[114]

Static Linguistics and Evolutionary Linguistics

§1 Internal duality of all sciences concerned with values

Very few linguists realise that the need to take account of the passage of time gives rise to special problems in linguistics and forces us to choose between two radically different approaches.

Most other sciences are not faced with this crucial choice. For them, what happens with the passage of time is of no particular significance. In astronomy, it is observed that in the course of time heavenly bodies undergo considerable changes. But astronomy has not on that account been obliged to split into two separate disciplines. Geology is constantly concerned with the reconstruction of chronological sequences. But when it concentrates on examining fixed states of the earth’s crust, that is not considered to be a quite separate object of study. There is a descriptive science of law and a history of law: but no one contrasts the one with the other. The political history of nations is intrinsically concerned with successions of events in time. None the less, when a historian describes the society of a particular period, one does not feel that this ceases to be history. The science of political institutions, on the other hand, is essentially descriptive: but occasionally it may deal with historical questions, and that in no way compromises its unity as a science.

Economics, by contrast, is a science which is forced to recognise this duality. Unlike the preceding cases, the study of political economy and of economic history constitute two clearly distinguishable disciplines belonging to one and the same science. Recent work in this field emphasises this distinction. Although it may not be fully realised, the distinction is required by an inner necessity of the subject. It is a necessity entirely analogous to that which obliges us to divide linguistics into two parts, each based upon a principle of its own. The reason is that, as in the study of political economy, one is dealing with the notion of value. In both cases, we have a system of equivalence between things belonging to different orders. In one case, work and wages; in the other case, signification and signal.

[115]

It is certain that all sciences would benefit from identifying more carefully the axes along which the things they are concerned with may be situated. In all cases, distinctions should be drawn on the following basis.

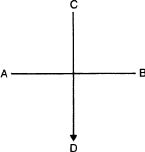

1. Axis of simultaneity (AB). This axis concerns relations between things which coexist, relations from which the passage of time is entirely excluded.

2. Axis of succession (CD). Along this axis one may consider only one thing at a time. But here we find all the things situated along the first axis, together with the changes they undergo.

For sciences which involve the study of values, this distinction becomes a practical necessity, and in certain cases is an absolute necessity. In this domain, it is impossible for scholars to organise their research in any rigorous fashion without taking account of these two axes. They are obliged to distinguish between the system of values considered in itself, and these same values considered over a period of time.

[116]

It is in linguistics that this distinction is least dispensable. For a language is a system of pure values, determined by nothing else apart from the temporary state of its constituent elements. Insofar as a value, in one of its aspects, is founded upon natural connexions between things (as, for example, in economics the value of a piece of land depends on the income derivable from it), it is possible up to a point to trace this value through time, bearing in mind that it depends at any one time upon the relevant system of contemporary values. However, its connexion with things inevitably supplies it with a natural basis, and hence any assessment of it is never entirely arbitrary. There are limits upon the range of variability. But, as we have already seen, in linguistics these natural connexions have no place.

It should be added that the more complex and rigorously organised a system of values is, the more essential it becomes, on account of this very complexity, to study it separately in terms of the two axes. Of no system is this as true as it is of a language. Nowhere else do we find comparable precision of values, or such a large number and diversity of terms involved, or such a strict mutual dependence between them. The multiplicity of signs, which we have already invoked to explain linguistic continuity, precludes absolutely any attempt to study simultaneously relations in time and relations within the system.

That is why we must distinguish two branches of linguistics. What should they be called? The terms available are not all equally appropriate to indicate the distinction in question. ‘History’ and ‘historical linguistics’ cannot be used, for the ideas associated with them are too vague. Just as political history includes the description of periods as well as the narration of events, it might be supposed by describing a sequence of states of a language one was studying the language along the temporal axis. But in order to do that, it would be necessary to consider separately the factors of transition involved in passing from one linguistic state to the next. The terms evolution and evolutionary linguistics are more exact, and we shall make frequent use of these terms. By contrast, one may speak of the science of linguistic states, or static linguistics.

[117]

But in order to mark this contrast more effectively, and the intersection of two orders of phenomena relating to the same object of study, we shall speak for preference of synchronic linguistics and diachronic linguistics. Everything is synchronic which relates to the static aspect of our science, and diachronic everything which concerns evolution. Likewise synchrony and diachrony will designate respectively a linguistic state and a phase of evolution.

§2 Internal duality and the history of linguistics

The first thing which strikes one on studying linguistic facts is that the language user is unaware of their succession in time: he is dealing with a state. Hence the linguist who wishes to understand this state must rule out of consideration everything which brought that state about, and pay no attention to diachrony. Only by suppressing the past can he enter into the state of mind of the language user. The intervention of history can only distort his judgment. It would be absurd to try to draw a panorama of the Alps as seen from a number of peaks in the Jura simultaneously. A panorama must be taken from just one point. The same is true of a language. One cannot describe it or establish its norms of usage except by taking up a position in relation to a given state. When the linguist follows the evolution of the language, he is like the observer moving from one end of the Jura to the other in order to record changes in perspective.

[118]

Since its beginnings, it would be true to say that modem linguistics has been entirely taken up with diachronic study. The comparative grammar of the Indo-European languages uses the facts it has available in order to reconstruct hypothetically an earlier type of language. Comparison is only a means for resurrecting the past. The method is the same in the study of particular linguistic sub-groups (the Romance languages, Germanic languages, etc.). Linguistic states are considered only in fragments and very imperfectly. This was the approach inaugurated by Bopp, and the conception of a language it offers is hybrid and uncertain.

But what was the method followed by those who studied languages before the foundation of linguistics? How did the traditional ‘grammarians’ proceed? It is a curious fact that on this particular point their approach was quite flawless. Their writings show us clearly that they were concerned with the description of linguistic states. Their programme was a strictly synchronic one. The grammar of Port Royal, for instance, attempts to describe the state of the French language under Louis XIV and to set out the relevant system of values. For this purpose, it has no need to make reference to the French of the Middle Ages; it keeps strictly to the horizontal axis (cf. p. [115]) and never departs from it. Its method is thus perfectly correct. That is not to say, however, that the application of the method is perfect. Traditional grammar pays no attention to whole areas of linguistic structure, such as word formation. It is normative grammar, concerned with laying down rules instead of observing facts. It makes no attempt at syntheses. Often, it even fails to distinguish between the written word and the spoken word. And so on.

Traditional grammar has been criticised for not being scientific. None the less, its basis is less objectionable and its object of study better defined than is the case for the kind of linguistics inaugurated by Bopp. The latter attempts to cover an inadequately defined area, never knowing exactly where it is going. It has a foot in each camp, having failed to distinguish clearly between states and sequences.

[119]

Having paid too much attention to history, linguistics will go back now to the static viewpoint of traditional grammar, but in a new spirit and with different methods. The historical approach will have contributed to this rejuvenation. It will have been instrumental in facilitating a better grasp of linguistic states. The old grammar saw no further than synchronic facts. Linguistics has made us aware of a different order of phenomena. But that is not enough. The opposition between these two orders must be grasped in order to draw out all the consequences which it implies.

§3 Examples of internal duality

The contrast between the two points of view – synchronic and diachronic – is absolute and admits no compromise. A few examples will illustrate what this difference consists in, and why it is irreducible.

The Latin word crispus (‘wavy, curly’) supplied French with a stem crép-, on which are based the verbs crépir (‘to rough-render’) and décrépir (‘to strip the plaster from’). Then French at a certain stage borrowed from Latin the word dēcrepitus (‘worn by age’). This became in French décrépit, and its etymology was forgotten. Nowadays, it is certain that most speakers connect un mur décrépi (‘a dilapidated wall’) and un homme décrépit (‘a decrepit man’), although historically the two words have nothing to do with each other. People often speak of the façade décrépite (‘dilapidated façade’) of a house. That is a static fact, because it involves a relationship between two terms coexisting in the language. But in order to bring it about, certain evolutionary changes had to coincide. The original crisp- had to come to be pronounced crép-, and at the right moment a new word had to be borrowed from Latin. These diachronic facts, it is clear, have no connexion with the static fact which they brought about. They are of quite a different order.

[120]

Another example with quite general implications is the following. In Old High German, the plural of gast (‘guest’) was originally gasti, the plural of hant (‘hand’) was hanti, and so on. Subsequently, this -i produced an umlaut; that is to say, it had an effect upon the vowel of the preceding syllable, changing a into e. So gasti became gesti, and hanti became henti. Then this -i weakened, giving geste, etc. Today as a result we have Gast with a plural Gäste, Hand with a plural Hände, and so on for a whole class of words. Something similar happened in Anglo-Saxon, where originally fōt (‘foot’) had a plural *fōti, toþ (‘tooth’) had a plural *toþi, gōs (‘goose’) had a plural gōsi, etc. A first phonetic change gave rise to an umlaut, so that *fōti became *fēti; and then as the result of a second phonetic change, the fall of the final i, *fēti became fēt. Thus fōt then had a plural fēt, tōþ a plural tēþ, gōs a plural gēs (Modern English foot: feet, tooth: teeth, goose: geese).

Previously, at the stage gast : gasti, fōt : fōti, the plural had been marked simply by adding an -i. But Gast : Gäste and fōt : fēt show a new way of marking the plural. The mechanism is not the same in the two cases, since in Old English there is simply a contrast of vowels, whereas in German there is in addition the presence or absence of a final -e. But this difference does not affect the example.

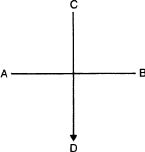

The relation between singular and plural at any given time, irrespective of the actual forms, can be represented along a horizontal axis:

The developments, whatever they may have been, which gave rise to changes in the forms, can be represented along a vertical axis. So we have a complete figure as follows:

[121]

This type of case suggests a number of observations which are very relevant to the present discussion.

1. The diachronic developments are in no way directed towards providing a new sign to mark a given value. The fact that gasti changed to gesti and then to geste (Gäste) has nothing to do with the plurals of nouns. In tragit→trägt we see the same umlaut affecting the flexion of a verb. So the reason for a diachronic development lies in the development itself. The particular synchronic consequences which may ensue have nothing to do with it.

2. These diachronic events do not even tend to change the system. There was no intention to replace one system of relations by another. The change affected not the organisation as such, but merely the particular items involved.

This illustrates a principle already stated earlier: the language system as such is never directly altered. It is in itself unchangeable. Only certain elements change, but without regard to the connexions which integrate them as part of the whole. It is as if one of the planets circling the sun underwent a change of dimensions and weight: this isolated event would have general consequences for the whole solar system, and disturb its equilibrium. In order to mark pluralisation, a contrast between two terms is required: fōt vs. *fōti or fōt vs. fēt are equally viable for this purpose. Substituting one for the other leaves the distinction itself untouched. It is not the system as a whole which has been changed, nor one system which has engendered a second. All that happened was the one element in the original system changed, and that sufficed to bring a new system into being.

3. Once we see this, we can better appreciate the fact that a linguistic state always has a fortuitous character. Languages are notmechanisms created and organised with a view to the concepts to be expressed, although people are mistakenly inclined to think so. On the contrary, our example shows that the state which resulted from the change was in no way destined to express the meanings it took on. A fortuitous state is given (fōt : fēt), and this is pressed into service to mark the distinction between singular and plural: but fōt vs. fēt is no better designed for that purpose than fōt vs. *fōti. At each stage, spirit is breathed into the matter given, and brings it to life. This view, inspired by historical linguistics, is unknown to traditional grammar, which would never have come to it by the traditional methods. It is a view equally foreign to most philosophers of language: and yet it is of the greatest philosophical significance.

[122]

4. Are the facts belonging to the diachronic series at least of the same order as those of the synchronic series? In no way. For the changes brought about, as we have already observed, are entirely unintentional. Whereas a synchronic fact is always significant, being based always upon two coexisting terms. It is not Gäste which expresses the plural, but the opposition Gast vs. Gäste. With a diachronic fact, just the opposite is true. It involves one term only. If a new term (Gäste) is to appear, the old term (gasti) must make way for it.

Any notion of bringing together under the same discipline facts of such disparate nature would be mere fantasy. In the diachronic perspective one is dealing with phenomena which have no connexion with linguistic systems, even though the systems are affected by them.

Other examples which may be adduced to corroborate and amplify the conclusions drawn from those already cited include the following.

In French, the stress falls always on the final syllable, unless it contains a mute e (ə). This is a synchronic fact, a relationship between the whole French vocabulary and stress. Where does it come from? From an antecedent linguistic state. Latin had a different and more complex system of stress, in which stress fell upon the penultimate syllable if that syllable were long, but otherwise upon the antipenultimate (e.g.  ). This rule involves factors which have no parallel at all in the case of French. None the less, it is the same stress we are dealing with, in the sense that it still falls in the same place. In a French word, the stress falls always on the same syllable which bore the stress in Latin. Thus amīcum becomes French amí, and ánimam becomes

). This rule involves factors which have no parallel at all in the case of French. None the less, it is the same stress we are dealing with, in the sense that it still falls in the same place. In a French word, the stress falls always on the same syllable which bore the stress in Latin. Thus amīcum becomes French amí, and ánimam becomes  me. However, the Latin and French stress patterns are different because the forms of the words have changed. In French words, vowels following the stressed syllable have either disappeared or been reduced to a mute e. As a consequence of these changes, the position of stress in the word was no longer the same. From that point on French speakers, aware of the new situation, instinctively placed stress on the final syllable, even in the case of foreign words originally borrowed in written form (facile, consul, ticket, burgrave, etc.). It is evident that there was no intention to change the system or apply a new rule, since in a case like

me. However, the Latin and French stress patterns are different because the forms of the words have changed. In French words, vowels following the stressed syllable have either disappeared or been reduced to a mute e. As a consequence of these changes, the position of stress in the word was no longer the same. From that point on French speakers, aware of the new situation, instinctively placed stress on the final syllable, even in the case of foreign words originally borrowed in written form (facile, consul, ticket, burgrave, etc.). It is evident that there was no intention to change the system or apply a new rule, since in a case like  the stress remains throughout on the same syllable. But a diachronic fact intervened. The place of the stress changed without anyone moving it. A stress law, like everything else in a linguistic system, is an arrangement of elements, the fortuitous and involuntary outcome of evolution.

the stress remains throughout on the same syllable. But a diachronic fact intervened. The place of the stress changed without anyone moving it. A stress law, like everything else in a linguistic system, is an arrangement of elements, the fortuitous and involuntary outcome of evolution.

[123]

An even more striking example is this. In early Slavonic, slovo (‘word’) had an instrumental case  in the singular, a nominative plural slova, and a genitive plural

in the singular, a nominative plural slova, and a genitive plural  . It was a declension in which each case had its own ending. But today the ‘weak’ vowels

. It was a declension in which each case had its own ending. But today the ‘weak’ vowels  and

and  , which were the Slavic representatives of Proto-Indo-European ĭ and ŭ, have disappeared. So in Czech, for example, we have slovo, slovem, slova, slov. Likewise žena (‘woman’) has an accusative singular ženu, a nominative plural ženy, and a genitive plural žen. Here we see that the genitive ending (slov, žen) is zero. So it is not even necessary to have any material sign in order to give expression to an idea: the language may be content simply to contrast something with nothing. In this particular example, we can recognize the genitive plural žen simply by the fact that it is neither žena, nor ženu, nor any of the other forms of the declension. At first sight it seems strange that such a specific notion as that of genitive plural should have acquired the sign zero. But that is precisely what demonstrates that it is purely a matter of chance. Languages are mechanisms which go on functioning, in spite of the damage caused to them.

, which were the Slavic representatives of Proto-Indo-European ĭ and ŭ, have disappeared. So in Czech, for example, we have slovo, slovem, slova, slov. Likewise žena (‘woman’) has an accusative singular ženu, a nominative plural ženy, and a genitive plural žen. Here we see that the genitive ending (slov, žen) is zero. So it is not even necessary to have any material sign in order to give expression to an idea: the language may be content simply to contrast something with nothing. In this particular example, we can recognize the genitive plural žen simply by the fact that it is neither žena, nor ženu, nor any of the other forms of the declension. At first sight it seems strange that such a specific notion as that of genitive plural should have acquired the sign zero. But that is precisely what demonstrates that it is purely a matter of chance. Languages are mechanisms which go on functioning, in spite of the damage caused to them.

[124]

All this confirms the principles already formulated above, which may be summed up as follows.

A language is a system of which all the parts can and must be considered as synchronically interdependent.

Since changes are never made to the system as a whole, but only to its individual elements, they must be studied independently of the system. It is true that every change has a repercussion on the system. But initially only one point is affected. The change is unrelated to the internal consequences which may follow for the system as a whole. This difference in nature between chronological succession and simultaneous coexistence, between facts affecting parts and facts affecting the whole, makes it impossible to include both as subject matter of one and the same science.

§4 Difference between the two orders illustrated by comparisons

In order to clarify at the same time the autonomy and interdependence of the synchronic and diachronic approaches, it is useful to compare synchrony to the projection of a three-dimensional object on a two-dimensional plan. Any projection depends directly upon the object projected, but none the less differs from it. The projection is something apart. Otherwise there would be no need for a whole science of projection: it would be enough to consider the objects themselves. In linguistics, we find the same relation between historical reality and a linguistic state. The latter is a projection of the former at one given moment. Studying objects, that is to say diachronic events, will give us no insight into synchronic states, any more than we can hope to understand geometrical projections simply by studying, however thoroughly, different kinds of object.

[125]

If we cut crosswise through the stem of a plant, we can observe a rather complex pattern on the surface revealed by the cut. What we are looking at is a section of the plant’s longitudinal fibres. These fibres will be revealed if we now make a second cut perpendicular to the first. Again in this example, one perspective depends on the other. The longitudinal section shows us the fibres themselves which make up the plant, while the transversal section shows us their arrangement on one particular level. But the transversal section is distinct from the longitudinal section, for it shows us certain relations between the fibres which are not apparent at all from any longitudinal section.

But of all the comparisons one might think of, the most revealing is the likeness between what happens in a language and what happens in a game of chess. In both cases, we are dealing with a system of values and with modifications of the system. A game of chess is like an artificial form of what languages present in a natural form.

Let us examine the case more closely.

In the first place, a state of the board in chess corresponds exactly to a state of the language. The value of the chess pieces depends on their position upon the chess board, just as in the language each term has its value through its contrast with all the other terms.

[126]

Secondly, the system is only ever a temporary one. It varies from one position to the next. It is true that the values also depend ultimately upon one invariable set of conventions, the rules of the game, which exist before the beginning of the game and remain in force after each move. These rules, fixed once and for all, also exist in the linguistic case: they are the unchanging principles of semiology.

Finally, in order to pass from one stable position to another or, in our terminology, from one synchronic state to another, moving one piece is all that is needed. There is no general upheaval. That is the counterpart of the diachronic fact and all its characteristic features. For in the case of chess:

(a) One piece only is moved at a time. Similarly, linguistic changes affect isolated elements only.

(b) In spite of that, the move has a repercussion upon the whole system. It is impossible for the player to foresee exactly where its consequences will end. The changes in values which result may be, in any particular circumstance, negligible, or very serious, or of moderate importance. One move may be a turning point in the whole game, and have consequences even for the pieces which are not for the moment involved. As we have just seen, it is exactly the same where a language is concerned.

(c) Moving a piece is something entirely different from the preceding state of the board and also from the state of the board which results. The change which has taken place belongs to neither. The states alone are important.

In a game of chess, any given state of the board is totally independent of any previous state of the board. It does not matter at all whether the state in question has been reached by one sequence of moves or another sequence. Anyone who has followed the whole game has not the least advantage over a passer-by who happens to look at the game at that particular moment. In order to describe the position on the board, it is quite useless to refer to what happened ten seconds ago. All this applies equally to a language, and confirms the radical distinction between diachronic and synchronic. Speech operates only upon a given linguistic state, and the changes which supervene between one state and another have no place in either.

[127]

There is only one respect in which the comparison is defective. In chess, the player intends to make his moves and to have some effect upon the system. In a language, on the contrary, there is no premeditation. Its pieces are moved, or rather modified, spontaneously and fortuitously. The umlaut of Hände for hanti, of Gaste for gasti (cf. p. [120]) produced a new plural formation, but also produced at the same time a verb form like trägt for tragit, etc. If the game of chess were to be like the operations of a language in every respect, we would have to imagine a player who was either unaware of what he was doing or unintelligent. This sole difference, moreover, makes the comparison even more instructive, by showing the absolute necessity for distinguishing in linguistics between the two orders of phenomena. For if diachronic facts cannot be reduced to the synchronic system they affect, even when a change of this kind is made deliberately, this will be the case even less when blind forces of change disturb the organisation of a system of signs.

§5 Synchronic and diachronic linguistics: Their methods and principles contrasted

Diachronic and synchronic studies contrast in every way.

For example, to begin with the most obvious fact, they are not of equal importance. It is clear that the synchronic point of view takes precedence over the diachronic, since for the community of language users that is the one and only reality (cf. p. [117]). The same is true for the linguist. If he takes a diachronic point of view, he is no longer examining the language, but a series of events which modify it. It is often claimed that there is nothing more important than knowing how a given state originated. In a certain sense, that is true. The conditions which gave rise to the state throw light upon its true nature and prevent us from entertaining certain misconceptions (cf. p. [121] ff.). But what that proves is that diachrony has no end in itself. One might say, as has been said of journalism as a career, that it leads nowhere until you leave it behind.

[128]

Their methods are also different in two respects:

(a) Synchrony has only one perspective, that of the language users; and its whole method consists of collecting evidence from them. In order to determine to what extent something is a reality, it is necessary and also sufficient to find out to what extent it exists as far as the language users are concerned. Diachronic linguistics, however, needs to distinguish two perspectives. One will be prospective, following the course of time, and the other retrospective, going in the opposite direction. It follows that two diachronic methods are required, and these will be discussed later in Part V.

(b) A second difference derives from the different areas covered by the two disciplines. The object of synchronic study does not comprise everything which is simultaneous, but only the set of facts corresponding to any particular language. In this, it will take into account where necessary a division into dialects and sub-dialects. The term synchronic, in fact, is not sufficiently precise. Idiosynchronic would be a better term, even though it is somewhat cumbersome. Diachronic linguistics, on the contrary, needs no such particularisation, and indeed rejects it. The items diachronic linguistics deals with do not necessarily belong to a single language. (Compare Proto-Indo-European *esti, Greek ésti, German ist, French est.) It is precisely the succession of diachronic facts and their proliferation in space which gives rise to the diversity of languages. In order to justify comparing two forms, it is sufficient that there should be some historical connexion between them, however indirect.

[129]

These are not the most striking contrasts, nor the most profound. The consequences of the radical difference between facts of evolution and static facts is that all notions pertinent to the former and all notions pertinent to the latter are mutually irreducible. Any of the notions in question may be used to demonstrate this truth. No synchronic phenomenon has anything in common with any diachronic phenomenon (cf. p. [122]). One is a relationship between simultaneous elements, and the other a substitution of one element for another in time, that is to say an event. We shall also see (p. [150]) that diachronic identities and synchronic identities are two very different things. Historically, the French negative particle pas is the same as the noun pas (‘pace’), whereas in modern French these two units are entirely separate. Realising these facts should be sufficient to bring home the necessity of not confusing the two points of view. But nowhere is this necessity more evident than in the distinction we are about to draw.

§6 Synchronic laws and diachronic laws

There is a great deal of talk nowadays about laws in linguistics. But are linguistic facts really governed by laws? And if so, of what kind can these laws be? A language being a social institution, one might a priori think it is governed by prescriptions of the kind which regulate communities. Now any social law has two fundamental characteristics: it is imperative and it is general. It demands compliance, and it covers all cases, within certain limits of time and place, of course.

[130]

Do the laws which govern a language answer to this definition? Once again, to find out we must first distinguish between synchrony and diachrony. For the two cases are not to be conflated. To speak of a ‘linguistic law’ in general is like trying to lay hands on a ghost.

The following are examples from Greek, in which ‘laws’ of a synchronic and diachronic nature have been deliberately intermingled.

1. Proto-Indo-European voiced aspirates became voiceless aspirates, e.g. *dhūmos → thūmós (‘breath of life’), *bherō → phérō (‘I carry’)

2. Stress never falls on a syllable preceding the antepenultimate syllable of a word.

3. All words end either in a vowel or in -s, -n, -r; but no other consonant.

4. Initial s before a vowel became h (denoted by the ‘rough breathing’ mark), e.g. *septm (Latin septem) → heptá.

5. Final -m became -n, e.g. *jugom → zugón (cf. Latin jugum).1

6. Final stops fall, e.g. *gunaik → gúnai, *epheret → éphere,*epheront → épheron.

In the above examples, Law 1 is diachronic: it states that what had been dh becomes th, etc. Law 2 states a relationship between word-unit and stress: it is a kind of contract between two coexisting terms: it is thus a synchronic law. Law 3 is the same, since it concerns the word-unit and its final sound. Laws 4, 5 and 6 are diachronic: they state, respectively, that what had been s became h, that -n replaced -m, and that -t, -k, etc. disappeared without trace.

[131]

It should also be noted that Law 3 is the result of Laws 5 and 6. Two diachronic facts created a synchronic fact.

Once the two categories of laws are distinguished, one sees that Laws 2 and 3 are not of the same nature as Laws 1, 4, 5 and 6.

Synchronic laws are general, but not imperative. It is true that a synchronic law is imposed upon speakers by the constraints of communal usage (cf. p. [107]). But we are not envisaging here an obligation relative to the language users. What we mean is that in the language there is nothing which guarantees the maintenance of regularity on any given point. A synchronic law simply expresses an existing order. It registers a state of affairs. What it states is of the same order as a statement to the effect that in a certain orchard the trees are planted in the form of a quincunx. The order a synchronic law defines is precarious, precisely because it is not imperative. Nothing could be more regular than the synchronic law governing stress in Latin (a law exactly comparable to Law 2 above). This system of stress, none the less, offered no resistance to factors of change, and eventually gave place to a new law, which we find in French (cf. p. [122] ff.). In short, when one speaks of a synchronic law, one is speaking of an arrangement, or a principle of regularity.

Diachrony, on the other hand, presupposes a dynamic factor through which an effect is produced, a development carried out. But this imperative character does not justify applying the notion of law to facts of evolution. One speaks of a law only when a set of facts is governed by the same rule. In spite of appearances to the contrary, diachronic events are always accidental and particular in nature.

[132]

This is quite obvious in the case of semantic facts. For example, the French word poutre, meaning ‘mare’, took on the meaning of ‘beam, rafter’. The change can be explained by reference to particular circumstances, and has no connexion with other changes that may have occurred at the same time. It is merely one accident among many recorded in the history of a language.

As regards syntactic and morphological changes, at first sight this is not so clear. At a certain period, for instance, nearly all the forms of the Old French nominative case disappeared. Is this not an example of a whole set of facts governed by the same law? No. For all these are merely multiple examples of a single isolated fact. It was the notion of a nominative case itself which was affected, and the disappearance of that case naturally involved the disappearance of a whole set of forms.1 For anyone who looks only at the language from the outside, the single phenomenon is obscured by the multiplicity of its manifestations. But the phenomenon itself is one in its underlying nature, and it constitutes a historical event as isolated of its kind as the semantic change of the word poutre. It only appears to be a law because it is actualised in a system. It is the rigorous organisation of the system which creates the illusion that the diachronic fact is subject to the same conditions as the synchronic.

Exactly the same applies to phonetic changes, even though people nowadays speak of ‘phonetic laws’. It is indeed observable that at a given time in a given region, all the words which have a certain phonetic feature are subject to the same change. For example, Law 1 on p. [130] (*dhūmos – Greek thūmós) applies to all Greek words with a voiced aspirate (cf. *nebhos → néphos, *medhu → méthu, *anghō → ánkhō, etc.). Law 4 (*septm → heptá) applies to *serpō → hérpō, *sūs → hûs, and all words beginning with s. This regularity, which has sometimes been disputed, is in our view very well established: the apparent exceptions do not diminish the ineluctability of changes of this kind, for they are to be explained either by more specialised phonetic laws (e.g. tríkhes : thriksí, cf. p. [138]), or else by the intervention of facts of a different order (analogy, etc.). So it would appear that nothing could better fit the definition of the term law given above. And yet, however many cases confirm a phonetic law, all the facts it covers are simply manifestations of a single particular fact.

[133]

The real question is whether phonetic changes affect words or only sounds. The answer is not in doubt. In néphos, méthu, ánkhō, etc. it is a particular sound; a Proto-Indo-European voiced aspirate which becomes a voiceless aspirate, the initial s of early Greek which changes to h, and so on. Each of these facts is an isolated fact. It is independent of other events of the same order, and also independent of the words in which it occurs.1 All the words in question, naturally, are modified phonetically; but that must not mislead us as to the real nature of what is taking place.

On what do we base the claim that words themselves are not directly subject to phonetic change? On the simple observation that sound changes do not affect words as such, and cannot alter them essentially. The word as a unit is not made up simply of a set of sounds:1 it depends on other characteristics than its material nature. Imagine that one note on a piano is out of tune. Every time this note is played in the performance of a piece, there will be a false note. But where? In the melody? Surely not. Nothing has happened to the melody, only to the piano. It is exactly the same in the case of sound change. The sound system is the instrument we play in order to articulate the words of the language. If one element in the sound system changes, this may have various results; but in itself, the fact does not affect the words, for they are, so to speak, the melodies in our repertoire.

[134]

Thus diachronic facts are individual facts. The alteration of a system takes place through events which not only lie outside it (cf. p. [121]), but are isolated events and form no system among themselves.2

To summarise, synchronic facts of whatever kind present a certain regularity, but they have no imperative character. Diachronic facts, on the contrary, are forced upon the language, but there is nothing general about them.

In short, we conclude that neither synchronic nor diachronic facts are governed by laws in the sense defined above. If, none the less, one insists on speaking of linguistic laws, the term will mean something entirely different as applied to synchronic facts and to diachronic facts.

§7 Is there a panchronic point of view?

Hitherto, we have taken the term law in its legal sense. But might there perhaps be in languages laws as understood in the physical and natural sciences? In other words, relations which hold in all cases and for ever? In short, is it not possible to study languages from a panchronic point of view?

It is possible, no doubt. Since phonetic changes occur, and will always occur, one may consider that general phenomenon in itself as one of the constant features of language: hence it is a linguistic law. In linguistics as in chess (cf. p. [125] ff.) there are rules which outlast all events. But they are general principles existing independently of concrete facts. As soon as one comes down to particular, tangible facts, there is no panchronic point of view. Every phonetic change, whatever its extension may be, is limited to a certain period and a certain geographical area. There is no such change which occurs all the time and everywhere. Its existence is merely diachronic. That very fact is a criterion for judging what belongs to linguistic structure and what does not. Any concrete fact amenable to panchronic explanation could not be part of linguistic structure. Take the French word chose (‘thing’). From a diachronic point of view, it is to be distinguished from Latin causa, from which it is derived. From a synchronic point of view, it is to be distinguished from all the words it might be associated with in modern French. Only the sounds of the word considered in themselves (šọz) may be considered panchronically: but they are devoid of linguistic value. Even from a panchronic point of view, šọz as part of a sequence like un šọz admirablə (une chose admirable ‘an admirable thing’) is not a unit. It is just a formless mass, which lacks definition. Why pick out šọz, rather than ọza or nšọ? There is no value, because there is no meaning. The panchronic point of view never gets to grips with specific facts of language structure.

[135]

§8 Consequences of the confusion of synchrony with diachrony

There are two cases to consider.

(a) The synchronic facts appear to conflict with the diachronic facts. Looking at the case superficially, it appears that we have to choose between the two. In fact, this is not necessary. One does not exclude the other. For instance, the word dépit in French used to mean ‘scorn’; but that does not prevent it nowadays having a quite different meaning. Etymology and synchronic value are two separate things. Similarly, in modern French, according to traditional grammar, the present participle is sometimes variable and behaves like an adjective, agreeing with its noun (une eau courante, ‘running water’), but is in other cases invariable (une personne courant dans la rue, ‘a person running in the street’). But historical grammar shows us that we are not dealing with one and the same form. In one case there is the continuation of the Latin participle (currentem), which is variable; but in the other case we are dealing with a survival of the Latin ablative gerund (currendō), which is invariable.1 Do the synchronic facts contradict the diachronic facts in this case? Is traditional grammar to be condemned in the name of historical grammar? No. That would be to see only one side of the reality. One must not suppose that historical facts are the only important ones, or that they suffice to constitute a language. It is undoubtedly true that, as far as its origins are concerned, the modern French participle courant subsumes two originally separate forms. But as language users we no longer distinguish two forms: we recognise only one.2 Both facts are equally absolute and incontestable.

[136]

(b) The synchronic facts agree so closely with the diachronic facts that they are confused, or it is considered superfluous to distinguish them. For instance, the present meaning of the French word père (‘father’) is explained by appeal to the fact that its Latin etymon pater meant ‘father’. To take another example, Latin short a in a non-initial open syllable became i: so beside faciō one has conficiō, beside amı-cus one has inimı-cus, etc. The law is often stated as being that the a of faciō (‘l make’) changes to i in conficiō (‘I make ready, complete’) because it is no longer in the initial syllable. This is incorrect. The a of faciō never ‘became’ the i of conficio. In order to establish the truth of the matter, one must distinguish between two periods and four different forms. Originally, the forms were faciō and confaciō. Then confaciō became conficiō, while faciō stayed as it was: so the forms in use were faciō – conficiō.

[137]

If a ‘change’ occurred, it was that confaciō changed to conficiō. But the rule, badly formulated as it is, does not even mention confaciō. Furthermore, in addition to this change, which is a diachronic fact, there is a second fact which is quite different. It concerns the purely synchronic contrast between faciō and conficiō. One may be tempted to regard this not as a separate fact, but as a consequence of the first. None the less, it is a fact in its own right; and indeed all synchronic facts are of this kind. What prevents our recognising the proper value of the contrast faciō – conficiō is that its role is not particularly important. But when we consider pairs like German Gast – Gäste, gebe – gibt, we realise that these contrasts too are fortuitous results of phonetic evolution: they none the less embody, synchronically, quite essential grammatical distinctions. Since synchronic and diachronic facts are closely connected in other respects, each presupposing the other, in the end distinguishing between them is felt to be pointless. For years, linguistics has muddled them up without even noticing the muddle.

This mistake becomes very apparent, however, in certain cases. In order to explain Greek phuktós, it might be supposed that it is sufficient to point out that in Greek g and kh become k before a voiceless consonant, and to state this fact in terms of synchronic correspondences such as phugeîn : phuktós, lékhos : léktron, etc. But then we come up against cases like tríkhes : thriksí, where a complication appears in the form of a ‘change’ from t to th. The forms of this word can be explained only in historical terms, by appeal to relative chronology. The primitive stem *thrikh, followed by the ending -si, gave thriksí. This was a very early development, like that which produced léktron from the root lekh-. At a later stage, any aspirate followed by another in the same word lost its aspiration, and so *thríkhes became tríkhes, while thriksí naturally remained unaffected by this development.

[138]

Linguistics is thus faced with a second parting of the ways. In the first place, we found it necessary to choose between studying languages and studying speech (cf. p. [36]). Now we find ourselves at the junction where one road leads to diachrony and the other to synchrony.

Once this dual principle of classification is grasped, one may add that everything which is diachronic in languages is only so through speech. Speech contains the seeds of every change, each one being pioneered in the first instance by a certain number of individuals before entering into general usage. Modern German has ich war, wir waren, whereas at an earlier period, up to the sixteenth century, the conjugation was ich was, wir waren (English still has I was, we were). How did this substitution of war for was come about? A few people, on the basis of waren, created the analogical form war. This form, constantly repeated and accepted by the community, became part of the language. But not all innovations in speech meet with the same success. As long as they are confined to certain individuals, there is no need to take them into account, since our concern is solely with the language. They enter our field of observation only when they have become accepted by the community.

An evolutionary development is always preceded by a similar development, or rather many similar developments, in the sphere of speech. That in no way invalidates the distinction established previously: rather, it offers a confirmation. For in the history of any innovation one always finds two distinct phases: (1) its appearance in individual cases, and (2) its incorporation into the language in exactly the same form, but now adopted by the community.

[139]

The following table indicates a rational structure for the pursuit of linguistic studies:

It must be conceded that the theoretically ideal form a science should take is not always the form imposed upon it by practical necessities. In linguistics, practical necessities are more demanding than in any other subject. To some extent, the confusion which at present reigns in linguistic research is due to them. Even if the distinctions drawn here were accepted once and for all, it might not be possible in practice to translate this ideal schema into a systematic programme of studies.

In the synchronic study of Old French, the linguist uses facts and principles which have nothing in common with those which would be revealed by the history of the same language from the thirteenth to the twentieth century, but are comparable to those which would emerge from the description of a modern Bantu language, or Attic Greek in 400 B.C., or French at the present day. These different synchronic investigations are concerned with similar relations: for although each language constitutes a closed system, all presuppose certain constant principles. These do not vary from one case to the next, because the facts studied belong to the same order of phenomena. In the case of historical studies, it is no different. Whether one is studying the development of French over a certain period (from the thirteenth to the twentieth century, for example), or a period in the history of Javanese, or of any other language, one is dealing with similar facts. Comparing these facts is sufficient to enable one to establish valid diachronic generalisations. The ideal programme would be for each scholar to concentrate either on synchronic or on diachronic research, and include as much as possible of the material falling within his chosen field. But it is difficult to achieve a scientific understanding of widely differing languages. Furthermore, each language in practice constitutes a single unit for purposes of study, and one is led inevitably to study it from both a static and a historical viewpoint in turn. Such units, we must none the less remember, are merely superficial in theoretical terms. On the contrary, the disparity between different languages conceals an underlying unity. In studying a language from either point of view, it is of the utmost importance to assign each fact to its appropriate sphere, and not to confuse the two methods.

[140]

The two branches of linguistics thus defined will now be considered in turn.

Synchronic linguistics will be concerned with logical and psychological connexions between coexisting items constituting a system, as perceived by the same collective consciousness.

Diachronic linguistics on the other hand will be concerned with connexions between sequences of items not perceived by the same collective consciousness, which replace one another without themselves constituting a system.

Notes

1According to Meillet (Mem. de la Société de Linguistique, IX, p. 365 ff.) and Gauthiot (La fin de mot en indo-européen, p. 158 ff.) Proto-Indo-European had only final -n and not -m. If this is accepted, law 5 becomes: ‘Final -n is maintained’. Its value as an example is unchanged, since the phonetic conservation of an earlier state of affairs is not different in nature from the phonetic alteration of an earlier state of affairs. Cf. p. [200]. (Editorial note)

1It is not altogether clear how this explanation is to be reconciled with the claims that a language system itself is never changed as such (p. (124)) and that case distinctions belong among the abstract entities of grammar (p. [189] ff.). (Translator’s note)

1It need hardly be said that the examples cited are merely an indication. Currently, linguistics attempts – rightly – to relate as many series of changes as possible to the operation of the same initial principle. Meillet, for example, explains all changes in Greek stops as due to a gradual weakening of articulation (Mem. de la Société de Linguistique, IX, p. 163 ff.). Where such general facts are to be found it is to them, in the final analysis, that the conclusions concerning the nature of phonetic change apply. (Editorial note)

1But elsewhere (p. [98]) it is denied that a word consists of sounds at all. If that is the case, there is no need to justify the claim that words are not subject to sound change, since it is true by definition. If, on the other hand, the signal is treated as a fixed set of sound units, corresponding to the sequence of letters in a written form (p. [32]), it is less obvious that sound change does not affect the sound pattern of a word directly. There is some inconsistency here, which Saussure’s editors cannot be said to have resolved satisfactorily. (Translator’s note)

2The thesis that a system as such does not evolve, but is merely affected by unrelated external developments, subsequently became one of the major subjects of controversy among structuralists. (Translator’s note)

1This theory, although generally accepted, has recently been challenged by E. Lerch (Das invariable Participium praesentis, Erlangen, 1913), but unsuccessfully in our view. The example has therefore been allowed to stand. In any case, its didactic value would be unimpaired. (Editorial note)

2The example is not entirely convincing. For semantically, and on the basis of both syntagmatic and associative relations, there seem to be adequate grounds for distinguishing the variable courant from its invariable counterpart in modern French, without any appeal to diachronic considerations. (Translator’s note)