BOUNCING BALLS

Kevin, the Summer for Respect participant with the polytropōs tattoo, walked into the Walmart in Franklin, Ohio, for the first time on June 11, 2014, like any other shopper. His strategy when he was getting a feel for a new store—one he had learned from Robert, his supervisor at OUR Walmart, the organization we were working alongside—was, at first, to interact with workers in ways that preserved some ambiguity. He wanted it to seem like he could be just a shopper, or someone looking for work, until it was clear that he might have a sympathetic reception when he broached the topic of organizing.1 One tactic was to ask an employee for something that Kevin knew Walmart didn’t carry, which would give him time both to observe the worker and develop some basis for further discussion. In electronics, for example, he’d ask if they had a copy of Stanley Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut. They never did.

On that first day at the Franklin store, Kevin met Matt in the electronics department, and asked him for movie recommendations. According to Kevin, Matt displayed his expertise about such products by meticulously going through what he thought of each movie on the shelf I had pointed to (it appeared as if he’d seen them all). Matt seemed like a movie expert, which gave Kevin an idea for how to move the conversation forward: “Man, you really know what you’re talking about,” Kevin remembers saying, “I hope Walmart pays you enough for the great service you’re providing here.” When Kevin asked Matt what he thought of his job, Matt answered that he generally liked it but that there were a lot of people in the store who didn’t. The conversation ended quickly, and Kevin left for the day.

Four days later, Kevin came back. Kevin thought that Matt seemed a little suspicious of him this time, although this seems unlikely given how many people the average worker interacts with on the average day. Either way, though, Kevin merely gave a friendly wave and walked on by. Instead, he began to talk to Jenny, another worker in electronics. This time he cut to the chase more quickly, explaining his role as an intern with OUR Walmart. She had evidently been very confused as to why I was asking so many questions about what it was like working at Walmart, so to hear that I was an organizer made a lot of sense for her. There was almost a sense of relief on both of our parts: for her, she knew I wasn’t some weirdo and that I was asking her such questions as part of my job, and for me, I knew that she wouldn’t snitch on me and that she was down with the cause. Jenny was frustrated by many things about her work: they never had enough staff; her schedule was unpredictable; she had job responsibilities that did not match her pay.

While Kevin was speaking with Jenny, Matt came over, this time complaining about his exhaustion from having had to push carts in the parking lot. The three talked briefly. Talking in a group of three had its advantages and risks. On the one hand, problems that might be experienced as individual could now be recognized as collective. And a triad is a group in a way that a dyad isn’t, so talking in a small group can create an experience consonant with the organizer’s argument about the benefits of solidarity. As Harmony, another participant on the Ohio team, put it, “I personally liked it when I could talk to workers together, because they would feed off each other. And it felt more like I wasn’t talking at them and they were talking to each other.” Those were the advantages.

On the other hand, a group was more conspicuous to managers—while customers would interact with individual workers all the time, it was uncommon for a customer to interact with more than one worker at the same time. So Kevin kept the interaction brief, asking Jenny about her next shift so he could touch base with her again. Before the interaction ended, Jenny mentioned that Kevin ought to speak with Gerald in the photo lab, a suggestion that Matt chuckled at. Evidently, Gerald was quite opinionated about Walmart and wasn’t afraid to run his mouth about the store. When Jenny described Gerald, Kevin recalls, she spoke with both an air of amusement and pride, as if he were the voice of their store.

Bob Moses, the civil rights leader who helped to spearhead Freedom Summer, was once asked how to organize a community. He replied:

By bouncing a ball…. You stand on a street and bounce a ball. Soon all the children come around. You keep on bouncing the ball. Before long, it runs under someone’s porch and then you meet the adults.2

This imagery is profound in its simplicity. Bob Moses’s suggestion was that processes of social interaction and relationship formation are central to processes of collective action. This is different, in important ways, from saying that existing relationships and networks are important to social movement success—a point that is also important but is more widely recognized in social movement scholarship. For Moses, organizing was about embedding oneself strategically within existing social networks to help reshape these networks around collective goals. This is what the organizers in Mississippi tried to achieve in 1964. And this is what doesn’t happen when one just “makes contact.” To build organization, one needs to identify existing networks, work within them, and turn them. People are embedded in all sorts of quasi-groups, latent pieces of social structure that might be activated to achieve collective ends.3 The ball running under the porch might allow one access to a quasi-group of conversation and meal sharing. And embedding in such quasi-groups may lead one to those more formal organizations that bind people together. By the time we visited Kevin and his teammates in Ohio in late July, Kevin could often be found sitting next to Gerald and his coworkers while they took their breaks at the Subway in the Franklin store, Gerald leading informal meetings on various workplace (and non-workplace) issues, with Kevin taking notes alongside.

Kevin had been trained by Robert, a tall, gangly, tattooed white guy in his early 30s, with a long hair and a beard, who had more than a passing resemblance to the gigantic statue of Jesus that dominated I-75. Robert, in turn, had been trained by the leaders of OUR Walmart. Kevin would find out through his interactions on the shop floor what these other leaders already knew, something we discussed earlier: among those who work in low-wage service jobs today, wages and benefits are often concerns secondary to the sense of disrespect they feel from those who wield authority over them.

The Organization United for Respect was not just a catchy acronym. Before OUR Walmart’s founding in 2010, the organization’s leaders had undertaken their own research process to better understand the concerns and hopes of Walmart workers. Through focus groups, online surveys, and one-on-one conversations with workers around the country, they landed on “respect” as a unifying theme.4 Indeed, the language of respect has been shown to be effective across many of today’s organizing campaigns.5

The problem was that, even as some of today’s labor leaders—like those at the helm of OUR Walmart—understood the importance of organizing the unorganized and recognized the importance of respect as central to this organizing vision, they did so within bureaucracies that (with a few exceptions) did not easily create the social conditions within which workers could experience the respect and sense of community that they felt was missing from the job.6

UNIONS ARE JUST CORPORATIONS TOO

Rather than making a pitch or delivering a message, Kevin was quietly familiarizing himself with the social networks of the Walmart in Franklin, Ohio. Eventually, though, he would have to discuss OUR Walmart and what it stood for, which meant he would have to frame the organization’s program in a way that aligned with the concerns he saw percolating up from the shop floor. It’s important to get the message right, that is, to align the organizational vision with what is happening on the ground. And as a consequence, something is often lost in an organization’s attempt to control the message.

One day, the members of the Chicago team—and others associated with OUR Walmart at the site—watched aghast as staff from the UFCW handed prewritten speeches to Walmart workers to deliver as their own for a rally. According to June, “You say you’re a worker-centered movement. But then you’re writing speeches for them…I didn’t like watching that at all.”7 Beth felt like “an organizer should be there to bring out the power in the workers.” Instead, she thought, “A lot of times I think an organizer acts in a lot of other ways [like] the bosses act that are problematic.” She went on, “Talking it out with my teammates, [I realized that] unions are businesses.” Jordan went even further: “[A union is] just a fucking corporation, basically. It’s very business-oriented. You know what I’m saying? It’s about efficiency, and numbers, and blah blah blah.”

The idea that unions are just corporations—that they just care about their own bottom lines, their member numbers, and the salaries of their staffs—is not uncommon. It’s a false equivalency that employers have been touting for decades, but it resonates well enough with some workers’ experiences of unions to have an impact. And this image, fair or not, is at least partly responsible for labor’s precipitous decline.

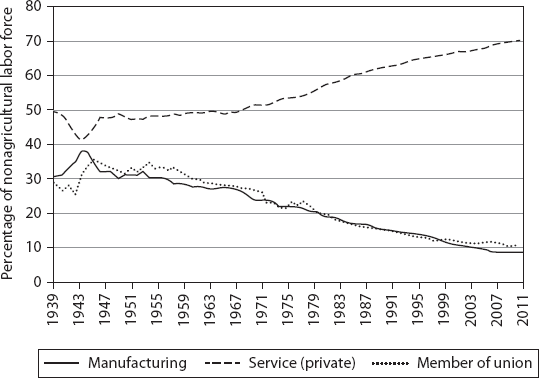

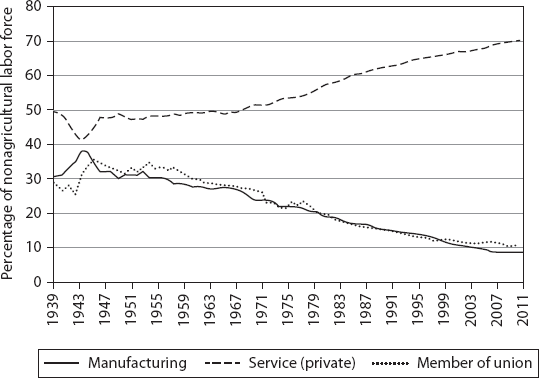

Of course this is not the whole story. The decline of manufacturing and rise of service-sector employment in the United States has transformed the labor market, and this transformation is also partially responsible for declining rates of unionization, since unions have traditionally been most prevalent in manufacturing. Figure 4.1 shows the percentage of workers in manufacturing and service-sector jobs between 1939 and 2014, as well as the percentage of workers who are members of unions. The declining percentage of union members closely tracks the decline of U.S. manufacturing.

Yet neither is the decline of manufacturing in the United States a sufficient explanation for declining unionization. Other countries have experienced declines in manufacturing while sustaining high rates of unionization.8 Moreover there are no really good reasons that rates of unionization in the service sector remain so low. Many aspects of the service sector would actually suggest the opportunity for greater, not lesser, union penetration. On the surface, service-sector workers have some sources of structural power that are absent in traditional manufacturing contexts. Consider, for example, that service-sector industries—from health care to retail businesses to hotels—cannot outsource production abroad very easily, nor can they as easily replace workers with machines.9 While the changing structure of the economy explains why it may be harder to unionize in manufacturing industries, and while the “union premium” in these industries has declined over time, it does not tell us much about the failure of unions to break into or re-unionize industries like health care, education, and retail.

Ever since President Reagan broke the air traffic controllers’ strike in 1981 by summarily firing more than 11,000 workers, there has been the sense that one of the reasons for declining unionization is increased employer opposition buttressed by an anti-union state (though in the case of the air traffic controllers’ strike, the employer was the state). There is certainly a temporal correlation, and the rise of the anti-union industry in the past 50 years has undoubtedly played an important role in undermining organizing attempts.10 A recent study of over 1,000 union election campaigns found that employers regularly fire union supporters (in 34 percent of union election campaigns); threaten to close the business (57 percent); threaten to reduce wages and benefits (47 percent); use mandatory one-on-one meetings with employees to interrogate them about the union (63 percent); and threaten union supporters with disciplinary action (54 percent).11 In contrast to the situation in other Western industrialized countries, many of these strategies are actually legal under U.S. labor law.12 From this perspective, U.S. employers may not be any more anti-union in their attitudes than employers from other countries; they just have more legal flexibility.

But these strategies and worse have been around for decades, and employers’ advantages under U.S. law go back far earlier than the recent upsurge of employer anti-unionism that began in the late 1970s and early 1980s. The whole of American history overflows with moments in which the state has sided with employers over workers.13 During the Pullman Palace Car Company struggle, for example, the national railroad strike was crushed when a powerful employers’ association convinced President Grover Cleveland to call in federal troops.14 The history of Pullman and other key battles in early American labor history—Homestead, Cripple Creek, Haymarket, the Ludlow Massacre—help to put contemporary anti-unionism in perspective.

One doesn’t even have to travel back to the late nineteenth century for examples. In 1929, striking textile workers in Gastonia, North Carolina, were assaulted by mobs of masked men who escaped prosecution; in 1934, more than a thousand National Guard members with machine guns broke the Auto-Lite Strike in Toledo, Ohio; a decade later, in 1946, the U.S. government seized hundreds of refineries, railroads, and mines to break strikes by miners and oil workers; in 1970, the army took over post offices in New York City to break a postal strike. In short, we have experienced more than 150 years of state-supported opposition to labor organization. So it is hard to see how contemporary employer coercion uniquely accounts for the decline of unionization when increased unionization—albeit less than what would be expected absent such violence—was observed in periods when violent opposition was the most intense. And what about the temporal correlation? Well, just because things happen at the same time doesn’t mean that one causes the other. Think about minivans and autism. Prevalence increased for both at about the same time, but the idea that minivans cause autism is absurd.

But if employers’ exceptional power in the United States is not new, it may nevertheless help to explain the decline of labor—though not, or not only, for the reasons we often think. It is not just that powerful employers have prevented labor unions from forming; it is that powerful employers have impacted the development of labor’s organizational cultures and structures. U.S. employers’ exceptional degree of power, not just on the shop floor but in the halls of government, has repeatedly helped to strip the labor movement of its movement.

In the late nineteenth century, the Knights of Labor had as broad a social and political vision as any labor organizations in Europe. As a result, they inspired employers—with the aid of the state—to organize, often violently, against them.15 Such an assault would be repeated in response to the syndicalism of the late 1910s, and in response to the radical industrial organizing of the CIO in the 1930s. Labor’s expansive and inclusive vision was almost literally beaten out of it. And so by 1955, the height of labor union membership as a percentage of the workforce and the year when the CIO merged with the AFL, what was left was a much narrower organizational form: a bureaucratic system of collective bargaining at the employer level, confined to a limited set of manufacturing industries. Those labor leaders with communist sympathies, who had been so central to the militance of the 1930s, had been purged. Political mobilization, strikes, women’s auxiliaries, and other forms of collective action had given way to armies of lawyers and union staffers negotiating and administering thousands of firm-specific contracts, all with the result that “what may have begun as a spark of collective action for workers on the shop floor” is today “quickly extinguished by the soporific of bureaucratic procedure and legal interpretation.”16

What remained, then, was by and large a set of leaders and organizations who made the idea of a labor “movement” seem like a contradiction in terms. As labor’s horizons contracted, moreover, many union leaders prioritized representing their own members at the expense of those outside their rather narrow niche of manufacturing industries. The wages of unionized workers in industries like steel and auto rose dramatically, propelling them into the middle class, while millions of workers in agriculture, domestic service, retail, and elsewhere were left out. Unions also negotiated with individual employers for an array of selective incentives that, in other countries, became entitlements through processes of political struggle—health insurance, mortgage assistance, tuition benefits. This U.S. exceptionalism widened the gulf between unionized workers and everyone else, not to mention that it inflated the ranks of those union bureaucracies necessary for providing the unique array of services promised to its members.17

The irony is that as some trade unionists became wealthier and more established, their interests diverged from those of other workers and they became more conservative. By the late 1960s the typical union member, while still a Democrat, was increasingly likely to be socially conservative. A trace of that conservatism is revealed by labor’s decreasing centrality in social protest over the period from 1961 to 1968.18 More obvious, perhaps, is the fact that hard hats became the iconic opponents of the student, feminist, and anti-war movements.19

It is hardly surprising that these unions started to articulate messages that conformed to their members’ fears and desires. They were, in fact, representing their members. Labor unions behaved like those charismatic church sects that, having once served the needs of the dispossessed by directly addressing the problem of theodicy (why bad things happen to good people), morphed—as their congregations became more established—into established churches with increasingly abstract, esoteric rituals and messages drained of emotionality. If a hostile external environment first compelled unions to abandon broad solidarity for a more narrow protectionist stance, the growing chasm between unionized workers and everyone else only reinforced this conservatism. Unions came to protect existing jobs and existing members, winning the preservation of the status quo for their members at the expense of new hires or the unorganized, and doing little to address new generations of workers who saw—often correctly—that the unions were not speaking to or for them.20

As time went by, a demographic wave eroded the size of the unionized base as their membership slid into retirement. And so, when the bottom fell out and unions came under a new wave of attack, they had a much smaller, older, and more conservative base with which to resist.21 They could not easily speak to or for workers as a whole. Meanwhile, to the extent that union leaders had insulated themselves from any accountability to membership, they were able to continue to collect paychecks even as their organizations shriveled. Not surprisingly, challenges from the movement side—typically cast as critiques of corruption, when the more pressing problem was routinization—were often brutally suppressed by union officials. In the meantime, the economy was in a period of rapid transformation to which union leaders initially paid little attention.22

It is, admittedly, difficult to sort out the relative importance of external political and economic changes and internal organizational failures to the decline of the labor movement in the United States.23 These explanations are mutually constitutive. A history of employer and state opposition to those elements of the labor movement with the most expansive visions—from the Knights of the 1880s to the radicals of the 1930s—helped structure labor unions into the sclerotic bureaucracies they became, organizations that have been unable to respond adeptly to the economic changes and political assaults of the last 30 years.

Historically, the UFCW, which financed OUR Walmart at its inception in 2010, had been a pretty good case study in such union bureaucratization and inflexibility. It was founded in 1979 as a result of a merger between the Amalgamated Meat Cutters and Butcher Workers of North America and the Retail Clerks International Union, and since then has been the only large union in the retail industry. Since its founding, unionization rates in retail have declined from just under 9 percent to just over 3 percent, a drop of nearly two-thirds.24 And yet many in the union did not seem to think this was much of a problem. In a study of union revitalization, Kim Voss and Rachel Sherman seemed to cast the UFCW as a foil as they reported the responses from UFCW leaders who, “despite having lost almost all their power in the retail sector, still spoke of ‘not having to worry about market share’ because they had simply decided to think of themselves as representing only grocery workers.”25 Faced with crisis, the UFCW tended to look away.

But the UFCW could not ignore Walmart forever. Walmart was and continues to be, as Kim Moody puts it, “the 800-pound gorilla” in the labor movement.26 The point may have been driven home to the UFCW after it led a massive, unsuccessful strike in Southern California in 2003–2004, during which 59,000 unionized grocery workers struck or were locked out of more than 850 grocery stores at Vons, Safeway, Ralphs, and Albertsons. After nearly four months, at a cost of approximately $1 million per day, the union accepted a contract that reduced wages and health insurance coverage for new employees, a concession that Ruth Milkman suggests was seen by “friend and foe alike…as labor’s greatest defeat since the 1981 air traffic controllers’ strike.”27 What made these employers so aggressive after a quarter century of labor peace in Southern California? Nelson Lichtenstein writes, “The strike was convulsive because the most important player was not at the negotiating table. Supermarket executives, in Southern California and elsewhere, were taking a hard line against their employees because Wal-Mart was ready, willing, and anxious to eat their lunch.”28

REORGANIZING AROUND RESPECT

In the late 1980s and early 1990s—more than 30 years after unionization rates had peaked—a few unions began to make large investments in organizing the service sector, a move that surprised labor and organizational scholars, many of whom had by this point left the American labor movement for dead.29 In Southern California, while the UFCW was losing its power in the grocery industry, workers in the building services were gaining power with the SEIU’s Justice for Janitors campaign.30 Beyond Southern California there were scattered successes too: home-care workers across California, hotel workers in Las Vegas, and clerical workers at Harvard, to name a few.

The irony of the labor movement’s effort to organize service workers today, one that is recognized by organizations like OUR Walmart, is that it may need to return to the older, evangelical sect strategies of the 1930s, of 1919, of the late 1800s, to return to the idea that the essence of workplace organization is positive solidarity, a sense of belonging.31

Fostering this sense of positive solidarity, of collective identity, on Walmart’s shop floor is difficult, though. Community can sometimes arise on the retail floor, but it is irregular, always at risk of being interrupted by the capricious demands of supervisors and customers. And the sources of structural power that likely facilitated workers’ sense of collective efficacy in the factory, like the assembly line, are absent. While production at Walmart can be metaphorically described as an assembly line, it is more accurately a disaggregated set of tens of thousands of lines, each product moving at a different (average) pace from the truck to the shopping cart and out. Small groups of workers here do not have the same potential for disruption as they do in a plant; it would take a bigger group to bring operations to a stop.32 Against this background, note that because it is a global treatment, working to rule is one of the most powerful weapons available to service workers. But while effective against airlines and railroads, where there is a built-in distance between customers and, say, the pilots and engineers, working to rule is interactively enormously costly to workers at Walmart, who have to directly bear the brunt of dissatisfied customers—sometimes friends and neighbors—who would be unable to park, find products they want, and, if so fortunate as to find things, would be stuck in endless lines.

In America, the peculiarity of the contemporary labor movement is that it is dominated by organizations that, while still oriented around the collective good, seem ill-suited to respond to the underlying meanings and motivations of the collectivities that need it most. Unions might give individuals more money, but money is not usually what drives people to organize—community is. And where the conditions of production don’t naturally induce and sustain community, organizing around bread-and-butter issues is going to have a rough ride. Even in a context of crushing poverty, the movement needs to offer something other than a promised wage increase to be successful in the retail sector.

All this was understood by OUR Walmart. But putting understanding into practice would ultimately mean challenging many of the norms and rules and understandings of those who lead what is left of organized labor today.

ORGANIZING IS ABOUT MAKING A BUNCH OF LINKS

During Freedom Summer, in 1964, organizing meant embedding oneself within existing social networks to reshape those networks around collective goals. Rewiring social relationships—forming new ties where none existed before or helping to change the emphasis of a tie from one of friendship (or church membership or classmate) to one of solidarity—was an important strategy organizers used to help individuals and loosely connected networks coalesce into collective actors.

Fifty years later, in the summer of 2014, it is what the participants in the Summer for Respect program set out to achieve as well. The students didn’t invent this idea. It was a central premise of OUR Walmart and has been a central premise of organizing at least since Alexis de Tocqueville, who wrote in Democracy in America that “[i]n democratic countries, knowledge of how to combine is the mother of all other forms of knowledge; on its progress depends that of all the others.”33 It’s an idea that has since been memorialized in books like Saul Alinsky’s Rules for Radicals and revived in more contemporary work like Hahrie Han’s How Organizations Develop Activists and Jane McAlevey’s No Shortcuts.34 And it contrasts in important ways with the “frame theory” that predominates in social movement studies, in which language itself is given the power to shape participation through persuasive cognitive frames or metaphors or emotional appeals, as if language has power outside the social relationships that make language possible and influence how it is understood.

Consequently, it didn’t surprise us that, when Kevin was asked in an interview what he thought made a successful organizer, he responded, “An effective organizer is someone who doesn’t just go from one person to another person but kind of embeds themselves within a group and becomes almost part of that group, in a way.” This idea was echoed across many of the interviews with the students when they were asked what it is that organizers do. They described themselves as network entrepreneurs—at once figuring out the social networks of the stores (several were taught to diagram these networks on paper)—and changing them, building ties strategically so as to enhance the density and connectivity of the community of union support. Michelle, from the Los Angeles team, said that organizing was about “trying to make a lot of links,” linking workers to information, workers to one another, workers to the OUR Walmart organization.

AMBIGUITY OF INTENTION AND POSITION CAN FACILITATE CONTACTS, UP TO A POINT

After hearing about Gerald in the photo lab, Kevin returned to the Franklin store the following week, and set out straight away to find him. While Gerald helped another customer, Kevin killed time by looking at a GoPro camera display. When Gerald finished, Kevin introduced himself as a friend of Jenny and told Gerald that Jenny had told him Gerald was unhappy with the store. Gerald thought it was high time they had a union at Walmart. Jenny came over to listen. Kevin jotted in his phone, Speaks his mind like no other. Could be a great leader.

In retrospect, Kevin realized that Gerald—“labor-stealing motherfuckers”—was already a leader in the store, an “old head” whose lived experiences gave some perspective to what it was like working at Walmart. Jeff, another participant from the Ohio team, thought being able to identify existing leaders like Gerald, “specific people in a department that people look to for certain things,” was what made great organizers.

Gerald also knew just about everyone, could give Kevin guidance on whom to speak with and whom to avoid. He told Kevin that the clothing section of the store would probably be supportive of OUR Walmart—Virginia, in particular, was a good candidate. She also had past experience as a union representative. Finding former shop stewards at Walmart was a bit of good fortune. It also was much more likely to happen in southeastern Ohio than it was in Dallas or central Florida. While labor unions had more or less collapsed across the Rust Belt, people there were still carrying around memories of what labor organizations had done and could do. One important implication is that, following this logic, we are living in a relatively narrow period of time in which the memory of what unions do (or might do) is still alive in people who once were—but are no longer—members of them. Presumably the closing of this window will make the resurgence of labor even more difficult.

Gerald also told Kevin that he would help lay the groundwork among the women who worked in the clothing section of the Franklin store. So Kevin approached the clothing aisles with an air of confidence. The unusual thing about the clothing section was that the women there worked in groups, and so initially Kevin was stymied, since he worried that talking with more than one person at a time would increase the risk that one of them would report him to management. He set out to “pick off” certain employees, luring them into some far recess of their department where I could ask them questions. And that was how he met Judy—he asked her for help finding 7 for All Mankind jeans, a brand that he knew Walmart didn’t carry. Gerald had already spoken to her; she was prepared for Kevin’s approach. Kevin was not prepared for the fact that the organic group that formed around the women in the clothing section was the key to successful organizing. All that needed to happen was for the conversations to turn to collective topics.

Over the course of the summer, Kevin became a network entrepreneur. He would find these organic work groups and seed them with something different to talk about. He discovered and developed a social network of 18 workers at the Franklin store. Ten of these would go on to become members of OUR Walmart.

Many of the other participants in the Summer for Respect project also discussed using the ambiguity of their positions in the store—shopper? job seeker? advocate? interviewer?—to identify and connect with workers supportive of OUR Walmart and connect those supporters to one another. Harmony would often buy a pack of gum and talk to the cashiers. Greta, who often spoke to workers at bus stations, would use her smoking habit to her advantage: I told myself I was going to quit smoking on this summer vacation, but I realized that, when we started doing bus stops, I was like, it’s too good of an organizing tool. When she saw a Walmart worker, she would just “casually walk up” with her cigarette: They’re like, “Oh, can I bum a cigarette?” That’s perfect. It’s a perfect excuse. They already feel like they owe you something because you already gave them a cigarette.

Routine, role-ambiguous interaction within the store made an organizer seem less like an outsider. As Rebecca from Chicago put it, “making your face known” was important. Rebecca suggested, “It’s the mundane conversations that are the important ones, because that’s what establishes you as a presence.” Harmony, from the Ohio team, said she learned from Evelyn, the organizer who trained her, that “organizing is all about building relationships that strengthen over time.” Evelyn told Harmony, “I just hang out [in the store] and get to know people, and eventually, when people ask me why I’m always here and who I am, I tell them.” According to Harmony, Evelyn would “shoot the shit with people and hang out for months at a time before she tells people what she’s doing there.” Harmony’s first reaction was that this seemed “like a weird thing to do…When it’s an issue that you’re committed to, what’s the point of doing that when you can be more direct?” But over time she appreciated the strategy and wished that she could have been in the field for more than two months. A longer stay would have allowed her, like Evelyn, to “hang out with people and get people to trust you as a person before you talk about other things.” Importantly, the goal wasn’t to become friends. It was to gain trust.

The strategy several participants described, then, was to use local action—not to reveal their intentions, but not to say anything that was inconsistent with the ultimate organizing conversation they were hoping to have. As Kevin put it, “I don’t think our deception ever led to me pretending to be someone that I wasn’t.” And it didn’t. After all, they were just doing what Bob Moses suggested, bouncing a ball until they could meet some adults, and then hanging around in their networks sufficiently often to change the conversation.

One can imagine that if it were possible to scale up the process in which Kevin and other students were engaged and stretch it out temporally—the conversations organizers were having with workers and workers were having with one another, the recognition of common concerns and the equally startling recognition that, together, you might actually be able to do something about them—one could build a social movement, or at least make the conditions more fertile for one when it came along.

This was, and in some sense still is, a central premise of OUR Walmart. And it seemed to bear fruit. On Black Friday, November 23, 2012—the day after Thanksgiving—Walmart workers across the country walked off their jobs in the biggest one-day strike in the employer’s history. A New York Times article reported protests at over 1,000 stores and in 46 states, “ranging from a couple of community supporters’ asking to talk with store managers about raising wages to raucous demonstrations in the Los Angeles, New York and Washington areas that each attracted hundreds of people.”35 Was this the birth of a new labor movement among those who work at low-wage jobs? Many labor scholars were optimistic. Soon after the protests, Kate Bronfenbrenner, one of the foremost authorities on labor organizing and employer anti-union campaigns, said, “I feel hopeful…and I haven’t felt hopeful about Walmart workers ever before.”36

That early optimism was premature. First, it assumed that the UFCW and other unions would act on the opportunity that others saw in OUR Walmart and pour resources into building on the momentum of the strikes. Instead, as some in OUR Walmart reported, leaders at the UFCW seemed unaware of the strike and unappreciative of the potential of the moment. Labor has Stockholm syndrome, one put it. Second, unsurprisingly, OUR Walmart’s action provoked a strong reaction from Walmart. Even before the 2012 Black Friday protests, it would later be revealed, Walmart had hired Lockheed Martin, the large defense contractor, to help the company spy on OUR Walmart supporters within its workforce; contacted the FBI; tagged particular stores as dangerous hot spots; and increased its already large investment in monitoring its workforce for signs of dissension.37 And so, finally, by the summer of 2014, relatively few members of Walmart’s massive workforce had signed up formally as members of OUR Walmart. And there was little evidence that the marginal cost of recruitment was declining: if anything, new members were becoming harder, not easier, to recruit.

PMS

To see the opportunities and challenges faced by OUR Walmart, we need to return to the early days of OUR Walmart and to the lessons learned at one of the organization’s most active stores: the Pico Rivera Walmart Supercenter in Los Angeles. What happened at Pico—and in a few other stores—is that workers reclaimed the dignity that they felt Walmart had taken from them by adopting a new, collective identity. At Pico, this was about what it meant to be a woman. In Dallas, it was about being in an army of the just, like David battling Goliath. In Chicago, it was about race and the legacy of civil rights. The irony here is that the workers acted collectively as Walmart workers, as people whose new identities (as empowered women, as David, as freedom fighters) were centered on Walmart. From that standpoint they could and did make moral claims on their coworkers, on the public, and ultimately on Walmart executives hunkered down in Arkansas. So what happened at Pico?

Discussing the motivations that led to their organizing, Dora Avila, the key associate leader at the Pico store said, “Walmart has been advertising that they are a family-oriented company. And if this is how family is treated, then I would rather not have a family at all.”38 Dora dates her “radicalization” to being transferred to a Walmart in nearby Hemet [#1853] where she was confronted with blatant racism from the mostly white management there. She had never been treated so badly, she says, and she started to feel that

no associate needs to be disrespected, no associate needs to be mistreated. Like, everybody works at different speeds, everybody works differently. It literally opened my eyes…And until you experience it yourself, then you know what your associates are talking about.

Even after her “eyes had been opened,” though, it would take what for her was experienced as a serendipitous encounter39 before she became an active member of OUR Walmart. An organizer for the organization was dating Dora’s ex-brother-in-law, and Dora agreed to meet her at a local Starbucks: “She told me what it was about. I was, like, ‘Oh, sign me up.’ She was like, ‘For reals?’ So I was, like, ‘Yes. I got it, I understood it. Sign me up.’” Dora became the fourth member of OUR Walmart at the Pico store, on January 13, 2011. With Dora, the organizer had found the Pico Rivera equivalent to Gerald in the Franklin store—someone who was already a leader among her peers, who could connect other workers to the organization and to one another. Michelle Rogers was one of the first new recruits Dora brought into the fold.

Michelle had been a regular shopper at the Pico store and became friends with an inventory management specialist named Pat, who suggested she apply for a job there. Because she had a friend when she started, Michelle says her job “was kind of nice at first.” But she soon started getting chided by management—first because she wasn’t able to speak Spanish to the largely Latino clientele, and then because she was working the registers too slowly: “They really humiliated me and they always made you feel that you weren’t worthy. And that was the hard part working there. Always.” As she started talking to others at the store, she realized that managers were making everyone feel bad, targeting the Spanish-speaking employees for their bad English as much as they were targeting her for her bad Spanish.

Michelle describes the small, arbitrary indignities from management that began to get under her skin. During the holidays one year, the “lines [were] going crazy” when Michelle got kicked off her register for her lunch break. An assistant manager came by and told her that she couldn’t take lunch just yet because of the crowds. Michelle was worried that she’d be in violation of company policy, but the manager said that he would take care of it, and “put in his code on the register to have me stay.” A few days later she was disciplined for violating the policy, just as she had feared. When she told her managers that she had been told to stay, they said, “It doesn’t matter. You should have just walked away.” It left her feeling as though she were “damned if you do, damned if you don’t.”

Michelle heard about OUR Walmart from “Crazy Dora Avila,” she remembers. “She was always asking me, ‘Hey, mama, how’s things going?’ And I would tell her, ‘Not good,’ you know…. And she would say, ‘You know, when we get a chance, let’s talk.’” They met at a Del Taco, a nearby fast-food joint, where Dora introduced Michelle to some of the organizers from OUR Walmart. Then Michelle went home and “looked it all up to find out what was going on.” She concluded that “if I was going to have to be here for a few more years, no matter what,” then she would have to “either make change or just take the beatings.” She joined the organization on February 12, 2011.

Sandra Lopez provided the crucial third leg. In contrast to Dora and Michelle, Lopez had some prior political experience; she had previously volunteered with an immigrant rights organization called Vecinos Unidos (Neighbors United): “It was a way to help people and talk to people, just not be at home, because by then my son was in school full time and I just needed to keep busy, because I think you go crazy at home.” Her early political activity was as much about finding connection with others as it was about commitment to particular issues. Sandra stopped doing this volunteer work when she got her job as a cashier at the Walmart in 2004.

Early on at Pico she found herself on the short side of the favoritism game. Her experience resisting and still surviving gave her some confidence. It helped that she had less to lose than the other two: she says, “I’ve never been quiet. I’m scared, but I don’t think I’m as scared as everybody else, because I do have a choice, and that takes a lot of the fear away.” Sandra was supported by her “complication” at home and like a lot of other women had started working at Walmart because she was “bored at home.” Sandra explicitly references the fact that she has more flexibility, more “choice,” than other workers at Walmart, and that this helped take away her fear. Losing her job would be okay.

These three women—Dora, Michelle, and Sandra—became the backbone of the organizing effort at the Pico Rivera store. They decided to call themselves Pico Mighty Strikers, or PMS. Michelle explains, “One, because most of us were women and, you know, the whole thing, we all know generally in medical terms what PMS stands for. But at any rate, don’t mess with PMS.”

Early in their organizing, both Michelle and Dora faced retaliation from store managers. Dora was called in repeatedly for infractions like not completing forms correctly or being a minute late back from her break (managers have admitted to targeting OUR Walmart supporters in these ways). Her first response was fury—she remembers telling her manager, “I’m not going to sign [the disciplinary warnings]…. You could kiss my fat ass before you would ever get a statement from me!” In consultation with OUR Walmart, though, she channeled that outrage into filing an unfair labor practice charge against the store. Ultimately she was able to clear her record entirely—and, through this success, demonstrate to herself and her coworkers that one could successfully challenge the higher-ups. Michelle also had to fight back when her managers charged her with fabricated absences. She took advice from Dora and told them: “ ‘This is retaliation.’ And I told them that and they backed off.” But the experience of getting over her fear and standing up to her managers “reminded me how big they are not.”

Each step in the store’s escalating campaign was both frightening and exhilarating. Dora remembers being terrified during their first one-day strike: “I kept on thinking, ‘Oh my God, oh my God, oh my God, we just went on strike!’” But she had to hold it together for Michelle: “My friend was next to me. She was, like, ‘Are you okay?’ And, like, I snapped out of it.” She continued: “Like, I had to get into that mode of, like, you cannot show your fear, because you’re going to show it to everyone else, and they see you as their leader and you can’t. But I do remember that moment that I was, like, ‘Oh, shit. We’re on strike.’” Michelle, in turn, remembers how Dora helped her through her own fears: “I was getting sick. I was shaking and I kept telling myself, ‘What am I doing?’” But Dora helped her persist: “I eventually did it. I eventually walked with Dora.”

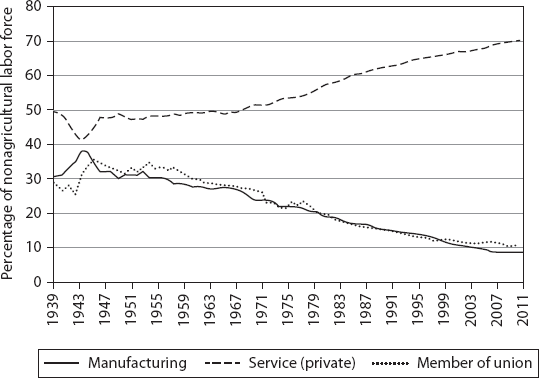

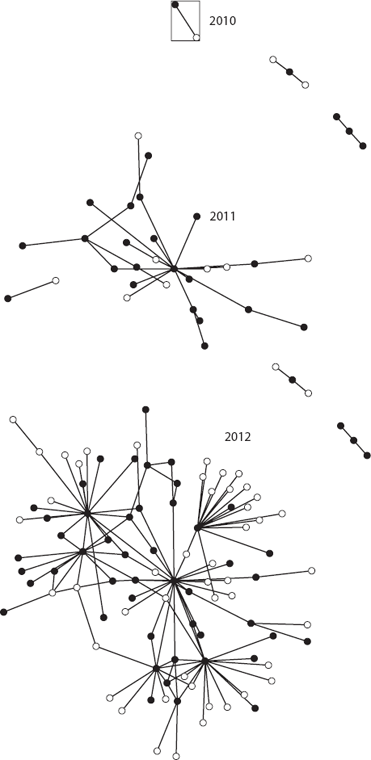

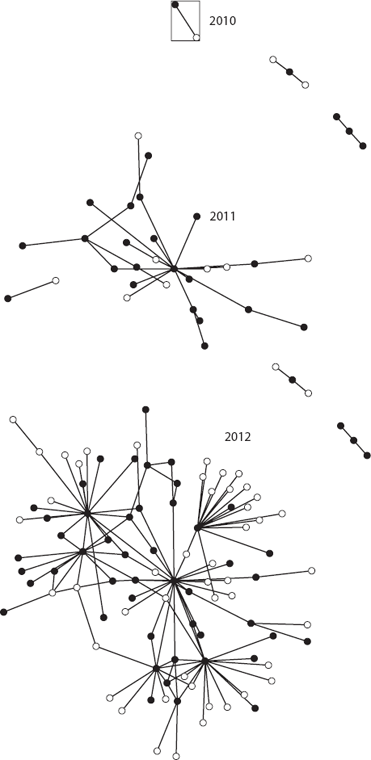

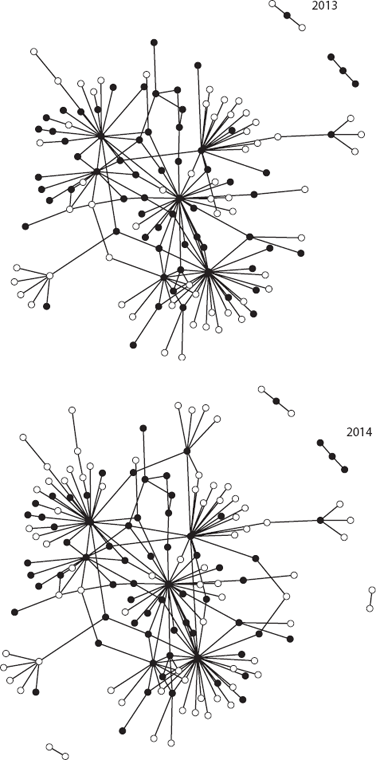

Because of the leadership of Dora, Michelle, and Sandra, the Pico Mighty Strikers grew quickly over the course of 2011. In under six months, over 50 workers had signed up for OUR Walmart within the Pico store. Eventually more than 120 would sign up there. A core group of committed leaders soon snowballed into a critical mass of activists. We can recreate this snowball in another way by turning to notes taken by OUR Walmart organizers in the early months of the Pico campaign, which document the unfolding of a store-level organizing network. Examining the network at yearly intervals lets us see the registration drive as it unfolded. Dora, Michelle, and Sandra were each at the center of a different subnetwork of workers. They were reaching out to different sets of workers (figure 4.2).

Yet even here, even with more than one-third of store employees as members of OUR Walmart, the organization never really posed much of a threat to the store’s operations. On its last Black Friday strike, in November of 2014, Pico posted the highest number of one-day strikers of any store in the country: 19. If Pico were an assembly line, then it is possible that less than one-tenth of the workforce might be able to shut down production. At Walmart, though, 19 workers can go on strike and—aside from the effect on customers who might have to cross a picket line—it is difficult to notice. Lines might be a little longer and bathrooms a little less clean and shelves a little more disorganized and products a little more scattered. But the essential aspect of the store—the fact that things are cheap and that people are buying the things that they want for less than they can get them anywhere else—well, that stays pretty much the same.

More significantly, a funny thing happened at Pico in April of 2015. The store developed some kind of plumbing problem. Walmart had to shut it down and lay off all the workers; the 120 who joined PMS and the 180 or so who didn’t. Six months later, Walmart had a grand reopening at Pico. Not one of the women affiliated with PMS was rehired.

TIES THAT BIND

Given the macrostructural, organizational, and historical obstacles to labor mobilization in the contemporary period reviewed earlier, it is unsurprising that OUR Walmart has not yet reached scale. In fact, perhaps the explanandum should not be the absence of large-scale mobilization but rather the presence of any such resistance. What had inspired Dora, Michelle, Sandra, and others at Pico to become so committed to such a seemingly Sisyphean struggle? And what can this teach us? For them, taking part in OUR Walmart felt like an obvious and necessary response to the injustices they experienced at the company. Dora’s immediate enthusiasm about the organization—“Sign me up!”—makes it seem like a no-brainer.

But while many feel a sense of injustice at the way they are treated by their managers at Walmart, feeling injustice is generally insufficient for standing up to it. In his classic book Exit, Voice, and Loyalty, Albert Hirschman describes, in a simple yet brilliant formulation, the two possible responses to organizational problems: exit and voice.40 (We will return to loyalty in a moment.) Exit, he argued, was the market response: You don’t like a product? Stop buying it. You don’t like an organization? Leave! If Dora, Michelle, and Sandra disliked working at Walmart so much, surely they could find other jobs that they would like better.

In the context of a labor market (or any market, for that matter), exit is the option that is most familiar, and many workers at Walmart take advantage of it. By January of 2015, you will remember, Anthony Thompson—from the commercial—had left Walmart for a job at Enterprise Rent-A-Car. Anthony was hardly the only one: even workers with long tenures like Eric Jackson, who had spent five years as a cart pusher at the store in Forest Park, was also ready to call it quits. At one time it had been a relaxing place to work, back when his friend Ray was there too. But Ray had quit for a job at the temp agency Kelly Services, and Eric was thinking of doing the same thing.41

Isn’t exit the sensible option? In terms of the raw economics, it makes almost no sense why any individual—one of 1.4 million Walmart employees in the United States—would invest any time trying to make such a massive corporation better. That time could be invested in doing any number of other things, like searching for a better job, taking night classes to qualify for a higher-paying job, or watching television while others try to make the company better. In the classic formulation of the “collective-action problem,” Mancur Olson showed that—under most circumstances—it is economically irrational for an individual to participate in collective action to secure public goods when he or she can “free ride” on the efforts of others.42 Of course, there are many exceptions that center around the provision of selective and solidary incentives, the structure of social relations, and so on. Still, all things considered, it takes a leap of faith to imagine that one’s contribution to the provision of a collective good will actually result in that good being provided.

High turnover rates in the low-wage service sector are more evidence that, at least here, employer intimidation may not be the primary obstacle to labor organization. As Stuart Tannock writes, “If workers are planning to quit their jobs in the near future in any event, then the risk of being fired for standing up for their rights may not seem so daunting.”43 Of course, under these conditions, the reasons for staying and standing up for one’s rights may feel absent too. The problem, that is, may not be the extent of employers’ opposition to unionization so much as the seemingly low costs of exit (and therefore low incentives for voice).44

But while exit may be sensible from the perspective of the individual worker, it is likely detrimental to those who work in low-wage jobs as a whole. The problem with exit is that it can only lead to organizational changes (“recuperation” in Hirschman’s terms) when there is some elasticity in the demand for the good (or the job) the organization offers. If there is a large group of equally capable workers ready to take the spot of any Walmart worker who quits, it is unlikely that the organization will feel any pressure to change as a result of such turnover. If anything, the company will be happy to have the disgruntled worker disappear. Furthermore, if other options are just as bad, individual workers might not actually be better off using exit either—they might repeatedly exit bad jobs with the (false) hope that the next one will be better, wasting energy they might otherwise have spent working to improve any one of those earlier situations.45 Despite the costs of turnover, the churn might help low-wage employers collectively avoid any claims on them. So the most sensible choices from the perspective of any individual worker—keeping one’s mouth shut or leaving the company—are also the choices likely to leave the distribution of jobs unchanged.

The formal economic irrationality of collective action begs the question why people like Dora, Michelle, Sandra, and thousands of others decided to use voice instead, to take on the company rather than take off from it. OUR Walmart was not proposing to unionize the company. The potential collective payoffs to participation in the organization were highly uncertain in time and scope, and so the impact of the marginal contribution of an individual worker was also difficult for anyone to understand. So what explains participation and what can this teach us more generally about the possibilities for labor mobilization among those who work in low-wage jobs?

The answer, in short, is that people participated because of the ties they had with other participants—ties that acted both as channels for information and influence and as tethers that kept them from leaving the company altogether. Moreover, these ties gave rise to a new sense of self, and as a consequence, the activists became other people, like the people engaged in PMS. In Hirschman’s formulation, one key determinant of a person’s or group’s likelihood for using voice over exit is loyalty, by which he means not an unquestioning allegiance to an organization but rather a “special attachment” that makes an actor “willing to trade off the certainty of exit against the uncertainties of an improvement in the deteriorated product.” Loyalty is not people doing nothing. Loyalty forces us to turn away from the easy exit and “thereby pushes men into the alternative, creativity-requiring course of action from which they would normally recoil.”46

For many workers at Walmart it was connection to and loyalty to one another that encouraged them to get involved in the organizing to begin with. This is, on its face, somewhat counterintuitive. It was the best parts of the job—people’s connections with one another, their codependencies at work, their sharing advice, their helping one another out—that provided both the motivation to fight against the company’s unjust practices and provided the avenues through which this participation occurred. What is counterintuitive is also part of the labor organizer’s common sense. Isolated, estranged workers rarely participate in labor organizing. Rather, it is those who are already in some kind of instrumental, task-oriented relationship with one another who are likely to take part. That is why the production line, which can induce such task-oriented collaborative relationships, often provides an immediate foundation for joint action in pursuit of a common good.

The importance of such networks is affirmed across the interviews we conducted with workers. When discussing how they got involved in OUR Walmart, most of our interviewees discussed it in the context of their existing relationships in the store. The most common account, related by 17 workers, was that one of their coworkers introduced them to an organizer who, in collaboration with the coworker, recruited them to participate; or, in a similar but distinct process, the worker was recruited by an organizer alongside a coworker, and the two joined together. Another common account, related by 10 people, was that one or more coworkers recruited them to participate in the organization without the involvement of any organizer at all. In all accounts of this type, workers discussed the respect they had for the coworkers who were a part of their recruitment. Julie Soto, who worked at a Walmart in Orlando, Florida [#908], got involved through her “best friend at work.” Julie continued, “We discussed about favoritism, sick time, cutting hours. At that time, I was really upset, so she asked me if I wanted to join the organization. So, I told her yes.”

For other workers, it was not that coworkers introduced them to the organization but rather that organizers began speaking with them along with their peers. Here, organizers engaged in the kind of process that Kevin described in the previous chapter, embedding themselves in the existing social structure of the store. Sue Rogers, who had found a sense of community among her coworkers over Friday-night dinners at the local Applebee’s, learned about OUR Walmart when organizers invited her and her coworkers to a meeting at the same restaurant: “I went to that first meeting there at Applebee’s, and they gave me all those booklets to read. And I started reading up on it, and I listened to the other people’s stories, and what results that they got from them, and it made me think, ‘Well, if enough people got together, and enough people voiced their opinions and voiced what they feel, maybe things will change eventually, in the long run.’”

At the Walmart Supercenter in Rosemead, California, Vickie Allard and her coworkers had begun to meet outside work over the summer of 2010. This was shortly after Vickie had been ordered to change her name tag from “Vickie” to “Victoria.” She invited a group of cashiers over to her house one Friday night. It evolved into a weekly event over the summer of 2010:

Some of the cashiers would come down to my house and would bring chips and drinks, and we would sit there and literally have what I would call a “bitch session” because we would sit there and bitch about everything [the management] would do to us.

Sitting outside, eating barbecue, they shared their common concerns. In the midst of these meetings, Vickie said, her sister reminded her that they had a relative who worked for the UFCW. One day the relative showed up at her door, with another UFCW organizer in tow, and told her about a new association of Walmart workers getting off the ground called OUR Walmart. “You wanna call your other friends?” she asked. Vickie called some of her cashier colleagues—those she trusted—to come to the house, and the organizers told them about OUR Walmart. Vickie remembers, “And I go, ‘What does OUR stand for?’ And they said, ‘Organization United for Respect.’ And I said, ‘Hell yes, give me a pen.’ And so did the other girls that were there with me, were right there with me signing it.” Here, again, relationships forged in the store served as the fabric into which the OUR Walmart organization was woven. In each case, a small group of coworkers gave new meaning to their existing relationships, becoming a core of the organizing effort.47

THE HOW, WHEN, AND WHERE OF WORKER SIGNING

A wide variety of network processes got workers involved with OUR Walmart. But becoming a member of the organization was always—or almost always—about being alongside people who also joined. In only seven cases out of the 43 accounts of joining did we hear a worker report being recruited alone by a paid staff organizer. And there were only two cases of workers signing up online without first being in touch with anyone. Signing was a decision made in relationship to others.

We know when each member in each store signed up for the organization, which allows us to see the order in which members signed up, broken out by store. One way of testing which relationships mattered for signing is to see how similar consecutive signers are along different relational dimensions. For example, if people tend to discuss the organization with others of the same gender, we would expect people of the same gender to sign consecutively more often than if signing occurred randomly by gender within a store. We ran 50 simulations in which we held constant the distribution of signers by category by store (e.g., we held constant the number of men and women who signed in a particular store) but randomized the order of these signers, and then compared the results of these simulations with the observed pattern of signing.

This sort of analysis is revealing of the types of ties that matter most for recruitment. Not counting family ties, which are powerful predictors of joint joining, workers are significantly more likely to work in the same department as the previous card signer than we would expect by chance. In contrast, the characteristics of workers that predict friendship play no role in motivating signing. For example, a worker was only 3 percent more likely to be of the same gender as the previous card signer than we would expect by chance, and tended to live in only a slightly more demographically similar neighborhood as the previous signer (4 percent more racially similar and 3 percent more similar by mean income). So while work department is a powerful source of social influence in card signing, demographic similarity—which tends to undergird friendship48—does not play an important role.

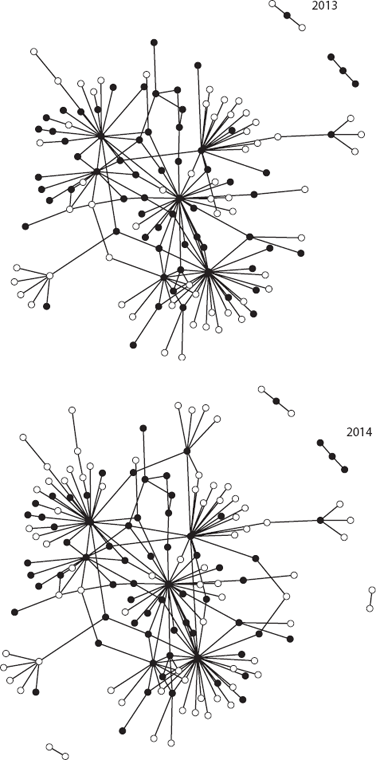

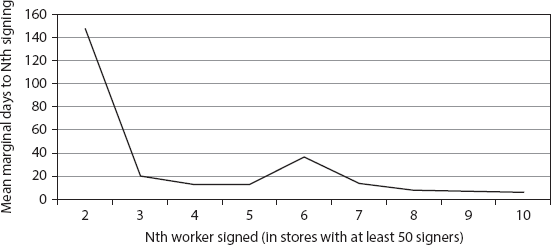

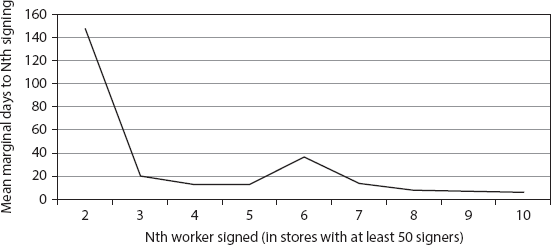

Processes of social influence can help to explain why individuals sign up for OUR Walmart; they can also help to explain how OUR Walmart gained momentum within particular stores. Key to seeing this momentum is the time between card signings within stores. Restricting our sample to those stores with a lot of members (defined in this case as those stores with over 50 signers), we investigated the average time between card signings (see figure 4.3). Here again, we can see evidence of a contagion effect in early card-signing uptake: the time between signings diminishes as group size increases. While the average time between the first and second card signing was just over 147 days, the average time between the ninth and tenth card signing was just under 6 days.49

These observations are consistent with the network dynamics we have described so far. In deciding whether to participate in collective action or join an organization like OUR Walmart, people take into consideration how much other people in their immediate work environment have already contributed or are likely to contribute.50

So we know that processes of social influence are important for the development of OUR Walmart chapters within particular stores, and we know that traditional predictors of friendship are less important for this recruitment process than ties based on shared workplace department. We can also explore whether there are certain positions or store attributes that make people more or less likely to sign up.

To examine these individual attributes and store characteristics, though, we have to compare those who sign up for OUR Walmart with workers with whom the organization was in contact but who did not sign up. Restricting our analysis to the well over 8,000 workers for whom we have department information, we see that some departments are much more likely to sign up for the organization than others. For example, the most likely positions to sign, in descending order, are those who work in the fitting room, cart pushers, and cashiers. Those least likely to sign are those who work in the back of the store, either in inventory or in shipping and receiving.

The most obvious difference across these positions involves the interactions workers are likely to have with one another and with organizers. Those working in the back of the store are isolated from the rest of the workplace and are difficult for organizers to reach.51 In contrast, cashiers and cart pushers are easy for organizers to find and engage in conversation. The same is true for fitting-room associates, who also serve as bridges across multiple departments and groups of workers, since the fitting-room desk serves as the “control tower” for the store, often responsible for answering outside phone calls to the store and directing them to the appropriate departments.

What is surprising about the three positions most likely to yield signers is that the selection process into those positions, should it matter, seems likely to be very different. Cart pushers, if they want to be cart pushers, seem likely to select that job because it has little customer interaction and is outside the view of managers. Fitting-room associates, on the other hand, have to spend a lot of time with customers, and they are constantly interacting with managers. Cashiers are essentially public facing. The fact that these positions demand such contradictory things suggests that their commonality—ease of contact for organizers—is what drives their overrepresentation among members.52

Our data also let us ask which kinds of stores were most likely to have people sign up for OUR Walmart, after controlling for the contacts that OUR Walmart made in a store. Here we see that stores in poorer and more heavily African American neighborhoods were more likely to elicit signatures. More interestingly, we see that bad Yelp ratings are strongly related to card signing. There are three ways to understand this relationship: first, whatever store-level factor is making workers unhappy is also making customers unhappy; and/or second, workers’ unhappiness, which expresses itself in signing up for OUR Walmart, is itself making customers unhappy; and/or third, unhappy customers make for unhappy workers.53 All three are probably self-reinforcing.

We also see that if a store experienced an Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) violation anytime in the years before OUR Walmart’s founding (i.e., pre-2010), it is more likely to experience card signatures. Again, it is somewhat difficult to interpret this relationship. On the one hand, an OSHA violation could signify a mismanaged store, which leads to more OUR Walmart members. On the other hand, an OSHA violation could indicate something different: that there is at least one worker at the store who is conscious enough of his or her rights and engaged enough to file an OSHA violation. In this case it is an indicator of leadership potential rather than store mismanagement.

These relationships are significant even after we control for the region of the country (three-digit zip code) in which the store is based. Once we drop this control, we can see a final store-level variable that helps to explain card signatures: the distance between the store and Walmart headquarters in Bentonville, Arkansas. Why does distance matter? It turns out that the distance between a store and Bentonville is a relatively good proxy for the age of the store, since Walmart’s strategy between 1962 and 1995 was to expand slowly outward from home.54 Newer stores tend also to be more receptive to organizing, probably because, all else being equal, older stores have a higher percentage of people who have worked for Walmart for a long time, a factor which is associated with being less interested in OUR Walmart (likely a result of people who are happier in their jobs selecting into staying). It is also true that Walmart’s corporate culture, developed in the Ozarks, may be less convincing to workers far away from headquarters.

Why have we spent so much time reviewing these data? For one thing, they show how a labor organization like OUR Walmart might use multiple sources of data to identify particular kinds of stores and particular sorts of employees within these stores to target. Whatever the causal relationship underlying the associations, it seems that labor organizations might use Yelp and administrative data like OSHA violations to find those stores in which organizing attempts are the most likely to get off of the ground.55 Furthermore, these data provide marching orders for how an organizer, or a customer ally, might most productively conduct a store visit: start in the parking lot with the cart pushers, go visit the fitting-room desk, and chat up a cashier as one buys a pack of gum on one’s way out.

With this said, all the analysis in the world can’t get past the one central fact. As a self-sustaining membership organization, OUR Walmart did not succeed between 2010 and 2015. Few people signed up. Still, that doesn’t mean that it failed. The Black Friday strikes and OUR Walmart’s other actions contributed to the sense that there was too much inequality in America, helping to fuel successful drives for increases in state minimum wages and, ultimately, increases in the minimum wages paid by the company. As importantly, for the people who did get involved, their involvement could be, though was not always, transformative.

THE PEOPLE WILL RISE UP, AND THIS GREAT EVIL WILL FALL

Much of the language that we have for talking about personal transformation is religious. It is not accidental that we describe radical transformations of self as being “born again.” One is born into existing social relations. Being born again implies that one enters into radically new relations with others. And our most intense personal experiences are usually relational at their core. Perhaps this is why religious imagery suffuses so many accounts of participation in OUR Walmart. Among the Pico Mighty Strikers, Michelle Rogers said,

Everybody wants to find their purpose on this earth, you know…And I find my purpose in that area, being able to speak for others who can’t speak for themselves, to be able to stand up to management who think they were God. You know, I love it…. It drives me. It’s my passion and sense, my purpose on this earth.

Sally Novak, from a Walmart in Glenwood, Illinois, used very similar language to describe why she participated in the organization. “I’d be filling the shelves and putting stock up on there and I’m talking to myself as I’m doing this, ‘Why am I fighting this? Why am I doing this? Why don’t I just quit?’” And yet, she says, “I just have that fight in me that doesn’t want to quit and I just can’t back down. That’s my purpose. It’s my purpose in life and I think I finally heard the calling. Maybe I haven’t been listening to it, but that is—seems to be my purpose.” When Sally gets the urge to quit, she feels a “nudge or that little voice behind me [that] says, ‘No, you don’t want to do that.’” She continues, “Honestly, I really don’t know if it’s my conscience talking to me or it’s really—is it God talking to me saying, ‘No, this is what you need to do’?” Rose Robinson, from a Chicago store, said she felt that God put her in the store “for all the scared babies up in there” who refused to outwardly support the organization.

In June 2013, Juan Meza joined a delegation of coworkers attending Walmart’s shareholders’ convention in Bentonville, Arkansas. He recalls a night when he was sitting in his hotel room with some of his coworkers. He says that he “never read[s] the Bible,” but that night, because “I got a feeling in me,” he picked up the hotel Bible and opened it to a random page where he read: The people will rise up, and this great evil will fall, when the people finally rise up together.

Man, my skin got all goosebumpy and everything, you know? I stopped and repeated that to everybody. I told them what I had just went through, and they’re like, “Read that thing out loud.” I read it out loud to everybody, and it’s just the moment, the trippy vibe of just, wow. This spiritual moment in the room. That kind of changed my life in a way.

There is an otherworldly character to these experiences. Walmart is revealed to be a false God. Don, an organizer from Dallas says:

Here is this giant laughing at this whole army and mocking the one, true God. Here is David, a little boy, who brings into remembrance that God is with him, who remembers that he killed the bear and he killed the lion…. He has enough courage to know that what Goliath is doing is mocking his God. So, he steps up to him and says basically, “I’m going to defeat you this day, but it’s going to be with the power of the Lord on my side”…. People think of Walmart as a giant they can’t beat…. That’s what Walmart wants you to think, but the truth is, yes, you can, and all you need is a few smooth stones to bring him down.

David made history. The religious imagery makes possible linkages from past struggles to imagined futures. Richard Walker, a worker in the produce department at the Walmart in Lancaster, Texas, connected others’ hesitations about being involved to examples from the civil rights movement: “What if Rosa Parks…would have hesitated? Malcolm X would have hesitated?” Dorian Jenkins, from a Walmart in Chicago, also responded to a counterfactual question about worker hesitancy with lessons from history:

Now I asked a young lady, “Do you want to sit there and let them talk to you like that?” The first thing that comes out of [her] mouth is, “I need my job.” I said, “I understand that, sweetheart, but you also need your pride and your dignity too. You just can’t let nobody run over you like this. What did Mama told us when we was coming up? ‘Do not let no one run over you there. You stand up for yourself.’ If they wasn’t out here marching Civil Rights, back in the ‘60s, the late ‘50s and ‘60s, man, we’d really be in a situation now.”

At the same time he looked to the past for inspiration, he also looked to the future, imagining that people might understand the work that he and others were doing in the same way that he looks back at the sacrifices made by his parents.

We got other little young kids that’s coming up. I may not be here long…but they’re going to be here. Walmart’s going to be here, and if they happen to can’t get no other job and they might have to work at Walmart…. Maybe, down the line, they’ll say—I’ll say in 2031, they’re going to see a poster of everybody from OUR Walmart sitting up there like this is the movement that changed everything in here.

Campaigning for God is deeper than just trying to increase wages. Campaigning for God is about changing everything. Mobilizing workers into a movement that connects them with history, that lets them imagine a new history they are actively writing, requires that people are really able to be embedded in new social relations, in a new community.

The idealized community represented by OUR Walmart wasn’t that different from the things that Walmart employees wanted out of their jobs at Walmart in the first place. They wanted, at once, a sense of community and a feeling of recognition. They wanted freedom from power relationships that felt exploitative—an abusive husband, an abusive boss. Religious experience propels the real communities that people search for into an imagined world. Insofar as churches can provide a relational underpinning for that imagined world, people can and do feel as though they belong to something greater than themselves, that they are therefore greater than themselves. But membership organizations have trouble sustaining this kind of relational energy. The desire for a community where community is absent is inexhaustible. It spills beyond the boundaries of any organization. It easily falls prey to other forms of religious content—that is, other contents in which the real problems of the world we live in are solved in imaginary futures. The trick is to build a community that works for people in such a manner that they can come to act collectively without requiring that the participants be born again—a this-worldly calling.