Eliciting play is an effective way to promote positive interactions between cats.

Leticia Mattos De Souza Dantas

Leticia Mattos De Souza Dantas, DVM, MS, PhD, DACVB

Lili was a nine-year-old cat who loved her life with her owner, Maria. One day Maria was browsing a list of adoptable cats on a rescue website and saw a beautiful younger cat who looked as if he could have been Lili’s offspring. Tiger was a two-year-old stray who had been picked up by the rescue group. Maria hoped he would become Lili’s best friend.

When Maria brought Tiger home, Lili seemed to be okay with him initially. She got along with other cats she’d lived with before, so Maria didn’t worry too much about introducing the two cats slowly. Tiger acted shy and hesitant but did not show any obvious signs of fear or aggression. But one day, during an attempt to get them to like each other by feeding them together, Tiger approached Lili’s food bowl, and she attacked him. She was out of control, hissing and growling. When Maria approached, Lili bit her on the leg, causing a deep wound. Maria separated the two cats.

As time went on, Tiger and Lili learned to coexist separated by a gate. But they were never friends, and Lili continued to hiss and growl at Tiger through the gate. Then Tiger developed a bone marrow disease. When he was under stress, his symptoms became worse. Maria thought Lili’s aggression was taking a toll on Tiger’s health and eventually separated the two cats completely. This saved them both from living with chronic stress.

Then Lili passed away. Understanding that Tiger would have a difficult time living with another cat and that his illness was worse when he was stressed, Maria decided not to replace Lili. Since then, Tiger has been the happiest cat ever. His disease has been in remission for years, and he does not seem to miss having a companion. Although Maria would love to get one of the kittens she sees all the time on adoption websites, she understands it is best for Tiger to be her only feline companion.

If you have cats in your home, chances are you have more than one. Most cat owners do. But how do cats feel about that? As humans, we know that living with someone can be difficult. Sharing space, sharing your things, not having silence and solitude when you want it—it doesn’t always work out with roommates. It’s not very different for cats. Some cats willingly live with other cats, but many cats seriously resent the company or take quite a long time to adapt, and then only if behavior modification is part of the introduction process.

In chapter 4, you read about the social behavior of domestic cats. In this chapter, I will explain how feline social behavior regulates interactions in a multicat household, and how you can make it work if you decide to add a new kitty to your family. I will discuss realistic expectations, basic guidelines to increase the chances of peaceful feline coexistence in a multicat household, how to fulfill every cat’s needs, and how to introduce a new cat so the situation is less stressful for everyone (humans included!).

Do cats enjoy the company of other cats? Mixed messages abound: Cats are not social. Cats are not as social as dogs. Cats are highly social. What is really true?

If cats are social, why can it be so hard to introduce a new cat to a household? Why do so many cats never get used to having a companion of the same species? The answers are in the evolution and biology of their behavior.

The ancestor of all domestic cats, Felis silvestris lybica, or the African wildcat, was a solitary animal. But through centuries of domestication, this wildcat developed into Felis catus, the domestic cat, with the amazing ability to be social. This makes our cats (along with lions and cheetahs) part of a very select group of feline species that exhibit social behaviors and form groups. They are capable of complex and fascinating cooperative behaviors, such as taking care of and nursing one another’s young.

Free-roaming cats often form matriarchal groups of related female cats. They rely on chemical communication in their environment to establish a group identity, often using scent before sight to verify individuals. Strangers are most definitely not welcome in these groups. Males tend to leave the group around one year of age, and the resident cats will aggressively chase away strangers if they come too close.

When we decide to share our lives with more than one cat, we force unrelated cats into an artificial social group. For many cats, this can be difficult and even unacceptable. While cats can show affiliative (friendly) behaviors to other cats, their evolutionary history (eons of solitude) means they lack the conflict-defusing behaviors that other animals, such as dogs, have mastered. So if they have an uncomfortable encounter, they typically default to avoidance and dispersal—that is, they run away. When cats live indoors in a house ruled by humans, however, they cannot just leave and find another place to live. That is why introducing your cats to one another the right way (stay tuned) is so important. First impressions are everything; you want to avoid that initial squabble at all costs.

Feline social preferences are also influenced by personality, genetics, prenatal and postnatal brain development, early life events, and adult life experiences. Every cat is unique, and when integrating cats into a harmonious home, you must consider this individuality.

On the bright side, cats have developed several amazing ways to coexist without conflict—if the environment they’re living in affords each cat her own space, resources, and coping mechanisms. We now understand what enables some cats to live together with minimal stress and in many cases to truly bond and become friends.

In a multicat home, some cats will form their own groups, while some might behave as solitary cats. This is totally acceptable. The key, as I will explain later in this chapter, is to provide separate and multiple resources to support each group and each cat.

Ancestor: An early type of animal from which others have evolved.

Affiliative behaviors: Social behaviors meant to communicate affection, reduce tension, and maintain a bond.

Antagonistic behaviors: Social behaviors related to aggression, fighting, or an altercation. These can include stress or fear signaling, threatening behaviors, retreat or avoidance behaviors, and attacking.

Anxiety disorders: A group of mental disorders or behavior pathologies characterized by significant feelings of anxiety and fear that interfere with the ability of an individual to live a normal life.

Anxiety: A state of worry or unease about something that may happen or an outcome that is uncertain.

Appeasement and reconciliation behaviors: Behaviors meant to make peace, de-escalate a situation, or avoid a fight. Although cats show some of these behaviors, they have a less extensive repertoire than dogs due to their evolutionary history of using physical avoidance and scent to avoid conflict.

Behavior therapy or behavior modification: The systematic use of learning procedures to treat psychological problems and modify dysfunctional behaviors.

Fear: The emotion of being scared or afraid of some situation, animal, person, or event.

Pheromones: Naturally occurring species-specific scents that cats use to delineate territory or calm nursing kittens. Synthetic analogues (copies) are available commercially.

Stress: The biological response triggered when a stimulus, called a stressor, challenges the peaceful balance of an individual’s body or mind. Stressors can be external (coming from the physical environment or from social interactions) or internal (illness, pain, discomfort). Stress can initiate the fight-or-flight response, a complex reaction of the nervous and endocrine systems that affects the whole body.

Let’s review the signs of stress and of friendly interactions discussed in earlier chapters. What are those signs? How do you know when your cat is happy to meet another cat and when she’s not? Here’s a quick body language dictionary, looking specifically at the signals that are most important in a multicat household.

Affiliative or friendly behaviors. For cats, greeting with the tail relaxed and up straight is a common signal of a friendly approach. The gaze is soft, and some cats slowly blink. Rubbing and grooming one another, playing, resting in close proximity, and snuggling together are other examples of these behaviors.

Threatening behaviors. Freezing and staring, sometimes with hissing and growling, are common feline threats.

Retreat or avoidance behaviors. These include breaking eye contact, backing up, walking or running away, and hiding.

Attacking. This can be swatting, biting, or clawing.

Stress. Cats can present stress signs using facial expressions, body movements, and behaviors. Common facial signs are tension in the facial muscles, typically accompanied by ear movements such as flicking them, fixing them forward while staring at something, or rotating them toward the back of the head. (Ears rotated backward and flattened is a sign of extreme fear.) Other signs of stress that can be easily noticed on a cat’s face are rapid blinking or squinting (which is usually accompanied by a head turn as the cat breaks eye contact), dilated pupils, and lip licking and gulping. Movements of the tail are also meaningful. Some cats will tuck their tail close to their body, and some will flick it as a sign of increasing agitation.

Some stressed cats might exhibit behaviors that seem out of context, such as quickly grooming. Cats also show tension in the muscles of the body, often followed by behaviors such as flinching, lowering the body close to the floor (crouching), or arching their back. Their fur might be raised or fluffed up, and their head might be low.

Many stressed cats are hypervigilant, constantly scanning the environment and reacting to movement and noises they detect, while others act sedate and simply freeze and look catatonic. These behavior changes can be accompanied by active attempts to avoid whomever the cat is interacting with (or any scary stimulus), such as moving backward, walking away, running away, hiding, jumping, or climbing up to a high spot. Some cats might not move until they are touched or the scary individual gets too close.

Nervous cats will often vocalize, which can vary depending on a cat’s socialization history and arousal levels. Some cats produce a high-pitched meow, some hiss and growl, and some might even scream or spit.

When stressed cats feel cornered or pushed into a situation, they may show aggressive behavior. Or they may alternate their stress signaling with freezing and staring, then attacking (biting and clawing). Some cats might actively chase and attack as well.

How worried should you be if your cats are showing signs of stress due to living together? Does stress actually cause disease? The answer is yes, it really does. When a cat perceives a potential threat or challenge, her body responds, activating the stress mechanisms that may also lead to anxiety and fear. Cats experiencing acute stress show a specific body language that may help you detect when your cat needs help (see the previous section, “What Does It Look Like?”).

Even though the brief stress response is an important defense mechanism for all species, living under chronic stress is detrimental to a cat’s mental, emotional, and physical well-being. Chronic stress can cause medical and behavior problems, such as anxiety disorders, aggressive behavior, and house soiling.

For example, stressed cats can develop an inflammatory condition in which urination becomes painful, their urine may contain blood, and they may start urinating outside the litter box. Eliminating outside the box is not a complaint or a protest against anything, but rather an attempt to eliminate somewhere that feels safe and comfortable. (See chapter 8 to learn more about this topic, other reasons cats might eliminate outside the litter box, and what to do about it.)

Imagine you just got home from a long day at work. You cannot wait to pour yourself a glass of wine and relax, maybe even binge-watch your favorite TV show. Suddenly, someone knocks on your front door. You open the door and a stranger walks in, picks up your glass of wine, sits on your couch, and changes the channel. What would you do? Probably call 911.

Cats can’t do that. But we bring strange cats into our home and let them make themselves comfortable. How terrifying this must be for the resident cats!

Planning ahead for a multicat household is an investment in your cats’ health and relationships. Using science-based methods when introducing a new cat, rather than just letting the cats “work it out,” will make things go a lot smoother and prevent serious problems down the road.

The first impressions cats have when they meet has a long-lasting effect, and cats who fight at their first meeting are less likely to get along. A 2005 study conducted by Dr. Emily Levine, DACVB, and her colleagues at Cornell University Hospital for Animals found that the factor most frequently associated with fighting in the weeks immediately following the introduction of a new cat into a household is unfriendly or aggressive behavior at the first meeting. In other words, first meetings described as unfriendly or aggressive by the owners in the study were significantly more likely to be associated with fighting in the following weeks than first meetings described as friendly or nonaggressive.

That’s why a successful introduction of a new cat requires careful planning and proceeds slowly, never pushing either the new cat or the resident cats beyond their threshold and into fight-or-flight mode. It’s a gradual process, and what that means is different for every cat. For some cats it may take only a few weeks, while for others it may take months.

Before you bring home a new cat, prepare a room for her. The room should have a door that shuts it off from the rest of the house and contains everything the cat needs: food, water, litter box, toys, scratching post, hiding spot, and elevated resting area.

Bring your newly adopted cat directly into her prepared room, keeping her apart from your resident cats. Do not stop to let them interact with her—not even a sniff. Being placed in a new environment with new sights, sounds, and smells is scary! A separate space will allow the new cat to get comfortable and relaxed in her new home and give the resident cats time to take in what is going on. Do not allow your resident cats and the new cat to see or touch each other at this stage.

The cats will likely react to each other through the closed door, so make sure they are truly separated. You can, for example, use a draft stopper or box to prevent the cats from seeing each other under the door. When all signs of stress, fear, and anxiety have ceased in all the cats (see “What Does It Look Like?” earlier in this chapter), you can progress to the next stage.

At this point, your new cat and resident cats are probably ready to be introduced to each other’s scents. Cats are guided by smell and chemical communication, so scent is more important than sight. Before we get started, though, a word of caution: Artificial scents on their body are not well tolerated by cats, not even if all the cats carry the same artificial scent. Do not put perfume or any other scent on your cats! That’s really stressful for them. They will naturally and gradually create a group scent based on their own odors, not ones added by you.

You can start by exposing each cat to minor items used by another cat—for example, by swapping blankets or small toys. To maintain their sense of security, make sure you do not place these items in the cats’ safe places, such as beds or cat trees.

Give the cats time to familiarize themselves with the new scents. Always present these items paired with a high-value treat. You’ll want to use a treat or food that is very enticing to the cats in order to promote the most positive association possible, so take time to identify which treats are most rewarding for each cat. Remember, different cats have different tastes.

When you observe that none of the cats are showing signs of stress when presented with the other cats’ scent items, you can start a time-sharing experiment in the common areas of the home—the rooms that are not any cat’s respective safe haven—to further expose them to each other’s scents. Do not introduce more than one cat’s scent at a time to the new cat, as this can be really overwhelming for her.

Begin by allowing each cat into the common areas for a few minutes every day, then progress to longer periods. Remember to always give small, high-value treats to the cats as you practice this step. Progress to the next step when there are no signs of stress, fear, or anxiety.

If possible, allow your cats to see each other without the opportunity for physical contact. Glass or screen doors or baby gates with transparent acrylic panels affixed to them can make this step as safe as possible. A hook-and-eye latch that allows the door to be open just a crack may be a suitable alternative to a glass or screen door. Pair these introductions with high-value treats or play to keep the cats focused on you, while striving to create a positive association between them. Only if all the cats are calm and friendly should they be allowed to shift their attention to each other.

Do not overwhelm or push your cats. A couple of five- to ten-minute sessions twice a day is more than enough to begin with. Do not let them focus their attention on each other unless they are both calm, and make sure they have some distance from each other to begin with, even with the barriers separating them. If they start staring at each other or showing any other signs of stress, call one of the cats to you (it is very useful to teach cats a verbal recall cue to help manage them without having to touch them) or, if it can be done safely, pick one up or cover her with a thick blanket or towel to block her vision.

When none of the cats show any signs of stress, fear, or aggression when they see each through a barrier and happily approach the barrier in spite of another cat being on the other side, you can move to the next step.

Start feeding the cats at the same time, without a physical barrier between them but at a distance—as far apart as it takes for them to remain calm. You can use high-value small treats or high-value food that can be eaten quickly instead of their regular meals.

It’s better and safer if you have one or more people to help you, so that each person is paying attention to the body language of one cat. Reinforce calm and friendly behaviors by rewarding the cats with high-value treats and praise, and redirect any stress signs or antagonistic behaviors (such as staring) by happily calling the cat’s name and focusing her attention back to the food or to you.

If you notice that one of the cats is becoming fearful, anxious, or aroused, remove her from the situation or cover her with a large blanket, then try again the next day.

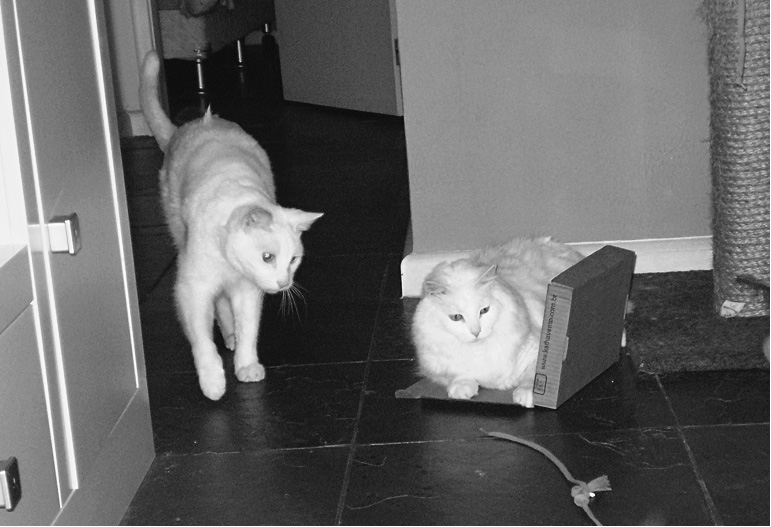

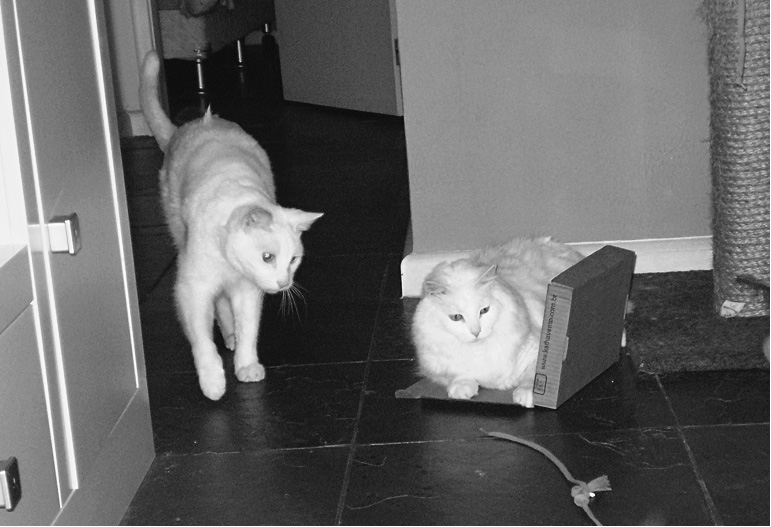

Eliciting play is an effective way to promote positive interactions between cats.

Leticia Mattos De Souza Dantas

When the cats are consistently meeting with success in the previous step (all of them are calm and not aroused or stressed in each other’s presence, and they are able to hang out without focusing on each other), try playing with them while they are all together in the same room. Food-dispensing toys are great at this stage, because they can help the cats show social and play behavior without focusing too much on each other—all the while making the positive association you want between food and the other cats. Games where cats search for food can serve the same purpose.

Another type of activity that can promote a great experience while not allowing the cats to focus on each other is teaching them a new task or trick that they can do when asked. For example, you can ask the cats, one at a time, to touch an object or your hand with their nose, then reward them with a treat. (This is a form of operant conditioning. See chapter 6 to learn more about how amazing cats are at learning and how fantastic it is for their mental health.)

If this phase goes well, start allowing the cats to be in each other’s presence without so much guidance and control from you, but still with supervision. Allow short interactions, ending while everyone is still calm, and gradually increase the time together if all the cats remain relaxed and stress-free.

If you are afraid that an altercation may suddenly arise and escalate, consider keeping each cat on a harness attached to a long, loose leash. Do not put any tension on the leash at any time during the positive interactions; use it only to separate the cats should a fight occur.

These cats huddle around a food-dispensing toy (not pictured), focusing on the toy and not on one another.

Leticia Mattos De Souza Dantas

Unsupervised interactions (and eventually, being allowed to live together freely) should come only after several weeks or months of no stress signs and no antagonistic behavior from any cat. Whenever your cats show any friendly behaviors toward each other (approaching with tail up, gazing with soft eyes as opposed to staring, purring, nose touching, head or body rubbing, grooming each other, attempting to play), give them lots of praise and a high-value treat immediately—this is gold!

You might experience a setback at some point, but do not despair. Behavior is dynamic and ever-changing. This means everyone—your cats included—can have bad days from time to time. Just take a deep breath, go back to the previous step, and pick up from the stage at which no cats showed any signs of stress.

Now that you know what to do, let’s examine the things you need to avoid.

Never bring a new cat in and let her loose to explore the house while the resident cats are free to roam as well.

Don’t plop down the new cat in her carrier and let the resident cats surround her. This “shark tank” method will cause the poor newcomer to be trapped in a box while being menaced by strangers. Meanwhile, the other cats will be freaking out over the intruder in their house. This is a lose-lose situation and no way to do an introduction.

Don’t reprimand or correct any negative responses from any of the cats, because this is likely to add tension to the situation. Hissing, growling, and swatting are behaviors that come from stress and fear, and your cats have the right to express those feelings. For the same reason, forget spray bottles, making loud noises, yelling, throwing things, and so on. All these punishments will only hurt the bond the cats have with you and will certainly not teach them to love each other. You must do this the right way and the respectful way, to ensure that things turn out for the best.

The most common pitfall when introducing cats is rushing the process. Trust the method you have learned in this book and take your time with it! Remember, your cats’ behavior is your guide for when to move on to the next step. They need time to adapt, and how they feel is all that matters.

Cats commonly do not express stress, fear, and anxiety with signs that are obvious to us humans. Instead, they have evolved to show avoidance behaviors (hiding) and scent marking (urine spraying or increased scratching) when they are stressed or frightened, to signal to other cats how they feel. Some cats are more active about how they show their emotions, and others are more passive. Signs of heightened fear and aggression (such as hissing, growling, charging, swatting, pawing, and biting) definitely mean that a cat is severely stressed. However, some cats who are stressed do not show these signs. Often cats simply freeze in fear and do not move, or they move very slowly. In other words, the absence of obvious aggressive behavior does not mean that your cats are okay.

If you notice any of what veterinarians call sickness behaviors (decreased grooming, decreased appetite, a change in sleep patterns, increased vocalizations, missing the litter box), these may be signs that a cat is nervous or stressed about what is happening. Do not proceed with the introduction, and keep the cats separated until they are all calm.

Other signs that a cat is stressed include a decrease in playfulness, avoiding social interactions (with both humans and cats), frequent hiding, or a tendency to remain on the periphery of the room. Paying attention to these changes is very important, especially for cats who have a more stoic or passive temperament. A change in attention-seeking behaviors (usually seeking more attention or acting needy for active cats, and fewer social interactions for more passive kitties) is another important clue that a cat is stressed. (See chapter 1 to learn more about cat communication, body language, and signs of illness.)

In 2013, the American Association of Feline Practitioners and the International Society of Feline Medicine published a terrific booklet, AAFP and ISFM Feline Environmental Needs Guidelines (https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/1098612X13477537). Several distinguished veterinarians, including veterinary behaviorists, got together and organized years of research into a comprehensive and objective document that outlines what cats need to have an excellent quality of life. Check out the AAFP website (www.catvets.com) for other important guidelines and handouts for cat owners.

Long before these environmental needs guidelines were published, decades of studies had shown how enriching an animal’s environment can significantly benefit her health in several ways. Some of these studies (including ones I was involved in) were conducted in shelters or laboratories where cats were kept, with the goal of improving their quality of life and decreasing their stress levels. Other studies and review papers focused on house cats and how to optimize their well-being, including a 2012 study by Dr. Meghan Herron, DACVB, and Dr. C. A. Tony Buffington. And still others explored using enrichment to treat feline interstitial cystitis (FIC), a common feline pathology for which stress is a major risk factor and trigger. (See chapter 8 to learn more about this problem.)

When it comes to multicat households, some of the enrichment strategies described in the environmental needs guidelines can give cats coping mechanisms to deal with the stress of group living. Here’s what you need to know about how to set up your home environment for multicat success.

Cats should have multiple and separate resources. When your cats have the option not to share their most important resources, they have more control over the things that are important to them, and this decreases the likelihood of conflict.

Key resources are food and water stations, litter boxes, scratching surfaces, toys, play areas, elevated resting areas, and safe spots. It is very important that these resources are provided in multiple locations throughout your home, as opposed to crammed into one area or even one room. This is a common problem with litter boxes. If they are all in one area of the house, for cats this counts as just one elimination location. If a cat is afraid others will block her access to the box or ambush her when she’s in it, she may avoid the area and eliminate in what she considers a safer place.

Avoid feeding the cats in a situation where they must be close together. When a cat is trying to get her meal, it can be stressful to eat side by side with other cats or have to fight for access to one large bowl. Eating should be a safe and peaceful process, or anxiety levels may go up. (Small treats that can be quickly consumed are used in training and introductions. At those times the space between cats is carefully controlled. We’re talking here about their regular meals.)

Carriers can be great safe places for your cat, but you need to have one for each cat. Leaving each cat’s carrier accessible all the time has the added bonus that it can make the trip to the veterinarian less stressful for your cat, because she sees the carrier as a safe haven.

Leticia Mattos De Souza Dantas

Even adult and senior cats need to play! Play is important for their mental and physical well-being, and it is an indicator that all is well with a cat. Cats may play by themselves, with each other, or with their human family members. Some cats are enthusiastic and will play with anything and anyone. Others are more particular, preferring certain types of toys and styles of play. Some prefer one-on-one playtime with their owners and are not really into social play or sharing toys with other cats. If you have a cat who behaves this way, play with her in a separate area apart from your other cats.

Have fun experimenting with your cats, so you get to know their preferences. Toys can be as simple as a wadded-up paper ball or as sophisticated as a battery-operated toy that triggers hunting behavior. Our household cats may be domesticated, but they still retain some wild tendencies. Many cats have a strong preference for toys that spark parts of the predatory sequence: stalking, chasing, pouncing, grabbing, clawing, and biting. If cats are not given the opportunity to display these predatory behaviors through play, they may develop inappropriate behaviors (chasing, pouncing, biting) directed at their housemates, which would not be conducive to peaceful coexistence!

Games where cats are encouraged to search for food or toys keep them busy while helping them have a good time together.

Leticia Mattos De Souza Dantas

Having a predictable routine gives cats an additional sense of control and reduces their stress levels. Make changes slowly and gradually. Knowing what to expect and how their lives will unfold every day (from feeding to playtime) can significantly decrease cats’ stress and anxiety, and help our feline companions understand how to distribute their time and space to coexist peacefully. For example, if there are conflicts between two cats living together, they may decide to be more active at different times of the day and in different areas of the house.

Often our cats are more attached to us than to their feline companions. This is more important than most people realize. One study published in 2017 by Dr. Monique Udell, Dr. Lindsay Mehrkam, and Dr. Kristyn Vitale Shreve showed that most of the cats they studied actually preferred human interactions to food, toys, and the scent of food.

Offer your cats predictable times when they can get one-on-one attention and affection. Make this time special for both of you by exploring your cat’s favorite activities. This is especially important if your cats are separated during an introduction period and need to be moved from room to room in the house—which means each one will get less time with you.

It is generally accepted that cats are safer and will live longer if they’re kept indoors. However, it is obvious that even the most amazingly designed indoor living space cannot mimic the excitement and stimulation of being outdoors. An acceptable compromise (when space and budget allow) is to net or completely fence in an outside area for your cats. The additional space and stimulation can greatly increase cats’ welfare and help with their cohabitation by offering more exciting enrichment, more opportunities for normal behavior, and more spacing—all of which will help prevent and defuse conflict. (See chapter 3 for more information on environmental enrichment and fulfilling feline needs.)

This is a great, safe outdoor haven for a cat.

Leticia Mattos De Souza Dantas

What about when one cat leaves the house and then returns? Her buddies may act as if they don’t know her, even if they have been living together for years. What’s happening here?

Scientists believe that through all their marking and rubbing behaviors, cats create a group scent. They may lose this scent after extended boarding or hospital stays and return home smelling like a stranger to the other resident cats. In fact, some resident cats can get nervous and even become aggressive toward a cat who has been gone for less than a day at a veterinary appointment.

The cat coming home is also likely to be returning stressed and upset. Take an active approach and put her in a room by herself for a short time, so that she can calm down and groom off the foreign scent.

If the other cats still act as if they don’t know her, the introduction protocol outlined earlier in this chapter will come in handy. Take the returning cat to a separate area of the house and give her separate resources and time to calm down. Give the cats who stayed behind time to reacclimate to her smell and sounds. Go through all the steps in the introduction protocol, but often a reintroduction is much quicker than an initial introduction.

You might have cats who have gotten along well for months or even years, then suddenly show signs of conflict. This situation can sometimes be triggered by a frightening external event that made one of the cats nervous and reactive, such as a shelf falling off the wall or a stray cat or wild animal coming up to the window. Some cats also develop fear and anxiety as they age and have scary life experiences.

Once the primary cause of the stress that triggered the conflict has been removed, you can address the problem exactly as you do when you introduce a new cat to the home. Separate your cats, give them time to calm down, and then gradually start the protocol of exchanging scents and reintroducing them to each other, using lots of high-value treats and praise.

When stress spikes or becomes chronic, some kitties might benefit from medication that can decrease their arousal levels and support better functioning of the brain areas that regulate fear and anxiety. This is not a decision to be taken lightly. Talk to your cat’s primary care veterinarian and perhaps discuss a referral to a behavior specialist. Knowledge is empowering, and the veterinarian will be able to give you all the information you need to decide how best to help your cat.

You have probably noticed that there are several commercially available products that promise to decrease your cat’s stress levels and even help with specific problems, such as getting cats to coexist without conflict. These include synthetic pheromones, herbal supplements, homeopathic remedies, essential oils, nutritional supplements, and many more.

Beware of guarantees or promises of quick fixes. The truth is that these products are not FDA approved, most of them have had little or no research to test their efficacy, and often the active ingredients and chemical structures are unknown or not revealed. While some pheromone analogue products and nutritional supplements have been shown to help decrease stress, no homeopathic remedy or essential oil has.

Feliway Classic is a synthetic version of the feline facial pheromone that cats deposit in the environment when they rub with their faces on objects, and Feliway MultiCat is a synthetic version of the maternal appeasing pheromone that queens produce when nursing their kittens. They come in both a spray and a plug-in diffuser. These products claim to produce a sense of safety to help cats remain calm. In a 2014 clinical trial of forty-five families who reported social conflict among housemate cats, Dr. Theresa DePorter, DACVB, found that using a Feliway MultiCat plug-in diffuser reduced the level of conflict compared with using a placebo. Although there are a number of other products available that may list pheromones in their ingredients, the Feliway products are the only ones with scientific research behind them and are, at the moment, the only ones available in a spray or a diffuser.

There is some evidence that the amino acid L-theanine (Anxitane) and the milk protein alpha-casozepine (Zylkene) can be used to treat anxiety in dogs and cats, including research by Dr. Gary Landsberg, DACVB, but large, controlled studies on cats are lacking.

Ask your veterinarian before medicating your cat with anything, no matter how “natural” it is. And remember, even the products with some science behind them are not meant to be used as a substitute for appropriate management and behavior therapy strategies that can make your cat truly feel safe.

Catnip can be one of those special treats you use to create a positive association when cats are being introduced. Typically, cats become relaxed and exhibit play behavior when exposed to it, and that’s just what you want.

You can grow catnip and give your cats fresh leaves, or buy dried leaves or toys that are stuffed with them. Not every cat responds to catnip, though—only 50 to 60 percent of cats respond behaviorally. Their response has a genetic basis. In other words, do not feel offended if you spend money on a catnip toy and one of your cats totally ignores it.

Some cats who have a behavioral response to catnip get aroused and cross to the dark side. Their eyes get big (they look this way because their pupils are dilated), and they might act tense, vocalize (in a way that sounds more alarming than fun), and twitch their backs. Some will swat at or bite whoever comes close.

If that is your cat’s reaction, do not bring catnip into your home. When cats get aroused, they can redirect their aggression to the nearest target. You don’t want to put anyone—human or feline—at risk. The relationship between your cats also can be seriously damaged if there is an aggressive incident. At the end of the day, cats who have this type of extreme response should not be exposed to catnip.

As with some humans, some cats just can’t get along, despite our best intentions and even if we do all the right things. Remember Tiger and Lili? Their socialization to other cats might have been deficient, or they might simply have not been able to handle the stress of being around an unfamiliar cat. Even cats who peacefully shared part of their life with another cat in the past may find it very difficult living with a new cat.

In theory, cats who cannot get along can live in separate areas of your home, as long as you provide each with all their key environmental needs. Some cats will adapt to living this way with low stress levels. Sadly, others will remain severely stressed, resulting in a poor quality of life and decreased longevity.

If your cats are not adapting, even after you have diligently tried the introduction process described in this chapter and given it plenty of time, consult with a veterinary behaviorist or a certified behavior consultant. A specialist can help you figure out if the cat who cannot adapt could benefit from a medication that treats fear and anxiety, or if one of your kitties would be much happier in a different home.

Having cats who need to be separated for the rest of their lives (especially if they show aggressive behavior) can also take a toll on the humans in your home. You need to consider what is best for your family’s well-being. But before you give up on your cats, we strongly encourage you to give them another chance by consulting with a veterinary behaviorist.

As you have already learned, being related increases the likelihood of cats getting along. Research also has shown that early socialization to each other greatly increases the chances of feline bonding. So, when you think of adopting again, consider taking home a mother cat with one or more of her litter, siblings, or pairs or trios of unrelated kittens.

But the most important consideration is, does your resident cat, or an older cat you’re thinking of adopting, want a companion? Certain cats with certain personalities prefer to be alone, and you need to give careful thought to how your decision will affect them.

When your resident cat cannot adapt to living with a feline companion, her well-being should be your priority. It may be best not to adopt another cat. Likewise, if you had a long and difficult introduction between two cats but things are finally going well, you don’t want to upset the harmony you have finally created by adding a third. This might be disappointing, but living under chronic stress and anxiety can be devastating for your cat (and your family). In the end, every cat deserves a peaceful, stress-free life.

Cats form matrilineal social groups in a free-roaming situation, but they typically do not allow unfamiliar adult cats into their group.

Cats lack the conflict-defusing abilities that dogs possess, and they quickly default to avoiding each other and dispersing after an altercation. It is important not only to introduce newly adopted cats slowly and carefully but also to prevent conflict between cats who get along.

Stress is a serious health concern for cats. Kitties really need places to hide, feel safe, and calm down.

Cats might coexist without conflict if the environment supports giving everyone her own space, resources, and coping mechanisms. Instead of being forced to share, cats should have multiple, and separate, environmental resources spread throughout the space they occupy.

When introducing cats, take your time and use the step-by-step plan in this chapter. Don’t rush introductions. Your cats’ behavioral responses are your best barometer for knowing how and when to proceed.

Don’t use punishment-based techniques or devices, which will only raise the stress level and promote conflict.

If, despite your best efforts, one of your cats is not adapting, discuss it with your cat’s primary care veterinarian or seek the help of a veterinary behaviorist or certified behavior consultant. Medical treatment for fear and anxiety might be warranted.

Some cats just prefer to be solitary, either by themselves in a separate area of the house or simply living with no other cats in the house at all.

When adopting cats, consider taking home a mother with one or more of her litter, siblings, or two or three unrelated kittens. Being related or being introduced at a young age will greatly increase the chances of cats bonding and living together in peace.