David Low, “Rendezvous” (1941) (illustration credit 13.1)

David Low (1891–1963), born in New Zealand but working in London from 1919, was generally acclaimed as “the twentieth century’s greatest caricaturist.” He had two specialties that stood out among his numerous graphic gifts: dictators and fools, which, when you think about it (at least as he thought about it), were actually one specialty, in the sense that in his view all dictators were fools.

Colonel Blimp, his best-known fool, is another story. He stood for everything Low despised—pomposity, isolationism, impatience with common people and their concerns, and insufficient enthusiasm for democracy.

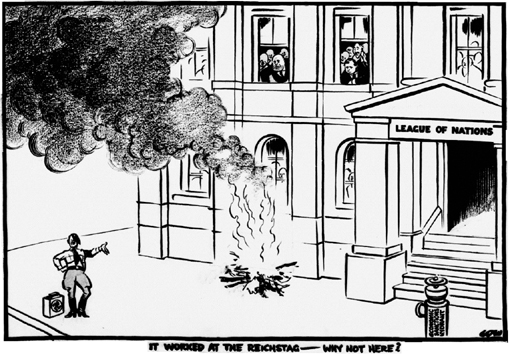

Although Colonel Blimp appeared some three hundred times, he represented only 2½ percent of Low’s total output. More typical were his cartoons and caricatures of dictators. See, for example, the cartoon that got his newspaper, the London Evening Standard, banned in Germany. When Germany withdrew from the League of Nations, Low drew a cartoon depicting Hitler standing near a bonfire outside its headquarters with the inscription: “It worked at the Reichstag—why not here?”1

Lord Beaverbrook, the owner of the Standard, especially made a trip to Germany to ask what he had to do to get the ban lifted. “Stop publishing Low,” he was informed. The British foreign secretary told Low he was “a factor going against peace” and asked him to modify his cartoons because they irritated the Nazi leaders personally. Low declined the honor, though, as we have seen, he withdrew his refusal later on. After the war, it turned out that Low’s name, along with a number of other British cartoonists, had found its way high on Hitler’s death list, the “Black Book.” Although I believe that Michael Foot, acting editor of the Standard, was right when he observed in 1938 that “Low more than any other single figure changed the atmosphere in the way people saw Hitler,” others differ.

David Low, “Hitler at the League of Nations” (1933)

Thus Timothy Benson, who earned his Ph.D. at the University of Kent and curated the first major show of Low’s work, wrote: “By depicting Hitler and Mussolini as figures of fun, Low may have inadvertently, to Beaverbrook’s possible relief, made them less threatening to those that saw them in his cartoons, compared to, say, other left-wing cartoonists.” The scholar W. A. Coupe in his book Observations on a Theory of Caricature (1969) wrote that “by representing serious political problems in humorous allegorical guise,” Low invited us “to laugh at our political predicaments, thereby in a way robbing them of their reality, or at least cocooning us from the horror in a web of gallows’ humour.”

That of course is not the way Hitler, Mussolini (who banned Low’s paper from Italy), or Franco (whose emissaries petitioned the British government to use its influence to get Low to lay off) saw it. I prefer Sir David Low’s own personal theory on why his cartoons were so effective in penetrating Hitler’s skin: because he showed Hitler less as a monster than as an idiot.

David Low, “Suezcide?” (1935) (illustration credit 13.4)

Interestingly, Timothy Benson believed that “if Low had the opportunity to choose a caricature of a Nazi leader, it would certainly not have been Hitler,” who was clearly an inferior physical subject when compared with other leading Nazis such as Göring (known for his garish clothing) and Goebbels (with his double chin). According to Low himself, the problem was partly a technical one: “One of my difficulties about Hitler is that I have to use fine lines to draw his eye[s], and when I send cartoons by radiogram to foreign countries the transmission process cannot pick up all those lines and my Hitler arrives at the other end with the lines lost on the way. Goebbels, on the other hand, is good to draw—dark, sharp lines.”

Of course Hitler was not the only dictator he mocked. He drew Mussolini as a Caesar wannabe. In “Suezcide?” he drew a granite-jawed Mussolini in Roman armor testing the temperature of the Suez Canal by dipping his big toe in the water. When the British foreign office put pressure on him to tone down his cartoon strip Hit and Muzz because his caricatures of Hitler and Mussolini were incurring the wrath of both of them, his solution was an aesthetic one. “I dropped Hitler and Mussolini,” he said, “and to take their places created Muzzler, a composite character fusing well-known features of both dictators without being identifiable to either.”

Low died in 1963. No wonder he inspired so many members of the next generation of cartoonists to take up their craft.

1It has always been assumed that the Nazis set fire to the Reichstag, Germany’s Parliament building.