Diachronic Units, Identities and Realities

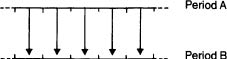

Static linguistics operates with units which are synchronically linked together. Everything said in the previous chapters shows that in a diachronic sequence we are not dealing with elements delimited once and for all, as might be represented in the following diagram:

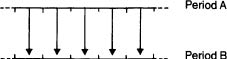

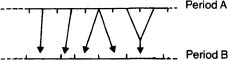

On the contrary, their correlation is constantly changing, because of events taking place in the language. So they might be more appropriately represented as follows:

This is the outcome of all the factors discussed above – sound change, analogy, agglutination, etc.

Almost all the examples so far cited relate to word formation. The following example is syntactic. Proto-Indo-European had no prepositions. It marked relations by its numerous case flexions, which had very specific meanings. Nor did Proto-Indo-European have verbs with prefixes. It had only particles, i.e. little words added to a verb phrase to add some specification or nuance of meaning to the verb. So Proto-Indo-European had nothing corresponding either to Latin īre ob mortem (‘to go to meet one’s death’), or to obīre mortem: instead it would have used the equivalent of īre mortem ob. This is still the stage we find in early Greek. In (i) óreos baínō káta (‘l come down from the mountain’), óreos baínō alone means ‘I come from the mountain’ (the genitive óreos having the value of an ablative), while káta adds the qualification ‘descending’. At a later stage, Greek has (ii) katà óreos baínō, with katà functioning as a preposition, or (iii) kata-baínō óreos, with agglutination of the participle as a prefix.

Here there are two or three distinct phenomena, but all are based upon an interpretation of units. (1) There is the creation of a new class of words – prepositions – by a simple redistribution of units given. One particular order, without significance originally, perhaps due to some fortuitous circumstance, gave rise to a new grouping: kata, originally independent, attaches itself to the noun óreos, and this pair acts as the complement of the verb baínō. (2) There is the appearance of a new type of verb, katabaínō. This is a different psychological grouping, also favoured by a special distribution of units and consolidated by agglutination. (3) As a natural consequence, there is a weakening of the sense of the genitive ending (óre-os). It is katà which now takes over the role of expressing the principal idea which formerly the genitive alone expressed. The importance of the ending -os is thereby diminished. This development paves the way for its future disappearance.

In all three cases, then, there is indeed a new distribution of units. The same substance is retained, but with different functions. It should be noted that no sound change has intervened to induce any of these shifts. Moreover, although the material has not altered, it is not to be supposed that the change is restricted to the domain of meaning. There is no syntactic phenomenon which does not involve the correlation of a certain sequence of concepts and a certain sequence of phonetic units (cf. p. [191]): it is precisely this correlation which has altered. The sounds remain, but the significant units are no longer the same.

As stated previously (p. [109]), an alteration in the linguistic sign is a shift in the relation between signal and signification. This definition applies not only to changes in individual items, but to the evolution of the whole system. Diachronic development in its entirety is just that.

However, when one has noted a certain shift in synchronic units, one is still a long way from accounting for what has taken place in the language. There is the problem of the diachronic unit itself: it arises when we ask, of each event, which is the element directly subject to change. We have already encountered a problem of this kind in connexion with sound change (cf. p. [133]). Sound change affects only individual sounds: words as such are not units affected by it. Since there are many kinds of diachronic change, there will be many analogous questions to be answered. The units identified for these purposes will not necessarily correspond to the units recognised in the synchronic domain. In conformity with the principle laid down in Part One, the notion of a unit cannot be the same for both synchronic and diachronic studies. In any case, it will not be fully elucidated as long as it has not been studied from both static and evolutionary points of view. Only the solution of the problem of the diachronic unit will enable us to penetrate beyond the superficial appearance of linguistic evolution and grasp its essence. Here, as in synchrony, understanding what the units are is indispensable in order to distinguish illusion from reality (cf. p. [153]).

[249]

But another question, and a particularly delicate one, is that of diachronic identity. For in order to be able to say that a given unit has remained the same over time, or that, while remaining a distinct unit, it has changed in form or meaning – any of which is possible – I must know on what I base the claim that an element taken from one period – e.g. the French word chaud (‘hot’) – is the same as an element taken from another period – e.g. the Latin calidum.

To this question it will doubtless be replied that calidum became chaud through the regular operation of phonetic laws, and that therefore the equation calidum = chaud is correct. This is what is called a ‘phonetic identity’. Another would be Latin se-para-re and French sevrer. French fleurir, on the other hand, would not thus be equated with Latin flo-re-re, since the latter by regular phonetic change should have produced *flouroir.

This type of correspondence seems at first sight to cover the notion of diachronic identity in general. But in fact historical phonetics alone does not suffice to account for it. It is doubtless correct to say that Latin mare (‘sea’) ought to appear in French in the form mer on the grounds that Latin a became e in French under certain conditions, that final unstressed e fell, etc. But to state that these connexions a → e, e → zero, etc. constitute the identity in question is to put the cart before the horse. On the contrary, one judges that a became e, that final e fell, etc. in the light of the correspondence mare : mer.

[250]

If two people from different regions of France say se fâcher (‘become angry’) and se fôcher respectively, the difference is very minor in comparison with the grammatical facts which allow us to recognize in these two different forms one and the same linguistic unit. The diachronic identity of two words as different as calidum and chaud simply means that the transition from one to the other was via a series of synchronic identities in speech, without the link between them ever being broken by successive sound changes. That is why we could say (p. [150]) that it is just as interesting to know how Messieurs! (‘Gentlemen!’) repeated several times in succession in the same speech is one and the same as it is to know how the negation pas (‘not’) is the same as the noun pas (‘pace’), or why chaud is the same as calidum, which comes to the same thing. The second problem is no more than an extension and complication of the first.