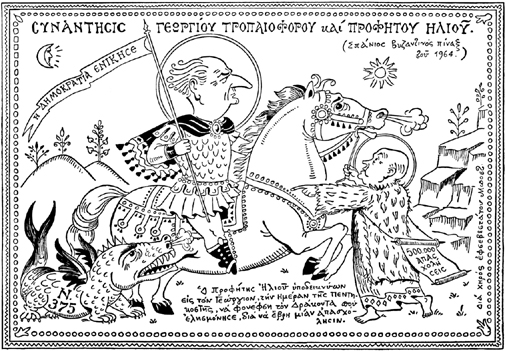

Bost, “St. George Triumphant and the Prophet Iliou” (1964) (illustration credit fm1.1)

The Content Theory—that in most cases, the cause for agitated discontent has to do with the cartoon’s political content—seems on the surface to be true almost by definition, and other than “Duh!” not that much more needs to be said. But as you will see from what follows, for better or worse, I have a lot more to say. So in the interest of transparency let me confess in advance that out of the countless examples one might have chosen, the basis of selection for the cartoon content discussed below is largely autobiographical.

As a founding member of the Committee to Protect Journalists, I have spent forty years on the board of an organization that works on behalf of journalists who got in trouble for something they wrote. But in all of those years, it never occurred to me until now to ask about cartoonists who got in trouble because of the content of their cartoons. Hence I include some startling examples of what I would have discovered. Then, because I witnessed it, I also include the firestorm caused by another Nation cartoon—this one by Ed Sorel, one of the world’s most talented graphic complainers about injustice and hypocrisy, also a former Monocle contributor and old friend. Beyond my personal experience I have included the UK cartoonist David Low’s caricatures of Adolf Hitler because his psychological insight into both his subject and his audience of one (Hitler himself) is so illuminating that I could not not share it. And finally, I have included the controversy surrounding the content of Barry Blitt’s New Yorker cover of the Obamas as terrorists because the response to it—which included candidate Obama’s decision to interrupt his campaign for president to air his displeasure—contains a lesson that no one who cares about the nature of caricature can afford to miss. Herewith, then, what I would have known about at the time had I invaded CPJ’s files (and, not incidentally, the files of the Cartoonists Rights Network International, mentioned earlier):

• In 1987, Naji al-Ali, the leading Palestinian cartoonist of his day, was murdered in London while on the way to his newspaper office. Ironically, it is still not known whether he was assassinated because he exposed the brutality of the Israeli occupation or because he criticized the hypocrisy of Yasser Arafat. Either way, it had to do with the political content of his cartoons. (See this page.)

• In 1992 the Sri Lankan cartoonist Jiffry Yoonoos drew a series of cartoons critical of then-president Ranasinghe Primadas. Yoonoos was beaten and stabbed, his family terrorized, forcing his wife and child to go into hiding.

• In 1995, Yemeni cartoonist Saleh Ali was arrested after publishing his anti-censorship cartoon showing a Yemeni man with his hands tied behind his back, his mouth locked, as the arresting officer explains, “Democracy is what I say.”

• In 2002, Paul-Louis Nyemb Ntoogueé (aka Popoli), a longtime critic of Paul Biya’s Cameroonian regime, and founder of Le Popoli Messager, an investigative journal in comic-book form, was beaten by security officers, and arrested for his cartoon referring to the first lady’s alleged past as a prostitute.

• In 2005, cartoonist Oleg Minich was charged with defaming the president of Belarus, and that country’s internal security service gave him the choice of five years in prison or permanent exile.

• In 2006, the Iranian government, responding to riots among its minority Azeri population over a children’s cartoon Azeris found offensive, jailed the artist, Mana Neyestani, in Tehran’s notorious Evin prison. In the riots, which killed nineteen people, his home was stoned and his newspaper’s office was burned down. His crime: a cartoon that showed a cockroach responding to a Farsi-speaking boy with the Azeri word “Namana?”—meaning roughly, “I don’t get it.” Although Neyestani stressed this was also a commonly used Persian slang word, many Azeris thought the cartoon implied that they were ignorant cockroaches.

• In 2011 the Syrian cartoonist Ali Ferzat was attacked by masked members of Syria’s security forces, who broke both of his hands, dumped him by the side of the road, and said, “This is just a warning.”

The examples of cartoonists punished for the content of their cartoons could go on and on, but unlike the cartoons that gave rise to them, they are not funny—with the possible exception of what happened to the Greek cartoonist Crysanthos Mentis Bostantzoglou, aka Bost:

On April 5, 1964, the Greek newspaper I Avgi published Bost’s cartoon “St. George Triumphant and the Prophet Iliou.” Set in Byzantine style, it showed the newly elected prime minister, George Papandreou, as St. George, beset by Ilias Iliou, the parliamentary leader, as the prophet Elijah (“Iliou” being the Greek equivalent of that name), carrying a screed calling for five hundred thousand more jobs. Because Iliou loved the cartoon so much, Bost made him a copy in oil paint, which Iliou kept in his office. When a military junta seized power in 1967, it also seized Iliou, its leading foe, and the painting. In 1973, Iliou, by then a free man, received a summons that directed him to contact the deputy commissioner “in order to collect a painting.” Iliou retrieved the painting and affixed the summons to the back, along with his own note, which reads, “This picture was a political prisoner from 23 April 1967 to 11 April 1973.”

Closer to home, as Jerelle Kraus, the former art director of The New York Times Op-Ed page, reports in her book All the Art That’s Fit to Print (and Some That Wasn’t), “nearly any notion is palatable when rendered in prose. When the same notion is pictured, however, the record shows that Op-Ed editors see it as a far greater threat.” Her account of how Times editors rejected artist Brad Holland’s illustration following the 1971 Attica prison uprising reinforces the point: the editors deemed it “pro-prisoner,” perhaps influenced by the fact that the Op-Ed article it was meant to accompany itself took the prisoners’ side.1 Holland donated the drawing to the Attica Defense Fund, and Kraus reports that a year later the Times published the drawing as a “cultural artifact” with a caption that read, “A poster from the Attica Defense Fund.” Which, of course, is not to say that written content doesn’t matter. It always has and always will; just ask Salman Rushdie about the fatwa placed on his head after he published The Satanic Verses.

These days, especially when cartoons deal with such matters as sex, sexism, sexual orientation, race, racism, religion, and religious fundamentalism, they can evoke primal responses. When that happens, while the viewer may denounce the cartoon, the irony here, as was the case with David Levine, is that it is precisely because the caricature has artistic depth and merit that the outrage is so keenly felt. The more powerful the caricature, the more outraged the protest.

As Bob Mankoff, cartoonist and longtime cartoon editor of The New Yorker, notes, we like the joke or not depending on what we believe. For each person, the sweet spot (and the offended one) is different. Let us then by way of demonstration inspect three very different cartoons, all by world-class cartoonists, each of whose content profoundly offended a different constituency. First, a panel by Ed Sorel, who took time out from his regular attacks on organized religion to comment on a publisher’s hypocrisy, but in the process outraged a wide swath of feminists. Second, a cartoon by the UK’s David Low, one of his series on Hitler, all of which caused the Führer to have a fit of rage bordering on hysteria. And third, Barry Blitt’s aforementioned New Yorker cover on the Obamas, which led then-candidate Obama to interrupt his campaign for president to air his displeasure.

This brilliant American cartoonist, caricaturist, muralist, moralist, freethinker, author, and graphic designer has won so many honors and awards as to threaten his reputation as America’s number-one scourge of the establishment. His cartoons have been called “vehemently anti-clerical,” an all-time understatement, but in this notable case his target was the late Frances Lear and her new American magazine, Lear’s, which was aimed at women over forty years old.

Here was a case where the written message was clearly what upset people, but equally clear, in my view, is that it was the pictures that not only drew people to the words and reinforced them, but together give the message its emotional meaning. The pictures, one might say, bring the words into focus.

In this case, the panels show Lear in a variety of poses as the narrative proceeds apace (see next page). After having her assert that men had said a woman with no experience couldn’t start her own magazine for older women, Sorel shows Lear getting carried away and increasingly cross-eyed as she concludes that, “All a woman needs is vision, determination and a very rich husband who’ll give her $112 million for a divorce.”

Edward Sorel, “Enter Queen Lear, Triumphant” (1988) (illustration credit fm1.3)

Once again The Nation staff descended (albeit this time without a petition). And once again the grievance had to do with a feminist political issue—although in this case the episode was infected by the sort of petty charges that small offices seem to specialize in. Sorel believed that a leader of the protest was angling to go to work for Lear. Sorel’s critics believed that he was retaliating against Lear for a turned-down cartoon. In a letter to the editor (the whole text of which appears on this page), the noted artist Jules Feiffer wrote that “after thirty years of work on a level that is simply extraordinary, [Sorel] shouldn’t have to pass an ideological means test to get in The Nation’s pages.”

My own guess as to what was going on here is that Sorel thought he was simultaneously making a joke about her divorce settlement from TV producer Norman Lear and a statement about what he saw as Frances Lear’s hypocrisy in claiming that other (less important, less affluent) women could do as she had done; the objections took issue not so much with Sorel’s point as with his premise that divorced women should not be presumed to have “earned” their settlement (whatever its size). But I would add that what really caused the blood to boil over was his deftly drawn images of a wacky but recognizable Lear getting increasingly disheveled, not to mention cross-eyed, as she was carried away by her own message. Images command attention in a way that words don’t (even offensive ones).

Moreover, one suspects that had Sorel written a prose poem criticizing what he regarded as Lear’s hypocrisy, he would not have referred to her as wacky or goggle-eyed (which she wasn’t), or if he had, I hope/assume that his copy editor would have crossed it out—all of which suggests either that editorial standards for prose are stricter than (or at least different from) standards for images, or that there is no visual equivalent when it comes to eliminating the gratuitous insult. Almost by definition cartoonists are allowed visual leeway denied to word people.

In the run-up to World War II, David Low, generally thought to be the most brilliant cartoonist of his day, produced regular caricatures of Hitler and Mussolini for London’s Evening Standard. Unlike the vicious, cruel, and revolting depictions in the Nazi weekly Der Stürmer, on the surface Low’s caricatures had an innocence, on more than one occasion showing Hitler as a spoiled brat.

When I was a boy growing up in New York City during World War II, few things gave me more pleasure than listening to and chiming in on Spike Jones’s rendition of “Der Fuehrer’s Face” (“Ven Der Fuehrer says ve iss der master race/Ve heil, heil right in Der Fuehrer’s face …”), so I was especially interested to read of Der Führer’s reactions to Low’s deceptively innocent but politically cutting cartoons of him which appeared with regularity in the 1930s. After Lord Halifax, the British foreign secretary, returned from a November 1937 meeting in Berlin with Joseph Goebbels, Hitler’s propaganda minister, to discuss tensions between their governments, Halifax reported to Low’s publisher at the Standard: “You cannot imagine the frenzy these cartoons cause. As soon as a copy of the Evening Standard arrives, it is pounced on for Low’s cartoon, and if it is of Hitler, as it usually is, telephones buzz, tempers rise, fevers mount, and the whole governmental system of Germany is in an uproar. It has hardly subsided before the next one arrives. We in England can’t understand the violence of the reaction.”

David Low, “Little Adolf Tries On the Spiked Moustache” (1930) (illustration credit fm1.4)

But hoping to make peace with Germany (actually, appeasing Germany), the government approached the London Evening Standard’s business manager, Michael Wardell, to see if they might get Low to ease up on the Nazis and their leader. According to Michael Foot, the acting editor of the Standard who went on to become a leader of the Labour Party, Wardell was “a fascist sympathizer,” but when Lord Halifax met with him, even he said that Low was not controllable: “Low has a contract which gives him complete immunity. Of course, I could refuse to publish a cartoon, if it were blasphemous or obscene or libelous, or in such bad taste as to bring discredit on the newspaper. But Low’s cartoons don’t fall into any of those categories. They just make you mad, if you don’t agree with them.”

In the end, however, Low relented when the foreign secretary took him to lunch and explained his problem. “Do I understand you to say that you would find it easier to promote peace if my cartoons did not irritate the Nazi leaders personally?” Low asked. “Yes,” Halifax replied. “I said, ‘Well, I’m sorry,’ ” Low explained later. “Of course he was the foreign secretary, what else could I say? So I said, ‘Very well, I don’t want to be responsible for a World War.’ But I said, ‘It’s my duty as a journalist to report matters faithfully and in my own medium I have to speak the truth. And I think this man is awful. But I’ll slow down a bit.’ So I did.”

Sir David Low himself had a theory to explain the fits thrown by Hitler and his general staff over Low’s cartoons showing him as ineffectual: “No dictator is inconvenienced or even displeased by cartoons showing his terrible person stalking through blood and mud. That is the kind of idea about himself that the power-seeking world-beater would want to propagate. It not only feeds his vanity, but unfortunately it shows profitable returns in an awed world. What he does not want to get around is the idea that he is an ass, which is really damaging.”

Low’s theory, in addition to being this gifted satirist’s original insight into dictators as a class, turned out to have had particular relevance to Hitler himself. In 1932, Hitler showed Ernst “Putzi” Hanfstaengl, his foreign-press secretary, a particularly irksome anti-Hitler cartoon, and dreamed aloud of retaliation. Hanfstaengl suggested that they publish a book of such offensive cartoons pointing out the cartoonists’ errors. The result was Hanfstaengl’s fancily bound volume Hitler in der Karikatur der Welt: Tat gegen Tinte (Hitler in the World’s Cartoons: Facts Versus Ink), which was published by an obscure house in order for the book to appear independent. The cartoons he chose to rebut, writes Cris Whetton of the Political Cartoon Society, reveal something of Hitler’s insecurities:

Georges, “The Grim Reaper,” The Nation (1933) (illustration credit fm1.5)

Fourteen (20%) of the cartoons selected for Hanfstaengl’s rebuttal clearly respond to the question, popular at the time: Who really controls Hitler? … Allegations of militarism are the next most common category, with eleven (15%) cartoons, mostly published after January, 1933, and mostly from the foreign press. One is led to wonder why. Hitler’s militarism, as presented to the German public at that time, was limited to repudiation of the Versailles Treaty, re-armament, and the presentation of the new Germany as an armed bulwark against “Bolshevism.” These were all popular with the average German. Was Hitler afraid that the foreign press could see behind the mask?

Rather than have a series of conniptions, with Putzi’s help Hitler strove to “answer” each cartoon selected. Since the attempt to answer visual charges with verbal responses was doomed from the outset and since the refutations were spurious, the book had a short life.

Nevertheless, I am particularly pleased to report that one of the cartoons Putzi chose to reprint in the book came from, of all places, a small New York–based magazine called The Nation. It depicted Hitler as a Grim Reaper with an army of skeletons marching at his feet. The blades on the Reaper’s scythe, in the shape of a swastika, dripped with blood.

In the following pages Putzi added his gloss, to make sure the readers laughed for the right reasons. After summarizing the cartoon’s content—“The Nation suggests Hitler was a war-monger”—Putzi added “the facts: On July 15, 1933, Hitler authorized the German ambassador to Rome to sign the Four Powers Pact, through which Italy, England, France, and Germany ensured peace in Europe for the next ten years.”

The New Yorker is perhaps America’s most prestigious magazine. Its readers are presumed to be literate, sophisticated, informed, and vaguely liberal, but above the fray. Yet in Barack Obama’s first presidential campaign, when the magazine featured cartoonist Barry Blitt’s version of candidate Obama and his wife, Michelle, dressed in terrorist garb, doing a fist bump, not only did thousands of agitated readers complain, but the Democratic candidate for President of the United States of America, who one might have thought had more pressing matters on his mind, took time out from his campaign to denounce the cover as offensive.

In fact, the avalanche of threats, denunciations, and subscription cancellations by previously loyal New Yorker readers was the result of a misunderstanding. The cancellers saw the cover as an accusation that Obama was in league with the terrorists, whereas, as editor David Remnick explained, “It’s not a satire about Obama—it’s a satire about the distortions and prejudices about Obama.” The objecting readers, however, were not to be dissuaded, persuaded as they were that the cartoon, called “The Politics of Fear,” does not so much lampoon the smear as perpetuate it, and the national director of the Arab-American Anti-Defamation League chimed in that “what needs to be challenged is the underlying assumption that being Muslim is the same as being Un-American, that being Muslim is the same as being violent, that being Muslim is the same as being Osama Bin Laden.”

Barry Blitt, “The Politics of Fear,” The New Yorker (2008) (illustration credit fm1.6)

But what seems inarguable is that, although over the years readers of The New Yorker have taken serious and noisy exception to articles that have appeared in the magazine (think, for example, of Hannah Arendt’s “Eichmann in Jerusalem”), this cover cartoon seems to have stimulated unprecedented emotional blowback. And the fact that readers misinterpreted it (if one takes the artist’s word as to his intent and accepts Remnick’s explication of its meaning) only underlines the fact that readers may interpret and respond to visual “argument,” if there is such a thing, in a different way than to words.

As cartoonist Steve Brodner and scholar Jytte Klausen observe elsewhere in these pages, too often images and especially cartoons are subject to misinterpretation, especially when they are viewed out of cultural context.

This particular cartoon, I believe, ran into trouble because it mixed satire and caricature. Barry Blitt was not merely caricaturing the Obamas. He was simultaneously satirizing the right-wing view that they were Muslim terrorists. Maybe the moral is that this sort of meta-caricature (a caricature of a caricature) reveals the limits of the caricature form. Satire requires rational distance. For many viewers the cartoon didn’t convey the message Blitt and Remnick intended because Blitt’s Obama caricature had its own life force.2 Hypothesis: once particular caricatures are released, they function as uncontrollable totems.

In each of these cases—Sorel’s nonfeminist premise, Low’s revelation of the pitiful sissy behind an über dictator’s façade, and Barry Blitt’s presentation of the Obamas (misread as an accusation of support for terrorists)—the cartoon’s content was seen as objectionable, but it was the visual language that caused the combustion.

Thus far I have discussed the cartoon’s content as if it were a message contained in the visual envelope of the cartoon itself. But it is important to remember, as the critic Cleanth Brooks once wrote about attempts to paraphrase poetry, “that the paraphrase is not the real core meaning which constitutes the essence of the poem.” Form and content are inseparable. And as with poetry, to paraphrase a cartoon’s content is at best an inadequate guide to its real meaning or impact. To get at that we must consider the cartoon as visual language. Hence, the Image Theory.

1 In 1971, inmates at the Attica Correctional Facility in New York State revolted, taking prison guards as hostages. The prison was stormed resulting in a firefight that killed thirty-nine.

2 As New Yorker followers know, the Obama fist bump was only the latest in a series of cover imbroglios all caused by cartoon content.