[23]

What is it that linguistics sets out to analyse? What is the actual object of study in its entirety? The question is a particularly difficult one. We shall see why later. First, let us simply try to grasp the nature of the difficulty.

Other sciences are provided with objects of study given in advance, which are then examined from different points of view. Nothing like that is the case in linguistics. Suppose someone pronounces the French word nu (‘naked’). At first sight, one might think this would be an example of an independently given linguistic object. But more careful consideration reveals a series of three or four quite different things, depending on the viewpoint adopted. There is a sound, there is the expression of an idea, there is a derivative of Latin nūdum, and so on. The object is not given in advance of the viewpoint: far from it. Rather, one might say that it is the viewpoint adopted which creates the object. Furthermore, there is nothing to tell us in advance whether one of these ways of looking at it is prior to or superior to any of the others.

Whichever viewpoint is adopted, moreover, linguistic phenomena always present two complementary facets, each depending on the other. For example:

(1) The ear perceives articulated syllables as auditory impressions. But the sounds in question would not exist without the vocal organs. There would be no n, for instance, without these two complementary aspects to it. So one cannot equate the language simply with what the ear hears. One cannot divorce what is heard from oral articulation. Nor, on the other hand, can one specify the relevant movements of the vocal organs without reference to the corresponding auditory impression (cf. p. [63] ff.).

[24]

(2) But even if we ignored this phonetic duality, would language then be reducible to phonetic facts? No. Speech sounds are only the instrument of thought, and have no independent existence. Here another complementarity emerges, and one of great importance. A sound, itself a complex auditory-articulatory unit, in turn combines with an idea to form another complex unit, both physiologically and psychologically. Nor is this all.

(3) Language has an individual aspect and a social aspect. One is not conceivable without the other. Furthermore:

(4) Language at any given time involves an established system and an evolution. At any given time, it is an institution in the present and a product of the past. At first sight, it looks very easy to distinguish between the system and its history, between what it is and what it was. In reality, the connexion between the two is so close that it is hard to separate them. Would matters be simplified if one considered the ontogenesis of linguistic phenomena, beginning with a study of children’s language, for example? No. It is quite illusory to believe that where language is concerned the problem of origins is any different from the problem of permanent conditions. There is no way out of the circle.

[25]

So however we approach the question, no one object of linguistic study emerges of its own accord. Whichever way we turn, the same dilemma confronts us. Either we tackle each problem on one front only, and risk failing to take into account the dualities mentioned above: or else we seem committed to trying to study language in several ways simultaneously, in which case the object of study becomes a muddle of disparate, unconnected things. By proceeding thus one opens the door to various sciences – psychology, anthropology, prescriptive grammar, philology, and so on – which are to be distinguished from linguistics. These sciences could lay claim to language as falling in their domain; but their methods are not the ones that are needed.

One solution only, in our view, resolves all these difficulties. The linguist must take the study of linguistic structure as his primary concern, and relate all other manifestations of language to it. Indeed, amid so many dualities, linguistic structure seems to be the one thing that is independently definable and provides something our minds can satisfactorily grasp.

What, then, is linguistic structure? It is not, in our opinion, simply the same thing as language. Linguistic structure is only one part of language, even though it is an essential part. The structure of a language is a social product of our language faculty. At the same time, it is also a body of necessary conventions adopted by society to enable members of society to use their language faculty. Language in its entirety has many different and disparate aspects. It lies astride the boundaries separating various domains. It is at the same time physical, physiological and psychological. It belongs both to the individual and to society. No classification of human phenomena provides any single place for it, because language as such has no discernible unity.

A language as a structured system, on the contrary, is both a self-contained whole and a principle of classification. As soon as we give linguistic structure pride of place among the facts of language, we introduce a natural order into an aggregate which lends itself to no other classification.

It might be objected to this principle of classification that our use of language depends on a faculty endowed by nature: whereas language systems are acquired and conventional, and so ought to be subordinated to – instead of being given priority over – our natural ability.

To this objection one might reply as follows.

First, it has not been established that the function of language, as manifested in speech, is entirely natural: that is to say, it is not clear that our vocal apparatus is made for speaking as our legs for walking. Linguists are by no means in agreement on this issue. Whitney, for instance, who regards languages as social institutions on exactly the same footing as all other social institutions, holds it to be a matter of chance or mere convenience that it is our vocal apparatus we use for linguistic purposes. Man, in his view, might well have chosen to use gestures, thus substituting visual images for sound patterns. Whitney’s is doubtless too extreme a position. For languages are not in all respects similar to other social institutions (cf. p.[107] ff., p.[110]). Moreover, Whitney goes too far when he says that the selection of the vocal apparatus for language was accidental. For it was in some measure imposed upon us by Nature. But the American linguist is right about the essential point: the language we use is a convention, and it makes no difference what exactly the nature of the agreed sign is. The question of the vocal apparatus is thus a secondary one as far as the problem of language is concerned.

[26]

This idea gains support from the notion of language articulation. In Latin, the word articulus means ‘member, part, subdivision in a sequence of things’. As regards language, articulation may refer to the division of the chain of speech into syllables, or to the division of the chain of meanings into meaningful units. It is in this sense that one speaks in German of gegliederte Sprache. On the basis of this second interpretation, one may say that it is not spoken language which is natural to man, but the faculty of constructing a language, i.e. a system of distinct signs corresponding to distinct ideas.

[27]

Broca discovered that the faculty of speech is localised in the third frontal convolution of the left hemisphere of the brain. This fact has been seized upon to justify regarding language as a natural endowment. But the same localisation is known to hold for everything connected with language, including writing. Thus what seems to be indicated, when we take into consideration also the evidence from various forms of aphasia due to lesions in the centres of localisation is: (1) that the various disorders which affect spoken language are interconnected in many ways with disorders affecting written language, and (2) that in all cases of aphasia or agraphia what is affected is not so much the ability to utter or inscribe this or that, but the ability to produce in any given mode signs corresponding to normal language. All this leads us to believe that, over and above the functioning of the various organs, there exists a more general faculty governing signs, which may be regarded as the linguistic faculty par excellence. So by a different route we are once again led to the same conclusion.

Finally, in support of giving linguistic structure pride of place in our study of language, there is this argument: that, whether natural or not, the faculty of articulating words is put to use only by means of the linguistic instrument created and provided by society. Therefore it is no absurdity to say that it is linguistic structure which gives language what unity it has.

§2 Linguistic structure: Its place among the facts of language

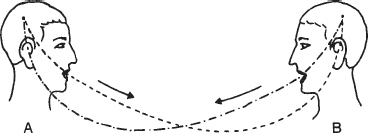

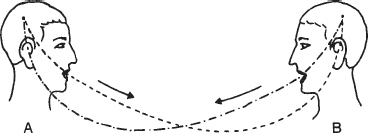

In order to identify what role linguistic structure plays within the totality of language, we must consider the individual act of speech and trace what takes place in the speech circuit. This act requires at least two individuals: without this minimum the circuit would not be complete. Suppose, then, we have two people, A and B, talking to each other:

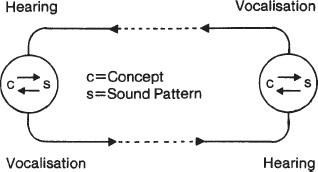

The starting point of the circuit is in the brain of one individual, for instance A, where facts of consciousness which we shall call concepts are associated with representations of linguistic signs or sound patterns by means of which they may be expressed. Let us suppose that a given concept triggers in the brain a corresponding sound pattern. This is an entirely psychological phenomenon, followed in turn by a physiological process: the brain transmits to the organs of phonation an impulse corresponding to the pattern. Then sound waves are sent from A’s mouth to B’s ear: a purely physical process. Next, the circuit continues in B in the opposite order: from ear to brain, the physiological transmission of the sound pattern; in the brain, the psychological association of this pattern with the corresponding concept. If B speaks in turn, this new act will pursue – from his brain to A’s – exactly the same course as the first, passing through the same successive phases, which we may represent as follows:

[28]

[29]

This analysis makes no claim to be complete. One could go on to distinguish the auditory sensation itself, the identification of that sensation with the latent sound pattern, the patterns of muscular movement associated with phonation, and so on. We have included only those elements considered essential; but our schematisation enables us straight away to separate the parts which are physical (sound waves) from those which are physiological (phonation and hearing) and those which are psychological (the sound patterns of words and the concepts). It is particularly important to note that the sound patterns of the words are not to be confused with actual sounds. The word patterns are psychological, just as the concepts associated with them are.

The circuit as here represented may be further divided:

(a) into an external part (sound vibrations passing from mouth to ear) and an internal part (comprising all the rest);

(b) into a psychological and a non-psychological part, the latter comprising both the physiological facts localised in the organs and the physical facts external to the individual; and

(c) into an active part and a passive part, the former comprising everything which goes from the association centre of one individual to the ear of the other, and the latter comprising everything which goes from an individual’s ear to his own association centre.

Finally, in the psychological part localised in the brain, one may call everything which is active ‘executive’ (c → s), and everything which is passive ‘receptive’ (s → c).

In addition, one must allow for a faculty of association and coordination which comes into operation as soon as one goes beyond individual signs in isolation. It is this faculty which plays the major role in the organisation of the language as a system (cf. p.[170] ff.).

But in order to understand this role, one must leave the individual act, which is merely language in embryo, and proceed to consider the social phenomenon.

All the individuals linguistically linked in this manner will establish among themselves a kind of mean; all of them will reproduce – doubtless not exactly, but approximately – the same signs linked to the same concepts.

What is the origin of this social crystallisation? Which of the parts of the circuit is involved? For it is very probable that not all of them are equally relevant.

[30]

The physical part of the circuit can be dismissed from consideration straight away. When we hear a language we do not know being spoken, we hear the sounds but we cannot enter into the social reality of what is happening, because of our failure to comprehend.

The psychological part of the circuit is not involved in its entirety either. The executive side of it plays no part, for execution is never carried out by the collectivity: it is always individual, and the individual is always master of it. This is what we shall designate by the term speech.

The individual’s receptive and co-ordinating faculties build up a stock of imprints which turn out to be for all practical purposes the same as the next person’s. How must we envisage this social product, so that the language itself can be seen to be clearly distinct from the rest? If we could collect the totality of word patterns stored in all those individuals, we should have the social bond which constitutes their language. It is a fund accumulated by the members of the community through the practice of speech, a grammatical system existing potentially in every brain, or more exactly in the brains of a group of individuals; for the language is never complete in any single individual but exists perfectly only in the collectivity.

By distinguishing between the language itself and speech, we distinguish at the same time: (1) what is social from what is individual, and (2) what is essential from what is ancillary and more or less accidental.

The language itself is not a function of the speaker. It is the product passively registered by the individual. It never requires premeditation, and reflexion enters into it only for the activity of classifying to be discussed below (p.[170] ff.).

[31]

Speech, on the contrary, is an individual act of the will and the intelligence, in which one must distinguish: (1) the combinations through which the speaker uses the code provided by the language in order to express his own thought, and (2) the psycho-physical mechanism which enables him to externalise these combinations.

It should be noted that we have defined things, not words. Consequently the distinctions established are not affected by the fact that certain ambiguous terms have no exact equivalents in other languages. Thus in German the word Sprache covers individual languages as well as language in general, while Rede answers more or less to ‘speech’, but also has the special sense of ‘discourse’. In Latin the word sermo covers language in general and also speech, while lingua is the word for ‘a language’; and so on. No word corresponds precisely to any one of the notions we have tried to specify above. That is why all definitions based on words are vain. It is an error of method to proceed from words in order to give definitions of things.

To summarise, then, a language as a structured system may be characterised as follows:

1. Amid the disparate mass of facts involved in language, it stands out as a well defined entity. It can be localised in that particular section of the speech circuit where sound patterns are associated with concepts. It is the social part of language, external to the individual, who by himself is powerless either to create it or to modify it. It exists only in virtue of a kind of contract agreed between the members of a community. On the other hand, the individual needs an apprenticeship in order to acquaint himself with its workings: as a child, he assimilates it only gradually. It is quite separate from speech: a man who loses the ability to speak none the less retains his grasp of the language system, provided he understands the vocal signs he hears.

2. A language system, as distinct from speech, is an object that maybe studied independently. Dead languages are no longer spoken, but we can perfectly well acquaint ourselves with their linguistic structure. A science which studies linguistic structure is not only able to dispense with other elements of language, but is possible only if those other elements are kept separate.

[32]

3. While language in general is heterogeneous, a language system is homogeneous in nature. It is a system of signs in which the one essential is the union of sense and sound pattern, both parts of the sign being psychological.

4. Linguistic structure is no less real than speech, and no less amenable to study. Linguistic signs, although essentially psychological, are not abstractions. The associations, ratified by collective agreement, which go to make up the language are realities localised in the brain. Moreover, linguistic signs are, so to speak, tangible: writing can fix them in conventional images, whereas it would be impossible to photograph acts of speech in all their details. The utterance of a word, however small, involves an infinite number of muscular movements extremely difficult to examine and to represent. In linguistic structure, on the contrary, there is only the sound pattern, and this can be represented by one constant visual image. For if one leaves out of account that multitude of movements required to actualise it in speech, each sound pattern, as we shall see, is only the sum of a limited number of elements or speech sounds, and these can in turn be represented by a corresponding number of symbols in writing. Our ability to identify elements of linguistic structure in this way is what makes it possible for dictionaries and grammars to give us a faithful representation of a language. A language is a repository of sound patterns, and writing is their tangible form.

§3 Languages and their place in human affairs. Semiology

The above characteristics lead us to realise another, which is more important. A language, defined in this way from among the totality of facts of language, has a particular place in the realm of human affairs, whereas language does not.

[33]

A language, as we have just seen, is a social institution. But it is in various respects distinct from political, juridical and other institutions. Its special nature emerges when we bring into consideration a different order of facts.

A language is a system of signs expressing ideas, and hence comparable to writing, the deaf-and-dumb alphabet, symbolic rites, forms of politeness, military signals, and so on. It is simply the most important of such systems.

It is therefore possible to conceive of a science which studies the role of signs as part of social life. It would form part of social psychology, and hence of general psychology. We shall call it semiology1 (from the Greek sēmeîon, ‘sign’). It would investigate the nature of signs and the laws governing them. Since it does not yet exist, one cannot say for certain that it will exist. But it has a right to exist, a place ready for it in advance. Linguistics is only one branch of this general science. The laws which semiology will discover will be laws applicable in linguistics, and linguistics will thus be assigned to a clearly defined place in the field of human knowledge.

[34]

It is for the psychologist to determine the exact place of semiology.2 The linguist’s task is to define what makes languages a special type of system within the totality of semiological facts. The question will be taken up later on: here we shall make just one point, which is that if we have now for the first time succeeded in assigning linguistics its place among the sciences, that is because we have grouped it with semiology.

Why is it that semiology is not yet recognised as an autonomous science with its own object of study, like other sciences? The fact is that here we go round in a circle. On the one hand, nothing is more appropriate than the study of languages to bring out the nature of the semiological problem. But to formulate the problem suitably, it would be necessary to study what a language is in itself: whereas hitherto a language has usually been considered as a function of something else, from other points of view.

In the first place, there is the superficial view taken by the general public, which sees a language merely as a nomenclature (cf. p. [97]). This is a view which stifles any inquiry into the true nature of linguistic structure.

Then there is the viewpoint of the psychologist, who studies the mechanism of the sign in the individual. This is the most straightforward approach, but it takes us no further than individual execution. It does not even take us as far as the linguistic sign itself, which is social by nature.

Even when due recognition is given to the fact that the sign must be studied as a social phenomenon, attention is restricted to those features of languages which they share with institutions mainly established by voluntary decision. In this way, the investigation is diverted from its goal. It neglects those characteristics which belong only to semiological systems in general, and to languages in particular. For the sign always to some extent eludes control by the will, whether of the individual or of society: that is its essential nature, even though it may be by no means obvious at first sight.

So this characteristic emerges clearly only in languages, but its manifestations appear in features to which least attention is paid. All of which contributes to a failure to appreciate either the necessity or the particular utility of a science of semiology. As far as we are concerned, on the other hand, the linguistic problem is first and foremost semiological. All our proposals derive their rationale from this basic fact. If one wishes to discover the true nature of language systems, one must first consider what they have in common with all other systems of the same kind. Linguistic factors which at first seem central (for example, the workings of the vocal apparatus) must be relegated to a place of secondary importance if it is found that they merely differentiate languages from other such systems. In this way, light will be thrown not only upon the linguistic problem. By considering rites, customs, etc., as signs, it will be possible, we believe, to see them in a new perspective. The need will be felt to consider them as semiological phenomena and to explain them in terms of the laws of semiology.

[35]

Notes

1 Not to be confused with semantics, which studies changes of meaning. Saussure gave no detailed exposition of semantics, but the basic principle to be applied is stated on p.[109]. (Editorial note)

2 Cf. A. Naville, Classification des sciences, 2nd ed., p.104. (Editorial note)