[221]

Chapter 4

Analogy

§1 Definition and examples

Sound change, it is clear from the preceding chapter, is a source of linguistic disturbance. Wherever it does not give rise to alternations, it contributes towards loosening the grammatical connexions which link words together. It increases the sum total of linguistic forms to no purpose. The linguistic mechanism becomes obscure and complicated inasmuch as irregularities produced by sound change take precedence over forms grouped under general types; in other words, inasmuch as what is absolutely arbitrary takes precedence over what is only relatively arbitrary (cf. p. [183]).

Fortunately, the effect of these changes is counterbalanced by analogy. Analogy is responsible for all the normal modifications of the external aspect of words which are not due to sound change.

Analogy presupposes a model, and regular imitation of a model. An analogical form is a form made in the image of one or more other forms according to a fixed rule.

[222]

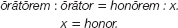

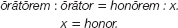

The Latin nominative singular honor (‘honour’) is analogical. Originally it was honōs, with an accusative honōsem. Then, following the rhotacisation of s (cf. p. [201]), it was honōs, with an accusative honōrem. Thus the stem then took two different forms. This duality was reduced by creating a new nominative honor, on the model of ōrātor: ōrātōrem. The process will be examined in detail below. In essence, it involves a computation of the missing fourth term in the proportion:

ōrātōrem : ōrātor = honōrem : x.

Here the solution is: x = honor.

It can thus be seen that, in order to counterbalance the diversifying effect of sound change (honōs : honōrem), analogy has once more brought the forms together and re-established regularity (honor: honōrem).

In French, the forms of the verb prouver (‘to prove’) for a long period included preuve (‘(he) proves’), prouvons (‘(we) prove’), and preuvent (‘(they) prove’). Today preuve and preuvent have been replaced by prouve and prouvent, forms which cannot be explained by sound change. Whereas aime (‘(he) loves’) can be traced back phonetically to Latin amat, aimons (‘(we) love’) is an analogical replacement of Old French amons. Similarly aimable (‘kind’) is an analogical replacement of amable. In Greek, intervocalic s fell, with the result that -eso- became -eo- (e.g. géneos for *genesos). However, this intervocalic s is found in the future and aorist forms of all verbs with vowel stems, e.g.  (‘I shall loose’), élūsa (‘I loosed’). Here the analogy of other forms like túpsō and étupsa, where the s did not fall, preserved the s in the future and aorist. In German, while Gast (‘guest’) : Gäste (‘guests’), Balg (‘skin’): Bälge (‘skins’) are phonetically regular plurals, Kranz (‘wreath’): Kränze (‘wreaths’) is analogical, replacing kranz : kranza. So too is Hals (‘neck’) : Hälse (‘necks’), where the plural was formerly halsa.

(‘I shall loose’), élūsa (‘I loosed’). Here the analogy of other forms like túpsō and étupsa, where the s did not fall, preserved the s in the future and aorist. In German, while Gast (‘guest’) : Gäste (‘guests’), Balg (‘skin’): Bälge (‘skins’) are phonetically regular plurals, Kranz (‘wreath’): Kränze (‘wreaths’) is analogical, replacing kranz : kranza. So too is Hals (‘neck’) : Hälse (‘necks’), where the plural was formerly halsa.

Analogy works in favour of regularity and tends to unify formational and flexional processes. But it is sometimes capricious. In German, beside Kranz : Kränze etc. one finds also Tag (‘day’) : Tage (‘days’), Salz (‘salt’) : Salze (‘salts’), etc. which for one reason or another have resisted analogy. So it is impossible to say in advance how far imitation of a model will extend, or which patterns are destined to provoke it. It is not always the more numerous forms which set analogy working. In Greek, the perfect of pheúgō (‘flee’) has active forms pé-pheuga, pépheugas, pepheúgamen, etc., but all the middle voice flexions lack the a: péphugmai, pephúgmetha, etc. The language of Homer shows that this a was originally missing from the plural and the dual of the active voice (cf. Homeric Greek ídmen, éïkton, etc.). The analogy began just with the active first person singular and was extended to almost the whole of the perfect indicative paradigm. The case is also remarkable because here analogy attaches to the stem an element (-a-) which is flexional in origin (hence pepheúga-men); whereas the opposite development – a stem element becoming attached to a suffix – is, as will be seen (cf. p. [233]), much more frequent.

[223]

Often two or three isolated words are enough to create a general form – an ending, for instance. In Old High German, weak verbs of the type habēn, lobōn, etc. have an -m in the first person singular of the present: habēm, lobōm. This -m originates with a few verbs, bim, stām, gēm, tuom, which are like the Greek verbs in -mi. These few alone imposed their -m on the whole class of weak verbs. In this case it should be noted that analogy did not regularise any phonetic diversity, but generalised a morphological formation.

§2 Analogies are not changes

[224]

The early linguists failed to understand the nature of analogical phenomena, which they described as ‘false analogy’. They thought that by inventing the nominative form honor to replace honōs (cf. p. [221]), Latin had made a ‘mistake’. In their view, anything which departed from an established order was an irregularity, a violation of an ideal form. Their illusion, very characteristic of the period, was that the original state of the language represented something superior, a state of perfection. They did not even inquire whether that earlier state had not been preceded by a still earlier one. Any liberty taken with it was an anomaly. The Neogrammarians were the first scholars to assign analogy to its rightful place, by showing that it is, along with sound change, the main factor in the evolution of languages, and the process by which they pass from one state of organisation to another.

But what is the nature of analogical phenomena? Are they, as is commonly believed, changes?

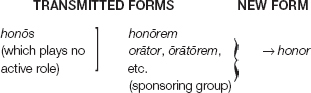

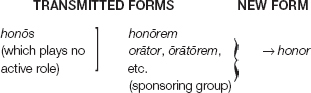

Every analogy is a drama involving three characters. They are: (i) the legitimate heir to the succession (e.g. Latin honōs), (ii) the rival (honor), (iii) a collective character, made up of the forms which sponsored this rival (honōrem, ōrātor, o-rātōrem, etc.). Honor is often regarded as a modification or ‘metaplasm’ of honōs, from which it derives most of its substance. But the one form which plays no part at all in the genesis of honor is honōs itself!

The phenomenon can be represented as follows:

It is clear that this is a case of ‘paraplasm’, of the installation of a rival alongside the traditional form – in short, of creation. Whereas sound change introduces nothing new without eliminating what formerly existed (as with honōrem replacing honōsem, cf. p. [221]), an analogical form does not necessarily eliminate its rival. Honor and honōs coexisted for a time and were interchangeable. However, since a language dislikes maintaining two signals for a single idea, it usually turns out that the primitive, less regular form falls into disuse and disappears. It is this outcome which makes it look as if a change of form has taken place: once the analogical process is completed, the old state of affairs (honōs : honōrem) and the new (honor : honōrem) appear to be opposed in the same way as would have resulted from sound change. But at the stage when honor first appears nothing is changed, because honor does not replace anything. Nor is the disappearance of honōs, a change either, since it is quite independent of the appearance of honor. Wherever we can follow the course of linguistic events in detail, we find that analogical innovation and elimination of the old form are two separate events. Nowhere does one discover a change in process.

[225]

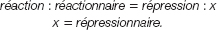

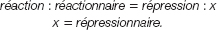

Analogy has nothing to do with replacing one form by another: often, indeed, it produces forms which replace nothing. In German, one can form a diminutive from any noun with a concrete meaning by adding the diminutive suffix -chen. But if a form Elefantchen (‘little elephant’) gained acceptance in the language, it would supplant nothing already in existence. Similarly in French on the model of pension : pensionnaire (‘pension : pensioner’), réaction : réactionnaire (‘reaction : reactionary’), etc. someone could invent interventionnaire meaning ‘in favour of intervention’, or répressionnaire meaning ‘in favour of repression’. The process is clearly the same as that involved in the genesis of honor. Both fit the same formula:

In neither case is there the least pretext for speaking of a ‘change’. The word répressionnaire replaces nothing. Another example of this kind would be the following. For the plural of the French adjective final (‘final’), one hears the analogical form finaux, which is said to be more regular than finals. Now suppose someone invented the adjective firmamental (‘of the firmament’) and gave it a plural firmamentaux. Would one say that finaux is an example of change, but firmamentaux an example of creation? Both cases involve creation. On the model of mur : emmurer (‘wall: immure’), there were formed tour : entourer (‘circuit : surround’) and jour : ajourer (‘daylight : perforate (as in fretwork)’). These derivatives, being relatively recent, strike us as creations. But if I discover that French of an earlier period also had the verbs entorner and ajorner, based on the same nouns torn and jorn (= modern French tour and jour), should I now change my mind and declare that entourer and ajourer are modifications of the earlier forms? The illusion of analogical ‘change’ comes from a relation established with the term which has been ousted by the new one. But this is a mistake, because these so-called ‘changes’ (like honor) are the same as what we call ‘creations’ (like répressionnaire).

[226]

§3 Analogy as the creative principle in languages

If, having demonstrated what analogy is not, we now study it from a positive point of view, it becomes immediately apparent that its principle is simply identical with that of linguistic creation in general. What is this principle?

Analogy is a psychological phenomenon. But that alone does not suffice to distinguish it from sound change, which may also be considered as such (cf. p. (208]). One must take a step further, and say that analogy is a grammatical phenomenon. It presupposes awareness and grasp of relations between forms. Where sound is concerned, ideas count for nothing; whereas they necessarily intervene in the case of analogy.

In the change of intervocalic s to r in Latin (cf. p. [201]), as in honōsem → honōrem, no part is played by comparison with other forms, nor by the meaning of the word. It is the corpse of the form honōsem which survives as honōrem. On the contrary, to account for the appearance of honor beside honōs we have to appeal to other forms, as indicated in the formula of the four-term proportion:

This combination would have no rationale if the mind did not associate the forms involved on the basis of their meanings.

So in analogy, everything is grammatical. But to this it must immediately be added that the creation which results can only belong at first to speech. It is the work of a single speaker. This is the sphere, on the fringe of the language, where the phenomenon must first be located. None the less, two things must be distinguished: (1) grasping the relation which connects the sponsoring forms, and (2) the result suggested by this comparison, i.e. the form improvised by the speaker to express his thought. The latter alone belongs to speech.

[227]

Analogy teaches us once again, then, to distinguish between the language itself and speech (cf. p. [36] ff.). It shows us how speech depends on the language, and allows us to put our finger on the operational linguistic mechanism, as earlier described (cf. p. [179]). Any creation has to be preceded by an unconscious comparison of materials deposited in the store held by the language, where the sponsoring forms are arranged by syntagmatic and associative relations.

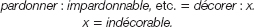

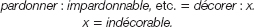

So one whole part of the phenomenon has already been completed before the new form becomes visible. The continual activity of language in analysing the units already provided contains in itself not only all possibilities of speaking in conformity with usage, but also all possibilities of analogical formation. Thus it is a mistake to suppose that the generative process occurs only at the moment when the new creation emerges: its elements are already given. Any word I improvise, like in-décor-able (‘un-decoratable’) already exists potentially in the language. Its elements are all to be found already in syntagmas like décor-er (‘to decorate’), décor-ation (‘decor-ation’), pardonn-able (‘pardon-able’), mani-able (‘manage-able’), in-connu (‘un-known’), in-sensé (‘in-sane’), etc. Its actualisation in speech is an insignificant fact in comparison with the possibility of forming it.

To summarise, analogy in itself is simply one aspect of the phenomenon of interpretation, a manifestation of the general activity which analyses units in order then to make use of them. That is why we say that analogy is entirely grammatical and synchronic.

[228]

This characteristic of analogy prompts two observations which support our views on absolute and relative arbitrariness (cf. p. [180] ff.).

1. One could classify words according to their relative capacity for giving rise to others, depending on the extent to which they are themselves analysable. A simple word is, by definition, unproductive: e.g. magasin (‘shop’), arbre (‘tree’), racine (‘root’). The word magasinier (‘store-keeper’) was not engendered by magasin: it was formed on the model of prisonnier : prison (‘prisoner : prison’), etc. Similarly emmagasiner (‘to store’) owes its existence to the analogy of emmailloter : maillot (‘to swaddle : swaddling clothes’), encadrer : cadre (‘to frame : frame’), encapuchonner : capuchon (‘to hood : hood’), etc.

So in every language there are productive words and sterile words. But the proportions vary. What this comes down to is the distinction previously drawn (cf. p. [183]) between ‘lexicological’ and ‘grammatical’ languages. In Chinese, the majority of words are unsegmentable; whereas in artificial languages they are nearly all segmentable. An Esperantist is fully at liberty to construct new words on any given root.

2. We have already noted (p. [222]) that any analogical creation can be represented as an operation like the computation of the fourth term of a proportion. Very often this formula is used to explain the phenomenon itself, whereas we have sought its rationale in the analysis and reconstruction of elements supplied by the language.

There is a conflict between these two conceptions. If the proportion is a sufficient explanation, what purpose is served by the hypothesis which appeals to analysis of the elements? To form indécorable, there is no need to extract its elements (in-décor-able): it suffices to take the whole and place it in the equation:

[229]

In that way there is no need to credit the speaker with a complicated operation too much like the conscious analysis of the grammarian. In a case like Krantz : Kräntze (cf. p. [222]), based on Gast : Gäste, decomposition seems less plausible than the proportion, since in the model the stem is Gast- in one case and Gäst- in the other; it looks as though a phonetic feature of Gäste has simply been replicated on Kranze.

Which of these theories corresponds to the reality? Let us note first of all that the case of Kranz does not necessarily preclude analysis. We have seen alternation operative in roots and prefixes (cf. p. [216]), and a feeling for alternation may exist alongside a positive analysis.

These two conflicting conceptions are reflected in two different grammatical doctrines. Our European grammars operate with the proportion. They explain the formation of a preterite in German, for example, on the basis of complete words: the pupil is told to form the preterite of, say, lachen (‘to laugh’) on the model of setzen : setzte (‘to sit : sat’). A Hindu grammar, on the contrary, would devote one chapter to the study of the roots (setz-, lach-, etc.), and a different chapter to the endings of the preterite (-te, etc.). It would give the elements resulting from the analysis, and one would then have to recombine them to form whole words. In any Sanskrit dictionary, the verbs are arranged in an order determined by their root.

Depending on the predominant tendency in each linguistic group, the grammatical theorists will incline to the one or the other of these methods.

Early Latin seems to favour the analytic procedure. Here is a clear demonstration of the fact. The vowel length of a is not the same in făctus (‘made’) and āctus (‘done’), although it is in făciō (‘I make’) and ăgō (‘I do’). One must suppose that āctus goes back to *ăgtos and attribute the lengthened vowel to the voiced consonant which follows. This hypothesis is fully confirmed by the Romance languages. The opposition spĕcio : spĕctus (‘I see : seen’) vs. tĕgō : tēctus (‘I cover : covered’) is reflected in French dépit (‘spite’: Latin despĕctus) vs. toit (‘roof’ : Latin tēctum). Cf. also Latin  : confĕctus (‘I complete : completed’) vs. rĕgō : rēctus (‘I rule : ruled’) : whereas confĕctus gives French confit, d

: confĕctus (‘I complete : completed’) vs. rĕgō : rēctus (‘I rule : ruled’) : whereas confĕctus gives French confit, d rēctus gives French droit. But *agtos, *tegtos, *regtos were not inherited from Proto-Indo-European, where the corresponding forms were certainly *ăktos, *tĕktos, etc. It was prehistoric Latin which introduced *agtos, *tegtos, *regtos, in spite of the difficulty of pronouncing a voiced consonant immediately before a voiceless one. This could only have been done if there was a strong consciousness of the stem units ag-, teg-, etc. Early Latin thus possessed a high degree of awareness of the constituent parts of a word (stems, suffixes, etc.) and of their fitting together. It is probable that in our modern languages it is not felt so acutely. But German probably has it more than French (cf. p. [256]).

rēctus gives French droit. But *agtos, *tegtos, *regtos were not inherited from Proto-Indo-European, where the corresponding forms were certainly *ăktos, *tĕktos, etc. It was prehistoric Latin which introduced *agtos, *tegtos, *regtos, in spite of the difficulty of pronouncing a voiced consonant immediately before a voiceless one. This could only have been done if there was a strong consciousness of the stem units ag-, teg-, etc. Early Latin thus possessed a high degree of awareness of the constituent parts of a word (stems, suffixes, etc.) and of their fitting together. It is probable that in our modern languages it is not felt so acutely. But German probably has it more than French (cf. p. [256]).

[230]

(‘I shall loose’), élūsa (‘I loosed’). Here the analogy of other forms like túpsō and étupsa, where the s did not fall, preserved the s in the future and aorist. In German, while Gast (‘guest’) : Gäste (‘guests’), Balg (‘skin’): Bälge (‘skins’) are phonetically regular plurals, Kranz (‘wreath’): Kränze (‘wreaths’) is analogical, replacing kranz : kranza. So too is Hals (‘neck’) : Hälse (‘necks’), where the plural was formerly halsa.

(‘I shall loose’), élūsa (‘I loosed’). Here the analogy of other forms like túpsō and étupsa, where the s did not fall, preserved the s in the future and aorist. In German, while Gast (‘guest’) : Gäste (‘guests’), Balg (‘skin’): Bälge (‘skins’) are phonetically regular plurals, Kranz (‘wreath’): Kränze (‘wreaths’) is analogical, replacing kranz : kranza. So too is Hals (‘neck’) : Hälse (‘necks’), where the plural was formerly halsa.

:

:  rēctus

rēctus