Syntagmatic Relations and Associative Relations

In a linguistic state, then, everything depends on relations. How do they work?

The relations and differences between linguistic items fall into two quite distinct kinds, each giving rise to a separate order of values. The opposition between these two orders brings out the specific character of each. They correspond to two different forms of mental activity, both indispensable to the workings of a language.

Words as used in discourse, strung together one after another, enter into relations based on the linear character of languages (cf. p. [103]). Linearity precludes the possibility of uttering two words simultaneously. They must be arranged consecutively in spoken sequence. Combinations based on sequentiality may be called syntagmas.1 The syntagma invariably comprises two or more consecutive units: for example, re-lire (‘re-read’), contre tous (‘against all’), la vie humaine (‘the life of man’), Dieu est bon (‘God is good’), s’il fait beau temps, nous sortirons (‘if it’s fine, we’ll go out’). In its place in a syntagma, any unit acquires its value simply in opposition to what precedes, or to what follows, or to both.

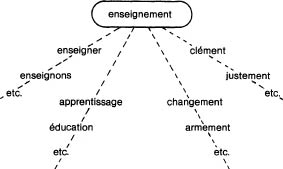

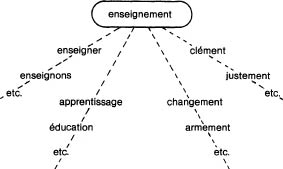

Outside the context of discourse, words having something in common are associated together in the memory. In this way they form groups, the members of which may be related in various ways. For instance, the word enseignement (‘teaching’) will automatically evoke a host of other words: enseigner (‘to teach’), renseigner (‘to inform’), etc., or armement, (‘armament’), changement (‘change’), etc., or éducation (‘education’), apprentissage (‘apprenticeship’). All these words have something or other linking them.

This kind of connexion between words is of quite a different order. It is not based on linear sequence. It is a connexion in the brain. Such connexions are part of that accumulated store which is the form the language takes in an individual’s brain. We shall call these associative relations.

Syntagmatic relations hold in praesentia. They hold between two or more terms co-present in a sequence. Associative relations, on the contrary, hold in absentia. They hold between terms constituting a mnemonic group.

Considered from these two points of view, a linguistic unit may be compared to a single part of a building, e.g. a column. A column is related in a certain way to the architrave it supports. This disposition, involving two units co-present in space, is comparable to a syntagmatic relation. On the other hand, if the column is Doric, it will evoke mental comparison with the other architectural orders (Ionic, Corinthian, etc.), which are not in this instance spatially co-present. This relation is associative.

Each of these two orders of relationship calls for certain special comments.

[172]

The examples given above (p. [170]) already make it clear that the notion of a syntagma applies not only to words, but to groups of words, and to complex units of every size and kind (compound words, derivative forms, phrases, sentences).

It is not sufficient to consider merely the relation between the parts of a syntagma, e.g. between contre (‘against’) and tous (‘all’) in contre tous (‘against all’), or between contre (‘over’) and maître (‘master’) in contremaître (‘overseer’). Account must also be taken of the relation between the whole and the parts, e.g. between contre tous and contre, contre tous and tous, contremaître and contre, contremaître and maître.

An objection might be raised at this point. The most typical kind of syntagma is the sentence. But the sentence belongs to speech, not to the language (cf. p. [30]). So does it not follow that the syntagma is a phenomenon of speech too? Not in our view. The characteristic of speech is freedom of combination: so the first question to ask is whether all syntagmas are equally free.

There are, in the first place, a large number of expressions belonging to the language: these are ready-made phrases, absolutely invariable in usage, in which it may even require reflection to distinguish the constituent parts: e.g. à quoi bon? (‘what’s the use?’), allons donc! (‘come along!’). The same is true, although not to the same extent, for expressions like prendre la mouche (‘to take offence’), forcer la main à quelqu’un (‘to force someone’s hand’), rompre une lance (‘to break a lance’), avoir mal à la tête (‘to have a headache’), à force de (‘by dint of’), que vous en semble? (‘what do you think of it?’) pas n’est besoin de . . . (‘no need to . . .’), etc. These are idiomatic expressions involving oddities of meaning or syntax. These oddities are not improvised, but handed down by tradition. In this connexion one might also cite morphological oddities which, although perfectly analysable, represent irregularities maintained solely by prevalence of usage: e.g. difficulté (‘difficulty’) as compared with facilité (‘ease’) and facile (‘easy’); mour-rai (‘I will die’), mourir (‘to die’), as compared with dormirai (‘I will sleep’), dormir (‘to sleep’), and finirai (‘I will finish’), finir (‘to finish’).1

[173]

But that is not all. To the language, and not to speech, must be attributed all types of syntagmas constructed on regular patterns. Since there is nothing abstract in linguistic structure, such types will not exist unless sufficiently numerous examples do indeed occur. When a new word such as indécorable (‘undecoratable’) crops up in speech (cf. p. [228] ff.), it presupposes an already existing type, and the type in question would not exist were it not for our recollection of a sufficient number of similar words already in the language, e.g. impardonnable (‘unpardonable’), intolérable (‘intolerable’), infatigable (‘indefatigable’), etc. Exactly the same holds for sentences and groups of words based upon regular models. Combinations like la terre tourne (‘the earth rotates’), que vous dit-il? (‘what does he say to you?’), etc. correspond to general combinatory types, which in turn are based in the language on specific examples heard and remembered.

Where syntagmas are concerned, however, one must recognise the fact that there is no clear boundary separating the language, as confirmed by communal usage, from speech, marked by freedom of the individual. In many cases it is difficult to assign a combination of units to one or the other. Many combinations are the product of both, in proportions which cannot be accurately measured.

Groups formed by mental association do not include only items sharing something in common. For the mind also grasps the nature of the relations involved in each case, and thus creates as many associative series as there are different relations. In enseignement (‘teaching’), enseigner (‘to teach’), enseignons (‘(we) teach’), etc., there is a common element in all the terms, i.e. the stem enseign- (‘teach-’). But the word enseignement also belongs to another series based upon a different common element, the suffix -ment: e.g. enseignement (‘teaching’), arme-ment, (‘armament’), changement (‘change’), etc. The association may also be based just on similarity of significations, as in enseignement (‘teaching’), instruction (‘instruction’), apprentissage (‘apprenticeship’), éducation (‘education’), etc. Similarly, it may be based just on similarity of sound patterns, e.g. the final syllables of enseignement (‘teaching’) and justement (‘precisely’).1 So sometimes there is a double associative link based on form and meaning, but in other cases just one associative link based on form or meaning alone. Any word can evoke in the mind whatever is capable of being associated with it in some way or other.

[174]

While a syntagma brings in straight away the idea of a fixed sequence, with a specific number of elements, an associative group has no particular number of items in it; nor do they occur in any particular order. In a series like désir-eux (‘desirous’), chaleur-eux (‘warm’), peur-eux (‘fearful’), etc. it is impossible to say in advance how many words the memory will suggest, or in what order. Any given term acts as the centre of a constellation, from which connected terms radiate ad infinitum.

Of these two characteristics found in associative series – indeterminate order and indefinite number – only the former is constant. The latter may not be found in certain cases. This is so with a very common type of associative group, flexional paradigms. In a Latin series like dominus, dominī, dominō, etc. we have an associative group based on a common element: the noun stem domin-. But the series is not open-ended, like enseignement, changement, etc., since the number of case forms is limited. Their sequence, however, is not fixed. It is purely arbitrary that grammarians list them in one order rather than another. As far as language-users are concerned, the nominative is not in any sense the ‘first’ case in the declension: the forms may be thought of in any variety of orders, depending on circumstances.

Notes

1 Needless to say, the study of syntagmas is not to be equated with syntax. The latter is only part of the former, as will be seen (cf. p. [185] ff.). (Editorial note)

1 The ‘regular’ forms ought presumably to be *difficilité and *mourirai. (Translator’s note)

1 This case is rare and may be treated as abnormal. For the mind naturally discards all associations likely to impede understanding and discourse. Nonetheless, the existence of such associative groups is proved by the category of feeble puns based upon the ridiculous confusions which may result from homonymy pure and simple. E.g. Les musiciens produisent les sons et les grainetiers les vendent (‘Musicians produce [sounds/ bran], which seedsmen sell’ – son meaning both ‘sound’ and also ‘bran’). Such cases must be distinguished from those in which word assoication, although fortuitous, is backed by a certain connexion of ideas: e.g. French ergot (‘spur, spike’) and ergoter (‘to quibble’), or German blau (‘blue’) and durchbläuen (‘to beat, thrash’). What is involved here is a new interpretation of one or other of the terms. These are cases of popular etymology (cf. p. [238]). Although of interest in the study of semantic change, from a synchronic viewpoint they merely fall into the category of enseigner, enseignement, etc. mentioned above. (Editorial note)