Shelflike Mushrooms, Puffballs, Morels, and Jelly Fungi

Shelflike Mushrooms

All three of the edible species covered in this section on shelflike mushrooms are fleshy members of the Polypore family, though they are classified within three separate genera. While most polypores are hard and woody, these three are fleshy and soft. There are no known poisonous species among the polypores.

Polypores are distinguished from other fungi primarily by two field characteristics: they usually grow on wood, and they have pores (not gills or teeth) on their undersurface. This is a particularly safe, though rather limited, group of edible mushrooms for beginners.

Puffballs

Almost everyone has noticed puffballs. The characteristic puffs of smoke produced when a mature puffball is touched or stepped on always delight children. This “smoke” is actually a cloud of spores. Puffballs differ from most other mushrooms in that they produce their spores as an interior mass called the “gleba,” rather than on exterior surfaces such as gills or pores.

Most puffballs are also delicious edibles. The Giant Puffball is one of the world’s best-known and most widely distributed edible wild mushrooms. Its huge size—some specimens exceed two feet in diameter—makes it easily identifiable. Several similar species of large puffballs are equally prized as food, and one good-sized specimen is sufficient to serve as a side dish for a very large and hungry family. There are also several smaller edible puffballs. Everyone who has ever taken a summer or fall walk in the woods has noticed them, but few realize that most woodland varieties are every bit as delicious as the larger ones. What the smaller species lack in size, they make up for by their usual abundance. A common species of “puffball” (actually, this is a false puffball), the Pigskin Poison Puffball (see p. 164), is toxic, and it can be easily identified by its leathery, warted exterior skin, as can its untrustworthy brothers.

Most edible puffballs grow on the ground. The most common exception is the Pear-shaped Puffball, which grows in clusters on stumps and logs. The edible species have two principal field characteristics in common: a relatively thin and resilient skin on the outside and an initially pure white interior. As a puffball matures, the solid white interior develops a greenish, yellowish, brownish, or purplish coloration and soon turns into a powdery mass of spores. Without exception, puffballs should only be eaten when the interior is pure white. Once the gleba starts to change color, each species has the potential of causing gastrointestinal upset.

The various edible puffball species taste quite the same. Attempting to describe the flavor would be pointless because it is truly unique. The texture is just as delightful and somewhat like French toast. Devotees of the large species are always thrilled to find a specimen in good condition. That’s the biggest problem with puffballs. They start to mature quickly, and once they are, they’re no longer fit for the table. For this reason, a puffball is a true gourmet mushroom—if it’s not perfectly fresh, forget it.

Some people have allergic reactions to some species of puffballs, particularly the Giant. These allergies develop, at least in some cases, after years of eating them. In the absence of any evidence to the contrary, and considering the similarities in taste and texture between the numerous species, it would be wise for persons suffering such reactions to avoid the entire group lest they have a serious reaction to a species new to them that may produce the same reaction. Allergic reactions tend to worsen each time a susceptible individual is exposed to the allergen.

Morels

There is only one genus—Morchella—of true morels. These are all safe, delicious edibles, highly prized by mushroom lovers and gourmets alike. In some areas, they’re hard to find; in other areas, they’re as common as weeds. Consider yourself lucky if you live in their midst.

All three species that are recognized by most North American mycologists are covered in this single section. Several varieties that may be (but haven’t been conclusively proven to be) separate species are known to be safe; they’re covered by the key identifying characteristics and description here also.

Beware of false morels offered by neighbors. Three genera of so-called false or early morels—Verpa, Gyromitra, and Helvella—are all either proven to have or suspected of having toxic species. Stay with the real thing, and you’ll avoid unpleasant possibilities, including cancer that may not develop for decades after you’ve enjoyed such “treats.”

Jelly Fungi

The jelly mushrooms are, perhaps, the mushrooms least likely to be called such by those who are unfamiliar with the Fungi Kingdom’s remarkable diversity. The flesh of these jellylike fruiting bodies is always distinctly gelatinous, a characteristic that will readily distinguish them from all other groups of mushrooms. Most jelly fungi produce irregular, bloblike mushrooms; the two species described here are among the few with a more distinctive form. No jelly mushrooms are suspected of being poisonous, but their only redeeming culinary value is the sheer novelty of their form. They demand the gourmet cook’s creative magic to give them taste and to present them in a manner that will please the eye, for they have no flavor of their own.

Polyporus squamosus

Dryad’s Saddle (Polyporus squamosus)

KEY IDENTIFYING CHARACTERISTICS

1.Fleshy, lateral-stalked, fan- or saddle-shaped, shelflike mushroom, four or more inches wide, with flattened, tan to brown scales on top

2.Undersurface covered with minute, polygonal, white to yellow pores

3.Interior flesh moist; white with or without brownish marbling

4.Found clustered on logs, stumps, or trees

DESCRIPTION: This mushroom is at first almost cylindrical, usually in clusters of several “fingers” (or stalks) that are white to tan except for the ends, which are yellowish brown and depressed. In this immature form, tiny, honeycomblike pores can be seen on the lower side of each finger. As it grows, the end of each finger flares out to become the edge of the cap. The upper surface continually develops brownish, flattened, fibrous scales, showing yellowish tan flesh between. Soon the cap becomes fan or saddle shaped; the pores, which extend onto the stalk, become deeper and wider. The stalk thickens and toughens, darkening until the base is black and quite hard. Fully grown caps range from four inches to one foot or more in width and project nearly that far from the wood on which they’re growing. The pores are yellowish white to yellow in mature specimens. The flesh is white, usually marbled with brownish streaks near the upper cap surface, and has a distinct aroma similar to cucumber or watermelon rind. The spore print is white.

FRUITING: Dryad’s Saddle is usually found in overlapping clusters (but sometimes singly) on deciduous stumps and logs and on dying trees. Within its range—mostly northeastern North America, but as far south as North Carolina and into the Midwest—it is extremely common in spring but less so during summer cold spells and in the fall. This distinctive species is especially abundant on elm, beech, birch, oak, maple, and willow. Each stump will produce mushrooms for at least several years, often more than once in each season.

SIMILAR SPECIES: This is the most common of a very few large, fleshy, shelflike polypores; there are no dangerous look-alikes. A few other Polyporus species are vaguely similar to Dryad’s Saddle, but no other fleshy species of this size closely match its appearance. The scientific name simply means “scaly polypore.”

EDIBILITY: If the morel is the “lobster” of springtime mushrooms, then Dryad’s Saddle is that season’s meat and potatoes. Within its range, this conspicuous fungus is easy to find—it fruits on deciduous stumps, often in great quantity, especially during spring. And while Dryad’s Saddle—some call it the Rider’s Saddle or Pheasant’s-back Polypore—isn’t as prized as the morel, its unique flavor is good. Dryad’s Saddle’s big spring season is a sure sign of morel season, and it can provide a hefty consolation prize for the unsuccessful morel hunter.

The only problem with this species is its toughness. Young, fresh specimens are quite tender—enough so to slice and dry them for later use—but whole, mature ones are often too tough to be considered palatable.

Most mushroom hunters familiar with this species harvest it by simply slicing off only the most tender edges of the caps, leaving the rest behind. Determining how much of the cap edge to harvest is easy enough: if a moderately sharp knife slices through it readily, you won’t be disappointed. But cut the rest of the mushroom off the stump anyway. The mycelium will be more likely to fruit again in the same year. Cook the pieces slowly, but don’t overcook them. Otherwise, even the most tender pieces will become chewy, with a taste and texture similar to burned pork chops (actually, this may appeal to some barbecue fanatics with good teeth). Dryad’s Saddle can be eaten raw, too, but only in modest quantity. Tender slices have a slightly crunchy texture, and the flavor is somewhat like watermelon (but without any sweetness). These can add a nice touch to salads.

Consider yourself lucky if you find some of the strange-looking, immature fingers of Dryad’s Saddle. At this stage, the entire mushroom is quite tender and generally richer in flavor. If you get to the Saddles later than that, there is another option. Cut the whole mushroom off the wood. When you cook it, simmer it for awhile, discard the mushroom, and strain the liquid. This will make a fine base for soup, gravy, or sauce.

SULPHUR SHELF

Laetiporus sulphureus

KEY IDENTIFYING CHARACTERISTICS

1.Shelflike, stalkless mushroom found in overlapping clusters on trees, stumps, or logs

2.Upper surface smooth to suedelike, bright orange

3.Undersurface bright yellow with tiny pores

Sulphur Shelf (Laetiporus sulphureus)

Young fresh caps of the Sulfur Shelf. Note bright sulfur-yellow cap edge. Caps become dull orange as they age.

DESCRIPTION: The mushroom is fan to kidney shaped, stalkless, and shelflike; it is bright yellowish orange to orange on the upper surface and bright yellow on the undersurface. Each shelf is two to ten inches wide, projecting one to six inches from the wood it’s growing on, and one-half to three inches thick. The top surface is smooth at first, becoming minutely suedelike; the undersurface is composed of tiny pores. The edge of each cap is noticeably wrinkled or folded. A longitudinal section reveals pale yellow to pale orange flesh, literally dripping with moisture when fresh. In age, the bright orange and yellow colors fade until the mushroom is white and the flesh becomes dry and chalky, at which stage the mushroom is inedible. The spore print is white.

FRUITING: This strikingly beautiful mushroom is usually found in overlapping clusters, sometimes totaling fifty pounds or more. It is most commonly found on deciduous trees, stumps, and logs, but also sometimes on conifers. It is found throughout much of North America. It fruits mostly from midsummer through midfall, but it is sometimes found as early as midspring or as late as early winter. It will frequently fruit a second time during the same season on the same tree, stump, or log, especially if the first fruiting was harvested. It also tends to grow on the same tree, stump, or log for several years in succession.

SIMILAR SPECIES: No other polypore looks like the Sulphur Shelf. There is a paler variety (L. sulphureus var. semialbinus), which is edible and typically pale orange on top and white on bottom.

EDIBILITY: The Sulphur Shelf reportedly causes gastric upset, at least in some people, particularly when it is picked from Eucalyptus or hemlock trees, or from some other conifers. Such specimens are best avoided. A recent report also suggests that alcoholic beverages should be avoided if one consumes specimens found growing from honey locust trees; those who ignore this warning may experience nausea and vomiting. The Sulphur Shelf has also been known to cause allergic reactions, including swollen lips, in a few individuals. Most fans of this colorful edible insist that it must be collected and cooked while it is very fresh, actually dripping juice when it is cut. Some mycophagists, though, prefer it after it has aged a bit and isn’t so wet.

During a late summer trip to the Tug Hill Plateau east of Lake Ontario, I spotted an immense cluster of Sulphur Shelves as my truck bounced down an old logging road. I stopped, got out of the truck, and walked over to the tree. The cluster extended at least ten feet up the north side of a huge black cherry tree, but the lowest part of the cluster was eight feet above the ground. Without a ladder, I had one chance: a large fallen branch was leaning against the tree.

Using a long, sturdy pole as a brace, I carefully inched my way up the log. I was grateful—the mushrooms were so fresh that they dripped at the slightest touch! Bracing myself with the pole in my left hand, I pulled my pocket knife out with my right, opened it, and stuck it into the trunk. I reached into my back pocket for a folded paper lunch bag, shook it open, and carefully set it down on the log. I pulled the knife from the wood, cut off a nice, wet slice of mushroom, and managed to hold onto it with my knife hand. I aimed carefully, then dropped it into the bag.

I continued until the bag threatened to burst, then reluctantly worked my way back down the log. On the way home, I kept second-guessing myself about a dozen other ways I might have been able to harvest more. I had five or six pounds, but I left another fifty pounds on the tree. It never fails: the less prepared I am, the more mushrooms I find.

–DAVID FISCHER

The alternate common name, the Chicken Mushroom, is a culinary comparison: its flavor and texture are, indeed, remarkably similar to those of chicken breast fillets. Perhaps this is an unflattering comparison. Most people who enjoy the Sulphur Shelf would argue that it is superior to its fowl namesake. Nonetheless, it is often substituted in traditional chicken dishes, producing recipes from Mock Chicken Cacciatore (p. 224) to Faux Coq au Vin.

From a calorie-counting perspective, this is an ideal species. Like most mushrooms, it has negligible caloric value and could thus help justify the cheeses and other fattening ingredients that are used in so many wonderful chicken recipes.

When you find a fresh cluster of Sulphur Shelf mushrooms, use a sharp knife to cut each shelf off as close as possible to the tree, stump, or log. When it’s juicy, the Sulphur Shelf usually requires little or no cleaning, and insects are rarely a problem.

Unlike most mushrooms, the Sulphur Shelf can be frozen uncooked with little or no damage to its flavor or texture. This is fortunate indeed, considering that one large tree will sometimes yield fifty pounds or more of this excellent edible. Some mushroom hunters eat the whole thing, but the moist edge of each shelf is decidedly the most tender part.

BEEFSTEAK POLYPORE

Fistulina hepatica

KEY IDENTIFYING CHARACTERISTICS

1.Red-topped, shelflike mushroom found growing on wood

2.Flesh moist to juicy; undersurface bears tubes that are not attached to each other

DESCRIPTION: This is a shelflike mushroom shaped somewhat like an oyster shell, three to ten inches wide and 3/4–2-1/2 inches thick. It is orangish red or pinkish red to deep red on top. Its pinkish red flesh is juicy and rather gelatinous when fresh. The undersurface bears very small tubes that are free from each other; the pore surface appears yellowish brown to reddish brown. When a stalk is present, it is lateral, short, and thick and colored like the upper surface of the cap. The spore print is pinkish salmon to pale orangish brown.

FRUITING: The Beefsteak Polypore is found only on oak or chestnut wood, either at the base of a tree or on a stump or log. It is found in eastern North America, most frequently in the southeast, and it is uncommon in the northeastern United States and Canada. It fruits in summer and fall.

JB Beefsteak Polypore (Fistulina hepatica)

SIMILAR SPECIES: No other mushroom comes close to this distinctive species.

EDIBILITY: This unmistakable species is a subject of much disagreement among ardent mycophagists at mushroom club meetings. Some rate its al dente texture and tart, acidic flavor the highest; others decry it as a sour-tasting waste of time in the field as well as in the kitchen. Without doubt, there is a significant difference in the qualities of fresh, juicy specimens and older, drier ones, but these variances don’t likely account for the wide-ranging opinions of experienced mushroom eaters. Rather, it is the eclectic nature of taste.

This is one of only a few species that we can recommend as a safe edible uncooked. Those who do enjoy it like to cut it up raw and toss it into salads. The Beefsteak Polypore should be cooked over low heat in order to preserve its tender texture. It can also be frozen fresh.

GIANT PUFFBALL AND ALLIES

Langermannia gigantea Calvatia sculpta

C. booniana

C. cyathiformis

C. craniformis

KEY IDENTIFYING CHARACTERISTICS

1.Large (four inches to two feet wide), white to light brown, round mushroom; surface smooth to coarsely warted

2.Interior solid, undifferentiated, white (no gills or stalk)

3.Found on the ground, not on wood; not clustered

DESCRIPTION: These species all share a single key trait: the interior is a solid white mass (gleba) of feltlike tissue. There is no true stalk, but some species have a sterile basal structure, the flesh of which is spongy. The Giant Puffball (Langermannia gigantea) is particularly huge—up to two feet or more in width. It is covered by a smooth, feltlike skin, and it is sometimes creased, almost like buttocks, on the outside. The Purple-spored and Skull-shaped Puffballs (Calvatia cyathiformis and C. craniformis) are very similar, but never quite so huge. The Purple-spored Puffball usually has a pinkish tan exterior; the Skull-shaped Puffball has a whitish skin and large wrinkles near the base. The Western Giant Puffball (C. booniana) grows as large as the Giant Puffball, but the outer surface is covered with tan, polygonal “warts.” The Pyramid Puffball (C. sculpta) is very distinctive: it is covered with pointed, pyramid-shaped warts. In each case, the interior eventually begins turning into a mass of powdery spores, ranging in color from brownish yellow to rich purple.

Giant Puffball (Langermannia gigantea)

EJ Purple-spored Puffball (Calvatia cyathiformis)

At maturity, the outer skin of these species cracks or splits open, or even breaks free from the base, allowing the wind to disperse the spores from the cuplike base, which remains in place. In others, the entire puffball breaks free from the ground and is blown about by the wind.

EJ Skull-shaped Puffball (Calvatia craniformis)

KS Western Giant Puffball (Calvatia booniana)

FRUITING: These species appear in a variety of habitats and have various ranges as well. As a group, one or another can be found almost anywhere on the continent except along the Gulf Coast and in the Deep South. The Giant Puffball is found throughout most of North America east of the Mississippi River and in California. The Skull-shaped Puffball is quite widespread; the Western Giant Puffball is restricted mostly to arid areas, such as the southwestern United States, and as far north as Idaho. The Purple-spored Puffball is rarely found in Canada or west of the Rocky Mountains. The Pyramid Puffball is found mostly in western North America, especially in the Pacific Northwest.

The Giant and Purple-spored Puffballs are primarily lawn mushrooms, though the Giant is also frequently encountered in open, wooded areas. The Skull-shaped Puffball prefers open woods, and the Western Giant Puffball is usually found in brushy areas. The Pyramid Puffball is found under conifers at higher elevations. The Skull-shaped, Purple-spored, and Giant puffballs fruit mostly from late summer through midautumn; the other two species are encountered as early as late spring.

During September in upstate New York, I put a lot of miles on my car. I drive—sometimes aimlessly, sometimes along a carefully planned route—slowly but, I suppose, rather dangerously, as my eyes scan every meadow, pasture, and open grassy area along the way. No other mushroom is so perfectly suited for this type of four-wheel foraging: the large white puffballs are very easy to spot from the road.

I do wish, though, for laws prohibiting people from carelessly leaving volleyballs lying around in their yards and from painting large rocks white. This foolish, irresponsible behavior causes a great deal of unnecessary wear and tear on my car’s brakes and wastes a lot of my time.

My wife, Leisa, is among the many people I know who prefer puffballs over every other kind of mushroom they’ve ever tried. My in-laws have a patch of bad grass, not thirty feet from their barbecue area, that produces at least a few large puffballs each year. I maintain that this is my wife’s dowry. She is only grateful that her parents don’t compete for these delightful mushrooms.

These are the only mushrooms whose lawn-owners regularly deny me permission when I knock at the door and ask if it is OK to pick some. I therefore have recently embarked upon a new, more scientific approach with folks when I spy large puffballs on their lawns: I tell them that I am conducting important mycological research.

–DAVID FISCHER

WS Pyramid Puffball (Calvatia sculpta)

In each case, only one to three specimens will usually be found in a given area, but the Giant, Western Giant, and Purple-spored puffballs sometimes form fairy rings of up to a dozen mushrooms or more. The large puffballs tend to fruit year after year in the same spot.

SIMILAR SPECIES: The Sculptured Puffball (Calbovista subsculpta) is edible and is nearly identical to the Pyramid Puffball but has less conspicuous, somewhat flattened warts. It is commonly collected at higher elevations in the Rocky Mountains, northern California, and the Pacific Northwest. Several other less common species of Calvatia and their allies closely resemble one or another of the species described in this section, but none are suspected of being poisonous; however, among the smaller false puffballs, there is one notable, poisonous species: the Pigskin Poison Puffball (Scleroderma citrinum; see p. 164). Its interior is only white for a very short time, quickly turning purplish black with white marbling. Even when young, it can be easily distinguished from the edible puffballs: it has a very tough, rindlike skin, which is covered with minute warts that won’t rub off, and a very firm interior.

EDIBILITY: The Giant Puffball, sometimes classified as Calvatia gigantea, is probably the world’s best known edible wild mushroom; its sizable relatives are less commonly known but equally delicious. Two cautions apply to all edible puffballs. They should be cooked soon after picking, while the interior is still pure white. Also, some people experience indigestion after eating puffballs, particularly the Giant. For this reason, it is wise for each individual to eat only a small portion the first time.

KS Sculptured Puffball (Calbovista subsculpta)

Puffballs, especially the Giant, are immensely popular among ruralists in many regions. Occasionally, they even show up at farmers’ markets. Most urban gourmets, however, are not familiar with puffballs. This is mostly because puffballs, unlike most recognized gourmet-quality mushrooms, cannot be dried or otherwise preserved in a way that effectively retains their delightful texture and flavor. The only practical way to preserve them is by freezing raw or partially cooked slices, but this is strictly a short-term option. The slices must be carefully separated by layering waxed paper between them, and extreme care must be taken to prevent freezer burn. It is equally critical to prevent moisture in the freezer from forming ice on the frozen slices. Either of these problems will turn a wonderful culinary delight into a wholly mediocre mushroom. Frozen slices should be cooked immediately after they are removed from the freezer. If they thaw first, they will be a disappointment.

Those who know the Giant Puffball and its large relatives almost invariably rate them very high. If some individuals would employ trickery for a basketful of morels or chanterelles, others would lie, cheat, or steal to get their hands on a large, firm, fresh Giant Puffball. The delicate taste and texture are truly unique and wonderful.

Only two cooking techniques are recommended: The simple slice-and-sauté approach, and the batter-dip-first technique. In either case, go easy with the spices because the delicate flavor is easily overwhelmed. Also, puffballs should be cooked slowly over low heat; otherwise, they will dry out, produce a lot of smoke, and become somewhat bitter.

There are two primary competitors in the race for fresh, large puffballs: centipedes and tiny, wormlike larvae. The former often create fairly large tunnels at the base of the mushroom, but they can be ousted as easily as slugs. The latter, though, are frequent victors. They begin their invasion at the bottom and then work their way up. Consequently, they sometimes only ruin half of the puffball. Puffball devotees often find it necessary to carefully dissect each specimen and remove the infested areas. “It is,” they smile and say, “worth the effort.”

GEM-STUDDED AND PEAR-SHAPED PUFFBALLS

Lycoperdon perlatum

L. pyriforme

KEY IDENTIFYING CHARACTERISTICS

1.White to tan mushroom without well-defined stalk or cap; no gills or pores present

2.Longitudinal section reveals white flesh throughout

3.Close inspection reveals no stalk or gills inside

4.Exterior surface covered with tiny, granular spines that rub off easily; or found clustered or grouped on wood

5.Outer skin not tough or leathery (easily cut with fingernail)

DESCRIPTION: The Gem-studded Puffball (Lycoperdon perlatum) is a white to pale tan, ball- to pear-shaped mushroom without a well-defined stalk or cap; its surface is coated with tiny, granular spines, most of which are easily rubbed off. It is 1–2-1/2 inches wide and 1-1/2–3-1/2 inches high. Longitudinal section reveals pure white, undifferentiated flesh throughout. In age, the interior becomes greenish brown and powdery, and a “pore” opens on the top surface of the mushroom.

The Pear-shaped Puffball (L. pyriforme) is very similar, but it has a smoother surface and typically lacks the Gem-studded Puffball’s exterior spines. It is usually slightly smaller than the Gem-studded Puffball, but in some areas, specimens are frequently gathered in autumn that are quite large—as much as five inches high. A longitudinal section will reveal a section of sterile flesh at the base, which is more spongy (less dense) than the upper flesh.

FRUITING: Both species fruit from middle or late summer through middle or late fall and are found throughout most of North America. The Gem-studded Puffball is found singly to grouped or scattered, rarely in clusters of two or three, on the ground. It usually occurs in woods but also appears in a variety of other habitats. The Pear-shaped Puffball almost always grows in groups or clusters of at least three specimens and is always found on wood or wood debris.

SIMILAR SPECIES: There are a number of closely related species of small puffballs that are difficult to distinguish from these two common ones. There have been only rare reports of adverse reactions to any of these, despite frequent consumption by avid mushroom enthusiasts. It is important to rule out white Amanita buttons, but this is easily accomplished if one adheres to all the key identifying characteristics listed above. Some species of false puffballs—such as the Pigskin Poison Puffball (Scleroderma citrinum), which is poisonous (see p. 164)—have white interior flesh when young; however, they can be ruled out by their leathery tough, rindlike skin.

The Gem-studded Puffball was previously classified as L. gemmatum; it is also referred to as the Devil’s Snuffbox.

Gem-studded Puffball (Lycoperdon perlatum)

Pear-shaped Puffball (Lycoperdon pyriforme)

EDIBILITY: These common puffballs are every bit as delicious as their larger, more frequently collected cousins. The smallness of these two species and their equally delicious look-alikes requires that a sizable quantity be gathered for most culinary uses, but when they’re fruiting in abundance, it’s worth the time and effort to gather a basketful. As with all puffballs, these species should be eaten only when the interior is pure white.

These little puffballs’ delicate flavor is best brought out by sautéing them slowly until slightly browned. Specimens should be cleaned, then sliced lengthwise. Although most puffballs taste quite the same, large specimens of the Pear-shaped and Gem-studded puffballs frequently have good-sized sterile (non–spore producing) bases; if cooked separately, these bases taste remarkably like morels.

YELLOW, BLACK, AND HALF-FREE MORELS

Morchella esculenta

M. elata

M. semilibera

Yellow Morel (Morchella esculenta)

KEY IDENTIFYING CHARACTERISTICS

1.Cap appears spongelike or honeycombed (distinct ridges surrounding pits)

2.Longitudinal section reveals single hollow chamber from base of stalk to top of cap

3.Longitudinal section of cap reveals no multichambered interior

4.Cap not draping from stalk as in Verpa bohemica (see photo on p. 166)

DESCRIPTION: The cap appears distinctly spongelike or honeycombed; its entire surface is composed of pits surrounded by ridges. The base of the cap is attached directly to the top of the stalk, except in the Half-free Morel (Morchella semilibera), whose cap’s lower half drapes, like a skirt, below its point of attachment to the upper stalk. The ridges of morel caps range in color from white to almost black, but are most often yellowish brown to gray. Usually the inside of the pits are colored differently from the ridges. The pits of the Yellow (M. esculenta) and Half-free morels are usually dark, and the pits of the Black Morel (M. elata) are usually light. The stalk is textured with minute, granular ribs or bumps and ranges in color from white to yellow.

Slicing a morel open lengthwise reveals that the entire mushroom is hollow, with a single chamber extending from top to bottom. The inner surface of the morel is also textured with minute, granular bumps or ribs. The flesh of the stalk is quite thin, rarely more than one-fourth inch thick, except at the base of the stalk, which is sometimes thicker and multilayered, especially in large specimens.

The entire mushroom varies in height from three inches to one foot or more and in width from two to four or more inches. The proportional height of the cap, in relation to the stalk, is also quite variable. The Half-free Morel’s cap usually makes up less than a fourth of the mushroom’s overall height, while the other species’ caps are usually as tall as the stalks. In the case of the Black Morel, the stalk may make up only a small fraction of the mushroom’s overall height.

This collection of Yellow Morels shows a wide range of colors, shapes, and sizes.

The shape of the cap also varies tremendously. It may be cone shaped and rather pointed at the top, egg shaped, or nearly ball shaped. The stalk, cap, or both are frequently bent (this bending is caused by such obstacles as sticks that the growing mushroom meets).

As this description indicates, morels vary tremendously in size, shape, and color; however, they never vary from the four key identifying characteristics listed above. They are easily identified to the genus Morchella. The spore print, which is usually so slight that it’s rather difficult to obtain, is white, cream, or pale yellow.

FRUITING: Morels are most often found in groups or scattered—but sometimes singly—in a variety of habitats. The Yellow and Black morels are found throughout much of North America, but the Half-free Morel is mostly limited to the eastern half of the continent and the Pacific Northwest. Morels fruit for a period of only four to six weeks in the springtime.

Spring, of course, comes to different places at different times. In the Carolinas, the season’s first morels appear as early as mid-March. In northern Canada and in mountainous areas at high elevations, they usually don’t start fruiting until June. In most places, though, late April through late May is the core of morel season. In areas where morels are found in the greatest abundance—sections of Ohio, Indiana, the Michigan Peninsula, New England, Ontario and Quebec provinces, Northern California, and the Pacific Northwest are fortunate in this respect—foraging for morels is usually fruitless before mid-April.

On the other hand, some areas are practically devoid of morels. Dedicated mycophagists from Long Island, the Gulf Coast, the Great Plains states and much of Saskatchewan, the Southwest desert, and other relatively morel-less areas have been known to travel some distance each May to vacation in morel territory.

TB David Fischer with Yellow Morels

Black Morel (Morchella elata)

Generally speaking, it seems that regions with a lot of snow, sandy or limey soils, frequent forest fires, old apple orchards, or lots of dead elm trees have the greatest abundance of morels.

Describing specific morel habitats is not difficult, but the list of characteristic habitats is long. Most species of mushrooms are found only in very specific habitats, but morels are more difficult to pin down. Morel habitats include forests with spruce, Douglas fir, maple and beech, black locust, cottonwood, tulip, or poplar trees; old apple orchards; areas that have been burned over the previous year; land around dead elm trees; and even lawns or old fields. This broad list might lead one to expect morels everywhere, but experience proves otherwise. With rare exceptions, morels are found only in the kinds of habitats listed above. But precisely where and when is another matter. Morels are, in truth, found only in one place: wherever they choose to appear.

Soil saturation, especially in early spring, seems to be an important factor in morel fruiting. Winters with high snowfall levels and springs with abundant rainfall apparently play an important role in strengthening the mycelium. This, in turn, seems to lead to banner morel years. Flood plains, stream banks that go underwater during early spring snowmelts, and the edges of swamp ridges are widely reported to be prime morel-picking spots. Even in upland areas, rounded gullies that are overrun by water during spring snowmelt and rains consistently produce a more abundant crop of morels than higher, drier ground.

It’s important to note the difference between well rinsed and soggy ground, though; morels don’t fruit when the ground is soaked but rather after the ground has been soaked.a

Half-free Morel (Morchella semilibera)

SIMILAR SPECIES: The Wrinkled Thimble-cap, or Early Morel (Verpa bohemica), which is poisonous (see p. 165) is, at first glance, a dead-ringer for the true morel; however, its cap is not distinctly pitted or honeycombed like a true morel’s cap. Rather, its cap surface is composed of vertically wrinkled ridges that only rarely are joined by horizontal ridges. Its cap drapes, but it is attached only at the very top of the stalk; the Half-free Morel’s cap is attached about halfway down the cap. If a specimen’s cap drapes significantly (some Black Morel caps drape, but only slightly) and seems to conform to the other key identifying characteristics, it must be either an edible Half-free Morel or a poisonous Wrinkled Thimble-cap. Several other differences can help distinguish between these two.

First, the Half-free Morel’s stalk usually has vertical perforations near the base; the Wrinkled Thimble-cap’s stalk lacks them. Second, the outside of the Half-free Morel’s stalk is coated with tiny, granular particles that can be easily rubbed off; the Wrinkled Thimble-cap’s stalk has tiny bumps that do not rub off readily. Third, the Half-free Morel’s cap typically makes up less than one fourth of the mushroom’s overall height; the cap of the Wrinkled Thimble-cap usually makes up at least one fourth of the mushroom’s overall height. Also, the Half-free Morel’s stalk is invariably hollow, and the Wrinkled Thimble-cap’s stalk is normally stuffed with cottony fibers, but slugs often burrow into the mushroom and devour them, leaving no clue that the stalk was originally stuffed.

Poisonous mushrooms of the genus Gyromitra (see Conifer False Morel, p. 166) are commonly called “false” morels because at least to some novices they look similar. Upon close inspection, however, there is little similarity. The cap of a Gyromitra is slightly to grossly wrinkled and folded but not pitted or honeycombed. A longitudinal section of the cap reveals a multichambered interior, not the single, cylindrical, hollow chamber characteristic of a true morel.

At an autumn group foray in upstate New York, a woman produced a tiny wicker basket. “It’s my morel basket,” she said, joking but also lamenting. “I found exactly one morel this spring.”

“I only did twice as well as you did,” said another mycophile, “and I went out looking every weekend for two months!”

Everyone in the group whined longingly for the superior morel harvests of previous seasons. Eager to show off, I brought forth a snapshot of a dozen huge specimens. “Guess I had better luck,” I boasted.

“This year?” asked one man, drooling.

“Yup, second week in June.”

“Where did you find them?” he asked, quickly adding, “I mean, in this county?” He knew full well that there is no better kept secret than the location of a morel patch.

Kindly but cautiously, I gave a few details: about 1,300 feet elevation, mixed maple and beech woods.

I love teaching people about edible wild mushrooms—how to identify them, how to prepare them, even how to find them. But my morel patches are mine alone. I hide my car very carefully when I go morel hunting. I put other species in my basket and stuff the morels inside my jacket. When I spot one, before picking it, I look around like a shoplifter who’s about to pocket a watch, making sure that no one is looking. I am very, very quiet.

And if you happen to bump into me as I leave the woods and ask if I have found any morels, the answer will be no. Not yet. Maybe next week.

And I’ll show you the pictures later.

–DAVID FISCHER

In addition to the Yellow, Black, and Half-free morels, some mycologists apply a number of other names to some morels found in North America. There is little agreement between professional mycologists over which, if any, of these others are truly distinct species. This debate makes for interesting conversation, but it is of little culinary interest. All morels are eminently edible.

Among the species listed in some field guides are Peck’s Morel (M. angusticeps), the Conical Morel (M. conica), M. canaliculata, and M. crassistipa. Many consider these to be only variant forms of the Black Morel. The White Morel (M. deliciosa) and the Thick-footed Morel (M. crassipes) are generally considered to be early and late forms, respectively, of the Yellow Morel.

EDIBILITY: Black Morels frequently cause gastric upset when consumed with or followed by alcoholic beverages, and some individuals have unpleasant reactions to Black Morels even without alcohol. No morels should be eaten raw, undercooked, or in large quantity; eating them so can cause digestive discomfort, also.

These precautions aside, the morel, in its myriad forms, is the clear favorite of most mushroom hunters. The morel reigns supreme among nature’s fungal fruits, esteemed by gourmets on both sides of the Atlantic. During morel season, area mushroom clubs gather specifically to scour the woods and orchards for this king of edible mushrooms.

Recently, attempts to cultivate morels have started to pay off. With such tremendous demand for them, morels may be on their way toward large-scale, commercial cultivation. Some longtime morel devotees worry that this will somehow take away the morel’s special mystique. Others, less romantic or more pragmatic, anxiously await such progress.

In regions where morels are abundant, it is not unusual to see Posted signs expressly forbidding mushroom picking. In areas not blessed with such abundance, patience and perseverance are essential to finding morels. The best foraging tactic is to look as often as possible in as many of the known types of habitat as possible during morel season.

When the searching pays off and you find your first morel, search around the immediate vicinity for more. Then, note as many specifics about where you found them as you can: What kinds of trees, plants, and soil are present? Is the ground sloping? If so, is it sloping to the east, west, north, or south? With these factors in mind, keep looking in similar habitats. This is the most likely way to fill your basket.

Once you’re certain of your identification, cut off the base of the stalk. Then slice the whole morel in half vertically, and gently brush or blow away any insects, dirt, sand, or plant debris.

Morels usually grow in the same place for several years but may skip one or more years between fruitings. Look for them next year wherever you find them this year. If you don’t find any there next year, check again the year after that.

If you try and try, but don’t find any morels, there is another option—many gourmet shops stock dried morels. Be prepared for “sticker shock”: one ounce of dried morels might cost you fifteen dollars or more. That’s a rather steep price for something that’s free when you can find it, but even the most experienced morel hunters have been known to splurge on a small jar when that’s the only way to get some.

JELLY TOOTH AND APRICOT JELLY

Pseudohydnum gelatinosum Phlogiotis helvelloides

Jelly Tooth (Pseudohydnum gelatinosum)

KEY IDENTIFYING CHARA TERISTICS

1.Gelatinous, tongue- to funnel-shaped mushroom, one to four inches long, one-half to three inches wide

2.Flesh translucent, white or gray to brownish; undersurface has tiny soft spines; or flesh apricot to rose; undersurface smooth to slightly wrinkled

DESCRIPTION: The Jelly Tooth (Pseudohydnum gelatinosum) is shoehorn to tongue shaped, with translucent, gelatinous, or rubbery white flesh. It is one to three inches long, including a narrow, lateral, stalklike appendage (sometimes absent); the widest part of the mushroom measures one-half to three inches across. The upper surface is smooth to minutely velvety, white to grayish or brownish; the undersurface is densely coated with tiny, soft, whitish spines.

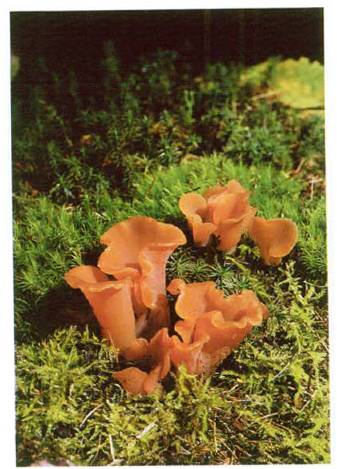

Apricot Jelly (Phlogiotis helvelloides) is very similar in texture and size; however, it is pinkish orange to rose and usually rather funnel shaped but with a split side. It typically stands more erect than the Jelly Tooth and lacks a well-defined stalk. Its upper surface is smooth, and its lower surface is smooth to slightly wrinkled. It also tends to be slightly longer than the Jelly Tooth, standing up to four inches high. Both species produce white spore prints.

JSApricot Jelly (Phlogiotis helvelloides)

FRUITING: Both of these distinctive mushrooms are found throughout most of North America and are associated with coniferous wood. The Jelly Tooth always grows on decaying wood, and Apricot Jelly is more frequently found in moss on logs or on the ground. Both species usually fruit in groups, typically from summer through fall, but either may be found from late spring through midsummer if the weather is cool and rainy.

SIMILAR SPECIES: Neither of these mushrooms can reasonably be confused with any other species.

EDIBILITY: These beautiful, fascinating mushrooms have the same taste and texture. They are thoroughly bland, rather like firm, unflavored gelatin. Nonetheless, the creative gourmet can use these as a delightful culinary novelty. They can be eaten raw, but the gelatinous flesh will take on flavor if marinated, pickled, or candied. Culinary options are as unlimited as the chef’s imagination, and these fungi will certainly be the talk of the table.