SHELFIES

Years before she began work at the Walmart Supercenter in Paramount, California in order to escape from Blue’s Clues and Bob the Builder and her children, Mayra Rodriguez would tag along with her grandmother on regular trips to “expensive department stores.” Her grandfather, who had served in the military, used low-rate mortgages available through the GI Bill to invest in real estate, so by the time Mayra came along her grandmother had discretionary income to lavish on her: “She would dress me up like a doll when she could. I mean, nice stuff. Oxford shoes. Expensive dresses, which I hated.” Mayra may have hated the emphasized femininity of the dresses but she appreciated the luxury—these were “very expensive stores,” she says. Quiet, clean, classy. Between stores they would go to nice restaurants and, once home, they would spend hours picking out the perfect outfits for Sunday services. It’s not hard to pick up the admiration in Mayra’s voice as she describes her grandma: “She had to convey an image that her husband was successful. And she carried herself in a certain way, and she expected to be treated in a certain way, you know? A lady wherever she went…. I hope some of it rubbed off.”

Her grandmother “wouldn’t [have been] caught dead in a Walmart” during those years, Mayra says, though later she softened on Walmart, at least in part because of the “little motorized carts” that could help her get around the store. Mayra worked in the women’s apparel department at the Paramount store, where she was responsible—among other things—for keeping the women’s lingerie section stocked and orderly. This was the part of the department that “took care of ladies’ jammies, purses, and scarves and belts and stuff, all the accessories and stuff that my grandma always had to have matchy-matchy.” Mayra made it her personal mission to bring the section up to her grandmother’s exacting standards: “I try to keep it nice for my grandma. That was my motivation the whole time.”

It was about more than grandma too. It was about creating an environment—an aesthetic experience—in which people could feel that the “impossible [was] possible.” She continues, “When you shop, you’re supposed to take your mind off of reality and just go into where you could be, what you could look like, what you could make your home into.” It was as though Mayra wanted to recreate her childhood experience of luxury in her one little aisle of the Paramount Walmart. In her aisle, she wanted people to be able to escape into fantasy; and she took pride in being the kind of worker, the kind of designer, who might make this escape possible.

Wandering into a typical Walmart on a typical Saturday afternoon, when lines at the registers seem to snake for miles and the shelves are half-empty and the associates are on their knees stocking and seemingly avoiding eye contact, it is difficult to appreciate the amount of pride that some associates take in their work. It becomes easier to appreciate when one returns to the store early the next morning to find the shelves full and organized and—given an aesthetic defined by sheer quantity—inviting, the floors glistening. And if one logs onto the discussion board one will find hundreds of pictures that associates have taken to document their labor.

These are the Walmart “shelfies.” A worker from the apparel department shows off her meticulously folded and color-coordinated sweaters: Y’ALL THIS TOOK ME SO LONG BUT LOOK HOW PERFECT IT IS. I’m gonna cry when I come back tomorrow and it’s destroyed. Another associate posts a picture of hundreds of perfectly placed acrylic paints, bemoaning that she didn’t get a before picture to show just how much work she put into it. Another expresses pride at building her first feature today, a special display of Toll House chocolate chips in various flavors and colors. And it’s not only shelves. A deli associate posts a picture of perfectly rolled meats. She was sad and proud at the same time. Proud because she was able to roll the cold cuts into such tidy meat popsicles because it shows that we go above and beyond for customers. Sad because her commitment was unmatched by her coworkers—she had to do the order last night, since she was off today and her coworkers refused to roll the meats as requested.

An associate in apparel may be the shelfie queen. Between November 10 and December 17, 2016, she posted a full 72 shelfies of the apparel department—jeans, t-shirts, flannels, sweatshirts, khakis.

Together, the photos are a torrent, a merchandise kaleidoscope—repeated shapes and colors of fabric, cereal boxes, chicken stock, hair products, essential oils, flowers, fruit, toys, cardboard. But as remarkable as the pictures themselves are the responses to them. For every banal Good job! or Very nice there is another comment that is thoughtful, specific, and constructive. For instance, there is an emergent consensus that there is too much space between the shelves of the Toll House chocolate chips feature, that there might have been room for another shelf. Writes one associate, my boss is a stickler about airspace he would’ve yelled at me for that but I think it looks great. Another agrees, adding, you can’t sell air, before assuring, you did a really good job though. A third writes Good job!!! before echoing the airspace concern and suggesting that an entire endcap of chocolate chips might be overkill and that half of the shelf should be a different item that sells well with chocolate chips, like a cake mix or something. Twelve more associates comment on the airspace; a few compliment the “striping” of the colors of the different kinds of chocolate chips, although even here there is some dissent: one associate thinks that all of the milk chocolate chips should have been placed next to each other in order to be striped properly.

People find meaning in their work and discover ways to express themselves through it. An associate working produce writes, There’s a pride in it. When I stock the wet wall [vegetables with mist], I make sure to display each item well. Few things shine like a beautifully stocked wet wall. Another agrees: Coming on to nothing but empty spaces and then filling everything you can, and taking a step back and looking at it like…WOW I did that? It honestly does feel pretty good. The associate responds, I take pictures of that type of work.

The shelfies are visual documentation of work well done—they stop time, stabilize a moment of order in what is a constant battle against entropy. Posted to the discussion board they are also appeals for recognition from one’s peers. It is not just that the associates are thinking about a specific aesthetic, alternating green and yellow dish detergent or building a structure out of boxed products that looks like a Jenga game. They are actively thinking about and commenting about and working on their products in order to better sell them. One associate comments that since she became department manager of the deli her sales were 23 percent up over the previous month (though there is probably seasonality to deli sales and so month over month comparisons may not be a particularly useful metric). Another strongly believes that product moves faster when the shelves are completely full. She is probably right. Who buys the last carton of milk unless it is right before a snowstorm? The last sweater looks like it was rejected for a reason as well. There’s a science to selling, and many of the associates are invested in perfecting it.1

One of the things that distinguishes the service sector from other kinds of work, about which we will say more later, is that the unpredictability of customer demand tends to make it more difficult to routinize than other sorts of industries. This can create pockets of autonomy in which workers are able to exercise creativity and feel a sense of investment in the work they do; pockets in which a department manager, who makes somewhere between 40 cents and a dollar more per hour than an entry-level associate, feels so committed to the job that, she writes, [I run] my department like it’s my own business.

SERVICE WITH A SMILE

A long history of scholarship on the labor process documents how the mid-twentieth-century workplace was one in which raw coercion had given way to “manufactured consent.” Human resources departments and strong labor unions had created structures like internal labor markets and incentive payment systems to align workers’ interests with the interests of their employers.2 Walmart works to produce the same effect on a more meager budget. Here, quarterly “MyShare” bonuses, based on storewide sales and metrics like customer satisfaction scores, play a role in aligning workers’ interests with store profits. These bonuses can range from nothing—if a store had poor sales, poor service, or too many worker injuries—to a maximum of around $500 for a full-time worker, every three months. But this still can’t explain individual workers’ investments in store sales, since any one worker would still have an incentive to shirk.

Rather, it is recognition that seems to drive workers more than any additional pay they may receive from bonuses or promotions. It’s Jamal Green feeling like the LeBron James of the cashier crew. Even those cashiers who aren’t regional champions can get their daily stats and compete against themselves and their coworkers. At the end of a shift, each is able to see his or her own “productivity totals”—scans per hour, seconds per item, percentage of items scanned (rather than entered by hand). An associate posts a picture of her daily report because she was in the “high 1400s,” higher than usual for her and she wanted to share ’cause I am super proud of myself!!! Another day, another group of cashiers are comparing notes about the tricks of the trade that can help them get their numbers up—stopping the clock while between customers or while looking up an item. Others discuss whether the number of scans or errors per hour is the most relevant statistic. There are lots of ways to achieve distinction, and slow and steady has its adherents.

Years ago, Walmart figured out how to use information technology to maximize the efficiency of its sprawling distribution system. Today it uses similar technologies to reflect employees’ performances back to them—mini-measurements that both reinforce the idea that employees are being watched and give them a series of small accomplishments to which they might aspire. These are complex strategies designed to appear and be experienced as nudges3 while masking their surveillance functions. They are the analog to wearable technologies like the Fitbit or the Apple Watch, except that the outcome is labor productivity rather than personal fitness and Walmart is aggregating the data for its own uses rather than some distant technology company, which is aggregating the information about your steps and heart rate in order to sell it to a company—like Walmart—that can pitch you the perfect pair of running sneakers.4 Nudges work on both the production and consumption side of the service economy.

A cashier gets her second recognition in three months from the company, this time a framed Award of Excellence for “going above and beyond and providing superior service to our customers” (she received it for convincing lots of customers to apply for Walmart credit cards). Beginning in March of 2015, Walmart instated a volume-processing item (VPI) program in which associates could “adopt” an underperforming item and try to increase its sales—winning awards at the store, market, and regional level for the associate who increased sales the most. An associate would get one point for every “sales dollar increase” this year versus last during the same time period; one point for every “unit sold increase”; and two points for “every profit dollar increase.” The highest performer at each store would get $50 and a certificate at the end of the quarter; the market winner would get $75 and a certificate; and the regional winner would get $150 and a certificate. Associates compare notes on the best products to upsell: four-pack chocolate milks, 88-cent store-brand hair ties, popcorn tins, Bounty single-roll paper towels, tilapia fish.

All of these little achievements are indicative both of associates’ drive for personal distinction and of the real sense of community they find among their peers, a community without which being a fast scanner or fastidious stocker or a genius at the VPI would likely feel less important. Just as wearables’ self-observation and self-motivation work best when people share their results with friends, the surveillance-cum-measurement data work best when others can see them. Ironically, the discussion board, developed in part to help workers see through to the control functions of seemingly neutral incentive systems, provides a new and deeper community to share ones’ achievements with, masking the surveillance implicitly built into the incentive structure.

A SENSE OF PLACE

This community was the other thing that struck Mayra about her work at Walmart. Mayra thought her work at Walmart was “just going to be a job,” but instead she “fell in love.” For the first time in her life, it seemed, she had found a community of peers with whom she felt she could be herself. “I just fell in love with the people that worked there. And the customers [who] were there.” Before Walmart, “I was a mom. I was home with my kids. I had my kids. I had my husband. But I didn’t really have friends, you know? Just—that’s what I found.” 5

This was Sue Rogers’s experience too—Walmart gave her a community and a sense of emotional intimacy that she had been missing in her marriage. For Sue, like Mayra, the job offered a quasi-family:

I knew everybody there in that store…. Everybody—it was like a big family. Everybody I knew, and we had good times. We had functions all the time for Children’s Miracle Network [a nonprofit that supports children’s hospitals]. We had functions all the time set up. We had Halloween parties where we would be dressed up and go around giving the kids candy that come in the store…. They even have pictures of us doing the chicken dance going up and down the aisle.

Sue found a group of friends at work with whom she spent more and more time. Friday nights they’d all go to the local Applebee’s where they would “sit around and cut out and laugh, you know, have a good time.” She would invite her husband to join them, but, she says, “He didn’t want to go out and do things. He would come home, sit in his recliner, drink his beer, read his paper, and go to bed.” She continues, “It made me feel like he didn’t want to be with me.” They got separated. And it was okay.

Associates see one of their coworkers has a broken car window and within two days collect more than the $300 needed to fix it, treating their coworker to a $25 Applebee’s card, $25 Subway card, $50 gas card, $56 in cash and we paid the $300 to get her car fixed. When Walmart associates die the whole store often grieves. Some stores set up memorials in the aisles; others collect money for funeral expenses; the staff of one store walks together into the parking lot holding pink balloons and casts them, collectively, up into the air.

Coworkers are often literally one’s family. In our survey, 42 percent of respondents said that they had a family member who also worked at Walmart (or had worked there at some point). A third of respondents (33.4 percent) had a family member who worked at the very same Walmart where they worked. And if associates don’t have family at the store now, there is a good chance they might in the future, as romance often flourishes in the aisles. The discussion board is full of stories of people hooking up at Walmart. Workers with workers (I was in electronics [he] was in dairy), workers with customers (thought he was cute he was a customer in my line on reg 7), and customers with customers. In early 2013, the most frequent place that people reported having had “missed connections” on Craigslist—catching someone’s eye, flirting without exchanging numbers, not quite getting up the nerve to ask someone out—was Walmart.6 This was particularly true across the South—Texas, Louisiana, Arkansas, Alabama, Mississippi, Florida, Tennessee, North Carolina. In New York, by comparison, it was the subway; in California, 24 Hour Fitness. For large swaths of the country, Walmart is the place where people are most likely to meet new people. It’s our new public commons, only it’s private.

Before she started at Walmart, Ximena Fields had been unhappily married for over 23 years. She was working as a service writer in the automotive shop at the Walmart in Grand Prairie, Texas [#896], when she met Alfred, who worked inside the regular store: “It got to where he would come…everyday or something like that just so he could come in. I know it was just to come in and talk to me. But, eventually, we would give each other a hug and kiss on the cheek, and then it escalated from there.” She left her husband and she and Alfred began a life together. By the time the students showed up in Dallas, Ximena and Alfred were inseparable. Once they told Louisa about a time they had been in such desperate economic straits that they had sat in the car and squirted ketchup onto saltines for lunch. Louisa remembers thinking it could have been a morose story, but instead they were laughing, tears streaming down their faces.

The overnight shift is particularly fertile for friendship, and more, among associates. The customers are scarce and most of the managers have gone home. Throughout the summer, Harmony, from the Cincinnati team, would spend many late nights in the parking lot of the Cunningham Road Store [#3749] with Frank Brown and Doris Goodman, another couple who had met at work. During one 2 a.m. lunch break they sat in the back of their white pickup, far away from the fluorescent lights of the break room, smoking and playing music out of Doris’s phone. Doris dangled her feet off the bed of the truck while Frank rummaged behind the seat for an old photo from the ‘80s. We squinted at it under the parking lot light and laughed at the state of his hair. Southern Man came on and I blurted out, “I love this song!” Doris nodded. “Neil,” she said, “that’s what’s up.”

At its best, people feel both a sense of individual recognition and community from their peers at Walmart. We can see evidence of this in the ways that associates review their jobs at Walmart on a job site like Glassdoor.com. Glassdoor is a website founded in 2007 where employees are able to anonymously review their employers. It’s like Yelp, but from the perspective of workers. Between 2007 and 2015, more than 9,500 hourly Walmart associates used the site to review the company. Reviews include “Pros” and “Cons,” as well as an overall rating of the job (on a scale from 1 to 5). We used simple text analysis strategies to explore the most common words that workers use on Glassdoor to describe their jobs. The most frequent noun used to describe the “Pros” of the job, by far, is “people.” Among workers as a whole, it’s the “people” that make the difference.

We can take this one step further by looking at the “Pros” nouns that are most strongly associated with higher overall job ratings. The word most highly associated with how much one likes one’s job is “culture,” with words like “environment,” “team,” and “family” close behind. These are the associates who see the store as theirs, not someone else’s. These are the ones who not only can perform the “Walmart cheer” on command—“Give me a ‘W,’ give me an ‘A,’…”—but also know the specific cheers associated with their own stores: “#3261, keep the others on the run!”; “#1823, Hanover is the place to be!”; “#2136, the store that really kicks!”; “#2860, where it’s cooler in Pooler!”

GHOST STORIES

There are associates so connected to the specific histories of their stores that they report on the ghosts haunting the aisles: ghosts who will occasionally push things off the shelves in the backroom when no one is there or pull on a worker’s cart when she walks by the garden center; who will throw tires off their racks in the tire and lube express (TLE) department; who will turn the registers off and on; there’s the girl in white walking past the general merchandise docking bay; the ghost of a construction worker who fell through the skylight during a store’s construction. A woman named Abigail, killed by her husband in a house on the lot where the store now sits, who loves to pick on overnight managers. Especially if they are mean. To believe in ghosts at one’s Walmart one has to believe that the place has a history, depth, significance.

It’s not surprising, then, that some of the ghost stories concern Sam Walton, the larger-than-life founder of Walmart. An associate writes that a voice came over the walkie-talkies one night telling him and his coworkers, “Sam is not happy,” though all the walkie-talkies were present and accounted for. Another associate said strange things started happening at her store only after Mr. Sam had passed, so we like to say that he is haunting us. A few others remark that all the stores are haunted by Mr. Walton, as he is rolling in his grave at what the corporation has become.

Among many associates there is a sense of belonging that comes from sharing this weird, idealized past—a past when Sam Walton was running the show, when Walmart was smaller than it is now. It’s not hard to wrap one’s mind around the myth of Sam Walton, but it is somewhat harder to wrap one’s mind around the fact that the story works. It’s a Horatio Alger story: young, striving entrepreneur with novel ideas and real concern for and understanding of real people lifts himself up from humble origins, never forgetting who he was or who helped him along the way.7 The cult of personality that developed around Walton is supported by his famous sayings, a small sampling of which are:

Appreciate everything your associates do for the business. Nothing else can quite substitute for a few well-chosen, well-timed, sincere words of praise. They’re absolutely free and worth a fortune.

If you want a successful business, your people must feel that you are working for them—not that they are working for you.

Commit to your business. Believe in it more than anybody else.

If you love your work, you’ll be out there every day trying to do it the best you possibly can, and pretty soon everybody around will catch the passion from you—like a fever.

If people believe in themselves, it’s amazing what they can accomplish.

These and a host of other equally vacuous aphorisms are routinely referenced by both disgruntled and satisfied associates in support of their view that Walmart has either betrayed its initial mission or stayed true to it. Either way, many Walmart associates share the same founding myth, and sharing that story solidifies the sense of community that they have, a sense that Walmart is theirs. The weird thing is that this loyalty to Walmart actually extends beyond their store, beyond their colleagues and friends who shop there, to other Walmart stores that they happen to visit. Associates often discuss how Sam would roll over in his grave (Sam is often rolling in his grave) if he saw how rude the cashiers were at some other store, or how messy the aisles were, or how anything was not working as well as it does at their own store. The sense of belonging to something bigger is palpable.

Bethany Moreton links Walmart’s cultural power to its historical roots, which she argues has made the company particularly adept at mixing market dominance with populist morality. Sam Walton built the company out of the Ozarks of northwest Arkansas, a region that, in the late nineteenth century, had “hosted some of the nation’s most vigorous popular protests against huge economic ‘combinations’”; and in the 1920s and 1930s had been swept into a vigorous “antichain” movement against the spread of retail chains from Northern cities. Sensitive to the region’s heritage of agrarian populism, Walton looked for financing locally—entering into “partnerships” with local “investor-managers,” and seeking loans from a large Arkansas bank rather than from New York.8 Even as the corporation transformed itself into the largest employer in the world, it sought to maintain a “populist corporate image”9 of thrift, anti-elitism, and quasi-egalitarianism. Its “Home Office,” which remains in Bentonville, Arkansas, is an assemblage of nondescript buildings about as far from the glitzy “campuses” of Silicon Valley as one can imagine. There, Walmart buyers negotiate with suppliers in unremarkable conference rooms. Its executives are known for flying coach, for renting cheap cars, for sharing hotel rooms, for working out of minimally furnished offices. Staffers at headquarters report bringing pens from home rather than asking the company to buy them; when charging meals to the company they are allowed to tip at only 10 percent. For years Sam Walton would visit stores in his 1975 Chevy pickup truck.10 The message for customers is of the company doing everything in its power to keep costs (and prices) down. The implicit message for associates seems to be one of shared sacrifice—of everyone, from the top on down, stretching every dollar in the name of low prices. That Walmart’s CEO Doug McMillon made $22.4 million in 2017, well over a thousand times the earnings of a full-time Walmart worker earning $10 an hour, is obfuscated by a common, spartan aesthetic. Sam Walton may have been a specter all along. But in many ways this ghost continues to do its work, and Walmart’s aisles—which made us feel small—make others feel at home.

FRIENDS MATTER

Some of workers’ sense of community comes from the simple fact that many Walmart associates, especially those outside the larger urban areas, live in neighborhoods near the stores where they work. And that means that they know their coworkers from settings outside Walmart—because they went to high school together, go to church together, belong to the same clubs, root for the same local teams. Part of this sense of community comes from the fact that the customers they see at their stores are their neighbors and friends. And part comes from making new friends.

This sense of community is strongly associated with how one feels about the job. Seeing customers that one knows from other parts of one’s life; having friends at work; being able to ask one’s coworkers for help—in our survey data, each of these is positively, significantly, and independently associated with one’s job satisfaction, even after controlling for things like race, sex, age, whether one currently works at Walmart, and how long one has (ever) worked there.

Working with one’s friends matters. When Joan Wharton, from the store in Franklin, Ohio, described her daily work, it sounded a lot like a social club: “You looked forward to going in there, because you knew you had fun.” Her coworkers were some of her closest friends—Bonnie would offer the latest pictures of her granddaughter (“She’s so proud of her. She’s so cute”); Linda would be talking about her garden, or she’d be drinking her coffee from Thornton’s and singing; Kitty—“I love Kitty—if it wasn’t for Kitty, I would walk away”; and some of the guys too: “We’ve got Joe there, young Joe. And Noam—oh, Lord. He’s something else!” The days passed easily:

All of us are really close-knit, and we’re all friends. All of us coworkers. We’ve been there for a long time, we all get along. We all have a sense of humor, and we would see what we had to do for the day, and we would all be laughing. We would all talk or holler at each other if we needed this, or we needed that. We would holler, like, an aisle or two over, and cut up, and laugh. And we would all be singing while we worked, or whatever. And everybody helped each other; we would all work together.

Stories about one’s “regular” customers also abound. These stories are often told with a mix of annoyance and pride, the way people complain about receiving too many emails or faculty members complain about having too many students who want to take their courses. An older male associate in the Walmart in Vestal, New York, describes how he can’t be in his store in plainclothes without being identified by his regulars who then ask him for help. He’s considering retirement, but he has two older customers who have made him promise to give them his phone number if he does so that they can call him with questions. A cashier at the store in Oneonta, New York [#2262], tells us she buys her own groceries at Stop & Shop because “if you are a Walmart associate then you are always a Walmart associate and everyone knows I work here.” Her regulars won’t leave her alone and company policy is that if someone asks you for help, even while you are off the clock, you have to “be nice and represent the store.” It was just easier not to go there at all on her day off. An associate writes online that he’s feeling aggravated: I’m here shopping with my wife in regular clothes not work clothes & keep getting asked where stuff is! Hello I’m not on the clock. Let us be! Another, former associate writes that she had stopped working at Walmart more than a year ago and was shopping in my old store yesterday and got asked for help. Others write that customers ask them to help them even when they are shopping at other nearby stores. The consensus seems to be that one is better off staying away from one’s store on one’s day off. But it’s hard to stay away from all retail stores altogether, and one associate’s theory is that when u work retail for awhile they sense it.

Workers may go to such lengths drawing boundaries between their roles as workers and their roles as customers because the boundaries are so blurry. Walmart workers are Walmart buyers, and not only because of the discount card that entitles people who have worked there more than three months to 10 percent off most merchandise, though this certainly helps. Among our survey respondents who currently work at Walmart, 84 percent report doing their own shopping at Walmart once a week or more, and 96 percent report shopping there more than once a month. Among respondents who no longer work at Walmart (and so do not get the discount unless they have a spouse working there), 53 percent still report doing their shopping at Walmart once a week or more, and 80 percent report shopping there more than once a month.

GUNS AND ROSES

It is not unusual to see workers in uniform discussing their schedules or their weekends or their moods with people in street clothes who seem just a little too familiar with the store to be shoppers. At the store in Catskill, New York [#2351], a man in street clothes comes up to an associate and gives her a big hug. A second worker turns to the man and says, “That’s what she needs today.” And then her voice deepens: “I’ll tell you what she really needs.” There’s a fleeting moment of tension—was she talking about sex? So she continues: “I mean weapons. She needs weapons. So do I.” Apparently, the day has not started out so well. The man smiles: “I’ve got weapons!” The associate replies, “Can I borrow them? I’ll bring them back without fingerprints.” The man must be an associate himself—the three know each other, he understands why they might joke about arming up to take on the day. This is not a customer service interaction. Yet these types of interactions—ones that don’t fit the archetype of customer service, but aren’t obviously interactions among workers on the clock—are commonplace. An associate stands in the aisle of the Taylor, Pennsylvania [#4276], store with a mop in her hand, talking about scheduling with three people in street clothes who seem a lot like her family. Another associate at the same store turns into an aisle with a man who must be her boyfriend or husband. They walk down the aisle together, briefly take one another’s hands, and then release them before they reenter the central corridor of the store.

Some customers are friends, some customers are coworkers, some customers become more than customers across repeated interactions over months and even years. And for some people who work at Walmart there is a real sense of pride and satisfaction in the social interactions that make up the workday. James Drake, from a store in Lancaster, Texas [#471], described his own muscular arms as his “customer gun boats” and reminisced about the people from his neighborhood who would come and shop in the store. Chelsea Mays, a cashier from a store in Cincinnati, Ohio, said the customers were the best part of her job: “My customers make me laugh. I have customers, they come in the door to look for me when I come to work, so they can get in my line, because I make them laugh.” Jeffrey Rivers, who worked as an assembler at a store in Texas, also conveyed the closeness he felt with some of his customers: “They say, ‘We’ll come back and we’ll try and find you so you can help us out.’ I help my customers out all the time.” His customers returned the favor—he wasn’t supposed to accept tips for helping people assemble equipment they bought, but his customers would insist:

Every time there’ll be customers I will see, after I get off work, and [I’m like], “I can’t take money for helping out.” But [they say], “You off the clock?” “Yeah.” “Here you go.” They all hand me a little bit of money. I’m like, “Naw,” I’m trying to force like, “Nope, nope, nope, nope.” They, like, drop it, and I pick it up. Hey, me personally, I’m not going to leave money just lay there.

An associate writes that being a cake decorator is her dream job since every time someone leaves with their cake and a smile on their face, it makes the rest of the crap all worth it. Another writes that she had a customer follow her from one store to another when she transferred two years before. A third says that she knows most of her regulars by name—then adds, Its pretty cool actually to have that personal connection with your customers. A Spanish-speaking associate intervenes in a conversation about how there is no one paid to translate at the store: I don’t mind doing it, it feels good being able to translate and speak both. I know my parents struggled a while back and I would have to translate for them and being able to help others is great! An associate in electronics says that he has hundreds of customers that come directly to Electronics just to see me. He recounts a story about the advice he gave a customer about 4K televisions, who told a few friends of his to come see me about TV’s instead of going to Best Buy because I’m clear and concise…. That’s why I’m called Mr. Television.

This feeling of community is distributed unevenly across Walmart workers and Walmart stores. White workers, on average, report having many more friends at work than workers of color, even after controlling for a host of other factors.11 Those who have worked for more years at the store also report having more friends (though one wonders whether this is a cause or an effect of job tenure). Workers of color and workers from poorer families tend to talk to their managers and their coworkers about their personal problems less frequently, ask for help from them less frequently, and work in stores in which they run into customers they know less frequently. The social benefits of work at Walmart are unequally shared.

There are likely two different reasons for this. First, it may be a result of the particular kind of power that Walmart has in certain low-income communities and communities of color, where the company is one of the only employers around.12 In whiter, wealthier communities, the people who work at Walmart are less dependent on the wage (e.g., retirees, high schoolers), have more options, and choose to work at Walmart in part because of the social amenities—friends, customers they know. In poorer communities of color, the people who work at Walmart are more dependent on the wage, have fewer options, and so have to work at the store regardless of whether it is a pleasant social experience or not. Second, it may simply reflect the fact that communities of color tend to be concentrated in more urban areas and as a consequence associates are less likely to know one another, travel further to work, and share fewer overlapping associational foci.

FAIR ENOUGH WAGES?

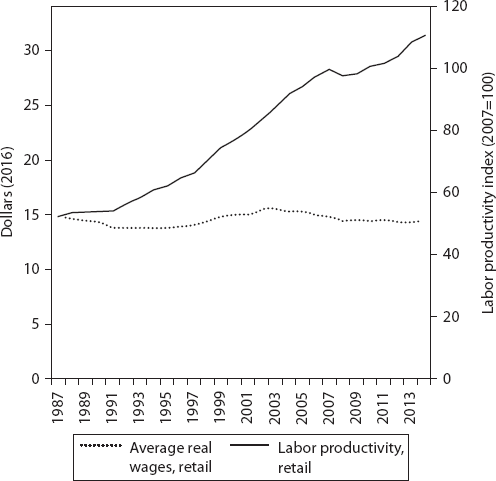

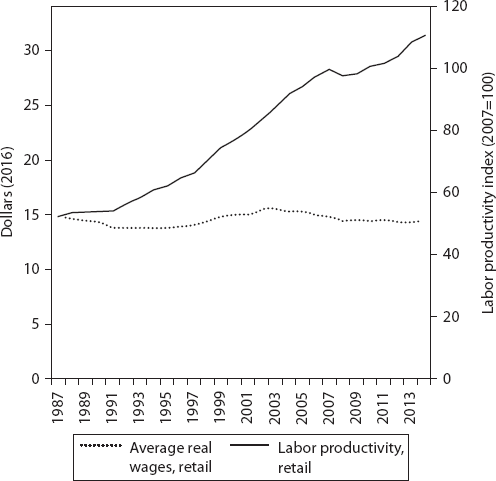

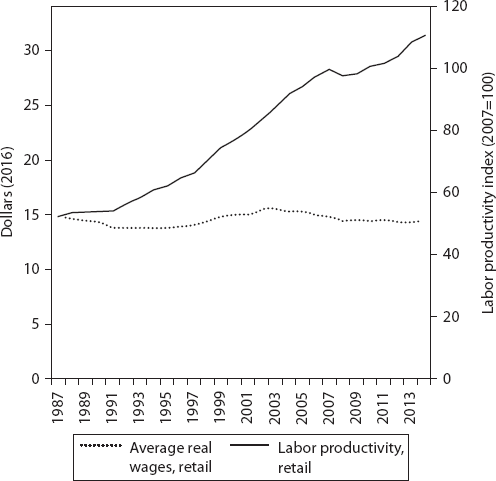

For years, Walmart has been the poster child for the low-wage employer. Really it’s been more than the poster child—it’s the model that has helped set the bar so low for workers across retail and adjacent industries. And it has done so at a time when retail workers have been increasingly productive. Between 1987 and 2014, labor productivity across the retail sector doubled. But average real wages across the retail sector were flat, meaning that workers were not able to claim for themselves any of the increased productivity they were making possible for their employers (see figure 2.1).

Given this fact, it might come as something of a surprise that low pay is not the most common complaint among Walmart employees who post reviews on Glassdoor, among those who participate on the Walmart associates’ discussion board, among the many interviews we conducted with workers at Walmart, or during any of our visits to Walmart stores. This is not to say that people weren’t struggling financially. People were often just scraping by. When Carmen Bond worked the register in Huber Heights, Ohio [#1495], she would often be hungry. “I knew that if I was to buy some food, then I probably wouldn’t have enough for gas. Or I’d probably be a couple of dollars short for rent.” She’d scramble for change in the cushions of her car, then go to the deli in the store and ask them to weigh “62 cents or 79 cents” of something. The vending machine at the store would sell soda for 50 cents. “Water was a dollar. And I couldn’t even afford to buy water. I had to buy pop.” One time her hours got cut so drastically for a couple of weeks that the precarious balancing act was simply impossible: “I had to burden my parents and ask my mom for help. And I felt so small. Like, I felt like I couldn’t do it myself. I felt like less of a person.” It was humiliating to have to turn to others, or even share her hardship with others, so she avoided doing so when possible.

But Carmen and others didn’t seem to place too much blame on Walmart. The outside options were just as bad or worse. When there are no other jobs, then Walmart is a better alternative than not working. As the economist Joan Robinson once quipped, “the misery of being exploited by capitalists is nothing compared to the misery of not being exploited at all.”13 Joan Wharton, from the Franklin store, says, “You just have to suck it up, and just take whatever they dish out to you. Because if that’s the only way you’ve got to support your family, like I said, I was raised: ‘Don’t be no quitter. You just have to suck it up. Just forget about it, suck it up, bitch. Go on.’” Richard Walker, who worked in the grocery at the store in Lancaster, Texas, remembers, “I didn’t go in there saying $7.75 is great. I went in there and said I needed a job, and I took what I could get.” Naomi Adams, who worked inventory at a store in Arlington, Texas, said that there were days she just wanted to walk out, but “I have to keep a roof over my head. So I suck it up and do it.” If there are other jobs they don’t pay much better, and may even be less secure. At least Walmart mostly pays the wages it promises when it says it is going to. In the peripheral job market this is not always the case.

Walmart’s massive profits depend in part on the low prices it pays for workers’ labor. This is something that most workers at Walmart know intuitively but rarely articulate explicitly. Karen Ford might be the exception that proves the rule. A cake decorator in Cincinnati, Ohio [#4609], she was more vocal than most about getting too small a piece of the pie (or cake):

The cheapest [cake] is $7.98…. A quarter sheet now, without a kit, is $14.98. A quarter sheet with a kit is $19.98. Now, for every hour that I work, if they sell one cake, they have paid my wage for that hour. But in the hour that I work, if they sold four or five cakes in that hour for $14.98, they done almost paid my salary [for] a day! You understand what I’m saying?

Karen had overlooked the fixed capital investment that Walmart had priced into the cake and the cost of the ingredients. Some tiny fraction of the electricity, debt payment, rent, the congealed labor and materials embedded in the making and maintaining of the physical store, the labor of greeters (security guards), and so on, all of it ends up in the cost of the cake. So does the cost of the flour and eggs and sugar. Still, all of those elements don’t come up to $14.98. Karen was right that she was making money for Walmart.

Meanwhile, Karen was barely making enough to scrape by. She would put $5 worth of gas at a time in her car. She would sometimes go without meals so that her kids would have enough to eat. And she believed strongly in the ideal of “an honest day’s work for an honest day’s pay…. If I’m working, then I feel like I have the right to work and live. You know what I’m saying?”

But even Karen, who had partially reconstructed the labor theory of value as it pertained to baked goods, in the next breath was quick to qualify her criticism of Walmart pay.14 She added, “They don’t owe us anything, you see what I’m saying? You can’t be ungrateful, because do you know how many people it is that don’t have jobs? It is a job. And you know what? I’m going to tell you something. No one is indispensable. At Walmart, they’ll get rid of you, because there’s four or five people ready to take your place.” It was clear to Karen that she was not making enough. But it also seemed clear to her that she had to be grateful for what she got. It was difficult to blame Walmart, anyway, for the fact that other jobs paid next to nothing, and Walmart was the best she could do. As Paul Lee from a Chicago store [#5645] put it, “people are so desperate to have a job that they’ll work for almost anything just to have food on their table.” Not only that. They’ll work for almost anything and keep relatively quiet about it.

This is a sleight of the invisible hand of the labor market: people are free to leave Walmart anytime. The pernicious psychological flipside to this exit option is that it implies—even for workers themselves—that those who stay are choosing to stay. They are accepting the terms of the deal: therefore, Walmart doesn’t owe them anything. For the typical American worker, the labor market is an abstraction, a weather pattern. Getting mad at Walmart for its low wages when low wages are everywhere is like getting mad at the rain.

PETTY DESPOTS

So where do Walmart workers direct their frustration? Toward the real people who make the abstraction of the labor market tangible: store managers and comanagers and assistant managers. They are all identifiable. They have faces, names, walkie-talkies strapped to their belts and collared shirts that distinguish them from everyday associates. While the wages and benefits one is offered may feel like the result of distant and uncontrollable forces, the manager is standing right in front of you. And while Walmart’s low wages may have different significance for workers coming from different situations, the experience of a manager’s arbitrary authority—the experience of the Walmart regime—is common.

Returning to the Glassdoor text, while workers identify the “people” at work as the best part of the job, the most common noun workers use when describing the “Cons” of work at Walmart is “management.” The “Cons” nouns most strongly associated with liking one’s job less are “respect” and “treat.” In other words, among those who like their jobs the least, their unhappiness is due to the lack of respect they feel at work; the way they feel they are treated.

Take Joan Wharton, who—you’ll remember—had previously worked at AK Steel for $20 an hour and now worked at the Franklin, Ohio, store for $9. Joan discussed the nearly 60 percent drop in pay almost in passing. The difference she most noticed between working at AK Steel and Walmart? The management. With the union at AK Steel, “there’s union contracts, union rules, union representatives. Things that you had to go by, that the workers and the employers all had to go by.” If you were treated poorly by a manager, you could “go talk to a rep.” At Walmart, though, managers “feel like they can step on anybody they want. They feel like they can talk to anybody any way they want. They can make you do anything they want.” There were no boundaries to what managers could ask of workers at Walmart. “They can make you do 20 jobs and give you your nine dollars.”

Managers at the Franklin store didn’t like the camaraderie that Joan and her friends had established. So they ended it. “We’re not allowed to sing anymore,” Joan says. “We’re not allowed to holler. You know, ‘Hi, how are you doing?’” Instead, she says, “We’re to go where we’re supposed to go, keep our mouths shut, do our work, and get it done now.” Now, Joan reports,

All the close-knit family that we’ve had in there, and all the helping each other out, and the enjoyable days of going in there and being with, like, our little family together, doing our thing? It’s over. It’s like being in a jail or something. The management has literally sucked the life out of everybody in there.

Workers weren’t even permitted to banter with customers: “You’re talking to customers, laughing with customers. They don’t even like that.” They weren’t allowed to call customers “hon” or “sweetie” either. “You have to watch everything you say, every move you make, everything you do in Walmart.” The story at Franklin is echoed elsewhere, not everywhere, but the experience of having management suck the life out of a store is common enough. Willie Bell, from the store in Lancaster, Texas, said, “Walmart now is ran on intimidation…If you open your mouth, you won’t get fed. You keep your mouth closed, and you go with the flow.”

Like Joan Wharton, Mayra Rodriguez from the store in Paramount, California, had loved the community she found at the store. But she also soured on the job, because she felt as though managers were intent on breaking up the second family she had established:

When you work there, you’re not just an associate. The person that works next to you, they’re more like your aunt, your cousin, your brother, your sister. So, when you get somebody gone, you’re breaking up a family. And then when their income is affected, you’re breaking up another family.

Managers seem to think that when workers have fun at work—when they talk, holler, visit each other’s aisles—that time otherwise spent on productive activities is being wasted. They also seem to think that informal friendly relations among workers create the possibility of a countervailing moral community that might threaten their control over the flow of work. This may be particularly true in retail where, other than the flow of customers and products into and out of the store, there is no structure that organizes labor. The significance of this absence—the absence of an assembly line, of a fixed structure of activities—for the exercise of arbitrary managerial authority is not trivial. Coupled with a scheduling system that is designed to make every minute in the store exactly the same with respect to the staff/customer-material ratio, one can see why management sometimes uses the rhetoric of customer service to break up friendship groups that emerge spontaneously.

And such was the case at Paramount, where soon enough a new management team came after Mayra. She started getting “coachings” from her supervisors that she felt were entirely without merit. Mayra never understood why she was disciplined. Her theory is that they were trying to get rid of her “because I was making more than some people.” She says, “I was fenced in. And I didn’t see it coming. But by the second coaching, it was already—something’s up. Third one, ‘Oh my God, what did I get myself into?’ And then, the last one, which was like, ‘Really?’” So she lost her job.

Mayra might have been unlucky. The new management team went after her quickly and hard and she was unable to outlast them. One thing that Walmart employees know is that managers are regularly moved from store to store. This means that if they can get a quick assessment of the despotic qualities of new teams rapidly enough they can “keep their heads down” for a year or two (which, granted, is an incredibly long time to have to experience the unbridled control of anyone) and outlast them. When this happens, new management teams enter stores where the average worker has worked significantly longer than they will anticipate being there. Like political appointees to cabinet positions, who have to figure out whether they can move potentially entrenched civil servants (the answer to which is “yes” if they are smart, and “no” if they are hacks), these management groups often have to deal with equally entrenched worker communities. And this fact tempers, for many, what changes they seek to put into place.

REPETITION IS MORE COMMON THAN REDEMPTION

Because most managers are male and most associates are female, the destruction of a shop-floor community can replicate the isolation that women have historically experienced in the transition from family of origin to family of destination. For some women, the community that had originally felt like such a nice escape from the banality or brutality of home life started to feel all too familiar—a home away from home, but not in a nice way. This was, at least in part, by design. At the company’s founding, Sam Walton had fostered a culture that reinforced the ideals of the patriarchal family from which the women of the Ozarks came, so that Walmart would be understandable to the communities into which he sought to expand. Male managers, often much younger than their female counterparts, would look after and take care of the women at the registers and in the aisles.15 Sex discrimination was in the company’s DNA. In Dukes v. Wal-Mart Stores, Inc., the largest civil rights class action case ever filed against a private corporation, women recounted how they began to confront their managers about being passed over for promotions in favor of less-experienced men. They would sometimes be told explicitly that the men had families to support; that the men were out to make careers at Walmart while the women were not. Giana was offered a $0.40 raise to become a department manager; she remembers many of the men getting $1.00. The plaintiff in the Dukes case argued, “Wal-Mart has been living in the America of thirty years ago.”16 The gendered hierarchy within the store also meant that management’s domination often took the form of men treating women badly. Rose Robinson, from the Walmart on the South Side of Chicago [#5781] put it simply in an interview: “It’s things that I seen in that store that hurts. And you know, coming up, I was hurt enough. So, then a woman of sixty-five now, I’m not looking to get hurt again by nobody.”

The awful boss is a cliché, the stuff of sitcoms and movies—think The Office or The Devil Wears Prada. The usual setup in such movies is that some people are just nasty and/or incompetent and that suddenly one morning they are “the boss”; and life is hell until they find redemption. Real life is different from the movies (it is more similar to sitcoms). First, repetition—which is the premise of the sitcom—is more common than redemption. In the sitcom the nasty boss is nasty until the show is canceled; in real life, bosses don’t often find redemption, they are just transferred (or even promoted). Labor contracts and the laws that undergird them set some boundaries on the kinds of requests that bosses can make of workers and the avenues through which workers can seek remedy. But those boundaries are clearer for demands that involve the allocation of one’s effort to satisfy the personal needs of bosses—doing their laundry, running their errands, and so on. For demands that are cast in the language of the job, of furthering organizational goals, the boundary between fair use of labor and exploitation is much blurrier.

THE INCOMPLETE CONTRACT

Absent a collectively negotiated labor contract, with respect to actual work in the organization (as distinct from personal services), there are almost no limits to what employers can and do ask of those low-wage employees for whom there is no serious exit option. As we will discuss in more detail in chapter 3, this may be especially true in the retail sector, where little structures the flow of activities other than the movement of people and goods, which—given the ways in which schedules are structured—is effectively randomized. The experience of working in a setting where there are few rules governing what one can be asked to do is translated back as “being in a jail,” as Joan Wharton (whose husband is in prison) put it.17 Comparisons to prison and slavery are deployed with particular regularity by black men at Walmart—Trevon Wilson, from the store in Forest Park, Illinois, said the company “wants you to be in jail” or “on the sale block.” Randall Stewart, from a Chicago store, said a manager spoke to him as though “if you walk away from him, he’ll hit you with a whip.” Owen Taylor, from a different Chicago store, said Walmart treated him “like a slave without the shackles.” Just as, for some women, Walmart comes to feel like the abusive spouses they sought to escape, for these men Walmart feels analogous to the institutions that historically have defined black American life.

Such a sense of powerlessness vis-à-vis one’s employer is a reality for many at the bottom of the U.S. labor market—a phenomenon Elizabeth Anderson describes as “private government” in her book by the same name: “Private governments impose controls on workers that are unconstitutional for democratic states to impose on citizens who are not convicts or in the military.”18 The political scientist Alex Gourevitch notes that, since most labor contracts are written in vague language, they give the employer “residual authority to specify those undetermined terms and conditions of employment.”19 This indeterminacy is true across a wide range of employers but is presumably the most extreme at places in which workers have neither collective representation nor bargaining power at the individual level: places, in other words, like Walmart. Gourevitch continues,

Disputes about “the job” can be very wide-ranging. Are the political views, Facebook postings, off-hours recreational activities, and health conditions of employees a reasonable basis for being fired? Is it part of the job to be required to pee in a cup for drug-testing but also be denied bathroom breaks? Can a worker be denied the right to read a newspaper during lunch? Should employees have to listen to the political opinions and participate in political activities of their employers, or is this irrelevant to the employment relationship?

Anyone who believes that constitutionally protected rights like free speech are protected at work need not work too hard to be disabused of this idea. In the aisles of the Walmart in Catskill, New York, on the weekend before the 2016 election, two young white men were pushing a cart of baked goods, laughing with each other about how one of their coworkers had called out sick—“I bet she’s out there getting another vote for Hillary,” one said derisively. We walked up to try to join in the banter, but they clammed up. “We’re not allowed to talk about the election with customers,” they said sheepishly. This may not be all that surprising, but it was a striking contrast with the experience we had the next day at a small store selling “authentic Polish pottery” in a small development near the Walmart in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania. Here, when we mentioned we were from New York, the owner was quick to respond, “Oh, no! That’s a bunch of liberals over there. We’re Trump supporters here.” Polish Trump supporters who had been immigrant coal miners—now that the coal industry had declined—were selling their immigrant pottery. When we told him we were not going to buy any of his authentic pottery because he would then give the money to Trump, he sort-of-jokingly threatened that his two friends Smith and Wesson would help us get out of the store and that the last New Yorker who came through was lying behind the counter. The owner of the strange authentic Polish pottery store was able to own his strange political beliefs. Associates at Walmart have to be clandestine about them.

Workers’ health, formally protected by law, is often not protected in practice within private governments like Walmart. For instance, by law, employers are required to provide medical care for those injured at work. In practice, though, large employers like Walmart are permitted to self-fund their workers’ compensation programs rather than pay insurance premiums to an outside insurer. In these cases, the company has a particular incentive to keep claims down—to contract its medical work out to those who will look out for the company’s bottom line. Among those Walmart workers who took our survey, 38 percent reported having been injured on the job. Of those, only 12 percent report being covered by workers’ compensation. It is hard to know what this means precisely, since many injuries wouldn’t be serious enough to warrant workers’ compensation. But in Colorado, Walmart settled a class action suit filed by approximately 7,000 employees alleging that the company had conspired with a subsidiary to limit medical care to save on costs.20

Work at Walmart can be hard on the body, yet getting sick and missing work while working at Walmart is often grounds for punishment—again, at the discretion of management. The formal attendance policy has been changing so rapidly in recent years that many associates are unclear about what it is at any moment. It does not help that Walmart historically has regulated access to this information—according to one report, many associates were only able to access company policy while on the clock and were told that their viewing of company policy was itself being logged and tracked. 21 This keeps people unsettled, on their toes, unsure of whether or not they can safely get sick so they err on the side of attendance at all costs; it also lets managers make decisions by fiat. When workers are in the dark about formal rules, managers are able to enforce them (or not) at their whim.

Anthony Thompson remembers that in order to avoid “points”—given for unexcused absences—he would do his two-hour commute to Forest Park, Illinois, even when he was “sick as a dog.” On these occasions his manager would often make him work his normal shift in the bakery for at least four hours before allowing him to go home. Trevon Wilson had worked at the same Walmart in Forest Park for five years when he began to feel unwell: “It got to the point where I was throwing up every day, and I was on the register throwing up, and they kept telling me I couldn’t go to the bathroom.” Ultimately his supervisor began sending him home, since “they said I couldn’t spend my shift in the bathroom.” He went to the doctor, where they diagnosed him with severe anemia: “They were, like, ‘You were going to work like this? We’re surprised that you even had the strength to lift your head off a pillow.’” By this point he was too weak to go back to work and kept calling off his shifts for about a month. “Then they just stopped putting me on the schedule. They didn’t call me to see, ‘Are you okay? Are you still alive?’ or anything. They just fired me.” He received a letter informing him that he was no longer employed. “And then I called their corporate office, and they said they didn’t have to notify me.”

There are countless stories of workers and former workers that echo Hunter’s experience. Just to pick one: Giana King was proud of becoming the department manager of the health and beauty department in the Walmart in Crenshaw, Los Angeles, after only six months. Giana would now come in overnight to rearrange shelves for new items, do maintenance jobs as they came up, and help to schedule the eight associates below her. For her troubles she got a 40-cent raise. At the time, though, she felt “just having that manager status on my résumé kind of made up for them not giving me” more. She pressed on even as they cut the number of associates who worked under her, first to six and then to four. “So I found myself doing double shifts, coming in overnight, trying to make up the work that my opener left so the closer wouldn’t have too much on her. And I end up pulling my shoulder, have a rotator tear.” When she went to her supervisors about the pain in her arm, she got little sympathy. “Every manager that I went to basically told me [there was] 100 people waiting in line for my position. And if I couldn’t do it, step down and somebody else would.” So she kept going. One day she went to reach for a bucket of “go-backs”—the products that people had taken off the shelves but decided not to buy—and “as I was bringing it down to the floor, my whole left side just pulled. And all I could do was yell.”

Her pain having spread to her neck and back, Giana went to one of Walmart’s contracted workers’ compensation doctors in Los Angeles. The doctor’s office told her that they weren’t authorized to talk about anything other than her arm. So she hired her own workers’ compensation attorney. And then, she says, the company really “started treating me like crap. Like you’re broken. You’re a throwaway paper plate or something.” She needed major surgery.

Adding to the complication of having to lose wages if one is hurt is that injuries don’t just impact one’s own pocketbook—they can impact the pocketbooks of all the workers in the store through the store’s bonus policy. Walmart gives out quarterly bonuses to associates at each store; and stores that have no compensation claims, no injuries, are allocated more money. So when a worker contemplates reporting an injury, in the back of his or her mind is the fact that a claim might hurt his or her coworkers.

Thus the soft moral authority of peer sanctioning works to keep Walmart employees “healthier.” The system has some other “benefits” as well, one of which is to heighten Walmart associates’ intolerance for customer behaviors that appear to put the store at risk of not preventing a “controllable” incident from occurring. An associate from Indiana sees a kid riding a bike around the store. She intervenes. The mom gave me a hard time but that’s my MyShare if she hits someone with it. While the bonus system may incentivize workers to strive for higher store-level profits, it does so without distinguishing between different kinds of costs. From the perspective of an associate wondering about why her MyShare bonus is so low this quarter, customer theft is equivalent to coworker injury.

While Walmart escapes some of the costs of worker health through such inside health-care provision schemes and peer sanctioning, the real savings come from workers who come to work sick or hurt because they can’t afford not to. One writes that she had to leave work on Sunday because I was coughing up blood. She went to the ER and learned that she had pneumonia and had bruised her ribs from the coughing. But she went back to work—in the produce section of the grocery department—with an ace bandage around my ribs because I can’t afford the points.

Jasmine Fourzan, from the Walmart in Lakewood, California, holds Walmart managers responsible for a miscarriage she had in 2012. “I’m sure, without a doubt, it was because of Walmart, because they made me work in the freezer and then the dairy, where the temperature is really cold, and I was lifting heavy boxes and pulling pallets.” Jasmine’s miscarriage fits a troubling pattern of miscarriages among Walmart workers, many of whom say they have been denied requests for light duty or other accommodations during their pregnancies.22 Mary Washington, from a Walmart in Chicago, was pregnant and working the overnight shift when she realized she was bleeding. She told her supervisor that she needed to go to the hospital, but relates that “[my supervisor] wouldn’t let me go. I had to work the next nine hours.” So, she says, “I worked the next nine hours, because I was afraid that if I walked out, that I would get fired.” As her pregnancy progressed, she stopped being able to do the heavy lifting required of her as a stocker in grocery. But she felt like she couldn’t tell her managers. Instead, “behind the manager’s back,” she would get help from her coworkers who “noticed that I was struggling.” Her one other small act of resistance during this time was to wear a jacket when she was working in the freezers (“I’m anemic and I’m on medicine for it”), though her manager would chide her about breaking dress code nearly every day. Rose Robinson said that, in addition to Mary, three other coworkers from that same store had miscarriages on the job.

HAVING NO MONEY MAKES “RANDOM SHIT” HAPPEN MORE OFTEN

As of this writing, regardless of pregnancy or illness or family emergency, Walmart does not accept doctors’ notes as excusing absences. Sick time, vacation time, and holiday pay are all considered interchangeable “paid time off” (PTO) that employees earn in proportion to the hours they work. Associates with different levels of seniority have different exchange rates—a new employee has to work 17.3 hours for an hour of PTO, while an employee who has been at the company for more than 20 years has only to work 6.8 hours. For a recent hire to take off one 8-hour shift for any reason without disciplinary repercussions, she would have to have worked 138.4 hours in advance. At first hire, then, full-time Walmart workers get about 15 days of PTO per year.

For workers without small children, for workers with another earner in the household, for retirees who may have paid off their mortgage, fifteen days off can work fine—maybe feel downright generous. One associate on the discussion board wrote, It amazes me that people are fired for [poor] attendance given how many days off are allowed. Another writes, Be responsible. Show up to work. A third says, [I]f you miss 9 days in 6 months or 4 days in your first 6 months, MOST employers are going to let you go. It’s not just Walmart. And that is likely the case.

But the context created by minimum wage jobs is anything but stable and the capacity to absorb the kinds of shocks that routinely occur in all of our lives (a kid gets sick, the dog is picked up by animal control, the plumbing needs repair, the car needs service) without resources is extremely limited. And if the PTO balance is empty, an illness or family emergency can quickly lead to points (demerits for adults, as one associate puts it) that can in turn lead to coachings23 and eventual termination. Every absence is a point; a no-call/no-show is four points; being more than 10 minutes late to work (or leaving more than 10 minutes early) is half a point; more than two hours late (or early) is a full point (same as an absence). Associates who have been around more than six months get nine points in a rolling six-month window before they are terminated; for new hires (those within the first six months of employment), four points leads to termination.24

It is more complex if, as is often the case, there is no other adult in the household able to help. And when you live at or near the minimum wage it’s just a fact that more bad things happen. The car you rely on is older and less reliable; the housing stock you live in has an older furnace, older plumbing, and less insulation. If babysitters are too expensive or are unreliable because they live in the same situation you do, if taking the car to the shop means that you have to take a two-hour bus ride and that means your kids have to get themselves to the bus stop on their own, if the subway stops inexplicably for 20 minutes, if gunshots kept you and your kids up all night, if anything happens, the absence of resources means that the chances that you will be late or need to miss a day are high. Random shit happens; it just happens more to poor people than rich people. And when it happens, it is more devastating.

When the checking account has $17, or $5, or $3.82, or $0.76, or $0.32, or when there is no checking account to begin with—there is not a lot of give. Even one of the associates who chastised others for missing so much work returns to admit that she thought the company should accept doctors’ notes: I ended up getting the flu for the first time in my life within my first 3 months at Walmart. Not just once but TWICE! I was so afraid of getting fired I worked with the flu. I thought I was dying!—Actually I remember wishing someone would just kill me. In my case, and the case of others in a contagious condition, Walmart’s management should make that exception. Going to work with the flu is a surefire way to get one’s coworkers sick, not to mention one’s customers, whose interests are better served by a healthy workforce. A woman reports that her coworker in the deli had been extremely sick when a customer asked her why she did not go home instead of sneezing on all the food. She responded that she would get in trouble, and—when the customer reported the interaction to the store manager—the employee was disciplined for having told the customer about store policy.

The heterogeneity of experience is staggering. There are more than a million people working at Walmart. Every day thousands of kids get sick, thousands of cars break down, hundreds of people experience a death in their families, hundreds of pipes fail, and countless public transportation routes are unexpectedly delayed. In some Walmarts, managers seem to notch their belts with strict enforcement of the rules. But if all managers worked to rule, forced turnover would likely be higher than it is and the PTO system would collapse under its own weight. And the formal equivalencies—the exchange rates between hours worked and hours earned, infractions and points, points and consequences—belie the discretion that managers have to override the bureaucratic rules when they want to.

This disjuncture between the formal policies and the everyday practices of managers—the fact that managers can choose to look the other way—is what creates the experience of interpersonal domination among workers, the feeling that their managers are the rulers of little fiefdoms.

Not all managers are monsters. Alongside the stories of people being fired for having pneumonia and [being] in the hospital for a week are stories of managers looking out for their employees. A woman who had problems with blood pressure was told by her assistant manager that if I really needed to go she would take care of it. The manager also allowed her to take an unscheduled break: I did that and was able to make up the day without points. One associate from Missouri tells the story of a market manager who, upon hearing of an associate’s uncharacteristic absence, feels worried enough about her to drive to her house, knock on her door, get in touch with the police when she doesn’t respond, and discover—after breaking down her door—that she had fallen and broken her hip. He then sent our two assembly guys over to fix her front door out of his own pocket.

But this is not the point; managers’ capacity to make life miserable or tolerable for associates—not their actual use of this capacity—is what defines domination. Even stories of managers letting workers off the hook, or of higher-ups going the extra mile, reveal as much about managers’ power over workers as they do about their generosity. A manager does not have to ask an associate for permission to take care of a health problem (though she may have to ask someone above her); an associate would likely never think to break down the door of a manager’s home.

THE CAN DRIVE SUMMARIZES EVERYTHING

The Internet exploded just before Thanksgiving in 2013 when it was revealed that the Walmart in Canton, Ohio [#5285] was holding a canned food drive for its own employees. Signs attached to the tablecloths on which the bins were placed read: “Please Donate Food Items Here, so Associates in Need Can Enjoy Thanksgiving Dinner.”25 The obvious, and troubling, implication was that Walmart workers were paid so little that they needed food assistance in order to celebrate the holiday.

The can drive has an ongoing, if less well known, equivalent in the form of the Walmart Associates in Critical Need Trust, a fund that—according to its tax filing—“provides monetary support to associates or their dependents when they experience extreme economic hardship due to situations outside of their control.” During the fiscal year ending January 31, 2013, according to tax records, the fund provided over 14,000 Walmart workers with cash assistance averaging just under $1,000 each. That is $14 million, or 87 percent of the salary of Walmart’s CEO that year. The largest contributor to this fund: Walmart associates and managers, who contributed approximately $5.3 million to help their fellow associates.26

Like the canned food drive, Walmart’s fund for its neediest workers likely wouldn’t be necessary if Walmart didn’t put people in such desperate straits to begin with. And the process for accessing the funds was a little humiliating, wrote one employee. An associate writes that her husband just passed away and she is trying to get help with cremation expense. She went to the store manager, who told her that the fund was for people behind on their bills, but that funerals weren’t considered critical need. Another responded that she was able to use it once for an electric bill but had to go through a lot to even get it, I don’t think it’s worth it. It finally went through only after she sat in the dark too long. Another says that she [d]idn’t get it when I needed it after hip-replacement surgery, and another says that she was denied and that I don’t think they approve it at my store. As with schedules, shifts, promotions, the system is formally rationalized but no one really knows how it works, so those who do not benefit feel as if the beneficiaries had it rigged from the start. It is very unlikely that they did. The outcome is an expression of the fact that when Walmart does look after its associates, it is often through a framework of altruism rather than one of reciprocal and universal rights and obligations.

One associate writes how happy she is that her assistant manager gave her a Christmas card with a lottery ticket. Another writes that her store manager sent out Christmas Cards to each employee and personally wrote Merry Christmas and signed his name. This makes her love [my] store. Another responds, These kinds of posts make me happy and sad…I’m happy for you, but sad that our store doesn’t do stuff like that. Expectations are low: people are genuinely grateful for the manager who gives a little spare change out of the Critical Need Trust when one’s wages aren’t enough to keep one’s lights on, who gives a card and a pat on the back at the end of the year, and who provides a good meal in the break room when one is working on Thanksgiving.