1) was employed to help the coaches select the constraints to manipulate in the design and adaptation of the practice environments. These involved a combination of task and individual constraints. The task constraints included adaptations of size and shape of the playing area (boundaries), the point-scoring system employed, the number and allocation of players on each team and an introduction of time limits. The coaches influenced the players’ intentions and playing style within the practice environments; these manipulations fall under the category of individual constraints.

We will know we have been successful if . . .

We see an improvement in the consistency of our counter-attack execution in competitive fixtures. The counter-attacks will be precise, fast and flowing. Supporting players will move themselves into advantageous positions in the field of play and we will be able to observe the teamwork as a unit, effectively adapting individual movements as they co-adapt with each other. We will see the players spending a minimal amount of time in possession of the ball and making accurate decisions regarding where it will be most advantageous to play forwards. This will facilitate the efficient movement of the ball into the attacking circle. The players will begin to feel like it is too easy as they consistently execute a series of connected actions.

Earlier in the chapter, we provided examples of how a field hockey coach can design practice environments to improve performance. In the following section we will illustrate how a CLA session can be brought to life by using the session planner process we introduced in the last chapter. The aim of this element of the case study is to exemplify how coaches can employ a range of different practice environments to bridge the learning gap.

The session planner – explore, exploit, execute

Overview: the session plan below (Figure 7.5) presents the three practice tasks that were designed to bridge the learning gap. As indicated on the RLD and variability dials, the levels of representativeness and variability that were designed-in is increased across the three practice tasks. Task 1 is designed to allow the players to ‘tune’ in to the practice landscape and facilitate the exploration of new solutions to the problem. Task 2 is designed to develop the players ability to exploit the affordances presented within the practice task. The focus of Task 3 is to develop the players ability to execute counter-attack opportunities under pressure.

Figure 7.5 CLA session plan – field hockey (counter-attack).

Task 1: a small-unit practice. The players will be required to complete 5 × 2-minute blocks of a 3 vs 1 small-unit play. The task is designed to provide the players with the necessary time and space to explore different movement solutions within a counter-attacking context. The task constraint manipulation (attacking overload) will provide a moderate level of representativeness (3). This is a deliberate policy to facilitate the likelihood of a greater initial level of success for the attacking team (see Chapter 5). We want the players to have significant numbers of ball contacts (technical executions such as passing and receiving without losing momentum) while still maintaining relevant affordances from the performance environment (i.e. directional and a defender). The 2-minute time limit is included in Task 1 to encourage the players to complete the task at pace to ensure that the movement solutions were representative and a functional fit with the performance environment.

Task 2: a small-sided game. Figure 7.6 shows the 4 vs 4 small-sided counter-attacking game. The picture on the left depicts the goal that the counter-attacking team (Red) are defending. Here, the pitch boundaries are narrowed towards the goal to create a funnel effect to reduce the playing space to increase the likelihood of a tackle or interception and a transition in possession. On the right, the picture shows the attacking goal and represents the counter-attack phase of play following the transition of possession to the Red team. The pitch boundaries at this end of the field are opened up, which provided players from the Red team with a large space to attack. The players will be required to play 4 × 5-minute blocks of the 4 vs 4 small-sided game. The levels of representativeness and variability designed-in to this task were elevated from Task 1 (7). A manipulation (increase) in the player numbers and the allocation of players to an even-load game (the same number of players on both teams) is predicted to facilitate an increased level of representation (7). To invite the attacking players to move the ball quickly and efficiently into the attacking circle, the point-scoring system will be adapted to encourage the defending players to re-organise quickly in an attempt to dissolve the counter-attack opportunity.

Figure 7.6 Counter-attack practice.

Task 3: the session will finish with 4 × 6-minute blocks of an 8 vs 8 game. In contrast to the previous practice tasks, this task is designed to provide a more limited number of counter-attack opportunities. The motivation behind this practice is to place greater value on each counter-attack opportunity with the aim of replicating the value they have in the performance environment. A further increase in the level of representativeness (9) and variability (8) has been designed-in to this practice task by manipulating a series of task constraints. Specifically, this involved an increase in the number of players allocated to each team and a point-scoring system that places a greater value on executing counter-attacks. Furthermore, the defending systems of both teams are to be manipulated to encourage a live transition of possession in areas of the pitch conducive to counter-attacking (defending deeper in the pitch to invite the opposition team to attack the circle). The scoring system is manipulated to provide additional reward for goals scored via a counter-attack (double points). In addition, an escalating point scoring system over the 4 × 6-min blocks (i.e. a goal in block 1 earns a team 1 point, a goal in block 2 earns a team 2 points, etc.) will be employed.

Session reflection

This section is written from Danny’s point of view: Task 1 is a practice we often use to facilitate the players to ‘tune in’ to the environment while gaining opportunity for repetition without repetition of the decisions and actions required in a counter-attack context. The execution error rate from the player(s) in possession of the ball at the start of this practice was very high, with the players becoming increasing frustrated with the performance, particularly as they perceived this to be an easy practice. The players adapted and self-organised by slowing the pace of their counter-attacks down. While this facilitated more success, it was clear that the speed at which the players completed the counter-attacks would not be effective in the performance environment and therefore lacked sufficient representativeness. The coaching team spoke to the playing group half way through the practice in an attempt to influence their intentions and increase the speed at which they were counter-attacking. However, upon reflection, the introduction of a points system that rewarded the execution of faster, more efficient counter-attacks would have perhaps been a more impactful solution.

The coaching and playing group all felt that Task 2 created a realism (representativeness) that was missing in Task 1. This was evidenced by the players making similar decisions and evidencing similar actions to those observed in the performance environment. The more natural (and random) facilitation of counter-attacks appeared to help facilitate this improvement in action fidelity. In this task, a lack of understanding of where and when to position themselves was the clear ‘rate limiter’ to the successful execution of counter-attack opportunities. This was illustrated by the players consistently collapsing space, and as a consequence negating the attacking numerical advantage. A discussion with the players demonstrated that they understood the principle of providing ‘stretch’ (making the playing space as large as possible), but some players were still struggling to transfer this understanding onto the field of play (see the discussion about understanding the principle of play earlier in the chapter: they ‘knew about’ but not ‘of’ the performance environment – and see Chapter 4). Moving forwards, we will add additional task constraints in the form of line markings to the playing area, providing spatial markers that have the potential to guide player positioning. This reflection highlights the challenge coaches face when attempting to transfer ‘knowledge about’ into ‘knowledge of’ the environment.

Interestingly, in Task 3 the elevated value of goals in the final block (4 points for a goal or 8 points for a counter-attack goal) facilitated very few counter-attack opportunities. From observing the players behaviour and discussing the practice with them, this was a product of the team in possession of the ball taking significantly less risk in attack for fear of being counter-attacked against. Although this presented less opportunity to practise our counter-attacking it did create the value placed on them and was representative of the performance environment. It was interesting to watch the co-adaptation process happening as the teams started to adapt their defending to generate the opportunity to counter-attack. Moving forwards, it will be interesting to observe the impact of a declining point scoring system on player behaviour.

We have seen a positive impact of our sessions on our counter-attack execution in the performance environment and these observations were consistent with the GROW analysis completed prior to the session. The biggest impact has been the improved positioning of our support players, which has significantly improved, evidencing an ability to co-adapt by moving themselves into more advantageous positions. However, we are still demonstrating inconsistency in our ability to execute, with passes still not being delivered to their intended target at crucial moments. We are looking forward to putting our counter-attacking into action against the leading teams in the world over the next 12 months.

Summary

In this chapter we explored the application of the CLA to an international field hockey context. The GROW analysis emphasised the importance of counter-attacking in this context. We highlighted the importance of the constrain to afford principle has on facilitating targeted and transferable development. In addition, we discussed the role different linked practice environments can play in bridging the learning gap. Within these practice tasks we exemplified how different levels of representativeness and variability can be designed-in to the practice. We have provided brief examples of how a CLA could enhance the practice of field hockey coaches. We will build on these ideas in more detail in a forthcoming book in the series: A Constraint-Led Approach to Field Hockey Coaching. This book will be jointly written by ourselves and international hockey coaches who will provide the unique examples from their own work with performance and development field hockey players. We look forward to sharing and discussing further ideas with you there.