Figure 8.1 Hitting off a towel can be used to simulate hitting out of the rough or if used on the driving range to accentuate the importance of making contact with the back of the ball.

8 A constraints-led approach to coaching golf

Introduction

Although successful golf performance is predicated on effective course management, where golfers ‘navigate’ their way around the contours and ‘natural and man-made’ hazards of each unique hole, much of golf coaching takes place off the course on driving ranges and practice grounds. Clearly, little importance is attached to the environment in terms of its role in shaping the skills needed to play golf and much coaching is focused on developing good golf swings. This separation of the individual and the environment when considering skill learning is common across many sports and has been criticised by those who view the individual and the environment as inseparable when designing skill learning activities. This idea is captured in a relatively new definition of skill (as successful adaptation) proposed by Araújo and Davids (2011a), discussed in the earlier theoretical chapters. This contemporary view, which we use in a CLA, emphasises the importance of learners attuning or adapting to the performance environment as discussed in Chapter 3. The best players are the ones who are best ‘adapted’ to the environment. This means that learning needs to occur on the course or for the aspiring tour player on as many courses as possible. An additional challenge for these players is that the courses they learn to play on need to help them develop the wide range of capacities (mental, emotional, perceptual and physical) needed to succeed on championship courses. For example, a golfer brought up on the links courses of Scotland, is likely to develop a style of play that is perfectly adapted to these unique playing environments. Hence, successful links golfers are perfectly attuned to the contours of the course, adapt shots to exploit the wind, are expert at bump and run shots, are able to play effective shots from deep rough and get out of deep, deep pot bunkers with steep walls. In contrast, a golfer brought up to play on courses in America, is more likely to be able to hit long and use high-flighted irons to land the ball softly on receptive greens. Top players, who travel around the world, therefore need the adaptive skill sets to excel on all types of courses, in all types of conditions. The average club player who only plays on his/her home course would ‘simply’ need to become attuned to the one course. Golf coaches should take these contexts into account when working with learners.

The environment shapes the golfer

These brief examples highlight why it is essential to consider the performance environment when working with players. However, for the golf coach, this obligation presents some interesting challenges. For example, when much coaching takes place on artificial surfaces at the driving range, there is a need to find ways of making the environment more representative of the ‘real thing’. For example, the hard mat can be very forgiving when a player hits the ground before the ball, allowing the club to ‘bounce’ and enable a good contact with the ball. However, a similar shot on turf on the course would lead to a very poor contact and outcome. Learning to play by hitting off artificial mats results in players developing a golf swing that is suited to that specific surface. However, attuning to these environments may not transfer to hitting off turf. Spending most of the time hitting off mats may give a golfer a false impression of how well they are hitting the ball and ultimately lead to frustration when they play on the course. Consequently, it would be advantageous if the player could experience the consequences of swing ‘errors’ when practising at the driving range and even better if practice could be on a more realistic surface. When winter practice precludes the use of turf, adopting a CLA may be helpful. Essentially, the surface needs to be modified as much as possible to make it more representative of turf so when any contact that is not clean on the ball (i.e. hitting the ground before the ball), the consequences should be a similar outcome as if playing on grass. A simple solution would be to place a towel on the floor and hit the ball off that. If the player hits a full iron shot off the ground (towel) before the ball, this would result in the towel crumpling up and a poor contact with the ball. The same solution can be applied to practising hitting from the rough on the course, when hitting the grass behind the ball can reduce the quality of ball contact.

Figure 8.1 Hitting off a towel can be used to simulate hitting out of the rough or if used on the driving range to accentuate the importance of making contact with the back of the ball.

Knowing the individual

Of course, when taking a position that the individual and environment relationship plays a complementary role in skill learning, equal emphasis should be placed on both but efforts to gain a deep knowledge of the individual should not be reduced as a consequence. When implementing a CLA approach, the first interaction between a coach and player should therefore be a fact-finding mission to uncover as much information as possible. Essential to this process is investigating the background of the individual to understand the context of the player’s current golf game; we need to know where he or she has come from and where he or she wants to go in terms of performance.

The history of individuals is crucial and includes finding out more about their work, sporting background, taking account of other sports played, and, importantly, their physical status such as any prevailing conditions, disorders and injuries. The importance to the coach of thorough background knowledge is paramount, prior to even watching a learner play. A brief story about one of the co-authors of the forthcoming CLA golf book in this series, Peter Arnott, a professional golf coach, illustrates this point perfectly. Early in his golfing career, Pete used to work as a surveyor, travelling 300 miles per day. Therefore, when he went to the driving range after work, he was often very stiff in the back, from the hours spent in the car. This stiffness affected his mobility and, ultimately, his golf swing, and at the beginning of his practice session resulted in the low point of his swing being near to his back foot. He, therefore, needed to place the ball further back in his stance to ensure the ball was matched to this low point. As he warmed up and his mobility returned, the low point of the swing moved further forward, and he was able to put the ball further forward in his stance. So, consider a coach who did not know Pete’s background looking at his swing and coming to conclusions about why he was hitting the ball fat when the ball was placed in a conventional position in the set-up.

This story highlights the importance of coaches seeing the golf swing as being part of a dynamic system, where a ‘one size fits all’ approach can negatively impact the golfer’s performance. If the coach followed the guidelines in the coaching manual, that is, to place the ball at specific points in the stance for different clubs, the ball might be placed inappropriately and lead to poor ball contact, despite the fact the learner might have made a good swing. For example, in the case of Pete, requiring him to use his three iron with the ball placed just inside his front foot (e.g. as recommended by the coaching books), would risk him hitting the ground behind the ball. Coaches can use a CLA to help players ‘find’ their low point. If hitting on turf, the coach can use an alignment stick to create a depression in the turf. She then places the ball on the front edge of the depression and asks the player to hit the ball. The place where contact was made with the ground (i.e. where the divot was created) tells the player and coach the low point of the swing. Rather than making a decision based on one ball, the coach should ask her to hit four to five balls to assess the consistency of the low point. Once consistency is confirmed, the golfer should adopt a process of repeat and correct; if the divot is consistently taken before the ball, the player should move his/her stance further forward by the distance behind the ball. If taken in front of the ball, the stance should be moved back. To summarise, the position of the ball in the stance should be seen as dynamic rather than fixed, and players should be encouraged to explore the ball position in his stance at the beginning of every practice session. Additionally, during competition, the ball position in the stance should be viewed as being dynamic and should vary depending on the conditions. For example, not every seven-iron would have the same ball position as it would depend on environmental factors such as slope, type of grass and ground conditions, as well as intentions such as intended trajectory due to wind conditions or the height needed to exploit the pin position/ground conditions. In summary, ball position is dynamic and part of the process of finding a solution to a unique performance problem on every shot. The dynamic nature of practice, required to enhance performance, is aligned with Bernstein’s (1967) conceptualisation of practice as ‘repetition without repetition’, as noted in the theoretical chapters.

It should be clear from the previous discussion that the pursuit of a textbook ‘perfect’ golf swing with players by coaches is inappropriate and coaching should be tailored to the characteristics of each individual. Going back to our main point in this section, knowing as much as possible about a player’s background allows the coach to understand why they swing a golf club in the way they do and informs the way that he/she should talk to the player and inform the learning activities they create. For example, previous sports played will influence the way an individual swings a golf club, with some sports helping (e.g. a rotary swing in hockey) or hindering (e.g. a more linear swing in cricket batting) when a beginner starts to play golf. Knowing the sporting background of a new golfer enables the coach to avoid golf ‘jargon’ and communicate in a language that he or she understands. For example, if the coach was working with an ex-tennis player and trying to articulate what the swing path for hitting a draw shot is like, (s)he might ask him/her to describe the shape and feel when hitting a topspin drive; a similar action as required in a draw shot. Alternatively, if the client played football, (s)he might ask him/her to imagine the feeling of bending a free kick around the wall into the top corner. Knowing the client’s physical history (i.e. fitness level and any previous injuries) also provides more knowledge to understand the ‘rate limiters’ on the emergent swing of the golfer. For example, knee injuries or lower back pain, can impact the emergent golf swing and should be taken into consideration by the coach.

Once a golfer becomes experienced, he or she will develop a signature golf swing. For example, there may be a ‘natural’ right to left (a draw or hook), or left to right (a fade or slice) flight trajectory. However, often players can become frustrated with the limitations of their swings and seek to change things through consultation with a coach. Decisions to change established techniques should be carefully considered, as deeply engrained movement patterns are difficult to change. Such decisions are likely to result in a period of instability and accompanying reduction in performance as the player seeks to re-organise. A recent conversation with, Jessica, a nine-handicap golfer, illustrates this point. Jessica had just come back from a lesson with her club pro as her natural shot was to ‘slice’ her drives as she believed this was the key reason why she could not get her handicap any lower. The coach worked hard with Jessica focussing on the swing mechanics (i.e. the path of the arms) to create a swing path to draw the ball (i.e. move it from right to left in the flight). She had some success on the driving range while repeating the same shot over and over again. Later that afternoon she took her ‘new’ swing out onto the course with a sense of confidence; she had cracked this! However, to her surprise and frustration, the new swing was not effective, and, in fact, was so deleterious to her scoring she abandoned it after five holes.

Golf coaching and skill learning principles

This example highlights a number of issues related to skill learning in golf. The first question to ask is: was attempting to create a new swing path the right option? One problem was that the coach took this decision without getting detailed information about the player’s movement history and without seeing her play on the course. Given she was playing off a handicap of nine, how bad was the ‘slice’? Was her performance significantly worse than other low handicap golfers or was she losing shots in other areas of her play? A second factor that may not have helped Jessica was the creation of an internal focus of attention. Requiring the golfer to focus internally can lead to attempts to consciously control movements, which has been shown to lead to slower learning (Gray, 2018). The third issue was the focus on blocked practice (i.e. repetition after repetition of the same shot), which results in better performance in the learning phase, but actually leads to worse performance when transferred to the competitive environment. Research shows that blocked practice leads to an illusion of competence as seen with Jessica (Simon & Bjork, 2001).

Constraints in shaping a shot

An alternative approach adopting CLA principles, would be to create a task where the learner used variable practice alongside an external focus of attention. For example, Jessica could be given a target to hit and asked to explore hitting that target by using different movement solutions. By asking her to hit the target by creating different flight characteristics, such as shaping the ball left-to-right, straight and right-to-left, Jessica would be directed to explore the flight characteristics and through questioning encouraged to link outcomes with how specific movements felt. Task constraints can also be constructed to help players learn to create different flight characteristics. One useful constraint is to create a ‘gate’ approximately 2 m wide and placed about 3 m in front of the golfer, using two alignment rods (or even two narrow garden canes). The golfer is asked to hit the ball through the gate to hit the target. Figure 8.2 shows the set-up on a course. In this case, the positioning of the gate meant that the golfer had to create draw on the ball to hit the target. In Figure 8.2, Jessica could add in another gate, to the right as we look at the picture. Alternatively, one pole could be placed directly in line with the flag stick and she would be asked to hit to the right and left of the pole in turn.

Figure 8.2 Bend it like Beckham. In the above figure, asking the golfer to hit the ball through the gate in order to hit the target led to the emergence of a golf swing that created ‘draw’ (right to left swerve) on ball flight.

Of course, the golfer is not allowed to use these poles on the course, so a progression from this practice task would be for learners to use natural features of the course that help them to solve the performance problem by shaping different shots. For example, in Figure 8.2, the golfer could be required to play from behind the trees on either side of the fairway and given the challenge of hitting the flag. Practising on the course is, therefore, the ideal scenario and the golf coach should take every opportunity to take learners out onto the course for more specific transfer. In the discussion above, we have provided a few examples of how the golf coach can design-in constraints into practice to help golfers improve performance. In the following case study, we will illustrate how a constraint-based practice session can be brought to life by using the CLA session planner process we introduced in the last chapter.

A case study: Thomas can’t pitch

Introduction

Five years ago, 17-year-old Thomas was introduced to golf by his dad and was instantly hooked. He joined his dad’s golf club and played every day over the summer. As an athletic person with good hand–eye co-ordination, Thomas seemed to be something of a natural golfer and within a few years he was playing off an 18 handicap. Fast forward to now and Thomas was a two-handicapper on the fringes of his national squad! To progress, this year Thomas had joined a championship golf course and was enjoying the harder challenge it was presenting. However, despite his hard work, over the last year Thomas had not managed to reduce his handicap at all. Thomas liked to record performance ‘stats’ and kept a record of his rounds, storing information on a stats package online. The data were particularly revealing. They highlighted that, although he could drive 280 m, he was, in comparison to the pros, attempting too many drives that were unplayable, either out of bounds or not giving himself a clear line of sight to the hole for his second shot (i.e. behind a tree or in thick rough). Most of the bad shots were hooks that put him in trouble. One other weakness Thomas noticed was that his pitching (from 10–50 yards from the pin) was nowhere near the level it needed to be, with the stats package highlighting that his current handicap, when relating to other skill levels, was more like a 12-handicapper than a two-handicapper in this area. Consequently, at the end of the season, Thomas and his dad sat down and reflected on his progress. He had achieved some success winning a few club competitions before his handicap dropped, but now he seemed to have hit a bit of a plateau. With winter coming up he decided he had a perfect opportunity to take stock and ‘go back to basics’ with the goal of starting next season a better player and in good shape to achieve his next goal. Next season he wanted to get down to scratch or below and play for his national team in competitions. As part of his winter plan, Thomas and his dad decided that he needed to take a series of lessons with a club pro and found out that the club had a number of coaches. Thomas asked around, and while the view was that all the coaches were great, the new guy, Paul, was a little different to the others as he spent less time trying to make fundamental changes to the golf swing and focused more about how to play the golf course. Apparently, Paul’s motto was ‘improve your score, not your golf swing’ and much of his coaching took place on the course, whereas the others spent much of their time coaching on the driving range. From his experiences in other sports, Thomas knew that over-thinking and becoming too technical would not work for him. It seemed Paul was the coach for him and he eagerly booked in for a series of coaching sessions.

The first session: taking stock

Thomas met Paul for his first session in the club café and spent the first half hour answering a wide range of questions about himself and his game. Paul explained that to design an effective coaching programme, best suited to Thomas’ needs, he needed to know as much about him as he could. Questions ranged from: what he did for work, his history of movement, any injuries, conditions and disorders that he had, his sporting background and, finally, his thoughts about his own game and how golf should be played. Paul listened to everything Thomas said and was particularly intrigued by the change in Thomas’ pitching ability and probed away at this issue. Thomas revealed his frustration to Paul and indicated that he could not understand why he struggled with distance control and strike. Given his length off the tee and his ability to then hit into the green with low irons, he felt he was costing himself needless shots when he was so close to the pin. ‘This is ridiculous’ was the key phrase that Paul heard him say and could see the anguish and confusion in Thomas’ voice and facial expressions. From his experience, Paul felt he might know the answer to the conundrum but wanted to confirm his diagnosis for himself. He took Thomas onto the practice hole and threw eight balls down in various lies and places around the fringe of the green and asked Thomas to chip each ball as close to the pin as possible. The results were mixed with very few of the balls coming to rest near the pin, with some long off the putting surface. Five of the balls were cleanly hit, with a low trajectory that landed firmly at the front of the green and rolled out past the flag. Three of balls were poorly struck. Thomas had hit the ground before the ball with a large divot or as Thomas described ‘I hit them fat’. These balls came to rest well short of the flag. The results confirmed to Paul what he had suspected. The problem with Thomas’ pitching technique, was that he de-lofted the golf club at impact and had too much shaft lean towards the target at ball address and then at impact, with the ball position predominantly nearer Thomas’s trail foot at set-up. This all led to a steeper angle of attack and resulted in lower ball flight with little to no spin on the golf ball. Paul sat Thomas down and asked if he could explain his results. After watching Thomas initially struggling to explain it, Paul directed him towards thinking about the ‘effect of his action’ rather than the action itself. Paul used the analogy of an aircraft crash-landing onto the ball rather than a smooth landing on a runway. Paul then moved the conversation to how Thomas might go about changing the ‘effect’ of his action in such a way that would improve the mechanics of his technique. Thomas came up with several suggestions regarding what he might do to improve his pitching action. Rather than confirm whether the changes would work or not, Paul smiled at Thomas and said, ‘let’s go to the short game area and find out if this works’. Paul wanted to afford Thomas with the opportunity to explore, discover and self-organise a movement pattern rather than prescribe a fix.

Paul placed lots of balls round the short game area, but before asking him to hit any of them, Paul now introduced Thomas to athlete’s foot powder and sprayed the face of Thomas’s wedge with it. Paul explained that when the clubface made contact with the ball, the powder would be ‘wiped off’ and provide instant visual feedback of the contact point (see Figure 8.3). Paul got Thomas to hit a few shots and asked Thomas to look where he had impacted the ball. All the contacts were near the centre of the face. ‘The fact that the contact is high on the club face is why you are not getting any height on your shots’, Paul said. He asked him where he thought he should be making contact and Thomas said he needed to try and ‘hit it lower on the club face’. Paul agreed and set the task of only hitting the bottom three grooves of the wedge, Thomas would know if he had been successful because of the visual feedback provided by the foot spray. Thomas hit a few shots, exploring different solutions and checking where he hit the ball on the face each time. Initially, Thomas struggled to hit the bottom three grooves, often hitting too low on the face and when he tried to correct, he went back to being too high. However, after a while he began to consistently hit the ball in the right spot and in doing so was producing a more consistent outcome with ball flight having a much steeper trajectory than with his old technique. Notably, Thomas reported that he was beginning to feel that he couldn’t hit a ‘fat’ shot with these new dynamics. Paul probed Thomas again ‘what does that feel like’ Thomas said, ‘It feels like I am slightly thinning it, it feels like I am clipping it off the turf’. Paul then asked: ‘Did you do anything in the way you set-up to change this?’ to which Thomas replied, ‘Yeah I moved the ball forward in my stance’. Paul probed again: ‘Anything else feel different?’ ‘Yes’ replied Thomas, ‘it feels like in order to only hit the bottom three grooves that my right hand is more active in the downswing and that when I finish the shot my hands more towards the left pocket of my trousers’.

Figure 8.3 The use of foot powder on the club face can give a golfer instant feedback on the contact point made with the ball. The figure shows (left) too high, (centre) just right and (right) too low.

In setting up the task in this manner Paul was keen to give Thomas a more external focus of attention (knowing that if he got too technical with Thomas it would be counter-productive). Paul wanted ‘the task’ to build the new action a more external focus of attention. The concept of allowing the task to build the action and using an external informational constraint (i.e. the foot powder) to support the emergence of a re-organised co-ordination pattern are core principles of Paul’s approach when he applies the CLA – essentially, he was affording Thomas the opportunity to self-organise a more functional way of controlling these shots.

Designing a CLA session to develop pitching skills

After assessing the current landscape of Thomas’ golf performance, Paul focussed on the area where he thought he could make the most difference to Thomas’ scoring. That is, the area of his game, which was the greatest rate limiter to improved performance, which he judged to be pitching. Paul used the GROW model to summarise the key features of the golf lesson (see Figure 8.4).

After identifying the goals for the session, Paul considered the reality and options to shape the Way Forward. He decided to add in a task constraint of using foot spray on the face of the club to encourage Thomas to strike the ball more consistently, lower on the face, and in doing so shallow the angle of attack into the ball. Paul also wanted every shot to matter, so rather than just pitching aimlessly to focus on ‘technique’, he set up targets placed around three different holes requiring Thomas to hit different distances. This constraint was added to help Thomas develop control and awareness of swing length and speed to achieve specific task goals. Figure 8.5 shows the set up for one ball position to hit to three pin positions. Finally, Paul outlined how he would set up the practice environment and how he would prepare Thomas for the session.

Selecting the practice environment

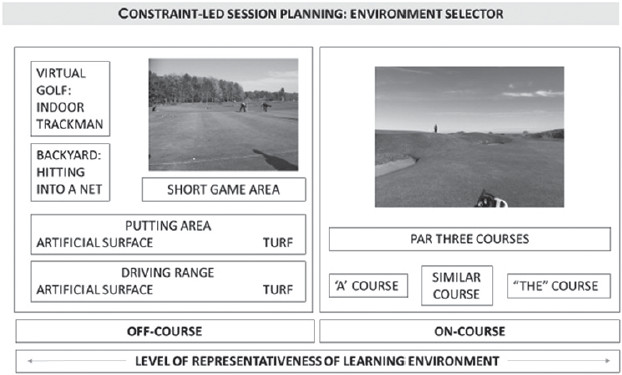

Using the environment selector, Paul’s focus on pitching resulted in him choosing to use the short game area. This environment allowed him to spend as much time as possible ‘pitching’ as well as provided an environment that was representative of the course. This decision also allowed him to utilise the bunkers to increase the level of challenge by asking Thomas to pitch over them in Task 3 in an attempt to manipulate his emotions during practice.

Choosing the constraints to afford

Paul used the constraint builder to select the constraints he wanted to use to ‘invite’ Thomas to develop a more functional pitching technique. To do this, he chose a mixture of individual, environmental, task constraints. As discussed in the GROW section, Paul’s choice of the short game area enabled him to replicate the actual environment of the course and also the opportunity to manipulate emotions by requiring Thomas to hit over bunkers. He also chose to add in a task constraint of a foot spray on the clubface. To ensure the practice task had a purpose and consequence, Paul set up a target zone around three flagsticks placed at different distances to design-in variability in hitting distances. The target zones enabled Thomas to get instant feedback on the accuracy of his performance.

Figure 8.4 Using the GROW model to plan a pitching lesson.

Figure 8.5 This figure shows the set-up for one ball. To enable the task difficulty to be matched to emergent performance, the diameter of each target area can be reduced or increased by 30 cm after each set of 10 balls. If Thomas got 8/10 or more in the target zone, the zone diameter would be reduced by 30 cm, if he got 4/10 or less it would be increased by 30 cm. Any score of 5–7 would mean the target size would remain the same.

Figure 8.6 The environment selector for golf.

Figure 8.7 The constraints builder for golf.

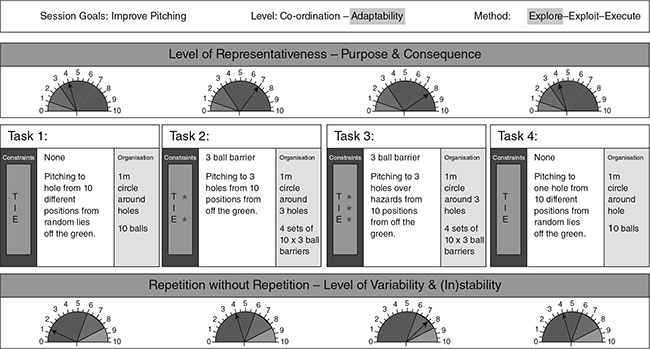

The session planner

Overview: once the previous sections had been completed, it was easy for Paul to fill in the detail on the session planner. The dials show how Paul manipulated representativeness of the practice task and variability. After initially providing a relatively low level in Task 1, variability was increased through to Task 3 with the intention of creating instability, by requiring Thomas to hit over bunker, potentially when quite nervous, with a commensurate impact on the swing. Task 4 was a repeat of Task 1.

Task 1: a pre-test. Paul set up Task 1 to provide a baseline of Thomas’ current ability including qualitative and quantitative measures such as outcome and quality of ball contact. This task was completed without any additional constraints beyond randomly selected lies with balls dropped around the edge of the green requiring pitches of 10–20 m.

Task 2: in Task 2, Thomas was required to complete four sets of ten chips from the same ball positions, but this time was required to hit to three different pin positions and use the foot spray to gain augmented informational feedback on contact area. The target size would be adjusted depending on performance in line with the guidelines provided above.

Task 3: this is a repeat of Task 2, however, this time all ball positions will require Thomas to hit the ball over the bunkers surrounding the greens. The aim here is to increase the emotional intensity felt by Thomas to create greater realism in the practice and to deliberately design-in instability.

Task 4: the post-test. To evaluate the effectiveness of the session, Task 1 is repeated. The results would provide Paul and Thomas with the data to inform the design of the next session. Consequently, the CLA session design process becomes cyclical with the next session emerging from the session before.

Figure 8.8 The session plan for golf chipping.

Summary

In this chapter we have brought to life the CLA for golf coaches. We highlighted the importance of golf coaches considering the performance environment as being just as important as the individual golfer in shaping skill during practice. We discussed the importance of capturing the client’s history to enable the coach to frame what (s)he is seeing and how this background may be used to underpin the language used to get across sometimes complex golfing principles. By providing specific examples, we demonstrated how the coach can use a range of individual, environmental and task constraints in practice to create more representative learning environments and add variability to enhance skill adaptation during learning. Finally, using a case study example, we described how a golf coach used the CLA session designer to develop a specific lesson. Of course, in this brief chapter we have only touched the surface of how adopting a CLA may enhance the practice of golf coaches. We will build on these ideas in more detail in a forthcoming book in the series: A Constraint-Led Approach to Golf Coaching. This book will be co-authored with GPA professionals Peter Arnott and Graeme McDowell, who will provide the unique examples from their own work with golfers of all levels. We look forward to sharing our ideas with you there.