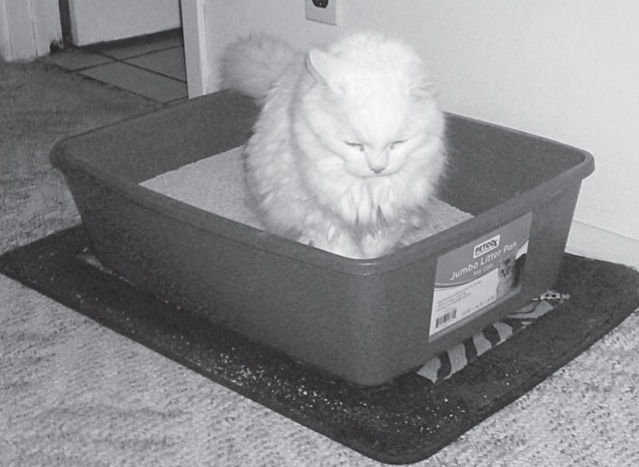

Cats sniff and dig before eliminating in their litter box.

Sabrina Poggiagiioimi

Sabrina Poggiagliolmi, DVM, MS, DACVB

Stella and her owners came in for an appointment because she was refusing to enter her litter box and was urinating and defecating all around the house. Because of her elimination habits, Stella was confined to the finished basement, which had easy-to-clean tile flooring. She was a healthy young cat; why was she refusing to use the litter box?

The family had adopted Stella after finding her as a stray kitten in a parking lot, and they wanted to offer her a great home. Stella’s owners were not what you might call cat people; they’d never had a cat before and didn’t really know much beyond the very basics of what a cat needs. Unfortunately for Stella, they were not aware that they had to scoop her litter box at least twice a day so that it would always be clean. They thought just dumping all the contents of the box once a week would be enough.

Fortunately, when they brought her to the veterinarian, she asked them about their litter box hygiene routine as well as Stella’s bathroom habits. The veterinarian recommended that they start scooping Stella’s box morning and evening, every day, so that Stella always had a clean toilet. This was all it took to solve the problem, and Stella was given full access to the house again. Her time in jail was finally over!

Cats are famously clean creatures, but we sometimes forget that this also applies to their toilet habits. My mother’s cat, Margot, used the flowerpots on the balcony whenever my mom got lazy and started scooping the box every other day. To make my clients understand how important it is to keep a cat’s litter box clean, I ask them if they would use a public restroom where the toilets had not been flushed. Of course they wouldn’t! So why should they expect their cats to use a dirty box?

Cats inherited a natural preference for sandy elimination areas from their desert-dwelling African ancestor, Felis silvestris lybica. This explains why it is easy to train any kitten or cat to use a litter box filled with a fine-textured material (usually litter). In fact, many people choose cats as pets because they are known to be clean animals who need little training to use the litter box.

Normally, adult cats urinate two to four times a day and have a bowel movement (defecate) at least once a day (the frequency may vary depending on their diet). During urination, both female and male cats sniff and dig a hole, squat over it (it looks like they are sitting, but their hindquarters are not fully touching the ground), and deposit their urine. Once the bladder has been voided, most cats cover the hole with litter and then leave.

Cats sniff and dig before eliminating in their litter box.

Sabrina Poggiagiioimi

Once the cat has found a good spot in the box, he digs a shallow hole and then squats to start urinating. After the action is finished, some cats sniff again and cover the spot by raking litter over it.

Sabrina Poggiagliolmi

When defecating, cats prepare the chosen area the same way they do when urinating. They assume a similar position, too, but their hindquarters are not as close to the ground and their back is more curved. After defecating, cats may or may not cover their feces.

Cats also assume a squatting position to defecate, but their hindquarters are not as close to the ground and their back is more curved than when they are urinating.

Carlo Siracusa

House soiling (that is, depositing urine and/or feces outside the litter box) is the number one feline behavior problem seen by both veterinarians and veterinary behaviorists in the United States. House soiling, including urine marking, can be a cat’s response to issues with the litter box (location, accessibility, cleanliness), changes in the household environment, or other events that he might find stressful.

Many cats soil outside the litter box for the sole purpose of voiding the bladder and bowel in a different location. Also, some cats do not like using the same box for urination and defecation. In these cases, the cats are simply using a toilet other than the one their owner wants them to use. The toileting cat typically eliminates regular amounts of urine or feces in one or several spots around the house, using a squatting posture.

A similar but separate problem is urine marking. When cats mark with urine, they usually spray a vertical surface by backing up toward it. The body posture they assume when they spray is unmistakable and straightforward: They stand erect, hold their tail straight up, and squirt a small amount of urine on the chosen spot. Often the tip of their tail quivers as they squirt. Sometimes cats tread with their back paws while spraying. Usually they sniff the selected spot before marking; some cats also sniff after depositing urine.

Some cats may urine mark on horizontal surfaces. In this case, they usually assume a squatting position, sometimes with their tail up and their feet treading but not always. (Some cats start out squatting and end up standing.) Generally, less urine is expelled in marking and spraying than in urination, so the urine mark is smaller than a full emptying of the bladder, but that is not always the case.

The frequency of urine marking depends on hormonal status, stress factors, and, in some cases, litter box issues. Both male and female cats urine mark, but intact (unneutered) males spray more frequently than neutered males or intact females. They use this behavior to leave a clear message: to define their territory, to make other individuals aware of their presence (particularly important for sexually intact cats), or to make marked areas feel safer and more familiar. It is interesting to note that cats who urine mark still use their litter boxes for both urinating and defecating.

Marking with feces, called middening, is rarely seen in cats. Usually the feces are deposited in visible and socially relevant areas of the house, such as on a couch, also with the goal of delineating territory or leaving a message for another cat.

Is my cat being spiteful or vengeful when he eliminates outside the litter box? As offensive as finding cat urine around your house can be, your cat is not deliberately engaging in a feud with you. Try not to take his bathroom habits personally. This is not about you; it is about his individual preferences or his attempts to tell you something.

First and foremost, your cat may be sick. There are many illnesses (discussed later in this chapter) that typically manifest as changes in litter box habits. He also may be unhappy about where the litter box is located or something having to do with the box itself. He may be stressed by and anxious about his environment. Remember, your cat did not decide where, how, and with whom he wanted to live; you decided for him.

It is the responsibility of caregivers (both owners and veterinarians) to understand why a cat is eliminating outside the litter box and to find a solution to the problem that is respectful of the cat’s well-being. It is very important for you to avoid anthropomorphizing your cat and to realize instead that he is house soiling out of anxiety, not out of spite or a desire for revenge.

Is urine marking a sign of dominance? Your cat is an intriguing and elegant creature who possesses fascinating communication skills. Among these skills, marking plays an important role. You may have noticed that he marks his environment (also known as your home!) in different ways: with his chin, with his head and the sides of his face, with his whole body, with his paws, and . . . with his urine.

Urine marking is one of the many behaviors cats use to convey a message, perhaps Single tabby male seeks calico female. Or Beware: cat on the premises! Or even That new baby is stressing me out!

By contrast, behaviorists define dominance as controlling access to resources. Your cat is not trying to control access to anything by depositing his urine outside the box. Dominance is not the issue (and, more broadly, not an issue in cat-human interactions at all).

Should I reprimand my cat when he eliminates outside his litter box? No. Punishment, including verbal reprimands, is unlikely to change your cat’s elimination habits. Keep in mind that poor litter box management, fear, anxiety, and stress are among the most frequent causes of feline house soiling. Punishment can actually exacerbate the situation and make the house-soiling problem worse.

As frustrating as it is to find urine or feces on your favorite chair or your brand-new carpet, the best thing you can do is simply clean it up. Showing the urine or feces to your cat or, worse, rubbing his nose in it will only make him afraid of you and more anxious about his eliminations in general.

To teach my cat to use the litter box, should I lock him in the bathroom with the box? While you work on the treatment plan for house soiling with your veterinarian, do your best to prevent your cat from eliminating outside the litter box. During the initial stages of treatment, this may include confining the cat to a safe and comfortable room with a large litter box and all the resources he needs (things to eat, drink, scratch on, perch on, and play with) when you cannot actively supervise him.

When you can supervise your cat, allow him to spend time outside the room. If you catch him sniffing around to find a spot to eliminate or getting into position to do so, call him with a happy voice and ask him to come to you. When you get his attention, toss him a treat and then send or bring him to his safe room with the litter box.

Keep in mind that some cats become even more stressed when confined, so confining them is not appropriate. Others will use the litter box when confined but continue to house soil when let out, because the underlying reason for the problem has not been addressed. If this is the case with your cat, thinking about what is different in his safe room will give you clues to what the real problem is.

Why bother? Nothing will ever change. Don’t despair! Feline house soiling is actually among the behavior problems with the best prognosis for improvement. By choosing the right behavioral and medical treatment plan and, if necessary, the right behavioral drug, house soiling can be cured or, at least, significantly reduced. In a study by Dr. Patricia Pryor, DACVB, and her colleagues, one treatment plan for urine marking (involving the number of boxes, cleaning the boxes, and other factors) decreased house soiling in all of the cats by 90 percent or more. Always consult with your veterinarian or a veterinary behaviorist when your cat is eliminating outside the litter box.

Urination: The act of fully emptying the bladder. A healthy, nonmarking cat usually squats while urinating.

Defecation: The act of eliminating feces.

Urine marking: The act of depositing urine, usually by spraying on vertical surfaces, with the intention of leaving a visible and smelly signature (I was here; please take note). A cat typically stands and backs up to a vertical surface while keeping his tail straight up, with the tip quivering. Sometimes a cat may squat to mark on a horizontal surface. Whatever position the cat chooses, he typically eliminates a smaller amount of urine than when he totally empties his bladder.

Middening: The act of depositing feces with the aim of sending a social message; this is rarely used by cats.

Aversion: A strong dislike. The usual aversions that may keep a cat from using the litter box are location of the box, size of the box, cleanliness, and type of litter.

Preference: In this context, “preference” refers to the surface a cat prefers to eliminate on or in for safety, cleanliness, privacy, quiet, comfort, or other reasons.

House soiling: Depositing urine or feces outside the litter box, but not with the intention of marking.

When a cat stops using his litter box, he is at risk for abandonment, relinquishment, or, even worse, euthanasia. This is truly heartbreaking, especially because eliminating outside the litter box is often a sign of a medical problem. This is particularly true when cats defecate outside the box. If your cat stops using the box, the first thing he needs is a complete checkup.

To get to the root of the problem, your veterinarian will perform a thorough physical examination, blood work, and possibly X-rays or ultrasound imaging, as well as urine and fecal testing. It’s a common misconception that if there’s a medical cause of house soiling, it’s usually a urinary tract infection. In fact, urinary tract infections are not common in cats, and other urinary tract diseases account for only a portion of the possible causes of house soiling in cats. Any medical problem that causes distress, discomfort, pain, or an increase in the volume or urgency of elimination can cause or contribute to house soiling.

If your cat is senior (over ten years of age) or geriatric (fifteen years or older), a neurological evaluation and an orthopedic examination can help rule out joint, muscle, and nerve conditions that may cause discomfort when climbing in and out of the box or posturing to eliminate. Hair loss on the lower abdomen could be a sign of bladder pain in a cat of any age.

The results of the veterinary exam will determine whether any further testing is needed. If there’s a medical cause, it must be addressed and managed, or your cat will not stop house soiling. Even when the medical problem is managed, however, some cats may continue to house soil or mark, because they learned to eliminate elsewhere while they were sick and now have a preference for that spot. In that case, you’ll need to combine both a medical and a behavioral approach.

Urinating or defecating outside the litter box may be the first and only sign of a serious health problem. That’s why a veterinary checkup is always the first step when your cat stops using the box. Medical problems can arise suddenly, so even if your cat received a clean bill of health from his veterinarian just a few months ago, he may have developed an illness since then. Medical problems that commonly lead to feline house soiling include:

Crystals or stones in the urinary tract

Feline interstitial cystitis, or FIC (also sometimes called Pandora syndrome)

Cancer

Kidney disease

Diabetes

Hyperthyroidism

Intestinal parasites

Degenerative joint disease (including arthritis)

Impacted anal glands

Rectal strictures

Pelvic or tail fractures

Diarrhea

Constipation

Hormonal disorders

Bacterial infections

After any medical problem is ruled out, you and your veterinarian will need to determine whether it’s a toileting issue or a marking issue. Collect as much information as possible about the elimination problem before visiting your veterinarian. This will help you both figure out what is causing the problem.

Start by thinking about the litter box, and make sure you can answer the following questions. All of these details are important because they matter deeply to your cat.

How big is the litter box? Is it uncovered or covered? With or without a collar or a liner?

How many boxes do you have, and where are they?

What is the litter made of? Is it clumping or not? Scented or unscented? How much litter do you put in the box?

How often do you scoop the box? How often do you dump all the litter and clean the box? What kind of cleaner do you use?

Have you recently made any changes to the box or the litter?

Next, think about your household, including its inhabitants and their relationships.

How many adults and children live in your home? How many cats, dogs, and other pets? How do they get along with the cat who has the problem?

Does your cat have access to the outdoors?

What is his daily routine of eating, playing, and socializing?

Gather information about your cat’s typical behavior in the litter box.

How often does he eliminate each day?

Has he ever strained, vocalized, or seemed startled during or immediately after eliminating?

Does he sniff and dig before eliminating in the box?

Does he cover his waste when he’s done, or does he seem to jump out as quickly as he can? Do you notice that he scratches the walls, floor, and sides of the litter box, but avoids scratching the litter itself?

Does he ever perch on the sides of the box to eliminate, rather than standing inside it?

Establish the frequency of the unwanted elimination. This will help you and your veterinarian track improvement.

How often do you find urine or feces outside the litter box?

When did it start, and how long has it been going on? Did it start suddenly?

Was it initially associated with any medical problem? Keep in mind that a single painful event in the litter box can create a long-lasting aversion.

Did it seem to coincide with a specific event or change in your household? Changes in the cat’s environment (change in your work schedule, vacation, new furniture), recent additions to the household (roommate, spouse, baby, new pet), or losses to the household (someone moving out, the death of another pet or person) may be contributing to the current problem.

Where in the house does the cat eliminate? Cats who urinate on their owner’s bed or belongings might suffer from separation anxiety or be at odds with someone in the household.

Does the urine seem to be in large puddles on the floor (toileting) or smaller amounts on vertical surfaces (marking)?

Make a sketch of the floor plan of your home, noting where the unwanted elimination has occurred and where litter boxes, food and water dishes, feline resting places, perching sites, scratching posts, and play areas are located. Understanding how your cat uses each part of your home will help you and your veterinarian understand what is motivating the cat to eliminate in certain areas.

If you want to convince your cat to stop using your home as his personal scent canvas and resume using his litter box, you must first figure out why he stopped using the box. As mentioned previously, there are many reasons that a cat might stop using a litter box. Let’s take a look at the most common ones.

Size and style matter. The box may be too small, too hard to climb into, or too closed in for your cat. Many cats will avoid a covered box, especially if you forget to scoop it, because all the bad smells are trapped inside—similar to how you might avoid a Porta Potti unless you feel super desperate! They may also avoid a box if they have been ambushed by other cats when exiting the box. With a covered box, or one stuck in a closet or cabinet, they cannot clearly see if anyone is lurking nearby—and can’t escape if someone is.

The box may simply not be scooped or cleaned often enough. Just as you would not want to use an unflushed toilet, many cats will avoid using a box containing their own or another cat’s excrement. There may also be a liner in the box that the cat finds unpleasant because he doesn’t like the feel of plastic under his paws when he scratches in the box, or he may have gotten a claw stuck in the plastic.

Some cats prefer certain types of litter over others. If the litter is not the fine, sandy texture to which your cat is naturally drawn, he may seek this substrate elsewhere, such as the soil in potted plants or gravel in gas fireplaces. Large, hard pellets or crystals may be less appealing than finer, clumping clay. Nonclumping litter holds on to urine and feces, may remain wet when soiled, and will retain odors unless the entire contents of the box are dumped almost daily.

Some cats have unusual substrate preferences, such as hard surfaces, while others seek out the softest, most absorbable options, such as carpets, towels, and baskets full of laundry. It has been hypothesized that some cats may develop an aversion to typical litter because of a previous painful elimination experience, such as during a bout of constipation or bladder stones.

Cats are also easily offended by strong smells, so your cat may not like a heavily perfumed or scented litter. (Litter is scented to appeal to humans, not cats!) Litter that is too shallow or too deep in the box may also be an issue.

The litter box is not our most attractive household feature, so we humans often choose locations that are far away from our main living space. This requires the cat to navigate through different floors, scale various barriers, and go to darker, more dungeonlike areas of the home. While this may not be a major issue for a young, confident kitty, if an older or more timid cat, or one experiencing pain, is not willing (or able) to work that hard, he will choose alternative areas for toileting.

In some cases, the box may be too close to the cat’s food and water bowls, making him less likely to soil in that area. Frightening experiences in a location, such as a furnace or a freezer starting up, an ambush or blocking by another pet, or the loud buzz of a dryer cycle ending, can deter a cat from returning to a certain area.

Stress is one of the main triggers for feline house soiling. Your cat is a creature of habit—just as some humans are—and any change in his environment may trigger anxiety. Anxiety is a reaction of apprehension or uneasiness to an anticipated danger or threat. Any addition or loss to the household, such as a new pet (even if you’re only fostering), a newborn child, a new spouse or roommate, or the death or departure of a person or another pet, may be enough to trigger house soiling.

Cats can develop anxiety when they move to a new home or when they are having trouble with other household pets, their human family members, or visitors to the home. New furniture, with its unfamiliar appearance and smell, may trigger anxiety. The proximity of outdoor cats (feral or semi-feral) or wild animals can be perceived as a threat. A change in your work schedule or a prolonged absence when you go on vacation may also trigger anxiety.

In this case, house soiling is just one of the possible signs of anxiety. Others may be:

Frequently pulling his ears back

Dilated pupils in well-lit settings

A crouched body posture

Tucking his tail

Avoiding interactions with people or pets in the home when he was social in the past

Frequent hiding

Increased vocalization, such as meowing or yowling

Frequent regurgitation of undigested food

Poor coat condition or matting

Stress activates a physical response, triggering the release of substances such as hormones, neurotransmitters, and biological regulators of inflammation and pain. Some of these substances increase the vulnerability of the bladder to pain-inducing compounds in the urine. This process causes the pain and discomfort observed in cats affected by a form of bladder disease called feline interstitial cystitis (FIC). Studies have confirmed that stress is the main cause of FIC, no matter how innocuous some of the causes of that stress—new furniture, changes in work hours, visiting friends—may seem to us. Each cat is an individual, and the responses to various stressors will differ from cat to cat.

Due to hormonal influences, it is normal—almost expected—that unneutered cats (males more than females) will spray urine to communicate their sexual status. However, if your neutered cat is marking rather than toileting, consider that the most common cause of this behavior is social conflict within the household (with other cats, other pets, or humans) or outside the house (cats or wild animals passing close enough for your cat to see, hear, or smell them).

If your cat has developed the habit of marking surfaces with his urine, you may find his “messages” near windows and doors through which he has spotted animals outside. By leaving these smelly signals in these spots, he is signaling potential intruders to stay away from his space. He may also prefer to leave his messages on appliances, such as microwaves, stereos, and radiators, or on objects carrying your smell, such as dirty laundry, personal items, the sofa, or your bed.

Cats who are stressed about litter box hygiene or other cats using their litter box may spray urine against the walls of the box, rather than squatting to urinate. In rare circumstances, some cats prefer to adopt a standing, spraying posture for toileting in the litter box.

Cats who tend to spray within their own space, rather than along its boundaries, may be experiencing a conflict with individuals living in the house. Or they may be offended by scents on items you have brought into the home—anything from new furniture to grocery bags, new shoes to the shoes you wore to volunteer at your local animal shelter. In this case, the object that brings unknown odors into the home is challenging his comfort and safety, and that scent needs to be replaced with his own familiar smell.

Although it’s rare, humans can be targeted as well. We may, in fact, make a cat uncomfortable simply with our presence or smell.

The 2014 AAFP and ISFM Guidelines for Diagnosing and Solving House-Soiling Behavior in Cats (https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/1098612X14539092) highlights how important it is to offer what the American Association of Feline Practitioners and the International Society of Feline Medicine call the “optimal litter box” to your beloved kitty. The goal is to make the litter box extremely attractive.

Before we get into what the research tells us about litter box preferences, though, remember that aversions and preferences are individual, and while studies show that most cats tend to dislike or like a specific option, your cat may very well prefer the opposite. So, if your cat regularly uses his very large but covered litter box with scented, pelleted litter, you don’t need to replace it. If you have doubts, you can check his preference by adding another litter box with different characteristics to see if he prefers the new one to the old one.

Generally speaking, the number of the boxes should equal the number of cats in the home, plus one additional box. This means that if you have one cat, he should have at least two boxes. Why? He may not like using the same box for urination and defecation or may prefer not to use a box that already has urine or feces in it (cats are very clean animals, remember).

If you have several cats, the bare minimum number of litter boxes should be equal to the number of groups of cats who get along well together. So, for example, if you have seven cats and two of them are best buddies, another two are always together, and the rest form their own little family of three, then you have three groups and should have a minimum of three litter boxes, but ideally eight. If all the cats live in their own separate areas, especially if they do not move around the home much, you need a box where each cat lives.

The boxes should be placed in different rooms, to avoid ambushes from bully cats who guard all the resources, and on different levels (if the cats are living in a multistory house), to make them more accessible. Avoid noisy rooms (such as the laundry room, where the washer and dryer are located) or congested areas (for example, near the front or back door). Also keep the boxes away from young children and the rooms where they play. These kinds of locations could scare the cats and force them to look for quieter places to eliminate.

All the boxes should be easy to access. Avoid “hiding” a litter box in a small cabinet or closet that is accessible only through a flap or a crack in the door. Choose well-lit rooms as opposed to dark corners. Avoid rooms whose doors are often closed, where cats may be shut out from the box. Also avoid placing boxes downstairs in the basement or upstairs in the attic, especially if you have senior cats or very young kittens, who may find these locations challenging to reach.

A larger box gives the cat the possibility of finding areas in the box that are not soiled. A popular guideline (though not backed by research) is that the box should be one and a half times the length of your adult cat (from the tip of his nose to the end of his rump) in order to give him enough room to dig, posture, and cover his eliminations.

Plastic storage boxes, appropriately modified to provide easy access, make great litter boxes. They are inexpensive, large, deep, and easy to clean. And the high sides help keep everything inside the box.

Craig Zeichner

Depending on the size of your cat, you may find the “jumbo” boxes available in stores to be too small. Large plastic storage boxes make perfect alternatives and come in many more sizes. Also consider the cat’s age when choosing a litter box. The height of the sides may need to be adjusted for a kitten, an adult, or a senior. An older cat affected by a joint disease or other painful condition may benefit from having a little ramp or one side of the box cut down to make access easier.

Most cats prefer an uncovered box, because a cover traps odors and prevents visual access to their surroundings. But some cats prefer a covered box, and others have no preference at all. Some uncovered boxes have a plastic collar or shield to help keep litter inside. While this type of box may keep the surrounding space tidier, it may also decrease access to the box and reduce the space your cat has to dig, sniff, and squat. Both a box with a collar or shield and an covered box may be problematic if your cat is very large or obese. Regardless of whether the box is covered or uncovered, the most important factor is that you scoop out the urine and feces every day. A study by Dr. Debra F. Horwitz, DACVB, found that not cleaning the litter box daily, as well as using a scented litter, is more commonly associated with house soiling than using a covered litter box.

Research has shown that most cats prefer fine-grained, unscented, clumping clay litter. This makes sense, because domestic cats are descended from a desert-dwelling ancestor who eliminated in fine, dry sand and soil. Of course, there will always be exceptions, and it’s your cat who should get to choose the litter, not you.

Aside from traditional clay litter, clumping litter is now made from grass, corn, or other materials. These products represent a greener option and are gentler on your cat’s paws and nose, as they are usually less dusty and dehydrating than clay litter. However, any litter made from a food item poses the risk that your cat may try to eat it. Monitor closely when first using a food-based litter, and avoid this type of litter if your cat has a history of eating things he shouldn’t.

Grass-based clumping litter is natural, nontoxic, biodegradable, and softer and gentler on your cat’s feet than traditional clay clumping litter.

Cario Siracusa

If your cat has developed a litter aversion (refusing to use the litter box or touch the material inside), offer him different types of substrates (litter, sand, soil) or different kinds of litter to identify one that he will accept. Do this by setting out a litter box “cafeteria”: several boxes in the same location filled with different litter materials. How will you know if your cat doesn’t like a litter you are offering? A study by ACVB diplomates Dr. Wailani Sung and Dr. Sharon Crowell-Davis found that the time a cat spends digging in the litter box can be used as a way to test litter preference: the less digging, the less he likes the litter.

This is when it is truly important to remember how clean and particular your cat is. Boxes must be scooped at least once a day, but twice a day is much better. When I am home, I scoop my cats’ boxes as soon as they use them (sometimes it’s more than twice a day). Any time you remove litter clumps, add a little more litter to the box to maintain the desired depth of at least one and a half inches.

Change the litter completely at least once a month if it’s a clumping type, even more frequently if it doesn’t clump or if more than one cat uses the same box. Dump out all the litter and wash the box with warm, soapy water. Let it air-dry, preferably in the sun, which is a natural deodorizer.

I do not recommend using detergents or disinfecting cleaners because they contain strong chemicals that can leave behind unwanted and repulsive scents (to your cat’s nose). Research by Dr. Nicholas Dodman, DACVB, and his colleagues found that cats show less dissatisfaction with their litter box and fewer house-soiling and marking behaviors when the box is odorless.

Big and roomy—at least one and a half times the length of your cat, with lots of headroom if it’s covered

Easy to enter and exit

Scooped at least daily

Filled with at least one and a half inches of clean, dry, soft, fine-grained, unscented litter

Preferably no liner, collar, or cover

Smells like nothing at all

Located away from food and water, but still in the cat’s core area

In a quiet spot, with minimal human and pet traffic

Not hemmed in, blocked off, or inside a closet or cabinet, so the cat can see who is approaching

Feline interstitial cystitis (FIC) is an inflammation of the bladder without any identifiable cause. Affected cats may experience a wide range of symptoms, including increased frequency of urination, pain when they urinate and possibly at other times as well, urination outside the litter box, blood in their urine, personality changes, and excessive grooming of the hair on the abdomen, likely as a result of bladder pain.

Recent studies suggest that FIC appears to be associated with a series of complex interactions between the nervous system, the adrenal glands, and the bladder. There may be a genetic component, meaning some cats may be predisposed to develop FIC, but a cat’s environment and stress level clearly play a role as well. The goal of treatment is to relieve pain and reduce stress.

If your cat exhibits any of the signs mentioned here, you should take him to your veterinarian immediately for a full physical examination. These are also signs of numerous treatable medical conditions that can have serious complications if left undiagnosed and untreated.

There is no specific test for FIC, so the diagnosis is made when all other medical problems have been ruled out. That does not mean, however, it is not a real medical condition.

Studies of cats with FIC have found that it’s often triggered by environmental stressors. The most common triggers are conflicts with either humans or other cats in the household, although anything that can stress a cat can trigger the problem. Effective treatment involves addressing the cat’s environment, changing his diet, controlling his pain and bladder discomfort, and increasing his water intake. As first described by Dr. C. A. Tony Buffington and colleagues, this multimodal approach addresses the environment and helps prevent recurrence. When only medical therapies are used to treat FIC, symptoms often return.

Stress increases when cats have no control over their environment. This lack of control occurs when cats experience a change in routine or when new pets or humans are introduced to the household. It’s always best to keep a consistent routine that includes playtime, feeding, and regular interactions.

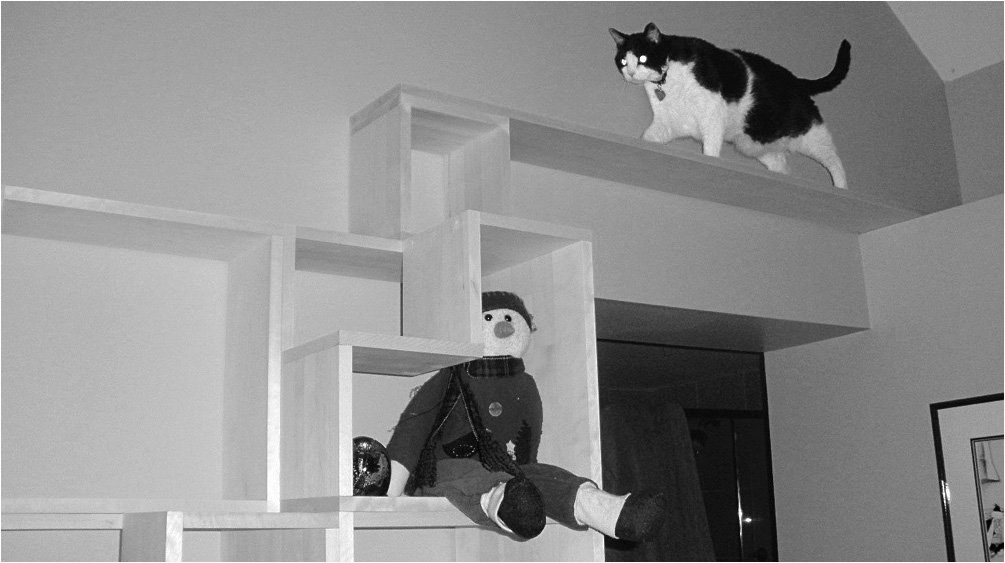

Hobbes has a habit of spraying urine when he is stressed out. This elevated perch gives him a safe vantage point away from household stressors and his feline housemates.

Anne Gaiiutia

One good way to give your cat some control over his environment and decrease his stress is to provide him with a few safe areas that he can retreat to. These will allow him to observe his surroundings and have time to himself. If you have many cats in your household, you’ll want to increase the amount of three-dimensional safe space by creating perches, ramps, and elevated walkways so the cats can avoid one another when they feel it is necessary.

Environmental enrichment is an important part of this approach. (See chapter 3 to learn more about all the ways you can enrich your cat’s environment.) While it may be tempting to make all of these changes at once, it’s better to make them gradually to allow your cat time to adapt. Even positive changes to the environment can be overwhelming for a cat.

Avoid punishing your cat if you find him urinating outside the litter box. Yelling or physically hitting him will only increase fear, anxiety, and distress and make the problem worse.

Although it may seem contradictory for a house-soiling cat to increase his water intake, it is an important part of treating FIC. Add more water bowls around the house and wash them daily. Make sure the bowls are wide enough that the cat’s whiskers don’t touch the sides. This will make the bowls more comfortable for him to drink out of and encourage him to drink more. Whereas some cats will regularly drink out of bowls, others prefer running water. For these cats, and for the freshest water, consider providing a kitty fountain or allowing them to drink from a faucet.

First of all, take a deep breath. Feline house soiling is a frustrating and embarrassing problem for many cat owners. There is hope, though, to get your cat back on track for more desirable litter box habits. As you get started, you’ll want to keep his needs in mind. After all, the box is for him.

You’ll also have to be extremely patient and committed. Your cat will need time to learn that the box is a comfortable place to go when he needs to empty his bladder and bowels. Sometimes, the problem has an easy solution; other times, it may be more complicated to restore regular litter box use.

Be aware that cats may choose to eliminate on soft substrates such beds, pillows, couches, carpets, and rugs. These spots are pleasant to the touch and magically absorb urine—no digging or covering required. In 2002, Dr. Stefanie Schwartz, DACVB, published a retrospective study in which she determined that cats with separation anxiety may urinate on their owners’ beds when they are left home alone. It’s been theorized that this may be because they take comfort in their owners’ scent.

To keep your cat from soiling the same spot over and over, you’ll need to clean the places where he has toileted and prevent access to them. Use a product specifically designed to clean cat urine. A study by Dr. Bonnie Beaver, DACVB, and her colleagues evaluated how effective eleven cleaning products were in getting cat urine smell out of carpets and found that many of the products specifically marketed to eliminate cat urine odor are effective and prevent the return of the smell. Avoid products that contain ammonia or chlorine (such as bleach), which will attract the cat back to these spots.

If your cat is marking and targets appliances, you may have to clean each soiled spot more than once. The heat generated when the appliance is turned on may make the smell return, and the cat will feel the need to mark it again.

If your cat has been urinating on a soft substrate, such as carpeting or upholstered furniture, make sure these items are thoroughly cleaned, ideally by a company that specializes in cleaning pet stains and odors. If the substrate can be removed, such as a rug, take it away until your cat’s house soiling has completely resolved.

If possible, prevent access to the areas your cat has been soiling. Close doors or put up baby gates to keep him out of those areas. If you can’t close an area off, cover the spots where he has been eliminating with aluminum foil or plastic wrap, or use a plastic carpet runner with the nubs turned up. Lemon- or orange-scented potpourri should keep your cat away as well, but make sure to put the potpourri where he can’t eat it, because it can be toxic. Or try putting his bedding or his food and water bowls in those areas, because usually cats will not eliminate where they eat, drink, or rest.

Another idea is to try putting a litter box right on the spot, then gradually moving it to a more desired area. (“Gradually” means that after ninety days of consistent use of the box in that spot, you can start moving it one inch a day.)

Be aware that when you remove access to one spot, your cat may just use another one. So you will still need to address the cause of the problem with an optimal litter box and the other suggestions in this chapter. Preventing a return to the “scene of the crime” will only stop the cat from going in that spot out of habit. The goal of any treatment should be to resolve what is triggering your cat’s behavior and make his environment as enriching and stress-free as possible. (See chapters 5 and 9 for more information about sources of stress for cats.)

Studies have shown that environmental enrichment can help prevent recurrent house soiling. To keep your cat healthy and comfortable in his environment, make sure there are multiple feeding stations, perches, scratching posts, toys, and resting areas. As we saw in chapters 3 and 6, daily play and interaction with you can reinforce the human-animal bond and make your cat’s environment more predictable and pleasant.

If your cat loves to spray in his box or urinates standing up, use a plastic storage box with high sides as a litter box. Just cut down one side so that your cat can easily get in and out (see the photo earlier in this chapter).

Or make an L-shaped litter box by placing a large litter box on the floor, then standing another box up on one of its short sides and inserting the horizontal box into it. This arrangement will contain the urine.

If the presence of outdoor pets or wildlife is triggering house soiling, blocking visual access to the outside world may be enough to prevent it. Keep the blinds down or use thick curtains or opaque window film to prevent your cat from seeing outside. There are also many humane ways to keep unwanted visitors out of your yard. The feral cat advocacy group Neighborhood Cats offers a number of solutions that will work just as well for raccoons as they do for cats (see “Keeping Cats out of Gardens and Yards,” www.neighborhoodcats.org/how-to-tnr/colony-care/keeping-cats-out-of-gardens-and-yards-2).

An L-shaped litter box, made from two large litter boxes, can accommodate cats who spray in their boxes.

Debra F. Horwitz

Often our first response to an unwanted behavior in our cats is to punish the culprit—at least by yelling at them. Refrain from reprimanding, scolding, or in any way punishing your cat, even if it is really tempting. Punishment will only make the problem worse, because it will add more stress to the situation. Plus, your cat may now feel threatened by you and respond to your aggressiveness with fear-related aggression (see chapter 7).

When you need to change soiling or marking behavior, start by making sure your cat has what he needs—an optimal litter box—and then rewarding him for using it. Rewards (food, praise, affection, toys) reinforce desired behaviors. When you show kindness toward your cat, you will strengthen your bond with him, and everyone will be less stressed—including you.

When you use positive reinforcement, your cat will become more comfortable around you and feel more at ease in his own skin, and thus less prone to display the unwanted behavior. Also, he will retain his new learned behavior for a longer period of time. Not bad!

Unfortunately, there is no magic pill or quick fix to treat any behavior problem. If anxiety plays an important role in your cat’s house soiling, you might consider medication, pheromone therapy, or natural supplements. But if the problem is a dirty litter box or access blocked by a bully cat, medication will not change the situation. And medication will never work on its own. The goal of any medication is to lessen your cat’s anxiety so that he can be more receptive to all the other recommended solutions. Medication should always be considered an adjunct to behavior and environmental modification, never a replacement for it.

Be aware that not all cats will respond to the same medication in the same way, and that most of the drugs used for this issue will take four to six weeks to reach their full effect. Among the different house-soiling problems, urine marking seems to respond well to medication.

Synthetic feline facial pheromones also can be used to help cats with house-soiling issues. They are available on the market as plug-in diffusers and sprays.

Diffusers increase comfort in the areas where they are placed and may be of most benefit in rooms with litter boxes, high traffic, or other stressors.

Sprays can be applied to new items to make them more familiar to your cat.

Natural supplements that contain casein (a milk protein), whey (another milk protein), magnolia (Magnolia officinalis), Phellodendron amurense (Amur cork tree), and L-theanine (an amino acid) may have a calming effect on cats with house-soiling problems, but there is no scientific evidence to confirm this.

Take your cat to see his veterinarian as soon as house-soiling problems arise to rule out possible medical conditions and address them.

House soiling can be treated.

House soiling is not a result of spite or a display of dominance.

Offer your cat an optimal litter box.

Good litter box hygiene is extremely important to your cat.

Remove all triggers of your cat’s anxiety.

Pay attention to your cat’s needs and preferences.

Medication may be appropriate to help your cat deal with stress, but it should be combined with behavioral and environmental modification.

Avoid punishment.

Be patient and consistent in implementing the necessary changes.

DR. AMY L. PIKE, DACVB, and DR. KELLY BALLANTYNE, DACVB, also contributed to this chapter.