John Heartfield, “Adolf the Superman: Swallows Gold and Spouts Junk” (1932) (illustration credit 11.1)

In the 1960s, Richard C. Neuweiler, a refugee from Chicago’s Second City comedy club, had a routine in which he would wax nostalgic about the good old days when satirists reigned supreme, in the Berlin cabarets of the 1920s “that prevented the rise of Hitler.”

Of course the powerful montages of John Heartfield (1891–1968), along with the caricatures and cartoons of his German buddy and fellow Dadaist George Grosz, did not prevent Hitler and the National Socialists from coming to power. But that doesn’t mean that they didn’t count, nor that they failed to infuriate.

Satire has its own form of influence. In posters, newspapers, and magazines like Simplicissimus, Heartfield and his brother, Wieland Herzfelde, and Grosz, with whom he started the magazine Die Pleite, used their art along with other satirists of the day to expose Hitler and his goose-steppers for what they were.

“Although Heartfield was not a caricaturist in any conventional sense,” wrote William Feaver, art historian and art critic for London’s Observer, “he belongs firmly within the tradition of caricature.” Like Daumier’s “Gargantua,” in which King Louis Philippe consumes tribute from the wealthy, Heartfield’s “Adolf the Superman Swallows Gold and Spouts Junk” combines a photo of Hitler and an X ray that reveals a spine made of coins, a comment on the financial support the Nazi Party received from the German elite, while pretending to be a socialist, workers’ party.

John Heartfield, “Adolf the Superman: Swallows Gold and Spouts Junk” (1932) (illustration credit 11.1)

Remember that Heartfield and his colleagues helped pave the way for Walt Disney and his cartoon short Donald Duck in Nutzi Land (which included “Der Fuehrer’s Face”), in which Donald Duck is forced through so many “Heil Hitler”s that he eventually wakes up from his nightmare in the arms of the Statue of Liberty. The song became so popular that eventually they retitled the movie and named it after the song. Which calls to mind the question of primacy in different art forms. If a picture is worth ten thousand words, is a song worth ten thousand pictures? Cartoonists didn’t prevent Hitler from coming to power, but they contributed to his undoing.

Heartfield’s apartment was sacked, his art looted and destroyed, and eventually, like Grosz, he was forced to go into exile, in his case to Prague (and later to England), one step ahead of the police. In the 1930s, when Prague housed an exhibit of anti-Nazi drawings, Czechoslovakia refused to extradite Heartfield, who had begun doing photomontages for the Communist Party paper, AIZ. (He later joined the party.)

Heartfield, who changed his name from Helmut Herzfelde in protest against German anglophobia, invented the technique of the photomontage, “which is one of the most important innovations in the history of caricature,” writes Edward Lucie-Smith. He used his terrifying photomontages to attack National Socialism, German militarism, and, of course, Adolf Hitler himself. But in this case the outer face that reveals the inner soul is not a photo but a photomontage.

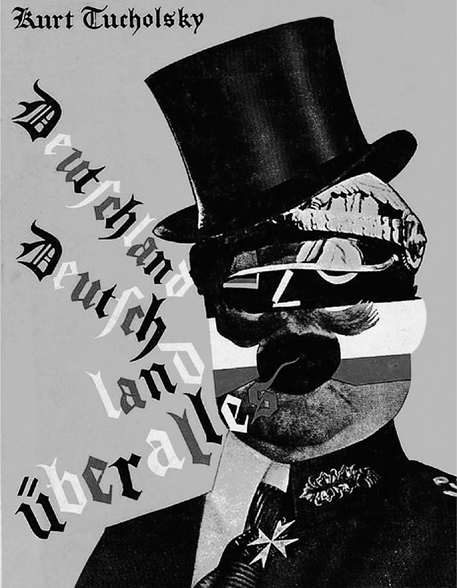

Although the science of physiognomy has long been widely discredited, perhaps the famous Heartfield photomontage for the cover of journalist Kurt Tucholsky’s book Deutschland, Deutschland Über Alles (Germany, Germany Over All) gave physiognomy a new meaning.

Tucholsky, editor of the weekly Die Weltbühne, a satirist, social critic, and songwriter, rejected especially the idea that faces (or photographs of them) were a way of reading the inner lives of whole races, as the Nazis came to do. But photomontage was something else again. Against a red and gold backdrop (Germany’s colors), the montage combined, as Andrea Jeannette Nelson noted:

a Prussian general’s uniform and helmet and a bourgeois businessman’s suit and top hat. The soldier/businessman is a visualization of the partnership between German capitalists and the military. The figure’s eyes (a German flag and an empty circle) are partially covered by the helmet, but his mouth (a gaping black hole) is wide open as he whole-heartedly, but blindly, sings the national anthem. The book’s title, a phrase from the anthem, is written in a traditional German Gothic typeface and comes spilling forth from his mouth.

John Heartfield, cover of Kurt Tucholsky’s Deutschland, Deutschland Über Alles (1929) (illustration credit 11.2)

As Claudia Schmölders, the author of Hitler’s Face: The Biography of an Image, reports, although the montage was meant to cut through and belie what she calls “the saccharine discourse on the human face,” nonetheless the authors took recourse in the physiognomic article of faith, “that the outer says everything there is to say about the inner.”

With the invention of Photoshop and other multimedia technologies, the photomontage techniques pioneered by Heartfield, who later became active in the Dada movement, would seem to anticipate the limitless technological potential for caricature in this age of digital apps.