Seymour gapes to take in pheromone information from a new kitten being fostered in his home.

Sara Bennett

Rachel Malamed, DVM, DACVB, and Karen Lynn Chieko Sueda, DVM, DACVB

Misty slowly walked into the living room. Amy was happy to see her out and about. Though she had been part of the family for fifteen years, Misty had recently been spending most of her time alone in the guest bedroom. But who could blame her? Between Amy’s work schedule and the kids’ activities, the house had become chaotic.

Amy watched as Misty jumped up on the couch next to her. Taking advantage of the momentary peace in the house, Amy picked Misty up to snuggle. Misty gave a rusty meow before settling on Amy’s lap. As Amy stroked Misty’s back, Misty’s ears turned to the side, and the tip of her tail began twitching. Amy recognized that Misty was upset but couldn’t imagine why. “What’s the matter, kiddo?” Misty began licking her hand in response. “Aww,” Amy thought, “she’s grooming me,” and she gave Misty an affectionate pat on the back. All of a sudden, Misty hissed, swatted Amy’s hand, jumped off her lap, and ran out of the room. Amy looked at her hand and saw she was bleeding from the scratch.

Amy was distraught. What had happened? She had just been petting Misty. What if the cat had done this to one of her children? Amy wondered whether Misty could be trusted around the kids.

This exchange was very different from Misty’s point of view. She hadn’t been feeling well recently. Her knees and back hurt, and it was hard to stay out of the children’s way as they ran around the house. It was easier to stay put on the guest bed. But now it was quiet, and there was a patch of sun on the living room couch. Jumping up would be uncomfortable, but the allure of the sunbeam made it worth the effort.

When Amy picked her up, Misty winced as she felt a twinge in her back. Ow! But it was over in a second, and Amy’s lap was warm. Although she enjoyed Amy’s company, Misty couldn’t understand why Amy kept touching her aching back. Misty pinned her ears back and twitched her tail as a warning sign. She tried to move away, but her knees were sore.

Amy stopped stroking her back and rubbed her cheek instead. Misty licked Amy’s hand to let her know she was confused: I like the warmth of your lap, but I don’t like you touching my back. All of a sudden Amy hit her on the back. That hurt! Misty swatted Amy’s hand away and ran out of the room.

Misty was distraught. What had happened? Amy had been hurting her, and she had defended herself. Misty wondered if Amy was safe and doubted whether she could trust Amy to pet her again.

As this story illustrates, cats and people find it difficult to communicate, because the two species don’t speak the same language. However, once we learn how (and why) cats send us messages, we can become better at receiving and correctly interpreting them. This will enable us to respond appropriately and prevent any miscommunication between our feline friends and us.

The Egyptian feline goddess Bastet, familiars of witches, Garfield, Grumpy Cat: throughout history, humans have viewed cats as mysterious, self-centered creatures to be either worshipped or vilified. This reputation may be due in part to cats’ mercurial nature—friendly one second and aloof or defensive the next. What cat owner hasn’t wondered what their cat was thinking behind those beautiful eyes?

Humans are accustomed to dealing with demonstrative beings, whether it’s our dog ecstatically licking our face or our friend extolling the brilliance of the tweet she wrote. If communication had a volume control, humans would shout, dogs would talk, and cats would whisper. Cats use much subtler forms of communication than we are used to receiving. But once we recognize what to look and listen for, we can easily decipher the cryptic language of cats.

Affiliative behaviors: These “come closer” behaviors indicate friendly intent, reduce tension, and communicate a desire to approach. They include:

Allogrooming: Mutual grooming between two friendly cats.

Allorubbing: A cat rubbing her body against another cat or a person.

Bunting: A cat rubbing her cheek on objects. Cats have scent glands in their cheeks, and this action is used to mark objects and people with pheromones when a cat finds them to be safe and comforting.

Aggression: The range of “go away” behaviors a cat uses to frighten or threaten harm to another individual. The goal is to increase the distance between the cat and the perceived threat. Although people regard the word “aggression” as being offensive, it is most often used for self-defense, and at times is a normal and necessary behavior. Motivations for aggressive responses include fear, self-defense, protecting a resource or territory, and defending offspring. Aggressive behaviors range from subtle body language used to intimidate or scare (such as staring) to severe attacks resulting in injury or death.

Piloerection: The involuntary reflex of raised hair along the body and tail, commonly seen when a cat is in an emotionally aroused or fearful state.

Displacement behaviors: Normal behaviors displayed outside the context in which they typically occur. Animals usually exhibit displacement behaviors when they are anxious, confused, or frustrated. Common displacement behaviors in cats include grooming and scratching, and may be thought of as the kitty equivalent of people bouncing their leg or biting their nails when they are nervous.

Caterwaul: A loud, harsh vocalization usually emitted by cats as a mating call.

Trill: A vocalization used by a mother cat communicating with her kittens. It is also a positive vocalization heard during friendly interactions with people and other cats. A trill sounds like a ringtone meow or a question.

Pheromones: Species-specific chemical signals that animals use to communicate with others of the same species. Pheromones differ from scents or odors because only individuals of the same species can detect them. Cats use several types of pheromones to send messages to other cats, including the feline facial pheromone, the maternal appeasing pheromone (along the mammary chain of nursing females), the feline interdigital pheromone (in the paws), and pheromones in urine.

Social spacing: The distribution of cats in space and time in the area where they live. Social spacing is used to maintain distance between individuals, even within the home. Visual communication and marking may be helpful to establish space and “zoning” for individual cats. For free-ranging cats, social spacing is largely influenced by the availability and distribution of resources such as food. The density of cats is higher in areas where there is more plentiful and uniformly distributed food (for example, where many small rodents are equally scattered across an area).

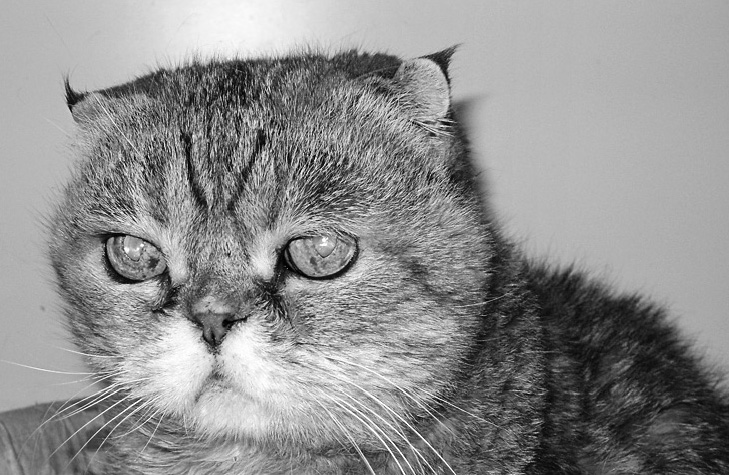

Brachycephalic: Having a short nose and flat face. Cat breeds with this feature include the Exotic Shorthair and Persian.

Cats’ behavior seems inscrutable because they rely on different forms of communication than humans. Humans are a verbal species—we communicate primarily through spoken and written language. Though cats communicate using vocalizations, they also depend heavily on visual, olfactory (smell), and tactile (touch) signals—forms of communication humans are not very attuned to (see “Feline Communication Methods”).

It’s easy for us to recognize a purr or a hiss, but much harder to determine a cat’s emotions based on facial expression, pupil size, or ear position. Don’t feel bad; even animal experts find it difficult to assess how a cat is feeling using only visual signs. In a study by Dr. E. Holden of the University of Glasgow, veterinarians and veterinary staff found that it is difficult to determine whether a cat is in pain based on facial expression alone.

|

Forms |

Examples |

Distance Requirements |

Olfactory (scent) |

Waste odors Pheromones |

Urine and feces marking Feline facial pheromone Feline interdigital pheromone in paw pads |

Communication over longer distance and duration Sender is able to deposit the signal and leave the area |

Visual (sight) |

Body language Behavior Visual marks (prompts closer investigation) |

Ears pinned back (fearful) Hiding Scratch marks left on a tree or chair Upright flagpole tail Outstretched paw (soliciting play) |

Sender and recipient must be able to see each other (except for visual marks left behind) |

Auditory (sound) |

Vocalizations |

Meow Purr Hiss Yowl |

Intermediate range Sender may remain hidden |

Tactile (touch) |

Touching |

Friendly touch (allorub, allogroom) Aggressive touch (swat, bite) |

Immediate proximity is necessary |

We can train ourselves to be better observers of feline body language and behavior, but there are some forms of feline communication we are physically incapable of detecting. These include pheromones—species-specific chemicals cats leave behind when, for example, they rub their cheek against us or scratch the couch. We can never fully comprehend this valuable scent information, but other cats can.

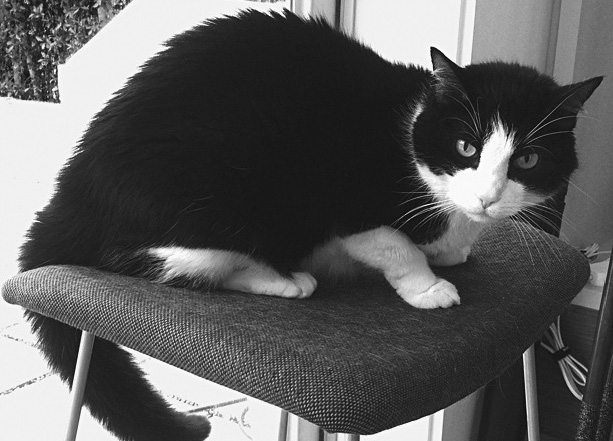

Cats detect and process information contained in pheromones using a specialized sensory structure called the vomeronasal organ. The vomeronasal organ has a microscopic opening just behind cats’ upper incisors, which acts like a specialized tiny nose. When a cat inhales an interesting odor or pheromone, she opens her mouth and brings a small amount of the scent into the opening of the vomeronasal organ. This open-mouth expression, called a gape or flehmen, enables cats to interpret species-specific information that is inaccessible to humans.

Seymour gapes to take in pheromone information from a new kitten being fostered in his home.

Sara Bennett

Why do cats need so many ways to communicate? Each form of communication is best suited to certain types of messages. For example, when a cat sprays urine, pheromones in her urine let other cats know that she was there and provide some personal information, such as her sex and relationship status. Think of it as “Kitty Facebook.” The ability to post information and walk away enables cats to multitask: while their message is displayed in one location, they are free to engage in activities elsewhere, such as finding food, shelter, or a mate. Similarly, the ability to leave “pee mail” in one location before moving to another enables cats to post messages over a large area but still avoid predators or competitors. These olfactory messages help maintain social spacing between cats who would rather avoid a confrontation.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, cats must be in relatively close proximity for visual signals (such as body language) to be effective. When they are farther apart, cats use larger gestures, such as signaling friendly intent by raising their tail like a flagpole. They reserve smaller gestures, such as ear movements and tail twitches, for closer interactions.

This stray cat approached with his tail raised like a flagpole and followed Dr. Karen Sueda through the small German village where he lived.

Karen Lynn Chieko Sueda

Cats can quickly adjust their body language to respond to changing interactions. If the mood goes from friendly to tense, for example, cats will let you know by altering their ear position, eyes, tail carriage, or body posture in a flash. Maintaining an open dialogue with your cat involves constantly observing how her body language changes in reaction to your behavior.

Even though these two cats are playing, the calico on top of the cat tree is probably defending her perch from her brown tabby sister below. The tabby’s ears are slightly pinned back and to the side, indicating concern and apprehension, while the calico’s are alert and forward, indicating excitement and arousal.

Karen Lynn Chieko Sueda

Cats reserve tactile communication for close friends—or aggressive encounters. Tactile communication includes mutual grooming (allogrooming) and rubbing against each other to exchange pheromones (allorubbing). Cats appreciate having plenty of personal space, so choosing to be in close contact with another cat or a human signifies a close bond.

Though not littermates, these two girls were adopted together from the shelter and have been inseparable ever since. They often lie in physical contact and allogroom.

Amy C. Sturlini

Like people, cats tend to form friendships with related or familiar individuals, and frequent or prolonged physical contact occurs only between friends and family. You might be willing to hold a loved one’s hand, but stop at a brief handshake with a stranger. Similarly, a cat may rub against an unfamiliar person’s leg to mark him with her scent, but only choose to sleep on the lap of a person she knows well.

In general, body postures can be grouped into two categories: those that encourage others to come closer and those that say “go away.” We briefly discussed one “come closer” posture—a cat approaching with an upright flagpole tail—earlier in this chapter. Cats use this signal to invite interaction. Similarly, a relaxed body accompanied by a cheek rub or an outstretched paw (with sheathed claws) indicates a cat’s desire to make a connection.

“Go away” body postures serve one of two purposes: to make a cat seem smaller in order to help her hide, or to make her appear larger and more formidable in order to ward off an attacker. Fearful cats create a smaller silhouette by pinning back their ears, tucking their legs underneath their body, and wrapping their tail under or around themselves. These cats hope to avoid detection by crouching and remaining hidden—out of sight, out of mind.

However, if an attacker (sometimes a perceived threat, not a real one) finds and confronts the cat, her fight-or-flight response will take over. If she cannot flee, she may display another “go away” body posture—that of a Halloween cat. To intimidate her attacker, a terrified cat will contract special muscles in her skin, causing her fur to stand on end, or piloerect. Piloerection, combined with the cat standing straight up and arching her back, makes her appear larger and more intimidating than she actually is. Add a soundtrack of hissing and spitting, and the cat has an impressive defensive strategy to drive off a would-be attacker.

The Halloween cat: this kitty’s arched back, piloerect fur, flattened ears, open-mouth hissing, and dilated pupils are a display of profound fear.

Sharon Crowell-Davis

Body Part |

Position |

What It Can Mean |

Eyes |

Closed |

Sleeping, relaxed May be in pain or uncomfortable if accompanied by tense facial features |

|

Casual gaze |

Calm |

|

Blinking slowly |

Calm, relaxed |

|

Averted gaze |

Nervous |

|

Pupils dilated (big, wide) |

Fearful, aroused |

|

Fixed stare |

Tense, possibly aggressive |

Ears |

Relaxed, neutral position |

Calm |

|

Forward |

Alert, attentive, aggressive |

|

Semi-rotated outward |

Fearful |

|

Flattened against the head, either to the side (airplane wings) or backward (earless appearance) |

Very fearful, fearfully aggressive |

Mouth |

Tight |

Tense, fearful |

|

Open |

Vocalizing, often aggressive (for example, hissing when fearfully aggressive) |

|

Gape (also called flehmen) |

Assessing pheromones |

|

Pant |

Difficulty breathing |

Tail |

Neutral, relaxed, tail tip may move slightly |

Calm |

|

Upright (called flagpole) |

Friendly |

|

Curled tightly around body or hidden |

Fear, uncertainty |

|

Twitching or lashing |

Aroused, agitated |

Body carriage |

Hunched/crouched, body tense or curled, appears small |

Fear, uncertainty |

|

Stretched out, loose |

Relaxed |

|

Halloween cat (arched back with bottle-brush tail, ears may be back) |

Very fearfully aggressive |

|

Rolled on back, stretching, loose body |

Relaxed, greeting behavior |

|

Rolled on back, tense body |

Fearfully aggressive |

|

Tense |

Alert, aroused |

Like body postures, feline vocalizations may be divided roughly into “come closer” and “go away” meanings. “Go away” messages include hissing, spitting, growling, and yowling. Cats hiss or spit when they are scared and protecting themselves (defensive aggression). Cats may growl or yowl when they are defending themselves or when they are offensively aggressive (a more confident, proactive type of aggression), such as when they are fighting with other cats over resources like territory or access to food or mates.

Cats communicate with us using the same language they use to speak to other cats. Meows are the exception. Adult cats don’t often meow to other cats, but they do commonly meow at humans. Why do cats reserve this vocalization for people?

Meowing is actually a kitten vocalization that cats adapt to communicate with human caregivers. Kittens begin crying and meowing at birth, even before their eyes and ears are open. Kittens’ meows stimulate adult cats to pay attention to them.

The ability to meow remains in adult cats and is applied to the next caregiver—cat owners. Adult cats learn to meow at humans for the same reason they meowed at their mom—to get attention. Humans are a vocal species, and we tend to pay more attention to vocalizations than to visual cues. When our cat meows, we pay attention to her, which reinforces the cat’s meowing—a positive feedback loop.

Cat owners can identify specific meanings for different meows. One meow may mean “Feed me,” while another means “Pet me.” When Dr. Sarah Ellis at the University of Lincoln in England played recordings of meows to cat owners, the owners could identify why their own cat was meowing (hungry vs. waiting for food vs. confined behind a barrier vs. wanting attention), but they had more trouble determining why unfamiliar cats were vocalizing. It seems that rather than there being a universal “meow code,” each individual cat and owner develop their own “meow language” that’s unique to them.

Cats say “come closer” using several vocalizations, including the trill, purr, and meow. Cats trill or chirp when they are greeting friends—another cat or a person. Cats purr around other cats as well as people. Purring appears to signal a cat’s request for comforting, since purring occurs both when a cat is content and when she is uncomfortable or in pain (see “Purring: Nature and Nurture” later in this chapter). Meowing, however, appears to be a unique vocalization reserved primarily for people, as cats meow at other cats infrequently (see “The Cat’s Meow”).

Intent |

Vocalization |

Situation |

Affiliative/friendly |

Trill/chirp |

Greeting |

|

Purr |

Soliciting care in either pleasurable social situations or when ill |

|

Meow |

Seeking attention from people |

Aggressive |

Growl |

Offensive or defensive aggression |

|

Hiss |

Defensive aggression |

|

Spit |

Defensive aggression |

|

Yowl |

Offensive or defensive aggression |

|

Shriek |

Pain or fear |

Sexual |

Caterwaul |

Mating call |

Hunting |

Chatter |

Predatory/feeding behavior |

Cats combine visual and vocal signals, often sending redundant messages to make sure their intention is clear. This is similar to a person saying yes while nodding their head. For example, a friendly cat may approach with a raised flagpole tail and trill a greeting. A fearful, defensive cat may turn her ears back, lean away, and lash her tail while growling.

Occasionally, cats send mixed signals. For example, a cat may appear to be relaxed, because she is lying on her side with her eyes half-closed, but her ears are slightly turned back and her tail is twitching. Which part of her body do we believe? When cats display varied or even conflicting body language, they are expressing ambivalence or uncertainty about a situation. The cat in this example may be happy and content lying in the sun, but not want you or another cat to come too close.

People send mixed signals in many situations. For example, you bump into an acquaintance while out running errands on your lunch break, and you want to show her a dozen pictures of your new grandchild. She may smile politely, a friendly gesture, but also lean away and raise her hand in front of her to decline, unconsciously saying “stay away.” As with people, when cats send mixed signals, it’s best to play it safe and heed the “stay away” part of the message. You can always reevaluate the situation later to see if the message has changed.

Careful cat observers read the entire cat. If you’re uncertain what your cat is saying, consider all her signals to determine whether they are all saying the same thing.

Hidden from view, she waited, crouched and taut, with only the tip of her tail moving. Ears perked, she watched her prey, eyes wide to take in the light. At the last moment, she drew her paws under her and pounced. The paper ball was hers at last!

Nature molded cats to be formidable hunters. Possessing good night vision, independently swiveling ears, and the ability to hear ultrasonic rodent squeaks, cats can locate prey that’s invisible to humans. Despite being predators themselves, though, cats are also preyed upon by larger animals. Cougars, bobcats, coyotes, dogs, and even eagles and owls attack and kill cats. Being solitary rather than pack hunters, cats are usually alone when they encounter enemies. Therefore, their best strategy when faced with a threat is to run and hide.

This has caused cats to adopt a “run first, ask questions later” policy. Cats typically cope with stressful situations through avoidance rather than confrontation. Whether threatened by another cat, a dog, or a trip to the veterinarian, cats tend to flee to either hidden (under the bed) or elevated (top of the bookcase) safe areas where they can evade the threat.

This tuxedo cat has just seen an unfamiliar dog and jumped up on a stool to escape. His crouched posture and lowered tail are signs of fear. The hair along his spine is also standing on end (piloerection), and he has a bottle-brush tail, which makes him appear larger—a defensive strategy.

Karen Lynn Chieko Sueda

For lesser threats, cats practice more subtle avoidance strategies and choose just to stay away. This avoidance is also a kind of communication. In the story at the start of this chapter, Misty chose to stay out of the living room when the children were home.

Similarly, if two cats aren’t getting along, they may actively avoid encounters as a way to prevent direct confrontations or fights. For example, one cat may turn and walk away if she notices the other cat lying in the hallway. Or she may use the cat tree only in the morning, when the other cat is sleeping in another room. The two cats arrange things so they are never in the same place at the same time.

Because cats apply similar maneuvers if they are afraid of the family dog, visitors, or even some family members, noticing their evasion tactics helps us detect and address early signs of tension and fear before they get worse.

Yet another result of cats being prey animals is that they are very good at hiding illness. While this is an excellent self-protection strategy in the wild (predators can’t target them as easy prey), it makes it exceptionally difficult for owners to recognize when to take their cats to the veterinarian. In addition to obvious physical signs (such as vomiting or loss of appetite), cat owners should interpret any change in behavior as a possible sign of illness. (See avoiding Catastrophe: How to Recognize Signs of Pain and Illness in Your Cat” later in this chapter to learn more about identifying signs of illness in cats.)

Do cats like belly rubs? Kate grew up with dogs, but Nala was her first cat. As Kate gazed down at Nala lying in the sunbeam, Nala yawned, stretched out her paw, and rolled onto her back. “Aww . . . she wants her tummy rubbed,” Kate thought. As soon as Kate touched Nala’s belly, the cat grabbed Kate’s arm, bit her hand, and kicked her with her back claws. Kate was shocked. “Why would she ask for a belly rub and then attack me?” she wondered.

Cats do not want a belly rub when they expose their belly. Some cats may roll on their back and expose their tummy when they greet you or when they are content and relaxed. This is the ultimate compliment. Your cat is demonstrating her trust in you by exposing a vulnerable body part. However, it is usually not an invitation to pet her. Though there are exceptions, most cats do not enjoy having their belly rubbed, and doing so is intrusive—like someone tickling you while you’re stretching.

This brown tabby has voluntarily rolled onto her back but does not want a belly rub. She would likely grab and bite your hand if you reached for her.

Karen Lynn Chieko Sueda

Cats also may lie on their back when they’re frightened. To drive the point home, they may exhibit multiple signs of fear, such as pinning their ears back while growling and hissing at their assailant. Lying on their back puts all four sets of claws between them and their attacker. Cats in this position are ready to defend themselves and will likely interpret your approaching hand as a threat.

Another sometimes confusing signal is that cats wag their tail when they are upset, not happy. It’s best not to approach a cat with a rapidly moving tail. In general, the more a cat’s tail thrashes or twitches, the more aroused the cat is. Cats show mild to moderate annoyance by flicking the tip of their tail—similar to people drumming their fingers in an irritated manner. As the frustration builds, more of the cat’s tail may become involved. You may notice this angry, lashing tail right before a cat fight or when your cat sees an unfamiliar cat through the window.

Licking can be a sign of confusion or annoyance. We all know that cats groom themselves by licking their fur. In fact, cats have special barbs on their tongue that help them do this (which is why cats’ tongues feel rough when they lick us). However, cats also lick themselves when they are anxious or confused. Think of the last time you saw your cat attempt a jump but miss. To cover up her “embarrassment,” she probably stopped and groomed herself for a few seconds. This is similar to a nervous person playing with their hair. These normal behaviors, displayed in unusual situations, are called displacement behaviors and indicate that a cat is worried or unsure.

Cats may lick themselves excessively, resulting in fur loss or even bald patches. While this overgrooming may be due to anxiety or stress in some cats (see chapter 10 for a discussion of compulsive behaviors), a study by Dr. Gary Landsberg, DACVB, and his colleagues found that it is more often the result of a physical illness that is causing pain and discomfort, such as an allergy or a gastrointestinal disorder.

Cats may also lick us for attention. Between two friendly cats, allogrooming helps them bond. Similarly, when your cat licks you while being petted, this may be a form of allogrooming, although not all licking is a sign of friendliness. Sometimes cats lick us not for attention, but as a displacement behavior if they are feeling anxious. In the story at the start of this chapter, Misty licked Amy because she was confused; she liked Amy’s petting, but it was also painful. Amy did not realize that Misty was nervous about the interaction and continued to pet her, which later caused Misty to swat Amy’s hand.

How do you determine whether licking is friendly allogrooming or a nervous displacement behavior? Observe the rest of your cat’s body language. Are her ears and tail telling you she’s relaxed or worried? Rather than focusing on one body part or behavior, read your cat’s entire body and overall behavior to determine how she is feeling.

Whether you are interacting with a person or a cat, communication is straightforward if you follow some simple guidelines: observe the individual’s behavior, interpret her body language, make sure all her body parts are congruent (they all say the same thing), interact, and then reevaluate. Better communication with our feline companions comes down to six simple steps.

Learn their language.

Listen with all your senses.

Use cues that work for cats.

Avoid miscommunication traps.

Teach a common language.

Have realistic expectations.

Peter rescued Pearl just a few weeks ago. He noticed that Pearl spent most of her time hiding with her tail curled under, body crouched, and pupils dilated. Unlike previous kittens he had interacted with, Pearl could not be enticed closer by fuzzy mice or wand toys. When Peter approached Pearl, she hissed. She assumed a Halloween cat posture with an arched back and bottle-brush tail.

Peter thought that perhaps if Pearl knew he was in charge, she might be able to relax. Peter consulted the Internet, where he was instructed to “pretend to be the mother cat, scruffing the kitten firmly by the loose skin above her haunches while suspending her body in the air.” When he attempted to implement this advice, Pearl yowled and sank her teeth into his skin.

In this case, Peter’s misguided plan to act and “speak” like a cat backfired. Pearl, who was already fearful, became defensively aggressive and went into fight-or-flight mode. A mother cat may pick up her young kittens by the scruff, but this is mainly to carry them from one place to another, not as a form of discipline. When a human “scruffs” a kitten or adult cat, it can cause pain and stress.

We cannot replicate cat behaviors, and cats do not see us as members of their species. Our goal is not to mirror cat behavior in an attempt to “speak cat.” Rather, we can use knowledge of our cats’ language to better understand their emotional states and anticipate how they may react. Our ability to understand and predict our cats’ behavior will help prevent miscommunication that may inadvertently diminish our bond or create more misunderstanding.

Realizing his mistake, Peter took a different approach. Instead of imposing himself on Pearl, he created a private suite just for her—a quiet sanctuary room with a litter box, food, water, some toys, and a perch next to a large bay window. For a few minutes several times a day, Peter sat at the threshold of the room with his body turned away from Pearl. He was silent or spoke quietly, almost in a whisper. He did not move and dared not reach for Pearl.

Slowly, day by day, Pearl came out from hiding and began to approach Peter. When Pearl bunted her cheek against Peter’s knee, he knew that she was starting to relax. Once Pearl’s anxiety diminished, she became increasingly social every day. After only a few more weeks, she began chasing the fuzzy mice Peter tossed down the hall. It was a slow process, but the result was well worth the wait.

Peter respectfully observed and interpreted Pearl’s body language. He used this information to continually evaluate and adjust his interactions with her. He recognized that the direct and forthright approach humans use to greet each other could appear threatening to a cat.

By modifying Pearl’s environment to help her feel safe and secure, Peter was able to diminish her stress and improve her comfort. Hideaways and vertical spaces in the form of boxes, shelves, and perches allow for easier escape in response to a perceived threat. Cats seem to enjoy an aerial perspective, which lets them easily spot both predators and prey. Had Peter restricted Pearl’s ability to escape by approaching her or picking her up, Pearl’s fearful behavior may have escalated to vocal and postural threats, and ultimately a physical attack.

This cat surveys her environment from above. Vertical spaces offer comfort and provide an opportunity for cats to escape from perceived threats.

Kathleen Spencer

A cat’s heavy reliance on nonverbal communication requires us to listen with all our senses so we do not miss important information. Observation is a skill that is developed and refined over time. Humans are not naturally adept at observing subtle body postures, facial expressions, and tactile cues, especially in another species. Recognizing and then deciphering what your cat is saying takes practice.

Strengthen your observation and communication skills by constantly observing how your cat’s body language changes in response to your behavior and the environment. Your back-and-forth behavioral dialogue will make you a better tabby translator.

Cats respond to a variety of human cues, including gestures and vocalizations. Dr. Adam Miklosi and his team found that the cats in their study correctly interpreted their owner’s pointing gesture, using it at a distance to find hidden food. In fact, cats performed just as well as dogs on this task.

In another study, by Dr. Atsuko Saito and Dr. Kazutaka Shinozuka, cats distinguished their owner’s voice from those of several strangers, proving that cats can use vocal cues alone to differentiate humans. These cats oriented toward their owner’s voice by turning their head or swiveling their ears, but made no attempt to respond by vocalizing or coming when called.

We consciously use gestures and verbal cues to communicate with our cats, but do cats pick up on our unexpressed emotions as well? In short, yes. Our emotional state may influence our cats’ perception and behavior. Research conducted by Dr. Isabella Merola and her colleagues indicated that cats pay attention to their owners’ facial and vocal emotional reactions to an unfamiliar object and may change their own behavior to match their owners’ emotional response.

For example, in Dr. Merola’s research, when an owner acted fearful of an electric fan that their cat had not seen before, the cat looked back and forth not only between the fan and her owner, but also between the fan and the exit route. If your cat looks to you for guidance in a novel situation, behaving calmly may provide a sense of security to your cat.

To cats, humans may look and act like predators: we’re giants with ominously fast movements and loud voices. In any interaction with a cat, we need to slow down and talk softly—take our shout down to a whisper—and allow the cat an easy retreat. When an interaction is not going well, it’s okay to stop, reassess, and try again later.

Earlier we discussed how behaviors such as licking, tail wagging, and belly exposure are often misinterpreted as friendly or affection-seeking signals. How can you determine whether your cat truly wants to be petted or is going to deliver a bite that says Please don’t touch me? How do you know whether licking is friendly allogrooming or a nervous displacement behavior?

Observe the rest of your cat’s body language. Are her ears and tail telling you she’s relaxed or worried?

Sometimes there is a lack of congruence in body postures that can be confusing. For example, the tail may say one thing and the ears another. This could indicate that your cat has conflicting motivations or is unsure of how to respond in a given situation. That conflict is frequently an indication of stress. To determine how your cat is feeling and avoid miscommunication traps, read your cat’s entire body and behavior rather than focusing on just one body part or behavior.

Training is a common language that enables humans and cats to communicate more effectively. When our message is clear and the outcome is positive, cats understand and trust our intentions. Although people commonly believe that cats cannot be trained, you might be surprised to learn that cats can be trained in the same way that dogs are. But you must be patient! Just as we cannot expect humans to understand a foreign language without being taught, we cannot expect cats to automatically comprehend what we are saying.

You can teach your cat almost any cued behaviors—some with a practical purpose and others just for fun. These might include “go to your bed,” “sit,” “stay,” and “high-five.” The safest, most effective way to train a cat is using positive reinforcement. For example, you can teach your cat to go to her bed by tossing a treat onto the bed, saying “go to your bed,” and then saying “yes!” and giving another treat when she is on the bed. That way, you are rewarding her for performing the desired response. The more often you reinforce the behavior, the more likely she is to do it in hopes of obtaining the reward.

Rewards might include a treat, a toy, praise, or petting. Which reward you use will depend on what motivates your particular cat. When deciding on a reward, keep in mind that what motivates a cat may be different from what motivates you or another animal. Treats may work for some cats, while others will do anything for petting or the opportunity to chase a toy mouse. (See chapter 6 for more on how cats learn and how you can use training in your home.)

Some humans sit around on the couch all day, while others are constantly on the go. One person lives by the mantra “The early bird catches the worm,” while another may be a night owl. Cats, like people, have individual personalities and interests, which are influenced by genetics, learning, and environment. Although we can make some generalizations about cats of a particular breed, not every cat in that breed will respond in a similar way, and each cat is an individual. Unrealistic expectations will set your cat up for failure.

Dr. Benjamin Hart, DACVB, and Dr. Lynette Hart studied various pedigree cats and ranked their prevailing behavioral characteristics. Abyssinians and Bengals were the most active, while Persians ranked as the least active. Siamese were the most vocal. Familiarity with the general personalities and needs of different breeds can increase the chances of a good cat-owner match. For example, a household or environment best suited for a sedentary cat will not meet the physical needs of a Bengal. Likewise, undesirable behaviors can arise when the environment does not allow ample opportunity for a feline of any breed or type to express her normal behavioral repertoire of scratching, climbing, playing, and hunting.

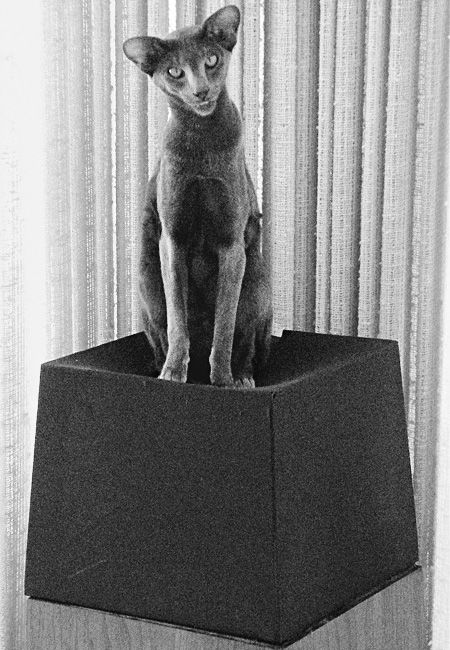

The physical attributes of different cat breeds can affect how we interpret their body language. Brachycephalic, or flat-faced, breeds, such as Persians, Himalayans, and Exotic Shorthairs, may appear stoic and are difficult to read. The former Internet sensation Grumpy Cat, for example, always looked grumpy because of his physical attributes and fixed facial expression. Similarly, it’s hard to tell if a Scottish Fold is pinning her ears back in fear or to evaluate tail carriage in a Manx or Japanese Bobtail, because these breeds lack most of their tail.

This Scottish Fold has small ears that are not as movable as a domestic shorthair’s ears, making it more difficult to read his body language.

Carlo Siracusa

Like people, cats have different tolerance levels for physical affection and handling. Some people enjoy hugs and massages, while others shy away from touch. Some cats seek out and enjoy petting and handling by strangers, while others become aggressive when even familiar people pet or pick them up. Because cats have unique personalities and preferences, it’s important to read every cat’s body language when you interact with her rather than assuming that she will behave similarly to cats you’ve known before. Just because a cat accepts brief physical contact does not mean she wants more. Likewise, a cat who does not like to be cuddled or cradled like a baby can still be a great companion.

Behavior is fluid and may change with the environment, with a cat’s age, or due to pain or illness. Consider the case of Misty. Amy expected Misty to accept petting the same way she always had. But Misty’s back pain changed her willingness to be touched. The bustling and highly active nature of children did not bother her before, but now she perceived their unpredictable movements as a threat. Misty felt safer in her own space, away from the hustle and bustle. Amy noticed this change in Misty’s behavior but did not realize that her avoidance was a sign of pain. If she had understood Misty’s physical limitations, she might have adjusted her expectations about physical interactions. Misty’s reaction would not have surprised her. Instead, she may have been able to avoid triggers and provide a more comfortable environment for Misty.

By recognizing that changes in behavior and communication are often the first signs of illness, we can more actively care for our pets, intervene early, and ensure that all health issues are addressed.

Generally speaking, any unexplained change in physical appearance or behavior can indicate that your cat is ill. Because cats evolved from animals who were solitary prey for larger animals, they can expertly hide signs of illness so as not to show how sick they really are. Early signs of illness are often hard to detect, and your cat’s distress may become obvious only after a disease is quite advanced. By recognizing subtle signs, including those listed here, and consulting with your veterinarian, you can give your cat the best chance at an early diagnosis and successful treatment.

PHYSICAL SIGNS:

Weight change (loss or gain)

Unkempt coat or missing hair

Weakness or loss of muscle tone

Vomiting

Change in the amount, frequency, or appearance of urine

Soft or bloody stools, diarrhea, or constipation

Reluctance to be touched in certain places

Any change in appearance (cloudy eyes, drooling, new or changing lumps or bumps on or under the skin)

Excessive skin twitching

BEHAVIORAL SIGNS:

Change in mood (for example, a once friendly cat becomes aggressive)

Change in activity or energy level:

* Less outgoing and social

* Hiding or sleeping more

* Decreased activity level

* Less interested in play or toys

* Hyperactivity

Increased or decreased vocalization

Altered routines

Changes in sleep-wake pattern

Increased or decreased appetite:

* Dropping food out of her mouth

* Change in food preference (for example, no longer eats dry food)

Increased or decreased water drinking

Difficulty walking, or walking with a crouched gait

Difficulty climbing stairs

Difficulty jumping:

* Prefers to lie on the ground or on lower furniture

* Reduced height of jumping

* Jumping on low objects to reach higher locations

* Pausing to consider the height of a jump

* Loss of catlike grace, including clumsy or heavy landings or pulling herself up rather than jumping

New or changing behavior problems:

* House soiling, aggressive behavior, excessive vocalization

* Problem worsening in frequency or intensity

* Previous behavior problem improves or resolves (for example, no longer jumps on counters, not aggressive because she spends most of the day hiding)

Unless they’re very sick, unwell cats do not appear ill or uncomfortable all the time. Typically, behavioral signs of illness occur intermittently and are therefore easy to miss or overlook. An ailing cat may occasionally greet you at the door or run up the stairs, just not as frequently or easily as she once did.

Given the right motivation and mood, desire may outweigh discomfort. For example, an old, arthritic cat may still jump on the counter despite her pain if there is a good reason to do so (such as to eat off your dinner plate). Slight situational variations can also make a difference. A cat with a painful stomach may not vocalize when you pick her up if you happen to cradle her in a slightly more comfortable way. Rather than focusing on individual events, consider trends, such as increased frequency or intensity of a behavioral sign, when determining whether your cat is ill.

Instead of focusing on one body part or behavior, look at the cat’s entire body when deciphering her feelings. Behaviors have different meanings depending on the context in which they occur. For example, a cat may purr either when she is content or when she is stressed.

Treat each cat as a unique individual, despite your past experience with other cats and knowledge of breed characteristics. Consider your cat’s personality so as to optimize her environment and your interactions.

Remember that not every cat wants to be petted. And some like a little bit, while others prefer more. Where a cat likes to be stroked is also an individual preference.

Respect your cat’s boundaries. Some cats may be more outgoing, social, and confident, while others prefer to have more space.

Pay attention to changes in your cat’s environment and how they could affect her stress levels and the ways she communicates with you.

People around the world list cat purring as one of their favorite sounds. You may be surprised to learn, however, that purring is not unique to domestic cats and does not always mean the cat is happy.

As far back as the early 1800s, scientists such as the British anatomist Sir Richard Owen made a distinction between cats who purr and cats who roar. Most cat species purr, but lions, tigers, leopards, and jaguars do not. These large cats roar, but technically they do not purr. Similarly, other species as varied as bears, raccoons, hyenas, and rabbits make a purrlike sound, but they do not, in fact, purr.

So what is a purr? It’s a continuous sound produced by the rapid vibration of a muscle between the cat’s vocal folds during both inhalation and exhalation. Kittens begin purring around three weeks of age, often while they nurse. Adult cats typically purr in pleasurable situations, including friendly contact with humans and other cats, or when they are anticipating food. However, cats may also purr when they are sick or in pain.

Why do cats purr when they are ill? Depending on the situation, cats may purr not for pleasure, but to voice their desire to be cared for. It appears that cats’ purrs may have different meanings depending on whether they are content or requesting attention and nurturing. Dr. Karen McComb and her colleagues at the University of Sussex in England analyzed recordings of purrs. She found that cats waiting to be fed, a soliciting event, purred differently than cats being petted, a nonsoliciting context. Soliciting purrs contained a high-pitched component that Dr. McComb equated to a hidden meow—an attention-seeking vocalization embedded within the purr. People listening to recorded purrs rated solicitation purrs as more urgent and less pleasant than nonsolicitation purrs.

Other researchers have a different explanation for purring. Dr. Elizabeth von Muggenthaler speculates that purring may be a form of self-healing. Similarly, several studies reviewed by Dr. Wing-hoi Cheung at the Chinese University of Hong Kong found that vibrations at frequencies similar to purring may stimulate bone healing. If this is the case, then purring may be an excellent way for cats to recuperate after a long day of hunting, and it may further explain why humans have a natural affinity for purring.

Cats rely on different forms of communication than humans. We are primarily verbal, while cats use tactile, olfactory, and visual signals in addition to vocalizations. Listen to your cat with all your senses to better understand and anticipate her reactions.

We can’t speak cat, but we can learn to read our cats’ body language. Cats alter their body postures depending on how they feel. Their eyes, ears, tail, and body will all give you information, but you need to pay attention to the cat as a whole to really understand her mood.

Avoid treating cats like small dogs. Some behaviors, like rolling over and wagging their tail, may look similar but have completely different meanings for cats.

Use reward-based training to teach cats cues. This will allow you to communicate using a common language.

Your cat’s behavior will change with age, illness, and environmental conditions. Being familiar with the normal behavioral and communication strategies of your cat will enable you to notice subtle changes and detect health or behavior problems at an early stage.

Cats are sensitive to large gestures, fast movements, and loud voices. We need to slow down and reduce our shouts to a whisper.