CHAPTER SIX

Rise of the Barrackers and Hissers

Saturday afternoon was normally the time for football, but that afternoon was a holiday for only a few professions and even fewer skilled trades in the 1860s. Even for city clerks in favoured positions, the Saturday afternoon was not always free, and in the period before the overseas telegraph cable reached Australia the impending departure of a mail steamer for England signalled a Saturday of lastminute writing of letters and commercial orders from banks, merchant houses, big shops and factories. We know that on the Saturday of the punishing match in which Harrison was deemed the villain in July 1870, the Albert Park team was seriously weakened by the absence of some to its finest players ‘in consequence of the departure of the mail’. Though that phrase means nothing to us today, it meant everything to a city which was still commercially tied to England. Even football had to give way to the mail steamers.

The 1870s were to see a large increase in the number of workers who were free to play football on a Saturday afternoon, but in the preceding decade such workers were few. In Melbourne was one notable exception – the soldiers living in the barracks that still stand on 82 St Kilda Road. Ever since 1788, regiments of soldiers recruited in the British Isles had been stationed in Australia; and during their term of duty they often took part in local social and sporting events. The regiments now stationed in Melbourne had just returned from the wars against the Maoris in New Zealand, and being attracted to competitive sport they began to take intense interest in the football matches played within ten or fifteen minutes’ walk of their bluestone barracks. The teams in Melbourne were also eager to play football against the soldiers, for here was the first opportunity to play what could be seen as an international game of football: Victoria versus the British Isles.

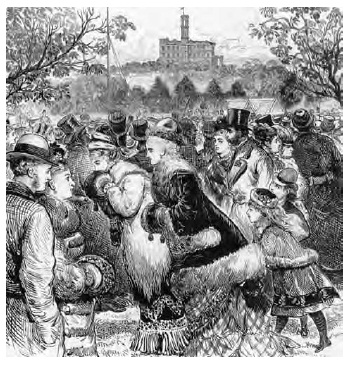

Even in wet weather, large crowds went to the football (The Australasian Sketcher, 3 July 1880).

Regular contests against the soldiers began in 1867. The difficulty was that the officers and privates did not understand what were called the Victorian rules. Even if they did understand them, they preferred to play according to their own rules which favoured their physical strength. They liked to grab the ball and run, charging and shouldering their way through opponents.

The soldiers were to be long remembered for their liberties with the rules. The 14th ‘Buckinghamshire’ Regiment team was led 83 by Lieutenant A W Noyes, himself a Rugby player and a clever handler of the ball; and his team’s exploits – no doubt exaggerated – were recalled in a verse which appeared in 1877 in The Footballer magazine:

I’ve watched the 14th at football play,

In foraging caps and singlets grey;

Lieutenant Noyes,

With his broths of boys,

Charged fierce along with a wild ‘Hurrah!’

’Twas ‘Go it, Larry: fetch him a lick!’ *

Then Larry licked

And Dooley kicked;

The long verse went on to lament that players in the 14th Regiment thought that fair play embraced hacking and tripping, while their fierce charges could end in a ‘nose all smashed, and some teeth knocked out’. But one picture that lingers is of the shouting and barracking by the private soldiers:

Pat Kelly cries, with a warlike snort;

‘Knock ’em to blazes; bark their shins,

And I’ll stake my life the 14th wins.’

They did not often win against top Victorian clubs but in defeat they were exultant.

Games against a red-coat regiment provided a unique brand of football. On 17 July 1869, Albert Park played the 14th Regiment in a ground at the end of Clarendon Street, obviously the site later of the South Melbourne ground, and about a thousand people arrived 84 to receive ‘an infinity of amusement’ from the rough and tumble play of both teams. It seems that several of the soldiers favoured a more soccer-type game and they secured the winning goal by dribbling the ball into the forward-line where at last a strong kick guided the ball through the posts. Curiously, the Albert Park goalkeeper was no more familiar than the soldiers with the rules and tactics, and instead of stopping the ball in front of the goalposts he marked the ball after it had passed through. This match suddenly came to an end in the second half after a field umpire’s decision had been fiercely disputed.

Harrison, captaining Melbourne in its first match against the Garrison, wisely allowed the soldiers some latitude. (They probably thought they gave him the same privilege.) In later matches Harrison called for stricter adherence to the rules agreed upon, and the Garrison probably said yes, but what the ‘yes’ meant was open to doubt. Their mode of play was described as ‘hugging and hitting’. With their sturdy physique, a willingness to use heavy soldiers’ boots to kick an opponent in the shins, and coloured handkerchiefs tied around their brow in the manner of modern Aboriginal nationalists, they appeared ‘pretty awe-inspiring’, noted Harrison. He especially relished the soldiers’ way of forming a bodyguard to protect their captain when he fell panting to the ground, the ball beneath him.

Matches with the soldiers aroused intense interest. They were considered so important that in 1869 the Melbourne Cricket Ground was allocated for one match in which Melbourne eventually defeated the Garrison by one goal to nil. Such matches heightened the discussion about the emerging rules of Australian football, and the general conclusion was that the local rules were far superior to the soldiers’ rules. Impertinently, some observers even said that the soldiers had no rules.

Harrison was especially delighted with one rough incident in June 1868. The soldiers, after they had been defeated by a Victorian 85 team, replied that all would be changed soon: ‘Wait till Ensign Crosby arrived!’ At last he arrived. Appearing on the football ground in spotless white and wearing a belt which was probably embroidered by an admiring woman, he seemed boyish and lacking in robustness. He was in all likelihood a sprinter with an uncanny ability to dodge. He was given no chance to dodge. After about sixteen seconds Ensign Crosby was charged (‘collided with’ was Harrison’s tactful phrase) by a stocky Melbourne footballer named Chubby Forrester. The frail Ensign, all in white, was carried from the field.

Women wearing the latest winter fashions would stream into Yarra Park if their favourite team was playing. This sketch of a hurrying crowd in July 1877 shows, on the other side of the river, the grand, new government house (The Australasian Sketcher, 7 July 1877).

Many soldiers went as individual spectators to football matches, particularly those played near the Albert Park lagoon, which was not far from their barracks. When Albert Park played Carlton for the Challenge Cup in August 1870 and the ‘great assemblage of spectators’ crowded along the boundary of the unfenced arena, the captains of the two teams invited a few soldiers of the 18th Regiment 86 to prevent the crowd from invading the field. The brave soldiers succeeded. That must have been one of their regiment’s boldest victories on Australian soil.

All the British regiments in Australia were to leave in 1870, permanently handing over the land defences to the local troops of each colony. In the history of empires it must be rare for the imperial power to withdraw its forces in such a glow of goodwill. In Melbourne their departure was regretted by most followers of football, not only because the two styles of play made matches against the soldiers so unpredictable, but also because these contests were the closest approach that Australian football could make to international matches in its first two decades. For that reason Saturday, 6 August 1870 was especially awaited. Almost on the eve of the 18th Regiment’s departure by sea, its officers and privates were to play Carlton, the team with the largest following of all. Rain poured, and the match was called off. Many sports-goers were sad to see the soldiers finally march through the streets on their way to the pier.

They left behind something permanent. They helped to shape a word which has been one of the hallmarks of Australian sport for more than a century, the word ‘barracker’. The word became popular about 1880 and was originally an Australian football term, and from football it spread to cricket and then to every kind of sporting contest. For a long time it was a slang word, but it climbed the social and political ladders; and on 5 July 1893 in the Victorian Legislative Assembly, Isaac Isaacs, who was to become the first Australian-born Governor General, could be heard complaining in the face of frequent interjectors that he hoped that their barracking ‘would not be continued’.

Apparently the word was still unfamiliar in England, and authors writing for the English market felt a need to explain what it meant. G L James, in his book of 1892, Shall I Try Australia?, explained that in Victoria the young men were mad about football, usually 87 wore the colours of their team and were known as barrackers. He explained that ‘to barrack’ was to ‘audibly encourage their own favourites and comment disparagingly upon the performance of their opponents, a proceeding which leads to an interchange of compliments’ between the rival barrackers.

The word was said by some to come from the Aboriginal borak and by others to come from the Northern Irish word barrack, meaning to brag and boast of one’s fighting powers. It is unlikely to have stemmed from the Aboriginal, and even an Irish origin is not certain since the little-used Irish word did not mean the same as the new Australian word, though their meanings are similar. More important than the exact origin of the word is the question of why it came to be used enthusiastically in Melbourne’s footballing circles – being used infinitely more than in Ireland and used in a different way – and why it then spread throughout the continent. A new word becomes the vogue largely because it sounds right. The word barrack seemed just right amongst football spectators in Melbourne in the 1870s because they recalled the regimental footballers who lived in the Victoria Barracks, knew especially their fighting brand of football, and recalled how Pat Kelly and Tim Dooley and other soldiers, mythical or real, barracked while playing or watching. In a city and a sport where the players from the army barracks made such a stir, the word seemed a neat fit. Where the word actually originated is an important matter for those who trace the ancestry of words, but more significant is why it was virtually reborn in Melbourne, and why it there acquired an energetic life of its own and a distinctive meaning.

At one time many people in Melbourne believed that the word had originated through football’s connection with the Victoria Barracks. But the specialists in the Australian language who later emerged – and most came from New Zealand – did not realise the intimate connection between ‘barracks’ and the rise of Australian 88 football and therefore had no reason to see merit in the theory. It is now impossible to tell whether the word was invented in Melbourne or imported from Ireland and then resuscitated with a new meaning; but it would not have become so popular but for the fact that in Melbourne it conjured memories of a special group of footballers and their banter on and off the field. Eventually the word in its new meaning was to cross the world, becoming common in English sporting writing from about the 1920s.

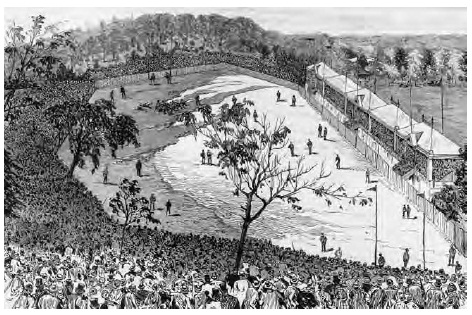

Sydney was much slower than Melbourne to adopt football as a winter game, but by June 1885 its Town and Country Journal gave a whole page to sketches of the crowd and the game. Presumably the code depicted here was Rugby Union but it could have been the rival Australian code.

The garrison in Melbourne offered a version of international football which was trebly welcomed by spectators because a football match against the other colonies was still out of the question. Even 89 to visit Ballarat was too expensive an outing for most of the metropolitan clubs, and on the few such visits in the 1860s many members of the visiting clubs could not afford the fare or, if they could, failed to gain their employer’s permission to be absent from work in order to catch the Friday evening train. To visit Bendigo was even more of an adventure. Harrison probably did not play in Bendigo during his whole football career.

The first city team to visit Bendigo was South Yarra. In 1872, on the verge of its extinction as a football club, it accepted the challenge from Sandhurst Club and sent its available players to Bendigo by train. Only sixteen footballers made the journey and they played Sandhurst’s eighteen at the large Kangaroo Flat cricket ground on the outskirts of Bendigo on the public holiday called Separation Day. South Yarra kicked one goal late in the afternoon, before the ball was accidentally burst and the match came to an end. A fortnight later the Melbourne team arrived in Bendigo on the Friday evening train and stayed in the Shamrock Hotel, but the disappointment was keen when the Sandhurst football club heard that only fourteen Melbourne players had made the journey, and so Saturday’s game was fixed at fourteen a side. It would be an exhausting day for both teams, for the ground was wet and slippery, the wind was blowing in gusts, and the teams had agreed to play for three hours. Players fell flat on their backs in the mud, those trying to kick against the wind were often lucky to drive the ball 20 yards, and the game seemed likely to end without a goal until Goldsmith of Melbourne took the ball from a scrummage in the centre and ran like a hare. His driving drop kick landed close to the goal and then ‘with a good bound, went clean through the posts’.

Further upcountry – far beyond the terminus of the railway system – the football clubs had no opportunity of a visit from footballers living in Melbourne, Geelong or Ballarat. In southwest Victoria, where football was reborn after its quick death in the early 90 1860s, the inland town of Hamilton and the two ports of Warrnambool and Port Fairy occasionally played each other with teams ranging from 15 to 20 players. Their matches were social events, and when the Port Fairy team came to Warrnambool to play football on the racecourse in May 1868, the play commenced at 1.30, was adjourned in mid-afternoon to enable luncheon to be eaten at the Steam Packet Hotel, and was then resumed with ‘the utmost good feeling’ until 5 pm. When Hamilton sent its football team by horse coach to Warrnambool one month later, the visit aroused such excitement that the main business at the port closed their doors on the Thursday afternoon of the match. The day was long remembered because Warrnambool was about to score its second goal when a bystander accidentally stopped the ball with his foot.

In these towns the footballers played with a stamina that would have astonished the city footballers. On the great winter holiday of 1868, Separation Day, Port Fairy commenced its home game against Warrnambool in the morning, kicked with the aid of the wind for four hours, and after adjourning for luncheon it proceeded to defend against the wind for one and a half hours until darkness set in, ending the game. Complete exhaustion must also have been setting in by 10 pm because normally the upcountry matches ended with a banquet, songs, speeches and ‘loyal and patriotic toasts’.

Ballarat was a special side-window on the way football, in about 1870, was changing. While football was still mainly a game for young men working in stiff-collar professions and possessing ample leisure, it was beginning to attract a few of those who worked long hours at manual tasks. The game thus gained players who often had a formidable strength and a willingness to use it on the football field. The company-owned mines in Ballarat were a particular source of such footballers because their miners, by the standards of the era, worked short hours and thus had some leisure for football.

In a suburb of Ballarat, in the heartland of the big gold mines, the Redan football club was formed about 1870. Possibly Redan’s players were the strongest to appear in Australian football up to that time. When they lumbered onto the field, many opposing players, fresh from their office desks, must have shivered with apprehension. Redan’s players were mostly tributers – the self-employed miners who leased parts of the famous Band of Hope and other gold mines. Judging by their surnames most were Irish. Upcountry cousins of the soldiers who played briefly in Melbourne, their impact was similar.

The news that Redan would play the Ballarat team on 2 September 1871 – possibly their first encounter – drew a crowd to the wet and rocky surface of Wynn’s Paddock, not far from the lake. The game was no sooner started than many of the lighter Ballarat players were skittled. They were bumped, they were charged, they were bear-hugged and they were kicked, though this was more the result of clumsiness than of malice. The Ballarat Star even alleged that the Redan bruisers had ‘no scruples in tripping, and worse’. The meaning of ‘worse’ was probably the player’s collarbone reportedly broken. The umpire thought Redan was sometimes too rough even for a game which permitted a liberal degree of roughness and had no general rule debarring rough play. When he awarded free kicks against Redan players, they vigorously protested. At times a free fight seemed likely to replace the football game.

The teams played a return match on the same paddock on the very late date of 21 October, and the good spirit of the Redan players was applauded. Their 40 stone of additional weight ceased to be a bonus on a firmer ground and Ballarat kicked the only goal scored during the two encounters. These matches were probably a landmark in the history of Australian football, for they brought together residents of diverse occupations and social classes.

Ballarat was still sufficiently isolated from Melbourne and Geelong to have its own interpretation of the rules, and indeed most Victorian regions during football’s first twenty years were inclined to adopt local variations of the rules. So long as a town played no other team from far away, it could happily follow its own rules. Moreover, so many important facets of football were not yet specifically covered by the formal ‘Laws of the Game’ that upcountry umpires tended to conjure their own interpretations.

A big crowd depicted at the old football ground in the early 1880s with the Melbourne Cricket Club’s reversible grandstand to the right. By then the arena was moving from a rectangular to an oval shape (The Australasian Sketcher, 27 July 1883).

When Ballarat went to Geelong to play at the Corio ground on 19 August 1871, it became entangled in an episode which suggested that its own style of playing was now more rugged than that of the clubs on the shores of Port Phillip and Corio bays. The ball was kicked towards a Geelong forward. He seemed likely to catch it and, as the custom was, call out ‘Mark’, when at the last moment the Ballarat captain ran from behind. The Geelong forward, to his 93 indignation, ‘was pounced upon and brought to earth by the gallant captain’. At once he was awarded a free kick, because the rules prohibited the slinging of a player unless he held the ball. The Ballarat footballers were flabbergasted at the umpire’s interpretation. Although the Geelong forward failed to score with his free kick, the Ballarat players were in high indignation as they journeyed home. Their local newspaper shared the indignation. The episode seemed additionally unfair because Geelong specialised in a long-kicking game whereas Ballarat favoured a style that was full of what the Courier called ‘dodgings and capsizing’. The Ballarat captain was a champion capsizer, it was said, and was simply practising his art when the one-eyed umpire intervened.

For a time the club football in Ballarat possessed a bonecrunching quality seen less often in Melbourne now that the soldiers had sailed away. At Ballarat’s first scratch match of the 1872 season the injuries were too numerous for a game of fun. The play was punctuated by pauses in which the sick and injured were helped either to their feet or to the makeshift stretcher. There was apparently no malice, merely mayhem. In the course of a few hours of chasing the ball, or felling opponents who were also chasing it, Killen fractured his collar bone, ‘young Fisher’ broke a rib or two, and Davidson limped from the field with blood trickling down his leg. Searching for a remedy, Ballarat tried a revolutionary rule which is now a vital part of Australian football – a ban against pushing a running player in the back. The rule was years ahead of its time and before long was dropped.

A footballer’s collar-bone was vulnerable so long as the rules specifically allowed a player running rapidly to be pushed in the back. The new practice which Harrison pioneered, of running long distances while holding and bouncing the ball, was still so resented by the backmen that they could not dream of foregoing their legitimate tactic of pushing the running player hard in the back. 94 Pushing from behind generally remained illegal, but a clear exception was made ‘when any player is in rapid motion’.

Most footballers in these years displayed goodwill as well as ruggedness. Goodwill was especially needed to buttress all the unwritten rules, because the unwritten rules must have far exceeded the dozen written rules. One unwritten rule was that players should try to keep the ball in play, but it so happened that a team defending strongly in the face of a gusty wind sometimes saved the match by repeatedly keeping the ball near the boundary flags or deliberately kicking the ball out of bounds. As the rectangular

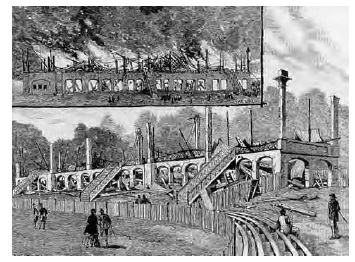

The Melbourne Cricket Club in the 1870s built an unusual grandstand which could be so altered that it faced the cricket arena in summer and then faced the outside football ground in winter. The grandstand burned down in September 1884.

ground contained deep forward-pockets or corners, and as Australian football did not permit the corner-kick so useful in soccer, and as it did not allow the Rugby method of scoring a try along every point of the goal-line, there was a clear incentive for the backline players deliberately to place the ball out of bounds near the goalposts. The full-back of their own team was then rewarded with a free kick. He did not have to kick from what is the present goal square but could kick the ball back into play from a position some 20 yards out from the kick-off or behind posts: in an era of weaker kicking that was a big advantage. The defenders were therefore 95 favoured by the early rules, and many backmen gave a foretaste of those famous Melbourne defenders of the late 1950s who drove the ball to the boundary.

When in 1872 the Geelong team visited Ballarat on the great public holiday of the football season, Separation Day, it won first use of the strong wind in the puddles of Wynne’s Paddock but failed to score a goal after ninety minutes of attacking. Ballarat then had its turn with the wind but found Geelong defending with ease by playing the ball out of bounds. As Ballarat at the time had a powerful side, the local supporters became angry at the constant thwarting of their heroes’ skill. A few spectators actually hissed. Even now, after all these years, we can almost hear the sound of the hisses competing with the rush and rustle of that blustery wind near the shores of Ballarat’s lake. We can sympathise with the frustration that gave rise to hiss after hiss from the watching miners. For miners were among the supporters of a Ballarat team which had cunningly strengthened itself by recruiting three heavyweight players from nearby Redan. But to the football officials who wore gold watch and chain and a high black hat, the idea of hissing during a football match was abhorrent. What would respectable citizens say in Melbourne when they heard that loud hissing had swept across a sportsfield in proud Ballarat? Officials of the Ballarat football club, eager to defend the reputation of all sporting clubs on the goldfields, expressed a hope that ‘this kind of feeling will never be displayed again in any match or under any circumstances’. The Ballarat Star was also shocked, denouncing the hissing as a sign of ‘ignorance and bad taste’. What those Ballarat worthies would think of a football grand final or a night cricket match in Melbourne, more than a century later, we can only guess.

It almost seemed as if football had reached a new stage of competitiveness that disowned the old sportsmanship formally praised by the founders of the game. But the founders did not disown the 96 new era; they helped to initiate it. Geelong that day was captained by Tom Wills himself. Now aged thirty-six, he was as shrewd in tactics at football as at cricket. It was he who helped to provoke the gale of hisses. To him football was still to be played like a preparation for war. Once the match was ended, however, he believed in peace, and he made a pithy, friendly speech at the banquet and sang ‘Auld Lang Syne’ at the railway station when his team was farewelled with handshakes and the waving of hats.

How the footballers behaved on the field was a topic of wider public concern than today. Football was seen not simply as a form of recreation – the blowing away of cobwebs, the recharging of batteries – but as a training ground in character and morality. One reason why the new game received such wide support in Victoria was that it was believed to cultivate courage and self control. ‘Muscular Christianity’ was the phrase on many schoolteachers’ lips as they extolled the virtues of a fair but hard game of football. For their part, many politicians saw the new football code as an ideal training ground for war should an invader threaten Australia. In the aftermath of the revolution in Paris in 1871, football was also seen as a potential soother of civil unrest because it was capable of bringing together on the same strip of grass the rich and the poor, the genteel clerk and the rough foundryman, and men drawn from every economic, social and religious background. In theory, but not always in practice, football broke down social divisions.

The era had not yet arrived when sport was larger than life, and was seen as its own justification. In what was often called the great game of life the footballers of the 1870s still belonged to the little league.

*To ‘lick’ a man in the face was to hit him.